1. Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic autoimmune disorder triggered by the consumption of gluten, a protein found in cereals such as wheat, barley, and rye, in individuals who are genetically predisposed. This condition leads to inflammation and damage to the villi of the small intestine, resulting in malabsorption of nutrients and subsequent nutritional deficiencies.1 Currently, a gluten-free (GF) diet is the only treatment that has been shown to produce positive results in these patients. In recent decades, the incidence of celiac disease has increased, and together with the strict dietary requirement, this has driven a growing demand for GF products on the market.2,3 Despite the therapeutic efficacy of a GF diet, commercial GF products often contain low levels of dietary fiber, minerals such as zinc, magnesium, and iron, and vitamins (particularly B vitamins), while being high in calories, fats, and sugars.4 These nutritional imbalances in commercial GF products can increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies and metabolic disorders in individuals who rely on them.5

Several innovative approaches have recently emerged to enhance the nutritional value of GF products. One of the most relevant developments is the use of pseudocereals such as quinoa, amaranth, and buckwheat, as well as legume flours, which are rich in high-quality protein, dietary fiber, minerals, and bioactive compounds.6,7 Similarly, there has been growing interest in the inclusion of flax seeds due to their high omega-3 fatty acid, lignan, and soluble fiber content, which contribute to cardiovascular health and glycemic control.8,9 Additionally, extracts from plants, such as grapes, bananas, apples, and carrots, which are rich in phenolic compounds and antioxidants, are being investigated as functional ingredients to enhance the nutritional value and confer additional bioactive properties to GF products.10-12

Food loss and waste represent a global challenge, with nearly one-third of food produced for human consumption discarded annually, resulting in inefficient resource use and considerable environmental impacts.13 Within the framework of a circular economy, the valorization of vegetable by-products emerges as a sustainable strategy to mitigate these impacts while enabling the development of innovative products with enhanced nutritional value.14

In this context, broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) and artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.), edible inflorescence vegetables, are of great interest due to their high global production and numerous nutritional benefits. Broccoli production, whose combined output with cauliflower exceeded 26 million tons in 2023,15 generates a considerable quantity of by-products, since the edible fraction accounts for only about 15% of the total weight, while the remaining parts—mainly stems and leaves—are commonly discarded post-harvest.16 However, these non-edible fractions represent a valuable source of bioactive compounds, including glucosinolates and isothiocyanates, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, vitamin C, dietary fiber, and minerals.17 These components have been widely associated with a range of health-promoting biological activities, such as anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antihypertensive effects.18 Similarly, artichoke production reaches approximately 1.6 million tons annually,15 of which only the immature inflorescences are consumed, while the remaining 60-85%, primarily composed of outer bracts, leaves, and stems, is discarded as by-products.19 In general, these by-product fractions are rich in nutrients and bioactive compounds of considerable interest, including phenolic acids derived from caffeoylquinic acid, flavonoids such as luteolin and apigenin, minerals, vitamins, and especially a high content of dietary fiber, particularly inulin and pectin.20,21 Such compounds have been linked to antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, and prebiotic activities.22

Although vegetables are rich in fiber, the insoluble fraction predominates, which is less fermentable and generates fewer health-promoting metabolites than the soluble fraction (SDF).23 Different techniques and methods, such as mechanical degradation, chemical treatments, thermal processes, and enzymatic methods, have been investigated to enhance the soluble fibers in foods.24 Among these, enzymatic methods using cellulases, pectinases, and xylanases are particularly effective, operating under mild and environmentally friendly conditions.25,26

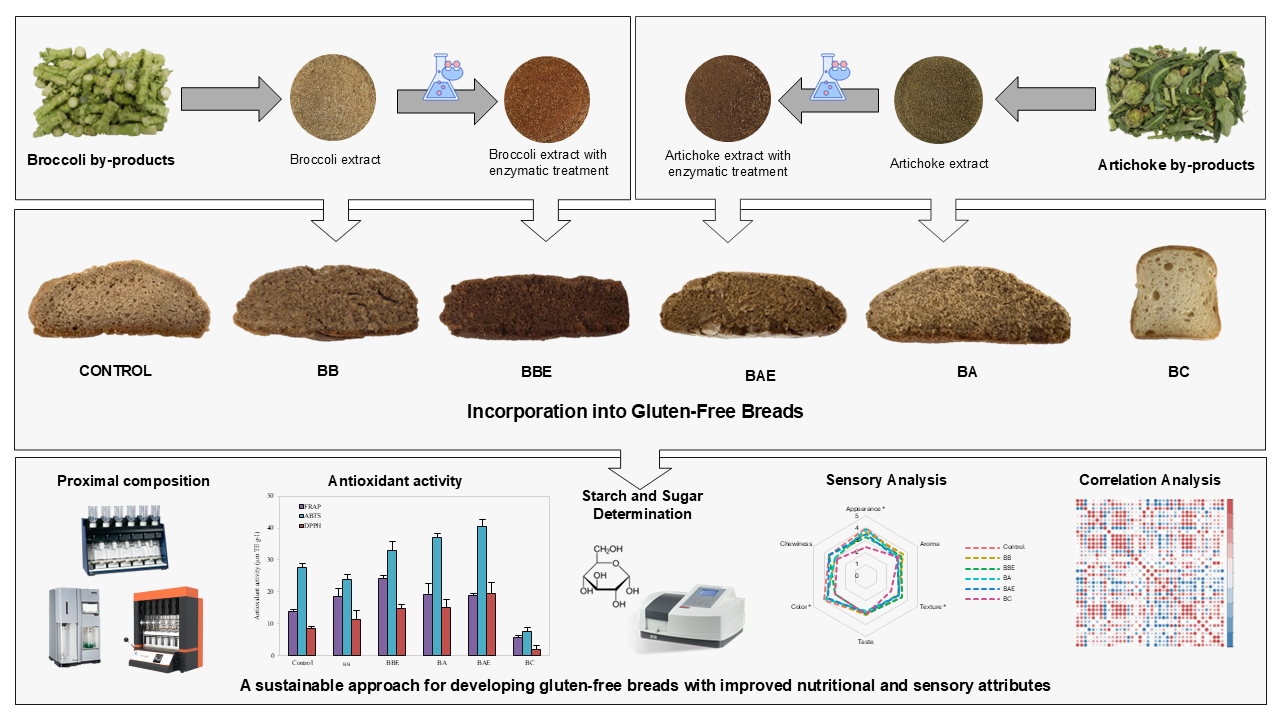

Considering the limited literature on exploring the use of enzyme-treated artichoke and broccoli by-products as natural functional ingredients in gluten-free breads, this study investigated their effect, on the physico-chemical, nutritional, and sensory properties of gluten-free formulations. The enriched breads were compared with a control formulation and with a commercial gluten-free bread to assess improvements in fiber content, antioxidant potential, and overall quality.

