Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Isolation and Identification

2.3. Susceptibility Testing

2.4. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.5. Assembly and Annotation

2.6. Resistome, Virulome Genome Sequence Typing

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Case Description

3.2. Phenotypic, Biochemical Characterization and Resistance Profile

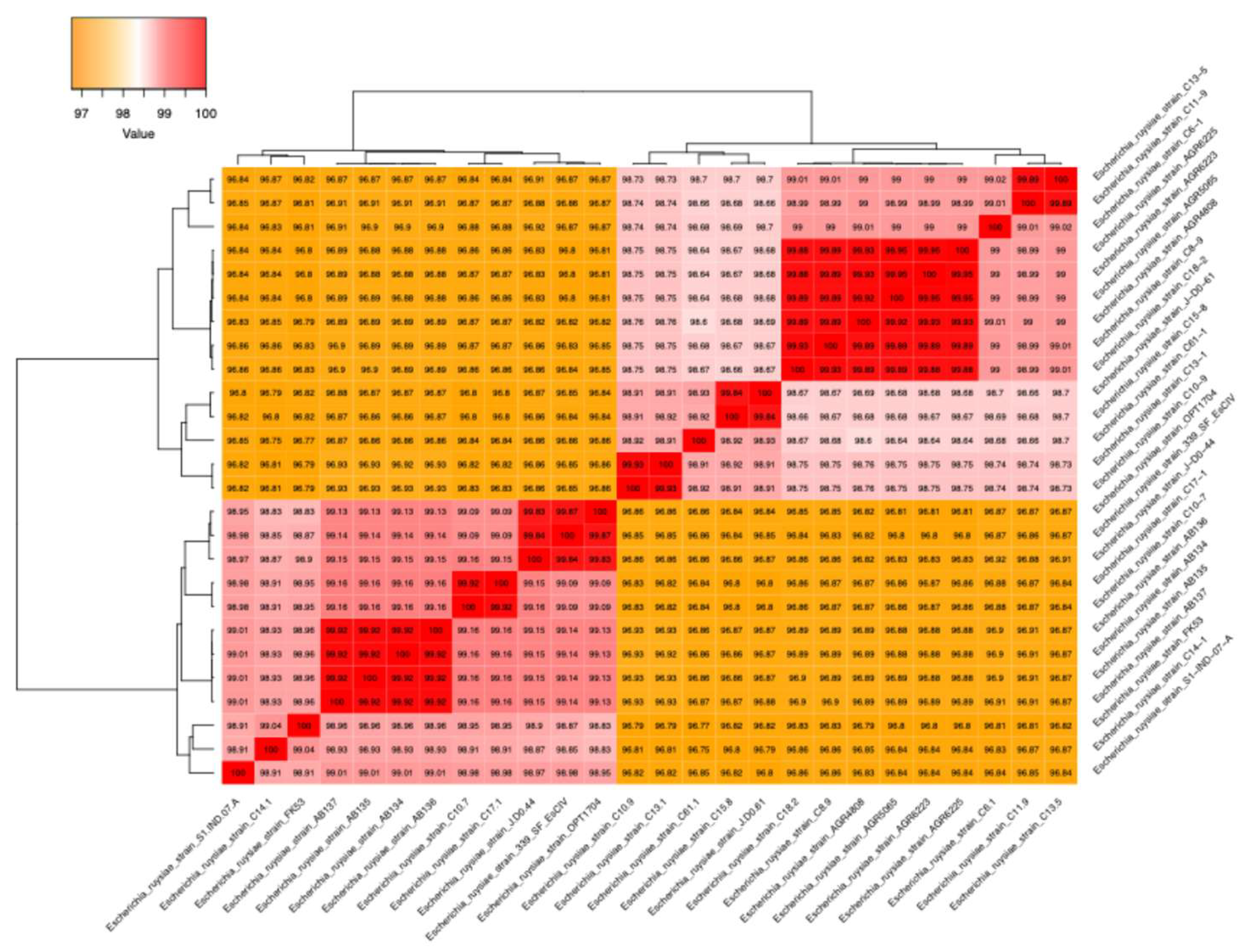

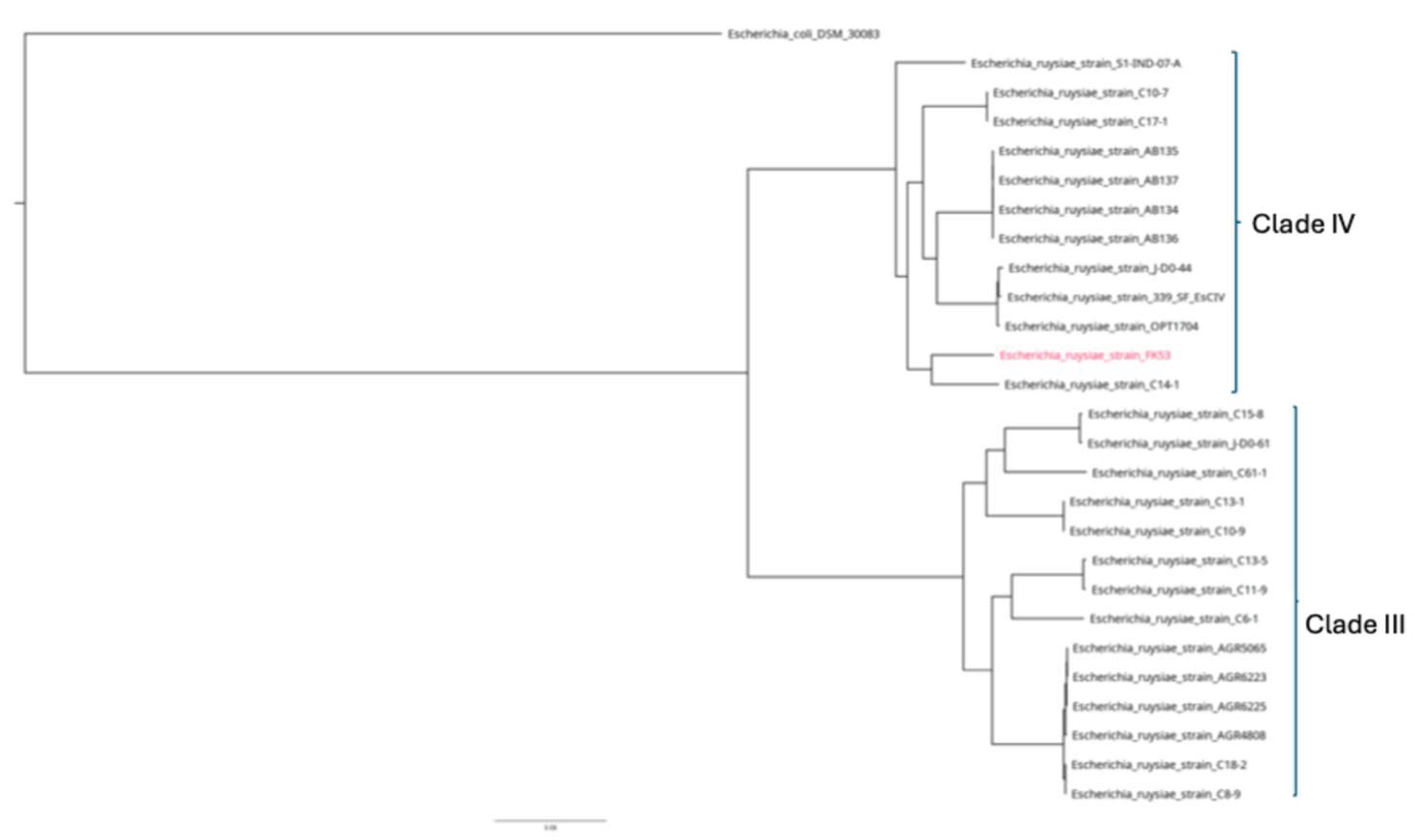

3.3. Genomics Features and Challenges in the Strain Identification

3.4. Resistome, Virulome and Mobilome of FK53-34

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tenaillon, O.; Skurnik, D.; Picard, B.; Denamur, E. The Population Genetics of Commensal Escherichia Coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaper, J.B.; Nataro, J.P.; Mobley, H.L.T. Pathogenic Escherichia Coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OMS Le Genre Escherichia Englobe Les Espèces Commensales et Pathogènes 2018.

