Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

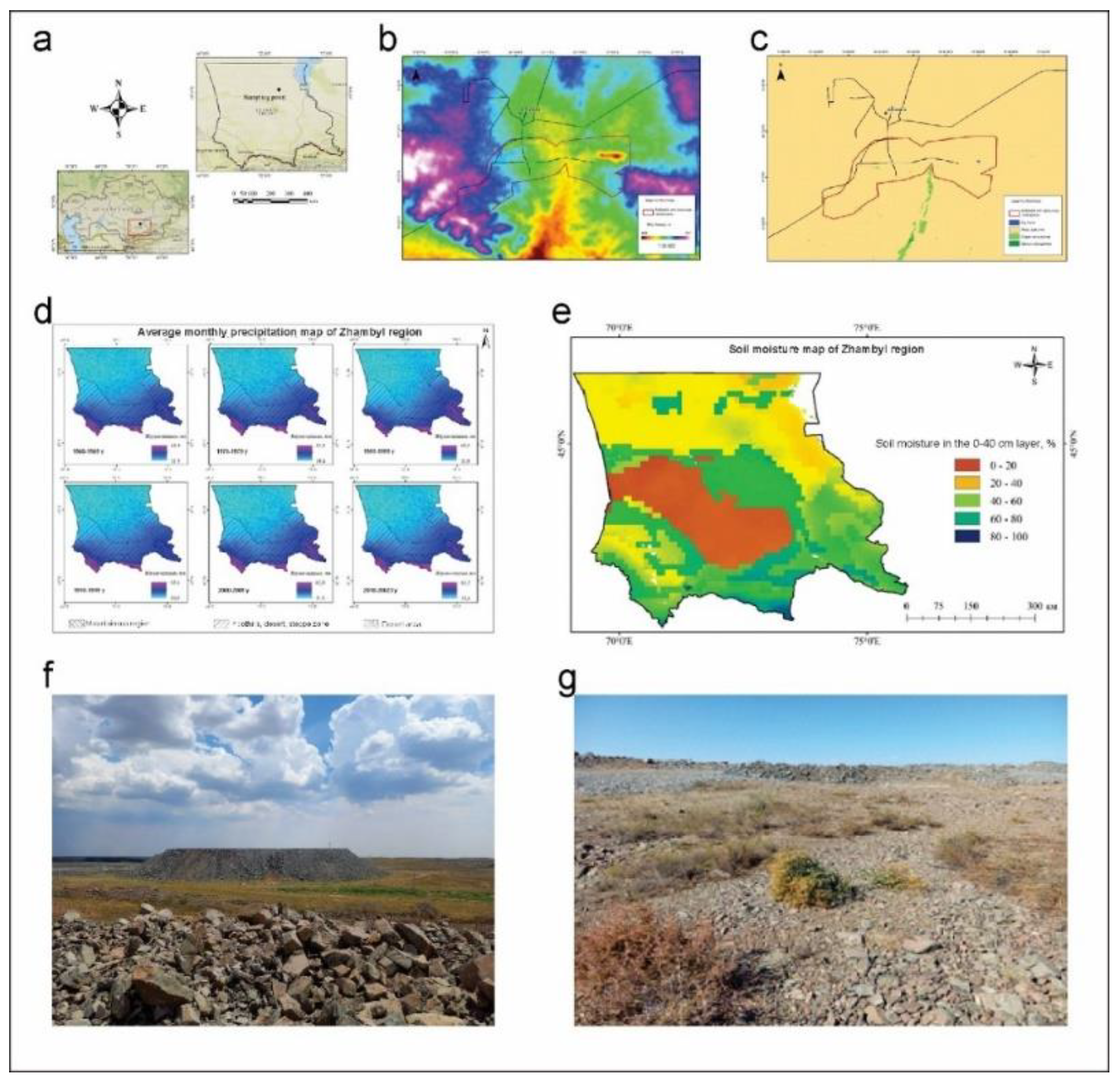

2.1. Study Area

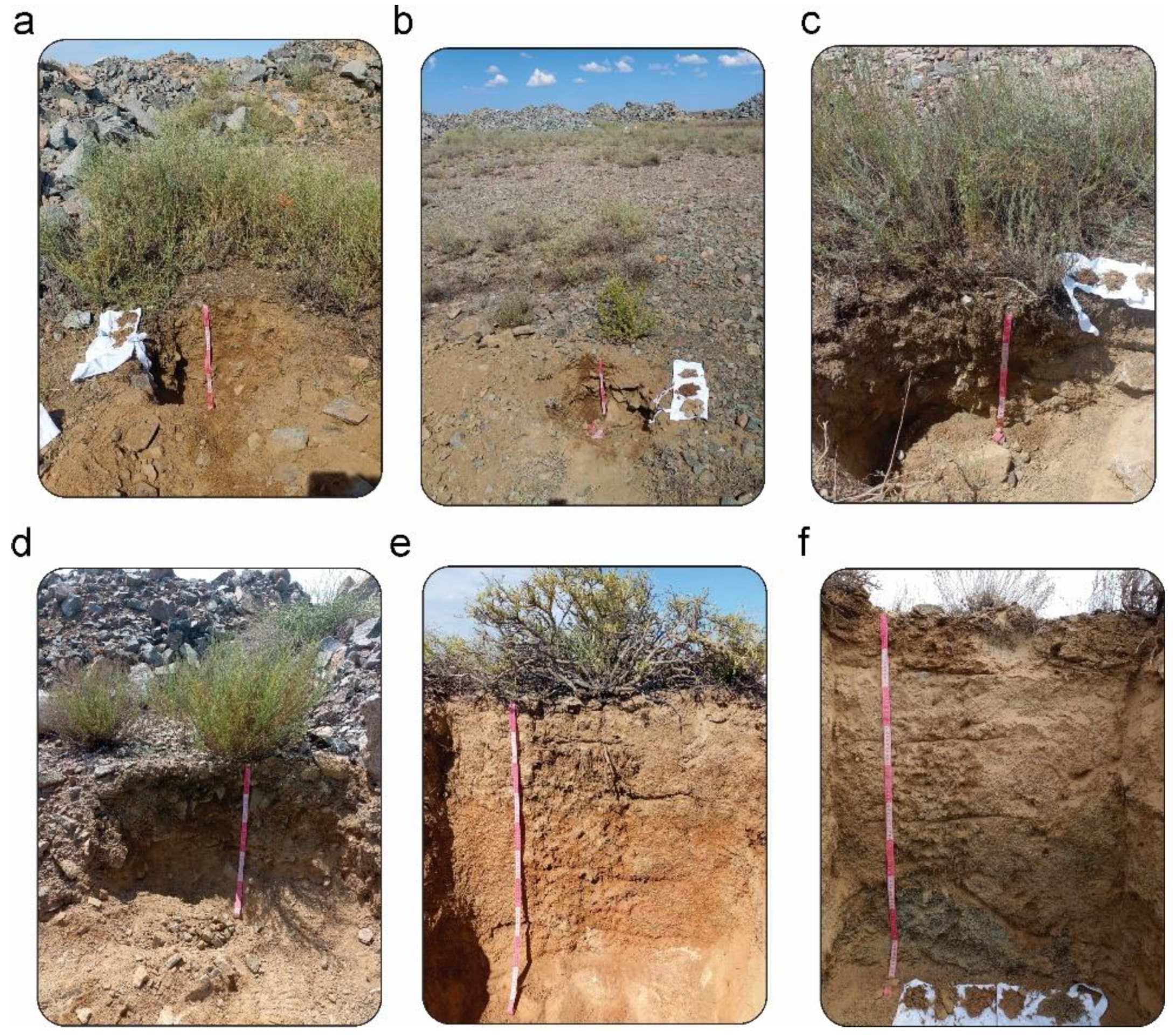

2.2. Soil Sampling and Profile Analysis

2.3. Soil Chemical and Physical Properties

2.4. Heavy Metal Analysis

2.5. Granulometric Composition and Soil Texture

2.6. Soil Formation and Restoration Potential

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Chemical and Agrochemical Properties