In this study, GF bread formulations were developed with the inclusion of broccoli and artichoke by-products after enzymatic treatment, which were compared with the Control and commercial GF bread. The effects of these vegetable by-products and enzymatic treatment on the nutritional quality and sensory attributes of the breads obtained were evaluated. This approach aims not only to enhance the functional properties of GF products for celiacs but also to contribute to the sustainable management of agro-industrial waste.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Broccoli and Artichoke Extracts Preparation

Agro-industrial by-products from broccoli (stems and leaves) and artichoke (stems, leaves, and external bracts) were supplied by Cricket (Lorca, Spain). All by-product powders were obtained following the method described by Ayuso et al.27 The different broccoli and artichoke bio-residues were dried in a forced-air oven at 50 °C for 24 hours. Once completely dried, the by-products were ground and sieved to produce fine powders with a particle size of 500 µm.

Viscozyme® L, a multi-enzyme complex (cellulase, arabanase, β-glucanase, xylanase, and xylanase) with strong pectolytic activity from Aspergillus aculeatus, and Celluclast® 1.5L, a cellulase obtained from Trichoderma reesei, were utilized for the enzymatic treatment of broccoli and artichoke by-products, respectively. Both enzymes were purchased from Novozymes (Bagsværd, Denmark).

For the enzymatic treatment, diluted broccoli and artichoke powders (1:5, w/v) were incubated with Viscozyme® L (pH 4.5, 45 °C) and Celluclast® 1.5L (pH 6, 50 °C), respectively, at 0.45% (v/w) for 24 h under continuous magnetic stirring. The hydrolyzed mixtures were dried at 60 °C in a forced-air oven and subsequently milled again to achieve the same particle size as before enzymatic treatment.

2.2. Gluten-Free Breads Formulation

The ingredients used in the GF bread formulation, as detailed in

Table 1, were obtained from a local supermarket in Murcia, Spain. Ground flax seeds, sugar, and dry yeast were mixed with water and allowed to stand for 1 hour at 25ºC to activate the yeast and form the flaxseed gel, thereby supporting proper fermentation and improving dough cohesion. The remaining bread ingredients were then added and mixed to obtain a fluid and homogeneous dough using an automatic bread machine (Silvercrest®, IAN 285058, Lidl Stiftung & Co. KG, Neckarsulm, Germany) set to the “gluten-free” program. This program comprises multiple stages of kneading, resting, and baking, with a total duration of 2 hours.

Five different GF formulations were developed: a control bread without any vegetable extract (Control); breads enriched with 12.5 g of dried broccoli extract, either untreated (BB) or enzymatically treated (BBE); and breads containing 8.8 g of dried artichoke extract, either untreated (BA) or enzymatically treated (BAE). After baking, the loaves were allowed to cool for 1 hour, then sliced and vacuum-packed in polyethylene bags and stored at −20 °C until further analysis. The amounts of extract and broccoli were estimated based on the fiber content of all ingredients to ensure that the breads could be declared as “high fiber” products in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006.28

For comparison, the five GF formulations were evaluated alongside a commercial GF bread (BC) purchased from a local supermarket. According to the product label, its composition includes: water, maize starch, rice flour, sugar, eggs (11%), vegetable margarine (palm fat, coconut fat, water, rapeseed oil, salt; emulsifier: mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids; natural flavor), glucose syrup, milk powder, vegetable fiber (psyllium), thickeners (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, guar gum), yeast, emulsifier (mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids), salt, acidifying agent (tartaric acid), and natural vanilla flavor. The visual appearance of the GF breads is presented in

Figure 1.

2.3. Proximal Composition

The proximal composition of formulated and commercial GF breads was analyzed according to the official protocols set forth by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) employing the following methods: moisture (964.22), ash (923.03), protein (955.04), total fat (920.39), and dietary fiber fractions (insoluble, soluble, and total) (985.29).29 The carbohydrate content was calculated by difference, based on the values obtained for moisture, protein, fat, and ash.30 The energy content was estimated using standard conversion factors, in accordance with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) recommendations.31

2.4. Starch Determination

Rapidly digestible starch (RDS), slowly digestible starch (SDS), total digestible starch (TDS), and resistant starch (RS) were determined using the enzymatic Digestible and Resistant Starch Assay Kit (Megazyme International, Bray, Ireland), following the procedure recommended by the manufacturer. This method, based on the methodology of Englyst et al., involves a kinetic enzymatic digestion coupled with colorimetric quantification of glucose released at 510 nm wavelength.32 Enzymatic digestion was conducted at 37 °C for 240 minutes using pancreatic alpha-amylase and amyloglucosidase (PAA/AMG). Aliquots were collected at 20 minutes to quantify RDS, at 120 minutes for SDS, and at 240 minutes to determine TDS and RS. Results were expressed as g of starch per 100g of bread.

2.5. Physicochemical Parameters

Color was assessed using a CR-400 portable colorimeter (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan), calibrated with a standard white reference plate. The measured parameters included lightness (L*), red-green component (a*), yellow-blue component (b*), chroma (C), and hue (h) following the CIEL*a*b* color space system. Measurements were conducted in triplicate on 16 mm-thick slices from each bread sample. The total color difference (ΔE*) of each formulation compared to the Control bread was calculated with the following formula:

The pH was determined potentiometrically using a sensION+ PH31 pH meter (Hach-Lange, Barcelona, Spain) in a 1:10 (w/v) homogenized suspension of bread in distilled water. Total titratable acidity (TTA) was then assessed in the same suspension by titration with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) until the pH reached 8.5. Results were expressed as mL NaOH/10 g.

L-lactic acid and acetic acid concentrations were quantified using specific commercial enzymatic assay kits (BioSystems S.A., Barcelona, Spain), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were performed on the BioSystems Y15 automatic analyzer (BioSystems S.A., Barcelona, Spain), measuring absorbance at 340 nm. Results were expressed as grams of L-lactic or acetic acid per kilogram of bread.

2.6. Determination of Disaccharides and Monosaccharides

Monosaccharides (glucose and fructose) and disaccharides (sucrose and maltose) concentrations were analyzed using enzymatic methods with three commercial kits (BioSystems S.A., Barcelona, Spain). Measurements were carried out spectrophotometrically at 340 nm using a BioSystems Y15 automatic analyzer (BioSystems S.A., Barcelona, Spain). Results were expressed as g of glucose, fructose, sucrose, or maltose per 100 grams of bread.

2.7. Antioxidant Capacity and Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Analysis

Before analysis, bioactive compounds were extracted from the breads by homogenizing 2 g of sample with a 1:5 methanol/water (80:20, v/v) solution. The mixtures were incubated for 24 h at 4 °C in the dark, then centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 25 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were filtered through 0.45 µm nylon filters and stored at -20 °C until analysis.

