Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

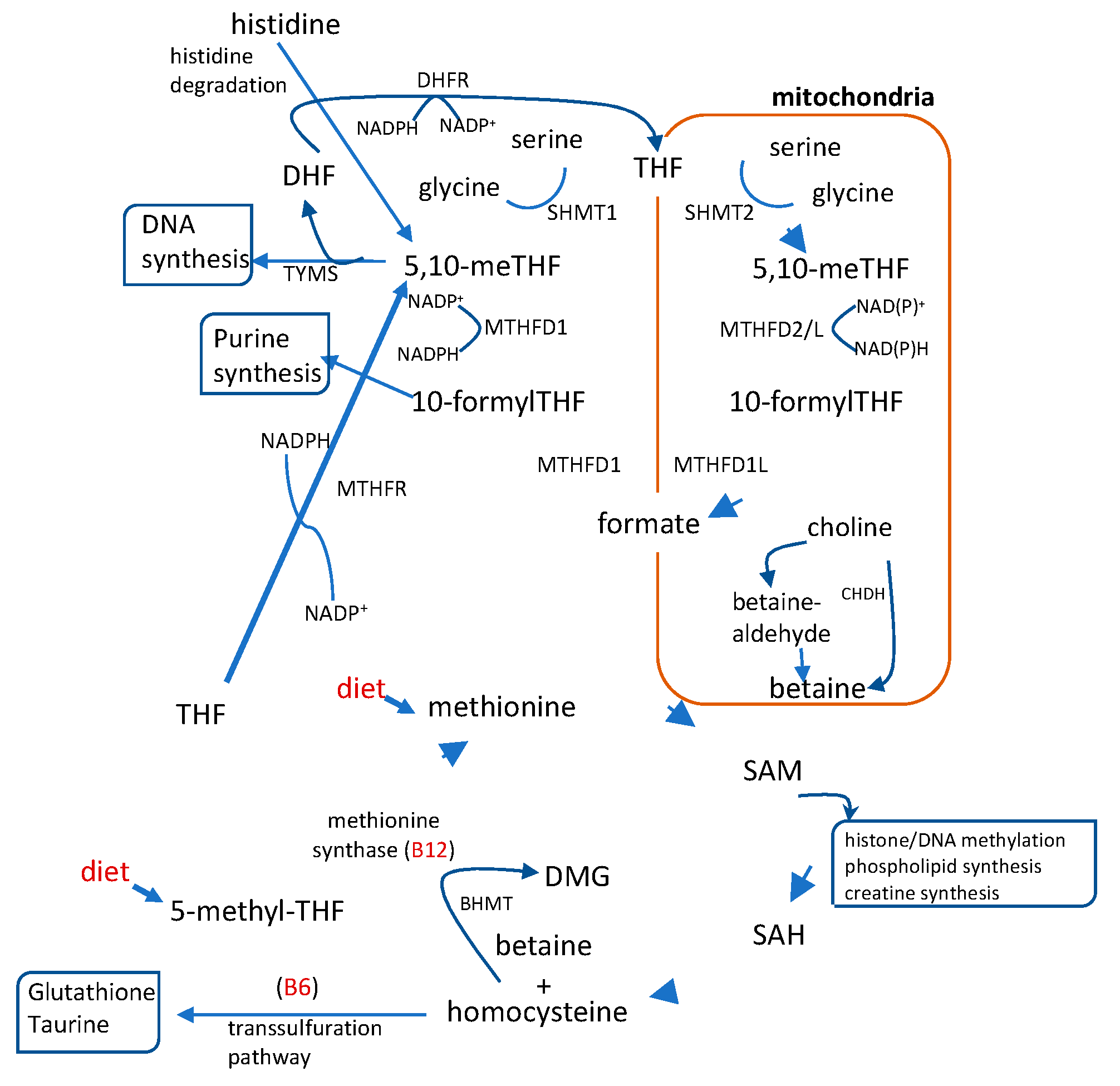

1. Introduction

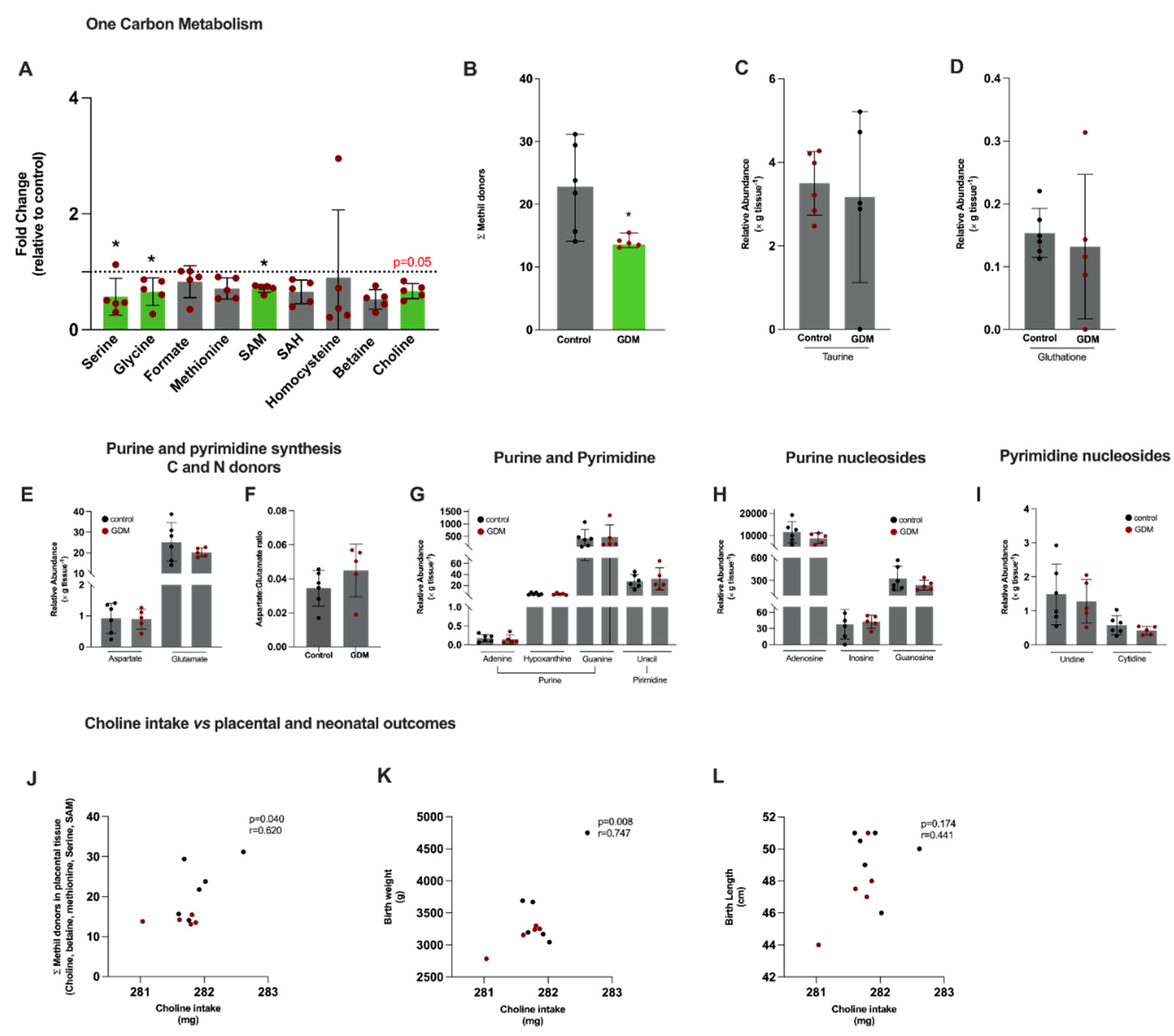

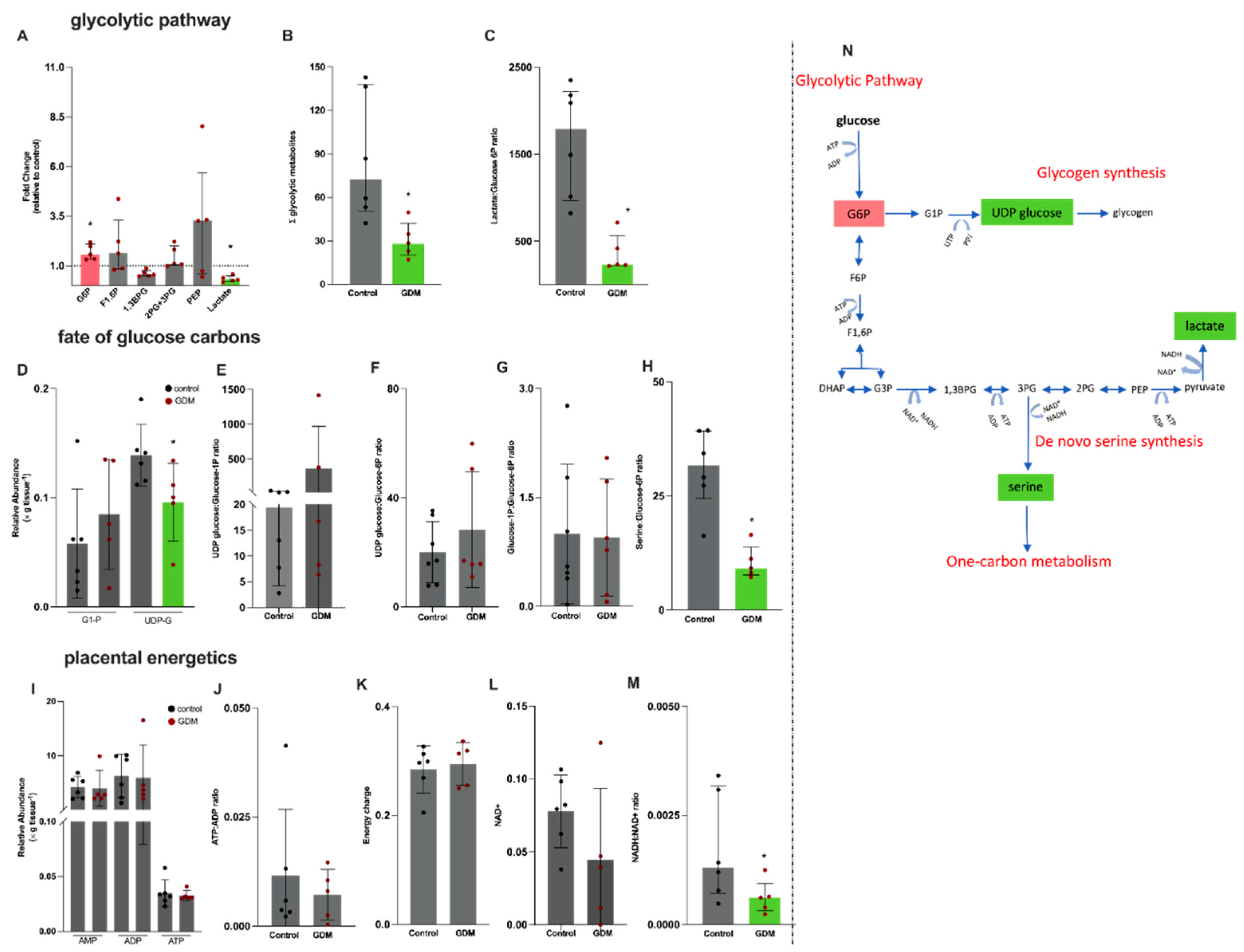

2. Results

2.1. Mothers Characteristics

| Variables | Median (p25-p75) a or % frequency (n)b | ||

| Control (n=13) | Gestational diabetes mellitus (n=11) | p value | |

| Age (years) a | 28 (23.5-32.5) | 31 (27-37) | 0.26 |

