1. Introduction

The layout of urban street networks constitutes the basic structure of cities, acting as conduits of movement, resources, and socio-economic exchanges [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. As dynamic arteries, streets incorporate diverse urban elements—residents, commerce, and services—into a cohesive spatial system, profoundly influencing economic vitality and socio-cultural identity [

6,

7]. In this paper, the term “street store” refers to retail store or service establishment, that have entrances on the ground level floors facing the streets. They serve as nodes in this system, embodying the interplay of spatial structure with urban life [

7,

8,

9]. Although there have been macro-scale studies that establish the relationship between street network topology and retail distribution [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], analyses at the meso- and micro-scales of store spatial configurations, particularly in terms of their economic and socio-cultural roles, remain underexplored, especially in rapidly urbanizing regions like China [

20,

21].

The dual network logic of Space Syntax is a promising lens to explore the above issues. It delineates two distinct structures: the foreground network has long connected lines which underpin micro-economy, and the background network has short and clustered lines representing the embedding of socio-culture life [

22]. Based on natural movement theory, this binary posits that spatial integration correlates with pedestrian flows and economic or cultural opportunities [

23]. Although Space Syntax has been widely applied in studies of urban morphology and traffic planning [

24,

25], it has been seldom employed to examine stores distribution at finer scales, limiting its capacity to illuminate how spatial structure mediates urban processes.

In China’s rapidly urbanizing context, street stores constitute both commercial resilience and cultural continuity, but their spatial configuration coherence are usually neglected in current planning [

26,

27,

28]. The post-COVID-19 era amplifies this urgency, as cities strive to revive micro-economies and social fabrics damaged by the pandemic [

29]. Existing research predominantly focuses on macro-scale determinants of store location, such as street centrality, urban nodes, or built environment attributes [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

17,

30], with limited attention to how spatial variations at meso- and micro-scales shape store characteristics [

31,

32]. For example, studies emphasize the street integration’s role in attracting commercial activity [

20,

33], but few explore how these patterns vary with network types or reflect broader urban dynamics. This limitation is acute in Chinese cities, where organic historical cores coexist with planned expansions, offering a rich context to test spatial theories [

34].

This study responds to the limited attention by using the dual network logic of Space Syntax to investigate the spatial configuration of street stores on eight segments in four Chinese cities: Tianjin, Nanjing, Zhengzhou, and Hong Kong. Chosen for their socio-economic vibrancy and morphological diversity, these cities encapsulate China’s urban evolution—from organic grids to geometric layouts. With 2019 Point of Interest (POI) data, street view imagery, and field surveys, we compare store operation methods, functional diversity, and 100-meter density between high-value foreground and background network segments. Topological analysis distinguishes these networks, and tests two hypotheses: 1) foreground networks prefer economically-driven stores; and 2) background networks support dense, socio-culturally embedded stores.

Our approach represents a double contribution on Space Syntax theory. First, it applies the dual network framework beyond macro-scale urban form to meso- and micro-scales store patterns and shows how spatial structure externalizes economic and socio-cultural forces [

35,

36]. Second, it combines quantitative spatial metrics with store-level data, offering a replicable urban analytics framework. Practically, our findings address China’s commercial planning deficits [

26] and provide implications to optimize store distributions for economic vitality and cultural identity—critical in the post-pandemic recovery context. By linking meso- and micro-scales spatial patterns to broader urban processes, this study enhances our understanding of cities as complex adaptive systems.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews dual network of Space Syntax, and the relationship between street and store spatial configuration;

Section 3 discusses research method, including network identification and data analysis;

Section 4 presents focus on comparative outcomes;

Section 5 discusses theoretical and practical implications; and

Section 6 concludes and points out future research issues.

2. Research Principles

2.1. Theoretical Basis: Dual Network Logic of Space Syntax

Space syntax provides a widely adopted analytical format for the study of urban space. It can structurally extract the “spatial characteristics” of cities and help us understand the interactions between activity and space [

37].

Based on natural movement theory, which suggests that the spatial configuration of streets shapes movement flows and patterns of economic activity, Hillier noted that the urban street network is composed of two inseparable linear structures, “the foreground network” and the “background network”. Cities in different regions around the world, whether organic or artificial, all exhibit structural consistency. That is, they are composed of a foreground network that links city centers of all scales and a background network that is mostly located in residential areas. “The foreground network is made up of a relatively small number of longer lines, connected at their ends by open angles, and forming a super-ordinate structure within which we find the background network, made up of much larger numbers of shorter lines, which tend to intersect each other and be connected at their ends by near right angles, and form local grid like clusters.” The formation of the dual network is the imprint of economic and socio-cultural forces on the city. The foreground network maximizes the urban gridding and drives the urban micro-economy; the background network hinders the structural movement of the city because of its specific cultural characteristics, and makes the city look different. The dual network structure reflects how micro-economic forces and socio-cultural forces employ the same underlying spatial and spatio-functional laws to achieve distinct effects. And in the past, urban research models have often failed to comprehensively integrate the complex interactions between spatial, economic, social, and cultural dimensions [

35].

