1. Introduction

The Urbanisation is one of the defining processes of the 21st century, transforming landscapes, ecosystems, and human livelihoods. Global projections estimate that nearly 68% to 70% of the world´s population will reside in urban areas by 2050, a demographic transition expected to impose unprecedented pressures on natural ecosystems and accelerate the reduction of urban green cover [

1,

2]. These dynamics, combined with climate change, ecological degradation, and declining environmental quality, pose significant challenges to sustainable urban development.

The progressive loss of urban green spaces in cities has profound ecological and social implications, as it weakens essential ecosystem services that support urban resilience, human well-being and public health. Empirical studies have shown that limited access to urban green space is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including higher levels of psychological distress, lower self-perceived well-being, and even increased mortality rates [

3,

4,

5].

In this context, urban parks, gardens, and other green spaces are increasingly recognised as essential components of sustainable cities. They provide multiple ecological, social, and health benefits, including improved air quality, noise reduction, mitigation of the urban heat island effect, biodiversity conservation, and opportunities for recreation and mental well-being [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Beyond these immediate benefits, urban green spaces also serve as vital ecological infrastructure that regulates microclimates, strengthens resilience against natural hazards, encourages social cohesion, and promotes inclusivity by offering accessible environments for diverse populations [

2,

7,

8]. As these spaces are often perceived as safe environments for leisure, play, and even food production, their protection and sustainable management are indispensable for reconciling rapid demographic and spatial expansion with the preservation of ecological functions and the promotion of human well-being [

10].

Despite their recognised social and ecological value, urban green spaces are not immune to environmental risks. Urban soils often act as long-term sinks for contaminants introduced through anthropogenic activities, with potential implications for environmental quality and public health [

11]. Their diversity largely reflects human interventions, including the historical use of leaded gasoline, industrial activities such as smelting, waste recycling and disposal practices, among others. Additional sources arise from the application of lawn care chemicals and the former use of pressure-treated wood in playgrounds. At the same time, vegetation in parks and gardens facilitates the capture of atmospheric deposition, thereby contributing to the accumulation of pollutants in soils [

12,

13]. However, such contamination is often overlooked. This is of particular concern because these areas are frequented by vulnerable groups, including young children and the elderly, who may be more susceptible to adverse health effects [

13].

Among the different classes of contaminants identified in urban soils, persistent organic pollutants are particularly concerning due to their extreme persistence, strong bioaccumulative potential, and severe toxicological impacts. These compounds are regarded as some of the most hazardous environmental pollutants due to their widespread historical application, chemical stability, and permanent ecological and health implications. This group includes organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), hexachlorobenzene (HCB), and toxaphene, along with industrial compounds like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), as well as unintentional by-products of combustion processes, including polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs). Their physicochemical properties explain their environmental persistence: they are highly stable, resistant to physical, chemical, and photochemical degradation, and therefore challenging to remove once released into ecosystems [

14,

15,

16]. In addition, their lipophilic nature promotes accumulation in the fatty tissues of living organisms, leading to biomagnification along food webs and resulting in elevated concentrations at higher trophic levels [

17]. These same properties enable long-range atmospheric transport, allowing POPs to cross geographic boundaries and contribute to global environmental contamination [

18,

19,

20]. Although international conventions have restricted or banned many of these compounds, residues of POPs continue to be detected across all ecological compartments. In urban soils, particularly in parks and gardens, this persistence translates into chronic, low-level exposures for human populations, a dimension that remains poorly quantified, highlighting growing risks to ecosystem integrity and public health [

9].

Research has demonstrated that POPs can act as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormonal regulation and reproductive processes, and have been linked to increased risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and immune system dysfunction [

21,

22]. Long-term exposure, even at relatively low concentrations, has also been associated with neurotoxic effects and impaired cognitive development, with fetuses and children identified as particularly vulnerable groups [

23,

24]. Despite their well-documented toxicity, studies specifically addressing exposure scenarios in urban parks remain limited, with most risk assessments focusing on agricultural or industrial soils rather than recreational environments. Notably, most studies have focused on heavy metals, while systematic investigations of POPs in these environments remain scarce, revealing a critical gap in current knowledge.

In urban environments, the soils of parks and gardens represent an important, though often ignored, route of human exposure to POPs. Relevant routes include incidental ingestion of soil and dust, dermal absorption, inhalation of resuspended particles, and, in the case of urban agriculture, dietary intake of food crops grown in contaminated soils [

13,

25,

26]. Such pathways are of particular concern for people who regularly use parks, as their repeated exposures may increase the risk of adverse health effects, including endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity, immune dysfunction, and even cancer. Importantly, urban parks bring unique exposure dynamics compared to other land uses, since they combine high ecological value with intensive human contact. This duality increases both their importance and their vulnerability.

Although POPs in urban green spaces clearly pose environmental and public health concerns, current research remains inconsistent, with studies varying widely in geographic focus, contaminant classes investigated, and methodological approaches. This lack of coherence limits our ability to understand the accurate scale of the problem thoroughly and to develop effective responses. Thus, there is an urgent need for an integrated perspective that not only consolidates existing evidence but also identifies critical gaps, particularly regarding the occurrence, behaviour, and health risks of POPs in park soils.

The present review seeks to address this need by providing a structured synthesis of the occurrence, sources, environmental behaviour, and associated risks of POPs in soils of urban parks and gardens. Additionally, it examines international legislation and regulatory frameworks, evaluates potential mitigation and management strategies, and highlights priorities for future research. In this way, this review aims not only to summarise existing knowledge but also to reconsider urban parks as paradoxical spaces, both critical components of sustainable urban systems and repositories of environmental pollutants, thus advancing both scientific understanding and the foundations for evidence-based urban ecological management.

2. Urban Parks and their soils

2.1. Functions and Diversity of Urban Parks

Urban parks and gardens are among the most accessible and valued green spaces in modern cities, offering ecological, social, and cultural benefits that are essential for sustainable urban living. They exist in diverse forms, including recreational grounds, domestic gardens, cemeteries, cultivated areas, spontaneous or intentionally created woodlands, roadside vegetation, and abandoned land, all of which collectively contribute to the ecological balance and community structure of urban environments [

7,

8].

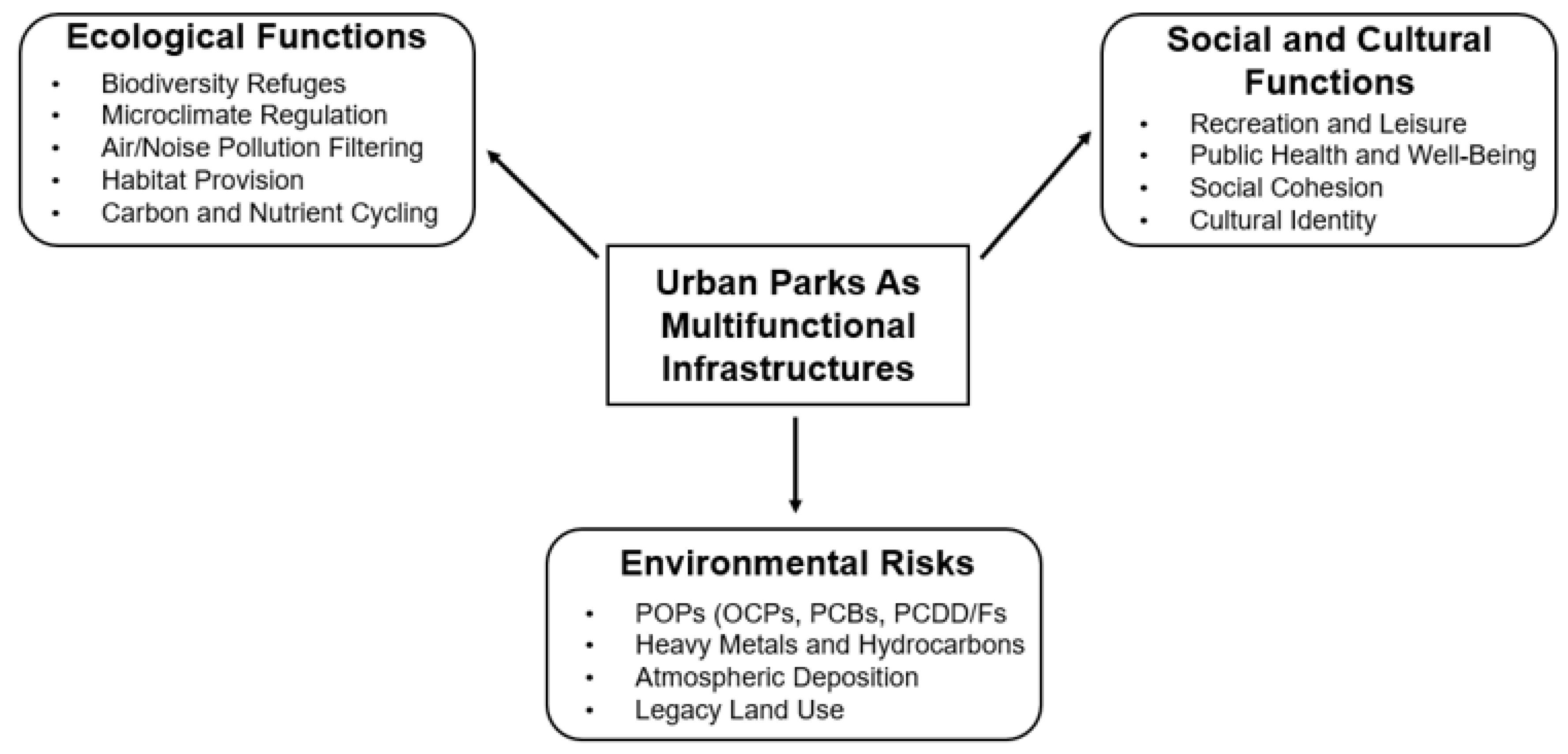

In addition to this diversity of forms, urban parks fulfil a dual role in modern cities: on one hand, they provide opportunities for leisure, recreation, and social interaction, strengthening community ties and supporting both physical and mental health [

6,

7,

8,

9]. On the other hand, they function as ecological refuges, offering a variety of functions that sustain and preserve biological diversity within heavily urbanised surroundings [

27]. This multifunctionality reinforces their importance not only as recreational landscapes but also as critical elements of urban ecological infrastructure.

In this sense, urban parks serve as both places for social life and community interaction, and as refuges for biodiversity, providing habitats for species that might otherwise disappear from urbanised environments. They help regulate microclimates, filter air and noise pollution, and create spaces for cultural expression and civic life [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Their value is not only in what is visible, such as trees, lawns, or flowerbeds, but also in the less visible foundations: soils, vegetation, and design choices that together determine how effectively parks can deliver ecosystem services (

Figure 1).

At the same time, this multifunctionality of the parks makes them vulnerable to anthropogenic pressures. Emissions from traffic, industrial residues, and traces of past land use can leave marks on their soils and vegetation. In fact, parks may also serve as reservoirs of a wide variety of contaminants such as heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and POPs.

