1. Introduction

For over three centuries, the city of Venice operated one of the most ambitious and enduring public health infrastructures in premodern Europe (

1, 2): the quarantine archipelago of the Venetian lagoon (

Figure 1A). At the heart of this system stood Lazzaretto Vecchio, an artificial island designated in 1423 as the first permanent quarantine hospital (

Lazzaretto) for maritime travelers arriving with suspected infectious diseases (

3, 4) (

Figure 1B). Long before germ theory, and centuries before modern biocontainment facilities (

2, 5), Venice built a physical and bureaucratic firewall against contagion, sequestering ships, goods, animals, and people within a regulated space for 40 days (

quarantena) to interrupt transmission before it reached the city’s densely populated core.

Lazzaretto Vecchio was more than a quarantine hospital; it was a site of controlled death. Those who failed to recover during their mandatory isolation, both travelers and residents, were not returned to their home parishes or family tombs. Instead, they were buried on the island itself, often in institutional pits managed by health officials and grave crews. Over time, the island became an unintentional archive of infectious mortality: a mortuary record of the resident and the foreign, marked by suspicion of plague or other epidemic threats. In theory, the site should hold the physical remnants of centuries of outbreak management, including tens of thousands of bodies deposited during crisis years (4, 6, 7), particularly during the catastrophic epidemics of 1576 and 1630. This expectation is reinforced by historical records. During the devastating plague of 1576, Venice lost an estimated 50,000 lives, nearly one third of its population, and again in 1630, approximately 46,000 died in a single year, despite strict quarantine enforcement.

The Venetian Republic maintained one of Europe’s earliest formal public health bureaucracies, the Provveditori alla Sanità (Health Magistracy), established in 1486 and endowed with policing, surveillance, and burial authority(4). These magistrates directed maritime cordons, inspected ships and goods, issued “sanitary passes,” and ordered the confinement and burial of suspected plague victims, including Venetian residents, on the quarantine islands (4). The Venetian system appears to have been effective in later centuries (3, 8): it dampened the impact of the Neapolitan plague of 1656–1658 and suffered no major mass-fatality plagues thereafter, unlike Marseille or London (9, 10). With a population fluctuating between roughly 140,000 and 170,000 during major epidemic periods, Venice engineered what was, for centuries, the most centralized epidemic-control system in Europe.

Yet the physical burial capacity of Lazzaretto Vecchio was inherently constrained by its small size and shallow depth as an artificial island. The 1,559 individuals excavated to date, representing perhaps 5–15% of the island’s total burial capacity (11, 12), likely account for less than 1% of all infectious-disease deaths recorded for Venice, even when additional interments at Lazzaretto Nuovo for less severe cases are considered. This striking disparity between the archaeological evidence and the documented demographic toll necessitates a reassessment of how the Venetian Republic managed, concealed, or extinguished epidemic mortality within its controlled spaces.

2. The Paradox of the Missing Mortality Signal

Preliminary archaeological investigations at Lazzaretto Vecchio reveal a demographic and depositional pattern that diverges sharply from the high-density crisis burials documented elsewhere (13-16). For example, the well-studied East Smithfield cemetery in London, a purpose-built Black Death burial ground, contained long mass-burial trenches with hundreds of individuals stacked in multiple layers in two large trenches, and is estimated to have accommodated approximately 2,400 plague victims in total. By contrast, the Venetian site displays only small burial trenches, modest numbers of interments (11) (17), and no clear stratigraphic evidence of a high-mortality mass event.

The temporal scale of deposition presents a striking paradox. Typical crisis cemeteries such as East Smithfield or La Corderie were filled within months, each preserving the demographic cross-section of a single epidemic wave (9, 18, 19). In contrast, Venice’s quarantine island operated continuously for nearly three centuries, receiving both travelers and residents who died under isolation. If most plague and infectious deaths documented in Venetian archives, likely numbering in the hundreds of thousands, had been buried on the islands as mandated, the cumulative volume would have exceeded the physical capacity of this small artificial island many times over. Yet the archaeological record remains sparse. This discrepancy cannot be explained by taphonomic loss or limited excavation alone; instead, it signals a fundamental difference in how mortality was produced and managed within Venice’s quarantine system.

This pattern presents a central interpretive problem: if Venice experienced high epidemic mortality and the lazaretti served as the primary designated locus for isolation and interment of suspected infectious individuals, why is the burial signal so limited in scale and intensity? The apparent absence of mass-fatality deposits challenges assumptions about burial practices during epidemic periods and raises the possibility that institutional quarantine altered the demographic and epidemiological signature of mortality.

In this framework, the limited cemetery population may reflect effective containment, selective burial of specific social or mobility groups, or alternative undocumented disposal pathways during peak crisis periods. Understanding this discrepancy is essential for reconstructing Venice’s epidemic dynamics and the evolutionary consequences of long-term containment strategies (

Table 1).

3. Evidence from Historical Narratives

3.1. Death at Home vs. Death in Quarantine

Historical records describe a highly regulated Venetian quarantine system(5, 20). However, they also document significant operational changes during major epidemic surges (5). During peak outbreaks, large numbers of residents were quarantined in their homes rather than transported to the lazaretti, and many died there before any institutional intervention. As Crawshaw (5) notes, “at major outbreaks (1575 and 1630 in particular), most people were not confined to the Old Lazaret” (5). Contemporary accounting by Cornelio Morello (21) reports 50,721 total deaths, of which 19,175 occurred in the two lazaretti, 27,546 within the city, and 4,000 in unspecified locations(5). Thus, most plague victims died outside institutional quarantine settings during large outbreaks.

Yet, according to chronicler Rocco Benedetti (22), even those who died at home were prohibited from burial in ordinary parish cemeteries, reinforcing the exceptional and emergency character of plague-period body management (23).

3.2. Burial in the Lazaretti vs. Emergency Burial Sites

Historical testimony also documents the expansion of emergency burial infrastructure during epidemic crises (5). Under normal conditions, only officially recognized “sick” individuals were transported to the Old Lazaret, while most citizens were quarantined at the New Lazaret (opened 50 years later than the Old Lazaret.

However, when mortality surged, multiple auxiliary sites were activated. Iconographic evidence shows that a ship positioned in the St. Mark’s Basin functioned as a temporary lazaretto, and Sant’Ariano served as a burial ground for people di rispetto (of higher social status) (23). These accounts reveal that burial and treatment practices were far more fragmented, geographically distributed, and crisis-responsive than official regulations suggest, complicating any assumption of uniform institutional control.

3.3. Voluntary Admission Shifting to Enforcement Under Crisis

Evidence from early administrative records supports the role of voluntary civilian participation in the initial centuries of the Venetian quarantine system (4, 5, 20). At the opening of the Old Lazaret in 1423, only individuals entering the city or escorted by physicians could be transported there. In 1447, the Senate appointed two patrices, Pietro Valier and Francesco Foscarini, “to persuade the sick to be admitted to the Lazaretto” (24). As Palmer observes, this reliance on persuasion “suggests that the state was not yet committed to enforcing unpopular measures” (20). Thus, patient consent and civic cooperation were foundational elements of early Venetian public health policy.

However, during the extreme outbreak of 1575–1577, public compliance deteriorated and coercive enforcement replaced persuasion (25). Individuals suspected of infection were escorted under guard by the pizzigamorti (“dead pinchers”) onto boats transporting them to Lazzaretto Vecchio. A decree of the Magistrato alla Sanità dated 22 September 1577 reports “motti che occorrono per causa di peste” (riots that occur because of the plague), requiring officials to temporarily redirect infected persons to the islands of San Clemente and San Giacomo in Paludo to restore order . A further decree on 22 October 1577 prohibited the sale of second-hand goods, imposing penalties of 18 months on the galley for men, a fine of 50 lire for women, and public whipping from San Marco to Rialto (25). Another decree required immediate reporting of illness, threatening capital punishment for concealment: they shall be immediately hanged upon discovery, “apicato per la golla”.

This dramatic shift, from voluntary cooperation to coercive force, illustrates the limits of civic compliance once fear, mortality, and social instability escalated beyond administrative control. It also underscores that quarantine functioned not only as medical intervention but as an emergency governance system capable of rapidly altering legal and social norms.

A contemporary parallel reinforces this dynamic. In Vo’ Euganeo, a town in the Veneto region, of which Venice is the historic capital, where the first COVID-19 death in Europe was reported (26), civilian self-organization initially emerged as residents voluntarily isolated themselves to protect the community. Shortly afterwards, the Italian state military imposed a full compulsory quarantine, even before the virus was fully understood (27). Although radically different in scale and scientific context, the episode similarly demonstrated both the difficulty of epidemic containment in modern societies and the persistence of collective civic responsibility, as emphasized by the former mayor of Vo’ Euganeo (26). This modern example echoes the historical Venetian strategy, in which social cooperation and enforced emergency control intersected in shaping epidemic outcomes.

3.4. Historical Demographic Account of Quarantine

Analysis of official contemporary data, again drawing from Morello as cited by Crawshaw (5), indicates that men were disproportionately admitted to the lazzaretti, while children and women were markedly underrepresented among institutional deaths.

Architecturally, the Old Lazaret contained separate sections for men and women, and under routine, steady-state contagion conditions, it should have produced a demographically balanced burial assemblage. However, during major epidemic peaks, when institutional capacity was overwhelmed and most residents were quarantined and died at home, the Old Lazaret captured only a partial and highly skewed subset of total plague mortality.

The demographic profile described in historical sources therefore reflects individuals admitted under emergency triage conditions rather than a representative sample of Venice’s population. In this sense, the burial assemblage is not a census of Venice’s epidemic dead, but rather a set of selective and crisis-driven institutional intake.

