Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Rashba Interaction

2.1. The Model

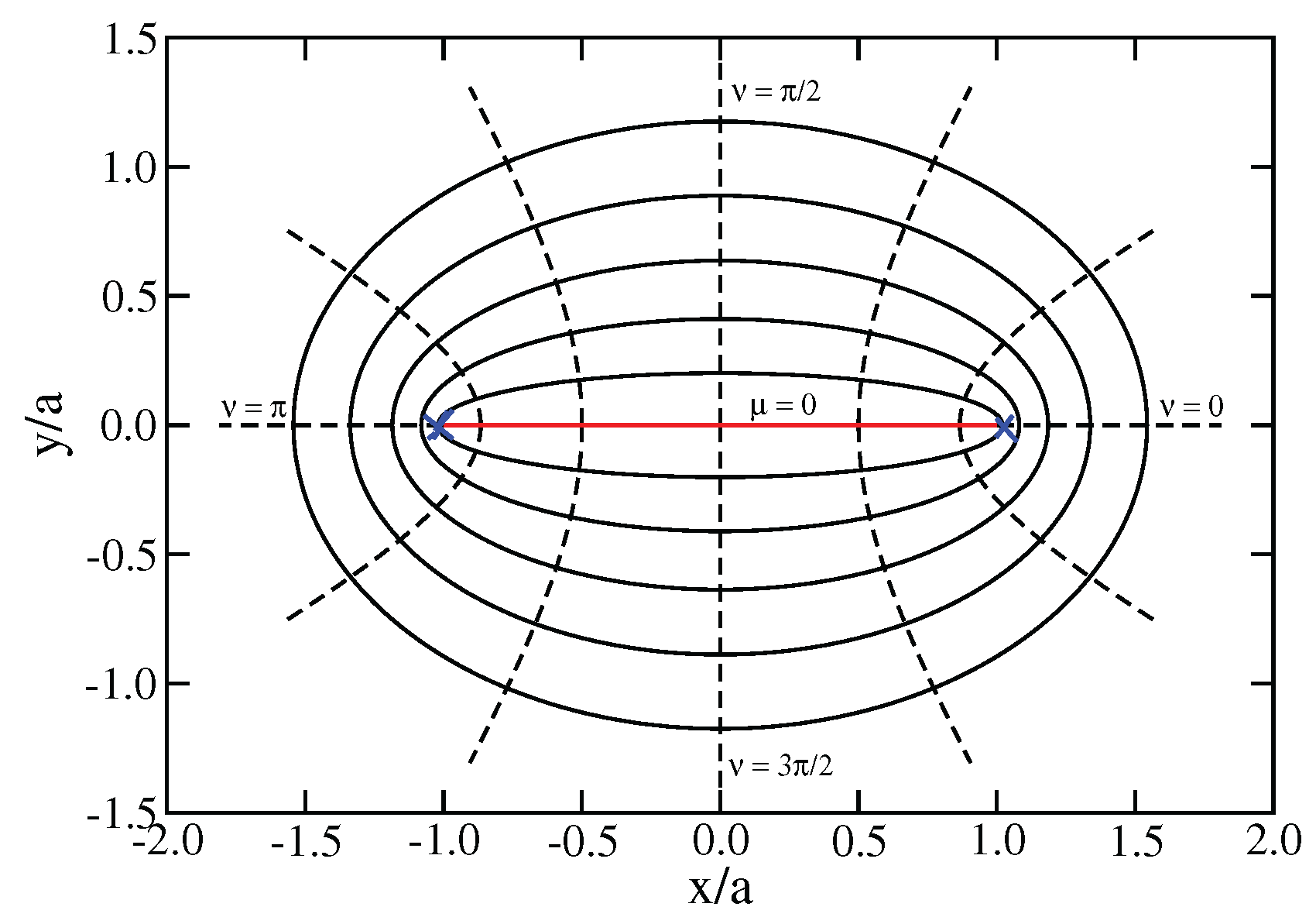

2.2. Elliptic Coordinates

