Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

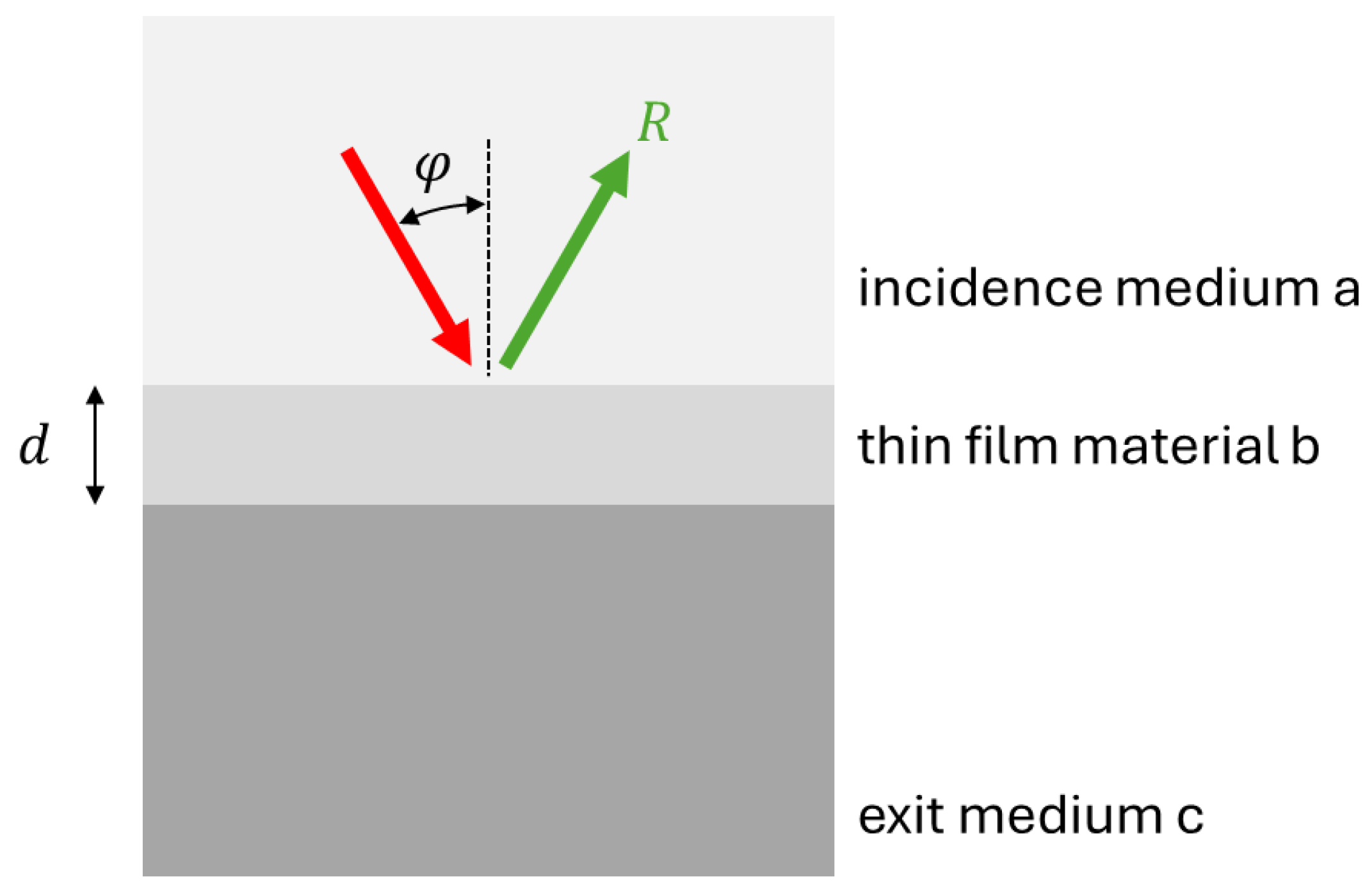

2. Theoretical Aspects

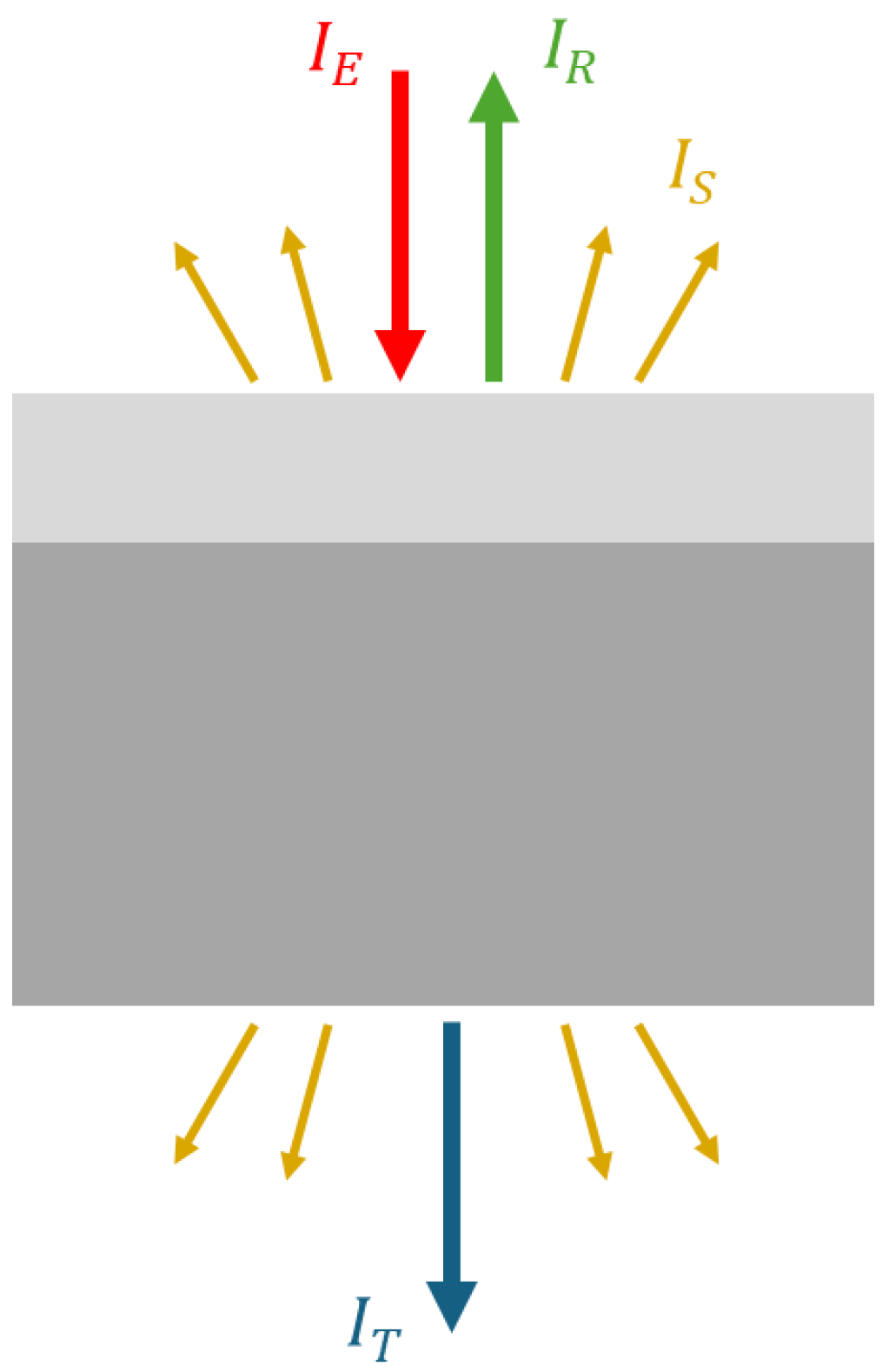

2.1. First Considerations

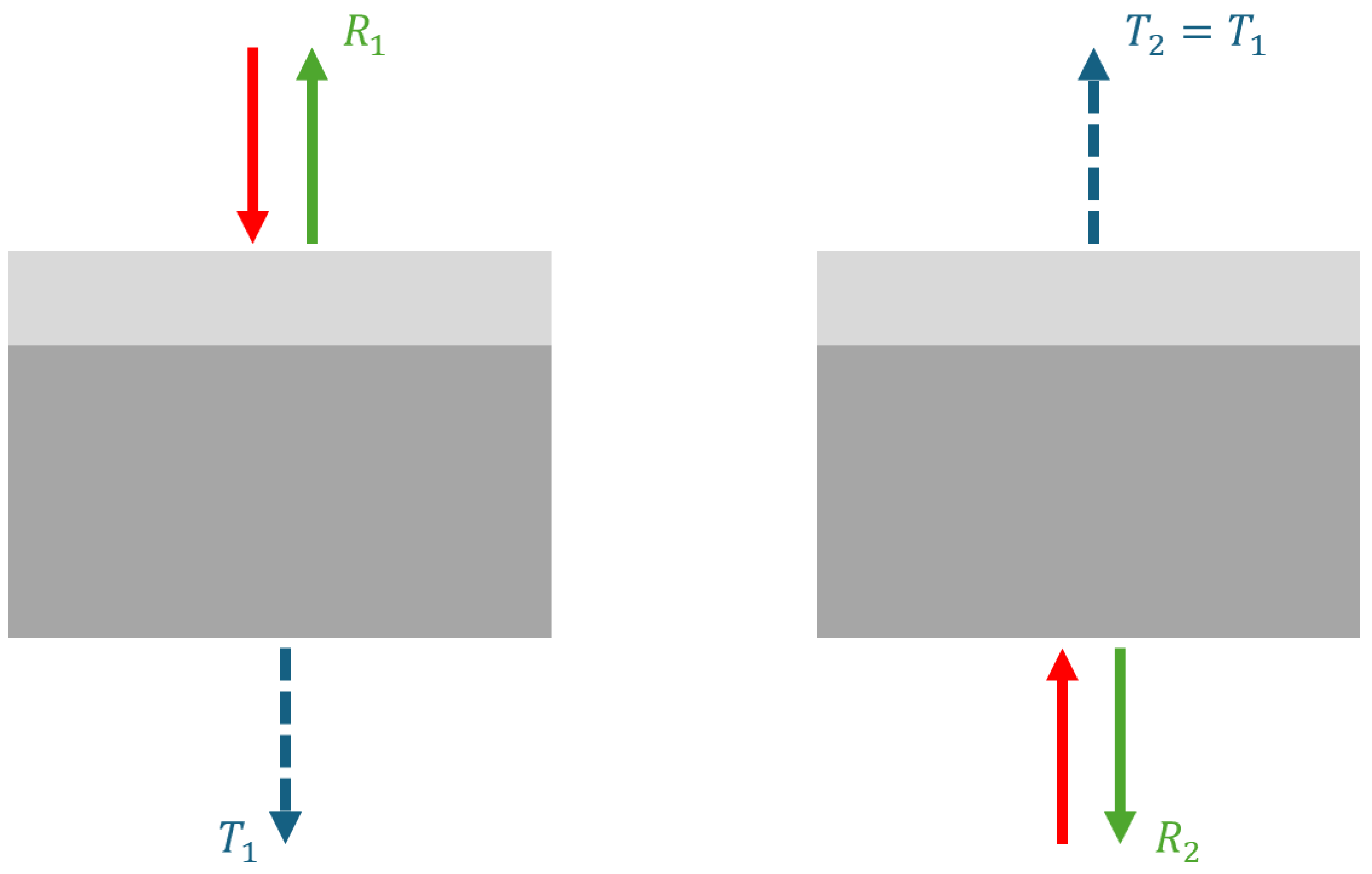

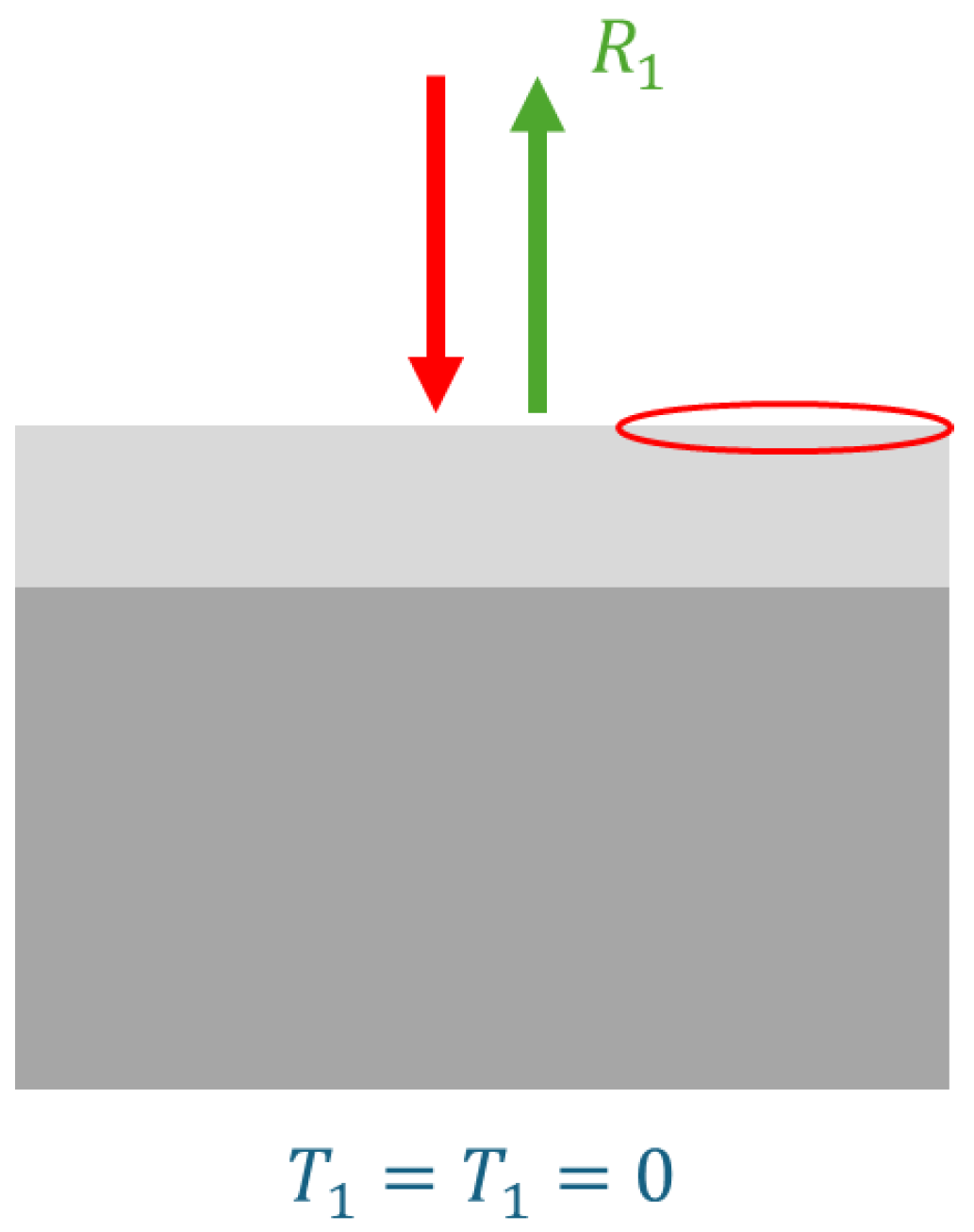

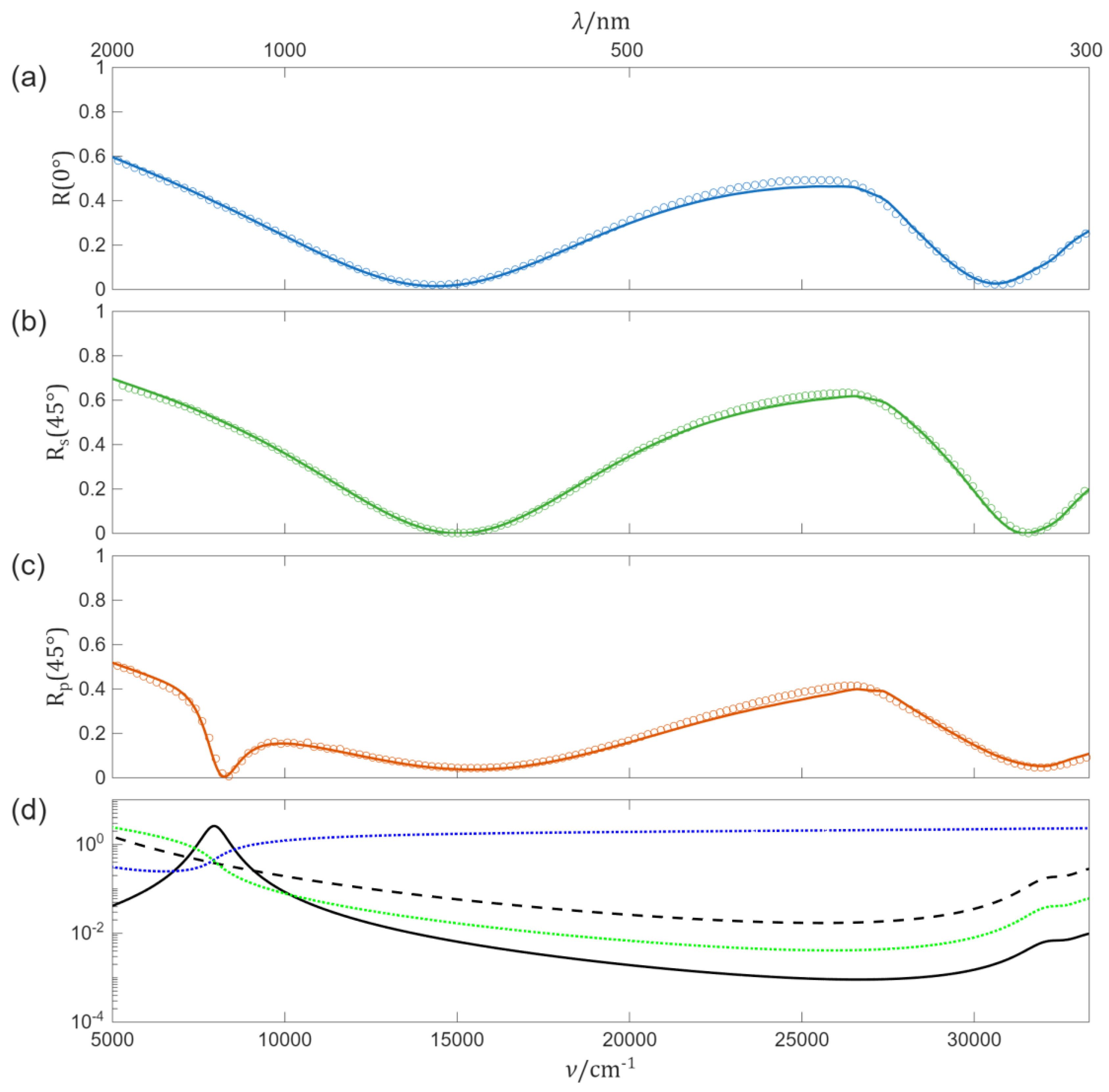

2.2. The Reflection of a Single Interface at Normal Incidence

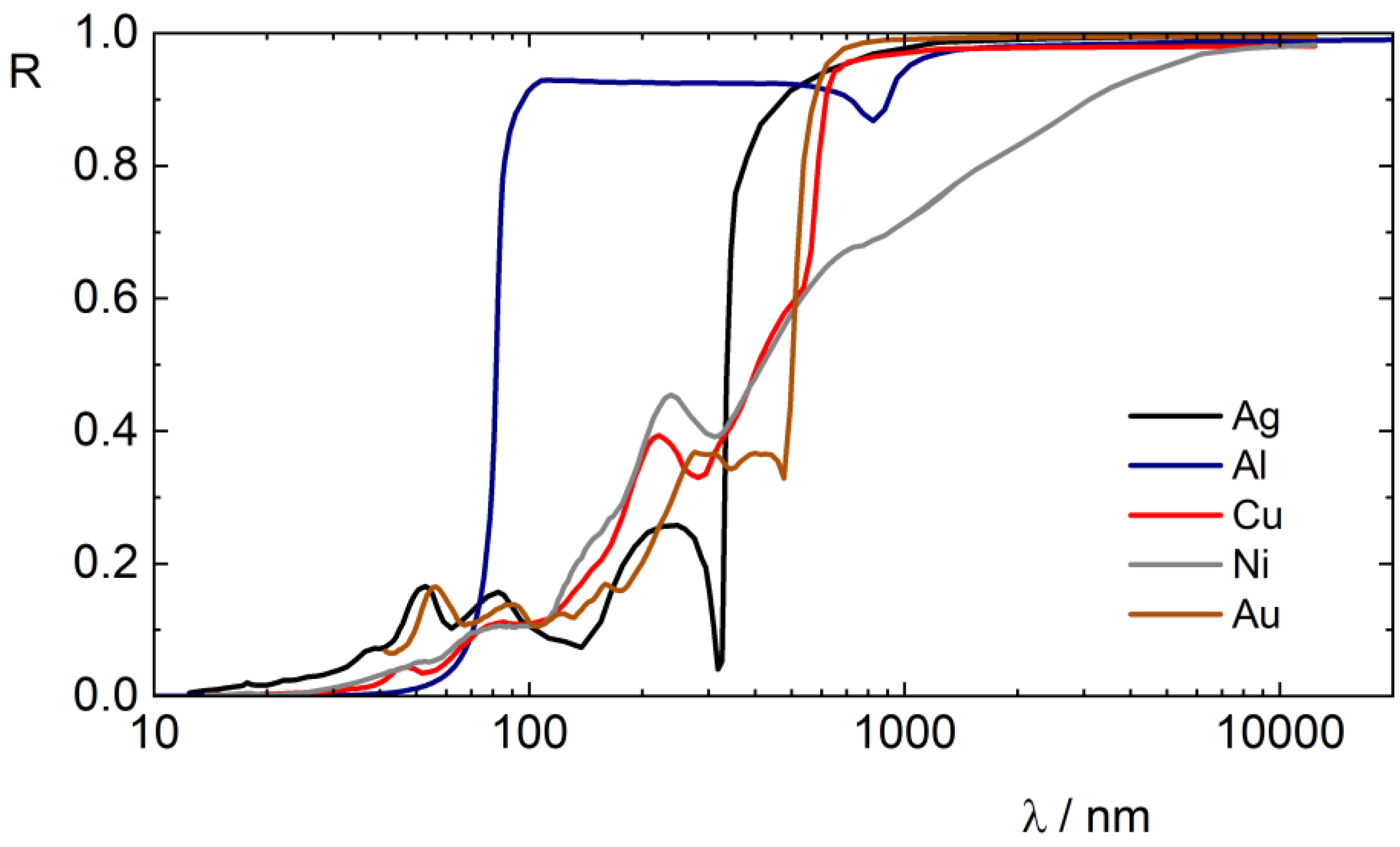

