1. Introduction

The nematocidal properties of

Pleurotus ostreatus against phytopathogenic nematodes have been tested in various experiments since its discovery by G. Barron [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Nematodes infect many vegetable crops as well as major agricultural crops, such as sugar beet. One of the most serious problems in sugar beet cultivation is

Heterodera schachtii, a cyst nematode that significantly reduces root yield and sugar content [

3,

6]. Its control is difficult, and chemical treatments pose environmental risks; therefore, in many countries, including Poland, no chemical substances are officially registered for nematode control in sugar beet crops. Consequently, non-chemical strategies for managing phytopathogenic nematodes are highly desirable [

6]. Currently, biological methods such as crop rotation and the use of tolerant cultivars are the most common approaches to

H. schachtii control. Another possibility is the use of nematocidal plants, which prevent the pest from completing its life cycle [

6]. Among these are oilseed radish (

Raphanus sativus var.

oleiformis) and white mustard (

Sinapis alba), although not all varieties exhibit nematocidal properties. Such trapping crops should be used as part of integrated plant protection strategies, together with crop rotation and tolerant varieties [

6]. Their activity against

H. schachtii is mainly related to chemical signals released into the soil through roots exudates, although their effects depend on the nematode density and environmental conditions. The impact on cyst nematode population density is primarily due to on the stimulation of hatching by root exudates and the penetration of plant roots by the nematodes, which ultimately prevents them from completing their life cycle [

7,

8]. Reduction of nematode populations in soil can also be achieved by incorporating various dried and powdered plant leaves or mushroom stems. For example, rubber plant leaves, orange peels, and oyster mushroom stems have been shown to reduce

H. goldeni populations by at least 80% [

9]. However, the effectiveness of trap crops, such as radish varieties, may be lower than other biological or chemical control methods, they offer notable environmental and economic benefits, such as serving as green manure, being harmless to agricultural soil, mitigating soil erosion, and lowering nematode management costs [

7,

8].

Mycelia of

P. ostreatus may differ in their nematocidal activity [

10,

11]. Previous studies have shown that mycelia differ in their growth rate, optimal temperatures for vegetative growth and activity against nematodes [

10,

11]. When introduced into the field,

P. ostreatus mycelia are influenced by multiple environmental factors, including the presence of other plants such as oilseed radish and white mustard. This influence has not been previously studied, and the interactions remain unclear.

This study aimed to examine the effects of the combined application of P. ostreatus mycelium with plant root exudates, as well as the presence of seeds’ secretions, on nematode suppression. The research provides insight into whether plants may influence the effectiveness of P. ostreatus mycelium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organisms

The plant materials used in the experiment included seeds and seedlings of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris), variety Janetka, kindly provided by Kutnowska Hodowla Buraka Cukrowego (Kutnowska Sugar Beet Breeding Company, Poland); oilseed radish (Raphanus sativus L. subsp. oleiformis Pers.) cv. Romesa; and white mustard (Sinapis alba L.) cv. Bardena, both purchased locally. All seeds were surface-sterilized prior to use, either directly in the experiments or before seedling production. Root exudates were obtained by immersing the roots of well-developed seedlings (10 plants per sample) in sterile deionized water (5 mL) for 24 h.

The Pleurotus ostreatus mycelial strains used in the experiments included: Po1-5dix27, Po2-15dix17, Po4-2dix1, Po4-14x17, Po4-3dix17, Po2-20dix23, Po4-8, Po4-30, R01, and R08. These strains represented laboratory-generated crossed strains (heterokaryons) (e.g., Po4-14x17), monokaryons (homokaryons) derived from basidiospores (Po4-8, Po4-30), and heterokaryons produced according to Buller’s rules (Po1-5dix27, Po2-15dix17, Po4-2dix1, Po4-3dix17, Po2-20dix23). Strains R01 and R08, commonly used in commercial oyster mushroom cultivation, served as reference controls. All strains were selected based on previous assessments of their direct nematocidal activity [8, 9, and partially unpublished data]. Prior to use in the laboratory pot experiment, the mycelia were pre-cultured on PDA medium.

Cysts of

Heterodera schachtii were isolated from naturally infested soil following the methodology described by Kaczorowski [

12]. Prior to the main procedure, soil samples (100 ± 0.1 g) were air-dried at room temperature and sieved through a 2-mm mesh to remove straw residues. Cysts were then extracted using a Seinhorst apparatus, which employs a water–soil suspension and separates organic and inorganic fractions based on their density and flotation properties. Extraction was carried out at an ambient temperature of 20 °C for 8 minutes, with a flow rate of 1.6 dm³/min.

Cysts recovered from this process were further separated from smaller organic particles using a dissecting needle under a stereomicroscope (ProLab Scientific Motic SMZ160). The isolated cysts were collected and stored in Petri dishes under refrigeration until use in the experiments.

Nematode

Caenorhabditis elegans N2 were used as a model culture and it was obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) and propagated according to the methodology provided by Stiernagle [

13].

2.2. Experiment Methodology

The experiments were conducted on an agar medium (water agar, WA) in Petri dishes previously inoculated with P. ostreatus mycelium. The mycelium was incubated for two weeks until it fully colonized the WA surface. Subsequently, either (1) seeds of white mustard, oilseed radish, or sugar beet were placed on the medium, or (2) root exudates obtained from seedlings of the same plant species were applied. In each experimental treatment, C. elegans nematodes or H. schachtii cysts (3 per point) were introduced at the point of seed placement or exudate application. Control dishes contained no seeds or exudates.

The aim of the study was to determine whether plant-derived materials (seed secretions or root exudates) influence potential changes in the activity of the mycelium against the tested nematodes. Parameters assessed included the degree of

C. elegans immobilization, the extent of

H. schachtii cyst overgrowth, and the ability of the mycelium to produce toxin-forming structures (toxocysts). Evaluations were performed according to previously established rating scales [

10,

11] ranging from 0 to 3, where a score of 3 indicated the highest level of nematode movement. The desired outcome—complete inhibition of movement, nematode death, and overgrowth of nematode bodies by mycelium—corresponded to a score of 0. For toxocyst formation, the highest score was 3.

Observations were conducted at 1, 3, 5, 24, and 48 hours after inoculation, and additionally after 5 days in the H. schachtii treatments. Results are presented only for the most informative observation points. Each experimental variant was performed in triplicate, using the following scales for H. schachtii assessments:

Cysts of Heterodera schachtii overgrowing:

0 - no hyphal reaction to the presence of the cyst;

1 - mycelial hyphae directed towards the cyst;

2 - fine hyphae entwining the cyst;

3 - cyst entwined by growing hyphae (Supplementary materials: Picture 1).

Toxocysts production:

0 - no toxocysts developed;

1 - few toxocysts;

2 - average number of toxocysts;

3 - abundant toxocysts (Supplementary materials: Picture 2).

Result were presented in graphs as averages for all assessments. Data were collected in 2023-24.

2.3. Calculations and Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. Mean values and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated at a 95% confidence level, and results were expressed as mean ± SD and presented in graphs. Statistical analyses were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in Statistica software v.13.3 package. Data were compared (p=0.05) using Duncan's test. Correlation coefficients were calculated, using Microsoft Excel, between toxocysts formation and movement of C. elegans.

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Plants and Caenorhabditis elegans on the Mycelia Activity

