Introduction

The Holocene transitions in Guyana are presently known from regional palynological studies (Daggers et al., 2018; Daggers & Plew 2022; de Granville, 1982; Hoock, 1971; Roeleveld, 1969; Rull, 1999; Van der Hammen, 1963; Wijmstra & Van der Hammen 1966). The lack of paleoenvironmental data has resulted in numerous gaps in the knowledge of long-term climate, and anthropogenic influences on the landscape along the coastal littoral. In this regard Early to Mid-Holocene shell middens provide a unique opportunity to employ a multi proxy approach to deepen our understanding of the human environment interplay linked to coastal foraging strategies and economies with the earliest occupation dating to 7500 BP.

The coastal littoral of Guyana represents what is believed to be among the earliest occupations of the coastal landscape and it provides substantial evidence of long-term human interaction with the environment and its resources (Daggers et al., 2018; Daggers & Plew 2023; Plew & Daggers 2016; 2022; Williams, 2003). These Early to Mid-Holocene-age shell mounds are accumulations of shell, faunal, human remains and material culture, demonstrating archaic populations diet breadth, cultural complexity and varying adaptations to the tropical environment (Plew & Daggers 2022). These sites constitute a built environment producing early evidence of colonization by prehistoric fisher populations along Guyana’s coast. They also support mounting evidence of population movement across the Amazon and highlights the role of archaic populations in shaping the landscape through anthropogenic influences (Williams, 2003; Lombardo et al., 2018, 2020) although the latter widely disputed in Amazonia particularly in during the Holocene (Lombardo et al., 2018; McMichael et al.,2023) These interactions can be seen as a signal of human adaptation to the Holocene environment (Plew, 2005; Daggers et al.,2018; Daggers & Plew 2003), suggesting dispersed seasonal landscape use and mobility, influenced by seasonally available resources (see Capriles et al., 2019 for discussion). This line of coastal interaction is important in understanding the role of the marine ecosystems on the development of past human societies and economies (Bas et al., 2023). The effects of environmental change during the Pleistocene and Holocene resulted in shoreline movement and submersion of portions of the coastal zone and past anthropogenic features including shell middens in various parts of the globe (Alvarez et al., 2010; Hale et al., 2021), as recently demonstrated along the coast of northern Brazil (see Calippo, 2008) (refer to Farebridge, 1983 for discussion on Pleistocene, Holocene Boundary). In Guyana’s context this human environmental interaction is further demonstrated in the presence of over 33 shell midden features and vegetation changes throughout the northwestern coast referred to as Zone 1 environments by (Johnson et al., 2023). Although only eleven Guyanese shell middens have been radiocarbon dated, eight middens produced Early to Mid-Holocene range dates (see

Table 1). However, only seven (7) of these sites are well documented and have produced extensive archival materials (see

Figure 1.) The goal of this study is to evaluate human responses to environmental change by integrating archival and recent zooarchaeological evidence with published stable isotope data from shell middens, as well as sediment and pollen records. This multi-proxy approach is applied across seven study sites to infer land-use strategies and foraging behaviors (see Palmisano, 2020, for comparable methodologies), thereby offering new insights into possible patterns of land use in the Amazon by prehistoric populations.

The Guyanese Shell Middens

The shell middens of Guyana’s coast are a unique feature of the Northeastern South American coastline as they do not occur in Suriname or French Guiana but are common in the southern Caribbean where at 6,000 BP the Barwari Trace and El Conchero shell midden occupations are an Archaic pattern similar to the Alaka phase sites of the Guyana shell mounds. These Early to Middle Holocene-age pre-ceramic sites are located near mangrove swamps ranging in heights ranging between 1 and 15 meters (Evans & Meggers, 1960:63). Within the vicinity of the Northwestern coast there are 33 documented shell midden sites geographically located between 5 to 15 km apart situated along major tributaries, creeks and estuaries. These accumulations served as living areas and as places for burial dating prior to the emergence of agriculture economies. The mounds are composed primarily of alternating layers of zooarchaeological remains including but not limited to, small striped snail, clams, oysters and crab remains, brackish water fish remains including occasional whales, rock fish, and small to large terrestrial mammals including jaguars, peccary and occasional reptiles including caymans, snakes and turtles and birds have been reported (Plew et al., 2012, 2016; Williams, 2003). There is a strong connection with shell middens and funerary practices. Human burials are well documented across the seven (7) sites included in this study. Whether internment occurred during occupation or after abandonment of the site is yet to be determined.

Excavations by Williams (2003) and others have produced evidence of features including hearths, post molds and several storage pits (Plew, Willson & Simon 2007; Plew at al., 2013; Plew & Daggers 2016). A range of chipped and ground stone artifacts which date to the pre-ceramic occupations of a number of shell mound deposits as early as ca. 7200 BP, and forms the basis of Evans & Meggers’ (1960) description of the so-called and pre-ceramic Alaka phase which is associated with these sites (Daggers et al., 2018; Plew & Daggers 2016, 2022; Williams, 2003). It is worth nothing that these sites do produce a small assemblage of shell tempered ceramic of the Wanaian plain (Plew & Daggers 2022). (see Rick, 2023 for detailed categorisation and discussion of shell midden composition on a global scale).

Methods

The extent of northwestern coast land use and spatial distribution of sites is drawn from field surveys. Understanding the distribution and density of sites and resources along the northwestern coast can lend insight into the Archaic environment and foraging behavior on a spatial and temporal scale that can be used as a proxy for determining demography, predation and land use (Palmisano, 2017, 2020). In the absence of high-resolution paleoenvironment data, early researchers such as Williams (1982, 2003) argued that the Early Holocene was a period of substantial instability during which people relied heavily on different shellfish species common during sea-level fluctuations and the presence of brackish and fresh waters. Assessment of William’s arguments requires determining the extent to which Holocene coastal environments changed and a re-evaluation of the faunal record of shell middens. New insights offer greater clarity into shifts in resource selection and human environment interplay. We rely on site observation, qualitative data and isotopic analysis of human and faunal remains including sediments from shell middens, including archival paleo pollen records to establish the nature of the environment and determine the extent of past land use strategies and foraging behavior. The seven Early to Mid-Holocene sites included in this study were excavated between 1981 and 2020. These Holocene middens were selected because of the availability of published materials, the presence of human burials and multiple radiocarbon dates. These data prove valuable to assessment of responses to environmental change (Balsera et al., 2015; Crema et al., 2016; Flohr et al., 2016; Maher et al., 2011, Timpson et al., 2014; Woodbridge et al., 2014).

