Methodology of Literature Review

To develop a balanced and well-grounded understanding of the current state of metal additive manufacturing, a structured literature search was carried out using major scientific databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink. The review primarily considers studies published between 2015 and 2024, with a stronger emphasis on work appearing after 2020, reflecting the rapid growth in AM research, especially in areas related to defect prediction, mitigation, and AI-enabled monitoring [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

12,

20,

29,

30,

31]. Earlier foundational publications were included where they provided essential background or helped explain the underlying science behind shrinkage, porosity, and microstructure evolution in LPBF and related processes [

7,

8,

9,

37,

51]. A combination of targeted keyword searches and Boolean terms was used (e.g.,

“LPBF shrinkage,” “porosity in SLM,” “hot isostatic pressing,” “digital twin additive manufacturing,” “machine learning for porosity prediction”) to identify research that contributed clear technical insights or practical relevance. This approach aligns with review strategies adopted by recent studies focusing on porosity mechanisms, characterization, and defect modelling in powder-bed fusion [

12,

13,

20]. Each publication was screened based on its technical depth, methodology quality, industry or scientific impact, and relevance to key themes such as process optimization, post-processing improvements, real-time defect detection, and data-driven control framework ks [

1,

21,

27,

40,

75,

87]. Only peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and technical reports published in English were considered, with industrial case studies referenced selectively where they provided practical context [

39]. In total, more than 100 publications spanning mechanical, aerospace, biomedical, materials, and computational engineering were examined. This broad yet focused approach allowed the review to build a mechanism-oriented narrative linking how defects form, how they can be detected, and how emerging technologies are reshaping mitigation strategies across the metal AM landscape [

12,

20,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

1. Introduction

Metal additive manufacturing (AM) commonly referred to as metal 3D printing has evolved from an experimental prototyping method into a transformative production route for lightweight, highly detailed, and functionally demanding components used across aerospace, biomedical, automotive, and energy sectors [

9,

16,

19,

20,

21,

22,

35]. Processes such as Selective Laser Melting (SLM), Electron Beam Melting (EBM), and Directed Energy Deposition (DED) enable the creation of near-net-shape geometries through layer-by-layer consolidation of metal feedstock. This precise thermal control allows engineers to tailor microstructures, embed features internally, and explore complex designs that were once impossible with conventional machining or casting [

7,

15]. This shift in manufacturing philosophy has unlocked opportunities such as topology-optimized brackets, conformal cooling channels, graded materials, and patient-specific implants. Beyond geometric freedom, AM also contributes to sustainability goals minimizing material waste, reducing dependence on tooling, enabling powder reuse loops, and supporting lightweighting strategies that lower energy consumption during service [

50]. Recent demonstrations range from orthopaedic implants with enhanced biological function to turbine blades with built-in thermal management pathways and aerospace lattice structures optimized for mass-specific stiffness [

27]. Leading publications in Acta Materialia and Progress in Materials Science highlight how AM enables multifunctionality where structural load capacity, thermal behaviour, wear resistance, and even biological compatibility can be integrated within a single, monolithic component [

35]. Yet, despite meaningful progress, the path to widespread adoption especially for mission-critical components remains hindered by defect formation. Rapid thermal cycles introduce shrinkage, distortion, and dimensional inconsistency [

41]. Porosity caused by keyhole instability, gas entrapment, or lack-of-fusion negatively impacts fatigue resistance and fracture reliability in LPBF-processed alloys [

12]. Steep thermal gradients create residual stresses that may drive cracking, delamination, or warping [

31]. These defect–microstructure interactions add uncertainty into qualification and certification pathways, making it challenging to guarantee consistent performance at scale [

13]. To respond, industry and research communities have advanced a wide spectrum of mitigation approaches—from controlled scanning strategies and gas-flow tuning to post-processing treatments such as annealing and Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) [

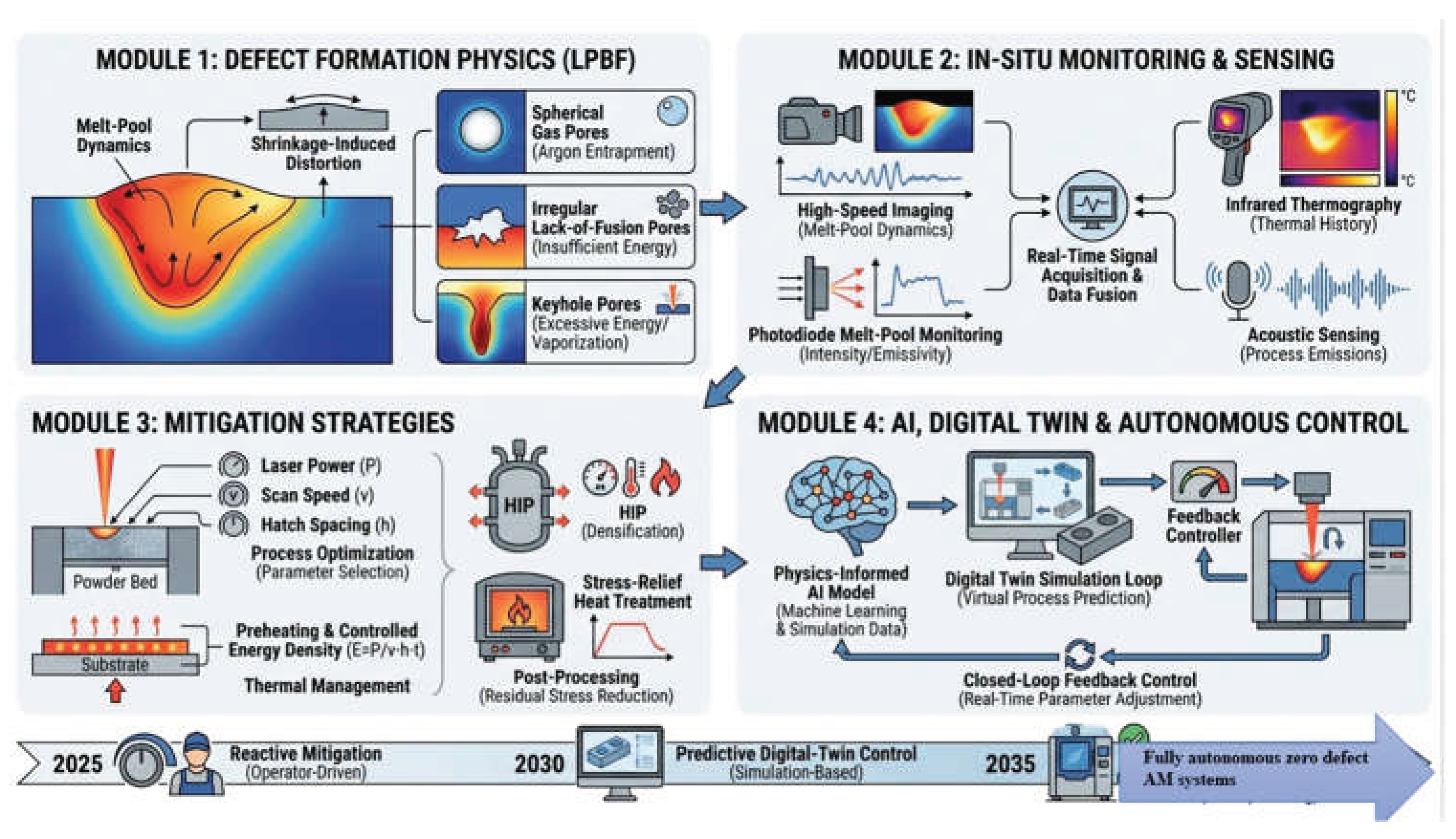

14]. The rise of high-speed sensing, melt-pool monitoring, and optical imaging now allows defects to be observed as they form, laying the foundation for closed-loop control [

30]. Meanwhile, machine learning models, digital twins, and adaptive process intelligence are shaping the next generation of predictive and autonomous AM systems [

1].

Although several reviews have explored AM defects or digital solutions independently, there remains a noticeable gap in literature that brings these perspectives together in a unified, practical, and application-driven way. This work uniquely consolidates:

the underlying physics of shrinkage and porosity formation,

the evolution of process- and post-process mitigation strategies,

the growing role of real-time sensing and closed-loop control, and

the emerging influence of AI-driven prediction, digital twins, and adaptive optimization.

Beyond defect science, this review also discusses sustainability considerations, certification pathways, inspection challenges, and industrial readiness factors that ultimately determine whether AM components reach commercial deployment. By connecting physical metallurgy, monitoring technologies, and data-driven manufacturing intelligence, this review offers a holistic roadmap toward defect-resilient and certifiable metal AM for aerospace, biomedical, and energy applications.