The antioxidant capacity of the samples was evaluated using three complementary spectrophotometric assays. The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay was carried out by combining 100 µL of the extracted sample with 1 mL of FRAP reagent, which contained acetate buffer, FeCl₃·6H₂O, and 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ).33 The absorbance was measured at 593 nm after 4 min in the dark. For the DPPH free radical scavenging 100 µL of the sample was mixed with 3.9 mL of a methanolic 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl solution and incubated in dark conditions for 30 min.34 The decrease in absorbance at 515 nm was recorded. The ABTS radical cation decolorization assay was conducted by incubating 100 µL of the sample with 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) for 4 min, followed by measuring absorbance at 734 nm.35 All antioxidant activity assays were performed in triplicate, and results expressed as µmol trolox equivalents (TE) per g of sample. In addition, the TPC of the bread samples was determined following the method described by Singleton et al., by measuring the absorbance at 750 nm after a 1-hour incubation of the extracted sample mixed with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent.36 The analysis was carried out in triplicate, and results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per g of sample. All spectrophotometric measurements were performed on an Evolution 300 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.8. Sensory Analysis

A hedonic sensory evaluation was conducted on the six GF bread samples using a structured 5-point scale to assess sensory attributes, including appearance, aroma, texture, taste, color, chewiness, overall acceptability, and purchase intention. The bread samples were cut into 3 cm3 portions and coded with randomly selected three-digit numbers. Twenty-five trained panelists (14 female, 11 male) aged between 18 and 60 years participated in this analysis. The evaluation was conducted in individual sensory booths according to ISO guidelines,37 with mineral water provided for rinsing their mouths between samples.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All determinations were conducted in three independent experimental replicates (n=3), and results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software, version 28.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences among GF breads were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), setting a significance threshold of p < 0.05, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. The datasets from all experimental analyses were integrated and visualized through a heatmap of Pearson correlation coefficients, constructed using the 'pheatmap' package (version 2.5.0) in R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition and Physicochemical Characteristics

The chemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and TPC of the different GF bread samples, including formulated breads and the commercial bread, are detailed in

Table 2.

Comparative analyses were performed using the Control as a reference to determine the effects of incorporating by-products into the formulation. On the other hand, the experimental GF breads were compared with a commercial product to establish nutritional differences relative to a market-available option. In terms of macronutrients, the broccoli samples (BB and BBE) showed no significant differences compared to the Control, maintaining similar profiles in energy, fat, protein, moisture, ash, and carbohydrates. The only exception was a slight increase in protein content in BBE, although it was not statistically significant. In contrast, samples with artichoke by-products showed a significant decrease in fat levels (about 8 g/100g) compared to the Control (12.33 g/100g). The observed decrease in fat content can be attributed to the fat-binding capacity of dietary fiber, which has been demonstrated to retain or immobilize lipids within the food matrix, thereby limiting their extractability during analysis.38,39 In addition, both BA and BAE showed a significant increase in the ash fraction, 5.46 and 4.82 g/100g, respectively, compared to 2.38 g/100g for the Control. The increase in ash content observed after adding artichoke extract can be attributed to the naturally high mineral content of this vegetable.40 Similar findings were reported by Dadali, who observed higher ash levels in cakes enriched with artichoke by-product powder.41

With respect to dietary fiber (DF) content, the untreated breads (BB and BA) showed differences compared to the Control. BB exhibited similar insoluble (IDF, 10.68 g/100 g) and total fiber (TDF, 11.22 g/100 g) levels as the Control, whereas BA showed markedly higher IDF and TDF (17.05 and 18.58 g/100 g, respectively). Breads subjected to enzymatic treatment (BBE and BAE) displayed a significant increase in the soluble fiber fraction (SDF), with BBE reaching 2.16 g/100 g and BAE reaching the highest value of 2.75 g/100 g. However, IDF and TDF in the treated breads were slightly lower than in their respective untreated counterparts due to the conversion of insoluble fiber into soluble fiber, while remaining elevated compared to the Control. Similar results were observed in a previous study, where artichoke extracts generally had higher levels of dietary fiber than broccoli extracts, and when different enzymatic treatments were applied, their SDF levels increased significantly while reducing IDF levels.27 In the case of artichoke, the commercial enzyme Celluclast® 1.5L was used, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in insoluble polysaccharides, resulting in the release of water-soluble polysaccharides and oligosaccharides.42 On the other hand, the findings in the study of the enzymatic treatment of broccoli by-products are attributed to the use of Viscozyme® (an enzyme complex composed of arabinase, cellulase, β-glucanase, hemicellulase, and xylanase). This treatment is justified by the predominant presence of cellulose, xylans, and pectins in the wall of broccoli stems, which, when fragmented, release soluble oligosaccharides and, consequently, increase the SDF.43

Additionally, the analyses revealed significant variations in antioxidant capacity (FRAP, ABTS, and DPPH) and total phenolic content (TPC) among the evaluated samples. All bread supplemented with vegetal extracts exhibited improvements compared to the Control. Treatment with both commercial enzymes caused significant changes (p <0.05). In the GF bread with broccoli, enzymatic treatment resulted in increases of 30.9%, 37.3%, 29.7%, and 28.9% for FRAP, ABTS, DPPH, and TPC, respectively. In contrast, enzymatic treatment in artichoke bread produced more moderate changes, with increases of 9.3%, 27.6%, and 17.3% in ABTS, DPPH, and TPC, respectively. The differences observed between breads enriched with broccoli and artichoke extracts and the Control can be attributed to the higher content of polyphenols and other bioactive compounds in these plant matrices.44,45 However, despite their abundance, the thermal processing involved in bread-making can partially degrade these compounds. As reported by Franke et al., the retention of bioactive compounds is highly dependent on processing conditions, which may explain why the enriched breads did not show markedly higher antioxidant activity or phenolic content compared to Control.46 However, thermal processing during baking may reduce some heat-sensitive compounds, attenuating the beneficial effect of these extracts. On the other hand, the increases observed in antioxidant capacity and TPC in BBE and BAE can be attributed to the enzymatic action on the plant matrix. This action degrades cell wall components, releasing bound polyphenols, which are then transformed into soluble and bioavailable forms. Additionally, enzymatic hydrolysis generates oligosaccharides with inherent antioxidant activity, further contributing to the overall effect.27,47,48

BC, predominantly composed of refined flours, starches, and processed vegetable fats, contains lower amounts of total dietary fiber (4.07 g/100 g), protein (2.90 g/100 g), and antioxidant capacity, together with a higher carbohydrate content (43.48 g/100 g) compared to the control formulation. In contrast, the Control bread, made with buckwheat flour, vegetable proteins, and seeds, incorporates highly valuable ingredients that provide it with a clearly superior nutritional and functional profile.49-51

3.2. Starch and Sugar Content

Table 3 shows the results for the different fractions of digestible starch: slow (SDS), rapid (RDS), and total (TDS); and resistant starch (RS). The profile of the samples in terms of monosaccharides and disaccharides is also detailed.

