Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Diagnostic Tests

2.3. Optical Microcopy Test and Determination of Spore Number

2.4. DNA Extraction of Nosema sp. in Honey Bees

2.5. Detection and Identification of Nosema sp. by Multiplex PCR

2.6. Sequencing, Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.7. Detection of Spores by Fluorescence Microscopy

3. Results

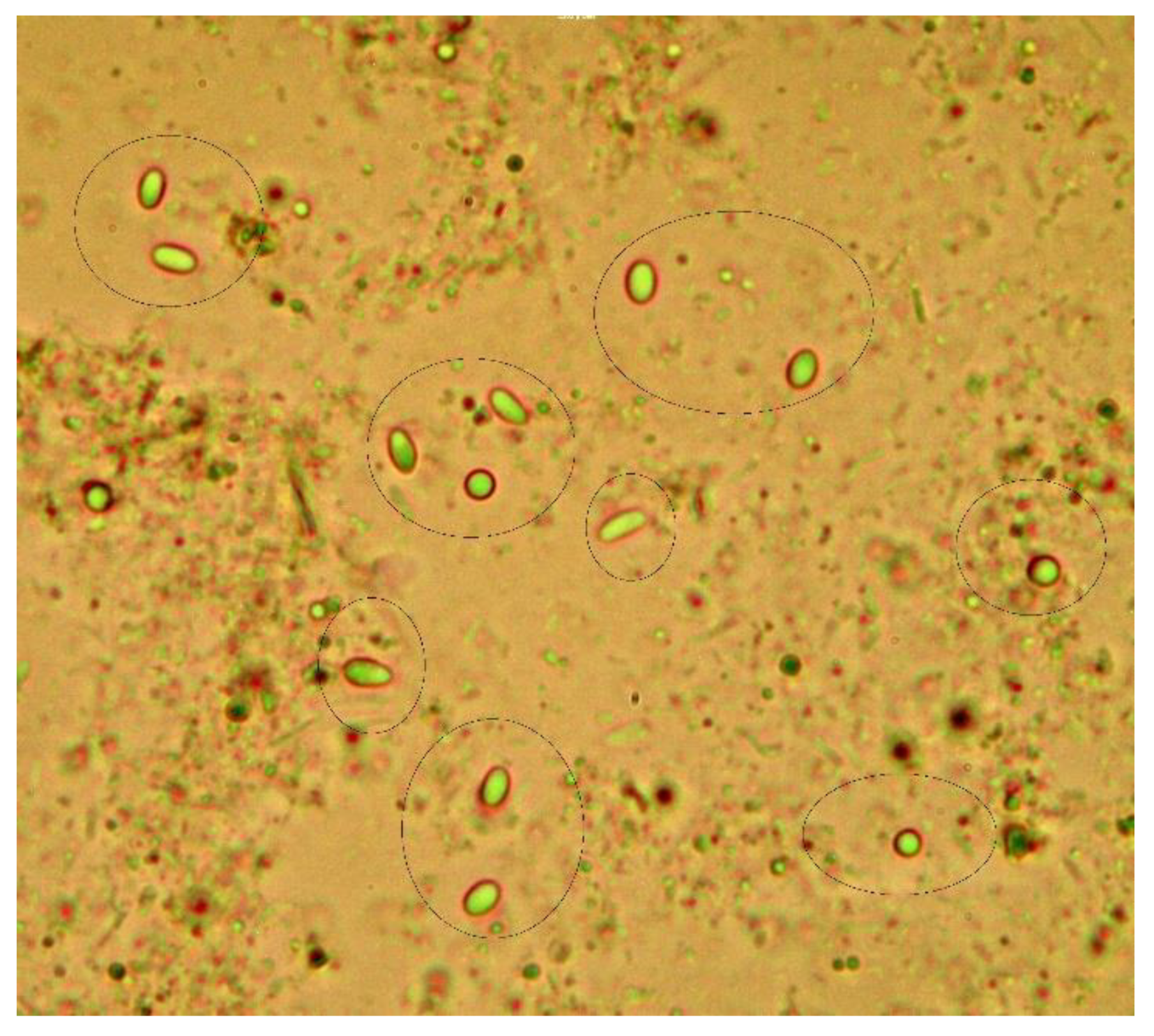

3.1. Detection of Nosema sp. Spores by Optical Microscopy

