1. Introduction

Housing insecurity continues to be one of the most urgent social problems in the United States. Eviction is central to housing insecurity. Each year, landlords file over 3.6 million eviction cases nationally; low-income households, Black and Latino renters, and families led by women are disproportionately affected (Desmond, 2016; Hepburn et al., 2020). Eviction is not a singular, legal event; instead, it is a structural driver of poverty and inequality tied to poor mental and physical health, increases in homelessness, and disruptions to education and employment (Hatch and Yun, 2021; Himmelstein and Desmond, 2021). Recently, scholars have increasingly acknowledged eviction as a housing crisis and a public health issue, with lasting implications for equity and well-being (JAMA Network Open, 2023).

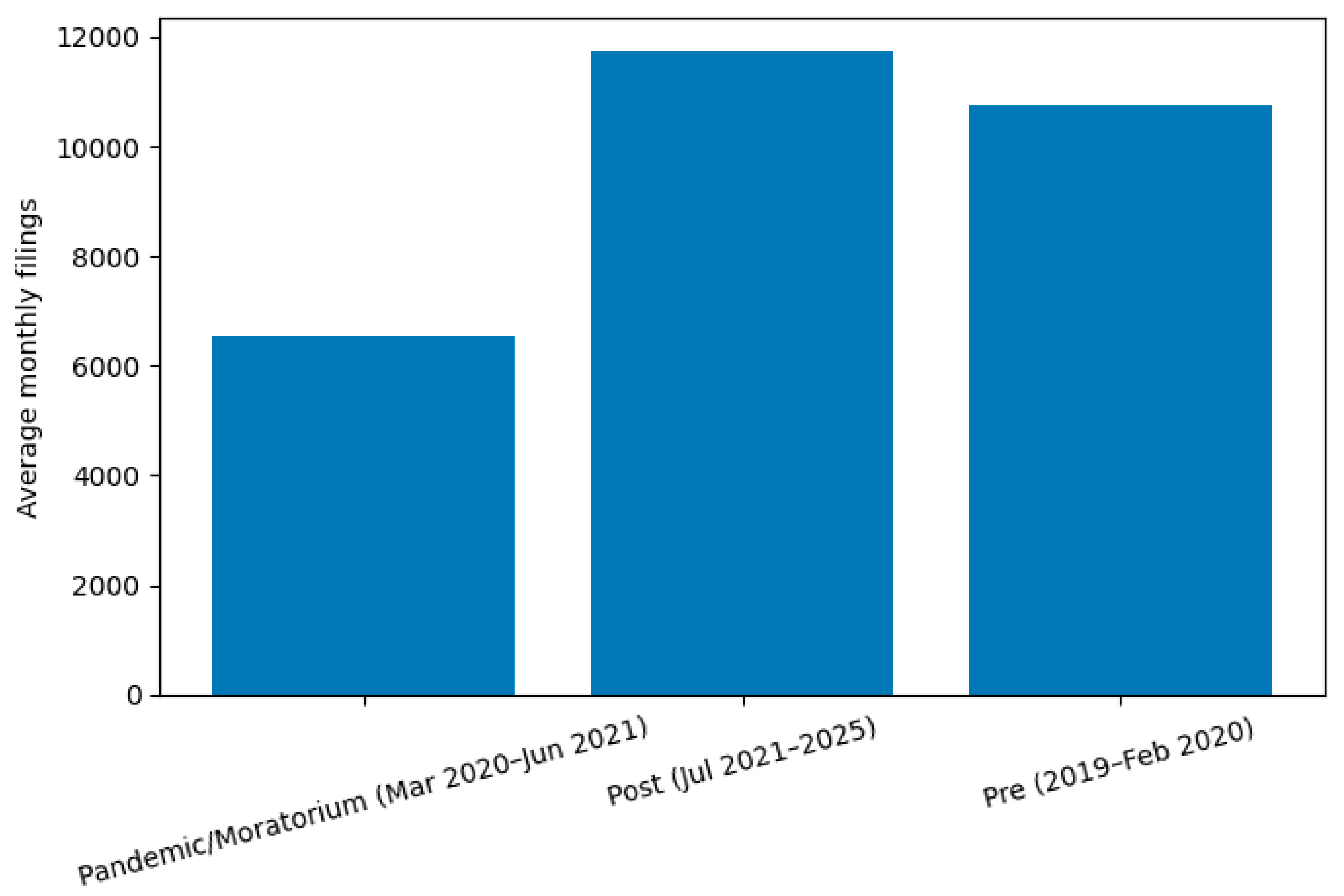

The COVID-19 pandemic magnified these vulnerabilities, leading to unprecedented interventions. Federal and state eviction moratoria, alongside emergency rental assistance, sharply reduced filings across the country and helped prevent mass displacement (Benfer et al., 2021; Almagro et al., 2022). One national study estimated that these protections prevented 1.55 million COVID-19 cases and more than 40,000 deaths (Leifheit et al., 2021). Yet scholars caution that such measures merely delay rather than resolve displacement (Benfer et al., 2020). Florida, one of the largest rental markets in the United States, with over 2.7 million renter households (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University [JCHS], 2023), vividly illustrates this dynamic. During the moratorium period, filings dropped by nearly 40%, averaging 6,551 per month, but after July 2021, filings rebounded to 11,754 per month, surpassing pre-pandemic levels (Eviction Lab, 2025).

The "eviction cliff" highlights the effectiveness and the shortcomings of moratoria. They temporarily curtailed eviction filings, but not structural factors such as increased rents, stagnant wages, weak tenant protections, and racialized access to housing (Desmond, 2016; Marcal et al., 2022; Mumford et al., 2022). Thus, eviction activity quickly reverted to pre-pandemic levels, again exposing vulnerable households. Florida's experience reflects national debates around whether temporary crisis responses can reshape longer-term eviction trajectories without more sustained and structural changes in housing policy.

In this study, we considered eviction filings in Florida from 2019 to 2025 with the hopes of revealing timely, statistically significant differences before, during, and after COVID-19. We used descriptive, inferential, and time-series analysis to understand the suppressive impacts of moratoria, the degree of rebound, and how seasonal cycles shape eviction filings. The overall purpose of the analysis is to inform housing policy by better understanding the boundaries of temporary policy changes, while emphasizing the importance of building structural alternatives, such as increasing the availability of rental assistance, increasing tenant protections, and providing equitable access to legal representation to diminish the ability of evictions to perpetuate instability and inequality (Benfer et al., 2021; NLIHC, 2022).

This article presents Florida’s eviction moratorium as an ineffective reform. It provided temporary relief but failed to address structural problems associated with housing instability. Eviction moratoria served as crisis-oriented stopgaps much in the way that permanent rent vouchers, right to counsel laws, or expanded social housing might serve as structural reforms. Moratoria resembled other forms of temporary welfare emergency measures during COVID-19, such as extended unemployment insurance, expanded Medicaid, short-term Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) supplements, and other measures. Importantly, these broader interventions have highlighted gaps in the U.S. welfare state, and moratoriums and eviction filings have since exposed the inadequacies of temporary crisis measures to remedy entrenched inequalities in housing markets. The increase in eviction filings underscores that if structural reforms—as well as codifying tenant protections and affordability plans over time—are perpetually left unaddressed, we will only exacerbate racial, gender, and class disparities in housing access and stability.

Finally, this study illustrates the limitations of temporary measures in addressing access to deep structural housing inequalities. Although moratoria could provide short-term relief, their end highlights that crisis-driven, nonstructural reforms risk recreating or further entrenching inequality. Florida's post-pandemic "eviction cliff", the sharp spike in evictions that immediately followed the expiration of COVID protections, presents a warning to all politicians and a challenge, showing how crisis policy can devolve into insufficiently effective institutionalized welfare reform. Florida's experience provides not just a single state-level case, but also larger lessons for an international discussion about the limits of temporary, crisis-based welfare responses. By analyzing Florida alongside broader discussions of housing policy, this analysis draws out dynamics that may apply to other liberal welfare states and contexts in the world that are wrestling with how to balance emergency protections with structural inequities in housing.

Research Question: How did institutional temporality, through critical junctures, path dependence, and punctuated equilibrium, shape eviction-filing patterns in Florida between 2019 and 2025?