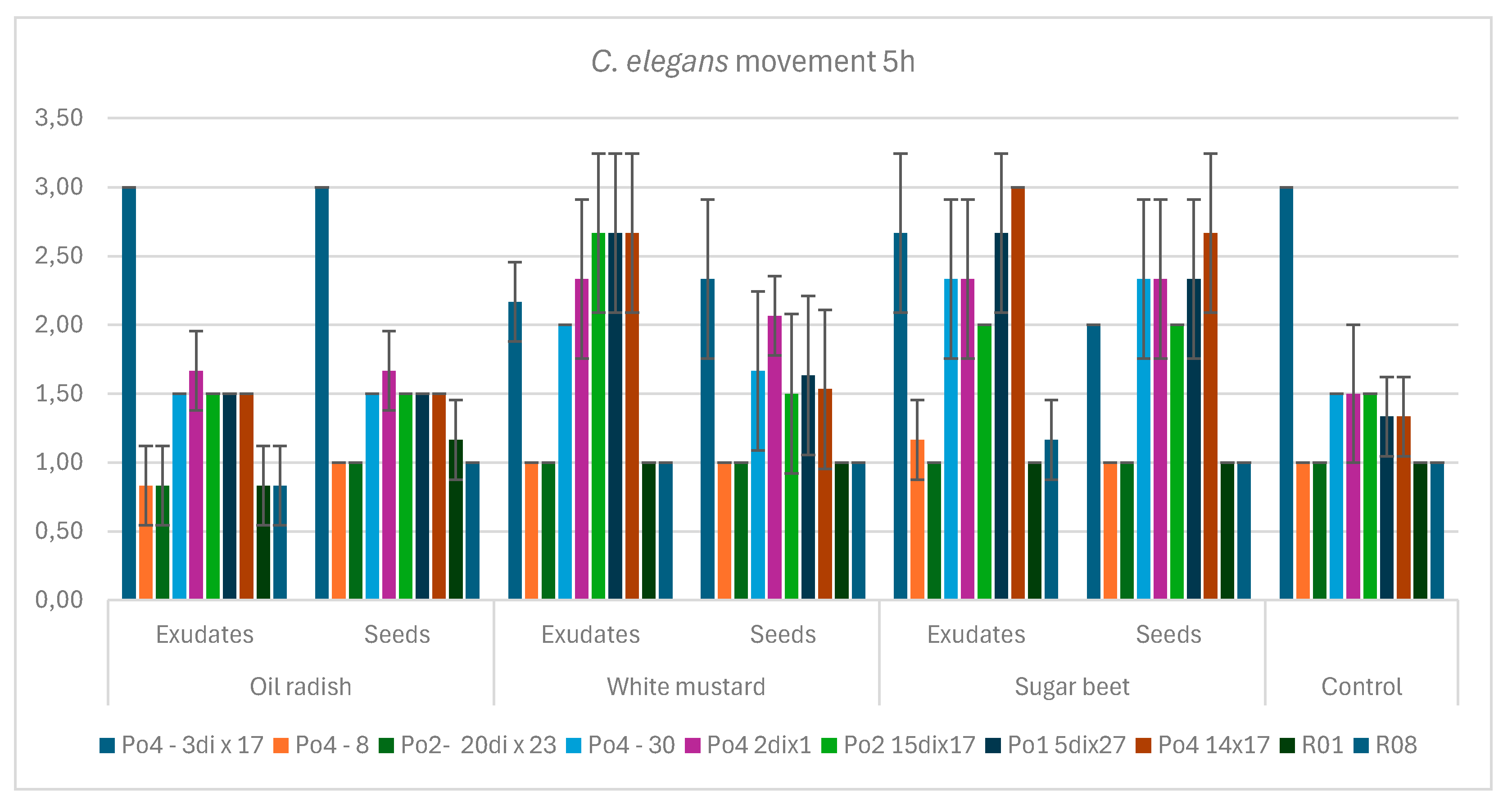

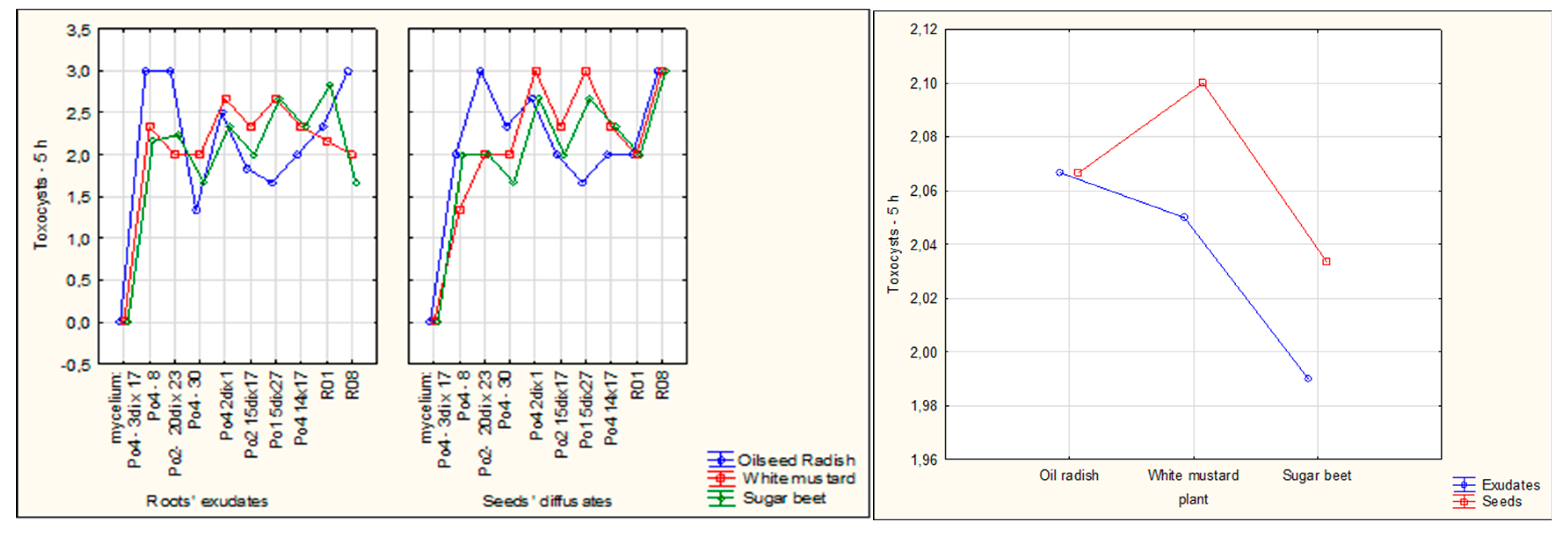

Tested mycelia presented variable activity against

C. elegans nematodes. The activity was measured by the assessment of nematodes movement. The statistical analyses indicated no statistics significance in obtained results, however the clear trends were visible. The correlation coefficient between observed movement after 5 hours of the experiment and the average assessment for movement in the period 1 to 48 hours was 0.89, indicating that the assessment in the 5

th hour of the experiment gives enough information concerning the mycelium activity. When the toxocysts formation abilities were compared with the

C. elegans mobility, the correlation coefficient between these two parameters was achieved as presented in

Table 1. These coefficients achieved negative values (-0.44 to -0.49), which means that when the production of toxocysts increases, the movement of nematodes is slowed. This correlations are weak, however, they present trends observed in mycelia of

P. ostreatus activity against nematodes.

Two tested mycelia generated in our laboratory (Po4-8 and Po2-20dix23) and the control mycelia R01, and R08 were able to efficiently slow down the nematode mobility after 5 hours of contact, and their toxocysts productions reached high scores [

Table 2,

Figure 1,

Figure 2, Figure 7a]. The remaining mycelial strains did not differ significantly across the entire experiment with respect to either parameter: reduction of nematode mobility or toxocyst formation. However, one example of mycelium, Po4-3di x 17, was not able to slow down nematodes, did not produce toxocysts, and siggnificantly dffered in this parameters from other tested mycelia [

Table 2,

Figure 1,

Figure 2, Figure 7a]. Oilseed radish—both its root exudates and seeds’ diffusates—exerted the most favorable influence on mycelial activity, resulting in the greatest reduction in nematode movement [

Figure 1, Figure 5, Figure 6c]. The effects of white mustard, whether in the form of exudates or seeds, varied among the different mycelial strains. However, across the experiment as a whole, the use of seeds generally produced better outcomes than the application of exudates [

Figure 1,

Figure 2, Figure 5, Figure 6b].