3.2. Granulometric Analysis of Aggregated and Aegional Sandy Soils

3.3. Soil Salinization and Chemical Composition Analysis

3.4. Heavy Metal Analysis in Soils

3.5. Heavy Metal Analysis in Natural Soils of the Area Affected by Technogenic Pollution

3.6. Investigation of Heavy Metals in Tailings Soils

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Chemical and Agrochemical Properties

4.2. Granulometric Analysis of Aggregated and Regional Sandy Soils

4.3. Soil Salinization and Chemical Composition Analysis

4.4. Heavy Metal Analysis in Soils Affected by Technogenic Pollution

4.5. Investigation of Heavy Metals in Tailings Soils

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEC | Cation Exchange Capacity |

| Det. Ind. | Determined Indicator |

| Forms of Frac. | Forms of Fractions |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry |

| LOI | Loss on Ignition |

| MPC | Maximum Permissible Concentration |

| SP | Soil Profile |

References

- Alloway, B.J. Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and Their Bioavailability; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.G.; Tang, Z.; McGrath, S.P. Soil contamination and remediation: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Environ. Int. 2014, 66, 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, A.; Mahvi, A.H.; Shahcheraghi, F. Evaluation of heavy metal contamination in soils around mining sites in Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 520. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, R.; Ahmad, N.; Qayyum, A.; Khan, S. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in mining soils: A case study from the Indian subcontinent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 383, 121102. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, A.D. Restoration of mined lands: Where science and art meet. Ecol. Appl. 1997, 7, 944–953. [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran, V.; Shukla, A.; Sharma, R. Assessment of heavy metals in soils of a mining region in India. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 71, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold, J.; Hudson, L.N.; Hill, S.L.L.; et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Smith, L.; Davis, R. Long-term impacts of heavy metal accumulation on soil quality in mining regions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 4567–4575. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q. Long-term impacts of mining on soil quality: Evidence from an abandoned open-pit mine. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 270, 116341. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, H. Heavy metals in agricultural soils: Sources, influencing factors, and remediation strategies. Toxics 2024, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Remediation strategies for heavy metal-contaminated soils in mining areas: Phytoremediation and soil amendments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 369, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- García, P.; Martinez, R.; Lopez, F. Effects of heavy metal contamination on soil microbial diversity in mining-impacted areas. Chemosphere 2016, 150, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J.; Steffen, W. The Anthropocene. Glob. Change Newsl. 2003, 41, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.; Stahr, K. Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology; Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 3: Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.R.; Gregorich, E.G. Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blume, H.-P.; Page, A.L.; Miller, R.H.; Keeney, D.R. Methods of Soil Analysis: Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; 1184 pp. Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenkd. 1985, 148, 363–364. [Google Scholar]

- Rengasamy, P. World salinization with emphasis on Australia. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- US Salinity Laboratory Staff. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Krasilnikov, P.; Martí, J.-J.I.; Arnold, R.; Shoba, S. Soil Classification and Diagnostics of the Former Soviet Union, 1977. In A Handbook of Soil Terminology, Correlation and Classification; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Method 3050B: Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, and Soils; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Senila, M. Recent advances in the determination of major and trace elements in plants using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. Molecules 2024, 29, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, W.L.; Norvell, W.A. Development of a DTPA soil test for zinc, iron, manganese, and copper. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1978, 42, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.C.; Weil, R.R. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 14th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 [Computer software]; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Havlin, J.L.; Tisdale, S.L.; Nelson, W.L.; Beaton, J.D. Soil Fertility and Fertilizers: An Introduction to Nutrient Management, 8th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hillel, D. Environmental Soil Physics: Fundamentals, Applications, and Environmental Considerations; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: A review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. ISRN Ecol. 2011, 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, C.N.; Yong, R.N.; Gibbs, B.F. Remediation technologies for metal-contaminated soils and groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 4551–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sharma, P. Heavy metal pollution in soils. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 157, 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Zhakypbek, Y.; Kossalbayev, B.D.; Belkozhayev, A.M.; Murat, T.; Tursbekov, S.; Abdalimov, E.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kreslavski, V.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Reducing heavy metal contamination in soil and water using phytoremediation. Plants 2024, 13, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Soil sections |