The different bread formulations showed significant variations in starch digestibility and simple sugar profile (p < 0.05). BC had a significantly higher RDS content than Control (51.96 and 44.20 g/100g, respectively) and a lower SDS concentration (4.83 and 7.17 g/100g). Additionally, it presented the lowest RS content among the samples (1.04 g/100g). This profile corresponds to that described by Giuberti and Gallo, who reported that commercially available GF products tend to contain highly available starches and a low resistant fraction due to refined flours and aerated structure, resulting in a higher glycemic index.52 In contrast, Control showed a more favorable profile, consistent with Di Cairano et al., who reported that less refined or underutilized flours, such as buckwheat flour used in this study, reduce rapid starch digestion and glycemic response.53

Conversely, formulations containing broccoli and artichoke extracts, particularly those treated enzymatically (BBE and BAE), showed a significant reduction in RDS (41.11 and 38.00 g/100g, respectively), and a marked increase in SDS (21.72 and 18.23 g/100g). The RS content remained similar among the different formulations, ranging from 1.16 to 1.58 g/100g, with BBE and BAE once again showing the highest values. These findings suggest that the incorporation of plant extracts, and especially their enzymatic treatment, significantly modifies the digestibility of starch in GF breads. A redistribution of the starch fractions towards a slower profile was observed, which could imply a lower glycemic index of the final product.52 The lower proportion of RDS and the increase in SDS in breads enriched with plant extracts are consistent with the findings of Santamaría et al. and Melini et al., who reported similar effects when incorporating different flours or plant extracts into GF breads.54,55 The observed effect was attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds and plant fibers, which interfere with starch and modify its gelatinization. Consequently, the broccoli and artichoke extracts used in this study, rich in indigestible polysaccharides and antioxidants, would have contributed to a bread matrix less accessible to digestive enzymes. Moreover, the more pronounced effects in the enzyme-treated samples can be explained by mechanisms similar to those reported by Kasprzak et al., where enzyme treatment of different starch sources modified their molecular structure, increasing the proportion of RS and reducing rapid digestibility.56 All this suggests that the combination of plant extracts and enzymatic treatment may be an effective strategy for improving the digestion profile of starch in GF breads.

The sugar profile showed variations consistent with starch behavior. BC presented the highest glucose and maltose content (0.80 and 1.31 g/100g, respectively), significantly higher than those of Control. This reflects faster hydrolysis and greater availability of simple sugars due to its composition of refined flours, added sugar, and glucose syrup. On the other hand, the incorporation of artichoke and broccoli extracts significantly modified the sugar profile compared to the Control. Bread containing broccoli exhibited a moderate increase in fructose and glucose levels, while those containing artichoke demonstrated higher concentrations, particularly in BAE, which exhibited a greater release of fructose and glucose. These effects can be explained by the release of intrinsic sugars from the plant matrices and by the partial hydrolysis of polysaccharides during enzymatic treatment.55,57 Therefore, the observed increase in soluble sugars in these samples does not necessarily indicate greater starch digestibility, but rather the incorporation of simple carbohydrates from the functional ingredients.

3.3. Color and Acidity Profile

Table 4 presents the color and acidity parameters measured for the different GF breads analyzed in this study.

Regarding color measurements (CIEL*a*b*), the addition of broccoli and artichoke extracts, as well as their enzymatically treated extracts, produced significant changes in the color of bread compared to the Control. The incorporation of these extracts led to a decrease in L* and an increase in C and b*, resulting in darker breads with greater color intensity and yellowish tones. Enzymatic treatment further enhanced these effects, significantly decreasing L* and increasing C, a*, and b*, yielding breads that were darker, with more intense colors and pronounced reddish and yellowish tones. These changes can be attributed to the pigments present in the plant matrices, such as chlorophylls and carotenoids. Previous studies have shown that the use of pigmented plant by-products, such as broccoli or artichoke, in bakery formulations affects color parameters, often resulting in strong green or yellowish hues in the final product.58-61 An important factor to consider in the development of new products is the total color difference (ΔE)* relative to the Control, with values above 3 being perceptible to the human eye. In this study, all reformulated breads showed ΔE* values ranging from 5.32 to 15.18, indicating noticeable color changes. Similar observations have been reported in studies using pigmented plant materials, such as green algae (Chlorella vulgaris), which also induced significant color modifications in breads.62 BC was significantly lighter and more yellow than the Control, with higher saturation and hue, resulting in a noticeably brighter appearance. These differences can be attributed to its composition of refined, yellowish flours, whereas the Control, made with buckwheat flour and flax seeds, exhibits a darker, less saturated color.

In terms of acidity, BC exhibited a lower pH than Control, but its total titratable acidity (TTA) and levels of organic acids (L-lactic and acetic) were lower. This finding indicates that the acidity present in commercially available bread is not a consequence of yeast fermentation; rather, it is derived from other technological adjustments incorporated during its industrial formulation. Conversely, the incorporation of broccoli and artichoke extracts resulted in significant increases in TTA, which were more pronounced in enzymatically treated samples (6.41 and 6.82 ml NaOH/10 g, in BBE and BAE, respectively). This reflects a more intense fermentation process, increasing organic acids, particularly acetic acid. Consistent with the TTA results, the samples that exhibited higher concentrations were BBE and BAE, which presented 2.04 and 2.47 g acetic acid/kg of sample. These results can be attributed to enzymatic hydrolysis, which releases sugars and phenolic compounds from plant cell walls that serve as substrates for microbial fermentation during bread making. Recent studies have also shown that the fermentation of fiber- and protein-rich plant by-products with lactic acid bacteria significantly increases titratable acidity (TTA) and the concentration of organic acids.63 These findings demonstrate that the synergistic action of plant extracts and enzymatic treatments effectively stimulate microbial activity, enhancing acid production in bread.64

