Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

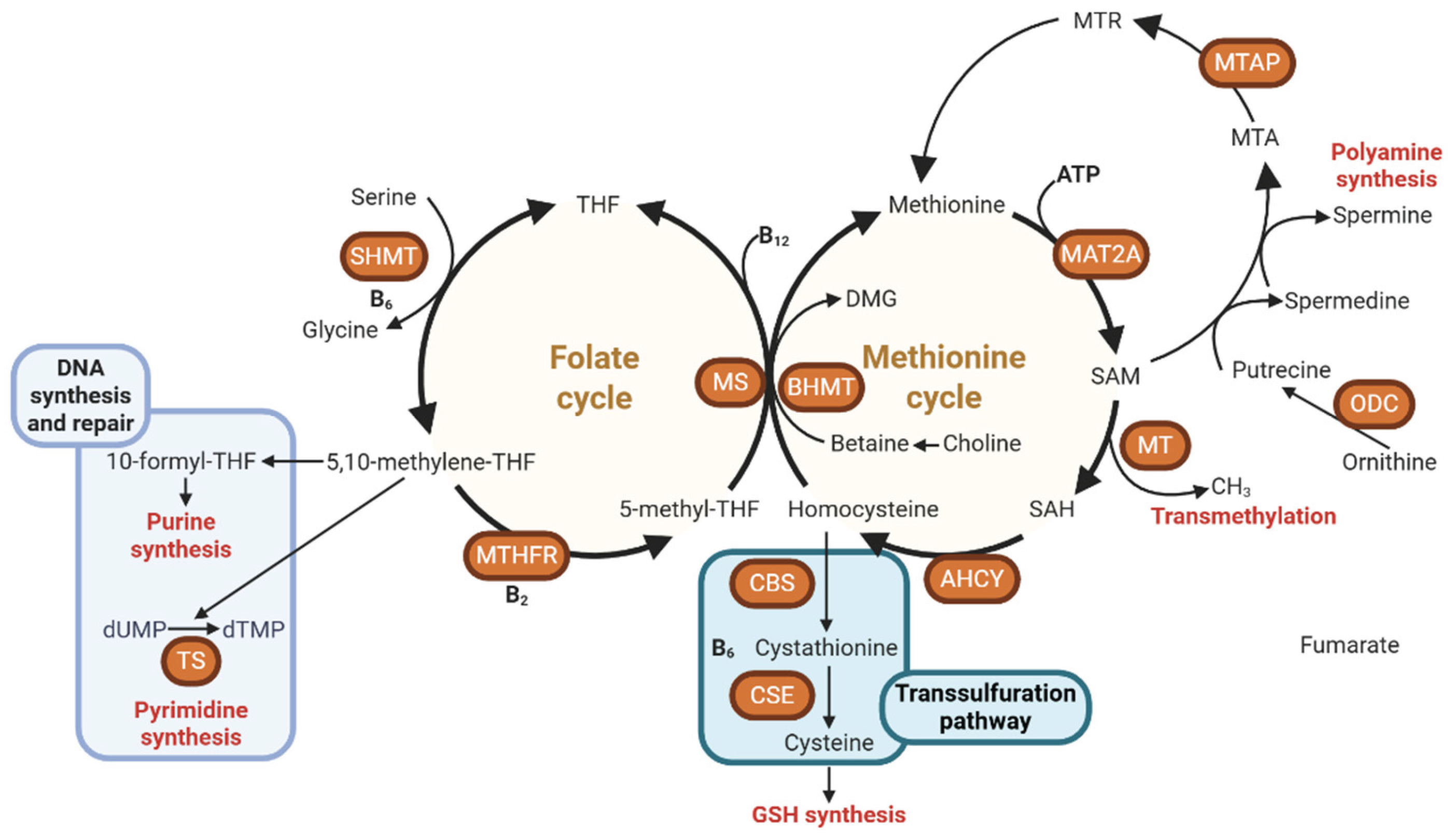

2. Overview of Methyl Donors and One-Carbon Metabolism

2.1. Key Nutrients and Pathways

2.2. Regulation of DNA and Histone Methylation

2.3. Interaction with Other Nutrients and Cofactors

3. The Dual Role of Methyl Donors in Cancer: From Prevention to Progression

3.1. Methyl Donors in Cancer Prevention: Safeguarding Genomic Stability Through Epigenetic Regulation

3.2. Methyl Donors and Cancer Progression: How Over-Supply Can Drive Tumorigenesis

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niculescu, M.D.; Zeisel, S.H. Diet, methyl donors and DNA methylation: interactions between dietary folate, methionine and choline. The Journal of nutrition 2002, 132, 2333s–2335s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekdash, R.A. Methyl Donors, Epigenetic Alterations, and Brain Health: Understanding the Connection. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Robertson, K.D. Chapter 24 - Role of DNA Methylation in Genome Stability. In Genome Stability; Kovalchuk, I., Kovalchuk, O., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, 2016; pp. pp 409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geissler, F.; Nesic, K.; Kondrashova, O.; Dobrovic, A.; Swisher, E.M.; Scott, C.L.; J.W., M. The role of aberrant DNA methylation in cancer initiation and clinical impacts. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2024, 16, 17588359231220511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.M.; Ali, M.M. Methyl Donor Micronutrients that Modify DNA Methylation and Cancer Outcome. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Su, M.; Huang, G.; Luo, P.; Zhang, T.; Fu, L.; Wei, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, G. MTHFR C677T genetic polymorphism in combination with serum vitamin B2, B12 and aberrant DNA methylation of P16 and P53 genes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and esophageal precancerous lesions: a case-control study. Cancer cell international 2019, 19, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsmo, H.W.; Jiang, X. One carbon metabolism and early development: a diet-dependent destiny. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2021, 32, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, L.B.; Gregory, J.F., 3rd. Polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and other enzymes: metabolic significance, risks and impact on folate requirement. The Journal of nutrition 1999, 129, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Tu, B.P. Mechanisms and rationales of SAM homeostasis. Trends Biochem Sci 2025, 50, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mato, J.M.; Martinez-Chantar, M.L.; Lu, S.C. S-adenosylmethionine metabolism and liver disease. Ann Hepatol 2013, 12, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuomo, A.; Beccarini Crescenzi, B.; Bolognesi, S.; Goracci, A.; Koukouna, D.; Rossi, R.; Fagiolini, A. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) in major depressive disorder (MDD): a clinician-oriented systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2020, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, M.A.; Wang, J.C.; Melnyk, S.; Pogribny, I.P.; Jernigan, S.; Collins, M.D.; Santos-Guzman, J.; Swendseid, M.E.; Cogger, E.A.; James, S.J. Intracellular S-adenosylhomocysteine concentrations predict global DNA hypomethylation in tissues of methyl-deficient cystathionine beta-synthase heterozygous mice. The Journal of nutrition 2001, 131, 2811–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, P.M. Choline and betaine in health and disease. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S. Choline, Other Methyl-Donors and Epigenetics. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compher, C.W.; Kinosian, B.P.; Stoner, N.E.; Lentine, D.C.; Buzby, G.P. Choline and vitamin B12 deficiencies are interrelated in folate-replete long-term total parenteral nutrition patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2002, 26, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballal, S.; Banerjee, R. Chapter 19 - Overview of cysteine metabolism. In Redox Chemistry and Biology of Thiols; Alvarez, B., Comini, M.A., Salinas, G., Trujillo, M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. pp 423–450. [Google Scholar]