2.3. BdG Equations in Elliptic Coordinates

2.4. Majorana State

3. Results

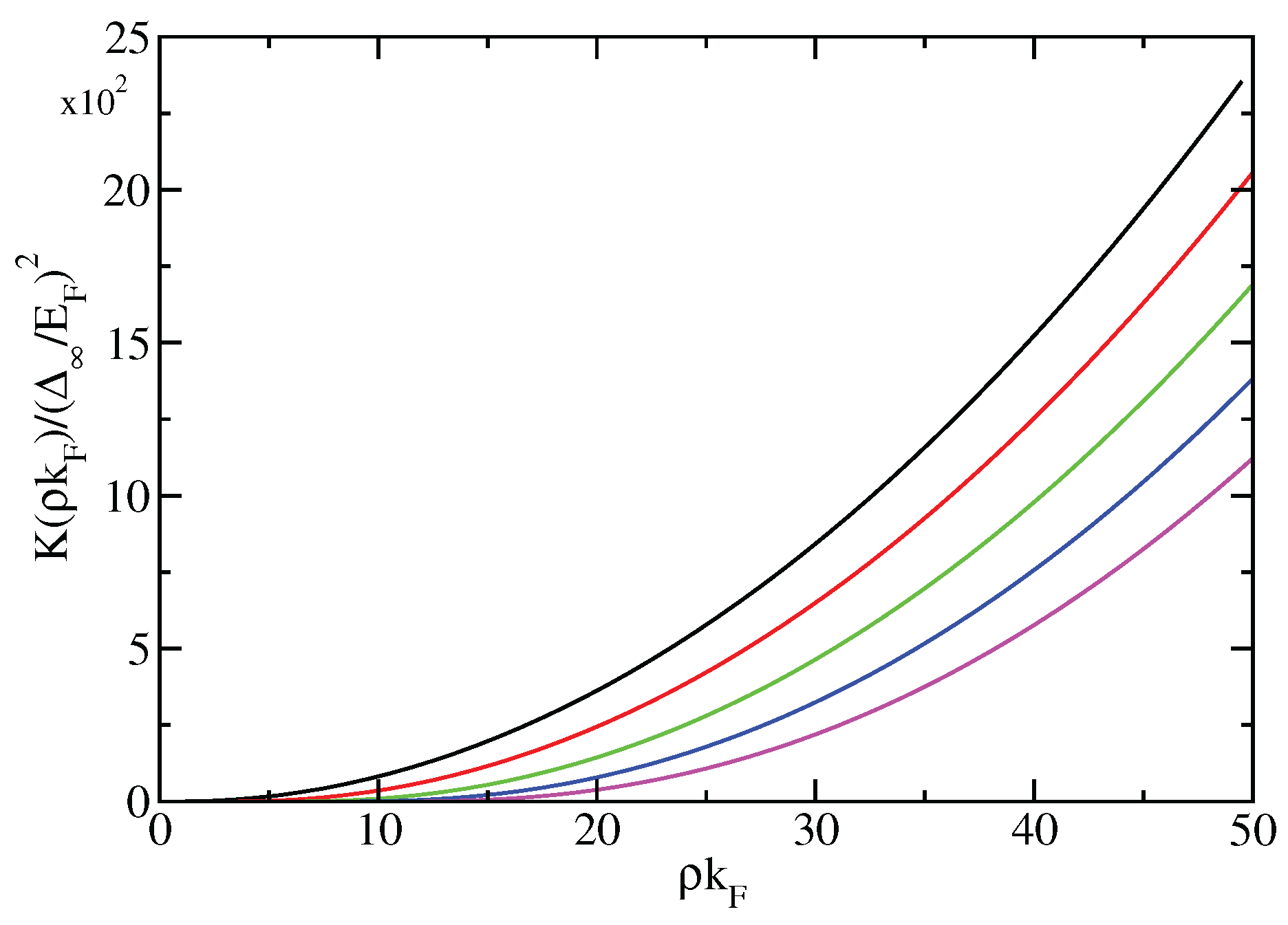