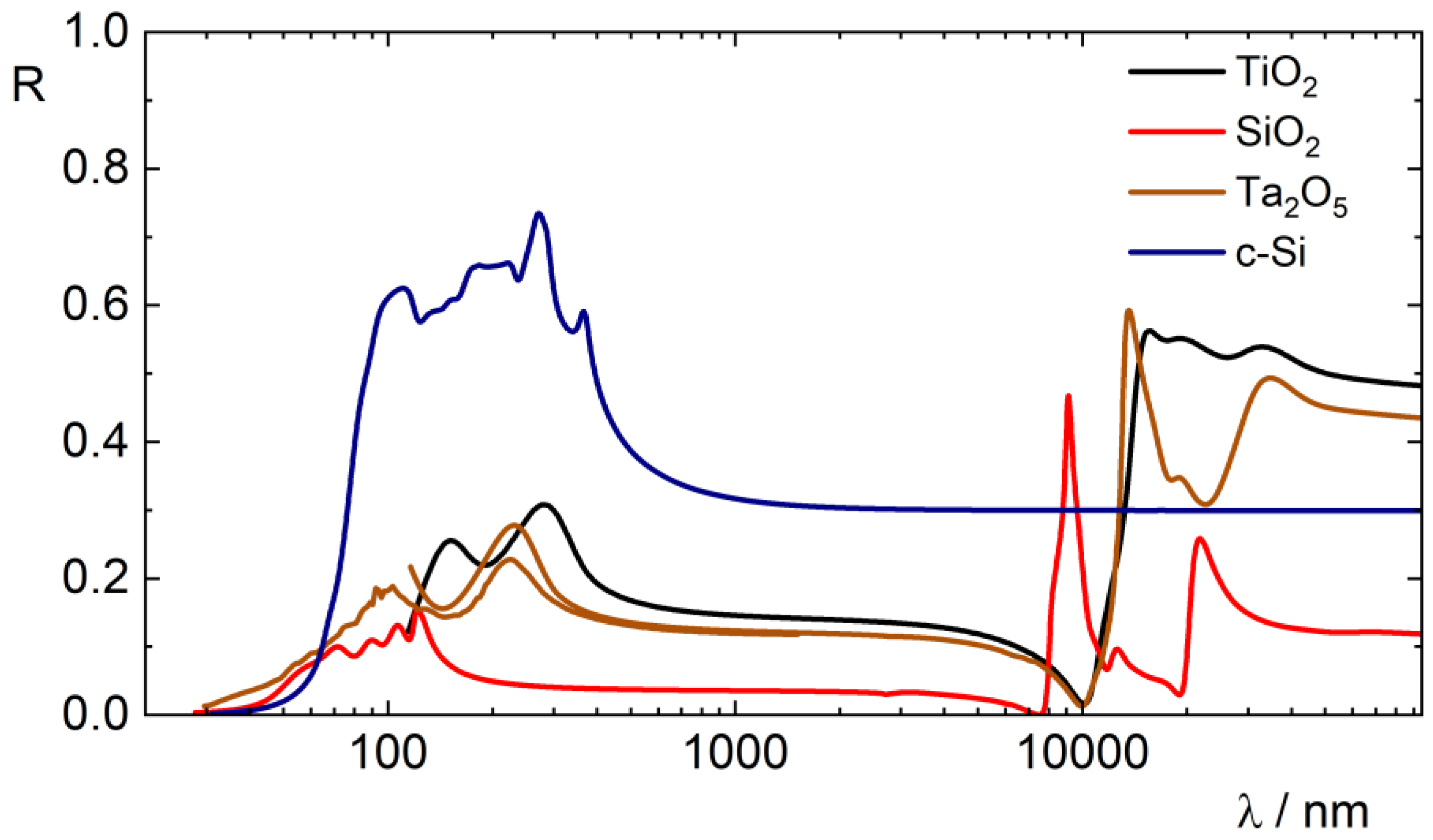

- For , the reflectance approaches zero. This is observed in metals and dielectrics (or semiconductors) alike.

- For , the reflectance of all metals approaches one. This is different to the behaviour of dielectrics.

- In the UV/VIS/IR spectral regions, the reflectance of several materials shows specific spectral features as characteristic to resonances.

