Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Chemicals

2.2. Fractionation

2.3. ATR-FTIR Measurements and Data Processing

2.4. Fluorescence Measurements

2.5. Other Equipment and Measurements

2.6. Correlation and 2D-COS Analysis

2.7. Experimental Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

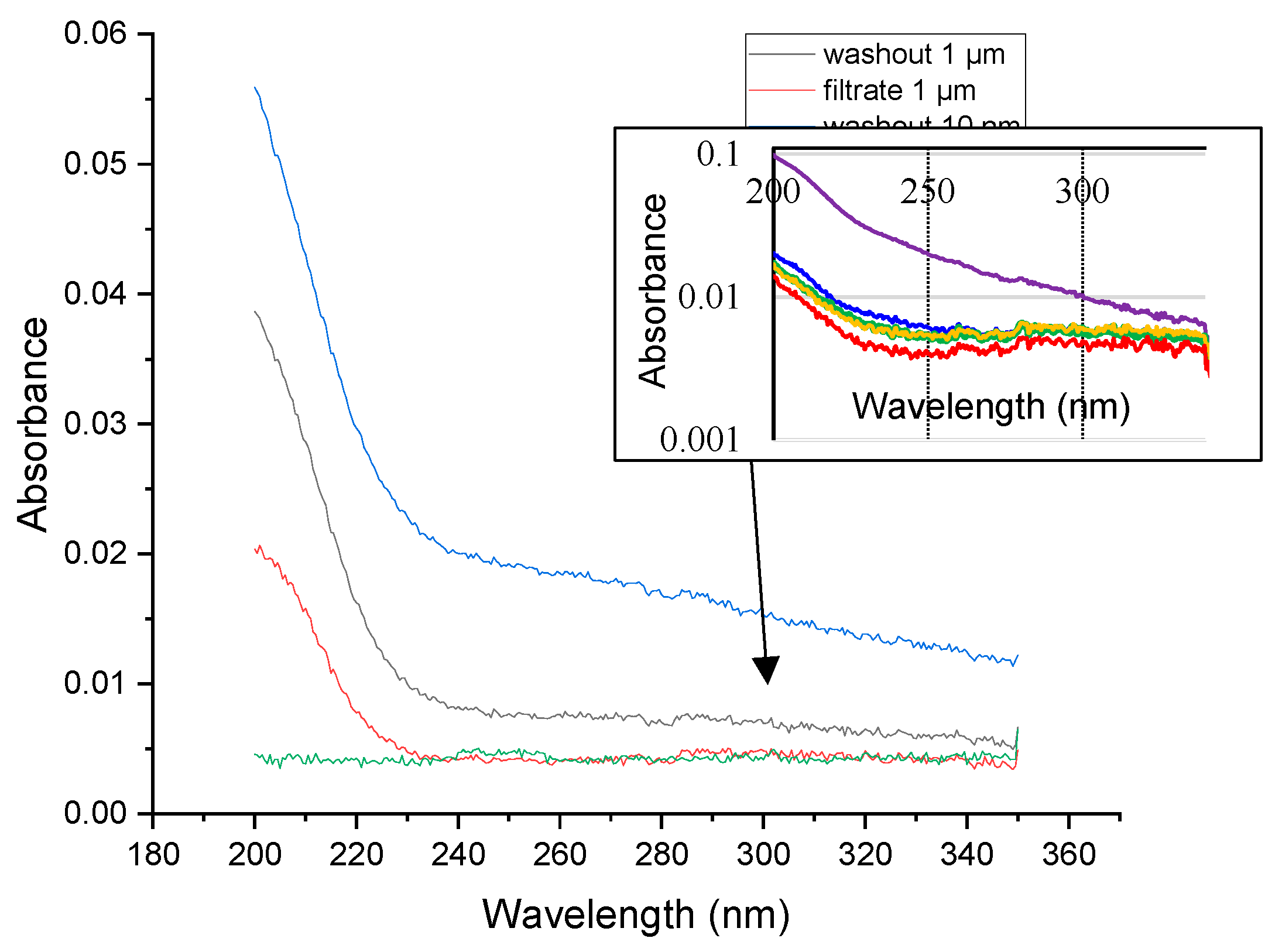

3.1. Degree of Plasticizer Extraction from Membranes During Membrane Filtration

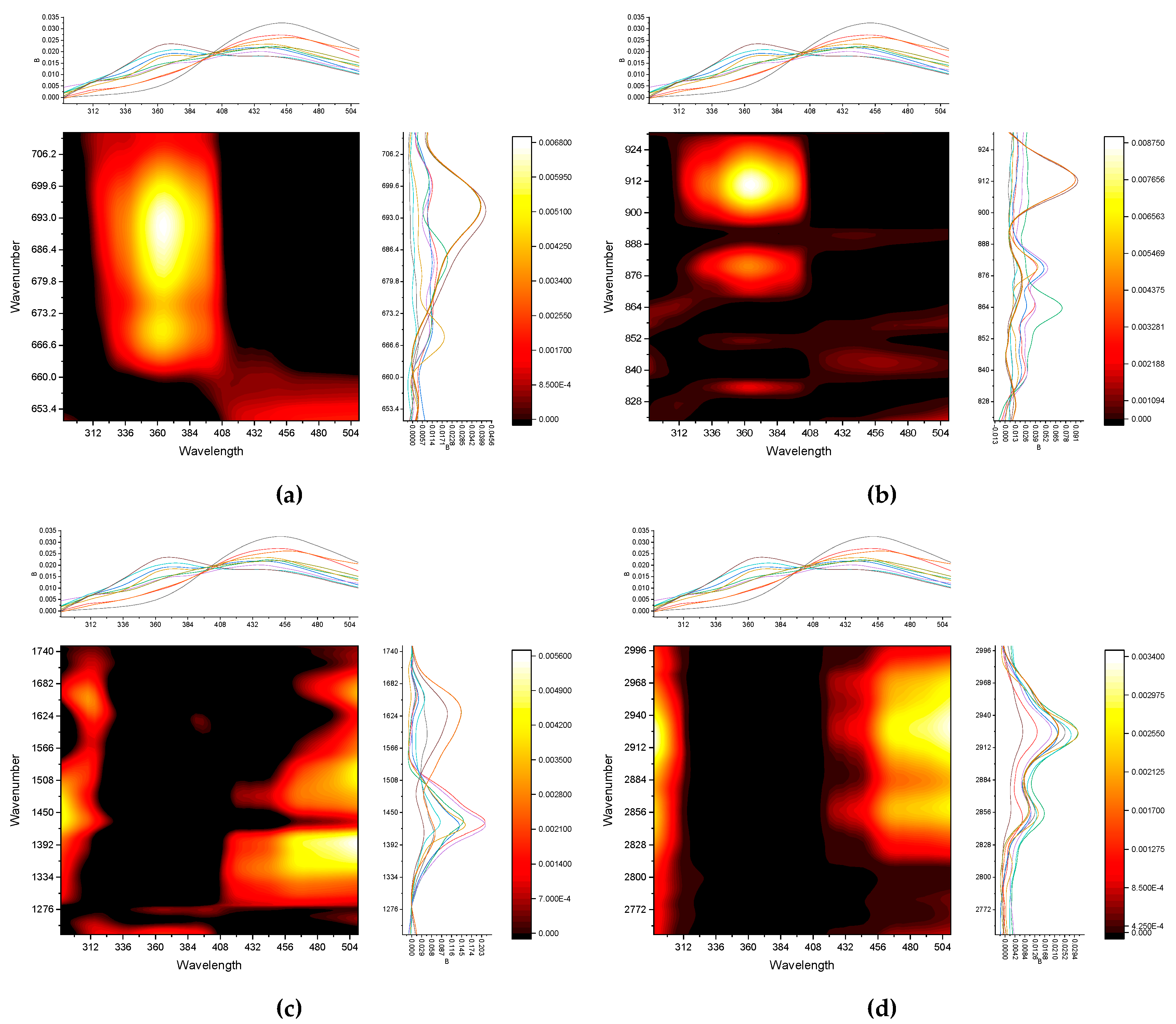

3.2. FTIR Analysis

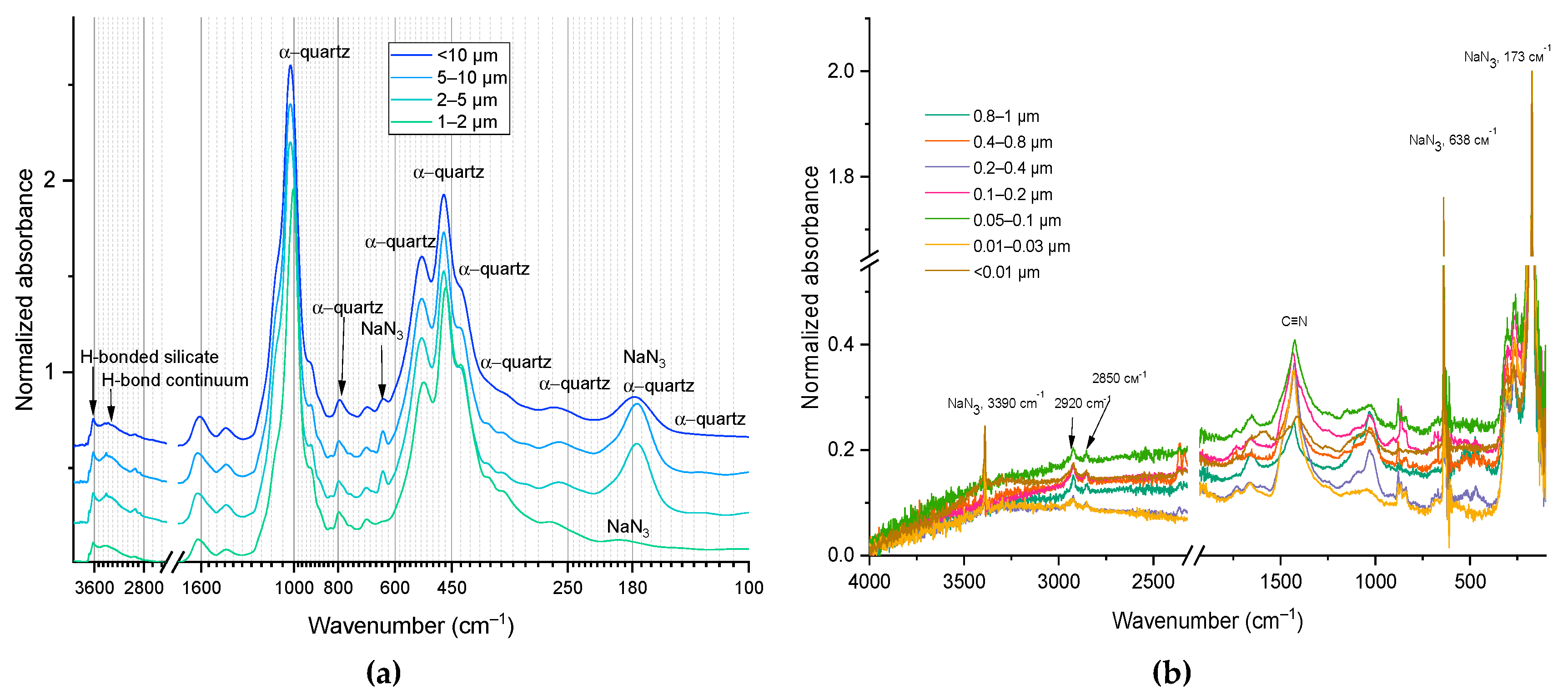

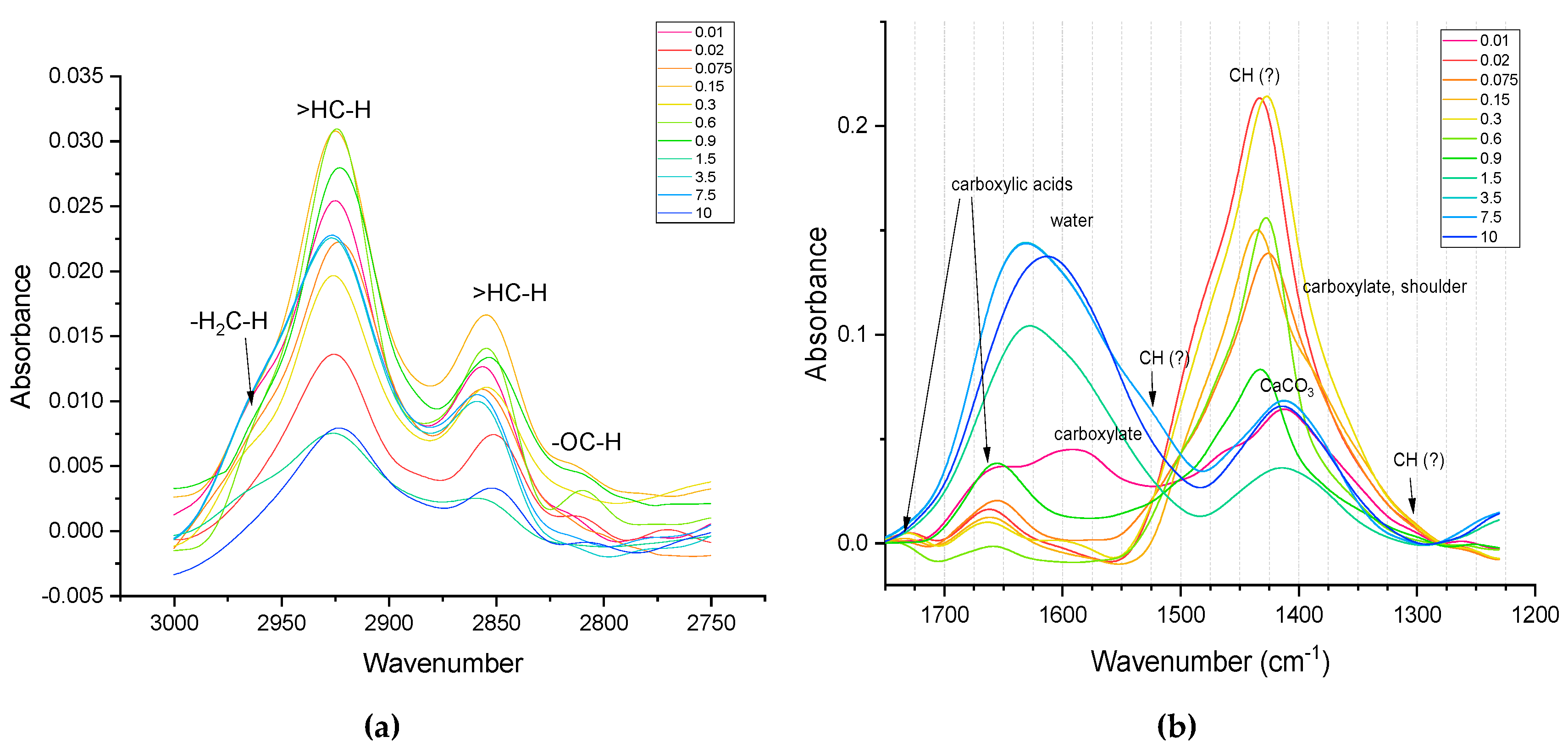

3.2.1. Hydrogen-Bond and CH-Regions (4000–2800 cm–1)

3.2.2. SOM Region (1700–1170 cm–1)

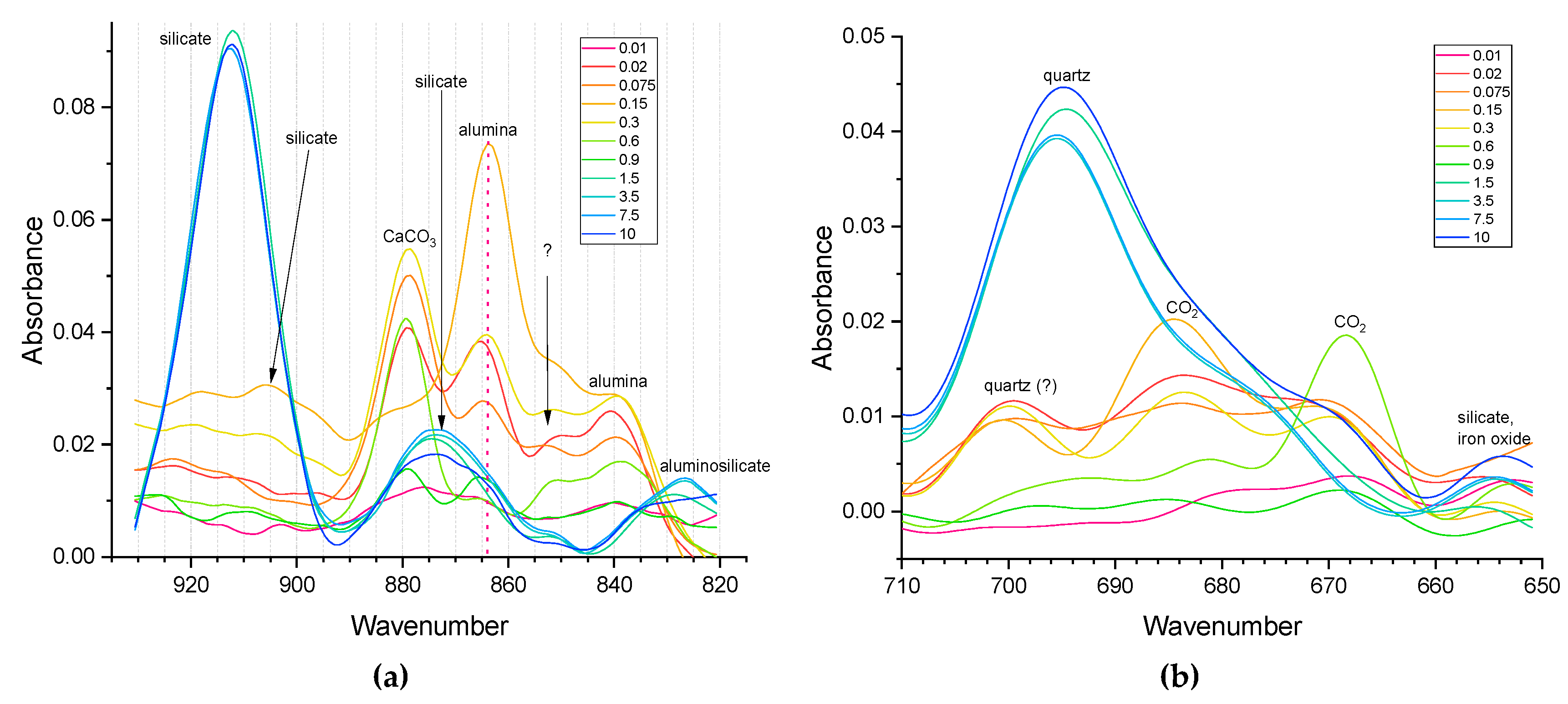

3.2.3. Matrix II and I regions (1170–800 and 800–150 cm–1)

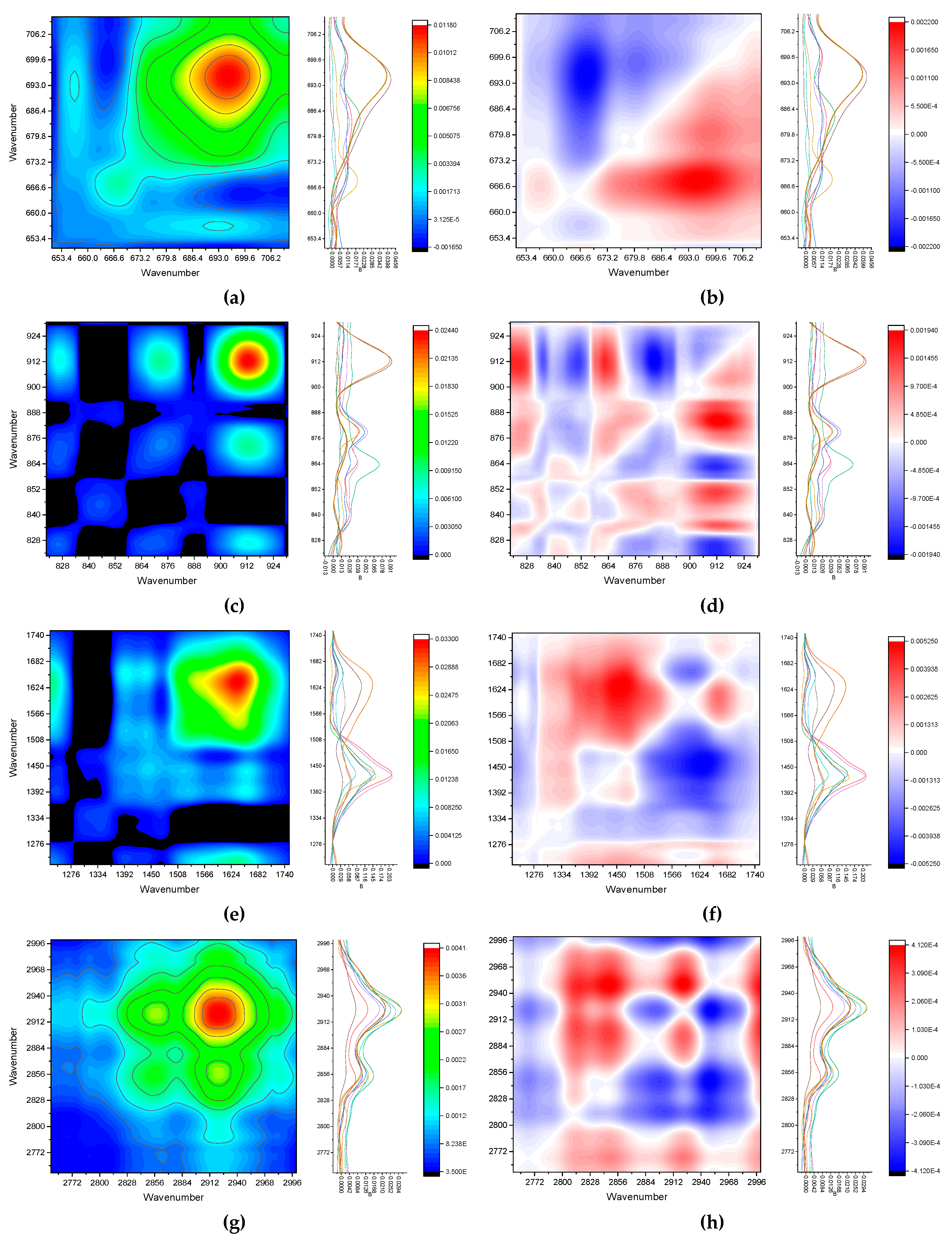

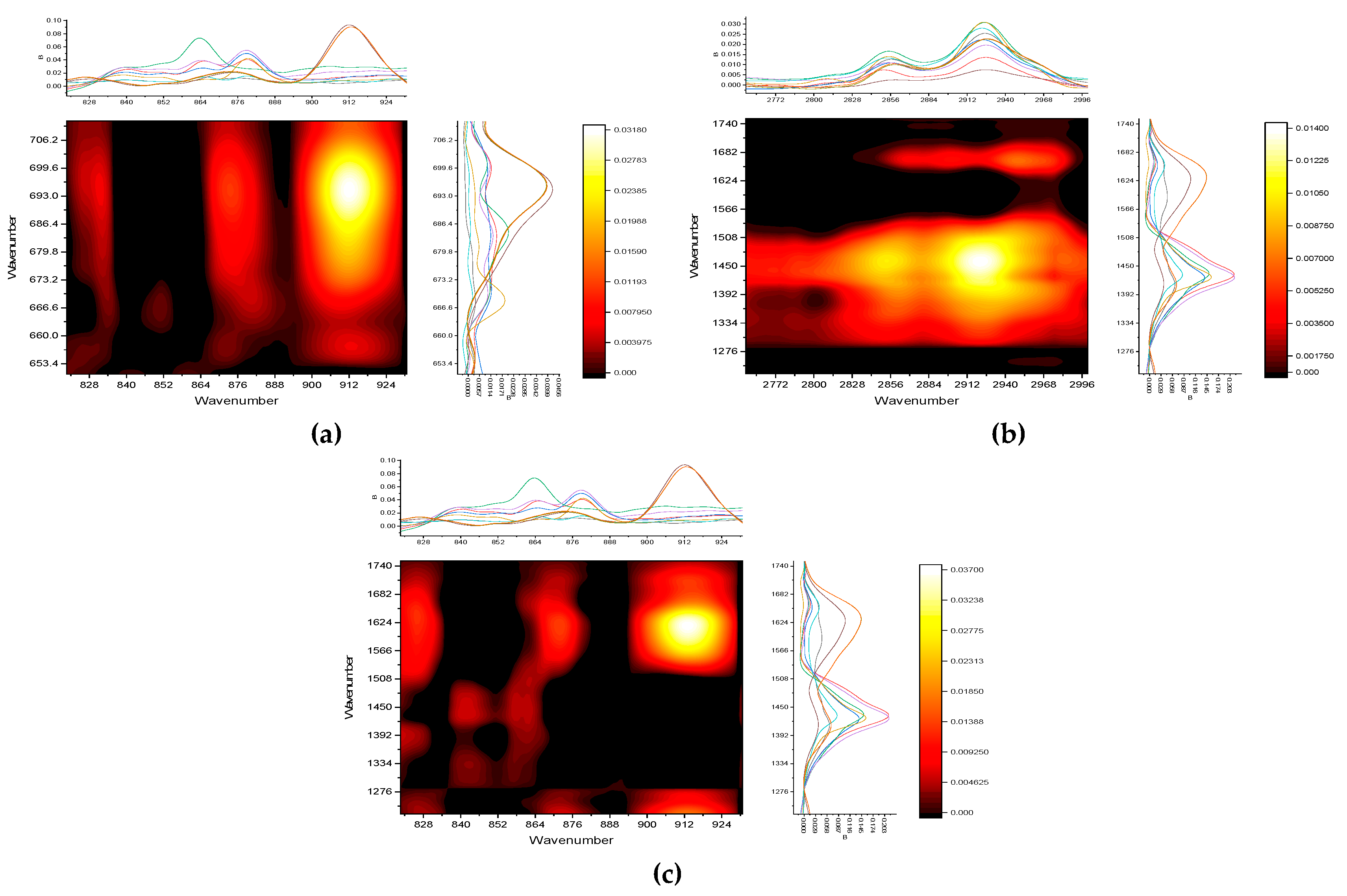

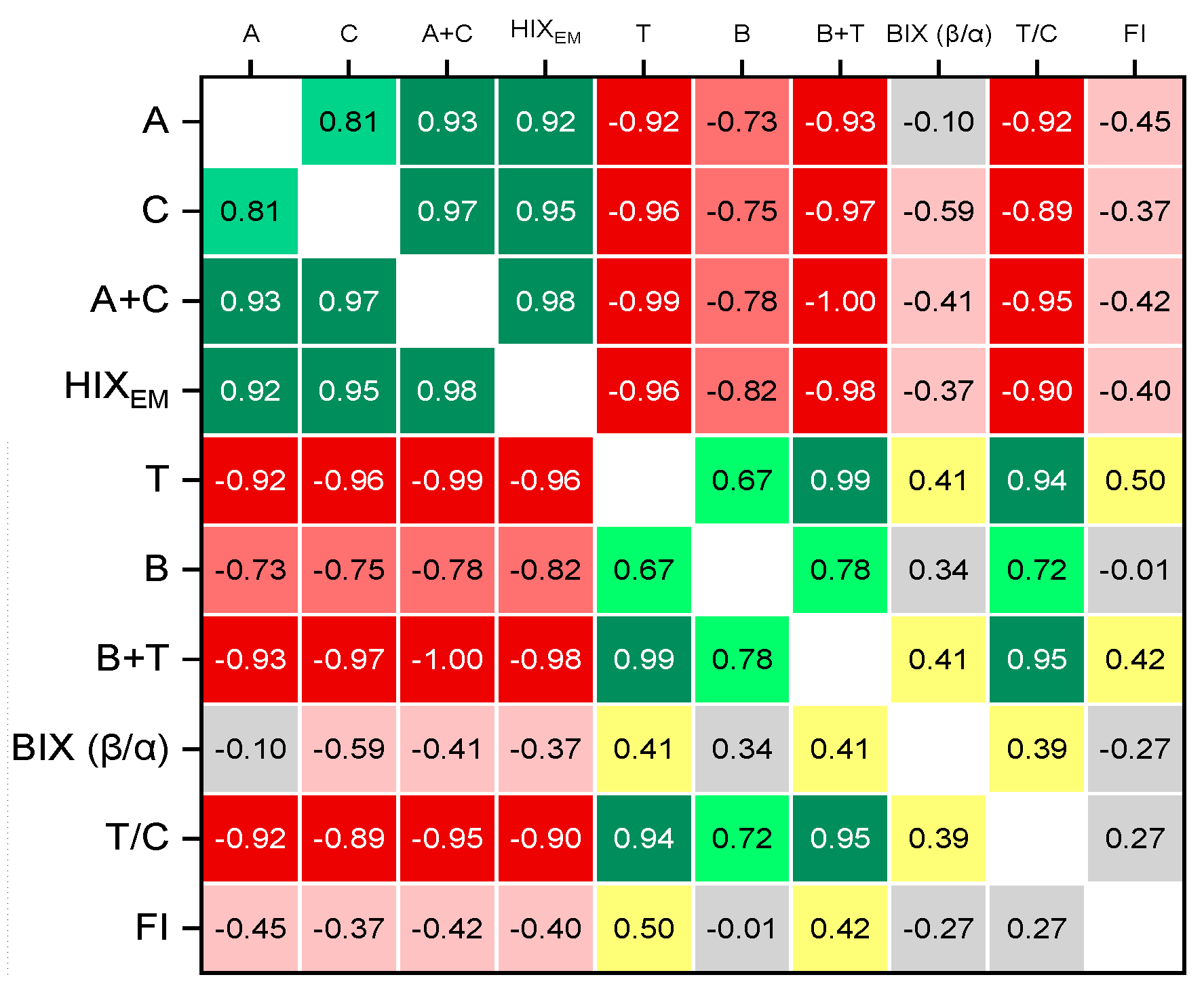

3.3. IR Correlations

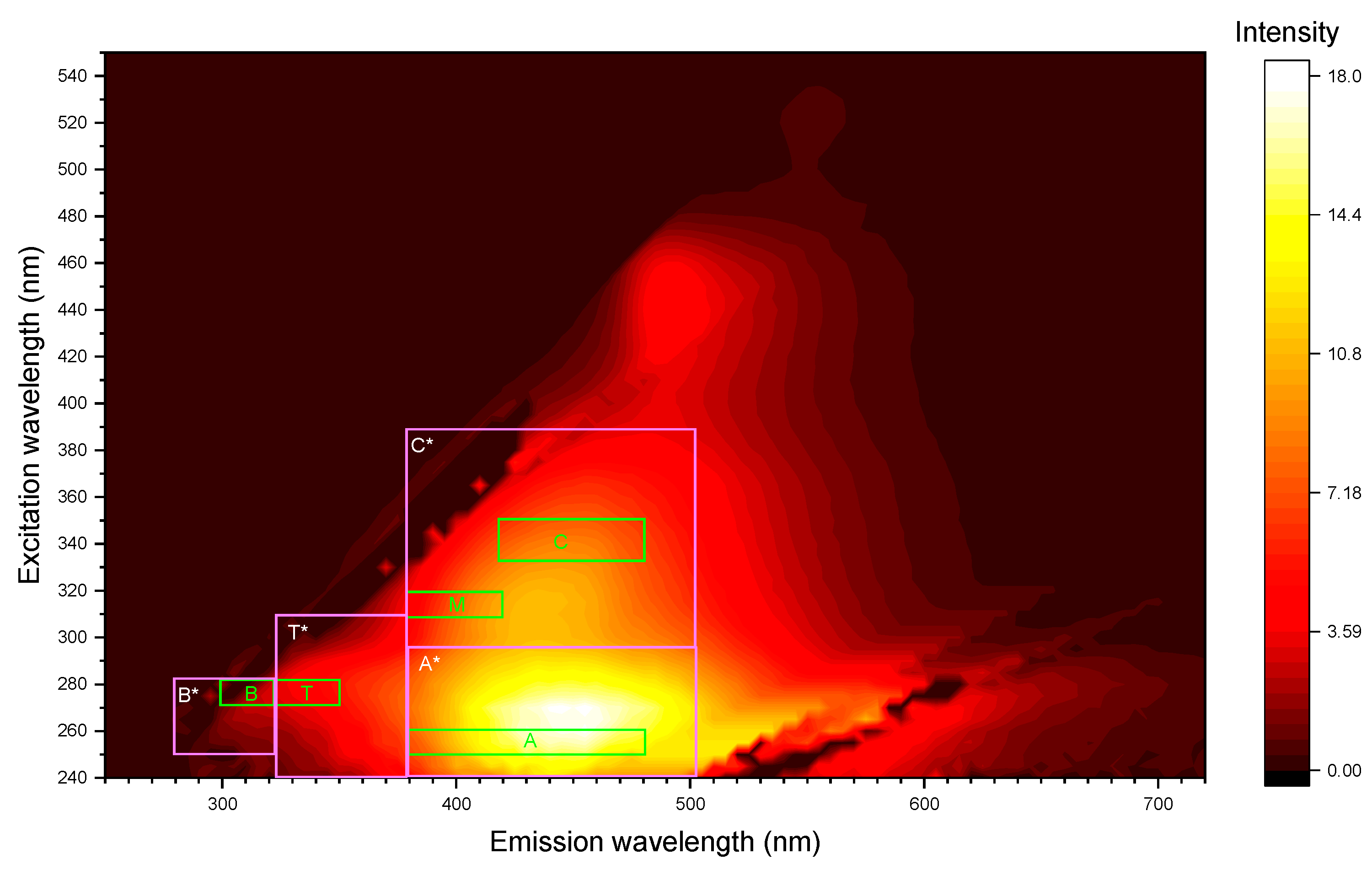

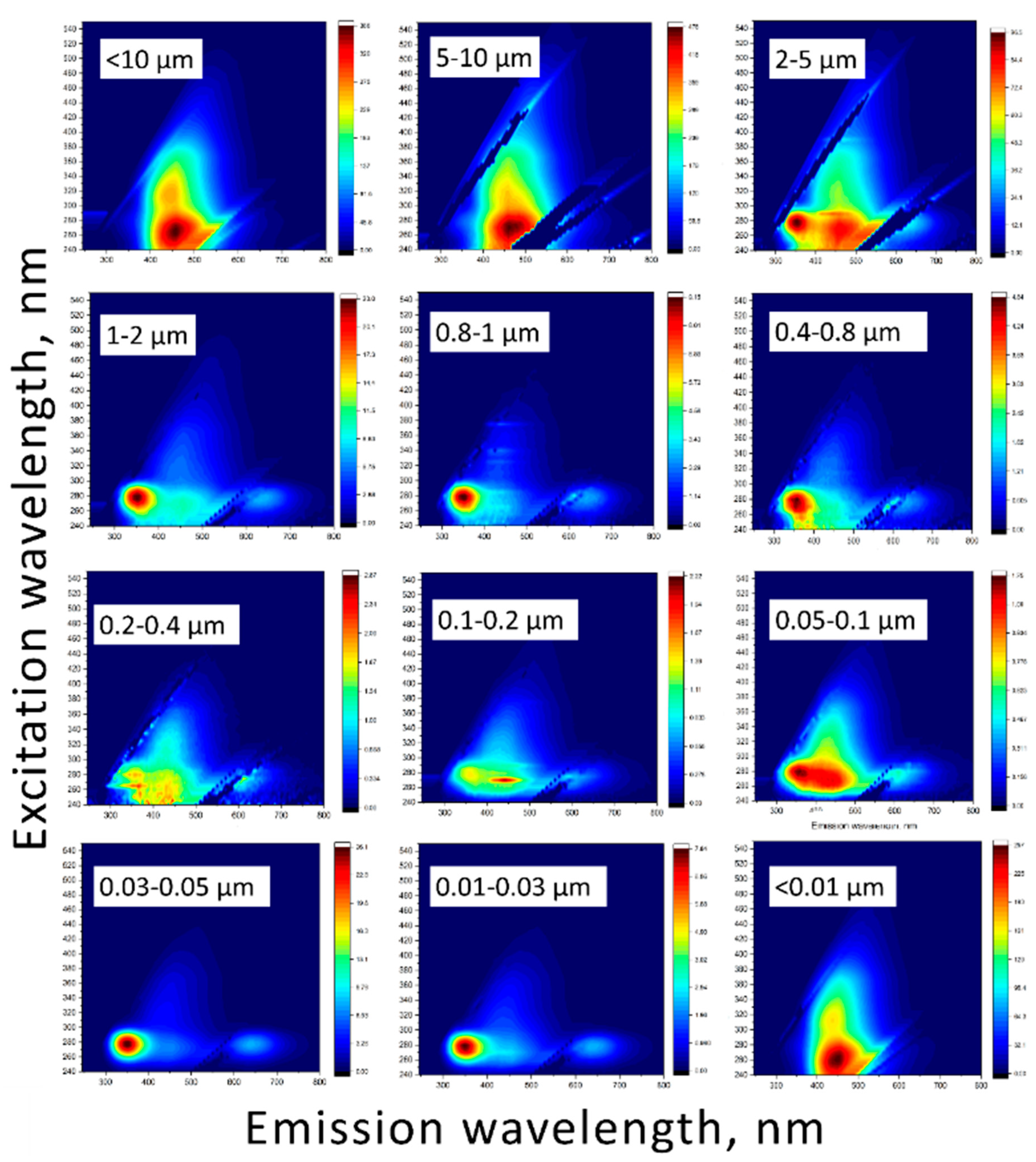

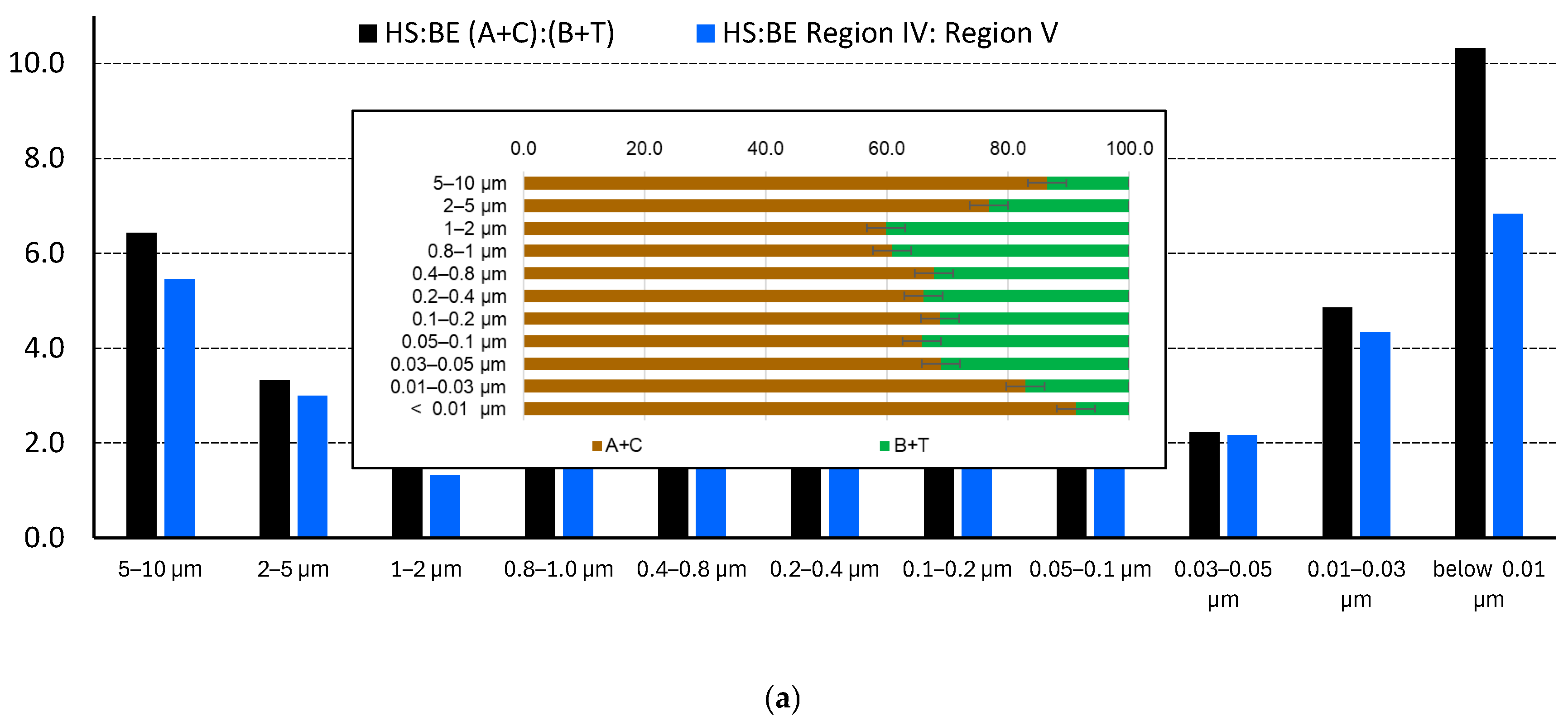

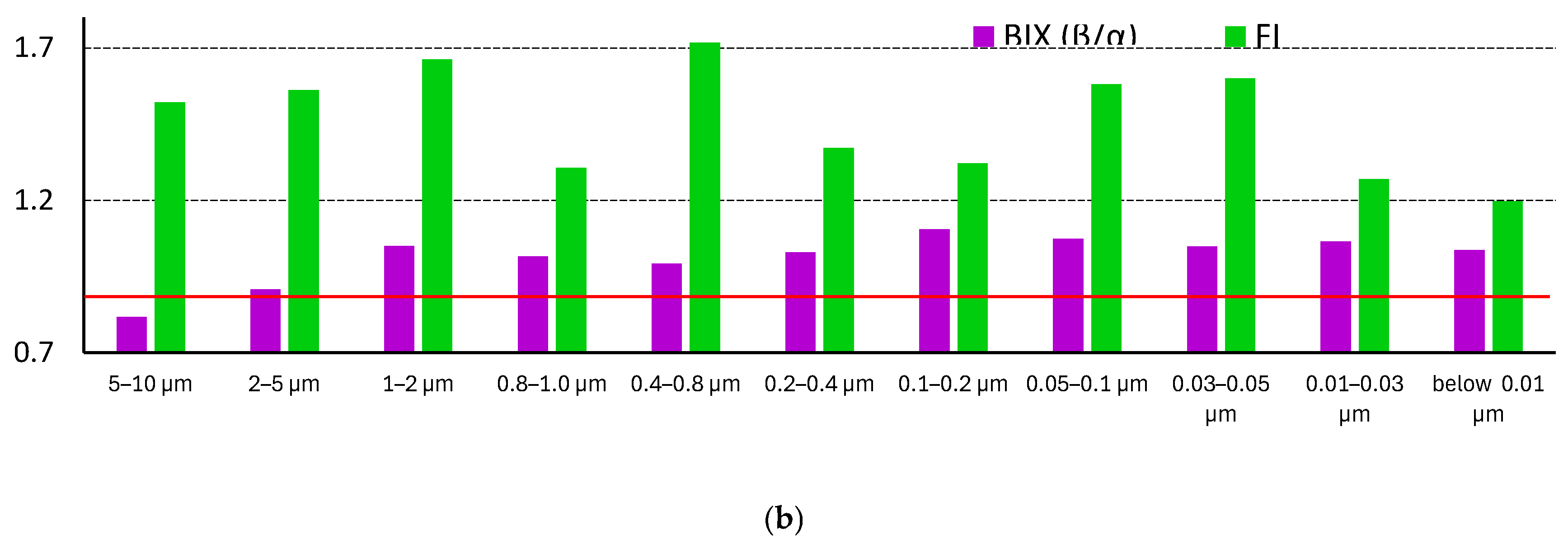

3.4. Fluorescence Measurements

3.5. IR–Fluorometry Heterospectral Correlations

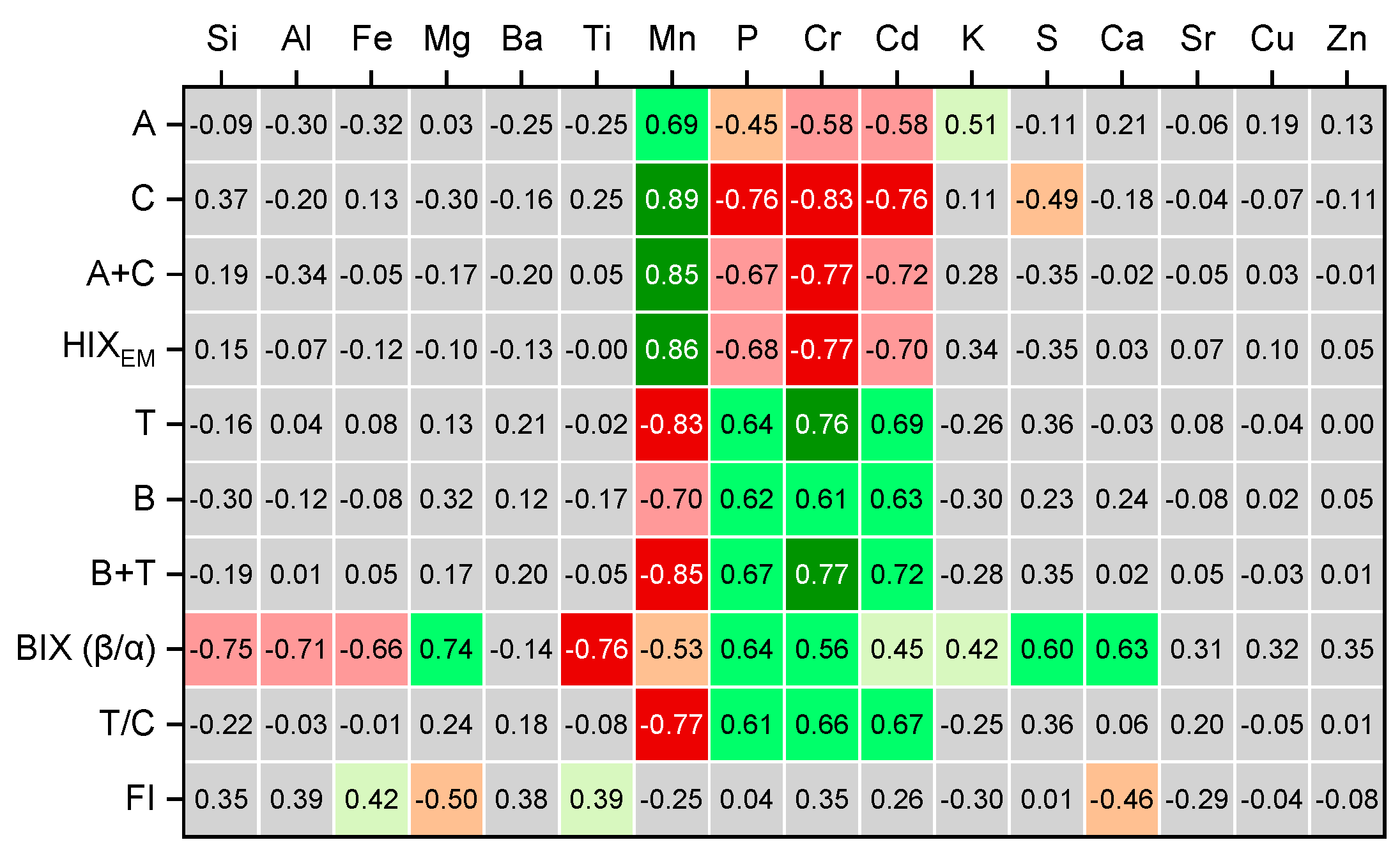

3.6. Correlations of Fluorescence Indexes with ICP-AES

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D-COS | two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy |

| ATR | attenuated total reflection |

| DOM | dissolved organic matter |

| EEM | excitation–emission matrix |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared (spectroscopy) |

| HS | humic substances |

| ICP-AES | atomic-emission spectroscopy with inductively coupled plasma |

