2.1. Cell-Specific Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

The human genome-scale metabolic network (GSMN) Recon3D [

18] was employed as a foundation to reconstruct cell-specific genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) for identifying potential biomarkers and enzyme targets that inhibit cancer cell proliferation and mitigate muscle degradation. However, Recon3D lacks essential components, including pathways for the synthesis, degradation, and recycling of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6) and key structural proteins such as myosin, actin, and titin. To bridge this gap, a lumped modeling strategy was adopted, wherein protein sequences were used to define the stoichiometry of the missing reactions. These reactions were subsequently integrated into Rencon3D to form an extended GSMN, as illustrated in . This extended network served as a generic template, which was then customized using RNA-sequence expression data from cancerous and cachectic tissues to reconstruct cell-specific GSMMs for downstream metabolic analysis and therapeutic design.

RNA-Seq expression data for pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma cancer (PDAC) cells were obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession number GSE183795, based on the study by Yang et al. [

19]. This dataset comprises expression profiles from 139 tumor samples and 102 matched adjacent non-tumor tissues, which were used to reconstruct cell-specific genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) for both PDAC and its healthy tissue counterparts (HT), with a particular focus on proinflammatory cytokine production. Additionally, gene expression data for cachectic rectus abdominis muscle from PDAC patients were obtained from the study by Narasimhan, et al. [

20], including 23 cachectic PDAC samples (PDAC-CX) and 11 non-cancer controls. Following reconstruction protocols described by Cheng et al. [

15] and Wang et al. [

17], these datasets were used to develop cell-specific GSMMs to characterize muscle degradation involving key structural proteins such as myosin, actin and titin. The four reconstructed cell-specific GSMMs are provided in Supplementary File S1 through S4.

Figure 1.

Integration of Protein Synthesis, Degradation, and Recycling into the Human Genome-Scale Metabolic Network (Recon3D) to Generate an Extended Network.

Figure 1.

Integration of Protein Synthesis, Degradation, and Recycling into the Human Genome-Scale Metabolic Network (Recon3D) to Generate an Extended Network.

summarizes the number of metabolites (species) and reactions in these reconstructed models. In this context, a ‘species’ refers to a metabolite assigned to one of nine cellular compartments represented in the metabolic model. The four models had 2863 species, and 3741 reactions shared in common, as shown in the overlapping region in . The PDAC model comprised 3669 species, and 5669 reactions, while the PDAC-CX model consisted of 3419 species, and 5543 reactions. Of these, 52 species and 162 reactions were unique to the PDAC model, whereas 87 species and 465 reactions were specific to the PDAC-CX model. The PDAC network retains approximately 62% of the species and 52.9% of the reactions present in the extended Recon3D model. In comparison, PDAC-CX network encompasses about 57.8% of the species and 51.8% of the reactions.

Figure 2.

Summary Statistics of Reconstructed Metabolic Models for Pancreatic Duct Adenocarcinoma Cancer (PDAC), Cachectic PDAC (PDAC-CX), and Their Corresponding Healthy Counterparts (PDAC-HT and PDAC-CX-HT).

Figure 2.

Summary Statistics of Reconstructed Metabolic Models for Pancreatic Duct Adenocarcinoma Cancer (PDAC), Cachectic PDAC (PDAC-CX), and Their Corresponding Healthy Counterparts (PDAC-HT and PDAC-CX-HT).

2.2. Identified Potential Biomarkers

The identification of potential biomarkers is crucial for inhibiting cancer cell growth and mitigating muscle degradation, particularly in conditions like pancreatic cancer-associated cachexia. To achieve this, a computational framework incorporating Parsimonious Metabolite Flow Variability Analysis (pMFVA) combined with differential expression analysis was employed to identify statistically significant changes in metabolite flow rates (p-value < 0.05), as illustrated in . This analytical approach was applied across five distinct nutritional media to assess the impact of nutrient availability on biomarker detection. A key aspect of our approach was to identify “medium-independent biomarkers” by focusing on metabolites that exhibited consistent directional changes, showing either a complete increase or a complete decrease across a panel of five distinct nutrient media used in simulations. This rigorous selection process helps to overcome nutrient dependency, ensuring the robustness and broader applicability of the identified biomarkers. summarizes the number of detected biomarkers under each condition. In the PDAC model, 524, 507, 483, 536, and 433 biomarkers were identified across the five media, DMEM, HAM, HPLM, RPMI, and VMH, respectively. In contrast, the PDAC-CX model yielded 428, 474, 512, 496, and 504 biomarkers across the same media. These differences highlight the sensitivity of metabolic flux distributions to nutrient availability and suggest the potential for partial or complete overlap in metabolite flow between diseased and healthy states.

