Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Growth Conditions

GGMSC Treatment and Cytotoxicity Assay

RNA Isolation and mRNA Library Construction

Illumina Library Preparation and Sequencing

Bioinformatics and Data Analysis

Statistical Analysis

Results

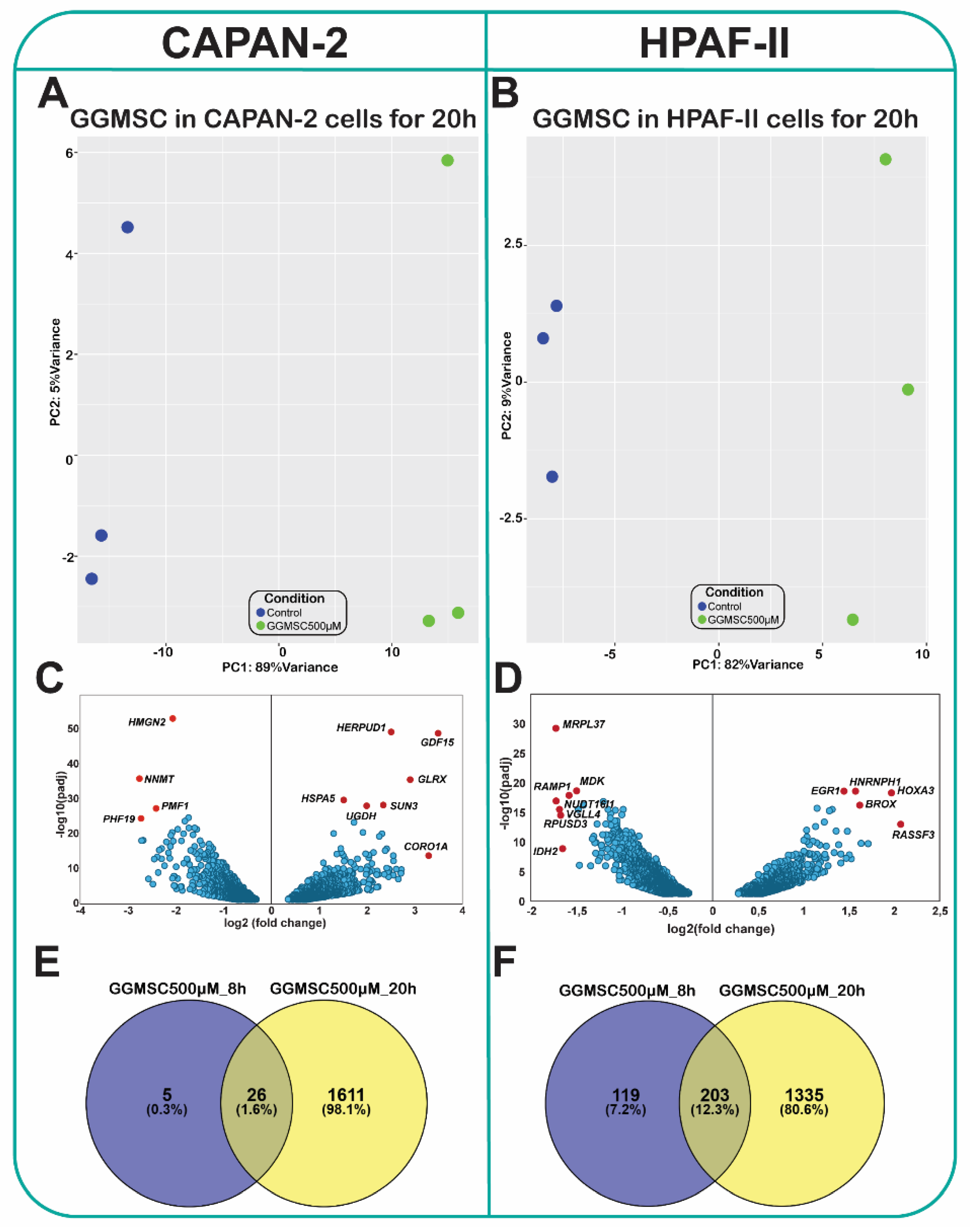

Global Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Distinct Gene Expression Changes upon GGMSC Treatment in PDAC Cell Lines

