1. Introduction

The physical nature of the vacuum lies at the foundation of modern theoretical physics. Quantum field theory assigns a non-vanishing zero-point energy to every mode of a quantum field, and naive summation over all modes up to arbitrarily high frequencies leads to a formally divergent vacuum energy density. When a high-energy cutoff is introduced at the Planck scale, the resulting vacuum energy density exceeds the observed cosmological value by many orders of magnitude. This mismatch, often referred to as the cosmological constant problem, indicates that our present understanding of vacuum energy is incomplete and that additional physical structure or constraints may be required.

A related set of questions arises in the context of black holes. Within classical general relativity, gravitational collapse leads to the formation of a spacetime singularity inside the event horizon. At such a singularity, curvature invariants diverge and the classical description breaks down. It is generally expected that quantum effects or new high-energy physics should resolve these singularities, but the precise mechanism remains unknown. Many proposals have been put forward, including regular black hole models, effective matter sources that soften the interior, and scenarios in which quantum gravity replaces the singular core by a finite, high-density region. A common feature of these ideas is that they attribute an important role to the behaviour of matter and vacuum energy under extreme conditions.

In earlier work a phenomenological framework was introduced in which the vacuum energy is not determined by an ultraviolet cutoff at the Planck scale, but instead is effectively bounded by hadronic physics and thermal processes at much lower energies. Within this Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) picture, vacuum fluctuations are constrained between an upper scale associated with QCD confinement and a lower scale related to thermal freeze-out of hadronic degrees of freedom in the early universe. Between these scales, the vacuum acquires a finite, structured energy density that can, in principle, influence both cosmological dynamics and the behaviour of compact objects.

The aim of the present paper is to explore the implications of a QCD-bounded vacuum structure for black hole interiors. We consider, at a qualitative level, how a vacuum that is limited by QCD-scale physics might alter the effective energy content and equation of state in the deep interior of a black hole. In particular, we investigate whether such a bounded vacuum can support non-singular core configurations while leaving the exterior spacetime well approximated by standard general relativity. The analysis is intentionally phenomenological and does not rely on a specific underlying quantum gravity theory; instead, it is intended to identify the main physical ingredients that link hadronic physics, vacuum structure and black hole geometry.

Scope and structure of this work.

We restrict attention to the high-energy, QCD-dominated sector of the bounded vacuum spectrum, which is most relevant for gravitational collapse and the interior region of astrophysical black holes. The cosmological, low-energy implications of the QEV framework have been discussed elsewhere. In the present article we first review the basic elements of a QCD-bounded vacuum and its thermodynamic motivation. We then construct an effective model for black hole interiors in which the central singularity is replaced by a finite-density core supported by the bounded vacuum. Finally, we discuss the physical plausibility and limitations of this scenario and outline possible directions for more detailed theoretical investigations.

2. Bounded Vacuum and the QCD Scale

In the Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) framework the physical vacuum is not a featureless background but a medium with a finite energy band. At low energies, vacuum fluctuations are thermally suppressed as hadronic matter freezes out of the vacuum; at high energies, the spectrum is bounded by the QCD confinement scale, beyond which colored degrees of freedom cannot exist as asymptotic states. This differs from the conventional view in which vacuum modes extend to arbitrarily high frequencies and give rise to ultraviolet divergences[

19,

30]. In the QEV picture, the vacuum spectrum is restricted to a finite interval[

17,

18].

2.1 Physical Bounds from QCD

The upper bound of the vacuum spectrum arises from the QCD confinement scale. Coloured excitations are restricted to wavelengths larger than the confinement distance,

corresponding to a characteristic energy scale

At temperatures near the QCD crossover, lattice QCD and heavy–ion data indicate a transition to deconfined quark–gluon matter[

23,

31]:

Above this temperature, additional energy primarily increases the number of degrees of freedom rather than the temperature. This is the modern understanding of the Hagedorn limit[

23]. The hadronic partition function grows exponentially,

leading to a limiting temperature,

2.2 Finite Vacuum Spectrum

In the QEV model, the admissible vacuum modes lie in the interval

where the lower limit is set by thermal freeze–out of hadronic degrees of freedom:

1

Because the allowed spectrum is finite, the vacuum energy density becomes intrinsically bounded,

which is finite as long as the spectral density

does not diverge at the endpoints. This stands in contrast to the quartic divergence

which appears in conventional unbounded vacuum models.

In this black-hole context, the lower bound

should be understood as the QCD-scale freeze-out threshold

, distinct from the much lower infrared bound used in the cosmological applications of the QEV model [

17,

18].

2.3 Application to Black-Hole Interiors

If the interior of a black hole forms a quark–gluon core governed by QCD thermodynamics, then the core temperature remains bounded by

even as energy is accreted. Additional energy increases the entropy rather than the temperature,

and hence enlarges the information horizon according to the Bekenstein–Hawking relation,

Thus the horizon grows while the internal thermodynamic variables remain bounded by QCD. This provides a physical mechanism by which black holes absorb energy without developing divergent temperatures or singular behavior. The bounded vacuum spectrum of the QEV model, therefore, aligns naturally with both QCD microphysics and black–hole thermodynamics.

3. Black-Hole Interiors and the Information Horizon

If the vacuum spectrum is bounded by QCD physics in the effective sense described above, then the interior of a black hole cannot collapse to arbitrarily small volumes or infinite temperatures [

11,

23,

31]. The resulting core forms a high-density, high-entropy phase governed by strong interactions.

3.1. Bounded Temperature and Internal Thermodynamics

Because the QGP exhibits a limiting temperature near the Hagedorn value

,

further energy added to the core increases the entropy rather than the temperature,

Thus the thermodynamic evolution is entropy–dominated:

- T does not diverge,

- S increases linearly with accreted energy,

- the information content of the core increases.

This behavior prevents the formation of a singular curvature or a divergent energy density.

The core temperature approaches a limiting value of order the QCD (Hagedorn) temperature, .

It is important to stress that this “limiting temperature” should be understood in an effective sense. In lattice simulations and heavy–ion experiments, QCD matter can attain temperatures somewhat above the nominal Hagedorn scale, but in this regime additional energy predominantly feeds entropy production and an increase in the number of active degrees of freedom rather than a simple monotonic rise of

T [

31]. In the present work we idealize this behavior by treating the Hagedorn regime as an effective limiting band for the core temperature, which is sufficient for our phenomenological argument that the interior thermodynamic variables remain finite.

3.2. Growth of the Information Horizon

The increase of entropy in the QCD core directly determines the growth of the horizon area via the Bekenstein–Hawking relation,

Thus, as accreted energy feeds the gluonic degrees of freedom inside the core, the information horizon expands in response to the rising entropy rather than to unbounded temperature growth.

A crucial point is that this behavior is not merely a thermodynamic consequence, but a self-consistent dynamical mechanism. At high energy densities, gluon interactions drive the system toward the Hagedorn regime, where additional energy no longer raises the temperature but instead increases the number of available color degrees of freedom,

As entropy grows, the horizon area must increase accordingly to encode this enlarged set of microstates.

This establishes a tight coupling:

limiting temperature.

The existence of an effective limiting temperature is therefore not an independent assumption but emerges naturally from the combined action of QCD microphysics and horizon thermodynamics. This provides an additional and independent support for the QEV framework: the bounded vacuum spectrum is mirrored by a bounded thermodynamic response in the interior, enforced jointly by gluon dynamics and the information-theoretic nature of the event horizon.

3.3. Absence of Singularities

In the QEV scenario, gravitational collapse does not drive the interior of a black hole toward arbitrarily large energy densities and curvatures. Instead, the combination of a bounded vacuum spectrum and a QCD–dominated equation of state allows the formation of a finite, high–density quark–gluon–plasma (QGP) core. The gravitational field responds not to a divergent energy density, but to the finite stress–energy tensor of strongly interacting matter. In this sense, the classical curvature singularity of general relativity is replaced by a regular, thermodynamically rich interior.