Table 1.

Number of Identified Biomarkers in PDAC and PDAC-CX Based on Metabolite Flow Rates Across Five Nutritional Media. Abbreviations: CI―complete increase; PI―partial increase, II―inclusive increase; ID―inclusive decrease; PD―partial decrease; CD―complete decrease (as defined in ).

Table 1.

Number of Identified Biomarkers in PDAC and PDAC-CX Based on Metabolite Flow Rates Across Five Nutritional Media. Abbreviations: CI―complete increase; PI―partial increase, II―inclusive increase; ID―inclusive decrease; PD―partial decrease; CD―complete decrease (as defined in ).

| Medium |

Type |

CI |

PI |

II |

ID |

PD |

CD |

Total |

| DMEM |

PDAC |

97 |

240 |

12 |

26 |

4 |

145 |

524 |

| PDAC-CX |

80 |

134 |

16 |

58 |

24 |

116 |

428 |

| HAM |

PDAC |

132 |

212 |

12 |

20 |

6 |

125 |

507 |

| PDAC-CX |

78 |

130 |

20 |

72 |

20 |

154 |

474 |

| HPLM |

PDAC |

125 |

211 |

17 |

32 |

7 |

91 |

483 |

| PDAC-CX |

88 |

175 |

17 |

112 |

26 |

94 |

512 |

| RPMI |

PDAC |

134 |

222 |

11 |

15 |

6 |

148 |

536 |

| PDAC-CX |

95 |

146 |

20 |

89 |

21 |

125 |

496 |

| VMH |

PDAC |

63 |

203 |

10 |

31 |

8 |

118 |

433 |

| PDAC-CX |

140 |

171 |

25 |

43 |

29 |

96 |

504 |

Figure 3.

Workflow for Biomarker Identification Using Differential Expressions Analysis and Parsimonious Metabolite Flow Variability Analysis.

Figure 3.

Workflow for Biomarker Identification Using Differential Expressions Analysis and Parsimonious Metabolite Flow Variability Analysis.