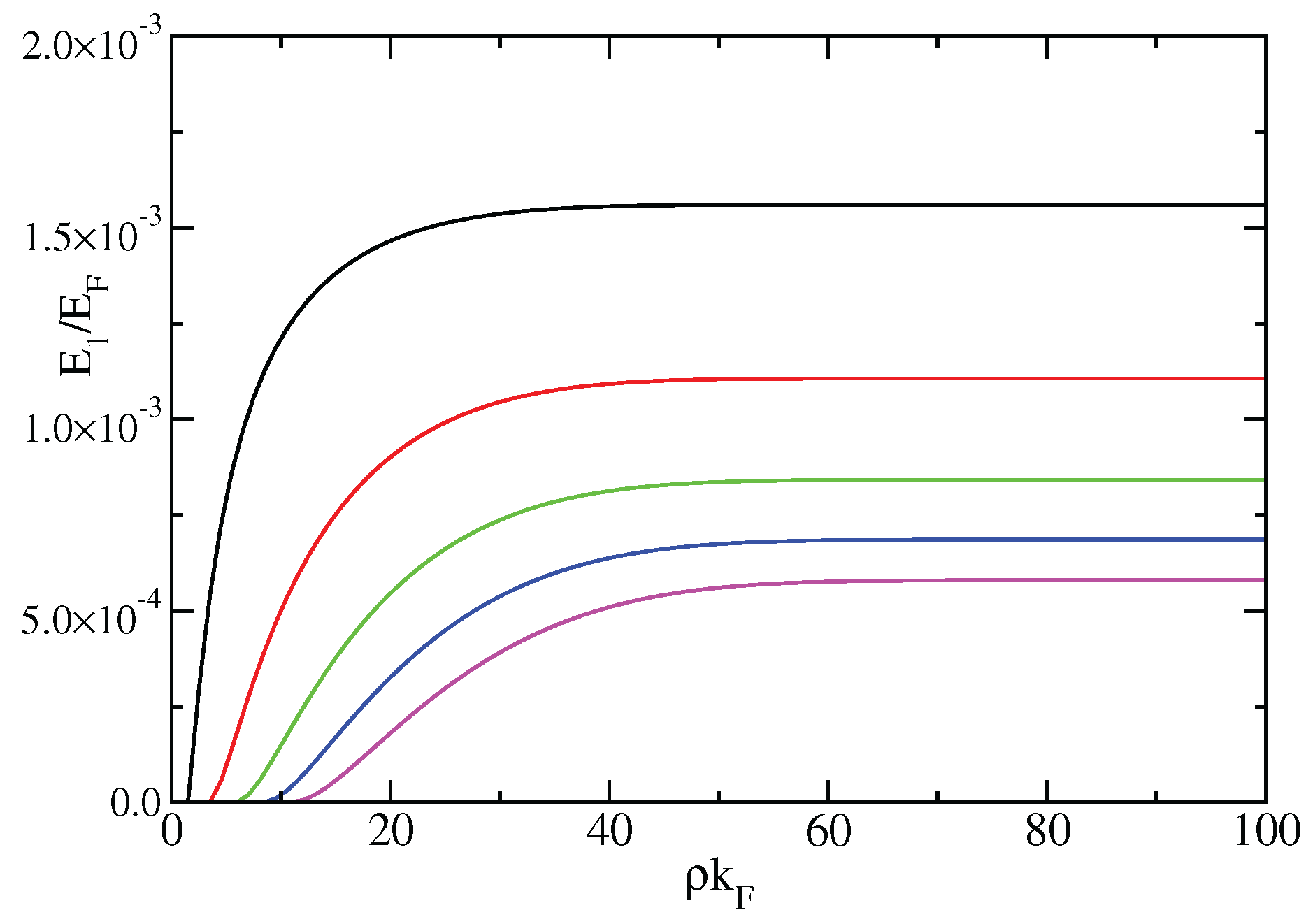

3.1. Excitation Energies

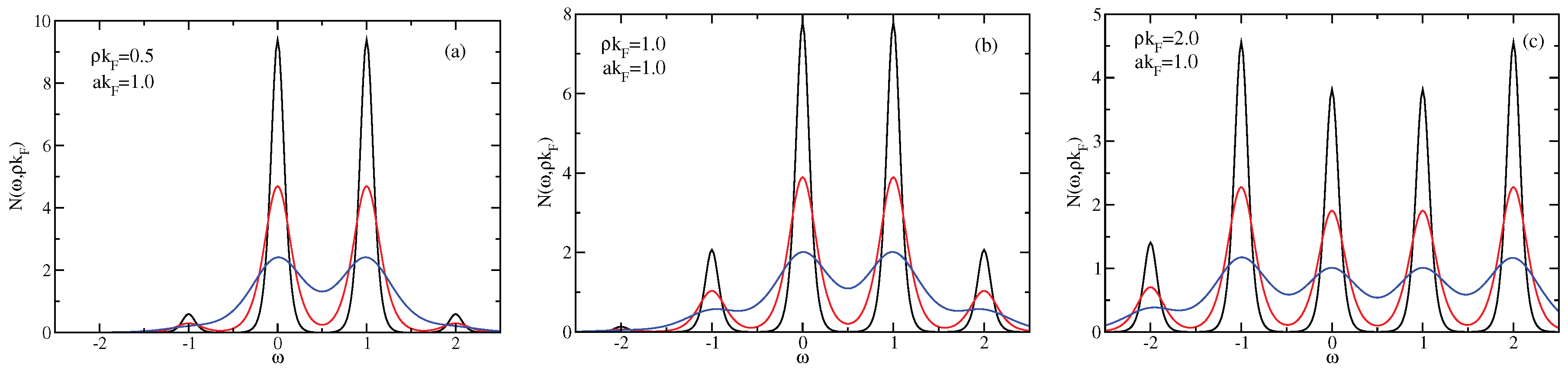

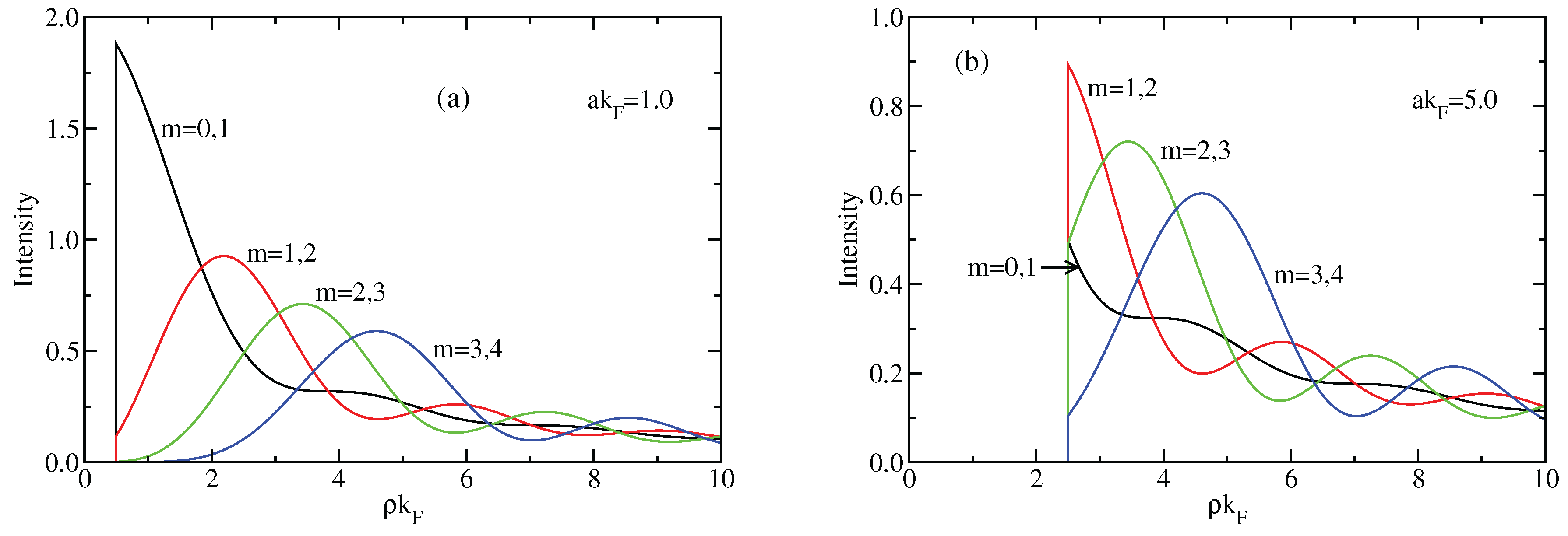

