Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

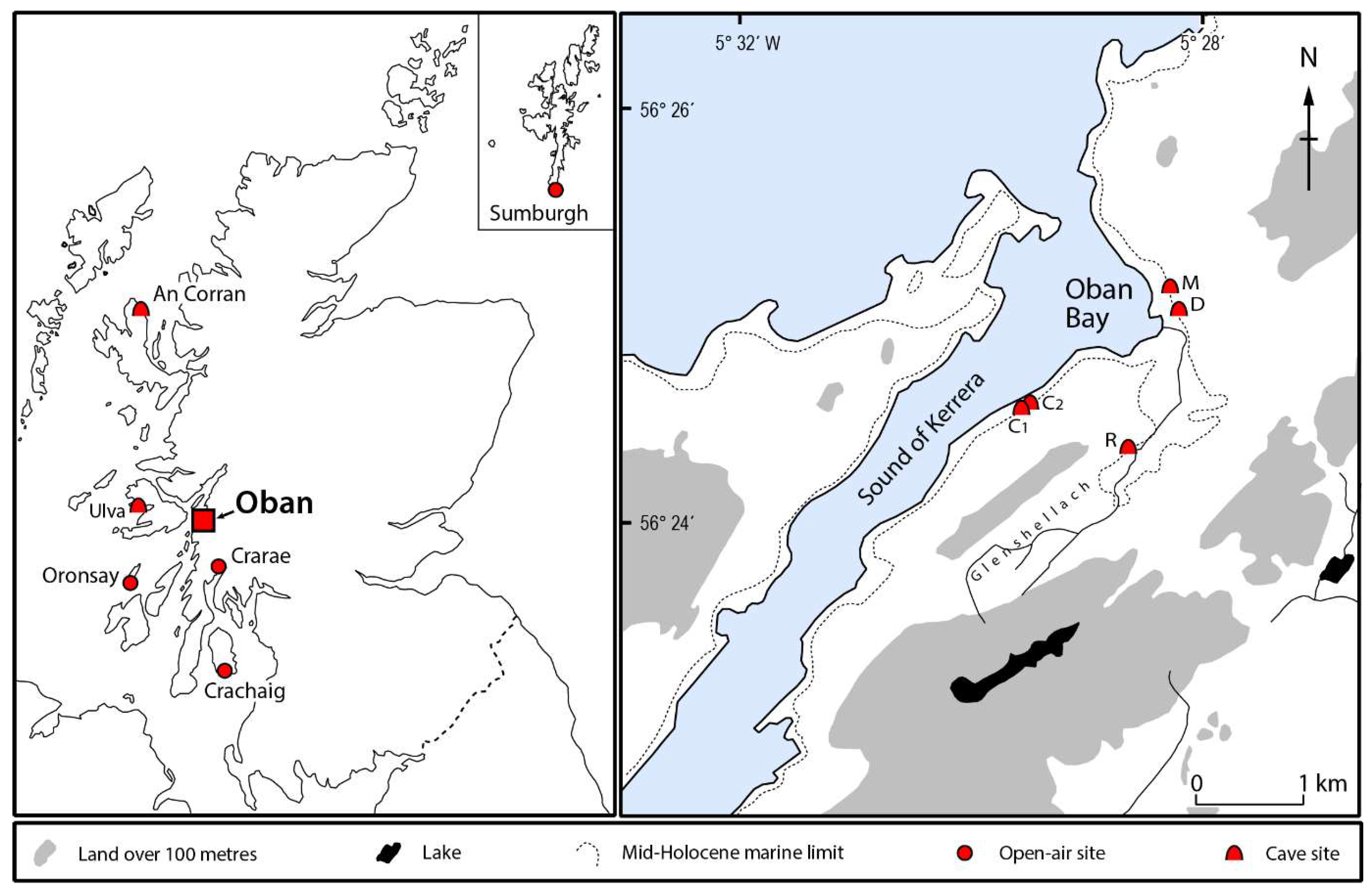

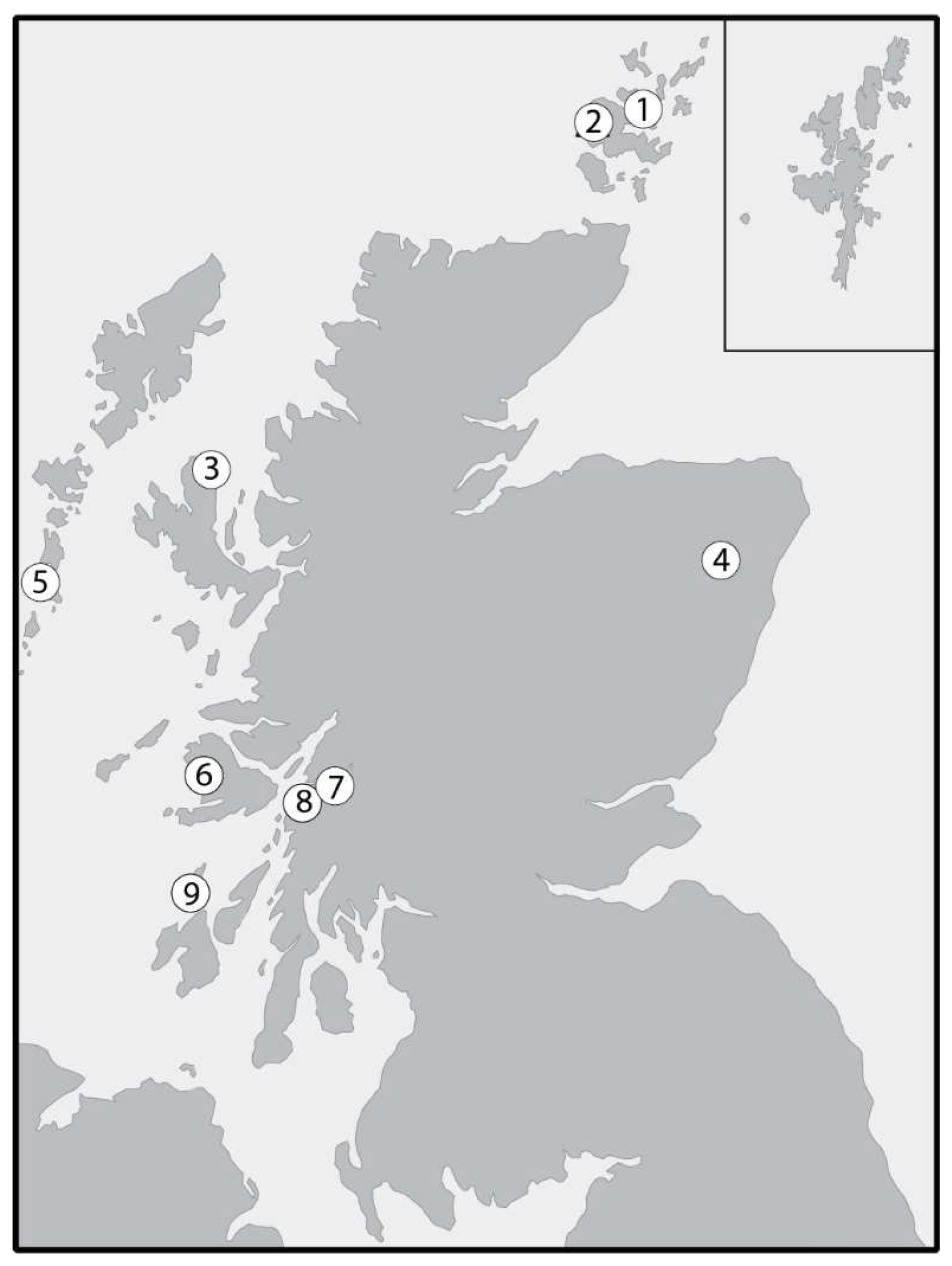

2. Archaeological and Archaeogenetic Background

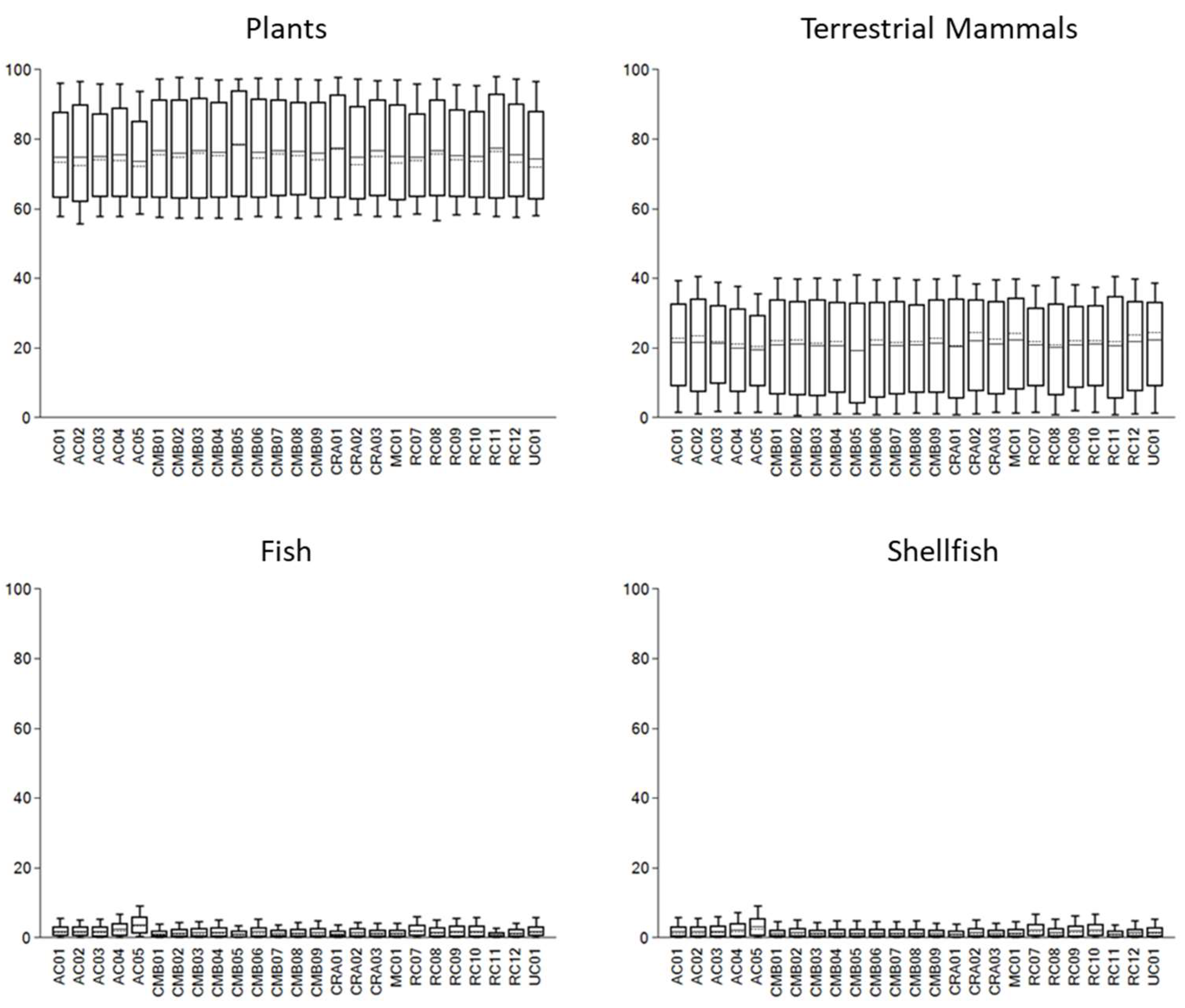

3. Stable Isotope Analysis

- The Δ15Ndiet-consumer diet consumer offset used, i.e., +5.5±0.5‰

- The Δ13Cdiet-consumer offset used, i.e., +1.0‰

- The inclusion of marine foods in the dietary model

- The omission of plant foods from the model

- Whether the faunal samples used to establish food source isotope values were contemporaneous with the human remains from the site.

4. Discussion

4.1. Revised dietary models

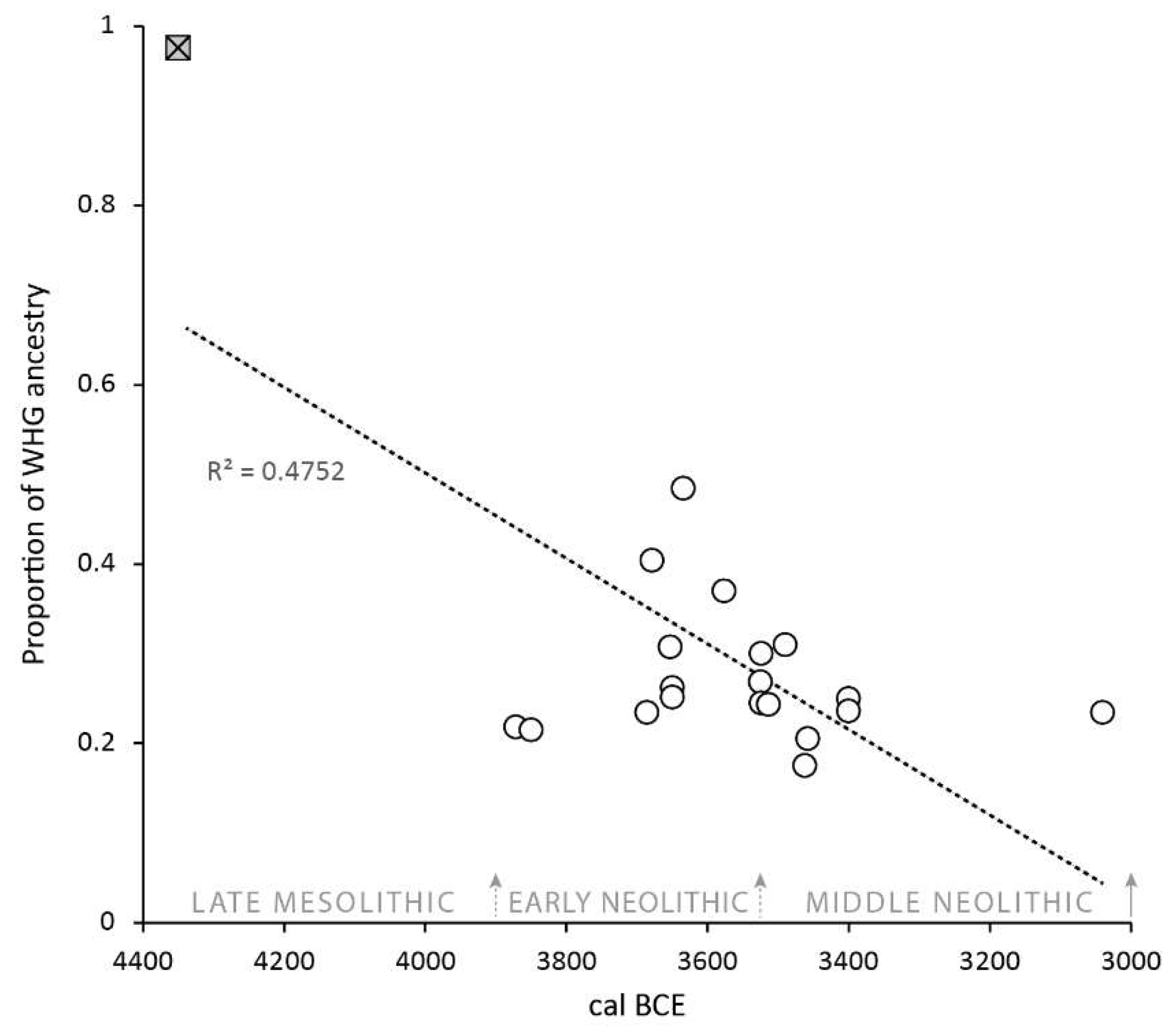

4.2. Diet, DNA and the Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition

4.3. Shell middens and Neolithic burials

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Methods Statement for Extraction and Stable Isotope Analysis of Bone Collagen

Methods Statement for Pre-Treatment and Stable Isotope Analysis of Carbonised Hazelnut Shells

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammerman, A. The Neolithic transition in Europe at 50 years. arXiv:2012.11713 [q-bio.PE], 2020. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. Notice of a cave recently discovered at Oban, containing human remains, and a refuse-heap of shells and bones of animals, and stone and bone implements. Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 1895, 29, 211–230. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.H.; Orton, D.; Johnstone, C.; Harland, J.; Van Neer, W.; Ervynck, A.; Roberts, C.; Locker, A.; Amundsen, C.; Bødker Enghoff, I.; Hamilton-Dyer, S.; Heinrich, D.; Hufthammer, A.K.; Jones, A.K.G.; Jonsson, L.; Makowiecki, D.; Pope, P.; O’Connell, T.C.; de Roo, T.; Richards, M. Interpreting the expansion of sea fishing in medieval Europe using stable isotope analysis of archaeological cod bones. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 1516–1524. [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, L.; Zapata, L.; Bonsall, C. A tale of two shell middens: the natural versus the cultural in ‘Obanian’ deposits at Carding Mill Bay, Oban, western Scotland. In Integrating Zooarchaeology and Paleoethnobotany: A Consideration of Issues, Methods, and Cases; VanDerwarker, A., Peres, T., Eds; Springer: New York, U.S.A., 2010; pp. 205–225.

- Bergsvik, K.A.; Ritchie, K. Mesolithic fishing landscapes in western Norway. In Coastal Landscapes of the Mesolithic. Human Engagement with the Coast from the Atlantic to the Baltic Sea; Schülke, A., Ed.; Routledge, London, U.K., 2020; pp. 229–263.

- Berryman, C.E.; Lieberman, H.R.; Fulgoni, V.L.; Pasiakos, S.M. Protein intake trends and conformity with the dietary reference intakes in the United States: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2014. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 405–413. [CrossRef]

- Bickle, P. Stable isotopes and dynamic diets: The Mesolithic-Neolithic dietary transition in terrestrial Central Europe. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep., 2018, 22, 444-451. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.; Church, M.; Rowley-Conwy, P. Cereals, fruits and nuts in the Scottish Neolithic. Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 2010, 139, 47–103. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.; Church, M.; Rowley-Conwy, P. Seeds, fruits and nuts in the Scottish Mesolithic. Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., 2014, 143, 9–17. http://journals.socantscot.org/index.php/psas/article/view/9799.