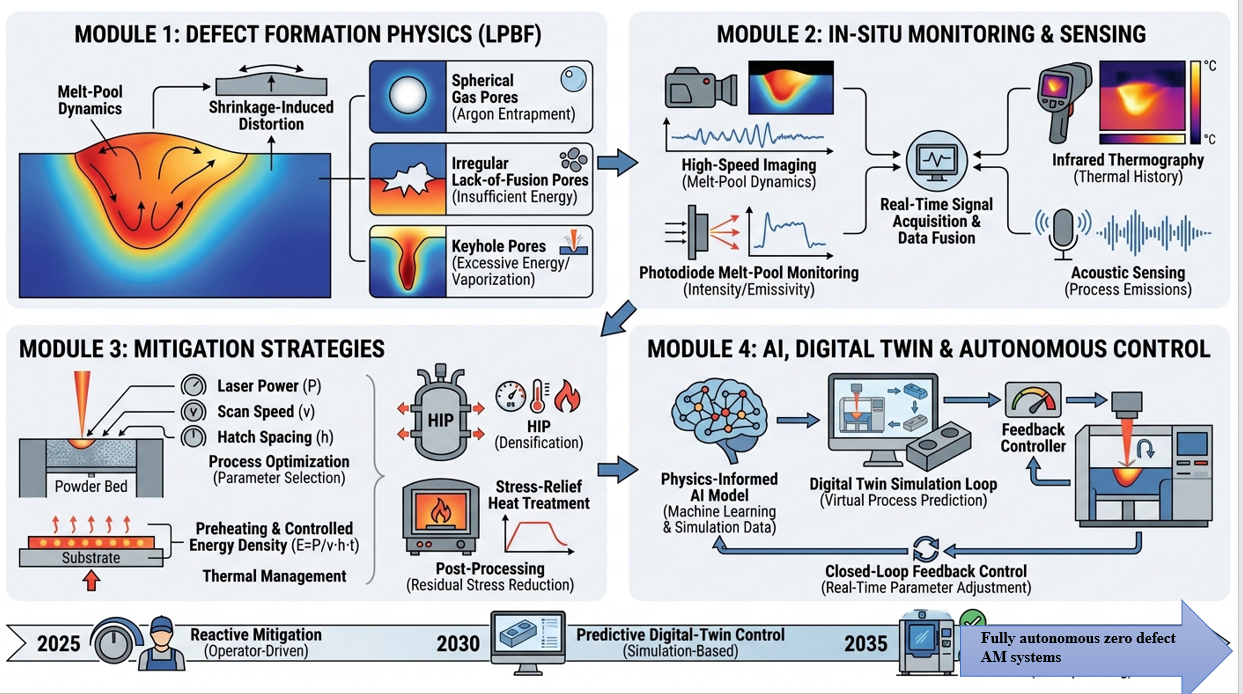

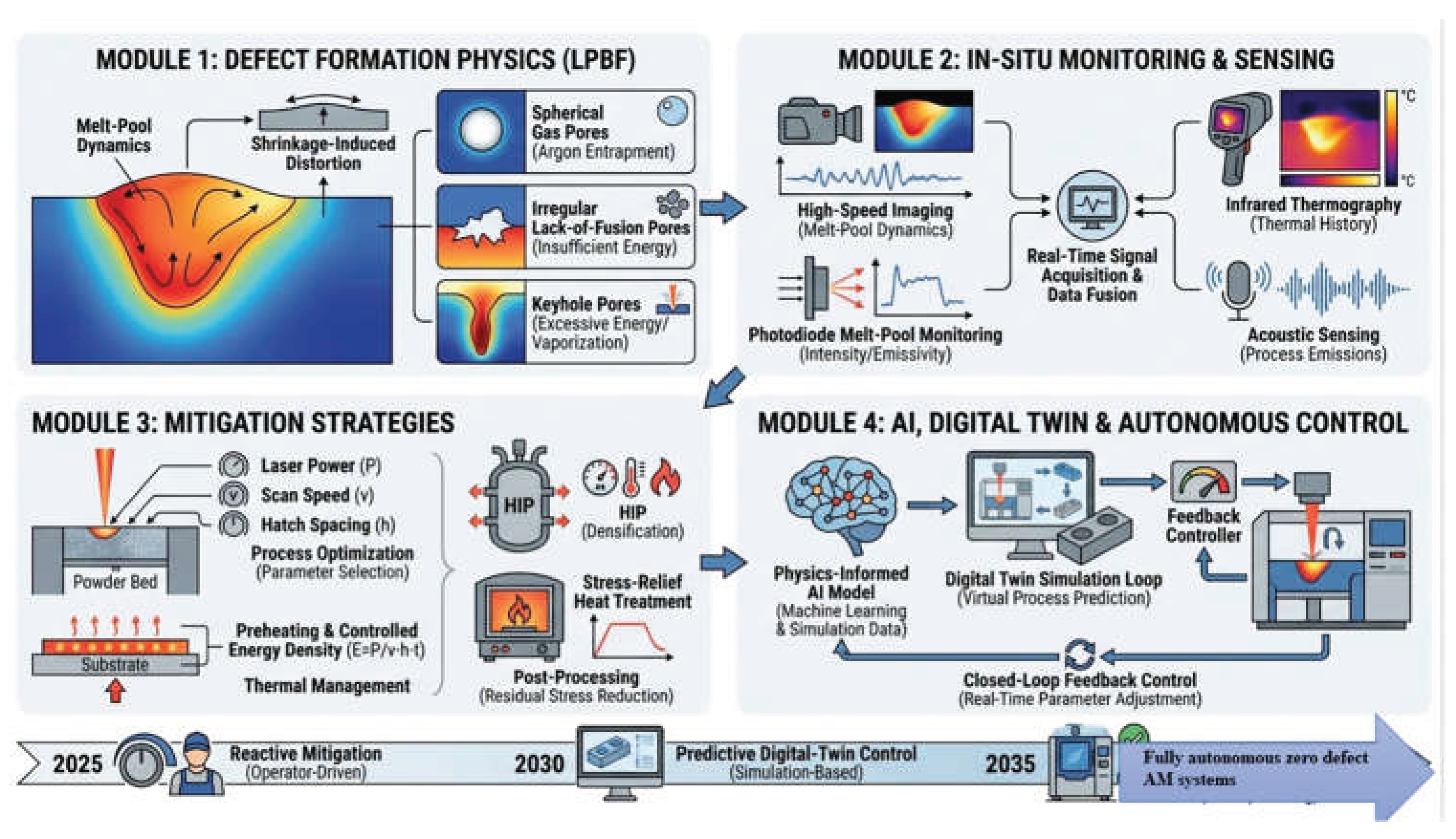

Figure 1 illustrates an ontology-based AM process map that contextualizes these developments across the interconnected workflow stages of design, processing, monitoring, and qualification.

2. Overview of Metal Additive Manufacturing Technologies

Metal AM encompasses a range of technologies; each suited to specific applications and materials. Among the most widely used are:

2.1. Selective Laser Melting (SLM) and Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS)

Selective Laser Melting (SLM) and Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) are widely used Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) techniques that employ a high-power laser to selectively melt and consolidate fine metal powders within a controlled inert atmosphere [

7,

22]. This precision-based, layer-by-layer fabrication approach enables the production of complex internal channels, lattice architectures, and near-net-shape geometries that are extremely difficult to achieve using conventional subtractive or casting-based processes [

10,

47]. In the aerospace sector, SLM/DMLS has been successfully utilized to manufacture topology-optimized turbine blades, lightweight structural brackets, and heat-exchanger components, offering exceptional strength-to-weight performance [

9]. Meanwhile, in biomedical engineering, SLM is routinely used to produce patient-specific Ti-6Al-4V implants with controlled porosity to promote osseointegration and enhance tissue regeneration [

22]. SLM-processed titanium alloys often exhibit yield strengths approaching 1,000 MPa and ultimate tensile strengths exceeding 1,080 MPa, values that are comparable to or even surpass the properties of wrought and forged counterparts [

27,

35]. However, the inherent physics of the process introduces several challenges. Rapid thermal cycling and directional solidification lead to anisotropic mechanical behaviour, residual stress accumulation, and porosity formation, all of which influence dimensional accuracy and fatigue performance [

12,

29,

32]. To address these limitations, multiple mitigation strategies have been adopted. Build-plate preheating helps minimize thermal gradients; optimized scan strategies, such as island scanning and 45° rotation, promote more uniform heat distribution; and in-situ monitoring systems enable real-time detection of melt-pool instability and pore formation [

11,

28,

33]. Furthermore, post-processing treatments such as Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) and tailored heat-treatment schedules effectively remove internal voids, relieve residual stresses, and significantly enhance long-term mechanical reliability [

8,

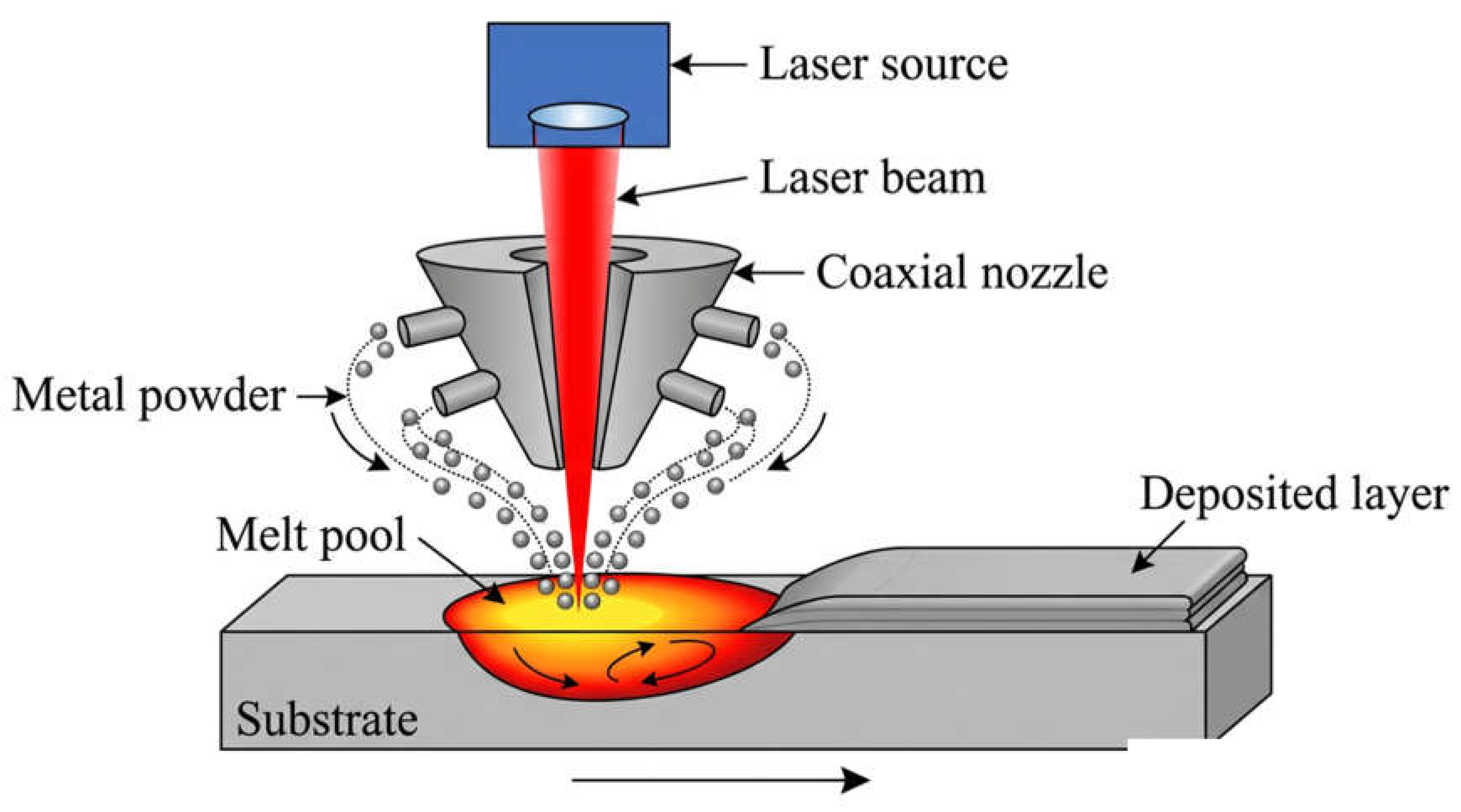

29]. By combining design freedom, high material efficiency, and robust mitigation and post-processing workflows, PBF technologies such as SLM and DMLS continue to enable the consistent production of high-performance components for aerospace, biomedical, and industrial applications. A schematic of the Laser Metal Deposition (LMD) process is shown in

Figure 2 to illustrate the broader context of laser-based AM [

43].

2.2. Electron Beam Melting (EBM)

Electron Beam Melting (EBM) is a high-energy metal additive manufacturing technique that operates in a high-vacuum environment, where a focused beam of accelerated electrons selectively melts successive layers of metallic powder [

29]. Compared with laser-based Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) processes, EBM provides deeper thermal penetration, broader melt-pool stability, and more uniform heat distribution due to the significantly higher energy density of the electron beam [

35]. The vacuum chamber also minimizes oxidation and prevents contamination, making EBM particularly well-suited for reactive alloys such as Ti-6Al-4V and Inconel 718, which are prone to oxygen pickup and defect formation under atmospheric conditions [

22,

27]. EBM has gained substantial traction in the aerospace industry, where components must withstand extreme thermal and mechanical stresses. The process enables the production of near-net-shape turbine blades, engine brackets, and thermal shielding structures with high relative density and robust metallurgical integrity [

9,

22]. Notably, EBM-built parts typically exhibit lower residual stresses and fewer internal inclusions due to the elevated preheating of the powder bed and the homogeneous thermal profile, offering advantages over SLM in applications where dimensional stability is critical [

29,

31]. In the biomedical domain, EBM is widely used for fabricating patient-specific orthopedic and dental implants. Its ability to produce controlled, open-porous architectures facilitates osseointegration and enhances bone ingrowth, resulting in improved long-term fixation and biological performance [

22]. Titanium implants manufactured via EBM consistently demonstrate excellent mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility, reinforcing their suitability for femoral stems, spinal cages, and cranio-maxillofacial implants [

27]. Although EBM systems involve higher initial investment and offer a moderate build rate compared with laser-based methods, their ability to deliver superior metallurgical quality, microstructural homogeneity, and exceptional material cleanliness continues to make EBM an attractive option for aerospace, defense, and medical applications where part performance and reliability are paramount [

29,

35].

2.3. Directed Energy Deposition (DED)

Directed Energy Deposition (DED) is an advanced metal additive manufacturing process in which material typically in the form of powder or wire is delivered into a melt pool created by a focused energy source such as a high-power laser, electron beam, or plasma arc [

21,

43]. The feedstock is continuously supplied and melted as it is deposited, enabling the formation of new structures or the repair of existing components in a layer-by-layer fashion [

9,

21]. Owing to its open architecture and directed material delivery, DED is uniquely suited for repairing high-value parts, adding features to existing components, and fabricating large-scale structures that exceed the build-volume limitations of Powder Bed Fusion systems [

43]. A major strength of the DED process is its exceptional material flexibility. Unlike closed powder-bed platforms, DED allows the use of multiple feedstock types and supports the creation of compositionally graded materials, enabling tailored performance in different regions of the same component [

22,

43]. This capability is particularly valuable in aerospace and energy applications where components operate under highly localized mechanical and thermal demands [

9,

22]. For example, sections of a turbine blade subjected to sustained creep may be reinforced with heat-resistant alloys, while regions exposed to rapid thermal cycling can incorporate materials optimized for thermal conductivity all within a single build sequence [

43]. Such site-specific material tailoring represents one of the most powerful advantages of DED compared with other AM processes. Despite its versatility, DED inherently produces larger melt pools and experiences higher thermal gradients than Powder Bed Fusion, which can compromise dimensional accuracy, surface finish, and geometric precision [

35,

41]. These characteristics often necessitate post-processing such as CNC machining, heat treatment, or Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) to achieve final mechanical stability and tolerance [

29,

49]. Additionally, the freeform nature of the process demands precise control of deposition parameters, including energy input, feed rate, and scanning strategy, to reduce defects such as porosity, dilution, and microstructural inhomogeneity [

29,

41]. Nevertheless, DED remains a powerful and strategic AM technology particularly in applications where repairability, feature addition, multi-material capability, and large-component fabrication are critical operational requirements [

9,

43]. Its ability to refurbish damaged aerospace components, extend tooling life, and produce functionally graded structures continues to solidify DED as a vital enabling process within the broader additive manufacturing ecosystem [

21,

43] Comparative Analysis of Energy Sources, Processing Conditions, and Applications Across Metal AM Technologies is illustrated in

Table 1

Metal additive manufacturing (AM) offers a range of transformative advantages that have been increasingly documented in recent literature, including findings reported in Acta Materialia (2023). Foremost among these is its exceptional design freedom, enabling the creation of intricate lattice structures, conformal cooling channels, and organic load-bearing topologies that are unattainable through conventional casting or subtractive methods. This capability has accelerated innovations in lightweight aerospace systems, patient-specific biomedical implants, and high-efficiency thermal management components. A second key advantage lies in material utilization. By depositing material only where required, metal AM significantly reduces waste an especially critical benefit when working with high-cost alloys such as titanium and nickel-based superalloys while minimizing machining, lowering production costs, and reducing environmental impact. Additionally, AM shortens manufacturing lead times, facilitating rapid transitions from digital design to functional prototypes and enabling on-demand production in sectors that demand fast customization and iterative development. Despite its advantages, several barriers continue to impede widespread industrial adoption. Shrinkage, porosity, and residual stresses remain persistent challenges that influence dimensional accuracy, mechanical properties, and long-term reliability. Moreover, high equipment investment, expensive feedstock powders, post-processing requirements, and the need for specialized expertise contribute to elevated overall production costs. These challenges highlight the ongoing need for advancements in process optimization, in-situ monitoring, and predictive modelling to fully unlock the industrial potential of metal AM.

