Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Escherichia coli resistant to third-generation cephalosporins are a growing One Health concern, but data on extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) from wildlife in North Africa remain scarce. We aimed to characterize ESBL/AmpC-producing ExPEC from captive wild mammals in Tunisia and to situate these isolates in a global genomic context. Methods: In 2018, 30 fecal samples from 14 captive wild mammals in a private farm were screened on cefotaxime agar. Four resistant E. coli were recovered from a llama, lion, hyena and tiger. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and Illumina whole-genome sequencing were combined with in silico typing, resistome and virulome profiling, plasmid and mobile element analysis, human pathogenicity prediction and core-genome MLST-based minimum-spanning trees. Results: All isolates were MDR but remained susceptible to carbapenems, colistin and tigecycline. Two ST162/B1 isolates from the llama and tiger carried blaCMY-2, whereas two ST69/D isolates from the lion and hyena harbored blaCTX-M-15 and qnrS1. Genomes encoded 61–68 antimicrobial resistance genes and 114–131 virulence-associated genes, together with IncF-, IncI1- and IncY-type plasmids and IS26-rich insertion sequence profiles. PathogenFinder predicted a ≥0.93 probability of human pathogenicity for all isolates. cgMLST-based trees showed that Tunisian ST69 and ST162 clustered within internationally disseminated lineages containing human, animal and food isolates, rather than forming wildlife-restricted branches. Conclusions: Captive wild mammals in Tunisia can harbor high-risk ExPEC lineages combining ESBL/AmpC production, multidrug resistance and extensive virulence and mobility gene repertoires. These findings highlight captive wildlife as potential reservoirs and sentinels of clinically relevant E. coli and underscore the need for integrated WGS-based One Health surveillance at the human–animal–environment interface in North Africa.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Genomic Characteristics