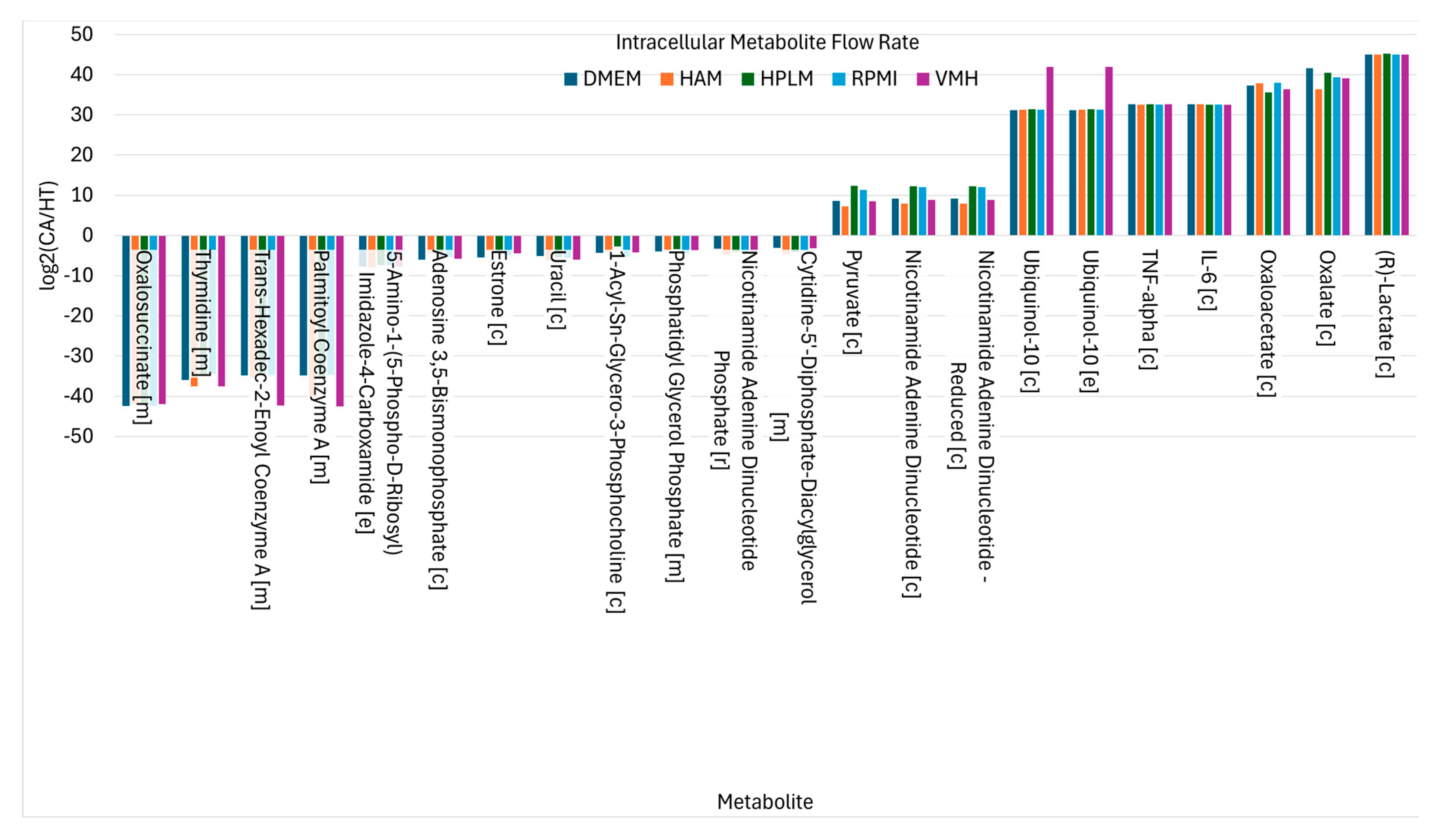

The findings demonstrate that the choice of nutritional medium significantly influences biomarker detection in the PDAC model. To refine biomarker selection, we focused on metabolites that exhibited consistent directional changes, showing either complete increase or complete decrease across all five media, as illustrated in (K). This strategy allowed for the identification of medium-independent biomarkers. presents these medium-independent biomarkers, highlighting those with flow rates that consistently increase or decrease across all media.

Figure 4.

Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC Biomarkers Identified from Intracellular Metabolite Flow Rates.

Figure 4.

Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC Biomarkers Identified from Intracellular Metabolite Flow Rates.

For example, proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, key components of the proinflammatory biosynthetic pathway, consistently show elevated flow rates in the cancer state, reflecting their established roles in tumor-associated inflammation and pancreatic cancer progression [

21,

22]. Metabolites involved in glycolysis and redox balance, including pyruvate, NADH, NAD⁺, and lactate, also exhibit consistently increased fluxes. These changes align with the Warburg effect and alter redox regulation commonly observed in pancreatic cancer cells [

23,

24]. Ubiquinol-10, located in the inner mitochondrial membrane, facilitates electron transport and ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation. Correspondingly, TCA cycle intermediates such as oxalate and oxaloacetate show sustained increases in flux, supporting enhanced nucleotide and lipid biosynthesis. Additionally, oxaloacetate production via GOT1 contributes to maintaining NAD⁺ regeneration, which is critical for sustaining metabolic and redox homeostasis in cancer cells [

21].