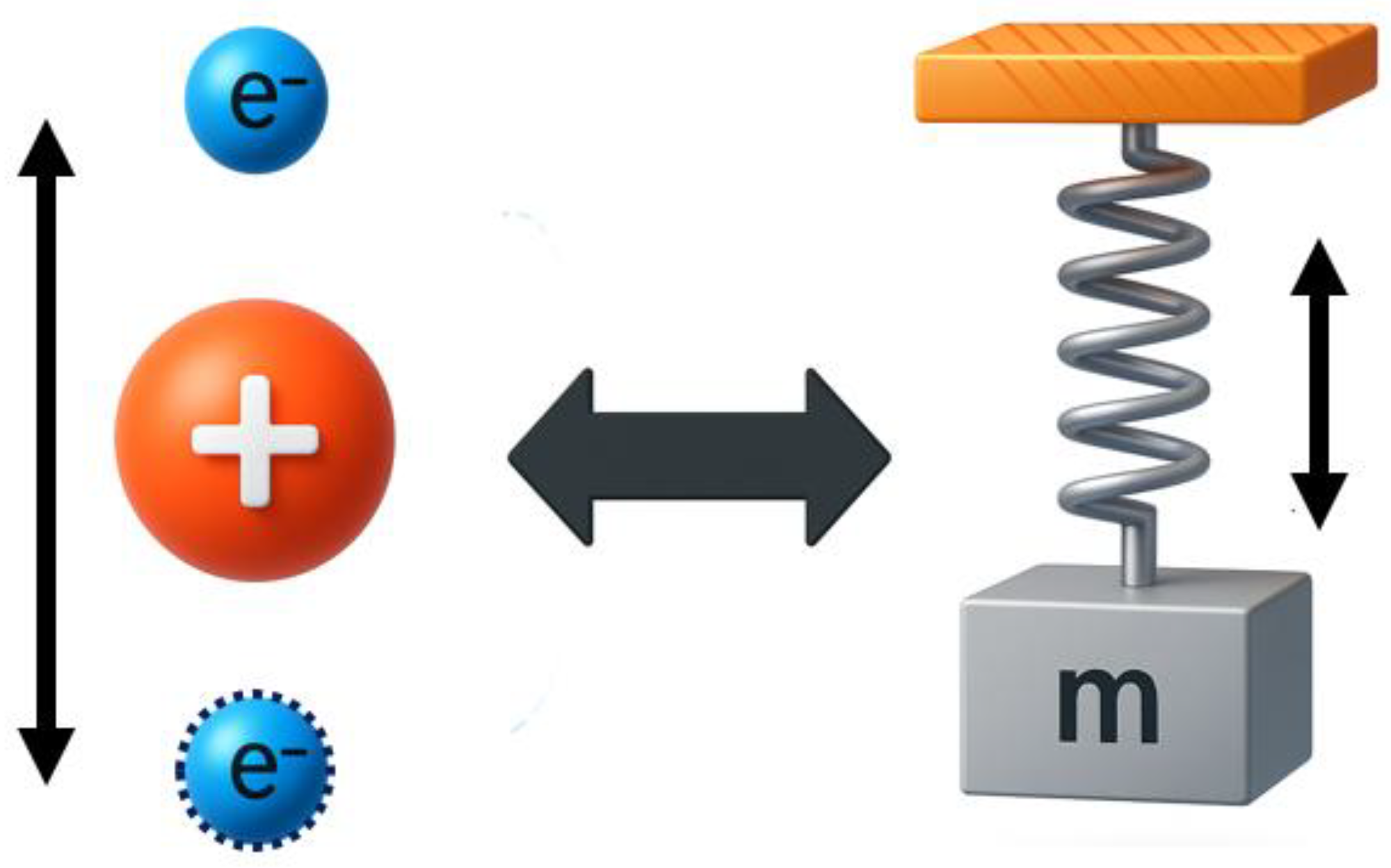

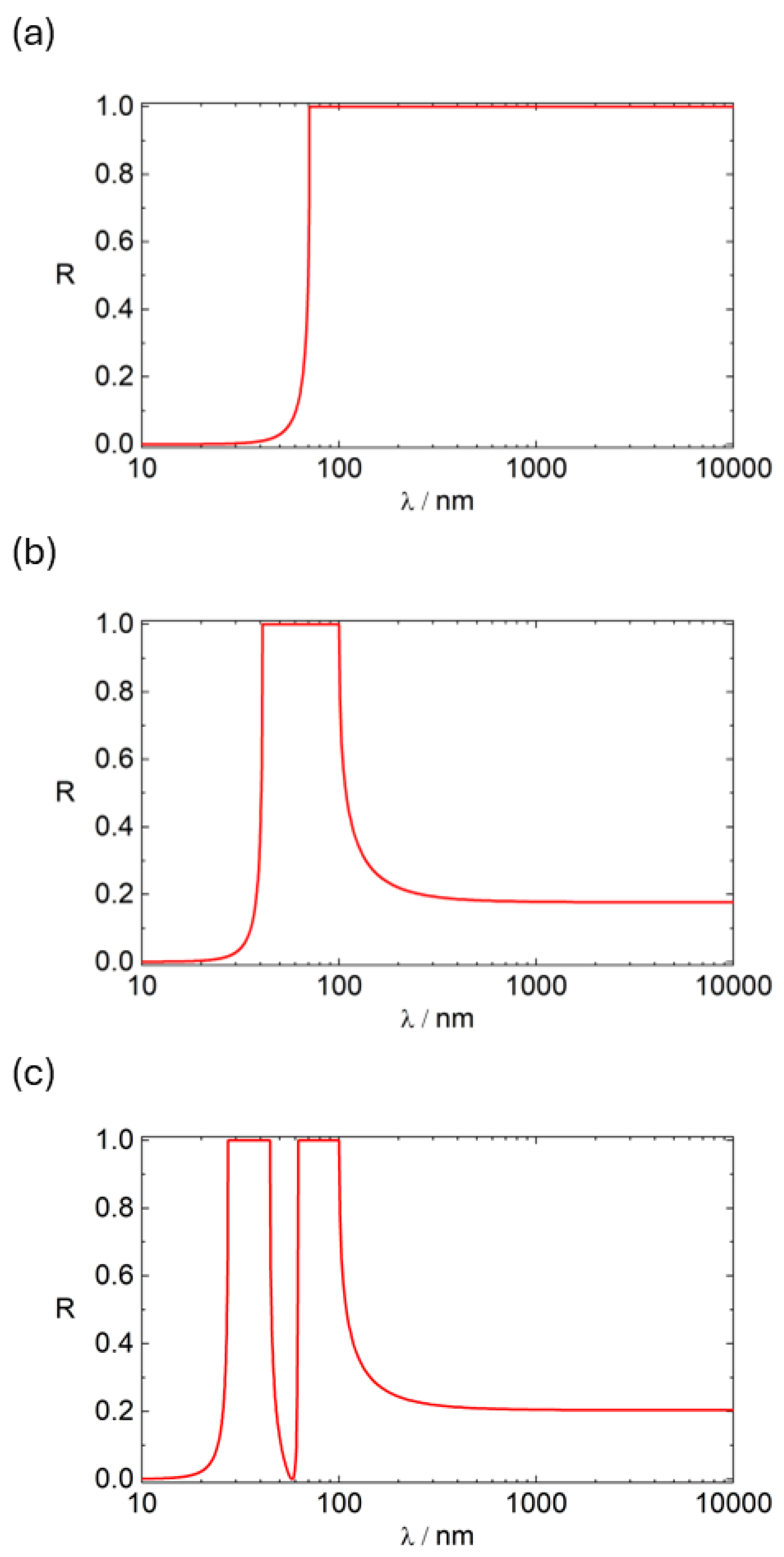

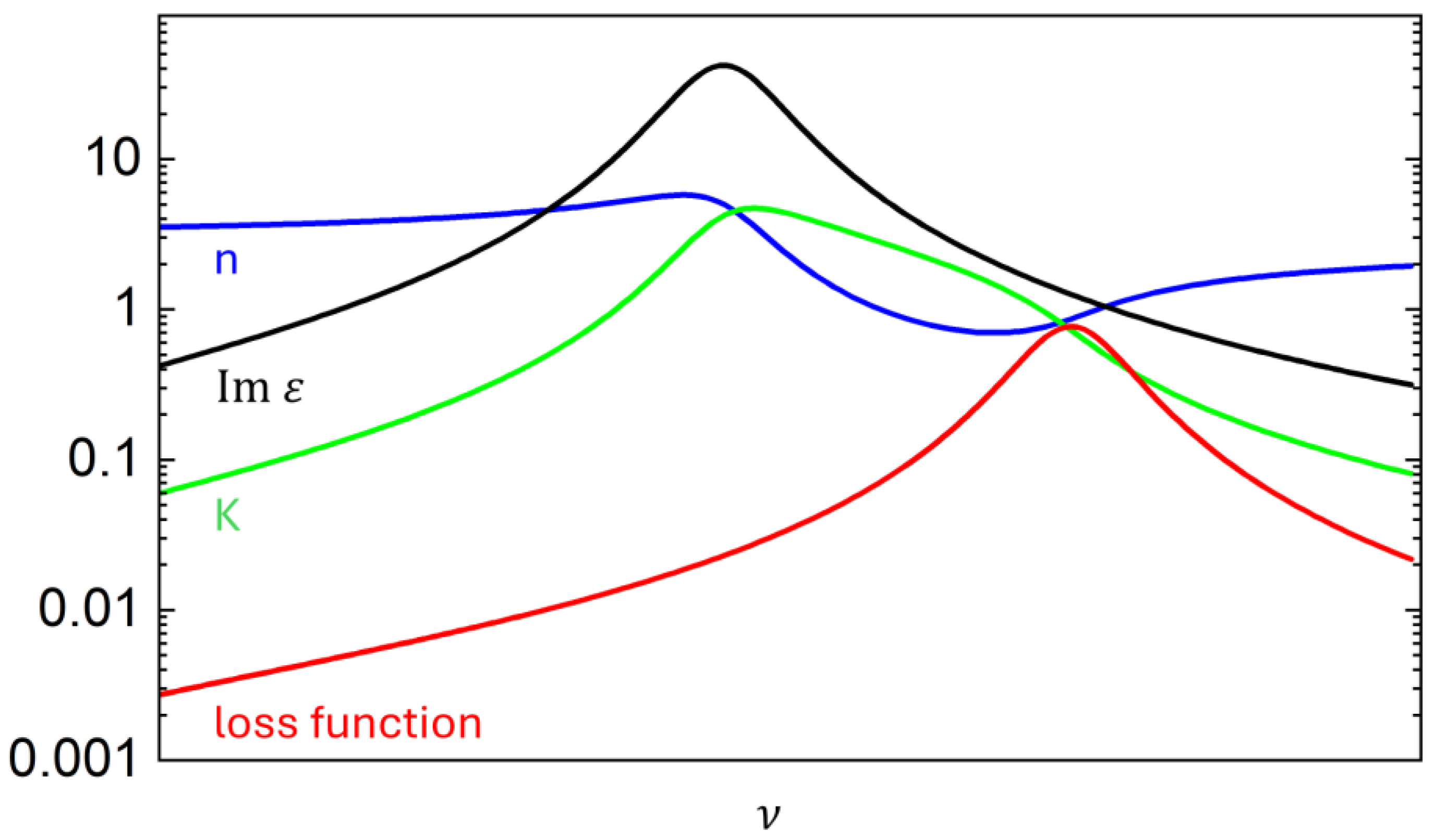

2.3. A Simple Oscillator Model Approach

- A practically infinitively large electric field or

- A vanishing denominator in (11) and (12).