Metal additive manufacturing encompasses multiple fusion-based processes, each offering distinct advantages and limitations depending on the component's size, complexity, and performance requirements. Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) is widely adopted for parts that demand fine features and high surface quality, particularly small-to-medium components with internal channels or lattice structures. Electron Beam Melting (EBM), which operates under a high-vacuum environment and elevated powder-bed temperatures, is well-suited for reactive alloys such as titanium and supports lower residual stresses due to reduced thermal gradients. In contrast, Directed Energy Deposition (DED) is especially effective for repairing worn components, building large structures, or adding localized features, though secondary machining often remains necessary to meet final dimensional tolerances. Each process presents different defect tendencies and operational considerations. LPBF offers superior resolution but may be more vulnerable to keyhole porosity and shrinkage distortions. EBM minimizes thermal stress but may produce comparatively rough surfaces and is constrained by vacuum-dependent material selection. DED provides flexibility for multi-material transitions and component restoration, yet thermal cycling during deposition can introduce microstructural variations. Understanding these trade-offs enables more informed decision-making when aligning process selection with performance targets, cost expectations, and geometric constraints.

3. Applications in High-Precision Manufacturing

3.1. Aerospace

Metal additive manufacturing (AM) has emerged as a transformative technology within the aerospace sector, where the need for lightweight, high-performance, and thermally efficient components continues to increase. AM is now routinely applied to fabricate turbine blades with embedded cooling channels, fuel nozzles, structural brackets, and other mission-critical components that must endure extreme thermo-mechanical loading. A defining advantage of metal AM for aerospace applications is its ability to consolidate multiple intricate features into a single monolithic structure, eliminating the assemblies, welds, bolts, and machined interfaces typically required in conventional manufacturing. This reduction in part count decreases manufacturing and maintenance burdens, minimizes potential failure points, improves fatigue reliability, and delivers substantial mass savings essential factor for both aviation efficiency and space-launch economics. The design freedom inherent to AM enables the integration of advanced geometries such as lattice reinforcements, conformal cooling passages, and generatively optimized support structures, which are exceedingly difficult or infeasible to produce through subtractive or casting processes. These complex architectures enhance thermal management, aerodynamic performance, and structural efficiency, allowing components to operate under more demanding conditions while lowering fuel consumption and emissions. Collectively, these capabilities position metal AM as a foundational enabler of next-generation aerospace propulsion systems, lightweight airframe architectures, and high-temperature engine components. As illustrated in

Figure 3, GE Aerospace successfully deploys metal additive manufacturing to fabricate lightweight, consolidated Inconel 718 components designed for high-temperature service environments.

3.2. Biomedical

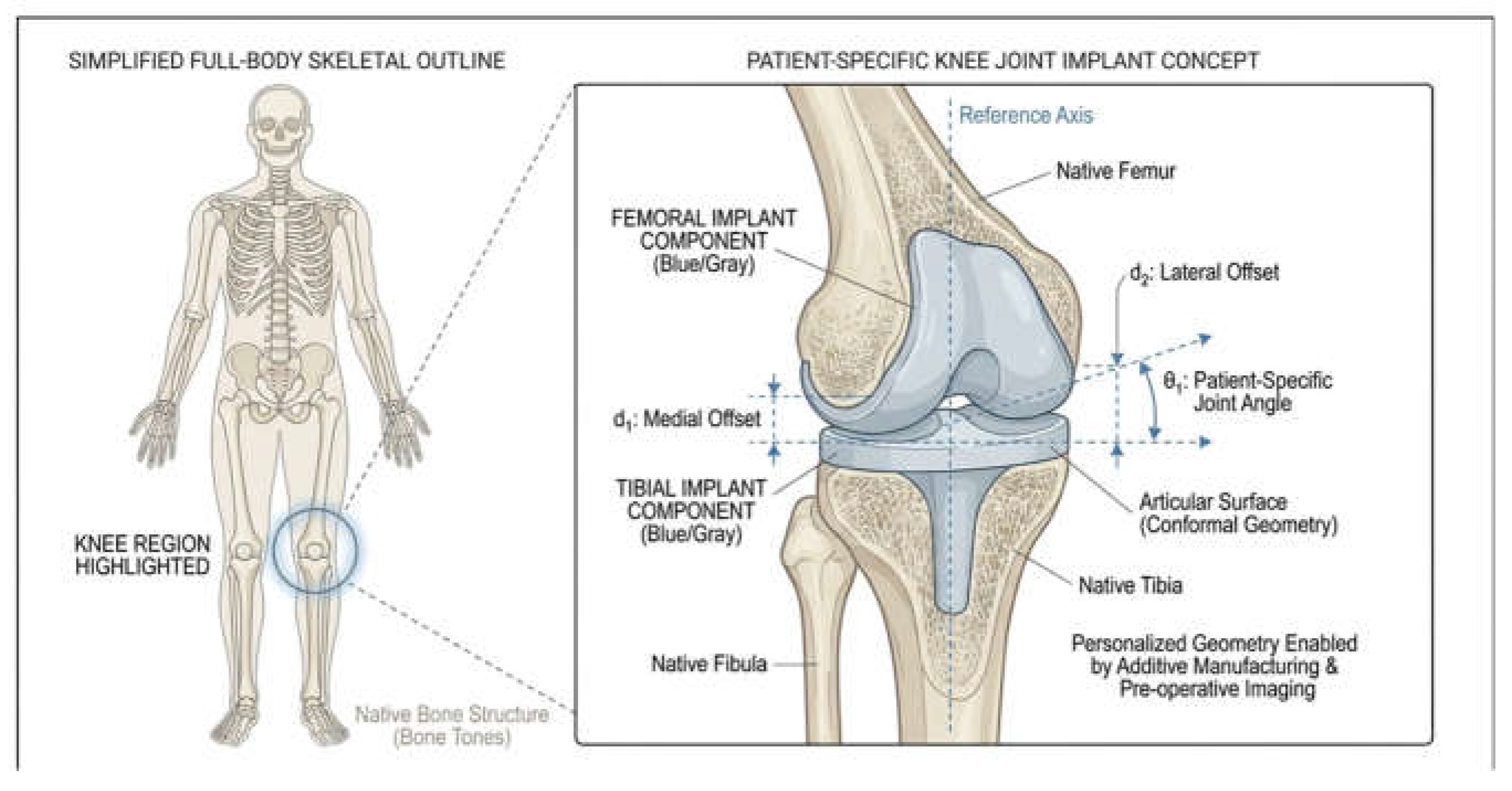

In the biomedical field, metal additive manufacturing (AM) has revolutionized the design and production of patient-specific implants such as hip and knee replacements, cranial plates, spinal cages, maxillofacial structures, and dental prosthetics. Unlike conventional manufacturing which often relies on standardized geometries AM allows implants to be designed directly from patient CT

or MRI data, ensuring a precise anatomical match and improving fit, comfort, and postoperative recovery. Among the various AM techniques, Electron Beam Melting (EBM) has emerged as a leading process for biomedical applications due to its operation in a high-vacuum environment, which minimizes oxidation and produces exceptionally clean, biocompatible surfaces. EBM-fabricated Ti-6Al-4V implants exhibit excellent mechanical strength, controlled porosity, and long-term corrosion resistance, making them ideal for load-bearing orthopaedic applications. A key benefit of AM in the biomedical sector is its ability to engineer porous and lattice architectures that closely mimic natural bone morphology. These structures promote osseointegration the biological bonding of bone to the implant by facilitating vascular growth, nutrient flow, and cell migration. Such engineered porosity also enables fine-tuning of implant stiffness, reducing stress shielding and improving long-term fixation. Additionally, AM enables the integration of multi-functional features such as drug-delivery channels, antimicrobial surface patterns, and gradient porosity for controlled bone ingrowth capabilities that are unattainable with traditional machining or casting. The rapid turnaround time from digital design to final implant also makes AM an invaluable technology for trauma cases, where personalized implants must be manufactured within days. Overall, the combination of patient-specific customization, biological functionality, and superior material properties positions metal AM especially EBM as a disruptive and highly effective manufacturing route for next-generation orthopaedic and dental implants. The potential of metal AM to enable customized anatomical geometries and patient-specific orthopedic solutions is illustrated in

Figure 4, which presents a conceptual 3D-printed knee cap model created for this study.