- Bishop, R.; Gröcke, D.R.; Ralston, I.; Clarke, D.; Lee, D.H.J.; Shepherd, A.; Thomas, A.S.; Rowley-Conwy, P.A.; Church, M.J. Scotland’s first farmers: New insights into early farming practices in North-west Europe. Antiq., 2022, 96, 1087–1104. [CrossRef]

- Bocherens, H. Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe. Quat. Sci. Rev., 2015, 117, 42–71. [CrossRef]

- Bocherens, H., Drucker, D. Trophic level isotopic enrichment of carbon and nitrogen in bone collagen: Case studies from recent and ancient terrestrial ecosystems. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol., 2003, 13, 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Bollongino, R.; Nehlich, O.; Richards, M.P.; Orschiedt, J.; Thomas, M.G.; Sell, C.; Fajkošová, Z.; Powell, A.; Burger, J. Years of parallel societies in Stone Age Central Europe. Science 2000, 342, 479–481. [CrossRef]

- Bonsall, C.; Smith, C. Late Palaeolithic and Mesolithic bone and antler artifacts from Britain: first reactions to accelerator dates. Mesolithic Miscellany 1989, 10(1), 33–38.

- Bonsall, C.; Smith, C. New AMS 14C dates for antler and bone artifacts from Great Britain. Mesolithic Miscellany 1992, 13(1), 28–34.

- Bonsall, C.; Anderson, D.; Macklin, M. The Mesolithic–Neolithic transition in western Scotland and its European context. Doc. Praehistor. 2002, 29, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Bonsall, C.; Pickard. C.; Ritchie, G. From Assynt to Oban: Some observations on prehistoric cave use in western Scotland. In Caves in Context: The Cultural Significance of Caves and Rockshelters in Europe; Bergsvik, K.A., Skeates, R., Eds; Oxbow Books, Oxford, U.K., 2012; pp. 10–21.

- Bownes, J. Reassessing the Scottish Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition: Questions of Diet and Chronology. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow 2018; https://theses.gla.ac.uk/8911/.

- Bownes, J.M.; Ascough, P.L.; Cook, G.T.; Murray, I.; Bonsall, C. Using stable isotopes and a Bayesian mixing model (FRUITS) to investigate diet at the Early Neolithic site of Carding Mill Bay, Scotland. Radiocarbon 2017, 59, 1275–1294. [CrossRef]

- Brace, S., Booth, T.J. The genetics of the inhabitants of Neolithic Britain: A review. In Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic, Relations and Descent, Whittle, A., Pollard, J., Greaney, S. Eds.; Oxbow Books, Oxford. U.K. 2023; pp. 123–146.

- Brace, S.; Diekmann, Y.; Booth, T.J.; et al. Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 765–771. [CrossRef]

- Bronk Ramsey, C. OxCal 4.4 Online. 2021. Available online: https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/oxcal/OxCal.html (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Brunel, S; Bennett, E.A.; Cardin, L.; Pruvost, M. Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history. PNAS 2020, 117, 12791–12798. [CrossRef]

- Caut, S.; Angulo, E.; Courchamp, F. Variation in discrimination factors (Δ15N and Δ13C): the effect of diet isotopic values and applications for diet reconstruction. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 443–453. [CrossRef]

- Charlton, S.; Alexander, M.; Collins, M.; Milner, N.; Mellars, P.; O'Connell, T.C.; Stevens, R.E.; Craig, O.E. Finding Britain's last hunter-gatherers: A new biomolecular approach to ‘unidentifiable’ bone fragments utilising bone collagen. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2016, 73, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Szpak, P. Interpreting past human diets using stable isotope mixing models—best practices for data acquisition. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2022, 29, 138–161. [CrossRef]

- Connock, K.D.; Finlayson, B.; Mills, A.C.M.; Boardman, S.J.; Crone, B.A.; Hamilton-Dyer, S.; McCormick, F.; Lorimer, D.H.; Morton, A.; Russell, N.J.; Carter, S. Excavation of a shell midden site at Carding Mill Bay near Oban, Scotland. Glasgow Archaeol. J. 1991, 17, 25–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27923592.

- Cramp, L.J.E.; Jones, J.; Sheridan, A.; Smyth, J.; Whelton, H.; Mulville, J; Sharples, N.; Evershed, R.P. Immediate replacement of fishing with dairying by the earliest farmers of the northeast Atlantic archipelagos. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B, Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20132372. [CrossRef]

- Fairweather, A.D.; Ralston, I.B.M. The Neolithic timber hall at Balbridie, Grampian Region, Scotland: the building, the date, the plant macrofossils. Antiq. 1993, 67, 313–323. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.M.; Strapagiel, D.; Borówka, P.; Marciniak, B.; Żądzińska, E; Sirak, K.; Siska, V.; Grygiel, R.; Carlsson, J.; Manica, A.; Lorkiewicz, W.; Pinhasi, R. A genomic Neolithic time transect of hunter-farmer admixture in central Poland. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Grootes, P.M.; Nadeau, M-J.; Nehlich, O. Quantitative diet reconstruction of a Neolithic population using a Bayesian mixing model (FRUITS): The case study of Ostorf (Germany). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2015, 158, 325–340. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Millard, A.R.; Brabec, M.; Nadeau, M-J.; Grootes, P. Food Reconstruction Using Isotopic Transferred Signals (FRUITS): A Bayesian model for diet reconstruction. PLoS ONE 2014, 9(2), e87436. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Nadeau M-J.; Grootes, P.M. Macronutrient-based model for dietary carbon routing in bone collagen and bioapatite. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2012, 4, 291–301. [CrossRef]

- Fornander, E. Consuming and communicating identities. Dietary diversity and interaction in Middle Neolithic Sweden. Theses and Papers in Scientific Archaeology 2011, 12. Stockholm University. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:439410/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Fort, J. Synthesis between demic and cultural diffusion in the Neolithic transition in Europe. PNAS 2012, 109, 18669-18673. [CrossRef]

- Fry, B. Alternative approaches for solving underdetermined isotope mixing problems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2013, 472, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- García-Escárzaga, A.; Gutiérrez-Zugasti, I. The role of shellfish in human subsistence during the Mesolithic of Atlantic Europe: An approach from meat yield estimations. Quat. Int. 2021, 584, 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Groom, P.; Pickard, C.; Bonsall, C. Early Holocene sea fishing in western Scotland: An experimental study. JICA 2019, 14, 426-450. [CrossRef]

- Haak, W.; Balanovsky, O.; Sanchez, J.J.; Koshel, S.; Zaporozhchenko, V.; Adler, C.J.; et al., Ancient DNA from European Early Neolithic farmers reveals their Near Eastern affinities. PLoS Biol 2010, 8(11): e1000536. [CrossRef]

- Halffman, C.M.; Potter, B.A.; McKinney, H.J.; Tsutaya, T.; Finney, B.P.; Kemp, B.M.; Bartelink, E.J.; Wooller, M.J.; Buckley, M.; Clark, C.T.; Johnson, J.J.; Bingham, B.L.; Lanoё, B.; Sattler, R.A.; Reuther, J.D. Ancient Beringian paleodiets revealed through multiproxy stable isotope analyses. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, 36. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abc1968.

- Hare, P.E.; Fogel, M.L.; Stafford, T.W.; Mitchell, A.D.; Hoering. T.C. The isotopic composition of carbon and nitrogen in individual amino acids isolated from modern and fossil proteins. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1991, 18, 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Hedges, R.E.M.; Reynard, L.M. Nitrogen isotopes and the trophic level of humans in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 1240–1251. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, G.V.; Farley, S.D.; Robbins, C.T.; Hanley, T.A.; Titus, K.; Servheen, C. Use of stable isotopes to determine diets of living and extinct bears. Can. J. Zool. 1996, 74: 2080–2088. [CrossRef]

- Jørkov, M.L.S.; Heinemeier, J.; Lynnerup, N. The petrous bone—A new sampling site for identifying early dietary patterns in stable isotopic studies. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2009, 138, 199–209. [CrossRef]

- Keeling, R.F.; Graven, H.D.; Welp, L.R.; Meijer, H.A.J. Atmospheric evidence for a global secular increase in carbon isotopic discrimination of land photosynthesis. PNAS 2017, 114, 10361–10366. [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.; Sheridan, A.; Skoglund, P.; Booth, T.; Brown, L.; Reich, D.; Armit, I.; Bonsall, C.; Anastasiadou, K.; Boyle, A.; Büster, L.S.; Oswald, M.; Carver, H.; Gilardet, A.; Kelly, M.; McCabe, J.; Montgomery, J.; Pickard, C.; Rhodes, D.; Silva, M.; Spall, C.; Williams, M. A summary round-up list of Scottish archaeological human remains that have been sampled/analysed for DNA between January 2019 and November 2021. DES 2021, 21, 201.

- Lipson, M.; Szécsényi-Nagy, A.; Mallick, S.; Pósa, A.; Stégmár, B.; Keerl, V.; Rohland, N.; Stewardson, K.; Ferry, M.; Michel, M.; et al. Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers. Nature 2017, 551, 368–372. [CrossRef]

- Mathieson I, Lazaridis I, Rohland N, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 2015, 528, 499–503. [CrossRef]

- Milner, N.; Craig, O.E. Mysteries of the middens: change and continuity across the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition. In Allen MJ, Sharples N, O'Connor T, (eds) Land and People. Papers in Honour of John G. Evans. Prehistoric Society Research Paper No. 2. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 169–180.

- Milner N, Craig OE, 2012. Isotope analyses. An Corran, Staffin, Skye: A rockshelter with Mesolithic and later occupation; Saville, A., Hardy, K., Miket, R., Ballin, T.B. SAIR 2009, 51, pp. 77–79. [CrossRef]

- Minagawa, M.; Wada, E. Stepwise enrichment of 15N along food chains: Further evidence and the relation between δ15N and animal age. GCA 1984, 48, 1135–1140. [CrossRef]

- Mithen, S. How long was the Mesolithic–Neolithic overlap in western Scotland? Evidence from the 4th millennium BC on the Isle of Islay and the evaluation of three scenarios for Mesolithic–Neolithic interaction. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 2022, 88, 53–77. [CrossRef]

- Mithen, S.; Pirie, A.; Smith, S.; Wicks, K. The Mesolithic–Neolithic transition in western Scotland: A review and new evidence from Tiree. In Whittle A, Cummings V, (eds) Going Over: The Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition in North-West Europe. Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K., 2007; pp. 511–541.