3.2. Local Density of Bound States

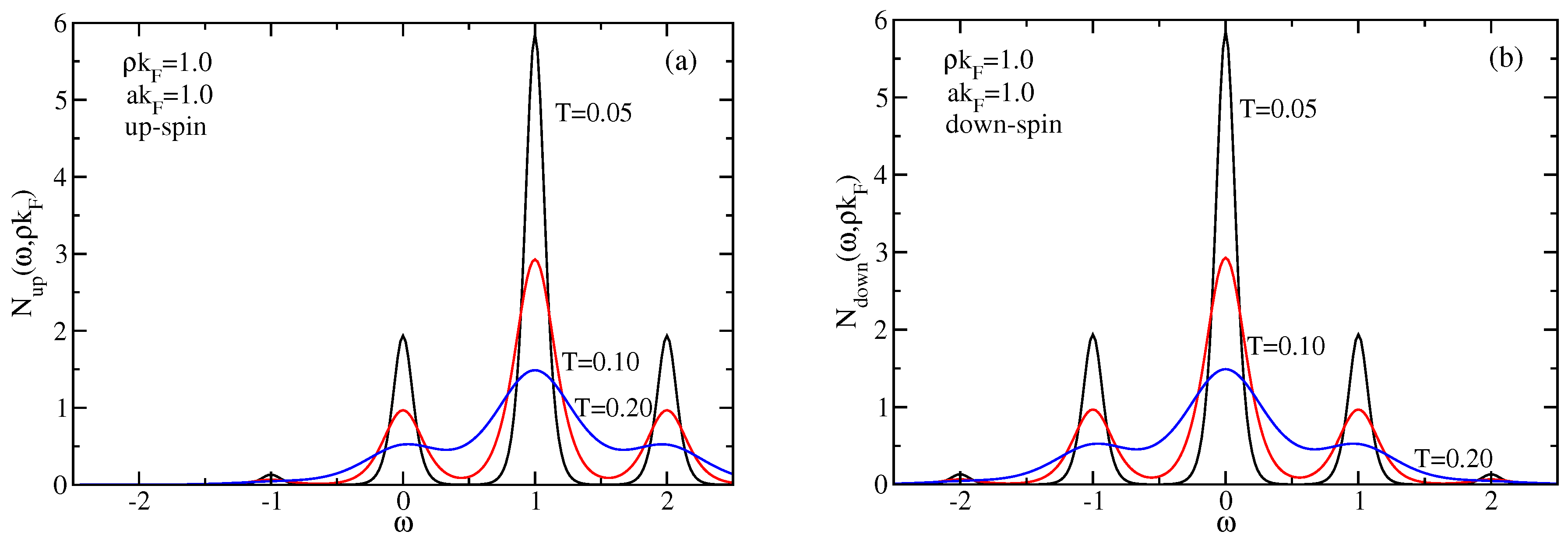

3.3. Spin Polarization

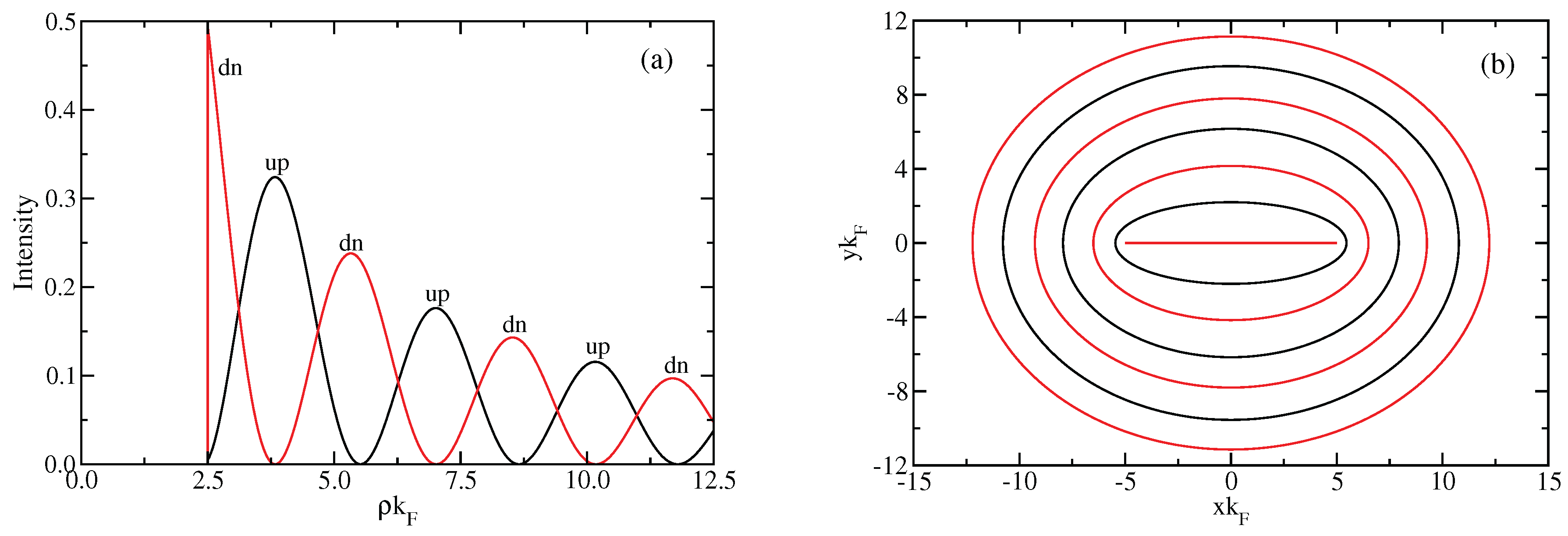

3.4. Orbits in Cartesian Coordinates

4. Concluding Remarks

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A. Solution of Bogoliubov-de Gennes Equations