Recognising this duality is essential. Urban parks are recognised as integral to sustainable urban living, indispensable for human well-being and ecological resilience. At the same time, they may also act as reservoirs of contamination, functioning as potential entry points for environmental pollutants, including POPs.

2.2. Soils as Foundations of Ecosystem Services and Contamination Sinks

The ecological functions of urban parks are supported by soils whose properties are highly heterogeneous, reflecting both natural processes and the cumulative effects of human activities. Unlike agricultural or forest environments, urban park soils are frequently disturbed, transformed, or enriched with artificial materials during their creation and management, leading to unique physical, chemical, and biological characteristics [

1,

28]. These soil characteristics are influenced not only by vegetation and landscape design, but also by the history of land use and the intensity of current human activities. Such influences determine how compacted or well-drained the soils become, how much organic matter they retain, and the extent to which they accumulate contaminants [

29].

A key characteristic of urban park soils is the presence of technogenic materials, resulting from past land-use and construction activities. These materials, combined with the primary parent geological substrate, form unique spatial and vertical distributions that amplify the heterogeneity of urban soils, both in surface and deeper soil layers [

1]. Recent studies in Wuhan, China, have demonstrated strong correlations between soil heterogeneity and heavy metal accumulation in park soils [

30]. Meanwhile, Gruszka et al. [

31] showed that constructed technogenic soils in urban allotments can contain elevated levels of trace elements. These findings highlight how engineered materials do more than support vegetation; they actively condition the rate of contaminant accumulation. The way these materials are structured, the extent to which they differ from one another, and how easily they break down all play a significant role in shaping how soils function and their stability over time.

Table 1 summarises the primary ecological functions performed by urban park soils, highlighting their fundamental processes and their relevance to both ecosystems and human health.

Additionally, the incorporation of such materials can alter water flow and the migration of dissolved substances within the soil profile, potentially facilitating the transfer of contaminants into the soil, water and plant system [

1]. Similar patterns have been observed for organic pollutants: Duan et al. [

33] reported the combined accumulation of POPs and heavy metals in urban soils, reinforcing the risk of interactions between urban soil compartments and contaminant fluxes.

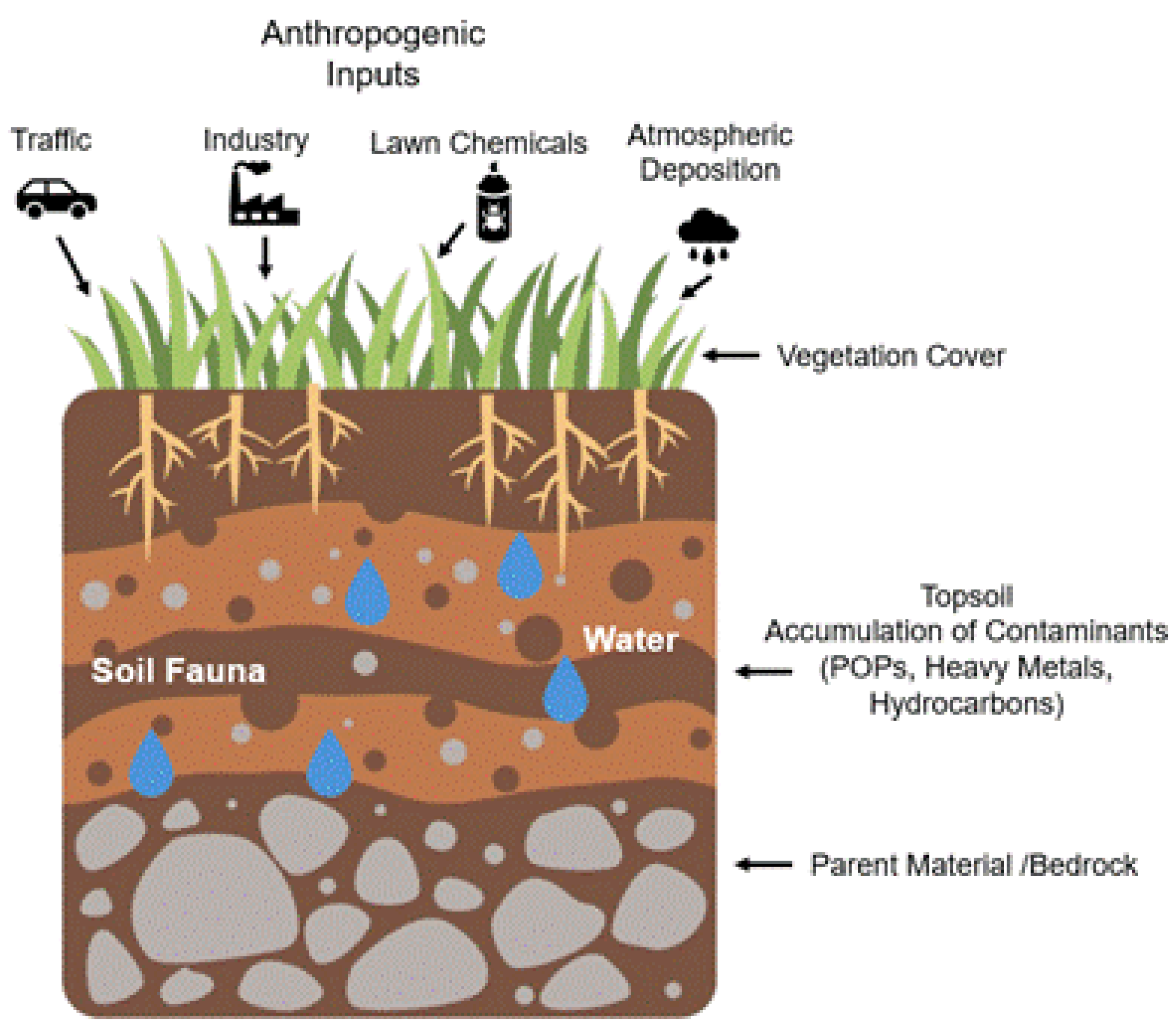

Vegetation plays a central role in regulating these conditions. By protecting the soil from direct solar radiation, plants help stabilise soil temperatures and reduce water loss through evaporation, thereby maintaining higher levels of moisture compared to bare surfaces. This microclimatic shielding supports soil fauna, which improve nutrient cycling and infiltration through their activity, improving soil structure and fertility [

27]. As a result, urban park soils support critical ecosystem services, including carbon and nitrogen sequestration, climate regulation, and water infiltration and purification [

32] (

Figure 2). However, the heterogeneity that makes these soils ecologically valuable can also affect pollutant retention and mobility, determining whether compounds such as POPs remain bound to organic matter or become more bioavailable for plant uptake and human exposure.

Understanding how the heterogeneity and ecological processes of urban soils influence contaminant persistence requires a multidisciplinary perspective that brings together urban ecology, environmental toxicology, and ecotoxicology. Such an integrated approach is crucial for understanding the complexity of interactions among pollutants, ecosystems, and human populations. It also reveals how human-modified soils function as both reservoirs and regulators of pollution, emphasising their potential as early indicators of environmental health within cities.

The following chapter provides a detailed examination of the properties, sources, and environmental behaviour of POPs, establishing the scientific basis for assessing their occurrence and associated risks in urban park soils.

3. Persistent Organic Pollutants

3.1. Definition and General Characteristics

Persistent Organic Pollutants are synthetic organic compounds that are highly resistant to environmental degradation through chemical, biological, and photolytic processes. This persistence enables them to remain in the environment for decades after their release, allowing them to undergo long-range atmospheric transport and accumulate far from their sources [

34,

35,

36]. Their molecular structure, which often includes halogen atoms such as chlorine, bromine, or fluorine, confers exceptional stability and lipophilicity, facilitating their accumulation in biological tissues and biomagnification along food webs [

37]. Due to these physicochemical characteristics, POPs are now detected in virtually all environmental compartments (air, water, sediments, and soils), as well as in biological tissues, including those of humans and wildlife, in remote regions such as the Arctic [

38,

39].

Four main characteristics define the environmental behaviour and toxicological relevance of POPs: persistence, bioaccumulation, mobility, and toxicity [

40]. Their resistance to degradation enables them to remain in soils and aquatic systems for extended periods. At the same time, their lipophilic nature promotes their accumulation in fatty tissues and biomagnification along food chains. With semi-volatile properties, POPs move continuously through the environment, circulating between air, water, and soil through repeated cycles of evaporation and deposition, which ultimately lead to their widespread global distribution [

39]. Even at low concentrations, many POPs exhibit pronounced toxic effects, acting as endocrine disruptors and immunotoxins, and impacting reproduction, development, and metabolic function [

40].

In urban contexts, these characteristics gain particular significance. Urban soils are highly heterogeneous systems influenced by both natural and anthropogenic factors, which can affect how POPs are retained, degraded, or mobilised. Consequently, the persistence of POPs in urban park soils, where frequent human contact occurs, poses a growing concern for environmental quality, ecosystem integrity, and long-term public health.

3.2. Classification of Persistent Organic Pollutants

Although certain compounds may fit into more than one group, the Stockholm Convention classifies POPs into three main categories based on their origin and intended use: (i) Pesticides, such as DDT, aldrin and chlordane, historically used in agriculture and disease vector control; (ii) Industrial Chemicals, such as PCBs and HCB, which were used in electrical equipment, flame retardants, and various manufacturing processes; and (iii) Unintended By-Products, primarily PCDD/Fs, generated during combustion and certain industrial operations [

41,

42].

Initially, the Convention identified twelve priority chemicals, known as the “Dirty Dozen”, but the list has since expanded to include 36 chemicals of global concern. Pesticides and industrial compounds remain the most prevalent in environmental matrices, particularly in urban environments, reflecting their historical use, persistence, and ability to accumulate in soils and dust [

40,

42,

43,

44].

Table 2 summarises the principal POPs found in urban park soils. These include both legacy pollutants and emerging contaminants, illustrating the complex mixtures that can affect ecosystems and human health.

In urban contexts, the importance of POPs increases as these compounds interact with complex and heterogeneous soils, where variable organic carbon content, particle size, and anthropogenic materials influence their distribution and bioavailability [

1,

51]. In urban parks, where people frequently come into close contact with the ground, these soils can act as long-term reservoirs of contamination and indirect, often overlooked sources of human exposure.

Understanding how these chemical and ecological processes interact is fundamental to connecting urban ecology and environmental toxicology. This connection highlights not only the way human-altered soils act as long-term repositories for pollutants, but also their potential to serve as early warning indicators of the overall environmental health of cities. This idea is further developed in the following chapter, which examines the primary historical and contemporary sources that contribute to POPs contamination in urban park environments.

4. Sources and Environmental Pathways of POPs in Urban Soils

The environmental persistence and global distribution of POPs continue to pose significant challenges for urban ecosystems, where complex interactions between human activity and soil processes determine their environmental fate [

36].

According to the United Nations Environment Programme [

52], legacy emissions from industrial and agricultural activities remain among the dominant sources of POPs residues in urban soils, highlighting the need to integrate both historical and contemporary perspectives when assessing urban contamination.