- Montgomery, J.; Beaumont, J.; Jay, M.; Keefe, K.; Gledhill, A.R.; Cook, G.T.; Dockrill, S.J., Melton, N.D. Strategic and sporadic marine consumption at the onset of the Neolithic: Increasing temporal resolution in the isotope evidence. Antiquity 2013, 87, 1060–1072. [CrossRef]

- Newsome, S.D.; Phillips, D.L.; Culleton, B.J.; Guilderson, T.P.; Koch, P.L. Dietary reconstruction of an Early to Middle Holocene human population from the central California coast: Insights from advanced stable isotope mixing models. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2004, 31: 1101e1115. [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, T.C.; Kneale, C.J.; Tasevska, N.; Kuhnle, G.G.C. The diet-body offset in human nitrogen isotopic values: A controlled dietary study. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 149, 426–434. [CrossRef]

- Olalde, I.; Brace, S.; Allentoft, M.E.; Armit, I.; Kristiansen, K.; Booth, T.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Szécsényi-Nagy, A.; Mittnik, A.; et al. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of Northwest Europe. Nature 2018, 555, 190–196.

- Olalde, I.; Mallick, S.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Villalba-Mouco, V.; Silva, M.; Dulias, K.; Edwards, C.J.; et al. The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years. Science 2019, 363, 1230–1234. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aav4040.

- Parnell, A.C.; Inger, R.; Bearhop, S.; Jackson, A.L. Source partitioning using stable isotopes: Coping with too much variation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5(3), e9672. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, N.; Isakov, M.; Booth, T.; Büster, L.; Fischer, C-E.; Olalde, I.; Ringbauer, H.; Akbari, A.; Cheronet, O.; Bleasdale, M.; et al. Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age. Nature 2022, 601, 588–594. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R. Neolithic cave burials. Agency, Structure and Environment. Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.L.; Koch, P.L. Incorporating concentration dependence in stable isotope mixing models. Oecologia 2002,130, 114–125. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.L.; Inger, R.; Bearhop, S.; Jackson, A.L.; Moore, J.W.; Parnell, A.C.; Semmens, B.X.;, Ward, E.J. Best practices for use of stable isotope mixing models in food-web studies. Can. J. Zool. 2014, 92, 823–835. [CrossRef]

- Pickard, C.; Bonsall, C. Post-glacial hunter-gatherer subsistence patterns in Britain: Dietary reconstruction using FRUITS. Anthropol. Archaeol. Sci. 2020, 12, 142. [CrossRef]

- Pickard C.; Bonsall C. 2022. Reassessing Neolithic diets in western Scotland. Humans 2022, 2, 226–250. [CrossRef]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Jankauskas, R.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Dupras, T. Reconstructing Subneolithic and Neolithic diets of the inhabitants of the SE Baltic coast (3100–2500 cal BC) using stable isotope analysis. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2017, 9, 1421–1437. [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 2002, 83, 703–718. [CrossRef]

- Reimer, P.; Austin, W.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.; Friedrich, M.; et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757.

- Richards, M.; Hedges, R.E.M. Stable isotope evidence for similarities in the types of marine foods used by Late Mesolithic humans at sites along the Atlantic coast of Europe. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1999, 26, 717–722. [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Mellars, P. Stable isotopes and the seasonality of the Oronsay middens. Antiquity 1998, 72, 178–184. [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Schulting, R.; Hedges, R. Sharp shift in diet at onset of Neolithic. Nature 2003, 425, 366. [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.P.; Schulting, R. Touch not the Fish: The Mesolithic–Neolithic change of diet and its significance. Antiquity 2006, 80, 444-456. [CrossRef]

- Rivero, D.G.; Taylor, R.; Umbelino, C.; Cubas, M.; Barrera Cruz, M.; Díaz Rodríguez, M.J. Early Neolithic ritual funerary behaviours in the western-most regions of the Mediterranean: New insights from Dehesilla Cave (southern Iberian Peninsula). Doc. Praehistor. 2021, 48, 298–327. [CrossRef]

- Rivollat, M.; Jeong, C.; Schiffels, S.; Küçükkalıpçı, İ.; Pemonge, M.H.; Rohrlach, A.B.; Alt, K.W.; Binder, D.; Friederich, S.; Ghesquière, E.; et al. Ancient genome-wide DNA from France highlights the complexity of interactions between Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz5344. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, C.T.; Hilderbrand, G.V.; Farley, S.D. Incorporating concentration dependence in stable isotope mixing models: A response to Phillips and Koch (2002). Oecologia 2002, 133, 10–13. [CrossRef]

- Russell, N.; Bonsall, C.; Sutherland, D.G. The role of shellfish-gathering in the Mesolithic of western Scotland: the evidence from Ulva Cave, Inner Hebrides. In Man and Sea in the Mesolithic. Coastal Settlement Above and Below the Present Sea Level; Fischer, A., Ed.; Oxbow Books, Oxford, U.K., 1995; pp. 273–288.

- Saville, A.; Hardy, K.; Miket, R.; Ballin, T.B. 2012. An Corran, Staffin, Skye: A Rockshelter with Mesolithic and Later Occupation. Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports 2012, 51. [CrossRef]

- Sayle, K.L.; Brodie, C.R.; Cook, G.T.; Hamilton, W.D. 2019. Sequential measurement of δ15N, δ13C and δ34S values in archaeological bone collagen at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC): a new analytical frontier. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 33, 1258–1266. [CrossRef]

- Schier, W. Modes and models of neolithization in Europe: Comments to an ongoing debate. In 6000 BC: Transformation and Change in the Near East and Europe; Biehl, P.F.; Rosenstock, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 372–392.

- Schulting, R.J. Slighting the sea: Stable isotope evidence for the transition to farming in northwestern Europe. Doc. Praehistor. 1998, 25, 203–218.

- Schulting, R.J.; Borić, D. A tale of two processes of Neolithisation: Southeast Europe and Britain/Ireland. In The Neolithic of Europe: Papers in Honour of Alasdair Whittle; Bickle, P.; Cummings, V.; Hofmann, D.; Pollard, J., Eds.; Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 82–106.

- Schulting, R.J.; MacDonald, R.; Richards, M.P. FRUITS of the sea? A cautionary tale regarding Bayesian modelling of palaeodiets using stable isotope data. Quat. Int. 2023, 650, 52-61. [CrossRef]

- Schulting, R.J.; Richards, M.P. 2002 The wet, the wild and the domesticated: The Mesolithic–Neolithic transition on the west coast of Scotland. Eur. J. Archaeol. 2002, 5, 147–189. [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, H.P. Some theoretical aspects of isotope paleodiet studies. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1991, 18, 261–275. [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.G. The excavation of the chambered cairn at Crarae, Loch Fyneside, Mid Argyll. Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 1963, 94, 1–27.

- Sheridan, A. The Neolithization of Britain and Ireland: The ‘Big Picture’. In Landscapes in Transition; Finlayson, B.; Warren, G. Eds.; Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 89–105.

- Sheridan, A. Contextualising Kilmartin: Building a narrative for developments in western Scotland and beyond, from the Early Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age. In Image, Memory and Monumentality, Jones, A.M., Pollard, J., Allen, M.J., Gardiner, J., Eds; Prehistoric Society Research Paper No. 5, Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 163–183.

- Sheridan, J.A.; Schulting, R.J. Making sense of Scottish Neolithic funerary monuments: tracing trajectories and understanding their rationale. In Monumentalising life in the Neolithic: Narratives of change and continuity, Gebauer, A.B., Sørensen, L., Teather, A., Valera, A.C., Eds.; Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 195–215.

- Sheridan, A.; Whittle, A. aDNA and modelling the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition in Britain and Ireland. In Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic, Relations and Descent; Whittle, A., Pollard, J., Greaney, S., Eds; Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK; pp. 169–182.

- Silvestri, L.; Achino, K.F.; Gatta, M., Rolfo, M.F.; Salari L. Grotta Mora Cavorso: Physical, material and symbolic boundaries of life and death practices in a Neolithic cave of central Italy. Quat. Int. 2020, 539, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Sparacello, V.S.; Varalli, A.; Rossi, S.; Panelli, C.; Goude, G.; Palstra, S.W.L.; Conventi, M.; Del Lucchese, A.; Arobba, D.; De Pascale, A.; et al. Dating the funerary use of caves in Liguria (northwestern Italy) from the Neolithic to historic times: Results from a large-scale AMS campaign on human skeletal series. Quat. Int. 2020, 536: 30–44. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Fuller, D.Q. Did Neolithic farming fail? The case for a Bronze Age agricultural revolution in the British Isles. Antiquity 2012, 86, 707–722. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Fuller, D.Q. Alternative strategies to agriculture: The evidence for climatic shocks and cereal declines during the British Neolithic and Bronze Age (a reply to Bishop). World Archaeology 2015, 47, 856–875. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Crema, E.R.; Shoda, S. The importance of wild resources as a reflection of the resilience and changing nature of early agricultural systems in East Asia and Europe. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Tauber, H. 13C evidence for dietary habits of prehistoric man in Denmark. Nature 1981, 292, 332–333. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J. Rethinking the Neolithic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1991.