2. Theoretical Framework

We interpreted eviction trajectories through an institutional temporal framework, averring that historical and time-specific contexts impact policy and institutional structures (Pierson, 2000; Thelen, 2004). Institutions are not static; they create incentive structures and routines (e.g., court calendars, filing rules, and lease practices) that are “sticky,” producing long stretches of stability punctuated by episodes of rapid change. Many political scientists argue that we can only understand policy outcomes by attending to timing, sequencing, and duration rather than static “snapshot” models (Pierson, 2000; Thelen, 2000). Five interrelated concepts are central to this approach: path dependence, critical junctures, conversions, policy drifts, and punctuated equilibrium. The remainder of this section discusses each concept under the umbrella of what we refer to as institutional temporality; then, we explain how this paper leverages institutional temporality to understand eviction-filing patterns in Florida over 7 years.

Explaining institutional temporality through the lens of comparative welfare-state theory illuminates why the U.S. response to eviction stands as a clear example of the limits of liberal welfare regimes. As emphasized by Esping-Andersen (1990) and Korpi (2006), liberal welfare states rely on markets and piecemeal, means-tested benefits rather than universal decommodification. In this sense, eviction moratoria functioned more as temporary makeshift adjustments rather than structural changes, reflecting the US overall approach to crisis management rather than redesigning institutional practices for the long-term. In this respect, Pierson’s (2000) work on path dependence is very much in step with this understanding: when temporary protections were removed, the self-reinforcing tendencies of landlord–tenant law, paired with the historically weak foundations of social housing institutions, were able to reset equilibria quickly. The metaphor of punctuated equilibrium applies not only to the time series of filing trajectories in Florida but equally to welfare reforms generally. U.S. housing and welfare policy shifts quietly appear after crises create demands for shifts, such as The New Deal, The Great Society, or the pandemic, but seldom survive as structurally reformed features. This institutional pattern explains why eviction moratoria could not produce lasting protections, regardless of their staggering impact, but ultimately exacerbated inequality as the equilibrium reset.

2.1. Institutional Temporality

A key political science framework to conceptualize time’s compounding impact on policy decisions and institutional shifts is the concept of path dependence. Path dependence references the tendency of institutional arrangements, once established, to generate self-reinforcing feedback that stabilizes regimes and makes departures costly (Pierson, 2000a, 2000b; Thelen, 2000). Path-dependent processes share several defining features that help explain how institutions evolve. Pierson (2000b) emphasized that self-reinforcing dynamics propel such processes such that mechanisms like learning effects, sunk investments, and increasing returns cause each subsequent step along a chosen trajectory to reinforce the direction of travel, lowering the likelihood of reversal. At the outset, during what scholars call a critical juncture, the range of potential futures is relatively open, and even small decisions can have significant consequences. Over time, however, institutions exhibit a pattern of early openness followed by later closure, as rules harden and routines become entrenched, narrowing the scope for deviation.

Path dependence also entails a heightened sensitivity to timing and sequence. In such processes, the timing of events matters as much as the events themselves: small shocks that occur early in a sequence can decisively alter institutional trajectories. In contrast, institutions may absorb larger shocks that occur later with little visible effect. Importantly, path dependence suggests persistence but not permanence. Institutions display a strong tendency toward stability, but they are not immutable; change is usually incremental and bounded, and significant disruption is required to unsettle the status quo. Pierson (2000b) highlighted that these dynamics often unfold in three stages: a critical juncture in which outcomes are relatively open, a reproduction phase in which feedback mechanisms stabilize and reinforce institutional routines, and eventual disruption, when reproduction mechanisms weaken or collapse. However, a critical juncture could lead to a punctuated equilibrium, or an abrupt and unexpected institutional and policy shift due to the external force that forces the creation of an entirely new approach and new feedback mechanism (Jones and Baumgartner, 2012).

Alongside this picture of reinforcement and bounded change, Thelen (2000) introduced the concept of functional conversion as a mechanism that highlights the coexistence of continuity and adaptation. Conversion occurs when existing institutional structures are redirected toward new purposes, even as their formal design remains intact. Institutions created for one set of ends may, under shifting political or economic conditions, be “turned to wholly new ends” without being dismantled (Thelen, 2000, p. 107). This mechanism underscores how institutional persistence can mask subtle but meaningful transformation, as actors repurpose organizations or rules in response to new pressures. Unlike breakdown or replacement models, functional conversion draws attention to incremental adaptation and the capacity of institutions to generate outcomes quite different from those originally intended.

Although the result of a critical juncture could lead to a punctuated equilibrium or conversion that changes the function of policy or institutions, a critical juncture can also lead to a policy drift. Hacker (2004) described drifts as “the changes in the operation or effect of policies that occur without significant changes in those policies’ structure (246).” Unlike policy or institutional conversions that adapt policy implementation to address new needs, a drift refers to the lack of policy or institutional change over time, despite the impetus of a critical junction.

Together, these concepts demonstrate how institutions combine long stretches of stability with the potential for abrupt disruption and for gradual repurposing. These concepts underscore why political scientists argue that timing, sequencing, and feedback effects are central to political and policy outcomes: not only does the magnitude of events shape institutions, but also the order of events, their duration, cumulative reinforcement, and capacity for functional adaptation shape institutions.