At present, research related to dual networks has focused mainly on the significance of the binary structure of the street network at the city level. For example, the Normalised Angular Choice (NACH) and Normalised Angular Integration (NAIN) values are used to interpret and optimize urban traffic [

24,

25], and studies discussing urban form change are from the dual network perspective [

34]. However, studies at the mesoscopic and microscopic levels are rare.

2.2. Research Perspective: The Relationship Between Street and Store Spatial Configuration Under the Dual Network Logic

The dual network logic of Space Syntax implies that the foreground network and the background network have different impacts on land use and building space along the street, which is valuable for understanding the spatial configuration of street stores. Hillier posited that there is a causal relationship among space, movement, and economic activities. The greater the integration of the street is, the greater the flow of people, and the more attractive the land along the street to economic activities [

10,

38]. Over the years, many relevant studies have confirmed that indicators, such as the street integration and connectivity, are associated with urban commercial activities [

20,

30,

33,

36,

37,

39,

40], and the spatial configuration of the street network affects the location distribution of stores as activity attraction points [

39,

41]. The binary structure of the street network determines the relative differences in the urban movement modes driven by the foreground network and background network; therefore, the needs and opportunities of urban life also differ. It can also be understood that the different effects of the urban economy and socio-culture on land use and building space along streets determine the differences in the spatial configuration of street stores on streetsides [

42,

43,

44,

45]. The dual network logic of Space Syntax provides an interesting and different perspective for the study of spatial configuration of street stores.

3. Methods

This study applies Space Syntax’s dual network logic to examine the spatial configuration of street stores in eight street segments of four Chinese cities by combining topological analysis with empirical store data. The approach has three steps: 1) identification of the street network, 2) selection of street segment and collection of data, and 3) comparative analysis of store configurations. Each step is described in the following, with examples to ensure transparency and replicability.

Data of the street stores are collected mainly from point of interest (POI) data and street view images combined with field survey. To remove the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on street stores, we use the data of 2019, as a large number of street businesses closed after 2020 and post-pandemic short-term data no longer reflects normal commercial patterns.

3.1. Street Network Identification

Street networks of Tianjin, Nanjing, Zhengzhou, and Hong Kong were modelled using 2019 geospatial data from Baidu Maps, Google Maps, and OpenStreetMap (OSM). Data consistency was ensured by cross-validating alignments, resolving discrepancies. Networks were digitized as axial maps—linear representing streets—and processed in DepthMapX for Space Syntax analysis.

Background and foreground street networks were distinguished using Normalised Angular Choice (NACH) and patchwork pattern analysis (

Figure 1). NACH, which measures street selectivity in the context of global spatial depth, was used to identify foreground networks with high traffic potential. This measure effectively reveals the internal structure of urban morphology and facilitates comparative analysis of street network configurations at different cities or different parts of the same city [

23]. Hillier and Yang noted that the 1.4 maps of NACH are comparable, which should contribute to the further comprehension of the relationship between different cities in terms of local organization and global structure [

22]. The NACH value is calculated using the following formula:

Choice (CH) represents the potential for through-movement within the spatial system. Total Angular Depth (TD) is defined as the cumulative sum of the shortest angular path depths from a given segment to all other segments in the system.

The patchwork pattern represents the metric distance in the urban structure and can be used to identify the background network. It captures local spatial features and effectively identifies pedestrian-friendly areas within a defined radius [

23]. A 1000 m radius is used to calculation of the metric distance mean depth (MD), with the color scale adjusted to reveal the patchwork mode [

23].

Total Angular Depth (TD) represents the cumulative sum of the shortest angular paths from a given segment to all other segments. Node Count (NC) denotes the total number of segments traversed when connecting the current segment to all others.

3.2. Sample Selection and Data Collection

Street stores were sampled from eight typical street segments of four typical cities for comparative analysis: four segments are the high-valued segments in the foreground network and four in the background network. The selection followed three criteria: 1) the micro-economic and socio-cultural environment should be stable and old urban area preferred; 2) typicality within network types, excluding specialized urban areas with special significance, such as CBDs and historic districts; and 3) spatial proximity between foreground and background segments within the same city to control for population and consumption-related factors. The demographic factors influencing consumption include population size, demographic composition, income level, and consumption habits [

46]. The selected segments are:

The selected high-value street segments of the foreground networks include: Kunwei Road in Tianjin (the segment from Zhongshan Road to Jinzhonghe Street), South Zhongshan Road in Nanjing (the segment from the East Zhongshan Road to Jianye Road), Longhai Road in Zhengzhou (the segment from Huashan Road to Tongbai South Road), and Kwun Tong Road on Hong Kong (the segment from Chong Yip Street to Tseung Kwan O Road). Corresponding high-value segments of the background networks are: Luwei Road in Tianjin (the segment from Wuma Road to Zhongshan Road), Chaotiangong West Street in Nanjing (the segment from Luolang Road to Mochou Road), Guomianchang Street in Zhengzhou (the segment from Mianfang West Road to Jianshe West Road), and Ngau Tau Kok Street in Hong Kong (the segment from the Kung Lok Road to Hong Ning Road) (

Figure 2).

Store data, collected for 2019 to avoid COVID-19 disruptions, integrated three sources: (1) Baidu Maps POI data; (2) street view imagery verifying storefronts; and (3) 2019 field surveys refining operational status. Stores were geocoded, excluding upper-floor businesses without street-facing entrances. Effective lengths (L) were measured, omitting non-commercial zones.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Spatial Configuration of Street Stores

Three metrics quantified store configurations: operation methods, functional diversity, and 100-meter density.