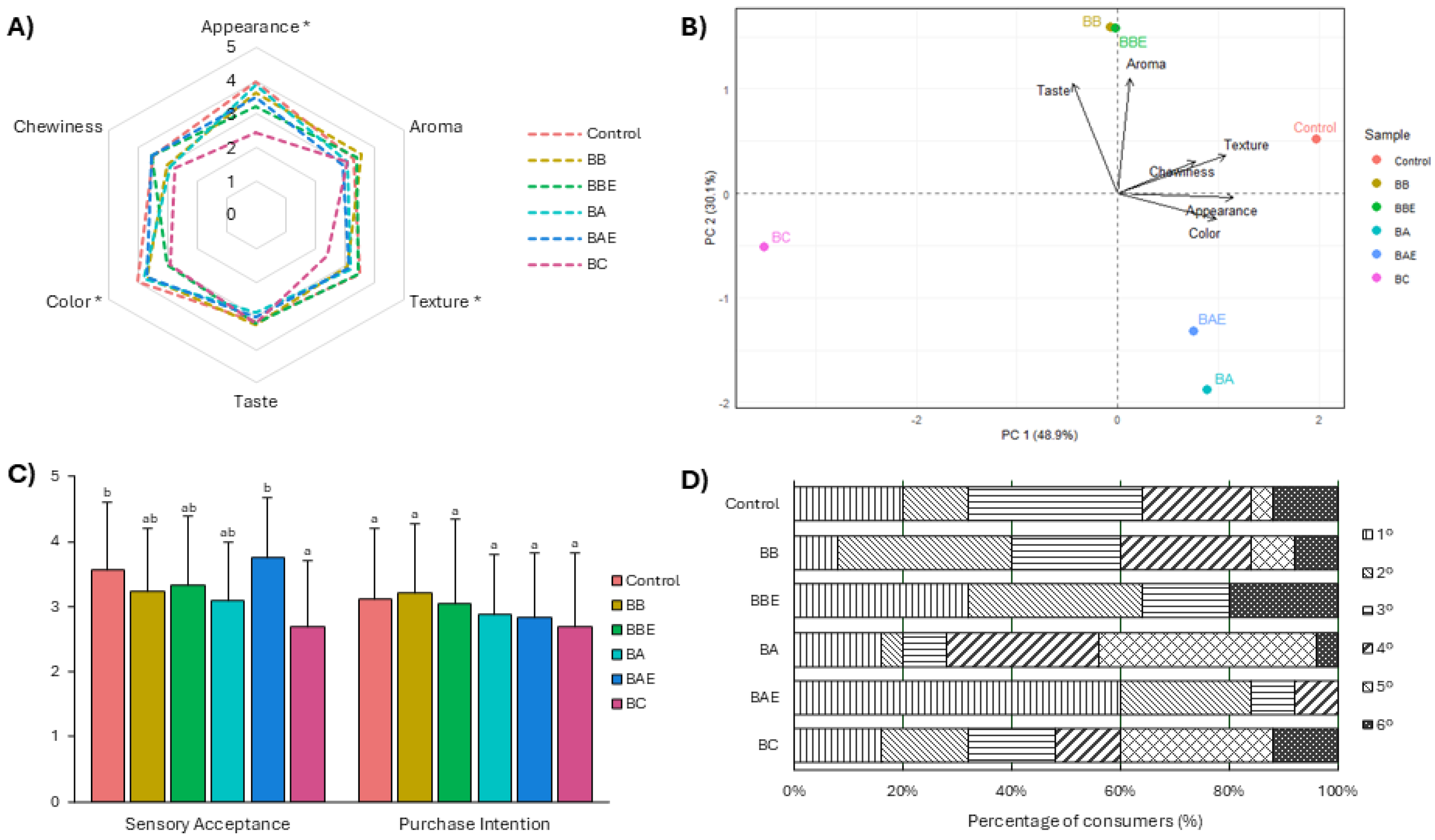

3.4. Sensory Analysis

Figure 2 presents the results of the sensory evaluation and consumer acceptance of the GF bread formulations, assessed by a trained panel. In the sensory attribute analysis (

Figure 2A), significant differences were observed in appearance, color, and texture (p < 0.05). The BC formulation obtained lower scores for appearance and color, whereas the other formulations enriched with broccoli and artichoke extracts exhibited sensory profiles comparable to the Control. To further explore the relationships among samples, a principal component analysis was conducted (

Figure 2B). The biplot indicated that the Control bread was primarily associated with texture and appearance, while the BB and BBE formulations were positively associated with aroma and taste. In contrast, the BC formulation was clearly differentiated from the other treatments, confirming its less favorable sensory profile.

Regarding overall acceptance and purchase intention (

Figure 2C), no significant differences were observed in the latter variable. However, significant differences in overall acceptance were detected (p < 0.05), with the Control and BAE formulations achieving the highest scores, while BC recorded the lowest values. Similar improvements in sensory acceptability have been reported for GF bakery products enriched with plant extracts, including

Moringa Oleifera,

Linum usitatissimum,

Citrus × sinensis, and

Daucus carota.

65-68

Finally, the preference ranking analysis (

Figure 2D) revealed that the BBE and BAE formulations were the most highly valued by consumers, as they concentrated the highest percentages in the top positions. Conversely, the BC and BA formulations were predominantly ranked in the lowest positions, consistent with their lower acceptance levels.