2.4. More General Dispersion Formulas

- Relation (20) does not suffice thermodynamics, because relaxation is excluded

- At resonance, shows a singularity, that is not observed in reality

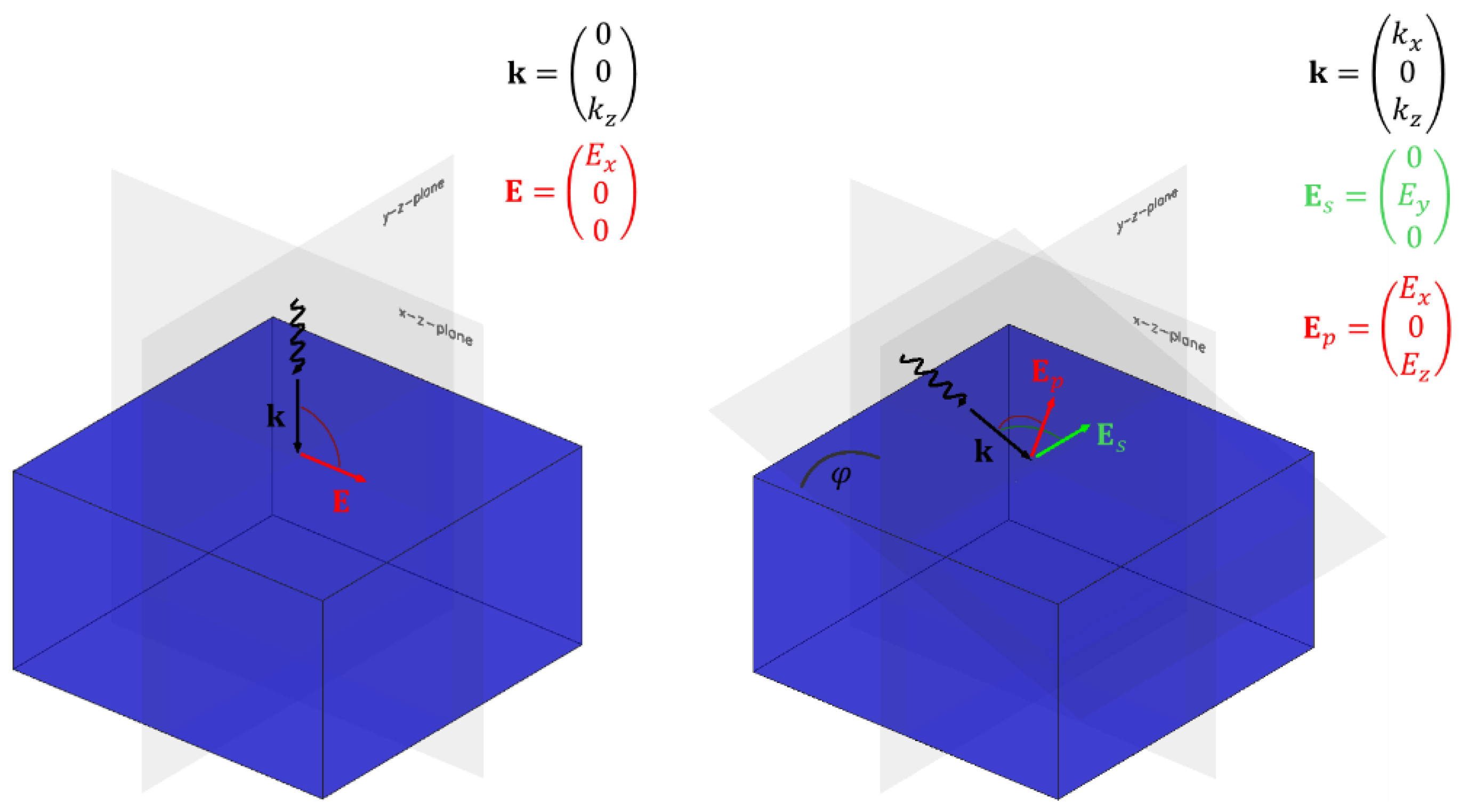

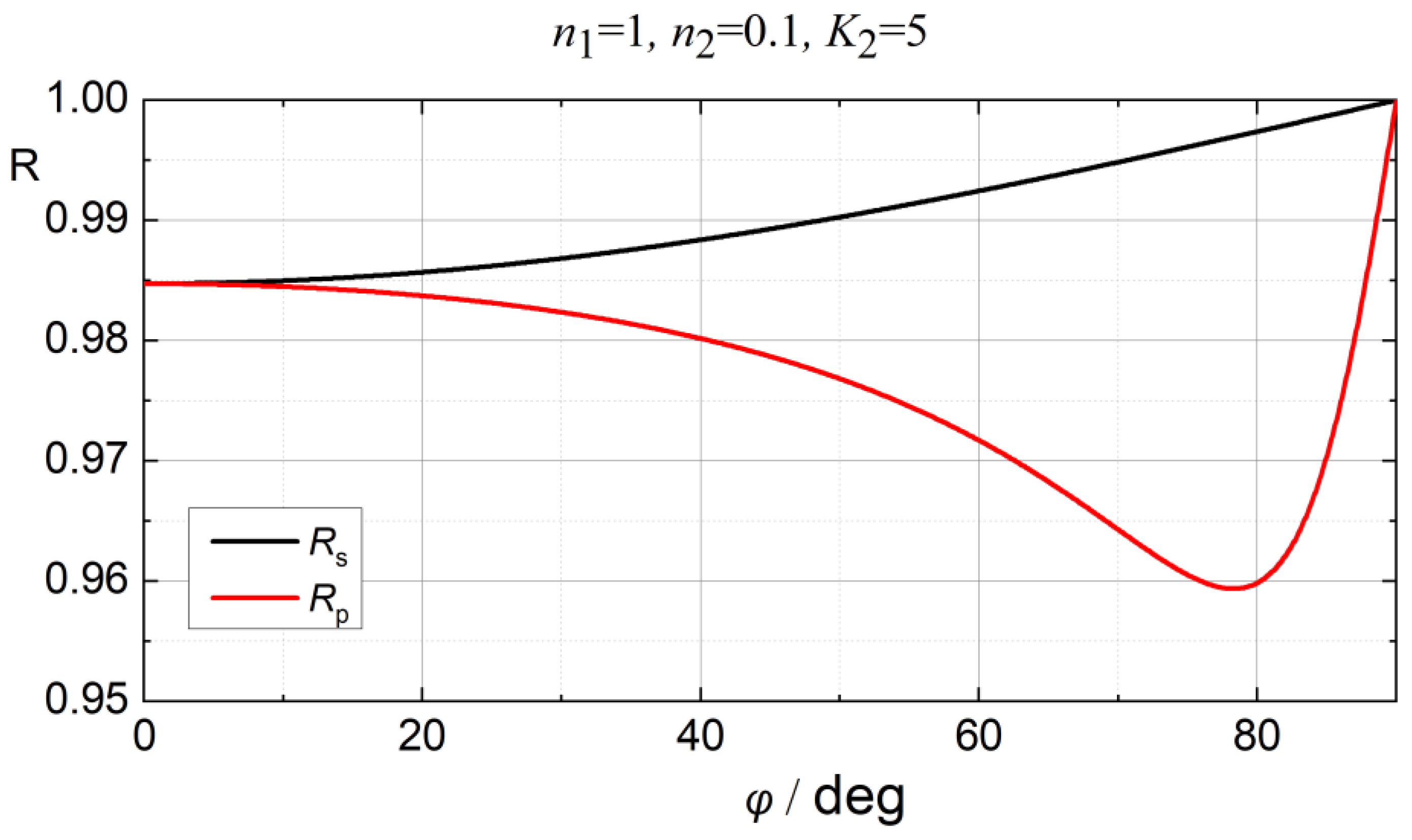

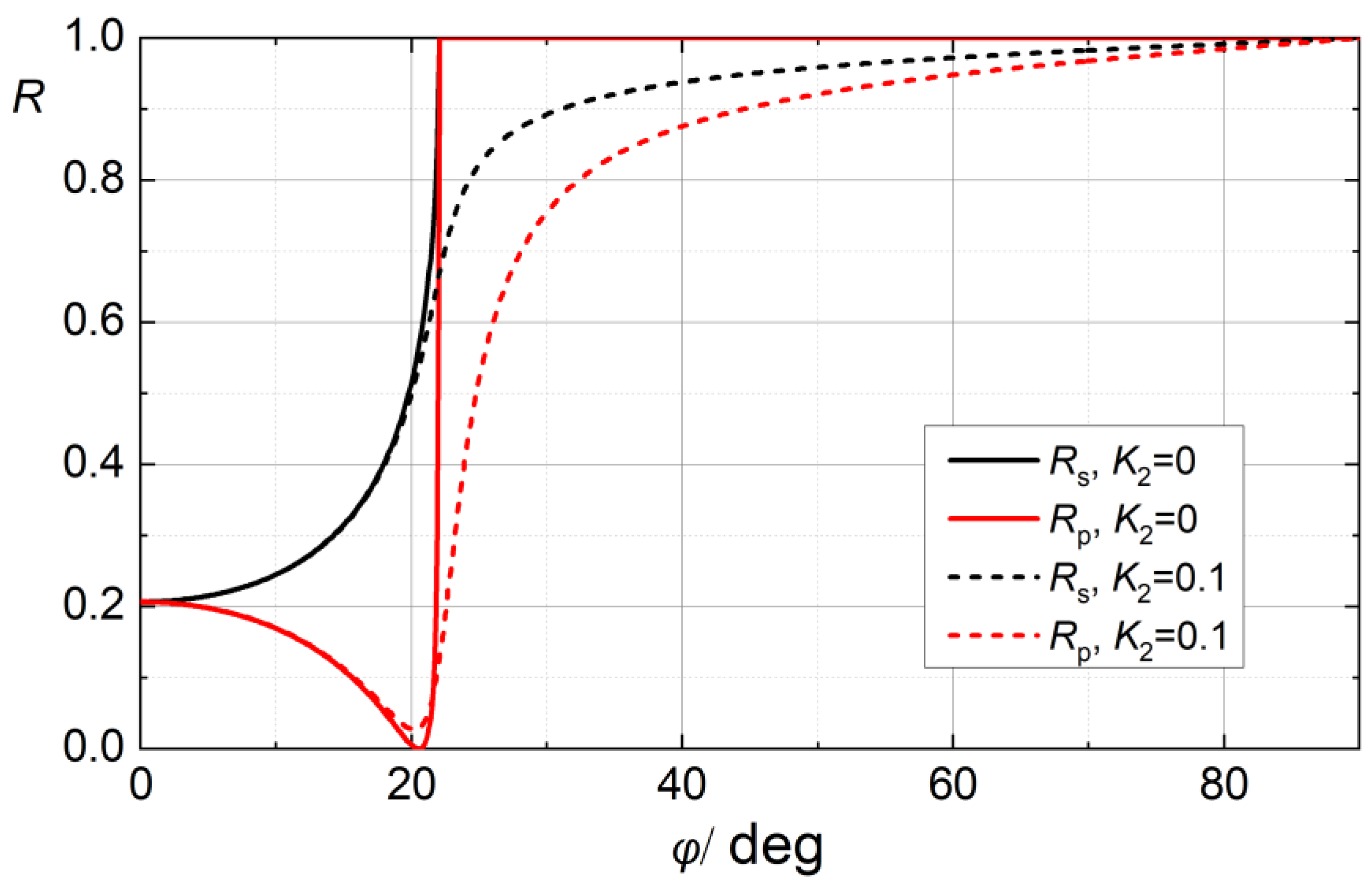

2.5. Oblique Incidence

2.6. Short Survey of Derived Experimental Techniques

2.6.1. Phase Reconstruction by Means of the Kramers-Kronig Formula

2.6.2. Cavity Ringdown Decay

2.6.3. Imaging Spectroscopic Reflectometry ISR

2.6.4. Reflectance Anisotropy Spectroscopy RAS

3. Selected Applications

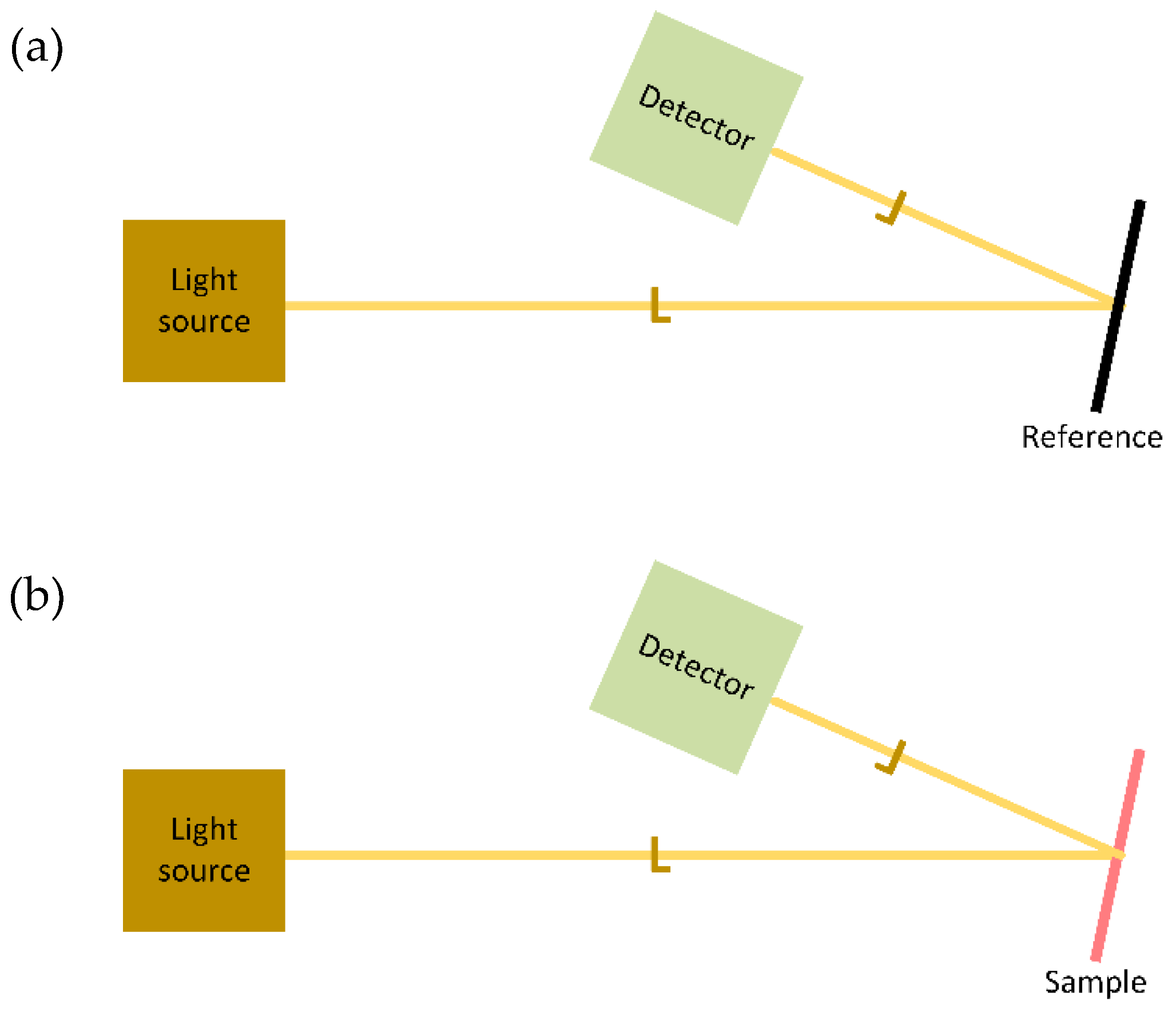

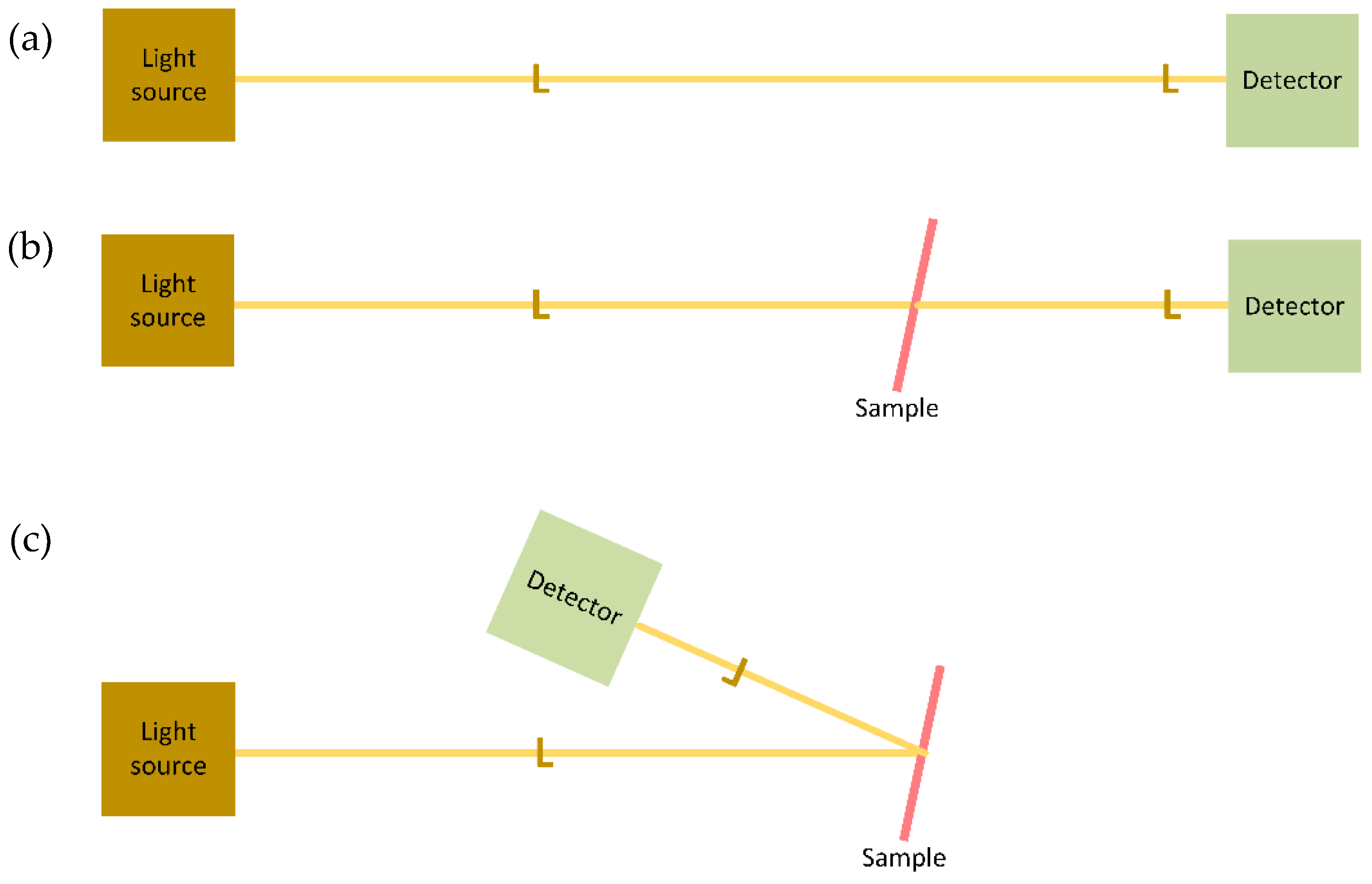

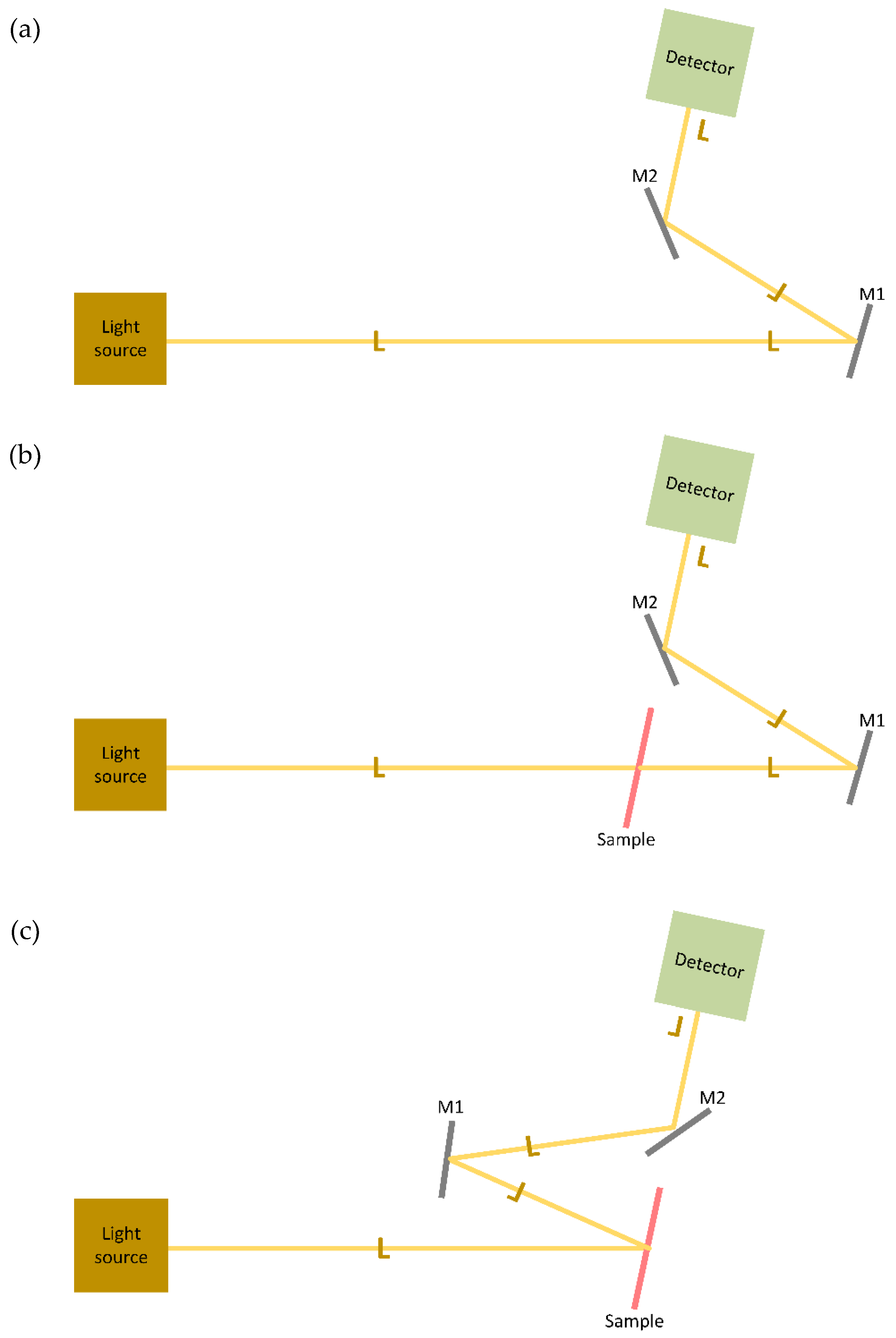

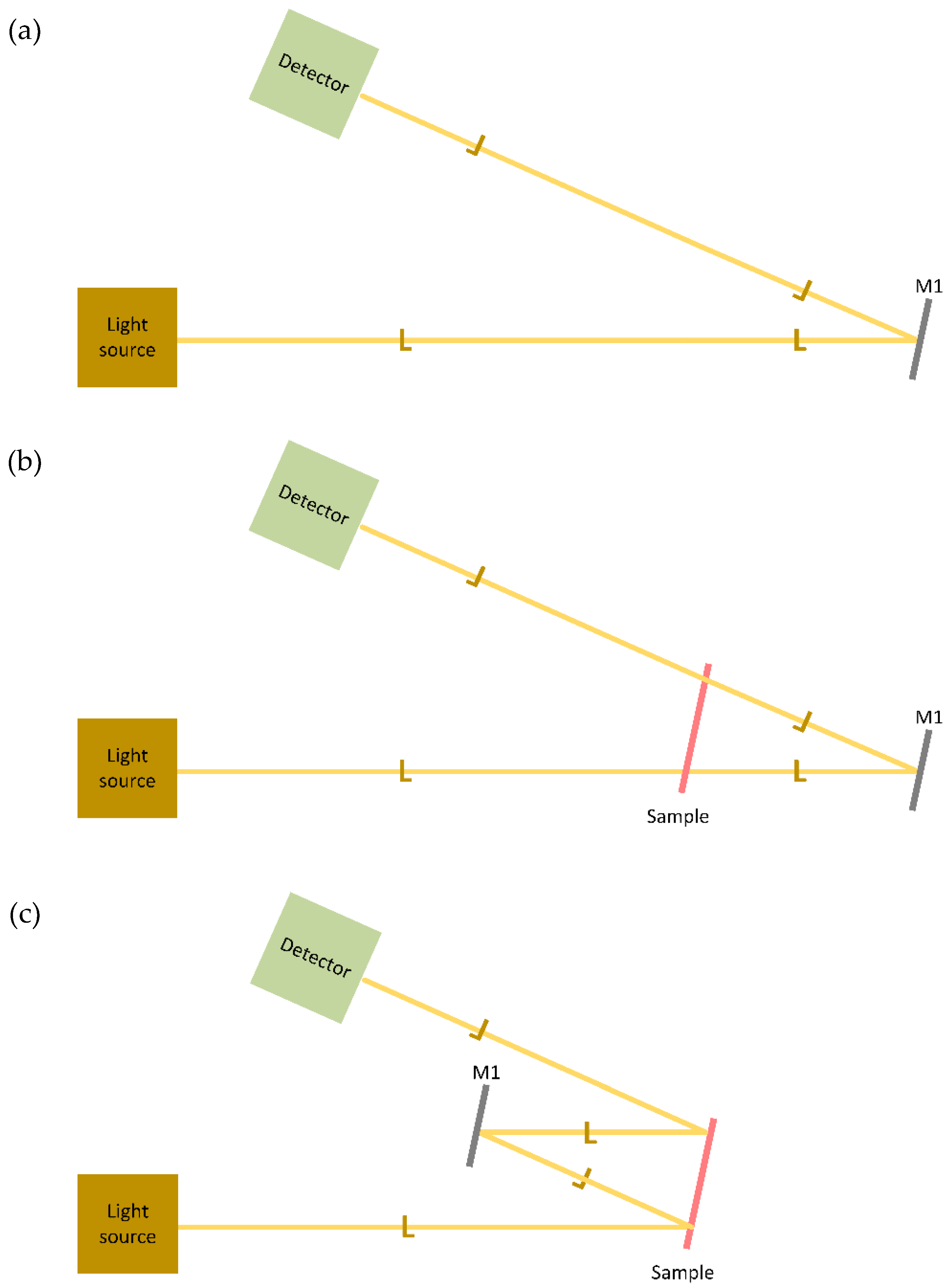

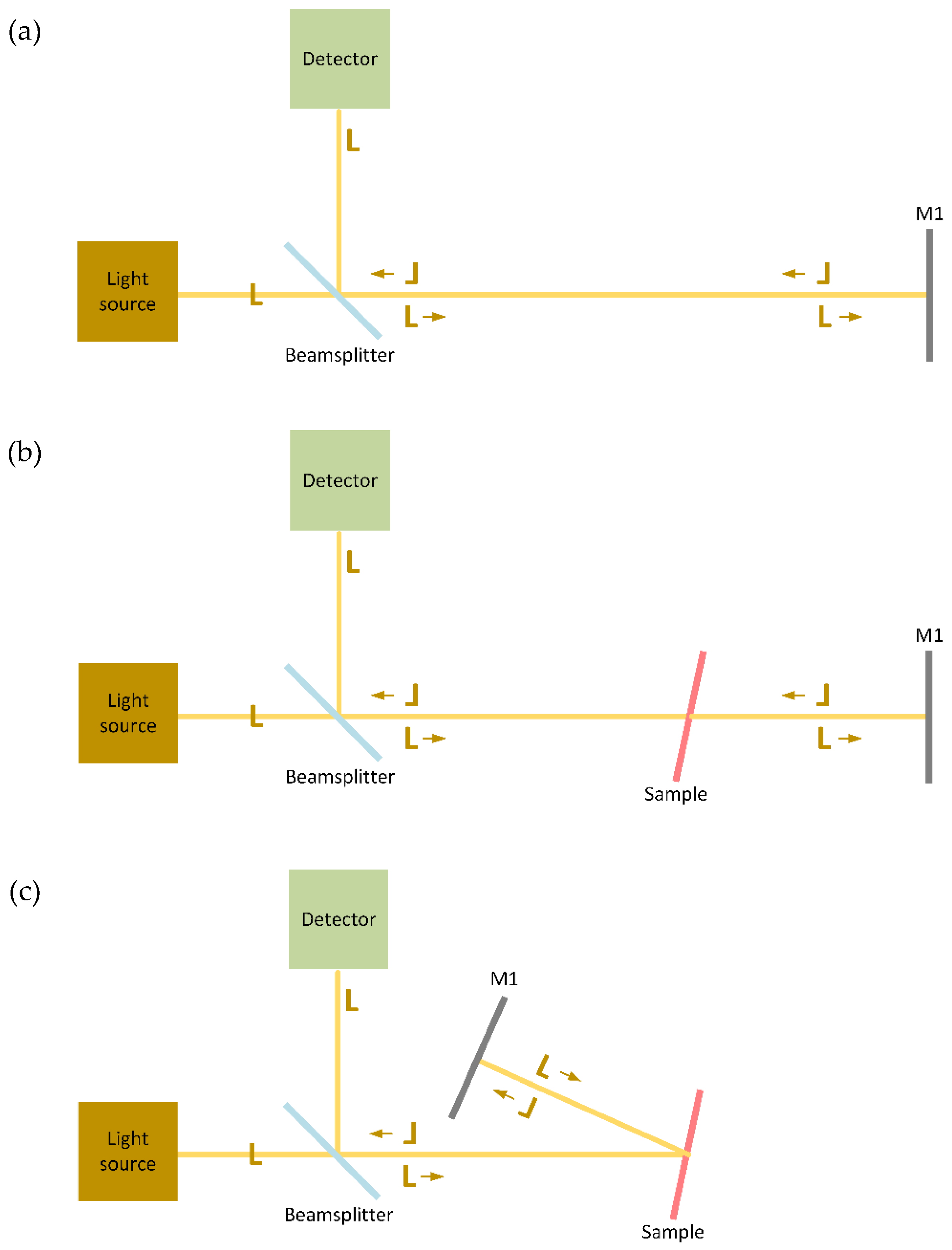

3.1. Measurement Aspects of R

3.2. Specific Oblique and Grazing Incidence Applications

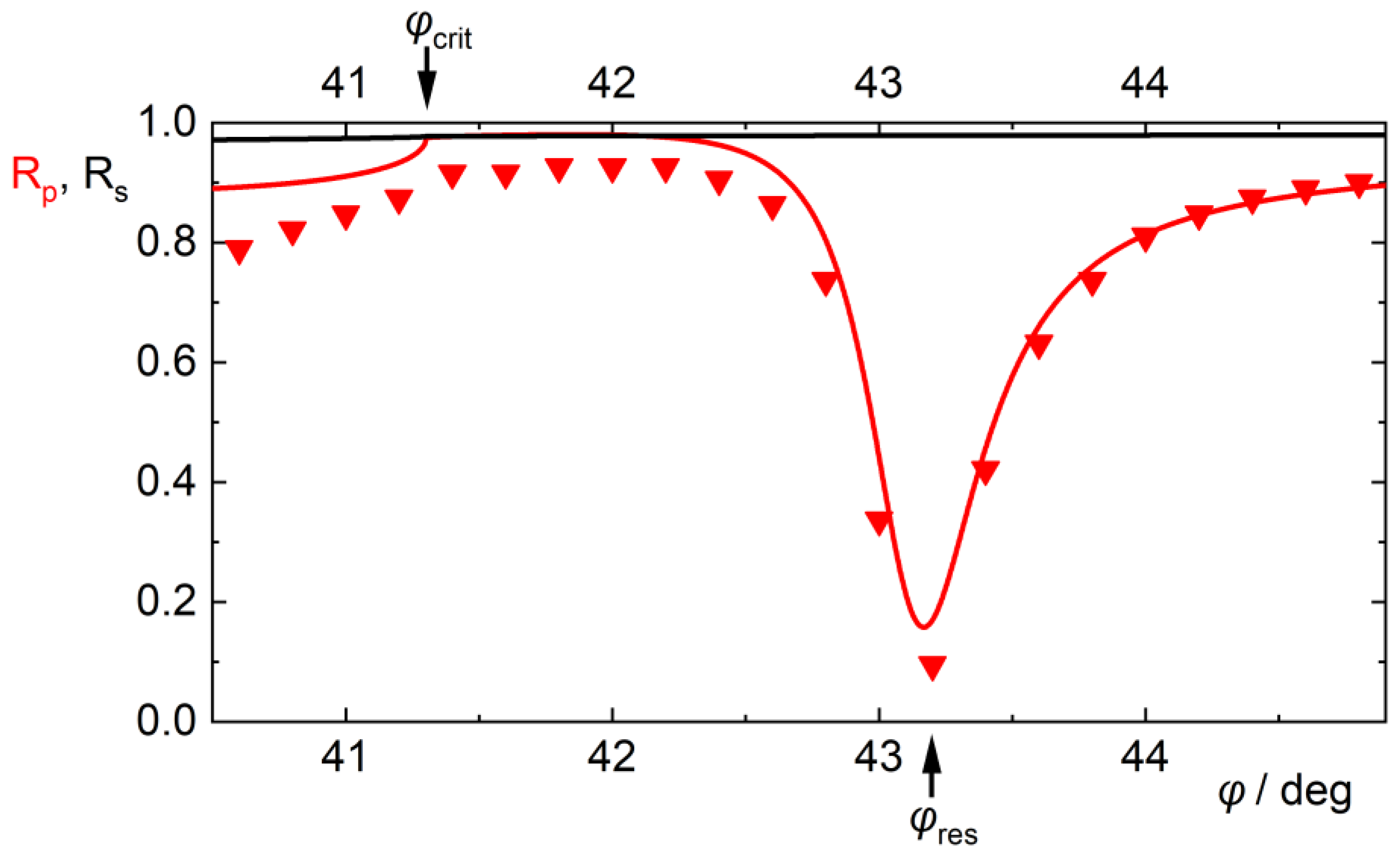

3.2.1. Total Internal Reflection

3.2.2. Infrared Reflection Absorption Spectroscopy IRAS

- A very large (by modulus) . This is exactly what we use in IRAS, where a metal is used as the (c) - medium (Figure 18).

4. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Born, M.; Wolf, E. Principles of Optics; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK; London, UK; Edinburgh, UK; New York, NY, USA; Paris, France; Frankfurt, Germany, 1968.

- Landau, D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Electrodynamics of Continuous Media; Volume 8 of A Course of Theoretical Physics; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1960.

- Сивухин, Д.В. Общий курс физики. Оптика. Наука, Мoсква, СССР, 1980.

- Willey, R. R. Practical Design of Optical Thin Films; Lulu.com, 2021; 566.

- Macleod, H. A. Thin-film optical filters; 5th edition; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

- Thelen, A. Design of optical interference coatings; McGraw-Hill, 1989.

- Willey, R. R. Designing solar control coatings. Appl. Opt. 2024, 63, 4891–4895. [CrossRef]

- Willey, R. R. Designing black mirrors. Appl. Opt. 2024, 63, 4020–4023. [CrossRef]

- Willey, R. R. and Stenzel, O. Designing Optical Coatings with Incorporated Thin Metal Films. Coatings 2023, 13, 369. [CrossRef]

- Pulker, H. K. Characterization of optical thin films. Appl. Opt. 1979, 18, 1969–1977. [CrossRef]

- Landau, D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Statistical Physics, Part 1; Volume 5 of A Course of Theoretical Physics; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1980.

- Absorbance. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absorbance (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Stenzel, O. and Wilbrandt, S. Theoretical Aspects of Thin Film Optical Spectra: Underlying Models, Model Restrictions and Inadequacies, Algorithms, and Challenges. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2187. [CrossRef]