3.3.1. Operation Methods

Stores were classified as sole or chain based on POI and survey data. Sole store is the business operation model that relies on individual or small-scale operators to independently handle the management, investments and personnel organization. Operators make business decisions according to their own wishes and control the management characteristics and development orientation. Sole stores can extensively infiltrate into various consumption localities and flexibly meet the needs of consumers [

47] and are personalized and flexible. Chain stores are a management and organizational form in which a number of stores sell similar products or services to achieve economies of scale through standardized operation under unified guidance. Chain stores are characterized by standardized images and approximations of products and services.

The proportions of different operation methods were computed and compared between the high-value street segments of the foreground and background networks. Proportions assessed the degree of economic standardization versus local adaptability.

3.3.2. Functional Diversity

Stores were grouped into nine categories (

Table 1)—prepared food, commodity sales, accommodation, financial, living, car, recreation, education, and medical—tailored to Chinese contexts [

48].

The Shannon-Wiener index measured diversity [

49,

50]:

where H represents the Shannon-Wiener diversity index, pi represents the relative richness of the store category, Σ represents the sum of all store categories, and ln represents the natural logarithm.

3.3.3. 100-Meter Density

100-m density of street stores refers to the average number of stores within an effective length of 100 m along a street, defined as the continuous length of store-accessible frontage excluding road intersections, neighborhood entrances and exits, construction sites, and other areas where commercial use is restricted by urban regulations. A 100-m density reflects the distribution density of stores on the street, and the corresponding formula is as follows:

where D is the 100-m density of stores, Q is the total number of stores in the street segment, and L is the effective length of the selected street segment.

Differences were tested using independent samples t-tests (α=0.05) in SPSS. Normality was verified via Shapiro-Wilk tests; Mann-Whitney U test adjusted for unequal variances where needed.

4. Results

In this section, we show results of comparative analysis of street store configurations across eight segments of the foreground and background networks in four Chinese cities. Results are presented in three subsections: operation methods, functional diversity, and 100-meter density. Each metric is quantified, statistically tested, and visualized to reveal systematic differences in the spatial configuration of street stores under the dual network logic of space syntax.

4.1. Operation Methods

Store operation methods—sole versus chain—were assessed to evaluate economic standardization versus local adaptability.