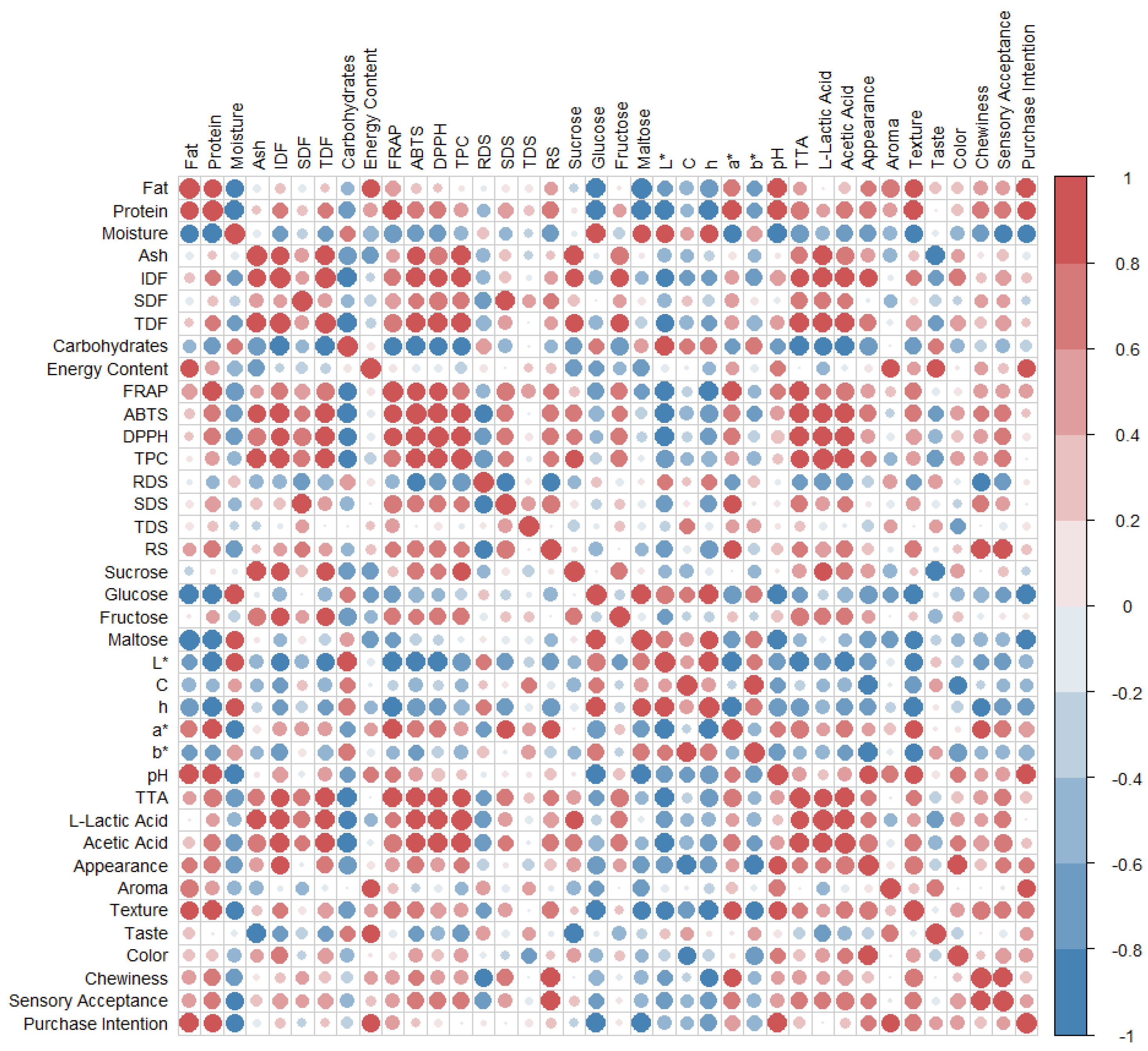

3.5. Pearson Correlations

The results obtained for proximal composition, antioxidant activity, physicochemical properties, and sensory characteristics were subjected to a Pearson correlation analysis (

Figure 3) to verify similarities and relationships between the attributes. The Pearson correlations of the different breads showed a positive correlation between fat and protein with purchase intention (r = 0.97 and r = 0.80, respectively). This association is to be expected, as fat contributes softness, juiciness, and better texture to the crumb, in addition to intensifying the flavor. On the other hand, protein contributes to better structure, volume, and elasticity.

69 This may explain the low results of BC compared to handmade breads, which had better nutritional values and better acceptance. These results are corroborated by the correlation between texture (r = 0.74) and chewiness (r = 0.88) and the sensory acceptance of sourdough breads, attributes in which BC obtained the lowest results compared to the other breads analyzed.

On the other hand, strong positive correlations were found between IDF, TDF, and SDF and the results obtained in antioxidant activity (ABTS, FRAP, and DDPH) and TPC. These associations indicate that breads with higher fiber fractions also had higher levels of bioactive compounds, confirming that broccoli and artichoke extracts had an impact on both the fiber fortification of GF breads and a higher content of bioactive compounds. Moreover, this positive relationship can be attributed to the ability of dietary fiber, particularly the insoluble fraction, to interact with phenolic compounds through both covalent and non-covalent bonds, thereby acting as a binding matrix for these bioactive molecules.70 Furthermore, breads with enzymatically treated extracts (BAE and BBE) showed higher antioxidant values than their corresponding analogs (BA and BB), suggesting that enzymatically treated fiber may facilitate the release of bound phenols during extraction and analysis.

4. Conclusions

The present study expands current knowledge on the use of enzyme-treated vegetable by-products as natural functional ingredients in gluten-free bakery formulations. Specifically, the effects of enzymatically treated artichoke and broccoli extracts were assessed as sustainable alternatives to synthetic additives in gluten-free breads. The incorporation of the by-products represents a sustainable and effective strategy for developing gluten-free (GF) breads with enhanced nutritional, functional, and sensory properties compared with a commercial reference. Among the enzymatic treatments, Celluclast® 1.5L applied to artichoke by-products (BAE) exhibited the most significant overall improvements. This enzyme increased soluble dietary fiber up to 2.75 g/100 g, while markedly modifying starch digestibility by reducing the rapidly digestible fraction by 14% and increasing the slowly digestible fraction by more than 150%, suggesting a lower predicted glycaemic response. Although Viscozyme® L mainly enhanced antioxidant capacity (30% in FRAP and 37% in ABTS), Celluclast® 1.5L achieved a more balanced enhancement across nutritional, functional, and sensory attributes, with BAE showing the highest consumer acceptance.

In contrast, non-treated extracts exerted limited influence on antioxidant activity and product quality. The enzymatic treatment effectively improved the release of bioactive compounds and mitigated undesirable effects on crumb color and structure, demonstrating greater functional performance than the control formulation and the commercial reference bread.

Correlations between compositional and sensory parameters indicated that increased soluble fiber and phenolic content were associated with improved sensory perception and antioxidant performance. Overall, the findings demonstrate the potential of enzyme-treated artichoke and broccoli by-products as sustainable, clean-label ingredients for the formulation of nutritionally improved GF breads, contributing to the valorization of agro-industrial residues and the advancement of circular food production systems. Further research is required to evaluate their impact on oxidative stability and storage performance under industrial conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P., J.Q., and G.N.; methodology, R.P., and J.Q.; validation, J.Q., R.P., P.A., and G.N.; investigation, J.Q., and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Q.; writing—review and editing, J.Q., P.A., R.P., and G.N.; visualization, G.N.; supervision, G.N.; project administration, G.N.; funding acquisition, G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study forms part of the Agroalnext program and was supported by MCIU with funding from European Union Next GenerationEU (PRTR-C17.I1) and by Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia—Fundación Séneca. Jhazmin Quizhpe thanks the finantial support through Research Project PID2021-123628OB-C44 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe”.

Competing interests

The authors affirm that they have no financial interests or personal relationships that could be perceived as influencing the results or conclusions of this study.