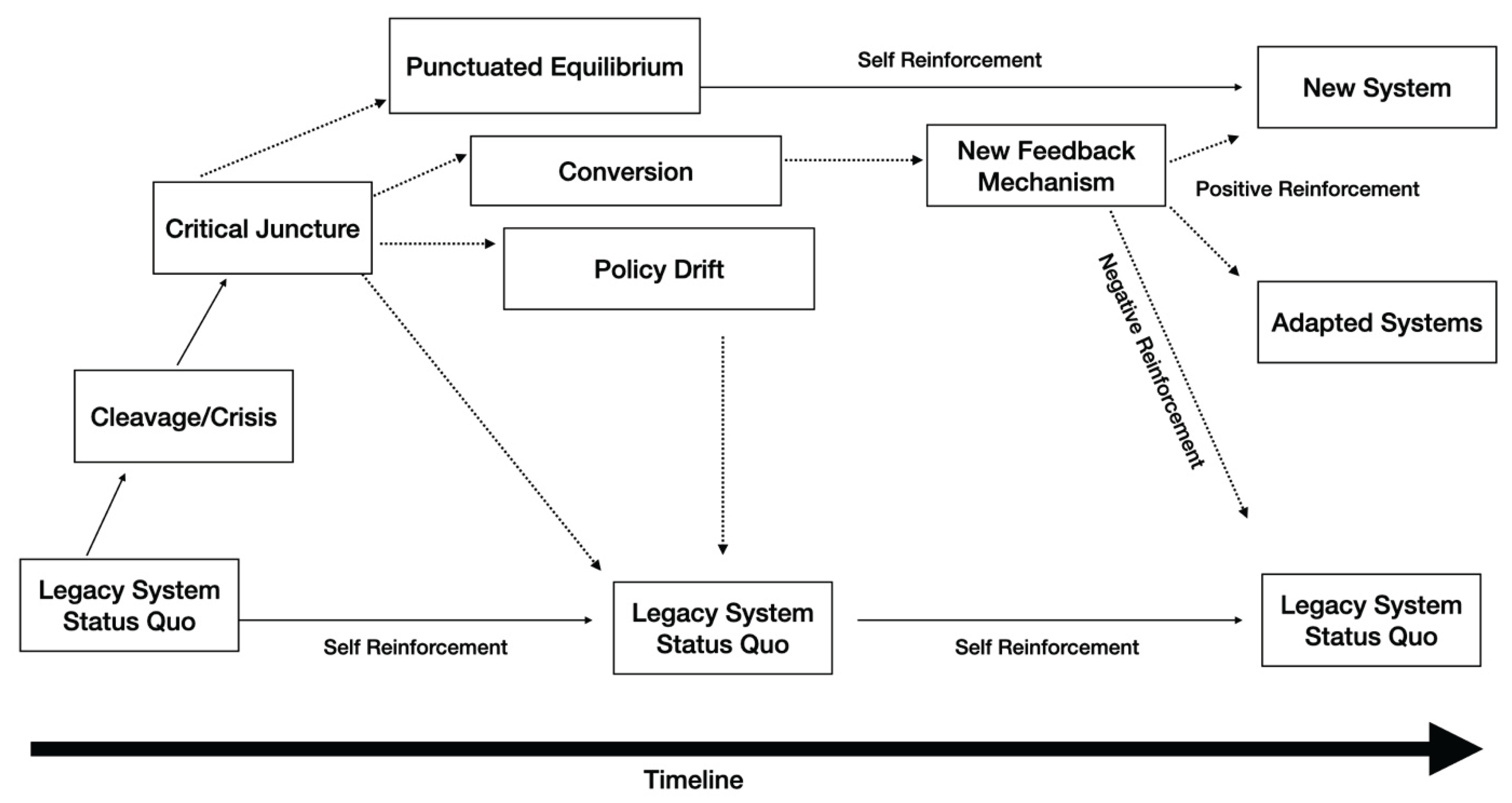

Figure 1 illustrates how crises can produce critical junctures and offer various policy alternatives. This model illustrates how crises or cleavages can produce critical junctures that loosen constraints that redirect institutional trajectories (Collier and Collier, 2002; Pierson, 2000). From these junctures, institutions may undergo (a) policy drift, in which unchanged structures generate new and often more adverse outcomes under shifting socioeconomic conditions (Hacker, 2004); (b) conversion, in which existing rules are repurposed toward new functions without formal redesign (Thelen, 2000, 2004); or (c) punctuated equilibrium, in which long stretches of stability give way to abrupt, discontinuous change driven by shifting attention and feedback dynamics (Jones and Baumgartner, 2012). These branching pathways underscore how institutions combine persistence with disruption, adaptation, and potential transformation across time.

The framework of institutional temporality shaped the design of this study and the interpretation of its results. Because social scientists emphasize timing, sequencing, and structural breaks, we selected the methodology to capture precisely those dimensions. The use of segmented regression and joinpoint analysis (discussed in the methods section) reflects the theoretical expectation that critical junctures mark institutional processes, followed by new trajectories rather than smooth, continuous change. For this paper, we viewed the COVID-19 pandemic as an external crisis that triggered eviction moratoriums as a critical juncture capable of dramatically changing or repurposing mechanisms and institutions’ approach to maintaining residents’ housing.

Similarly, the decision to examine monthly and annual filing patterns, and to align them with the timing of policy interventions, stems directly from the premise that institutions’ structure not just outcomes, but their temporal rhythms. By foregrounding path dependence and punctuated equilibrium, the methodology is attuned to long periods of stability and sharp departures, particularly when legal or administrative rules shifted.

We interpret the findings through this same lens. Rather than treating eviction filings as mere fluctuations in housing demand, the analysis situates them as institutionally mediated sequences shaped by feedback mechanisms and policy shocks. For example, a persistent and durable decline in eviction filings after the critical juncture of eviction moratoria would suggest the development of a new feedback mechanism addressing housing precarity. In contrast, if evictions revert to their pre-COVID-19 rates, the data suggest the eviction moratoria were a minor deviation in preexisting patterns in the preestablished equilibrium cycle.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Setting and Time Frame

In this study, we evaluated monthly eviction filings in Florida from January 2019 to March 2025. We chose Florida as a study site because it is among the largest rental markets in the United States and enacted housing interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic, including eviction moratoria and emergency rental assistance that paralleled interventions implemented nationwide. The pre-pandemic (January 2019–February 2020), pandemic/moratorium (March 2020–June 2021), and post-moratorium phases (July 2021–March 2025) aligned with actual federal and state policies and allowed structural breaks to be identified in eviction activity.

3.2. Data Source and Preparation

The Eviction Lab at Princeton University provided the dataset, collecting eviction records based on legal documents filed in court (Eviction Lab, 2025). The Eviction Lab dataset for Florida provided monthly and annual counts of eviction filings between 2019 and 2025. Count outcomes included (a) total filings altogether and (b) filings standardized per 1,000 renter households. Processing the data took place in Python 3.12 using the Pandas library (McKinney, 2010). Data-preparation steps included (a) standardizing variable names; (b) constructing a continuous monthly datetime index; (c) classifying each observation into one of the three policy periods; and (d) flagging missing data by only excluding incomplete months, as we did not want any imputation to conceal volatility. After the data preparation, we created a clean monthly panel dataset for descriptive and inferential analyses.

3.3. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

We summarized baseline eviction trends with descriptive statistics. We calculated annual totals and year-over-year percentage differences to account for variability (Moore et al., 2017). We estimated mean monthly eviction filings (total, continued, and per 1,000 renter households) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each policy time period, using the t-distribution as estimates based on relatively small sample sizes (n ≈ 12 for each year; Student, 1908; Ruxton, 2006). These descriptive statistics served as the basis for the following comparisons of eviction dynamics across policy phases.

3.4. Inferential Statistical Analysis

To determine whether eviction activities differed across policy periods, we used several inferential statistics. First, we evaluated the Shapiro–Wilk test (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965) for normality of each policy period's monthly distributions of filings. In instances when our normality assumptions were satisfied, we used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate differences between levels (Fisher, 1925; Gelman, 2005). When the normality assumption was not satisfied, we used the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952).

When omnibus tests indicated significant differences, we also used post hoc procedures. In ANOVA models, we used Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference Test to try and determine how two levels of policy periods differed (Tukey, 1949). When we completed Kruskal–Wallis analyses, we used the Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons (Mann and Whitney, 1947; Dunn, 1964). This combination of the parametric and nonparametric methods provided robust inferences under different requirements of distributions.

3.5. Trend and Breakpoint Modeling

We estimated segmented and joinpoint regressions to determine changes in the trend of eviction activity. Segmented (or piecewise) regression had breakpoints established at March 2020 (moratorium initiated) and July 2021 (moratorium ended). To account for possible autocorrelation in monthly time-series data, we used Newey–West heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation-consistent standard errors (Newey and West, 1987). In addition, we applied joinpoint regression to identify breakpoints based on the data, with no requirement that they aligned with policy dates. We evaluated competing models with varying numbers of joinpoints using the Bayesian Information Criterion (Schwarz, 1978). This combination of analyses provided policy-guided and data-driven evaluations of structural change (Kim et al., 2000).

3.6. Seasonality and Time-Series Decomposition

We present the findings in several ways, all of which provide illustrations of dynamic processes and patterns relevant to policy. We used line graphs with the relevant policy markers to show differences among the monthly filings over time; bar charts show cross-policy comparisons of mean filings; heatmaps show differences in filings per 1,000 renter households, by month, and throughout each year. The cyclical nature of the data warranted the inclusion of seasonality plots. Finally, we include regression overlays from segmented and joinpoint models to capture changes in the structure of filing trajectories. We generated all figures in Python using the matplotlib package (Hunter, 2007).

3.7. Visualization Strategy

We display the findings using different visual methods to emphasize the variability in time as well as in potential policy implications. Line graphs that include highlighted policy markers show the variation in monthly filings over time. Bar charts compare the mean filings by month in policy periods. Heat maps display the number of filings per 1,000 renter households by month and year. Seasonal plots display cyclical patterns by month, and regression plot overlays from segmented and joinpoint models illustrate what structural changes occurred in the trajectory of filings over time. We generated all figures in Python with the matplotlib package (Hunter, 2007).

3.8. Software and Reproducibility

We carried out the analyses in Python 3.12. We performed data wrangling using the Pandas (McKinney, 2010) and NumPy (Oliphant, 2006) packages. Descriptive and inferential statistics emerged using SciPy (Virtanen et al., 2020) and Statsmodels (Seabold and Perktold, 2010), and we conducted the seasonal decomposition with the seasonal_decompose function in Statsmodels. We made graphs using matplotlib (Hunter, 2007). All analysis scripts are available upon request for reproducibility purposes.