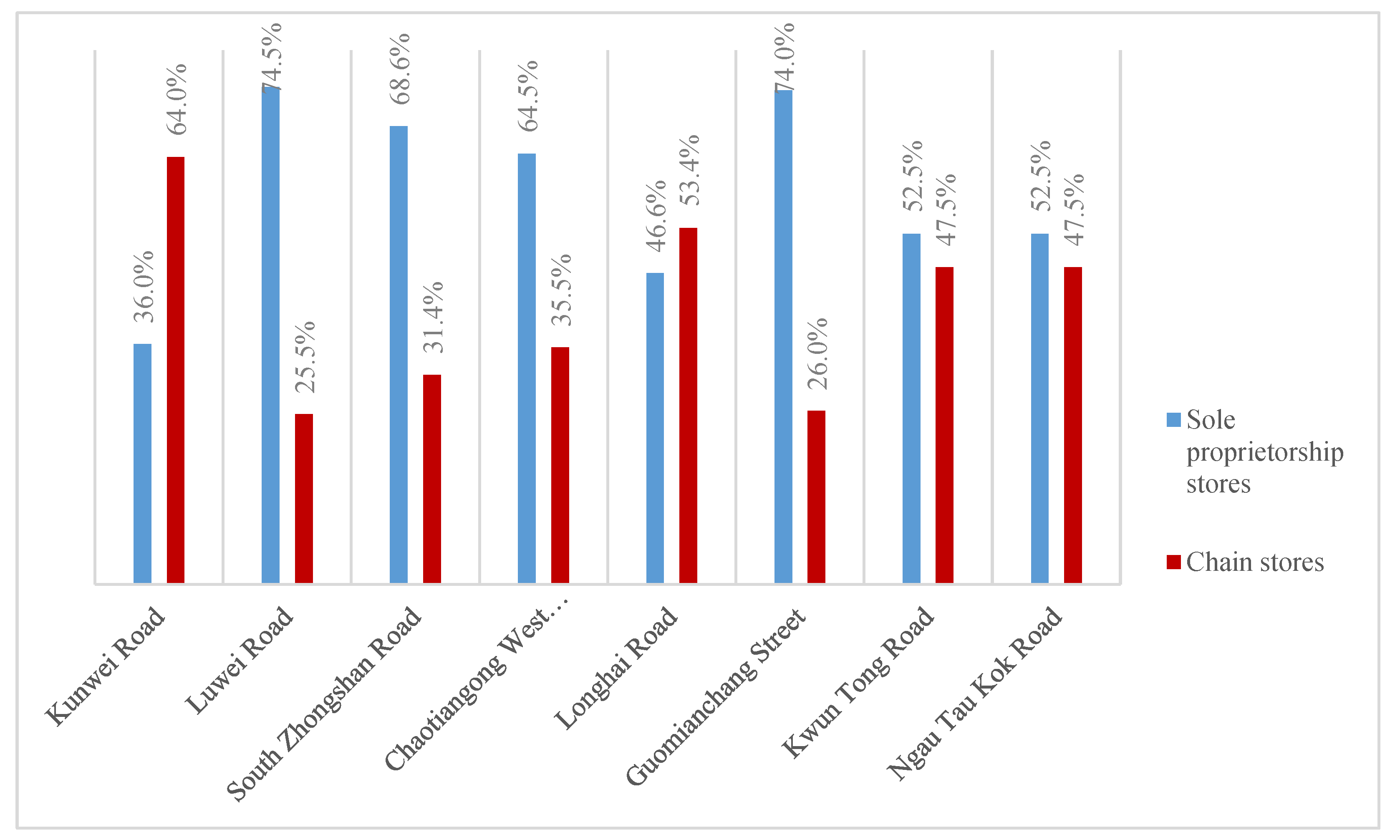

In all cities, the proportion of sole stores in the high-value street segments of the background network is greater than that of chain stores, and the difference is obvious in Luwei Road in Tianjin and Guomianchang Street in Zhengzhou, but the smallest difference in Ngau Tau Kok Road in Hong Kong. A paired t-test showed that the proportion of sole stores on high-value street segments of the background network was relatively greater than that of chain stores (M = 33.62%, SD = 10.33%). There was a marginal difference, t (3) = 3.17, p (two-tailed) = 0.05. This result suggests a potential trend toward a higher prevalence of sole stores, indicating stronger socio-cultural embeddedness in the background network.

Between cities, the distribution of chain stores does not show significant differences between foreground and background networks. Howevwer, in the same city, the proportion of chain stores in the high-value street segments of the foreground network is greater than or close to that of the background network (

Table 2,

Figure 3, and

Figure 4).

The above phenomenon demonstrates that chain stores are less sensitive to foreground and background networks than sole stores, suggesting a lower dependence on street network classification. This is largely attributed to consumer loyalty to the brand, which significantly influences the consumption pattern of chain stores [

51,

52].