3.2. Identification of Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae by PCR

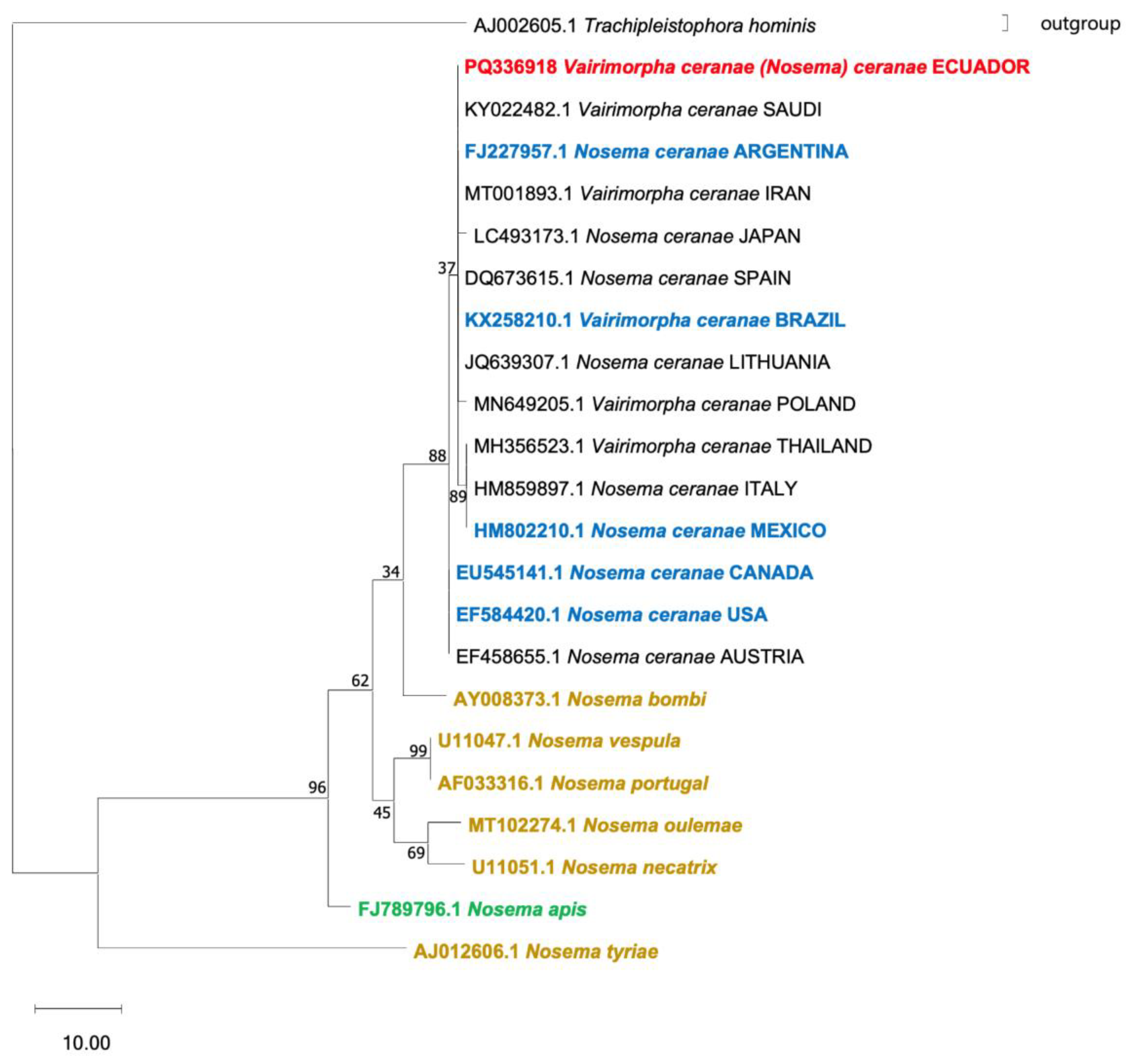

3.3. Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of N. ceranae

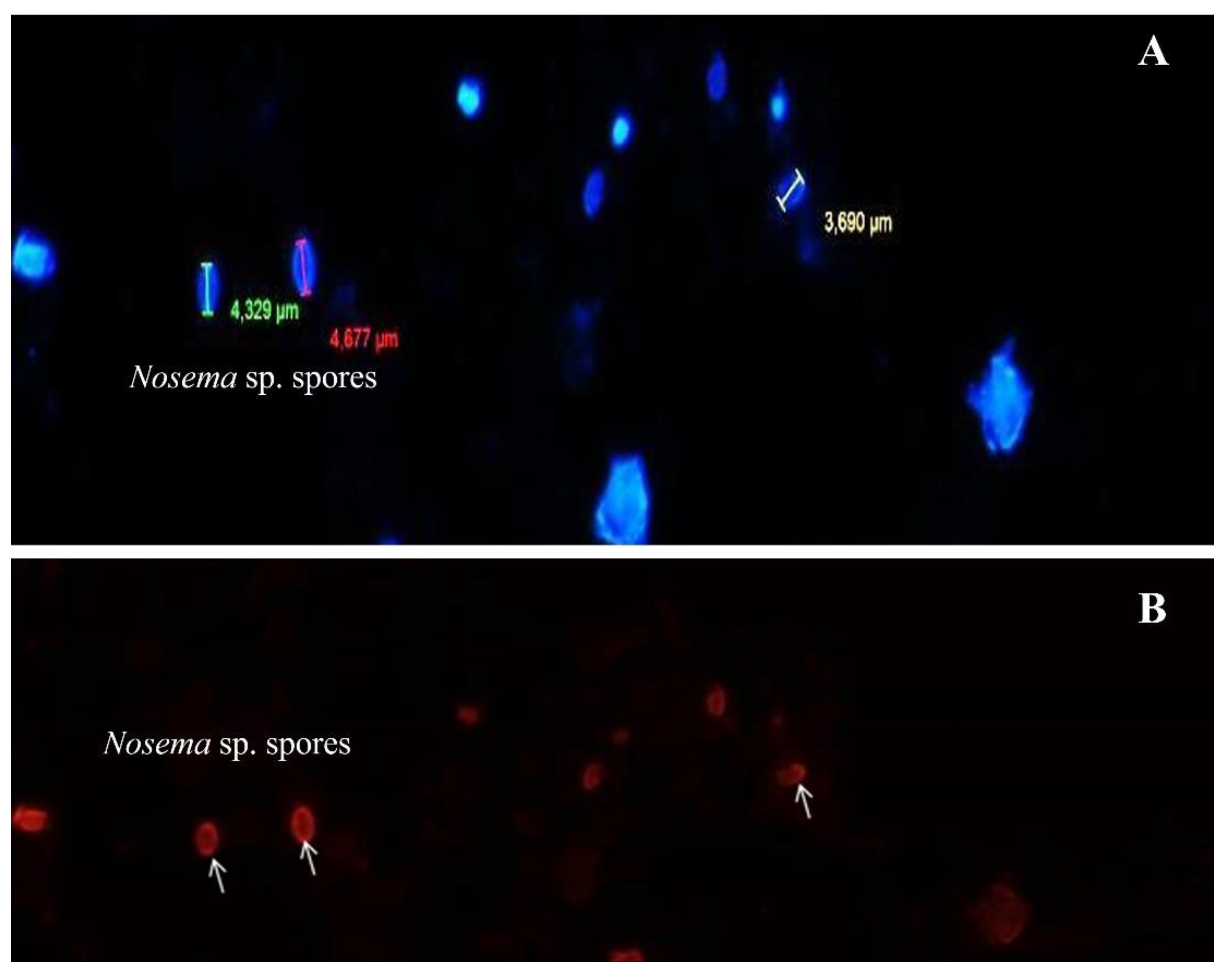

3.4. Detection of Nosema sp. by Fluorescence Microscopy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GISAH | Grupo de Investigación en Sanidad Animal y Humana |

| RPB1 | RNA Polymerase II Subunit RPB1 |

| 16 S RNAr | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| N. apis | Nosema apis |

| AGROCALIDAD | Agencia de Regulación y Control Fito y Zoosanitario (Ecuador) |

| N. ceranae | Nosema ceranae |

| OIE | World Organization for Animal Health |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| RNAse | Ribonuclease |

| dNTP | Deoxyribonucleoside Triphosphate |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- AGROCALIDAD Programa Nacional Sanitario Apícola. 2016, 60–60.

