Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

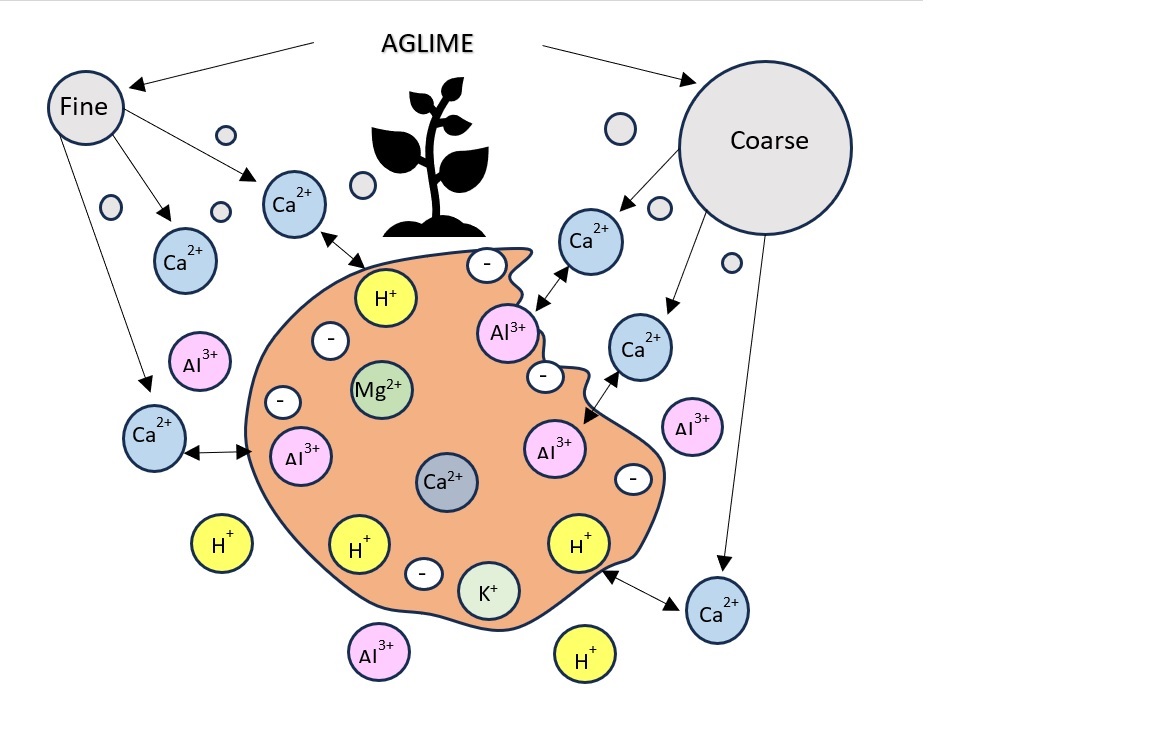

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental site

2.2. Soil Sampling

2.2.2. Exchangeable Ca (Caexch), Mg (Mgexch), and K (Kexch) Determination

2.2.3. Exchangeable Al (Alexch) Determination

3. Results

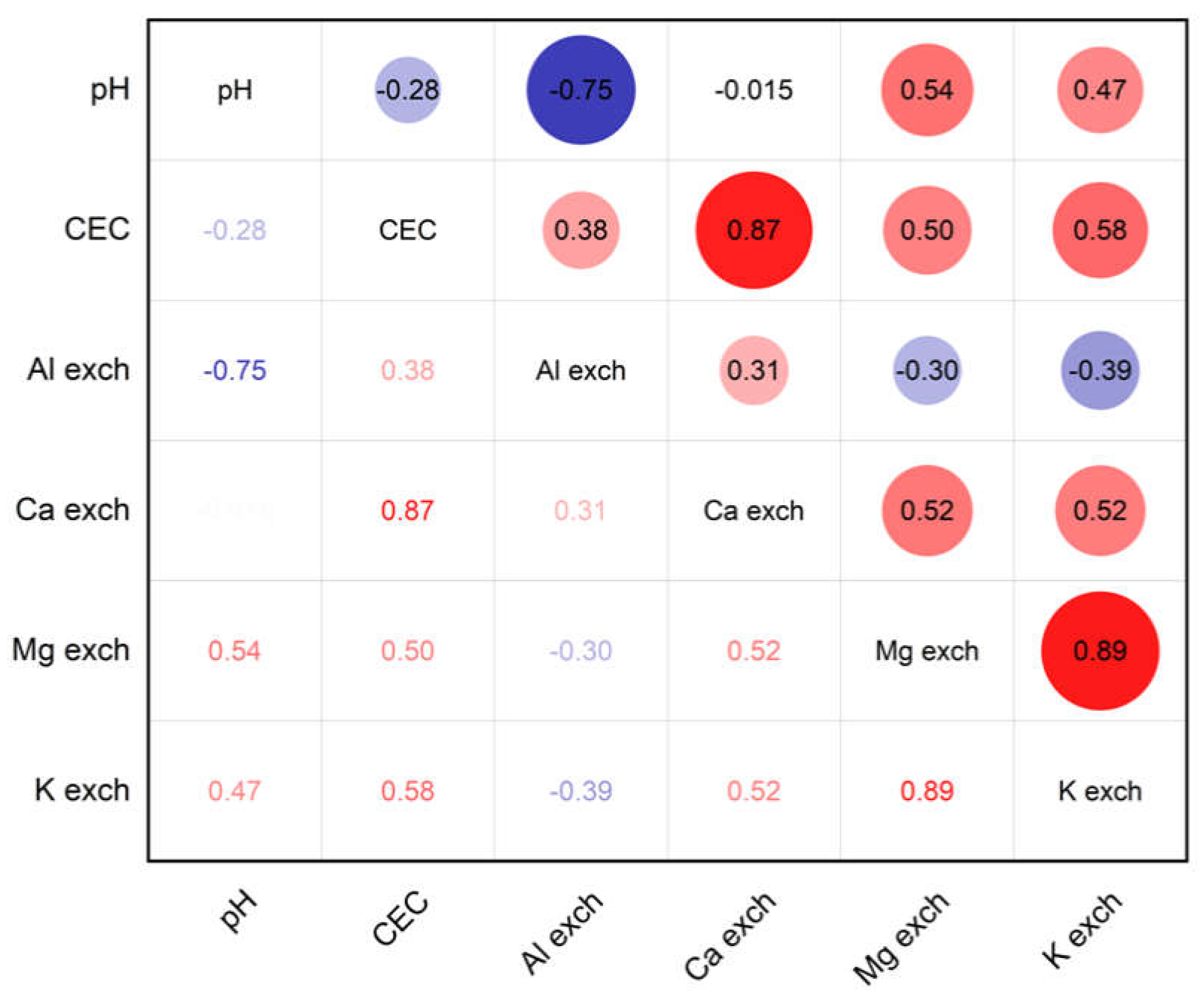

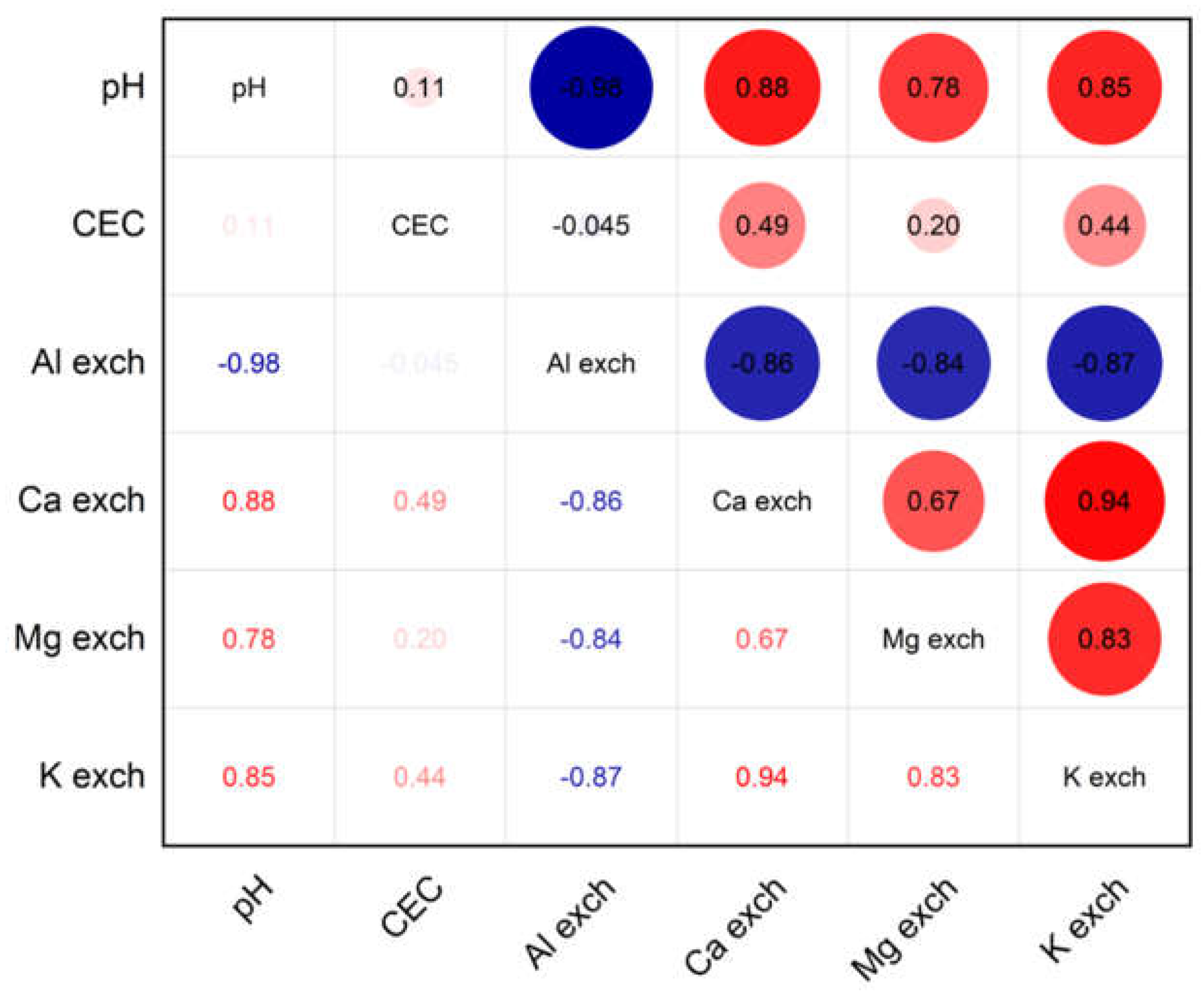

3.1. Modification in Soil pH Values

3.2. CEC Values After Lime Application

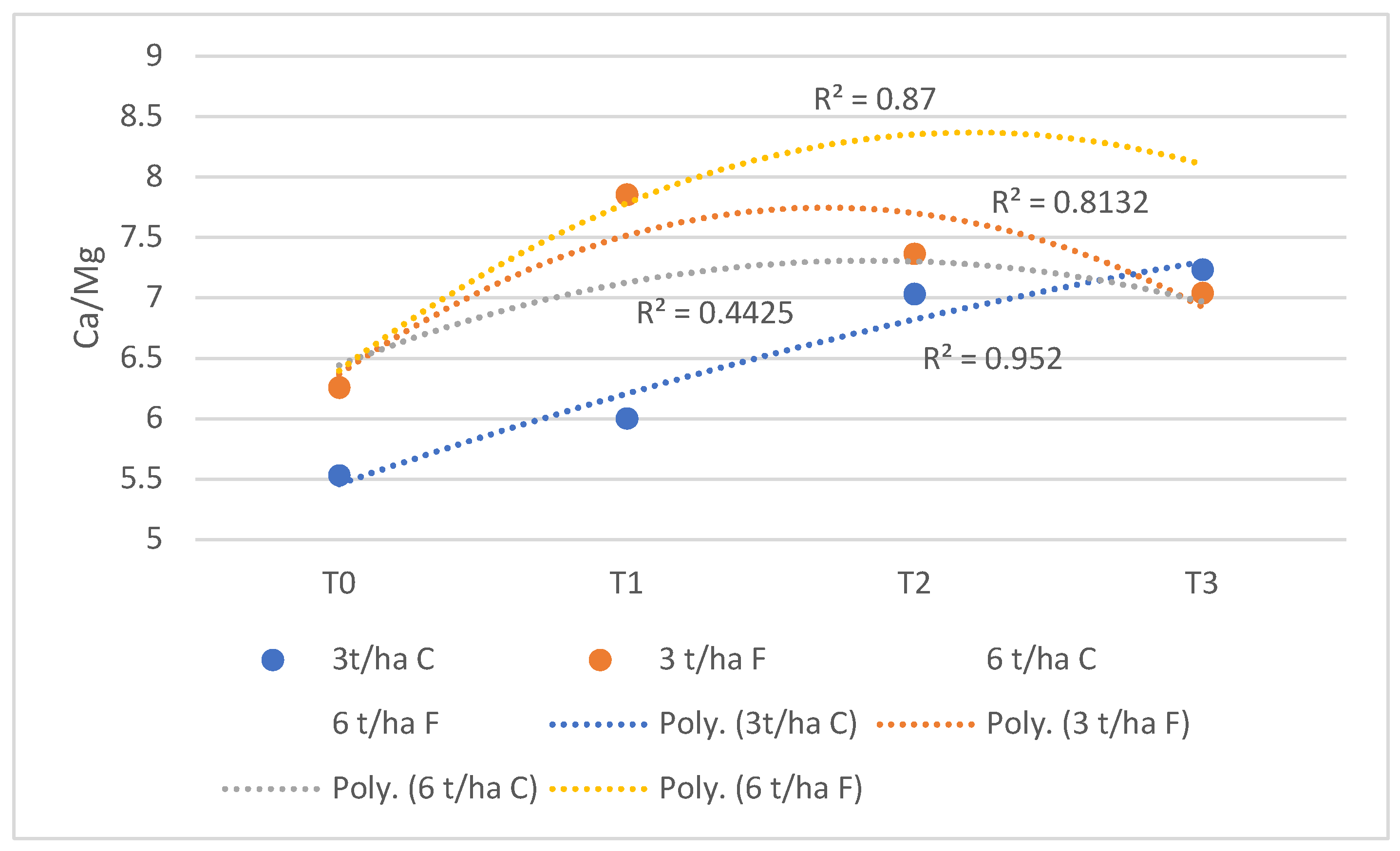

3.3. Modification of Exchangeable Ca, Mg and K Values

3.4. Exchangeable Aluminium

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aglime | Agricultural lime (CaCO3) |