From the perspective of the Hawking–Penrose singularity theorems [

21,

29], this behavior can be interpreted as a controlled relaxation of the underlying assumptions. The classical theorems rely on (i) specific energy conditions, in particular the strong energy condition (SEC), and (ii) focusing arguments for geodesic congruences in an idealized matter model, typically a perfect fluid with a simple equation of state. In the QEV framework, neither ingredient remains unchanged. The strongly interacting QCD core develops an effective equation of state that is much softer than that of a classical pressureless fluid, and the bounded vacuum spectrum prevents the formation of arbitrarily large curvature invariants. Within such an effective description, the conditions that guarantee geodesic incompleteness in the classical proofs need not be satisfied in the high–density regime, so that the theorems no longer force the appearance of a curvature singularity.

Operationally, the QEV model imposes a maximal effective energy density for the interior core,

so that no region of spacetime can exceed the QCD-scale bound (see Appendix B for numerical estimates). Curvature invariants constructed from the Riemann tensor are then limited by this scale. Schematically one may write

which emphasizes that the maximal curvature is set by the QCD energy density rather than by any Planck-scale divergence.

This does not constitute a global proof that all collapse histories are non–singular, but it does provide an explicit class of interior configurations in which the endpoint of collapse is a finite–density QGP core with bounded curvature, consistent with the QEV assumptions.

Softening and possible violation of the Strong Energy Condition.

The classical Hawking–Penrose singularity theorems rely on the strong energy condition

together with appropriate global and causal assumptions that ensure geodesic focusing. In many simple matter models, such as dust (

) or radiation (

), the SEC is automatically satisfied. High–density QCD matter near the confinement transition, however, exhibits a soft, non–conformal equation of state that can substantially modify the combination

relevant for the focusing theorems.

A convenient parametrization is

so that

Lattice QCD results show that, in the crossover region, the equation of state deviates strongly from the conformal limit. The trace anomaly becomes large and the pressure remains well below

, which substantially weakens the strong energy condition (SEC) term

in the Raychaudhuri equation. We emphasize that this work relies only on these robust, non-conformal features of the QCD equation of state.

In particular, one typically finds

implying

and a significant departure from conformality. In such regimes the SEC combination

remains positive, but the prefactor

is appreciably reduced compared to the dust or radiation cases.

More speculative effective descriptions and supercooled phases of QCD matter have been discussed in the literature in which

corresponding to a genuine violation of the SEC in part of the effective phase diagram. In the present work we do not require such phases to be generically realized in realistic black-hole interiors. Our conclusions rely only on the robust fact that QCD matter near the transition is strongly non-conformal and can substantially reduce—and in some effective models even reverse—the effective SEC contribution

.

Implications for geodesic focusing.

The impact of SEC softening or violation on geodesic focusing is captured by the Raychaudhuri equation [

21,

29] for a congruence of timelike geodesics with tangent vector

and expansion

. For such a congruence one has

where

is the shear tensor,

is the vorticity tensor, and

is proper time. For an irrotational congruence with negligible vorticity this reduces to

where

. In the classical singularity theorems, the SEC condition (

3) guarantees that the last term is non–positive and thus enhances the focusing of geodesics, driving

toward

in finite proper time under suitable conditions.

In a QCD–dominated interior described by a soft or supercooled effective equation of state, the combination

can be strongly suppressed and, in some models, can become negative in parts of the relevant phase diagram. In such regimes the contribution

in the Raychaudhuri equation (

9) is reduced and may even change sign. As a result, the classical focusing mechanism is weakened or delayed, and the strict conditions that enforce geodesic incompleteness in the Hawking–Penrose proofs are no longer met in the same way. When this softened focusing behavior is combined with the QEV–imposed upper bound on the energy density and curvature, the interior evolution can plausibly settle into a finite–density QGP core rather than continue toward arbitrarily increasing curvature.

A simple constant-density QCD core.

To make the foregoing discussion more explicit, we consider a minimal interior model that shows how a QCD–bounded energy density leads to a regular, non–singular core. The construction follows the standard constant-density toy model, but with the density fixed at the QCD scale, consistent with the QEV framework.

A fully worked-out TOV solution for such a constant-density QCD core, including numerical values for the core radius, mass and curvature, is presented in Appendix F.

We assume a static, spherically symmetric interior with line element

and take the core to be filled with high-density QCD matter at a uniform energy density

where

represents the maximal energy density attainable by the quark–gluon plasma before confinement and hadronization set in. In the QEV picture this density is naturally of order

as discussed in Appendix B.

With the assumption (

11), the interior mass function is

so that the radial metric coefficient becomes

As long as the core radius satisfies

the interior metric is regular and free of coordinate singularities. In particular, for parameter ranges in which

lies inside its Schwarzschild radius

(with

), the constant-density core describes a regular region hidden behind an event horizon, compatible with a black-hole configuration.

The curvature induced by this QCD–bounded core can be quantified via the Kretschmann scalar,

For a static, spherically symmetric metric of the form (

10) with mass function

, one can write

where

collects the terms that depend algebraically on the energy density (and pressure). In the present constant-density core,

so that

where

is a finite numerical constant of order unity. The precise value of

is irrelevant for the physical argument: what matters is that the scaling

holds and therefore remains finite for any finite

. The matter contribution has the same schematic form,

so that the total Kretschmann scalar can be written compactly as

with

a finite, dimensionful constant determined by the QCD-dominated equation of state. In particular, at the centre of the core we obtain

which is manifestly finite as long as

is finite.

For a concrete numerical estimate of the Kretschmann scalar at the centre of a QCD core, see Appendix F.

The constant-density core used in this section should be regarded as a minimal existence proof of a regular interior solution with a QCD-bounded density. It shows that once the energy density is limited by , all curvature invariants remain finite throughout the core. More realistic TOV solutions based on the full finite-temperature QCD equation of state are expected to modify the detailed radial profiles of and , but they are not required for the qualitative conclusion that a QCD-bounded interior avoids classical curvature singularities. A technical derivation of the constant-density solution is provided in Appendix E.5.

Identifying

with the QCD-scale density

estimated in Appendix B, we see that the maximum curvature in the interior is set by the QCD–limited energy density rather than by any Planck-scale divergence. This simple constant-density solution therefore provides an explicit example of the general QEV mechanism: once vacuum and matter excitations are spectrally bounded by QCD, the resulting black-hole interior is a finite-density, finite-curvature quark–gluon core instead of a classical singularity. A more detailed derivation of this constant-density interior solution, including the full Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff equation and explicit curvature invariants, is provided in Appendix E.5; see also