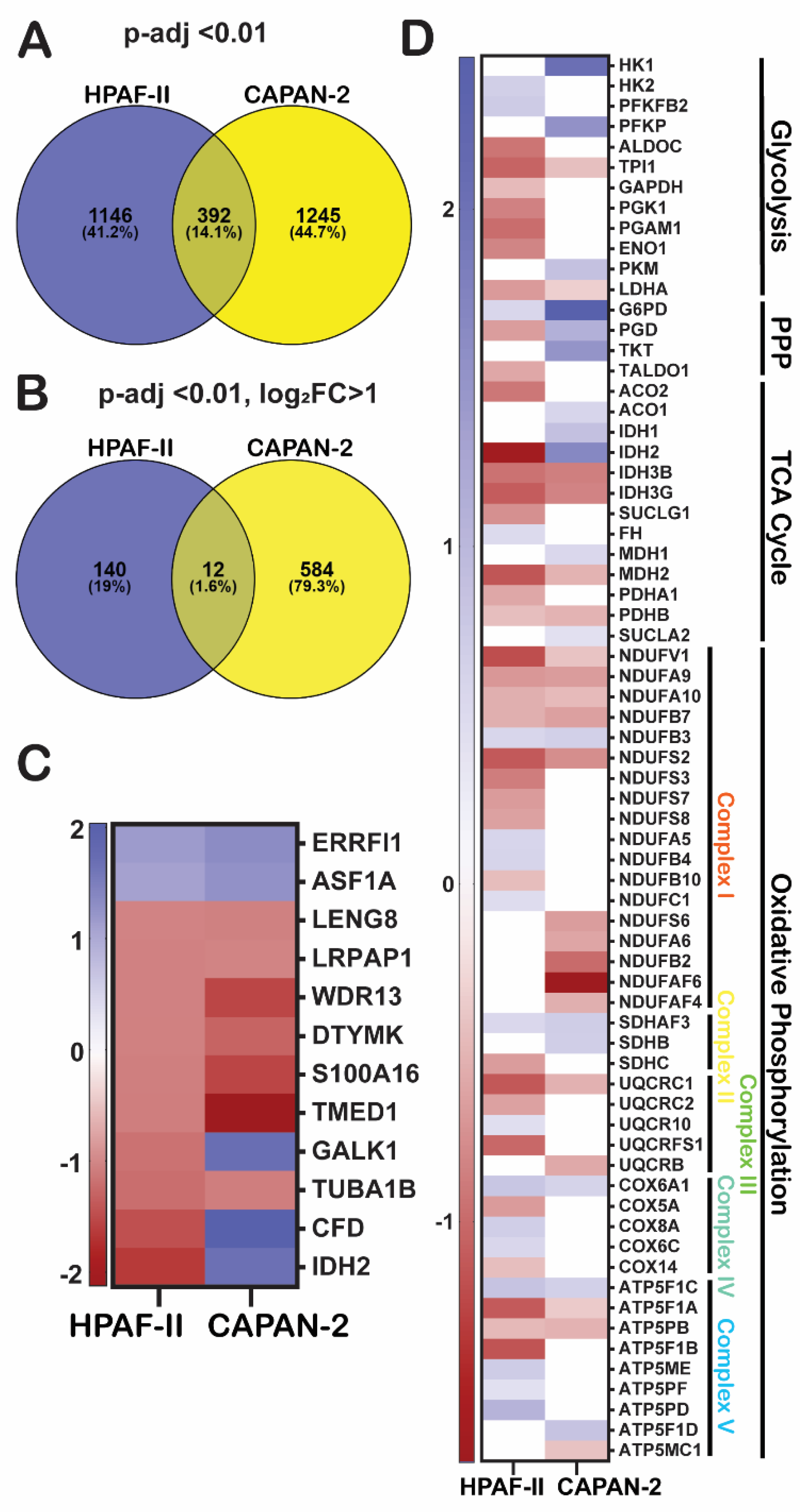

Common and Cell Line-Specific Gene Expression Profiles Induced by GGMSC

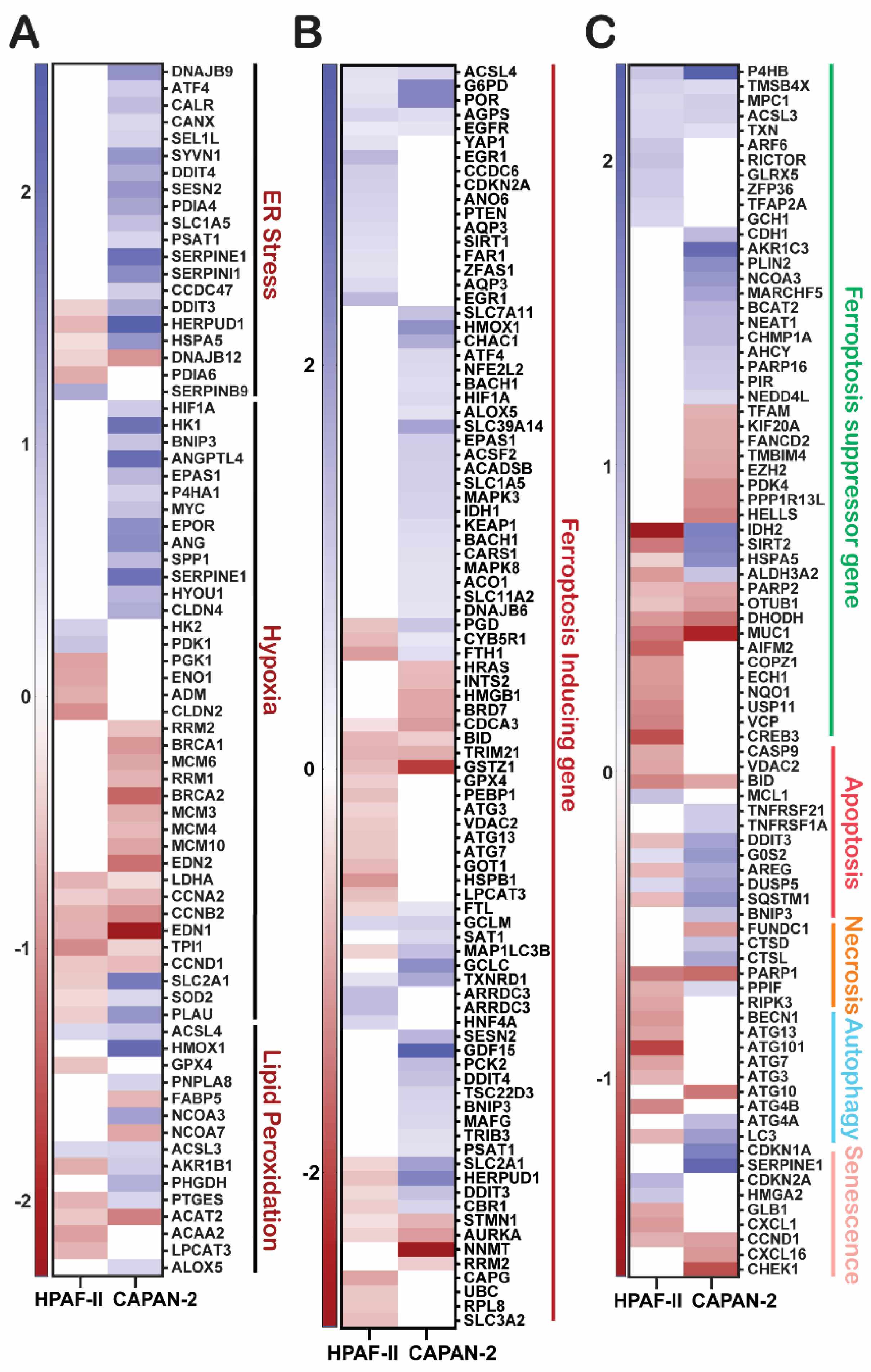

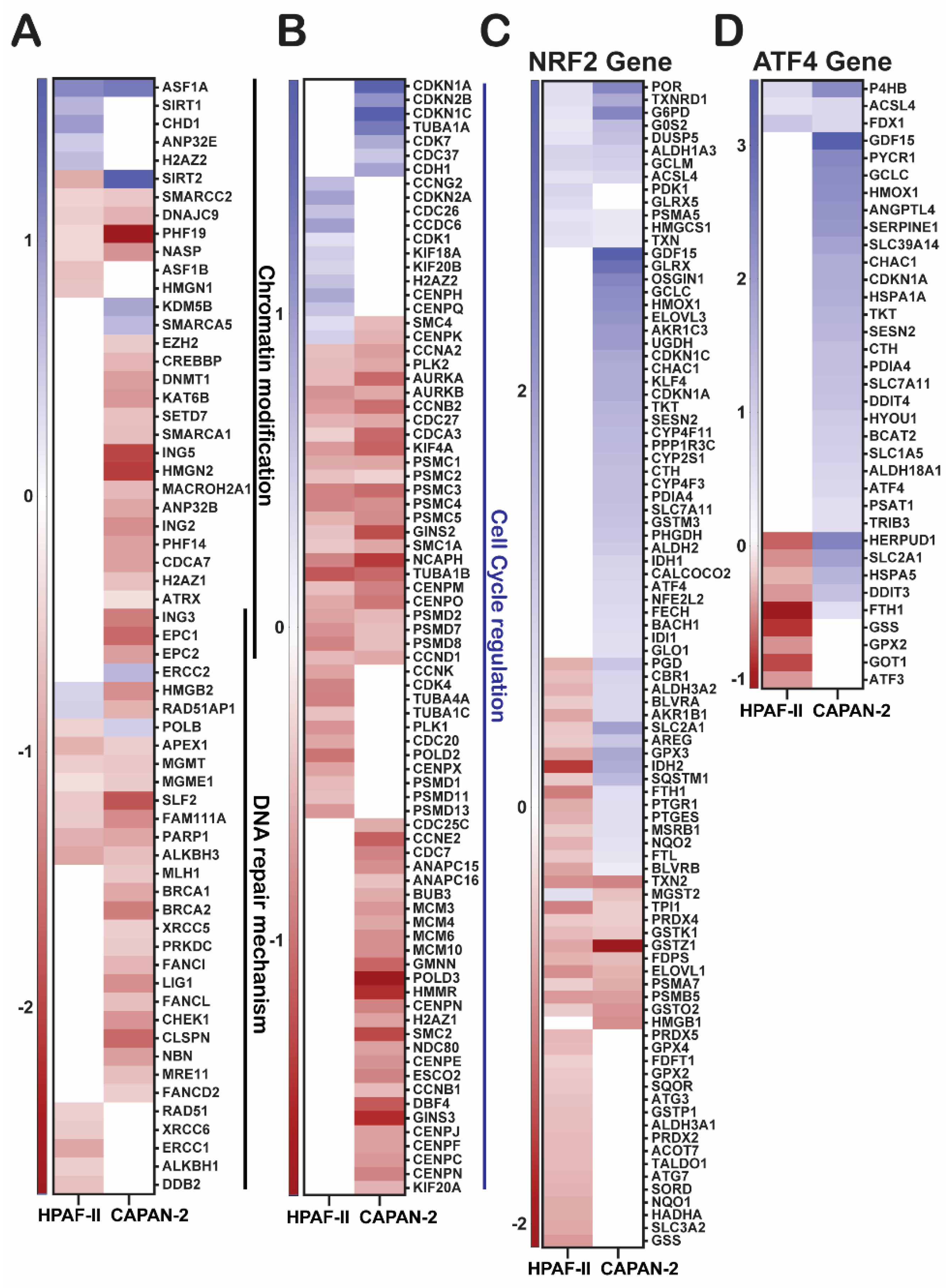

GGMSC Modulates Functional Pathways Associated with Oxidative Stress, Metabolic Rewiring, and Chromatin Regulation

Transcription Factor Responses Mirror Stress Sensitivity and Resistance

GGMSC Induces Metabolic Stress and Ferroptosis in CAPAN-2 Cells

GGMSC Suppresses Epigenetic and Antioxidant Programs While Enhancing Stress Signalling