- Thomas, J. Recent debates on the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition in Britain and Ireland. Doc. Praehistor. 2004, 31, 113–130. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J. The Birth of Neolithic Britain: An Interpretive Account. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Turner, W. On human and animal remains found in caves at Oban, Argyllshire. Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 1895, 29: 410–438. [CrossRef]

- Vanderklift, M.A.; Ponsard, S. Sources of variation in consumer-diet δ15N enrichment: A meta-analysis. Oecologia 2003, 136, 169–182. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.C.; van der Merwe, N.J. Isotopic evidence for early maize cultivation in New York State. Am Antiq. 1977, 42, 238–242. https://www.jstor.org/stable/278984.

- Zerjal, T.; Xue, Y.; Bertorelle, G.; Wells, R.S.; Bao, W.; Zhu, S.; Qamar, R.; Ayub, Q.; Mohyuddin, A.; Fu, S.; et al. The genetic legacy of the Mongols. AJHG 2003, 72, 717–721. [CrossRef]

- Zilhão, J. Time is on my side. In Dynamics of Neolithisation in Europe. Studies in Honour of Andrew Sherratt, Hadjikoumis, A., Robinson, E., Viner, S. Eds.; Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 46–65.

- Zvelebil, M.; Rowley-Conwy, P. Transition to farming in Northern Europe: A hunter-gatherer perspective. Nor. Archaeol. Rev. 1984, 17, 104–128. [CrossRef]

| Site | ID | Sex | Date type | Lab Code | 14C (BP) | Calendar years (cal BCE/BCE) | Median (cal BCE/BCE) | Ancestry |

| MacArthur Cave | I2657 | M | 14C | SUERC-68701 | 5052±30 | 3960-3770 | 3872 | Farmer |

| MacArthur Cave | I2658 | M | Contextual | n/a | n/a | 4000-3700 | 3850 | Farmer |

| Distillery Cave | I2659 | F | 14C | SUERC-68702 | 4914±27 | 3770-3640 | 3686 | Farmer |

| Ulva Cave | I12312 | M | 14C | PSUAMS-5771 | 4895±25 | 3760-3630 | 3679 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Distillery Cave | I2691 | M | 14C | SUERC-68704 | 4881±25 | 3710-3630 | 3653 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Raschoille Cave | I5370 | F | Contextual | n/a | n/a | 4000-3300 | 3650 | Farmer |

| Raschoille Cave | I5371 | F | Contextual | n/a | n/a | 4000-3300 | 3650 | Farmer |

| Carding Mill Bay 2 | I12314 | F | 14C | PSUAMS-5772 PSUAMS-5773 PSUAMS-5774 PSUAMS-5776 |

4832±14 | 3650-3530 | 3634 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3135 | M | 14C | PSUAMS-2068 | 4770±30 | 3640-3380 | 3576 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Carding Mill Bay 2 | I12313 | F | Contextual | n/a | n/a | 3700-3350 | 3525 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3134 | M | 14C | PSUAMS-2155 | 4730±25 | 3630-3370 | 3524 | Farmer |

| Carding Mill Bay 2 | I12317 | M | 14C | PSUAMS-5775 | 4725±25 | 3630-3370 | 3524 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3133 | M | 14C | PSUAMS-2154 | 4725±20 | 3630-3370 | 3514 | Farmer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3041 | M | Contextual | n/a | n/a | 3950-3030 | 3490 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3136 | F | 14C | PSUAMS-2069 | 4665±30 | 3520-3370 | 3450 | Farmer |

| Clachaig | I2988 | F | 14C | SUERC-68711 | 4645±29 | 3520-3360 | 3458 | Farmer |

| Distillery Cave | I2660 | M | 14C | SUERC-68703 | 4631±29 | 3520-3350 | 3462 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3137 | M | Contextual | n/a | n/a | 3800-3000 | 3400 | Farmer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3139_d | F | Contextual | n/a | n/a | 3800-3000 | 3400 | Admixed farmer/hunter-gatherer |

| Raschoille Cave | I3138 | F | 14C | PSUAMS-2156 | 4415±25 | 3320-2920 | 3040 | Farmer |

| Parameter | Model | Description |

| Δ15Ndiet-consumer | Both | 4.6±0.5‰ |

| Δ13Cdiet-consumer | Both | 4.8±0.5‰ |

| Manured cereals δ13C and δ15N | Model A | δ13Cprotein = 26±1.0‰ and δ15Nmanured = 5.0±2.0‰ |

| Unmanured cereals δ13C and δ15N | Model B | δ13Cprotein = 26±1.0‰ and δ15Nmanured = 3.0±1.0‰ |

| Terrestrial herbivores δ13C and δ15N | Both | Terrestrial herbivores δ13Cprotein = − 24.7 ± 0.1‰ and δ15N = 3.4 ± 0.1‰ |

| Young herbivores δ13C and δ15N | Both | Young herbivores δ13Cprotein = − 23.7 ± 0.1‰ and δ15N = 5.4 ± 0.1‰ |

| Site | Context | Individual | Terrestrial herbivore | Young herbivore | Cereals | |||

| Mean % | CI (68%) | Mean % | CI (68%) | Mean % | CI (68%) | |||

| CMB 1 | XXIII | OxA-7890 | 24±16 | 7-41 | 18±14 | 5-33 | 58±17 | 41-76 |

| CMB 1 | VII | OxA-7665 | 22±16 | 5-40 | 17±13 | 4-31 | 60±16 | 43-78 |

| CMB 1 | XV | OxA-7664 | 35±22 | 11-58 | 20±15 | 5-36 | 45±21 | 23-68 |

| CMB 1 | XIV | OxA-7663 | 26±19 | 7-46 | 16±13 | 4-29 | 58±19 | 38-77 |

| Site | Context | Individual | Terrestrial herbivore | Young herbivore | Cereals | |||

| Mean % | CI (68%) | Mean % | CI (68%) | Mean % | CI (68%) | |||

| CMB 1 | XXIII | OxA-7890 | 17±14 | 4-31 | 27±16 | 9-44 | 56±17 | 41-76 |

| CMB 1 | VII | OxA-7665 | 17±14 | 4-31 | 23±15 | 4-31 | 60±17 | 43-78 |

| CMB 1 | XV | OxA-7664 | 28±20 | 7-49 | 25±15 | 9-42 | 47±18 | 29-66 |

| CMB 1 | XIV | OxA-7663 | 22±17 | 5-41 | 20±14 | 6-35 | 57±17 | 40-76 |

| Site | Date | Species | Common Name | δ13C ‰ | δ15N ‰ | C:N | Lab/Specimen ID | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TERRESTRIAL MAMMALS | ||||||||

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Bos | Cattle | -22.2 | 1.6 | Milner and Craig 2009 | ||

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Bos | Cattle | -22.0 | 1.7 | Milner and Craig 2009 | ||

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -23.3 | 3.5 | 3.3 | GU39625 (XIV) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -23.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | GU39626 (XIV) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -23.3 | 3.5 | 3.3 | GU39627 (XIV) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -23.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | GU39628 (XIV) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -22.6 | 3.8 | 3.3 | GU39629 (XV) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -23.3 | 4.2 | 3.3 | GU39630 (XV) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -23.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | GU39631 (XV) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Bos taurus (probable) | Cattle | -22.0 | 3.0 | 3.3 | GU39632 (XV) | Bownes 2018 |

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -21.2 | 1.0 | Milner and Craig 2009 | ||

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -22.5 | 2.4 | Milner and Craig 2009 | ||

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -23.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | GUsi3509 (XVII) | Bownes 2018 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -21.9 | 2.0 | CVII:123 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -22.9 | 2.5 | C XVII:4 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | |

| Raschoille Cave | 7640±80 BP | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -21.8 | 2.9 | OxA-8396 | Pickard and Bonsall 2022 | |

| Raschoille Cave | 7575±75 BP | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -21.5 | 2.8 | OxA-8397 | Pickard and Bonsall 2022 | |

| Raschoille Cave | 7480±75 BP | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -21.6 | 2.6 | OxA-8398 | Pickard and Bonsall 2022 | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Cervus elaphus | Red deer | -22.8 | 2.6 | 3.4 | GUsi8894 | this study |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Cervus elaphus/Bos taurus | Red deer/Cattle | -23.2 | 3.7 | 3.3 | GUsi3505 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Cervus elaphus/Bos taurus | Red deer/Cattle | -22.5 | 2.4 | 3.2 | GUsi3506 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Cervus elaphus/Bos taurus | Red deer/Cattle | -23.2 | 2.3 | 3.2 | GUsi3508 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Cervus elaphus/Bos taurus | Red deer/Cattle | -22.8 | 3.9 | 3.2 | GUsi3511 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -21.6 | 3.5 | 3.2 | GUsi3497 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -22.9 | 3.7 | 3.2 | GUsi3507 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -23.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | GUsi3498 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -22.8 | 2.8 | 3.5 | GUsi3500 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -23.1 | 3.1 | 3.5 | GUsi3501 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -22.8 | 2.8 | 3.6 | GUsi3502 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -22.5 | 2.7 | 3.4 | GUsi3503 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -22.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 | GUsi3504 | Bownes et al. 2017 |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Ovis aries/Capreolus capreolus | Sheep/Roe deer | -22.8 | 2.3 | 3.4 | GUsi8895 | this study |

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Sus | Pig | -22.3 | 2.3 | Milner and Craig 2009 | ||

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Sus | Pig | -22.6 | 3.3 | Milner and Craig 2009 | ||