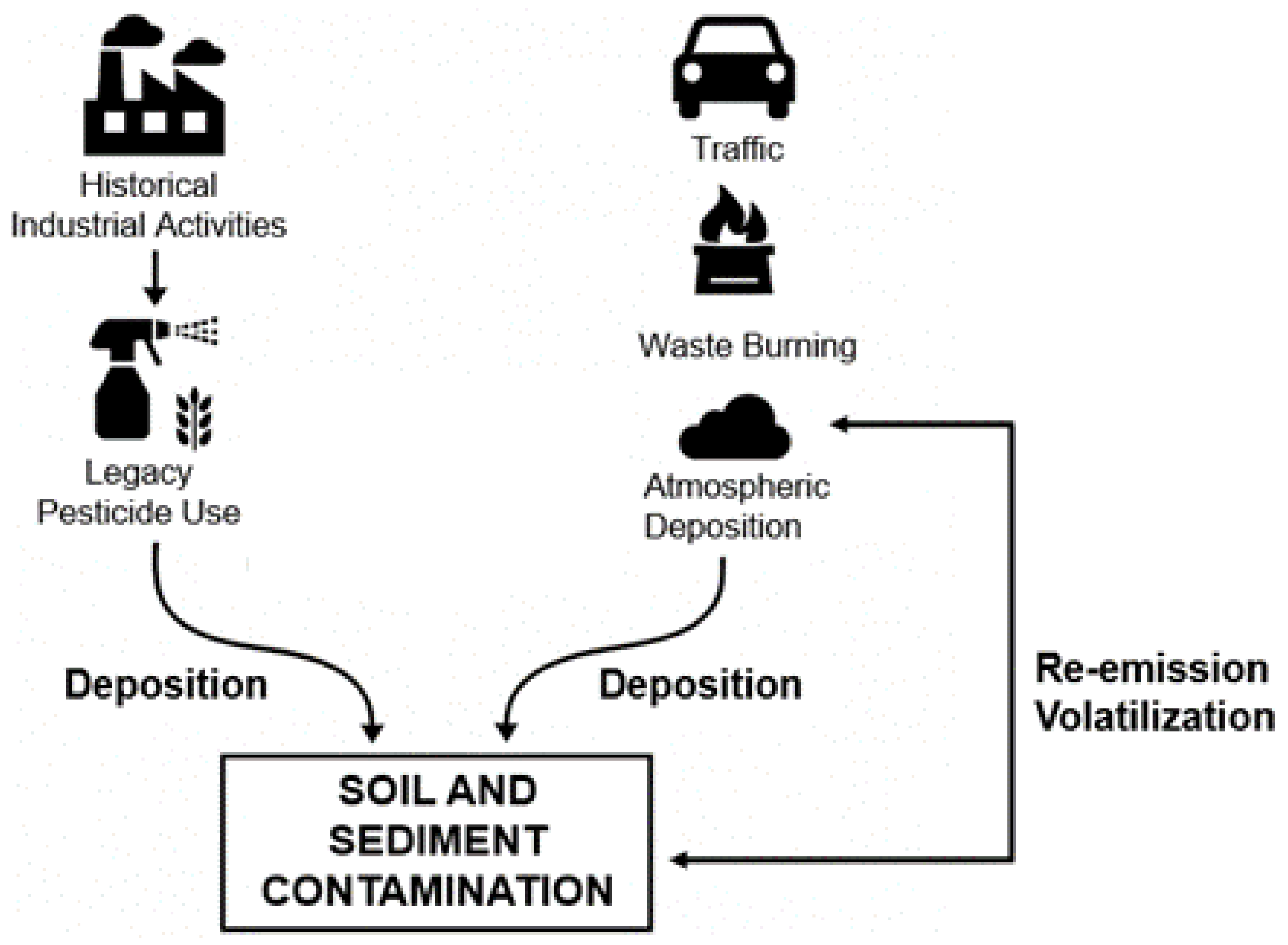

Persistent Organic Pollutants enter urban soils through both past and present anthropogenic pathways. Over decades, industrial activity, fuel combustion, pesticide use, and urban development have gradually enriched these soils with persistent contaminants that continue to influence the ecological balance and environmental quality of cities [

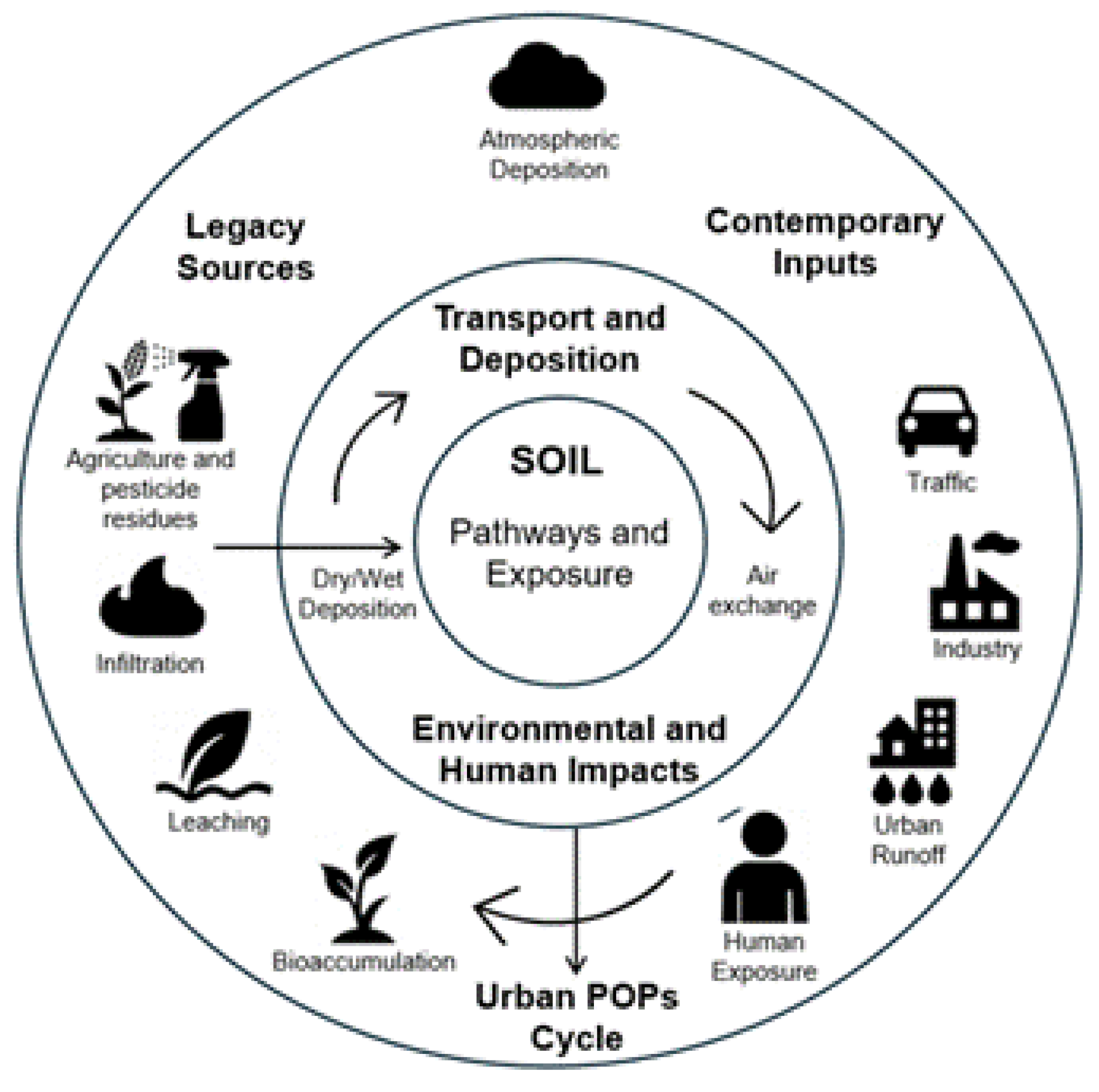

30]. Understanding the sources and ecological pathways of POPs is essential for interpreting contamination patterns in urban parks, identifying exposure hotspots, and developing effective remediation strategies. To illustrate how these different historical and contemporary sources contribute to contamination patterns,

Figure 3 summarises the main pathways through which POPs reach and cycle within urban soils.

4.1. Sources of POPs in Urban Soils: Past Legacies and Present Emissions

Although minor amounts of certain POPs, such as dioxins and furans, can be produced initially through natural events, like volcanic eruptions and wildfires [

53], most global emissions are anthropogenic. The contamination of urban soils reflects both past and present human activities, revealing how decades of industrial, domestic, and urban practices have gradually influenced, and continue to influence, the quality of the environment.

The Industrial Revolution and the subsequent technological expansion of the 20th century marked a turning point in the production and environmental dissemination of synthetic organic chemicals [

14,

30,

54]. During this period, the large-scale production and commercialisation of halogenated organic compounds, including DDT, aldrin, chlordane, HCHs, and PCBs, became symbols of technological advancement and agricultural modernisation. Their widespread application in agriculture, pest control, and urban green management has resulted in a persistent chemical legacy across landscapes that remains evident today [

30].

Between 1930 and 2019, approximately 31,306 kilotonnes (kt) of POPs were synthesised and commercialised worldwide, with short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs) identified as the most extensively produced, followed by α-HCHs, DDT, and PCBs [

30]. Due to their remarkable persistence and limited mobility, residues of these compounds remain detectable in urban park soils worldwide, even decades after their ban [

30,

54].

Industrial chemicals, such as PCBs, which are widely used in transformers, capacitors, hydraulic fluids, and construction materials, contributed to diffuse and long-lasting urban contamination. Poor waste management, accidental leakage, and the dismantling of obsolete electrical equipment facilitated the continuous release of these pollutants into the air and soil. Similarly, the production and use of HCB and other chlorinated intermediates further intensified long-term accumulation, particularly in industrialised regions of Europe and North America [

55].

In addition to direct industrial and agricultural sources, construction and demolition activities acted as significant secondary contributors. Building materials, such as paints, sealants, and wood preservatives, containing POPs gradually release residues through weathering and improper disposal, contributing to contamination in surrounding soils [

13,

55]. These historical legacies illustrate how 20th-century industrial and agricultural practices continue to shape the environmental signatures of contemporary urban landscapes.

While these historical emissions established the foundation of contamination in urban soils, contemporary sources continue to redefine their distribution patterns. In the modern urban environment, POPs inputs originate from diffuse yet continuous activities, including traffic emissions, waste burning, and atmospheric deposition. Incomplete combustion of fuels and open incineration release PCDD/Fs, which are deposited on soil surfaces and gradually incorporated into upper soil layers through rainfall, plant litter, and dust resuspension [

49]. These processes are further shaped by urban morphology, land use, and microclimatic conditions, which influence the dispersion, retention, and degradation of contaminants.

The result is a heterogeneous and evolving chemical landscape, where old and new pollutants coexist. Legacy contaminants slowly leach from soils and sediments, while present-day emissions reinforce existing burdens, sustaining the long-term presence of POPs in urban parks. Recognising this temporal and spatial overlap is fundamental for identifying contamination hotspots and designing effective monitoring and remediation strategies. To contextualise these dynamics,

Table 3 summarises the principal historical and current POPs detected in urban green spaces, outlining their sources, environmental behaviour, and associated toxicological effects.