| Kg a.s./ha | Kg active substance/ha |

References

- Ji, F.N.; Osumanu, H.A.; Mohamadu, B.J.; Latifah, O.; Yee, M.K.; Adiza, A.M.; Ken, H.P. Soil nutrient retention and pH buffering capacity are enhanced by calciprill and sodium silicate. Agronomy 2022, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Slessarev, E.; Lin, Y.; Bingham, N.J.; Johnson, E.; Dai, Y.; Schimel, J.P. Water balance creates a threshold in soil pH at the global scale. Nature 2016, 540, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasinghe, I.U.; Saito, T.; Takemura, T.; Kawamoto, K.; Komatsu, T.; Watanabe, N.; Kawabe, Y. Applicability of alkaline waste and by-products as low cost alternative neutralizers for acidic soils. ISIJ Int. 2022, 63, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D. L.; Singh, B.; Siebecker, M.G. Environmental soil chemistry, 3rd edition. Publisher: Academic Press, 2023, pp. 351–360.

- Holland, J.E.; White, P.J.; Glendining, M.J.; Goulding, K.W.T.; McGrath, S.P. Yield responses of arable crops to liming–An evaluation of relationships between yields and soil pH from a long-term liming experiment. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 105, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neina, D. The role of soil pH in plant nutrition and soil remediation. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Corbett, D.; Wall, D.P.; Lynch, M.B.; Tuohy, P. The influence of lime application on the chemical and physical characteristics of acidic grassland soils with impeded drainage. The Journal of Agricultural Science. 2021, 159, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashuan, T.; Shuli, N. A global analysis of soil acidification caused by nitrogen addition. Environ. Res. Lett. 1088. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, A.; Dinu, T. A.; Stoian, E.; Şerban, V. The use of chemical fertilizers in Romania's agriculture. Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 2021, 21.