- Furman, S.A.; Tikhonravov, A.V. Basics of Optics of Multilayer Systems; Edition Frontieres: Gif-sur-Yvette, France, 1992.

- Stenzel, O. The Physics of Thin Film Optical Spectra: An Introduction; Springer International Publishing, 2024.

- Ehrenreich, H. and Philipp, H. R. Optical Properties of Ag and Cu. Phys. Rev. 1962, 128, 1622–1629. [CrossRef]

- Ohlídal, I. and Navrátil, K. Optical analysis of inhomogeneous weakly absorbing thin films by spectroscopic reflectometry: Application to carbon films. Thin Solid Films 1988, 162, 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Ohlídal, I. and Navrátil, K. Simple method of spectroscopic reflectometry for the complete optical analysis of weakly absorbing thin films: Application to silicon films. Thin Solid Films 1988, 156, 181-190. [CrossRef]

- Tabet, M. F. and McGahan, W. A. Use of artificial neural networks to predict thickness and optical constants of thin films from reflectance data. Thin Solid Films 2000, 370, 122-127. [CrossRef]

- Morinishi, Y. and Maeda, Y. Development of the Model for Estimating Thickness and Optical Constants of Metallic Thin Films using Only Reflection Spectrum. IEEJ Transactions on Sensors and Micromachines 2025, 145, 220-225. [CrossRef]

- Wilbrandt, S.; Petrich, R. and Stenzel, O. Optical interference coating characterization using neural networks. In: SPIE International Society for Optics and Photonics, 1999, 517–528.

- UNIGIT. Grating Solver Software. Available online: https://unigit.net (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Polyanskiy, M. N. Refractive index database. Available online: https://refractiveindex.info. (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Franta, D.; Nečas, D.; Ohlídal, I. and Giglia, A. Dispersion model for optical thin films applicable in wide spectral range.In: SPIE International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2015, 96281U.

- Franta, D.; Nečas, D.; Ohlídal, I. and Giglia, A. Optical characterization of SiO2 thin films using universal dispersion model over wide spectral range.In: SPIE International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2016, 989014.

- Franta, D.; Dubroka, A.; Wang, C.; Giglia, A.; Vohánka, J.; Franta, P. and Ohlídal, I. Temperature-dependent dispersion model of float zone crystalline silicon. Applied Surface Science 2017, 421, 405-419. [CrossRef]

- Stenzel, O. Optical Coatings: Material Aspects in Theory and Practice; 1st ed.; Springer Berlin / Heidelberg, 2014.