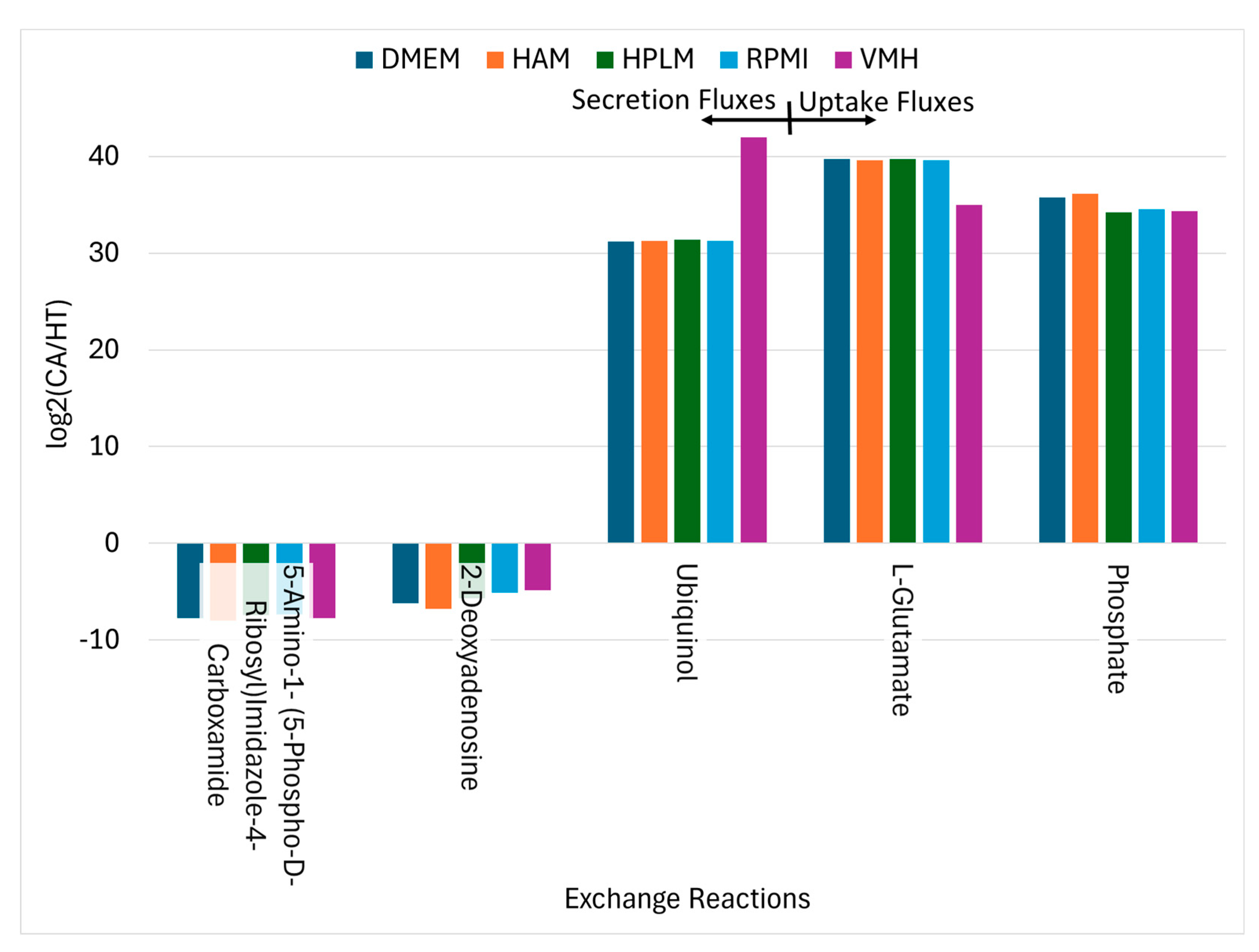

Conversely, twelve metabolites exhibited consistent decreases in PDAC, indicative of disrupted biosynthesis, compromised NADPH-dependent redox defense. Notably, oxalosuccinate depletion in cancer cells likely results from the diversion of TCA cycle intermediates toward anabolic processes and redox balancing. Fatty acyl-CoA derivatives such as palmitoyl-CoA and trans-hexadec-2-enoyl-CoA also decrease, reflecting altered lipid metabolism. Thymidine levels decline, suggesting perturbations in nucleotide metabolism. Meanwhile, uptake fluxes of phosphate, L-glutamate, and ubiquinol increase consistently, as illustrated in , underscoring their importance in supporting cancer cell metabolism. Additionally, secretion of 2-deoxyadenosine is reduced in cancer cells, which may influence nucleotide salvage pathways [

25,

26].