Sites including Piraka, Wyva Siriki and Barabina were a part of several field seasons of data collection that includes surface collections. Little Kanaballi has only been investigated once. The study also relied on published materials on Barabina, Pairaka, Waramuri and Kabakaburi. The variation in data sets used in this study was influenced by varying research foci and methods utilized or adopted by different researchers during investigations. The availability of culturally associated materials was further influenced by taphonomic processes both natural and cultural.

As a result of these limitations, faunal data associated with each site were pooled to provide insight into diet breadth and the environmental context in which they were acquired. The carbon and oxygen isotope data obtained from human remains, and transported sediment from sites provided opportunities for inferences about the past, as these isotopes provide greater insight into the landscape vegetation and surface water temperature which are variables necessary to determine the environmental context of past human occupation and resource exploitation.

Environmental Reconstruction

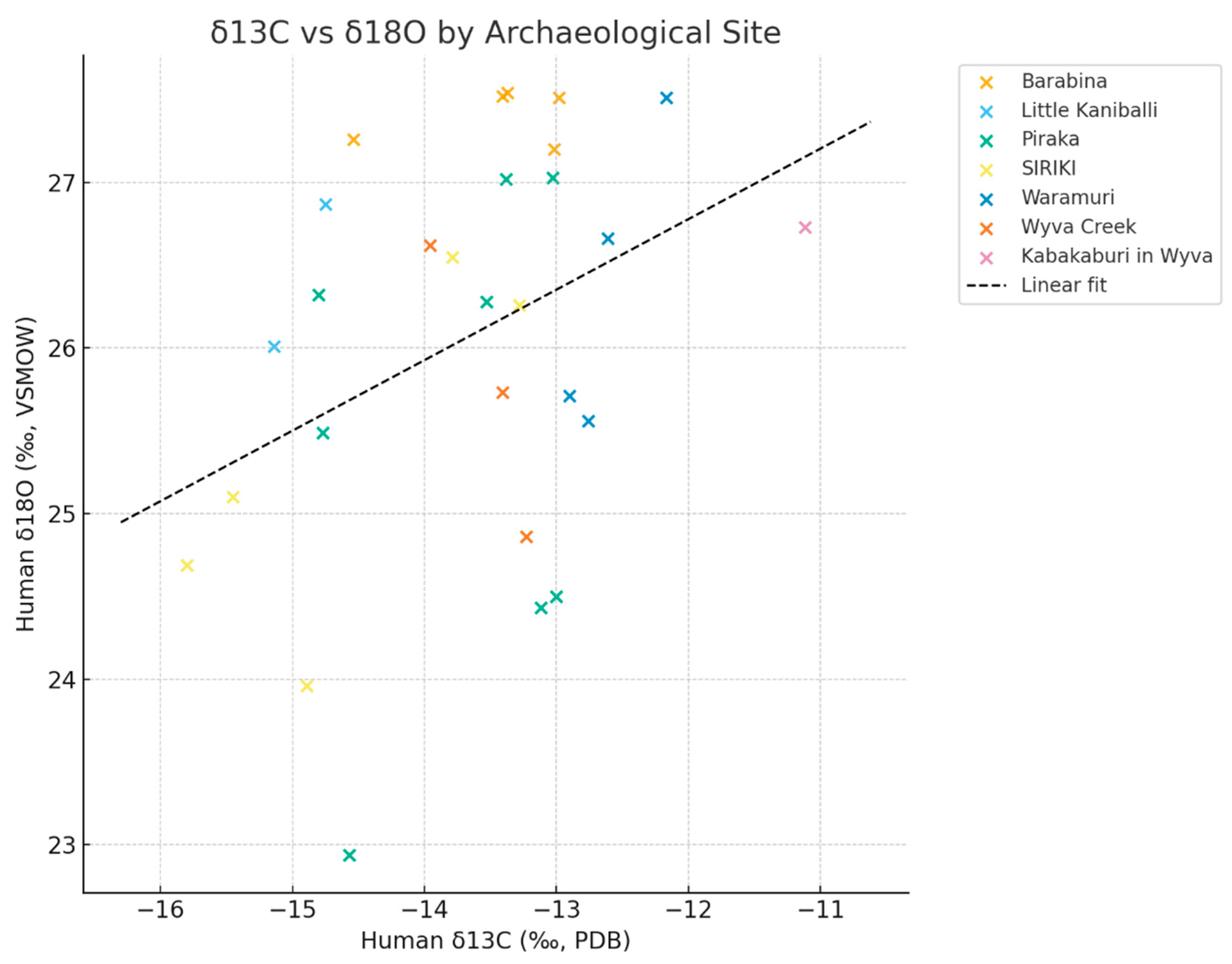

Holocene environmental data for the northwestern coast was derived from the analysis of human and faunal remains from seven sites excavated by Denis Williams during the 1980s and more recent field seasons conducted for the excavations of Little Kaniballi (Daggers 2017; Daggers et al., 2018), Siriki (Daggers 2020; Plew, Wilson & Daggers 2012; Plew & Daggers 2016;) and Wyva Creek (Plew & Wilson 2009; Daggers, 2016, 2021). The variations in stable carbon δ13C and oxygen δ18O isotope compositions were analyzed to assess the degree of dietary constancy and moisture variability during the early Holocene against radiocarbon dates obtained from varying chronologies across the seven sites. These data sets were used as a proxy for determining the likelihood of any significant changes in the environment that may have influenced the use of marine and terrestrial resources in the Northwest (Daggers et al., 2017; Daggers & Plew 2022). We found that Oxygen isotope values showed no significant differences between localities (25.7‰ to 26.7‰, ANOVA, p = 0.2274) while carbon isotope values exhibited differences between sites (-14.7‰ to -11.1‰, Daggers et al., 2018: 7-8).