4.2. Environmental Pathways and Mechanisms of Accumulation

4.2.1. Atmospheric Deposition and Air–Soil Exchange

The environmental behaviour of persistent organic pollutants in urban soils is a result of a dynamic interaction among atmospheric deposition, soil–air exchange, sorption, and ageing processes, as well as secondary redistribution mechanisms. These processes act simultaneously to determine the spatial distribution, persistence, and bioavailability of POPs across urban landscapes. In urban environments, the atmosphere serves as both a primary source and a secondary reservoir of POPs, continuously exchanging contaminants with soil surfaces through cycles of deposition and re-emission [

36,

56].

Atmospheric deposition is one of the main routes through which persistent organic pollutants enter terrestrial environments. Transported through the atmosphere, these compounds can travel from local to global scales before eventually settling into soils, where they may persist for decades. Due to their high chemical stability and strong affinity for organic matter, substances such as PAHs, PCBs, DDT derivatives, and dioxins tend to accumulate in soil layers rich in organic carbon, making soils one of the most significant long-term reservoirs of these pollutants [

57,

58].

As semi-volatile compounds, POPs continuously move between the gaseous and particulate phases of the atmosphere, maintaining a delicate balance that determines their transport, deposition, and eventual re-emission. Their entry into soils occurs mainly through two processes: dry deposition, which occurs as particles settle or diffuse under the influence of gravity, and wet deposition, driven by precipitation such as rain, snow, or fog [

59]. Meteorological conditions, including temperature, humidity, and the distribution of particle sizes, influence the efficiency of these processes. In temperate regions, research shows that deposition rates fluctuate seasonally. Accumulation tends to be higher during colder months when lower temperatures reduce volatilisation and facilitate the attachment of POPs to particles, promoting their descent to the surface. Conversely, warmer conditions facilitate re-volatilisation and atmospheric dispersion, leading to reduced deposition. These seasonal events help explain the temporal variations in POPs concentrations frequently observed in urban [

60,

61]

Urban vegetation further influences this process through the canopy filter effect, in which trees act as natural barriers that intercept airborne contaminants [

62]. Leaves and branches capture both gaseous and particulate pollutants, which are then transferred to the soil through processes such as throughfall, stemflow, and litterfall. Consequently, soils beneath dense canopies often contain higher concentrations of POPs than those found in nearby open lawns or paved surfaces [

63]. While urban vegetation provides vital ecosystem services, such as air purification, microclimate regulation, and biodiversity support [

64], it also facilitates the transfer of atmospheric pollutants into the terrestrial environment. This dual role underscores the complexity of urban green infrastructure, which serves as both a natural filter that mitigates air pollution and a long-term reservoir for persistent pollutants in urban soils [

62].

Empirical studies have demonstrated that urban trees effectively remove airborne particles through deposition on leaf and canopy surfaces, which can subsequently be washed off or transferred to the soil [

65]. Additionally, research on stemflow has demonstrated that water running down tree trunks acts as a localised pathway for the movement of solutes and pollutants into the soils beneath trees [

62].

Reviews on vegetation and air pollution further confirm that particle and gas interception by plant surfaces is a well-established process that contributes to pollution mitigation, while simultaneously increasing the flux of contaminants to terrestrial systems [

66,

67].

In summary, the interaction between atmospheric processes and urban vegetation influences the deposition and redistribution of POPs within city environments. Through both natural and human-modified processes, these compounds are continuously cycled between air and soil, gradually accumulating in areas of high organic content and dense vegetation. This process highlights the dual nature of urban ecosystems, as they regulate air quality and simultaneously serve as long-term repositories of contamination. Understanding this balance is crucial for evaluating the genuine environmental and public health implications of POPs in soils that remain in constant contact with urban life.

4.2.2. Sorption, Retention, and Ageing Processes in Urban Soils

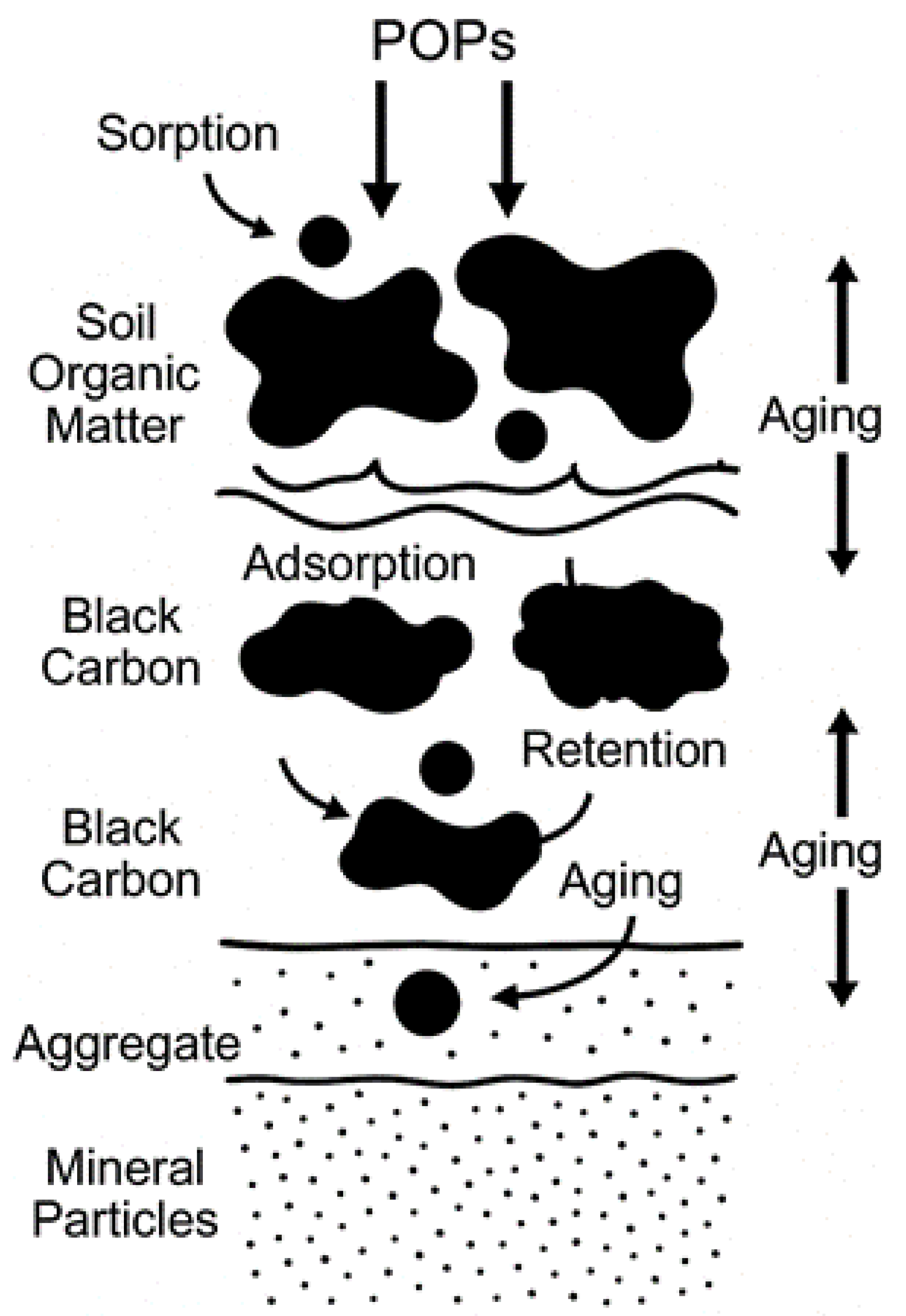

Soil serves as a significant sink for the accumulation and movement of POPs. After their deposition, these compounds form progressive associations with soil particles, becoming increasingly stabilised through interactions mediated by soil organic matter (SOM) and mineral components [

36]. Such interactions not only determine the environmental fate of POPs but also affect their persistence, mobility, and bioavailability within urban soils (

Figure 4).

The interaction between POPs and soil components is primarily conducted by sorption processes, which determine how strongly these pollutants are retained and how readily they may move or degrade over time. The strength of sorption varies greatly among soils and is strongly influenced by both the quantity and the quality of SOM. In particular, the proportion of soil organic carbon (SOC) plays a central role, as reflected by the wide range of measured organic carbon–water partition coefficients (KOC) across different soil types [

68].

Due to their pronounced hydrophobic nature, POPs tend to associate closely with organic carbon and other carbonaceous materials in the soil matrix. Among these, black carbon (BC), a by-product of the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and vegetation, has been identified as one of the most effective sorbents for these compounds. Typically present in soils and sediments at median levels of 4–9% of total organic carbon, BC contributes to sorption coefficients that are often two to three orders of magnitude higher than those expected solely from natural organic matter partitioning [

69]. This increased sorptive capacity reduces the bioavailability of POPs, mitigating their potential for trophic transfer and biological uptake, even in highly contaminated environments.

Beyond chemical affinity, the physical structure of the soils exerts a significant influence on the retention and persistence of pollutants. Soil aggregates, composed of SOM, mineral particles, and microbial exudates, form the structural framework of soils and create microenvironments that protect contaminants from degradation. Their formation and stability depend on the presence and transformation of SOM, which acts as a natural binding agent that links mineral particles into cohesive units. These aggregates not only regulate nutrient cycling and soil stability but also shape the spatial distribution and degradation dynamics of hydrophobic contaminants such as POPs [

36].

Within these microstructures, POPs can become sequestered in micropores or tightly bound to aged organic matter, which substantially reduces their desorption and biodegradation potential over time. This process occurs gradually and is often referred to as ageing or sequestration [

70]. It transforms readily available pollutants into less bioaccessible forms, effectively locking them within the soil matrix for extended periods. While such stabilisation can lower immediate exposure risks, it also prolongs the environmental lifetime of POPs, reinforcing the paradoxical role of soils as both protective sinks and persistent secondary sources of contamination [

70].

The spatial variability of POPs in urban soils is shaped not only by emission sources and physicochemical processes but also by the structure and function of the urban landscape itself. Land-use patterns, vegetation cover, and the degree of soil sealing influence how these compounds are deposited, redistributed, and retained. Impervious surfaces, such as roads and pavements, limit direct infiltration, promoting surface runoff and the movement of particle-bound materials across the landscape. In contrast, vegetated areas, including parks, tree belts, and community gardens, function as active sinks, capturing contaminants through canopy interception, facilitating both dry and wet deposition. Their root systems and organic matter accumulation further stabilise the soil, promoting pollutant retention and transformation [

70,

71]. However, these same soils can also retain legacy contaminants from former industrial or agricultural uses, resulting in heterogeneous contamination profiles across urban landscapes [

55].