| SOM | soil organic matter |

| WEOM | water-extractable organic matter |

Appendix A: Methodological Features of the Analysis of Size Fractions of Soil Water-Soluble Matter Using ATR IR Spectroscopy

References

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.C.; Wang, Y.; Dzakpasu, M. Characterization and biogeochemical implications of dissolved organic matter in aquatic environments. J Environ Manage 2021, 294, 113041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavanova, E.I. Dissolved organic matter: Fractional composition and sorbability by the soil solid phase (Review of literature). Eurasian Soil Sci. 2013, 46, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shi, Z.; Ye, Q.; Liang, Y.; Liu, M.; Dang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C. Chemodiversity of Soil Dissolved Organic Matter. Environ Sci Technol 2020, 54, 6174–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenopoulos, M.A.; Barnes, R.T.; Boodoo, K.S.; Butman, D.; Catalán, N.; D’Amario, S.C.; Fasching, C.; Kothawala, D.N.; Pisani, O.; Solomon, C.T.; et al. How humans alter dissolved organic matter composition in freshwater: Relevance for the Earth’s biogeochemistry. Biogeochemistry 2021, 154, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Ren, T.; Lei, M.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J. Tillage and straw-returning practices effect on soil dissolved organic matter, aggregate fraction and bacteria community under rice-rice-rapeseed rotation system. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 287, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielnik, L.; Hewelke, E.; Weber, J.; Oktaba, L.; Jonczak, J.; Podlasiński, M. Changes in the soil hydrophobicity and structure of humic substances in sandy soil taken out of cultivation. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2021, 319, 107554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, N.A.; Kholodov, V.A.; Farkhadov, Y.R.; Ziganshina, A.R.; Zavarzina, A.G.; Karpukhin, M.M. Dissolved Organic Matter of Chernozems of Different Use: The Relationship of Structural Features and Mineral Composition. Mosc. Univ. Soil Sci. Bull. 2024, 79, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, H.; Jia, Q.; Liu, H.; Ye, J. Interactions of anthropogenic and terrestrial sources drive the varying trends in molecular chemodiversity profiles of DOM in urban storm runoff, compared to land use patterns. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, G.; Li, F.; Chen, H.; Leng, Y. The nature of dissolved organic matter determines the biosorption capacity of Cu by algae. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Seo, H.; Han, H.; Seo, J.; Kim, T.; Kim, G. Conservative behavior of terrestrial trace elements associated with humic substances in the coastal ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 308, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Huang, W.; Weintraub-Leff, S.R.; Hall, S.J. Where and why do particulate organic matter (POM) and mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) differ among diverse soils? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 108756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvasce, M.; Zsolnay, A.; D’Orazio, V.; Lopez, R.; Miano, T.M. Characterization of water extractable organic matter in a deep soil profile. Chemosphere 2006, 62, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, O.P.; Kallenbach, C.M.; Wallenstein, M.D. Distribution of soil organic matter fractions are altered with soil priming. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 164, 108494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Ovseenko, S.T.; Odelskii, A.; Proskurnin, M.A. Element Composition of Fractionated Water-Extractable Soil Colloidal Particles Separated by Track-Etched Membranes. Agrochemicals 2023, 2, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashentseva, A.A.; Sutekin, D.S.; Rakisheva, S.R.; Barsbay, M. Composite Track-Etched Membranes: Synthesis and Multifaced Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Keçeci, K. Review—Track-Etched Nanoporous Polymer Membranes as Sensors: A Review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 037543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.A.; Bernal, E.E.; Yaroshchuk, A.; Bruening, M.L. Separation of ions using polyelectrolyte-modified nanoporous track-etched membranes. Langmuir 2013, 29, 10287–10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grooth, J.; Oborný, R.; Potreck, J.; Nijmeijer, K.; de Vos, W.M. The role of ionic strength and odd–even effects on the properties of polyelectrolyte multilayer nanofiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 475, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, A.; Vacher, L.; Saubusse, S.; Etcheber, H.; Abril, G.; Relexans, S.; Ibalot, F.; Parlanti, E. New insights into the size distribution of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in estuarine waters. Org. Geochem. 2010, 41, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhang, S.; Ruan, L.; Yang, M.; Shi, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, W. Evaluating Soil Dissolved Organic Matter Extraction Using Three-Dimensional Excitation-Emission Matrix Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Pedosphere 2017, 27, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, Q.V.; Hur, J. Further insight into the roles of the chemical composition of dissolved organic matter (DOM) on ultrafiltration membranes as revealed by multiple advanced DOM characterization tools. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, K.; Shen, Y.; Sun, J.; Liang, S.; Fan, H.; Tan, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Waite, T.D. Correlating fluorescence spectral properties with DOM molecular weight and size distribution in wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2018, 4, 1933–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Wang, P.; Hu, B.; Shi, Y. Investigation on the effects of sediment resuspension on the binding of colloidal organic matter to copper using fluorescence techniques. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.S.; Huang, W.S.; Hsu, L.F.; Yeh, Y.L.; Chen, T.C. Fluorescence of Size-Fractioned Humic Substance Extracted from Sediment and Its Effect on the Sorption of Phenanthrene. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, R.S.; Baker, A.; McKnight, D.M.; Miller, M.P. Fluorescence Indices and Their Interpretation. In Aquatic Organic Matter Fluorescence, Coble, P.G., Lead, J., Baker, A., Reynolds, D.M., Spencer, R.G.M., Eds.; Cambridge Environmental Chemistry Series; Cambridge Univ Press: Cambridge, 2014; pp. 303–338. [Google Scholar]

