Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

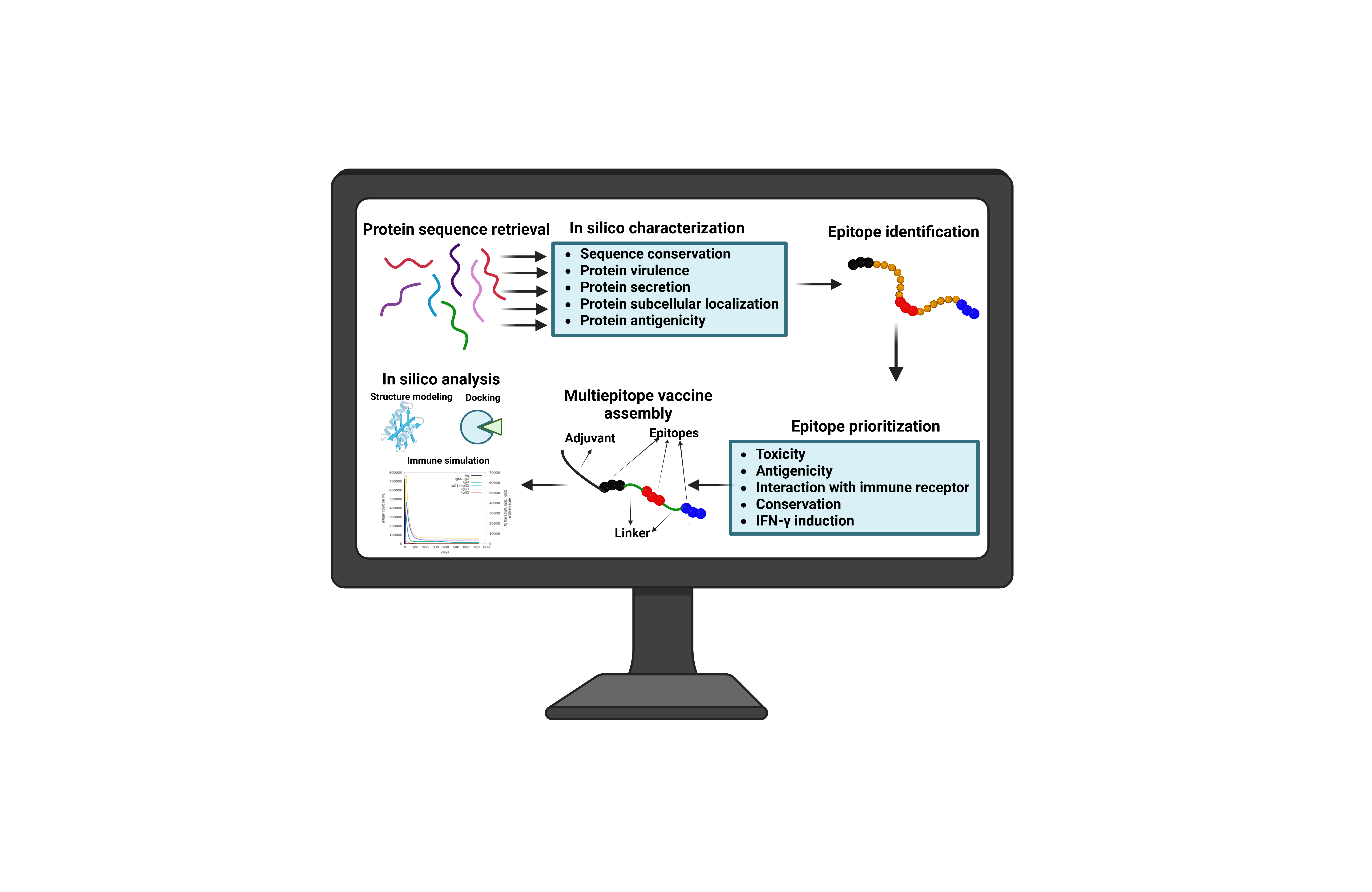

Materials and methods

Retrieval of FrpB Protein Sequences and In Silico Analysis

Epitope Selection

Antigenicity and Toxicity Prediction and Conservancy Analysis

In Silico Interferon Gamma Epitope Screening

Population Coverage Analysis

Epitope-Receptor Docking Analysis, Structure Assessment, and Binding Affinity

Construction of the Multiepitope Vaccine Construct

Secondary and 3D Structure Prediction and Validation

Physicochemical Properties and Prediction of Discontinuous B-Cell Epitopes

Vaccine-Immune Receptor Docking Analysis

Immune Simulation Kinetics

Results

Brucella FrpB: A Promising Vaccine Candidate with Multiple Key Attributes

Selected B- and T-Cell Epitopes

High Population Coverage of Selected T-Cell Epitopes in Brucellosis-Endemic Regions