Additionally, the design and morphology of urban areas model the microclimatic conditions that regulate the environmental behaviour of POPs. Variations in temperature, atmospheric mixing, vegetation density, and land use all affect volatilisation, deposition, and re-emission cycles. The interaction between organic-rich soils and anthropogenic materials, such as asphalt or concrete, determines the long-term stability and mobility of pollutants [

36,

72]. A detailed examination of the interactions between these physical and ecological factors is essential not only for interpreting the spatial distribution of contaminants but also for guiding remediation efforts and urban design strategies that minimise human exposure in public green spaces.

5. Environmental Fate and Behaviour of POPs in Urban Soils

Understanding the environmental fate of POPs in urban soils requires an integrated perspective that links their physicochemical properties with their interactions in soil and the influence of urban ecological processes. Once released into the urban environment, these compounds move in continuous cycles of deposition, transformation, and redistribution across multiple environmental compartments. Their persistence is not only a function of molecular stability but also the result of interactions with soil organic matter, mineral particles, and anthropogenic materials that characterise urban soils [

36].

As described in the previous chapter, the primary mechanisms that lead to the accumulation and stabilisation of POPs in soils, including sorption, retention within aggregates, and air–soil exchange, play a crucial role in determining how these compounds persist and re-enter the atmosphere. However, beyond these initial interactions, the long-term behaviour of POPs is conducted by a combination of degradation, transformation, and transport processes that evolve in response to changing environmental conditions. In the urban context, where soils are highly heterogeneous and frequently disturbed, these processes are further modulated by anthropogenic factors, microclimatic variability, and land-use intensity [

70,

73,

74].

Urban soils thus act simultaneously as sinks and secondary sources of contamination. They capture pollutants through atmospheric deposition, retain them through strong sorptive interactions, and later re-release them through volatilisation, erosion, or biogeochemical transformations. This cyclical behaviour sustains a subtle but continuous flux of pollutants that contributes to chronic, low-level exposure in densely populated environments [

36,

68,

72,

73].

This chapter examines these dynamics by addressing the primary processes that govern the transformation, transport, and persistence of POPs in urban soils. By synthesising current knowledge on degradation pathways, mobility, and environmental interactions, it highlights the complexity of contaminant behaviour in human-altered landscapes. It provides a conceptual basis for understanding their long-term ecological and public health implications.

5.1. Transformation, Transport, and Environmental Dynamics

The persistence of a compound in the environment reflects the combined action of physical, chemical, and biological processes that work together to transform or break down the compound. Among these, microbial activity plays a vital role in biodegradation and biotransformation, while abiotic transformations occur primarily through hydrolysis, photolysis (both direct and indirect), and redox reactions [

75]. These microbial and chemical reactions, along with bioaccumulation processes, represent the primary pathways that shape the environmental behaviour and fate of persistent compounds. Nevertheless, transformations of these compounds do not always reduce ecological risk. In fact, in some cases, they can generate products that are even more toxic than their parent compounds. This has raised increasing concern regarding the formation of metabolites and secondary transformation products in the environment. A well-known example is the photoactivation of PAHs, which can produce reactive intermediates with higher toxicity and mutagenic potential [

70].

Once released into urban soils, POPs become part of a dynamic system where these same physical, chemical, and biological processes interact continuously, determining their persistence, mobility, and long-term environmental behaviour. The rate and balance of these transformations are strongly influenced by local factors, such as climate, soil composition, and the degree of human disturbance that characterises urban environments [

36,

70,

76,

77].

Although POPs are known for their notable chemical stability and resistance to degradation, they do not remain entirely unchanged. At the soil surface, photolysis, oxidation, and hydrolysis are the primary abiotic processes, each influenced by sunlight, temperature, and soil moisture [

36,

78]. These reactions advance slowly and depend strongly on molecular structure. For instance, chlorinated dioxins can persist in soils for decades, whereas some brominated flame retardants are more readily broken down under ultraviolet light [

54].

In addition to abiotic transformations, soil microorganisms play a crucial role in the gradual breakdown of POPs. Laboratory and field studies have demonstrated that diverse bacteria and fungi can metabolise PCBs through both aerobic and secondary metabolic pathways. Soil microcosm experiments confirm that adapted microbial populations can accelerate degradation under controlled conditions [

79]. Pieper [

80] further demonstrated the extraordinary metabolic flexibility of specific bacterial strains, which are capable of using less-chlorinated congeners as carbon sources, illustrating the slow but continuous nature of these biological processes. More recent findings also reveal that bacterial isolates from contaminated soils can metabolise individual PCB congeners under aerobic conditions [

78].

Under favourable redox conditions, microbial degradation can occur in both oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor surroundings. Aerobically, genera such as Pseudomonas and members of the Sphingomonadaceae family (Sphingomonas, Sphingobium) have shown the ability to degrade organochlorine pesticides, including DDT and the four major isomers of HCH, using them as alternative carbon or nitrogen sources [

81,

82,

83,

84,

85]. In contrast, under anaerobic conditions, groups of microorganisms mediate the reductive dichlorination of highly chlorinated compounds, such as PCBs and dioxins, progressively removing chlorine atoms and thereby reducing their persistence and toxicity [

78,

86].

Together, these findings reveal that, despite their persistence, POPs are not completely static in the environment. Instead, they participate in slow, compound-specific transformation cycles, both chemical and biological, that collectively determine their long-term evolution within urban soils. These gradual reactions form part of the natural attenuation processes, which, although subtle, contribute to the eventual reduction of contaminant levels and provide valuable insights for remediation and risk assessment strategies.

However, the heterogeneous composition of urban soils can restrict microbial access to pollutants. High contents of black carbon, construction debris, and irregular moisture conditions can limit microbial access to contaminants, thereby reducing degradation efficiency compared with agricultural or natural soils [

69]. Additionally, the encapsulation of POPs molecules within dense soil aggregates further limits oxygen diffusion and microbial colonisation, thereby strengthening their long-term stability and explaining the persistence of legacy contaminants in urban environments [

36].

5.2. Vertical and Lateral Transport Mechanisms

Beyond their chemical and biological transformations, the environmental behaviour of POPs in urban soils is also regulated by their physical mobility. Once deposited, these compounds move both vertically and laterally through soil matrices, air, and water compartments. Their redistribution is influenced by molecular properties, soil composition, and hydrological dynamics, resulting in complex spatial patterns of accumulation and exposure across urban environments. Studies have shown that POPs such as PCBs and PCDD/Fs can migrate both downward and laterally within soil profiles along hydrological gradients, demonstrating that even compounds firmly attached to soil particles are subject to gradual movement within terrestrial systems [

87]. At larger scales, atmospheric exchange processes, including diffusion and particulate deposition, play a vital role in redistributing contaminants between air and soil, influencing their long-term behaviour in urban environments [

88]. Recent observations also highlight the contribution of long-range atmospheric transport and re-deposition, allowing small but persistent inputs of POPs to reach urban soils, reflecting the constantly evolving nature of these environments [

89] (

Figure 5).

The mobility of POPs within urban soils is primarily controlled by their physicochemical characteristics, including hydrophobicity, molecular weight, and affinity for organic matter. Highly hydrophobic compounds, such as PCBs, DDTs, and dioxins, tend to remain adsorbed to SOC and fine soil particles, exhibiting minimal vertical leaching potential [

70]. However, over time, slight changes in redox potential or pH can disrupt the equilibrium between soils and pollutants, leading to the gradual release and redistribution of these compounds. Vertical migration into deeper horizons can also be facilitated by preferential flow channels, such as root pathways, soil cracks or artificial drainage systems, that overcome the sorptive barrier of topsoil layers [

90]. Together, these mechanisms highlight that contaminants can slowly migrate over time, complicating efforts to understand, monitor, and mitigate pollution within urban green spaces [

91,

92].

In addition to their downward migration through soils, POPs can also spread laterally across the urban landscape, carried by surface runoff during rain events and by the resuspension of contaminated dust particles. When rainwater runs across pavements and streets, it gathers fine, polluted particles that are then washed into green spaces. At the same time, wind action and vehicle movement resuspend dust enriched with pollutants, facilitating its atmospheric transport and subsequent deposition into urban and residential soils. These lateral transport pathways play a crucial role in disseminating contaminants across urban environments, extending exposure beyond their original emission sites [

87,

93,

94].

The interaction between vertical and lateral transport mechanisms creates a constant state of movement within urban soils. Contaminants that once migrate downward may later re-emerge at the surface through atmospheric exchange, erosion, or human disturbance, sustaining a persistent chemical presence in the upper layers. This continuous circulation explains the long-term environmental stability of POPs and highlights the need to recognise urban soils as active components of the pollutant life cycle within cities [

55,

70]. Such persistent cycling not only determines the environmental fate of POPs but also increases the likelihood of human exposure to them. Individuals who frequently use green spaces, especially children and the elderly, may come into direct contact with contaminated soils or inhale resuspended particles, raising concerns about chronic exposure and its related health effects. Studies have shown that POPs in urban soils and dust can contribute to chronic exposure pathways with implications for immune function, endocrine disruption and long-term health outcomes [

95,

96].

Altogether, these processes reveal that urban soils are dynamic, interactive systems that continuously mediate the balance between pollutant storage and exposure. The following section explores how these persistent contaminants, through their physical and biological interactions, shape human exposure risks and inform strategies for urban soil monitoring and remediation.