Depth, cm | Humus (O.M.),% |

Total | Mobile | pH | Soil absorbed bases, mg-eq/100 g of soil | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P2O5 | K2O | N | P2O5 | K2O | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | Na+ | K+ | ||||

| % | % | % | Mg/ kg |

Mg/ kg |

Mg/ kg |

||||||||

| SP 1 |

0-2 | 1,82 | 0,168 | 0,276 | 2,875 | 98 | 122 | 220 | 8,06 | 10,89 | 1,49 | 0,31 | 0,15 |

| 2-11 | 0,45 | 0,112 | 0,192 | 2,75 | 25,2 | 23 | 160 | 8,2 | 12,38 | 7,43 | 0,31 | 0,19 | |

| 11-25 | 0,41 | 0,056 | 0,16 | 2,437 | 19,6 | 13 | 90 | 8,26 | 12,38 | 7,92 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| 25-35 | 0,45 | 0,042 | 0,128 | 2,187 | 14 | 5 | 50 | 8,2 | 12,87 | 7,43 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| SP 2 | 0-0,3 | 1,07 | 0,056 | 0,384 | 3,187 | 33,6 | 81 | 140 | 8,53 | 8,91 | 0,99 | 0,31 | 0,25 |

| 0,3-14 | 0,27 | 0,056 | 0,36 | 3 | 14 | 61 | 90 | 8,49 | 27,23 | 2,48 | 0,31 | 0,25 | |

| SP 3 | 0-1 | 1,03 | 0,098 | 0,328 | 3,125 | 145,6 | 100 | 170 | 8,72 | 4,95 | 2,48 | 0,31 | 0,21 |

| 1-12 | 0,55 | 0,126 | 0,296 | 3 | 58,8 | 78 | 90 | 8,57 | 12,38 | 5,94 | 0,29 | 0,25 | |

| 12-25 | 0,58 | 0,07 | 0,296 | 2,75 | 33,6 | 48 | 90 | 8,26 | 12,87 | 7,43 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| 25-43 | 0,38 | 0,056 | 0,208 | 2,25 | 19,6 | 31 | 70 | 8,22 | 9,9 | 9,9 | 0,27 | 0,26 | |

| SP 4 | 0-1 | 1,86 | 0,126 | 0,276 | 3 | 75,6 | 100 | 220 | 8,02 | 7,43 | 2,48 | 0,31 | 0,17 |

| 1-11 | 0,41 | 0,112 | 0,232 | 3,187 | 19,6 | 28 | 120 | 8,47 | 4,95 | 2,48 | 0,31 | 0,25 | |

| 11-22 | 0,17 | 0,042 | 0,192 | 2,312 | 19,6 | 8 | 50 | 8,98 | 11,88 | 9,9 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| 22-42 | 0,1 | 0,042 | 0,192 | 2,187 | 8,4 | 8 | 50 | 8,37 | 12,87 | 7,43 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| SP 5 | 0-4 | 1,07 | 0,14 | 0,16 | 2,187 | 36,4 | 48 | 220 | 8,77 | 4,95 | 2,48 | 0,27 | 0,22 |

| 4-13 | 0,41 | 0,07 | 0,148 | 1,875 | 36,4 | 20 | 230 | 9,12 | 3,47 | 1,49 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| 13-28 | 0,48 | 0,056 | 0,128 | 2,187 | 19,6 | 5 | 150 | 8,91 | 8,42 | 8,91 | 0,24 | 0,26 | |

| 28-56 | 0,58 | 0,042 | 0,072 | 3 | 14 | 5 | 80 | 9,07 | 9,9 | 3,47 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| 56-78 | 0,21 | 0,07 | 0,072 | 2,437 | 8,4 | 5 | 50 | 9,09 | 12,38 | 2,48 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| 78-95 | 0,17 | 0,014 | 0,136 | 3,75 | 5,6 | 3 | 30 | 8,38 | 27,23 | 2,48 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| SP 6 |