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Sus | Pig | -21.7 | 4.1 | Milner and Craig 2009 | ||

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Neolithic | Sus | Pig | -21.9 | 3.2 | C XXIV:2 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | |

| Cnoc Coig | Mesolithic | Sus | Pig | -21.2 | 4.3 | Charlton et al. 2016 | ||

| Cnoc Coig | Mesolithic | Sus | Pig | -21.0 | 4.6 | Charlton et al. 2016 | ||

| Cnoc Coig | Mesolithic | Sus | Pig | -18.8 | 10.2 | Charlton et al. 2016 | ||

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Sus | Pig | -21.9 | 6.5 | 3.3 | GUsi8896 | this study |

| MARINE RESOURCES - ARCHAEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS | ||||||||

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Dicentrarchus labrax | Seabass | -12.6 | 13.4 | 3.2 | GUsi8897 | this study |

| An Corran | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Gadus morhua | Cod | -13.6 | 15.3 | 0055-r | Milner and Craig 2012 | |

| Bornish | 12th-13th C. AD | Gadus morhua | Cod | -12.9 | 14.5 | 703 | Barrett et al. 2011 | |

| Bornish | 13th C. AD | Gadus morhua | Cod | -11.3 | 15.4 | 706 | Barrett et al. 2011 | |

| Bornish | 13th C. AD | Gadus morhua | Cod | -13.1 | 13.8 | 708 | Barrett et al. 2011 | |

| Bornish | 12th-13th C. AD | Gadus morhua | Cod | -13.2 | 13.8 | 713 | Barrett et al. 2011 | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Labrus bergylta | Ballan wrasse | -16.0 | 11.8 | 3.4 | GUsi8900 | this study |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Labrus sp. | Wrasse | -12.6 | 14.1 | 3.3 | GUsi8898 | this study |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Labrus sp. | Wrasse | -12.1 | 14.6 | 3.2 | GUsi8902 | this study |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Pollachius virens | Saithe | -12.2 | 13.6 | 3.2 | GUsi8899 | this study |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Pollachius virens | Saithe | -13.4 | 12.1 | 3.2 | GUsi8901 | this study |

| Carding Mill Bay 1 | Mesolithic/Neolithic | Lutra lutra | Otter | -12.0 | 16.0 | C VI:21 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | |

| Caisteal nan Gillean | Mesolithic | Halichoerus grypus | Grey seal | -11.9 | 19.1 | n/a | Richards and Mellars 1998 | |

| Cnoc Coig | Mesolithic | Pinniped | Seal | -11.6 | 18.8 | 10502 | Charlton et al. 2016 | |

| Cnoc Coig | Mesolithic | Pinniped | Seal | -11.8 | 19.5 | 10420 | Charlton et al. 2016 | |

| Airds Bay, Loch Etive | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -14.1 | 6.3 | GUsi3201/3208 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Airds Bay, Loch Etive | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -15.0 | 6.7 | GUsi3202/3209 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Airds Bay, Loch Etive | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -15.1 | 6.3 | GUsi3204/3211 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Airds Bay, Loch Etive | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -15.0 | 7.1 | GUsi3205/3212 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Airds Bay, Loch Etive | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -14.0 | 7.0 | GUsi3206/3213 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Airds Bay, Loch Etive | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -15.2 | 6.7 | GUsi3207/3214 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Oban, Scotland | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -13.6 | 7.8 | GUsi3215/3221 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Oban, Scotland | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -15.5 | 6.9 | GUsi3216/3222 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Oban, Scotland | Modern - flesh | Patella | Limpet | -14.7 | 6.2 | GUsi3217/3223 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Oban, Scotland | Modern - flesh | Littorina | Periwinkle | -15.3 | 11.7 | GUsi3446/3598 | Bownes 2018 | |

| Oban, Scotland | Modern - flesh | Littorina | Periwinkle | -13.3 | 8.5 | GUsi3451/3603 | Bownes 2018 | |

| PLANTS | ||||||||

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -26.0 | 9.3 | UA1 | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -24.9 | 7.4 | UA2 | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -27.2 | 8.0 | UA3 | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -25.6 | 5.6 | UA4 | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -24.6 | 6.2 | UA5 | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -25.1 | 5.7 | UMS1 RW | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -23.9 | 0.9 | UMS2 RW | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -25.0 | -1.2 | UMS3 RW | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -27.9 | -1.0 | UMS4 RW | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -27.0 | 0.5 | UMS5 RW | this study | |

| Ulva Cave | Mesolithic | Corylus avellana | Hazelnut (shell) | -25.0 | 3.4 | UMS6 RW | this study | |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.6 | 0.6 | 24.4 | BB F40 IS.1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.1 | 0.1 | 36.0 | BB F40 IS.2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.5 | 0.8 | 32.0 | BB F40 IS.3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.6 | -1.6 | 37.2 | BB F40 IS.4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.8 | 2.3 | 30.2 | BB F40 IS.5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.8 | 1.4 | 27.0 | BB F40 IS.6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.4 | 1.1 | 25.4 | BB F40 IS.7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.1 | 3.0 | 27.7 | BB F40 IS.8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.2 | 1.4 | 29.3 | BB F40 IS.9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.7 | 1.5 | 27.8 | BB F40 IS.10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.4 | 0.4 | 30.0 | BB F294 IS.32 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.9 | 0.5 | 35.5 | BB F294 IS.33 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.2 | 0.5 | 26.1 | BB F294 IS.34 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.2 | 0.0 | 33.0 | BB F294 IS.35 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.2 | 1.3 | 31.0 | BB F294 IS.36 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.5 | -0.2 | 28.2 | BB F294 IS.37 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.5 | -1.6 | 27.5 | BB F294 IS.38 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.6 | 0.9 | 31.0 | BB F294 IS.39 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.6 | 2.4 | 27.7 | BB F294 IS.40 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.8 | -1.3 | 30.7 | BB F294 IS.41 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -21.6 | 4.0 | 18.8 | SB C.168 IS.1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.0 | 2.5 | 25.9 | SB C.168 IS.2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.7 | 2.5 | 19.5 | SB C.168 IS.3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.1 | 4.0 | 17.7 | SB C.168 IS.4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.7 | 4.1 | 23.3 | SB C.168 IS.5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -21.0 | 3.1 | 12.3 | SB C.168 IS.6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.8 | 2.2 | 21.7 | SB C.168 IS.7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.4 | 5.3 | 17.0 | SB C.168 IS.8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.3 | 4.5 | 26.0 | SB C.168 IS.9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.8 | 3.2 | 19.7 | SB C.168 IS.10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.1 | 7.3 | 17.0 | BOH S.506.8 IS1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.1 | 0.2 | 24.7 | BOH S.506.8 IS2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.0 | 1.1 | 22.7 | BOH S.506.8 IS3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.3 | 1.2 | 27.0 | BOH S.506.8 IS4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.1 | 3.8 | 19.8 | BOH S.506.8 IS5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.3 | 1.5 | 30.8 | BOH S.506.8 IS6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.4 | 3.9 | 17.8 | BOH S.506.8 IS7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.3 | 5.9 | 20.1 | BOH S.506.8 IS8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.3 | 5.9 | 28.7 | BOH S.506.8 IS9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.1 | 3.3 | 18.7 | BOH S.506.8 IS10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.0 | 1.7 | 31.7 | BOH S.124 IS1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.2 | 5.1 | 28.1 | BOH S.124 IS2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.5 | 4.0 | 27.6 | BOH S.124 IS3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.2 | 3.5 | 25.2 | BOH S.124 IS4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.9 | 2.6 | 31.3 | BOH S.124 IS5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.2 | 3.0 | 22.8 | BOH S.124 IS6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.9 | 4.1 | 30.5 | BOH S.124 IS7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.2 | 2.2 | 22.1 | BOH S.124 IS8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.9 | 1.0 | 21.8 | BOH S.124 IS9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.0 | 2.7 | 21.9 | BOH S.124 IS10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.1 | 5.7 | 14.0 | BOH S.168 IS1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.9 | 3.8 | 21.4 | BOH S.168 IS2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.2 | 6.1 | 19.3 | BOH S.168 IS3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.9 | 4.5 | 27.3 | BOH S.168 IS4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.0 | 3.5 | 11.6 | BOH S.168 IS5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.5 | 3.8 | 22.7 | BOH S.168 IS6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.8 | 7.6 | 15.7 | BOH S.168 IS7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.1 | 4.1 | 28.8 | BOH S.168 IS8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.9 | 2.3 | 27.9 | BOH S.168 IS9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.9 | 1.7 | 29.7 | BOH S.168 IS10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.1 | 0.3 | 23.6 | BOH S.24 IS1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.1 | 3.9 | 27.5 | BOH S.24 IS2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.2 | 3.9 | 21.4 | BOH S.24 IS3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.9 | 4.5 | 18.7 | BOH S.24 IS4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.2 | 2.7 | 19.9 | BOH S.24 IS5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.1 | 6.3 | 30.2 | BOH S.24 IS6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.4 | 7.0 | 28.2 | BOH S.24 IS7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.1 | 3.6 | 29.4 | BOH S.24 IS8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.4 | 8.0 | 25.0 | BOH S.24 IS9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.9 | 1.9 | 25.9 | BOH S.24 IS10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.2 | 4.5 | 20.3 | BOH S.41 IS1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.6 | 4.2 | 26.7 | BOH S.41 IS2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.7 | 8.3 | 31.3 | BOH S.41 IS3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.4 | 2.8 | 25.6 | BOH S.41 IS4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.8 | 13.7 | 20.4 | BOH S.41 IS5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.3 | 8.8 | 24.2 | BOH S.41 IS6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.5 | 1.4 | 24.1 | BOH S.41 IS7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.8 | 2.9 | 24.0 | BOH S.41 IS8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.7 | 2.6 | 28.0 | BOH S.41 IS9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.4 | 4.2 | 28.6 | BOH S.41 IS10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.1 | 3.4 | 14.2 | BOH S.112 IS1 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.3 | 1.2 | 32.2 | BOH S.112 IS2 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.0 | 4.7 | 22.0 | BOH S.112 IS3 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.6 | 3.7 | 20.2 | BOH S.112 IS4 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -22.8 | 3.1 | 19.0 | BOH S.112 IS5 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -25.7 | 2.8 | 33.7 | BOH S.112 IS6 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.2 | 2.4 | 22.2 | BOH S.112 IS7 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.5 | 3.1 | 19.9 | BOH S.112 IS8 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -23.3 | 2.9 | 19.6 | BOH S.112 IS9 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Braes of Ha'Breck | Neolithic | Hordeum vulgare | Naked barley | -24.4 | 2.7 | 21.7 | BOH S.112 IS10 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.7 | 1.4 | 28.8 | BB F40 IS.11 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.2 | 0.9 | 27.3 | BB F40 IS.12 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.6 | 1.0 | 23.7 | BB F40 IS.13 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.2 | -0.7 | 24.4 | BB F40 IS.14 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.4 | 0.5 | 26.0 | BB F40 IS.15 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -22.0 | -0.8 | 27.0 | BB F40 IS.16 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.2 | 1.0 | 34.0 | BB F40 IS.17 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.1 | 0.6 | 25.6 | BB F40 IS.18 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.2 | -0.5 | 25.8 | BB F40 IS.19 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.4 | 3.1 | 25.1 | BB F40 IS.20 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.1 | 0.6 | 25.1 | BB F294 IS.42 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.4 | 1.0 | 28.7 | BB F294 IS.43 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -22.7 | 0.8 | 27.1 | BB F294 IS.44 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -24.0 | -0.6 | 27.5 | BB F294 IS.45 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.4 | 0.7 | 24.3 | BB F294 IS.46 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -22.9 | 1.1 | 23.8 | BB F294 IS.47 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -22.6 | 1.4 | 24.4 | BB F294 IS.48 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.7 | -0.6 | 24.8 | BB F294 IS.49 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.5 | -0.2 | 28.0 | BB F294 IS.50 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -23.5 | 1.1 | 22.1 | BB F294 IS.51 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -20.7 | 3.8 | 15.6 | SB C.168 IS.11 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -20.8 | 1.6 | 16.0 | SB C.168 IS.12 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -22.2 | 3.5 | 15.3 | SB C.168 IS.13 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -22.5 | 0.9 | 13.7 | SB C.168 IS.14 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Skara Brae | Neolithic | Triticum dicoccon | Emmer wheat grain | -21.5 | 3.1 | 15.0 | SB C.168 IS.15 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -24.1 | 0.5 | 32.2 | BB F40 IS.21 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.7 | 0.2 | 25.0 | BB F40 IS.22 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.7 | -0.3 | 25.6 | BB F40 IS.23 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -23.1 | 0.1 | 26.8 | BB F40 IS.24 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.9 | 1.2 | 29.0 | BB F40 IS.25 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -23.8 | -0.6 | 25.8 | BB F40 IS.26 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -23.1 | 0.6 | 28.2 | BB F40 IS.27 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -23.5 | 0.2 | 29.6 | BB F40 IS.28 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.8 | -0.7 | 30.8 | BB F40 IS.29 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.4 | 2.0 | 27.9 | BB F40 IS.30 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.5 | 0.8 | 28.4 | BB F294 IS.52 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -23.5 | 0.5 | 30.6 | BB F294 IS.53 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.9 | 0.8 | 21.6 | BB F294 IS.54 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -23.0 | -0.3 | 23.5 | BB F294 IS.55 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.7 | -0.7 | 30.3 | BB F294 IS.56 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.2 | 0.3 | 21.9 | BB F294 IS.57 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.9 | -0.2 | 24.2 | BB F294 IS.58 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.6 | 0.0 | 22.8 | BB F294 IS.59 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -24.5 | 3.7 | 24.1 | BB F294 IS.60 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| Balbridie | Neolithic | Triticum | Free-threshing wheat | -22.9 | 2.3 | 33.8 | BB F294 IS.61 | Bishop et al. 2022 |