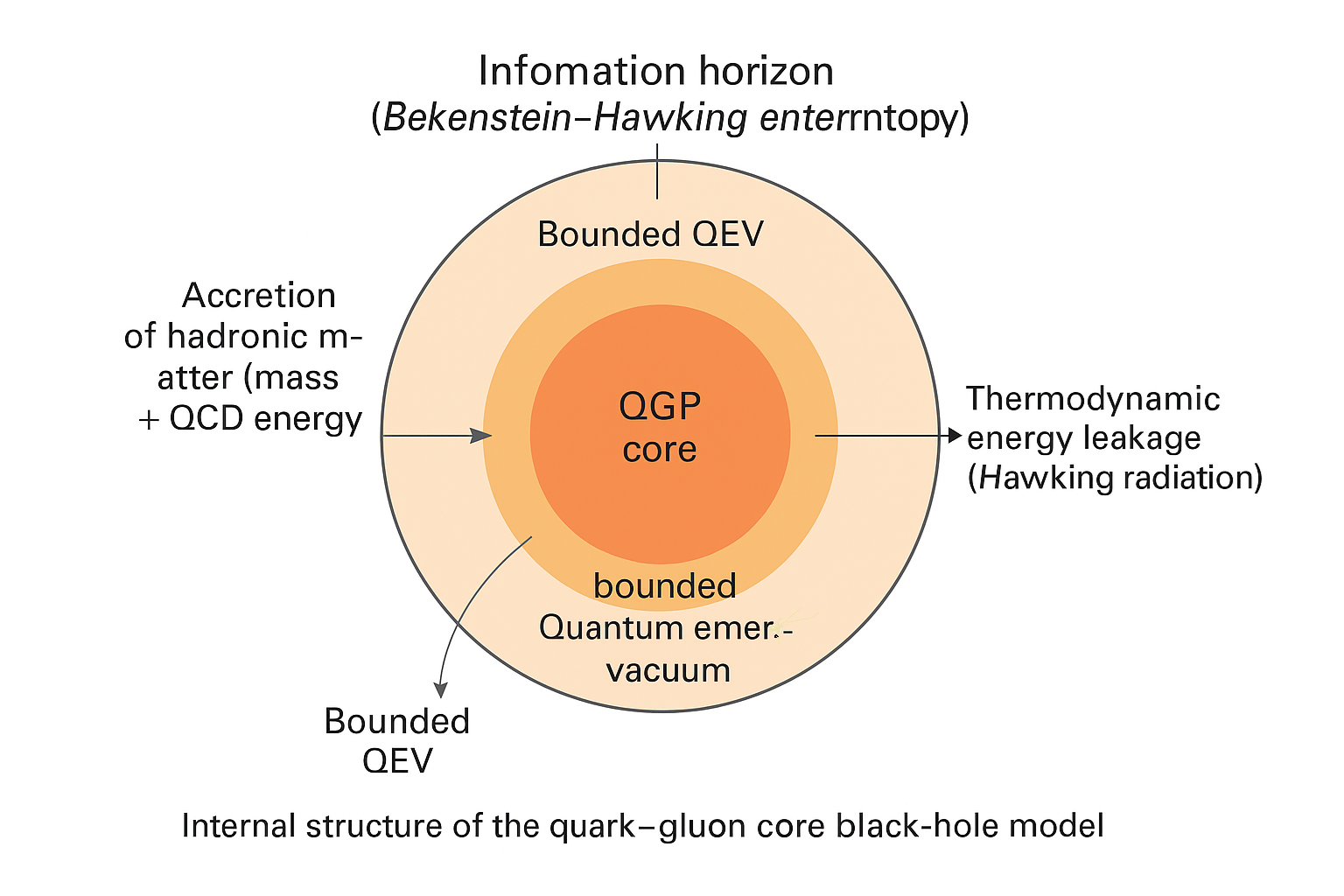

Figure 1 for a schematic overview of the internal structure.

A technical derivation of the constant-density solution is provided in Appendix E.5.

A more detailed derivation is provided in Appendix E.5; see also Figure 1 3.4. Black Holes as Thermodynamic, Information-Preserving Systems

With energy converted mainly into entropy rather than temperature, black holes become information-storing systems consistent with the holographic principle.

The QEV–QCD bounded structure provides: a maximum internal temperature,

- a maximum internal energy density,

- a natural horizon–entropy mechanism,

- a non-singular collapse endpoint,

- and compatibility with quantum–gravitational thermodynamics[

5,

14,

15,

29].

This suggests a connection between vacuum structure, QCD microphysics and black-hole thermodynamics in a single bounded framework.

3.5. Relation to Other Black–Hole Interior Models

It is instructive to contrast the QEV-based quark–gluon core with several existing non-singular interior proposals. While all these models aim to resolve curvature divergences, they do so through fundamentally different mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Internal structure of the quark–gluon core black-hole model. The central region is a finite, thermodynamically stable quark–gluon plasma (QGP) core, where hadronic matter is fully deconfined. Surrounding this core, the physical vacuum is described by the Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) framework, with fluctuations restricted to a finite spectral interval bounded above by the QCD confinement scale and bounded below by a thermal transition scale associated with hadronic matter formation. The event horizon functions as an information horizon: its surface area reflects the entropy of the microscopic degrees of freedom stored in the core. Accreting hadronic matter increases the internal QCD energy, heats the core and expands the horizon, whereas quantum fluctuations at the horizon permit a slow leakage of internal energy interpreted as Hawking radiation. At late stages, when accretion becomes negligible and the core temperature approaches the QCD critical value, a confinement-driven phase transition may reorganize internal energy and produce signatures on galactic scales.

Figure 1.

Internal structure of the quark–gluon core black-hole model. The central region is a finite, thermodynamically stable quark–gluon plasma (QGP) core, where hadronic matter is fully deconfined. Surrounding this core, the physical vacuum is described by the Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) framework, with fluctuations restricted to a finite spectral interval bounded above by the QCD confinement scale and bounded below by a thermal transition scale associated with hadronic matter formation. The event horizon functions as an information horizon: its surface area reflects the entropy of the microscopic degrees of freedom stored in the core. Accreting hadronic matter increases the internal QCD energy, heats the core and expands the horizon, whereas quantum fluctuations at the horizon permit a slow leakage of internal energy interpreted as Hawking radiation. At late stages, when accretion becomes negligible and the core temperature approaches the QCD critical value, a confinement-driven phase transition may reorganize internal energy and produce signatures on galactic scales.

Gravastars.

Gravastar models replace the black-hole interior by a de Sitter core surrounded by a thin shell of exotic matter. Their non-singular nature relies on a discontinuous phase structure and an equation of state that typically violates standard energy conditions. In contrast, the QEV model does not invoke exotic matter or a vacuum bubble: the interior is composed of experimentally established QCD matter and its thermodynamic degrees of freedom. The bounded curvature arises from the finite spectral support of the vacuum, not from a tailor-made interior geometry.

Quark stars and related compact objects.

Quark-star models describe ultra-dense stellar remnants composed of deconfined quark matter, yet they do not contain an event horizon and therefore do not represent black holes. The QEV interior shares a quark–gluon plasma component, but differs crucially in that gravitational collapse proceeds far enough to generate a horizon. The horizon entropy then becomes an essential part of the dynamics: it encodes the information of the QGP interior through holographic relations. This interplay between QCD matter and the horizon is absent in horizonless quark-star scenarios.

String-theoretic microstate/fuzzball models.

Fuzzball constructions remove the singularity by replacing the entire interior with a superposition of horizon-scale microstate geometries. These models rely on string-theoretic degrees of freedom at or near the Planck scale. The QEV framework takes the opposite approach: it addresses the black-hole interior using only sub-Planckian, experimentally accessible QCD physics. Instead of modifying the geometry at the horizon scale, QEV modifies the behavior of vacuum excitations by bounding their spectral support. In this sense the two approaches are complementary: QEV shows that many singularity-related issues can already be resolved without invoking Planck-scale microstructure.

Overall, the QEV model occupies a distinct conceptual position. It provides a non-singular black-hole interior derived from known QCD thermodynamics and a physically motivated bounded vacuum spectrum, without requiring exotic matter, horizon-scale microstate structure, or ad hoc interior geometries.

For an explicit toy model of a non-singular interior with a QCD–bounded energy density and finite curvature, see Appendix E

3.6. Physical Energy Mechanism of Black Hole Existence

The absence of a singularity, as shown in Sec. 3.3, requires that the interior stress–energy tensor remains bounded. In the QEV/QCD framework this is not an extra assumption but the consequence of a specific physical mechanism. In this subsection we summarise the key dynamical ingredients that allow a black hole interior to exist, to remain stable over long timescales, and to evolve under mass gain and mass loss.

3.6.1. Bounded Vacuum Energy as Enabling Condition

A black hole can only develop a physical interior if the vacuum fluctuations that accompany gravitational collapse are bounded in energy. In the QEV model the vacuum Hamiltonian is spectrally truncated at the QCD scale,

so that the corresponding energy density cannot exceed

consistent with lattice-QCD determinations of the high-temperature equation of state [

4,

8]. This spectral bound prevents runaway collapse and allows the interior geometry to settle into a regular, high-entropy state instead of forming a curvature singularity. In the QEV picture, the black-hole interior is therefore a thermodynamic phase supported by a finite, QCD-bounded vacuum energy density rather than a region of divergent curvature.

3.6.2. QCD Thermodynamics as Stabilising Mechanism

Above the QCD transition the system enters a regime in which the temperature approaches an effective limiting value, analogous to the Hagedorn behaviour of hadronic matter [

10,

13] and to the thermodynamic phenomenology of the quark–gluon plasma in heavy-ion collisions [

23,

24,

31]. In this regime additional energy does not significantly raise the temperature but instead increases the entropy of the quark–gluon plasma,

where

denotes the limiting QCD temperature. This behaviour provides a natural stabilising mechanism for the interior core: energy influx through accretion produces a larger, more entropic core at essentially the same temperature, rather than driving a thermal runaway. The stability of the interior is therefore fundamentally entropic rather than purely thermal.