3.5. Effectiveness of the Quarantine System: Contemporary Debate

The effectiveness of the Venetian lazaret system was already a matter of debate during its period of operation (20). Contemporary health officials argued that the most prudent method of limiting contagion was the strict separation of confirmed plague cases from suspected exposures, sending the sick to Lazzaretto Vecchio (Old Lazaret) and those merely exposed to the Lazzaretto Nuovo (New Lazaret). This structure embodied the principle that containment required both medical isolation and logistical compartmentalization. Accordingly, the Old Lazaret was expected to hold the most severe cases, and under this rationale it should, in principle, preserve an archaeological signature of high-intensity epidemic mortality, characteristic of peak outbreak phases.

4. Evidence of Historical Eyewitness Accounts: Rocco Benedetti (1576)

Direct testimony from the Venetian chronicler Rocco Benedetti provides rare and explicit documentation of emergency plague management during the catastrophic outbreak of 1576 (23). His descriptions preserve both the procedural logic and sensory reality of operations at Lazzaretto Vecchio. We reproduce his eyewitness statements verbatim below, together with literal translations.

It is important to note that eyewitness accounts of Rocco Benedetti were written not in Latin or standardized Tuscan Italian, but in ancient Venetian, the administrative and civic language of the sovereign Republic of Venice (23). This linguistic choice is significant: Venetian functioned as a state language, used in government records, maritime law, medical directives, and civic reporting, rather than a regional dialect. Writing in Venetian signals that Benedetti’s testimony reflects an internal Venetian perspective, produced by individuals embedded within the social, political, and epidemiological infrastructure of the city rather than by external observers or later translators. The immediacy and idiomatic specificity of the original text, lexicon such as Lazaretto Vecchio, brusciar, and spoglie da sacrificarsi a Vulcano, capture local practices and attitudes that might otherwise be lost in standardized translation. Thus, the language of the record itself is a form of evidence: it situates these observations within Venice’s own civic narrative and institutional worldview, providing an authentic window into how plague control was experienced, understood, and morally justified by contemporaries.

Benedetti Quote #1 – Initial Response

Venetian (original):

“Allhora i signori Proveditori della Sanità (...) terminarono per lo migliore di mandare quanto prima a Lazaretto Vecchio i feriti a risanarsi, et i sani che sotto un medesimo tetto vivevano con quelli al Lazaretto Novo a far contumacia quaranta giorni. Ordinarono poi col Senato che si brusciassero degli infetti tutte le robbe di casa.”

Translation:

[The Health Office requested to send as soon as possible the injured (by the plague) to the Old Lazaret to recover, and the healthy that lived under the same roof to the New Lazaret to quarantine for forty days. They required along with the Senate that all things in the house belonging to the infected people be burnt].

Benedetti Quote #2 – Transport and Disposal

Venetian (original):

“Ma molto più horribile spettacolo era la quantità delle barche che di continuo su e giù andavano, alcune a Lazareto Vechio cariche de feriti e di morti tutti mischiati insieme, altre a Lazareto Novo cariche di sani (...). Altre poi si vedevano andar fuori a certi luochi dessignati cariche di spoglie da sacrificarsi a Vulcano.”

Translation:

[But more horrible was seeing the quantity of boats that traveled back and forth, some to the Old Lazaret full of injured and deceased all mixed, some to the New Lazaret full of healthy people (…). Other boats then could be seen going to certain locations decided by authorities full of bodies to sacrifice to Vulcan].

Benedetti Quote #3 – Burning on the Island

Venetian (original):

“Ma lassando la città e volgendosi ai Lazaretti, dico in verità che dall’una parte il Lazaretto Vecchio rassembrava l’Inferno, ove da ogni lato usciva puzzore et insopportabil fettore, udivasi del continuo gemere et sospirare, et si vedevano da tutte le hore nuvoli di fumo stendersi in aere largamente per l’abrusciar de corpi.”

Translation:

[But leaving the city aside and talking about the lazarets, I say in truth that the Old Lazaret resembled Hell, where from all sides bad smells and stench came out, there were sighs and cries coming from it, and at all times one could see clouds of smoke extending because of the burning of bodies].

Benedetti Quote #4 – Emergency Mass Cremation at Lido

Venentian (original):

“Dove non si potendo più per la gran puzza abbrusciar i morti fu quindi poco discosto sul Lido, in luogo ditto alla Cavanella, fatto un campo santo, nel quale fatte profondissime cave quivi si ponevano, mettendosi segondo si faceva al detto Lazaretto, una mano de corpi, una di calcina viva et una di terra, et così di mano in mano fino che ne potevano stare, in modo che da un giorno all’altro erano tutti incineriti.”

Translation:

[When it was no longer possible to burn the bodies because of the smells, in the island of Lido, at the location of Cavanella, a cemetery was erected, where inside deep trenches were laid down bodies to burn, layered as bodies, followed by live lime and soil, and stacked as many times as they could, so that from one day to the other they were all burnt].

Taken together, Benedetti’s eyewitness narrative indicates that bodies from the city were not buried but burned, and that mass cremation replaced burial during crisis conditions. While a small number of infected individuals may have survived quarantine, the majority, whether still alive or already dead, were burned immediately upon arrival, consistent with his repeated description of “injured and dead mixed” on transport boats.

It was not the first time that Venice diverged from mainstream Christian expectations. The Venetian Republic maintained a long-standing independence from papal authority, and tensions with the Roman Church over jurisdiction and ritual practice are well documented. This political and cultural autonomy helps explain why emergency mass cremation could be implemented in Venice during epidemic crises, even though such practices would have been unacceptable in most other European settings. As an illustration of Venice’s distinctive relationship to religious symbolism, the winged lion of St. Mark, the central emblem of the Republic, has been recently shown to derive from a reworked pagan figure (28), demonstrating the city’s history of pragmatic adaptation rather than strict religious conformity.

5. Evidence from Archaeology – Burials Structure and Demographics

The burial data from Lazzaretto Vecchio suggests a pattern consistent with steady, long-term containment rather than catastrophic epidemic mortality. Across the excavated sectors, most pits contain only 1–5 individuals, with a small subset of outliers containing up to 81 individuals (17). The overall frequency distribution of burial counts per pit reflects stochastic accumulation over an extended duration, rather than abrupt mass interment. This burial pattern is unexpected for a plague crisis site. In true epidemic emergencies, we typically observe bimodal or exponential distributions, sharp spikes in burial rates, and dense mass-deposition layers associated with overwhelming mortality.

Crucially, no archaeological signatures of acute deposition have been identified: there are no rapid interment horizons, no continuous plague strata, and no spatial compression of remains. Excavation challenges must be acknowledged, only three pits have been fully excavated out of 108 recognized features, due to extensive modern construction (17). Where pits were recovered intact, bodies were found stacked between 1 and 5 layers (17), and observations suggest deposition before rigor mortis, indicating rapid handling rather than prolonged storage(17).

While some pits with up to 81 individuals could represent a single day of mortality during a crisis surge, if the absence of rigor mortis is confirmed, the total excavated minimum number of individuals (MNI) is 1,559 (17). This number is far lower than historical expectations for major epidemic peaks in Venice. If the Lazaretto had handled 50 or more burials per day during peak crises for even a few years, the cemetery would have been rapidly overwhelmed. The absence of such accumulation therefore points to the interpretation that the Lazaretto Vecchio was not the primary burial ground for Venice’s epidemic dead, but instead a controlled quarantine cemetery with limited throughput.

Even more striking is the demographic profile. Children, who typically represent a large share of deaths in plague pits elsewhere, are scarce. At canonical Black Death and later plague cemeteries such as Marseille and Martigues, subadults constitute approximately 24–29% of burials (29), and can reach up to 46% when adolescents are included (30), reflecting household transmission and generalized mortality during uncontrolled outbreaks. In Italy specifically, contemporary witnesses describe overwhelming pediatric mortality, i.e. “Plague of children”. Ranieri di Sardo in Pisa reported 80% mortality among children aged 12 or younger during the 1374 outbreak, and similar patterns were observed in Siena (31).

By contrast, Lazzaretto Vecchio exhibits a pronounced adult bias. Based on archival demographics, 32–37% of the Venetian population at the time were children, and mortality among them was historically high (32). Thus, at least one-third of burials would be expected to be subadults if the site reflected the full spectrum of urban epidemic mortality. Yet, the original archaeological report records only 17.1% children (238 of 1,390 individuals) (17). Within tomb contexts specifically, only 14.2% (24 of 169) were children (17). In the current combined collections, representation is even lower: fewer than 50 children exist among the ~1,300 individuals curated at USF and Bologna, less than 5%. In other words, children are effectively missing from the record.

6. Methods Feasibility and Analytical Framework

6.1. Archaeological Burial and Demographic Analysis

Lazzaretto Vecchio is currently undergoing systematic excavation and recovery of human remains. Approximately 1,200 individuals (of ~1,559 excavated) are curated at USF and partner institutions, representing an unprecedented longitudinal archive for studying epidemic containment, demographic filtering, and pathogen evolution. Burial architecture, stratigraphy, and demographic composition (age, sex, burial grouping, and spatial clustering) will be quantified to evaluate expected signatures of crisis mortality versus controlled quarantine death.

6.2. Radiocarbon Dating & Stratigraphic Modeling

Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating will be integrated with detailed excavation stratigraphy to reconstruct temporal dynamics of deposition. Bayesian chronological modeling will be used to test discontinuities, mortality pulses, or clustering associated with historically documented epidemic peaks (e.g., in 1575-1577; 1630-1631).