| ID | Site | Lab/Context ID | Skeletal element | Sex | Age | δ13C ‰ | δ15N ‰ | C/N | 14C Age BP | References |

| AC.01 | An Corran | Small adult | -20.7 | 9.8 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.02 | An Corran | Mature adult (<35) | -20.6 | 9.8 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.03 | An Corran | Small adult | -20.5 | 9.4 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.04 | An Corran | Mature adult (>40) | -20.2 | 10.2 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.05 | An Corran | Mature adult | -19.4 | 10.7 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.06 | An Corran | n.d. | -21.2 | 11.1 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.07 | An Corran | n.d. | -21.1 | 9.9 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.08 | An Corran | n.d. | -21.0 | 10.1 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.09 | An Corran | n.d. | -20.7 | 10.3 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.10 | An Corran | n.d. | -20.8 | 9.8 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.11 | An Corran | n.d. | -20.5 | 10.8 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.12 | An Corran | n.d. | -20.2 | 11.4 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.13 | An Corran | n.d. | -20.1 | 10.1 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.14 | An Corran | n.d. | -19.9 | 9.7 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.15 | An Corran | n.d. | -19.7 | 9.0 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.16 | An Corran | n.d. | -19.7 | 10.2 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.17 | An Corran | n.d. | -19.6 | 10.6 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| AC.18 | An Corran | n.d. | -22.9 | 2.6 | Milner and Craig 2009 | |||||

| CMB.01 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C XIV:1 | Phalanx | Adult | -21.5 | 9.0 | 3.2 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.02 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C XV:1 | Metacarpal | Adult | -21.0 | 8.9 | 3.1 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.03 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C VII:130 | Parietal | Adult | -21.5 | 9.6 | 3.2 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.04 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C XXIII | Metatarsus | Adult | -21.4 | 9.8 | 3.1 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.05 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C III:74 | Humerus | Adult | -21.3 | 8.8 | 3.2 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.06 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C IV:94 | Phalanx | Adult | -21.5 | 10.0 | 3.1 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.07 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C V:105 | Femur | Adult | -21.3 | 8.9 | 3.2 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.08 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C VII:112 | Metatarsal | Adult | -21.3 | 9.1 | 3.2 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.09 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C XVII:1 | Phalanx | Adult | -21.5 | 9.9 | 3.1 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.10 | Carding Mill Bay 1 | C X:1 | Scapula | Non-adult | -21.3 | 9.5 | 3.1 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CMB.11 | Carding Mill Bay 2 | Incisor | Non-adult | -21.2 | 8.5 | 3.3 | Patterson et al. 2022 | |||

| CMB.12 | Carding Mill Bay 2 | PSUAMS-5772/5773/5774/5776 | Phalanx | F | Adult | -21.7 | 9.6 | 3.3 | 4832±14 | Patterson et al. 2022 |

| CLA.01 | Clachaig | SUERC-68711/I2988 | Petrous | F | n.d. | -21.6 | 11.2 | 3.3 | 4645±29 | Olalde et al. 2018 |

| CRA.01 | Crarae | 45 NN 1186.1 | Pelvis | Adult | -21.8 | 9.0 | 3.3 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CRA.02 | Crarae | 45 NN 1186.2 | Phalanx | Adult | -21.3 | 9.5 | 3.3 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| CRA.03 | Crarae | 59C NN 1123 | Patella | Adult? | -21.7 | 9.1 | 3.5 | Schulting and Richards 2002 | ||

| DC.01 | Distillery Cave | SUERC-68702/I2659 | Petrous | F | n.d. | -21.4 | 8.9 | 3.2 | 4914±27 | Olalde et al. 2018 |

| DC.02 | Distillery Cave | SUERC-68703/I2660 | Petrous | n.d. | -21.7 | 9.1 | 3.2 | 4631±29 | Olalde et al. 2018 | |

| DC.03 | Distillery Cave | SUERC-68704/I2691 | Petrous | M | n.d. | -21.8 | 8.6 | 3.2 | 4881±25 | Olalde et al. 2018 |

| MC.01 | MacArthur Cave | SUERC-68701/I2657 | Phalanx | M | Adult | -21.4 | 9.0 | 3.3 | 5052±30 | Olalde et al. 2018 |

| RC.01 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8537 | L Humerus | 1-2 yr | -21.8 | 11.9 | 3.3 | 4535±50 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.02 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8434 | R Femur | c. 3 yr | -21.1 | 8.7 | 3.4 | 4720±50 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.03 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8431 | L Femur | ?3-5 yr | -20.6 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 4930±50 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.04 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8399/I3137 | Cervical vertebra | M | 3-7 yr | -21.4 | 10.2 | 3.4 | 4630±65 | Bonsall 1999; Patterson et al. 2022 |

| RC.05 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8432 | R Humerus | 8-10 yr | -20.4 | 7.6 | 3.3 | 4980±50 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.06 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8401 | L Femur | ?10 yr | -21.1 | 9.1 | 3.3 | 4565±65 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.07 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8400 | Rib | Adult | -20.3 | 9.7 | 3.2 | 4640±65 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.08 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8444 | R Humerus | F | Adult | -21.1 | 9.6 | 3.5 | 4715±45 | Bonsall 1999 |