4.2. Functional Diversity

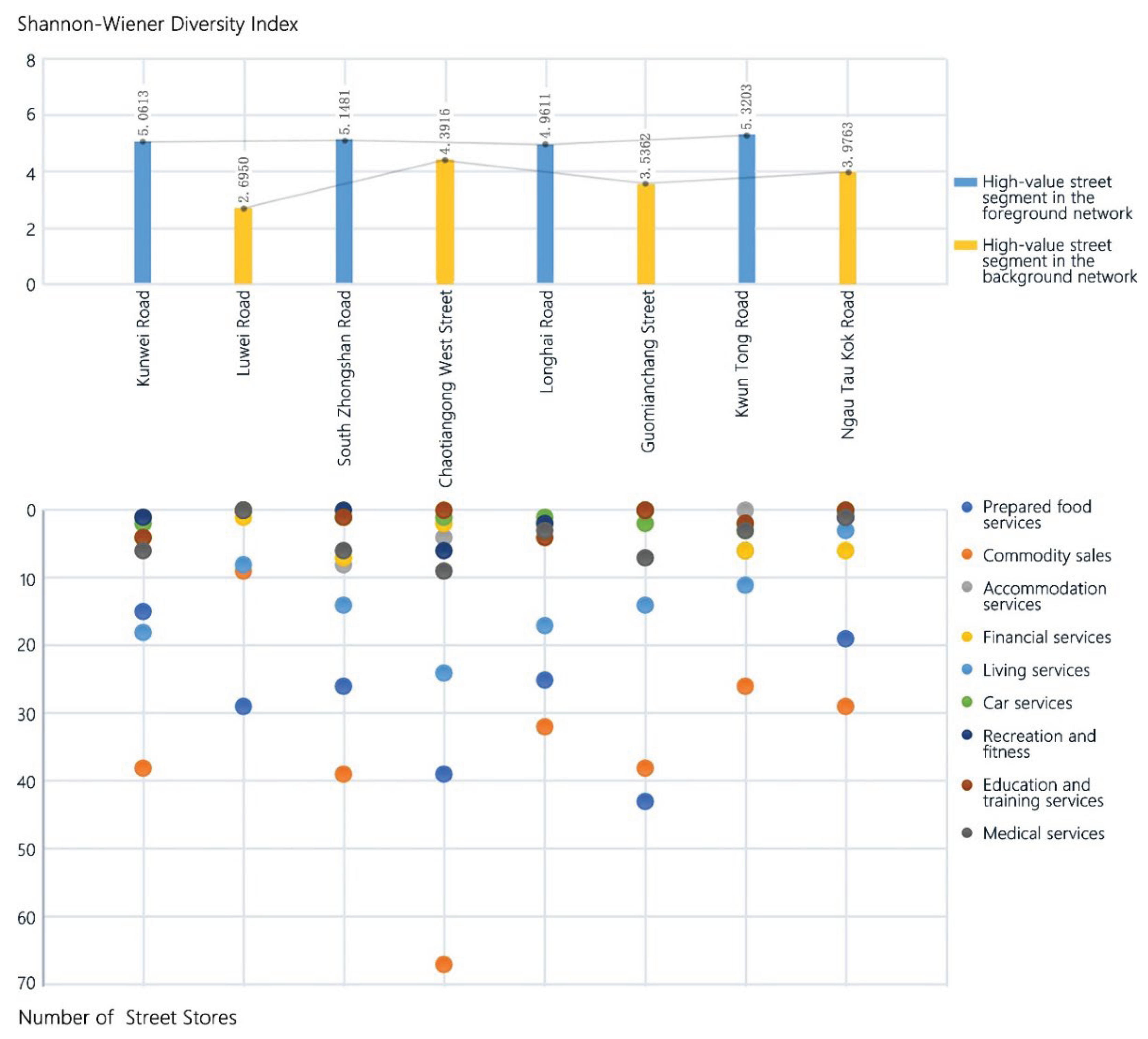

The Shannon-Wiener indices were calculated to assess the richness and evenness of store categories. Stores in high-value street segments of the foreground networks consistently showed higher diversity than those of background networks (

Table 3).

The functional diversity of the high-value street segments of the foreground networks was significantly higher than that of the background networks (

Figure 5). Across the four high-value street segments of the foreground networks, the Shannon diversity index values were similar, with a mean H of 5.12 and slight fluctuation (SD = 0.15). The mean H value of high-value street segments of the background networks was 3.65, with considerable variation (SD = 0.74).

Category distributions underscored these trends. The high-value street segments of the foreground networks nearly covered all nine types, whereas those in the background networks were heavily skewed toward daily needs.

4.3. 100-Meter Density

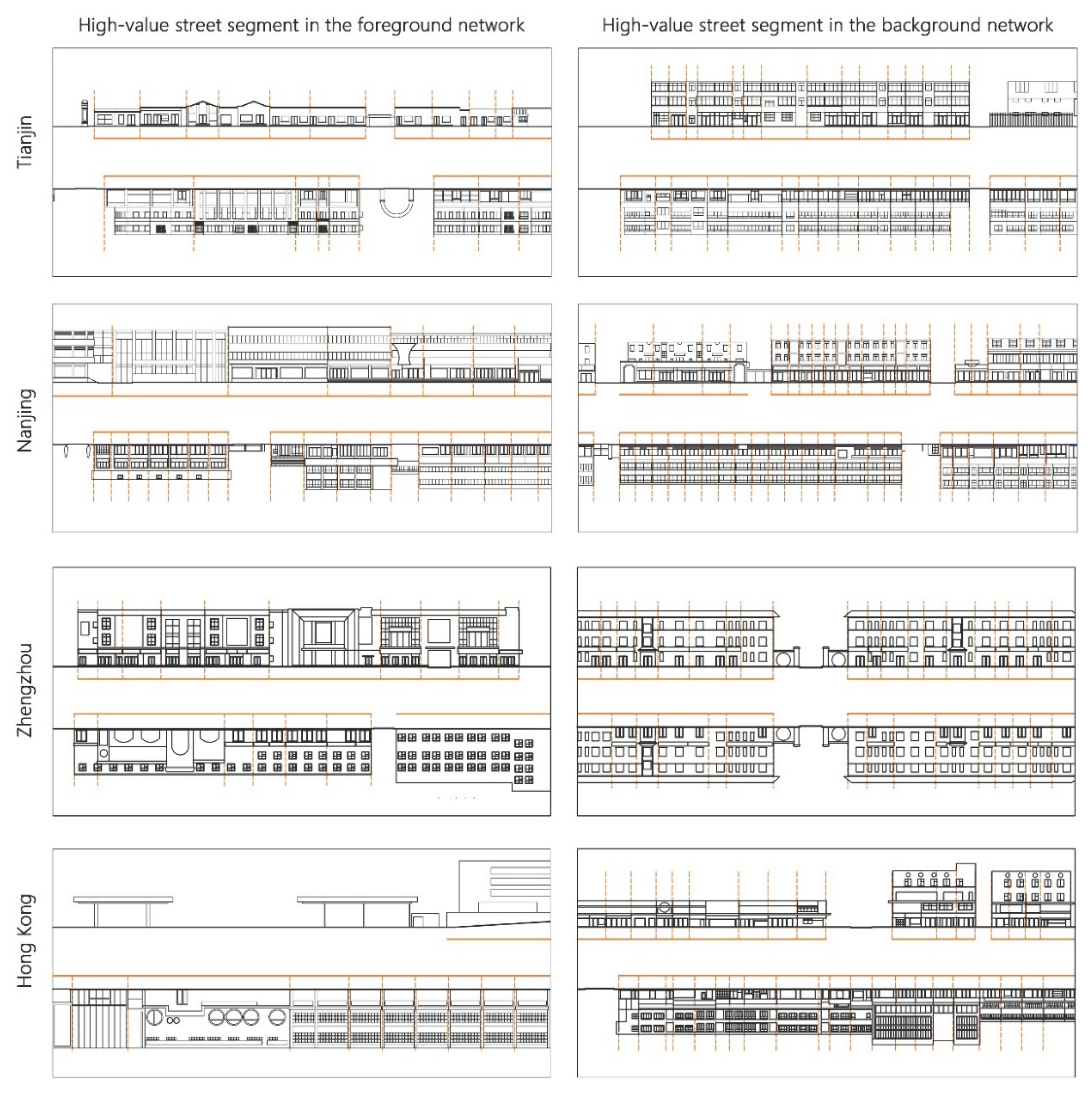

Store density is consistently higher in the high-value street segments of background networks than those of foreground networks (

Table 4).