References

- Fasano A and Catassi C, Celiac Disease. N Engl J Med 2012, 367, 2419–2426. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khemiri, S; Khelifi, N; Nunes, MC; Ferreira, A; Gouveia, L; Smaali, I; Raymundo, A. Microalgae biomass as an additional ingredient of gluten-free bread: Dough rheology, texture quality and nutritional properties. Algal Res 2020, 50, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl B and Rubio-Tapia A, Epidemiology, Presentation, and Diagnosis of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Vici, G; Belli, L; Biondi, M; Polzonetti, V. Gluten free diet and nutrient deficiencies: A review. Clin Nutr 2016, 35, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, PI; Aronico, N; Santacroce, G; Broglio, G; Lenti, MV. and Sabatino A Di, Nutritional Consequences of Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Diet. Gastroenterol Insights 2024, 15, 878–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D; Miguel, M; Garcés-Rimón, M. Pseudocereals: a novel source of biologically active peptides. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2021, 61, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalver, R; Nieto, G. Developing a functional gluten-free sourdough bread by incorporating quinoa, amaranth, rice and spirulina. LWT 2024, 201, 116162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R; Ahluwalia, P; Sachdev, PA; Kaur, A. Development of gluten-free cereal bar for gluten intolerant population by using quinoa as major ingredient. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 3584–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, M; Netticadan, T; Pierce, GN. Flaxseed: its bioactive components and their cardiovascular benefits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018, 314, H146–H159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantero, L; Salmerón, J; Miranda, J; Larretxi, I; Fernández-Gil, MDP; Bustamante, MÁ; Matias, S; Navarro, V; Simón, E; Martínez, O. Performance of Apple Pomace for Gluten-Free Bread Manufacture: Effect on Physicochemical Characteristics and Nutritional Value. Appl Sci 2022, 12, 5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difonzo, G; de Gennaro, G; Pasqualone, A; Caponio, F. Potential use of plant-based by-products and waste to improve the quality of gluten-free foods. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102, 2199–2211. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M; Bianchi, F; Simonato, B; Rizzi, C; Fontana, A; Tironi, VA. Exploration of grape pomace peels and amaranth flours as functional ingredients in the elaboration of breads: phenolic composition, bioaccessibility, and antioxidant activity. Food Funct 2024, 15, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadj Saadoun, J; Bertani, G; Levante, A; Vezzosi, F; Ricci, A; Bernini, V; Lazzi, C. Fermentation of Agri-Food Waste: A Promising Route for the Production of Aroma Compounds. Foods 2021, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliopoulos, C; Markou, G; Langousi, I; Arapoglou, D. Reintegration of Food Industry By-Products: Potential Applications. Foods 2022, 11, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistical Database (2023). Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Gudiño, I; Casquete, R; Martín, A; Wu, Y; Benito, MJ. Comprehensive Analysis of Bioactive Compounds, Functional Properties, and Applications of Broccoli By-Products. Foods 2024, 13, 3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Martínez, M; Lozano-Sánchez, J; Borrás-Linares, I; Pedreño, MA; Sabater-Jara, AB. Revalorization of Broccoli By-Products for Cosmetic Uses Using Supercritical Fluid Extraction. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quizhpe, J; Ayuso, P; Rosell, M; de los Á; Peñalver, R; Nieto, G. Brassica oleracea var italica and Their By-Products as Source of Bioactive Compounds and Food Applications in Bakery Products. Foods 2024, 13, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Moreno, N; Cimminelli, MJ; Volpe, F; Ansó, R; Esparza, I; Mármol, I; Rodríguez-Yoldi, MJ. and Ancín-Azpilicueta C, Phenolic Composition of Artichoke Waste and Its Antioxidant Capacity on Differentiated Caco-2 Cells. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso, P; Quizhpe, J; Rosell, M; de los, Á; Peñalver, R; Nieto, G. Antioxidant and Nutritional Potential of Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) By-Product Extracts in Fat-Replaced Beef Burgers with Hydrogel Emulsions from Olive Oil. Appl Sci 2024, 14, 10123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, P; Quizhpe, J; Rosell, M; de los, Á; Peñalver, R; Nieto, G. Bioactive Compounds, Health Benefits and Food Applications of Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) and Artichoke By-Products: A Review. Appl Sci 2024, 14, 4940. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, R; Moretto, G; Pellicorio, V; Papetti, A. Globe Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) By-Products in Food Applications: Functional and Biological Properties. Foods 2024, 13, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, ZW; Yu, EZ; Feng, Q. Soluble Dietary Fiber, One of the Most Important Nutrients for the Gut Microbiota. Molecules 2021, 26, 6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader Ul Ain, H; Saeed, F; Ahmed, A; Asif Khan, M; Niaz, B; Tufail, T. Improving the physicochemical properties of partially enhanced soluble dietary fiber through innovative techniques: A coherent review. J Food Process Preserv 2019, 43, e13917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Suárez, MJ; Pérez-Cózar, ML; Redondo-Cuenca, A. Sequential extraction of polysaccharides from enzymatically hydrolyzed okara byproduct: Physicochemical properties and in vitro fermentability. Food Chem 2013, 141, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, YY; Ma, S; Wang, XX; Zheng, XL. Modification and Application of Dietary Fiber in Foods. J Chem 2017, 2017, 9340427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, P; Peñalver, R; Quizhpe, J; Rosell M de los, Á; Nieto, G. Broccoli, Artichoke, Carob and Apple By-Products as a Source of Soluble Fiber: How It Can Be Affected by Enzymatic Treatment with Pectinex® Ultra SP-L, Viscozyme® L and Celluclast® 1.5 L. Foods 2024, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Off J Eur Union 2006, L404, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 19th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen SS. Introduction to Food Analysis, 3–14. In Food analysis (6th ed.). Springer (2024).

- Charrondière UR, Rittenschober D, Nowak V, Wijesinha-Bettoni R, Stadlmayr B, Haytowitz D, and Persijn D, FAO/INFOODS Guidelines for converting units, denominators and expressions, version 1.0. Rome: FAO (2012).

- Englyst, HN; Kingman, SM; Cummings, JH. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur J Clin Nutr 1992, 2, S33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Benzie, IFF; Strain, JJ. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal Biochem 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams, W; Cuvelier, ME; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT- Food Sci Technol 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R; Pellegrini, N; Proteggente, A; Pannala, A; Yang, M; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, VL; Orthofer, R; Lamuela-Raventós, RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8586. Sensory analysis: General guidelines for the selection, training and monitoring of selected assessors and expert sensory assessors. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland (2012).

