1. Introduction

M-lines spectroscopy is a non-destructive, contactless and highly accurate technique to optically characterize dielectric thin films. Its main functionality is to determine with high precision two fundamental parameters of a given thin layer of material deposited over a substrate: - The refractive index and thickness of the deposited film. This method has found applications in industry and academia, with recent increasing adoption by the former, especially where rigorous and precise characterization of dielectric films is a requirement. Follows examples of applications in industry:

-

Photonic Integrated Circuit manufacturing

-

o

Stakeholders: - Silicon photonics, optical sensors and telecommunications industries;

-

o

Industrial motivation: - Enables minimal tolerances over optical and dimensional parameters, thus improving overall coupling efficiency;

-

Coatings quality control

-

o

Stakeholders: - Laser components, high precision optics and photolithography;

-

o

Industrial motivation: - Refractive index and thickness validation of anti-reflection and highly protective coatings, and dielectric mirrors;

-

Microelectronics and semiconductors manufacturing

-

o

Stakeholders: - Micro-electro-mechanical systems, sensors and optoelectronics industries;

-

o

Industrial motivation: - Allows non-destructive analysis of dielectric layers deposited over semiconductor substrates and contactless inspection of layer parameters during or after deposition;

-

Functional glass manufacturing

-

o

Stakeholders: - Construction, auto and ultra-violet to infrared protection industries;

-

o

Industrial motivation: - non-destructive characterization of solar protective, electrically conductive, hydrophobic, anti-flare and multilayer films on dielectric substrate.

Developments of the m-lines spectroscopy method, as originally established by seminal work of Tien et al. in 1969 [

1], have also taken place through academic research in more recent years. Approaches considering the application of numerical methods to include multilayer heterostructures, multiwavelength and new methods for data analysis, have also been proposed by Schneider et al. [

2] where it is claimed the development of an equation for the simultaneous extraction of the refractive index and thickness of a three layer system, and Wu et al. [

3] with a multiwavelength m-lines spectroscopy system with claimed advantages for the identification of refractive index profiles and dispersion.

This method bases its functionality on the excitation of the allowed propagation modes in a thin film. To achieve this, the modes propagating in the thin film couple into the incoming electromagnetic (EM) radiation through a coupling prism. Each of the allowed modes in the thin film couples into the EM radiation in the prism at a specific incoming angle, which corresponds to an interference dip in the reflection intensity graph produced by a monitoring photodetector. The incident angles

on the prism’s edge, at which propagating modes are excited, refract towards the base and then reflected. Once these angles are known, it is possible to obtain the angles

incident at the base of the prism through Snell’s law, and the modal index (

) of the excited mode is given by [

4]:

where

is the prism’s refractive index. The relation between the modal index of the propagating mode and its wavenumber (

) is:

where

is the free space wavenumber.