3.6.3. Mass Gain and Mass Loss

During its lifetime a black hole undergoes both energy gain and energy loss. Accretion and mergers increase the mass and entropy of the interior. Because the core density is bounded by

, a simple scaling estimate gives

so that the core radius grows with the total mass while remaining in the QGP phase.

The relative size of these scales is summarized in

Figure 2. Mass loss through Hawking radiation [

15] induces the opposite evolution: the mass decreases and the core radius shrinks. As long as the interior density remains above the QCD transition threshold, the core stays in the QGP phase and its temperature remains close to

. In this regime the Hawking temperature of the horizon is much lower than the interior QCD temperature, so that the core acts as a high-entropy reservoir feeding a comparatively cold outgoing flux.

3.6.4. Cooling Below the QCD Scale and End-of-Life Behaviour

When sufficient mass has been lost, the interior density eventually falls below the QCD transition scale. At this point the QGP core can no longer be maintained and the system undergoes a reverse transition to hadronic matter. This transition is accompanied by a release of latent heat, which contributes to the final stages of Hawking evaporation.

Two qualitative end states are then possible. If the effective vacuum spectrum has a nonzero lower bound, the evaporation can halt at a finite mass, leaving a small, cold remnant. If no such bound is present, the black hole continues to evaporate until its mass vanishes. In both scenarios the evolution is governed by the QEV/QCD bounded-energy structure of the interior, while the horizon entropy continues to encode the macroscopic information about the black hole state [

5]. This provides a dynamical foundation for the existence and long-term behaviour of black holes in the QEV framework and complements the more traditional thermodynamic viewpoint based on horizon area and entropy.

Figure 2.

Logarithmic comparison of the characteristic physical scales relevant to the QCD-bounded vacuum and black-hole interior model. The plot shows:

(i) the QGP core radius ,

(ii) the Schwarzschild horizon radius for a typical stellar-mass black hole,

(iii) the quark–gluon plasma energy density , and

(iv) the limiting QCD/Hagedorn temperature .

The logarithmic scale highlights the enormous separation between geometric scales (kilometres) and QCD thermodynamic scales (densities and temperatures), while demonstrating that all quantities remain finite and physically governed by QCD rather than Planck-scale physics. This illustrates the central claim of the paper that black-hole interiors can be nonsingular due to QCD-imposed upper limits on energy density and temperature.

Figure 2.

Logarithmic comparison of the characteristic physical scales relevant to the QCD-bounded vacuum and black-hole interior model. The plot shows:

(i) the QGP core radius ,

(ii) the Schwarzschild horizon radius for a typical stellar-mass black hole,

(iii) the quark–gluon plasma energy density , and

(iv) the limiting QCD/Hagedorn temperature .

The logarithmic scale highlights the enormous separation between geometric scales (kilometres) and QCD thermodynamic scales (densities and temperatures), while demonstrating that all quantities remain finite and physically governed by QCD rather than Planck-scale physics. This illustrates the central claim of the paper that black-hole interiors can be nonsingular due to QCD-imposed upper limits on energy density and temperature.

4. Related Work

The idea that black hole singularities may be resolved by effective high-density matter sources or modified vacuum structures has been explored in several contexts. Early proposals include regular black hole models in which the central singularity is replaced by a finite, de Sitter-like core [

2,

12,

16]. These models typically introduce an effective energy-momentum tensor designed to satisfy appropriate energy conditions while ensuring a smooth transition between the interior core and the exterior Schwarzschild or Kerr geometry.

More recent approaches consider quantum gravity motivated scenarios, such as effective loop quantum gravity models that modify the interior geometry by quantum corrections to the classical curvature [

7,

20,

22]. Other works use non-perturbative features of quantum field theory, including vacuum polarization or non-linear electrodynamics, as possible mechanisms for obtaining non-singular interiors [

1,

9]. In addition, holographic and lower-dimensional gravity models have examined how entanglement structure and generalized entropy can influence the effective geometry behind horizons [

26,

27].

The present work differs from these approaches by focusing on a vacuum structure that is phenomenologically bounded by physical processes associated with the QCD confinement scale and by thermal freeze-out at low energies. While the resulting model does not derive from a full quantum field theoretic or quantum gravitational framework, it proposes a concrete physical mechanism that limits vacuum fluctuations and thereby provides an effective source capable of supporting non-singular black hole interiors. The goal is therefore not to introduce new fields or postulate specific quantum corrections, but to explore how known microphysical scales may influence the deep interior geometry of black holes in a minimal phenomenological setting.

5. Discussion, Limitations and Outlook

5.1. Discussion and Limitations

In this section we discuss the broader implications of the proposed QCD-bounded vacuum framework and outline its main limitations and directions for future research. The results presented in this work indicate that a vacuum with bounded spectral support may provide an effective mechanism for avoiding curvature singularities inside black holes while leaving the exterior geometry well approximated by classical general relativity. The emergence of a finite-density core supported by the bounded vacuum suggests that microscopic hadronic scales could play a role in regimes traditionally assumed to be governed solely by quantum gravity or trans-Planckian physics.

Several limitations of the present analysis should be noted. First, the bounded vacuum structure employed here is not derived from a microscopic calculation within quantum field theory in curved spacetime or from a fundamental theory of gravity. It represents a phenomenological assumption motivated by the presence of natural energy scales in QCD and early-universe thermodynamics. Second, the interior geometry discussed in this work is not obtained from an explicit solution of the Einstein equations with a fully specified energy–momentum tensor. A more complete treatment—incorporating self-consistency, stability analysis and collapse dynamics—remains to be developed. Third, backreaction effects and extensions to rotating (Kerr) black holes have not been addressed and may alter the detailed structure of the interior.

Despite these limitations, the framework suggests several promising avenues for further investigation. A more detailed effective field theory approach to a bounded vacuum could clarify the microscopic consistency of the model. It would also be valuable to explore connections with holographic and entanglement-based descriptions of black hole interiors, where similar themes of bounded spectra and finite entropy appear. Finally, studying dynamical collapse and rotating solutions may help determine whether a QCD-bounded vacuum can serve as a realistic and physically viable alternative to singular interior geometries in astrophysical black holes.

5.2. Outlook – Testable Consequences

Although the quark–gluon core model developed in this work is primarily conceptual, it leads to several qualitative and semi-quantitative predictions that provide potential observational tests.

Horizon-scale signatures and black-hole shadows

Because the event horizon is interpreted as an information horizon whose thermodynamic properties are tied to the finite QGP core and the spectrally bounded vacuum, small deviations from the classical Kerr near-horizon geometry may arise. These could manifest as modifications in the brightness profile, photon-ring substructure or polarization pattern of black-hole shadows observed by the Event Horizon Telescope and future very-long-baseline interferometry campaigns.

QGP-driven emission at low accretion rates

Even in low-accretion regimes, the finite thermal energy stored in the QGP core may drive residual nonthermal emission through quantum-fluctuation leakage at the information horizon. This could lead to detectable faint spectral components or characteristic variability in quiescent supermassive black holes, distinguishing the model from purely accretion-driven scenarios.

Late-time phase transition and galactic-scale imprints

As accretion declines and the core temperature approaches the QCD critical value, the model predicts a confinement-driven internal phase transition. Such a process may alter the coupling between the black hole and its galactic environment, potentially affecting long-term feedback, gas heating and the distribution of energy in the circumgalactic medium. In cosmological simulations, these effects could serve as indirect evidence for the existence of a finite QGP core rather than a classical singularity.

These testable predictions show that the quark–gluon core model is not merely a conceptual replacement for singularities but a physically motivated framework that can be linked to observational programmes. Future work will develop quantitative predictions for comparison with data.

6. Conclusions

In this paper we have developed a quark–gluon core model for black holes, grounded in the framework of a spectrally bounded Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV). Instead of treating the interior as a classical singularity, we describe it as a finite, thermodynamically stable quark–gluon plasma (QGP) core whose properties are constrained by QCD at high densities and by a thermal transition scale at low temperatures. Within this picture, the event horizon becomes an information horizon whose entropy counts the microscopic degrees of freedom associated with the core, and Hawking radiation is reinterpreted as a thermodynamic leakage of internal energy through quantum fluctuations at this boundary.

