Submitted:

09 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Egg parasitoids, such as Telenomus remus, face significant challenges after release, as their pupae are exposed to various mortality factors that reduce the efficiency of biological control programs. In this context, this study aimed to evaluate a solid diet that In this context, this study aimed to evaluate a solid diet that allows feeding adults while still inside the release capsules, enabling its storage and field application for adults. Three independent bioassays were performed, each with 20 completely randomized replications. The first bioassay evaluated the acceptance of a solid feed, honey soaked in cotton thread, compared to the traditional form, honey droplets. In the second bioassay, the storage periods after emergence of adults in capsules with solid food were analyzed, at 2, 4, 6 and 8 days post-emergence and the third bioassay was studied the efficacy of different release densities under field conditions. The results showed that the solid diet was well accepted in relation to the traditional diet, in addition, T. remus resulted in lower mortality inside the capsules, living up to four days without significant reductions in biological parameters or parasitism capacity. Therefore, the recommended dose of 20,000 parasitoids per hectare is not enough to keep S. frugiperda under economic thresholds. The flexibility of until four days to the release and the insights regarding the densitys provide a valuable improvement to establish T. remus as a biocontrol agent.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Insects Rearing

2.2. Experiment 1: Parasitism Capacity of Telenomus remus Fed on Liquid (Honey Droplets) vs. Solid Honey Diet)

2.3. Experiment 2: Shelf Life of Adults of T. remus Inside Capsules with a Honey in Tiny Droplets Diet

2.4. Experiment 3: Field Performance of T. remus Under Different Release Densities

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

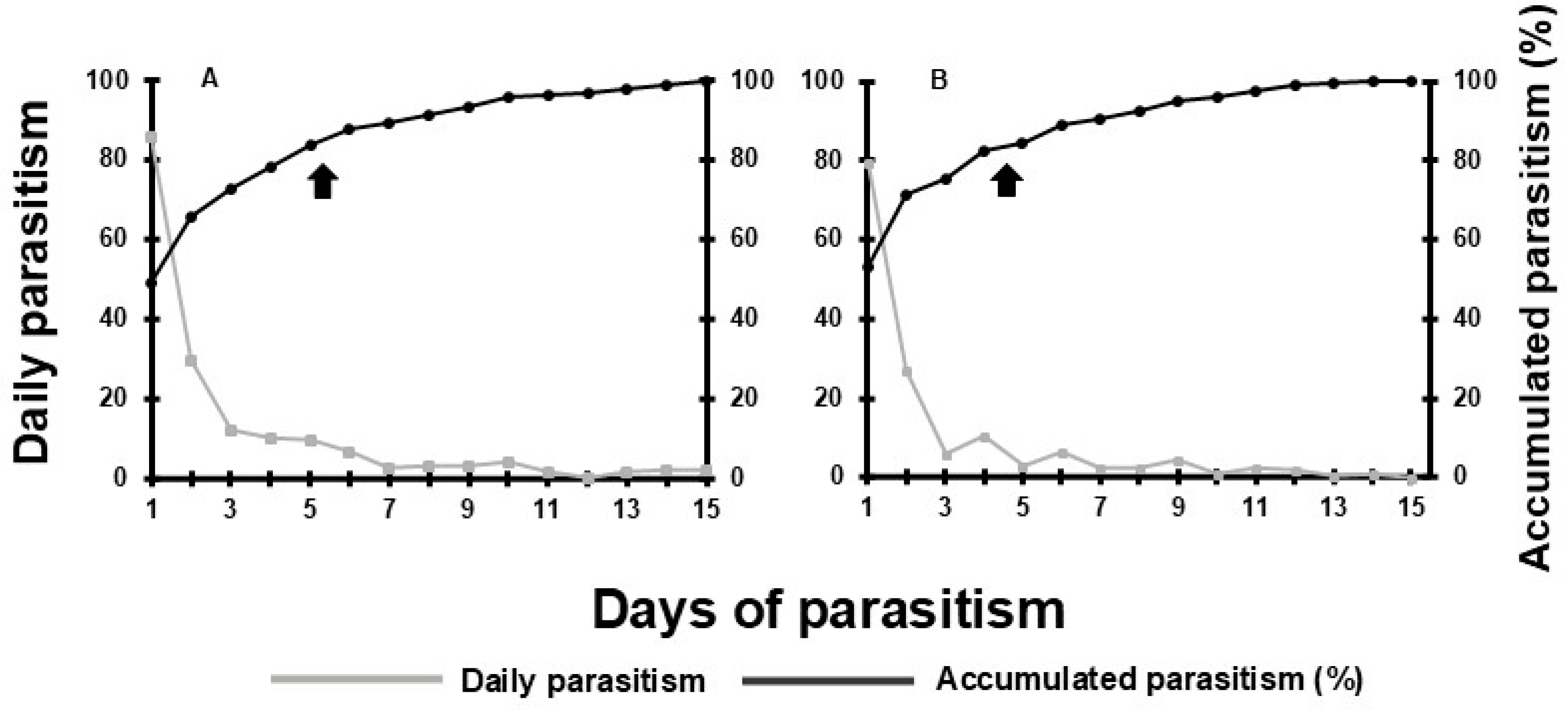

3.1. Experiment 1: Parasitism Capacity of T. remus Fed with Liquid Diet (Honey in Tiny Droplets) Compared to Honey-Solid Diet