6.3. Ancient Pathogen DNA Analysis

Pilot extraction results confirm biomolecular preservation appropriate for ancient pathogen recovery. Standard aDNA authentication protocols, including clean-room extraction, dual-indexed library preparation, partial UDG treatment, and nucleotide-damage profiling will enable retrieval of ancient microbial genomes suitable for phylogenetic reconstruction and evolutionary analyses (33, 34). These data will allow mapping of pathogen introduction, spread, lineage branching, and extinction dynamics within quarantine-contained populations.

6.4. Ancient Human Genetics

Genome-wide SNP capture and next-generation sequencing will support high-resolution characterization of kinship, ancestry, and phylogeographic structure. These approaches enable testing for the expected absence of household or family burial clusters under quarantine isolation, reconstruction of population mobility patterns, and evaluation of immunity-related genetic polymorphisms relevant to plague susceptibility and survival.

6.5. Proteomics and Oral Microbiome

We have demonstrated feasibility of ancient proteomics workflows at USF (34), enabling peptide-based reconstruction of oral microbiome composition, inflammatory markers, and dietary specificity.

6.6. Stable Isotope Analysis: The Veneita Trio Signature

The Venetian Lagoon produces a unique multi-isotope environmental signature, enabling differentiation between lagoon-born individuals and non-locals. We refer to this distinct combination as the “Venetian Trio”:

Strontium (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr): Seawater-derived values precisely clustered at ~0.70914–0.70917, reflecting marine influence on lagoon sediments and bedrock (35-38).

Carbon & Nitrogen (δ¹³C, δ¹⁵N): Elevated values indicate marine protein consumption and wheat-dominant agricultural diets (39).

Oxygen (δ¹⁸O): Tightly constrained drinking-water signatures linked to rain-fed and filtered cistern systems during the 3 centuries of quarantine operation (40).

6.7. Integrated Analytical Framework

This integrated multi-proxy approach, combining archaeological burial analysis, radiocarbon modeling, ancient DNA, proteomics, and multi-isotope geochemistry, provides a rigorous and feasible strategy for evaluating the structure and function of Venice’s quarantine mortality system.

Together, these methods allow testing of key predictions regarding demographic filtering versus representative mortality sampling, local versus non-local population composition, pathogen introduction, extinction, and evolutionary lineage dynamics, and chronological discontinuities indicating burial gaps associated with emergency rapid-disposal regimes.

7. Three Hypotheses

7.1. Hypothesis 1: The Venetian Plague House

Hypothesis:

The low burial count at Lazzaretto Vecchio reflects a nearly perfect sample of total mortality, a mixture of travelers and Venetian residents, while most epidemic deaths were interred elsewhere. In this scenario, the island functioned primarily as a medical quarantine facility rather than a cemetery of last resort. Deceased travelers may have been repatriated to ships or home ports, and local Venetians may have been returned to parish cemeteries or family tombs. Such practices would have dispersed the epidemic mortality signal across the lagoon rather than concentrating it on the quarantine island.

Predictions:

If this hypothesis were correct, because resident mortality accounts for most of total death toll, then the Lazzaretto Vecchio assemblage should reflect the citywide population structure, including:

High proportions of infants and children reflecting normal household mortality

Frequent presence of kinship clusters representing family burials

Crisis-associated layers or dense burial phases corresponding to epidemic peaks

Pathogen lineages consistent with those circulating in the general Venetian/European population

Test:

To evaluate this hypothesis, demographic (age/sex) profiles, ancient DNA (kinship and pathogen genotype), and radiocarbon/stratigraphic data are compared with parish cemeteries and known crisis burials. If quarantine burials truly represent a random cross-section of Venice’s mortality, we should observe a child-rich demographic, family-linked clusters, and temporally continuous burial activity across plague years.

Status/Interpretation:

Preliminary archaeological evidence contradicts this scenario. Excavations to date reveal predominantly adult burials, low-density interments, and no stratigraphic signatures of catastrophic mass disposal. In parallel, archival directives from the Venetian Republic explicitly required that all individuals who died on Lazzaretto Vecchio be buried on the island and prohibited removal of bodies to ships or parish cemeteries. Accordingly, no official documentation supports the existence of routine off-island reburial or repatriation practices.

However, historical testimony introduces ambiguity. Records describe occasional crisis-driven burial outside the island and rare instances of illicit interment within city cemeteries (5). Thus, while archaeology strongly supports controlled on-island burial, historical narratives leave open the possibility of exceptional emergency actions rather than systematic policy.

7.2. Hypothesis 2A: The Ellis Island Effect

Hypothesis:

A second hypothesis reframes Lazzaretto Vecchio not as a civic burial ground, but as a filtering station for outsiders. In this model, the quarantine island functioned as a premodern “Ellis Island,” where foreign travelers, sailors, and merchants arriving from infected ports were screened, detained, and, if necessary, buried without ever entering the city proper. Venice’s containment strategy thus relied on geographic segregation, using the lagoon as a physical barrier between Venetian citizens and imported contagion. Those interred on Lazzaretto Vecchio were primarily transient individuals caught at the intersection of global trade and local quarantine enforcement.

Predictions:

If this hypothesis is correct, the Lazzaretto Vecchio assemblage should display features of selective, non-resident mortality, including:

A strong adult bias with few or no children, consistent with maritime labor and transient mobility;

Minimal kinship clustering, reflecting isolation of unrelated individuals;

High isotopic diversity (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr and δ¹⁸O) indicating varied geographic origins;

Pathogen lineages representing point-source introductions rather than local, sustained transmission;

Small, discrete burial units accumulated gradually rather than crisis-associated mass pits.

Test:

Evaluation involves integration of demographic, isotopic, and genomic data. Stable isotope analysis will assess non-local origins; aDNA will test kinship and pathogen genotypes for novelty or truncation; and burial spatial modeling will examine whether interments follow slow, regulated accumulation. Evidence for isotopic heterogeneity, adult dominance, and absence of family clusters would support this model of demographic and biological filtration at the maritime frontier.

Status/Interpretation:

Preliminary evidence supports the Ellis Island Effect. Excavated burials show overwhelmingly adult individuals. The paucity of child burials and lack of mass-deposition layers aligns with a model of selective quarantine mortality, in which only those who arrived ill and died during detention were interred. The Lazzaretto thus served not as a site of generalized epidemic death, but as a biological sieve, capturing intercepted infections and preventing community spread within Venice.

7.3. Hypothesis 2B: The Secret Republic Fire

Hypothesis:

A complementary hypothesis to H2A considers not routine quarantine operations, but extreme-event dynamics. During abrupt epidemic surges, representing less than 5% of the island’s operational history, the carefully calibrated traveler-management system may have been rapidly overwhelmed because its underlying logistics were light and designed for low-throughput control. For most decades between major Venetian plague outbreaks, Lazzaretto Vecchio likely received a limited and highly filtered mortality stream, consisting primarily of travelers and isolated suspects dying under regulated conditions, managed by a small, stable staff.

However, during crisis spikes, when mortality exceeded capacity and threatened civic stability, the Republic may have enacted rapid emergency disposal measures outside the official administrative record. The most plausible mechanism is mass burning, conducted discreetly to prevent panic, suppress visible chaos, and protect Venice’s commercial reputation and political authority.