- Vávra, J.; Ronny Larsson, J.I. Structure of Microsporidia. In Microsporidia: Pathogens of Opportunity; Weiss, L.M., Becnel, J.J., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell, 2014; pp. 729–729.

- Sprague, V. Characterization and Composition of the Genus Nosema. In Selected Topics on the genus Nosema (Microsporida); Brooks, W.M., Ed.; 1978; Vol. 11, pp. I6–I6.

- Wasson, K.; Peper, R.L. Mammalian Microsporidiosis; Vet Pathol; 2000; Vol. 37, pp. 113–128;

- Becnel, J.J.; Andreadis, T.G. Microsporidia in Insects. In Microsporidia: Pathogens of Opportunity; Weiss, L.M., Becnel, J.J., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell, 2014; pp. 521–570 ISBN 978-1-118-39526-4.

- Wittner, M.; Weiss, L.M. The Microsporidia and Microsporidiosis; ASM press: Washington, DC, 1999; p. 553;

- Zander, E. Tierische Parasiten Als Krankheitserreger Bei Der Biene. Münch. Bienenztg. 1909, 196–204.

- Higes, M.; Martín, R.; Meana, A. Nosema ceranae, a New Microsporidian Parasite in Honeybees in Europe. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2006, 92, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, J.; Besana, A.M.; Genersch, E.; Gisder, S.; Nanetti, A.; Tam, D.Q.; Chinh, T.X.; Puerta, F.; Ruz, J.M.; Kryger, P.; et al. Widespread Dispersal of the Microsporidian Nosema Ceranae, an Emergent Pathogen of the Western Honey Bee, Apis Mellifera. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2007, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, I.; Feng, F.; da Silva, A.; Slemenda, S.B.; Pieniazek, N.J. Nosema Ceranae n. sp. (Microspora, Nosematidae), Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a Microsporidian Parasite of the Asian Honey Bee Apis cerana (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Eur. J. Protistol. 1996, 32, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D.; Nicholls, E.; Botías, C.; Rotheray, E.L. Bee Declines Driven by Combined Stress from Parasites, Pesticides, and Lack of Flowers. Science 2015, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, P.; Georgieva, A.A.; Radoslavov, G.; Sirakova, D.; Dzhebir, G.; Shumkova, R.; Neov, B.B.; Bouga, M.; Author, C.; Hristov, P.; et al. The First Report of the Prevalence of Nosema ceranae in Bulgaria. PeerJ 2018.