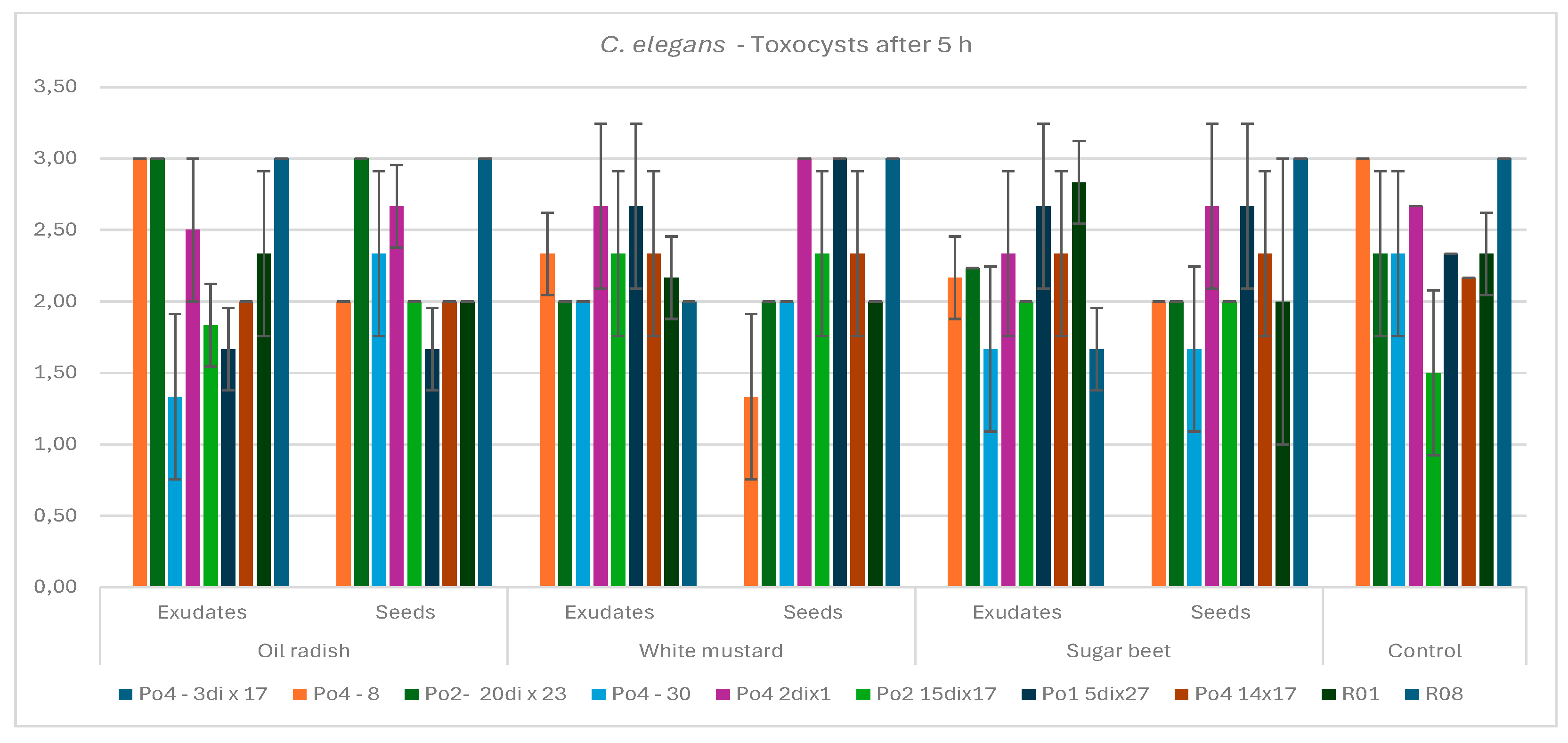

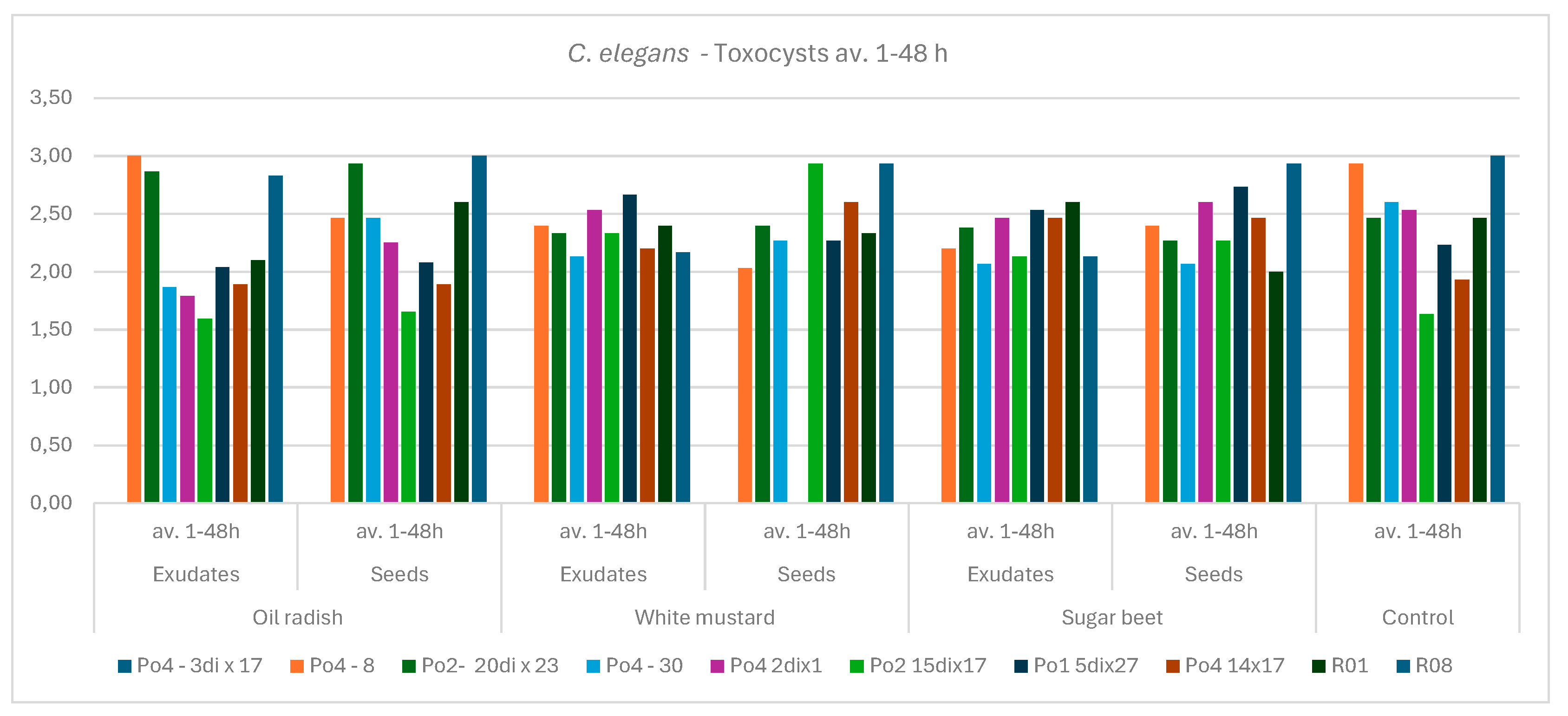

Although toxocyst production was negatively correlated with nematode mobility, no significant differences were observed among most of the tested mycelial strains. However, strain R08 produced significantly more toxocysts than strains Po2-15di x17 and Po4-3di x17, the latter of which was unable to form toxocysts [

Table 2;

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 6a]. The most favorable trends for toxoxcyst producction were observed under the influence of seeds’ diffusates of white mustard, followed by both variants of oilseed radish [

Figure 7a,b].

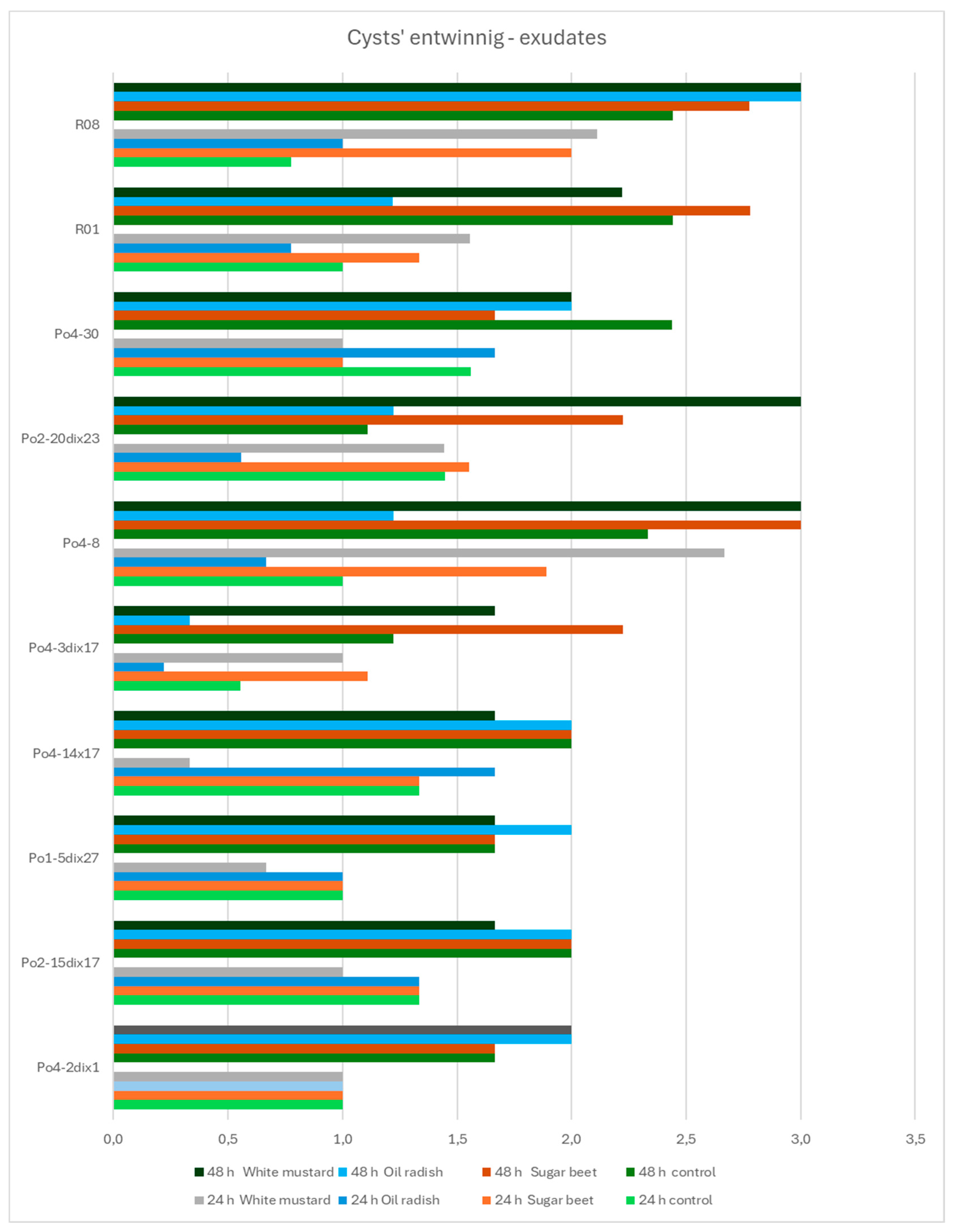

3.2. Influence of Plants and Heterodera schachtii Cysts on the Mycelia Activity

Heterodera schachtii is a nematode that can be parasitized by

P. ostreatus mycelium through the overgrowth of its cysts. After five days of co-incubation of cysts with mycelia and plant materials, all mycelial strains overgrew the cysts, receiving the maximum score on the evaluation scale in nearly all cases. The only exception was strain Po4-3di x17, which achieved a score of 2.67 in the presence of oilseed radish or white mustard seeds. No significant differences were observed among the mycelial strains or plant materials in this regard. In this experiment, strain Po4-3di x17 was the least active, overgrowing cysts more slowly when exposed to oilseed radish exudates (