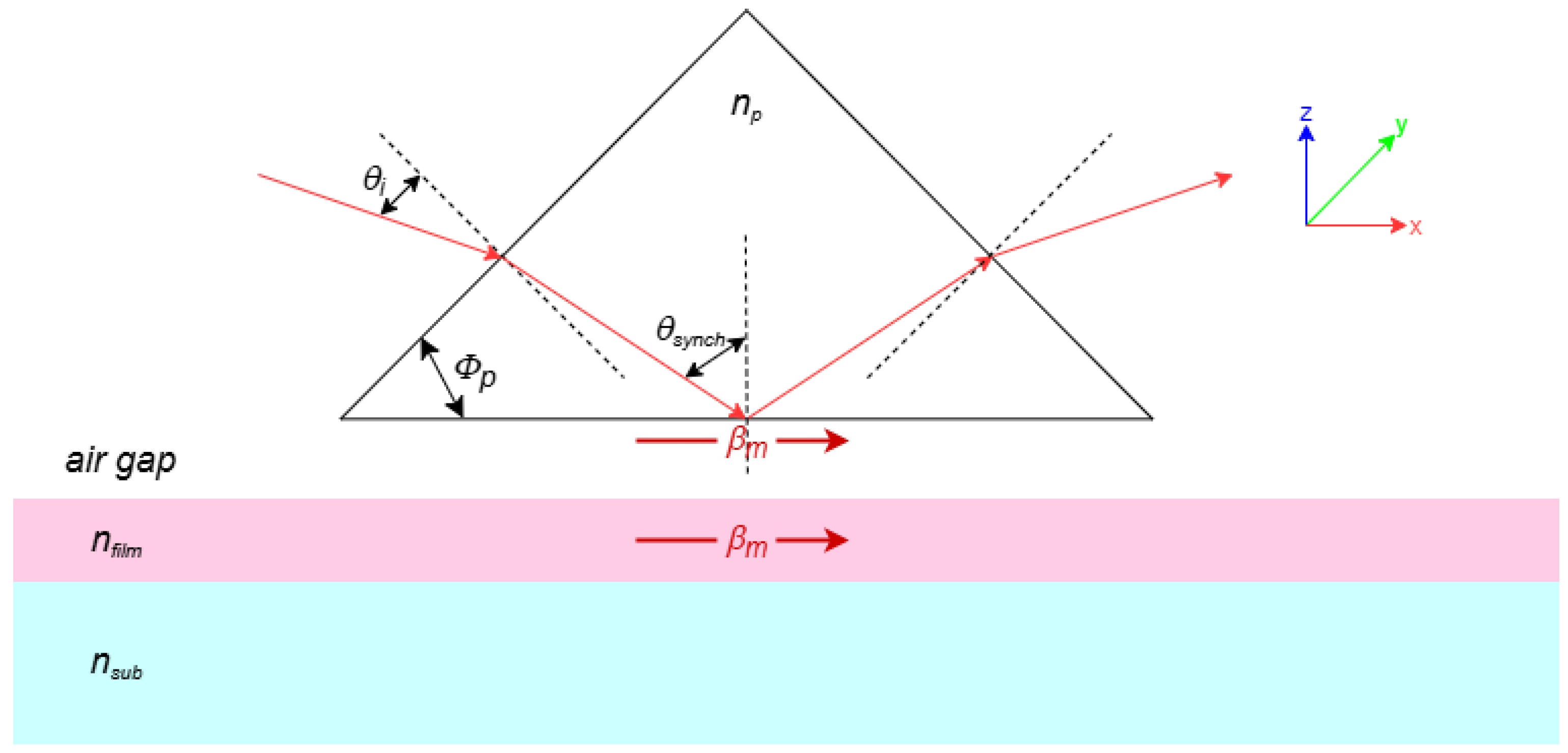

Figure 1 presents a diagram depicting the conservation of energy over the wavenumbers of the evanescent and propagating waves and the working principle of the method.

The method bases its functionality in the Frustrated Total Internal Reflection (FTIR) principle [

5], which consists of the evanescent coupling of a given mode propagating in the thin film into the wave totally reflected at the prism’s base. Being an evanescent wave, the excitation of a given propagating mode requires close proximity between the thin film and the prism’s base. To achieve this, we use a pressure gauge to slightly deform the sample at the point of application of the force, hence diminishing the existing air gap between the prism’s base and the thin film, and enable evanescent mode coupling. Furthermore, the resonant angles incident at the prism’s edge

(the ones measured) and the modal index of the excited modes are related by equation:

where

and

are the refractive index, and the internal angle formed between the base and the edge of the prism, respectively,

is the refractive index of the air gap and

the incident angles at the prism’s edge that excite propagating modes in the thin film.

Once we identify coupling features in the reflectance spectrum, the synchronous angles

can be calculated using Snell’s law, for the corresponding incident angles at the prism interface

- associated with each guided mode resonance - are now precisely known. This information, together with the knowledge of the modal indexes of the propagating modes in the thin film, allows determining the refractive index of the thin film layer by solving the following transcendental modes equation:

where

is the wavenumber dependent effective width of the thin film (including the wave’s penetration in both substrate,

, and cladding,

, due to the Goos-Hänchen effect [

6]) and

is the actual width of the layer.