Matter accretion plays a central role in sustaining the QGP core. Infalling hadronic matter injects both mass and internal QCD energy, raising the core temperature and expanding the information horizon in accordance with the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy relation. When accretion is strong, the hot core, rotation and magnetohydrodynamic coupling naturally support powerful jet formation and efficient energy extraction. At late times, when accretion declines and the core cools towards the QCD critical temperature, the model predicts a confinement-driven phase transition that reorganizes the internal energy and may leave imprints on galactic scales.

By embedding black holes in a bounded vacuum, the present framework ties together three traditionally separate domains: black-hole thermodynamics, QCD microphysics and galactic evolution. The removal of the singularity is not achieved through ad hoc assumptions, but follows from the same spectral bounds that render the vacuum energy density finite in the QEV model. This suggests that the resolution of singularities, the characterization of vacuum energy and the long-term role of black holes in cosmic structure formation may be facets of a single underlying physical mechanism.

Although our treatment has been mainly conceptual, we have outlined several testable consequences of the quark–gluon core model, including possible signatures in black-hole shadows, low-accretion emission, jet properties and the coupling between supermassive black holes and their host galaxies. These predictions point toward concrete observational and numerical avenues to probe whether black holes contain physical QGP cores embedded in a bounded vacuum, or whether the classical singularity picture must be retained. Future work will focus on developing quantitative models of the core structure and its observational signatures, and on exploring the implications of the QEV framework for other strong-gravity systems and for cosmology more broadly.

Appendix A. Derivation of the Bounded Vacuum Spectrum

In conventional quantum field theory (QFT), the vacuum energy density is given by

where

is the density of states. For relativistic fields in flat spacetime,

which leads to the well-known quartic divergence,

The QEV framework replaces this unbounded integral with a spectrally limited vacuum structure. In this appendix we derive the resulting bounded spectrum and its physical justification.

Clarification onthe notation Emin.

In previous work on the cosmological sector of the QEV framework [

17,

18], the lower spectral bound

denoted the infrared suppression scale associated with cosmological thermal freeze-out and the observed vacuum density. In the present paper, however, we restrict attention to the high-energy, QCD-dominated regime relevant for gravitational collapse. Accordingly, the symbol

refers here to the QCD-scale thermal freeze-out threshold for hadronic degrees of freedom, not to the much lower cosmological infrared bound used in [

17]. To avoid confusion, one may interpret the present usage as

, i.e. the lower edge of the QCD-domain spectral band.

Appendix A.1. Upper Bound: Confinement and QCD Deconfinement Scale

Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) confines colored particles to regions larger than the confinement length,

This implies that vacuum modes with shorter wavelengths cannot exist as physical excitations. Using the de Broglie relation,

the confinement length translates into an energy bound,

Moreover, lattice QCD and heavy-ion collisions show that the quark–gluon plasma saturates around the Hagedorn temperature[

23,

31],

above which additional energy increases the number of degrees of freedom rather than the temperature. Thus the vacuum cannot support independent excitations beyond the QCD scale.

We therefore impose the physical upper bound:

Appendix A.2. Lower Bound: Thermal Freeze–out of Hadronic Modes

At sufficiently low temperatures, hadronic degrees of freedom drop out of thermal equilibrium. The freeze-out scale in the expanding universe and in QCD systems lies around

falling to the point where hadrons become massive, non-relativistic, and no longer contribute effectively to vacuum fluctuations.

We represent this suppression by a thermal lower bound,

Below this scale, the density of accessible vacuum modes effectively vanishes.

Appendix A.3. Finite Spectral Interval

Combining the physical upper and lower bounds yields the restricted vacuum spectrum:

The vacuum energy density becomes

For a relativistic density of states

, this evaluates to

which is manifestly finite.

This contrasts sharply with unbounded QFT, where

Thus the presence of QCD confinement and thermal freeze-out replaces an infinite vacuum integral with a finite spectral band.

Appendix A.4. Physical Interpretation

The bounded spectrum has several immediate consequences:

The vacuum cannot excite modes of arbitrarily short wavelength because QCD forbids unconfined colored states.

The vacuum cannot excite arbitrarily low-energy hadronic modes because they thermally freeze out.

The vacuum energy density is therefore not ultraviolet-divergent but finite.

Additional energy injected into the vacuum near the QCD scale increases the number of internal degrees of freedom, not the frequency of vacuum modes.

In gravitational collapse, this spectral boundedness enforces a maximum internal temperature and prevents singularity formation.

The QEV model interprets the vacuum not as an unstructured background but as a spectrally bounded physical medium whose microscopic limits are set by QCD dynamics. This appendix provides the mathematical basis for these bounds, which underpin the finite vacuum energy density and the non-singular behavior of black holes developed in

Section 2–4.

Appendix B. Thermodynamics of the Quark–Gluon Plasma

The quark–gluon plasma (QGP) constitutes the deconfined phase of QCD matter at high temperature or baryon density. Its thermodynamic properties play a central role in the QEV framework and in the structure of black–hole interiors. In this appendix we summarize the key relations governing the QGP and show how they support the bounded vacuum spectrum introduced in

Section 2.

Appendix B.1. Equation of State

In the deconfined phase, quarks and gluons behave approximately as relativistic degrees of freedom. For an ideal QGP, the pressure and energy density follow the Stefan–Boltzmann relations,

where

is the effective number of relativistic degrees of freedom.

For three light quark flavours,

The energy density at

is therefore

consistent with lattice QCD results.

Appendix B.2. Hagedorn Behavior and Limiting Temperature

The hadronic phase below the QCD transition exhibits an exponential growth of the density of states,

leading to the existence of a limiting temperature

, above which the hadronic phase becomes thermodynamically unstable.

As energy is injected into the system,

meaning that additional energy creates new particle species rather than raising the temperature. This behavior signals the transition to deconfined quark–gluon matter.

Appendix B.3. Strongly Interacting Regime

Heavy–ion experiments reveal that the QGP is not an ideal weakly interacting plasma, but rather a nearly perfect fluid with a small shear viscosity to entropy density ratio,

close to the theoretical lower bound proposed in holographic gauge/gravity duality. This indicates a strongly coupled state dominated by collective behavior.

The entropy density is given by

which rises sharply near the QCD transition and subsequently grows more slowly, stabilizing as the system approaches the Hagedorn limit.

Appendix B.4. QGP Thermodynamics and the QEV Model

The QGP thermodynamics supports the QEV hypothesis in several ways:

- 1.

**Limiting temperature:** For strongly interacting QCD matter there exists an effective limiting temperature,

in the sense that additional energy near this scale predominantly increases entropy and particle multiplicity rather than raising the temperature.

- 2.

**Entropy-dominated evolution:** Additional energy contributes to entropy production rather than raising the temperature,

- 3.

**Finite maximum energy density:** The QCD equation of state enforces a maximal energy density,

preventing divergent behavior.

- 4.

**Absence of singularities:** Since neither energy density nor temperature diverges, spacetime curvature remains finite inside gravitationally collapsed objects composed of QCD matter.

- 5.

**Horizon growth governed by QCD:** Entropy production in the core leads to growth of the horizon area,

consistent with the Bekenstein–Hawking relation.

Appendix B.5. Implications for Black–Hole Interiors

Once the interior of a black hole collapses into a QGP core, the following thermodynamic picture emerges:

Thus black holes act as entropy amplifiers rather than singular heat sinks. The QCD–bounded structure of the QGP provides a natural ultraviolet regulator for gravitational collapse.

In the QEV framework, this finite-temperature, finite-density QCD phase replaces the classical singularity with a stable, high-entropy core whose properties are determined by well-defined physics rather than divergent curvature.

In summary, the thermodynamics of the quark–gluon plasma supplies the microscopic foundation for the bounded-vacuum structure central to the QEV model and provides the necessary physical mechanism for non-singular black–hole interiors.