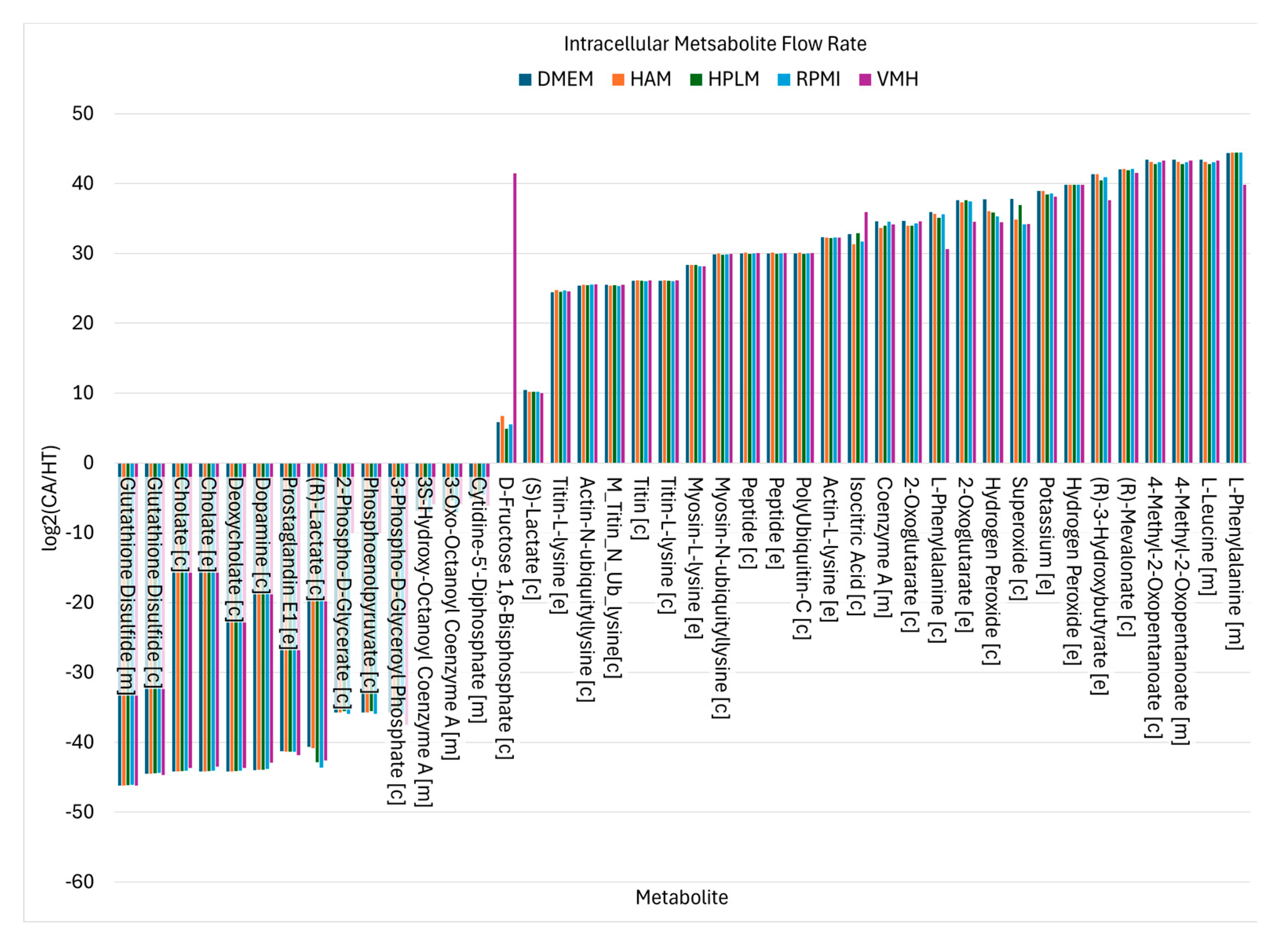

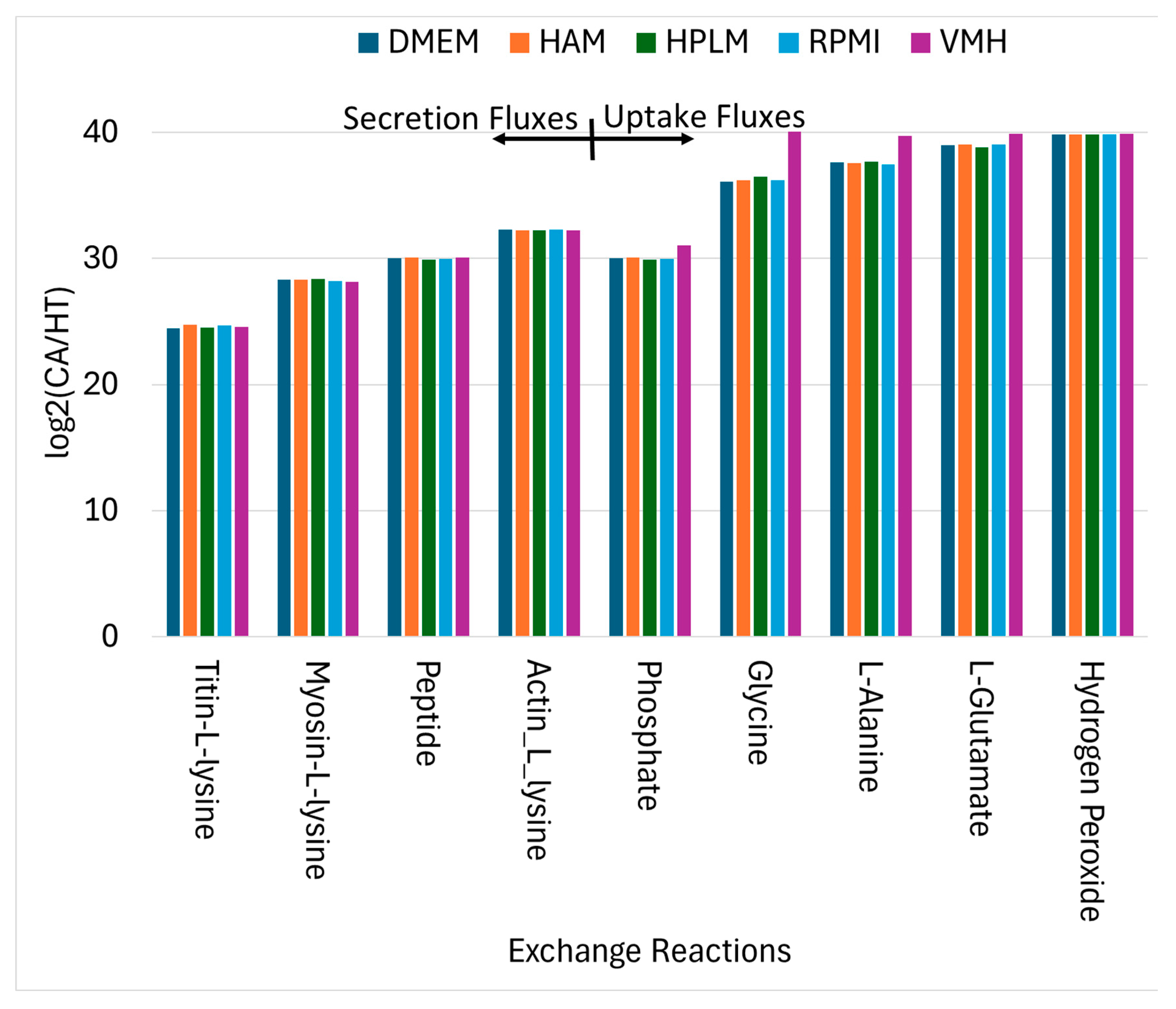

Using similar analytical procedures, the PDAC-CX model identified a set of medium-independent biomarkers, as shown in , comprising 28 metabolites with consistently increased fluxes and 14 metabolites with consistent decreases across all nutritional media. Notably, peptides and degradation products derived from titin, myosin and actin were markedly elevated, indicating enhanced muscle protein catabolism. These degradation products were subsequently secreted into the extracellular space, as illustrated in , aligning with the muscle wasting characteristic of cancer cachexia. Additionally, increased uptake fluxes were observed for L-alanine, glycine, L-glutamate, phosphate and hydrogen peroxide. Phosphate is critical for the biosynthesis of nucleic acids and membrane phospholipids, its elevated uptake in proliferative disease state such as cancer supports increased nucleotide synthesis and membrane production, thereby promoting anabolic growth. In contrast, increased uptake of hydrogen peroxide contributes to redox imbalance. While low to moderate levels of hydrogen peroxide act as signaling molecules to promote cellular adaptation and survival, excessive accumulation induces oxidation stress, leading to macromolecular damage and potentially triggering cell death.

Figure 5.

Uptake Reactions and Secretion Reactions Identified as Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC Biomarkers.

Figure 5.

Uptake Reactions and Secretion Reactions Identified as Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC Biomarkers.

Figure 6.

Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC-CX Biomarkers Identified from Intracellular Metabolite Flow Rates.

Figure 6.

Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC-CX Biomarkers Identified from Intracellular Metabolite Flow Rates.

Figure 7.

Uptake and Secretion Reactions Identified as Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC-CX Biomarkers.

Figure 7.

Uptake and Secretion Reactions Identified as Nutritional Medium-Independent PDAC-CX Biomarkers.

2.3. Enzyme Targets Predicted Using Constraint-Based Modeling

The Anticancer Target Discovery (ACTD) platform proposed by Wang and Zhang [

17], as illustrated in , was employed to identify enzyme targets for treating PDAC and PDAC-CX across five distinct nutritional media. The predicted targets are detailed in Supplementary File S1. In this framework, cell viability (CV) and metabolic deviation (MD) were used as dual decision-making criteria to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of each enzyme target. For PDAC, five objective functions were simultaneously minimized to determine CV, with membership grade ranging from 0 and 1. The highest priority was assigned to abolishing biomass production, while additional objectives included the reduction of ATP synthesis and proinflammatory cytokine production (IL6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α).