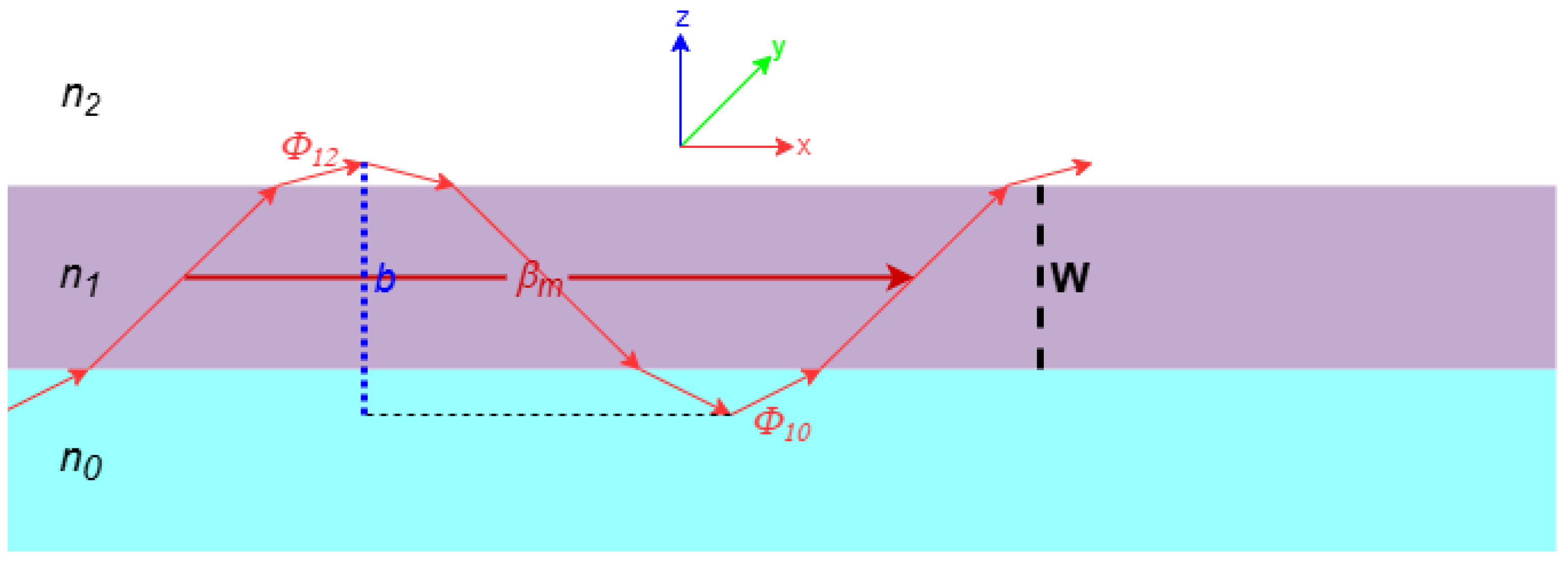

Figure 2 depicts a diagram of the phase evolution of the propagating mode as it progresses in the thin film.

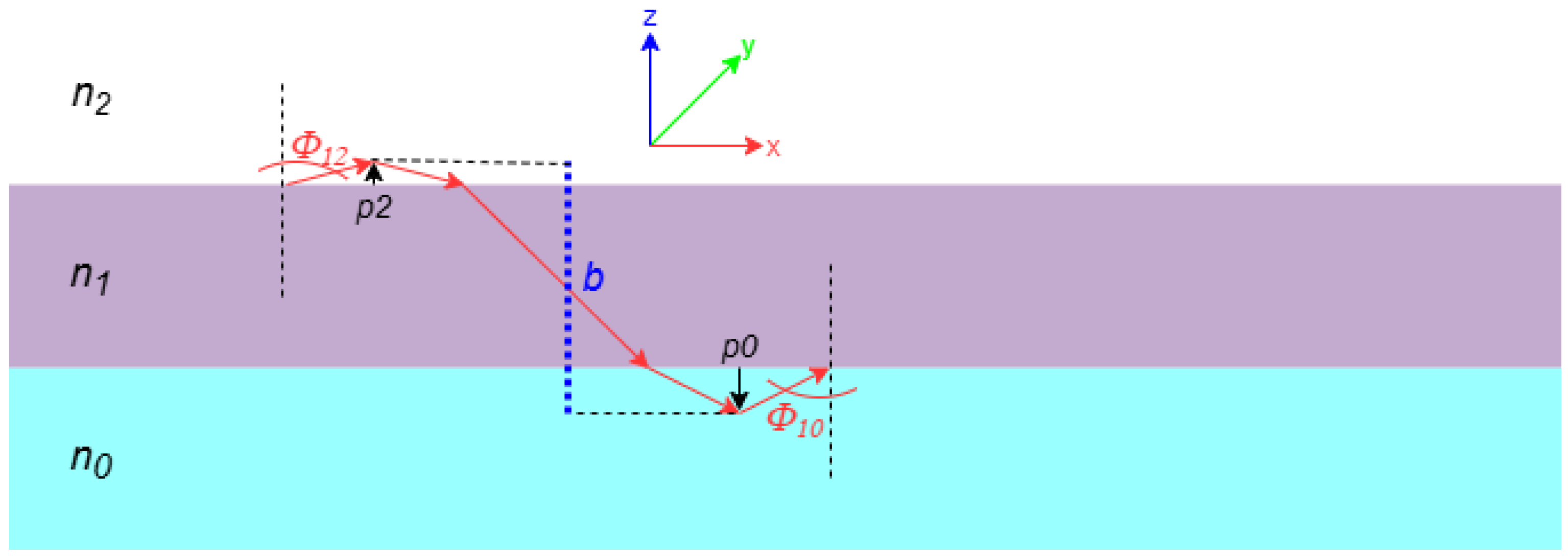

By examining

Figure 3, the terms on the left hand side of Equation (4) can be further represented by the following expressions, where

is the vacuum wavenumber, and

and

are the refractive index and the wavenumber of the thin film, respectively:

For perpendicular (free space propagation) [

1] and Transverse Electric (TE - assuming propagation along the X-axis and non-vanishing

,

and

field components in the thin film) polarization, we may write:

For parallel (free space propagation) [

1] and Transverse Magnetic (TM - assuming propagation along the X-axis and non-vanishing

,

and

field components in the thin film) polarization, the wave’s penetration either in the substrate and in the cladding (air), may be written as:

We have now all required to express Equation (4) with known quantities with the exception of the unknown

(thin film refractive index) and

(thin film width) variables. After replacing the terms in Equation (4) by the corresponding expressions in Equations (5)–(11) and algebraic simplification, we obtain the following equations according to polarization:

These are two variables transcendental equations and not easy to solve through analytical methods. The usual way of solving these equations is by eliminating the width (

) variable by operating a division between two equations, each resulting from the expression obtained when considering two different modes of the same polarization. For instance, when considering TE polarization and the modal indexes of the fundamental (

) and first (

) propagation modes:

Similarly, when considering TM polarization and the modal indexes of the fundamental (

) and first (

) propagation modes:

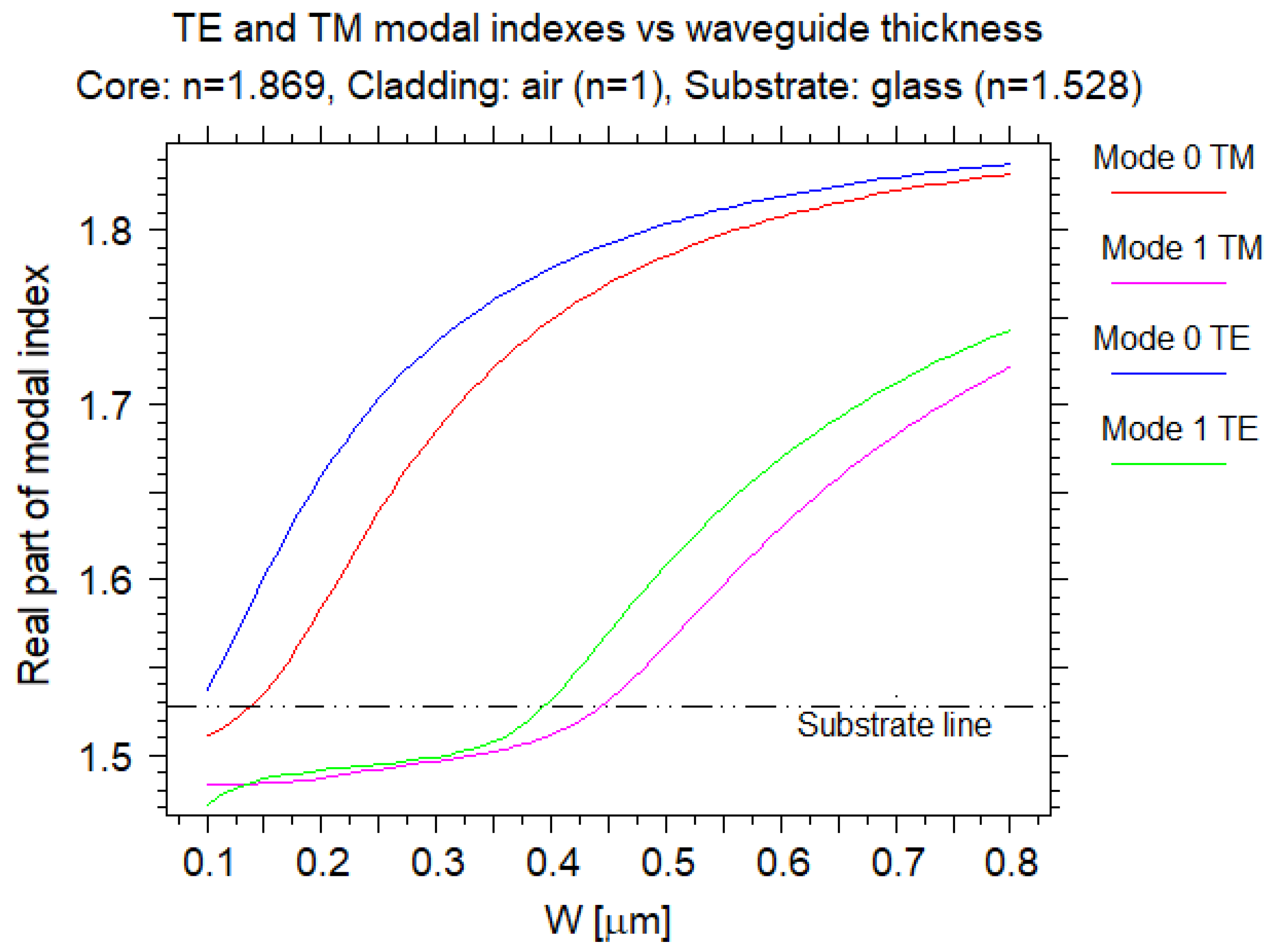

Hence, it has been claimed throughout the years [

3,

7,

8,

9,

10] this method requires at least the knowledge of two modal indexes of the same polarization to unequivocally determine its refractive index and thickness, which imposes dimensional constraints in the waveguide’s parameters calculation. To illustrate this, we assume a usual asymmetric thin film deposited over an optical glass substrate with 1.8 and 1.528 refractive indexes, respectively, and plot the allowed modes as a function of the thickness of the waveguide, for a given excitation wavelength. We used FemSIM from RSoft [

11] to calculate the excited modes and as can be observed in