- Escherich, T. Die Darmbakterien Des Neugeborenen Und Säuglings. 1885.

- Shulman, S.T.; Friedmann, H.C.; Sims, R.H. Theodor Escherich: The First Pediatric Infectious Diseases Physician? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Putten, B.C.L.; Matamoros, S.; Mende, D.R.; Scholl, E.R.; Consortium†, C.; Schultsz, C. Escherichia Ruysiae Sp. Nov., a Novel Gram-Stain-Negative Bacterium, Isolated from a Faecal Sample of an International Traveller. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D.J.; Davis, B.R.; Steigerwalt, A.G.; Riddle, C.F.; McWhorter, A.C.; Allen, S.D.; Farmer, J.J.; Saitoh, Y.; Fanning, G.R. Atypical Biogroups of Escherichia Coli Found in Clinical Specimens and Description of Escherichia Hermannii Sp. Nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1982, 15, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.J.; Fanning, G.R.; Davis, B.R.; O’Hara, C.M.; Riddle, C.; Hickman-Brenner, F.W.; Asbury, M.A.; Lowery, V.A.; Brenner, D.J. Escherichia Fergusonii and Enterobacter Taylorae, Two New Species of Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Clinical Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985, 21, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, G.; Cnockaert, M.; Janda, J.M.; Swings, J. Escherichia Albertii Sp. Nov., a Diarrhoeagenic Species Isolated from Stool Specimens of Bangladeshi Children. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Jin, D.; Lan, R.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Q.; Dai, H.; Lu, S.; Hu, S.; Xu, J. Escherichia Marmotae Sp. Nov., Isolated from Faeces of Marmota Himalayana. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2130–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, K.; Tanabe, M.; Takizawa, S.; Kasahara, S.; Denda, T.; Koide, S.; Hayashi, W.; Nagano, Y.; Nagano, N. Zoonotic Potential and Antimicrobial Resistance of Escherichia Spp. in Urban Crows in Japan-First Detection of E. Marmotae and E. Ruysiae. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 100, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddi, G.; Piras, F.; Gymoese, P.; Torpdahl, M.; Meloni, M.P.; Cuccu, M.; Migoni, M.; Cabras, D.; Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M.; De Santis, E.P.L.; et al. Pathogenic Profile and Antimicrobial Resistance of Escherichia Coli, Escherichia Marmotae and Escherichia Ruysiae Detected from Hunted Wild Boars in Sardinia (Italy). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 421, 110790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Madueno, E.I.; Aldeia, C.; Sendi, P.; Endimiani, A. Escherichia Ruysiae May Serve as a Reservoir of Antibiotic Resistance Genes across Multiple Settings and Regions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01753–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas, Michael. ; Hillenkamp, Franz. Laser Desorption Ionization of Proteins with Molecular Masses Exceeding 10,000 Daltons. Anal. Chem. 1988, 60, 2299–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani-Kurkdjian, P. Chapitre 15 - Diagnostic bactériologique des infections gastro-intestinales.

- Biosafety in the Laboratory: Prudent Practices for Handling and Disposal of Infectious Materials; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 1989; p. 1197; ISBN 978-0-309-03975-8.

- Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J. 301 Control of Hospital Waste.

- Avril, J.L. Technique d’une Coproculture. Médecine Mal. Infect. 1979, 9, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, S.B.; Ratnam, S. Sorbitol-MacConkey Medium for Detection of Escherichia Coli 0157:H7 Associated with Hemorrhagic Colitis. J CLIN MICROBIOL.

- March, S.B.; Ratnam, S. Sorbitol-MacConkey Medium for Detection of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Associated with Hemorrhagic Colitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1986, 23, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thermo Scientific Kit de d’extraction de l’ADN à Partir de Divers Échantillons Biologiques 2022.

- Emilie Cardot Martin Identification Des Microorganismes Pathogènes Par Spectrométrie de Masse de Type MALDI TOF En Microbiologie Médicale 2020.