2.2. Phylogenetic Background and In Silico Typing

2.3. Resistome and Chromosomal Mutations

2.4. Virulence Gene Content, Plasmid Replicons and Mobile Genetic Elements

2.5. In Silico Prediction of Human Pathogenic Potential

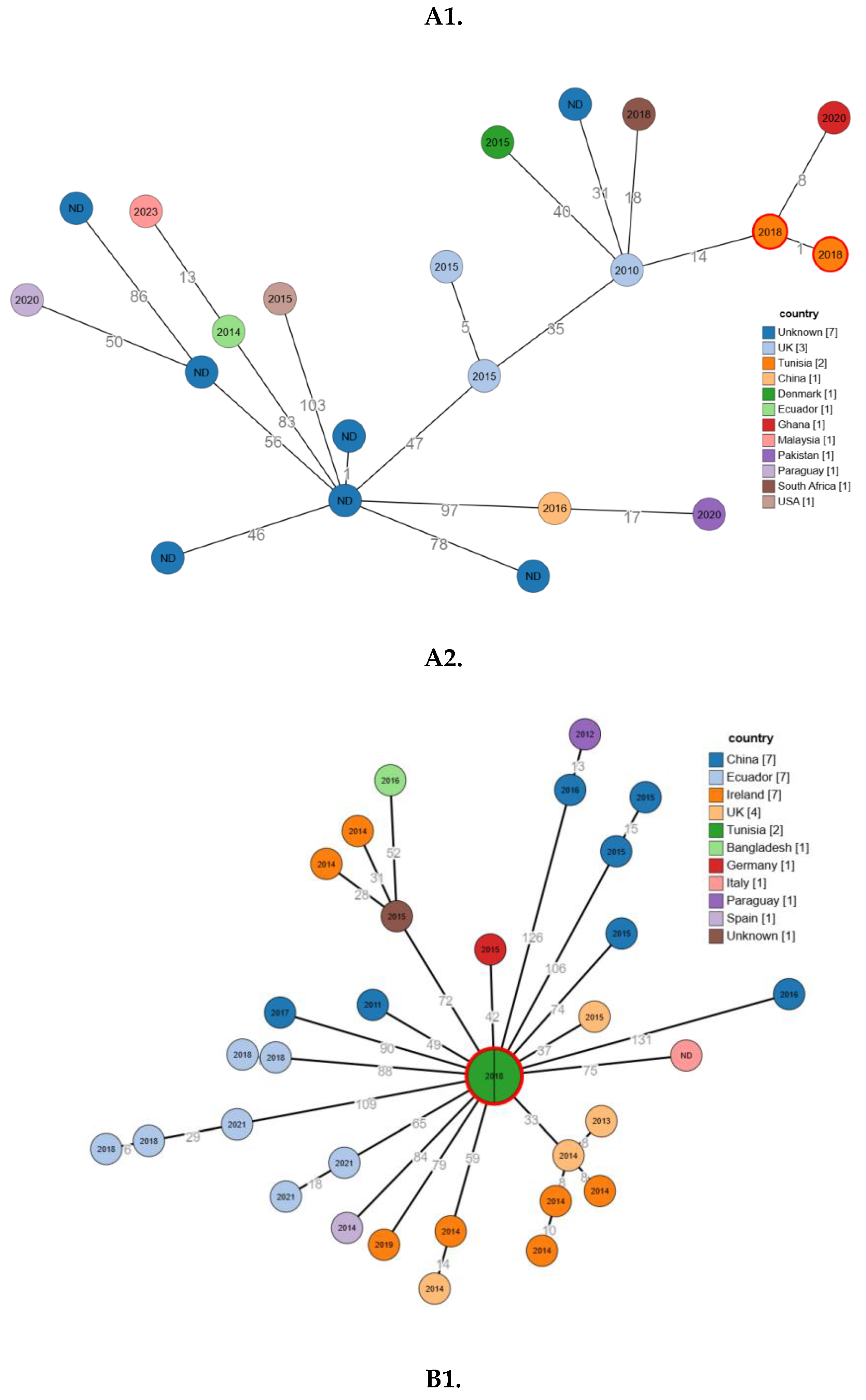

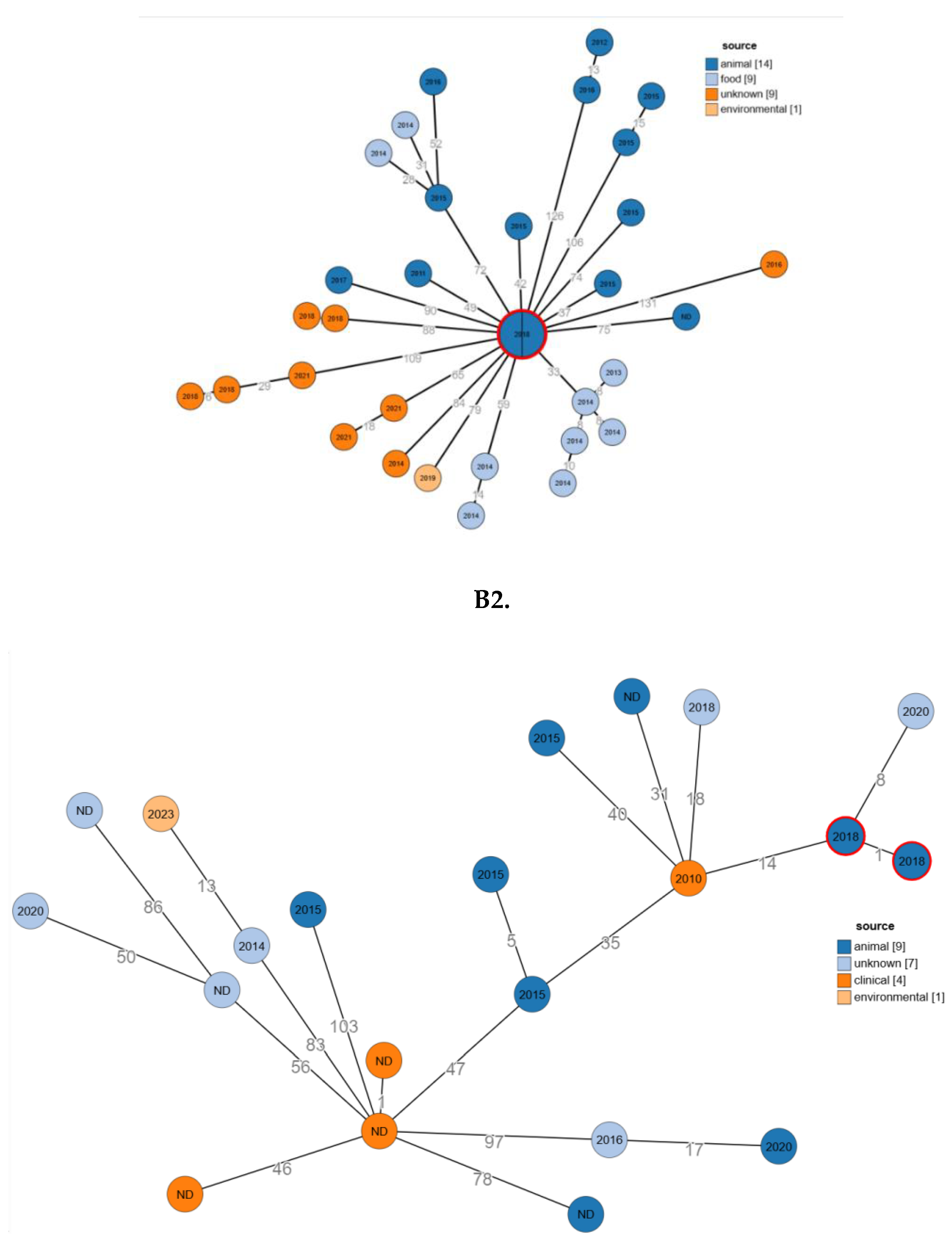

2.6. Phylogenetic Relatedness

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolation and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.2. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation and Whole-Genome Sequencing

4.3. Read Quality Control and De Novo Assembly

4.4. Genome Annotation and CRISPR Analysis

4.5. In Silico Typing and Phylogenetic Context

4.6. Resistome, Virulome and Mobile Genetic Elements

4.7. In Silico Prediction of Human Pathogenic Potential

4.8. Identification of Closely Related Genomes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| BacMet | Bacterial Metal Resistance Genes database |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

| bp | base pairs |

| BV-BRC | Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center |

| CARD | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database |

| CDS | Coding DNA sequences |

| cgMLST | Core-genome multilocus sequence typing |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| ExPEC | Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli |

| GDL | Deoxycholate lactose agar |

| MDR | Multidrug resistant / multidrug resistance |

| MGE | Mobile genetic element(s) |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| PBP3 | Penicillin-binding protein 3 |

| PMQR | Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance |

| QRDR | Quinolone resistance–determining region |

| rMLST | Rbosomal multilocus sequence typing |

| rST | Ribosomal sequence type |

| ST | Sequence type |

| TCDB | Transporter Classification Database |

| VFDB | Virulence Factors of Pathogenic Bacteria database |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO updates list of drug-resistant bacteria most threatening to human health [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-05-2024-who-updates-list-of-drug-resistant-bacteria-most-threatening-to-human-health.

- Leimbach A, Hacker J, Dobrindt U. E. coli as an All-Rounder: The Thin Line Between Commensalism and Pathogenicity. In: Dobrindt U, Hacker JH, Svanborg C, editors. Between Pathogenicity and Commensalism [Internet]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013 [cited 2025 Nov 24]. p. 3–32. (Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; vol. 358). Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/82_2012_303.

- Park, SH. Third-generation cephalosporin resistance in gram-negative bacteria in the community: a growing public health concern. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29(1):27.