| RC.09 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8443 | R Humerus | Adult | -20.4 | 9.4 | 3.2 | 4825±55 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.10 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8433 | L Humerus | M | Adult | -20.2 | 9.4 | 3.2 | 4920±50 | Bonsall 1999 |

| RC.11 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8404 | R Humerus | Adult | -21.6 | 7.7 | 3.2 | 4850±70 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.12 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8441 | R Humerus | Adult? | -21.2 | 9.1 | 3.3 | 4900±45 | Bonsall 1999 | |

| RC.13 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8435 | Humerus | -22.5 | 10.3 | 3.4 | 4680±50 | Bonsall 1999 | ||

| RC.14 | Raschoille Cave | OxA-8442 | R Humerus | -21.0 | 8.7 | 3.3 | 4890±45 | Bonsall 1999 | ||

| RC.15 | Raschoille Cave | PSUAMS-2068/I3135 | Petrous | M | -21.5 | 9.6 | 3.2 | 4770±30 | Olalde et al. 2018 | |

| RC.16 | Raschoille Cave | PSUAMS-2069/I3136 | Petrous | F | -21.0 | 9.0 | 3.3 | 4665±30 | Olalde et al. 2018 | |

| RC.17 | Raschoille Cave | PSUAMS-2154/I3133 | Petrous | M | -21.7 | 9.6 | 3.0 | 4725±20 | Olalde et al. 2018 | |

| RC.18 | Raschoille Cave | PSUAMS-2155/I3134 | Petrous | M | -22.2 | 11.0 | 3.2 | 4730±25 | Olalde et al. 2018 | |

| RC.19 | Raschoille Cave | PSUAMS-2156/I3138 | Petrous | F | -22.1 | 9.4 | 3.2 | 4415±25 | Olalde et al. 2018 | |

| RC.20 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40818/ SB 513A2/I3041 | Petrous | M | Adult | -21.9 | 8.4 | 3.5 | 4550±29 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 |

| RC.21 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40819/SUERC-67265/SB525A2 | Petrous | F | Adult? | -21.7 | 7.7 | 3.3 | 4738±31 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 |

| RC.22 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40820/SUERC-67266/SB526A | Petrous | F? | Adult | -21.6 | 7.7 | 3.3 | 4817±31 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 |

| RC.23 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40821/SUERC-67267/SB528A2/I5371 | Petrous | F | Indeterminate | -22.1 | 8.8 | 3.3 | 4490±29 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 |

| RC.24 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40822/SUERC-67268/SB527A1/ I5370 | Petrous | F | Adult? | -21.5 | 9.2 | 3.3 | 4499±29 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 |

| RC.25 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40823 | -21.9 | 9.5 | 3.3 | 4668±29 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 | |||

| RC.26 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40824 | -22.3 | 10.2 | 3.2 | 4432±31 | Bownes et al. 2017 | |||

| RC.27 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40825/SUERC-67271 | Petrous | Non-adult | -22.4 | 10.4 | 3.3 | 4731±29 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 | |

| RC.28 | Raschoille Cave | GU-40826/SUERC-67275 | Petrous | Non-adult | -22.2 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 4638±31 | Bownes et al. 2017; Knight et al. 2021 | |

| UC.01 | Ulva Cave | PSUAMS-5771 | Long bone | M | Adult | -21.0 | 9.9 | 3.2 | 4895±25 | Patterson et al. 2022 |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Δ15Ndiet-consumer | 5.5±0.5‰ |

| Δ13Cdiet-consumer | 4.8±0.5‰ |

| Food source isotope values – Plants | δ13Cprotein = -26.4±1.0‰; δ13Cenergy= -24.1±1.0‰; δ15N = 2.8±1.0‰ |

| Food source isotope values – Terrestrial animals | δ13Cprotein = -24.4±1.0‰, δ13Cenergy= -30.4±1.0‰; δ15N = 3.3±1.0‰ |

| Food source isotope values – Fish | δ13Cprotein = -14.0±1.0‰, δ13Cenergy= -20.0±1.0‰; δ15N = 15.4±1.0‰ |

| Food source isotope values – Shellfish | δ13Cprotein = -14.6±1.0‰, δ13Cenergy= -18.1±1.0‰; δ15N = 7.4±1.0‰ |

| Food source nutrient concentrations – Plants | Protein:energy – 10:90 |

| Food source nutrient concentrations – Terrestrial animals | Protein:energy – 70:30 |

| Food source nutrient concentrations – Fish | Protein:energy – 75:25 |

| Food source nutrient concentrations – Shellfish | Protein:energy – 90:10 |

| Prior | 0.05 ≤ protein intake ≥ 0.35 |

| Sample | δ13C | δ15N | PLANTS | TERRESTRIAL ANIMAL | FISH | SHELLFISH | ||||||||

| ME (Cal) | CI (68%) | ME (Pro) | ME (Cal) | CI (68%) | ME (Pro) | ME (Cal) | CI (68%) | ME (Pro) | ME (Cal) | CI (68%) | ME (Pro) | |||

| AC.01 | -20.7 | 9.8 | 75±11 | 63-88 | 34±17 | 22±11 | 9-34 | 54±19 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 2±2 | 0-3 | 6±5 |

| AC.02 | -20.6 | 9.8 | 75±12 | 62-90 | 34±20 | 22±12 | 7-34 | 54±21 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 2±2 | 0-3 | 6±5 |

| AC.03 | -20.5 | 9.4 | 75±11 | 63-87 | 34±17 | 21±10 | 10-32 | 54±19 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 2±2 | 0-3 | 6±5 |

| AC.04 | -20.2 | 10.2 | 75±11 | 63-89 | 35±17 | 20±11 | 7-31 | 50±19 | 2±2 | 1-4 | 7±5 | 2±2 | 0-4 | 8±6 |

| AC.05 | -19.4 | 10.7 | 73±10 | 63-85 | 31±14 | 20±9 | 9-29 | 48±17 | 4±2 | 1-6 | 10±6 | 3±3 | 1-6 | 10±8 |

| CMB.01 | -21.5 | 9.0 | 77±12 | 63-91 | 38±20 | 21±12 | 7-34 | 54±22 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 5±4 |

| CMB.02 | -21.0 | 8.9 | 76±12 | 63-91 | 37±21 | 21±12 | 6-34 | 53±22 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 5±5 |

| CMB.03 | -21.5 | 9.6 | 77±12 | 63-92 | 38±20 | 21±12 | 6-34 | 52±22 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 5±4 |

| CMB.04 | -21.4 | 9.8 | 76±12 | 63-91 | 37±20 | 21±11 | 7-33 | 53±21 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 |

| CMB.05 | -21.3 | 8.8 | 78±13 | 64-94 | 42±22 | 19±12 | 4-33 | 50±23 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 3±3 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 5±4 |

| CMB.06 | -21.5 | 10.0 | 76±12 | 63-92 | 38±21 | 21±12 | 6-33 | 52±22 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 |

| CMB.07 | -21.3 | 8.9 | 77±12 | 64-91 | 38±20 | 21±12 | 7-33 | 53±21 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 5±4 |

| CMB.08 | -21.3 | 9.1 | 76±12 | 64-91 | 38±19 | 21±11 | 7-34 | 53±20 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 |

| CMB.09 | -21.5 | 9.9 | 76±12 | 63-91 | 37±20 | 21±12 | 7-34 | 54±21 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 4±4 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±4 |

| CRA.01 | -21.8 | 9.0 | 77±13 | 63-93 | 40±21 | 20±12 | 6-34 | 52±22 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 3±3 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±4 |

| CRA.02 | -21.3 | 9.5 | 75±12 | 63-90 | 36±20 | 22±11 | 8-34 | 55±21 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 5±5 |

| CRA.03 | -21.7 | 9.1 | 77±12 | 64-91 | 38±20 | 21±12 | 7-33 | 54±21 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±4 |

| MC.01 | -21.4 | 9.0 | 75±12 | 62-90 | 36±19 | 22±11 | 8-34 | 56±21 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 5±4 |

| RC.07 | -20.3 | 9.7 | 75±11 | 64-87 | 34±17 | 21±10 | 9-32 | 53±19 | 2±2 | 0-4 | 6±4 | 2±2 | 0-4 | 7±6 |

| RC.08 | -21.1 | 9.6 | 77±12 | 64-91 | 38±20 | 21±12 | 7-33 | 52±21 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 5±5 |

| RC.09 | -20.4 | 9.4 | 75±11 | 64-88 | 35±17 | 21±10 | 9-32 | 53±19 | 2±2 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 2±2 | 0-4 | 7±6 |

| RC.10 | -20.2 | 9.4 | 75±11 | 63-88 | 34±17 | 21±10 | 9-32 | 53±18 | 2±2 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 2±2 | 0-1 | 7±6 |

| RC.11 | -21.6 | 7.7 | 77±13 | 63-93 | 41±22 | 21±12 | 5-35 | 53±23 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 2±2 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±4 |

| RC.12 | -21.2 | 9.1 | 75±12 | 63-90 | 36±19 | 21±11 | 8-33 | 55±20 | 1±1 | 0-2 | 4±3 | 1±1 | 0-3 | 5±5 |

| UC.01 | -21 | 9.9 | 74±11 | 63-88 | 34±18 | 22±11 | 9-33 | 55±19 | 2±2 | 0-3 | 5±4 | 2±1 | 0-3 | 6±5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).