Appendix C. Information Horizon, Holography, and the Status of the Planck Scale

The Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) model implies that the interior of a black hole, once compressed to QCD densities, forms a finite–temperature quark–gluon medium. In such a system, physical quantities such as temperature, entropy density, and curvature remain finite, while the growth of the black–hole horizon is governed by the thermodynamic properties of this strongly interacting phase. These features align naturally with the holographic principle, which states that the information content of a gravitational system is encoded on its boundary rather than in its volume.

Appendix C.1. The Information Horizon

In a strongly interacting QCD core, additional accreted energy increases the entropy according to

where

is the Hagedorn temperature characterizing the limiting thermodynamic behavior of QCD matter.

Via the Bekenstein–Hawking relation,

an entropy increase leads directly to an expansion of the information horizon,

Thus, the black–hole horizon evolves not as a geometrical singularity but as a thermodynamic information boundary. The QCD core stores information internally, while the horizon serves as the geometric encoding surface for this information.

Appendix C.2. Holographic Interpretation

The holographic principle asserts that the maximum information content of a region of spacetime is proportional to the area—not the volume—of its boundary. In the QEV model, this is realized dynamically:

- 1.

The QCD–bounded vacuum enforces a maximal energy density and a maximal temperature.

- 2.

Additional internal energy produces additional microscopic degrees of freedom in the QGP core.

- 3.

This increase in S demands an increase in horizon area A, consistent with holographic scaling.

The holographic behavior therefore arises not from Planck-scale quantum gravity, but from the microscopic physics of QCD combined with the thermodynamics of the vacuum.

Appendix C.3. The Planck Scale as a Theoretical Benchmark

The traditional assumption in quantum gravity is that the Planck length

represents a fundamental physical minimum length. This scale is obtained by combining constants of distinct physical origin, where

ℏ is the quantum of action,

G the gravitational coupling, and

c the relativistic limiting speed. The Planck length therefore arises very naturally from dimensional analysis. At the same time, the Planck length has not yet been probed experimentally, and no direct observation requires new physics precisely at this scale.

By contrast, the QCD scale is empirically established in hadron spectroscopy, lattice QCD, and heavy-ion collisions, and thus provides an observed reference scale for strong-interaction physics. In this work we do not question the potential relevance of the Planck scale for quantum gravity; rather, we emphasize that many aspects of black-hole interiors can already be addressed using experimentally accessible QCD physics at energies far below the Planck regime.

Appendix C.4. QCD Scale and Planck Scale

In the QEV framework the dominant ultraviolet regulator for physically realized gravitational systems is provided by the QCD confinement scale, rather than by a hypothetical hard cutoff at the Planck scale. Concretely:

- 1.

The effective upper bound on vacuum excitations in the present model is the confinement energy,

not the Planck energy

.

- 2.

The maximum temperature reached by strongly interacting matter is set by the QCD (Hagedorn–like) temperature,

far below the Planck temperature.

- 3.

The corresponding maximum energy densities are of order

again many orders of magnitude below the Planck density.

These statements do not exclude the possibility that genuinely new physics appears at or above the Planck scale. Instead, they indicate that in the QEV framework the dominant effective ultraviolet regulator for astrophysical gravitational collapse is provided by the QCD confinement scale, while Planck-scale microstructure—if present—would enter only beyond the densities considered here. In this sense the present model should be viewed as complementary to Planck-scale approaches: it shows that much of the singularity problem can already be mitigated within the domain of sub-Planckian, QCD-dominated matter.

Appendix C.5. Consequences for Non–Singular Black Holes

Because the interior dynamics is controlled by a bounded, QCD–dominated vacuum spectrum, black–hole singularities in the QEV picture can be avoided without explicitly invoking Planck–scale quantum gravity. Gravitational collapse saturates in a finite– temperature, finite–entropy quark–gluon core, and the horizon evolves as an information–carrying surface whose area tracks the thermodynamic state of this core.

In this sense the QEV model complements, rather than replaces, possible Planck–scale completions of gravity: it shows that a large part of the singularity and information–loss problems can already be addressed within the domain of experimentally anchored QCD physics.

Appendix D. Comparison of the QEV Framework with QFT Cutoffs, Holographic Models, and Loop Quantum Cosmology

The Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) framework differs fundamentally from traditional approaches that attempt to regulate vacuum divergences or resolve the singularities of gravitational collapse. In this appendix we compare the QEV model with three widely studied frameworks: (1) conventional QFT ultraviolet cutoffs, (2) holographic dualities (specifically AdS/CFT), and (3) loop quantum cosmology (LQC). We highlight the conceptual, mathematical, and physical differences, and emphasize which elements are experimentally supported.

Appendix D.1. QEV Versus Conventional QFT Ultraviolet Cutoffs

In standard quantum field theory, vacuum energy is evaluated as

which diverges quartically.

A common theoretical fix is to impose a high-energy cutoff,

which renders the integral finite. However, this procedure introduces several problems:

- 1.

The cutoff is arbitrary. There is no physical principle that selects a particular .

- 2.

No experimental signature exists at the cutoff scale.

- 3.

Cutoffs break Lorentz invariance unless implemented with great care.

- 4.

The cosmological constant is still far too large unless fine-tuning of 120 orders of magnitude is applied.

By contrast, in the QEV framework:

is not an arbitrary parameter but an

experimentally verified physical scale. Similarly, the thermal freeze-out scale provides a natural lower bound.

Thus, QEV replaces an ad hoc mathematical cutoff by a **physically realized, experimentally measured spectral boundary** rooted in QCD.

Appendix D.2. QEV Versus Holographic Duality (AdS/CFT)

The AdS/CFT correspondence states that gravitational dynamics in a (d+1)-dimensional asymptotically anti-de Sitter spacetime can be described by a conformal field theory on the boundary. This provides a conceptual understanding of black-hole entropy and horizon microstates.

However:

AdS/CFT applies strictly to anti-de Sitter spacetime, not to flat or de Sitter spacetime.

It does not provide a physical mechanism for singularity resolution inside realistic black holes.

It does not offer a finite vacuum spectrum or a physical vacuum cutoff.

It operates at the Planck scale, which has no direct experimental underpinning.

In the QEV model:

- 1.

Holographic scaling arises dynamically from

without assuming AdS/CFT duality.

- 2.

The microscopic degrees of freedom are QCD excitations, not hypothetical Planck-scale constituents.

- 3.

Holography is a thermodynamic consequence of a QCD-bounded interior, not a quantum-gravitational duality postulate.

- 4.

The model applies directly to astrophysical black holes in our universe.

Thus, QEV reproduces holographic behavior without requiring AdS geometry or Planck-scale microphysics.

Appendix D.3. QEV Versus Loop Quantum Cosmology (LQC)

Loop Quantum Cosmology replaces classical singularities with quantum bounces. Central features of LQC include:

a quantized geometry with discrete volume operators;

curvature scalars bounded by the Planck density;

a big bounce instead of a big bang singularity.

However, key limitations include:

The Planck scale is assumed to be physically fundamental, yet unmeasured.

Black-hole interiors are highly model-dependent and still debated.

The degrees of freedom are quantized geometry, not experimentally observed matter fields.

In contrast, the QEV model:

- 1.

uses experimentally verified QCD physics rather than Planck-scale geometry;

- 2.

derives singularity avoidance from the QGP equation of state:

- 3.

replaces the singularity with a thermodynamic core of finite entropy;

- 4.

avoids introducing discrete spacetime or untested quantum gravity assumptions.

Thus, QEV is grounded in standard, well-tested physics rather than speculative Planck-scale quantization.

Summary of Key Distinctions

Table A1.

Qualitative comparison of the QEV framework with conventional QFT cutoffs, holographic duality (AdS/CFT), and loop quantum cosmology (LQC).

Table A1.

Qualitative comparison of the QEV framework with conventional QFT cutoffs, holographic duality (AdS/CFT), and loop quantum cosmology (LQC).

| Feature |

QEV |

QFT cutoff |

AdS/CFT |

LQC |

| Vacuum bound |

QCD scale |

Arbitrary |

None |

Planck scale |

| Singularity removal |

Yes (QCD EOS) |

No |

No |

Yes (bounce) |

| Holography |

Thermodynamic |

No |

Built-in duality |

Partial |

| Experiment support |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Planck scale needed |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Max. temperature |

Hagedorn |

None |

Planck |

Planck |

QEV stands apart as the only framework in which:

the vacuum spectrum is bounded by experimentally established physics;

singularities are avoided without invoking Planck-scale quantization;

holography arises dynamically from thermodynamics rather than dualities.