- Velazquez-Meza ME, Galarde-López M, Carrillo-Quiróz B, Alpuche-Aranda CM. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet World. 2022 Mar 28;743–9. [CrossRef]

- Torres RT, Cunha MV, Araujo D, Ferreira H, Fonseca C, Palmeira JD. A walk on the wild side: Wild ungulates as potential reservoirs of multi-drug resistant bacteria and genes, including Escherichia coli harbouring CTX-M beta-lactamases. Environ Pollut. 2022 Aug;306:119367. [CrossRef]

- Mahjoub Khachroub A, Souguir M, Châtre P, Elhouda Bouhlel N, Jaidane N, Drapeau A, et al. Carriage Rate of Enterobacterales Resistant to Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporins in the Tunisian Population. Pathogens. 2024 ;13(8):624. 26 July. [CrossRef]

- Hmidi I, Souguir M, Métayer V, Drapeau A, François P, Madec JY, et al. Characterization of Enterobacterales Resistant to Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporins Isolated from Meat in Tunisia. J Food Prot. 2025 Oct;88(11):100610. [CrossRef]

- Ncir S, Haenni M, Châtre P, Drapeau A, François P, Chaouch C, et al. Occurrence and persistence of multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales isolated from urban, industrial and surface water in Monastir, Tunisia. Sci Total Environ. 2024 May;926:171562.

- De Witte C, Vereecke N, Theuns S, De Ruyck C, Vercammen F, Bouts T, et al. Presence of Broad-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Zoo Mammals. Microorganisms. 2021 Apr 14;9(4):834. [CrossRef]

- Miltgen G, Martak D, Valot B, Kamus L, Garrigos T, Verchere G, et al. One Health compartmental analysis of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli on Reunion Island reveals partitioning between humans and livestock. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022 Apr 27;77(5):1254–62. [CrossRef]

- Lagerstrom KM, Hadly EA. The under-investigated wild side of Escherichia coli : genetic diversity, pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance in wild animals. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2021 Apr 14;288(1948):rspb.2021.0399, 20210399.

- Pal C, Bengtsson-Palme J, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ. Co-occurrence of resistance genes to antibiotics, biocides and metals reveals novel insights into their co-selection potential. BMC Genomics. 2015 Dec;16(1):964. [CrossRef]

- Engin AB, Engin ED, Engin A. Effects of co-selection of antibiotic-resistance and metal-resistance genes on antibiotic-resistance potency of environmental bacteria and related ecological risk factors. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2023 Mar;98:104081.

- Ewers C, De Jong A, Prenger-Berninghoff E, El Garch F, Leidner U, Tiwari SK, et al. Genomic Diversity and Virulence Potential of ESBL- and AmpC-β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Strains From Healthy Food Animals Across Europe. Front Microbiol. 2021 Apr 1;12:626774.

- Menezes J, Frosini SM, Weese S, Perreten V, Schwarz S, Amaral AJ, et al. Transmission dynamics of ESBL/AmpC and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales between companion animals and humans. Front Microbiol. 2024 Sept 3;15:1432240.

- Manges AR, Johnson JR. Food-Borne Origins of Escherichia coli Causing Extraintestinal Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Sept 1;55(5):712–9.

- Manges AR, Geum HM, Guo A, Edens TJ, Fibke CD, Pitout JDD. Global Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) Lineages. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019 ;32(3):e00135-18. 19 June. [CrossRef]

- Jolley KA, Bliss CM, Bennett JS, Bratcher HB, Brehony C, Colles FM, et al. Ribosomal multilocus sequence typing: universal characterization of bacteria from domain to strain. Microbiology. 2012 Apr 1;158(4):1005–15.

- Mitić D, Bolt EL, Ivančić-Baće I. CRISPR-Cas adaptation in Escherichia coli. Biosci Rep. 2023 Mar 31;43(3):BSR20221198. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Zhao H, Zhou Z, Miao Y, Li R, Yang B, et al. Characterization of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates That Cause Diarrhea in Sheep in Northwest China. Vignoli R, editor. Microbiol Spectr. 2022 Aug 31;10(4):e01595-22. [CrossRef]

- Russell CW, Fleming BA, Jost CA, Tran A, Stenquist AT, Wambaugh MA, et al. Context-Dependent Requirements for FimH and Other Canonical Virulence Factors in Gut Colonization by Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Payne SM, editor. Infect Immun. 2018 Mar;86(3):e00746-17.