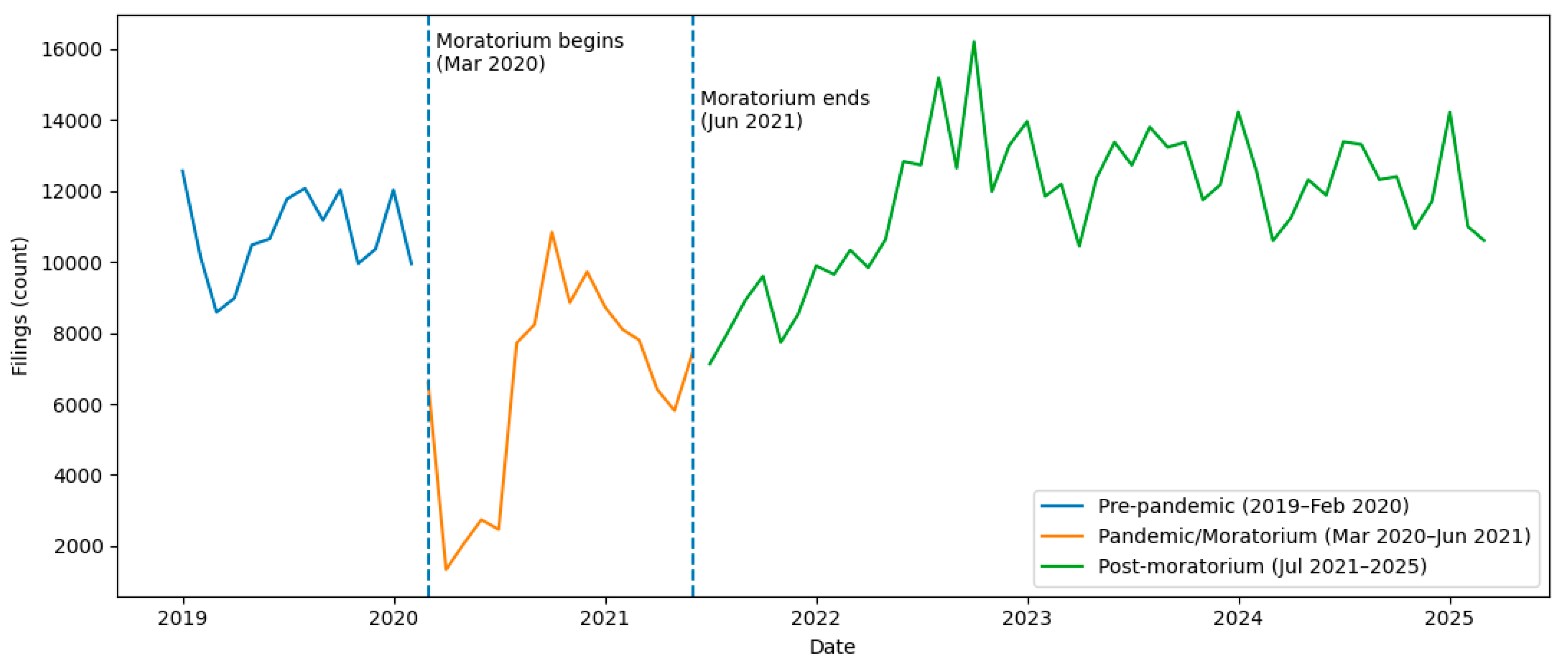

Figure 2 shows eviction filings over three policy time periods: pre-pandemic (2019–Feb 2020), pandemic/moratorium (Mar 2020–Jun 2021), and post-moratorium (Jul 2021–2025). Filings sharply dropped during the moratorium and stayed well below pre-pandemic rates. After the moratorium ended, filings quickly recovered and plateaued at significantly higher levels than before the pandemic.

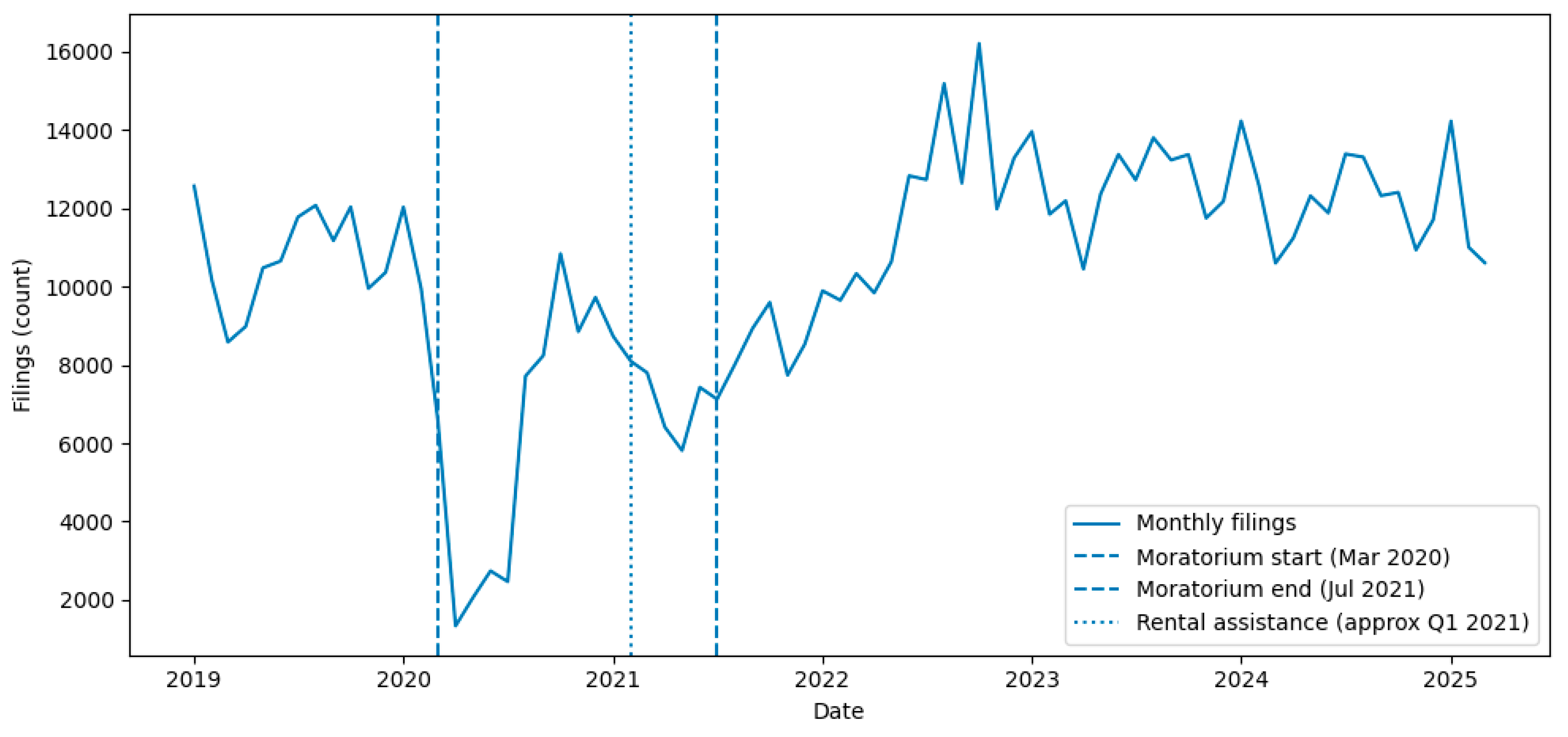

Figure 3 displays monthly filings with vertical lines for the beginning of the moratorium (Mar 2020), end of the moratorium (Jul 2021), and deployment of rental assistance (around Q1 2021). The graph depicts the sudden and precipitous fall in filings as soon as the moratorium started, suppression halfway through 2021, and a resumption of filings sharply after the moratorium's conclusion. Rental assistance seems to have offered only partial relief because filings rose strongly once protections lapsed.

Table 1 shows considerable variation by policy periods. During the moratorium (Mar 2020–Jun 2021), mean monthly eviction filings were lowered to 6,551 (95% CI: 5,004–8,098), or 2.37 filings per 1,000 renter households (95% CI: 1.81–2.93). By comparison, pre-pandemic filings averaged 10,766 (95% CI: 10,064–11,468), or 3.89 per 1,000 (95% CI: 3.64–4.15), and post-moratorium filings climbed to 11,754 (95% CI: 11,165–12,343), or 4.25 per 1,000 (95% CI: 4.03–4.46). These results underscore the moratorium's suppressive effect and the steep rebound in eviction activity following the termination of protections.

Table 2 shows that international statistical tests reveal extremely significant differences in eviction filings in the three policy periods. One-way ANOVA findings revealed that both the number of monthly filings, F(2, N) ≈ 36.71, p < .001, and 1,000 renter household filings, F(2, N) ≈ 36.67, p < .001, differed significantly based on whether the period was pre-pandemic, under the moratorium, or post-moratorium. These findings warrant further post-hoc tests to determine when the periods diverge significantly from each other.

As shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4, post-hoc analysis found that evictions filed during the pandemic/moratorium period were significantly lower than in pre-pandemic and post-moratorium periods (

p < .001). On average, filings decreased by 4,215 to 5,203 cases per month, which translates to decreases of about 1.5–1.9 filings per 1,000 renter households. Yet no statistically significant disparity emerged across the pre-pandemic and post-moratorium phases (p > .05), indicating that eviction activity reverted to levels similar to, or even higher than, pre-pandemic standards, once safeguards were lifted.

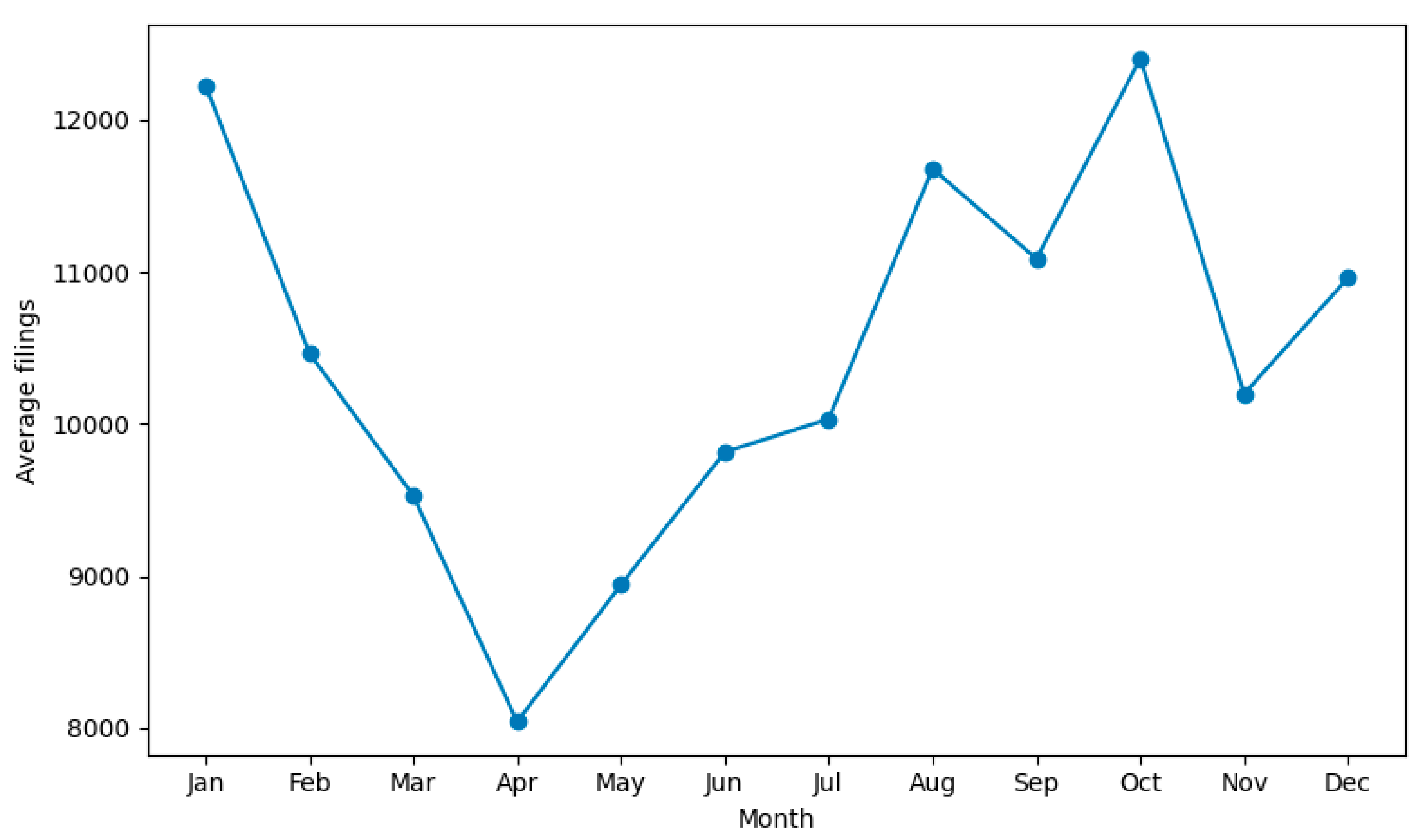

Figure 4 indicates an obvious seasonal fluctuation in eviction filings. Filings are generally highest in January and October, reaching above 12,000 cases on average. Filings are lowest in April, averaging slightly more than 8,000 cases. The secondary peak is seen in late summer and early fall (August–October). These trends indicate that eviction activity has a cyclical pattern, with troughs in spring and spikes at the beginning and end of the year, which could be indicative of household spending cycles, lease renewal, and holiday-related influences.

Table 5 shows that the segmented regression model detects significant shifts in eviction-filing trends during important policy intervals. Before the moratorium, filings trended modestly downward (

β = –431,

p < .01). During the moratorium interval (Mar 2020–Jun 2021), filings trended significantly higher compared to the baseline trend (

β = +622,

p < .05), indicating a brief resumption of activity in spite of restrictions. In contrast, the post-moratorium era (Jul 2021–2025) failed to exhibit a statistically significant difference (

β = –99,

p = .50), indicating that filings leveled off at levels equal to the immediate post-moratorium baseline.

As shown in

Table 6, the joinpoint regression specified two statistically optimal breakpoints: July 2020 and January 2023. During the initial segment (Jan 2019–Jul 2020), filings decreased abruptly at a rate of 365 cases per month on average. From Jul 2020 to Jan 2023, filings grew by approximately 246 cases per month, indicating the partial rebound of eviction activity after the initial months of the pandemic. Following Jan 2023, filings decreased marginally (–55 cases per month), reflecting a stabilization phase following recovery. The findings identify discrete phases of eviction trends associated with policy interventions and resultant market responses.

Model Fit:

