Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Acquisition of Commercial Honey Samples

2.2. eDNA Extraction from Honey Samples

2.3. eDNA Purification

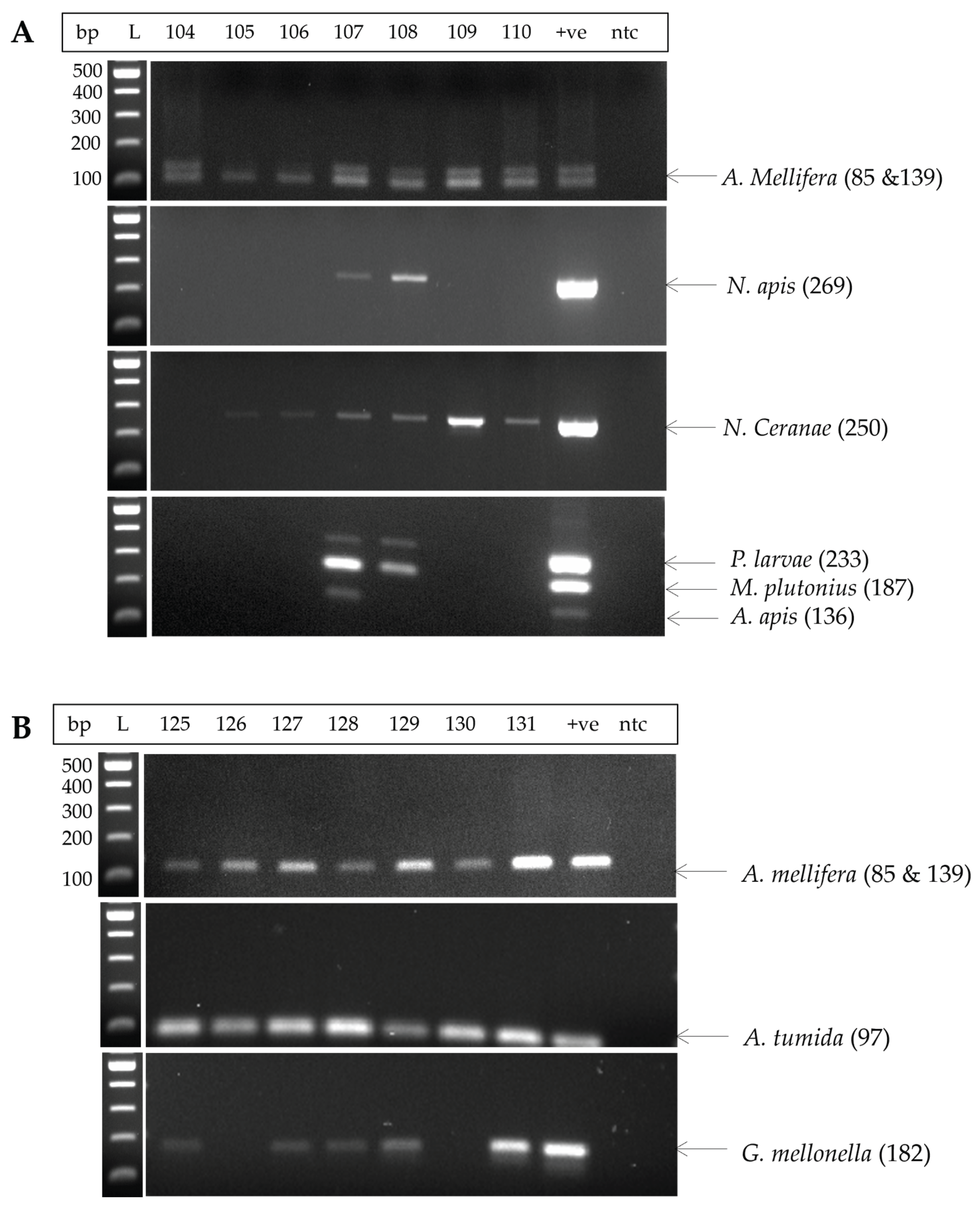

2.4. PCR Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

| Target species | Primer name1 | Accession No. | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Amplified region | Product size (bp) | Reference |

| Singleplex PCR | ||||||

| Apis mellifera | AM Forward AM Reverse |

GGCAGAATAAGTGCATTG TTAATATGAATTAAGTGGGG |

suppl | C 85, M 1392 | [44] | |

| Nosema apis | Nose_apis_chen_F Nose_apis_chen_R |

U97150.1 |

CCATTGCCGGATAAGAGAGT CCACCAAAAACTCCCAAGAG |

SSUrRNA | 269 | [45] |

| Nosema ceranae | Nose_cera_chen_F Nose_cera_chen_R |

DQ486027.1 |

CGGATAAAAGAGTCCGTTACC TGAGCAGGGTTCTAGGGAT |

SSUrRNA | 250 | [45] |

| Aethina tumida | Atum-3F Atum-3R |

MF943248.1 |

CCCATTTCCATTATGTWYTATCTATAGG CTATTTAAAGTYAATCCTGTAATTAATGG |

COI | 97 | [46] |

| Galleria mellonella | GallMelCox1-F GallMelCox1-R |

KT750964.1 |

TGAACTTGGTAATCCTGGTTCT TATTATTAAGTCGGGGGAAAGC |

COI | 182 | [46] |

| Multiplex PCR | ||||||

|

Paenibacillus larvae Melissococcus plutonius Ascosphaera apis |

Han233PaeLarv16S_F Han233PaeLarv16S_R Mp_Arai187_F Mp_Arai187_R AscosFORa AscosREVa |