This makes the QEV framework both physically economical and conceptually coherent, offering an experimentally anchored alternative to speculative ultraviolet completions of gravity.

Appendix E. Bounded Vacuum, Spectral Projection and a Constant-Density Core

In this appendix we collect the technical ingredients underlying the Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) framework and its application to a simple constant–density QCD core.

Section E.1 formulates the bounded vacuum as a spectral projection of the Hamiltonian,

Section E.2 summarizes the basic thermodynamic consequences,

Section E.3 discusses semiclassical gravity and bounded curvature,

Section E.4 provides order-of-magnitude estimates for QCD-scale cores, and

Section E.5 gives the explicit constant-density interior solution used in Sec. 3.3 of the main text.

Appendix E.1. Bounded Vacuum as a Spectral Projection

Let

H denote the self-adjoint Hamiltonian of the underlying quantum field–theoretic description of matter plus vacuum. By the spectral theorem we can write

where

is the spectrum of

H and

is the associated projection-valued spectral measure.

In the QEV framework we distinguish between the full spectrum

and the physically accessible spectral band that characterizes vacuum fluctuations in the presence of QCD matter. This band is defined by two energy scales,

where

is of order the QCD confinement scale and

represents the thermal freeze-out threshold of hadronic degrees of freedom in the relevant high-energy environment (see also Appendix A). We introduce the spectral projector onto this band,

and define the physical vacuum Hamiltonian as

By construction, the spectrum of

is contained in the compact interval

. This encodes the QEV postulate that vacuum excitations outside this band are either dynamically frozen out (below

) or do not propagate as physical asymptotic states (above

).

In this work

should be understood as an

effective Hamiltonian describing the physically relevant sector of the vacuum. The projector

selects the QCD-dominated energy band in which vacuum fluctuations are dynamically active in the presence of strongly interacting matter. This projection is not intended as a fully fundamental, micro-local operator construction; instead, it captures in a coarse-grained sense that excitations outside this band either do not propagate as physical asymptotic states or are dynamically frozen out. Within this effective framework the partition function

remains finite and is naturally bounded by QCD thermodynamics.

The spectral band should be understood as defined in the local rest frame of the QGP core, where thermodynamic equilibrium is well defined; the construction is therefore effective rather than fundamental. We do not claim H_phys to represent a fundamental micro-local QFT; rather, it is an effective coarse-grained operator capturing the dynamically active part of the vacuum.

Appendix E.2. Thermodynamics with a Bounded Spectrum

The bounded spectrum of

has immediate consequences for the thermodynamic properties of the vacuum and of QCD matter embedded in it. Consider the canonical partition function associated with the physical band,

where the sum runs over eigenvalues

of

, counted with multiplicity. Because the spectrum is bounded and the degeneracies are physically limited by QCD microphysics,

is finite for all

.

The corresponding free energy, internal energy and entropy are

Since

for all

n, we obtain a uniform bound on the internal energy,

and therefore also on the energy density

in any finite volume. In the context of a quark–gluon plasma, this upper bound can be identified with the maximal energy density

attainable before confinement and hadronization set in. The QEV framework thus parametrizes the vacuum as a thermodynamic medium with finite energy density and entropy content, controlled by QCD thermodynamics rather than by an ad hoc ultraviolet cutoff.

Appendix E.3. Semiclassical Gravity and Bounded Curvature

In a semiclassical setting, matter and vacuum fluctuations couple to the spacetime geometry through the expectation value of the renormalized stress–energy tensor,

Within the QEV framework, the relevant state is restricted to the spectral band of

. Schematically, we can write

where the expectation value is taken in a suitable (possibly mixed) state supported on the image of

. The operator inequality

implies that all local energy densities and pressures derived from

are bounded by a constant

set by the QCD scale and the microscopic equation of state. Consequently, there exists a constant

such that all curvature invariants, including the Kretschmann scalar

satisfy

throughout the region where the QEV description applies.

In the context of black-hole interiors this means that gravitational collapse leads to a finite-temperature, finite-density quark–gluon core with bounded curvature, rather than to a singularity. The operator-theoretic picture therefore provides a compact way of expressing the physical content of the QEV model: the vacuum behaves as a medium whose fluctuations are spectrally bounded by QCD, and the corresponding stress–energy tensor remains within a finite range, ensuring non-singular geometric behavior at sub-Planckian scales.

Appendix E.4. Order-of-Magnitude Estimates for a QCD-Bounded Core

To make the preceding discussion more concrete, it is useful to attach rough numerical values to the QCD-bounded energy density. From Appendix B we recall that lattice QCD and heavy-ion data imply a quark–gluon plasma energy density of order

Using

and

, this corresponds to

The associated mass density is

comparable to or somewhat above typical neutron-star central densities, but still enormously below the Planck density

.

Identifying the constant-density core parameter

with the QCD-scale density

makes it clear that the curvature is controlled by QCD physics rather than by Planck-scale quantities. A simple scaling argument illustrates this: in the semiclassical regime one has

, so that the typical magnitude of the Riemann tensor behaves as

and the Kretschmann scalar scales as

For

this is manifestly finite. In this way the maximal curvature in the interior is directly tied to the QCD-limited energy density, in agreement with the qualitative discussion in Sec. 3.3.

These estimates illustrate that the non-singular interior envisaged in the QEV framework can be realized at densities that are high but still firmly within the regime of known strong-interaction physics. The avoidance of curvature divergences therefore does not rely on Planck-scale microstructure, but follows from imposing a QCD-motivated bound on the interior energy density.

Appendix E.5. Constant-Density QCD Core: Technical Derivation

We now collect the minimal technical steps needed to verify that the constant–density QCD core used in Sec. 3.3 of the main text is a regular solution of the Einstein equations, with finite pressure and finite curvature everywhere.

We start from the static, spherically symmetric line element

and a perfect fluid with energy density

and pressure

. The

–component of Einstein’s equations gives

while hydrostatic equilibrium in the static configuration yields the Tolman– Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) equation

In the constant–density core we take

with

identified with the QCD–scale energy density,

. Integrating the mass equation gives

so that the interior metric coefficient satisfies

Substituting this mass function in the TOV equation yields the standard Schwarzschild interior pressure profile, which remains finite everywhere as long as the compactness obeys the Buchdahl bound,

The QCD bound on

implies that this condition is naturally satisfied for core radii larger than the QCD length scale, so that the pressure remains regular and no internal divergence appears.

The Kretschmann scalar for a static, spherically symmetric metric of the above form can be written schematically as

where

denotes the purely algebraic contributions from the stress–energy tensor. For the constant–density core with

so that

where

is a finite numerical constant of order unity. The precise value of

is immaterial for our purposes; what matters is the scaling

The matter part of the Kretschmann scalar, constructed from the stress–energy tensor of a constant-density fluid, has the same schematic dependence,

so that the total Kretschmann scalar can be written as

with

a finite, dimensionful constant determined by the QCD-dominated equation of state and the details of the interior solution. In particular, at the center of the core one obtains

which is manifestly finite as long as

is finite. Identifying

with the QCD-scale density

then shows that the maximal curvature in the interior is directly tied to QCD physics, in agreement with the qualitative discussion in

Sec. 3.3.

In summary, this appendix records the spectral, thermodynamic and geometric ingredients of the QEV model and shows that a constant–density QCD core is an explicit regular solution of the Einstein equations, with bounded energy density, pressure and curvature. It thus serves as the technical backbone of the main QEV argument about bounded vacuum energy and non-singular black-hole interiors.

Appendix F. Constant-Density QCD Core as a Nonsingular Interior

In the main text we argued that, within the Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) framework, the interior of a black hole is described by a finite quark–gluon plasma (QGP) core whose energy density is bounded above by the QCD confinement scale. To illustrate this mechanism explicitly, we construct here a simple but physically realistic example based on a constant–density Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) solution. Although idealised, this model captures the essential feature of a nonsingular interior governed by a QCD–limited energy density.