The average store density in the high-value street segments of the foreground networks was 5.92 stores per 100 meters (SD = 1.53): Kunwei Road in Tianjin (8.01), Zhongshan Road in Nanjing (5.05), Longhai Road in Zhengzhou (6.29), and Kwun Tong Road in Hong Kong (4.32). In contrast, the average store density in the high-value street segments of the background networks was 15.35 stores per 100 meters (SD = 2.50), with the highest density on Guomianchang Street in Zhengzhou (16.92), followed by Chaotiangong West Street in Nanjing (16.78), Ngau Tau Kok Road in Hong Kong (16.40), and Luwei Road in Tianjin (11.25). An independent samples t-test showed that the store density in background high-value segments was significantly higher than that of the foreground network (t (6) = -5.93, p = 0.001), with a mean approximately 2.6 times greater.

The comparison of storefront widths further reinforced this pattern. high-value street segments of the foreground networks featured a mix of narrow (4–6 meters) and wide (>10 meters) shops, whereas those in the background networks tended to consist of uniformly narrow storefronts (

Figure 6).

5. Discussion

This study explains how Space Syntax’s dual network logic—foreground and background networks—shapes the spatial configuration of street stores in Chinese cities, revealing the different economic and socio-cultural imprints at the meso- and micro-scales. By analyzing operation methods, functional diversity, and 100-meter density for eight segments, Hillier’s framework is tested and developed, and contributes to new insights into urban spatial dynamics [

35]. The following section interprets these findings, places them in the existing literature, and discusses their implications.

5.1. Operation Methods: Influences of Micro-Economy and Socio-Culture

High-value street segments of foreground network are more favored by chain stores, and those of the background network are predominantly occupied by sole stores. This is consistent with Hillier’s argument that the high-value street segments of the foreground networks, with higher integration, attract standardized economic activities by leveraging scale and connectivity [

41]. Chain stores, reflecting broader consumer loyalty [

53], exploit these conditions to maximize efficiency. In contrast, the high-value street segments of the background networks, with lower NACH values, help create localized and adaptive sole stores, supporting Zheng’s argument that sole stores possess greater flexibility in meeting local demands [

47].

This dichotomy questions such macro-scale studies that overlook network-specific effects, and highlights that micro-economic forces and socio-cultural ties differentially shape store operations [

14]. However, Hong Kong shows a more balanced distribution, with sole stores comprising 52.5% in both networks. This suggests a context-dependent pattern, possibly shaped by the city’s compact and high-density urban morphology [

31], which warrants further exploration.

5.2. Functional Diversity: The Tension between Universal Supply and Local Demand

The high-value street segments of foreground network have more functional diversity than those of background network, with a statistically significant difference. This is aligned with the theory of natural movement [

39] that indicates that high-value segments of foreground network are highly integrated streets that attract diverse activities and host a balanced distribution of various types of stores to meet general urban needs. On the other hand, high-value street segments of background network are more related to daily activities, reflecting socio-cultural characteristics rather than economic spread.

The findings corroborate those of Scoppa and Peponis, linking street connectivity to commercial variety, but further relating diversity to network type [

33]. The lower diversity in background networks contrasts with Western studies [

6], where residential areas tend to have mixed-of-uses, and supports the notion that China’s urban grids prioritize localized functionality [

34], a pattern accentuated by rapid urbanization.

5.3. 100-Meter Density: The Response to Spatial Efficiency and Social Intensity

The high-value street segments of Background networks display significantly higher densities than those of foreground networks, with narrower storefronts. This supports Hillier’s view of background networks as socio-culturally dense, that enables small scale stores to thrive in tight clusters [

35]. High densities, such as those in Chaotiangong West Street, can foster local identity and flexibility, as Jacobs’ emphasis for the fine-grained urban vitality [

7].

The high-value street segments of foreground networks, with lower densities and varying widths, prioritize economic efficiency, enabling the placement of larger-scale facilities such as financial institutions and recreation services [

20]. This divergence from background patterns challenges uniform density models and highlights how network structure shapes the relationship between land use scale and economic output [

15].

6. Conclusions

This paper contributes to the understanding of urban commercial spatial dynamics by applying Space Syntax’s dual network logic to analyze the spatial configuration of street stores in four Chinese cities—Tianjin, Nanjing, Zhengzhou, and Hong Kong. By comparing eight street segments, the results show that foreground and background networks generate different store configurations which correspond to different economic and socio-cultural roles at meso- and micro-scales. Characterized by high spatial integration, the foreground network supports a layout predominantly composed of chain stores, with high functional diversity and relatively low density, consistent with micro-scale economic efficiency. On the other hand, the background network tends to exhibit localized clustering, characterized by a predominance of sole stores, low functional diversity, and high density—suggesting embedded socio-cultural vibrancy.

Theoretically, this research extends the application of Space Syntax from the urban macro-scale to the fine-grained commercial structures of everyday urban life. By combining store-level data with topological measures, the paper operationalizes the foreground–background opposition as an indicator of economic orientation versus cultural localization. It extends the analytical power of the natural movement paradigm in explaining the emergence and persistence of commercial forms in different spatial contexts.