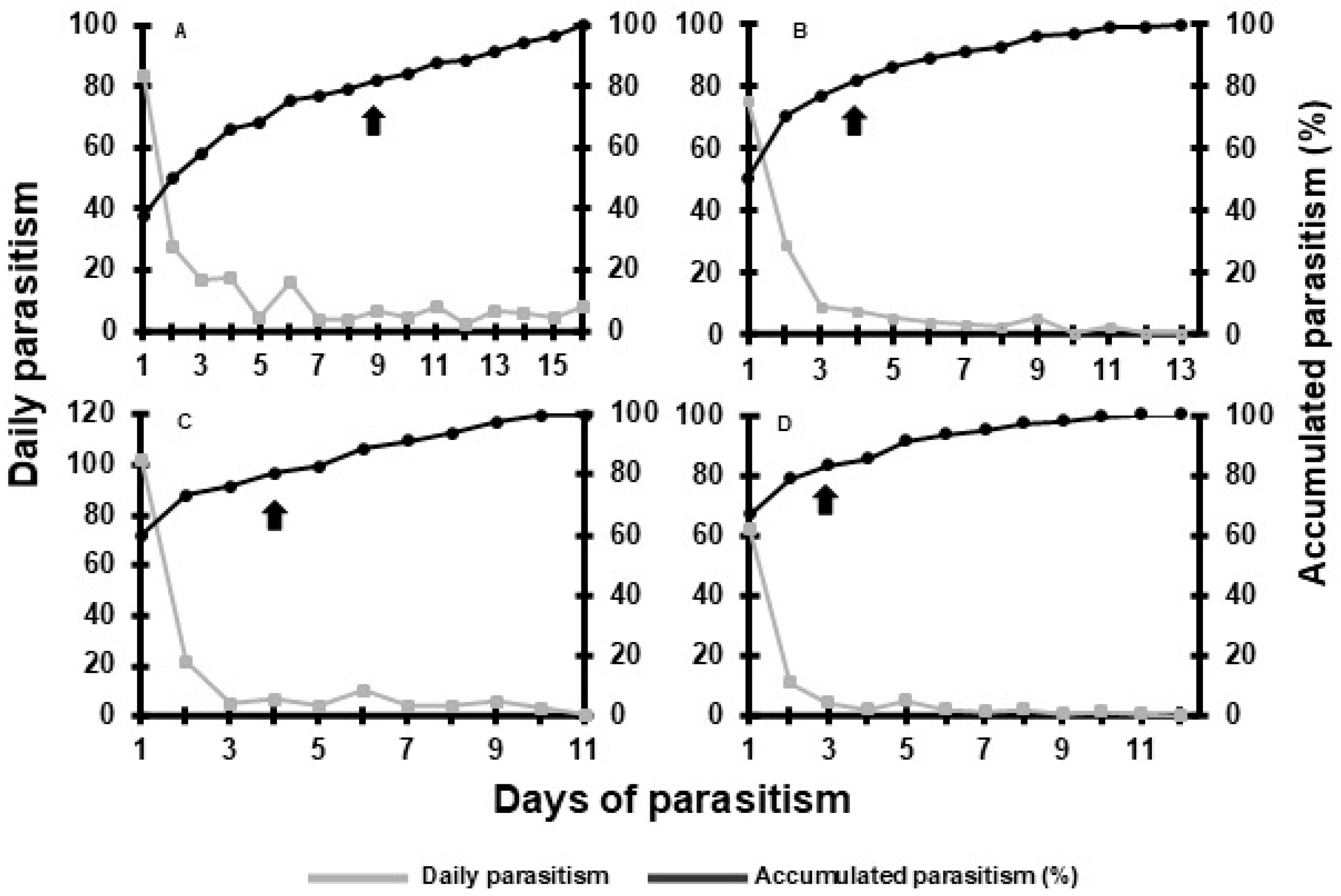

3.2. Experiment 2: Shelf Life (Storage Period in Days) of Adults of T. remus Inside Capsules