Selected B- and T-Cell Epitopes Exhibit High Binding Affinity to Human Receptors

Multi-Epitope Vaccine Assembly from Diverse Epitopes

Mvax Demonstrates Superior Physicochemical Properties

Structural Modeling and Validation of Mvax Crystal Structure

ElliPro Analysis Identifies Multiple High-Scoring Conformational Epitopes

Mvax Exhibits High Binding Affinity to Immune Receptors

Three-Year Modeling Highlights Mvax’s Enhanced Th1 Memory Response

Simulation Demonstrates Mvax Enhances IgM Plasma Cells and IgM Antibody Levels

Discussion

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IEDB | Immune Epitope Database |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| MHCI | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I |

| MHCII | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| Th | T helper cell |

| FrpB | Iron-regulated outer membrane protein |

| hBD-3 | human β-defensin-3 |

| Mvax | Multiepitope vaccine construct |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte |

| HTL | Helper T Lymphocyte |

| CD4 | Cluster of Differentiation 4 (T helper cell marker) |

| CD8 | Cluster of Differentiation 8 (Cytotoxic T cell marker) |

| TLR2 | Toll-Like Receptor 2 |

| TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| TLR6 | Toll-Like Receptor 6 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| sIgM | Secretory IgM |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| BCR | B Cell Receptor |