0-13 | 0,31 | 0,056 | 0,136 | 1,625 | 22,4 | 31 | 140 | 8,99 | 4,95 | 3,47 | 0,31 | 0,26 |

| 13-25 | 0,45 | 0,07 | 0,136 | 1,812 | 25,2 | 13 | 110 | 9,03 | 2,48 | 2,48 | 0,31 | 0,26 | |

| 35-57 | 0,62 | 0,07 | 0,148 | 1,5 | 22,4 | 8 | 70 | 8,48 | 12,38 | 2,48 | 0,22 | 0,26 | |

| 57-72 | 0,65 | 0,056 | 0,16 | 1,375 | 22,4 | 10 | 50 | 8,67 | 7,43 | 5,45 | 0,05 | 0,26 | |

| 72-100 | 0,52 | 0,014 | 0,168 | 0,625 | 19,6 | 5 | 50 | 8,54 | 9,9 | 5,94 | 0,28 | 0,26 | |

| Soil sections | Depth, cm | Fraction content in % on absolute dry soil, fraction size in mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | Silt |

Clay | 3-x | |||||

| 1,0-0,25 | 0,25-0,05 | 0,05-0,01 | 0,01-0,005 | 0,005-0,001 | <0,001 | Factions <0,01 | ||

| SP 1 | 0-2 | 8,523 | 72,537 | 9,672 | 4,030 | 3,627 | 1,612 | 9,269 |

| 2-11 | 2,311 | 76,602 | 16,626 | 1,217 | 2,028 | 1,217 | 4,461 | |

| 11-25 | 10,913 | 63,935 | 19,878 | 2,028 | 1,623 | 1,623 | 5,274 | |

| 25-35 | 8,756 | 63,226 | 5,356 | 15,245 | 4,944 | 2,472 | 22,662 | |

| SP 2 | 0-0,3 | 12,321 | 71,170 | 4,429 | 6,443 | 0,805 | 4,832 | 12,080 |

| 0,3-14 | 5,926 | 72,304 | 14,513 | 1,613 | 2,016 | 3,628 | 7,257 | |

| SP 3 | 0-1 | 7,654 | 70,307 | 11,621 | 2,805 | 5,610 | 2,004 | 10,419 |

| 1-12 | 12,027 | 78,367 | 2,401 | 0,400 | 3,602 | 3,202 | 7,204 | |

| 12-25 | 10,040 | 74,729 | 5,611 | 0,802 | 2,806 | 6,012 | 9,619 | |

| 25-43 | 5,238 | 78,863 | 7,746 | 2,854 | 0,815 | 4,484 | 8,153 | |

| SP 4 | 0-1 | 2,022 | 79,183 | 8,989 | 2,860 | 2,860 | 4,086 | 9,806 |

| 1-11 | 10,995 | 77,717 | 2,508 | 0,836 | 7,107 | 0,836 | 8,779 | |

| 11-22 | 9,925 | 79,181 | 6,859 | 1,614 | 0,807 | 1,614 | 4,035 | |

| 22-42 | 4,842 | 84,218 | 2,431 | 0,405 | 4,862 | 3,241 | 8,509 | |

| SP 5 | 0-4 | 10,446 | 51,788 | 17,678 | 12,455 | 4,419 | 3,214 | 20,088 |

| 4-13 | 5,929 | 74,439 | 4,808 | 2,804 | 4,006 | 8,013 | 14,824 | |

| 13-28 | 10,557 | 45,504 | 7,730 | 19,121 | 2,441 | 14,646 | 36,208 | |

| 28-56 | 14,396 | 56,407 | 7,705 | 2,028 | 4,461 | 15,004 | 21,492 | |

| 56-78 | 10,047 | 70,914 | 4,051 | 1,215 | 2,431 | 11,343 | 14,989 | |

| 78-95 | 13,603 | 68,988 | 6,073 | 0,405 | 0,405 | 10,526 | 11,336 | |

| SP 6 |

0-13 | 15,493 | 55,457 | 8,876 | 5,649 | 4,035 | 10,490 | 20,173 |

| 13-25 | 8,819 | 73,102 | 7,232 | 2,411 | 0,402 | 8,035 | 10,848 | |

| 35-57 | 18,792 | 46,341 | 11,758 | 10,136 | 2,433 | 10,541 | 23,110 | |

| 57-72 | 17,348 | 60,918 | 7,245 | 2,012 | 3,622 | 8,855 | 14,490 | |

| 72-100 | 15,313 | 69,293 | 5,266 | 1,620 | 2,836 | 5,671 | 10,128 | |