| Pre-gestational BMI (kg/m²) a Normal weight b Overweight b Obesity b |

25.7 (22.5-29.7) 38 (5) 38 (5) 24 (3) |

28.3 (25.1-34.7) 18 (2) 36 (4) 46 (5) |

0.15 |

| Total weight gain (kg) a Adequate b Insufficient b Excessive b |

14.2 (6.9-18.8) 46 (6) 23 (3) 31 (4) |

8.8 (6.6-12.9) 64 (7) 27 (3) 9 (1) |

0.13 |

| Insulin therapy b Blood glucose (mg/dL) a Fasting Post-prandial |

n/a - - |

73 (8) 89 (87.5-97.0) 112 (94.5-123.1) |

n/a n/a n/a |

2.2. Dietary Data

| Dietary intake1 |

Prevalence of Inadequacy % (n) |

Reference value2 |

p value* |

|||

| Control (n=13) | GDM (n=11) | Control (n=13) | GDM (n=11) | |||

|

Vitamins Folic Acid (μg) |

200.2 ± 74.2 |

257.4 ± 81.7 |

100 (13) |

100 (11) |

520 µg |

0.08 |

|

Vitamin B12 (μg) Vitamin B6 (mg) Methyl Donors Choline (mg) Betaine (mg) Methionine (mg) Cystine (mg) ∑ Methyl donors (mg) |