- Berreman, D. W. Infrared Absorption at Longitudinal Optic Frequency in Cubic Crystal Films. Phys. Rev. 1963, 130, 2193–2198. [CrossRef]

- Grosse, P. and Offermann, V. Quantitative infrared spectroscopy of thin solid and liquid films under attenuated total reflection conditions. Vibrational Spectroscopy 1995, 8, 121-133. [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. P. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. II; The new millennium edition: Mainly Electromagnetism and Matter. Basic Books, 2011.

- Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Sydney, Australia; Toronto, ON, Canada, 1971.

- Fox, M. Optical properties of solids; Second edition, reprinted (with corrections); Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Stenzel, O. Light–Matter Interaction: A Crash Course for Students of Optics, Photonics and Materials Science; Springer International Publishing, 2022.

- Zallen, R. Symmetry and Reststrahlen in Elemental Crystals. Phys. Rev. 1968, 173, 824–832. [CrossRef]

- Bartelmann, M.; Feuerbacher, B.; Krüger, T.; Lüst, D.; Rebhan, A. and Wipf, A. Theoretische Physik; Springer Berlin Heidelberg 2014.

- Dobrowolski, J. A.; Ho, F. C. and Waldorf, A. Determination of optical constants of thin film coating materials based on inverse synthesis. Applied Optics 1983, 22, 3191. [CrossRef]

- Ziman, J. M. Principles of the theory of solids; Second edition; Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Kuzmany, H. Festkörperspektroskopie: Eine Einführung. Springer, Germany, Berlin Heidelberg 1989.

- Cooper, B. R.; Ehrenreich, H. and Philipp, H. R. Optical Properties of Noble Metals. II. Phys. Rev. 1965, 138, A494–A507. [CrossRef]

- Ehrenreich, H. The optical properties of metals. IEEE Spectrum 1965, 2, 162-170. [CrossRef]

- Ordal, M. A.; Bell, R. J.; Alexander, R. W.; Long, L. L. and Querry, M. R. Optical properties of fourteen metals in the infrared and far infrared: Al, Co, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Mo, Ni, Pd, Pt, Ag, Ti, V, and W. Appl. Opt. 1985, 24, 4493–4499. [CrossRef]

- Macleod, A. Phase Matters, SPIE’s OE magazine, June/July (2005), pp. 29-31.

- Azzam, R.M.A. and Bashara, N.M. Ellipsometry and Polarized Light; Elsevier Amsterdam 1987.

- Lucarini, V. Kramers-Kronig Relations in Optical Materials Research; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005.

- Grosse, P. and Offermann, V. Analysis of reflectance data using the Kramers-Kronig Relations. Applied Physics A Solids and Surfaces 1991, 52, 138–144. [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, A. and Deacon, D. A. G. Cavity ring-down optical spectrometer for absorption measurements using pulsed laser sources. Review of Scientific Instruments 1988, 59, 2544-2551. [CrossRef]