Figure 8) or to oilseed radish and white mustard seeds (

Figure 8). The most pronounced effects were observed for strain Po4-8, which showed strong activity after 24 hours in the presence of white mustard exudates, and after 48 hours when exposed to exudates of sugar beet or white mustard (

Figure 8).

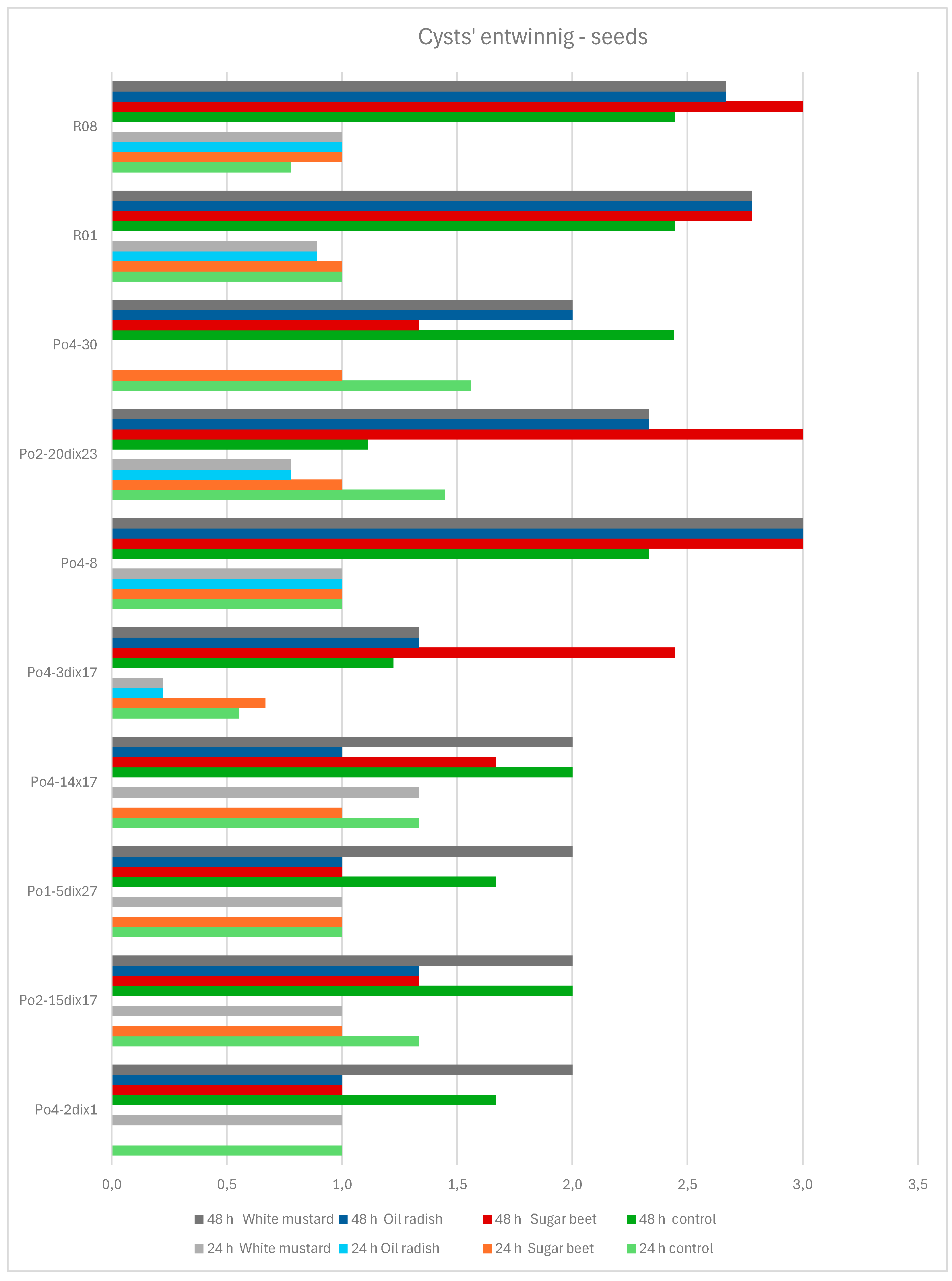

The effects of seeds on mycelial activity varied. No visible overgrowth was recorded after 24 hours for strains Po4-2dix1, Po2-15dix17, Po1-5dix27, Po4-14x17, and Po4-30 when exposed to oilseed radish seeds, and for strains Po4-30 and Po4-2dix1 when exposed to white mustard and sugar beet seeds, respectively. After 48 hours, strain Po4-8 showed consistent overgrowth in the presence of all three seed types, a pattern similarly observed for strains R08 and R01 (

Figure 9).