with a Honey-Solid Diet

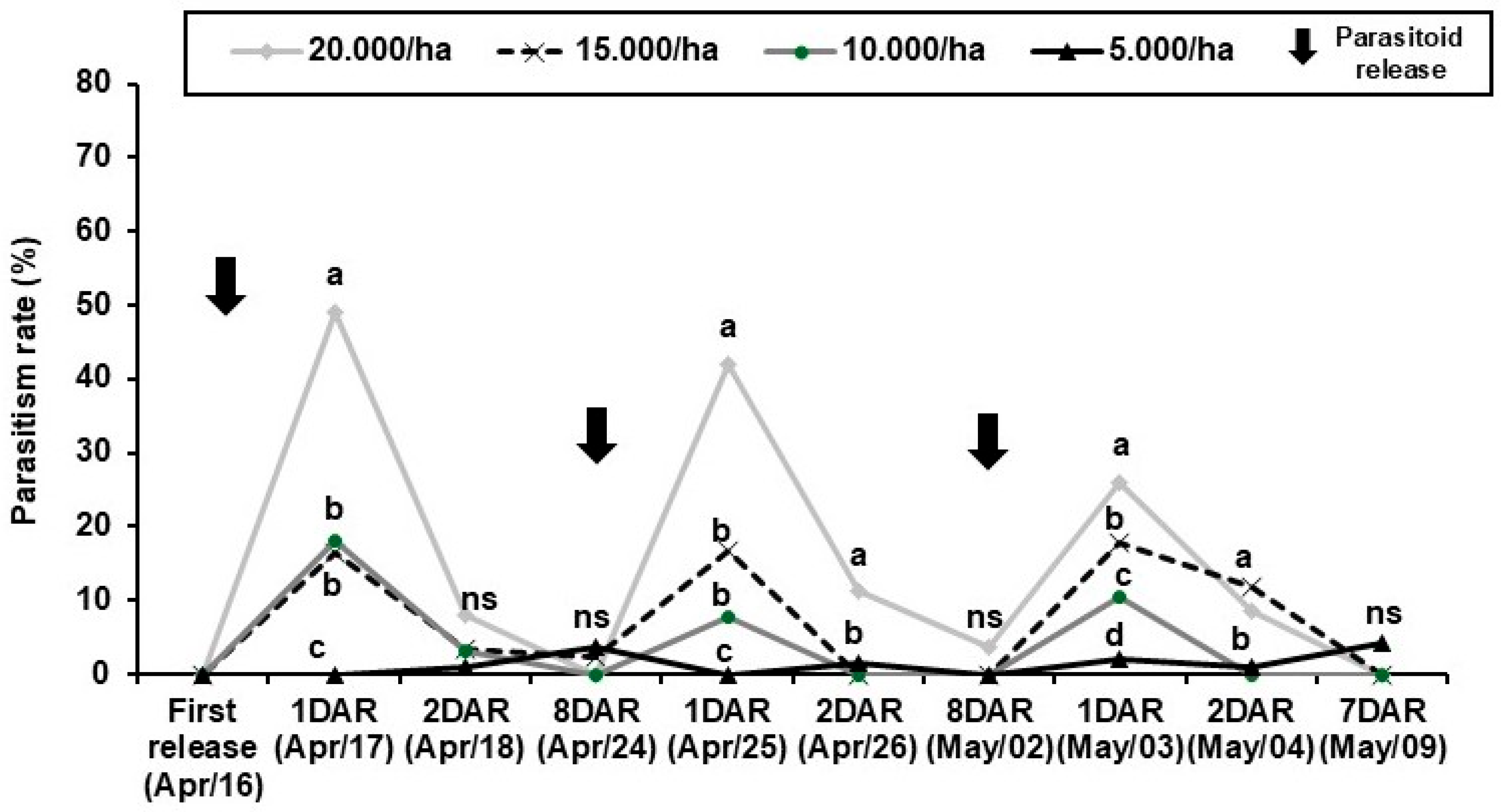

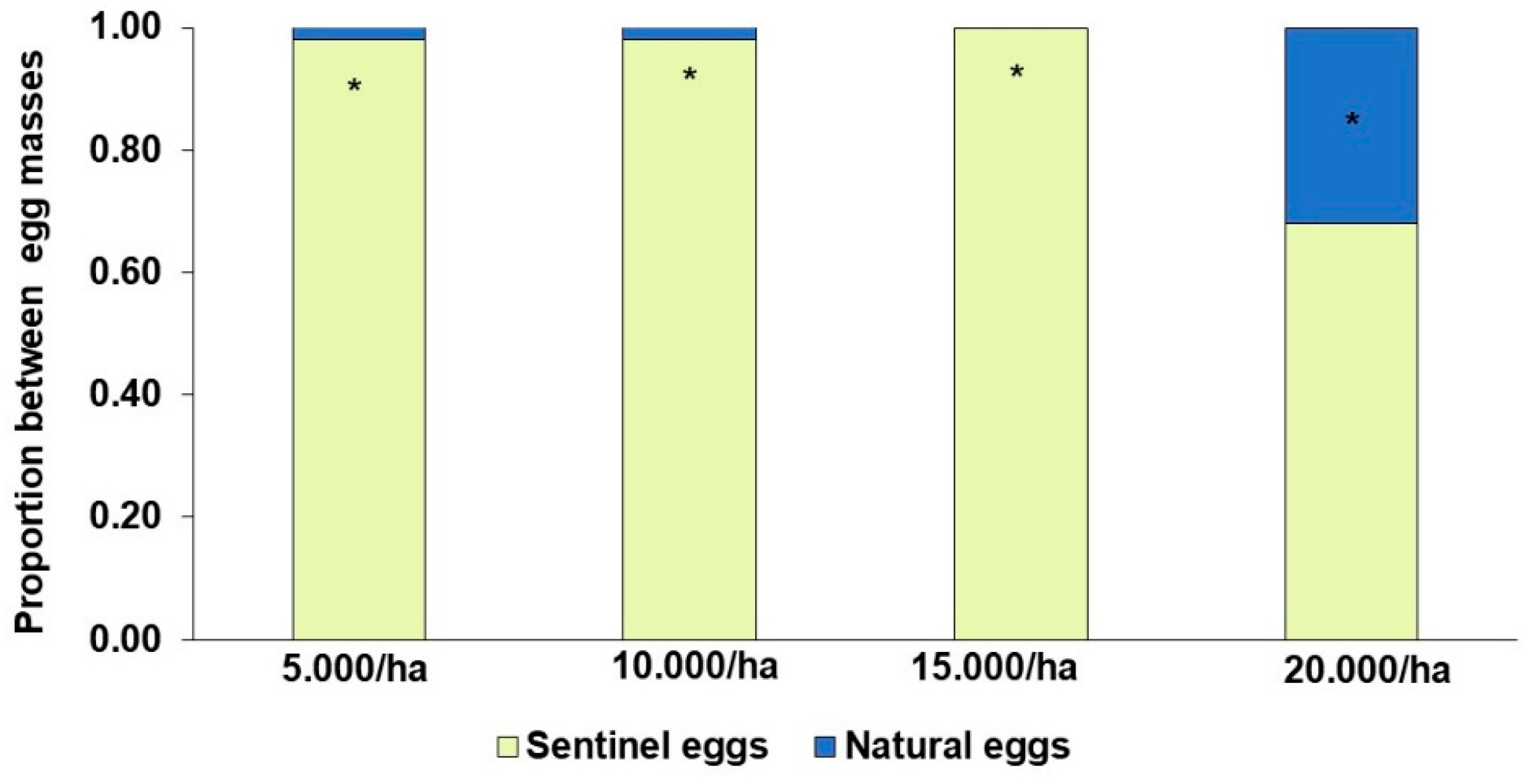

3.3. Experiment 3: Field Performance of T. remus Under Different Release Densities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflict of Interests