- Martín-Hernández, R.; Bartolomé, C.; Chejanovsky, N.; Le Conte, Y.; Dalmon, A.; Dussaubat, C.; García-Palencia, P.; Meana, A.; Pinto, M.A.; Soroker, V.; et al. Nosema ceranae in Apis mellifera: A 12 Years Postdetection Perspective. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 1302–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papini, R.; Mancianti, F.; Canovai, R.; Cosci, F.; Rocchigiani, G.; Benelli, G.; Canale, A. Prevalence of the Microsporidian Nosema ceranae in Honeybee (Apis mellifera) Apiaries in Central Italy. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilova, V.Y.; Konopatskaia, I.; Luzyanin, S.L.; Woyciechowski, M.; Blinov, A.G. Parasites of the Genus Nosema, Crithidia and Lotmaria in the Honeybee and Bumblebee Populations: A Case Study in India. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2017, 21, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarev, Y.S.; Huang, W.-F.; Solter, L.F.; Malysh, J.M.; Becnel, J.J.; Vossbrinck, C.R. A Formal Redefinition of the Genera Nosema and Vairimorpha (Microsporidia: Nosematidae) and Reassignment of Species Based on Molecular Phylogenetics. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2020, 169, 107279–107279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, C.; Higes, M.; Hernández, R.M.; Chen, Y.P.; Evans, J.D.; Huang, Q. The Recent Revision of the Genera Nosema and Vairimorpha (Microsporidia: Nosematidae) Was Flawed and Misleads the Bee Scientific Community. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2024, 206, 108146–108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali, K.; Nora, C.-A.; Mohamed, C.; Hakim, T.; Khaoula, B.; Semir, G.; Suheil, B. First Molecular Detection and Geographical Distribution of Nosema apis & Nosema ceranae in Indigenous Honey Bees Reared in Algeria. Genet. Biodivers. J. 2023, 7, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.R.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Higes, M.; Segura, S.K.; Henriques, D.; Pinto, M.A. First Detection of Nosema ceranae in Honey Bees (Apis mellifera L.) of the Macaronesian Archipelago of Madeira. J. Apic. Res. 2023, 62, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, P.; Guzman-Novoa, E.; Goodwin, P.H. High Genetic Variability of Nosema ceranae Populations in Apis mellifera from East Asia Compared to Central Asia and the Americas. Biol. Invasions 2022, 24, 3133–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani Baran, A.; Kalami, H.; Mazaheri, J.; Hamidian, G. Vairimorpha ceranae Was the Only Detected Microsporidian Species from Iranian Honey Bee Colonies: A Molecular and Phylogenetic Study. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekagirbas, M.; Hacilarlioglu, S.; Kanlioglu, H.; Aydin, H.B.; Koc, B.; Bilgic, H.B.; Karagenc, T.; Bakirci, S. Dominancy of Vairimorpha ceranae: Microscopic and Molecular Detection in Aydın, West Turkey. Comp. Parasitol. 2025, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blot, N.; Clémencet, J.; Jourda, C.; Lefeuvre, P.; Warrit, N.; Esnault, O.; Delatte, H. Geographic Population Structure of the Honeybee Microsporidian Parasite Vairimorpha (Nosema) ceranae in the South West Indian Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12122–12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjy, M.S.; Shaher, K.W. Molecular Detection of Vairimorpha ceranae and Determining the Incidence Rate of Honey Bee Hives and Workers of Apis mellifera L. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1449, 012054–012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-F.; Jiang, J.-H.; Chen, Y.-W.; Wang, C.-H. A Nosema ceranae Isolate from the Honeybee Apis mellifera. Apidologie 2007, 38, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.W.; dos Santos, L.G.; Sattler, A.; Message, D.M.; Alves, M.L.T.M.F.; Martins, M.F.; Grassi-Sella, M.L.; Francoy, T.M. Nosema ceranae Has Been Present in Brazil for More than Three Decades Infecting Africanized Honey Bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2013, 114, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, S.K.; Sarlo, E.G.; Porrini, M.P.; Braunstein, M.; Eguaras, M.J. Genetic Variation and Widespread Dispersal of Nosema ceranae in Apis mellifera Apiaries from Argentina. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 110, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio Agrícola Ganadero (SAG) Chile Informe de Caso de Nosema ceranae En La Región Del Bío Bío, Octubre de 2009; 2010.

- Invernizzi, C.; Abud, C.; Tomasco, I.H.; Harriet, J.; Ramallo, G.; Campá, J.; Katz, H.; Gardiol, G.; Mendoza, Y. Presence of Nosema ceranae in Honeybees (Apis Mellifera) in Uruguay. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2009, 101, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, M.; Antúnez, K.; Ivernizzi, C.; Aldea, P.; Vargas, M.; Negri, P.; Brasero, C.; De Jong, D.; Message Dejair; Weinstein Teixeira, E. Honeybee Health in South America. Springer Verl. 2016, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Stoner, M.; Hatter, A.; Traver, B.E. Genetic Diversity and Prevalence of Varroa destructor, Nosema apis, and N. ceranae in Managed Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera) Colonies in the Caribbean Island of Dominica, West Indies. J. Apic. Res. 2018, 57, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Molina, C.; Correa-Benítez, A.; Hamiduzzaman, M.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Nosema ceranae Is an Old Resident of Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Colonies in Mexico, Causing Infection Levels of One Million Spores per Bee or Higher during Summer and Fall. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 141, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.R.; Shafer, A.B.A.; Rogers, R.E.L.; Shutler, D.; Stewart, D.T. First Detection of Nosema ceranae, a Microsporidian Parasite of European Honey Bees (Apis mellifera), in Canada and Central USA. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 97, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plischuk, S.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Prieto, L.; Lucía, M.; Botías, C.; Meana, A.; Abrahamovich, A.H.; Lange, C.; Higes, M. South American Native Bumblebees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Infected by Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia), an Emerging Pathogen of Honeybees (Apis mellifera). Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009, 1, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulo, N.; Antúnez, K.; Salvarrey, S.; Santos, E.; Branchiccela, B.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Higes, M.; Invernizzi, C. High Prevalence and Infection Levels of Nosema ceranae in Bumblebees Bombus atratus and Bombus bellicosus from Uruguay. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 130, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrini, M.P.; Porrini, L.P.; Garrido, P.M.; de Melo e Silva Neto, C.; Porrini, D.P.; Muller, F.; Nuñez, L.A.; Alvarez, L.; Iriarte, P.F.; Eguaras, M.J. Nosema ceranae in South American Native Stingless Bees and Social Wasp. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, I. Nosema apis—a Parasite in the Honey Bee Colony. Bee World 1993, 74, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, I. Nosema ceranae in European Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S73–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIE Nosemosis de Las Abejas Melíferas. In Manual Terrestres de la OIE; 2018.