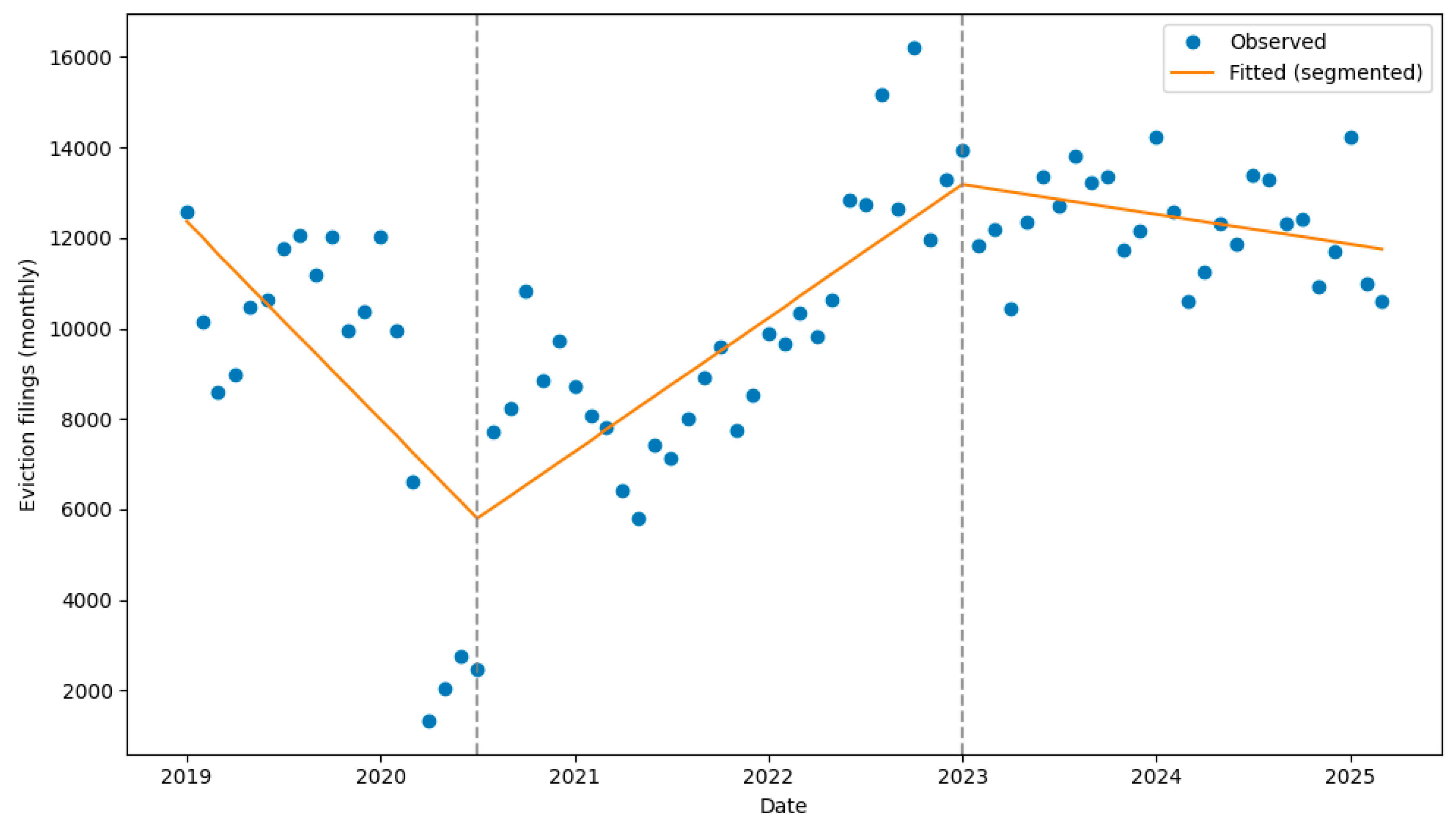

Figure 5 plot illustrates the joinpoint segmented regression model of monthly eviction filings. Blue dots indicate observed filings, and the orange line indicates the fitted segmented regression. We detected two breakpoints: July 2020 and January 2023.

Segment 1 (2019–Jul 2020): A steep drop in filings indicated the initial impact of the pandemic and early moratoriums.

Segment 2 (Jul 2020–Jan 2023): A steepening upward trend in filings emerged as limits relaxed and backlog cases began courtship.

Segment 3 (Jan 2023–2025): A modest downward correction indicated stabilization in eviction activity after the rebound.

The model identifies statistically significant structural shifts in eviction trends, closely related to significant policy changes and post-pandemic recovery phases.

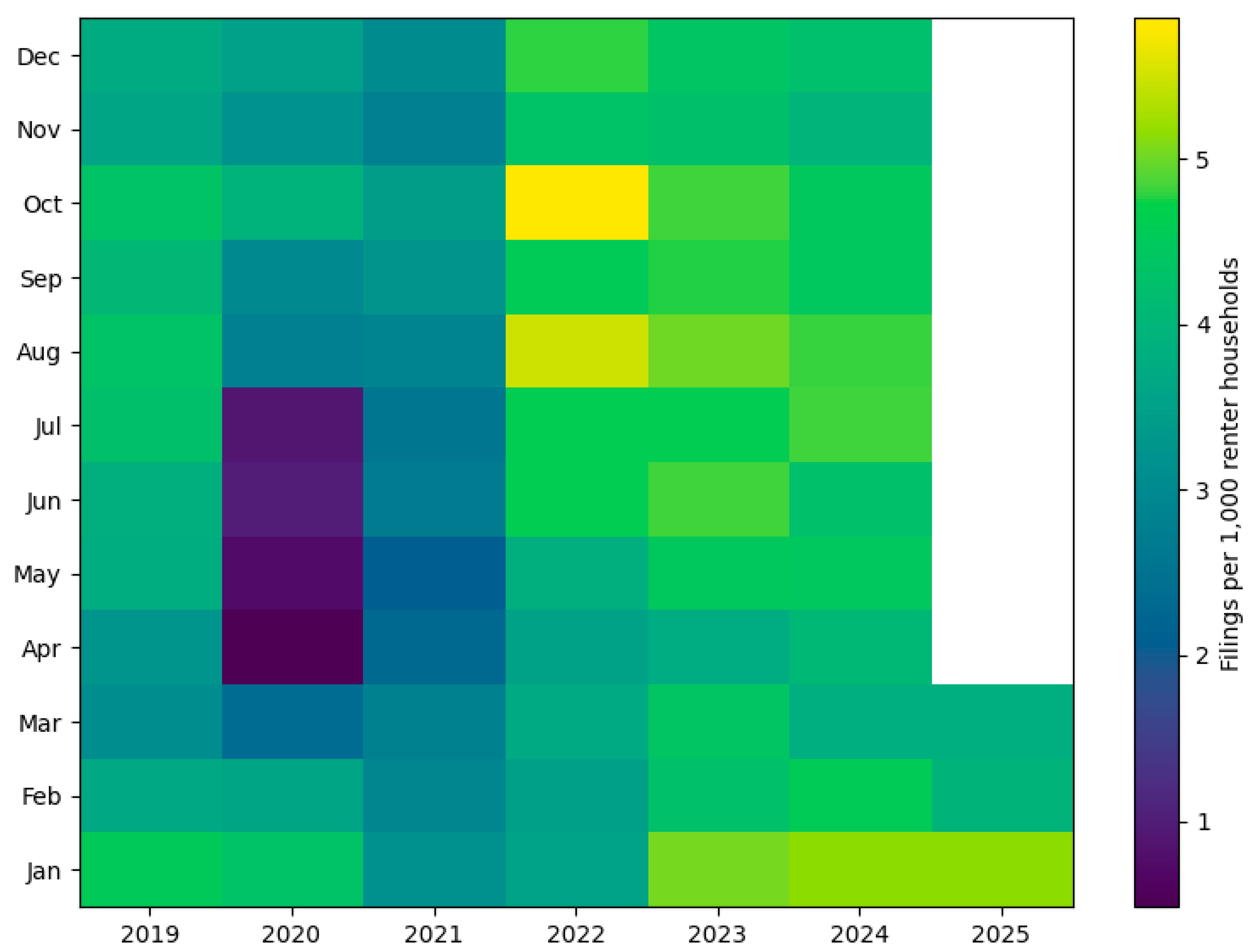

Figure 6 shows monthly eviction filings normalized per 1,000 renter households by year. Darker areas represent lower filing rates, while lighter areas reflect greater activity.

Pandemic/Moratorium Period (2020–2021): Filings per 1,000 renter households declined dramatically, particularly in spring 2020 as a result of the moratorium's shielding impact.

Post-moratorium Recovery (2022–2023): A dramatic spike emerged, with some of the highest filing rates (e.g., late 2022–2023).

Seasonal Patterns: Eviction rates are higher persistently during the fall season (August–October) and lower during early spring (March–April).

The

Figure 6 heatmap identifies quite well how pressure of evictions differed over years and in seasonal cycles, and the effect of COVID-19 interventions and rebound is quite evident.

The

Figure 7 bar chart juxtaposes Florida's average monthly eviction filings during three discrete policy time periods.

Pre-pandemic (2019–Feb 2020): Average monthly filings were comparatively high (approximately 10,700).

Pandemic/Moratorium (Mar 2020–Jun 2021): Filings plummeted to their lowest point (approximately 6,500 per month) in response to the success of eviction moratorium policies.

Post-moratorium (Jul 2021–2025): Filings rose substantially to the study period's highest level, averaging close to 11,800 per month, surpassing pre-pandemic rates.

Figure 7 shows the sharp drop in filings through the moratorium and the return to higher-than-previous pandemic levels subsequently, emphasizing the long-term effect of COVID-19 housing policy responses.

4. Discussion

In this study, we looked at eviction filings in Florida from 2019 to 2025 and the differences in filings before the COVID-19 eviction moratorium, during the moratorium, and what happened after. The story is quite clear: filings during the moratorium went down greatly, but once the protections ended, filings quickly returned, and in some cases surpassed pre-pandemic levels (Leifheit et al., 2021; Hepburn et al., 2020). The information clearly demonstrated that moratoriums did provide immediate relief to renters in the short term and protected a great many people from eviction (Benfer et al., 2021). However, as demonstrated by the increase in filings after the moratorium ended, the moratorium only delayed displacement, not prevented it. A return to vulnerability exists even with moratoriums, without expanded rental assistance, fiscal or income subsidies, or the governmentalization of landlord–tenant law (Desmond, 2016). We return to our theoretical framework of Institutional Temporality to deepen the interpretation of these findings.

4.1. Linking Findings to Institutional Temporality

Institutional temporality provides a useful framework for interpreting these dynamics. The COVID-19 pandemic and the state’s eviction moratoria operated as critical junctures. They created external conditions in the housing market and established brief periods where institutional constraints loosened and filing practices sharply diverged from their usual trajectory (Collier and Collier, 2002; Pierson, 2000b, 2000a). By raising the costs or rendering it legally impossible to pursue evictions, these interventions produced an exogenous contraction in filings, consistent with accounts that underscore how brief but decisive breaks in sequence can redirect institutional trajectories.