Appendix F.1. QCD-Scale Energy Density

Hydrodynamic and lattice–QCD studies constrain the energy density of deconfined quark–gluon plasma to the range

For definiteness we adopt the representative value

This density is many orders of magnitude below the Planck density and lies well within the regime where QCD is experimentally and phenomenologically constrained. In the QEV framework we identify

as a typical QCD–limited interior density for strongly interacting matter in the core of a collapsed object.

Appendix F.2. Constant–Density TOV Model

We model the black–hole interior by a static, spherically symmetric perfect fluid with constant energy density

. In geometrised units (

) the interior metric can be written as

where

is the Misner–Sharp mass function. For a constant density one has

The pressure profile

is determined by the TOV equation

We consider a core radius

representative of the inner region of a stellar–mass black hole. In cgs units this corresponds to

.

The enclosed mass of the constant–density core is then

Substituting the numerical values (

A36) and (

A40) gives

Thus the core mass is of order

, well below the total mass of a typical stellar black hole. The remaining mass is contained in the exterior region outside the constant–density core. This already shows that a QCD–limited interior can be embedded consistently inside an astrophysical black hole without dominating its total mass.

Appendix F.3. Finite Curvature: Absence of a Singularity

For a constant–density interior solution the Kretschmann scalar

is spatially constant to leading order and can be written schematically as

again in geometrised units. Using the QCD value (

A36) and converting back to cgs units one finds a central curvature of order

many orders of magnitude below the Planck curvature

. Thus, even at the centre

the curvature remains finite and extremely mild: the classical singularity is replaced by a smooth, QCD–regulated core with bounded curvature.

Appendix F.4. Matching to the Exterior Black–Hole Geometry

At

the interior solution is matched to an exterior Schwarzschild metric with total mass

. Matching requires continuity of the induced metric and of the Misner–Sharp mass. The exterior line element is

The event–horizon radius is

For a typical stellar–mass black hole with

, one has

, and therefore

The QCD core is thus deeply hidden behind the horizon and cannot produce direct electromagnetic emission, fully consistent with current observations of black–hole candidates.

Appendix F.5. Interpretation

This explicit example demonstrates that:

A finite QCD energy density naturally removes the black–hole singularity: the interior is described by a smooth constant–density QGP core instead of a curvature divergence.

The resulting curvature is small and physically acceptable, without the need for exotic matter or Planck–scale physics.

The core mass is only a small fraction of the total black–hole mass, so that the exterior geometry at observable radii is well approximated by the usual Schwarzschild (or Kerr) solution.

Such a core fits naturally into the QEV framework, in which vacuum fluctuations are bounded by QCD at short distances and the ultraviolet behaviour of gravitational collapse is regulated by known strong–interaction physics.

Therefore this appendix provides a concrete, nonsingular interior solution that supports the main claim of the paper: in a QCD–bounded vacuum, gravitational collapse can end in a finite–density quark–gluon core rather than in a curvature singularity.

References

- S. Ansoldi, “Spherical black holes with regular center,” in Conference Proceedings CP1122, pp. 3–15 (2009), arXiv:0802.0330 [gr-qc]. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Bardeen, “Non-singular general-relativistic gravitational collapse,” in Proceedings of the International Conference GR5, Tbilisi, USSR (1968), abstracts.

- J. M. Bardeen, B. C. Carter and S. W. Hawking, “The four laws of black hole mechanics,” Communications in Mathematical Physics 31, 161–170 (1973). [CrossRef]

- A. Bazavov et al., “Equation of state in (2+1)-flavor QCD,” Physical Review D 90, 094503 (2014). [CrossRef]

- J. D. Bekenstein, “Black holes and entropy,” Physical Review D 7, 2333–2346 (1973). [CrossRef]

- R. D. Blandford and R. L. Znajek, “Electromagnetic extraction of energy from Kerr black holes,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 179, 433–456 (1977). [CrossRef]

- C. G. Böhmer and K. Vandersloot, “Loop quantum dynamics of the Schwarzschild interior,” Physical Review D 76, 104030 (2007). [CrossRef]

- S. Borsányi et al., “Full result for the QCD equation of state with 2+1 flavors,” Physics Letters B 730, 99–104 (2014). [CrossRef]

- K. A. Bronnikov, “Regular black holes sourced by nonlinear electrodynamics,” International Journal of Modern Physics D 27(06), 1841005 (2018).

- N. Cabibbo and G. Parisi, “Exponential hadronic spectrum and quark liberation,” Physics Letters B 59, 67–69 (1975). [CrossRef]

- J. C. Collins and M. J. Perry, “Superdense matter: neutrons or asymptotically free quarks?,” Physical Review Letters 34, 1353–1356 (1975). [CrossRef]

- I. Dymnikova, “Vacuum nonsingular black hole,” General Relativity and Gravitation 24, 235–242 (1992).

- R. Hagedorn, “Statistical thermodynamics of strong interactions at high energies,” Nuovo Cimento Supplemento 3, 147–186 (1965).

- S. W. Hawking, “Black hole explosions?,” Nature 248, 30–31 (1974). [CrossRef]

- S. W. Hawking, “Particle creation by black holes,” Communications in Mathematical Physics 43, 199–220 (1975). [CrossRef]

- S. A. Hayward, “Formation and evaporation of non-singular black holes,” Physical Review Letters 96, 031103 (2006). [CrossRef]

- A. J. H. Kamminga, “Vacuum density and cosmic expansion: a physical model for vacuum energy, galactic dynamics and entropy,” Preprint, (2025). This work introduces the Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) model, in which the vacuum spectrum is bounded above by the QCD confinement scale and below by a thermal transition scale. [CrossRef]

- A. J. H. Kamminga, “The Quantum Emergent Vacuum: A Spectrally Bounded Framework for Physical Unification,” Preprint, (2025). This work provides a detailed development of the QEV framework and emphasizes that vacuum fluctuations occur only within a finite energy interval. [CrossRef]

- P. W. Milonni, The Quantum Vacuum: An Introduction to Quantum Electrodynamics, Academic Press (1994).

- L. Modesto, “Disappearance of the black hole singularity in quantum gravity,” Physical Review D 70, 124009 (2004). [CrossRef]

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne and J. A. Wheeler, Gravitation, W. H. Freeman (1973).

- J. Olmedo, S. Saini and P. Singh, “From black holes to white holes: a quantum gravitational, symmetric bounce,” Classical and Quantum Gravity 34(22), 225011 (2017). [CrossRef]

- E. V. Shuryak, “Quantum chromodynamics and the theory of superdense matter,” Physics Reports 61, 71–158 (1980). [CrossRef]

- E. V. Shuryak, “What RHIC experiments and theory tell us about properties of quark–gluon plasma?,” Nuclear Physics A 750, 64–83 (2005). [CrossRef]

- K. S. Thorne, R. H. Price and D. A. Macdonald (eds.), Black Holes: The Membrane Paradigm, Yale University Press (1986).

- E. Verheijden and E. Verlinde, “From the BTZ black hole to JT gravity: Geometrizing the island,” Journal of High Energy Physics 11, 092 (2021). [CrossRef]

- E. Verheijden and E. Verlinde, “No Page curves for the de Sitter horizon,” Journal of High Energy Physics 03, 040 (2022). [CrossRef]

- E. P. Verlinde, “On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton,” Journal of High Energy Physics 04, 029 (2011). [CrossRef]

- R. M. Wald, Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and Black Hole Thermodynamics, The University of Chicago Press (1994).

- S. Weinberg, “The cosmological constant problem,” Reviews of Modern Physics 61, 1–23 (1989). [CrossRef]

- K. Yagi, T. Hatsuda and Y. Miake, Quark-Gluon Plasma: From Big Bang to Little Bang, Cambridge University Press (2005).

| 1 |

The notation refers in this paper to the QCD-scale thermal freeze-out threshold for hadronic degrees of freedom. This should not be confused with the much lower cosmological infrared bound denoted by the same symbol in [ 17, 18], where the focus was on the low-energy sector of the QEV framework. In the present high-energy context one may read this as . |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).