- Petrova, B.; Maynard, A.G.; Wang, P.; Kanarek, N. Regulatory mechanisms of one-carbon metabolism enzymes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism maintains redox balance during hypoxia. Cancer Discov 2014, 4, 1371–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewski, M.; Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Pisklak, D.M. Mechanistic Insights into SAM-Dependent Methyltransferases: A Review of Computational Approaches. International journal of molecular sciences 2025, 26, 9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, C.; Cai, W.; Li, J.; Rosen, B.P.; Chen, J. Insights into S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase related diseases and genetic polymorphisms. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2021, 788, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struck, A.W.; Thompson, M.L.; Wong, L.S.; Micklefield, J. S-adenosyl-methionine-dependent methyltransferases: highly versatile enzymes in biocatalysis, biosynthesis and other biotechnological applications. Chembiochem 2012, 13, 2642–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, E.L.; Shi, Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, A.J.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Research 2011, 21, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekowska, A.; Benoukraf, T.; Zacarias-Cabeza, J.; Belhocine, M.; Koch, F.; Holota, H.; Imbert, J.; Andrau, J.C.; Ferrier, P.; Spicuglia, S. H3K4 tri-methylation provides an epigenetic signature of active enhancers. Embo j 2011, 30, 4198–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, A.; Konno, M.; Koseki, J.; Taniguchi, M.; Vecchione, A.; Ishii, H. One-carbon metabolism for cancer diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Cancer Letters 2020, 470, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.C.; Maddocks, O.D.K. One-carbon metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer 2017, 116, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragão, M.Â.; Pires, L.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Barros, L.; Calhelha, R.C. Revitalising Riboflavin: Unveiling Its Timeless Significance in Human Physiology and Health. Foods 2024, 13, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.F.; DeRatt, B.N.; Rios-Avila, L.; Ralat, M.; Stacpoole, P.W. Vitamin B6 nutritional status and cellular availability of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate govern the function of the transsulfuration pathway’s canonical reactions and hydrogen sulfide production via side reactions. Biochimie 2016, 126, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, S.; Lee, M.G.; Bin, B.H.; Lee, J.S. Zinc and Its Transporters in Epigenetics. Mol Cells 2020, 43, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Nejdl, L.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Kudr, J.; Krizkova, S.; Smerkova, K.; Dostalova, S.; Vaculovicova, M.; Kopel, P.; Zehnalek, J.; Trnkova, L.; Babula, P.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R. DNA interaction with zinc(II) ions. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2014, 64, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Qin, J.; Liu, M.; Lu, M.; Dong, H.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Lu, K.; Wei, L.; Ma, L. Biosynthesis and bioassays of multifunctional S-adenosylmethionine: A comprehensive review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 519, 164933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R. High Plasma Vitamin B12 and Cancer in Human Studies: A Scoping Review to Judge Causality and Alternative Explanations. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, S.T.; Risch, H.A.; Dubrow, R.; Chow, W.H.; Gammon, M.D.; Vaughan, T.L.; Farrow, D.C.; Schoenberg, J.B.; Stanford, J.L.; Ahsan, H.; West, A.B.; Rotterdam, H.; Blot, W.J.; Fraumeni, J.F. Nutrient intake and risk of subtypes of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 2001, 10, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.C.; Goldstein, B.Y.; Mu, L.; Cai, L.; You, N.C.; He, N.; Ding, B.G.; Zhao, J.K.; Yu, S.Z.; Heber, D.; Zhang, Z.F.; Lu, Q.Y. Plasma folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine and cancers of the esophagus, stomach, and liver in a Chinese population. Nutrition and cancer 2015, 67, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.; Li, Q.; Xin, Y.; Fang, X.; Tian, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, F. Intake of Dietary One-Carbon Metabolism-Related B Vitamins and the Risk of Esophageal Cancer: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranti, E.H.