- Lagerstrom KM, Scales NC, Hadly EA. Impressive pan-genomic diversity of E. coli from a wild animal community near urban development reflects human impacts. iScience [Internet]. 2024 Mar 15 [cited 2025 Nov 25];27(3). Available from. [CrossRef]

- Perewari DO, Otokunefor K, Agbagwa OE. Tetracycline-Resistant Genes in Escherichia coli from Clinical and Nonclinical Sources in Rivers State, Nigeria. Genovese C, editor. Int J Microbiol. 2022 ;2022:1–5. 9 July.

- Ben Yahia H, Ben Sallem R, Tayh G, Klibi N, Ben Amor I, Gharsa H, et al. Detection of CTX-M-15 harboring Escherichia coli isolated from wild birds in Tunisia. BMC Microbiol. 2018 Dec;18(1):26.

- Harbaoui S, Ferjani S, Abbassi MS, Saidani M, Gargueh T, Ferjani M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and predominance of blaCTX-M-15 in cefotaxime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates colonizing hospitalized children in Tunisia. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2022 Dec 1;75(6):1460–74.

- Dziri R, Klibi N, Alonso CA, Jouini A, Ben Said L, Chairat S, et al. Detection of CTX-M-15-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates of Lineages ST131-B2 and ST167-A in Environmental Samples of a Tunisian Hospital. Microb Drug Resist. 2016 July;22(5):399–403.

- Awosile B, Fritzler J, Levent G, Rahman MdK, Ajulo S, Daniel I, et al. Genomic Characterization of Fecal Escherichia coli Isolates with Reduced Susceptibility to Beta-Lactam Antimicrobials from Wild Hogs and Coyotes. Pathogens. 2023 ;12(7):929. 11 July.

- Rodríguez-González MJ, Jiménez-Pearson MA, Duarte F, Poklepovich T, Campos J, Araya-Sánchez LN, et al. Multidrug-Resistant CTX-M and CMY-2 Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Healthy Household Dogs from the Great Metropolitan Area, Costa Rica. Microb Drug Resist Larchmt N. 2020 Nov;26(11):1421–8.

- Komp Lindgren P, Karlsson Å, Hughes D. Mutation Rate and Evolution of Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Escherichia coli Isolates from Patients with Urinary Tract Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003 Oct;47(10):3222–32.

- Jacoby GA, Strahilevitz J, Hooper DC. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Microbiol Spectr. 2014 Oct;2(5).

- Author 1, A.B. Title of Thesis. Level of Thesis, Degree-Granting University, Location of University, Date of Completion.

- Title of Site. Available online: URL (accessed on Day Month Year).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and dataontained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

| Isolate ID | Host | Genome length (bp) | GC (%) | Contigs | N50 (bp) | L50 | CDS | tRNA | rRNA | AMR genes (CARD) | Virulence genes (VFDB) | Metal-resistance genes (BacMet) | Transporters (TCDB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ec1 | Llama | 5017117 | 50,55 | 81 | 188611 | 9 | 4980 | 75 | 4 | 68 | 120 | 145 | 973 |

| Ec2 | Lion | 4951530 | 50,64 | 73 | 251976 | 8 | 4794 | 80 | 3 | 62 | 114 | 144 | 945 |

| Ec3 | Hyena | 4918706 | 50,62 | 68 | 180087 | 9 | 4735 | 76 | 3 | 61 | 114 | 142 | 942 |

| Ec4 | Tiger | 5025665 | 50,55 | 97 | 193171 | 8 | 5016 | 75 | 5 | 68 | 131 | 146 | 977 |

| Sample ID | SRA Run accession | Biosample accession | Sequence Type | Serotype | Phylogroup | Antibiotic Resistance Genes | Chromosomal Mutations |