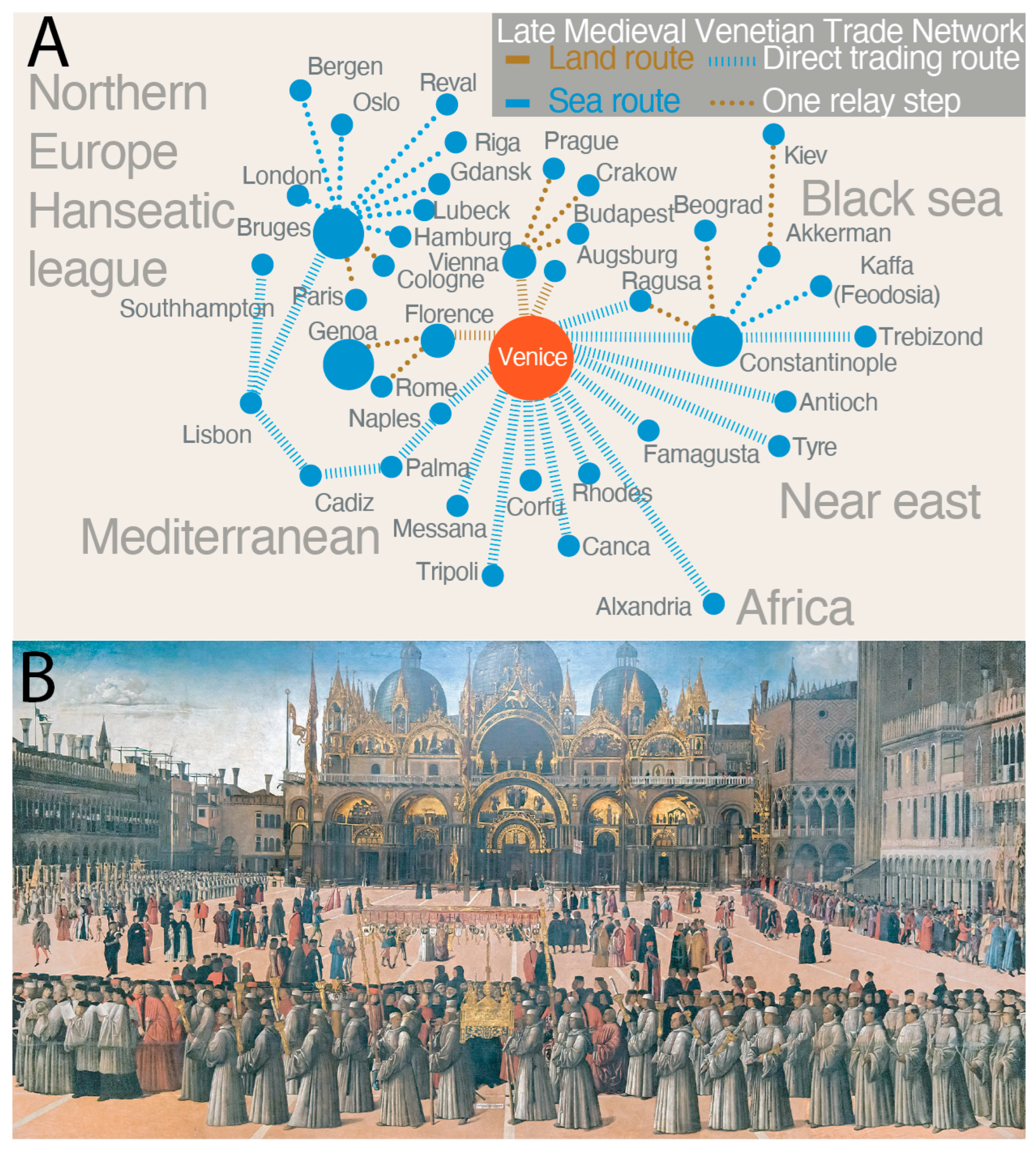

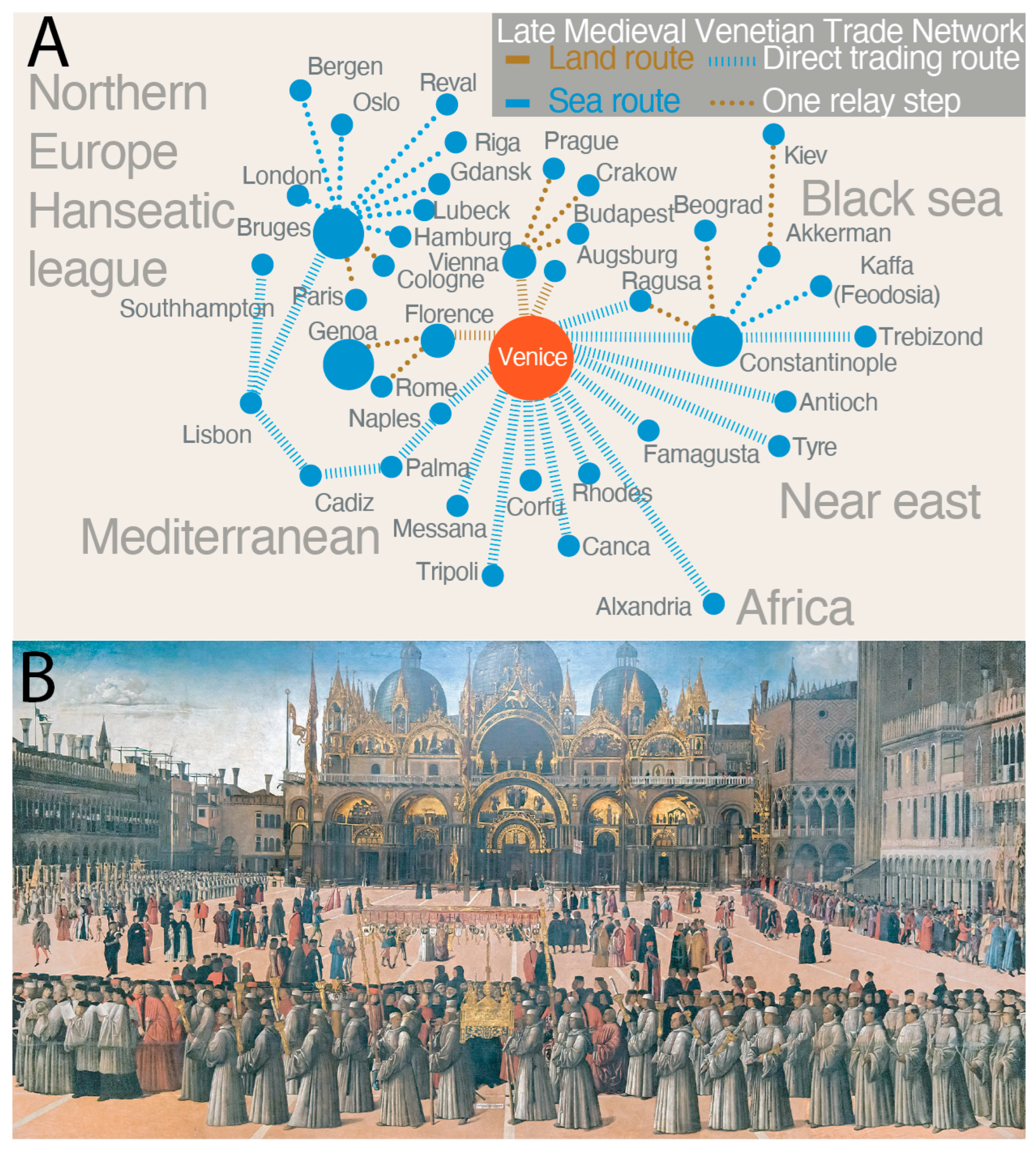

Alternative mass-disposal pathways, such as sea burials or large-scale reburial of plague victims on the mainland, are implausible. Venice’s maritime economy depended on clean, navigable waters for sustaining wide trade networks (

Figure 2A and B), and no records indicate disposal of plague corpses in the Adriatic (

4, 41);. Similarly, transporting large numbers of infected bodies back to the city would have contradicted state policies emphasizing rapid disinfection and containment. Thus, large-scale cremation remains the most plausible mechanism, even though it conflicted with Catholic doctrine, suggesting that such practices were discreet, situational, and left little documentary or material trace.

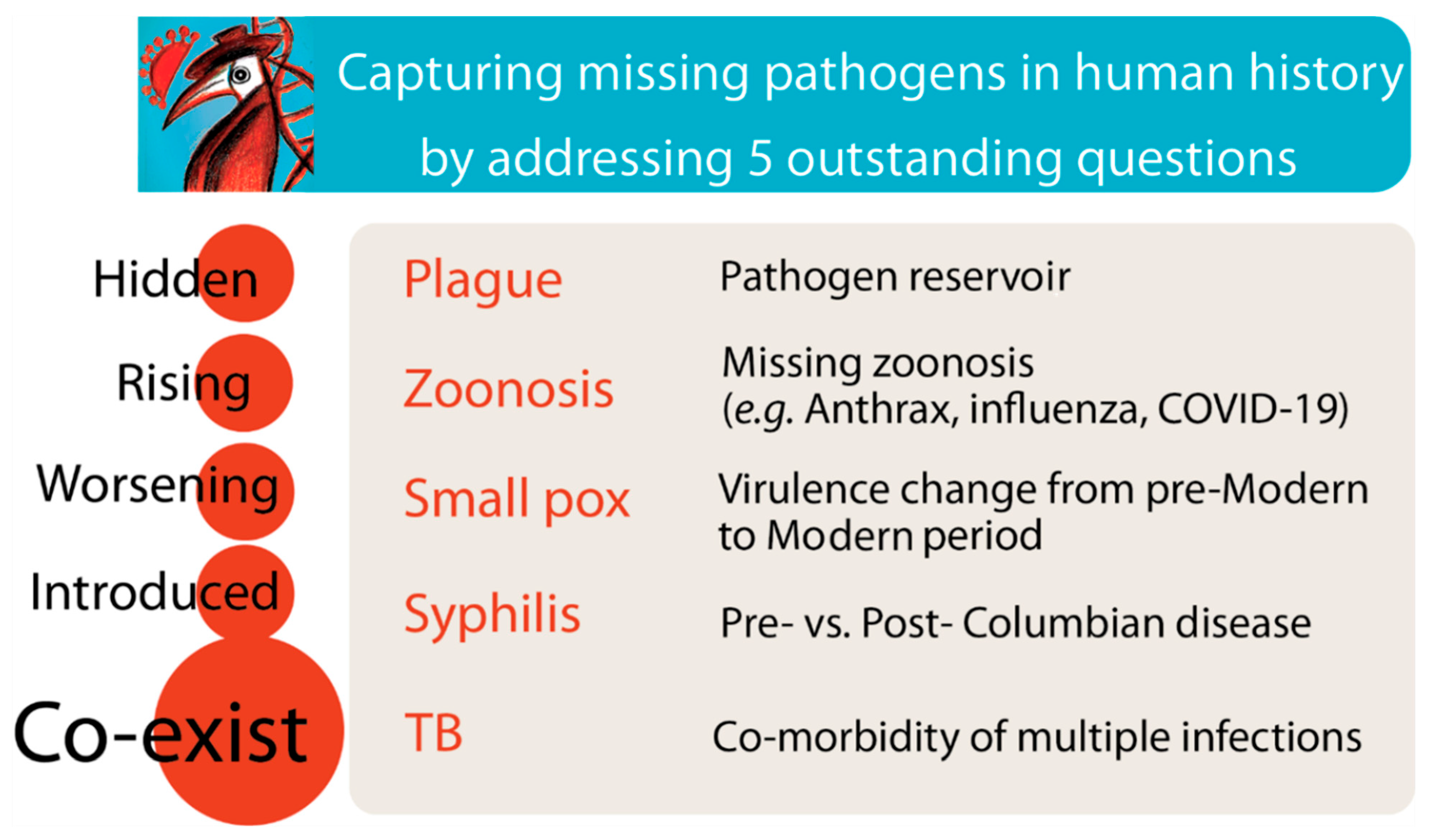

Gentile Bellini (c. 1429–1507), Procession in Piazza San Marco (1496), tempera and oil on canvas, 367 × 745 cm, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice. Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

Predictions:

If this hypothesis is correct, the Lazzaretto Vecchio record should exhibit:

Discontinuities or gaps in radiocarbon-dated burials corresponding to known epidemic peaks;

Absence of mass-burial features despite historically recorded citywide mortality spikes;

Low cumulative burial density relative to documented mortality in major outbreak years.