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R.; Weinstein, S.J.; Selhub, J.; Mannisto, S.; Taylor, P.R.; Freedman, N.D.; Albanes, D.; Abnet, C.C.; Murphy, G. Low vitamin B12 increases risk of gastric cancer: A prospective study of one-carbon metabolism nutrients and risk of upper gastrointestinal tract cancer. Int J Cancer 2017, 141, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Freedman, N.D.; Ren, J.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Abnet, C.C.; Park, Y. Intakes of folate, methionine, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 with risk of esophageal and gastric cancer in a large cohort study. British Journal of Cancer 2014, 110, 1328–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainfan, E.; Dizik, M.; Stender, M.; Christman, J.K. Rapid Appearance of Hypomethylated DNA in Livers of Rats Fed Cancerpromoting, Methyl-deficient Diets1. Cancer Research 1989, 49, 4094–4097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, C.M.; Potter, J.D. Folate supplementation: too much of a good thing? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006, 15, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Huang-fu, Y.-c.; Ma, Y.-h. Dietary nutrients involved in one-carbon metabolism and colorectal cancer risk. LabMed Discovery 2024, 1, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartron, P.F.; Hervouet, E.; Debien, E.; Olivier, C.; Pouliquen, D.; Menanteau, J.; Loussouarn, D.; Martin, S.A.; Campone, M.; Vallette, F.M. Folate supplementation limits the tumourigenesis in rodent models of gliomagenesis. Eur J Cancer 2012, 48, 2431–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, A.; Gaudet, F.; Waghmare, A.; Jaenisch, R. Chromosomal instability and tumors promoted by DNA hypomethylation. Science 2003, 300, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervouet, E.; Lalier, L.; Debien, E.; Cheray, M.; Geairon, A.; Rogniaux, H.; Loussouarn, D.; Martin, S.A.; Vallette, F.M.; Cartron, P.F. Disruption of Dnmt1/PCNA/UHRF1 interactions promotes tumorigenesis from human and mice glial cells. PloS one 2010, 5, e11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, M.K.; Jang, H.; Mason, J.B.; Liu, Z.; Crott, J.W.; Smith, D.E.; Friso, S.; Choi, S.-W. Older Age and Dietary Folate Are Determinants of Genomic and p16-Specific DNA Methylation in Mouse Colon12. The Journal of nutrition 2007, 137, 1713–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Pan, D.; Su, M.; Huang, G.; Sun, G. Moderately high folate level may offset the effects of aberrant DNA methylation of P16 and P53 genes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions. Genes & Nutrition 2020, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Su, M.; Xu, D.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Smith, J.D.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Yan, Q.; Song, G.; Lu, Y.; Feng, W.; Wang, S.; Sun, G. Exploring the Interplay Between Vitamin B(12)-related Biomarkers, DNA Methylation, and Gene-Nutrition Interaction in Esophageal Precancerous Lesions. Arch Med Res 2023, 54, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Wang, S.; Su, M.; Sun, G.; Zhu, X.; Ghahvechi Chaeipeima, M.; Guo, Z.