- Smith, M.L. The Honey Bee Parasite Nosema ceranae: Transmissible via Food Exchange? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43319–e43319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, L. The Infection of the Ventriculus of the Adult Honeybee by Nosema apis (Zander). Parasitology 1955, 45, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussaubat, C.; Brunet, J.-L.; Higes, M.; Colbourne, J.K.; Lopez, J.; Choi, J.-H.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Botías, C.; Cousin, M.; McDonnell, C.; et al. Gut Pathology and Responses to the Microsporidium Nosema ceranae in the Honey Bee Apis mellifera. PloS One 2012, 7, e37017–e37017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-F.; Solter, L.F.; Yau, P.M.; Imai, B.S. Nosema ceranae Escapes Fumagillin Control in Honey Bees. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003185–e1003185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higes, M.; García-Palencia, P.; Urbieta, A.; Nanetti, A.; Martín-Hernández, R. Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae Tissue Tropism in Worker Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). Vet. Pathol. 2020, 57, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Evans, J.D.; Murphy, C.; Gutell, R.; Zuker, M.; Gundensen-Rindal, D.; Pettis, J.S. Morphological, Molecular, and Phylogenetic Characterization of Nosema ceranae, a Microsporidian Parasite Isolated from the European Honey Bee, Apis mellifera. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2009, 56, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, S.L.; Kramer, C.; Calle, S.; Carroll, M.; Heien, M.; DeGrandi-Hoffman, G. Nosema ceranae Parasitism Impacts Olfactory Learning and Memory and Neurochemistry in Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, H.L.; Aronstein, K.A.; Grozinger, C.M. Chronic Parasitization by Nosema Microsporidia Causes Global Expression Changes in Core Nutritional, Metabolic and Behavioral Pathways in Honey Bee Workers (Apis mellifera). BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.R.; Shutler, D.; Burgher-MacLellan, K.L.; Rogers, R.E.L. Infra-Population and -Community Dynamics of the Parasites Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae, and Consequences for Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Hosts. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botías, C.; Martin-Hernández, R.; Barrios, L.; Meana, A.; Higes, M. Nosema spp. Infection and Its Negative Effects on Honey Bees (Apis mellifera iberiensis) at the Colony Level. Vet. Res. 2013, 44, 25–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsen, B.; Guzman-Novoa, E.; Hamiduzzaman, M.M.; Eccles, L.; Lacey, B.; Ruiz-P??rez, R.A.; Nasr, M. Higher Prevalence and Levels of Nosema ceranae than Nosema apis Infections in Canadian Honey Bee Colonies. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.A.C.; Valencia, G.L.; Cabrera, C.O.; Gómez Gómez, S.D.; Torres, K.M.; Blandón, K.O.E.; Guerrero Velázquez, J.G.; Paz, L.E.S.; Trasviña Muñoz, E.; Monge Navarro, F.J. Prevalence and Geographical Distribution of Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae in Apiaries of Northwest Mexico Using a Duplex Real-Time PCR with Melting-Curve Analysis. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 59, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.J.; Al-Ghamdi, A.; Nuru, A.; Khan, K.A.; Alattal, Y. Geographical Distribution and Molecular Detection of Nosema ceranae from Indigenous Honey Bees of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederle, N.; Lobo, M.; Morariu, S.; Morariu, F.; Darabus, G.; Mederle, O.A.; Matos, O. Microscopic and Molecular Detection of Nosema ceranae in Honeybee Apis mellifera L. from Romania:: Status on Pathogen Worldwide Distribution. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 3761–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkırım, A.; Schiesser, A.; Keskin, N. Dynamics of Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae Co-Infection Seasonally in Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera L.) Colonies. J. Apic. Sci. 2019, 63, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, I.; Chauzat, M.-P.; Chen, Y.-P.; Doublet, V.; Genersch, E.; Gisder, S.; Higes, M.; McMahon, D.P.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Natsopoulou, M.; et al. Standard Methods for Nosema Research. J. Apic. Res. 2013, 52, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Hernández, R.; Meana, A.; Prieto, L.; Salvador, A.M.; Garrido-Bailón, E.; Higes, M. Outcome of Colonization of Apis Mellifera by Nosema ceranae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 6331–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroee, F.; Azizi, H.; Shiran, B.; Pirali Kheirabadi, K. Molecular Identification of Nosema Species in Provinces of Fars, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari and Isfahan (Southwestern Iran). Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017, 7, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botias, C.; Martin-Hernandez, R.; Garrido-Bailon, E.; Anderson, D.; Higes, M. Nosema ceranae Isolate NOS034 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene, Partial Sequence - Nucleotide - NCBI. 2009.