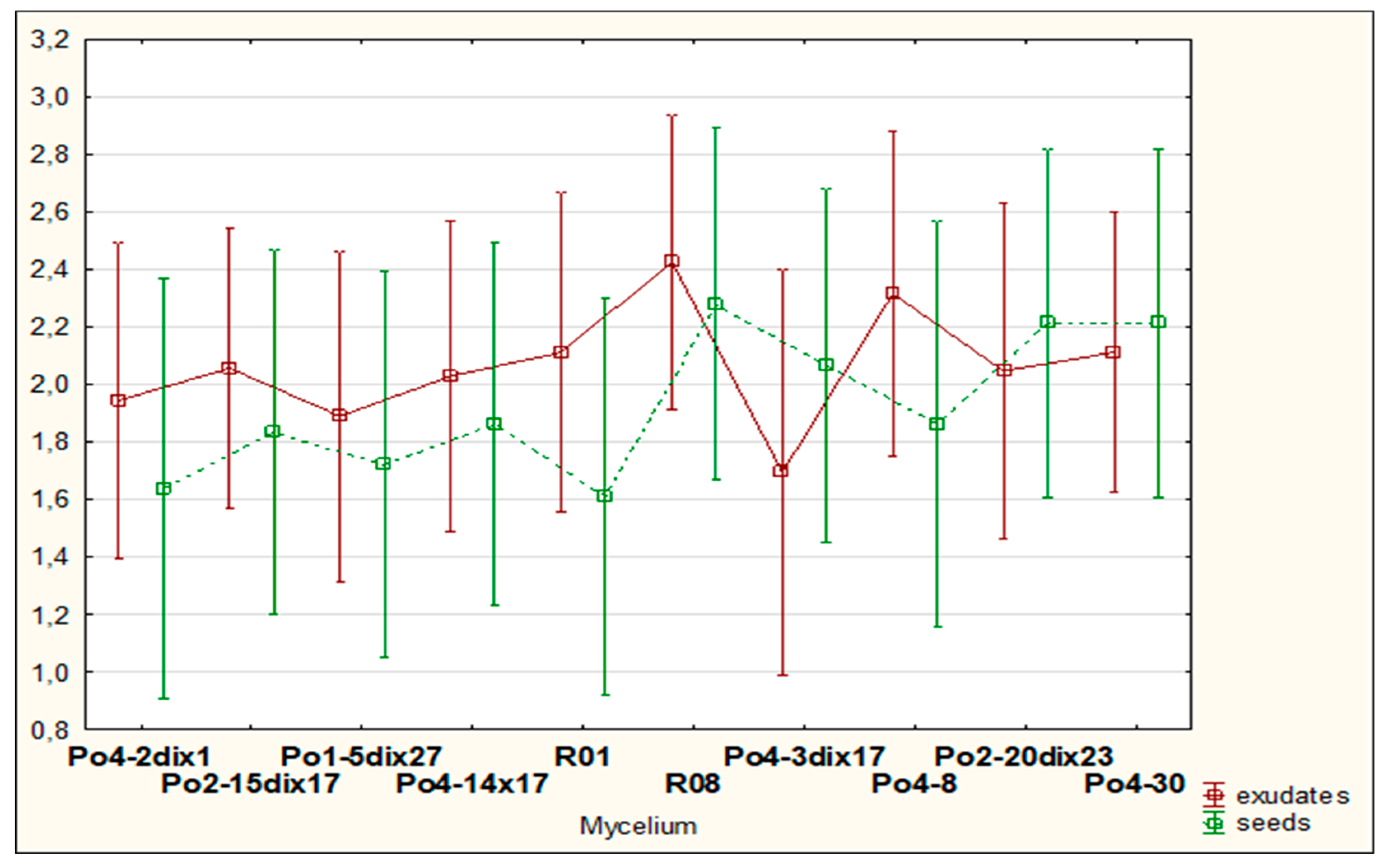

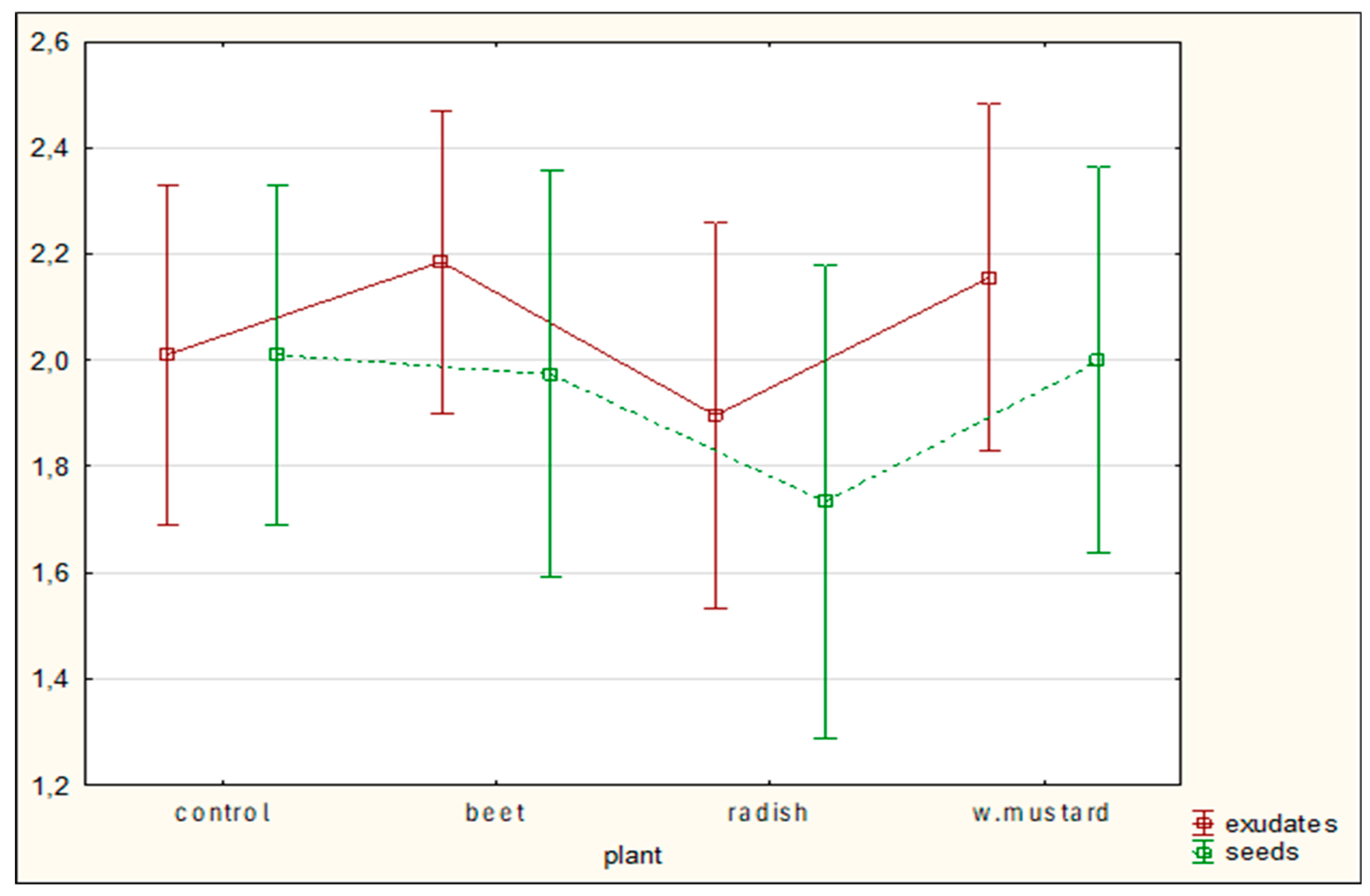

The results obtained did not differ significantly with respect to the mycelial strains or the tested plant materials; however, sugar beet and white mustard, whether as exudates or seeds, tended to enhance mycelial activity (Figures 10,11). Overall, cyst entwining was similarly effective across all mycelial strains, with R08 showing slightly better performance (

Figure 10). In contrast, cyst entwining under the influence of oilseed radish was less effective than with other plant materials (

Figure 11). Furthermore, entwining was generally more pronounced in the presence of exudates than seeds (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

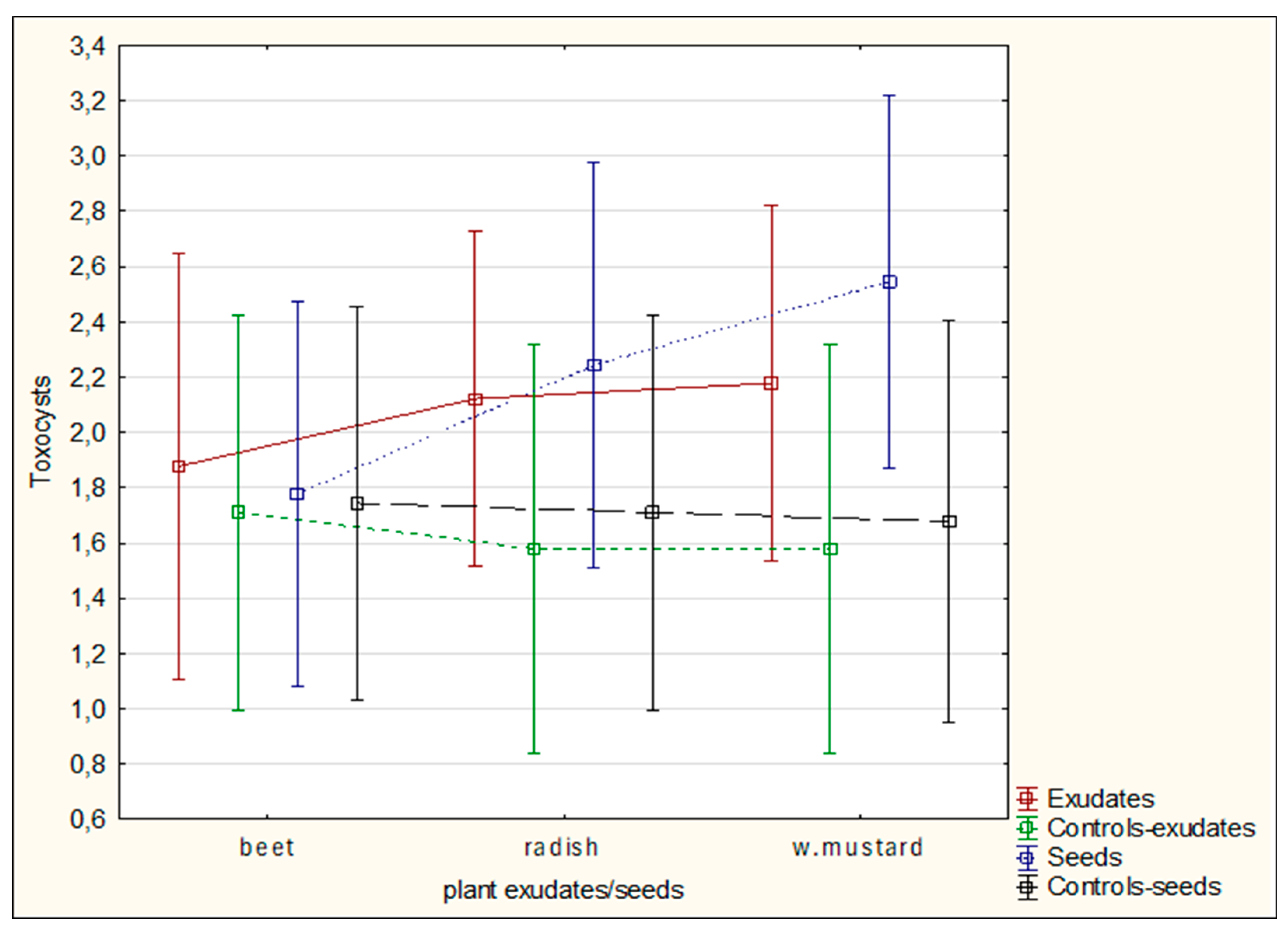

Analysis indicated that the duration of exposure to plant materials (exudates or seeds) significantly affected outcomes, with notable differences observed after 24 hours of incubation (Figure 14). These observations are further supported by the data presented in Figure 15, which shows that the highest levels of toxocysts production were achieved by mycelial strains Po4-8, R01, and R08. Conversely, strain Po4-3di x17 exhibited the weakest ability to entwine

H. schachtii cysts and forming toxocysts (

Figure 10,

Figure 13). Toxocyst formation, during

H. schachtii cysts were entwined by mycelium, was enhanced in the presence of radish or white mustard exudates or seeds (

Figure 14).