| Soil sections | Depth, cm | Total salts, % | Alkalinity, total in HCO₃⁻, % | Total in HCO₃⁻, meq | CO32-, % | CO₃2⁻, meq | Cl-, % | Cl⁻, meq | SO4 2-, % | SO₄2⁻, meq | Ca2+, % | Ca2⁺, meq | Mg2+,% | Mg2⁺, meq | Na+, % | Na+, mg/eq | K+, % | K⁺, meq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP 1 | 0-2 | 0,181 | 0,029 | 0,48 | 0 | 0 | 0,004 | 0,11 | 0,098 | 2,04 | 0,028 | 1,39 | 0,011 | 0,93 | 0,002 | 0,1 | 0,009 | 0,22 |

| 2-11 | 0,851 | 0,017 | 0,28 | 0 | 0 | 0,004 | 0,11 | 0,581 | 12,09 | 0,235 | 11,75 | 0,006 | 0,46 | 0,002 | 0,1 | 0,007 | 0,18 | |

| 11-25 | 0,882 | 0,015 | 0,24 | 0 | 0 | 0,004 | 0,11 | 0,606 | 12,62 | 0,25 | 12,49 | 0,005 | 0,37 | 0,002 | 0,08 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 25-35 | 0,9 | 0,012 | 0,2 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,626 | 13,05 | 0,241 | 12,04 | 0,014 | 1,16 | 0,002 | 0,1 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| SP 2 | 0-0,3 | 0,301 | 0,017 | 0,28 | 0 | 0 | 0,004 | 0,11 | 0,195 | 4,07 | 0,068 | 3,42 | 0,01 | 0,84 | 0,003 | 0,11 | 0,003 | 0,09 |

| 0,3-14 | 0,809 | 0,012 | 0,2 | 0 | 0 | 0,004 | 0,11 | 0,565 | 11,77 | 0,194 | 9,72 | 0,025 | 2,08 | 0,004 | 0,19 | 0,003 | 0,09 | |

| SP 3 | 0-1 | 0,105 | 0,032 | 0,52 | 0 | 0 | 0,004 | 0,11 | 0,043 | 0,9 | 0,009 | 0,46 | 0,01 | 0,84 | 0,002 | 0,1 | 0,005 | 0,13 |

| 1-12 | 0,376 | 0,015 | 0,24 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,252 | 5,26 | 0,088 | 4,4 | 0,011 | 0,92 | 0,004 | 0,17 | 0,003 | 0,08 | |

| 12-25 | 0,797 | 0,015 | 0,24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,555 | 11,57 | 0,204 | 10,19 | 0,017 | 1,39 | 0,004 | 0,17 | 0,003 | 0,07 | |

| 25-43 | 0,887 | 0,017 | 0,28 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,617 | 12,85 | 0,222 | 11,11 | 0,022 | 1,85 | 0,005 | 0,21 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| SP 4 | 0-1 | 0,134 | 0,029 | 0,48 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,067 | 1,39 | 0,017 | 0,83 | 0,01 | 0,84 | 0,002 | 0,1 | 0,007 | 0,18 |

| 1-11 | 0,083 | 0,017 | 0,28 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,041 | 0,86 | 0,009 | 0,46 | 0,007 | 0,56 | 0,003 | 0,11 | 0,003 | 0,08 | |

| 11-22 | 0,83 | 0,012 | 0,2 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,574 | 11,97 | 0,227 | 11,34 | 0,008 | 0,69 | 0,004 | 0,17 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 22-42 | 0,86 | 0,012 | 0,2 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,605 | 12,6 | 0,208 | 10,42 | 0,028 | 2,31 | 0,003 | 0,11 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| SP 5 | 0-4 | 0,084 | 0,027 | 0,44 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,033 | 0,69 | 0,006 | 0,28 | 0,008 | 0,65 | 0,004 | 0,17 | 0,004 | 0,11 |

| 4-13 | 0,11 | 0,024 | 0,4 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,055 | 1,14 | 0,007 | 0,37 | 0,011 | 0,93 | 0,005 | 0,21 | 0,004 | 0,11 | |