3.3. Microelectronics

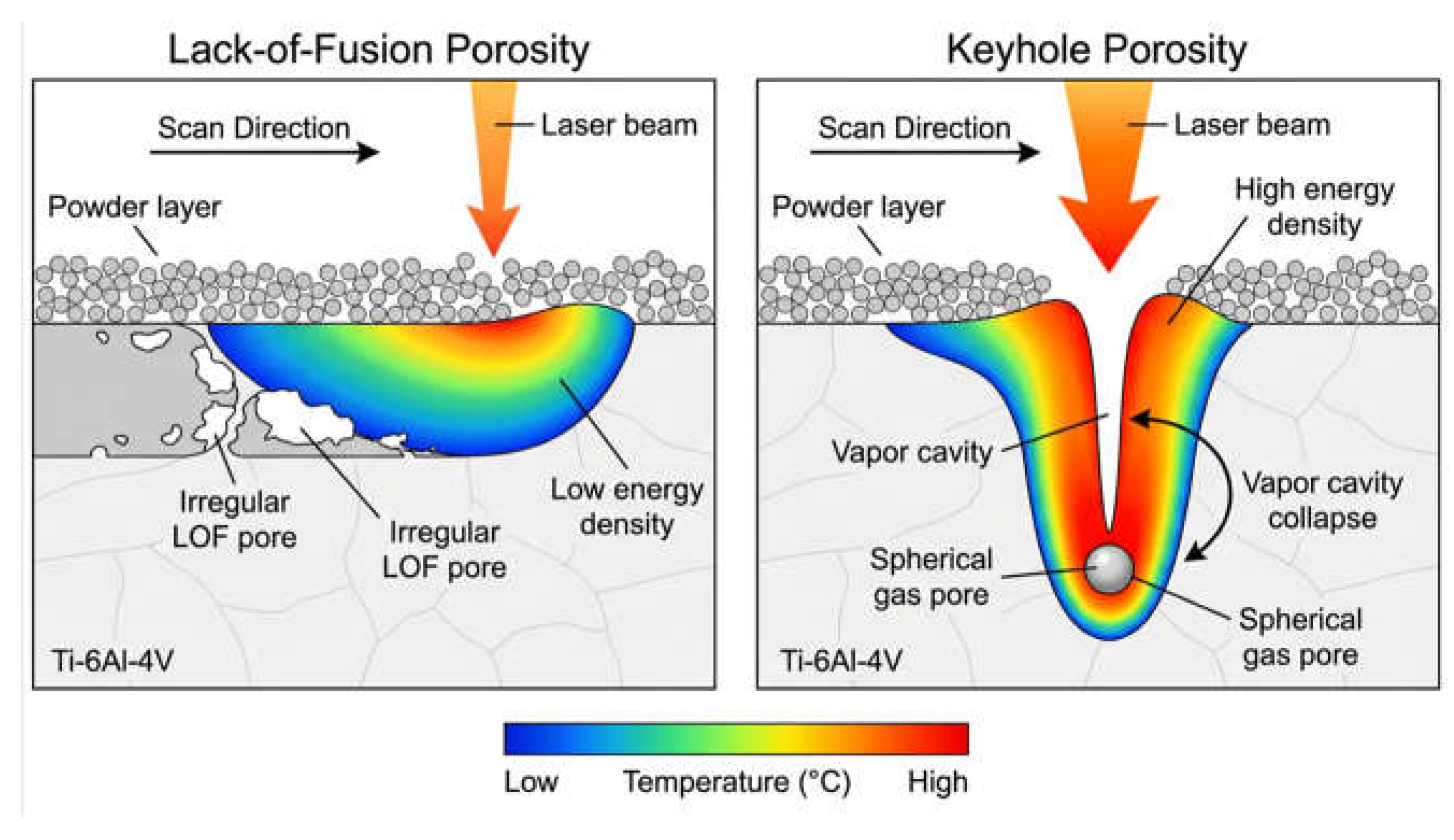

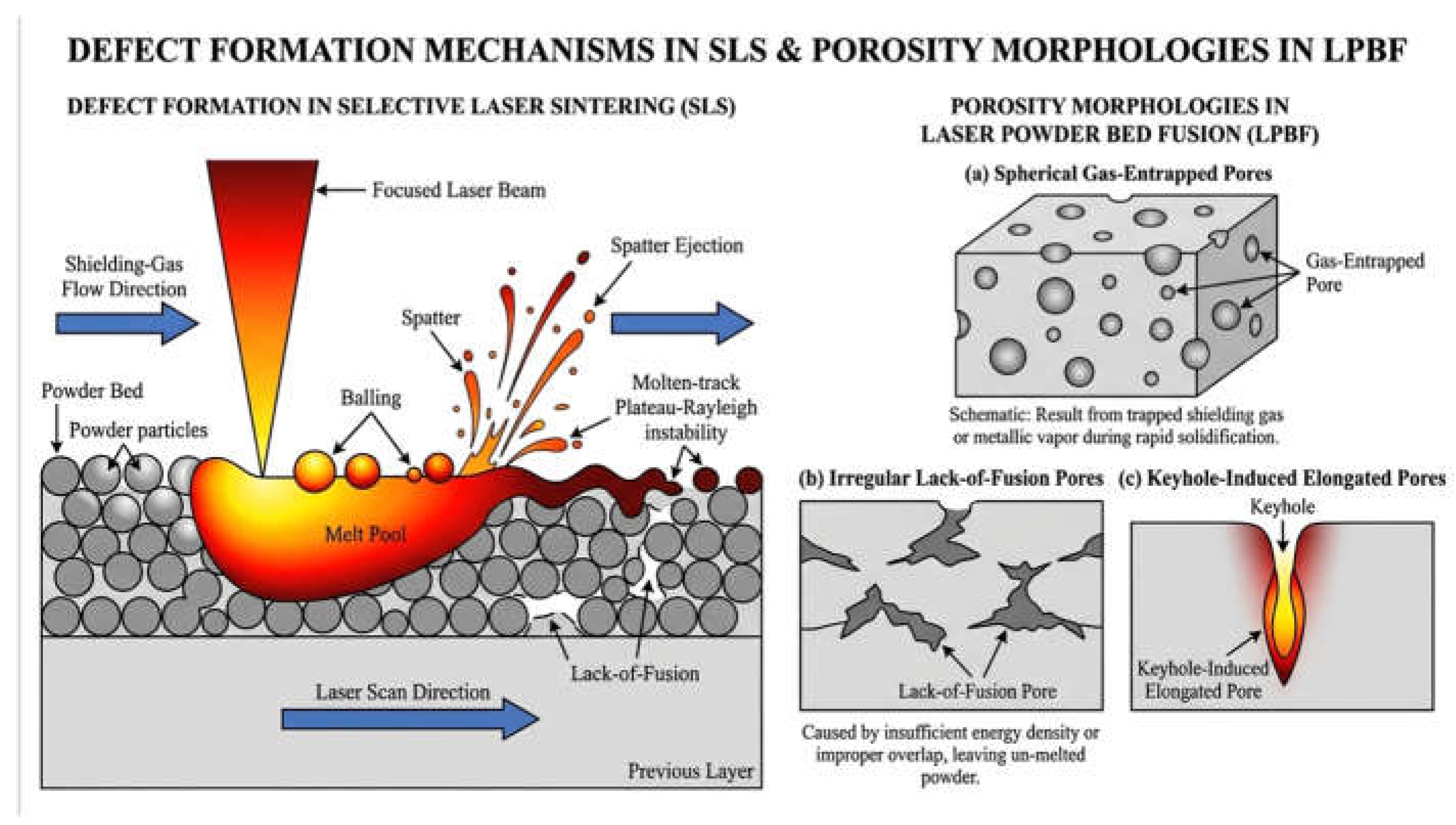

Additive manufacturing (AM) enables the fabrication of miniaturized components such as micro-heat sinks, conductive interconnects, and embedded electronic pathways, which are increasingly required in compact, high-performance microelectronic systems. The layer-wise precision of AM supports intricate geometries and internal channels that are difficult or impossible to achieve with traditional subtractive processes. Moreover, processes such as ultrasonic consolidation (UC) facilitate the integration of fragile foils, sensors, and conductive elements through low-temperature, solid-state bonding, reducing thermal damage and preserving functional material properties an essential advantage when working with polymers, piezoelectric, or advanced semiconductor substrates. Despite these benefits, achieving tight dimensional tolerances remains challenging. Miniaturized AM components often require post-processing operations, such as CNC micro-machining, polishing, or localized laser finishing, to correct deviations caused by shrinkage, porosity, and surface roughness. The two dominant porosity formation mechanisms associated with Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) Lack-of-Fusion and Keyhole-induced gas pores are conceptually illustrated in

Figure 5, demonstrating how inadequate melt-pool overlap or excessive energy input can generate distinct pore morphologies that directly influence mechanical reliability and functional performance in microelectronic applications.

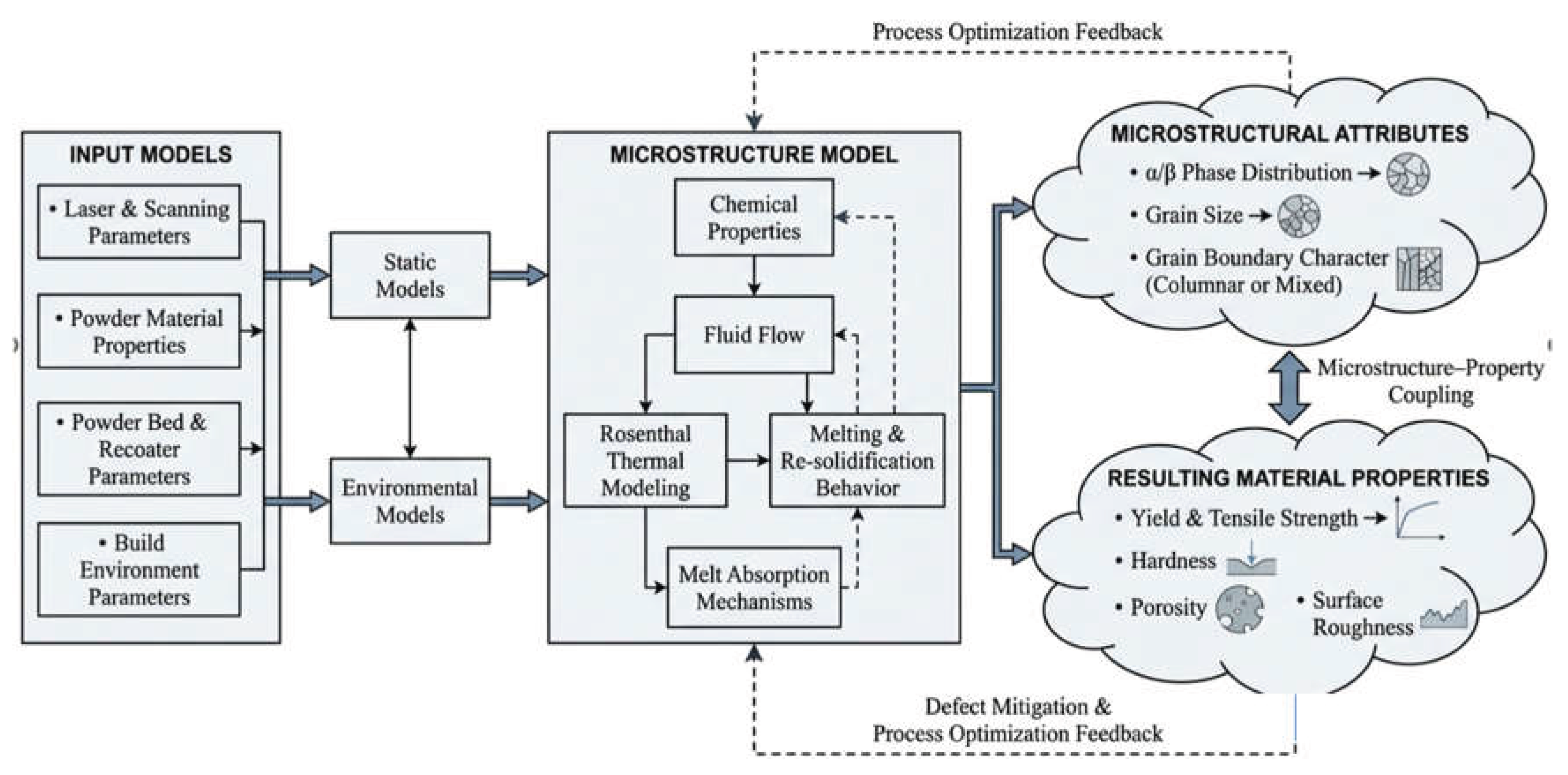

3.4. Physics-Informed AI and Digital Twin Integration

Recent advances in metal additive manufacturing (AM) increasingly emphasize the integration of physics-informed artificial intelligence (AI) and digital-twin technologies to improve process predictability and defect control. In contrast to conventional machine-learning models that rely exclusively on empirical datasets, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) embed governing principles such as heat conduction, melt-pool convection, recoil pressure, and fluid-flow dynamics directly into the learning architecture. By constraining the solution space through physical laws, these models demonstrate improved reliability under sparse-data conditions, parameter drift, and previously unseen geometries, where purely data-driven models may exhibit reduced generalizability. Digital-twin frameworks function as real-time virtual counterparts of the AM process, synchronizing multi-modal in-situ sensor data (e.g., melt-pool thermography, photodiode emissions, acoustic signals, and X-ray imaging) with thermo-mechanical simulations. This enables proactive forecasting of porosity evolution, shrinkage trends, thermal distortion, and melt-pool instability during fabrication. When combined with closed-loop control, emerging systems support automated corrective actions such as energy-density adjustment, scan-path modification, and localized re-melting to suppress defect initiation before it propagates. Although early demonstrations in LPBF of Ti-6Al-4V and IN718 alloys have reported promising improvements in defect prediction accuracy and process stability, these findings are often limited to laboratory environments, controlled geometries, or machine-specific settings. As such, physics-embedded AI and digital-twin frameworks should be viewed as critical enablers toward progressively autonomous and defect-minimizing AM platforms, rather than evidence of fully autonomous production-scale operation at present.

3.5. Multi-Objective Optimization in Defect Mitigation

Defect mitigation in metal AM requires managing competing objectives such as density, mechanical performance, build rate, and energy consumption. The research focus has shifted from single-factor parameter tuning toward multi-objective optimization frameworks that evaluate trade-offs across the full process design space. Evolutionary algorithms (e.g., NSGA-II), particle-swarm optimization, Bayesian optimization, and surrogate machine-learning models are increasingly employed to determine optimal combinations of laser power, scan speed, hatch spacing, layer thickness, and volumetric energy density. These techniques generate Pareto-optimal solutions that reveal process windows capable of achieving >99.5% density while simultaneously reducing residual stress accumulation and minimizing power demand. When coupled with AI-enabled process control systems, multi-objective optimization transitions from static parameter selection to real-time decision-making, improving interlayer bonding, lowering porosity, and enhancing process robustness across different geometries, machines, and powder batches. This holistic optimization paradigm represents a key step toward scalable, repeatable, and production-grade metal AM.\

3.6. Related Work on Machining, Microstructure, and Defect Behavior in LPBF Alloys

Recent research has significantly deepened our understanding of how machining strategies, microstructural features, and defect formation influence the performance of laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) alloys such as Inconel 718 and Ti-6Al-4V. Pereira et al. showed that helical milling can markedly improve hole quality, dimensional accuracy, and surface finish in LPBF Inconel 718, establishing it as a reliable post-processing approach for near-net-shape aerospace components [

88]. Building on this, prestress-assisted machining has emerged as an effective method for enhancing surface integrity and minimizing deformation in thin-walled AM structures, which are particularly prone to distortion during finishing operations [

89]. Microstructural characteristics also play a critical role in shaping the mechanical behavior of AM parts. The influence of crystallographic texture and grain morphology on the fracture toughness of LPBF Inconel 718 has been well documented, with studies showing strong links between build orientation, melt-pool solidification patterns, and the resulting anisotropic fracture response [

90]. From a repair and life-extension perspective, fatigue-life modelling of refurbished components has highlighted how residual defects and stress concentrations can limit long-term durability, underscoring the need for defect-aware repair strategies in industrial AM applications [

91]. Machining behavior remains closely tied to the inherent anisotropy of LPBF materials. Cutting-force analyses have revealed how direction-dependent microstructures influence chip formation, tool loading, and overall machinability in LPBF Inconel 718 [

92]. In parallel, stiffening strategies for near-net-shape components have been proposed to counteract deformation during machining, leading to improved dimensional stability and mechanical reliability in post-processed LPBF parts [

93]. Overall, these studies collectively enrich the broader understanding of how microstructure, machining dynamics, and defect behavior intersect in metal additive manufacturing. They provide an important foundation for the process-optimization and defect-mitigation frameworks discussed throughout this review.