- Osthoff, M.; Gürtler, N.; Bassetti, S.; Balestra, G.; Marsch, S.; Pargger, H.; Weisser, M.; Egli, A. Impact of MALDI-TOF-MS-Based Identification Directly from Positive Blood Cultures on Patient Management: A Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegger, M.; Leihof, R.F.; Baig, S.; Sieber, R.N.; Thingholm, K.R.; Marvig, R.L.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Nielsen, K.L. A Snapshot of Diversity: Intraclonal Variation of Escherichia Coli Clones as Commensals and Pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 310, 151401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUCAST Comité de l’antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie 2023.

- EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters 2024.

- Animal Health Institute, Sebeta, Ethiopia; K, E.; K, L.; Animal Health Institute, Sebeta, Ethiopia Review on Illumina Sequencing Technology. Austin J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husb. 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Illumina MiniSeq System Guide. Retrieved from. 2023.

- Aworh, M.K.; Ekeng, E.; Nilsson, P.; Egyir, B.; Owusu-Nyantakyi, C.; Hendriksen, R.S. Extended-Spectrum ß-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia Coli Among Humans, Beef Cattle, and Abattoir Environments in Nigeria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 869314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, G.; Fang, L.; Geng, R.; Shi, S.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Lin, M.; Chen, J.; Si, Y.; et al. The Marine-Origin Exopolysaccharide-Producing Bacteria Micrococcus Antarcticus HZ Inhibits Pb Uptake in Pakchoi (Brassica Chinensis L.) and Affects Rhizosphere Microbial Communities. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chklovski, A.; Parks, D.H.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM2: A Rapid, Scalable and Accurate Tool for Assessing Microbial Genome Quality Using Machine Learning. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: Memory Friendly Classification with the Genome Taxonomy Database.

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Moreira, B.; Vinuesa, P. GET_HOMOLOGUES, a Versatile Software Package for Scalable and Robust Microbial Pangenome Analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7696–7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçais, G.; Delcher, A.L.; Phillippy, A.M.; Coston, R.; Salzberg, S.L.; Zimin, A. MUMmer4: A Fast and Versatile Genome Alignment System. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A Tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post-Analysis of Large Phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Lam, T.T.; Max Carvalho, L.; Pybus, O.G. Exploring the Temporal Structure of Heterochronous Sequences Using TempEst (Formerly Path-O-Gen). Virus Evol. 2016, 2, vew007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: In-Depth Characterization and Visualization of Bacterial Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W484–W492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. ABRicate, Un Logiciel Combinanr Différentes Bases de Données Pour Le Dépistage de Masse Des Contigs Pour La Résistance Aux Antimicrobiens Ou Les Gènes de Virulence 2020.

- Florensa, A.F.; Kaas, R.S.; Clausen, P.T.L.C.; Aytan-Aktug, D.; Aarestrup, F.M. ResFinder – an Open Online Resource for Identification of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in next-Generation Sequencing Data and Prediction of Phenotypes from Genotypes. Microb. Genomics 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.-L.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic Resistome Surveillance with the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, gkz935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Padmanabhan, B.R.; Diene, S.M.; Lopez-Rojas, R.; Kempf, M.; Landraud, L.; Rolain, J.-M. ARG-ANNOT, a New Bioinformatic Tool To Discover Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Bacterial Genomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, N.; Doster, E.; Worley, H.; Pinnell, L.J.; Bravo, J.E.; Ferm, P.; Marini, S.; Prosperi, M.; Noyes, N.; Morley, P.S.; et al. MEGARes and AMR++, v3.0: An Updated Comprehensive Database of Antimicrobial Resistance Determinants and an Improved Software Pipeline for Classification Using High-Throughput Sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D744–D752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: A General Classification Scheme for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D912–D917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessonov, K.; Laing, C.; Robertson, J.; Yong, I.; Ziebell, K.; Gannon, V.P.J.; Nichani, A.; Arya, G.; Nash, J.H.E.; Christianson, S. ECTyper: In Silico Escherichia Coli Serotype and Species Prediction from Raw and Assembled Whole-Genome Sequence Data. Microb. Genomics 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GNU Parallel 20230522; charles; Zenodo, 2023;