For PDAC-CX, the primary objective was to minimize myosin degradation, followed by reduction in actin and titin degradation―reflecting muscle preservation goals in cachexia management. Each candidate target was further evaluated for its impact on healthy tissue (denoted as PB, perturbed by treatment), by examining alterations in flux distributions. The MD metric―normalized between 0 and 1 using a linear membership function―quantified the similarity between PB and healthy tissue (HT), and the dissimilarity between PB and the corresponding diseased models. This metric served as proxy for predicting the potential side effects associated with each enzyme target.

Using the ACTD platform, twenty-seven single-enzyme targets for PDAC treatment were identified across five distinct nutritional media, as detailed in Supplementary File S5. Several targets resulted in zero cell viability (CV) in certain media, indicating complete treatment failure under those specific conditions, However, other targets were able to inhibit cancer growth. These findings suggest that the efficacy of the identified targets is dependent on the nutritional environment. Notably, none of these single-enzyme targets were effective against the PDAC-CX model. Conversely, thirty single-enzyme targets identified for PDAC-CX treatment failed to produce therapeutic effects in PDAC, highlighting the context-specific nature of these interventions. To address this limitation, the ACTD platform was extended to a combinatorial targeting strategy aimed at identifying enzyme target pairs effective against both PDAC and PDAC-CX. Some of these combinations, also listed in Supplementary File S5, yielded zero CV but remained sensitive to medium conditions. Among them, seven target combinations emerged as robust candidates exhibiting medium-independent efficacy. The average values of cell viability (CV) and metabolic deviation (MD) values for these medium-independent combinations in treating both PDAC and PDAC-CX are summarized in .

Figure 8.

Framework for Anticancer Target Discovery Using Constraint-Based Modeling and Fuzzy Multiobjective Optimization. (A-E) Reconstruction of cell-specific GSMMs and gene–protein–reaction associations, as described in . (F) Formulation of a parsimonious multiobjective flux balance analysis (pMOFBA) problem for treated CA cells. (G) Formulation of a pMOFBA for perturbed HT cells. (H) Calculation of metabolic flux distributions in treated CA cells for each anticancer candidate by solving the pMOFBA model. (I) Calculation of metabolic flux distributions in perturbed HT cells for each anticancer candidate via pMOFBA. (J) Derivation of the metabolic template of CA cells from clinical data (if available) or baseline pMOFBA without target inregulation. (K) Derivation of the metabolic template of HT cells from clinical data (if available) or baseline pMOFBA. (L) Transformation of fuzzy multiobjective functions into a fuzzy decision score (ηD) using fuzzy set theory. (M) Evaluation of each anticancer candidate’s fitness based on ηD to guide target selection. (N) Generation of new anticancer candidates using a nested hybrid differential evolution algorithm if decision criteria are unmet, with iteration through Steps (F) to (N). (O) Identification of optimal anticancer targets when the decision criterion is satisfied.

Figure 8.

Framework for Anticancer Target Discovery Using Constraint-Based Modeling and Fuzzy Multiobjective Optimization. (A-E) Reconstruction of cell-specific GSMMs and gene–protein–reaction associations, as described in . (F) Formulation of a parsimonious multiobjective flux balance analysis (pMOFBA) problem for treated CA cells. (G) Formulation of a pMOFBA for perturbed HT cells. (H) Calculation of metabolic flux distributions in treated CA cells for each anticancer candidate by solving the pMOFBA model. (I) Calculation of metabolic flux distributions in perturbed HT cells for each anticancer candidate via pMOFBA. (J) Derivation of the metabolic template of CA cells from clinical data (if available) or baseline pMOFBA without target inregulation. (K) Derivation of the metabolic template of HT cells from clinical data (if available) or baseline pMOFBA. (L) Transformation of fuzzy multiobjective functions into a fuzzy decision score (ηD) using fuzzy set theory. (M) Evaluation of each anticancer candidate’s fitness based on ηD to guide target selection. (N) Generation of new anticancer candidates using a nested hybrid differential evolution algorithm if decision criteria are unmet, with iteration through Steps (F) to (N). (O) Identification of optimal anticancer targets when the decision criterion is satisfied.