Test:

High-resolution radiocarbon series, stratigraphic modeling, and pathogen phylogenetic analyses can test this hypothesis. Temporal gaps in burial activity coinciding with archival epidemic years, combined with pathogen lineages showing truncated transmission chains, would support the existence of an emergency bypass system. Comparative analysis of burial tempo and epidemic chronology will determine whether crisis-period mortality was diverted through undocumented rapid-disposal protocols.

Status/Interpretation:

Preliminary evidence is consistent with the Secret Republic Fire model. Excavated areas show small-scale interments across centuries but no crisis-density deposits corresponding to the catastrophic plagues. In this interpretation, what appears as archaeological absence is instead a functional signal of crisis management, evidence that Venice successfully concealed its moments of collapse to maintain stability and the illusion of control.

8. The Most Likely Scenario: A Dual-Regime Time Capsule

H1 (Venetian Plague House), which assumes that burials represent an unbiased sample of total Venetian epidemic deaths, is mutually exclusive with either H2A or H2B. In contrast, H2A (Ellis Island Effect) and H2B (Secret Republic Fire) are not mutually exclusive but complementary, describing distinct operational modes of the quarantine system (

Figure 3):

(1) a routine filtration phase, during which a slow, regulated stream of travelers and maritime laborers died in isolation and were interred under state supervision; and

(2) an emergency crisis phase, during which peak urban mortality was diverted through undocumented, rapid-disposal protocols.

Hypothesis:

We therefore propose a dual-regime containment hypothesis, in which Lazzaretto Vecchio functioned simultaneously as:

a selective entry filter that intercepted infected outsiders (H2A), and

a crisis-bypass node that removed or incinerated resident deaths during major outbreaks (H2B).

Test:

Both H2A and H2B methods.

Predictions:

This composite model predicts that the excavated assemblage represents only baseline, steady-state quarantine mortality rather than the full scale of Venetian epidemic death.

If the dual-regime model is correct, combining the Ellis Island Effect (H2A) and the Secret Republic Fire (H2B), the Lazzaretto Vecchio assemblage should exhibit complementary signatures of both steady-state quarantine mortality and missing crisis deposition:

Persistent low burial density across centuries, producing statistically continuous and long-tailed accumulation curves rather than epidemic-peak clusters.

Adult-skewed demography with few children and minimal kin clustering, consistent with traveler-dominant mortality.

High isotopic heterogeneity (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr and δ¹⁸O) reflecting non-local origins.

Radiocarbon discontinuities corresponding to known epidemic years, indicating crisis-period burial gaps.

Pathogen lineages showing limited branching, extinction, or stalling of transmission chains.

9. Interpretive Framework

Under this model, Lazzaretto Vecchio represents a containment–evolution capsule, a structured epidemiological environment in which infections were intercepted and transmission chains repeatedly terminated. The apparent absence of mass-fatality deposits is interpreted not as a taphonomic loss but as the expected archaeological outcome of a regulated, multi-tier containment system. This dual-regime hypothesis reframes Venice’s quarantine infrastructure as a dynamic institutional immune response in which governance, logistics, and policy jointly influenced the evolutionary trajectories of epidemic pathogens.

10. Capturing the Missing Pathogens from Human History: Five Outstanding Questions

The dual-regime model reframes Lazzaretto Vecchio from a mortuary anomaly into a structured biocontainment archive. Each interment represents not merely an epidemiological endpoint, but a potential biological record of containment, an infection intercepted, a lineage extinguished, and a transmission chain terminated under controlled conditions. From this perspective, the next phase of investigation extends beyond quantifying mortality to recovering and characterizing the pathogens that never reached the Venetian population.

For three centuries, Venice quarantined maritime arrivals on Lazzaretto Vecchio, a controlled frontier zone where travelers, sailors, merchants, and crew from across the Mediterranean and beyond were held under suspicion of contagion. Most who were buried there may not Venetian residents, but transient individuals detained at the threshold of the Republic. They represent a rare demographic: the global infectious-disease reservoir of early modern mobility, concentrated and archived in a single bounded space.

If it is confirmed that the majority of burials are from individuals who were travelers to the Republic, this makes Lazzaretto Vecchio uniquely valuable. Rather than reflecting general civic mortality, the island preserves the biological signal of intercepted infections. They embody a filtered epidemic archive: people who carried pathogens toward Venice but never entered the city, offering a window into the evolutionary “dead ends” of containment.

In this sense, the Lazzaretto archive captures not the catastrophe of uncontrolled plague, but the global microbial traffic of a maritime republic, halted and contained. It functions as a structured repository of the diseases Venice feared most, a centuries-long time capsule of potential outbreaks that were stopped at the border.

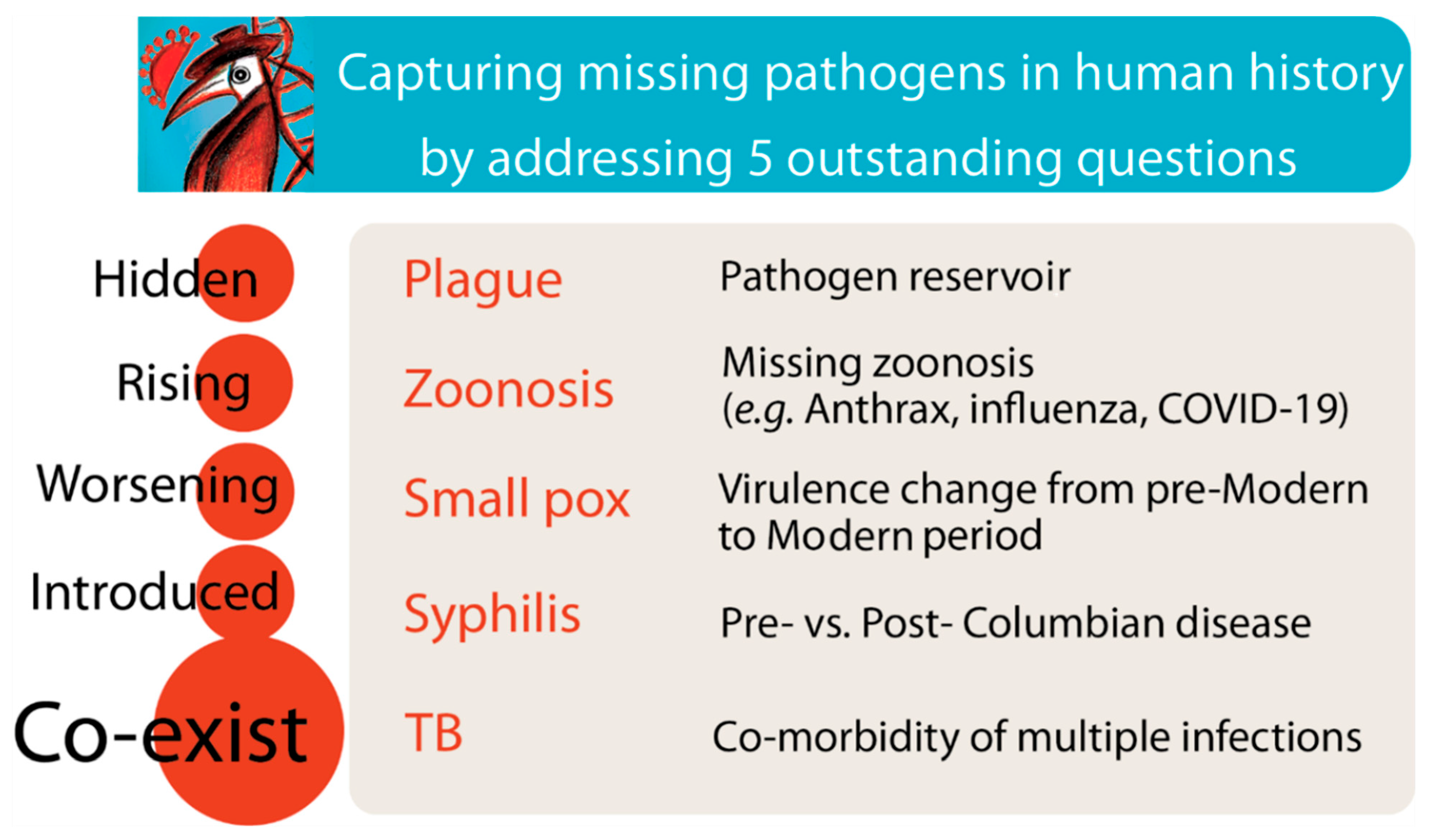

By integrating archival evidence, paleopathology, aDNA, proteomics, isotopes, and pathogen genomics, we use this singular context to pose five fundamental questions (

Figure 4) about the pathogens that shaped human history yet remain largely invisible in traditional archaeological and historical records.

10.1. Question 1. Where Did Epidemic Pathogens Go Between Outbreaks?

Focus: Interruption, Dormancy, and Failed Introductions

Historical plague dynamics(33, 34, 42-44) reveal long intervals of apparent silence between catastrophic waves. Yet the whereabouts, behavior, and evolutionary state of pathogens during these “quiet centuries” remain unclear. Lazzaretto Vecchio contains individuals from across multiple epidemic cycles, including those who died during periods of minimal transmission. This creates a unique opportunity to detect dormant lineages, aborted spillovers, and transmission attempts that failed to seed epidemics, illuminating how pathogens persist, stall, or extinguish between major outbreaks.