- Gisder, S.; Genersch, E. Molecular Differentiation of Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae Based on Species-Specific Sequence Differences in a Protein Coding Gene. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2013, 113, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacela-Spychalska, K.; Wattier, R.; Teixeira, M.; Cordaux, R.; Quiles, A.; Grabowski, M.; Wroblewski, P.; Ovcharenko, M.; Grabner, D.; Weber, D.; et al. Widespread Infection, Diversification and Old Host Associations of Nosema Microsporidia in European Freshwater Gammarids (Amphipoda). PLOS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011560–e1011560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ironside, J.E. Multiple Losses of Sex within a Single Genus of Microsporidia. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 48–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maside, X.; Gómez-Moracho, T.; Jara, L.; Martín-Hernández, R.; De la Rúa, P.; Higes, M.; Bartolomé, C. Population Genetics of Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae: One Host (Apis mellifera) and Two Different Histories. PloS One 2015, 10, e0145609–e0145609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Moracho, T.; Maside, X.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Higes, M.; Bartolomé, C. High Levels of Genetic Diversity in Nosema ceranae within Apis mellifera Colonies. Parasitology 2014, 141, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, B.; Dogaroglu, M. The Impact of Nosema apis Z. Infestation of Honey Bee (Apis mellifera L.) Colonies after Using Different Treatment Methods and Their Effects on the Population Levels of Workers and Honey Production on Consecutive Years. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2005, 8, 1142–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiduzzaman, M.M.; Guzman-Novoa, E.; Goodwin, P.H. A Multiplex PCR Assay to Diagnose and Quantify Nosema infections in Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 105, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, J.W. A Fluorescent Method for Visualization of Nosema Infection in Whole-Mount Honey Bee Tissues. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 135, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbrath, M.O.; Van Tran, T.; Huang, W.-F.; Solter, L.F.; Tarpy, D.R.; Lawrence, F.; Huang, Z.Y. Comparative Virulence and Competition between Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae in Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 125, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, L.; Beaman, L.; Holloway, B.; Rinderer, T.E. External and Internal Detection of Nosema ceranae on Honey Bees Using Real-Time PCR. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 109, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalanski, A.L.; Tripodi, A.D.; Trammel, C.E. Molecular Detection of Nosema apis and N. ceranae from Southwestern and South Central USA Feral Africanized and European Honey Bees, Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Fla. Entomol. 2014, 97, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, M.-P.; Ribière, M.; Chauzat, M.-P. Recent Molecular Biology Methods for Foulbrood and Nosemosis Diagnosis. Rev. Sci. Tech. OIE 2013, 32, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoguimba, E. Determinación de La Prevalencia y Georreferenciación de Varoosis y Nosemosis En Colmenares de Apis mellifera En Tres Provincias Del Ecuador En El Año 2015 (Chimborazo, Tungurahua y Bolivar). 2015, 95–95.

- Vivas, J.L. Prevalencia de Nosema (Nosema spp.) En Colmenares de La Región Norte y Centro Norte Del Ecuador. 2015, 81–81.