Figure 4, the first modes start being excited when the width of the thin film is above 400 nm, more precisely at ~400 and ~450 nm for TE and TM modes, respectively. Thus, since m-lines spectroscopy requires at least two modes of the same polarization to solve Equation (15), this technique is limited to ~400 nm thick thin films for reliable measurement, considering the asymmetric thin film configuration depicted in

Figure 4.

In this work, we use the m-lines spectroscopy method to determine the refractive index and thickness of asymmetric thin films, by solely utilizing the fundamental mode of each polarization (TE

0 and TM

0) to compute the intended parameters of the deposited film. This way, we avoid the thickness constraint imposed by the two modes of the same polarization requirement for reliable computation, and we are now able to calculate these parameters for much thinner films, only limited in thickness by the degree of asymmetry of the thin film. Namely, and returning to the thin film configuration depicted in

Figure 4, calculation is still limited by the refractive index of the substrate, only this once by the TM fundamental mode instead of the first mode (W > ~150 nm).

In the next section, 2. Materials and Methods, we present the implemented optical setup with a thorough description of its constituents. Follows section 3. Results, where we report our findings and describe all steps and actions performed in this research work. Finally in section 4. Discussion, we present a critically aware assessment of this research work and its findings, discuss our conclusions and define future work directions.

3. Results

We started this research work with a sample consisting of an AF45 glass substrate [

12], with the thin film deposited on the substrate through Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition. The fabrication conditions, deposition and characterization details of the selected silicon carbonitride sample (Si

2C

2N

6) are described elsewhere [

13]. We used this sample to test, verify and confirm the validity of our hypothesis: - The limit in the m-lines spectroscopy method is the thickness necessary to propagate the fundamental modes of both polarizations, Transverse Electric (TE

0) and Transverse Magnetic (TM

0).