References

- Laine, C.G.; Johnson, V.E.; Scott, H.M.; Arenas-Gamboa, A.M. Global Estimate of Human Brucellosis Incidence - Volume 29, Number 9—September 2023 - Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal - CDC. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Hôte, L.; Light, I.; Mattiangeli, V.; Teasdale, M.D.; Halpin, Á.; Gourichon, L.; Key, F.M.; Daly, K.G. An 8000 Years Old Genome Reveals the Neolithic Origin of the Zoonosis Brucella Melitensis. Nature Communications 2024, 15 15, 6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, G.; Adams, L.G.; Rice-Ficht, A.; Ficht, T.A. Host-Brucella Interactions and the Brucella Genome as Tools for Subunit Antigen Discovery and Immunization against Brucellosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2013, 4, 38949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.R.; de Almeida, J.V.F.C.; de Oliveira, I.R.C.; de Oliveira, L.F.; Pereira, L.J.; Zangerônimo, M.G.; Lage, A.P.; Dorneles, E.M.S. Occupational Exposure to Brucella Spp.: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, K.A.; Parvez, A.; Fahmy, N.A.; Abdel Hady, B.H.; Kumar, S.; Ganguly, A.; Atiya, A.; Elhassan, G.O.; Alfadly, S.O.; Parkkila, S.; et al. Brucellosis: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment–a Comprehensive Review. Ann Med 2024, 55, 2295398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbaset, A.E.; Abushahba, M.F.N.; Hamed, M.I.; Rawy, M.S. Sero-Diagnosis of Brucellosis in Sheep and Humans in Assiut and El-Minya Governorates, Egypt. Int J Vet Sci Med 2018, 6, S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanjani Roushan, M.R.; Moulana, Z.; Mohseni Afshar, Z.; Ebrahimpour, S. Risk Factors for Relapse of Human Brucellosis. Glob J Health Sci 2015, 8, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Luo, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, M.; Jia, J.; Yang, M.; Pan, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Z. Progress in Brucellosis Immune Regulation Inflammatory Mechanisms and Diagnostic Advances. Eur J Med Res 2025, 30, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zeng, H.; Li, M.; Xiao, Y.; Gu, G.; Song, Z.; Shuai, X.; Guo, J.; Huang, Q.; Zhou, B.; et al. The Mechanism of Chronic Intracellular Infection with Brucella Spp. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1129172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadelahi, A.S.; Abushahba, M.F.N.; Ponzilacqua-Silva, B.; Chambers, C.A.; Moley, C.R.; Lacey, C.A.; Dent, A.L.; Skyberg, J. Interactions between B Cells and T Follicular Regulatory Cells Enhance Susceptibility to Brucella Infection Independent of the Anti-Brucella Humoral Response. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19, e1011672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadelahi, A.S.; Lacey, C.A.; Chambers, C.A.; Ponzilacqua-Silva, B.; Skyberg, J.A. B Cells Inhibit CD4+ T Cell-Mediated Immunity to Brucella Infection in a Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II-Dependent Manner. Infect Immun 2020, 88, e00075-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenka, R.; Guirnalda, P.D.; Black, S.J.; Baldwin, C.L. B Lymphocytes Provide an Infection Niche for Intracellular Bacterium Brucella Abortus. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2012, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushahba, M.F.N.; Mohammad, H.; Thangamani, S.; Hussein, A.A.A.; Seleem, M.N. Impact of Different Cell Penetrating Peptides on the Efficacy of Antisense Therapeutics for Targeting Intracellular Pathogens. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, S.D.; Smither, S.J.; Atkins, H.S. Towards a Brucella Vaccine for Humans. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2010, 34, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas-Gamboa, A.M.; Rice-Ficht, A.C.; Fan, Y.; Kahl-McDonagh, M.M.; Ficht, T.A. Extended Safety and Efficacy Studies of the Attenuated Brucella Vaccine Candidates 16MΔvjbR and S19ΔvjbR in the Immunocompromised IRF-1 -/- Mouse Model. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2012, 19, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Soto, M.; Puerta-García, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; Pereira, J.; Solera, J. What Risk Do Brucella Vaccines Pose to Humans? A Systematic Review of the Scientific Literature on Occupational Exposure. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18, e0011889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Calderón, E.D.; Lopez-Merino, A.; Sriranganathan, N.; Boyle, S.M.; Contreras-Rodríguez, A. A History of the Development of Brucella Vaccines. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 743509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodswen, S.J.; Kennedy, P.J.; Ellis, J.T. A Guide to Current Methodology and Usage of Reverse Vaccinology towards in Silico Vaccine Discovery. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, U.S.; Sankarasubramanian, J.; Gunasekaran, P.; Rajendhran, J. Identification of Potential Antigens from Non-Classically Secreted Proteins and Designing Novel Multitope Peptide Vaccine Candidate against Brucella Melitensis through Reverse Vaccinology and Immunoinformatics Approach. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2017, 55, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.L.; Qi, X.X.; Li, R.; Luo, J.R.; Li, C.; Shi, H.D.; Tian, T.T.; Shang, K.Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Zhang, F.B. Reverse Vaccinology-Driven Construction and Bioinformatics Validation of a Multi-Epitope Vaccine against Brucella Spp. Scientific Reports 2025, 15 15, 36663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharazi, H.; Doosti, A.; Abdizadeh, R. Brucellosis Novel Multi-Epitope Vaccine Design Based on in Silico Analysis Focusing on Brucella Abortus. BMC Immunol 2025, 26, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, R.E.; Osorio, A.; Flores-Concha, M.; Gómez, L.A.; Alvarado, I.; Ferrari, I.; Oñate, A. Immunoinformatic Design of a Multivalent Vaccine against Brucella Abortus and Its Evaluation in a Murine Model Using a DNA Prime-Protein Boost Strategy. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1456078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, Z.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Haimiti, G.; Xie, X.; Niu, C.; Guo, W.; Zhang, F. In Silico Designed Novel Multi-Epitope MRNA Vaccines against Brucella by Targeting Extracellular Protein BtuB and LptD. Scientific Reports 2024, 14 14, 7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.R.; Mohammed, B.Q.; Jassim, T.S.; Alharbi, M.; Ahmad, S. Design of a Novel Multi-Epitopes Based Vaccine against Brucellosis. Inform Med Unlocked 2023, 39, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushahba, M.F.; Dadelahi, A.S.; Lemoine, E.L.; Skyberg, J.A.; Vyas, S.; Dhoble, S.; Ghodake, V.; Patravale, V.B.; Adamovicz, J.J. Safe Subunit Green Vaccines Confer Robust Immunity and Protection against Mucosal Brucella Infection in Mice. Vaccines 2023, Vol. 11 11, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abushahba, M.F.N.; Dadelahi, A.S.; Ponzilacqua-Silva, B.; Moley, C.R.; Skyberg, J.A. Contrasting Roles for IgM and B-Cell MHCII Expression in Brucella Abortus S19 Vaccine-Mediated Efficacy against B. Melitensis Infection. mSphere 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Johansen, A.R.; Gíslason, M.H.; Pihl, S.I.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 Predicts All Five Types of Signal Peptides Using Protein Language Models. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Xiong, X.; Łabaj, P.P.; Chmielarczyk, A.; Różańska, A.; Zhang, H.; Liu, K.; Shi, T.; et al. VirulentHunter: Deep Learning-Based Virulence Factor Predictor Illuminates Pathogenicity in Diverse Microbial Contexts. Brief Bioinform 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Gupta, D. VirulentPred: A SVM Based Prediction Method for Virulent Proteins in Bacterial Pathogens. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9:1 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Lin, C.; Hwang, J. Predicting Subcellular Localization of Proteins for Gram-Negative Bacteria by Support Vector Machines Based on n-Peptide Compositions. Protein Sci 2004, 13, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Nielsen, H.; Winther, O.; Teufel, F. Predicting the Subcellular Location of Prokaryotic Proteins with DeepLocPro. Bioinformatics 2024, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsirigos, K.D.; Peters, C.; Shu, N.; Käll, L.; Elofsson, A. The TOPCONS Web Server for Consensus Prediction of Membrane Protein Topology and Signal Peptides. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, W401–W407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, B.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: Improved Predictions of MHC Antigen Presentation by Concurrent Motif Deconvolution and Integration of MS MHC Eluted Ligand Data. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erik, J.; Larsen, P.; Lund, O.; Nielsen, M. Improved Method for Predicting Linear B-Cell Epitopes. Immunome Research 2006, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, J.; Sidney, J.; Chung, J.; Brander, C.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. Functional Classification of Class II Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) Molecules Reveals Seven Different Supertypes and a Surprising Degree of Repertoire Sharing across Supertypes. Immunogenetics 2011, 63, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutaftsi, M.; Peters, B.; Pasquetto, V.; Tscharke, D.C.; Sidney, J.; Bui, H.H.; Grey, H.; Sette, A. A Consensus Epitope Prediction Approach Identifies the Breadth of Murine T(CD8+)-Cell Responses to Vaccinia Virus. Nat Biotechnol 2006, 24, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotturi, M.F.; Peters, B.; Buendia-Laysa, F.; Sidney, J.; Oseroff, C.; Botten, J.; Grey, H.; Buchmeier, M.J.; Sette, A. The CD8+ T-Cell Response to Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Involves the L Antigen: Uncovering New Tricks for an Old Virus. J Virol 2007, 81, 4928–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytchinova, I.A.; Flower, D.R. VaxiJen: A Server for Prediction of Protective Antigens, Tumour Antigens and Subunit Vaccines. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kapoor, P.; Chaudhary, K.; Gautam, A.; Kumar, R.; Raghava, G.P.S. In Silico Approach for Predicting Toxicity of Peptides and Proteins. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, H.H.; Sidney, J.; Li, W.; Fusseder, N.; Sette, A. Development of an Epitope Conservancy Analysis Tool to Facilitate the Design of Epitope-Based Diagnostics and Vaccines. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.A.; Sathiyaseelan, J.; Parent, M.A.; Zou, B.; Baldwin, C.L. Interferon-γ Is Crucial for Surviving a Brucella Abortus Infection in Both Resistant C57BL/6 and Susceptible BALB/c Mice. Immunology 2001, 103, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhall, A.; Patiyal, S.; Raghava, G.P.S. A Hybrid Method for Discovering Interferon-Gamma Inducing Peptides in Human and Mouse. Scientific Reports 2024, 14 14, 26859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.H.; Sidney, J.; Dinh, K.; Southwood, S.; Newman, M.J.; Sette, A. Predicting Population Coverage of T-Cell Epitope-Based Diagnostics and Vaccines. BMC Bioinformatics 2006, 7:1 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Chen, Q.; Li, Z. Human Brucellosis: An Ongoing Global Health Challenge. China CDC Wkly 2021, 3, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamiable, A.; Thevenet, P.; Rey, J.; Vavrusa, M.; Derreumaux, P.; Tuffery, P. PEP-FOLD3: Faster de Novo Structure Prediction for Linear Peptides in Solution and in Complex. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakov, D.; Hall, D.R.; Xia, B.; Porter, K.A.; Padhorny, D.; Yueh, C.; Beglov, D.; Vajda, S. The ClusPro Web Server for Protein–Protein Docking. Nature Protocols 2017, 12, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Chen, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, G.; Huang, B.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Y. Cryo-EM Structure of the Human IgM B Cell Receptor. Science (1979), 377, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, C.S.; Gorski, J.; Stern, L.J. Crystallographic Structure of the Human Leukocyte Antigen DRA, DRB3*0101: Models of a Directional Alloimmune Response and Autoimmunity. J Mol Biol 2007, 371, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, C.; Dubnovitsky, A.; Sandin, C.; Kozhukh, G.; Uchtenhagen, H.; James, E.A.; Rönnelid, J.; Ytterberg, A.J.; Pieper, J.; Reed, E.; et al. Functional and Structural Characterization of a Novel HLA-DRB1*04: 01-Restricted α-Enolase T Cell Epitope in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 224418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Studer, G.; Robin, X.; Bienert, S.; Tauriello, G.; Schwede, T. The Structure Assessment Web Server: For Proteins, Complexes and More. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W318–W323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.C.; Rodrigues, J.P.; Kastritis, P.L.; Bonvin, A.M.; Vangone, A. PRODIGY: A Web Server for Predicting the Binding Affinity of Protein–Protein Complexes. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3676–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Youkharibache, P.; Zhang, D.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Geer, R.C.; Madej, T.; Phan, L.; Ward, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; et al. ICn3D, a Web-Based 3D Viewer for Sharing 1D/2D/3D Representations of Biomolecular Structures. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Youkharibache, P.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Lanczycki, C.; Zhang, D.; Lu, S.; Madej, T.; Marchler, G.H.; Cheng, T.; Chong, L.C.; et al. ICn3D: From Web-Based 3D Viewer to Structural Analysis Tool in Batch Mode. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zaro, J.L.; Shen, W.C. Fusion Protein Linkers: Property, Design and Functionality. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012, 65, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, B.; Crimi, C.; Newman, M.; Higashimoto, Y.; Appella, E.; Sidney, J.; Sette, A. A Rational Strategy to Design Multiepitope Immunogens Based on Multiple Th Lymphocyte Epitopes. The Journal of Immunology 2002, 168, 5499–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahlou, R.; Farajnia, S.; Bargahi, N.; Bakhtiyari, N.; Elmi, F.; Shahgolzari, M.; Fiering, S.; Venkataraman, S. Development of a Novel Multi-epitope Vaccine against the Pathogenic Human Polyomavirus V6/7 Using Reverse Vaccinology. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, L.K.; Mburu, Y.K.; Mathers, A.R.; Fluharty, E.R.; Larregina, A.T.; Ferris, R.L.; Falo, L.D. Human Beta-Defensin 3 Induces Maturation of Human Langerhans Cell-like Dendritic Cells: An Antimicrobial Peptide That Functions as an Endogenous Adjuvant. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2013, 133, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geourjon, C.; Deléage, G. SOPMA: Significant Improvements in Protein Secondary Structure Prediction by Consensus Prediction from Multiple Alignments. Comput Appl Biosci 1995, 11, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combet, C.; Blanchet, C.; Geourjon, C.; Deléage, G. NPS@: Network Protein Sequence Analysis. Trends Biochem Sci 2000, 25, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Su, H.; Wang, W.; Ye, L.; Wei, H.; Peng, Z.; Anishchenko, I.; Baker, D.; Yang, J. The TrRosetta Server for Fast and Accurate Protein Structure Prediction. Nat Protoc 2021, 16, 5634–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederstein, M.; Sippl, M.J. ProSA-Web: Interactive Web Service for the Recognition of Errors in Three-Dimensional Structures of Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Park, H.; Heo, L.; Seok, C. GalaxyWEB Server for Protein Structure Prediction and Refinement. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colovos, C.; Yeates, T.O. Verification of Protein Structures: Patterns of Nonbonded Atomic Interactions. Protein Sci 1993, 2, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Gattiker, A.; Hoogland, C.; Ivanyi, I.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. ExPASy: The Proteomics Server for in-Depth Protein Knowledge and Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31, 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.N.; Krutz, N.L.; Limviphuvadh, V.; Lopata, A.L.; Gerberick, G.F.; Maurer-Stroh, S. AllerCatPro 2.0: A Web Server for Predicting Protein Allergenicity Potential. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, W36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebditch, M.; Carballo-Amador, M.A.; Charonis, S.; Curtis, R.; Warwicker, J. Protein–Sol: A Web Tool for Predicting Protein Solubility from Sequence. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, J.; Bui, H.H.; Li, W.; Fusseder, N.; Bourne, P.E.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. ElliPro: A New Structure-Based Tool for the Prediction of Antibody Epitopes. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.S.; Song, D.H.; Kim, H.M.; Choi, B.S.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.O. The Structural Basis of Lipopolysaccharide Recognition by the TLR4–MD-2 Complex. Nature 2009, 458, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.Y.; Nan, X.; Jin, M.S.; Youn, S.J.; Ryu, Y.H.; Mah, S.; Han, S.H.; Lee, H.; Paik, S.G.; Lee, J.O. Recognition of Lipopeptide Patterns by Toll-like Receptor 2-Toll-like Receptor 6 Heterodimer. Immunity 2009, 31, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Gu, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z. Brucella Infection and Toll-like Receptors. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1342684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubenbacher, R.; Adler, F.; An, G.; Castiglione, F.; Eubank, S.; Fonseca, L.L.; Glazier, J.; Helikar, T.; Jett-Tilton, M.; Kirschner, D.; et al. Toward Mechanistic Medical Digital Twins: Some Use Cases in Immunology. Front Digit Health 2024, 6, 1349595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapin, N.; Lund, O.; Bernaschi, M.; Castiglione, F. Computational Immunology Meets Bioinformatics: The Use of Prediction Tools for Molecular Binding in the Simulation of the Immune System. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, E.; Cooke, M.F.; Huffman, A.; Xiang, Z.; Wong, M.U.; Wang, H.; Seetharaman, M.; Valdez, N.; He, Y. Vaxign2: The Second Generation of the First Web-Based Vaccine Design Program Using Reverse Vaccinology and Machine Learning. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W671–W678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulley, J.T.; Anderson, E.S.; Roop, R.M. Brucella Abortus Requires the Heme Transporter BhuA for Maintenance of Chronic Infection in BALB/c Mice. Infect Immun 2007, 75, 5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Caldern, E.D.; Lopez-Merino, A.; Jain, N.; Peralta, H.; Lpez-Villegas, E.O.; Sriranganathan, N.; Boyle, S.M.; Witonsky, S.; Contreras-Rodríguez, A. Characterization of Outer Membrane Vesicles from Brucella Melitensis and Protection Induced in Mice. J Immunol Res 2012, 2012, 352493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Fasihi-Ramandi, M.; Bouzari, S. Brucella Antigens (BhuA, 7α-HSDH, FliC) in Poly I:C Adjuvant as Potential Vaccine Candidates against Brucellosis. J Immunol Methods 2022, 500, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Shankar, U.; Majee, P.; Kumar, A. Scrutinizing the SARS-CoV-2 Protein Information for Designing an Effective Vaccine Encompassing Both the T-Cell and B-Cell Epitopes. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 87, 104648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri-Rachman, E.A.; Kurnianti, A.M.F.; Rizarullah; Setyadi, A.H.; Artarini, A.; Tan, M.I.; Riani, C.; Natalia, D.; Aditama, R.; Nugrahapraja, H. An Immunoinformatics Approach in Designing High-Coverage MRNA Multi-Epitope Vaccine against Multivariant SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology 2025, 23, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolla, H.B.; Tirumalasetty, C.; Sreerama, K.; Ayyagari, V.S. An Immunoinformatics Approach for the Design of a Multi-Epitope Vaccine Targeting Super Antigen TSST-1 of Staphylococcus Aureus. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2021, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocha, N.; Laubreton, D.; Robert, X.; Marvel, J.; Gueguen-Chaignon, V.; Gouet, P.; Kumar, P.; Khanna, M. Unveiling a Shield of Hope: A Novel Multiepitope-Based Immunogen for Cross-Serotype Cellular Defense against Dengue Virus. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, Z.; Shafaghi, M.; Madanchi, H.; Ranjbar, M.M.; Shabani, A.A.; Mousavi, S.F. In Silico Designing of a Novel Epitope-Based Candidate Vaccine against Streptococcus Pneumoniae with Introduction of a New Domain of PepO as Adjuvant. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022, 20, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y.L.; Ai, S.M.; Liang, J.; Sang, P.; Ji, X.L.; Liu, S.Q. Insights into Protein–Ligand Interactions: Mechanisms, Models, and Methods. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puagsopa, J.; Jumpalee, P.; Dechanun, S.; Choengchalad, S.; Lohasupthawee, P.; Sutjaritvorakul, T.; Meksiriporn, B. Development of a Broad-Spectrum Pan-Mpox Vaccine via Immunoinformatic Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, P.; Dang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, B.; Yang, M. Dynamic Changes of Th1 Cytokines and the Clinical Significance of the IFN-γ/TNF-α Ratio in Acute Brucellosis. Mediators Inflamm 2019, 2019, 5869257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendros, P.; Pappas, G.; Boura, P. Cell-Mediated Immunity in Human Brucellosis. Microbes Infect 2011, 13, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziato, F.; Romagnani, S. Heterogeneity of Human Effector CD4+ T Cells. Arthritis Res Ther 2009, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Fasihi-Ramandi, M.; Bouzari, S. Evaluation of Immunogenicity of Novel Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccines in Combination with Poly I:C against Brucella Melitensis and Brucella Abortus Infection. Int Immunopharmacol 2019, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandão, A.P.M.S.; Oliveira, F.S.; Carvalho, N.B.; Vieira, L.Q.; Azevedo, V.; MacEdo, G.C.; Oliveira, S.C. Host Susceptibility to Brucella Abortus Infection Is More Pronounced in IFN-γ Knockout than IL-12/Β2-Microglobulin Double-Deficient Mice. J Immunol Res 2012, 2012, 589494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewary, P.; de la Rosa, G.; Sharma, N.; Rodriguez, L.G.; Tarasov, S.G.; Howard, O.M.Z.; Shirota, H.; Steinhagen, F.; Klinman, D.M.; Yang, D.; et al. β-Defensin 2 and 3 Promote the Uptake of Self or CpG DNA, Enhance IFN-α Production by Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells, and Promote Inflammation. The Journal of Immunology 2013, 191, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lei, X.; Chai, S.; Zhang, S.; Su, G.; Du, L. A Multi-Epitope Vaccine Incorporating Adhesin-Derived Antigens Protects against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection and Dissemination. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1707471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgwi, S.A.; Adeleke, V.T.; Adeleke, M.A.; Okpeku, M. Multi-Epitope Based Peptide Vaccine Candidate Against Babesia Infection From Rhoptry-Associated Protein 1 (RAP-1) Antigen Using Immuno-Informatics: An In Silico Approach. Bioinform Biol Insights 2024, 18, 11779322241287114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, D.D. In Silico Vaccine Design: A Tutorial in Immunoinformatics. Healthcare Analytics 2022, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cheers, C. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha and Interleukin-12 Contribute to Resistance to the Intracellular Bacterium Brucella Abortus by Different Mechanisms. Infect Immun 1996, 64, 2782–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, D.W.; Goodwin, Z.I.; Bhagyaraj, E.; Hoffman, C.; Yang, X. Activation of Mucosal Immunity as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Combating Brucellosis. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1018165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avijgan, M.; Rostamnezhad, M.; Jahanbani-Ardakani, H. Clinical and Serological Approach to Patients with Brucellosis: A Common Diagnostic Dilemma and a Worldwide Perspective. Microb Pathog 2019, 129, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís García del Pozo, J.; Lorente Ortuño, S.; Navarro, E.; Solera, J. Detection of IgM Antibrucella Antibody in the Absence of IgGs: A Challenge for the Clinical Interpretation of Brucella Serology. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, e3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Residue position (start-end) | Epitope Sequence | Epitope type | Conservancy % | Vaxijen score | IFNepitope2 score | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 179-194 | YGTNGRGFSGSTAAYG | B-cell | 100 | 1.54 | - | Non-Toxin |