- Zsolnay, Á. Dissolved organic matter: Artefacts, definitions, and functions. Geoderma 2003, 113, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Westerhoff, P.; Leenheer, J.A.; Booksh, K. Fluorescence excitation-emission matrix regional integration to quantify spectra for dissolved organic matter. Environ Sci Technol 2003, 37, 5701–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.; Gjessing, E.T.; Lahtinen, T.; Hed, L.; Bhatnagar, A.; Sillanpaa, M. An overview of the methods used in the characterisation of natural organic matter (NOM) in relation to drinking water treatment. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 1431–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillanpää, M.; Matilainen, A.; Lahtinen, T. Characterization of NOM. In Natural Organic Matter in Water, Sillanpää, M., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: 2015; pp. 17–53.

- Bro, R. Multivariate calibration. Anal. Chim. Acta 2003, 500, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Hur, J. Conservative behavior of fluorescence EEM-PARAFAC components in resin fractionation processes and its applicability for characterizing dissolved organic matter. Water Res. 2015, 83, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Linker, R.; Shaviv, A. Characterization of soils using photoacoustic mid-infrared spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2007, 61, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Linker, R.; Shaviv, A. Identification of agricultural Mediterranean soils using mid-infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy. Geoderma 2008, 143, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhu, A.; Zhang, J. Determination of soil properties using Fourier transform mid-infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy. Vib. Spectrosc 2009, 49, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. Photoacoustic and photothermal methods in spectroscopy and characterization of soils and soil organic matter. Photoacoustics 2020, 17, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.; Rogova, O.; Proskurnin, M. Temperature Dependences of IR Spectra of Humic Substances of Brown Coal. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpukhina, E.; Mikheev, I.; Perminova, I.; Volkov, D.; Proskurnin, M. Rapid quantification of humic components in concentrated humate fertilizer solutions by FTIR spectroscopy. J. Soils Sed. 2018, 19, 2729–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguta, P.; Sokolowska, Z.; Skic, K. Use of thermal analysis coupled with differential scanning calorimetry, quadrupole mass spectrometry and infrared spectroscopy (TG-DSC-QMS-FTIR) to monitor chemical properties and thermal stability of fulvic and humic acids. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morra, M.J.; Marshall, D.B.; Lee, C.M. FT--IR analysis of aldrich humic acid in water using cylindrical internal reflectance. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2008, 20, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatzber, M.; Stemmer, M.; Spiegel, H.; Katzlberger, C.; Haberhauer, G.; Mentler, A.; Gerzabek, M.H. FTIR--spectroscopic characterization of humic acids and humin fractions obtained by advanced NaOH, Na4P2O7, and Na2CO3 extraction procedures. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2007, 170, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanykova, N.; Petrova, Y.; Kostina, J.; Kozlova, E.; Leushina, E.; Spasennykh, M. Study of Organic Matter of Unconventional Reservoirs by IR Spectroscopy and IR Microscopy. Geosciences 2021, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Kabała, C.; Łabaz, B.; Mituła, P.; Bednik, M.; Medyńska-Juraszek, A. Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy Supports Identification of the Origin of Organic Matter in Soils. Land 2021, 10, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolverton, P.; Dragila, M.I. Characterization of hydrophobic soils: A novel approach using mid-infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2014, 68, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Cai, X.; Tan, B.; Zhou, S.; Xing, B. Molecular insights into reversible redox sites in solid-phase humic substances as examined by electrochemical in situ FTIR and two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Chem. Geol. 2018, 494, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaný, M.; Jankovič, Ľ.; Madejová, J. Structural characterization of organo-montmorillonites prepared from a series of primary alkylamines salts: Mid-IR and near-IR study. Applied Clay Science 2019, 176, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejová, J.; Sekeráková, Ľ.; Bizovská, V.; Slaný, M.; Jankovič, Ľ. Near-infrared spectroscopy as an effective tool for monitoring the conformation of alkylammonium surfactants in montmorillonite interlayers. Vib. Spectrosc 2016, 84, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.; Rogova, O.; Proskurnin, M. Organic Matter and Mineral Composition of Silicate Soils: FTIR Comparison Study by Photoacoustic, Diffuse Reflectance, and Attenuated Total Reflection Modalities. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, W.; Franchini, J.C.; de Fatima Guimaraes, M.; Filho, J.T. Spectroscopic characterization of humic and fulvic acids in soil aggregates, Brazil. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proskurnin, M.A.; Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B. Two-Dimensional Correlation IR Spectroscopy of Humic Substances of Chernozem Size Fractions of Different Land Use. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoshein, P.K.; Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. FTIR Photoacoustic and ATR Spectroscopies of Soils with Aggregate Size Fractionation by Dry Sieving. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 2177–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, S.W.; Croué, J.P.; Buffle, J.; Perdue, E.M. Three approaches for characterizing NOM. Journal AWWA 1996, 88, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbtbraun, G. Basic characterization of Norwegian NOM samples ? Similarities and differences. Environ. Int. 1999, 25, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.S.; Proskurnin, M.A.; Korobov, M.V. Elemental analysis of nanodiamonds by inductively-coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy. Carbon 2014, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpukhina, E.A.; Vlasova, E.A.; Volkov, D.S.; Proskurnin, M.A. Comparative Study of Sample-Preparation Techniques for Quantitative Analysis of the Mineral Composition of Humic Substances by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Xing, J.; Zhu, S.; Li, X. On-site rapid quantitative assessment of wet soil nutrients based on laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy fingerprint spectral lines corrected by near-infrared spectroscopy. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Zhu, S.; Li, X. Comparing atomic spectroscopy, molecular spectroscopy and multi-source spectroscopy synergetic fusion for quantitation of total potassium in culture substrates. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2025, 40, 1536–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, T.G.; Pitts, K.; Lewis, S.W. Multimodal spectroscopy with chemometrics for the forensic analysis of Western Australian sandy soils. Forensic Chemistry 2022, 28, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, E.; Greene, D.; O’Donnell, C.; O’Shea, N.; Fenelon, M.A. Spectroscopic technologies and data fusion: Applications for the dairy industry. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1074688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, I. Generalized Two-Dimensional Correlation Method Applicable to Infrared, Raman, and other Types of Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 1993, 47, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, M.A. Interpretation of Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectra: Science or Art? Appl. Spectrosc. 1998, 52, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Buchet, R.; Fringeli, U.P. 2D-FTIR ATR Spectroscopy of Thermo-Induced Periodic Secondary Structural Changes of Poly-(L)-lysine: A Cross-Correlation Analysis of Phase-Resolved Temperature Modulation Spectra; 1996; Volume 100, pp. 1 0810–10825.

- Noda, I.; Liu, Y.; Ozaki, Y. Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy Study of Temperature-Dependent Spectral Variations of N -Methylacetamide in the Pure Liquid State. 1. Two-Dimensional Infrared Analysis; 1996; Volume 100, pp. 8674–8680.

- Shin, H.; Jung, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Chang, T.; Ozaki, Y.; Bin Kim, S. Structural Comparison of Langmuir−Blodgett and Spin-Coated Films of Poly(tert-butyl methacrylate) by External Reflection FTIR Spectroscopy and Two-Dimensional Correlation Analysis; 2002; Volume 18.

- Zhang, J.; Tsuji, H.; Noda, I.; Ozaki, Y. Weak Intermolecular Interactions during the Melt Crystallization of Poly(l-lactide) Investigated by Two-Dimensional Infrared Correlation Spectroscopy; 2004; Volume 108.

- Yang, I.-S.; Jung, Y.M.; Bin Kim, S.; V. Klein, M. Two-Dimensional Correlation Analysis of Superconducting YNi2B2C Raman Spectra; 2005; Volume 19, pp. 281–284. 19.

- Jeong Kim, H.; Bin Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y.M.; Yeol Ryu, D.; A Lavery, K.; P. Russell, T. Phase Behavior of a Weakly Interacting Block Copolymer by Temperature-Dependent FTIR Spectroscopy; 2006; Volume 39.

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.R.; Ozaki, Y. Two-dimensional visible/near-infrared correlation spectroscopy study of thermal treatment of chicken meats. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Shimada, S.; Saitoh, R.; Noda, I. Transient 2D IR Correlation Spectroscopy of the Photopolymerization of Acrylic and Epoxy Monomers. Appl. Spectrosc. 1993, 47, 1337–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Murayama, K.; Myojo, Y.; Tsenkova, R.; Hayashi, N.; Ozaki, Y. Two-Dimensional Fourier Transform Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study of Heat Denaturation of Ovalbumin in Aqueous Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 6655–6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Enderlein, J. Advanced fluorescence correlation spectroscopy for studying biomolecular conformation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 70, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Hao, Y.; Gao, H.; Yu, H.; Li, Q. Applying synchronous fluorescence spectra with Gaussian band fitting and two-dimensional correlation to characterize structural composition of DOM from soils in an aquatic-terrestrial ecotone. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.-M.; Dong, G.-M.; Yang, R.-J.; Li, X.-C.; Chen, Q. Study on fluorescence interaction between humic acid and PAHs based on two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1217, 128428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, I.; Dowrey, A.E.; Marcott, C. Recent Developments in Two-Dimensional Infrared (2D IR) Correlation Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 1993, 47, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, I.; Dowrey, A.E.; Marcott, C.; Story, G.M.; Ozaki, Y. Generalized Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2000, 54, 236A–248A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, I.; Ozaki, Y. Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy—Applications in Vibrational and Optical Spectroscopy. 2004.