- Clermont, O.; Gordon, D.; Denamur, E. Guide to the Various Phylogenetic Classification Schemes for Escherichia Coli and the Correspondence among Schemes. Microbiology 2015, 161, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Putten, B.C.L.; Matamoros, S.; Mende, D.R.; Scholl, E.R.; Consortium†, C.; Schultsz, C. Escherichia Ruysiae Sp. Nov., a Novel Gram-Stain-Negative Bacterium, Isolated from a Faecal Sample of an International Traveller. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, N.M.; Gilroy, R.; Getino, M.; Foster-Nyarko, E.; Van Vliet, A.H.M.; La Ragione, R.M.; Pallen, M.J. Remarkable Genomic Diversity among Escherichia Isolates Recovered from Healthy Chickens. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dione, N.; Mlaga, K.D.; Liang, S.; Jospin, G.; Marfori, Z.; Alvarado, N.; Scarsella, E.; Uttarwar, R.; Ganz, H.H. Comparative Genomic and Phenotypic Description of Escherichia Ruysiae: A Newly Identified Member of the Gut Microbiome of the Domestic Dog. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1558802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauget, M.; Valot, B.; Bertrand, X.; Hocquet, D. Can MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Reasonably Type Bacteria? Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, A.R.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Walkty, A.; Baxter, M.R.; Denisuik, A.J.; McCracken, M.; Mulvey, M.R.; Adam, H.J.; Bay, D.; Zhanel, G.G. Comparison of Phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Results and WGS-Derived Genotypic Resistance Profiles for a Cohort of ESBL-Producing Escherichia Coli Collected from Canadian Hospitals: CANWARD 2007–18. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2825–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, M.J.; Ekelund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Canton, R.; Doumith, M.; Giske, C.; Grundman, H.; Hasman, H.; Holden, M.T.G.; Hopkins, K.L.; et al. The Role of Whole Genome Sequencing in Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Bacteria: Report from the EUCAST Subcommittee. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.S.; Jelacic, S.; Habeeb, R.L.; Watkins, S.L.; Tarr, P.I. The Risk of the Hemolytic–Uremic Syndrome after Antibiotic Treatment ofEscherichia ColiO157:H7 Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1930–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, W.; Jiang, X.; Yao, T.; Wang, L.; Yang, B. Virulence-Related O Islands in Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia Coli O157:H7. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1992237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Gewirtz, A. Together Forever: Bacterial–Viral Interactions in Infection and Immunity. Viruses 2018, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.C. Coevolution of the Organization and Structure of Prokaryotic Genomes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a018168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, L.S.; Leplae, R.; Summers, A.O.; Toussaint, A. Mobile Genetic Elements: The Agents of Open Source Evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casacuberta, E.; González, J. The Impact of Transposable Elements in Environmental Adaptation. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 1503–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhas, M.; Van Der Meer, J.R.; Gaillard, M.; Harding, R.M.; Hood, D.W.; Crook, D.W. Genomic Islands: Tools of Bacterial Horizontal Gene Transfer and Evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.; Czeczulin, J.R.; Harrington, S.; Hicks, S.; Henderson, I.R.; Le Bouguénec, C.; Gounon, P.; Phillips, A.; Nataro, J.P. A Novel Dispersin Protein in Enteroaggregative Escherichia Coli. J. Clin. Invest. 2002, 110, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishi, J.; Sheikh, J.; Mizuguchi, K.; Luisi, B.; Burland, V.; Boutin, A.; Rose, D.J.; Blattner, F.R.; Nataro, J.P. The Export of Coat Protein from Enteroaggregative Escherichia Coli by a Specific ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter System. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 45680–45689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfan, M.J.; Torres, A.G. Molecular Mechanisms That Mediate Colonization of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli Strains. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S. Pathogenesis of Bacterial Meningitis: From Bacteraemia to Neuronal Injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kim, K.S. Role of OmpA and IbeB in Escherichia Coli K1 Invasion of Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Pediatr. Res. 2002, 51, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascales, E.; Buchanan, S.K.; Duché, D.; Kleanthous, C.; Lloubès, R.; Postle, K.; Riley, M.; Slatin, S.; Cavard, D. Colicin Biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 158–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Hoede, C.; Tenaillon, O.; Barbe, V.; Baeriswyl, S.; Bidet, P.; Bingen, E.; Bonacorsi, S.; Bouchier, C.; Bouvet, O.; et al. Organised Genome Dynamics in the Escherichia Coli Species Results in Highly Diverse Adaptive Paths. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, B.M.; Ben Zakour, N.L.; Stanton-Cook, M.; Phan, M.-D.; Totsika, M.; Peters, K.M.; Chan, K.G.; Schembri, M.A.; Upton, M.; Beatson, S.A. The Complete Genome Sequence of Escherichia Coli EC958: A High Quality Reference Sequence for the Globally Disseminated Multidrug Resistant E. Coli O25b:H4-ST131 Clone. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, J.W.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Kesterson, R.A.; Feng, X. Genetic Ablation of CD68 Results in Mice with Increased Bone and Dysfunctional Osteoclasts. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, S.D.; Hamburger, M.E.; Moorman, A.C.; Wood, K.C.; Palella, F.J., Jr. ; HIV Outpatient Study Investigators Factors Associated with Maintenance of Long-Term Plasma Human Immunodeficiency Virus RNA Suppression. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, N.T.; Plunkett, G.; Burland, V.; Mau, B.; Glasner, J.D.; Rose, D.J.; Mayhew, G.F.; Evans, P.S.; Gregor, J.; Kirkpatrick, H.A.; et al. Genome Sequence of Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia Coli O157:H7. Nature 2001, 409, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.R.; Yang, R.; Clifford, J.L.; Watson, D.; Campbell, R.; Getnet, D.; Kumar, R.; Hammamieh, R.; Jett, M. Functional Heatmap: An Automated and Interactive Pattern Recognition Tool to Integrate Time with Multi-Omics Assays. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subtract tested | FK53-34 (this study) | E. ruysiae AB136 [50] | E.coli [11] |