10.2. Question 2. How Many Zoonotic Threats Never Reached the City?

Focus: Missed Zoonoses at the Maritime Frontier

Most emerging diseases originate in animals(45-47), yet many historical zoonoses left little or no trace in human records. Because Venice intercepted travelers and cargo arriving from Africa, the Near East, and Eurasia, the Lazzaretto may preserve pathogens that never circulated widely in Europe, rapidly lethal infections, misdiagnosed fevers, or zoonotic agents halted at the maritime border. Genetic analyses can reveal these lost spillovers and unrecorded introductions, illuminating the diversity of zoonotic threats that were contained before they could spread.

10.3. Question 3. What Forces Drive Virulence Shifts in Human Pathogens?

Focus: Evolution Under Containment Pressure

Historical pathogens such as smallpox and plague exhibited marked shifts in virulence (48-53) over time. Did early quarantine systems contribute to these evolutionary trajectories? Venice’s position at the crossroads of global trade, and its sustained experiment in large-scale containment, provides a unique framework to test whether interrupted transmission, recurrent population bottlenecks, and selective barriers shaped the emergence or disappearance of virulent lineages. The Lazzaretto archive offers an opportunity to recover extinct strains and suppressed variants molded by centuries of institutional filtering.

10.4. Question 4. How Did Early Globalization Restructure Pathogen Diversity?

Focus: Disease Traffic Across Empires and Oceans

The post-1492 world fused biological landscapes across continents, transforming the global distribution of infectious diseases (54-60). Venice, linking the Mediterranean with Asia and Africa, functioned as a pre-modern health checkpoint at the interface of empires and trade routes. Individuals buried at Lazzaretto Vecchio span both sides of the time frame of Columbian Exchange, providing an opportunity to compare Old World and newly introduced pathogens, trace lineage replacements, and identify failed microbial migrants that never established in Europe or Asia.

10.5. Question 5. How Often Did Co-infections Shape Mortality?

Focus: Interaction Between Pathogens at the Border

Many infectious deaths arise not from a single pathogen but from synergistic interactions among multiple agents (61-65). Quarantine burials at Lazzaretto Vecchio preserve individuals exposed to diverse disease ecologies spanning continents. Integrating aDNA, proteomics, and paleopathology enables detection of co-infections, synergistic lethality, and underlying immunological vulnerabilities, revealing whether chronic conditions such as tuberculosis acted as silent co-killers alongside acute infections, analogous to modern HIV–TB syndemics (66).

Together, these questions reframe Lazzaretto Vecchio not as a static burial ground, but as a controlled frontier archive of global infectious traffic, a rare longitudinal record of intercepted pathogens, failed epidemics, and containment-shaped evolution. This unique time capsule enables reconstruction of the epidemics that never occurred and the microbial lineages extinguished or redirected by early state quarantine systems.

11. Conclusions and Perspective: Why This Matters Now

In a world reshaped by COVID-19 (67-73) and increasingly threatened by emerging pathogens, Lazzaretto Vecchio speaks directly to the present. It preserves not a record of epidemic collapse, but of deliberate interruption, material evidence that institutional design, logistics, and governance can shape the evolutionary and demographic trajectories of disease.

Lazzaretto Vecchio demonstrates that policy, too, can act as an evolutionary force. Modern biology often frames evolution as a molecular contest between host and pathogen, yet the Venetian system reveals that governance and infrastructure can shape that contest’s outcome. By diverting travelers, isolating the exposed, and separating death from the social body, Venice did more than slow transmission, it altered the ecological conditions under which pathogens evolved. Introductions could stall, transmission chains could break, and outbreaks could flicker out. When those systems were overwhelmed, the state may have shifted to rapid, undocumented disposal, preserving civic order while leaving little archaeological trace. Containment in this context was not only epidemiological, but also logistical, psychological, and evolutionary.

If validated, this dual-regime system, routine filtration punctuated by crisis-response removal, offers a rare historical precedent for modern public health. When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, nations hastily revived measures that Venice had refined centuries earlier: border controls, quarantines, isolation infrastructure, and the physical separation of the sick from the healthy. The enduring challenge remains the same, how to sustain containment without provoking social fracture, panic, or exhaustion. In this light, the “Secret Republic Fire” hypothesis was not a metaphorical flame, but the deliberate burning away of crisis visibility, a strategy to prevent epidemic biology from igniting epidemic fear.

Lazzaretto Vecchio is therefore not merely an archaeological site, but a prototype. It represents an engineered standoff between society and contagion, a centuries-long experiment in reshaping the selective landscape of pathogens. The Venetian public health model advances a radical proposition: that epidemics can be shaped not only by medicine, but by governance; that immune systems are not only biological, but institutional; and that the fate of pathogens is written not only in genomes, but in infrastructure, logistics, and the political will to separate risk from society (Key concepts listed in Box 1).

Containment–evolution capsule

A semi-closed epidemiological environment in which pathogen introductions occur but sustained transmission rarely follows. Repeated interruption of transmission chains imposes strong evolutionary bottlenecks, leading to lineage stalling or extinction. Lazzaretto Vecchio functioned as a real-world containment chamber, an environment where epidemic agents arrived with travelers, encountered institutional barriers, and frequently disappeared without community amplification.

Institutional immune system / biological firewall

The integrated architecture of Venice’s public-health apparatus, including quarantine islands, the Provveditori alla Sanità, surveillance networks, mobility controls, and burial regulations, which collectively acted as an immune barrier at the scale of the state. This system identified external threats, isolated the exposed, and removed risk from the social body. Under acute crisis conditions, it could transition to emergency, often undocumented, disposal practices, analogous to an intensified immune response, to preserve civic stability and prevent social panic.

Epidemic filtration / demographic filter

A quarantine-driven sorting process that selectively concentrated specific categories of the sick while excluding most residents. Lazzaretto Vecchio thus captured the traveler fraction of infection: maritime laborers, migrants, and transient individuals detained prior to city entry. The resulting burial population is characterized by an adult bias, minimal kin clustering, and limited household mortality, demographic features reflecting interception at the boundary rather than community-level collapse.

Hidden-surge bypass (crisis-disposal pathway)

An emergency mode of epidemic management in which large-scale urban mortality was handled rapidly outside the quarantine-burial system, leaving minimal archaeological trace. During severe outbreaks, the Republic appears to have diverted bodies for local or accelerated cremation/burial to maintain order and prevent visible crisis accumulation on the islands. This “bypass” mechanism reconciles the paradox of high recorded mortality with the low depositional signal at the Lazzaretto.

Dormant-lineage echo

Genomic or proteomic traces of pathogens that entered the quarantine system but failed to propagate. These represent evolutionary dead ends, infectious lineages stalled, diluted, or extinguished under demographic isolation and institutional containment. Identifying them reveals suppressed spillovers and aborted transmission events, exposing the hidden evolutionary record of pathogens that reached Venice’s borders but never entered the city.

Venice did not merely endure plague; it designed against it. Lazzaretto Vecchio stands as the genomic and archaeological imprint of a state that tried to break transmission, divert crisis, and interrupt evolution itself. Today, it offers a three-hundred-year molecular archive through which we can reconstruct how policy, environment, and biology coevolved in the making, and unmaking, of epidemic history.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- P. S. Sehdev, The origin of quarantine. Clin Infect Dis 35, 1071-1072 (2002). [CrossRef]

- J. J. Norwich, A History of Venice. (1989).

- K. Konstantinidou, E. Mantadakis, M. E. Falagas, T. Sardi, G. Samonis, Venetian rule and control of plague epidemics on the Ionian Islands during 17th and 18th centuries. Emerg Infect Dis 15, 39-43 (2009). [CrossRef]

- C. B. Vicentini, O. Simonetti, M. Martini, C. Contini, The Italian lazarets of the Adriatic Sea: from their institution to the fight against the economic and demographic collapse caused by epidemics. Infez Med 31, 116-126 (2022). [CrossRef]

- J. L. Stevens Crawshaw, Plague Hospitals: Public Health for the City in Early Modern Venice. (Routledge, London, 2012).

- T.-N.-N. Tran et al., High Throughput, Multiplexed Pathogen Detection Authenticates Plague Waves in Medieval Venice, Italy. PLOS ONE 6, e16735 (2011). [CrossRef]

- G. F. Gensini, M. H. Yacoub, A. A. Conti, The concept of quarantine in history: from plague to SARS. J Infect 49, 257-261 (2004). [CrossRef]

- G. Alfani, Plague in seventeenth-century Europe and the decline of Italy: an epidemiological hypothesis. European Review of Economic History 17, 408-430 (2013). [CrossRef]

- A. L. Moote, London's dreaded visitation: the social geography of the Great Plague in 1665. Med Hist 41, 117-118 (1997). [CrossRef]

- C. Ermus, Memory and the Representation of Public Health Crises: Remembering the Plague of Provence in the Tricentennial. Environ Hist Durh N C, (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Flavel, University of Western Australia, (2023).

- A. Bamji, Marginalia and Mortality in Early Modern Venice. Journal of Social History 52, 532–556 (2019). [CrossRef]

- O. J. Benedictow, The Complete History of the Black Death. (Boydell & Brewer, 2021).

- D. T. Dennis et al., "Plague manual: epidemiology, distribution, surveillance and control," (World Health Organization, 1999).

- M. H. Green, A New Definition of the Black Death: Genetic Findings and Historical Interpretations. De Medio Aevo 11, 139-155 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. H. Green, N. Fancy, Plague history, Mongol history, and the processes of focalisation leading up to the Black Death: a response to Brack et al. Medical History 68, 411-435 (2024). [CrossRef]

- L. Gambaro, "Relazione antropologica preliminare," (Diego Malvestio & C., 2010).

- S. N. Dewitte, Age Patterns of Mortality During the Black Death in London, A.D. 1349-1350. J Archaeol Sci 37, 3394-3400 (2010). [CrossRef]

- M. Signoli, History of the plague of 1720-1722, in Marseille. Presse Med 51, 104138 (2022). [CrossRef]

- R. J. Palmer, University of Kent, (1978).