Virulence Genes | Plasmids | Insertion Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ec1 | SRR36138962 | SAMN53358001 | ST162 | O134:H19 | B1 | vanG, blaCMY-2, blaTEM-1B, aadA5, dfrA17, catA1, tet(B), blaEC-18, aph(6)-Id, sul2, aph(3’)-Ia, aph(3’’)-Ib | gyrA (S83L, D87N), parC (S80I), GlpT (E448K), PBP3 (D350N, S357N), AcrAB-TolC with AcrR mutation, AcrAB-TolC with MarR mutations (Y137H, G103S), soxR and soxS mutations | anr, astA, cib, csgA, cvaC, etsC, fdeC, fimH32, fumC65, gad, hlyE, hlyF, hra, iroN, iss, iucC, iutA, lpfA, mchF, nlpI, ompT, papC, sitA, terC, traJ, traT, yehA, yehB, yehC, yehD, yghJ | ColpVC, IncFIB, IncFIC(FII), IncI1-I(Alpha), IncQ1 | ISEc9, IS629, MITEEc1 (IS630), IS26 |

| Ec2 | SRR36138961 | SRR36138961 | ST69 | O15:H18 | D | vanG, blaEC-8, qnrS1, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1B, aph(6)-Id, aph (3’’)-Ib, sul2, dfrA14 | GlpT (E448K),cyaA (S352T), PBP3 (D350N, S357N), AcrAB-TolC with AcrR mutation, AcrAB-TolC with MarR mutations (Y137H, G103S), soxS, soxR |

csgA, fdeC, fimH27, fumC35, gad, hlyE, iss, lpfA, nlpI, ompT, sitA, terC, yehA, yehB, yehC, yehD, yghJ, AslA, chuA, eilA, fyuA, hha, irp2, kpsE, kpsMIII_K96 | IncY | ISEc9, ISKpn19, MITEEc1, ISEc46, ISEc38, IS4, ISSfl10, IS629, ISEc31, IS26 |

| Ec3 | SRR36138960 | SAMN53358003 | ST69 | O15:H18 | D | vanG, blaEC-8, sul2, aph (3’’)-Ib, aph (6)-Id, blaTEM-1B, blaCTX-M-15, qnrS1, dfrA14 | GlpT (E448K), cyaA (S352T), PBP3 (D350N, S357N), AcrAB-TolC with AcrR, soxS, soxR, AcrAB-TolC with MarR mutations (Y137H, G103S) |

csgA, fdeC, fimH27, fumC35, gad, hlyE, iss, lpfA, nlpI, ompT, sitA, terC, yehA, yehB, yehC, yehD, yghJ, AslA, chuA, eilA, fyuA, hha, irp2, kpsE, kpsMIII_K96 | Col(MG828), IncY | ISEc9, MITEEc1, ISEc46, IS4, ISEc38, ISSfl10, IS629, ISEc31, IS26 |

| Ec4 | SRR36138959 | SAMN53358004 | ST162 | O134:H19 | B1 | vanG, blaCMY-2, blaTEM-1B, blaEC-18, catA1, aadA5, tet(B), sul2, aph (6)-Id, aph (3’)-Ia, dfrA17 | GlpT (E448K), gyrA (D87N, S83L), PBP3 (D350N, S357N), parC (S80I), AcrAB-TolC with AcrR mutation, soxR, soxS, AcrAB-TolC with MarR mutations (Y137H, G103S) | anr, astA, cib, csgA, cvaC, etsC, fdeC, fimH32, fumC65, gad, hlyE, hlyF, hra, iroN, iss, iucC, iutA, lpfA, mchF, nlpI, ompT, papC, sitA, terC, traJ, traT, yehA, yehB, yehC, yehD, yghJ | ColpVC, IncFIB, IncFIC(FII), IncI1-I(Alpha), IncQ1, Col(MG828) | Tn2, ISEc9, MITEEc1, IS629, IS26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).