- Vicar, N.; Lațo, A.; Lațo, I.; Crista, F.; Berbecea, A.; Radulov, I. Effect of Urease and Nitrification Inhibitors on Heavy Metal Mobility in an Intensively Cultivated Soil. Agronomy 2025, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskulska, I.; Jaskulski, D.; Kobierski, M. Effect of liming on the change of some agrochemical soil properties in a long-term fertilization experiment. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, S.; Chang, S.X.; Zhang, Q. Liming effects on soil pH and crop yield depend on lime material type, application method and rate, and crop species: A global meta-analysis. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, K.W.T. Soil acidification and the importance of liming agricultural soils with particular reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manag. 2016, 32, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.T.; Koenig, R.T.; Huggins, D.R.; Harsh, J.B.; Rossi, R.E. Lime effects on soil acidity, crop yield, and aluminum chemistry in direct-seeded cropping systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2008, 72, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daba, N.A.; Li, D.; Huang, J.; Han, T.; Zhang, L.; Ali, S.; Khan, M.N.; Du, J.; Liu, S.; Legesse, T.G. Long-term fertilization and lime-induced soil pH changes affect nitrogen use efficiency and grain yields in acidic soil under wheat-maize rota-tion. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Keitel, C.; Dijkstra, F.A. Ameliorating soil acidity with calcium carbonate and calcium hydroxide: effects on carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus dynamics. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 2023, 23, 5270–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajicova, K.; Chuman, T. Effect of land use on soil chemical properties after 190 years of forest to agricultural land conversion. Soil and Water Research 2019, 14, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, W.H.; Lalande, H.; Duquette, M. Soil reaction and exchangeable acidity. In Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis, 2nd ed., 2007; pp. 173–178.

- Shaimaa, H.A.E.; Mostafa, M.A.M.; Taha, T.A.; Elsharawy, M.A.O.; Eid, M.A. Effect of different amendments on soil chemical characteristics, grain yield and elemental content of wheat plants grown on salt-affected soil irrigated with low quality water. Annals of Agricultural Science 2012, 57, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Standard operating procedure for soil pH determination, Rome, 2021.

- Kibet, P.K.; Mugwe, J.N.; Korir, N.K.; Mucheru-Muna, M.W.; Ngetich, F.K. Granular and powdered lime improves soil properties and maize (Zea mays l.) performance in humic Nitisols of central highlands in Kenya. Heliyon. [CrossRef]

- Sikiric, B.; Stajkovic-Srbinovic, O.; Cakmak, D.; Delic, D.; Kokovic, N.; Kostic-Kravljanac, Lj.; Mrvic, V. Macronutrient contents in the leaves and fruits of red raspberry as affected by liming in an extremely acid soil. Plant Soil Environ. 2015, 61, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, U.; Rosengren, U.; Bengt, N.; Thelin, G. A comparative study of two methods for determination of pH, exchangeable base cations, and aluminum. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2002, 33, 3809–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.S.; Ketterings, Q. Recommended methods for determining, soil cation exchange capacity. In Recommended Soil Testing Procedures for the Northeastern United States, Last Revised 5/2011.

- Jones, J.D.; Mallarino, A.P. Influence of source and particle size on agricultural limestone efficiency at increasing soil pH. In North Central Extension-Industry Soil Fertility Conference, Des Moines, IA, 2016.

- Enesi, R.O.; Dyck, M.; Chang, S.; Thilakarathna, M.S.; Fan, X.; Strelkov, S.; Gorim, L.Y. Liming remediates soil acidity and improves crop yield and profitability - a meta-analysis. Front. Front. Agron. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, Y.M.; Gazey, C.; Fisher, J.; Robertson, M. Dissection of the contributing factors to the variable response of crop yield to surface applied lime in Australia. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutivén, J.C.B.; Suarez, H.O.E.; Montúfar, G.H.V. Buffer capacity as a method to estimate the dose of liming in acid. Agro Productividad 2022. [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Haliski, A.; Bini, A.R.; Scharr, D.A. Surface liming and nitrogen fertilization for crop grain production under no-till management in Brazil. European Journal of Agronomy 2015, 66, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibet, P.K.; Mugwe, J.N.; Korir, N.K.; Mucheru-Muna, M.W.; Ngetich, F.K.; Mugendi, D.N. Granular and powdered lime improves soil properties and maize (Zea mays l.) performance in humic Nitisols of central highlands in Kenya. Heliyon. [CrossRef]