Appendix A.1. Second Order Differential Equations

Appendix A.2. Solution for <

Appendix A.3. Solution for >

Appendix A.4. Matching of Wave Functions

Appendix A.5. Wave Functions for Excited States

References

- Beenakker, C.W.J. Search for Majorana Fermions in Superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. (2013), 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Yu. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Physics-Uspekhi (2001), 44, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Kane, C.L. Superconducting Proximity Effect and Majorana Fermions at the Surface of a Topological Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2010), 100, 096407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Kane, C.L. Probing Neutral Majorana Fermion Edge Modes with Charge Transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2009), 102, 216403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, J.D.; Lutchyn, R.M.; Tewari, S.; Das Sarma, S. Robustness of Majorana fermions in proximity-induced superconductors. Phys. Rev. B (2010), 82, 094522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Ch.-K.; Cole, W.S.; Das Sarma, S. Induced spectral gap and pairing correlations from superconducting proximity effect. Phys. Rev. B (2016), 94, 125304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmanov, A.L.; Rozhkov, A.V.; Nori, F. Majorana fermions in pinned vortices. Phys. Rev. B (2011), 84, 075141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akzyanov, R.S.; Rozhkov, A.V.; Rakhmanov, A.L.; Nori, F. Tunneling spectrum of a pinned vortex with a robust Majorana state. Phys. Rev. B (2014), 89, 085409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, J.D.; Lutchyn, R.M.; Tewari, S.; Das Sarma, S. A generic new platform for topological quantum computation using semiconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2010), 104, 040502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao; Li; Zhang, Ch. Robustness of Majorana modes and minigaps in a spin-orbit-coupled semiconductor-superconductor heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B (2010), 82, 174506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthod, C. Vorticity and vortex-core states in type-II superconductors. Phys. Rev. B (2005), 71, 134513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Bonesteel, N.; Schlottmann, P. Bound fermion states in pinned vortices in the surface states of a superconducting topological insulator. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter (2021), 33, 035604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlottmann, P. Local density of states in a vortex at the surface of a topological insulator in a magnetic field. Eur. Phys. J. B (2021), 94, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, C.W.J. Random-matrix theory of Majorana fermions and topological superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. (2015), 87, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziesen, A.; F. Hassler, F. Low-energy in-gap states of vortices in superconductor-semiconductor heterostructures. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter (2021), 33, 294001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioselevich, P.A.; Ostrovsky, P.M.; Feigel’man, M.V. Majorana state on the surface of a disordered three-dimensional topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B (2012), 86, 035441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.-I.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Tanaka, Y. Local density of states in two-dimensional topological superconductors under a magnetic field: Signature of an exterior Majorana bound state. Phys. Rev. B (2018), 97, 144516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akzyanov, R.S.; Rakhmanov, A.L.; Rozhkov, A.V.; Nori, F. Majorana fermions at the edge of superconducting islands. Phys. Rev. B (2015), 92, 075432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akzyanov, R.S.; Rakhmanov, A.L.; Rozhkov, A.V.; Nori, F. Tunable Majorana fermion from Landau quantization in 2D topological superconductors. Phys. Rev. B (2016), 94, 125428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamon, C.; Jackiw, R.; Nishida, Y.; Pi, S.