- Noda, I. Advances in two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Vib. Spectrosc 2004, 36, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchet, R.; Wu, Y.; Lachenal, G.; Raimbault, C.; Ozaki, Y. Selecting Two-Dimensional Cross-Correlation Functions to Enhance Interpretation of Near-Infrared Spectra of Proteins. Appl. Spectrosc. 2001, 55, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, I. Progress in two-dimensional (2D) correlation spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2006, 799, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Qu, F.; Zhang, X.; Shao, S.; Rong, H.; Liang, H.; Bai, L.; Ma, J. Development of correlation spectroscopy (COS) method for analyzing fluorescence excitation emission matrix (EEM): A case study of effluent organic matter (EfOM) ozonation. Chemosphere 2019, 228, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Cheng, X.; Zheng, D.; Song, H.; Han, P.; Yuen, P. Prediction of the Soil Organic Matter (SOM) Content from Moist Soil Using Synchronous Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy (2D-COS) Analysis. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Habibul, N.; Liu, X.Y.; Sheng, G.P.; Yu, H.Q. FTIR and synchronous fluorescence heterospectral two-dimensional correlation analyses on the binding characteristics of copper onto dissolved organic matter. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49, 2052–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, Y.C.; Shen, Q.R. Multiple fluorescence labeling and two dimensional FTIR-13C NMR heterospectral correlation spectroscopy to characterize extracellular polymeric substances in biofilms produced during composting. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, 9224–9231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A.; Farkhodov, Y.R.; Markeeva, L.B. Thermal stability of organic matter of typical chernozems under different land uses. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 197, 104500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlanti, E.; Wörz, K.; Geoffroy, L.; Lamotte, M. Dissolved organic matter fluorescence spectroscopy as a tool to estimate biological activity in a coastal zone submitted to anthropogenic inputs. Org. Geochem. 2000, 31, 1765–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coble, P.G. Characterization of marine and terrestrial DOM in seawater using excitation-emission matrix spectroscopy. Mar. Chem. 1996, 51, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsolnay, A.; Baigar, E.; Jimenez, M.; Steinweg, B.; Saccomandi, F. Differentiating with fluorescence spectroscopy the sources of dissolved organic matter in soils subjected to drying. Chemosphere 1999, 38, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T. Fluorescence inner-filtering correction for determining the humification index of dissolved organic matter. Environ Sci Technol 2002, 36, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, A.; Vacher, L.; Relexans, S.; Saubusse, S.; Froidefond, J.M.; Parlanti, E. Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Org. Geochem. 2009, 40, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.F.; Xenopoulos, M.A. Effects of agricultural land use on the composition of fluvial dissolved organic matter. Nature Geoscience 2008, 2, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.M.; Boyer, E.W.; Westerhoff, P.K.; Doran, P.T.; Kulbe, T.; Andersen, D.T. Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2001, 46, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, R.M.; McKnight, D.M. Fluorescence spectroscopy reveals ubiquitous presence of oxidized and reduced quinones in dissolved organic matter. Environ Sci Technol 2005, 39, 8142–8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. Fluorescence excitation-emission matrix characterization of some sewage-impacted rivers. Environ Sci Technol 2001, 35, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.P.; McKnight, D.M.; Cory, R.M.; Williams, M.W.; Runkel, R.L. Hyporheic exchange and fulvic acid redox reactions in an Alpine stream/wetland ecosystem, Colorado Front Range. Environ Sci Technol 2006, 40, 5943–5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalbitz, K.; Angers, D.; Kaiser, K.; Chantigny, M. Extraction and Characterization of Dissolved Organic Matter. In Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis, Second Edition, Carter, M.R., Gregorich, E.G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chantigny, M.H.; Harrison-Kirk, T.; Curtin, D.; Beare, M. Temperature and duration of extraction affect the biochemical composition of soil water-extractable organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proskurnin, M.A.; Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B. Temperature Dependences of IR Spectral Bands of Humic Substances of Silicate-Based Soils. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoshein, P.K.; Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. FTIR photoacoustic spectroscopy for identification and assessment of soil components: Chernozems and their size fractions. Photoacoustics 2020, 18, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, S.; Ashiq, M.N.; Manzoor, S.; Ali, U.; Liaqat, R.; Algahtani, A.; Mujtaba, S.; Tirth, V.; Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Refat, M.S.; et al. Analysis and characterization of opto-electronic properties of iron oxide (Fe2O3) with transition metals (Co, Ni) for the use in the photodetector application. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 25, 6150–6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltre, C.; Bruun, S.; Du, C.; Thomsen, I.K.; Jensen, L.S. Assessing soil constituents and labile soil organic carbon by mid-infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.I. Vibrational Spectrum of Sodium Azide Single Crystals. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1964, 40, 3195–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attenuated Total Reflectance Infrared (ATR-IR) Spectrum of Sodium azide. Available online: https://spectrabase.com/spectrum/9i9JWsCo4j4 (accessed on 18.05).

- Koike, C.; Noguchi, R.; Chihara, H.; Suto, H.; Ohtaka, O.; Imai, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Tsuchiyama, A. Infrared Spectra of Silica Polymorphs and the Conditions of Their Formation. Astrophys. J. 2013, 778, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-G.; Nyman, G. The Infrared and Uv-Visible Spectra of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Containing (5, 7)-Member Ring Defects: A Theoretical Study. Astrophys. J. 2012, 751, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changwen, D.; Jianmin, Z.; Goyne, K.W. Organic and inorganic carbon in paddy soil as evaluated by mid-infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, S.; Tognonvi, M.T.; Gelet, J.L.; Soro, J.; Rossignol, S. Interactions between silica sand and sodium silicate solution during consolidation process. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2011, 357, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changwen, D.; Jing, D.; Jianmin, Z.; Huoyan, W.; Xiaoqin, C. Characterization of Greenhouse Soil Properties Using Mid-infrared Photoacoustic Spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Lett. 2011, 44, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, F.J.; Reeves, J.B.; Collins, H.P.; Paul, E.A. Chemical Differences in Soil Organic Matter Fractions Determined by Diffuse--Reflectance Mid--Infrared Spectroscopy. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, F.J.; Mikha, M.M.; Vigil, M.F.; Nielsen, D.C.; Benjamin, J.G.; Reeves, J.B. Diffuse-Reflectance Mid-infrared Spectral Properties of Soils under Alternative Crop Rotations in a Semi-arid Climate. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2011, 42, 2143–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, A.M.; Bowey, J.E. Quantitative Infrared Spectra of Hydrosilicates and Related Minerals. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 367, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Z. Optical interference in overtones and combination bands in α-quartz. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2003, 64, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejová, J.; Komadel, P. Baseline Studies of the Clay Minerals Society Source Clays: Infrared Methods. Clays Clay Miner. 2024, 49, 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.D.; Fraser, A.R. Infrared methods. In Clay Mineralogy: Spectroscopic and Chemical Determinative Methods, Wilson, M.J., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1994; pp. 11–67.

- Kronenberg, A.K. Chapter 4. Hydrogen Speciation and Chemical Weakening of Quartz. In Silica; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1994; pp. 123–176. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Janik, L.J.; Raupach, M. Diffuse reflectance infrared fourier transform (DRIFT) spectroscopy in soil studies. Soil Res. 1991, 29, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Vien, D.; Colthup, N.B.; Fateley, W.G.; Grasselli, J.G. The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Colthup, N.B.; Daly, L.H.; Wiberley, S.E. Introduction to Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy; Elsevier Science: 1990.

- Asselin, M.; Sandorfy, C. Anharmonicity and Hydrogen Bonding. The in-plane OH Bending and its Combination with the OH Stretching Vibration. Canadian Journal of Chemistry 1971, 49, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, J.A.N.; Su, G.J. Interpretation of the Infrared Spectra of Fused Silica. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1970, 53, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, W.G.; Kleinman, D.A. Infrared Lattice Bands of Quartz. Phys. Rev. 1961, 121, 1324–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, R.T.; Blair, N.E.; Masterson, A.L. Carbonate mineral identification and quantification in sediment matrices using diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, M.K.; Lopes, N.F.; Cenci, A.; Ketzer, J.M.M.; Einloft, S.; Dullius, J.; Ligabue, R. Influence of Alkaline Additives and Buffers on Mineral Trapping of CO2 under Mild Conditions. Chemical Engineering & Technology 2018, 41, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max, J.J.; Chapados, C. Isotope effects in liquid water by infrared spectroscopy. III. H2O and D2O spectra from 6000 to 0 cm(-1). J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 184505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, C.; Rovetta, T.; Licchelli, M.; Malagodi, M. Mid and Near-Infrared Reflection Spectral Database of Natural Organic Materials in the Cultural Heritage Field. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2018, 2018, 7823248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, S.; Anbalagan, G.; Pandi, S. Raman and infrared spectra of carbonates of calcite structure. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2006, 37, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myszka, B.; Schussler, M.; Hurle, K.; Demmert, B.; Detsch, R.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Wolf, S.E. Phase-specific bioactivity and altered Ostwald ripening pathways of calcium carbonate polymorphs in simulated body fluid. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 18232–18244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogovska, N.; Laird, D.A.; Chiou, C.-P.; Bond, L.J. Development of field mobile soil nitrate sensor technology to facilitate precision fertilizer management. Precision Agriculture 2018, 20, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical Approach. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry, Meyers, R.A., McKelvy, M.L., Eds.; Wiley: 2000.