The δ13C values from all samples fall within the range indicative of C3 plant resource utilization in an open canopy environment (Kohn, 2010), a conclusion supported by carbon isotopic analyses of modern examples of local plants, which are dominantly C3 photosynthesizing plants. Plant carbon values were consistent with the findings of Guehl, et al., (1998) for regional vegetation in Guyana as were diet-corrected δ 13C values based on the local plant isotopic compositions, these were also consistent with the bone and tooth enamel sample compositions.

Locations with 14C dates indicate uniformity over time and between locations. Pooled δ18O composition of bone and tooth apatite suggests that isotopically similar drinking water sources were accessed at all sites, and that other variables known to influence oxygen isotopic compositions in surface water (precipitation sources, temperature, evaporative enrichment) were relatively similar across all sites, a fact that fails to support Williams’ (1982, 2003) assertions. Data suggest an increasing reliance on C3-based resources and fauna that are C3 -fed, suggesting that these populations were utilizing resources from an open canopy environment consistent with an open forest landscape common in the Amazon region, which is supported by van der Hammen (1982), Ledru (1993), Pessanda (1996) and Tardy (1998) who reported a series of dry periods in the Central Amazon Basin during the early and Mid-Holocene which suggest vegetation changes and forest retreat associated with dry climatic conditions between 11,000 and 4500 BP. (Daggers et al., 2018).

The later Holocene saw increasing use of multiple resources, including niche resources, specifically starchy plants as suggested by Williams (2003) (Plew, Wilson & Daggers 2012). However, shellfish remained the primary diet. The emergence of mangrove forest during this period as reported by (van der Hammen & Wijmstra 1964), would have provided favorable habitat for both marine resources and small to medium terrestrial fauna. The depletion of δ13C approaching the Mid-Holocene is reflected in the δ13C values by depth and age, of transported sediments at Wyva, Siriki, Piraka and Barabina mounds, suggesting an environment dominated by C3 plants.

(Daggers et al., 2018 for discussion). This is also supported by Hammond, Steege & van der Borg’s (2006) study of soil charcoal in the wet tropical forest of Guyana.

To further evaluate the range of Early to Mid-Holocene resources exploited by northwestern coastal fisher populations, and their dependance on shellfish beyond a secondary resource we analyze the faunal assemblages reported by Williams and those resulting from more recent investigations of the mounds. We note that Williams reports few faunal remains; there are instances where none were reported for some excavations. This is attributed to his research questions at the time and his methods of excavation and data collection.

Faunal Record

Faunal collections are not abundant or well documented in Guyana’s archival records. As a result, the representation of different fauna and the distribution of species across sites is at present imperfect. Where possible identifiable faunal remains were grouped by taxa (see

Table 2). Considering the limited nature of the zoo archaeological record, and the historic deficiencies of reporting faunal remains recovered in Guyanese shell mounds, the faunal remains in this study were pooled. The absence of fauna reported by Williams and others (including Evans & Meggers 1960) is attributed to both preservation and data recovery techniques. These remains recovered from middens are believed to be the result of harvesting and consumption and can provide insight into past subsistence and economy of past populations (Ahrberg, 2007; Alvarez, 2010; Bailey, 1975). Faunal remains recovered from several sites specifically Barabina, Piraka and Siriki were charred, likely because of cooking activities on site which resulted in the formation of conglomerates of shell and charcoal (Plew & Daggers 2017; Williams, 1981). A diversity of fauna was recovered from the seven archaeological sites including the dominant marine resources

Puperita pupa, or (Zebra Nerites), and Crab remains represent 80% of the assemblages in some instances while reptiles, amphibians, fishes, birds, and unidentifiable mammals account for the remaining 20% of resources exploited during occupation at most locations.

Mollusca

Guyanese shell middens as noted are dominated by mollusks species, specifically Puperita pupa or zebra nerite. These snails’ range between 0.5 and 1.7 cm in diameter. The mean live weight of a nerite is estimated to be 0.133 gram per shell (for further discussion see Williams 1981). Based on estimates provided by Plew, Pereira and Simon (2007) each 10 cm level of a 1 x 2m unit at Kabakaburi produced approximately two (2) gallons of nerite shells. However, it is important to note that the shell density at this site per unit level was much less when compared to other sites which have different rates of accumulation and less influence of sediment buildup which can be attributed to the frequency of occupation. Other species present include Phacoides pectinatus commonly known as (Thick Lucid) or clams, Mangrove Oyster, Modiolus americanus or (Tulip Mussel) and Conch of the following species Lobatus gigas and Rock shell of the family Purpuridae. These deposits occurred abundantly at the lower levels of several sites (Plew &. Daggers 2017; Plew 2016, 2018; Williams, 1981). Nerites and Thick Lucid are common within the Mangrove swamps and brackish water environment of Guyana. These sites present the earliest evidence of the use of molluscs by archaic hunter gatherer population in Guyana. Bivalves such Phacoides pectinatus were recovered across the seven sites, occurring primarily at the lower depths of the middens. These shell remains range in size between 4 and 5.5 cm, indicating the harvesting of mature Lucid species. Recent studies have suggested that the Phacoides pectinatus populations can be affected by salinity, increased precipitation and sea level rise due to climate change (Doty 2015), however, Lucids are mature and available year-round. Mangrove oysters, however, were recorded in significant density in only two (2) of the seven (7) study sites, Barabina and Waramuri. Within the context of both sites, oyster distributions were concentrated in the lower levels, at depths below 280 cm. These contexts yielded Early Holocene dates, with both sites situated in proximity to the shoreline and primary drainage areas. The average size of oyster shells within the collection ranges from 4 to 7cm the suggested arrange of maturity (Menzel & Nascimento 2019) which is attained within 18 months in temperatures between 25-30oc. Givent the average weight of a fully mature oyster is approx. 50g providing 5-10 calories per medium oyster. This nutrient packed resource is also high in B12 and other essential minerals.