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Kenis, M.; du Plessis, H.; van den Berg, J.; Ba, M.N.; Goergen, G.; Kwadjo, K.E. Telenomus remus, a candidate parasitoid for the biological control of Spodoptera frugiperda in Africa, is already present on the continent. Insects 2019, 10(4), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Colmenarez, Y.C.; Babendreier, D.; Ferrer Wurst, F.R.; Vásquez-Freytez, C.L.; Bueno, A.F. The use of Telenomus remus (Nixon, 1937) (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) in the management of Spodoptera spp.: Potential, challenges, and main benefits. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2022, 3, 5. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.; Bueno, A.F.; Desneux, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Zang, L.S. Current status of biological control of fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda by egg parasitoids. J. Pest Sci. 2023, 96, 1345–1363. [CrossRef]

- Horikoshi, R.J.; Vertuan, H.; Castro, A.A.; Morrell, K.; Griffith, C.; Evans, A.; Tan, J.; Asiimwe, P.; Anderson, H.; José, M.O.M.A.; et al. A new generation of Bt maize for control of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda). Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 3227–3736. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Kerns, D.L. Resistance of Spodoptera frugiperda to Cry1, Cry2, and Vip3Aa Proteins in Bt Corn and Cotton in the Americas: Implications for the Rest of the World. J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 1752–1760. [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, J.; du Plessis, H. Chemical control and insecticide resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 1761–1771. [CrossRef]

- EFSA European Food Safety Authority, Nougadère, A.; Rzpecka, D.; Makowski, D.; Paoli, F.; Turillazzi, F.; Scala, M.; Sánchez, B.; Baldassarre, F.; Tramontini, S.; Vos, S. Spodoptera frugiperda – Pest Report to Support the Ranking of EU Candidate Priority Pests. EFSA Supporting Publication 2025, 22, EN-9266. [CrossRef]

- Ngegba, P.M.; Khalid, M.Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhong, G. An overview of insecticide resistance mechanisms, challenges, and management strategies in Spodoptera frugiperda. Crop Prot. 2025, 197, 107322.

- Agboyi, L.; Layodé, B.F.R.; Fening, K.O.; Beseh, P.; Attuquaye Clottey, V.; Day, R.; Kenis, M.; Babendreier, D. Assessing the potential of inoculative field releases of Telenomus remus to control Spodoptera frugiperda in Ghana. Insects 2021, 12, 665. [CrossRef]

- EPPO. EPPO Global Database: Spodoptera frugiperda distribution. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/LAPHFR/distribution (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Kenis, M.; Benelli, G.; Biondi, A.; Calatayud, P.-A.; Day, R.; Desneux, N.; Harrison, R.D.; Kriticos, D.; Rwomushana, I.; van den Berg, J.; Verheggen, F.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Agboyi, L.K.; Ahissou, R.B.; Ba, M.; Bernal, J.; Bueno, A.F.; Carriere, Y.; Carvalho, G.A.; Chen, X.-X.; Cicero, L.; Plessis, H.D.; Early, R.; Fallet, P.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Firake, D.M.; Goergen, G.; Groot, A.T.; Gupta, A.; Hu, G.; Huang, F.; Jaber, L.R.; Malo, E.; Meagher, R.J.J.; Mohamed, S.; Sanchez, D.M.; Nagoshi, R.N.; Negre, N.; Niassy, S.; Noboru, O.; Nyamukondiwa, C.; Omoto, C.; Palli, R.S.; Pavela, R.; Ramirez-Romero, R.; Rojas, J.; Subramanian, S.; Tabashnik, B.E.; Tay, W.T.; Virla, E.G.; Wang, S.; Williams, T.; Zang, L.-S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, K. Invasiveness, biology, ecology, and management of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 43(2), 187–241. [CrossRef]

- Togola, A.; Beyene, Y.; Bocco, R.; Tepa-Yotto, G.; Gowda, M.; Too, A.; Boddupalli, P. Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in Africa: Insights into biology, ecology and impact on staple crops, food systems and management approaches. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1538198.