| 13-28 | 0,087 | 0,029 | 0,48 | 0,01 | 0,2 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,034 | 0,71 | 0,006 | 0,28 | 0,008 | 0,65 | 0,007 | 0,3 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 28-56 | 0,077 | 0,02 | 0,32 | 0 | 0 | 0,001 | 0,04 | 0,037 | 0,77 | 0,006 | 0,28 | 0,008 | 0,65 | 0,004 | 0,17 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 56-78 | 0,105 | 0,015 | 0,24 | 0 | 0 | 0,001 | 0,04 | 0,064 | 1,34 | 0,007 | 0,37 | 0,014 | 1,12 | 0,002 | 0,1 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 78-95 | 0,334 | 0,01 | 0,16 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,234 | 4,88 | 0,059 | 2,96 | 0,025 | 2,04 | 0,002 | 0,08 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| SP 6 | 0-13 | 0,091 | 0,02 | 0,32 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,046 | 0,96 | 0,009 | 0,46 | 0,008 | 0,65 | 0,005 | 0,21 | 0,001 | 0,03 |

| 13-35 | 0,061 | 0,02 | 0,32 | 0 | 0 | 0,003 | 0,07 | 0,023 | 0,48 | 0,007 | 0,37 | 0,003 | 0,28 | 0,004 | 0,19 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 35-57 | 0,216 | 0,015 | 0,24 | 0 | 0 | 0,001 | 0,04 | 0,148 | 3,08 | 0,019 | 0,93 | 0,026 | 2,14 | 0,006 | 0,26 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 57-72 | 0,203 | 0,015 | 0,24 | 0 | 0 | 0,013 | 0,36 | 0,121 | 2,53 | 0,022 | 1,11 | 0,017 | 1,39 | 0,014 | 0,59 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| 72-100 | 1,059 | 0,007 | 0,12 | 0 | 0 | 0,019 | 0,55 | 0,723 | 15,05 | 0,218 | 10,88 | 0,022 | 1,85 | 0,068 | 2,96 | 0,001 | 0,03 |

| Det. Ind. | Forms of Frac. |

Results, mg/kg | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP 1 | SP 2 | SP 3 | SP 4 | SP 5 | SP 6 | ||||||||

| 0-11 cm | 11-25 cm | 0-3 cm | 3-14 cm | 0-1 cm | 1-12 cm | 0-1 cm | 1-11 cm | 0-13 cm | 13-28 cm | 0-13 cm | 13-35 cm | ||

| Cu | Total | 48,13 | 46,66 | 47,38 | 47,91 | 38,21 | 49,62 | 23,58 | 50,12 | 12,36 | 52,37 | 15,97 | 3,163 |

| Mobile | 8,879 | 4,221 | 8,773 | 3,976 | 8,123 | 3,834 | 7,838 | 3,319 | 1,346 | 0,395 | 0,703 | 0,606 | |

| Zn | Total | 96,81 | 85,17 | 94,58 | 83,72 | 91,35 | 82,74 | 89,35 | 79,58 | 96,9 | 73,4 | 64,49 | 49,37 |

| Mobile | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | 5,127 | <0,5 | <0,5 | |

| Cd | Total | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 |

| Mobile | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | |

| Pb | Total | 308 | 284 | 298 | 256 | 223 | 197 | 194 | 176 | 15,26 | 13,89 | 10,61 | 11,79 |

| Mobile | 80,35 | 41,15 | 79,58 | 39,95 | 72,16 | 37,02 | 70,34 | 35,23 | 2,356 | <0,5 | 0,887 | 0,824 | |

| Co | Total | 18,31 | 19,79 | 17,98 | 18,11 | 15,78 | 16,92 | 13,89 | 13,22 | 7,21 | 10,39 | 8,65 | 8,399 |

| Mobile | 5,223 | 2,068 | 4,989 | 2,001 | 4,867 | 1,976 | 2,567 | 1,345 | 0,685 | 1,058 | 0,907 | 0,501 | |

| Ni | Total | 28,46 | 30,95 | 26,32 | 29,72 | 23,32 | 29,13 | 21,62 | 28,83 | 19,6 | 28,76 | 21,64 | 20,19 |