- Kelsall, D. Absolute Specular Reflectance Measurements of Highly Reflecting Optical Coatings at 10.6 micro. Appl. Opt. 1970, 9, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, V. High-precision reflectivity measurement technique for low-loss laser mirrors. Appl. Opt. 1977, 16, 19–20. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. Z.; Frisch, J. C. and Masser, C. S. Mirror reflectometer based on optical cavity decay time. Appl. Opt. 1984, 23, 1238–1245. [CrossRef]

- Herbelin, J. M.; McKay, J. A.; Kwok, M. A.; Ueunten, R. H.; Urevig, D. S.; Spencer, D. J. and Benard, D. J. Sensitive measurement of photon lifetime and true reflectances in an optical cavity by a phase-shift method. Appl. Opt. 1980, 19, 144–147. [CrossRef]

- Karras, C. Cavity Ring-Down Technique for Optical Coating Characterization. 2018, In: Stenzel, O., Ohlídal, M. (eds) Optical Characterization of Thin Solid Films. Springer Series in Surface Sciences, Vol. 64. Springer, Cham, 433–456. [CrossRef]

- ISO 13142:2021; Optics and photonics — Lasers and laser-related equipment — Cavity ring-down method for high-reflectance and high-transmittance measurements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Xiao, S.; Li, B. and Wang, J. Precise measurements of super-high reflectance with cavity ring-down technique. Metrologia 2020, 57, 055002. [CrossRef]

- von Lerber, T. and Sigrist, M. W. Cavity-ring-down principle for fiber-optic resonators: experimental realization of bending loss and evanescent-field sensing. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 3567–3575. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Jiao, H. and O’Keefe, A. Cavity-enhanced spectroscopy in optical fibers. Opt. Lett. 2002, 27, 1878–1880. [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.; Wiberg, K. B.; Vaccaro, P. H.; Cheeseman, J. R. and Frisch, M. J. Cavity ring-down polarimetry (CRDP): theoretical and experimental characterization. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2002, 19, 125–141. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Li, B.; Xiao, S.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, C. and Wang, Y. Simultaneous mapping of reflectance, transmittance and optical loss of highly reflective and anti-reflective coatings with two-channel cavity ring-down technique. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 5807–5820. [CrossRef]

- Romanini, D.; Kachanov, A.; Sadeghi, N. and Stoeckel, F. CW cavity ring down spectroscopy. Chemical Physics Letters 1997, 264, 316-322. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M. D.; Newman, S. M.; Orr-Ewing, A. J. and Ashfold, M. N. R. Cavity ring-down spectroscopy. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1998, 94, 337-351. [CrossRef]