- Scott, B. J.; Conyers, M. K.; Fisher, R.; Lill, W. Particle size determines the efficiency of calcitic limestone in amending acidic soil. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1992, 43, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Toit, D. J. J.; Swanepoel, P. A.; Hardie, A. G. Effect of Lime Source, Fineness and Granulation on Soil Permeation with Contrasting Textures under Simulated Mediterranean Climate Rainfall Conditions. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2024, 55, 3011–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, J. L.; Moot, D. J. Soil pH, exchangeable aluminium and lucerne yield responses to lime in a South Island high country soil. Proceedings of the New Zealand Grassland Association 2010, 72, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianos, Gh.; Pusca, I.; Goian, M. Banat Soils – part II – Natural conditions and fertility; Publisher: Mirton 1997, Timisoara, Romania, pp. 118–130.

- Brady, N.C. , Weil R.R. The nature and properties of soils, 14th ed.; Publisher: Pearson Education Inc, 2008; pp. 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Tang, C.; Baldock, J.A.; Butterly, C.R.; Gazey, C. Long-term effect of lime application on the chemical composition of soil organic carbon in acid soils varying in texture and liming history. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2016, 52, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, K.W.T. Soil acidification and the importance of liming agricultural soils with particular reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manag. 2016, 32, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskulska, I.; Jaskulski, D.; Kobierski, M. Effect of liming on the change of some agrochemical soil properties in a long-term fertilization experiment. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olego, M.Á.; Quiroga, M.J.; Mendaña-Cuervo, C.; Cara-Jiménez, J.; López, R.; Garzón-Jimeno, E. Long-term effects of calci-um-based liming materials on soil fertility sustainability and rye production as soil quality indicators on a Typic Palexerult. Processes 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workineh, E.; Yihenew, G. S.; Eyasu, E.; Eyayu, M. Effect of lime rates and method of application on soil properties of acidic Luvisols and wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) yields in northwest Ethiopia. Heliyon. [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M.; Pavan, M.A.; Ziglio, C.O.; Franchini, J.C. Reduction of Exchangeable Calcium and Magnesium in Soil with Increasing pH. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 2001, 44, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Upadhyaya, H. Aluminium Toxicity and Its Tolerance in Plant: A Review. J. Plant Biol. 2021, 64, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyaneza, V.; Zhang, W.; Haider, S. Strategies for alleviating aluminum toxicity in soils and plants. Plant Soil 2024, 504, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, A.E.; Moir, J.L.; Almond, P.C.; Moot, D.J. Soil pH and exchangeable aluminium in contrasting New Zealand high and hill country soils, Hill Country. Grassland Research and Practice Series 2016, 16, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Texture | Loamy sandy |

| Structure | Granular |

| Total porosity | 54% in the first horizon |

| Humus content | 2.8% |

| pH | 5.03 ÷ 5.12 |

| CEC (cation exchange capacity) | 9.27 ÷ 9.42 cmol/kg |

| Caexch (exchangeable Ca) | 4.63 ÷4.71 cmol/kg |

| Mgexch (exchangeable Mg) | 0.74 ÷ 0.85 cmol/kg |

| Kexch (exchangeable K) | 0.140 ÷ 0.151 cmol/kg |

| Alexch (exchangeable Al) | 2.780 ÷ 3.300 cmol/kg |

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| V1, d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.08±0.10 | 5.62±0.06ab | 6.47±0.05a | 6.39±0.04b |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.4±0.18 | 9.71±0.05c | 10.21±0.10d | 10.88±0.14b |

| Alexch(cmol/kg) | 3.10±0.310 | 1.98±0.050 | 0.43±0.080b | 0.08±0.060b |

| V1, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.15±0.04 | 5.39±0.02cde | 5.43±0.08d | 5.64±0.05d |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.31±0.12 | 9.62±0.04c | 10.12±0.24d | 10.05±0.16c |

| Alexch(cmol/kg) | 2.79±0.470 | 2.43±0.460 | 1.98±0.250a | 1.71±0.530a |

| V2, d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.12±0.02 | 5.80±0.06a | 6.55±0.03a | 6.33±0.05b |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.27±0.03 | 9.92±0.08c | 10.79±0.27c | 10.37±0.08c |

| Alexch (cmol/kg) | 2.78±0.250 | 1.74±0.290 | 0.31±0.030b | 0.05±0.010b |

| V2, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.24±0.05 | 5.6±0.12abc | 5.72±0.04c | 5.85±0.06c |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.24±0.16 | 9.93±0.03c | 11.1±0.15abc | 10.19±0.19c |