4. Discussion

Mycelia of Pleurotus ostreatus demonstrated the ability to kill the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and to entwine and overgrow the cysts of the sugar beet cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii. However, when the mycelia developed in the presence of seed secretions and root exudates, their efficacy did not change significantly. These findings suggest that root exudates of potential trap plants do not negatively affect mycelial activity.

Nevertheless, the present experiments do not isolate or clarify the direct influence of the plants themselves and mycelia on the hatching of H. schachtii eggs, and to our knowledge, such studies have not yet been performed. Therefore, further field experiments are needed that involve the simultaneous introduction of effective mycelium and trap plants into the soil. Additional trap plant species and varieties should also be tested.

A tendency toward reduced mycelial activity was observed in the presence of oilseed radish. The research showed that toxicocyst production is not strongly correlated with the ability of the mycelia to inhibit the movement of

C. elegans. Although these correlations (

Table 1) are weak, they nevertheless reflect general trends in the activity of

P. ostreatus mycelia against nematodes. This observation confirms the established mode of toxic action of vegetative mycelium on nematodes, while at the same time suggesting that additional mechanisms contribute to the nematocidal activity of this mushroom [

14,

15]. The results clearly indicate that the mycelium’s nematocidal activity does not rely solely on toxicocyst production. For example, the mycelial line incapable of producing toxicocysts, Po4-3dix17, still demonstrated the ability to entwine

H. schachtii cysts. The most active strains, Po4-8 and R08, reached maximum toxicocyst production and inhibition of

C. elegans within only 5 hours, which may indicate their overall effectiveness against

C. elegans. For these strains, activity was not influenced by the plant species used, whereas slight plant-dependent effects could be observed in other mycelia.

Among the tested plants, oilseed radish most strongly promoted nematocidal activity against

C. elegans, suggesting that its use as a forecrop or catch crop may be particularly effective in crop rotations aimed at reducing

H. schachtii populations. This finding further indicates that trap plants are unlikely to interfere with mycelial activity in soil environments when both would be applied simultaneously to control the sugar beet cyst nematode. Oilseed radish and leaf radish belong to a group of trap plants known to exhibit strong activity against

H. schachtii, although the final level of cyst depletion depends heavily on cultivar-specific traits. Varieties of white mustard exhibit similar properties [

6,

7,

16].

Hauer et al. [

6] recommend cultivating nematode-resistant trap crops such as oil radish or mustard together with tolerant or resistant sugar beet varieties as part of integrated management strategies targeting

H. schachtii in infested fields. However, as demonstrated by Reuther et al. [

17], tolerant sugar beet varieties do not reduce nematode populations; instead, population levels may even increase during cultivation, reaching 147% of the initial level in the case of the variety ‘Kleist’. Consequently, the identification of complementary methods that reinforce current integrated strategies is essential for more effective management of

H. schachtii.

In our experiments, we tested only two species/varieties of

H. schachtii–trapping plants. However, up to twelve species may be classified within this group; among them, varieties of radish, white mustard, and rye appear to be the most effective [

18]. These species differ in their capacity to stimulate

H. schachtii hatching and subsequently inhibit its further development. For some species, the reduction in

H. schachtii populations did not differ significantly from the fallow control. Nevertheless, unlike fallow soil, these plants provide the additional benefit of green manure, making them more advantageous overall [

18].

The mycelium of

P. ostreatus, in addition to entwining

H. schachtii cysts, produces the volatile compound 3-octanone [

19]. This compound may prove useful in nematode management. Quintanilla et al. [

18], for example, highlight the biofumigation potential of non-host oilseed radish, which could contribute to integrated pest management strategies targeting

H. schachtii.

Resistant varieties of oilseed radish and white mustard are recommended in Central Europe as standard components of

H. schachtii management strategies. These crops should be sown as catch crops before sugar beet cultivation [

20,

21,

22]. A similar strategy has been implemented in Japan, where

H. schachtii was first detected in Hara Village, Nagano Prefecture, in 2017 [

8,

23]. Sakai et al. [

8] reported effective suppression of nematode populations using two leaf-radish varieties that did not support cyst reproduction, in contrast to the control variety. However, they did not quantify the remaining nematode population.

In Europe, breeding catch crops for resistance to

H. schachtii began more than 30 years ago. Field trials have shown that such crops can reduce

H. schachtii population densities by 20–60%, depending on sowing date, plant density, and crop rotation practices [

20,

21]. As forecrops, oilseed radish and white mustard primarily function as green manure species; however, with careful selection of resistant varieties, they can also contribute to reducing

H. schachtii populations [

20,

21]. Enhancing these catch crops with

P. ostreatus mycelium may further strengthen integrated plant protection strategies.

5. Conclusions

The activity of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium against Heterodera schachtii in the presence of sugar beet root exudates is not reduced compared with its activity in the presence of other plant species or under control conditions. Thus, plants—including sugar beet—do not interfere with the efficacy of the mycelium. Moreover, the use of nematocidal plant species does not diminish the performance of highly active mycelial strains. In the case of strains with lower inherent efficacy, the incorporation of white mustard may even prove more beneficial than other plant species. However, tests on C. elegans suggest that oilseed radish may also be effective.

Overall, these findings suggest that the application of nematocidal plants as green manure is compatible with the potential use of P. ostreatus mycelium as a biological control agent against H. schachtii. To our knowledge, this is the first experiment that integrates the activities of trap plants and sugar beet with the nematocidal effects of P. ostreatus mycelium.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. S1: Picture 1. Cyst entwining assessment scale. Picture 2. The toxocyst production assessment scale.

Author Contributions

E.M.—conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, resources, visualization, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; M.N.— conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, supervision; R.N.— formal analysis, resources, investigation, writing— review & editing; M.No.— conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, supervision; writing— review & editing.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development grant number under the program “Biological Progress in Plant Production”, the project for the years 2021–2026, task 22 “Influence of environmental parameters and biological variability of Pleurotus ostreatus in terms of. nematocidal activity on Heterodera schachtii”.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out at MCBR UO (International Research and Development Center of the University of Opole), which was established as part of a project co-financed by the European Union under the European Regional Development Fund, RPO WO 2014-2020, Action 1.2 Infra-structure for R&D. Agreement No. RPOP.01.02.00-16-0001/17-00 dated January 31, 2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Barron G.L., Thorn R.G. Destruction of nematodes by species of Pleurotus. Can. J. Bot. 1987, 65, 774-778.

- Mwangi, N. G., Stevens, M., D. Wright, A. J., J. Watts, W. D., Edwards, S. G., Hare, M. C., & Back, M. A. Population dynamics of stubby root nematodes (Trichodorus and Paratrichodorus spp.) associated with ‘Docking disorder’ of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.), in field rotations with cover crops in East England. Annals of Applied Biology 2025, 187(2), 177-191. [CrossRef]

- Palizi, P., Goltapeh, E. M., Pourjam, E., Safaie, N. Potential of oyster mushrooms for the biocontrol of sugar beet nematode (Heterodera schachtii). Journal of Plant Protection Research 2009, 49(1), 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Castro L.R.I., Delmastro, S., Curvetto, N.R. Spent oyster mushroom substrate in a mix with organic soil for plant pot cultivation. Micologia Aplicada International 2008, 20(1), 17-26.

- Khan A., Saifullah, M. Iqbal, S. Hussain Organic control of phytonematodes with Pleurotus species, Pakistan Journal of Nematology 2014, 32(2), 155-161.

- Hauer, M., Koch, H.-J., Krüssel, S., Mittler, S., Märländer, B. Integrated control of Heterodera schachtii Schmidt in Central Europe by trap crop cultivation, sugar beet variety choice and nematicide application, Applied Soil Ecology 2016, 99, 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Yosano, S., Kitabayashi, S., Sakai, H. Field trial of trap cropping against the sugar beet cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii (Rhabditida: Heteroderidae) in Japan. Applied Entomology and Zoology 2025, 60(1), 67-71. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H., Tateishi, Y., Kitabayashi, S., Tomita, Y., Nishimoto, J., Yosano, S., Uehara, K., Okada, H. KGM1804, a leaf radish green manure variety resistant to the sugar beet cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii. Nematol. Res. 2024, 54, 47-50. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.K.A., Awd-Allach, S.F.A., Handoo, Z.A. Life cycle and control of the cyst nematode Heterodera goldeni on rice in Egypt, International Journal of Nematology 2014, 24(1), 11-17.