The results reveal that the identified combinations comprise eight enzyme targets, including five individually encoded enzymes and one enzyme complex―namely the RNF20–RNF40 complex. Among these, four enzymes (SLC29A2, RNF20–RNF40, CRLS1, and SGMS1) are knocked out, while two enzymes (CERK and PIKFYVE) are upregulated to achieve therapeutic efficacy. In the PDAC model, the average cell viability (CV) ranged from 0.66 to 0.98, and the metabolic deviation (MD) from 0.32 to 0.43. In the PDAC-CX model, CV ranged from 0.86 to 1.0 and MD from 0.25 to 0.33. Higher values of CV and MD reflect increased therapeutic efficacy and reduced potential side effects. Collectively, the eight identified target combinations represent effective therapeutic strategies for concurrently treating both PDAC and PDAC-CX cells. Furthermore, the CV and MD metrics provide a quantitative basis for selecting optimal trade-off between efficacy and safety.

SLC29A2 (solute carrier family 29 member 2), also known as ENT2, is a bidirectional transporter that regulates intracellular homeostasis by mediating nucleosides and nucleobase uptake and efflux. Its knockout disrupts nucleotide salvage pathways, impairs cellular energy balance, and inhibits cancer cell proliferation. In the PDAC-CX model, the RNF20–RNF40 complex functions as a key E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for ubiquitinating protein-L-lysine residues―including those in myosin, actin, and titin. Knockout of this complex may impair lysine and ubiquitin recycling, thereby promoting enhanced protein degradation (). Consequently, dual targeting of SLC29A2 and the RNF20–RNF40 complex represents a promising therapeutic strategy for PDAC and PDAC-CX cells.

Knockout of the SGMS1 (sphingomyelin synthase 1) gene leads to significant metabolic disruption by impairing sphingolipid metabolism, thereby reducing cancer cell viability and inhibiting tumor progression. SGMS1 catalyzes the synthesis of sphingomyelin by transferring a phosphocholine group from phosphatidylcholine to N-acylsphingosine. Similarly, knockout of the CRLS1 (cardiolipin synthase 1) gene impairs mitochondrial lipid metabolism by blocking cardiolipin biosynthesis, which involves the conversion of cytidine-5′-diphosphate-diacylglycerol and phosphatidylglycerol. Both sphingomyelin and cardiolipin are critical lipid components essential for biomass synthesis in the PDAC model. Consequently, knockout of either SGMS1 or CRLS1 abolishes biomass production. Therefore, co-targeting SGMS1 or CRLS1 in combination with the RNF20-RNF40 complex constitutes a promising therapeutic strategy for the simultaneous treatment of PDAC and PDAC-CX cells.

Upregulation of CERK (ceramide kinase) or PIKFYVE (phosphoinositide kinase) alone is insufficient to prevent muscle degradation in the PDAC-CX model across all five nutritional media, as shown in Supplementary File S5. CERK catalyzes the phosphorylation ceramide to generate ceramide-1-phosphate (C1P). Deletion or downregulation of CERK results in ceramide accumulation, promoting pro-catabolic and pro-apoptotic signaling in muscle cells. This effect is particularly detrimental in PDAC-associated cachexia, where inflammation, energy imbalance, and lipid metabolism are already dysregulated. Although CERK upregulation may exert protective effects by shifting sphingolipid balance toward C1P, the current dataset provides no direct evidence supporting this outcome. Nevertheless, previous studies have associated CERK deficiency with muscle atrophy, underscoring its therapeutic potential for preserving muscle mass under cachectic conditions [

27,

28,

29].

Similarly, upregulation of PIKFYVE may modulate muscle metabolism through its involvement in insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake. While most existing studies emphasize the detrimental effects of PIKFYVE deficiency―such as impairs insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis [

30]―its upregulation could potentially enhance these metabolic pathways, thereby contributing muscle preservation. However, direct evidence supporting this effect remains limited. Consequently, combined the upregulation of CERK or PIKFYVE with the knockout of SLC29A2, SGMS1 or CRLS1 may constitute a more effective therapeutic strategy for concurrently targeting both PDAC and PDAC-CX cells across all five media conditions, as illustrated in

Figure 9.

Average Cell Viability (CV) and Metabolic Deviation (MD) of Medium-Independent Target Combinations for the Treatment of PDAC and PDAC-CX Cells.

Figure 9.

Average Cell Viability (CV) and Metabolic Deviation (MD) of Medium-Independent Target Combinations for the Treatment of PDAC and PDAC-CX Cells.