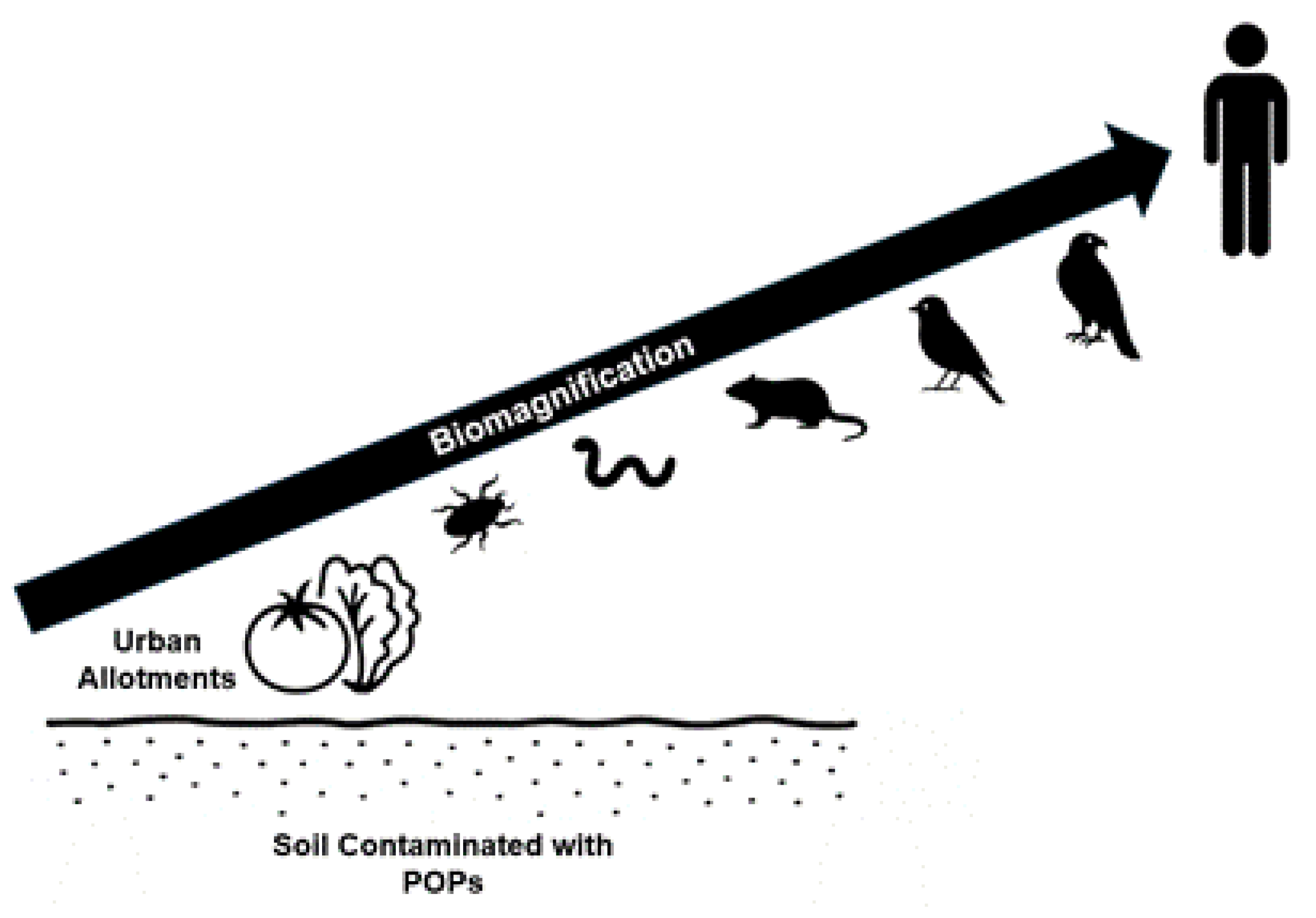

5.2.1. TROPHIC transfer and Biomagnification in Urban Food Webs

Although human exposure is often discussed in terms of direct contact with contaminated soil or dust, understanding the trophic dynamics of POPs in urban ecosystems provides critical insight into how these compounds persist, circulate, and indirectly contribute to human exposure.

Urban food webs can retain and amplify POPs as they move from contaminated soils and invertebrates to birds and mammals inhabiting green spaces. In a terrestrial food-web assessment conducted across the Metro Vancouver region, Fremlin et al. [

97] quantified trophic magnification factors (TMFs) for several legacy and emerging POPs detected consistently across soil invertebrates, songbirds, and raptors. Reported TMFs ranged from approximately 1.2 to 15, confirming that most of the investigated compounds exhibited clear biomagnification along the urban trophic hierarchy. Notably, the magnitude of TMFs showed a significant positive relationship with the physicochemical properties of the compounds, specifically with the octanol-air (log

KOA) and octanol-water (log

KOW) partition coefficients, indicating that highly hydrophobic and air-reactive pollutants tend to accumulate more efficiently in terrestrial food webs. These results demonstrate that, even decades after regulatory bans, persistent pollutants continue to circulate and biomagnify within urban ecological networks, posing potential sublethal risks to higher-level predators that populate urban green spaces.

Valuable evidence on the terrestrial transfer of persistent pollutants has been provided by long-term biomonitoring programmes such as the United Kingdom’s Predatory Bird Monitoring Scheme (PBMS). This programme quantifies concentrations of pesticides and POPs, including PCBs, PBDEs, and DDT derivatives, in the livers and eggs of predatory birds across both rural and urban regions [

98]. Data from the PBMS have demonstrated consistent bioaccumulation and biomagnification patterns in species such as kestrels, sparrowhawks, and peregrine falcons, revealing higher contaminant burdens in individuals from urban and peri-urban landscapes. These findings highlight how top predators act as sentinels of terrestrial contaminant transfer, integrating exposure from multiple trophic levels and reflecting the persistence of legacy pollutants in urban environments. In addition to exposure monitoring, the PBMS has provided long-term evidence of the effectiveness of mitigation strategies in lowering pollutant concentrations, while continuing to identify emerging substances of toxicological relevance.

Figure 7 illustrates the trophic pathways and contaminant flow within urban food webs, as documented by the PBMS and complementary studies, highlighting how POPs move from soils through invertebrates and birds to apex predators in urban contexts.

Additional evidence from Europe and Asia reinforces the persistence and trophic transfer of both legacy and emerging POPs in terrestrial urban systems. In Oslo, Heimstad et al. [

49] conducted an eight-year monitoring programme that traced per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) across soil, invertebrates, passerine eggs, and urban predators. Their findings revealed clear bioaccumulation from soil to earthworms and biomagnification through the earthworm–fieldfare–sparrowhawk food chain, with PFOS and long-chain PFAS dominating across all trophic levels. These results highlight that urban terrestrial food webs can sustain long-term contaminant cycling even under cold-climate conditions and after decades of emission controls.

Similarly, in a controlled field investigation in China, Wu et al. [

99] demonstrated that detritivore invertebrates, particularly earthworms and beetles, act as efficient vectors for the transfer of PCBs and PBDEs within soil-based food webs. Their work revealed strong links between bioaccumulation factors and compound hydrophobicity, confirming that less volatile, high kow pollutants tend to concentrate and persist along terrestrial trophic chains.

Complementary long-term evidence from Bucharest provides a broader urban perspective. Sandu et al. [

100] reported that although total PCB concentrations in soils declined substantially between 2002 and 2022, persistent hotspots remained in public parks and roadside green spaces, particularly for heavier congeners such as PCB-180. Despite an overall reduction in carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks, the authors highlighted the ongoing exposure potential, especially for children, using contaminated urban soils.

Together, these studies show that POPs in urban areas rarely remain static. Instead, they circulate through soil, invertebrates, and higher organisms, gradually amplifying within urban ecological networks. This trophic perspective adds an essential environmental dimension to the understanding of POPs in urban parks, linking soil contamination not only to environmental persistence but also to bioecological connectivity and potential pathways for indirect human exposure. Just as soil, dust, and vegetation can mediate pollutant contact for humans, they also sustain the exposure routes that drive biomagnification within city ecosystems. Recognising these ecological pathways enables a more comprehensive assessment of human health risks in urban parks, where humans and wildlife share interconnected environmental compartments.

5.3. Toxicological and Health Impacts of Persistent Organic Pollutants

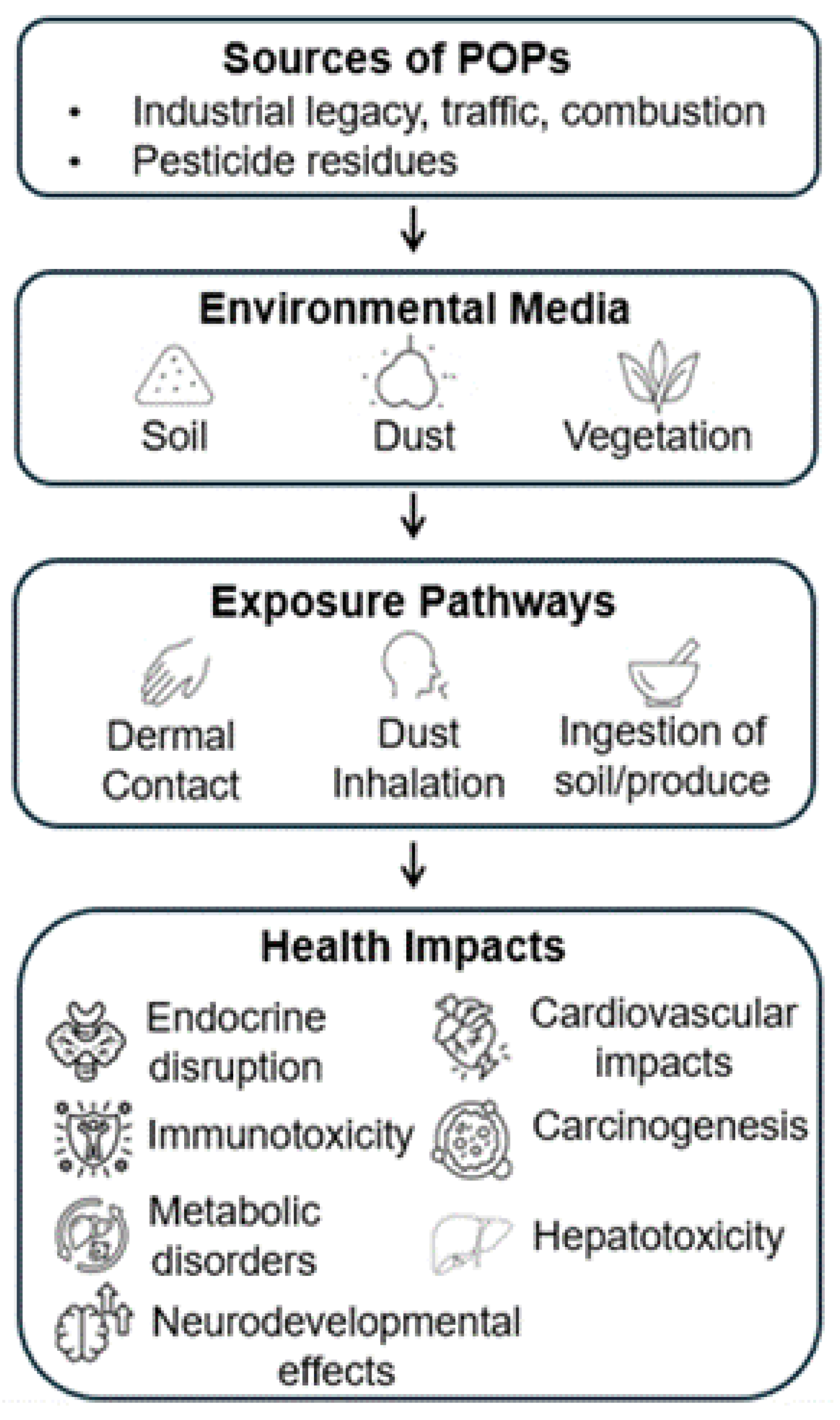

As highlighted in previous chapters, urban parks and green spaces, although essential to public well-being, can also act as contact zones of environmental exposure to POPs. Within these environments, contaminated soils, resuspended dust, and vegetation may contribute to chronic, low-level exposure to these contaminants. Even at concentrations below conventional regulatory thresholds, such exposures have been associated with alterations in physiological function, particularly within the endocrine, nervous, immune, and cardiovascular systems [

30,

54,

55]. A schematic overview of the main exposure routes and associated health effects of POPs in urban parks is presented in

Figure 8.

Growing evidence from both legacy and emerging compounds suggests that even low-level exposures, typical of urban populations, can disturb hormone regulation, weaken immune responsiveness, and affect developmental balance, highlighting the continuing public-health relevance of these pollutants in contemporary urban environments [

30,

50,

54].