Discussion:

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| GGMSC | Gamma-Glutamyl-selenomethylselenocysteine |

| MSC | Selenomethylselenocysteine |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| hKYAT1 | Human kynurenine aminotransferase 1 |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylases |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase |

References

- Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. Yea;74(11):2913-21. [CrossRef]

- Kleeff J, Korc M, Apte M, La Vecchia C, Johnson CD, Biankin AV, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. Yea;2(1):16022. [CrossRef]

- Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. Yea;378(9791):607-20. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo M. Pancreatic Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. Yea;362(17):1605-17. [CrossRef]

- Badgley MA, Kremer DM, Maurer HC, DelGiorno KE, Lee HJ, Purohit V, et al. Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor ferroptosis in mice. Science. Yea;368(6486):85-9. [CrossRef]

- Misra S, Boylan M, Selvam A, Spallholz JE, Bjornstedt M. Redox-active selenium compounds--from toxicity and cell death to cancer treatment. Nutrients. Yea;7(5):3536-56. [CrossRef]

- Ip C, Thompson HJ, Zhu Z, Ganther HE. In vitro and in vivo studies of methylseleninic acid: evidence that a monomethylated selenium metabolite is critical for cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Res. Yea;60(11):2882-6.doi:.

- Chen W, Hao P, Song Q, Feng X, Zhao X, Wu J, et al. Methylseleninic acid inhibits human glioma growth in vitro and in vivo by triggering ROS-dependent oxidative damage and apoptosis. Metab Brain Dis. Yea;39(4):625-33. [CrossRef]

- Tung YC, Tsai ML, Kuo FL, Lai CS, Badmaev V, Ho CT, et al. Se-Methyl-L-selenocysteine Induces Apoptosis via Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the Death Receptor Pathway in Human Colon Adenocarcinoma COLO 205 Cells. J Agric Food Chem. Yea;63(20):5008-16. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Lisk D, Block E, Ip C. Characterization of the biological activity of gamma-glutamyl-Se-methylselenocysteine: a novel, naturally occurring anticancer agent from garlic. Cancer Res. Yea;61(7):2923-8.doi:.

- Nigam SN, McConnell WB. Seleno amino compounds from Astragalus bisculcatus. Isolation and identification of gamma-L-glutamyl-Se-methyl-seleno-L-cysteine and Se-methylseleno-L-cysteine. Biochim Biophys Acta. Yea;192(2):185-90. [CrossRef]

- Chun JY, Nadiminty N, Lee SO, Onate SA, Lou W, Gao AC. Mechanisms of selenium down-regulation of androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. Yea;5(4):913-8. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Lee SO, Zhang H, Marshall J, Gao AC, Ip C. Prostate specific antigen expression is down-regulated by selenium through disruption of androgen receptor signaling. Cancer Res. Yea;64(1):19-22. [CrossRef]

- Picelli S, Björklund ÅK, Faridani OR, Sagasser S, Winberg G, Sandberg R. Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nature Methods. Yea;10(11):1096-8. [CrossRef]

- Kallio MA, Tuimala JT, Hupponen T, Klemelä P, Gentile M, Scheinin I, et al. Chipster: user-friendly analysis software for microarray and other high-throughput data. BMC Genomics. Yea;12(1):507. [CrossRef]

- Zhou N, Yuan X, Du Q, Zhang Z, Shi X, Bao J, et al. FerrDb V2: update of the manually curated database of ferroptosis regulators and ferroptosis-disease associations. Nucleic Acids Research. Yea;51(D1):D571-D82. [CrossRef]

- Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. Yea;14(128. [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. Yea;44(W1):W90-7. [CrossRef]

- Xie Z, Bailey A, Kuleshov MV, Clarke DJB, Evangelista JE, Jenkins SL, et al. Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr. Curr Protoc. Yea;1(3):e90. [CrossRef]

- Wong JV, Franz M, Siper MC, Fong D, Durupinar F, Dallago C, et al. Author-sourced capture of pathway knowledge in computable form using Biofactoid. eLife. Yea;10(e68292. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Liu W. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Technol Cancer Res Treat. Yea;19(1533033820962117. [CrossRef]