- Luo, X; Wang, Q; Zheng, B; Lin, L; Chen, B; Zheng, Y; Xiao, J. Hydration properties and binding capacities of dietary fibers from bamboo shoot shell and its hypolipidemic effects in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2017, 109, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebelhack, R; Busch, R; Alt, F; Beah, ZM; Chong, PW. Effects of Cactus Fiber on the Excretion of Dietary Fat in Healthy Subjects: A Double Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Clinical Investigation. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2014, 76, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiden, T; Valduga, E; Zeni, J; Steffens, J. Bioactive Compounds from Artichoke and Application Potential. Food Technol Biotechnol 2023, 61, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadalı, C. Artichoke bracts as fat and wheat flour replacer in cake: optimization of reduced fat and reduced wheat flour cake formulation. J Food Meas Charact 2023, 17, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Peña-Armada, R; Villanueva-Suárez, MJ; Rupérez, P; Mateos-Aparicio, I. High Hydrostatic Pressure Assisted by Celluclast® Releases Oligosaccharides from Apple By-Product. Foods 2020, 9, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, J; Stanojlovic, L; Trierweiler, B; Bunzel, M. Storage related changes of cell wall based dietary fiber components of broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) stems. Food Res Int 2017, 93, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favela-González, KM; Hernández-Almanza, AY; De la Fuente-Salcido, NM. The value of bioactive compounds of cruciferous vegetables (Brassica) as antimicrobials and antioxidants: A review. J Food Biochem 2020, 44, e13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, I; Piccinelli, AL; Celano, R; Campone, L; Gazzerro, P; Russo, M; Rastrelli, L. Pressurized hot water extraction of bioactive compounds from artichoke by-products. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1899–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, K; Djikeng, FT; Esatbeyoglu, T. Retention of bioactives in food processing, pp. 93–121. In Influence of frying, baking and cooking on food bioactives; Esatbeyoglu, T, Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2022; pp. 93–121. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, PPM; Ruviaro, AR; Macedo, GA. Conditions of enzyme-assisted extraction to increase the recovery of flavanone aglycones from pectin waste. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 58, 4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienza, F; Calani, L; Bresciani, L; Mena, P; Rapacioli, S. Optimized Enzymatic Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Verbascum nigrum L.: A Sustainable Approach for Enhanced Extraction of Bioactive Compounds. Appl Sci 2025, 15, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, EV.; Santos, FG; Krupa-Kozak, U; Capriles, VD. Nutritional facts regarding commercially available gluten-free bread worldwide: Recent advances and future challenges. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñalver, R; Ros, G; Nieto, G. Development of Gluten-Free Functional Bread Adapted to the Nutritional Requirements of Celiac Patients. Fermentation 2023, 9, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalver, R; Ros, G; Nieto, G. Development of Functional Gluten-Free Sourdough Bread with Pseudocereals and Enriched with Moringa oleifera. Foods 2023, 12, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuberti, G; Gallo, A. Reducing the glycaemic index and increasing the slowly digestible starch content in gluten-free cereal-based foods: a review. Int J Food Sci Technol 2017, 53, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cairano, M; Condelli, N; Caruso, MC; Cela, N; Tolve, R; Galgano, F. Use of Underexploited Flours for the Reduction of Glycaemic Index of Gluten-Free Biscuits: Physicochemical and Sensory Characterization. Food Bioproc Tech 2021, 14, 1490–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, M; Ruiz, M; Garzon, R; Rosell, CM. Comparison of vegetable powders as ingredients of flatbreads: technological and nutritional properties. Int J Food Sci Technol 2024, 59, 7203–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, V; Melini, F; Salvati, A; Luziatelli, F; Ruzzi, M. Effect of Artichoke Outer Bract Powder Addition on the Nutritional Profile of Gluten-Free Rusks. Foods 2025, 14, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, MM; Lærke, HN; Larsen, FH; Knudsen, KEB; Pedersen, S; Jørgensen, AS. Effect of Enzymatic Treatment of Different Starch Sources on the in Vitro Rate and Extent of Starch Digestion. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, M; Bahmanyar, F; Tahmouzi, S; Nasab, SS; Sadrabad, EK; Mollakhalili-Meybodi, N; Mirmoghtadaie, L. The role of enzymes in gluten-free bakery products: A review of technological and nutritional perspectives. Appl Food Res 2025, 5, 100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M; Spina, A; Summo, C; Strano, MC; Bizzini, M; Allegra, M; Sanfilippo, R; Amenta, M; Pasqualone, A. Waste from Artichoke Processing Industry: Reuse in Bread-Making and Evaluation of the Physico-Chemical Characteristics of the Final Product. Plants 2022, 11, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, M; Conte, P; Piga, A; Del Caro, A. Artichoke By-Product Extracts as a Viable Alternative for Shelf-Life Extension of Breadsticks. Foods 2024, 13, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa-Kozak, U; Drabińska, N; Baczek, N; Šimková, K; Starowicz, M; Jeliński, T. Application of Broccoli Leaf Powder in Gluten-Free Bread: An Innovative Approach to Improve Its Bioactive Potential and Technological Quality. Foods 2021, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa-Kozak, U; Drabińska, N; Rosell, CM; Fadda, C; Anders, A; Jeliński, T; Ostaszyk, A. Broccoli leaf powder as an attractive by-product ingredient: effect on batter behaviour, technological properties and sensory quality of gluten-free mini sponge cake. Int J Food Sci Technol 2019, 54, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, R; Skendi, A; Antonio Lazo-Velez, M; Papageorgiou, M; Rosell, CM. Interaction of dough acidity and microalga level on bread quality and antioxidant properties. Food Chem 2021, 344, 128710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, A; Amendolagine, G; Miani, MG; Rizzello, CG; Verni, M. Effect of Air Classification and Enzymatic and Microbial Bioprocessing on Defatted Durum Wheat Germ: Characterization and Use as Bread Ingredient. Foods 2024, 13, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, P; Costantini, A; Maina, HN; Rizzello, CG; Verni, M; Beni, VD; Polo, A; Katina, K; Cagno, RD; Coda, R. Fermented Brewers’ Spent Grain Containing Dextran and Oligosaccharides as Ingredient for Composite Wheat Bread and Its Impact on Gut Metabolome In Vitro. Fermentation 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourekoua, H; Różyło, R; Gawlik-Dziki, U; Benatallah, L; Zidoune, MN; Dziki, D. Evaluation of physical, sensorial, and antioxidant properties of gluten-free bread enriched with Moringa Oleifera leaf powder. Eur Food Res Technol 2018, 244, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa-Kozak, U; Bączek, N; Capriles, VD; Łopusiewicz, Ł. Novel Gluten-Free Bread with an Extract from Flaxseed By-Product: The Relationship between Water Replacement Level and Nutritional Value, Antioxidant Properties, and Sensory Quality. Molecules 2022, 27, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talens, C; Álvarez-Sabatel, S; Rios, Y; Rodríguez, R. Effect of a new microwave-dried orange fibre ingredient vs. a commercial citrus fibre on texture and sensory properties of gluten-free muffins. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 2017, 44, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzoobi, M; Poor, ZV; Jamalian, J; Farahnaky, A. Improvement of the quality of gluten-free sponge cake using different levels and particle sizes of carrot pomace powder. Int J Food Sci Technol 2016, 51, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollakhalili-Meybodi, N; Sheidaei, Z; Khorshidian, N; Nematollahi, A; Khanniri, E. Sensory attributes of wheat bread: a review of influential factors. J Food Meas Charact 2023, 17, 2172–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S; Zhang, Y; Chen, Q; Fu, X; Huang, Q; Zhang, Bin; Dong, H; Li, C. Exploring the synergistic benefits of insoluble dietary fiber and bound phenolics: Unveiling the role of bound phenolics in enhancing bioactivities of insoluble dietary fiber. Trends Food Sci Technol 2024, 149, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).