Using the m-lines spectroscopy optical setup with the Si

2C

2N

6 sample loaded on, we observed the reflectance versus incident angle

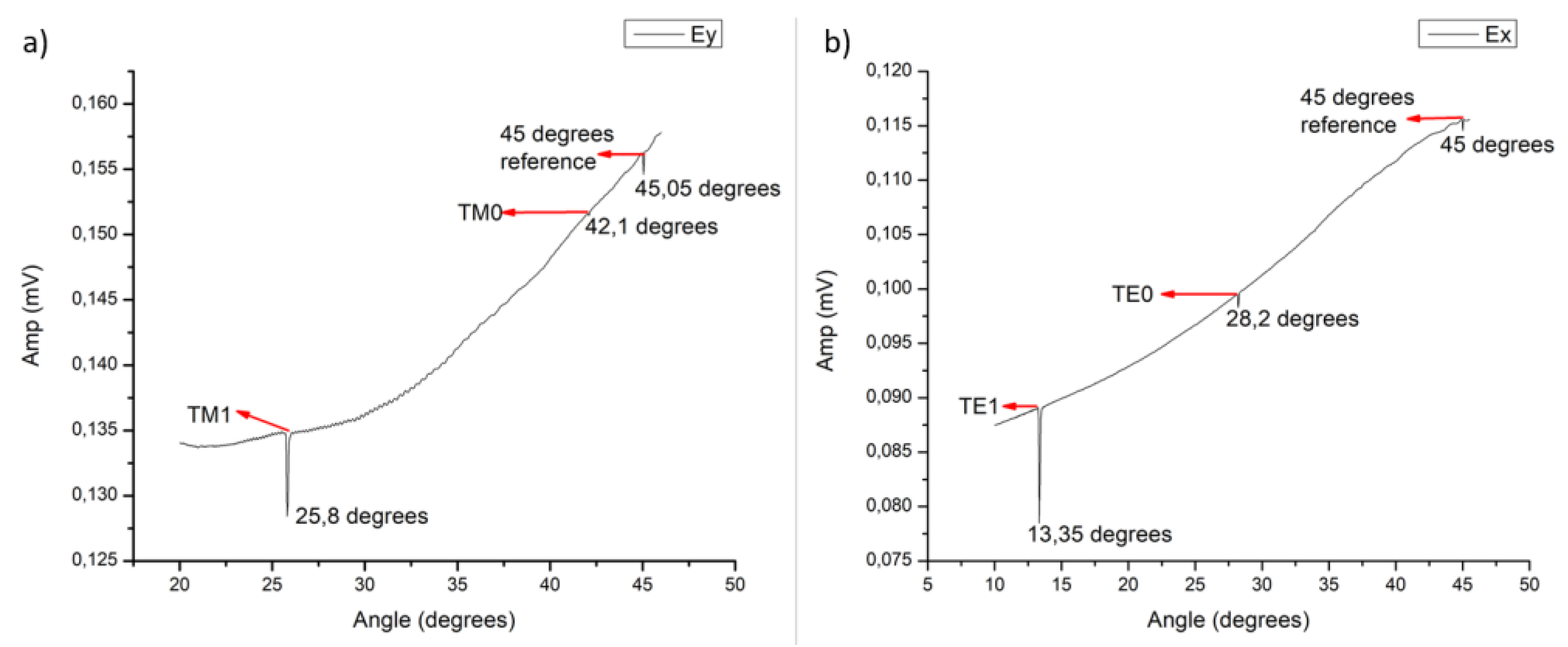

as presented in

Figure 6:

We obtained these results with an angular step of 0.05°, at the operating wavelength of 655 nm provided by an off-the-shelf laser diode and a polarizer placed in the optical beam path, between the laser diode and the prism. In both graphs of

Figure 6, one is able to identify three dips corresponding, from right to left, to the interference of the returning laser beam when at normal incidence on the prism’s edge, which we use as our 45° reference, and to the modes which have been excited in the film. Depending on how the goniometer rotates anti- or clockwise, the measured angles may have to be subtracted from 90°; such happened in this case.

Equation (3) returns the modal indexes of the excited modes (

), given the incident angles at the prism’s edge (

) and corresponding synchronous angles (

). Since these are known quantities, we are now able to solve numerically Equation (4) and determine the refractive index and thickness of the film, as long as the refractive indexes of the substrate, air gap and prism are known. Before proceeding with calculations, let’s examine further dispersion Equation (4) considering the analysis initiated by Tien [

14] and further pursued by other researchers [

15,

16]: - Simply put, Equation (4) is thought to be incomplete, for it does not consider the prism’s influence on a given propagating mode in the film.

In fact, by analysing the terms on the left hand side of Equation (4), one finds, from left to right, a term related to the width of the film (

) and the terms related to the field’s penetration in both substrate (

) and superstrate (

). These terms are further algebraically simplified, resulting in Equations (14) and (15) for TE and TM modes, respectively, and the influence of the prism remains absent, not accounted for in these equations. The same is true even graphically in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, where the presence of the prism has been coherently removed. As such, the solution found by Equations (14) and (15) should reflect the calculation of the film’s refractive index, when accounting for TE and TM modes with a semi-infinite air superstrate. Hence, the obtained modal indexes are real-valued propagation constants, corresponding to propagating modes confined in the film. Then, we derive the film’s thickness through the just calculated refractive index.