- Kudrys, P., Nabrdalik, M., Hendel, P., Kolasa-Więcek, A., Moliszewska, E. Trait Variation between Two Wild Specimens of Pleurotus ostreatus and Their Progeny in the Context of Usefulness in Nematode Control, Agriculture 2022, 12(11), 1-17. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0472/12/11/1819/pdf.

- Nelke, R., Nabrdalik, M., Żurek, M., Kudrys, P., Hendel, P., Nowakowski, M., Moliszewska, E.B. Nematocidal Properties of Wild Strains of Pleurotus ostreatus Progeny Derived from Buller Phenomenon Crosses. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14(17), 7980. [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowski, G. Wpływ chwastów na populację Heterodera schachtii Schmidt na polach gospodarstw buraczanych. Doctoral thesis in Polish [The influence of weeds on the population of Heterodera schachtii Schmidt in the fields of sugar beet farms.]. Akademia Techniczno-Rolnicza, Bydgoszcz 1992, pp. 63.

- Stiernagle, T. Maintenance of C. elegans (February 11, 2006), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook. doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1.

- Landi, N., Ragucci, S., Russo, R., Valletta, M., Pizzo, E., Ferreras, J.M., Di Maro, A. The ribotoxin-like protein Ostreatin from Pleurotus ostreatus fruiting bodies: Confirmation of a novel ribonuclease family expressed in basidiomycetes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1329–1336.

- Žužek, M.C., Maček, P., Sepčić, K., Cestnik, V., Frangež, R. Toxic and lethal effects of ostreolysin, a cytolytic protein from edible oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), in rodents. Toxicon 2006, 48, 264–271.

- Hemayati, S.S., Jahad-e Akbar, M.-R., Ghaemi, A.-R., Fasahat, P. Efficiency of white mustard and oilseed radish trap plants against sugar beet cyst nematode, Applied Soil Ecology 2017, 119, 192-196. [CrossRef]

- Reuther, M., Lang, C., Grundler, F.M.W. Nematode-tolerant sugar beet varieties – resistant or susceptible to the Beet Cyst Nematode Heterodera schachtii?. Sugar Industry 2017, 142(5), 277-284. [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, A., Yazdani, R., Quintanilla, M. Host Status and Management Potential of Selected Cover Crops for Heterodera schachtii. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5316485 or. [CrossRef]

- Lee C.-H. et al. A carnivorous mushroom paralyzes and kills nematodes via a volatile ketone. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade4809. [CrossRef]

- Daub, M. The beet cyst nematode (Heterodera schachtii): an ancient threat to sugar beet crops in Central Europe has become an invisible actor. In: Integrated Nematode Management: State-of-the-art and visions for the future, R.A. Sikora et al. Eds. CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2021; pp. 394-399. [CrossRef]

- Koch, D.W., Gray, F.A., Krall, J.M. Trap Crops: A promising Alternative for sugar beet Nematode Control. University of Wyoming Cooperative Extension Service Department of Plant Sciences, B-1029R, 1999. https://courses.cit.cornell.edu/ipm444/lec-notes/extra/pest-mgmt-sugar-beet-cyst-nematode.pdf.

- Dehdari, M., Charehgani, H., Fatemi, E. Evaluation of canola (Brassica napus L.) resistance to sugar beet cyst nematode (Heterodera schachtii Schm.) and its association with SSR molecular markers using parametric and non-parametric statistical methods. Indian Phytopathology 2022, 75(2), 467-476.

- Yosano, S., Kitabayashi, S., Sakai, H. Field trial of trap cropping against the sugar beet cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii (Rhabditida: Heteroderidae) in Japan. Applied Entomology and Zoology 2025, 60(1), 67-71.

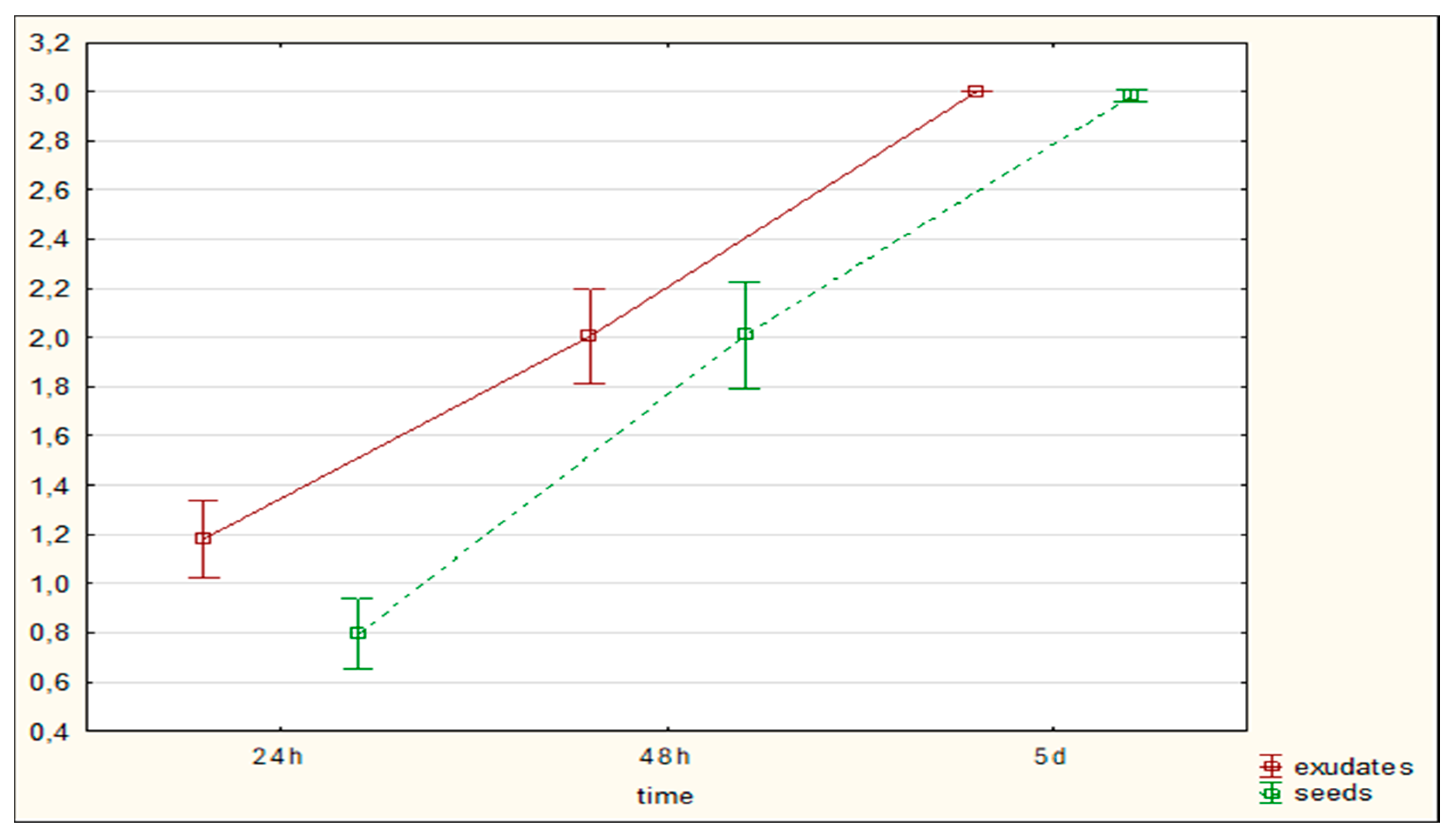

Figure 1.

The influence of exudates and the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity against C. elegans movement after 5 hours of co-incubation; bars indicate standard deviation (SD); control – without plants.

Figure 1.

The influence of exudates and the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity against C. elegans movement after 5 hours of co-incubation; bars indicate standard deviation (SD); control – without plants.

Figure 2.

The influence of exudates and presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity against C. elegans movement – average for the experiment 1-48 hours of co-incubation; control – without plants.

Figure 2.

The influence of exudates and presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity against C. elegans movement – average for the experiment 1-48 hours of co-incubation; control – without plants.

Figure 3.

The influence of C. elegans together with plant exudates or the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity in developing toxocysts after 5 hours of co-incubation; bars indicate standard deviation (SD).

Figure 3.

The influence of C. elegans together with plant exudates or the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity in developing toxocysts after 5 hours of co-incubation; bars indicate standard deviation (SD).

Figure 4.

The influence of C. elegans together with plant exudates or the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity in developing toxocysts – average for the experiment 1-48 hours of co-incubation.

Figure 4.

The influence of C. elegans together with plant exudates or the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity in developing toxocysts – average for the experiment 1-48 hours of co-incubation.

Figure 6a, 6b, 6c.

