Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

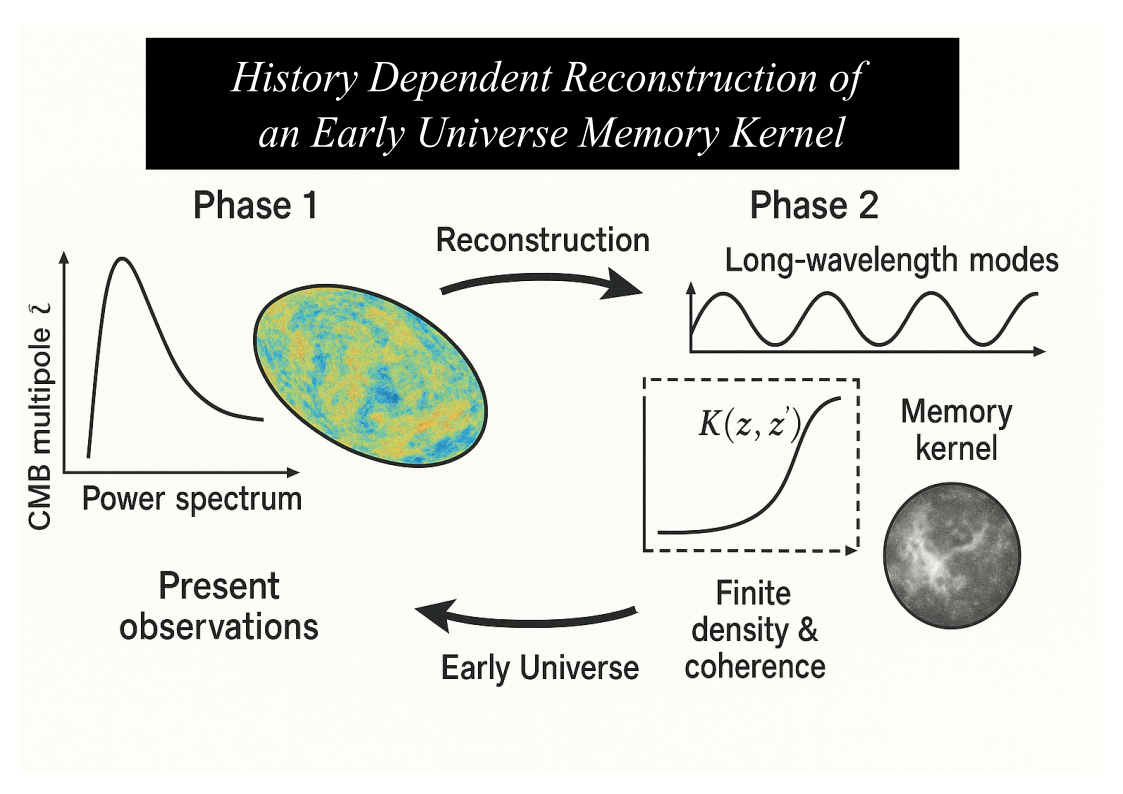

- introduces the Infinite Transformation Principle (ITP) as a history-dependent dynamical law;

- constructs a stable backward evolution through a memory-corrected Jacobian;

- provides four independent, parameter-free predictions [14].

2. Methods: The Infinite Transformation Principle

2.1. History-Dependent Evolution

2.2. Physical Origin of Memory

2.3. Sufficient Statistics

- curvature–redshift evolution [10].

2.4. Independent Structural-Memory Diagnostics

(1) CMB Phase-Coherence Inverse Kernel Test

(2) Metallicity Structural-Memory Kernel Test (SMKT)

(3) Gaussian Heartbeat Detection

(4) Injection–Recovery Stability Tests

3. Results: Mathematical Reconstruction

3.1. Linear Stability and Jacobian Structure

3.2. Convergent Evidence

- **CMB Phase-Coherence:** The observed bipolar coefficient pattern exceeded the 99.1% null envelope. Posterior maps favoured a minimal non-zero kernel .

- **Metallicity :** We obtained and a global p-value , rejecting the smooth, memory-less null at .

- **Gaussian Heartbeat:** The flexible GP recovered a coherent 1.66–1.73 Gyr periodic component with p-value , while the smooth baseline yielded .

3.3. Cross-Consistency

4. Discussion

4.1. Coherence and Non-Randomness

4.2. Unified Constraint from Fossils

4.3. No Singular Beginning Required

4.4. Falsifiable Predictions

- Persistent CMB low-ℓ coherence ().

- Void–CMB alignment ().

- Slow curvature drift ().

- Equilateral/orthogonal primordial non-Gaussianity at large scales.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Stability of the Memory-Corrected Backward Flow

References

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 Results. VII. Isotropy and Statistics of the CMB. Astron. Astrophys. 641, A7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. R. Bond. Cosmological Initial Conditions from Observations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4369 (1995).

- S. Zaroubi, Y. Hoffman. Reconstruction of the Initial Density Field. ApJ 416, 410 (1993).

- S. Deser, R. P. Woodard. Nonlocal Cosmology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 111301 (2007). [CrossRef]

- T. Koivisto. Nonlocal Modifications of Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 77, 123513 (2008).

- A. Kehagias, A. Riotto. Non-Markovian Cosmological Perturbations. Fortschr. Phys. 66, 1800052 (2018).

- E. Mottola. Gravitational Vacuum Polarisation and Memory. Phys. Rev. D 31, 754 (1985).

- L. Modesto, L. Rachwał. Nonlocal Quantum Gravity. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 26, 1730020 (2017). [CrossRef]

- A. Kovács et al. Galaxy Supervoids and the CMB. MNRAS 465, 4166 (2017).

- D. L. Wiltshire. Average Spatial Curvature from Structure Formation. Phys. Rev. D 80, 123512 (2009).

- A. Ashtekar, P. Singh. Loop Quantum Cosmology and Bounces. Class. Quantum Grav. 28, 213001 (2011).

- M. Gasperini, G. Veneziano. Pre-Big-Bang String Cosmology. Phys. Rep. 373, 1 (2003). [CrossRef]

- P. Steinhardt, N. Turok. The Cyclic Universe. Science 296, 1436 (2002).

- E. Komatsu. Primordial Non-Gaussianity. Class. Quantum Grav. 27, 124010 (2010).

- A. Riotto. Primordial Non-Gaussianities and Structure. Lect. Notes Phys. 738, 1 (2008).

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 Results: Non-Gaussianity. Astron. Astrophys. 641, A9 (2020).

- C. Copi et al. Large-Angle CMB Anomalies: A Review. Class. Quantum Grav. 34, 084005 (2017).

- H. K. Eriksen et al. Asymmetries in the CMB. ApJ 605, 14 (2004).

- B. Falck, M. Neyrinck. Topology of Cosmic Density Fields. MNRAS 436, 2494 (2013).

- E. Platen et al. Void Topology and the Cosmic Skeleton. MNRAS 380, 551 (2007).

- M. Räsänen. Backreaction: Explained. Class. Quantum Grav. 28, 164008 (2011).

- T. Buchert. Backreaction and the Evolution of Cosmic Structure. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 40, 467 (2008).

- D. J. Schwarz et al. CMB Anomalies after Planck. Class. Quantum Grav. 33, 184001 (2016). [CrossRef]

- M. Sahlén. Cosmic Voids as Diagnostics of the Early Universe. Phys. Rev. D 99, 063525 (2019).

- A. Pontzen, F. Governato. Inversion in Cosmology and Structure Transformation. Nature 506, 171 (2014).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).