4. Effects of Shrinkage and Porosity on AM Components

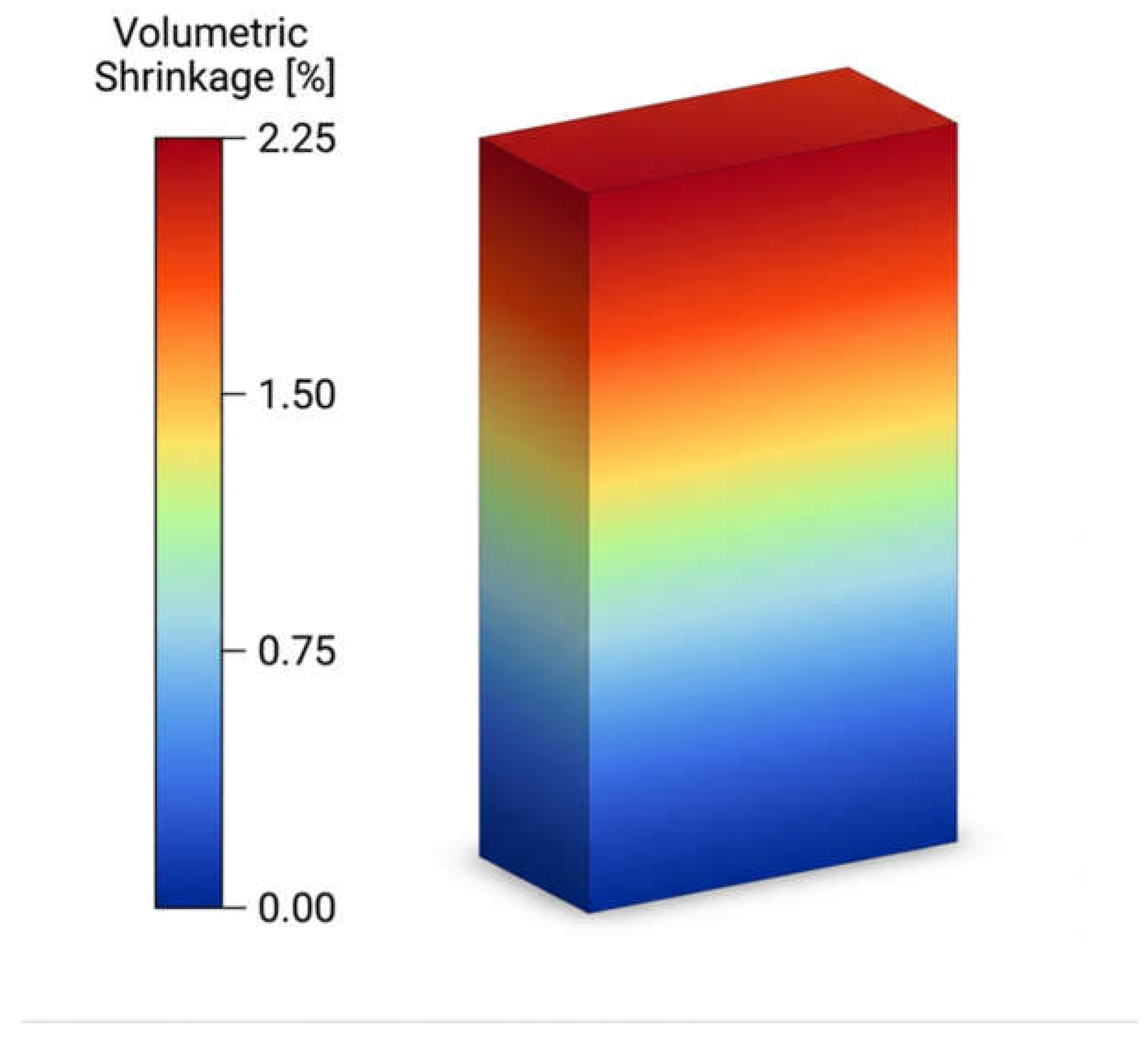

4.1. Shrinkage

Shrinkage in metal additive manufacturing (AM) refers to the dimensional reduction and deformation that occur as molten or semi-solid material cools and solidifies during the layer-by-layer build process. The rapid, cyclic heating and cooling inherent to laser- and electron-beam–based fusion generates steep thermal gradients, resulting in non-uniform contraction across the component. These thermal differentials manifest as distortion, warping, angular deviation, and deviation from the nominal CAD geometry effects that are especially critical in aerospace and biomedical applications where stringent precision and tolerance control are mandatory.

Key shrinkage-related consequences include:

Volumetric Contraction and Dimensional Error Steep thermal gradients induce localized volumetric shrinkage of the melt pool, introducing dimensional inaccuracies and contributing to residual stress buildup.

Solidification-Induced Porosity Incomplete melt-pool overlap or rapid solidification may entrap gases, forming spherical or irregular pores that compromise mechanical integrity.

Dimensional Inaccuracy and Rework Burden Deviation from CAD specification often necessitates extensive machining or redesign to satisfy tolerance requirements.

Residual Stress Accumulation Uneven cooling generates tensile and compressive stress fields that can lead to warping, delamination, or microcracking, as widely reported in recent literature (Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 2024).

Reduced Assembly or Interface Precision Distortion affects alignment in assembly configurations, reducing interlocking accuracy and functional performance.

Strategies to mitigate shrinkage include build-plate preheating, optimized scan-vector sequencing, island scanning strategies, and finite element simulation–based distortion compensation.

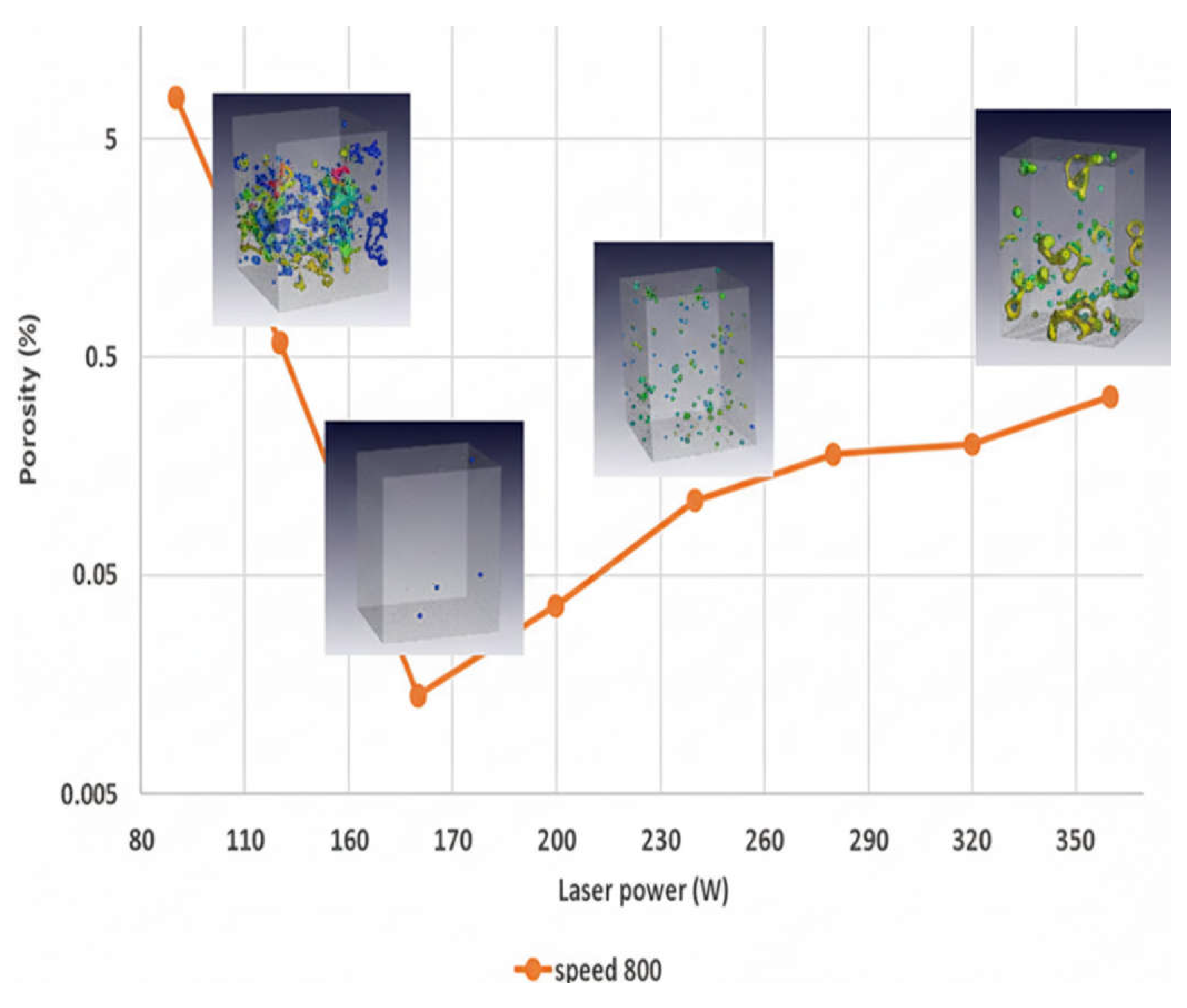

4.2. Porosity

Porosity is among the most critical defect types in metal AM because even small voids can significantly reduce the structural integrity and functional performance of components, particularly those designed to carry high loads or retain pressure. The size and shape of pores vary depending on how they form ranging from nearly spherical gas-entrapped voids to irregular or elongated lack-of-fusion defects, and in some cases interconnected channels that compromise density. Surface-breaking pores present additional concerns, acting as pathways for corrosion, wear, leakage, or fluid permeation in components used for sealing or flow regulation. Mechanically, porosity disrupts the continuity of the material and alters stress distribution. Pores behave as stress concentrators, accelerating crack initiation and reducing fatigue life especially in cyclic or elevated-temperature environments where reliability is paramount. Large or clustered voids further interrupt load transfer across the microstructure, leading to premature plastic deformation or brittle failure modes. In functional applications such as heat exchangers or sealing interfaces, surface-connected porosity can degrade finish quality, affect thermal resistance, and hinder precise dimensional control. Reducing porosity requires stable melt-pool behaviour, consistent powder and atmosphere conditions, and post-processing treatments that eliminate internal voids and improve structural uniformity. Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) and solution heat treatment remain effective approaches for densification and microstructural refinement.

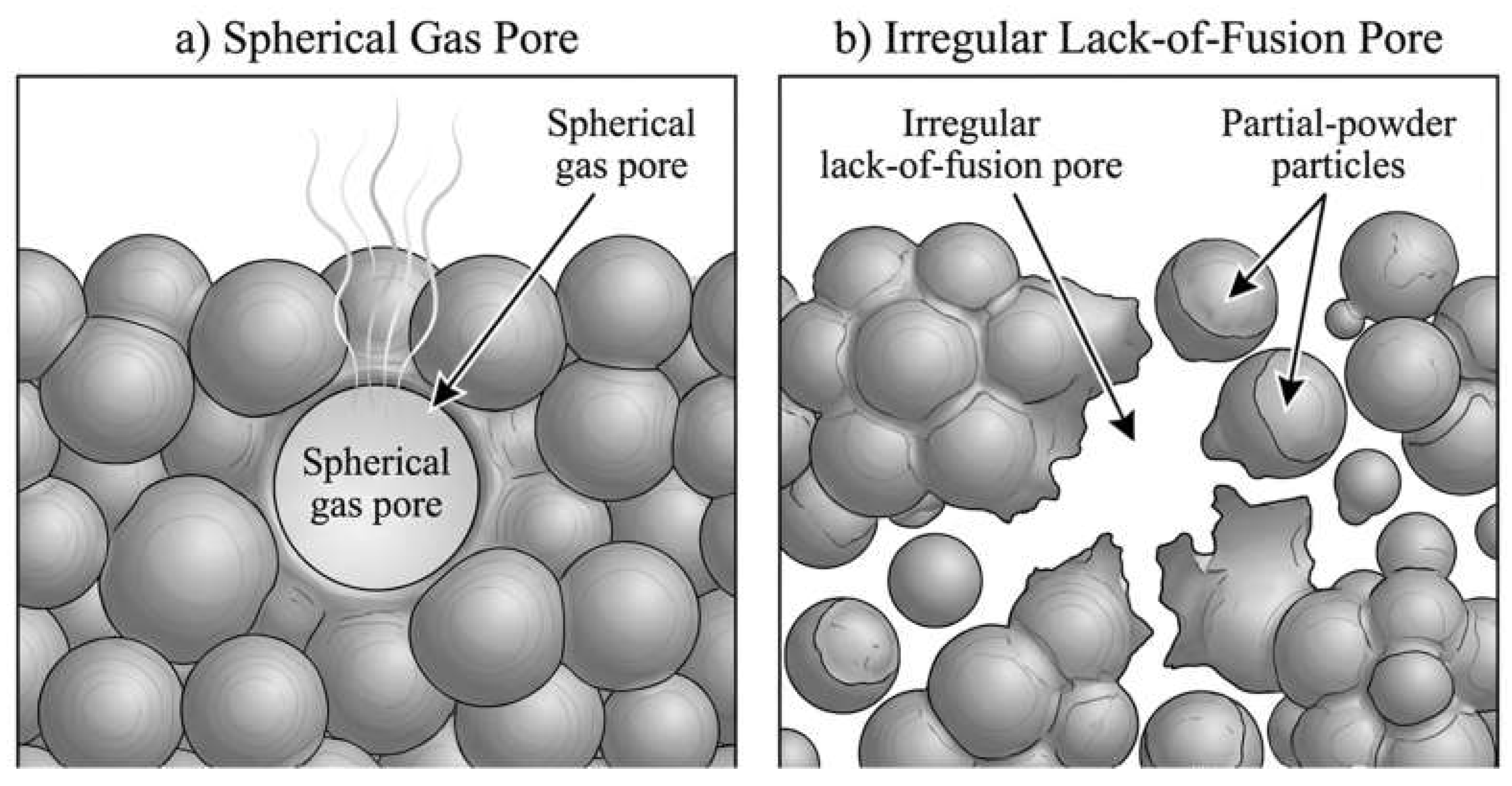

Figure 6 highlights the primary defect-formation routes in powder-based AM systems and shows representative pore morphologies commonly observed in LPBF components.