| Alexch (cmol/kg) | 2.590±0.140 | 2.29±0.440 | 1.84±0.230a | 1.61±0.260a |

| V3, d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.03±0.05 | 5.49±0.04abc | 6.28±0.04b | 6.6±0.05a |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.42±0.11 | 10.61±0.06a | 11.04±0.15a | 12.43±0.17a |

| Alexch(cmol/kg) | 3.300±0.590 | 2.24±0.540 | 0.44±0.210b | - |

| V3, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.13±0.03 | 5.21±0.1cde | 5.39±0.06d | 5.36±0.05a |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.3±0.25 | 10.47±0.24a | 10.75±0.08abc | 12.21±0.19a |

| Alexch(cmol/kg) | 2.330±0.540 | 2.23±0.190 | 1.94±0.300a | 1.7±0.400a |

| V4 d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.06±0.12 | 5.62±0.08ab | 6.57±0.03a | 6.63±0.08a |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.41±0.19 | 11.22±0.20b | 11.55±0.13bc | 12.09±0.19a |

| Alexch (cmol/kg) | 3.290±0.360 | 2.19±0.480 | 0.35±0.130b | - |

| V4, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| pH | 5.17±0.03 | 5.31±0.08de | 5.45±0.07d | 5.6±0.14d |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 9.26±0.06 | 11.05±0.16b | 11.44±0.17 | 12.13±0.15a |

| Alexch (cmol/kg) | 2.790±0.630 | 2.61±0.370 | 2.1±0.210a | 1.86±0.460a |

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| V1, d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.70±0.32 | 5.82±0.79ab | 7.25±0.56ab | 8.10±0.30ab |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.85±0.085 | 0.97±0.174 | 1.03±0.069 | 1.12±0.188 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.151±0.022 | 0.212±0.017 | 0.264±0.038 | 0.286±0.082abc |

| V1, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.65±0.39 | 5.69±0.44ab | 6.18±0.71b | 7.03±0.30bc |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.740±0.123 | 0.77±0.147 | 0.82±0.182 | 0.91±0.058 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.122±0.013 | 0.159±0.024 | 0.191±0.017 | 0.209±0.023c |

| V2, d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.63±0.50 | 6.45±0.56ab | 7.66±0.54ab | 7.46±0.47bc |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.740±0.028 | 0.82±0.060 | 1.04±0.06 | 1.06±0.064 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.140±0.035 | 0.225±0.05 | 0.267±0.027 | 0.297±0.029abc |

| V2, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.62±0.39 | 5.45±0.46b | 6.54±0.28b | 6.82±0.20c |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.830±0.046 | 0.89±0.102 | 0.93±0.115 | 1.03±0.047 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.110±0.019 | 0.172±0.021 | 0.213±0.014 | 0.215±0.016bc |

| V3, d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.71±0.31 | 6.47±0.56ab | 7.50±0.49ab | 8.20±0.75ab |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.750±0.051 | 0.85±0.016 | 1.1±0.101 | 1.15±0.068 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.150±0.023 | 0.231±0.042 | 0.283±0.054 | 0.334±0.044ab |

| V3, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.65±0.37 | 5.28±0.51b | 6.20±0.80b | 7.65±0.43bc |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.840±0.062 | 0.92±0.198 | 0.99±0.091 | 1.02±0.127 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.129±0.024 | 0.18±0.095 | 0.22±0.065 | 0.254±0.04abc |

| V4 d1=0-20 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.70±0.30 | 6.95±0.26a | 8.20±0.38a | 9.06±0.26a |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.75±0.073 | 0.85±0.051 | 1.03±0.126 | 1.1±0.202 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.142±0.013 | 0.246±0.048 | 0.289±0.063 | 0.36±0.041a |

| V4, d2=20-40 cm | ||||

| Caexch (cmol/kg) | 4.65±0.37 | 5.96±0.31ab | 7.00±0.52b | 7.85±0.43bc |

| Mgexch (cmol/kg) | 0.840±0.113 | 0.9±0.150 | 0.88±0.122 | 1.01±0.016 |

| Kexch (cmol/kg) | 0.120±0.011 | 0.21±0.069 | 0.243±0.046 | 0.274±0.028abc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).