4.6 ± 1.6 1.5 ± 0.4 281.8 ± 0.4 69.9 ± 0.2 1.7 ± 0.1 0.8 ± 0.1 353.5 ± 0.4 |

4.9 ± 1.2 1.6 ± 0.2 281.6 ± 0.5 69.8 ± 0.4 1.7 ± 0.2 0.8 ± 0.1 353.0 ±1.0 |

8 (1) 46 (6) 100 (13) n/a n/a n/a n/a |

9 (1) 45 (5) 100 (11) n/a n/a n/a n/a |

2.2 µg 1.6 mg 450 mg - - - - |

0.67 0.55 0.15 0.52 0.38 0.33 0.16 |

2.3. Labor and Newborn Characteristics

| Labor | Median (p25-p75) a or % frequency (n) b | |||

| Control (n=6) | Gestational diabetes mellitus (n=5) | p value | ||

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) a | 39.8 (38.6-41.2) | 38.7 (38.4- 39.5) | 0.23 | |

| Delivery mode b Vaginal C-section |

50 (3) 50 (3) |

20 (1) 80 (4) |

0.10 | |

| Newborn | ||||

| Sex b Female Male |

50 (3) 50 (3) |

80(4) 20 (1) |

0.55 | |

| Birth weight (g) a | 3433 (3139-3955) | 3240 (2970-3275) | 0.43 | |

| Birth length (cm) a | 50.3 (48.3-51.0) | 47.5 (45.5-49.5) | 0.24 | |

2.4. Semi-Targeted Metabolomics in Placental Tissue

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Participants

4.2. Ethical Approval

4.3. Assessment of Dietary Data

4.4. Placental Sampling and Tissue Extraction for Metabolomics

4.4.1. Semi-Targeted Mass Spectrometry Metabolomics

4.4.2. 1H-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance-Based Metabolomics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADP – Adenosine diphosphate AMP – Adenosine monophosphate ATP – Adenosine triphosphate 1,3BPG - 1,3 biphosphoglycerate BMI – Body mass index DHF - Dihydrofolate DMG - Dimethylglycine DNA – Deoxyribonucleic acid DOHaD – Developmental origins of Health and Disease ER – Endoplasmic reticulum F1,6P - Fructose 1,6 biphosphate G1P – Glucose-1-phosphate G6P – Glucose-6-phosphate GDM – Gestational diabetes mellitus GOT - glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase GSH – Glutathione IGF2 – Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 IOM – Institute of Medicine LPS – lipopolysaccharide MS – Mass spectrometry MS/MS – Tandem mass spectrometry MSM – Multiple source method NAD+ - Oxidised Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide NADH – Reduced Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide NMR – Nuclear magnetic resonance PPARy – Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma 2PG+3PG - 2-Phosphoglycerate and 3-Phosphoglycerate 3PS – 3-phosphoserine 3PG - 3-phosphoglyceric acid PEP – phosphoenolpyruvate PEMT – phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase R24h – 24-hour dietary recordings SAH – S-adenosylhomocysteine SAM - S-adenosyl methionine SHMT – Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 5,10-meTHF – 5,10 methyltetrahydrofolate 10-formylTHF – 10 formyl tetrahydrofolate THF - Tetrahydrofolate UDP-glucose – Uridine diphosphate glucose |

References

- Parrettini, S.; Caroli, A.; Torlone, E. Nutrition and Metabolic Adaptations in Physiological and Complicated Pregnancy: Focus on Obesity and Gestational Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, M.J.; Parra, H.; Santeliz, R.; Bautista, J.; Luzardo, E.; Villasmil, N.; Martínez, M.S.; Chacín, M.; Cano, C.; Checa-Ros, A.; D’Marco, L.; Bermúdez, V.; De Sanctis, J.B. The Placental Role in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Molecular Perspective. touchREVIEWS in Endocrinology 2024, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, H.D.; Catalano, P.; Zhang, C.; Desoye, G.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Damm, P. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valent, A.M.; Choi, H.; Kolahi, K.S.; Thornburg, K.L. Hyperglycemia and Gestational Diabetes Suppress Placental Glycolysis and Mitochondrial Function and Alter Lipid Processing. FASEB Journal. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lizárraga, D.; García-Gasca, A. The Placenta as a Target of Epigenetic Alterations in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Potential Implications for the Offspring. Epigenomes 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, N. TGF β 1, SNAIL2, and PAPP-A Expression in Placenta of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Patients. J Diabetes Res 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Wang, T.; Xu, W.; Zhang, S.-H. Epigenetic Modifications of Placenta in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Their Offspring. World J Diabetes 2024, 15, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLOBAL REPORT ON DIABETES WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. ISBN 978, 92–94.