- Gonzalez-Cabrera, J.; García-García, R.E.; Vega-Chavez, J.L.; Contreras-Bermudez, Y.; Mejía-García, N.; Ángeles-Chavez, E.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, J.A. Biological and population parameters of Telenomus remus and Trichogramma atopovirilia as biological control agents for Spodoptera frugiperda. Crop Prot. 2025, 188, 106995.

- Pomari-Fernandes, A.; Bueno, A.F.; De Bortoli, S.A.; Favetti, B.M. Dispersal capacity of the egg parasitoid Telenomus remus Nixon (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) in maize and soybean crops. Biol. Control 2018, 126, 158–168. [CrossRef]

- Pomari, A.F.; Bueno, A.F.; Bueno, R.C.O.F.; Menezes Junior, A.O.; Fonseca, A.C.P.F. Releasing number of Telenomus remus (Nixon) (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) against Spodoptera frugiperda Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in corn, cotton, and soybean. Ciênc. Rural 2013, 43, 377–382. [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, M.; Bennett, F.D.; Barrow, R.M. Introduction of exotic parasites for control of Spodoptera frugiperda in Trinidad, the eastern Caribbean and Latin America. In Urgent Plant Pest and Disease Problems in the Caribbean, Braithwaite, C.W.D., Pollard, G.V., Eds.; Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture: Ocho Rios, Jamaica, 1981; pp. 161–171.

- Cock, M.J.W. A review of biological control of pests in the Commonwealth Caribbean and Bermuda up to 1982. Commonwealth Institute of Biological Control Technical Communication; Commonwealth Institute of Biological Control: Farnham Royal, United Kingdom, 1985.

- Hernández, D.; Ferrer, F.; Linares, B. Introducción de Telenomus remus Nixon (Hym: Scelionidae) para controlar Spodoptera frugiperda (Lep: Noctuidae) en Yaritagua, Venezuela. Agron. Trop. 1989, 39(1), 199–205.

- García-Roa, F.; Mosquera, E.M.T.; Vargas, S.C.A.; Rojas, A.L. Control biológico, microbiológico y físico de Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), plaga del maíz y otros cultivos en Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2002, 28, 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, W.F. Biological control of agricultural pests in Venezuela: Historical achievements of Servicio Biológico (SERVBIO). Rev. Cienc. Ambient. 2021, 55, 327–344. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.S.; Parra, J.R.P. Liberação de inimigos naturais. In Controle biológico no Brasil: Parasitoides e predadores, Parra, J.R.P., Botelho, P.S.M., Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S., Bento, J.M.S., Eds.; Manole: Barueri, SP, Brazil, 2002; pp. 325–342.

- Schwartz, A.; Gerling, D. Adult biology of Telenomus remus [Hymenoptera: Scelionidae] under laboratory conditions. Entomophaga 1974, 19, 483–492.

- Denis, D.; Pierre, J.S.; van Baaren, J.; van Alphen, J.J. How temperature and habitat quality affect parasitoid lifetime reproductive success—a simulation study. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 1604–1613. [CrossRef]

- Mubayiwa, M.; Machekano, H.; Mvumi, B.M.; Opio, W.A.; Segaiso, B. et al. Thermal performance drifts between the egg parasitoid Telenomus remus and the fall armyworm may threaten the efficacy of biological control under climate change. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2025, 173, 338–350.

- Sampaio, F.; Marchioro, C.A.; Foerster, L.A. Modeling parasitoid development: Climate change impacts on Telenomus remus (Nixon) and Trichogramma foersteri (Takahashi) in southern Brazil. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Grande, M.L.M.; Queiroz, A.P.; Gonçalves, J.; Hayashida, R.; Ventura, M.U.; Bueno, A.F. Impact of environmental variables on parasitism and emergence of Trichogramma pretiosum, Telenomus remus and Telenomus podisi. Neotrop. Entomol. 2021, 50(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Parra, J.R.P. Biological control in Brazil: An overview. Sci. Agric. 2014, 71, 345–355. [CrossRef]

- Gomes Garcia, A.; Wajnberg, E.; Parra, J.R.P. Optimizing the releasing strategy used for the biological control of the sugarcane borer Diatraea saccharalis by Trichogramma galloi with computer modeling and simulation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9535.

- Linares, B. Farm family rearing of egg parasites in Venezuela. Biocontrol News Inform. 1998, 19, 76N.

- Cave, R.D.; Acosta, N.M. Telenomus remus Nixon: un parasitoide en el control biológico del gusano cogollero, Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith). Ceiba 1999, 40, 215–227.