Practically, the results offer a replicable framework for commercial spatial analysis and contribute evidence-based insights to urban planning. In China, where coordination among commercial development layers remains insufficient, the foreground–background distinction can guide differentiated planning strategies: foreground network is more appropriate for promoting economically productive, standardized commercial centers. While background networks are essential for sustaining culturally embedded, community-based commerce. Such nuanced spatial strategies are particularly relevant in the post-pandemic era, as cities begin to negotiate economic revitalization, and spatial resilience.

Despite its contributions, the study is limited by its small sample size and reliance on pre-pandemic data, both of which could limit generalizability and temporal relevance. Further research is needed to extend to other geographies and typologies, incorporate dynamic pedestrian flow and demographic data, and explore how dual-network patterns manifest in other socio-spatial contexts, such as Western or less urbanized environments. Altogether, this study helps to illustrate the value of spatial configuration as a framework to understand socio-economic embeddedness and contributes to broader efforts to develop more holistic, responsive, and culturally anchored urban environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xinfeng Jia and Jing Huang; methodology, Xinfeng Jia; software, Xinfeng Jia, Yingfei Ren and Xuhui Li; validation, Xinfeng Jia and Guocheng Zhong; formal analysis, Xinfeng Jia, Yingfei Ren and Xuhui Li; investigation, Xinfeng Jia, Yingfei Ren and Xuhui Li; resources, Jing Huang; data curation, Yingfei Ren and Xuhui Li; writing—original draft preparation, Xinfeng Jia; writing—review and editing, Jing Huang; visualization, Yingfei Ren.; supervision, Jing Huang; project administration, Jing Huang; funding acquisition, Jing Huang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China through the following project: Street Area Augmentation and Composite Utilization Based on Quantitative Simulation Analysis of Ground Level Behaviour (51508516).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used for street network generation, POI analysis, and street view-derived features were collected and processed by the authors from open-source maps (Baidu, Gaode, Google, OpenStreetMap) and third-party POI data for the year 2019. Due to licensing restrictions on raw data, the processed datasets supporting the reported results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Haoyuan Wang, Mingliang Xu, Huifang Yan and Shihao Zhang for their participation in the drawing and data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hillier, B. Space is the machine UK. 1996.

- Sharifi, A. Resilient urban forms: A review of literature on streets and street networks. Build. Environ. 2019, 147, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, T.R. The broader economic consequences of transport infrastructure investments. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOBsang, T.; Zhen, F.; Zhang, S. Can urban street network characteristics indicate economic development level? Evidence from Chinese cities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TÜZEMEN, A.L.A. TÜRKİYE’DEKİ ULAŞTIRMA ALTYAPILARININ EKONOMİK BÜYÜMEYE ETKİSİ: ARDL SINIR TESTİ YAKLAŞIMI. SOCIAL SCIENCES STUDIES JOURNAL (SSSJournal) 2024, 4, 5935–5941. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, D.A.; Clark, T.N. Scenescapes: how qualities of place shape social life, 1 ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 2016; Volume 57734.

- Jacobs, J. THE DEATH AND LIFE OF GREAT AMERICAN CITIES. 2021, 126, 25-25.

- Mehta, V. The street: a quintessential social public space; Routledge: 2013.