Figure 7 illustrates the two most commonly observed porosity types in LPBF components spherical gas-induced pores and irregular lack-of-fusion (LOF) pores

. Gas porosity typically results from entrapped shielding gas, incomplete degassing, or gas retained during powder atomization, producing rounded and generally isolated cavities. In contrast, LOF pores originate from insufficient energy input, inadequate melt-pool overlap, or instability during track deposition, leading to elongated or irregular voids that often align along scan boundaries. Because LOF pores act as stress concentrators and are more detrimental to fatigue performance than gas pores, distinguishing between these defect morphologies is critical when diagnosing process stability and implementing effective mitigation strategies.

4.3. Residual Stress in Metal AM

Residual stress is a critical issue in metal additive manufacturing, resulting from steep thermal gradients and layer-wise deposition. These internal stresses can lead to warping, dimensional inaccuracy, and in severe cases, cracking or delamination. According to Wang et al. (2024) in Journal of Materials Processing Technology, thermal mismatch during rapid solidification can induce residual stress levels exceeding 300 MPa in thin-walled components. Strategies to mitigate residual stress include preheating the build platform, optimizing scan strategies, and post-processing heat treatments like stress-relief annealing. FEA models are increasingly used to predict stress accumulation and adjust build orientation to minimize failure risks.

4.4. Cross-Material and Cross-Process Perspectives on Defect Sensitivity

Defect formation and mitigation behaviour varies significantly across alloys and additive manufacturing processes, underscoring the importance of material- and process-specific considerations. Titanium alloys such as Ti-6Al-4V are particularly sensitive to keyhole porosity and residual stress accumulation due to their relatively low thermal conductivity, whereas nickel-based superalloys such as Inconel 718 are more prone to lack-of-fusion defects associated with insufficient energy input and complex solidification behaviour. Aluminium alloys, in contrast, exhibit a higher susceptibility to gas-related porosity, influenced by hydrogen solubility and powder characteristics. Process selection further affects defect sensitivity: Electron Beam Melting benefits from elevated build temperatures and reduced residual stresses but offers lower surface resolution, while Directed Energy Deposition provides flexibility for repair and multi-material deposition at the expense of geometric precision. These differences highlight the limitations of generalized mitigation strategies and emphasize the need for alloy- and process-specific defect models. Emerging manufacturing approaches, including multi-material additive manufacturing, hybrid additive–subtractive systems, and functionally graded structures, further increase complexity by coupling defect formation mechanisms across material interfaces and spatially varying thermal conditions. Future defect-control frameworks must therefore be adaptable across materials, processes, and application requirements.

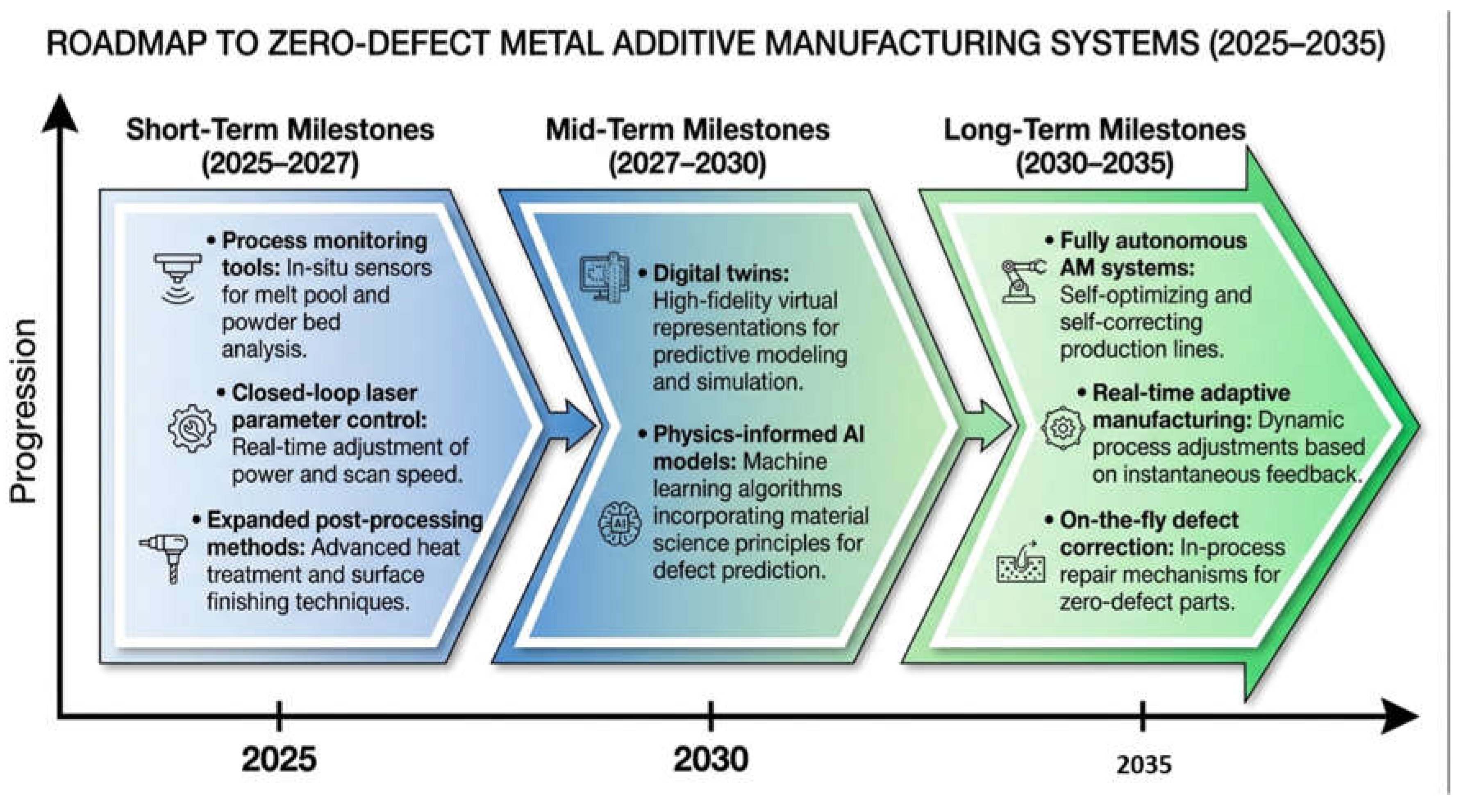

5. Roadmap for Zero-Defect Metal AM Systems

The evolution of metal additive manufacturing (AM) is transitioning from reactive defect mitigation to proactive and predictive defect prevention through intelligent, data-centric process control. A strategic roadmap toward zero-defect metal AM can be delineated across near-, mid-, and long-term horizons:

Short-Term (2025–2027) Broad implementation of in-situ monitoring architectures, including photodiode, thermal, acoustic, and high-speed imaging systems; deployment of closed-loop control for laser power, scan strategy, and energy density; and expanded reliance on post-processing methods such as Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) and precision laser remelting to stabilize microstructure and heal internal voids.

Mid-Term (2027–2030) Integration of digital-twin frameworks and physics-informed AI models capable of real-time prediction of shrinkage, porosity, residual stresses, and melt-pool instabilities. These systems will enable virtual experimentation and process forecasting, reducing design, qualification, and iteration cycles.

Long-Term (2030–2035) Emergence of fully autonomous AM platforms featuring self-learning algorithms, real-time adaptive manufacturing, and on-the-fly defect correction. Future systems may incorporate self-healing strategies, multi-modal sensing fusion, and cross-machine knowledge transfer to enable factory-scale interoperability.

This roadmap is consistent with broader Industry 4.0 initiatives and positions metal AM as a foundational pillar of next-generation digital manufacturing ecosystems shaping future production environments with traceability, repeatability, and certification-ready quality assurance by design. A projected development pathway toward zero-defect metal AM is outlined in

Figure 8, highlighting short-, mid-, and long-term milestones from real-time monitoring to fully autonomous adaptive systems.

5.1. Conceptual Frameworks and Emerging Paradigms in Defect Control

Building on existing process maps and defect classifications, there is a clear need for integrated frameworks that explicitly link defect formation to component-level performance. In such a framework, defect initiation mechanisms such as lack-of-fusion, keyholing, and gas entrapment directly influence microstructural features including grain morphology, crystallographic texture, and pore distribution. These microstructural characteristics, in turn, govern local mechanical properties such as fatigue resistance, fracture toughness, and residual stress sensitivity, ultimately determining component performance, reliability, and certification risk. Making these relationships explicit supports a more systematic approach to defect mitigation that extends beyond parameter optimization toward performance-driven process design. Within this context, defects may be classified according to their relative controllability, considering factors such as detectability during processing, effectiveness of mitigation strategies, and sensitivity of mechanical performance. For example, spherical gas pores are generally easier to detect and mitigate through post-processing techniques such as HIP, whereas lack-of-fusion defects are more difficult to identify in situ and tend to have a disproportionate impact on fatigue life. Such a classification can assist in prioritizing mitigation strategies and allocating process-control resources more effectively. At the same time, emerging physics-informed artificial intelligence approaches are beginning to shift the focus from purely eliminating defects toward selectively managing microstructural heterogeneity. In this paradigm, controlled porosity or spatially tailored microstructures may be intentionally introduced to achieve specific functional outcomes, such as improved osseointegration, energy absorption, or thermal performance, provided that their effects are predictable and well understood.

6. Sustainability Considerations in Defect Mitigation

Defect mitigation in metal AM is not only a performance and reliability challenge but also a critical sustainability consideration. While post-processing techniques such as Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) and laser remelting substantially improve density and mechanical integrity, they impose high thermal and energy demands, increasing both operational cost and carbon footprint. Recent lifecycle assessment (LCA) studies indicate that optimizing build parameters to reduce porosity at the source can lower energy consumption per usable component by up to 30%, particularly when reducing post-processing reliance and part rejection rates. Sustainability-driven defect mitigation extends beyond energy usage. Powder recycling, intelligent scan-path planning, and defect-aware support strategies contribute to material savings and waste reduction. However, repeated powder reuse influences porosity formation due to progressive changes in particle morphology, oxidation state, and flowability. Studies show that using recycled powder beyond three cycles can significantly increase pore size distribution unless managed through sieving, flow aids, or controlled blending strategies. As AM scales for industrial deployment, future frameworks must treat sustainability as a co-objective alongside mechanical, dimensional, and economic performance. Incorporating metrics such as embodied energy, powder reuse efficiency, and thermal budget into process planning will be central to achieving environmentally responsible, high-throughput metal AM.

Powder reuse plays a significant role in both the sustainability and quality outcomes of metal additive manufacturing. With each reuse cycle, powder feedstock may undergo gradual changes in particle morphology, surface oxidation, and flow characteristics. These variations influence layer-spreading uniformity and melt-pool behaviours, increasing the likelihood of trapped gas, irregular porosity, and deviations in microstructural consistency. To maintain defect control without compromising material efficiency, manufacturers employ structured reuse strategies such as sieving, surface conditioning, controlled blending with virgin powder, and continuous monitoring of particle chemistry and rheology. Establishing clear lifecycle thresholds and data-driven reuse limits supports the dual objectives of reducing waste and achieving repeatable, high-density, dimensionally stable components.

Shrinkage and porosity defects introduce cost implications that extend beyond mechanical performance limitations, influencing production throughput, inspection demands, and post-processing requirements. Corrective actions such as machining, polishing, additional support removal, or Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) increase lead time, energy consumption, and total manufacturing cost when defects are addressed after fabrication. Preventing defect formation through optimized process parameters, predictive simulation, thermal management, and in-situ monitoring is generally more cost-efficient than post-build remediation. Evaluating mitigation strategies from both technical and economic viewpoints enables manufacturers to identify where investment in sensing, modelling, or adaptive control yields measurable gains in first-pass success rate and long-term production sustainability particularly as AM advances toward higher-volume, qualification-critical industrial deployments.