- Gajger, I.T.; Vugrek, O.; Grilec, D.; Petrinec, Z. Prevalence and Distribution of Nosema ceranae in Croatian Honeybee Colonies. Vet. Med. (Praha) 2010, 55, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higes, M.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Meana, A. Nosema ceranae in Europe: An Emergent Type C Nosemosis. Apidologie 2010, 41, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Hernández, R.; Meana, A.; García-Palencia, P.; Marín, P.; Botías, C.; Garrido-Bailón, E.; Barrios, L.; Higes, M. Effect of Temperature on the Biotic Potential of Honeybee Microsporidia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2554–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagastume, S.; del Águila, C.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Higes, M.; Henriques-Gil, N. Polymorphism and Recombination for rDNA in the Putatively Asexual Microsporidian Nosema ceranae, a Pathogen of Honeybees. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | Number and percentage of apiaries of the national totala | Number and percentage of apiaries Sampling | Number and percentage of beehives of the national totalb | Number and percentage of beehives Sampling |

| Carchi | 40 (4,43%) | 4 (10%) | 974 (7,99%) | 33 (3,39%) |

| Imbabura | 74 (8,20%) | 13 (17,58%) | 1025 (8,41%) | 68 (6,64%) |

| Pichincha | 108 (11,97%) | 13 (12,04) | 2778 (22,79) | 63 (2,28%) |

| Total | 222/902a (24,61%) | 30 (13,51%) | 4777/12188 b | 164 (3,43%) |

| Primer name | Sequence (5’-3’) | Species | Fragment size |

| NosaRNAPol-F2* NosaRNAPol-R2 |

AGCAAGAGACGTTTCTGGTACCTCA CCTTCACGACCACCCATGGCA |

Nosemaapis | 297 bp |

| NoscRNAPol-F2* NoscRNAPol-R2 |

TGGGTTCCCTAAACCTGGTGGTTT TCACATGACCTGGTGCTCCTTCT |

Nosemaceranae | 662 bp |

| 218MITOC-FOR** 218MITOC-REV |

CGGCGACGATGTGATATGAAAATATTAA CCCGGTCATTCTCAAACAAAAAACCG |

Nosemaceranae | 218-219 bp |

| Province | Number apiaries | Microscopy | PCR | Total hives | Microscopy | PCR | ||||

| Number – prevalence in % (95% CI) Nosema sp. |

Number - prevalence in % (95% CI) N. apis |

Number – prevalence in % (95% CI) N. ceranae |

Number -prevalence in% (95% CI) Co-infection |

Number – prevalence in % (95% CI) Nosema sp. |

Number – prevalence in % (95% CI) N. apis |

Number – prevalence in % (95% CI) N. ceranae |

Number – prevalence in % (95% CI) Co-infection |

|||

| Carchi | 4 | 2 - 50% (6.76 – 93.24) |

3 - 75% (19.41 – 99.37) |

1 - 25% (0.63 – 80.59) |

1 - 25% (0.63 – 80.59) |

33 | 6 - 18.18% (6.98 – 35.46) |

6 – 18.18% (6.98 – 35.46) |

3 - 9.09% (1.92 – 24.33) |

1 - 3.03% (0.08 – 15.76) |

| Imbabura | 13 | 3 - 23.08% (5.04 -53.81) |

5 – 38.46% (13.86 – 68.42) |

7 – .15% (19.22 -74.87) |

0-* | 68 | 3 - 4.41% (0.92 – 12.36) |

10 – 14.71% (7.282- 25.39) |

9 - 13.24% (6.33 – 23.64) |

0-* |

| Pichincha | 12 | 7 - 58.33% (27.67 - 84.83) |

4 - 33.33% (9.92 – 65.11) |

8 - 66.67% (34.89 – 90.08) |

2 – 8.33% (0.21 – 38.48) |

63 | 19 - 30.16% (19.23 – 53.02) |

8 - 12.70% (5.65 - 23.50) |

23 - 36.51% (24.73 – 49.6) |

1 - 1.59% (0.04 – 8.53) |

| TOTAL | 29 | 12 – 41.38% (23.52 – 61.06) |

12 – 41.38% (25.52 – 61.06) |

15 – 51.72% (32.53 – 70.55) |

2 – 6.90% (0.85 – 22.77) |

164 | 28 - 17.07% (11.65 – 23.72) |

24 - 14.63% (9.61 – 20.99) |

35 - 21.34% (15.34 – 28.41) |

2 - 1.22% (0.15 4.34) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).