- Giannakou, K.; Evangelou, E.; Yiallouros, P.; Christophi, C.A.; Middleton, N.; Papatheodorou, E.; Papatheodorou, S.I. Risk Factors for Gestational Diabetes: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.P.; Lin, S.; Xie, B.Y.; Zhao, H.F. Recent Progress in Metabolic Reprogramming in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo, R.; Ortega-Camarillo, C.; Ferreira-Hermosillo, A.; Díaz-Velázquez, M.F.; Meixueiro-Calderón, C.; Valencia-Ortega, J. Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgutka, K.; Tkacz, M.; Tomasiak, P.; Piotrowska, K.; Ustianowski, P.; Pawlik, A.; Tarnowski, M. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus-Induced Inflammation in the Placenta via IL-1β and Toll-like Receptor Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radaelli, T.; Varastehpour, A.; Catalano, P.; Mouzon, S.H. Gestational Diabetes Induces Placental Genes for Chronic Stress and Inflammatory Pathways GDM ALTERS EXPRESSION PROFILE OF PLACENTAL GENES. Diabetes 2003, 52, 2951–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phoswa, W.N.; Khaliq, O.P. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (Preeclampsia, Gestational Hypertension) and Metabolic Disorder of Pregnancy (Gestational Diabetes Mellitus). Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, H. wa; Alnæs-Katjavivi, P.; Jones, C.J.P.; El-Bacha, T.; Golic, M.; Staff, A.C.; Burton, G.J. Placental Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Gestational Diabetes: The Potential for Therapeutic Intervention with Chemical Chaperones and Antioxidants. Diabetologia 2016. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, G.D.A.; Murgia, A.; Lai, C.; Ferreira, C.S.; Goes, V.A.; De A., B. Guimarães, D.; Ranquine, L.G.; Reis, D.L.; Struchiner, C.J.; Griffin, J.L.; Burton, G.J.; Torres, A.G.; El-Bacha, T. Sphingolipids and Acylcarnitines Are Altered in Placentas from Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Br J Nutr 2023, 130, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.; Pinto, G.D.A.; Reis, D.L.; Vigor, C.; Goes, V.A.; Guimarães, D. de A. B.; Mucci, D.B.; Belcastro, L.; Saraiva, M.A.; Oger, C.; Galano, J.M.; Sardinha, F.L.C.; Torres, A.G.; Durand, T.; Burton, G.J.; El-Bacha, T. Placental F4-Neuroprostanes and F2-Isoprostanes Are Altered in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Maternal Obesity. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2023, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Quan, S.; Yang, G.; Ye, Q.; Chen, M.; Yu, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Qiao, S. One Carbon Metabolism and Mammalian Pregnancy Outcomes. Mol Nutr Food Res 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nema, J.; Joshi, N.; Sundrani, D.; Joshi, S. Influence of Maternal One Carbon Metabolites on Placental Programming and Long Term Health. Placenta 2022, 125, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, K.M.; Williams, B.A.; Elango, R.; Barr, S.I.; Karakochuk, C.D. Pregnancy-Induced Alterations of 1-Carbon Metabolism and Significance for Maternal Nutrition Requirements. Nutr Rev 2022, 80, 1985–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.X.; Shu, Y.P.; Yang, X.Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, N.N.; Zhao, M. Effects of Folic Acid Supplementation in Pregnant Mice on Glucose Metabolism Disorders in Male Offspring Induced by Lipopolysaccharide Exposure during Pregnancy. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintaka, Y.; Wada, N.; Shioda, S.; Nakamura, S.; Yamazaki, Y.; Mochizuki, K. Excessive Folic Acid Supplementation in Pregnant Mice Impairs Insulin Secretion and Induces the Expression of Genes Associated with Fatty Liver in Their Offspring. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.M.; Arthurs, A.L.; Smith, M.D.; Roberts, C.T.; Jankovic-Karasoulos, T. High Folate, Perturbed One-Carbon Metabolism and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, J.; Greenwald, E.; Jack-Roberts, C.; Ajeeb, T.T.; Malysheva, O.V.; Caudill, M.A.; Axen, K.; Saxena, A.; Semernina, E.; Nanobashvili, K.; Jiang, X. Choline Prevents Fetal Overgrowth and Normalizes Placental Fatty Acid and Glucose Metabolism in a Mouse Model of Maternal Obesity. J Nutr Biochem 2017, 49, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.H.; Kwan, S.T.C.; Yan, J.; Klatt, K.C.; Jiang, X.; Roberson, M.S.; Caudill, M.A. Maternal Choline Supplementation Alters Fetal Growth Patterns in a Mouse Model of Placental Insufficiency. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.H.; Kwan, S.T.C.; Yan, J.; Jiang, X.; Fomin, V.G.; Levine, S.P.; Wei, E.; Roberson, M.S.; Caudill, M.A. Maternal Choline Supplementation Modulates Placental Markers of Inflammation, Angiogenesis, and Apoptosis in a Mouse Model of Placental Insufficiency. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adaikalakoteswari, A.; Wood, C.; Mina, T.H.; Webster, C.; Goljan, I.; Weldeselassie, Y.; Reynolds, R.M.; Saravanan, P. Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Altered One-Carbon Metabolites in Early Pregnancy Is Associated with Maternal Obesity and Dyslipidaemia. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, Y. Relationship between One-Carbon Metabolism and Fetal Growth in Twins: A Cohort Study. Food Sci Nutr 2023, 11, 6626–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.F.; Wei, Y.; Yang, J.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Zuo, X.F.; Wu, T.C.; Shi, H.F.; Wang, X.L. Maternal Betaine Status, but Not That of Choline or Methionine, Is Inversely Associated with Infant Birth Weight. Br J Nutr 2019, 121, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, I.; Dalloul, M.; Hausser, J.; Vaday, D.; Gilboa, E.; Wang, L.; Hittelman, J.; Hoepner, L.; Fordjour, L.; Chitamanni, P.; Saxena, A.; Jiang, X. Role of One-Carbon Nutrient Intake and Diabetes during Pregnancy in Children’s Growth and Neurodevelopment: A 2-Year Follow-up Study of a Prospective Cohort. Clin Nutr 2024, 43, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, I.; Dalloul, M.; Hausser, J.; Huntley, M.; Hoepner, L.; Fordjour, L.; Hittelman, J.; Saxena, A.; Liu, J.; Futterman, I.D.; Minkoff, H.; Jiang, X. Associations between Nutrients in One-Carbon Metabolism and Fetal DNA Methylation in Pregnancies with or without Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Clin Epigenetics 2023, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilay, E.; Moon, A.; Plumptre, L.; Masih, S.P.; Sohn, K.J.; Visentin, C.E.; Ly, A.; Malysheva, O.; Croxford, R.; Caudill, M.A.; O’Connor, D.L.; Kim, Y.I.; Berger, H. Fetal One-Carbon Nutrient Concentrations May Be Affected by Gestational Diabetes. Nutr Res 2018, 55, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tests, D.; Diabetes, F.O.R. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kac, G.; Carrilho, T.R.B.; Rasmussen, K.M.; Reichenheim, M.E.; Farias, D.R.; Hutcheon, J.A. Gestational Weight Gain Charts: Results from the Brazilian Maternal and Child Nutrition Consortium. Am J Clin Nutr 2021, 113, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicine, I. of. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) 2002, 1–1331. [CrossRef]