Crustaceans

The pinchers of crabs are commonly found throughout the seven archaeological sites. The common species identified in the northwestern middens include Ucides cordatus commonly referred to as the swamp ghost crab, that are commonly found today and widely exploited during the period of December and May, typically the rainy period by native coastal populations. These species live in brackish water environments of the tropics and are nutrient dense resources providing higher calories than that of a mangrove oyster while contributing other minerals to the diet (see Carvalho et al., 2007 for discussion on nutrient value). The Remains of crabs are found across all sites in high density at specific intersections or stratigraphy indicating seasonal opportunistic exploitation.

Mammals

The remains of terrestrial mammals within the shell midden deposits are relatively limited though as noted we attribute this to recovery techniques. The isolated remains of a mineralized porpoise bone were recovered at Wyva Creek (Plew & Wilson 2010). The recovery of such remains may suggest scavenging along the shorelines which is believed to be approximately 13km inland prom the modern shoreline. Given the tropical environment of the mounds the preservation of terrestrial faunal remains has proven difficult hence a large percentage of recovered terrestrial faunal remains are heavily fragmented and unidentifiable. Identifiable faunas include peccary, the agouti, and other rodents. In addition to the teeth remains of Jaguar were documented at the sites of Piraka, Barabina and Siriki (Daggers, 2020; Plew, 2016; Williams, 1981). The limited presence of terrestrial mammal remains suggests that shell middens were used to accommodate seasonal moves and exploitation of marine resources within specific areas that are attributed to occupation of an open canopy environment.

Fishes

Fish remains include vertebra, otoliths, and skull fragments. The vertebrae vary in size from 0.5 mm to 4 cm with growth rings on caudal vertebrae which suggest fish in a range of 3-5 years old with live weights of 10-15 pounds and more (Plew & Daggers 2017; Williams, 1981). There are cases where fishes are unidentifiable by species, however; the identifiable fish remains recovered across the seven sites include those of brackish water and sea catfish including but not limited to

Sciades parkeri commonly referred to as (Gilbacker) and

Sciades herzbergii commonly called the (Cuirass). Occasional remains of giant rockfish and sting rays were recovered at Wyva Creek and Siriki. (Plew & Wilson 2010; Plew, Wilson & Dagger 2012). Of note is the significant number of fish remains recovered by Williams (1981) at Barabina (see

Table 2). We attribute this to multiple field seasons of excavation and site location. To some extent the foraging economy was driven by predictability or seasonal resource exploitation. Macronutrient data of the Gilbacker, a member of the catfish family was used to estimate the nutrient values. Voiding minor differences in gender, the Gilbacker measures roughly 30 cm in length and weighs slightly more than three pounds. The general Kcal values for catfish are c. 150 calories per 100 grams. At this return rate an average Gilbacker might produce 1260 calories and 216mg of protein at 18mg per 100 grams. The resource is also high in B12, Omega-3 and selenium. Assessing the potential of the nutrient values of fish reported at Barabina where over 15,000 remains are reported clearly demonstrates the predominance of fish in the mound population diet. The importance of fish among Amazonian populations is as noted by Gragson (1992) as more dependable than game.

Reptiles and Birds

Reptiles and birds are represented within the shell midden’s faunal assemblages. The remains of the skull with teeth of caymans were recovered at several sites, as well as fragments of tortoise shells and vertebrates of unidentified snakes. Fragments of medium to large bird remains have been documented within middens including bones at Barabina. The beak of a bird at Piraka, and the claw of a bird which appears to have been partially modified were recovered at a Siriki (Plew, 2016; Plew & Daggers 2016; Williams, 1981). Ethnographically birds are important cultural symbols and biological indicators among indigenous groups of Guyana. However, medium to large size birds such as the Macca and the Crax alector or (Powis) are sometimes seasonally incorporated into the diet.

The majority of remains are from small and medium sized mammals with most medium sized specimens from Kabakaburi and Siriki. Small taxa are present in 6 sites, but they are abundant in one. Medium sized mammals are found in five (5) sites but rank first in frequency twice. Of greater interest is the ubiquity of fish which occur in all seven sites and rank first in frequency at Barabina and Siriki.

As seen in

Table 2, more than 19,821 faunal remains have been recovered. This score does not include the

Puperita pupa which dominated the sites at approximately 80% of the site content. Small, medium, and large mammals were represented by more than 2,110 remains. Mammals ranked first in the assemblage of two sites when compared to other resources. Unidentifiable mammals accounted for n=1,180 of the total sample. Birds were scarcely represented. Fish (n=15) appeared across five sites and ranked first in the assemblage of 2 sites. Reptiles (n=6) only appear within the record of four sites. Crabs numbering greater than (n= 347) were present across all (n=7) study sites but ranked first only in the assemblage of one site. Mollusks (n=2,365) were present across all sites but ranked first in the record of one site.