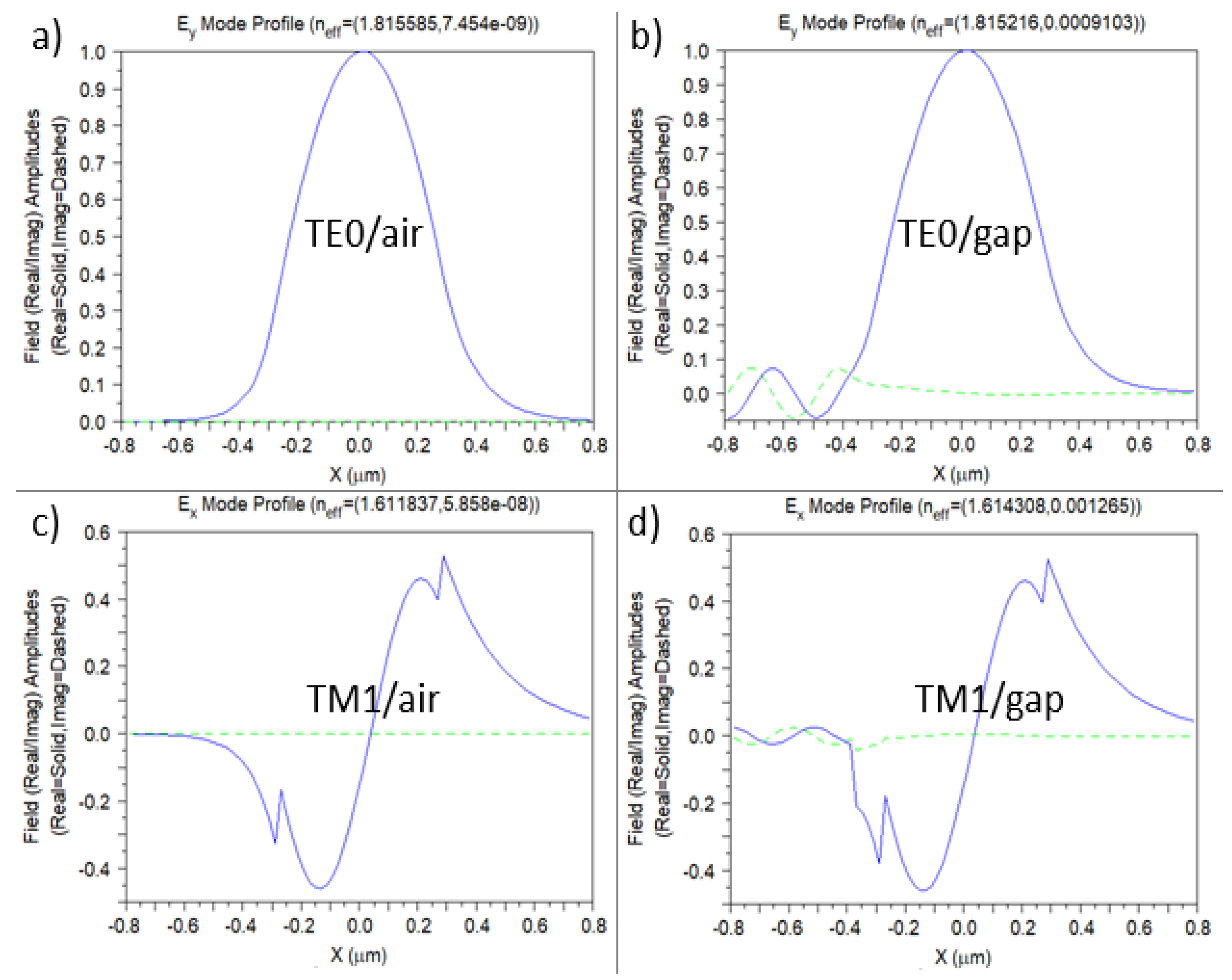

We investigated further the modal indexes of a given structure with the FemSIM mode solver, assuming 572 nm and 1.869004116 for the thickness and refractive index of the silicon carbonitride film, with two different structure configurations:

- -

Semi-infinite substrate/thin film/semi-infinite airgap;

- -

Semi-infinite substrate/thin film/airgap/semi-infinite prism.

Figure 7 shows the amplitude profiles and corresponding modal indexes of representative results obtained with the mode solver (propagation is along the Z-axis and film confinement along the X-axis in FemSIM, thus the electric field designations associated to TE/TM are opposite the convention used in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), followed by

Table 1 with the values returned by the mode solver of the excited modes in the film.

It is notorious the difference in the amplitude profiles between the modes calculated by the mode solver with semi-infinite air superstrate and with 100 nm airgap/semi-infinite prism. The modes of the latter show field leakage through the gap and into the prism. This is further confirmed by comparing the imaginary components of the modal indexes when the superstrate is semi-infinite air or airgap/semi-infinite prism. The former modes are essentially film confined modes, while the latter are leaky modes. Moreover, the real components of the modal indexes, when comparing the same mode order of each configuration, are not equal and impact the results returned by dispersion Equation (4) when calculating the refractive index and thickness of the film.

To fully model this system and account for the accumulated phase through the gap, we must replace in the classic dispersion equation the term related to the phase in the air gap (

), by the one representing the effective phase of the prism/gap system (

):

This may be achieved by looking at the system gap/prism as a transmission line, considering normalized admittances:

, for TE polarization;

, for TM polarization.

where

,

is the refractive index of either gap or the prism and

is the free space wavenumber. As such, the input admittance seen by the film towards the prism is:

where superscript

stands for polarization TE/TM, and subscripts

,

and

, stand for superstrate, gap and prism, respectively. To recover the accumulated effective phase, we may use:

, for TE polarization;

, for TM polarization.

However, this strategy is air gap dependent, for variable incorporates the term and is the not known air gap thickness. Nevertheless, we have implemented and tested this solution, but the results obtained were slightly worse than the ones obtained when solving the classical dispersion Equation (4). As such, this strategy was abandoned, and we proceeded focusing our research on the analysis of the results obtained with Equation (4).