- Hu H, Jiang C, Ip C, Rustum YM, Lü J. Methylseleninic acid potentiates apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs in androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. Yea;11(6):2379-88. [CrossRef]

- Selvam AK, Jawad R, Gramignoli R, Achour A, Salter H, Bjornstedt M. A Novel mRNA-Mediated and MicroRNA-Guided Approach to Specifically Eradicate Drug-Resistant Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Lines by Se-Methylselenocysteine. Antioxidants (Basel). Yea;10(7). [CrossRef]

- Cao S, Durrani FA, Rustum YM. Selective modulation of the therapeutic efficacy of anticancer drugs by selenium containing compounds against human tumor xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. Yea;10(7):2561-9. [CrossRef]

- Zong WX, Rabinowitz JD, White E. Mitochondria and Cancer. Mol Cell. Yea;61(5):667-76. [CrossRef]

- Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R, Zhang DD. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. Yea;23(101107. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. Yea;22(4):266-82. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao N, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. Yea;11(2):88. [CrossRef]

- Liang D, Minikes AM, Jiang X. Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Mol Cell. Yea;82(12):2215-27. [CrossRef]

- Alim I, Caulfield JT, Chen Y, Swarup V, Geschwind DH, Ivanova E, et al. Selenium Drives a Transcriptional Adaptive Program to Block Ferroptosis and Treat Stroke. Cell. Yea;177(5):1262-79.e25. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Liang X, Zhang H, Dong J, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. ER Stress–Related Genes EIF2AK3, HSPA5, and DDIT3 Polymorphisms are Associated With Risk of Lung Cancer. Frontiers in Genetics. Yea;Volume 13 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- He F, Ru X, Wen T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int J Mol Sci. Yea;21(13). [CrossRef]

- Mehran Ghaderi1, Joakim Dillner1,2, Mikael Björnstedt2,3 and Arun Kumar Selvam3†*. Selenomethylselenocystine Induces Phenotype-Dependent Ferroptosis and Stress-Responses via the NFE2L2–ATF4 Axis in Pancreatic Cancer. SSRN. Yea. [CrossRef]

- Nigam SN, McConnell WB. Seleno amino compounds from Astragalus bisulcatus isolation and identification of γ-L-glutamyl-Se-methyl-seleno-L-cysteine and Se-methylseleno-L-cysteine. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. Yea;192(2):185-90. [CrossRef]

- Ganther HE. Selenotrisulfides. Formation by the reaction of thiols with selenious acid. Biochemistry. Yea;7(8):2898-905. [CrossRef]

- Rooseboom M, Commandeur JN, Vermeulen NP. Enzyme-catalyzed activation of anticancer prodrugs. Pharmacol Rev. Yea;56(1):53-102. [CrossRef]

- West MB, Wickham S, Quinalty LM, Pavlovicz RE, Li C, Hanigan MH. Autocatalytic cleavage of human gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase is highly dependent on N-glycosylation at asparagine 95. J Biol Chem. Yea;286(33):28876-88. [CrossRef]

- Hanigan MH. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase: redox regulation and drug resistance. Adv Cancer Res. Yea;122(103-41. [CrossRef]

- Corti A, Franzini M, Paolicchi A, Pompella A. Gamma-glutamyltransferase of cancer cells at the crossroads of tumor progression, drug resistance and drug targeting. Anticancer Res. Yea;30(4):1169-81.doi:.