Discussion

Oxygen δ18O isotope compositions of Early to Mid-Holocene shell middens has provided a new understanding of Holocene climatic conditions of Guyana, improving our understanding of the role a changing environment played in land use, food security and resource use during the Early to Mid-Holocene. The time span represented by much of the dated materials falls within the Holocene Climatic Optimum (HCO), spanning the period of 8000-5000 years B.P. Areas of the northern Amazon may have seen reduced precipitation leading to shifts toward more drought-tolerant dry forest taxa and savannah in ecotonal areas (Mayle et al., 2004). The broadening of the diet breadth and the value of small mammals incorporated into the diet is demonstrated across all sites and supports our findings suggesting a more open canopy environment during warmer intervals followed by gradual change in the vegetation structure to a forested environment during the Mid-Holocene—the latter resulting from shoreline movement and possible human habitation. Dietary variation is noted in the zoo-archaeological, and isotope data produced across the seven sites. These records indicate a period of warming in the Early Holocene as noted at Piraka, Wyva, Siriki and Little Kanabali with δ18O ranges between 26-28 ‰ and marked depletion of δ18O rages at Barabina during the Mid Holocene suggesting climate fluctuation to a wetter environment. This variability is not believed to have impacted marine resource availability. As observed across sites, it may have played a role in resource abundance, since fluctuations in the environment will influence variables including but are not limited to water temperatures, precipitation and salinity all of which are factors affecting marine and brackish water resources. This appears to be the case with Waramuri and Barabina where Mid-Holocene deposits produced higher densities of Oyster, Conch and large fish remains. Similarly, the decreasing density and distribution of Phacoides pectinatus across the seven sites is observed in the Mid Holocene following increased precipitation, a variable which is known to impact productivity of this resource (Barreira et al., 2018).

Data indicates the probability of a strategy of foraging consistent with seasonal resource selection and mobility (Daggers et al., 2018). Isotope ratios suggest that the Archaic Guyanese coastal populations mobility and land-use strategies were influenced by environmental factors coupled with resource availability, a position posited by (Kelly, 1992; Kuhn, 2016) regarding modern hunter-gatherer mobility as reflected in δ

18O record of the data set (see Daggers et al., 2018). Most samples cluster around ~26–28‰ (VSMOW), with one smaller cluster centered around ~24.3‰ and ~25‰. The lower δ

18O cluster may reflect different water sources, or possibly different mobility or seasonal intake (see

Figure 2).

In this context shifting shorelines and ecological structures would have impacted the availability of niche marine and terrestrial resources as demonstrated above, undermining the productivity of estuarine or marine resources such as fish resources. These factors would have undoubtedly influenced foraging range and result in the exploitation of alternative food resources including small and medium sized mammals though sparsely represented in the record. These adaptations would have increased populations exposure to a broader diet breadth (Kuhn, 2016) as demonstrated in the zooarchaeological record. Notably the zooarchaeological record of Barabina, Wyva and Warmuri suggest a broader diet breadth of aquatic resources.

Carbon δ13C isotopic composition of archaeological human and faunal records signals variations in the environments of the environment across seven-study sites. Tukey HSD post-hoc pairwise comparison found significant differences between the locations of Kanaballi and Barabina (p < 0.001), Piraka and Barabina ( p < 0.001), Siriki and Barabina ( P < 0.001), Waramuri and Little Kanaballi (p < 0.001), Waramuri and Piraka (p < 0.01), Waramuri and Siriki (p < 0.001), suggesting greater changes, to an environment with less forest cover during the mid Holocene. The δ13C values are indicative to a C3 dominant diet and fits a near shore estuarine adaptation. The presence and absence of resources within and across sites may, however, reflect occupation intensity and seasonal resource exploitation and site use by archaic populations occupying the northwestern coast of Guyana.

The data suggest that the environmental structure and vegetation of the Holocene may have influenced the distribution and abundance of terrestrial mammalian biodiversity (Benedek et al., 2021), as Lambert et al., (2006) have demonstrated that variables such as openness of forest correlates with the appearance of small mammals in the Amazon. Resource exploitation is seen as one influenced by group size and available opportunities taking into consideration tradeoffs in terms of calories and required effort exerted into resource acquisition coupled with the productivity of the environment. In favorable periods fish resources appeared to be highly sought after by populations when considering the greater caloric return rates fish to mammals and shellfish. The exploitation of fish is demonstrated in the faunal record across the seven sites and rank first in abundance after Puperita pupa (nerites) at two locations during the early Holocene. Land use intensity may be linked to productivity, resource acquisition for both consumption and increasing hunting and gathering efficiency. Analyzed sediments provide evidence of fires although there is no clear evidence that this was human induced. Landscape firing could indicate early evidence of resource landscape alterations for purposes of increasing resource availability.

Van der Hammem ‘s (1964) documentation of the emergence of Mangrove swamps between 6,000 and 4,000 B.P. supports a condition of fluctuating environments as indicated by the δ18O isotopic record. The recorded fluctuations may have resulted in the silting of the coastline creating a more favorable environment for vegetation changes to occur, including the emergence of Mangrove Forest. Nascimento et al., (2022) argue that evidence of vegetation changes and the appearance of charcoal within the archaeological record can be used to infer human activity in the Amazon and Guiana shield an argument also made by Bush et al., (2025). While the record has produced evidence of fire along the northwestern coast, we fail to provide evidence of human involvement. On the other hand, the northeastern coast clearly demonstrates the use of human induced fires for landscape manipulation during the Mid-Holocene in the production of Amazonian Dark Earth (ADE) which are anthropogenically produced with charcoal, refuse and added minerals (Lucheta et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2021). Resource manipulation and land use by past populations along the northwestern coast is, however, reflected in the volume of shell middens throughout the northwestern coast and the vegetation distribution within proximity of the known shell midden sites.

Of Additional relevance, Van Andel (2000) alludes to the reliance of indigenous population for thousands of years on non-timber forest products along Guyana’s northwestern coast for food, medicine, and equipment (for discussion see Van Andel 2000). Recent studies by Odonne et al., (2019) suggest that pre-Colombian populations in the Guiana Shield influenced modern forest structure and diversity by the introduction of edible fruit trees. While the ecological impact of prehistoric populations on forest in the Guiana shield is relatively unexplored, recent population intervention of vegetation in Suriname suggest that past vegetation manipulation occurred within 0 to 8km from archaeological sites and as resulted in long lasting ecological legacies in the modern forest (Witteveen et al., 2024). This ecological impact on vegetation composition is evident in the immediate proximity of Guyanese shell midden sites, where the relative usefulness of tree species increases significantly. Such patterns reflect the long-term influence of human activity on Guyana’s coastal ecosystems, as nutrient enrichment from midden deposits altered soil chemistry and promoted the growth of species valuable for food, medicine, and material culture. These dynamics influenced the processes of niche construction in which past human settlement and subsistence practices actively shaped ecological trajectories. These modifications produced enduring ecological legacies, reflecting cultural adaptation within the forest composition and contributing to the mosaic landscapes observed along the northwestern coast of Guyana.