- V. Archivio di Stato di, Provveditori alla Sanità. Fondo Provveditori e Sopraprovveditori alla Sanità.

- R. Benedetti, Novi Avisi di Venetia. (1577).

- R. Benedetti, D. Calabi, L. Molà, S. Rauch, E. Svalduz, Venezia 1576, la peste: una drammatica cronaca del Cinquecento. (Cierre Edizioni, Sommacampagna (VR), 2021).

- V. Archivio di Stato di, Senato Terra. Fondo Senato.

- E. Rodenwaldt, Pest in Venedig 1575–1577: Ein Beitrag zur Frage der Infektkette bei den Pestepidemien West-Europas. (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1953), pp. 3-263. [CrossRef]

- Redazione, Ex sindaco Vo’Euganeo, non avemmo dubbi sul chiuderci in casa. BlogCQ24, (2025).

- A. P. News. (2020).

- G. Artioli et al., The Chinese identity of St Mark’s bronze ‘Lion’ and its place in the history of medieval Venice. Antiquity 99, 1372-1388 (2025). [CrossRef]

- S. M. Bello, A. Thomann, M. Signoli, O. Dutour, P. Andrews, Age and sex bias in the reconstruction of past population structures. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 129, 24-38 (2006). [CrossRef]

- M. Signoli, I. Séguy, J.-N. Biraben, O. Dutour, Paleodemography and Historical Demography in the Context of an Epidemic: Plague in Provence in the Eighteenth Century. Population (English Edition) 57, 829–854 (2002). [CrossRef]

- S. K. Cohn, Epidemics : hate and compassion from the plague of Athens to AIDS. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, ed. First edition., 2018).

- I. Barbiera, G. Dalla-Zuanna, Demographic Systems of Medieval Italy (6th–15th century AD). Population and Development Review 50, 541-570 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Dutta et al., Ancient Origins and Global Diversity of Plague: Genomic Evidence for Deep Eurasian Reservoirs and Recurrent Emergence. Pathogens 14, (2025). [CrossRef]

- S. R. Adapa et al., Genetic Evidence of Yersinia pestis from the First Pandemic. Genes (Basel) 16, (2025). [CrossRef]

- S. Voerkelius et al., Strontium isotopic signatures of natural mineral waters, the reference to a simple geological map and its potential for authentication of food. Food Chemistry 118, 933-940 (2010). [CrossRef]

- F. Lugli et al., A strontium isoscape of Italy for provenance studies. Chemical Geology 587, 120624 (2022). [CrossRef]

- C. P. Bataille, B. E. Crowley, M. J. Wooller, G. J. Bowen, Advances in global bioavailable strontium isoscapes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 555, 109849 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. C. Vaiani, M. Pennisi, Tracing freshwater provenance in palaeo-lagoons by boron isotopes and relationship with benthic foraminiferal assemblages: A comparison from late Quaternary subsurface successions in Northern and Central Italy. Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana 53, 55-66 (2014).

- R. H. Tykot, Bone Chemistry and Ancient Diet. Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology (2018), pp. 1-11.

- D. Gentilcore, The cistern-system of early modern Venice: technology, politics and culture in a hydraulic society. Water History 13, 375-406 (2021). [CrossRef]

- R. Crowley, City of Fortune: How Venice Ruled the Seas. (2013).

- G. Alfani, T. E. Murphy, Plague and Lethal Epidemics in the Pre-Industrial World. The Journal of Economic History 77, 314-343 (2017). [CrossRef]

- I. A. Khan, Plague: the dreadful visitation occupying the human mind for centuries. T Roy Soc Trop Med H 98, 270-277 (2004). [CrossRef]

- G. Morelli et al., Yersinia pestis genome sequencing identifies patterns of global phylogenetic diversity. Nat Genet 42, 1140-1143 (2010). [CrossRef]

- M. Greger, The human/animal interface: emergence and resurgence of zoonotic infectious diseases. Crit Rev Microbiol 33, 243-299 (2007). [CrossRef]

- B. A. Han, A. M. Kramer, J. M. Drake, Global Patterns of Zoonotic Disease in Mammals. Trends Parasitol 32, 565-577 (2016). [CrossRef]

- H. E. Mableson, A. Okello, K. Picozzi, S. C. Welburn, Neglected zoonotic diseases-the long and winding road to advocacy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8, e2800 (2014). [CrossRef]

- P. Keim et al., The genome and variation of Bacillus anthracis. Mol Aspects Med 30, 397-405 (2009). [CrossRef]

- A. T. Duggan et al., 17(th) Century Variola Virus Reveals the Recent History of Smallpox. Curr Biol 26, 3407-3412 (2016). [CrossRef]

- J. M. Eyler, Smallpox in history: the birth, death, and impact of a dread disease. J Lab Clin Med 142, 216-220 (2003). [CrossRef]

- B. Muhlemann et al., Diverse variola virus (smallpox) strains were widespread in northern Europe in the Viking Age. Science 369, (2020). [CrossRef]

- C. Theves, E. Crubezy, P. Biagini, History of Smallpox and Its Spread in Human Populations. Microbiol Spectr 4, (2016). [CrossRef]

- O. Tomori, From smallpox eradication to the future of global health: innovations, application and lessons for future eradication and control initiatives. Vaccine 29 Suppl 4, D145-148 (2011). [CrossRef]

- A. W. Crosby, P. J. R. McNeill, ProQuest (Firm). (Praeger,, Westport, Conn., 2003), pp. 1 online resource ( 283 pages).

- C. Cumo, ProQuest. (ABC-CLIO,, Santa Barbara, California, 2015), pp. 1 online resource.

- N. Arora et al., Origin of modern syphilis and emergence of a pandemic Treponema pallidum cluster. Nat Microbiol 2, 16245 (2016). [CrossRef]

- J. S. Cummins, Pox and paranoia in renaissance Europe. Hist Today 38, 28-35 (1988).

- K. N. Harper et al., On the origin of the treponematoses: a phylogenetic approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2, e148 (2008). [CrossRef]

- K. Majander et al., Ancient Bacterial Genomes Reveal a High Diversity of Treponema pallidum Strains in Early Modern Europe. Curr Biol 30, 3788-3803 e3710 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Szreter, K. Siena, The pox in Boswell's London: an estimate of the extent of syphilis infection in the metropolis in the 1770s†. The Economic History Review 74, 372-399 (2021).

- J. E. Galagan, Genomic insights into tuberculosis. Nat Rev Genet 15, 307-320 (2014). [CrossRef]

- M. Henneberg, K. Holloway-Kew, T. Lucas, Human major infections: Tuberculosis, treponematoses, leprosy-A paleopathological perspective of their evolution. PLoS One 16, e0243687 (2021). [CrossRef]

- G. Kerner et al., Human ancient DNA analyses reveal the high burden of tuberculosis in Europeans over the last 2,000 years. Am J Hum Genet 108, 517-524 (2021). [CrossRef]

- S. Walaza et al., Excess Mortality Associated with Influenza among Tuberculosis Deaths in South Africa, 1999-2009. PLoS One 10, e0129173 (2015). [CrossRef]

- H. Yang, S. Lu, COVID-19 and Tuberculosis. J Transl Int Med 8, 59-65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- L. C. K. Bell, M. Noursadeghi, Pathogenesis of HIV-1 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis co-infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 80-90 (2018). [CrossRef]

- E. M. Abrams, S. J. Szefler, COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir Med 8, 659-661 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. J. V. Bavel et al., Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav 4, 460-471 (2020). [CrossRef]

- B. Burstrom, W. Tao, Social determinants of health and inequalities in COVID-19. Eur J Public Health 30, 617-618 (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. V. Dorn, R. E. Cooney, M. L. Sabin, COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet 395, 1243-1244 (2020). [CrossRef]

- B. B. Finlay et al., The hygiene hypothesis, the COVID pandemic, and consequences for the human microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, (2021). [CrossRef]

- E. Javelle, D. Raoult, COVID-19 pandemic more than a century after the Spanish flu. Lancet Infect Dis 21, e78 (2021). [CrossRef]

- C. Moreno et al., How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 813-824 (2020). [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Venetian Quarantine Timeline and Early Cartographic Context. A. Timeline of major infectious diseases and key historical events spanning the ~300-year operation of the Venetian quarantine system. Circle size indicates the approximate relative mortality burden of each epidemic. Smallpox represents diseases later eradicated or functionally eliminated through vaccination and modern public health interventions. Blue triangles mark major Venetian plague outbreaks on the timeline. Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; TB, tuberculosis. B. Lazzaretto Vecchio depicted on the 1572 Venetia map by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg (Civitates Orbis Terrarum). Located southeast of the city center, the island is outlined here by a red dashed box, illustrating its established role within Venice’s maritime, quarantine, and public health infrastructure by the 16th century.

Figure 1.

Venetian Quarantine Timeline and Early Cartographic Context. A. Timeline of major infectious diseases and key historical events spanning the ~300-year operation of the Venetian quarantine system. Circle size indicates the approximate relative mortality burden of each epidemic. Smallpox represents diseases later eradicated or functionally eliminated through vaccination and modern public health interventions. Blue triangles mark major Venetian plague outbreaks on the timeline. Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; TB, tuberculosis. B. Lazzaretto Vecchio depicted on the 1572 Venetia map by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg (Civitates Orbis Terrarum). Located southeast of the city center, the island is outlined here by a red dashed box, illustrating its established role within Venice’s maritime, quarantine, and public health infrastructure by the 16th century.

Figure 2.

Venetian Trade Networks and the Routes of Contagion.