- Wang Q, Shu X, Dong Y, Zhou J, Teng R, Shen J, et al. Tumor and serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, new prognostic and molecular interpretation of an old biomarker in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. Yea;8(22):36171-84. [CrossRef]

- Takemura K, Board PG, Koga F. A Systematic Review of Serum γ-Glutamyltransferase as a Prognostic Biomarker in Patients with Genitourinary Cancer. Antioxidants (Basel). Yea;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Whitfield ML, Sherlock G, Saldanha AJ, Murray JI, Ball CA, Alexander KE, et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol Biol Cell. Yea;13(6):1977-2000. [CrossRef]

- Fadaka AO, Bakare OO, Sibuyi NRS, Klein A. Gene Expression Alterations and Molecular Analysis of CHEK1 in Solid Tumors. Cancers (Basel). Yea;12(3). [CrossRef]

| Cell line | Condition | Total DEGs | Upregulation | Downregulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPAN-2 | GGMSC 500 µM-8h | 31 | 19 | 12 |

| CAPAN-2 | GGMSC 500 µM-20h | 1637 | 738 | 899 |

| HPAF-II | GGMSC 500 µM-8h | 322 | 214 | 108 |

| HPAF-II | GGMSC 500 µM-20h | 1538 | 557 | 981 |

| Biological Theme | Pathway | Source | Adjusted p-value | Cell Line | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress / NRF2 | KEAP1-NFE2L2 pathway | Reactome | 7.2E-08 | CAPAN-2 | Up |

| Nuclear events mediated by NFE2L2 | Reactome | 1.0E-07 | CAPAN-2 | Up | |

| Glutathione metabolism | KEGG | 0.0011 | HPAF-II | Down | |

| UPR / ER stress signaling | Protein processing in ER | KEGG | 2.3E-05 | CAPAN-2 | Up |

| Response to ER stress (GO:0034976) | GO | 3.9E-04 | CAPAN-2 | Up | |

| Mitochondrial / metabolic | Mitochondrial matrix (GO:0005759) | GO | 3.9E-05 | CAPAN-2 | Up |

| Aerobic respiration and ETC | Reactome | 3.3E-05 | HPAF-II | Up | |

| Glycolysis / gluconeogenesis | KEGG | 1.8E-05 | HPAF-II | Down | |

| Cell cycle / DNA repair | Cell cycle | Reactome | CAPAN-2: 1.2E-30; HPAF-II: 6.4E-12 | CAPAN-2, HPAF-II | Down |

| DNA replication | Reactome | 1.5E-14 | CAPAN-2 | Down | |

| Chromosome condensation | GO | 1.3E-05 | CAPAN-2 | Down | |

| Chromosome organization | GO | 3.6E-10 | CAPAN-2 | Down | |

| DNA repair | GO | 1.2E-09 | CAPAN-2 | Down | |

| Cell death & survival | Ferroptosis | KEGG | CAPAN-2:0.00013; HPAF-II: 0.0015 | CAPAN-2 (Up), HPAF-II (Down) | Mixed |

| Autophagy | KEGG | 0.00405 | CAPAN-2 | Up | |

| Regulation of apoptosis | Reactome | 6.4E-11 | HPAF-II | Down |

| Transcription Factor | log₂FC (CAPAN-2) | log₂FC (HPAF-II) | Function | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATF4 | +0.77 ↑ | ↔ | Unfolded protein response | Activated only in CAPAN-2 | |

| NFE2L2 | +0.77 ↑ | ↔ | Oxidative stress (NRF2) | Activated in CAPAN-2 | |

| BACH1 | +0.68 ↑ | ↔ | Ferroptosis regulation | May balance NRF2; ferroptosis involvement | |

| MYC | +0.88 ↑ | ↔ | Proliferation / oncogene | Unexpected; could reflect transient response | |

| NFKB1 | -1.35 ↓ | ↔ | NF-κB (survival) | Suppressed in CAPAN-2 | |

| DDIT3 | +1.23 ↑ | -0.44 ↓ | ER stress / apoptosis | Pro-death activation in CAPAN-2; suppressed in HPAF-II | |

| FOS | ↔ | -0.56 ↓ | stress/proliferation | Suppressed in HPAF-II | |

| HOXA3 | ↔ | +1.97 ↑ | Epithelial identity | Upregulated in HPAF-II | |

| HNF4A | ↔ | +0.84 ↑ | Metabolism / differentiation | Supports resistance and metabolic balance | |

| CBX3 | ↔ | +1.01 ↑ | Chromatin regulation | May contribute to epigenetic resistance | |

| CHUK | ↔ | +1.47 ↑ | NF-κB signaling | Pro-survival signaling retained in HPAF-II | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).