Defects in metal additive manufacturing impose consequences that extend beyond mechanical performance to economic viability and qualification pathways. In aerospace and medical applications, rejection of high-value components due to shrinkage distortion or internal porosity can result in substantial material and processing losses, particularly when defects are identified late in the production chain. Additional costs arise from extended inspection requirements, repeated post-processing steps, and requalification efforts. These factors collectively increase lead time and reduce manufacturing efficiency, reinforcing the importance of early-stage defect prevention over post-build remediation. From a qualification perspective, variability in defect populations complicates certification and reduces confidence in process repeatability. Regulatory frameworks increasingly require traceable links between process conditions, defect thresholds, and mechanical performance. In this context, predictive modelling, in-situ monitoring, and digital build records play a critical role in supporting certification-ready manufacturing. Incorporating defect-aware cost considerations and qualification metrics into process planning is therefore essential for scaling metal additive manufacturing toward reliable, industrial production.

7. Mitigation Strategies for Shrinkage and Porosity

7.1. Shrinkage Mitigation

Shrinkage mitigation in metal AM requires a multilevel approach combining process optimization, predictive modelling, and post-processing. Key strategies include:

Process Parameter Optimization Systematic tuning of laser power, scan speed, layer thickness, and build-plate preheating reduces thermal gradients and enhances dimensional consistency. Establishing a stable “process window” has been shown to significantly minimize shrinkage-induced distortion and improve repeatability across builds.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) for Predictive Compensation Thermo-mechanical FEA is increasingly employed to simulate distortion and identify shrinkage-prone regions before fabrication. This enables the incorporation of geometric pre-compensation within the CAD model, reducing the post-machining burden and improving first-pass yield.

Post-Processing via Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) HIP applies high temperature and pressure under inert conditions to relieve residual stress and densify the microstructure, restoring dimensional stability and reducing defect sensitivity. HIP-treated components have demonstrated near-complete densification and compliance with tight tolerance requirements in aerospace and biomedical applications.

These integrated strategies combining in-process optimization, simulation-based compensation, and advanced post-processing provide a robust pathway for achieving the dimensional accuracy and geometrical stability required for mission-critical metal AM components.

Figure 9 illustrates shrinkage and porosity prediction using FEA-based modelling.

Effective porosity mitigation in metal AM requires coordinated improvements in powder quality, process monitoring, and energy input control. Powder characteristics play a critical role in porosity reduction; high-purity feedstock with narrow particle size distribution and uniform morphology enhances flowability, packing density, and melt-pool consolidation, significantly reducing void initiation during layer deposition. Recent studies have demonstrated that improved powder sphericity and reduced oxygen content correlate directly with lower pore formation and increased part density. In-process monitoring further strengthens build reliability by enabling real-time detection and correction of defect formation. Advanced sensing platforms such as high-speed optical imaging, photodiode-based melt-pool tracking, and thermal infrared monitoring can identify anomalies related to spatter, balling, or instability in the melt pool on a layer-by-layer basis. These systems support timely adjustments within closed-loop architectures, preventing the vertical propagation of defects throughout the build. Optimizing energy input remains a fundamental lever for mitigating porosity. Careful calibration of laser power, scan speed, hatch spacing, and track overlap ensures complete powder melting while minimizing gas entrapment and lack-of-fusion defects. Research has confirmed that maintaining energy density within an optimal processing window (e.g., 39–58 J/mm³ for Ti-6Al-4V) promotes near-full densification while avoiding excessive heat input that can induce keyholing instability and subsurface pore formation. Collectively, advancements in powder quality, intelligent monitoring, and energy-density control have proven essential for producing dense, reliable metal AM components and are consistently recognized across leading additive manufacturing literature.

Figure 10 illustrates the influence of energy input and process parameters on porosity formation.

Table 2 provides a consolidated overview of the most prevalent defects encountered in metal additive manufacturing, along with their underlying causes and commonly adopted mitigation strategies. The effectiveness of each approach is evaluated based on current research across multiple alloys and process conditions. This summary enables readers to quickly identify defect-control pathways and serves as a practical reference for process planning, quality assurance, and future optimization studies.

7. Recent Case Studies

7.1. Aerospace Components

In the aerospace sector, the acceptance threshold for defects is exceedingly low, given the extreme thermal gradients, vibrational loading, and cyclic stresses experienced by components such as turbine blades, combustor liners, propulsion housings, and load-bearing structural elements. Shrinkage-induced dimensional deviations and gas- or lack-of-fusion–driven porosity pose critical risks to fatigue initiation, crack propagation, and catastrophic in-service failure. A 2023 investigation reported in Materials Science and Engineering demonstrated that the combined use of optimized LPBF process parameters—particularly calibrated laser power and scanning speed alongside post-processing Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) substantially reduced porosity in Inconel 718 turbine components. The improvement in internal density correlated directly with measurable gains in tensile strength and fatigue life, enabling compliance with the durability requirements of jet-engine operating environments. Complementary efforts by NASA, published in Journal of Materials Science (2022), utilized finite element thermal-mechanical simulation to quantify shrinkage behaviours in LPBF-manufactured titanium alloys. Adaptive process parameter control, informed by predictive simulation, reduced shrinkage by approximately 20%, improving dimensional stability. Subsequent heat-treatment protocols effectively relieved residual stresses, minimized distortion risk, and reinforced long-term structural integrity for spacecraft architectures.

7.2. Biomedical Implants

In biomedical applications, shrinkage-related geometric deviation and porosity-driven loss of load-bearing capability directly influence implant durability, osseointegration quality, and long-term biocompatibility. Titanium and titanium-based alloys remain preferred owing to their favourable corrosion resistance and bifunctionality; however, internal voids can compromise service performance under dynamic physiological loading. A 2023 study in the Journal of Biomedical Materials Research demonstrated that optimized laser sintering parameters combined with controlled post-build heat treatment reduced porosity in titanium dental implants by nearly 25%, yielding improved mechanical reliability and prolonged clinical service expectancy. Comparable advancements have been realized in patient-specific prosthetics manufactured through Directed Energy Deposition (DED), where optimization of laser power, deposition strategy, and feedstock morphology contributed to superior surface finish, anatomical conformity, and dimensional precision. The application of HIP played a decisive role in eliminating residual microporosity, thereby enhancing fatigue resistance in cyclic load environments. Likewise, research in Selective Laser Melting (SLM) for orthopaedic implants has shown that fine adjustment of hatch spacing, laser power, and build orientation significantly mitigates shrinkage in high-stress regions. Subsequent heat treatment provided further gains in strength, wear resistance, and long-term mechanical stability, supporting the viability of AM components for demanding biomedical service conditions.

7.3. In-Depth Gap Analysis and Critical Evaluation

Although substantial progress has been made in understanding and mitigating defects in metal additive manufacturing, several unresolved inconsistencies and practical limitations remain evident across the literature. One recurring contradiction concerns the effectiveness of Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) in eliminating porosity. While many studies report near-complete closure of gas-induced pores following HIP treatment, others continue to observe residual keyhole-related voids, particularly in geometrically complex regions or thicker sections. These discrepancies can be attributed to differences in pore morphology, local stress states, and thermal histories, which are often not consistently reported or modelled across studies. Similarly, digital-twin and physics-based simulation frameworks frequently demonstrate strong predictive capability under controlled laboratory conditions but show reduced reliability when applied to reused powder, extended build durations, or industrial-scale components where powder degradation, oxidation, and thermal accumulation are insufficiently captured. Methodological limitations also influence reported outcomes. In-situ monitoring techniques, despite their growing sophistication, remain constrained by sensor resolution, optical accessibility, and reliance on surface or layer-averaged signals. As a result, subsurface defect initiation and transient melt-pool instabilities may go undetected. In parallel, many data-driven and AI-based defect prediction models are trained using small datasets derived from laboratory-scale coupons or single-machine platforms, limiting their transferability to different machines, alloys, and production environments. Scalability therefore remains a significant challenge, as models that perform well for simple geometries often struggle when applied to thin walls, overhangs, internal channels, or components with complex thermal histories. Sustainability-oriented practices such as powder reuse introduce further trade-offs, reducing material cost but increasing the risk of defect formation unless reuse cycles are carefully monitored and controlled. Addressing these challenges requires greater standardization in experimental reporting, geometry-aware modelling approaches, and stronger integration of industrial-scale validation.

8. Standards and Certification in Metal AM

The industrial acceptance of metal AM extends beyond technical feasibility to formal compliance and certification. Standards bodies including ASTM International and ISO have established AM-focused frameworks such as ISO/ASTM 52900, addressing terminology, process testing, and design guidelines. In aerospace, standards including NASA-STD-6030 and SAE AMS7000 define qualification pathways for flight-critical parts, while medical applications require compliance with FDA Class III implant regulations. These frameworks ensure traceability, reproducibility, and safety key milestones in transitioning metal AM from prototyping to qualified production.

9. Future Trends in Metal Additive Manufacturing

9.1. Real-Time Monitoring

Rapid advancements in sensor technologies and AI-driven analytics are enabling real-time, layer-wise defect detection during metal AM processes. High-speed imaging, melt-pool photodiode feedback, acoustic emission monitoring, and infrared thermography facilitate early identification of anomalies such as spatter, balling, or melt-pool instability. These capabilities significantly reduce material waste, minimize post-processing requirements, and enhance first-pass yield in mission-critical applications.

9.2. Multi-Material Printing

Next-generation AM platforms are increasingly capable of depositing dissimilar materials or functionally graded alloys in a single build. This allows for spatial tailoring of properties such as conductivity, corrosion resistance, and thermal performance within a unified component. Multi-material printing is projected to play a pivotal role in aerospace thermal systems, electronic packaging, and patient-specific biomedical implants.

9.3. Sustainability and Lifecycle Efficiency

Metal AM inherently supports a resource-efficient production model by using material only where needed. Recent lifecycle assessment studies report 15–30% reductions in energy consumption for titanium components and up to 80% material waste reduction compared to subtractive machining. Additionally, decentralized AM production models enable localized manufacturing and spare-part regeneration, reducing logistics and associated carbon emissions by as much as 40%.

9.4. AI-Driven Design Optimization

Artificial intelligence and computational optimization tools such as generative design and topology optimization are becoming integral to AM design workflows. These systems produce lightweight, structurally efficient architectures while adhering to AM-specific constraints. AI algorithms also enhance predictive modelling, reduce iterative trial-and-error cycles, and accelerate the transition from concept to manufacturable geometry.

9.5. Hybrid Manufacturing Systems

Hybrid manufacturing platforms combine additive deposition with CNC machining or laser finishing in a single machine environment. This enables near-net shaping via AM followed by precision machining to achieve final tolerances and surface finish. Hybridization is rapidly expanding within aerospace, tooling, and high-value repair industries where performance, dimensional integrity, and turnaround time are critical.

9.6. Broader Implications for Manufacturing Systems and Supply Chains

Reliable control of defects has implications that extend beyond individual components to broader manufacturing systems and supply chains. As defect rates decrease and process repeatability improves, metal additive manufacturing becomes increasingly viable for decentralized production and on-demand manufacturing of spare parts. This shift has the potential to reduce inventory requirements, shorten maintenance cycles, and improve supply-chain resilience, particularly in aerospace, defence, and energy sectors. Digital twins and comprehensive build records further support distributed manufacturing by enabling consistent quality across multiple production sites. As defect control evolves from reactive correction to predictive and adaptive management, metal additive manufacturing is positioned to play a more central role in future digital manufacturing ecosystems.

10. Open Research Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite substantial progress, several unresolved challenges continue to limit defect-free, scalable metal additive manufacturing (AM):

Data Scarcity for AI Models: Many AI-driven and physics-informed digital twins depend on small, machine-specific datasets, restricting generalization across alloys, geometries, and build platforms. A lack of standardized, shareable datasets prevents robust transfer learning and model validation across institutions and machine vendors [

75,

82,

87].

Multi-Scale Defect Modelling: Achieving concurrent simulation of grain-scale microstructural evolution, melt-pool dynamics, and macro-scale thermal distortion remains computationally prohibitive. Integrating physics-informed neural networks with surrogate models offers promise but still lacks exhaustive experimental validation for titanium alloy systems [

87].

Real-Time Defect Correction: While high-speed imaging, thermal mapping, and acoustic monitoring now detect pores and instabilities in real time, autonomous defect correction—such as on-the-fly power modulation or layer-specific toolpath redesign—remains limited to prototype demonstrations [

75].

Energy-Intensive Post-Processing: Post-processing methods such as HIP and multi-stage thermal annealing significantly improve density and fatigue resistance but contribute substantial embodied energy. Emerging neural network–guided surface and microstructure optimization may reduce dependence on repeated thermal cycles, machining, and polishing [

82,

86].