- Traore, M.; Kaal, J.; Martinez Cortizas, A. Differentiation between pine woods according to species and growing location using FTIR-ATR. Wood Sci Technol 2018, 52, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.L.; Lane, M.D.; Dyar, M.D.; King, S.J.; Brown, A.J.; Swayze, G.A. Spectral properties of Ca-sulfates: Gypsum, bassanite, and anhydrite. Am. Mineral. 2014, 99, 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunimatsu, K.; Samant, M.G.; Seki, H. In-situ FT-IR spectroscopic study of bisulfate and sulfate adsorption on platinum electrodes. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry 1989, 258, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing amorphous silica, short-range-ordered silicates and silicic acid species by FTIR. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellerbrock, R.H.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing silicon mineral species of different crystallinity using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Front. Environ. Chem. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launer, P.J.; Arkles, B. Infrared Analysis of Organosilicon Compounds. In Silicon Compounds. In Silicon Compounds: Silanes & Silicones, 3rd ed.; Gelest Inc.: Morrisville, PA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeister, A.M.; Keppel, E.; Speck, A.K. Absorption and reflection infrared spectra of MgO and other diatomic compounds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003, 345, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.R. Application of infrared spectroscopy to studies of silicate glass structure: Examples from the melilite glasses and the systems Na2O-SiO2 and Na2O-Al2O3-SiO2. Journal of Earth System Science 1990, 99, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusentsova, T.N.; Peale, R.E.; Maukonen, D.; Harlow, G.E.; Boesenberg, J.S.; Ebel, D. Far infrared spectroscopy of carbonate minerals. Am. Mineral. 2010, 95, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, A.N. Vibration Spectra and Structures of the Simplest Aromatic Derivatives of Group I–VI Elements. Russian Chemical Reviews 1973, 42, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolo, M.E.; Savini, M.C.; Loewy, R.M. Characterization of soil organic matter by FT-IR spectroscopy and its relationship with chlorpyrifos sorption. J Environ Manage 2017, 196, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Yue, Y.; Qu, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, F.; Liu, H. Properties of Aluminosilicate Glasses Prepared by Red Mud with Various [Al2O3]/[CaO] Mass Ratios. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2018, 33, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, D.; Upterworth, A.L.; Winghart, M.O.; Sebastiani, D.; Nibbering, E.T.J. Azide Anion Interactions with Imidazole and 1-Methylimidazole in Dimethyl Sulfoxide. J Phys Chem B 2025, 129, 8192–8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, T.A.; Malhotra, M.L.; Möller, K.D. Far infrared absorption of lattice modes of solid sodium azide. Materials Research Bulletin 1970, 5, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, R.R.E.; Chapman, S.J.; Jean Robertson, A.H.; Potts, J.M.; Laggoun-Défarge, F.; Gogo, S.; Comont, L.; Disnar, J.-R.; Francez, A.-J. FTIR spectroscopy can be used as a screening tool for organic matter quality in regenerating cutover peatlands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, K.G.; Matsakas, L.; Figueira, J.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P.; Jansson, S. Examination of how variations in lignin properties from Kraft and organosolv extraction influence the physicochemical characteristics of hydrothermal carbon. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2021, 155, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier-Astete, R.; Jimenez-Davalos, J.; Zolla, G. Determination of hemicellulose, cellulose, holocellulose and lignin content using FTIR in Calycophyllum spruceanum (Benth.) K. Schum. and Guazuma crinita Lam. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhen, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, F.; Chen, G.; Zhang, B. Characterization of Dissolved Organic Matter in Deep Geothermal Water from Different Burial Depths Based on Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectra. Water 2017, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, M.M.; Giovanela, M.; Parlanti, E.; Soriano-Sierra, E.J. Fluorescence fingerprint of fulvic and humic acids from varied origins as viewed by single-scan and excitation/emission matrix techniques. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, O.C.; Holt, A.D.; Richards, L.A.; McKenna, A.M.; Spencer, R.G.M.; Lapworth, D.J.; Polya, D.A.; Lloyd, J.R.; van Dongen, B.E. Characterisation of dissolved organic matter in two contrasting arsenic-prone sites in Kandal Province, Cambodia. Org. Geochem. 2024, 198, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wu, X.; Zhi, G.; Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Qadeer, A.; Zheng, J.; Deng, W.; et al. Fluorescence characteristics of DOM and its influence on water quality of rivers and lakes in the Dianchi Lake basin. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tong, Y.; Chang, Q.; Lu, J.; Ma, T.; Zhou, F.; Li, J. Source identification and characteristics of dissolved organic matter and disinfection by-product formation potential using EEM-PARAFAC in the Manas River, China. RSC Adv 2021, 11, 28476–28487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrofanov, V.L. Role of the soil particle-size fractions in the sorption and desorption of potassium. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2012, 45, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, V.M.; Tulina, A.S.; Semenova, N.A.; Ivannikova, L.A. Humification and nonhumification pathways of the organic matter stabilization in soil: A review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2013, 46, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants; CRC Press: 2010.

- Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Chen, Z.; Gu, T.; Wang, W.; Yu, L.; Guo, Y.; et al. Fluorescence Characteristics of Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter in the Eastern Indian Ocean: A Case Study of Three Subregions. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 742595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

| Measuring range, cm–1 | 4000–100 |

| Resolution, cm–1 | 2 |

| Number of background scans | 128 |

| Number of sample scans | 128 |

| Phase resolution | 16 |

| Phase Correction | Mertz |

| Apodization Function | Blackman–Harris, 3-term |

| Zero fill factor | 2 |

| Aperture, mm | 8 |

| Source | mid-IR |

| Beam Splitter | wide mid-IR–far IR (Si) |

| Band name | Ex wavelength range, nm | Em wavelength range, nm | Groups of substances |

| А* | 240–300 | 380–505 | humic-like |

| В* | 250–285 | 280–320 | tyrosine-, protein-like |

| С* | 300–390 | 380–505 | humic-like |

| Т* | 250–285 | 320–400 | tryptophan-, phenol-, protein-like |

| Wavenumber, cm–1 | Inorganic (matrix) constituents | Organic constituents |

| 3695–3690 | unbonded SiO–H stretch, tilted (kaolinite, clay) [113] | — |

| 3625–3620 | hydrogen-bonded SiO–H…H2O stretch (amorphous species) [111,112] | — |

| 3390 | combination band NaN3 ≅ 1350+2043 [100,101] | — |

| 3390 and 3270 | antisymmetric and symmetric hydrogen-bond ensembles | — |

| 2960 | — | antisymmetric stretch of (alkene) methylene groups [104,106,107,108] |

| 2940–2920 and 2855–2850 |

— | antisymmetric and symmetric stretch of methylene groups [104,106,107,108] |

| 2810 | — | (?) C–H stretching adjacent to carbonyls |

| 2770 | — | — |

| 2670 | — | hydrogen-bonded O-H stretching vibrations in carboxylic acids [50] |

| 2380 | ambient CO2 | — |

| 2340 | ambient CO2 | — |

| 2040 | NaN3 | — |

| 1740–1730 | — | Carbonyl, conjugated or esters |

| 1680–1670 | — | Carboxyl, antisymmetric stretch, or Amide I alkene –C=C– stretch, (?) substituted aromatics |

| 1645–1630 | bend (v2) of the covalent bonds of liquid absorbed water [122] and OH groups, O–H stretch | — |

| 1620–1615 | hydrogen-bonded sioh…h2o, ho–h stretch (amorphous) [113] | — |

| 1580 | — | Carboxylate, antisymmetric stretch |

| 1520 | — | Aromatic C=C stretch Amide II band (primarily –N–H bending and C–N stretching) SiO2 combination band [110] |

| 1500 | — | aromatic C=C stretch |

| 1480–1460 | — | Scissoring C–H bend (deformation) antisymmetric bending in –CH3 [123] (?) C=C stretching and ring breathing vibrations in aromatic compounds |

| 1450–1440 | carbonate, antisymmetric stretch [114], dolomite [124] | — |

| 1415–1405 | carbonate, antisymmetric stretch calcite [125], clay or carbonate minerals [109] | — |

| 1390–1380 | — | Carboxylate, symmetric stretch nitrate from nitrogen fertilizers [126] symmetric bend in –CH3 [127] |

| 1310–1300 | — | –C–H bend (deformation) vibrations, including amorphous and crystalline cellulose [128] |

| 1280 | — | Carboxyl, antisymmetric stretch or SiO2 combination band |

| 1120–1100 | and O–Si–O stretch in crystalline/amorphous SiO2 species | — |

| 1090 | Carbonate, symmetric stretch [125] | Cellulose |

| 1070–1050 | SiO2, (kaolinite, illite) O–Si–O lattice antisymmetric stretch [119,131,132] |

— |

| 1035 | quartz lattice O–Si–O stretch | Carbohydrates + PO43 stretching (1100–1000 cm–1) [138] |

| 1010 | Si–O–Si stretch [131,132] | Carbohydrates + PO43 stretching (1100–1000 cm–1) [138] |

| 975 | amorphous silica, Si–OH including biogenic [131,132] | — |

| 930 | Silicate, aluminosilicate, overtone [118] | — |

| 912 | –Si–O– [105]; overtone SiO2 ≅2×450 in aluminosilicates and silicates + Al–OH bending [99] | — |

| 900 | Si–O stretching in silicates | — |

| 890 | Si–O–Si stretch in quartz | — |

| 880–875 | Carbonate, out-of-plane bend [125] | — |

| 865 | Si–O–Si stretching (sheet silicates, some aluminosilicates [131,139] | — |

| 850 | Si–O (quartz/silicate, aluminosilicate) | — |

| 840 | –Si–O– [105] | — |

| 825 | Si–O stretch in feldspars and aluminosilicate [131,139] | — |

| 810–805 | symmetric stretching vibration Si–O–Si, silica, amorphous [102] | — |

| 797 | O–Si–O stretch | C–H bending (non-aromatic) |

| 715 | Carbonate, in-plane bend [125] | — |

| 697 | Si–O–Si bend (including aluminosilicates) [131,139] | C–H aromatic compounds, bending |

| 685 | Si–O–Si (crystalline forms, aluminosilicates) [131] | — |

| 668 | CO2 | — |

| 655 | Al–O–Si in aluminosilicates | — |

| 638 | NaN3 out-of-plane bending [140] | — |

| 525–520 | silicate O–Si–O bend [119], including bending or deformation modes of silicate frameworks or associated alumina environments in complex silicates [135] | — |

| 510 | O–Si–O or Si–O–Si bending in both crystalline and amorphous silica species | — |

| 460–450 | O–Si–O bending of bridging oxygens | — |

| 430 | O–Si–O bending of bridging oxygens Mg–OH, Al–OH (clay minerals) | С–С in-phase vibrations |

| 375 | R(SiO4) [109] | — |

| 347 | SiO2 | — |

| 308 | crystalline matrix (clay or carbonate minerals) [136] | — |

| 296 | lattice vibrations | — |

| 263 | α-quartz [102] | — |

| 225 | lattice vibrational modes in minerals and crystalline materials (involving collective movement of atoms or ions in the crystal lattice) [137] | — |

| 200–190 | crystalline matrix (clay or carbonate minerals) [136] | — |

| 174 | NaN3 lattice [141] | — |

| 130 | crystalline matrix (clay or carbonate minerals) | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).