- Ferrer, F. Biological of agricultural insect pest in Venezuela; advances, achievements, and future perspectives. Biocontrol News Inf. 2001, 22, 67–74.

- Figueiredo, M.L.C.; Lucia, T.M.C.D.; Cruz, I. Effect of Telenomus remus Nixon (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) density on control of Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) egg masses upon release in a maize field. Rev. Bras. Milho Sorgo 2002, 1, 12–19.

- Cruz, I. Controle biológico de pragas na cultura de milho para a produção de conservas (minimilho) por meio de parasitoides e predadores. Circular Técnica 2007, 91, Embrapa Milho e Sorgo, Sete Lagoas, MG, Brazil, 16 p.

- Varella, A.C.; Menezes-Netto, A.C.; Alonso, J.D.S.; Caixeta, D.F.; Peterson, R.K.D.; Fernandes, O.A. Mortality dynamics of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) immatures in maize. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130437.

- Ivan, I.A.F.; Silva, K.R.; Loboschi, D.L.; Araujo-Junior, L.P.; Sanots, A.J.P.S.; Pinto, A.S. Número de liberações de Telenomus remus no controle de ovos de Spodoptera frugiperda em milho de segunda safra. In Proceedings of the XXXI Congresso Nacional de Milho e Sorgo, Bento Gonçalves, RS, Brazil, 2016, pp. 289–293.

- Rezende SK, Loboschi DL, Alexandre NO, Carneiro RP, Arroyo BM, Pinto AS. Quantidade liberada de Telenomus remus no controle de ovos de Spodoptera frugiperda em milho de segunda safra. XXXI Congresso Nacional de Milho e Sorgo. 2016. p.308–313. Available at: http://www. abms.org.br/cnms2016_trabalhos/docs/1145.pdf.

- Salazar-Mendoza, P.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Fernandes, O.A. Release density, dispersal capacity, and optimal rearing conditions for Telenomus remus, an egg parasitoid of Spodoptera frugiperda, in maize. Biocontrol Sci. Techn. 2020, 3, 1–20.

- Collier, T.; van Steenwyk, R. A critical evaluation of augmentative biological control. Biol. Control 2004, 31, 245–256.

- Crowder, D.W. Impact of release rates on the effectiveness of augmentative biological control agents. J. Insect Sci. 2007, 7, 15.

- Roswadoski, L.; Sutil, W.P.; Carneiro, G.S.; Maciel, R.M.A.; Coelho Jr, A.; Bueno, A.F. Release strategy and egg parasitism of Telenomus podisi adults fed with different diets. Biol. Control 2024, 198, 105626. [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Hoffmann-Campo, C.B.; Corso, I.C.; Oliveira, L.J.; Moscardi, F.; Panizzi, A.R.; Bueno, A.F.; Hirose, E.; Roggia, S. Manual de identificação de insetos e outros invertebrados da cultura da soja; Embrapa Soja: Londrina – PR, Brazil, 2014.

- Greene, G.L.; Leppla, N.C.; Dickerson, W.A. Velvet bean caterpillar: A rearing procedure and artificial medium. J. Econ. Entomol. 1976, 69(4), 488–497. [CrossRef]

- Butt, B.A. Sex determination of lepidopterous pupae; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1962; pp. 33–75.

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; van Benthem, K.J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C.W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H.J.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378–400.

- Lenth, R. Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means; R Package Version 1.8.6, 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Bueno, A.F.; Braz, É.C.; Favetti, B.M.; de Barros França-Neto, J.; Silva, G.V. Release of the egg parasitoid Telenomus podisi to manage the Neotropical Brown Stink Bug, Euschistus heros, in soybean production. Crop Prot. 2020, 137, 105310. [CrossRef]

- Braz, É.C.; Bueno, A.F.; Colombo, F.C.; Queiroz, A.P. Temperature impact on Telenomus podisi emergence in field releases of unprotected and encapsulated parasitoid pupae. Neotrop. Entomol. 2021, 50, 462–469. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.F.; Sutil, W.P.; Maciel, R.M.A.; Roswadoski, L.; Colmenarez, Y.C.; Colombo, F.C. Challenges and opportunities of using egg parasitoids in augmentative biological control of FAW in Brazil. Biol. Control 2023, 186, 105344. [CrossRef]

- Cave, R.D. Biology, ecology and use in pest management of Telenomus remus. Biocontrol News Inf. 2000, 21, 21–26.