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, M. Vitamin B12 may play a preventive role in esophageal precancerous lesions: a case–control study based on markers in blood and 3-day duplicate diet samples. Eur J Nutr 2021, 60, 3375–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.M.; Kamynina, E.; Field, M.S.; Stover, P.J. Folate rescues vitamin B(12) depletion-induced inhibition of nuclear thymidylate biosynthesis and genome instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E4095–e4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.M.; Weir, D.G. The methyl folate trap. A physiological response in man to prevent methyl group deficiency in kwashiorkor (methionine deficiency) and an explanation for folic-acid induced exacerbation of subacute combined degeneration in pernicious anaemia. Lancet 1981, 2, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzbach, C.; Stokstad, E.L. Mammalian methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Partial purification, properties, and inhibition by S-adenosylmethionine. Biochim Biophys Acta 1971, 250, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Friso, S.; Ghandour, H.; Bagley, P.J.; Selhub, J.; Mason, J.B. Vitamin B-12 deficiency induces anomalies of base substitution and methylation in the DNA of rat colonic epithelium. Journal Of Nutrition 2004, 134, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Dangat, K.; Kale, A.; Sable, P.; Chavan-Gautam, P.; Joshi, S. Effects of altered maternal folic acid, vitamin B12 and docosahexaenoic acid on placental global DNA methylation patterns in Wistar rats. PloS one 2011, 6, e17706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, K.D.; Allegrucci, C.; Singh, R.; Gardner, D.S.; Sebastian, S.; Bispham, J.; Thurston, A.; Huntley, J.F.; Rees, W.D.; Maloney, C.A.; Lea, R.G.; Craigon, J.; McEvoy, T.G.; Young, L.E. DNA methylation, insulin resistance, and blood pressure in offspring determined by maternal periconceptional B vitamin and methionine status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 19351–19356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocellin, S.; Briarava, M.; Pilati, P. Vitamin B6 and Cancer Risk: A Field Synopsis and Meta-Analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, M.D.; Tsai, N.P.; Lin, Y.P.; Higgins, L.; Wei, L.N. Vitamin B6 conjugation to nuclear corepressor RIP140 and its role in gene regulation. Nat Chem Biol 2007, 3, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, Z.; Bakhit, S.; Amaefuna, C.N.; Powers, R.V.; Ramana, K.V. Recent Advances on the Role of B Vitamins in Cancer Prevention and Progression. International journal of molecular sciences 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilesi, E.; Tesoriere, G.; Ferriero, A.; Mascolo, E.; Liguori, F.; Argiro, L.; Angioli, C.; Tramonti, A.; Contestabile, R.; Volonte, C.; Verni, F. Vitamin B6 deficiency cooperates with oncogenic Ras to induce malignant tumors in Drosophila. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesoriere, G.; Pilesi, E.; De Rosa, M.; Giampaoli, O.; Patriarca, A.; Spagnoli, M.; Chiocciolini, F.; Tramonti, A.; Contestabile, R.; Sciubba, F.; Verni, F. Vitamin B6 deficiency produces metabolic alterations in Drosophila. Metabolomics 2025, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzio, A.; Merigliano, C.; Gatti, M.; Verni, F. Sugar and chromosome stability: clastogenic effects of sugars in vitamin B6-deficient cells. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinneker, A.; Sola, R.; Lemmen, V.; Castillo, M.J.; Pietrzik, K.; Gonzalez-Gross, M. Vitamin B6 status, deficiency and its consequences--an overview. Nutr Hosp 2007, 22, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, H.; Tsutsui, M.; Ando, J.; Inano, T.; Noguchi, M.; Yahata, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Tsukune, Y.; Masuda, A.; Shirane, S.; Misawa, K.; Gotoh, A.; Sato, E.; Aritaka, N.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Komatsu, N. Vitamin B6 deficiency is prevalent in primary and secondary myelofibrosis patients. Int J Hematol 2019, 110, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Li, X.; Ren, A.; Du, M.; Du, H.; Shu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, W. Choline and betaine consumption lowers cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 35547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.; Cho, E.; Lee, J.E. Association of choline and betaine levels with cancer incidence and survival: A meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.F.; Hogue, S.R.; Salemi, J.L.; Gray, H.L.; Kanetsky, P.A.; Liao, L.M.; Alman, A.C.; Sinha, R.; Byrd, D.A. Associations of Dietary Choline and Betaine With Colorectal Cancer Incidence in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Cohort. Current