| ONPG | + | + | + |

| ADH | - | - | + |

| LDC | - | - | + |

| ODC | + | + | + |

| CIT | + | - | - |

| H2S | - | - | - |

| URE | - | - | - |

| TDA | + | - | - |

| IND | - | +/- | + |

| VP | - | + | - |

| GEL | - | - | - |

| GLU | + | + | + |

| MAN | + | + | + |

| INO | - | - | - |

| SOR | + | + | + |

| RHA | + | + | + |

| SAC | - | - | + |

| MEL | + | - | - |

| AMY | - | - | - |

| ARA | + | + | + |

| Antibiotic | Acronyms | Load (µg) | Interpretation |

| Ciprofloxacin | CIP | 5 | S |

| Cefepime | FEP | 30 | S |

| Aztreonam | ATM | 30 | S |

| Cefotaxime | CTX | 30 | S |

| Ticarcillin-clavulanate | TCC | 75 | S |

| Amoxicillin | AMO | 20 | S |

| Cefoxitin | FOX | 30 | S |

| Cefuroxime | CXM | 30 | S |

| Ceftazidime | CAZ | 10 | S |

| Nalidixic acid | NAL | 30 | S |

| Isolate | (AGly) aadA1-pm | (Bla)PBP_Ecoli | (Bla) ampH_Ecoli | (Bla) blaLAP-2 | (Flq)qnr-S1 | (Sul)sul2 | (Tet)tetA | (Tet)tetR | CTX | blaEC-15 | blaEC-8 |

| ABC134 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| ABC135 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| ABC136 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| ABC137 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C10-7 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C10-9 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C11-9 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - |

| C13-1 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C13-5 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C14-1 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C15-8 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - |

| C17-1 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C18-2 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C6-1 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| C61-1 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| C8-9 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| OPT1704 | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - |

| S1-IND-07-A | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| FK53-34 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| Isolates | aap/aspU | aatA | aatB | aatC | aatP | agn43 | senB | traJ | trat |

| ABC134 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ABC135 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ABC136 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ABC137 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C10-7 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C10-9 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C11-9 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C13-1 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C13-5 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C14-1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C15-8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C17-1 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C18-2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C6-1 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C61-1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C8-9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| OPT1704 | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| S1-IND-07-A | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FK53-34 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).