A. Reconstructed interaction network of major late-medieval maritime and overland trade centers based on Venetian archival data (adapted from Apellániz 2013 [

18]). Nodes represent ports or commercial hubs, and edges denote documented trading routes and diplomatic contacts, illustrating the extensive mobility corridors linking Venice to Europe, North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean. This network serves as a proxy for historical pathways of pathogen movement and human genetic exchange. It provides a comparative framework for integrating genomic and isotopic data from individuals interred at Lazzaretto Vecchio, enabling alignment of mobility-driven exposure routes with host ancestry, pathogen diversity, and signatures of immune adaptation.

B. Procession in Piazza San Marco (1496) by Gentile Bellini depicts the cosmopolitan character of late-15th-century Venice, featuring Venetians, and diverse other groups active in the city. The scene reflects the demographic heterogeneity that accompanied Venice’s global maritime role and underscores both the city and its quarantine islands as biological and cultural bottlenecks where exposure, immunity, and contagion risk converged.

Figure 2.

Venetian Trade Networks and the Routes of Contagion.

A. Reconstructed interaction network of major late-medieval maritime and overland trade centers based on Venetian archival data (adapted from Apellániz 2013 [

18]). Nodes represent ports or commercial hubs, and edges denote documented trading routes and diplomatic contacts, illustrating the extensive mobility corridors linking Venice to Europe, North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean. This network serves as a proxy for historical pathways of pathogen movement and human genetic exchange. It provides a comparative framework for integrating genomic and isotopic data from individuals interred at Lazzaretto Vecchio, enabling alignment of mobility-driven exposure routes with host ancestry, pathogen diversity, and signatures of immune adaptation.

B. Procession in Piazza San Marco (1496) by Gentile Bellini depicts the cosmopolitan character of late-15th-century Venice, featuring Venetians, and diverse other groups active in the city. The scene reflects the demographic heterogeneity that accompanied Venice’s global maritime role and underscores both the city and its quarantine islands as biological and cultural bottlenecks where exposure, immunity, and contagion risk converged.

Figure 3.

Dual-Regime Mortality Pathways in Venice’s Quarantine System Venice maintained two distinct mortality regimes during epidemic periods, each producing different archaeological and molecular signatures at Lazzaretto Vecchio. Together, these dual pathways explain why the island functions not as a mass-mortality cemetery but as a containment–evolution capsule, preserving terminated transmission events while obscuring peak intra-urban epidemic mortality. The burial record thus reflects interrupted contagion, not the full epidemic burden. Left: Traveler Pathway (“Ellis Island Effect”). Maritime arrivals, including foreign sailors, merchants, pilgrims, and other transient individuals, entered a regulated quarantine pipeline involving inspection, detention, and medical observation. Deaths occurred as a slow, bureaucratically recorded trickle, yielding isolated adult burials with minimal kin clustering on Lazzaretto Vecchio. These standardized, state-managed interments dominate the archaeological record and represent intercepted mortality, not city-wide epidemic collapse. Right: Resident Epidemic Pathway (“Secret Republic Fire”). In contrast, epidemic surges among Venetian residents generated rapid, high-volume mortality managed through decentralized, emergency, and often undocumented disposal across the lagoon. These crisis-response measures left minimal archaeological trace: residents contributed only a small, steady inflow of burials per state infectious-disease policy, despite accounting for the majority of epidemic deaths within the city. Image: Detail of the island of Lazzaretto Vecchio, from Map of Venice (L0064135), Wellcome Collection (2018-03-30), CC-BY-4.0.

Figure 3.

Dual-Regime Mortality Pathways in Venice’s Quarantine System Venice maintained two distinct mortality regimes during epidemic periods, each producing different archaeological and molecular signatures at Lazzaretto Vecchio. Together, these dual pathways explain why the island functions not as a mass-mortality cemetery but as a containment–evolution capsule, preserving terminated transmission events while obscuring peak intra-urban epidemic mortality. The burial record thus reflects interrupted contagion, not the full epidemic burden. Left: Traveler Pathway (“Ellis Island Effect”). Maritime arrivals, including foreign sailors, merchants, pilgrims, and other transient individuals, entered a regulated quarantine pipeline involving inspection, detention, and medical observation. Deaths occurred as a slow, bureaucratically recorded trickle, yielding isolated adult burials with minimal kin clustering on Lazzaretto Vecchio. These standardized, state-managed interments dominate the archaeological record and represent intercepted mortality, not city-wide epidemic collapse. Right: Resident Epidemic Pathway (“Secret Republic Fire”). In contrast, epidemic surges among Venetian residents generated rapid, high-volume mortality managed through decentralized, emergency, and often undocumented disposal across the lagoon. These crisis-response measures left minimal archaeological trace: residents contributed only a small, steady inflow of burials per state infectious-disease policy, despite accounting for the majority of epidemic deaths within the city. Image: Detail of the island of Lazzaretto Vecchio, from Map of Venice (L0064135), Wellcome Collection (2018-03-30), CC-BY-4.0.

Figure 4.

Five Key Questions for Recovering Missing Pathogens from Human History. This conceptual framework highlights five outstanding questions in historical infectious-disease research that the study of Lazzaretto Vecchio is uniquely positioned to address. Representative pathogen examples are shown in red. Together, these questions define a roadmap for reconstructing the “shadow” history of infections suppressed or extinguished by early containment systems: 1. Hidden Disease Reservoirs: Where did pathogens such as Yersinia pestis persist between major outbreaks, and how did they re-emerge after long dormancy? 2. Undetected Zoonoses: Which animal-to-human infections, including anthrax and other rapidly fatal diseases, were intercepted at the quarantine frontier but never reached epidemic scale? 3. Virulence Shifts: How did containment, interrupted transmission, and selective bottlenecks influence transitions from mild to hyper-virulent forms, as seen in smallpox? 4. Pathogen Introductions: How can genomic data disentangle pre- and post-Columbian lineages, for example in treponemal disease (syphilis)? 5. Co-Infection Dynamics: To what extent did multi-pathogen comorbidity, particularly with chronic infections such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, shape mortality and immune vulnerability?. Answering these questions requires an integrated analytical framework combining paleogenomics, proteomics, paleopathology, isotopic mobility data, and archaeological context, using the Venetian quarantine system as a uniquely time-structured containment archive for testing how policy, biology, and evolution intersected across centuries.

Figure 4.

Five Key Questions for Recovering Missing Pathogens from Human History. This conceptual framework highlights five outstanding questions in historical infectious-disease research that the study of Lazzaretto Vecchio is uniquely positioned to address. Representative pathogen examples are shown in red. Together, these questions define a roadmap for reconstructing the “shadow” history of infections suppressed or extinguished by early containment systems: 1. Hidden Disease Reservoirs: Where did pathogens such as Yersinia pestis persist between major outbreaks, and how did they re-emerge after long dormancy? 2. Undetected Zoonoses: Which animal-to-human infections, including anthrax and other rapidly fatal diseases, were intercepted at the quarantine frontier but never reached epidemic scale? 3. Virulence Shifts: How did containment, interrupted transmission, and selective bottlenecks influence transitions from mild to hyper-virulent forms, as seen in smallpox? 4. Pathogen Introductions: How can genomic data disentangle pre- and post-Columbian lineages, for example in treponemal disease (syphilis)? 5. Co-Infection Dynamics: To what extent did multi-pathogen comorbidity, particularly with chronic infections such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, shape mortality and immune vulnerability?. Answering these questions requires an integrated analytical framework combining paleogenomics, proteomics, paleopathology, isotopic mobility data, and archaeological context, using the Venetian quarantine system as a uniquely time-structured containment archive for testing how policy, biology, and evolution intersected across centuries.

Table 1.

Summary of competing hypotheses and testable predictions for the Lazzaretto Vecchio system.

Table 1.

Summary of competing hypotheses and testable predictions for the Lazzaretto Vecchio system.

| Hypothesis |

Predicted Archaeological & Molecular Evidence |

Analytical Approaches |

Interpretive Implication |

|

H1. Venetian Plague House: A perfect subset of total death of both travelers and residents

|

• High burial density • Age distribution mirrors Venice population (including infants/children) • Kinship clusters reflecting household burial• Pathogen lineages consistent with city-wide epidemic strains |

• Osteodemography (indicator for age/sex profiles) • aDNA for kinship and pathogen genotypes ….. • Spatial mapping of burial density ….. • Radiocarbon stratigraphy |

Lazzaretto Vecchio reflects city-wide epidemic mortality; low burial counts result from incomplete excavation or taphonomic loss. |

|

H2A. Ellis Island Effect: Selective Quarantine Filter of Travelers

|

• Predominantly unaccompanied adults • Very few children or family units • High isotopic diversity (non-local origins) • Low kinship clustering • Pathogen signals representing arrival or early-transmission stages |

• 87Sr/86Sr and δ¹⁸O isotopes (indicator for mobility and provenance)• aDNA ( indicator for ancestry, kinship)• Pathogen genomics (for identification of strain novelty) • Burial-pattern analysis ….. |

The island functioned as a biological immigration filter, recording imported disease risk rather than Venetian mortality. |

|

H2B. Secret Republic Fire: Undocumented Crisis Disposal During Outbreaks

|

• Small, orderly burial groups during non-crisis periods • Broad chronological range, low baseline deposition rate • Absence of large epidemic layers during plague peaks • Temporal gaps in deposition • Pathogen signals of brief introductions without sustained spread |

• High-resolution radiocarbon series …..• Stratigraphic and temporal cluster analysis ….. • Pathogen phylogenetics to detect truncated transmission chains • Spatial-use modeling ….. |

Routine quarantine burials preserved; surge mortality erased through emergency cremation. Archaeology reflects steady-state function rather than crisis peaks. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).