Developments in Nutrition 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Jacques, P.F.; Dougherty, L.; Selhub, J.; Giovannucci, E.; Zeisel, S.H.; Cho, E. Are dietary choline and betaine intakes determinants of total homocysteine concentration? The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 91, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitter, M.; Norgard, B.; de Vogel, S.; Eussen, S.J.; Meyer, K.; Ulvik, A.; Ueland, P.M.; Nygard, O.; Vollset, S.E.; Bjorge, T.; Tjonneland, A.; Hansen, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.; Racine, A.; Cottet, V.; Kaaks, R.; Kuhn, T.; Trichopoulou, A.; Bamia, C.; Naska, A.; Grioni, S.; Palli, D.; Panico, S.; Tumino, R.; Vineis, P.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; van Kranen, H.; Peeters, P.H.; Weiderpass, E.; Dorronsoro, M.; Jakszyn, P.; Sanchez, M.; Arguelles, M.; Huerta, J.M.; Barricarte, A.; Johansson, M.; Ljuslinder, I.; Khaw, K.; Wareham, N.; Freisling, H.; Duarte-Salles, T.; Stepien, M.; Gunter, M.J.; Riboli, E. Plasma methionine, choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine in relation to colorectal cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Ann Oncol 2014, 25, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogribny, I.P.; James, S.J.; Beland, F.A. Molecular alterations in hepatocarcinogenesis induced by dietary methyl deficiency. Mol Nutr Food Res 2012, 56, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivapurkar, N.; Poirier, L.A. Tissue levels of S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine in rats fed methyl-deficient, amino acid-defined diets for one to five weeks. Carcinogenesis 1983, 4, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehlivets, O.; Malanovic, N.; Visram, M.; Pavkov-Keller, T.; Keller, W. S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase and methylation disorders: yeast as a model system. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1832, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Qin, S.; Luo, S.; Cui, S.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X. Homocysteine induces cytotoxicity and proliferation inhibition in neural stem cells via DNA methylation in vitro. 2014, 281, 2088–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainfan, E.; Poirier, L.A. Methyl groups in carcinogenesis: effects on DNA methylation and gene expression. Cancer Res 1992, 52, 2071s–2077s. [Google Scholar]

- Tsujiuchi, T.; Tsutsumi, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Takahama, M.; Konishi, Y. Hypomethylation of CpG sites and c-myc gene overexpression in hepatocellular carcinomas, but not hyperplastic nodules, induced by a choline-deficient L-amino acid-defined diet in rats. Jpn J Cancer Res 1999, 90, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tryndyak, V.P.; Han, T.; Muskhelishvili, L.; Fuscoe, J.C.; Ross, S.A.; Beland, F.A.; Pogribny, I.P. Coupling global methylation and gene expression profiles reveal key pathophysiological events in liver injury induced by a methyl-deficient diet. Mol Nutr Food Res 2011, 55, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupu, D.S.; Orozco, L.D.; Wang, Y.; Cullen, J.M.; Pellegrini, M.; Zeisel, S.H. Altered methylation of specific DNA loci in the liver of Bhmt-null mice results in repression of Iqgap2 and F2rl2 and is associated with development of preneoplastic foci. Faseb j 2017, 31, 2090–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S.H.; da Costa, K.A.; Albright, C.D.; Shin, O.H. Choline and hepatocarcinogenesis in the rat. Adv Exp Med Biol 1995, 375, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- da Costa, K.A.; Cochary, E.F.; Blusztajn, J.K.; Garner, S.C.; Zeisel, S.H. Accumulation of 1,2-sn-diradylglycerol with increased membrane-associated protein kinase C may be the mechanism for spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in choline-deficient rats. J Biol Chem 1993, 268, 2100–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, K.A.; Garner, S.C.; Chang, J.; Zeisel, S.H. Effects of prolonged (1 year) choline deficiency and subsequent re-feeding of choline on 1,2-sn-diradylglycerol, fatty acids and protein kinase C in rat liver. Carcinogenesis 1995, 16, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.P.; Peng, J.S.; Sun, A.; Tang, Z.H.; Ling, W.H.; Zhu, H.L. Assessment of the effect of betaine on p16 and c-myc DNA methylation and mRNA expression in a chemical induced rat liver cancer model. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, J.D.; Martin, J.J. Methionine metabolism in mammals. Adaptation to methionine excess. J Biol Chem 1986, 261, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina, M.; Korhonen, V.P.; Smith, T.K.; Alakuijala, L.; Eloranta, T.O. Methionine toxicity in the rat in relation to hepatic accumulation of S-adenosylmethionine: prevention by dietary stimulation of the hepatic transsulfuration pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys 1993, 300, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Y.; Wan, X.Y.; Cao, J.W. Dietary methionine intake and risk of incident colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 8 prospective studies involving 431,029 participants. PloS one 2013, 8, e83588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A.C.; Grant, D.J.; Williams, C.D.; Masko, E.; Allott, E.H.; Shuler, K.; McPhail, M.; Gaines, A.; Calloway, E.; Gerber, L.; Chi, J.T.; Freedland, S.J.; Hoyo, C. Associations between Intake of Folate, Methionine, and Vitamins B-12, B-6 and Prostate Cancer Risk in American Veterans. J Cancer Epidemiol 2012, 2012, 957467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigelson, H.S.; Jonas, C.R.; Robertson, A.S.; McCullough, M.L.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E. Alcohol, folate, methionine, and risk of incident breast cancer in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003, 12, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderson, O.S.; Sant, K.E.; Dolinoy, D.C. Nutrition and epigenetics: an interplay of dietary methyl donors, one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation. J Nutr Biochem 2012, 23, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Zhang, W.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, C.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Precise Targeting One-Carbon Metabolism for Potent Cancer Therapy and Metastasis Suppression. Small 2025, 21, e04631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kory, N.; Wyant, G.A.; Prakash, G.; Uit de Bos, J.; Bottanelli, F.; Pacold, M.E.; Chan, S.H.; Lewis, C.A.; Wang, T.; Keys, H.R.; Guo, Y.E.; Sabatini, D.M. SFXN1 is a mitochondrial serine transporter required for one-carbon metabolism. Science 2018, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Vousden, K.H. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducker, G.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metab 2017, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigic, B.; van Roekel, E.; Holowatyj, A.N.; Brezina, S.; Geijsen, A.; Ulvik, A.; Ose, J.; Koole, J.L.; Damerell, V.; Kiblawi, R.; Gumpenberger, T.; Lin, T.; Kvalheim, G.; Koelsch, T.; Kok, D.E.; van Duijnhoven, F.J.; Bours, M.J.; Baierl, A.; Li, C.I.; Grady, W.; Vickers, K.; Habermann, N.; Schneider, M.; Kampman, E.; Ueland, P.M.; Ulrich, A.; Weijenberg, M.; Gsur, A.; Ulrich, C. Cohort profile: Biomarkers related to folate-dependent one-carbon metabolism in colorectal cancer recurrence and survival - the FOCUS Consortium. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weißenborn, A.; Ehlers, A.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Lampen, A.; Niemann, B. A two-faced vitamin: Folic acid - prevention or promotion of colon cancer? Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2017, 60, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Medline, A.; Mason, J.B.; Gallinger, S.; Kim, Y.I. Effects of dietary folate on intestinal tumorigenesis in the apcMin mouse. Cancer Res 2000, 60, 5434–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Sohn, K.J.; Medline, A.; Ash, C.; Gallinger, S.; Kim, Y.I. Chemopreventive effects of dietary folate on intestinal polyps in Apc+/-Msh2-/- mice. Cancer Res 2000, 60, 3191–3199. [Google Scholar]