Graphs obtained under the ANOVA analyses of the joint action of plants’ type (left) or their exudates or seeds (center), and mycelia, and in general plant type tendency (right) on the C. elegans movement after 5 h; in these, the tests data do not present statistical significance.

Figure 6a, 6b, 6c.

Graphs obtained under the ANOVA analyses of the joint action of plants’ type (left) or their exudates or seeds (center), and mycelia, and in general plant type tendency (right) on the C. elegans movement after 5 h; in these, the tests data do not present statistical significance.

Figure 7a, 7b.

Graphs obtained under the ANOVA analyses of the joint action of mycelium and roots’ or seeds’ diffusates types (left) and the exudates or seeds (right) influence on mycelia ability to produce toxocysts after 5 h , in the presence of C. elegans; in these tests, the data do not present statistical significance.

Figure 7a, 7b.

Graphs obtained under the ANOVA analyses of the joint action of mycelium and roots’ or seeds’ diffusates types (left) and the exudates or seeds (right) influence on mycelia ability to produce toxocysts after 5 h , in the presence of C. elegans; in these tests, the data do not present statistical significance.

Figure 8.

The influence of plant exudates on the P. ostreatus mycelia activity in cyst entwining by growing hyphae after 24 and 48 h; controls – without exudates.

Figure 8.

The influence of plant exudates on the P. ostreatus mycelia activity in cyst entwining by growing hyphae after 24 and 48 h; controls – without exudates.

Figure 9.

The influence of the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity in cyst entwining by growing hyphae after 24 and 48 h; controls – without seeds.

Figure 9.

The influence of the presence of seeds on the P. ostreatus mycelium activity in cyst entwining by growing hyphae after 24 and 48 h; controls – without seeds.

Figure 10.

The influence of the tested mycelia on the overgrowing of H. schachtii cysts under the influence of plants' exudates; data did not differ significantly.

Figure 10.

The influence of the tested mycelia on the overgrowing of H. schachtii cysts under the influence of plants' exudates; data did not differ significantly.

Figure 11.

The influence of plant exudates on the results of H. schachtii cysts overgrowing by tested mycelia; data did not differ significantly.

Figure 11.

The influence of plant exudates on the results of H. schachtii cysts overgrowing by tested mycelia; data did not differ significantly.

Figure 12.

The result of time on the H. schachtii cysts overgrowing by the tested mycelia under the plant exudates influence; data differed significantly in groups (exudates/seeds).

Figure 12.

The result of time on the H. schachtii cysts overgrowing by the tested mycelia under the plant exudates influence; data differed significantly in groups (exudates/seeds).

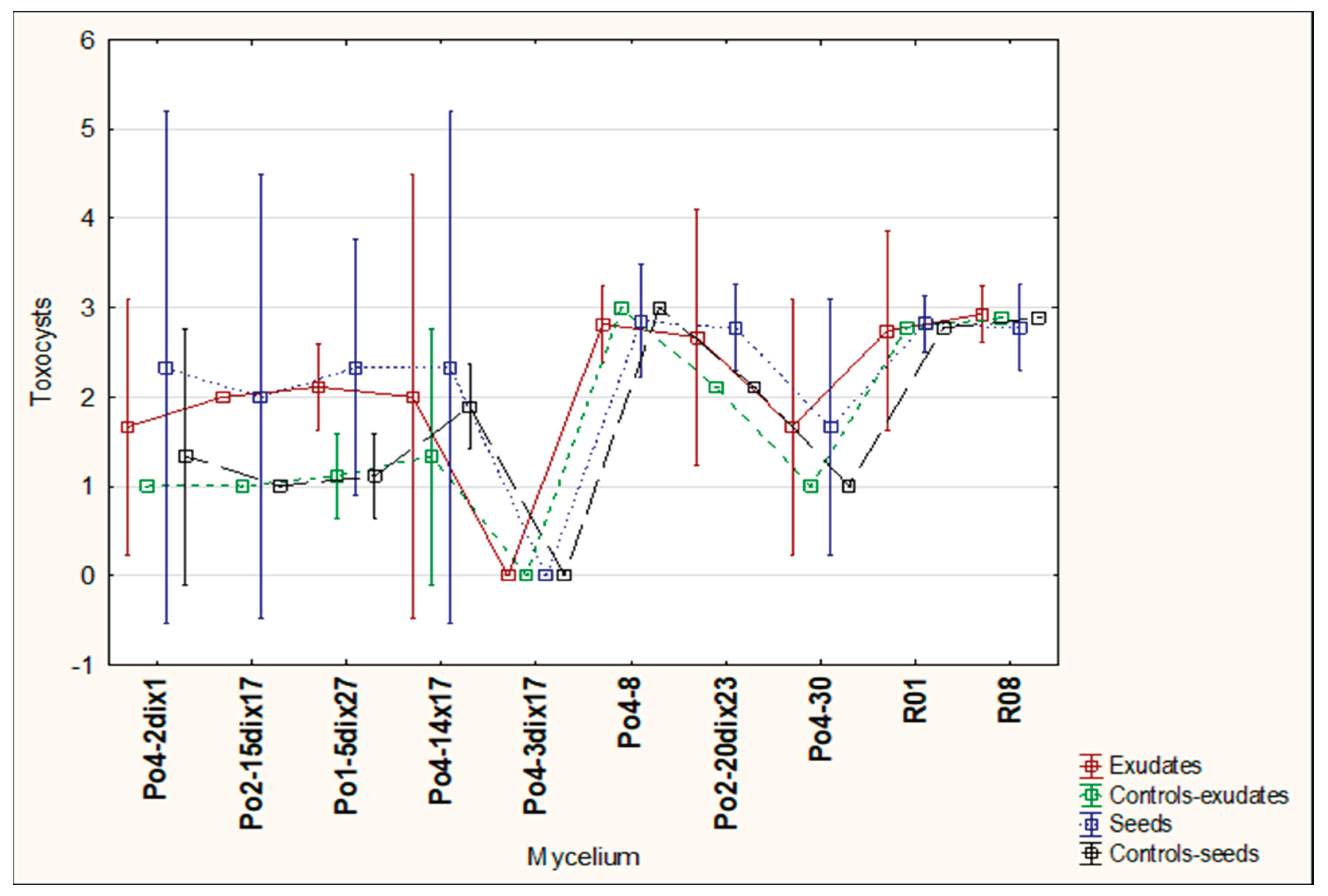

Figure 13.

The activity of the tested mycelia in toxocysts production under the influence of plant exudates/seeds and the presence of the H. schachtii cysts; control variants were estimated without cysts presence; data differed statistically in groups (exudates/seeds).

Figure 13.

The activity of the tested mycelia in toxocysts production under the influence of plant exudates/seeds and the presence of the H. schachtii cysts; control variants were estimated without cysts presence; data differed statistically in groups (exudates/seeds).

Figure 14.

The influence of the tested plants (exudates/seeds) on the toxocysts production by the mycelia; control variants were estimated without cysts presence; data differed statistically in groups (exudates/seeds).

Figure 14.

The influence of the tested plants (exudates/seeds) on the toxocysts production by the mycelia; control variants were estimated without cysts presence; data differed statistically in groups (exudates/seeds).

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between the ability to form of toxocysts by tested mycelia and C. elegans movement assessments in various time of experiments.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between the ability to form of toxocysts by tested mycelia and C. elegans movement assessments in various time of experiments.

| Compared parameters |

Correlation coefficient |

| 5h tox. vs. 5h mov. |

-0,44 |

| 1-48h tox. vs. 1-48 h mov. |

-0,49 |

| 1-48h tox. vs. 5h mov. |

-0,49 |

Table 2.

The tested mycelia ability to inhibit C. elegans movement after 5 hours of the experiment and the average toxocysts production in the whole test (1-48 h); the data were assessed using one-way analysis of variance and the significance of differences was assessed using Duncan's test.; data followed by the same letters do not differ significantly in columns.

Table 2.

The tested mycelia ability to inhibit C. elegans movement after 5 hours of the experiment and the average toxocysts production in the whole test (1-48 h); the data were assessed using one-way analysis of variance and the significance of differences was assessed using Duncan's test.; data followed by the same letters do not differ significantly in columns.

| Mycelium |

Movemnet

5 h

|

Toxocysts

1-48 h

|

| Po4 - 3di x 17 |

2.60 c |

0.00 d |

| Po4 - 8 |

1.00 a |

2.49 ab |

| Po2- 20di x 23 |

0.98 a |

2.52 ab |

| Po4 - 30 |

1.83 b |

2.21 bc |

| Po4 - 2dix1 |

1.99 b |

2.44 abc |

| Po2 - 15dix17 |

1.81 b |

2.08 c |

| Po1 - 5dix27 |

1.95 b |

2.36 abc |

| Po4 - 14x17 |

2.03 b |

2.21 bc |

| R01 |

1.00 a |

2.36 abc |

| R08 |

1.00 a |

2.71 a |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).