- Lewis, W.; Stapel, J.O.; Cortesero, A.M.; Takasu, K. Understanding how parasitoids balance food and host needs: Importance to biological control. Biol. Control 1998, 11(2), 175–183.

- Kishinevsky, M.; Keasar, T.; Sivinski, J.; Segoli, M. Sugar feeding increases the lifespan and parasitism rates of a parasitoid wasp under field conditions. Ecol. Entomol. 2018, 43(6), 621–628. [CrossRef]

- Straser, R.K.; Wilson, H. Food deprivation alters reproductive performance of biocontrol agent Hadronotus pennsylvanicus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11322. [CrossRef]

- Montecelli, L.S.; Tena, A.; Idier, M.; Amiens-Desneux, E.; Desneux, N. Quality of aphid honeydew for a parasitoid varies as a function of both aphid species and host plant. Biol. Control 2020, 140, 104099. [CrossRef]

- Tuncbilek, A.S.; Bilbil, H.; Bakir, S.; Silici, S. The performance of Trichogramma (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) parasitoids feeding on honey sources. Tarım Bilimleri Derg. 2021, 27, 400–406. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, R.C.O.F.; Carneiro, T.R.; Bueno, A.F.; Pratissoli, D.; Fernandes, O.A.; Vieira, S.S. Parasitism capacity of Telenomus remus Nixon (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) on Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) eggs. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2010, 53, 1339.

- Vieira, N.F.; Pomari-Fernandes, A.; Lemes, A.A.F.; Vacari, A.M.; De Bortoli, S.A.; Bueno, A.F. Cost of production of Telenomus remus (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) grown in natural and alternative hosts. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 110, 2724–2726.

- Queiroz, A. P. D., Favetti, B. M., Luski, P. G. G., Gonçalves, J., Neves, P. M. O. J., Bueno, A. D. F. (2019). Telenomus remus (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) parasitism on Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) eggs: different parasitoid and host egg ages. Semina ciênc. agrar, 2933-2946.

- Queiroz, A.P.D.; Bueno, A.D.F.; Pomari-Fernandes, A.; Bortolotto, O.C.; Mikami, A.Y.; Olive, L. Influence of host preference, mating, and release density on the parasitism of Telenomus remus (Nixon) (Hymenoptera, Platygastridae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 2017, 61, 86–90.

| Diet | Lifetime number of parasitized eggs/female1 | Emergence (%)2 | Progeny sex ratio2 | Parental longevity of adult females (days)3 |

| 100% honey in tiny droplets | 165.4 ± 5.88 a | 77.7 ± 1.84 a | 0.69 ± 0.04 a | 10.4 ± 0.71 a |

| 100% honey in macerated cotton strings | 143.4 ± 4.57 b | 73.7 ± 1.01 b | 0.70 ± 0.02 a | 10.1 ± 0.40 a |

| Days of storage after parasitoid emergence | Lifetime number of parasitized eggs/female1 | Emergence (%)2 | Progeny sex ratio2 | Parental longevity of adult females (days)3 |

| 2 | 193.4 ± 8.82 a | 79.9 ± 1.78 a | 0.74 ± 0.02 a | 11.5 ± 0.63 a |

| 4 | 143. 6 ± 4.35 b | 74.4 ± 1.75 b | 0.80 ± 0.01 a | 10.0 ± 0.35 a |

| 6 | 150.4 ± 14.79 b | 76.5 ± 1.79 b | 0.56 ± 0.04 b | 7.4 ± 0.69 b |

| 8 | 86.6 ± 5.63 c | 80.5 ± 1.88 a | 0.71 ± 0.08 a | 7.1 ± 0.54 b |

| Days after parasitoid emergence | Emergence (%) of adults from pupae inside capsules | Dead adults (%) trapped inside capsules |

| 2 | 69.8 ± 2.76 a | 2.1 ± 0.61 a |

| 4 | 74.6 ± 2.56 a | 5.2 ± 0.50 b |

| 6 | 73.3 ± 3.58 a | 5.9 ± 1.03 b |

| 8 | 75.0 ± 0.97 a | 5.5 ± 0.80 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).