- Kamen, B. Folate and antifolate pharmacology. Semin Oncol 1997, 24, S18–30–s18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, G.S.; LeBlanc, D.P.; Gagné, R.; Behan, N.A.; Wong, A.; Marchetti, F.; MacFarlane, A.J. Folate Intake Alters Mutation Frequency and Profiles in a Tissue- and Dose-Specific Manner in MutaMouse Male Mice. The Journal of nutrition 2021, 151, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, F.; Nichol, C.A. Inhibition of the growth of an ame-thopterin-refractory tumor by dietary restriction of folic acid. Cancer Res 1962, 22, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Engelbreth-Holm, J.; Rask-Nielsen, R.; Hoff-JØRgensen, E.; Kalckar, H. The growth of Rous sarcoma in folic acid deficient chicks. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1951, 29, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bills, N.D.; Hinrichs, S.H.; Morgan, R.; Clifford, A.J. Delayed tumor onset in transgenic mice fed a low-folate diet. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992, 84, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, S. Some observations on the effect of folic acid antagonists on acute leukemia and other forms of incurable cancer. Blood 1949, 4, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijngaarden, J.P.; Swart, K.M.; Enneman, A.W.; Dhonukshe-Rutten, R.A.; van Dijk, S.C.; Ham, A.C.; Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; van der Zwaluw, N.L.; Sohl, E.; van Meurs, J.B.; Zillikens, M.C.; van Schoor, N.M.; van der Velde, N.; Brug, J.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Lips, P.; de Groot, L.C. Effect of daily vitamin B-12 and folic acid supplementation on fracture incidence in elderly individuals with an elevated plasma homocysteine concentration: B-PROOF, a randomized controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2014, 100, 1578–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbing, M.; Bønaa, K.H.; Nygård, O.; Arnesen, E.; Ueland, P.M.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Rasmussen, K.; Njølstad, I.; Refsum, H.; Nilsen, D.W.; Tverdal, A.; Meyer, K.; Vollset, S.E. Cancer incidence and mortality after treatment with folic acid and vitamin B12. Jama 2009, 302, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliai Araghi, S.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; van Dijk, S.C.; Swart, K.M.A.; van Laarhoven, H.W.; van Schoor, N.M.; de Groot, L.; Lemmens, V.; Stricker, B.H.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; van der Velde, N. Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Supplementation and the Risk of Cancer: Long-term Follow-up of the B Vitamins for the Prevention of Osteoporotic Fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019, 28, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, D.E.; Dhonukshe-Rutten, R.A.; Lute, C.; Heil, S.G.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; van der Velde, N.; van Meurs, J.B.; van Schoor, N.M.; Hooiveld, G.J.; de Groot, L.C.; Kampman, E.; Steegenga, W.T. The effects of long-term daily folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation on genome-wide DNA methylation in elderly subjects. Clinical epigenetics 2015, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. Vitamin B6 Fuels Acute Myeloid Leukemia Growth. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Li, B.; Millman, S.E.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Morris, J.P. t.; Mayle, A.; Ho, Y.J.; Loizou, E.; Liu, H.; Qin, W.; Shah, H.; Violante, S.; Cross, J.R.; Lowe, S.W.; Zhang, L. Vitamin B6 Addiction in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 71–84 e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wang, D.; Shukla, S.K.; Hu, T.; Thakur, R.; Fu, X.; King, R.J.; Kollala, S.S.; Attri, K.S.; Murthy, D.; Chaika, N.V.; Fujii, Y.; Gonzalez, D.; Pacheco, C.G.; Qiu, Y.; Singh, P.K.; Locasale, J.W.; Mehla, K. Vitamin B6 Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Hampers Antitumor Functions of NK Cells. Cancer Discov 2024, 14, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasky, T.M.; White, E.; Chen, C.L. Long-Term, Supplemental, One-Carbon Metabolism-Related Vitamin B Use in Relation to Lung Cancer Risk in the Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) Cohort. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2017, 35, 3440–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Ruiz-Echevarria, M.J. One-Carbon Metabolism in Prostate Cancer: The Role of Androgen Signaling. International journal of molecular sciences 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, M.P.; Kadaveru, K.; Perret, C.; Giardina, C.; Rosenberg, D.W. Dietary Methyl Donor Depletion Suppresses Intestinal Adenoma Development. Cancer Prevention Research 2016, 9, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadaveru, K.; Protiva, P.; Greenspan, E.J.; Kim, Y.I.; Rosenberg, D.W. Dietary methyl donor depletion protects against intestinal tumorigenesis in Apc(Min/+) mice. In Cancer prevention research; Philadelphia, Pa., 2012; Volume 5, pp. 911–920. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, M.P.; Aladelokun, O.; Kadaveru, K.; Rosenberg, D.W. Methyl Donor Deficiency Blocks Colorectal Cancer Development by Affecting Key Metabolic Pathways; Cancer prevention research: Philadelphia, Pa.), 2020; Volume 13, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R.M. Is the Hoffman Effect for Methionine Overuse Analogous to the Warburg Effect for Glucose Overuse in Cancer? In Methionine Dependence of Cancer and Aging: Methods and Protocols; Hoffman, R.M., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2019; pp. pp 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bandaru, N.; Noor, S.M.; Kammili, M.L.; Bonthu, M.G.; Gayatri, A.P.; Kumar, P.K. Methionine restriction for cancer therapy: From preclinical studies to clinical trials. Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapy 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Xu, A.; Zuo, L.; Li, Q.; Fan, F.; Hu, Y.; Sun, C. Methionine Dependency and Restriction in Cancer: Exploring the Pathogenic Function and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, S.; Morehead, L.C.; Bird, J.T.; Graw, S.; Gies, A.; Storey, A.J.; Tackett, A.J.; Edmondson, R.D.; Mackintosh, S.G.; Byrum, S.D.; Miousse, I.R. Characterization of methionine dependence in melanoma cells†. Molecular Omics 2023, 20, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanders, D.; Hobson, K.; Ji, X. Methionine Restriction and Cancer Biology. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, P.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Yan, Y.; Ren, W. Targeting methionine metabolism in cancer: opportunities and challenges. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2024, 45, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M.A.; Coscia, F.; Chryplewicz, A.; Chang, J.W.; Hernandez, K.M.; Pan, S.; Tienda, S.M.; Nahotko, D.A.; Li, G.; Blaženović, I.; Lastra, R.R.; Curtis, M.; Yamada, S.D.; Perets, R.; McGregor, S.M.; Andrade, J.; Fiehn, O.; Moellering, R.E.; Mann, M.; Lengyel, E. Proteomics reveals NNMT as a master metabolic regulator of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nature 2019, 569, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, S.M.; Gao, X.; Dai, Z.; Locasale, J.W. Methionine metabolism in health and cancer: a nexus of diet and precision medicine. Nature reviews. Cancer 2019, 19, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Zhu, D.; Xu, W. Inhibition of MAT2A-Related Methionine Metabolism Enhances The Efficacy of Cisplatin on Cisplatin-Resistant Cells in Lung Cancer. Cell J 2022, 24, 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Morehead, L.C.; Garg, S.; Wallis, K.F.; Simoes, C.C.; Siegel, E.R.; Tackett, A.J.; Miousse, I.R. Increased Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors with Dietary Methionine Restriction in a Colorectal Cancer Model. Cancers 2023, 15, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tan, Y.T.; Chen, Y.X.; Zheng, X.J.; Wang, W.; Liao, K.; Mo, H.Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; Piao, H.L.; Xu, R.H.; Ju, H.Q. Methionine deficiency facilitates antitumour immunity by altering m(6)A methylation of immune checkpoint transcripts. Gut 2023, 72, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Lu, F.; Chang, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Luo, Y.; Lai, Y.; Cao, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Tan, Z.; Cheng, X.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, W. Intermittent dietary methionine deprivation facilitates tumoral ferroptosis and synergizes with checkpoint blockade. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).