Next and using the angles experimentally obtained and presented in

Figure 6, and dispersion Equation (4), the film’s calculated refractive index and thickness are presented in

Table 2:

As may be observed in

Table 2, there is a differential between the TE and TM calculated values, namely

and

for the refractive index and thickness, respectively.

We then evaluated the impact of angular resolution on the obtained results. To this end, we analyzed once again the silicon carbonitride film sample, only this time with a finer resolution of 0.01 degrees.

Table 3 shows all the pertaining information, from the resonant angles to the calculated refractive indexes and thicknesses, in both TE and TM polarizations:

From

Table 3 we notice a change in the differential between the TE and TM calculated values, being now

and

for the refractive index and thickness, respectively. The greater resolution assured a smaller difference in the TE and TM calculated thicknesses, although there’s a slight increase in the refractive index differential.

With previous thought in mind, we analyzed once more the silicon carbonitride sample with an even greater angular resolution, 0.001 degrees. This was the only occasion we performed an analysis at such a fine resolution, for when one knows nothing about the film’s thickness and refractive index, it is good practice to scan a wide range of angular positions (10 to 80 degrees). However, this is a lengthy process at an angular step of 0.001 degrees. The results obtained are presented in

Table 4:

The difference between TE and TM values has decreased significantly, reaching now and . Moreover, there is an evident trend of a diminishing differential as the angular resolution of our goniometer increases and an inversion of the sign of the results, which suggests there should be a minimum where the derivative of each differential reaches zero. Plus, by following the behavior of the refractive index as the angular resolution increases, one notices that TE and TM are affected differently. The TM calculated refractive index presents greater variation, while TE values are more stable.

Another constraint affecting the concordance of TE and TM calculated refractive indexes, and which has been referred to in the literature [

17], is the force applied to approximate the substrate to the prism and favor coupling. As the exerted force is increased, the coupling resonances are widened and shifted, hence care must be taken to avoid these issues.

Previous analysis is in line with the fact that there is only one refractive index of the film deposited on the glass substrate, despite the calculation process involving TE or TM dispersion related equations. As such, the actual film’s refractive index must be the one that is better approximated by the results obtained by both TE and TM calculations. With this in mind, we have executed once more the process of determining the refractive index and thickness of our film, only this time we used just the fundamental modes to solve the dispersion equations. By solely utilizing TE

0 and TM

0 to calculate the intended parameters of the deposited film, we are now able to calculate the refractive index and thickness of thinner films (W > ~150 nm). This may be concluded by inspecting the graph depicted in

Figure 4, where the limit is now imposed by the intersection between the TM fundamental mode and the substrate line instead of, as previously, between the substrate line and the first TM mode.

Equation (19) has been used to calculate the optical-geometric parameters and

Table 5 presents the results obtained:

As can be observed in

Table 5, this calculation scheme produces a single value for the refractive index and the TE/TM thickness differential is the smallest one so far,

. We believe these are the closest to physical refractive index and thickness values, since it presents the smallest differential, but also because the calculation relies on the TE and TM fundamental modes. Fundamental modes present the highest modal index of any propagating mode in a given film, which means their propagating path is the closest to the guide’s center, hence less prone to the influence of the prism’s medium proximity. We assured the least possible exerted force on the backside of this sample, thus previous assumption regarding our measurements being the closest possible to physical reality of the sample.

4. Discussion

We started this research work to evaluate the possibility of extending the measurement range of the m-lines spectroscopy method. To this end, we conducted a series of analyses of increasing resolution on a silicon carbonitride film deposited over a glass substrate. Each analysis considered finding the optical-geometric parameters of the film under test, namely the refractive index and thickness. To determine these parameters, we considered initially the calculation strategy that has been reported throughout the years in the literature, since the seminal work of Tien et al. [

1]: - The method requires two modes of the same polarization to solve the transcendental equations.

By using transverse electric and magnetic Equations (14) and (15), we are able to obtain two pairs of parameters, one for each polarization, which we can compare. Ideally, since there is only one film, both calculations should present the same result for each parameter, but experimental results are hardly ideal. However, as we increased the angular resolution in the optical setup, we noticed a decreasing trend of the refractive index and thickness differentials when comparing parameters of both polarizations. The obtained differentials for an angular resolution of 0.001° were and . Next, with the same data as before and using the fundamental modes of each polarization, we determined a thickness differential of . Not only is this the lowest differential obtained, but by determining the optical-geometric parameters with the fundamental modes, we are able to extend the range of application of the m-lines spectroscopy method to thinner films, as it is the intent of this research work.

Further work will consider the physical verification of the results obtained. To this end, we intend to fabricate a sample that will provide access to a high precision measuring system (e. g. atomic force microscopy) to determine the film’s thickness, while still allowing probing by the m-lines spectroscopy method, and confirm whether or not this strategy is valid.