Shell midden density and distribution along the Waini and Pomeroon Rivers suggest that climate oscillation would have seen HG populations adjust to an ever changing and increasingly diverse environment by adopting a foraging strategy geared towards the broadening of diet breadth. This included the acquisition of marginal resources during periods where the abundance and diversity of resources was most likely influenced by the onset of a wetter environment as indicated in the isotopic record produced by at Barabina.

Conclusion

Drawing from available data, we conclude that the northwestern coast remained productive until the late Holocene, as the size and distribution of the mounds decreased in the Late Holocene due to shoreline regression. Pollen data on the coast of Brazil suggest changes of the marine ecosystem that impacted coastal areas approximately 2000 B.P. This resulting in silting of the estuarine (Toso 2021). In turn, shifts in the ecosystem would have played a role in vegetation structure, further impacting the availability of niche marine resources such as fish and mollusk as well as the availability of terrestrial fauna. This could well be the scenario along the northwestern coast of Guyana.

A noted decline in the number of mounds possibly signals decreasing productivity of the area and the gradual adaptation to horticultural dependency. Archaeological evidence of raised fields containing ADE is taken to represent the emergence of horticultural activities during the Mid-Holocene along the northeastern coast of Guyana within a range of cal. 6270 to 790 B.P. (Shern et al., 2017). The appearance of Early Mabaruma phase pottery dated between 3550 and 1450 BP at Barabina suggests the incipient stages of domestication along the northwestern coast. However, radiocarbon dates indicate the continuous seasonal use of the mounds into historic periods as is evident at Siriki which produced a more recent date of 270 ± 30 BP—though it not clear that utilization of shellfish is the primary cause.

The seasonal exploitation of mollusks as a dietary protein supplement remained the core of the prehistoric economy during the Early to Mid-Holocene as it likely relates to resource availability and group size. In this regard the zooarchaeological record documents evidence of fishing intensification that is coupled with increased utilization of small mammal species adapted to warmer landscapes (Daggers and Plew 2022 for discussion). Shoreline regression during the Mid-Holocene is believed to have further influenced the productivity and distribution of resources along the coast, minimizing travel and increasing residential mobility of populations over time. A more seasonal use of resources was important for building resilience of coastal populations and was supported by the emergence of mangrove forest and the gradual development of the modern forest environment during the Mid -Late Holocene transition. These emerging physical environments are believed to have produced ecosystems supporting and increasing use of non-molluscan fauna, especially fish. We conclude in part that shellfish collection as well as an increasing use of vertebrate resources may vary significantly by virtue of localized coastal landscapes as seen in coastal Puerto Rico (Pestle et al. 2001).

References

- Åhrberg, E. Fishing for Storage: Mesolithic Short-Term Fishing for Long Term Consumption. In Shell Middens in Atlantic Europe; Milner, N., Craig, O., Bayley, G., Eds.; Oxbow Press: Oxford, 2007; pp. 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, M.; Godino, B.I.; Balbo, A.; Madella, M. Shell Middens as Archives of Past Environments, Human Dispersal and Specialized Resource Management; Quaternary International, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, C. A. R.; Santana, L.M.B.Q. Rainfall Seasonal Variation Effect Once Productive Cycle of the Bivalve Phacoides pectinatus from Semiarid coast of Brazil. Arq. Ciên. Mar, Fortaleza 2018, 51(2), 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G.N. The role of Molluscs in Coastal Economies: The Results of Midden Analysis in Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science 1975, 2(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsera, V.; Bernabeu Auban, J.; Costa Carame, M.; Díaz del Río, P.; García Sanjuan, L.; Pardo, S. The Radiocarbon Chronology of Southern Spain's Late prehistory (5600e1000 cal BC): a comparative review. Oxf. J. Archaeol. 2015, 34(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, M.; Salemme, M.; Santiago, F.; Briz i Godino, Ivan; Álvarez, M.; Cardona, L. Patterns of Fish consumption by Hunter-Fisher-Gatherer People from the Atlantic coast of Tierra del Fuego during the Holocene: Human-environmental Interactions. Journal of Archaeological Science 2023, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, A. M.; Sîrbu, I.; Lazăr, A. Responses of Small Mammals to Habitat Characteristics in Southern Carpathian forests. Science Report 2021, 11, 12031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binford, L.R. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology; Academic Press: New York, NY, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Braje, T.J.; Dillehay, T.D.; Erlandson, J.M.; Klein, R.G.; Rick, T.C. Finding the first Americans. Science 2017, 358, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, M. B.; Sales, R. K.; Neill, D.; Valencia, B. G.; León-Yánez, S.; Stanley, A.; Sinkler, W.; Bennett, I.; Gomes, B. T.; Land, K.; McMichael, C. N. H. Ecological legacies and recent footprints of the Amazon's Lost City. Nature communications 2025, 16(1), 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calippo, F. Os Sambaquis submersos do Baixo Vale do Ribeira: um estudo de caso de Arqueologia Subaquática. Revista de Arqueología Americana 2008, 26, 153e172. [Google Scholar]

- Capriles, JM; Lombardo, H; Maley, B; Zuna, C; Veit, H; Kennett, DJ. Persistent Early to Middle Holocene Tropical Foraging in Southwestern Amazonia. Science Advances 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crema, E.R.; Habu, J.; Kobayashi, K.; Madella, M. Summed Probability Distribution of 14 C dates Suggests Regional Divergences in the Population Dynamics of the Jomon Period in Eastern Japan. PLOS One 2016, 11(4), e0154809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, W.T. Environmental Controls on the Diversity and Distribution of Endosymbionts Associated with Phacoides pectinatus (Bivalvia: Lucinidae) from Shallow Mangrove and Seagrass Sediments, St. Lucie County, Florida. Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3548.