| Mobile | 4,153 | 2,262 | 3,996 | 2,146 | 3,772 | 1,954 | 2,458 | 1,912 | 1,541 | 1,851 | 1,398 | 0,812 | |

| Mo | Total | 18,12 | 16,99 | 17,86 | 15,34 | 9,43 | 5,34 | <1,0 | 1,32 | <1,0 | 1,32 | 1,03 | <1,0 |

| Mobile | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | |

| Ag | Total | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 |

| Mobile | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | |

| As | Total | 5,96 | 3,66 | 5,74 | 3,12 | 4,86 | 2,87 | 3,77 | 2,13 | 0,380 | 1,58 | 0,652 | <0,05 |

| Mobile | 0,291 | 0,064 | 0,243 | 0,061 | 0,196 | 0,058 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | |

| Measured indicator | Forms of fractions | Results, mg/kg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point 1 | Point 2 | ||||

| 0-20 cm | 20-40 cm | 0-20 cm | 20-40 cm | ||

| Cu | Total | 3,542 | 1,748 | 12,672 | 22,83 |

| Mobile | 1,731 | 0,974 | 1,274 | 2,730 | |

| Zn | Total | 46,33 | 44,72 | 50,422 | 73,77 |

| Mobile | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | |

| Cd | Total | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 |

| Mobile | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | |

| Pb | Total | 10,31 | 8,618 | 11,34 | 14,96 |

| Mobile | 2,163 | 1,672 | 1,169 | 2,146 | |

| Co | Total | 7,542 | 7,422 | 7,987 | 9,704 |

| Mobile | 0,909 | 0,792 | 0,544 | 0,978 | |

| Ni | Total | 20,71 | 20,48 | 21,27 | 25,15 |

| Mobile | 2,451 | 1,534 | 0,748 | 1,511 | |

| Mo | Total | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 |

| Mobile | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | |

| Ag | Total | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 |

| Mobile | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | |

| As | Total | <0,05 | <0,05 | 0,291 | <0,05 |

| Mobile | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | |

| Det. Ind. | Forms of Frac. |

Results, mg/kg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tailings (Gray) Layer I | Tailings (Red) Layer I | Tailings (Black) Layer II | |||||

| 0-20 cm | 20-40 cm | 0-20 cm | 20-40 cm | 0-20 cm | 20-40 cm | ||

| Cu | Total | 138,11 | 70,28 | 85,33 | 41,74 | 33,79 | 18,92 |

| Mobile | 3,748 | 4,694 | 5,275 | 6,885 | 5,028 | 3,941 | |

| Zn | Total | 127,94 | 112,89 | 167,1 | 114,2 | 133,7 | 2,216 |

| Mobile | <0,5 | <0,5 | 3,254 | <0,5 | 11,13 | <0,5 | |

| Cd | Total | 0,128 | 0,098 | 0,130 | 0,129 | 0,171 | <0,05 |

| Mobile | 0,068 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | <0,05 | |

| Pb | Total | 51,79 | 56,94 | 72,595 | 35,79 | 56,48 | 13,68 |

| Mobile | 20,36 | 20,20 | 21,12 | 16,24 | 21,33 | 5,559 | |

| Co | Total | 18,9 | 15,56 | 22,38 | 12,48 | 16,47 | 9,413 |

| Mobile | 6,534 | 5,015 | 5,969 | 5,413 | 6,992 | 4,708 | |

| Ni | Total | 50,59 | 46,9 | 56,81 | 38,73 | 44,40 | 21,14 |

| Mobile | 8,645 | 8,449 | 8,756 | 9,902 | 10,08 | 5,882 | |

| Mo | Total | 3,65 | 2,05 | 2,387 | 1,685 | 2,01 | <1,0 |

| Mobile | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | <1,0 | |

| Ag | Total | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 |

| Mobile | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | <0,5 | |

| As | Total | 17,60 | 20,71 | 19,15 | 19,71 | 15,77 | 4,05 |

| Mobile | 2,76 | 4,22 | 3,68 | 5,83 | 3,60 | 1,19 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).