- Gao, L.; Ma, Z.; Wei, D. Research on the influence mechanism of spatial distribution of urban commercial facilities (in Chinese). China Real Estate 2023, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamu, C.; Van Nes, A.; Garau, C. Bill Hillier’s legacy: Space syntax—A synopsis of basic concepts, measures, and empirical application. sustainability 2021, 13, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, D.; Clarke, G.P. Assessing GIS for retail location planning. Journal of retailing and consumer services 1997, 4, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, K.-W.; Cheng, H.-T. The effect of multiple urban network structures on retail patterns–A case study in Taipei, Taiwan. Cities 2013, 32, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Kumakoshi, Y.; Fan, Y.; Milardo, S.; Koizumi, H.; Santi, P.; Arias, J.M.; Zheng, S.; Ratti, C. Street pedestrianization in urban districts: Economic impacts in Spanish cities. Cities 2022, 120, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, C.; Xiu, C.; Zhang, P. Location analysis of retail stores in Changchun, China: A street centrality perspective. Cities 2014, 41, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Chen, X.; Liang, Y. The location of retail stores and street centrality in Guangzhou, China. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 100, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, S.; Strano, E.; Iacoviello, V.; Messora, R.; Latora, V.; Cardillo, A.; Wang, F.; Scellato, S. Street centrality and densities of retail and services in Bologna, Italy. Environment and Planning B: Planning and design 2009, 36, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nes, A. The impact of the ring roads on the location pattern of shops in town and city centres. A space syntax approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Centrality as a process: accounting for attraction inequalities in deformed grids. Urban design international 1999, 4, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coca-Stefaniak, A.; Hallsworth, A. Government policy for high street retail and town centres at a crossroads in England and Wales. Cities 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.-D. Spatial access to pedestrians and retail sales in Seoul, Korea. Habitat international 2016, 57, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih-Lin, T.; Yinuo, W.; Sanwei, H.; Fat-Iam, L. Spatial heterogeneity analysis between street network configurations and various service activities: evidence from the Wuhan metropolitan area. Comput. Urban Sci. 2024, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, W.; Yang, T.; Turner, A. Normalising least angle choice in Depthmap-and how it opens up new perspectives on the global and local analysis of city space. Journal of Space syntax 2012, 3, 155–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, K.; Turner, A.; Hillier, B.; Iida, S.; Penn, A.; Shibo, G.; Yang, T. Segment Analysis & Advanced Axial and Segment Analysis: Chapter 5 & 6 of Space Syntax Methodology: A Teaching Companion. Urban Des 2016, 1, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lebendiger, Y.; Lerman, Y. Applying space syntax for surface rapid transit planning. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2019, 128, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, I.; Yamu, C.; Tan, W. You have to drive: Impacts of planning policies on urban form and mobility behavior in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Journal of Urban Management 2021, 10, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L. From market allocation to government guidance: Reflections on the planning and management of urban commercial service facilities (in Chinese). 同济大学建筑与城市规划学院;上海市城市规划设计研究院规划四所(城市设计研究中心);上海市城市规划设计研究院信息中心 2019, 74-80. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Qi, Y.; Tang, W.; Liu, M. Street revival: Practice and reflection on the compilation of Demand-oriented street design guidelines (in Chinese). 同济大学建筑与城市规划学院;上海市城市规划设计研究院规划四所(城市设计研究中心);上海市城市规划设计研究院信息中心 2019, 90-98. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, Q. Dynamic evolution analysis of urban land use structure based on information entropy (in Chinese). Resources and Environment in the Yangtze River Basin 2002, 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Ekström, K.M.; Jönsson, H. Orchestrating retail in small cities. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 68, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Van Ham, M. Street network and home-based business patterns in Cairo’s informal areas. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; Pafka, E. Shopping morphologies of urban transit station areas: A comparative study of central city station catchments in Toronto, San Francisco, and Melbourne. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 96, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, Y.; Yoon, H.; Choi, Y. The effect of built environments on the walking and shopping behaviors of pedestrians; A study with GPS experiment in Sinchon retail district in Seoul, South Korea. Cities 2019, 89, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoppa, M.D.; Peponis, J. Distributed attraction: the effects of street network connectivity upon the distribution of retail frontage in the City of Buenos Aires. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 2015, 42, 354–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W. The evolution of street network in the old city of Beijing since the Republic of China based on the perspective of space syntax (in Chinese). Acta Geographica Sinica 2018, 73, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. The genetic code for cities: is it simpler than we think? In Complexity theories of cities have come of age: an overview with implications to urban planning and design; Springer: 2011; pp. 129-152.

- Van Nes, A.; Yamu, C. Exploring challenges in space syntax theory building: the use of positivist and hermeneutic explanatory models. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. The hidden geometry of deformed grids: or, why space syntax works, when it looks as though it shouldn’t. Environment and Planning B: planning and Design 1999, 26, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarloos, D.; Joh, C.-H.; Zhang, J.; Fujiwara, A. A segmentation study of pedestrian weekend activity patterns in a central business district. Journal of retailing and consumer services 2010, 17, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Penn, A.; Hanson, J.; Grajewski, T.; Xu, J. Natural movement: or, configuration and attraction in urban pedestrian movement. Environment and Planning B: planning and design 1993, 20, 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Spatial syntactic analysis of the distribution of catering industry based on Dianping data: A case study of Qianmen, Dongsi and Nanluoguxiang blocks in Beijing (in Chinese). Southern Architecture 2020, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Cities as movement systems. Urban Design International 1996, 1, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Scully, J.Y. Creating Walkable Places: Compact Mixed-Use Solutions. 2006.

- Alonso, W. Location theory. 1964, 78-106.

- Hallsworth, A.G.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. National high street retail and town centre policy at a cross roads in England and Wales. Cities 2018, 79, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H. Estimating the spatial impact of neighboring physical environments on retail sales. Cities 2022, 123, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Overview of foreign business planning process and content (in Chinese). International Urban Planning 2014, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W. Competitiveness of Business Chains:Economic Analysis (in Chinese). Research on Financial and Economic Issues 2002, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Zhou, X. Construction and evaluation of vitality index system of commercial center in Wuhan based on multiple big data (in Chinese). Urban and Rural Planning 2021, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, D.D.; Buchori, I.; Sejati, A.W.; Liu, Y. Shannon Entropy-based urban spatial fragmentation to ensure sustainable development of the urban coastal city: A case study of Semarang, Indonesia. Remote Sens. Appl.: Soc. Environ. 2022, 28, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q. Influencing factors of spatial distribution of block-type commercial outlets: A case study of Jiangnan area of Chongqing (in Chinese). Urban Issues 2019, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, B.; Berg, B.; Schramm-Klein, H.; Foscht, T. The importance of retail brand equity and store accessibility for store loyalty in local competition. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2013, 20, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliquet, G.; Guillo, P.-A. Retail network spatial expansion: An application of the percolation theory to hard discounters. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2013, 20, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, Ø.; Håvold, J.I.; Nesset, E. Impacts of store and chain images on the “quality–satisfaction–loyalty process” in petrol retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2010, 17, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).