- Daggers, L.B.; Mark, G. P.; Edwards, A.; Evans, S.; Trayler, R.B. Assessing the Early Holocene Environment of Northwestern Guyana: An Isotopic Analysis of Human and Faunal Remains. Latin American Antiquity 2018, 29(2), 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daggers, L.B.; Plew, G.M. Moving Beyond: New Methods to Assess Holocene Environmental Change in the Northwestern coast. In Archaeology on the Threshold: Studies in the Processes of Change J.D; Waddle, Hitchcock, R.K., Schmader, M, Yu, Pei-Lin, Eds.; University of Florida Press, 2022; pp. 206–219. [Google Scholar]

- DeGranville, J.J. Rain Forest and Xeric Flora Refuges in French Guiana. In Biological Diversification in the Tropics; Prance, G.T., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, 1982; pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, CA.; Meggers, B. J. Archeological Investigations in British Guiana. In Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 197; Smithsonian Institution: Washington D.C, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Flantua, S. G. A.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Vuille, M.; Behling, H.; Carson, J. F.; Gosling, W. D.; Hoyos, I.; Ledru, M. P.; Montoya, E.; Mayle, F.; Maldonado, A.; Rull, V.; Tonello, M. S.; Whitney, B. S.; González-Arango, C. Climate Variability and Human Impact in South America during the last 2000 years: Synthesis and Perspectives from Pollen Records. Clim. Past 2016, 12, 483–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flohr, P.; Fleitmann, D.; Matthews, R.; Matthews, W.; Black, S. Evidence of Resilience to Past Climate Change in Southwest Asia: Early Farming Communities and the 9.2 and 8.2 ka events. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 136, 23e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbridge, R.W. The Pleistocene-Holocene Boundary. Quaternary Science Reviews. 1982, 1, pp. 215–244. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0277379182900105. [CrossRef]

- Guehl, J.M.; Domenach, A.M.; Bereau, M.; Barigah, T.S.; Casabianca, H.; Ferhi, A.; Garbaye, J. Functional Diversity in Amazonian Rainforest of French Guyana: A Dual Isotope Approach (δ15N and δ13C). Oecologia 1998, 116, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gragson, T.L. Strategic Procurement of Fish by the Pune. As south America fishing culture. Human Ecology 1992, 20(1), 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.C.; Benjamin, J.; Woo, K.; Astrup, P.M.; McCarthy, J.; Hale, N.; Stankiewicz, F.; Wiseman, C.; Skriver, C.; Garrison, E. Submerged landscapes, marine transgression and underwater shell middens: Comparative analysis of site formation and taphonomy in Europe and North America. Quat. Sci. Rev 2021, 258, 106867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D.S.; ter Steege, H.; van der Borg, K. Upland Soil Charcoal in the Wet Tropical Forests of Central Guyana. Biotropica 2006, 39, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoock, J. Les savanes guyanaises: Kourou. Essai de phytoécologie numérique. In Mém. ORSTOM; 44: Paris, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.A.; Jamski, Gianna; Tanigha, J.; Mcnellis, T.; Niesen; Scimeco, R.; Prutt, A.; Waddle, J. D.; Hitchcock, R.K.; Schmader, M.; Yu, Pei-Lin. Differentiating Ecological context of Plant Cultivation and Animal Herding on the Northwestern coast. In Archaeology in the Threshold; 2022; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, J.; Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A.; Vallverdú, J.; Gómez de Soler, B.; Rivals, F. Neanderthal logistic mobility during MIS3: Zooarchaeological Perspective of Abric Romaní level P (Spain). Quaternary Science Reviews 2019, 225, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, M.J. Carbon Isotope Compositions of Terrestrial C3 Plants as Indicators of Paleoecology and Paleoclimate. PNAS 2010, Vol.107(No.46), 19691–19695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, S.L.; Raichlen, D.A.; Clark, A.E. What moves us? How mobility and Movement are at the Center of Human Evolution. In Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews; 2016; Volume 25, pp. 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.L. Mobility/Sedentism: Concepts, Archaeological Measures, and Effects. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1992, 21, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, T.D; Malcom, J.R; Zimmerman, B.L. Amazonian Small Mammal Abundances in Relation to Habitat Structure and Resource Abundance. Journal of Mammalogy 2006, 87(Issue 4), 24 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledru, Marie-Pierre. Late Quaternary Environmental Climatic Changes in Central Brazil. Quaternary Research 1993, 39, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucheta, A. R.; Cannavan, F. de S.; Tsai, S. M.; Kuramae, E. E. Amazonian dark earth and its black carbon particles harbor different fungal abundance and diversity. Pedosphere 2017, 27(5), 832–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, U.; McMichael, C. N. H.; Tamanaha, E. Mapping pre- Columbian land use in Amazonia. PAGES 2018, 26, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, L.A.; Banning, E.B.; Chazan, M. Oasis or mirage? Assessing the Role of Abrupt Climate Change in the Prehistory of the Southern Levant. Camb. Archaeological. Journal. 2011, 21(01), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayle, F.E.; Beerling, D.J.; Gosling, W.D.; Bush, M.B. Responses of Amazonia Ecosystems to Climatic and Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Changes Since the Last Glacial Maximum. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 2004, 559, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C. N. H.; Bush, M. B.; Jiménez, J. C.; Gosling, W. D. Past human-induced ecological legacies as a driver of modern Amazonian resilience. People and Nature 2023, 5, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcote-Ríos, G.; Aceituno, F.J.; Iriarte, J.; Robinson, M.; Chaparro-Cárdenas, J.L. 2021.

- Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa. Quaternary International 578, 5–19. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M. N.; Heijink, B. M.; Bush, M. B.; Gosling, W. D.; McMichael, C. N. H. Early to Mid-Holocene Human Activity Exerted Gradual Influences on Amazonian Forest Vegetation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B3772020049820200498 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, W.; Nacimento, I.A. Crossostra Rhizophorae (GUILDING) and C. Brasiliana (Lamarck) in South and Central America. In Estuarine and Marine Bivalve Mollusk Culture, (January 1991); 2019; pp. 125–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odonne, G.; van den Bel, M.; Burst, O.; Brunaux, M.; Bruno, E.; Dambrine, D.; Davy, M.; Desprez, J.; Engel, B.; Ferry, V.; Freycon, P.; Grenand, S.; Jeremie, M.; Mestre, J.-F.; Molino, P.; Petronelli, D.; Sabatier; Herault, B. Long-term influence of Early Human Occupations on Current Forests of the Guiana Shield. Ecology 2019, 100(10), 02806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessanda, L.C.R; Aravena, R.; Melfi, A.J; Telles, E.C.C.; Boulet, R; Valencia, E.P.E; Mario, T. The Use of Carbon Isotopes (13C, 14C) in Soil to Evaluate Vegetation Changes During the Holocene in Central Brazil. Radiocarbon 1996, 38(2), 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestle, W.J.; Laguer-Díaz, C.; Schneider, M. Jesse; Cardon, M.; Sherman, C.E.; Koski-Karell, D. Shellfish Collection Practices of the First Inhabitants of Southwestern Puerto Rico: The Effects of Site Type and Paleoenvironment on Habitat Choice. Latin American Antiquity 2021, 32(45), 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, D. R. The Origins of Plant Cultivation and Domestication in the New World Tropics: Patterns, Process, and New Developments. Current Anthropology 2011, 52(S4), S453–S470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plew, M. G.; Daggers, L.B. The Archaeology of Guyana, Second Edition; University of Guyana Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Plew, M. G.; Pereira, G.; Simon, G. Archaeological Survey and Test Excavations of the Kabakaburi Shell Mound, Northwestern Guyana. In Monographs in Archaeology No. 1; University of Guyana, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Plew, M.G.; Willson, C.; Daggers, L.B. Archaeological Excavations of Siriki Shell Mound Northwest Guyana. In Monographs in Archaeology No 4; Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology and Boise State University of Guyana, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Plew, M. G.; Daggers, L.B. Archaeological Test Excavations at Siriki Shell Mound, Northwest Guyana. In Monographs in Archaeology No. 5; University of Guyana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plew, M. G. The Archaeology of the Piraka Shell Mound. Archaeology and Anthropology 2016, 30(1), 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Plew, M. G.; Willson, C. Archaeological Test Excavations at Wyva Creek Northwestern Guyana. In Monographs in Archaeology No. 3; University of Guyana, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rick, T.C. Shell Midden Archaeology: Current Trends and Future Directions. J Archaeol Res 2004, 32, 309–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeleveld, W. Pollen Analysis in the Young Coastal Plain of Suriname. Geologie en Mijnbouw 1969, 48(2), 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rull, V. Paleoclimatology and Sea-Level History in Venezuela. New Data, Land-Sea Correlations, and Proposals for Future Studies in the Framework of the IGBP-Pages Project. Interciencia 1999, 24(2), 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Shearn, I.; Heckenberger, M.; Simon, G. Ceramic innovation at Dublay: An early agricultural village in the Middle Berbice, Guyana. Archaeology and Anthropology 21 2017, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L. C. R.; Corrêa, R. S.; Wright, J. L.; Macedo, R. S. A new hypothesis for the origin of Amazonian Dark Earths. Nature Communications 12 2021, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpson, A.; Colledge, S.; Crema, E.; Edinborough, K.; Kerig, T.; Manning, K.; Thomas, M.G.; Shennan, S. Reconstructing Regional Population Fluctuations in the European Neolithic Using Radiocarbon Dates: A New Case-study Using an Improved Method. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 52, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toso, A.; Hallingstad, E.; McGrath, K.; Fossile, T.; Conlan, C.; Ferreirs, J.; Bandeira, D. da R.; Giannini, C.F.P.; Gilson, S.; Bueno, L.; Bastos, Q. R. M.; Borda, M. F.; do Santos, M.p.A.; Colonese, C. A. Fishing Intensification as Response to Late Holocene Socio-ecological Instability in Southeastern South America. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 23506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, C.1. Paléoincendies naturels, feux anthropiques et environnements forestiers de Guyane Française du tardig- laciaire á l’holocène récent: approaches chronologique et anthracologique. PhD dissertation, Université Mont- pellier II, Montpellier, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hammen, T. A Palynological Study of the Quaternary of British Guiana. Leidse Geologishe Mededelingen 1963, 29, 125–180. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hammen, T. Paleoecology of Tropical South America. In Biological Diversification in the Tropics; Pranc, G.T., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, 1982; pp. 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hammen, T.; Wijmstra, T.A. A Palynological Study on the Teitary and Upper Cretaceous of British Guiana. Leidse Geologische Mededelingen 1964. Dell 30-1964- BIZ 183-241. [Google Scholar]

- Van Andel, T. Non-timber forest products of the North-West District of Guyana, part II (field guide). In Tropenbos-Guyana Series 8b, Tropenbos-Guyana progranne; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Woodbridge, J.; Fyfe, R.M.; Roberts, N.; Downey, S.; Edinborough, K.; Shennan, S. The impact of the Neolithic Agricultural Transition in Britain: A comparison of pollen-based land-cover and archaeological 14 C Date-inferred Population change. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 51, 216e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. Excavation of the Barabina Shell Mound, Northwest District: An Interim Report. Archaeology and Anthropology 1981, 2(2), 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. Prehistoric Guiana; Ian Randle Publishers: Kingston, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. Some Subsistence Implications of Holocene Climatic Change in Northwestern Guyana. Archaeology and Anthropology 1982, 5(2), 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Witteveen, N. H.; White, C.; Sánchez-Martínez, B. A.; Philip, A.; Boyd, F.; Booij, R.; Christ, R.; van der Hoek, Y. Pre-contact and post-colonial ecological legacies shape Surinamese rainforests. Ecology 2024, 105(5), e4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).