Despite their structural diversity, POPs exhibit a shared capacity to disrupt endocrine and cellular signalling, alter developmental pathways, and induce chronic systemic stress. OCPs, such as DDT, HCHs, and chlordane, are well-recognised endocrine disruptors and probable carcinogens, with substantial evidence linking their presence to reproductive and developmental toxicity [

42,

45]. DDT and its metabolites (DDE, DDD), extraordinarily persistent in soils with half-lives that may extend over centuries, have been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer later in life [

101]. Similarly, compounds such as heptachlor and HCB are characterised by slow environmental degradation and a strong propensity to accumulate in organic matter, with animal studies documenting hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, and tumour-forming potential; however, human epidemiological evidence remains limited [

46,

102,

103,

104].

Among industrial pollutants, PCBs and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) are among the most biologically active contaminants detected in urban soils and dust. PCBs are highly lipophilic, allowing for accumulation in human tissues, where they have been associated with neurodevelopmental disruption, thyroid dysregulation, and increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease [

105,

106,

107,

108]. In a Swedish cohort, circulating PCB concentrations were positively correlated with the presence of atherosclerotic plaques and with increased echogenicity of the intima–media complex, independently of traditional cardiovascular risk factors [

106], suggesting that these pollutants may contribute directly to vascular pathology. Similarly, recent evidence indicates that exposure to brominated flame retardants is positively associated with hypertension in the general population [

48]. PBDEs, widely used as flame retardants, share comparable physicochemical properties and have been linked to endocrine disruption and neurotoxicity, particularly during early developmental stages, when the nervous system is most vulnerable [

47]. The health implications of these compounds are especially concerning in urban contexts, where inhalation of contaminated dust and direct contact with soil are recurring routes of exposure.

Beyond these industrial pollutants, unintended by-products such as PCDD/Fs also persist in urban environments, primarily arising from combustion processes and waste incineration. Their strong affinity for particulate matter and tendency to accumulate in soils contribute to their long-term persistence in urban parks and residential green areas [

41]. Dioxins function as potent endocrine modulators and immunotoxic agents. They are recognised as human carcinogens, with multiple population-based studies reporting associations between exposure and altered thyroid hormone levels or immune dysregulation [

42,

109,

110]. Even at environmental levels, chronic low-dose exposure to dioxins has been correlated with increased all-cause mortality, highlighting their systemic impact and enduring public-health relevance at environmentally realistic concentrations [

111,

112].

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), notably perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), constitute a newer generation of persistent contaminants, now recognised for their exceptional environmental stability and strong bioaccumulative potential [

44]. Initially developed for use in firefighting foams and surface coatings, these compounds are today consistently detected in urban soils, sediments, and even groundwater [

49]. Epidemiological evidence has linked PFOS exposure to thyroid hormone disruption, hepatic toxicity, and immune suppression, including reduced vaccine antibody responses in children [

113]. PFOA, comparably stable and mobile within aquatic systems, has been associated with developmental toxicity, liver dysfunction, and elevated cancer risk [

44,

114]. Recent evidence from a cross-sectional study in China demonstrated that plasma concentrations of multiple PFAS, including PFOS and PFOA, were significantly associated with altered thyroid hormone profiles in elderly populations. Increases in PFAS levels were correlated with decreased concentrations of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4), alongside elevated total T3 and T4 levels, indicating that combined PFAS exposure may exert measurable thyroid-disrupting effects even at background environmental levels [

115]. Their growing presence in the soils and sediments of urban parks highlights that these emerging pollutants represent the persistence, mobility, and chronic exposure pathways characteristic of legacy POPs.

Pentachlorophenol (PCP), historically used as a wood preservative and herbicide, adds another dimension to urban contamination profiles. Although its environmental persistence is moderate compared to PCBs or DDT, PCP degrades slowly under anaerobic conditions and has been linked to hepatotoxicity and carcinogenicity in occupational and community studies [

50].

The cumulative human health impact of these compounds reflects not only their toxicity but also their capacity to interact additively or synergistically in human tissues. Global epidemiological evidence shows that chronic exposure to POPs mixtures, even at low levels, can contribute to endocrine imbalance, immunosuppression, neurodevelopmental impairment, metabolic dysregulation, and carcinogenesis [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120]. Within the context of urban parks, these findings gain particular relevance: children’s play, urban gardening, and recreational activities all increase the direct soil contact or dust inhalation, facilitating low-dose, chronic exposure.

Understanding these health implications highlights the need for continued vigilance in monitoring and managing POPs contamination within urban parks. These compounds are not inert residues of past pollution. They remain biologically active, mobile, and capable of influencing multiple physiological systems at environmentally relevant concentrations. Recognising their diverse toxicological profiles, which encompass endocrine and immune disruption, as well as metabolic and carcinogenic effects, reinforces the importance of proactive soil assessment, ongoing public health surveillance, and targeted mitigation strategies in urban green spaces designed for recreation and well-being.

6. Global Evidence and Patterns of POPs Contamination in Urban Parks

Urban parks, although designed as spaces for recreation, ecological restoration, and community wellbeing, have increasingly been recognised as environmental compartments where POPs accumulate. Their soils act as long-term sinks for both historical and contemporary emissions, integrating inputs from diffuse atmospheric deposition (dry and wet), resuspension of contaminated dust, aged legacy residues, and routine urban maintenance practices.

Over the past two decades, a rapidly expanding body of peer-reviewed research has documented the occurrence, spatial distribution, and primary sources of POPs in urban parks and recreational green spaces worldwide. Despite substantial regional and climatic variability, these studies reveal identifiable patterns in concentration ranges, congener profiles, and spatial gradients. Together, these findings provide valuable insights into the environmental pressures affecting urban green infrastructure and help clarify the potential exposure pathways for populations, particularly children and other vulnerable groups.

This section synthesises the global evidence on POPs contamination in urban park soils, with emphasis on concentration levels, compositional patterns across major compound classes (including OCPs, PCBs, PCDD/Fs, PBDEs, PFAS, and PAHs), spatial and temporal trends, and the lessons that can inform risk assessment and environmental management.

Based on this conceptual understanding, the following sections examine the empirical evidence emerging from diverse geographical regions. By reviewing studies conducted in Asia, Europe, the Americas, and other urbanised areas, it becomes possible to trace how different historical legacies, industrial activities, climatic conditions, and urban planning practices shape the contamination profiles observed in park soils.

6.1. Overview of the Current Literature

Empirical work across different continents provides a concrete basis for understanding how POPs contamination occurs in urban parks. Over the last two decades, researchers have investigated soils from parks, playgrounds, and other recreational green spaces in cities with diverse climates, varying levels of industrialisation, and distinct land-use histories. These studies reveal that, despite regional differences, urban parks tend to accumulate a mixture of legacy and contemporary pollutants, with contamination profiles that reflect the socio-economic and industrial evolution of the surrounding urban environments. Across many cities, studies now show that urban park soils rarely contain a single class of contaminant. Instead, they accumulate traces of pollution, ranging from traffic-derived PAHs to residual chlorinated and fluorinated residues, reflecting the interaction between human activity and time in these shared green spaces [

121,

122,

123].

Evidence from Asian megacities, European capitals, and rapidly developing urban centres indicates that the type and magnitude of contamination are influenced by a combination of local emission sources, such as traffic, industry, or waste management, as well as broader atmospheric transport processes. These geographically diverse observations not only highlight shared contamination patterns but also reveal significant regional differences.

In East Asia, rapid urbanisation, high population density, and a historic reliance on chlorinated pesticides have left an evident legacy. Surveys in Beijing parks, for example, still detect DDTs and HCHs, reaching concentrations of up to 1039 ng/g and 197 ng/g, respectively, linked to past applications, regional transport, and seasonal re-volatilisation [

124]. Similar patterns are reported across the region. In Hong Kong soils, including those in landscaped areas and parks, concentrations of PCBs ranged from 0.07 to 9.87 μg/kg, showing pronounced urban-rural PCB gradients indicative of diffuse inputs from electrical equipment, building materials, and legacy paints [

125]. Complementary nationwide monitoring in South Korea (2013–2016) reinforces these patterns. A multi-year survey found that although overall OCP levels in urban, suburban, agricultural and industrial soils have been declining since the national ban, residues and metabolites such as p,p′-DDD and endosulfan sulphate remain persistent. The study revealed that historical applications continue to influence contamination profiles, while localised traces of HCH and chlordane indicate recent use in specific areas [

126].

Comparable findings were reported in Guiyang, a rapidly industrialising Chinese city where soils contained mixed residues of DDTs, HCHs and PAHs, with concentrations of Σ16PAHs reaching up to 1708 µg/kg. The prevalence of four-ring PAHs and diagnostic ratios indicated a mixed pyrogenic source, primarily from traffic and industrial combustion. At the same time, detectable OCPs reflected both historical use and ongoing diffuse inputs [

127]. These results demonstrate how urban growth and industrial density continue to influence population profiles in Asian cities.

Recent work in the Pearl River Delta, one of the world’s largest urban agglomerations, revealed that soils contain measurable levels of both polybrominated and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins/furans [

128]. Concentrations were closely correlated with urban and industrial indicators such as gross domestic product, vehicle density and waste-incineration capacity, revealing how urban growth continues to shape the chemical character of city soils. The study also identified distinct spatial patterns, with PBDD/Fs dominating in highly urbanised centres and PCDD/Fs persisting in peripheral agricultural zones. These findings reflect the interaction of legacy and contemporary sources observed in European and Asian urban parks.

Beyond OCPs, dioxins and furans have emerged as significant contaminants in recreational areas of southern China. Central urban parks in several cities have shown significantly elevated TEQ concentrations compared to lawns and roadside greens, consistent with the influence of municipal sludge use and nearby waste-incineration sources. Spatial contrasts within cities suggest that atmospheric deposition is a dominant transfer route for mixed combustion emissions [

13,

129,

130].

This combined influence of local activities and atmospheric deposition also defines contamination patterns in European urban environments, although with greater regional variability. Across the continent, cities present a more heterogeneous but still concerning scenario. In southern Europe, detailed assessments in Lisbon identified PAHs as the predominant POPs-like contaminants in parks, gardens and playgrounds. Parks in Lisbon exhibited Σ16PAHs in the sub-mg/kg to mg/kg range, showing distinct pyrogenic evidence characteristic of traffic and other combustion activities, a pattern consistent across major European capitals [

121]. Comparable observations across the Iberian Peninsula and Atlantic coast consistently indicate that traffic and residential combustion are the primary contributors to contamination in park and urban green soils [

131].

In Glasgow, Σ15PAHs in urban park soils ranged from 1,487 to 51,822 µg/kg, reinforcing that even non-industrial green spaces retain clear evidence of chronic urban deposition [

132].

Studies in central/eastern Europe, including those conducted in Bratislava´s kindergartens and playgrounds, report Σ16PAHs in the tens to hundreds of µg/kg, highlighting the potential for exposure in environments frequented by young children [

133].

Long-term urban assessments indicate that while overall PCB levels have declined, heavier congeners tend to persist in localised hotspots, such as parks and roadside green areas. Recent monitoring in Bucharest (2002–2022) revealed clear downward trends, although PCB-180 concentrations still exceeded guideline values in several public spaces [

100].