-Y.; Santos, L. Quantizing Majorana fermions in a superconductor. Phys. Rev. B (2010), 81, 224515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaymovich, I.M.; Kopnin, N.B.; Mel’nikov, A.S.; Shereshevskii, I.A. Vortex core states in superconducting graphene. Phys. Rev. B (2009), 79, 224506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, C.W.J. Specular Andreev reflection in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2006), 97, 067007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroli, C.; De Gennes, P.G.; Matricon, J. Bound Fermion states on a vortex line in a type II superconductor. Phys. Lett. (1964), 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroli, C.; Matricon, J. Excitations électroniques dans les supraconducteurs purs de 2ème espèce. Phys. kondens. Materie (1965), 3, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.-H.; Zhang, K.-W.; Hu, L.-H.; Li, Ch.; Wang, G.-Y.; Ma, H.-Y.; Xu, Z.-A.; Gao, Ch.-L.; Guan, D.-D.; Li, Y.-Y.; Liu, C.; Qian, D.; Zhou, Yi; Fu, L.; Li, Sh.-Ch.; Zhang, Fu-Ch.; Jia, J.-F. Majorana Zero Mode Detected with Spin Selective Andreev Reflection in the Vortex of a Topological Superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2016), 116, 257003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Kong, L.; Fan, P.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Sh.; Liu, W.; Cao, Lu; Sun, Y.; Du, Sh.; Schneeloch, J.; Zhong, R.; Gu, G.; Fu, L.; Ding, H.; Gao, H.-J. Evidence for Majorana bound states in an iron-based superconductor. Science (2018), 362, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, T.; Sun, Y.; Pyon, S.; Takeda, S.; Kohsaka, Y.; Hanaguri, T.; Sasagawa, T.; Tamegai, T. Zero-energy vortex bound state in the superconducting topological surface state of Fe(Se,Te). Nat. Matter (2019), 18, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Atomic line defects and zero-energy end states in monolayer Fe(Te,Se) high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Phys. (2020), 16, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyuzin, A.; Alidoust, M.; Loss, D. Josephson junction through a disordered topological insulator with helical magnetization. Phys. Rev. B (2016), 93, 214502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkova, I.V.; Bobkov, A.M. Electrically controllable spin filtering based on superconducting helical states. Phys. Rev. B (2017), 96, 224505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elliptic-Coordinate-System.

- Abrikosov, A.A. On the magnetic properties of superconductors of the second group. Soviet Phys. JETP (1957), 5, 1174. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.-P.; Wang, M.-X.; Liu, Z. L.; Ge, J.-F.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.; An Xu, Z.; Guan, D.; Gao, Ch. L.; Qian, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.-H.; Zhang, Fu-Ch.; Xue, Qi-K.; Jia, J.-F. Experimental Detection of a Majorana Mode in the core of a Magnetic Vortex inside a Topological Insulator-Superconductor Bi2Te3/NbSe2 Heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2015), 114, 017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.-H.; Jia, J.-F. Majorana zero mode in the vortex of an artificial topological superconductor. Science China: Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2017), 60, 057401. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Zhu, S.; Papaj, M.; Chen, H.; Cao, Lu; Isobe, H.; Xing, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, D.; Fan, P.; Sun, Y.; Du, S.; Schneeloch, J.; Zhong, R.; Gu; Fu, G.L.; Gao, H.-J.; Ding, H. Half-integer level shift of vortex bound states in an iron-based superconductor. Nat. Phys. (2019), 15, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlottmann, P. In-gap states of vortices at the surface of a topological insulator. Physica C: Superconductivity and its Applications (2022), 596, 1354047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.; Kümmel, R.; Jacobs, A.E.; Tewordt, L. Structure of Vortex Lines in Pure Superconductors. Phys. Rev. (1969), 187, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).