| 209-229 | SGHNYKNGDGTEILGTEPAAR | B-cell | 100 | 1.61 | - | Non-Toxin |

| 412-420 | ASVNGTLSY | MHCI | 100 | 1.08 | 0.64 | Non-Toxin |

| 53-61 | ATGGTVLTY | MHCI | 100 | 1.12 | 0.82 | Non-Toxin |

| 23-37 | AQEVKRDTKKQGEVV | MHCII | 100 | 1.11 | 0.57 | Non-Toxin |

| 278-292 | DSVNIKYTRTDATDM | MHCII | 100 | 1.31 | 0.5 | Non-Toxin |

| 303-317 | RNDYWRNDYQNRTNG | MHCII | 100 | 0.77 | 0.52 | Non-Toxin |

| Epitope Sequence | Predicted binding alleles |

|---|---|

| ASVNGTLSY | HLA-A*30:02, HLA-B*15:01, HLA-A*01:01, HLA-A*26:01, HLA-A*11:01, HLA-B*58:01, HLA-B*35:01, HLA-A*32:01, HLA-B*57:01, HLA-A*03:01 |

| ATGGTVLTY | HLA-A*30:02, HLA-A*01:01, HLA-A*11:01, HLA-A*32:01, HLA-B*15:01, HLA-A*26:01, HLA-B*58:01, HLA-A*03:01, HLA-B*57:01, HLA-B*35:01 |

| AQEVKRDTKKQGEVV | HLA-DRB1*03:01, HLA-DRB1*13:02, HLA-DRB1*11:01, HLA-DRB1*08:02, HLA-DRB3*01:01 |

| DSVNIKYTRTDATDM | HLA-DRB4*01:01, HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DRB1*07:01, HLA-DQA1*04:01, HLA-DQB1*04:02, HLA-DRB1*09:01, HLA-DRB1*04:05, HLA-DRB1*08:02, HLA-DQA1*05:01, HLA-DQB1*02:01, HLA-DQA1*03:01, HLA-DQB1*03:02 |

| RNDYWRNDYQNRTNG | HLA-DRB3*01:01, HLA-DRB3*02:02, HLA-DRB1*03:01, HLA-DRB1*13:02, HLA-DPA1*01:03, HLA-DPB1*02:01, HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DPB1*04:01 |

| Ligand | Human receptor | Top Model ClusPro cluster size |

SWISS-MODEL structure assessment | PRODIGY binding affinity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | PDB code | MolProbity Score | Ramachandran favored | Ramachandran outliers | QMEANDisCo Global | ΔG (kcal mol-1) |

Kd (M) at 37 ℃ | ||

| YGTNGRGFSGSTAAYG | Crystal structure of human B-cell antigen receptor of the IgM isotype | 7XQ8 | 333 | 3.20 | 92.76% | 0.58% | 0.71±0.05 | -11.6 | 6.5 × 10⁻⁹ |

| SGHNYKNGDGTEILGTEPAAR | Crystal structure of human B-cell antigen receptor of the IgM isotype | 7XQ8 | 308 | 3.20 | 92.62% | 0.74% | 0.70±0.05 | -8.1 | 2 × 10⁻⁶ |

| AQEVKRDTKKQGEVV | Crystal structure of MHCII allele HLA-DRA, DRB3*0101 | 2Q6W | 292 | 2.97 | 93.68% | 0.66% | 0.83±0.05 | -13.0 | 6.7 × 10⁻¹⁰ |

| DSVNIKYTRTDATDM | Crystal structure of MHCII allele HLA-DRB1*04:01 | 5JLZ | 171 | 2.35 | 96.60% | 0.39% | 0.86±0.05 | -11.0 | 1.8 × 10⁻⁸ |

| RNDYWRNDYQNRTNG | Crystal structure of MHCII allele HLA-DRA, DRB3*0101 | 2Q6W | 282 | 2.95 | 93.95% | 0.53% | 0.83±0.05 | -12.8 | 9.5 × 10⁻¹⁰ |

| Predicted score | FrpB | MAvax |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | 72932.84 | 18701.86 |

| Theoretical pI | 5.71 | 9.63 |

| Instability index | 31.12 | 27.86 |

| Aliphatic index | 66.19 | 49.20 |

| GRAVY index | -0.486 | -0.881 |

| Scaled solubility score | 0.275 | 0.808 |

| Vaxijen score | 0.602 | 1.06 |

| Allergenicity | Non-allergenic | Non-allergenic |

| Estimated half-life | 30 hours (mammalian reticulocytes, in vitro). >20 hours (yeast, in vivo). >10 hours (Escherichia coli, in vivo) |

30 hours (mammalian reticulocytes, in vitro). >20 hours (yeast, in vivo). >10 hours (Escherichia coli, in vivo) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).