Emerging PFAS patterns are now increasingly visible in European soils, including in and around city parks. Long-term trend data from German ecosystems reveal measurable PFAS in soils, highlighting the importance of atmospheric inputs [

134].

A recent 215-site survey in Lyon demonstrated strong associations between PFAS concentrations, prevailing winds, and proximity to or downwind position from a major chemical complex, providing clear evidence for atmospheric deposition as a key pathway to urban soils, with direct implications for parks situated downwind of the affected area [

123].

Beyond Europe and Asia, a growing body of research from North America provides further insight into POPs behaviour in urban parks. In Canadian cities such as Toronto, high-resolution monitoring has identified PAH hotspots within park soils, particularly near busy traffic corridors and older residential areas. SOM content, traffic density, and proximity to highways emerge as consistent predictors of contamination [

122,

135].

For PCBs, congener-resolved surveys in East Chicago (Indiana) show spatial heterogeneity in residential soils at the neighbourhood scale. This observation is equally relevant for adjacent parks and schoolyards situated within densely urban environments [

136].

In regions with historically less stringent regulations, the available, but still limited, evidence raises additional concerns. In West and Central Africa, for example, studies report elevated OCPs in urban and peri-urban settings, including soils and dust from densely used city areas and markets, with residue patterns consistent with legacy contamination and, in some cases, indications of ongoing inputs [

137,

138,

139,

140,

141].

Across Latin America, primary measurements in large urban areas show the same trends. Park-adjacent and residential soils accumulate combustion-derived PAHs together with legacy chlorinated organics, with concentrations and profiles tracking traffic intensity, land-use history, and proximity to industry. In Mexico City, soil surveys at the urban edge reported ΣPAHs ranging from ~9 to 36 mg/kg, with diagnostic ratios indicating pyrogenic inputs, highlighting the influence of transport and domestic combustion on urban topsoils [

142].

In Argentina, congener-specific work in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area detected both PAHs and PCBs in urban soils and street dust, with source apportionment implicating vehicle emissions and historical PCB uses. A separate study in Bahía Blanca confirmed the presence of measurable PCBs and PBDEs in the city [

143,

144].

Taken together, the international evidence reveals a coherent understanding of how POPs behave in urban park environments. These soils are influenced by multiple factors, including historical residues and diffuse urban emissions, as well as long-range atmospheric transport. Although contamination levels vary among regions, with increases in rapidly industrialising parts of Asia and declines across Europe and North America, the primary mechanisms remain remarkably consistent. Globally, the research shows that urban parks, despite their ecological and social value, are not protected from the legacy of persistent pollution. This understanding highlights the importance of locally informed monitoring, particularly in areas frequented by children, and provides valuable context for interpreting POPs dynamics in Portuguese urban parks.

6.2. Comparative Synthesis

6.2.1. Global Concentration Ranges and Compositional Patterns

Across continents, research consistently shows that the soils of urban parks act as long-term integrators of multiple classes of POPs.

Table 5 summarises the dominant pollutant classes, typical concentration ranges, and primary sources reported across different world regions, providing a concise view of the geographic contrasts described in the previous section.

While absolute concentrations differ widely, typical ranges for Σ₁₆PAHs range between 0.1 and 5 mg/kg in European cities and up to 10–40 mg/kg in rapidly industrialising regions of Asia [

121,

122,

131]. In contrast, OCPs and PCBs are typically found at ng/g levels. However, concentrations can be several hundred times higher in places near emission hotspots. These elevated values often reflect the slow volatilisation of pollutants from ageing infrastructure and residues of past pesticide use [

100,

136]. PFAS and other emerging compounds are increasingly detected in the low µg kg⁻¹ range, confirming their widespread atmospheric mobility and accumulation even in non-industrial green areas [

134].

Each pollutant group reflects a different aspect of human activity and environmental history. OCP residues reflect historical agricultural practices, PCBs indicate diffuse urban emissions from older materials, PAHs carry the legacy of traffic and combustion, and PFAS represent contemporary industrial and consumer sources.

Despite their different origins, their coexistence in the same soil matrices highlights the complex nature of urban contamination, a record of both past and ongoing human activity that continues to define the chemical character of urban parks worldwide.

6.2.2. Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Contamination

Globally, the spatial distribution of POPs in park soils follows consistent patterns. Concentrations are typically highest in central or traffic-dense parks and decline progressively toward peripheral or suburban green spaces [

121,

122,

131]. This gradient reflects both proximity to emission sources and the influence of atmospheric deposition as the primary transfer pathway. Localised hotspots often emerge near roads, playgrounds, or maintenance areas, where resuspended dust and vehicular emissions amplify soil contamination [

124,

132]. Soils enriched in organic matter tend to retain higher levels of hydrophobic compounds such as PAHs, PCBs, and OCPs, confirming the vital role of soil texture and carbon content in controlling pollutant partitioning and persistence [

73].

Temporal assessments show that long-term regulatory actions have successfully reduced the concentration of several banned compounds. Persistent declines in DDTs, HCHs, and PCBs have been documented across Asia and Europe [

100,

126], although heavier congeners (e.g., PCB-180, PCB-138) and stable metabolites (e.g., p,p′-DDD, endosulfan sulphate) remain measurable decades after their restriction. These residues represent the permanent legacy of historical emissions stored in soils and reintroduced into the atmosphere through re-volatilisation and dust resuspension [

145,

146].

In contrast, more contemporary pollutants, such as PAHs and PFAS, exhibit slower or minimal declines. PAH levels often show seasonal fluctuations, increasing during colder months as intensified heating and stable atmospheric inversions promote their accumulation and deposition [

147]. PFAS, on the other hand, exhibit persistent or even increasing soil concentrations in urban environments, reflecting their continuous introduction through consumer products, urban runoff, and atmospheric fallout [

123,

134].

Overall, these spatial and temporal dynamics reveal the dual nature of contamination in urban parks. While mitigation policies have reduced overall loads of legacy POPs, the soils of green spaces remain active repositories, continuously accumulating residues from diffuse and persistent sources. This persistence highlights the importance of long-term monitoring and periodic reassessment, particularly in densely populated cities where children and other vulnerable groups frequently use public parks [

122,

133].

6.2.3. Cross-Regional Comparison and Shared Mechanisms

When data from Asia, Europe, the Americas, and Africa are examined together, similar patterns emerge in both contamination sources and behavioural dynamics. Rapidly industrialising cities in East and South Asia, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Mumbai, consistently exhibit the highest overall POPs levels, with concentrations influenced by combustion-derived PAHs and residues of OCPs linked to historical agricultural use [

124,

127]. These contamination profiles reflect the combined effects of rapid urban expansion, high traffic density, and legacy pollution, particularly in cities where regulatory controls were implemented relatively recently [

126,

128].

Across Europe and North America, patterns are more diverse but equally instructive. Urban Park soils tend to have lower overall POPs concentrations but greater chemical diversity, reflecting the combined influence of industrial emissions, traffic, and atmospheric transport from nearby regions [

121,

122,

135]. The persistence of PAHs and PCBs in older industrial centres such as Glasgow, Bucharest, and Chicago reflects how diffuse re-emission from infrastructure, road dust, and ageing materials sustains measurable background levels even decades after emission bans [

100,

132,

136].

In Latin America and Africa, the limited available data reveal similar mechanisms. Urban and peri-urban parks in Mexico City, Buenos Aires, and several West and Central African capitals exhibit elevated PAH and OCP residues, which are associated with proximity to traffic corridors, informal waste burning, and obsolete pesticide storage facilities [

138,

140,

141,

142,

143]. These findings suggest that even under distinct economic and climatic conditions, the same fundamental processes (combustion, legacy residues, and diffuse atmospheric transport) continue to shape the spatial patterns of POPs in urban green spaces.

Taken together, these shared mechanisms demonstrate that urban contamination is not an isolated occurrence but a consequence of urban growth and human activity. Urban parks and green spaces serve as repositories for this process, receiving, retaining, and gradually releasing pollutants through deposition, resuspension, and volatilisation. Their soils preserve both the historical and contemporary chemical traces of the cities that surround them, reflecting the close connection between urban activity and environmental persistence [

145,

146].

7. Regulatory Frameworks and Soil Quality Guidelines

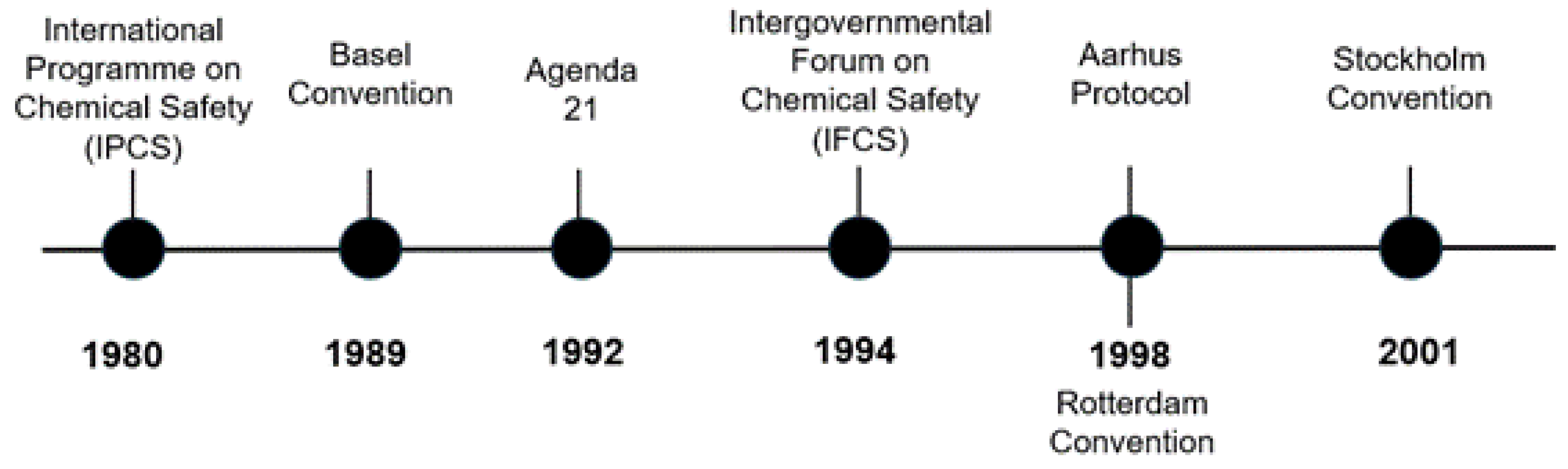

7.1. Global and European Frameworks Regulating Persistent Organic Pollutants

Global efforts to regulate POPs evolved gradually over the past few decades, as scientists and policymakers began to understand that these chemicals, once released, could persist for generations and move far beyond their sources. The first coordinated response emerged in the early 1980s with the creation of the International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS), a joint initiative of the World Health Organisation, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the UNEP. The IPCS represented one of the first collective efforts to establish a scientific foundation for assessing the risks of hazardous substances and promoting a shared vision of chemical safety at the global level [

23].