- Zu, H.; Li, B.; Han, Y. and Gao, L. Combined cavity ring-down and spectrophotometry for measuring reflectance of optical laser components. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 26735–26741. [CrossRef]

- Berden, G.; Peeters, R. and Meijer, G. Cavity ring-down spectroscopy: Experimental schemes and applications. International Reviews in Physical Chemistry 2000, 19, 565–607. [CrossRef]

- Ohlídal, M., Vodák, J., Nečas, D. Optical Characterization of Thin Films by Means of Imaging Spectroscopic Reflectometry. 2018, In: Stenzel, O., Ohlídal, M. (eds) Optical Characterization of Thin Solid Films. Springer Series in Surface Sciences, Vol. 64. Springer, Cham, 107–141. [CrossRef]

- Nečas, D. Data Processing Methods for Imaging Spectrophotometry. 2018, In: Stenzel, O., Ohlídal, M. (eds) Optical Characterization of Thin Solid Films. Springer Series in Surface Sciences, Vol. 64. Springer, Cham, 143–175. [CrossRef]

- Vodák, J.; Nečas, D.; Pavliňák, D.; Macak, J. M.; Řičica, T.; Jambor, R. and Ohlídal, M. Application of imaging spectroscopic reflectometry for characterization of gold reduction from organometallic compound by means of plasma jet technology. Applied Surface Science 2017, 396, 284-290. [CrossRef]

- Weightman, P.; Martin, D. S.; Cole, R. J. and Farrell, T. Reflection anisotropy spectroscopy. Reports on Progress in Physics 2005, 68, 1251–1341. [CrossRef]

- Richter, W. and Zettler, J.-T. Real-time analysis of III–V-semiconductor epitaxial growth. Applied Surface Science 1996, 100-101, 465-477. [CrossRef]

- Germer, T.A.; Zwinkels, J.C.; Tsai, B.K. Spectrophotometry: Accurate Measurement of Optical Properties of Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014.

- Jiang, Y.; Zhao, S. and Jalali, B. Invited Article: Optical dynamic range compression. APL Photonics 2018, 3, 110806. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, F. J. J. High Accuracy Spectrophotometry at the National Physical Laboratory. Journal of research of the National Bureau of Standards. Section A, Physics and chemistry 1972, 76A, 375-403. [CrossRef]

- Zwinkels, J. C.; Noël, M. and Dodd, C. X. Procedures and standards for accurate spectrophotometric measurements of specular reflectance. Appl. Opt. 1994, 33, 7933–7944. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, H. E. and Koehler, W. F. Precision Measurement of Absolute Specular Reflectance with Minimized Systematic Errors. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1960, 50, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, H. E. Accurate Method for Determining Photometric Linearity. Appl. Opt. 1966, 5, 1265–1270. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, A.; Campos, J. and Pons, A. Correction of photoresponse nonuniformity for matrix detectors based on prior compensation for their nonlinear behavior. Appl. Opt. 2006, 45, 2422–2427. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. M. How Linear Are Typical CCDs?. Experimental Astronomy 1998, 8, 59–72. [CrossRef]

- Theocharous, E.; Ishii, J. and Fox, N. P. Absolute linearity measurements on HgCdTe detectors in the infrared region. Appl. Opt. 2004, 43, 4182–4188. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. J. Spectral Nonlinearity Characteristics of Low Noise Silicon Detectors and their Application to Accurate Measurements of Radiant Flux Ratios. Metrologia 1979, 15, 173. [CrossRef]

- Chandran, H. T.; Mahadevan, S.; Ma, R.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, F.; Tsang, S.-W. and Li, G. Deriving the linear dynamic range of next-generation thin-film photodiodes: Pitfalls and guidelines. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 124, 101113. [CrossRef]

- Photomultiplier tubes: Basics and Applications. Available online: https://www.hamamatsu.com/content/dam/hamamatsu-photonics/sites/documents/99_SALES_LIBRARY/etd/PMT_handbook_v4E.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Zwinkels, J. C. and Gignac, D. S. Automated high precision variable aperture for spectrophotometer linearity testing. Appl. Opt. 1991, 30, 1678–1687. [CrossRef]

- Wilbrandt, S. and Stenzel, O. In Situ and Ex Situ Spectrophotometric Characterization of Single- and Multilayer-Coatings II: Experimental Technique and Application Examples. 2018, In: Stenzel, O., Ohlídal, M. (eds) Optical Characterization of Thin Solid Films. Springer Series in Surface Sciences, Vol. 64. Springer, Cham, 203–232. [CrossRef]

- Polato, P. and Masetti, E. Reflectance measurements on second-surface solar mirrors using commercial spectrophotometer accessories. Solar Energy 1988, 41, 443-452. [CrossRef]

- Goebel, D. G. Generalized Integrating-Sphere Theory. Appl. Opt. 1967, 6, 125–128. [CrossRef]

- Jacquez, J. A. and Kuppenheim, H. F. Theory of the Integrating Sphere. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1955, 45, 460–470. [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, W. and Altarouti, A. High-accuracy mid-infrared spectroscopy through innovative spectrometer design. 2025, Proc. SPIE 13603, Applied Optical Metrology VI, 1360314. [CrossRef]

- Birch, J. R. and Clarke, F. J. J. Fifty categories of ordinate error in Fourier transform spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Eur. 1995, 7, 18.

- van Nijnatten, P. A. Chapter 5 - Regular Reflectance and Transmittance. 2014, 46, 143-178. [CrossRef]

- Hass, G. Reflectance and preparation of front-surface mirrors for use at various angles of incidence from the ultraviolet to the far infrared. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1982, 72, 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Guenther, K. H.; Penny, I. and Willey, R. R. Corrosion-resistant front surface aluminum mirror coatings. Optical Engineering 1993, 32, 547 – 552. [CrossRef]

- Voarino, P.; Piombini, H.; Sabary, F.; Marteau, D.; Dubard, J.; Hameury, J. and Filtz, J. R. High-accuracy measurements of the normal specular reflectance. Appl. Opt. 2008, 47, C303–C309. [CrossRef]

- Zerlaut, G. A. and Anderson, T. E. Multiple-integrating sphere spectrophotometer for measuring absolute spectral reflectance and transmittance. Applied optics 1981, 20, 3797-804. [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, L. Integrating-sphere system and method for absolute measurement of transmittance, reflectance, and absorptance of specular samples. Appl. Opt. 2001, 40, 3196–3204. [CrossRef]

- Full-Spectrum, Angle-Resolved Reflectance and Transmittance of Optical Coatings Using the LAMBDA 1050+ UV/VIS/NIR Spectrophotometer with the ARTA Accessory. Technical Note, Available online: https://www.perkinelmer.com/library/tch-full-spectrum-angle-resolved-reflectance-transmittance-optical-coating-lambda-arta.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- van Nijnatten, P. An automated directional reflectance/transmittance analyser for coating analysis. Thin Solid Films 2003, 442, 74-79. [CrossRef]

- Agilent Cary 7000 universal measurement spectrophotometer, Available online: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/brochures/5991-2392EN.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- PHOTON RT Brochure. Available online: https://www.essentoptics.com/f/file/Essentoptics_PHOTON_RT_2025-10_1.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Macleod, A. Thin Film Polarizers and Polarizing Beam Splitters. JVC Summer Bull. 2009, 24–29.

- Gerhardt, U. and Rubloff, G. W. A Normal Incidence Scanning Reflectometer of High Precision. Appl. Opt. 1969, 8, 305–308. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J. E. and Blevin, W. R. Instrument for the Absolute Measurement of Direct Spectral Reflectances at Normal Incidence. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1964, 54, 334–336. [CrossRef]

- Ram, R.; Prakash, O.; Singh, J. and Varma, S. Absolute reflectance measurement at normal incidence. Optics & Laser Technology 1990, 22, 51-55. [CrossRef]

- Bittar, A. and Hamlin, J. D. High-accuracy true normal-incidence absolute reflectometer. Appl. Opt. 1984, 23, 4054–4057. [CrossRef]

- Stemmler, I. Angular dependent specular reflectance in UV/Vis/NIR. In: SPIE International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2005, 59651G.

- Strong, J. and Neher, H. Procedures in Experimental Physics; Prentice-Hall, Incorporated, 1938.

- Castellini, C.; Emiliani, G.; Masetti, E.; Poggi, P. and Polato, P. P. Characterization and calibration of a variable-angle absolute reflectometer. Appl. Opt. 1990, 29, 538–543. [CrossRef]

- Francois, J. C.; Chassaing, G. and Pierrisnard, R. Measurement of absolute reflectance at nearly normal incidence. Journal of Optics 1982, 13, 207–208. [CrossRef]

- Pointeau, F. Mesure absolue des coefficients de réflexion. Nouvelle Revue d'Optique Appliquée 1972, 3, 103. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y. and Lu, M. Evaluate thin film surface roughness accurately by a simple x-ray reflectivity distribution method and first-order perturbation theory. In: Proc. SPIE 10750, Reflection, Scattering, and Diffraction from Surfaces VI, 107500L (4 September 2018), 107500L. [CrossRef]

- Rieser Jr, L. M. Reflection of X-rays from condensed metal films. Journal of the Optical Society of America 1957, 47, 987-994.

- Jiang, Y.; Pillai, S. and Green, M. A. Realistic Silver Optical Constants for Plasmonics. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 30605. [CrossRef]

- Raether, H. Surface plasmons on smooth and rough surfaces and on gratings; Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Zayats, A. V.; Smolyaninov, I. I. and Maradudin, A. A. Nano-optics of surface plasmon polaritons. Physics Reports 2005, 408, 131-314. [CrossRef]

- Röseler, A. Spektroskopische Infrarotellipsometrie. 1996, 89–130. [CrossRef]

- Lyddane, R. H.; Sachs, R. G. and Teller, E. On the Polar Vibrations of Alkali Halides. Phys. Rev. 1941, 59, 673–676. [CrossRef]

- Harbecke, B.; Heinz, B. and Grosse, P. Optical properties of thin films and the Berreman effect. Applied Physics A Solids and Surfaces 1985, 38, 263–267. [CrossRef]

- Berreman effect. Available online: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berreman-Effekt (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Schubert, M. Infrared Ellipsometry on Semiconductor Layer Structures Phonons, Plasmons, and Polaritons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany 2005.

- Ohlídal, I., Vohánka, J., Čermák, M., Franta, D. Ellipsometry of Layered Systems. 2018, In: Stenzel, O., Ohlídal, M. (eds) Optical Characterization of Thin Solid Films. Springer Series in Surface Sciences, Vol. 64. Springer, Cham, 233–267. [CrossRef]

- Flory, F.; Escoubas, L. and Berginc, G. Optical properties of nanostructured materials: a review. Journal of Nanophotonics 2011, 5, 052502. [CrossRef]

- Razskazovskaya, O.; Luu, T.T.; Trubetskov, M.; Goulielmakis, E. and Pervak, V. Non-linear absorbance in dielectric multilayers. Optica 2015, 2 (9), pp. 803 – 811.

- Amotchkina, T.; Trubetskov, M.; Fedulova, E.; Fritsch, K.; Pronin, O.; Krausz, F.; Pervak, V. Characterization of Nonlinear Effects in Edge Filters. In Proceedings of the Optical Interference Coatings (OIC), Tucson, AZ, USA, 19–24 June 2016. Paper ThD.3.

- Stenzel, O. and Wilbrandt, S. Theoretical study of multilayer coating reflection taking into account third-order optical nonlinearities. Applied Optics 2018, 57, 8640–8647. [CrossRef]

- Wilbrandt, S.; Stenzel, O. Third-Order Optical Nonlinearities in Antireflection Coatings: Model, Simulation, and Design. Modelling 2025, 6, 48. [CrossRef]

| Step | Quantity | |||

| Sample beam | Reference beam | |||

| 1 | „Auto zero” | „100%“ | ||

| „0%“ | ||||

| 2 | Measurement | Sample | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).