Once these temporary protections expired, however, path dependence quickly reasserted itself. Entrenched landlord–tenant law, court routines, and property-management practices restored the incentives to file, stabilizing filings near or above their pre-pandemic baseline. This stabilization reflects Pierson’s (2000b) emphasis on self-reinforcing institutional feedback, such that routines and precedents make reversal costly and reversion likely. At the same time, the pandemic period illustrates Thelen’s (2000) concept of functional conversion: even as Florida’s landlord–tenant institutions remained formally unchanged, they were temporarily repurposed in response to shifting socioeconomic pressures. Courts adapted their roles to accommodate backlogs and rental-assistance programs while redirecting filing processes to serve new, crisis-driven purposes. This brief repurposing highlights how institutional continuity and adaptation can coexist, though the absence of structural reform meant conversion remained temporary.

Importantly, in Florida, policy drift did not merely return the system to the status quo pre-COVID-19 moratorium; rather, it produced a more precarious equilibrium. As rents escalated, wages stagnated, and household incomes became more volatile, the unchanged institutional framework of landlord–tenant law interacted with increasingly harsh socioeconomic conditions. This outcome reflects Hacker’s (2004) insight that inaction can function as a form of policy change: failing to adapt institutions in the face of shifting external pressures can magnify inequality over time. In this case, the expiration of temporary protections coincided with worsening housing-market conditions, yielding eviction rates that not only rebounded but, in some periods, exceeded pre-pandemic norms.

Finally, the broader trajectory of filings fits the model of path dependence. Long stretches of relative stability and seasonal rhythms gave way to sharp disruptions aligned with policy events, such as the onset and expiration of moratoria and the advent of emergency rental assistance. These shocks produced the structural breaks identified in the time-series analyses, after which filings settled into new equilibria shaped by institutional routines and by shifting socioeconomic pressures.

The Florida case demonstrates the limits of crisis-based interventions. Critical junctures can temporarily disrupt eviction processes, but without structural reform across institutions, path dependence and policy drift pull institutions back into equilibrium, often one that is even more adverse than before. Functional conversion during the pandemic demonstrated institutional adaptability, but it was short-lived, underscoring that durable change requires more than temporary repurposing. To prevent future cycles of displacement, policymakers must pursue structural reforms that expand affordability, strengthen tenant protections, and institutionalize the delivery of rental assistance, embedding eviction prevention as a long-term policy priority rather than an emergency response (Desmond, 2016; Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2023). Instead of pausing reform efforts during a crisis, policymakers and organizers should view the moment as the starting point for transformation across systems.

Study evidence also demonstrated how eviction filings not only depend on policy but on the cyclicality of seasons. Previous researchers concluded that eviction risk varies over the calendar year, with likely peaks in the winter and fall while dropping off in the spring, contingent on household budgeting around tax returns and expenditures based on the cultural calendar of schooling, holidays, and lifestyle (Garboden and Rosen, 2019; Desmond and Shollenberger, 2015). These seasonal findings suggest that lawmakers should consider seasonality when designing interventions and provide complementary supports during “high-risk” months when tenants are most likely to experience rent burden and thus are less likely to pay.

Also of note was that eviction filings returned to a relatively stable rate of baseline after the protections ended, resembling rates before COVID. This finding demonstrates that the moratorium served only as a time abeyance; that is, no structural changes ensued to housing's underlying drivers of eviction: high housing costs, low wages, and weak tenant protections, which continued to produce housing instability (Marcal, Fowler, & Hovmand, 2022; Hatch & Yun, 2021). These realities reinforce the urgency for lawmakers to link short-term emergency responses with more structural and lasting reforms to impact affordability and stability.

Finally, Florida's experience exemplifies similar struggles being debated elsewhere over mounting concerns of housing insecurity and eviction policies. Temporary measures such as moratoriums can achieve useful outcomes in times of crisis, but cannot replace more systemic strategies. To put a meaningful dent in the risk of eviction, state and federal governments must increase affordability in the housing supply, build meaningful tenant protections and rights, and adequately fund and deliver timely and equitable rental assistance (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2023; Stout, 2020).

4.2. Policy Imagination: Beyond Crisis-Driven Reform

The findings support the potential for a much wider imagination about what ongoing reform could be. Eviction moratoriums (maybe accompanied by some innovative structural reform) might have shifted the pendulum toward stability. The passage of successful eviction-diversion courts that institute permanent systems for rent relief and expand right-to-counsel interventions might yield from a temporary moratorium that leads to a permanent safeguard against entrenched inequities in the rental market. Rental assistance under a national housing policy might operate in the welfare-state framework (like SNAP or Medicaid) and stipulate housing security as a social right rather than a voluntary service. Lessons for Florida are that these reforms are likely to remain only temporary safeguards that do not address the structural inequalities that produced eviction in the first place.

4.3. Limitations and Policy Implications

This research article sheds light on eviction trends in the State of Florida, but it comes with some limitations. The research study only includes one state's data, which has different housing laws and tenant protections from other states. Thus, our findings are not generalizable (Hatch and Yun, 2021). In addition, the dataset captures only formal eviction filings, whereas informal or "hidden" evictions, such as cash-for-keys arrangements, unlawful lockouts, or tenants leaving under pressure from the landlord, are much more common and are disproportionately felt by low-income households and renters of color (Desmond and Shollenberger, 2015; Fowle and Fyall, 2024). Additionally, incomplete monthly records and unmeasured social and economic forces influenced our findings, like rising rents, inflation, and inconsistent federal-relief programming (Leifheit et al., 2021; Hepburn et al., 2020). Because of these limitations, our findings should be interpreted as a case study of formal eviction filings rather than a complete picture of housing instability in this period.

Nonetheless, our findings have important policy implications. Florida's experience shows that moratoria sharply reduce eviction filings in the short term but do not affect the underlying conditions for eviction. In Florida, once the protections ended, eviction filings returned to pre-pandemic levels or higher. This finding suggests that eviction moratoria are a stopgap emergency measure rather than a structural solution (Benfer et al., 2021). Rather, to be effective in preventing evictions, authorities should accompany moratoria with timely rental assistance and build a system that produces rental aid, systematically and equitably (Ananat et al., 2022; Almagro et al., 2022). Moreover, addressing structural inequalities in evictions requires an explicit equity lens; Black and Latino renters, households led by women, and families that include children are at disproportionate risk but have less access to legal protection and rental relief (Desmond et al., 2013; Desmond and Gershenson, 2017). Policies and programs must target those households through proactive outreach, increasing access to legal aid, and developing partnerships with community organizations to connect households to local resources (Benfer et al., 2020; National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022).

For housing stability to look different over the long term, states must continue allocation of public resources into affordable-housing development, stronger tenant protections, income supports such as vouchers, and broader implementation of right-to-counsel programs. Right-to-counsel programs help rebalance the power dynamics in eviction courts (Garboden and Rosen, 2019; Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2023). Ultimately, states must treat eviction prevention as a public health and equity issue, due to its strong association with homelessness, health disparities, and disrupted education (Himmelstein & Desmond, 2021; Acharya et al., 2022; Ramphal et al., 2023; U.S. Census Bureau Working Paper, 2023; Collinson et al., 2025).

5. Conclusion

In this analysis, we identified eviction filings in Florida during the period from 2019 through 2025 and illustrated how patterns changed (or did not) before, during, and after the COVID-19 eviction moratorium in Florida. These findings illustrated that filings dropped quickly during the moratorium, providing timely relief to thousands of renters, but those filings rebounded to a higher-than-pre-pandemic baseline as soon as the moratorium expired. Additionally, seasonality was a powerful and often ignored predictor of eviction filings, with noticeable spikes in filings in January and October, and drops in the spring months. These results suggest that although short-term interventions, such as moratoria, can quickly impact trajectories in the moment, these interventions do nothing to change the structural causes of evictions: high rents, low wages, limited or nonexistent tenant protections, and racialized barriers to housing access.

This research is relevant for two key reasons. First, it shows the limits of conditions-to-criteria policy approaches. That is, interventions during a crisis that are intended to be only temporary, without structural reform, only delay displacement and do not create paths to housing stability. Second, our findings contribute to a larger understanding of eviction as a housing-policy issue and a public-health and equity issue, which is cyclical, racially edited, and fed by income instability and affordability. Florida's case shows that the truncated duration of temporary elements often leaves people facing greater instability than before. Inequality, again, reproduces eviction.