Human–Machine Collaboration: As AM transitions toward autonomous production cells, interpretable AI and safe override frameworks will be required to maintain operator situational awareness, certification compliance, and traceable decision logic for aerospace and biomedical qualification [

75,

87].

Future research should prioritize hybrid workflows that couple experimental datasets, physics-informed AI, and predictive simulation within closed-loop architectures, enabling adaptive parameter control and certification-ready defect traceability. These directions are particularly critical for aerospace turbine components, defence-grade structural elements, and patient-specific implants, where mechanical reliability and regulatory qualification demand remain stringent.

11. Challenges in Standardization and Industrial Certification

While metal AM has achieved technical maturity, large-scale industrial adoption remains constrained by fragmented standards and evolving regulatory expectations. Qualification of AM components especially in aerospace and medical sectors requires strict control of process repeatability, defect thresholds, and mechanical reliability. Although organizations such as ASTM, ISO, FAA, and FDA are advancing AM-specific certification frameworks, variability in powder feedstock quality, machine calibration, and environmental conditions introduces significant barriers to universal standardization. Current non-destructive evaluation (NDE) techniques are not consistently capable of detecting sub-surface porosity or microstructural anomalies formed during processing. The integration of AI-enabled predictive quality models and digital twin systems presents an opportunity to improve qualification pathways through real-time defect tracking, automated documentation, and adaptive certification models. Moving forward, standardization must evolve in tandem with digital manufacturing ecosystems to ensure that defect mitigation strategies translate into certifiable, repeatable, and safe component performance.

While recent advances have meaningfully reduced shrinkage and porosity in metal additive manufacturing (AM), transitioning from research-focused builds to repeatable, production-scale manufacturing introduces a different class of challenges. These challenges extend beyond process physics and increasingly relate to cost competitiveness, reliable documentation of quality, and the integration of AI systems in ways that maintain transparency and operator confidence. Sectors such as aerospace, biomedical, and defence are particularly sensitive to these factors, as qualification frameworks demand consistency, traceability, and clear justification for process decisions.

Cost and Production Throughput for AM to become a viable production option, both performance and total manufacturing cost must align with industrial expectations. Expenses associated with energy consumption, process interruptions, support removal, and reliance on post-processing steps such as stress relief or HIP remain influential. Undetected defects that surface late in the workflow often result in rework or scrapped builds, affecting project timelines and return on investment. As sensing technologies evolve, preventing defects during the build rather than repairing them afterward offers a promising path to reduced cost-per-part and improved throughput.

Digital Traceability and Data Retention Industrial users increasingly expect evidence-backed quality, not just performance claims. Retaining process data including machine settings, thermal histories, post-processing treatments, and inspection findings creates a continuous digital record of the part. This “digital thread” supports traceability, enables more efficient audits, and assists in identifying the potential source of a defect when issues arise. The emerging concept of a comprehensive digital build record or “manufacturing passport” reflects a shift toward more transparent and efficient qualification cycles.

Explainable AI and Human Oversight As AI-driven systems become more involved in adjusting machine parameters or advising operators, the ability to understand and justify those decisions becomes essential. While predictive models can improve consistency, black-box outputs may raise concerns when operators or auditors are asked to trust recommendations they cannot easily interpret. Explainable AI frameworks designed to present reasoning alongside results can help maintain operator situational awareness and confidence. This collaborative approach between human expertise and machine intelligence will be crucial as AM moves closer to autonomous manufacturing environments. In summary, managing cost, establishing traceable digital records, and ensuring transparent integration of AI are key enablers for scaling metal AM beyond laboratory environments. Addressing these industrialization considerations alongside ongoing progress in defect mitigation lays the foundation for reliable, certifiable, and factory-ready metal additive manufacturing.

As metal AM continues to move from prototype development into production environments, the ability to verify and document quality becomes just as important as the quality itself. Digital build records allow manufacturers to store and reference essential process information including machine settings, thermal profiles, post-processing treatments, and inspection results creating a continuous trace from raw powder to finished part. This level of traceability supports faster root-cause investigation when defects are identified and helps maintain consistency across different machines, operators, or manufacturing sites. Clear and accessible documentation also aligns with the expectations of regulatory bodies in sectors such as aerospace, medical implants, and energy systems, where component approval requires evidence-backed confidence in reliability and repeatability. In this context, digital recordkeeping frameworks are not merely administrative tools; they represent a central enabler of certifiable and scalable metal AM, allowing organizations to demonstrate process control, streamline qualification cycles, and build trust in additive technologies as they transition into critical applications.

12. Conclusions

Metal additive manufacturing has evolved from a prototyping tool into a viable pathway for producing high-performance components with geometries and functionalities beyond the reach of conventional manufacturing. Despite this progress, shrinkage-induced distortion, porosity formation, and microstructural inconsistency continue to influence long-term reliability and certification readiness. However, advancements in process optimization, thermal and microstructural simulation, in-situ monitoring, and physics-informed machine learning are shifting defect control from trial-and-error remediation toward predictive, adaptive, and data-driven manufacturing. The integration of digital build records, traceability frameworks, and human-interpretable AI further supports qualification, particularly for regulated industries requiring transparent evidence of process stability. Looking ahead, the convergence of predictive modelling, sensor fusion, cost-aware process planning, and closed-loop feedback architectures is poised to enable intelligent and scalable AM ecosystems. Continued research in powder lifecycle management, component-specific process design, and hybrid post-processing will play a central role in achieving autonomous, certifiable, and sustainable production. With these developments, defect mitigation is no longer the limiting barrier but a controllable parameter within a broader vision of industrialized, high-performance metal additive manufacturing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The work is entirely self-funded by the author.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this review are based on previously published journal articles and conference papers, all of which are appropriately cited throughout the manuscript. No original experimental data were generated for this study.

Competing Interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests related to this

Author Contribution

The author conceptualized the review scope, conducted the literature search, analyzed prior studies, developed the technical framework, created the figures, and prepared, reviewed, and finalized the manuscript.

References

- Satterlee, N.; Torresani, E.; Olevsky, E.; et al. Comparison of machine learning methods for automatic classification of porosities in powder-based additive manufactured metal parts. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, 120, 6761–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimpalli, V. K.; Karthik, G.; Janakiram, G.; Nagy, P. B. Monitoring and repair of defects in ultrasonic additive manufacturing. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2020, 108, 1793–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L. P.; Luccitti, A.; Walluk, M. Evaluation of additive friction stir deposition of AISI 316L for repairing surface material loss in AISI 4340. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, 121, 2365–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, A. T.; Yarar, E.; Özer, G.; Bulduk, M. E. Post-process drilling of AlSi10Mg parts by laser powder bed fusion. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 126(5-6), 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campatelli, G.; Contuzzi, N.; Ludovico, A. Powder bed fusion integrated product and process design for additive manufacturing: A systematic approach driven by simulation. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2024, 130(7–8), 5425–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, B. M.; Kumara, S. R. T.; Witherell, P.; et al. Ontology-based process map for metal additive manufacturing. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2021, 30, 8784–8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, J.; Sarangi, H.; Sahoo, S. A review on direct metal laser sintering: Process features and microstructure modeling. Lasers in Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2019, 6(3), 280–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Yao, J.; Du, B.; et al. Effect of shielding gas volume flow on the consistency of microstructure and tensile properties of 316L manufactured by selective laser melting. Metals 2021, 11(2), 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A. H.; et al. Additive manufacturing in the aerospace and automotive industries: Recent trends and role in achieving sustainable development goals. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2023, 14(11), 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepelnjak, T.; et al. Influence of process parameters on the characteristics of additively manufactured parts made from advanced biopolymers. Polymers 2023, 15(3), 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; et al. Tribology property of laser cladding crack free Ni/WC composite coating. Materials Transactions 2013, 54, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A. Effects of process parameters on porosity in laser powder bed fusion revealed by X-ray tomography. Additive Manufacturing 2019, 30, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A.; Yadroitsava, I.; Yadroitsev, I. Effects of defects on mechanical properties in metal additive manufacturing: A review focusing on X-ray tomography insights. Materials & Design 2020, 187, 108385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; He, X.; Li, B.; Shan, Z. An effective shrinkage control method for tooth profile accuracy improvement of micro-injection-molded small-module plastic gears. Polymers 2022, 14(15), 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibihan, J. J.; Abubasha, M. K.; Thakor, N. A method for 3-D printing patient-specific prosthetic arms with high accuracy shape and size. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 25029–25039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargir, M. A.; Phafat, N. G.; Sonkamble, V. A review of artificial knee joint by additive manufacturing technology to study biomechanical characteristics. Advances in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2023, 12, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepelnjak, T.; et al. Influence of process parameters on the characteristics of additively manufactured parts made from advanced biopolymers. Polymers 2023, 15(3), 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; et al. Effect of shielding gas volume flow on the consistency of microstructure and tensile properties of 316L manufactured by selective laser melting. Metals 2021, 11(2), 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, D.; Seyda, V.; Wycisk, E.; Emmelmann, C. Additive manufacturing: Advances and challenges. Acta Materialia 2023, 210, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.; Nouri, A. Microstructural porosity in additive manufacturing: The formation and detection of pores in metal parts fabricated by powder bed fusion. Journal of Advanced Manufacturing and Processing 2019, 1(3), e10021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwoke, C. C.; Mahamood, R. M.; et al. Soft computing-based process optimization in laser metal deposition of Ti-6Al-4V. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, 120, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, W. S. W.; Manam, N. S.; et al. A review of powdered additive manufacturing techniques for Ti-6Al-4V biomedical applications. Powder Technology 2018, 331, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohale, V.; Jawade, S.; Kakandikar, G. Investigation on mechanical behaviour of Inconel 718 manufactured through additive manufacturing. International Journal of Interactive Design and Manufacturing 2023, 17, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Khurana, M. K.; Bala, Y. G. Effect of parameters on quality of IN718 parts using laser additive manufacturing. Materials Science & Technology 2024, 40(8), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A; Yadroitsava, I; Yadroitsev, I. Effects of defects on mechanical properties in metal additive manufacturing: a review focusing on X-ray tomography insights. Mater Des. 2020, 187, 108385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W; He, X; Li, B; Shan, Z. An effective shrinkage control method for tooth profile accuracy improvement of micro-injection-molded small-module plastic gears. Polymers 2022, 14(15), 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, P.; Tan, X.; He, C.; Nai, M. L. S.; Huang, S.; Tor, S. B.; Wei, J. Scanning optical microscopy for porosity quantification of additively manufactured components. Additive Manufacturing 2018, 21, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperovich, G.; Haubrich, J.; Gussone, J.; Requena, G. Correlation between porosity and processing parameters in TiAl6V4 produced by selective laser melting. Materials & Design 2016, 105, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. D.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A. K.; et al. A critical review on additive manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V alloy: Microstructure and mechanical properties. Journal of Materials Research & Technology 2022, 18, 4641–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, W.; Saleheen, K. M.; et al. Research and prospect of on-line monitoring technology for laser additive manufacturing. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 125, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, S. A.; Anderson, A. T.; Rubenchik, A.; King, W. E.; et al. Laser powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing: Physics of complex melt flow. Acta Materialia 2016, 108, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, C.; Leung, A.; et al. Dynamics in laser additive manufacturing. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedlbauer, D.; Scharowsky, T.; et al. Macroscopic simulation and experimental measurement of melt pool characteristics in selective electron beam melting of Ti-6Al-4V. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017, 88, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. A.; Calta, N. P.; et al. Dynamics of pore formation during laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Fezzaa, K.; Cunningham, R. W.; Wen, H.; Carlo, F. D.; Chen, L.; Rollett, A. D.; Sun, T. Real-time monitoring of laser powder bed fusion process using high-speed X-ray imaging and diffraction. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonehara, M.; Kato, C.; Ikeshoji, T. T.; Takeshita, K.; Kyogoku, H. Correlation between surface texture and internal defects in laser powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroy, T.; Wei, H. L.; Zuback, J. S.; et al. Additive manufacturing of metallic components: Process, structure and properties. Progress in Materials Science 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbro, R. Melt pool and keyhole behaviour analysis for deep penetration laser welding. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2010, 43, 445501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GE Additive Helps Build Large Metal 3D Printed Aerospace Part | Additive Manufacturing.

- Wits, W. W.; Carmignato, S.; Zanini, F.; Vaneker, T. H. J. Porosity testing methods for the quality assessment of selective laser melted parts. CIRP Annals 2016, 65, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Cunha, Â.; Silva, M. R.; Osendi, M. I.; Silva, F. S.; Carvalho, Ó. Inconel 718 produced by laser powder bed fusion: Microstructural and mechanical properties. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, 121, 5651–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Gu, D.; Yu, G.; Dai, D.; Chen, H.; Shi, Q. Porosity evolution and its thermodynamic mechanism during selective laser melting of Inconel 718 alloy. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 2017, 116, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierings, A. B.; Schneider, M.; Eggenberger, R. Comparison of density measurement techniques for additive manufactured metallic parts. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2011, 5, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]