- Harttig, U.; Haubrock, J.; Knüppel, S.; Boeing, H. The MSM Program: Web-Based Statistics Package for Estimating Usual Dietary Intake Using the Multiple Source Method. Eur J Clin Nutr 2011, 65 (Suppl. 1), S87–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicine, I. of Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Villar, J.; Ismail, L.C.; Victora, C.G.; Ohuma, E.O.; Bertino, E.; Altman, D.G.; Lambert, A.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Carvalho, M.; Jaffer, Y.A.; et al. International Standards for Newborn Weight, Length, and Head Circumference by Gestational Age and Sex: The Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet 2014, 384, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, X.; He, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Chen, W. Maternal Age and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of over 120 Million Participants. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheiffer, C.; Riedel, S.; Dias, S.; Adam, S. Gestational Diabetes and the Gut Microbiota: Fibre and Polyphenol Supplementation as a Therapeutic Strategy. Microorganisms 2024, Vol. 12, Page 633 2024, 12, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, J.D. Pathways and Regulation of Homocysteine Metabolism in Mammals. Semin Thromb Hemost 2000, 26, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S.H. Choline: Critical Role during Fetal Development and Dietary Requirements in Adults. Annu Rev Nutr 2006, 26, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.M.; Carmichael, S.L.; Yang, W.; Selvin, S.; Schaffer, D.M. Periconceptional Dietary Intake of Choline and Betaine and Neural Tube Defects in Offspring. Am J Epidemiol 2004, 160, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Vance, D.E. Phosphatidylcholine and Choline Homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, R.; Schön, C.; Derbyshire, E.; Jiang, X.; Mellott, T.J.; Blusztajn, J.K.; Zeisel, S.H. A Narrative Review on Maternal Choline Intake and Liver Function of the Fetus and the Infant; Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice. Nutrients 2024, 16, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lee, L.; Crozier, S.R.; Aris, I.M.; Tint, M.T.; Sadananthan, S.A.; Michael, N.; Quah, P.L.; Robinson, S.M.; Inskip, H.M.; Harvey, N.C.; et al. Prospective Associations of Maternal Choline Status with Offspring Body Composition in the First 5 Years of Life in Two Large Mother-Offspring Cohorts: The Southampton Women’s Survey Cohort and the Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes Cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2019, 48, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Bar, H.Y.; Yan, J.; Jones, S.; Brannon, P.M.; West, A.A.; Perry, C.A.; Ganti, A.; Pressman, E.; Devapatla, S.; Vermeylen, F.; Wells, M.T.; Caudill, M.A. A Higher Maternal Choline Intake among Third-Trimester Pregnant Women Lowers Placental and Circulating Concentrations of the Antiangiogenic Factor Fms-like Tyrosine Kinase-1 (SFLT1). FASEB J 2013, 27, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jones, S.; Andrew, B.Y.; Ganti, A.; Malysheva, O.V.; Giallourou, N.; Brannon, P.M.; Roberson, M.S.; Caudill, M.A. Choline Inadequacy Impairs Trophoblast Function and Vascularization in Cultured Human Placental Trophoblasts. J Cell Physiol 2014, 229, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.H.; Kwan, S.T.C.; Yan, J.; Jiang, X.; Fomin, V.G.; Levine, S.P.; Wei, E.; Roberson, M.S.; Caudill, M.A. Maternal Choline Supplementation Modulates Placental Markers of Inflammation, Angiogenesis, and Apoptosis in a Mouse Model of Placental Insufficiency. Nutrients 2019, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, S.T. (Cecilia); King, J. H.; Yan, J.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Hutzler, J.S.; Klein, H.R.; Brenna, J.T.; Roberson, M.S.; Caudill, M.A. Maternal Choline Supplementation Modulates Placental Nutrient Transport and Metabolism in Late Gestation of Mouse Pregnancy. J Nutr 2017, 147, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, M.A. Pre- and Postnatal Health: Evidence of Increased Choline Needs. J Am Diet Assoc 2010, 110, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, A.M.; Mills, J.L.; Cox, C.; Daly, S.F.; Conley, M.; Brody, L.C.; Kirke, P.N.; Scott, J.M.; Ueland, P.M. Choline and Homocysteine Interrelations in Umbilical Cord and Maternal Plasma at Delivery. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 82, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.P.M.S.; Da Costa Gayotto, L.C.; Tatai, C.; Della Bina, B.I.; Janiszewski, M.; Lima, E.S.; Abdalla, D.S.P.; Lopasso, F.P.; Laurindo, F.R.M.; Laudanna, A.A. Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, in Rats Fed with a Choline-Deficient Diet. J Cell Mol Med 2002, 6, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, B.F.; Ennis, M.A.; Dyer, R.A.; Lim, K.; Elango, R. Glycine, a Dispensable Amino Acid, Is Conditionally Indispensable in Late Stages of Human Pregnancy. J Nutr 2020, 151, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetin, I.; Marconi, A.M.; Baggiani, A.M.; Buscaglia, M.; Pardi, G.; Fennessey, P.V.; Battaglia, F.C. In Vivo Placental Transport of Glycine and Leucine in Human Pregnancies. Pediatric Research 1995, 37, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.M.; Godfrey, K.M.; Jackson, A.A.; Cameron, I.T.; Hanson, M.A. Low Serine Hydroxymethyltransferase Activity in the Human Placenta Has Important Implications for Fetal Glycine Supply. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005, 90, 1594–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, M.B.; Bastani, N.E.; Holme, A.M.; Zucknick, M.; Jansson, T.; Refsum, H.; Mørkrid, L.; Blomhoff, R.; Henriksen, T.; Michelsen, T.M. Uptake and Release of Amino Acids in the Fetal-Placental Unit in Human Pregnancies. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ning, J.; Huai, J.; Yang, H. Hyperglycemia in Pregnancy-Associated Oxidative Stress Augments Altered Placental Glucose Transporter 1 Trafficking via AMPKα/P38MAPK Signaling Cascade. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralimanoharan, S.; Maloyan, A.; Myatt, L. Mitochondrial Function and Glucose Metabolism in the Placenta with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Role of MiR-143. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016, 130, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.R.; Su, G.D.; Chi, Y.L.; Wu, T.; Xu, Y.; Chen, C.C. Dysregulated MiRNAs Contribute to Altered Placental Glucose Metabolism in Patients with Gestational Diabetes via Targeting GLUT1 and HK2. Placenta 2021, 105, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauguel, S.; Desmaizieres, V.; Challier, J.C. Glucose Uptake, Utilization, and Transfer by the Human Placenta as Functions of Maternal Glucose Concentration. Pediatr Res 1986, 20, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatley, E.G.; Truong, T.T.; Wilhelm, D.; Harvey, A.J.; Gardner, D.K. β-Hydroxybutyrate Reduces Blastocyst Viability via Trophectoderm-Mediated Metabolic Aberrations in Mice. Hum Reprod 2022, 37, 1994–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunster, S.J.; Watson, E.D.; Fowden, A.L.; Burton, G.J. REPRODUCTION REVIEW Placental Glycogen Stores and Fetal Growth: Insights from Genetic Mouse Models. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kadam, L.; Veličković, M.; Stratton, K.; Nicora, C.D.; Kyle, J.E.; Wang, E.; Monroe, M.E.; Bramer, L.M.; Myatt, L.; Burnum-Johnson, K.E. Sexual Dimorphism in Lipidomic Changes in Maternal Blood and Placenta Associated with Obesity and Gestational Diabetes: A Discovery Study. Placenta 2025, 159, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.K.; Soultanakis, R.P.; Matthews, D.E. Literacy and Body Fatness Are Associated with Underreporting of Energy Intake in US Low-Income Women Using the Multiple-Pass 24-Hour Recall: A Doubly Labeled Water Study. J Am Diet Assoc 1998, 98, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, K.; Johnson, R.K.; Soultanakis, R.P.; Matthews, D.E. In-Person vs Telephone-Administered Multiple-Pass 24-Hour Recalls in Women: Validation with Doubly Labeled Water. J Am Diet Assoc 2000, 100, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorelli, D.S.; Crivellenti, L.C.; Manochio-Pina, M.G.; Baroni, N.F.; Carvalho, M.R.; Diez-Garcia, R.W.; Franco, L.J. Study Protocol Effectiveness of a Nutritional Intervention Based on Encouraging the Consumption of Unprocessed and Minimally Processed Foods and the Practice of Physical Activities for Appropriate Weight Gain in Overweight, Adult, Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA Food Classification and the Trouble with Ultra-Processing. Public Health Nutr 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Sebire, N.J.; Myatt, L.; Tannetta, D.; Wang, Y.L.; Sadovsky, Y.; Staff, A.C.; Redman, C.W. Optimising Sample Collection for Placental Research. Placenta 2014, 35, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcisi, S.; Moritz, F.; Kanawati, B.; Tziotis, D.; Lehmann, R.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry in Metabolomics Research: Mass Analyzers in Ultra High Pressure Liquid Chromatography Coupling. J Chromatogr A 2013, 1292, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.L.; Shaka, A.J. Water Suppression That Works. Excitation Sculpting Using Arbitrary Wave-Forms and Pulsed-Field Gradients. J Magn Reson A 1995, 112, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, H.Y.; Purcell, E.M. Effects of Diffusion on Free Precession in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Experiments. Physical Review 1954, 94, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, C.; Günther, U.L. MetaboLab--Advanced NMR Data Processing and Analysis for Metabolomics. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart DS, Guo A, Oler E, Wang F, Anjum A, Peters H et al. HMDB 5.0: the Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D622–D631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).