Moving forward, research should continue to explore how eviction trajectories align with other elements of well-being, including employment, education, and health, and should expand to look at cross-state comparisons of how eviction is implicated in different legal frameworks and landlord protections. Policy must move from crisis and conditionally to long-term housing stability: permanent sources of affordable rental numbers, affordable rentals, roaming entitlements, strong tenant protections, and equitable provision of legal representation. Embedding eviction prevention into housing and policy sectors is a necessary outcome of work to ensure that we do not experience another episode of instability. Without these broader reforms, moratoria will remain a temporary pause in eviction activity, rather than a path to stability and equity.

Overall, this analysis cautions decision-makers against thinking that crisis-based, time-limited interventions can address the structural causes of housing insecurity. Without the codification of reforms, such as permanent subsidies, universal right-to-counsel, and expanded social housing, future moratoria will be a brief respite rather than structural change. Florida’s experience illustrates a larger lesson for the U.S. liberal welfare state and beyond: temporary measures, without institutionalization, worsen precarity and extend racial, gender, and class inequality in housing.

Although we situated our analysis in Florida, the implications from this analysis reveal a widespread issue: temporary crisis responses often offer short-term relief, but do not change the deep-set institutional pathways of inequality. Across welfare regimes, the "eviction cliff" demonstrates the dangers of emphasis on short-term solutions without providing long-term protections in housing systems. These lessons apply beyond the United States to policymakers around the world facing the nexus of housing precarity, public health, and social equity.

References

- Acharya, B., Bhatta, D., & Dhakal, C. (2022). The risk of eviction and the mental health outcomes among the U.S. adults. Preventive Medicine Reports, 29, 101981. [CrossRef]

- Almagro, M., & Orane-Hutchinson, A. (2022). JUE Insight: The determinants of the differential exposure to COVID-19 in New York City and their evolution over time. Journal of Urban Economics, 127, 103293. [CrossRef]

- Benfer, E. A., Robinson, D. B., Butler, S., Edmonds, L., Gilman, S., McKay, K., Neumann, Z., Owens, L, Steinkamp, N, and Yentel, D. 2020. The COVID-19 eviction crisis: An estimated 30–40 million people in America are at risk. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/the-covid-19-eviction-crisis-an-estimated-30-40-million-people-in-america-are-at-risk/.

- Benfer, E. A., Vlahov, D., Long, M. Y., Walker-Williams, H., Pottenger, J. L., Gonsalves, G., and Keene, D. E. 2021. Eviction, health inequity, and the spread of COVID-19: Housing policy as a primary pandemic mitigation strategy. Journal of Urban Health 98(1): 159. [CrossRef]

- Collier, R. B., and Collier, D. (2002). Framework: Critical junctures and historical legacies. In Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Collinson, R., Dutz, D., Humphries, J. E., Mader, N. S., Tannenbaum, D., & van Dijk, W. (2025). The effects of eviction on children. NBER Working Paper No. 33659. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American city. New York: Crown. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M., and Gershenson, C. (2017). Who gets evicted? Assessing individual, neighborhood, and network factors. Social Science Research 62: 362–377. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M., and Shollenberger, T. 2015. Forced displacement from rental housing: Prevalence and neighborhood consequences. Demography 52(5): 1751–1772. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M., and Gershenson, C. 2016. Housing and employment insecurity among the working poor. Social Problems 63(1): 46–67. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O. J. 1964. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics 6(3): 241–252. [CrossRef]

- Eviction Lab. 2025. Eviction filings database: Florida dataset. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. https://evictionlab.org.

- Fisher, R. A. 1925. Statistical methods for research workers. Oliver and Boyd.

- Fowle, E. R., & Fyall, R. (2024). Hidden evictions: Informal displacement in U.S. housing markets. Housing Policy Debate, 34(2), 245–268. [CrossRef]

- Garboden, P. M. E., and Rosen, E. 2019. Serial filing: How landlords use the threat of eviction. City and Community 18(2): 638–661. [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A. 2005. Analysis of variance—Why it is more important than ever. The Annals of Statistics 33(1): 1–53. [CrossRef]

- Hacker, J. S. 2004. Privatizing risk without privatizing the welfare state: The hidden politics of social policy retrenchment in the United States. American Political Science Review 98(2): 243–260. [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M. E., and Yun, J. 2021. Losing your home is bad for your health: Short- and long-term health effects of eviction on young adults. Housing Policy Debate 31(3–5): 469–489. [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, P., Louis, R., and Desmond, M. 2020. Racial and gender disparities among evicted Americans. Sociological Science 7: 649–662. [CrossRef]

- Himmelstein, G., and Desmond, M. 2021. Eviction and health: A vicious cycle exacerbated by a pandemic. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. [CrossRef]

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. 2023. America’s rental housing. February 2023 update. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/media-files/2023-02/America%27s%20Rental%20Housing_022423%20market%20update.pdf.

- Jones, B. D., and Baumgartner, F. R. 2012. From there to here: Punctuated equilibrium to the general punctuation thesis to a theory of government information processing. Policy Studies Journal 40(1): 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W. H., and Wallis, W. A. 1952. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 47(260): 583–621. [CrossRef]

- Leifheit, K. M., Linton, S. L., Raifman, J., Schwartz, G. L., Benfer, E. A., Zimmerman, F. J., and Pollack, C. E. 2021. Expiring eviction moratoriums and COVID-19 incidence and mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology 190(12): 2503–2510. [CrossRef]

- Mann, H. B., and Whitney, D. R. 1947. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 18(1): 50–60. [CrossRef]

- Marcal, K., Fowler, P. J., & Hovmand, P. S. (2022). Feedback dynamics of the low-income rental housing market: Exploring policy responses to COVID-19. arXiv Preprint, arXiv:2206.12647. [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. 2010. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference: 56–61. [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. S., McCabe, G. P., and Craig, B. A. 2017. Introduction to the practice of statistics (9th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman.

- Mumford, M. E., Erdman, S., & Smith, A. (2022). The federal eviction moratoria following COVID-19 and its effects on housing stability. University of North Carolina School of Law. UNC Law Scholarship Repository.

- National Low Income Housing Coalition. 2022. Advancing racial equity in housing. Washington, DC: NLIHC. https://nlihc.org.

- Newey, W. K., and West, K. D. 1987. A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55(3): 703–708. [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, T. E. 2006. A guide to NumPy. New York: Trelgol.

- Pierson, P. 2000a. Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review 94(2): 251–267. [CrossRef]

- Pierson, P. 2000b. Not just what, but when: Timing and sequence in political processes. Studies in American Political Development 14(1): 72–92. [CrossRef]

- Ramphal, B., Keen, R., Okuzuno, S. S., Ojogho, D., & Slopen, N. (2023). Evictions and infant and child health outcomes: A systematic review. JAMA Network Open, 6(4), e237612. [CrossRef]

- Ruxton, G. D. 2006. The unequal variance t-test is an underused alternative to Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test. Behavioral Ecology 17(4): 688–690. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. 1978. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics 6(2): 461–464. [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S., and Perktold, J. 2010. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference: 92–96. [CrossRef]

- Student. 1908. The probable error of a mean. Biometrika, 6(1): 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Thelen, K. 2000. Timing and temporality in the analysis of institutional evolution and change. Studies in American Political Development 14(1): 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J., Mares, A. S., and Rosenheck, R. A. 2022. A multisite comparison of homelessness prevention and eviction prevention programs. Psychiatric Services 73(7): 781–789. [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J. W. 1949. Comparing individual means in the analysis of variance. Biometrics 5(2): 99–114. [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, W., Humphries, J. E., Collinson, R., Mader, N., Reed, D., & Tannenbaum, D. (2023). Eviction and poverty in American cities. U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies Working Paper No. CES-WP-23-37.

- Virtanen, P., Gommers, R., Oliphant, T. E., Haberland, M., Reddy, T., Cournapeau, D., Burovski, E., Peterson, P., Weckesser, W., Bright, J., van der Walt, S. J., Brett, M., Wilson, J., Millman, K. J., Mayorov, N., Nelson, A. R. J. Jones, E., Kern, R., Larson, E., … van Mulbregt, P. 2020. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods 17: 261–272. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).