NZCP019687.1 AB778538.1 U68313.1 |

GTGTTTCCTTCGGGAGACG CTCTAGGTCGGCTACGCATC TGGTAGCTTAGGCGGAAAAC TGGAGCGATTAGAGTCGTTAGA TGTGTCTGTGCGGCTAGGTG GCTAGCCAGGGGGGAACTAA |

16S rRNA NapA 18S rRNA |

233 187 136 |

[47] |

| Target Species | Steps | Optimized Conditions | Time | Cycle |

| Multiplex PCR |

Initial Denaturation Annealing Extension Final Extension |

95°C 95°C 63°C 72°C 72°C |

2 min 1 min 1 min 1 min 5 min |

35x |

|

P. larvae M. plutonius A. apis | ||||

| Single plex PCR | ||||

|

N. apis N. ceranae |

Initial Denaturation Annealing Extension Final Extension |

95°C 94°C 58.6°C 68°C 72°C |

2 min 15 sec 30 sec 1 min 7 min |

35x |

| A. tumida | Initial Denaturation Annealing Extension Final Extension |

95°C 98°C 54°C 72°C 72°C |

3 min 20 sec 30 sec 1 min 7 min |

35x |

| G. mellonella | Initial Denaturation Annealing Extension Final Extension |

95°C 98°C 61°C 72°C 72°C |

3 min 1 min 1 min 1 min 1 min |

35x |

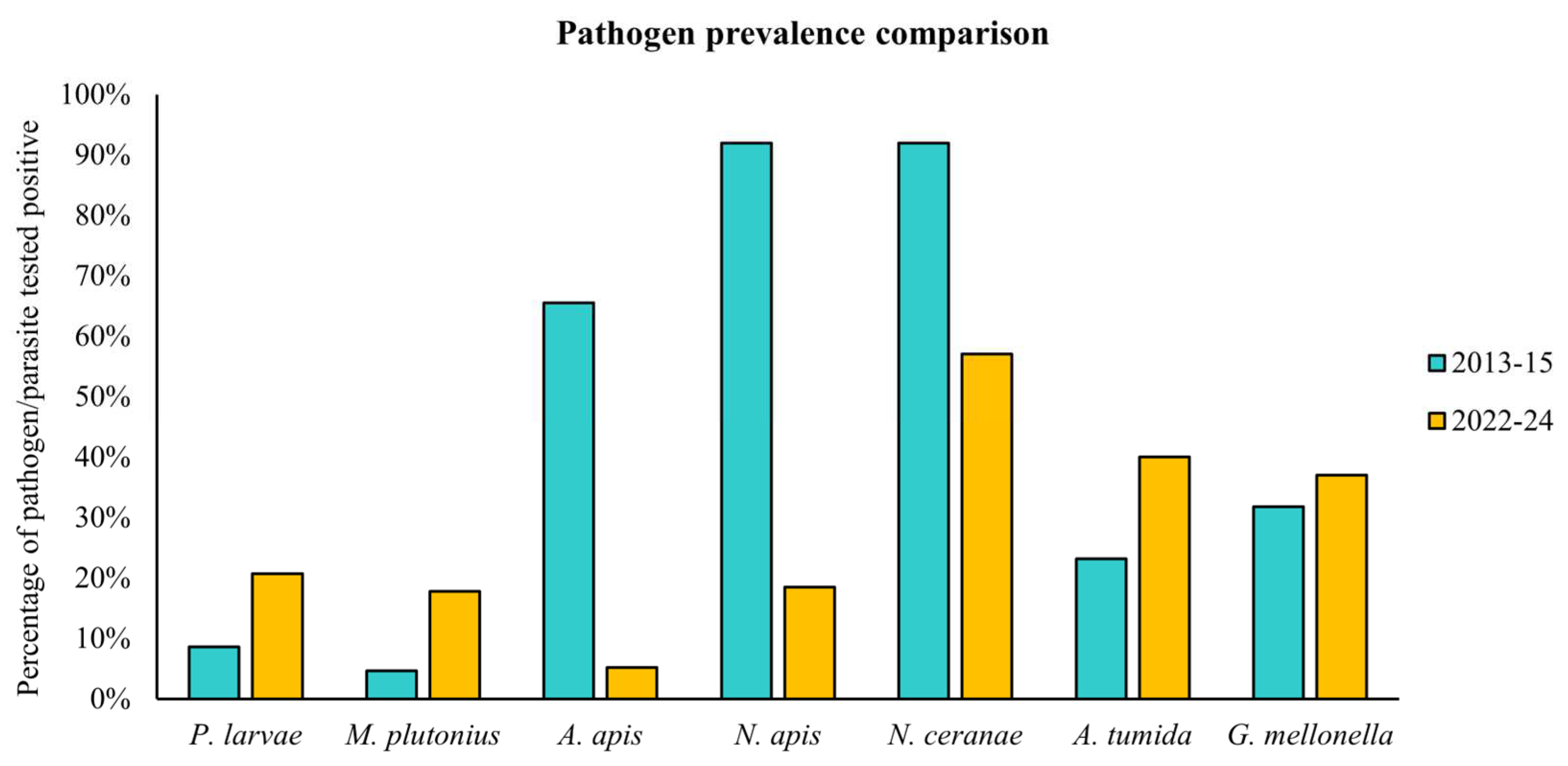

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Extracted DNA

3.2. Prevalence Pattern Across Different Australian States

3.3. Pathogen Prevalence on Kangaroo Island

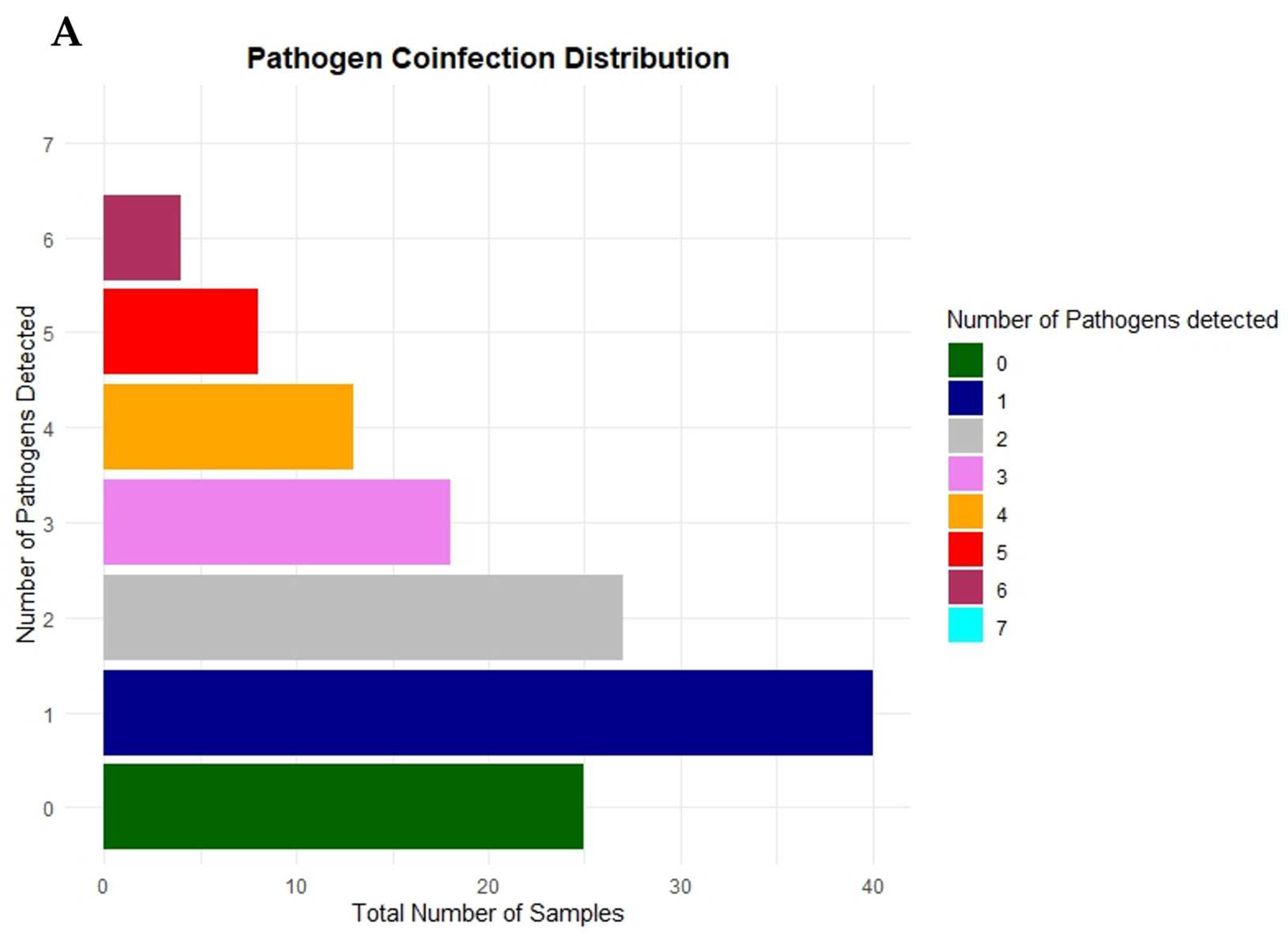

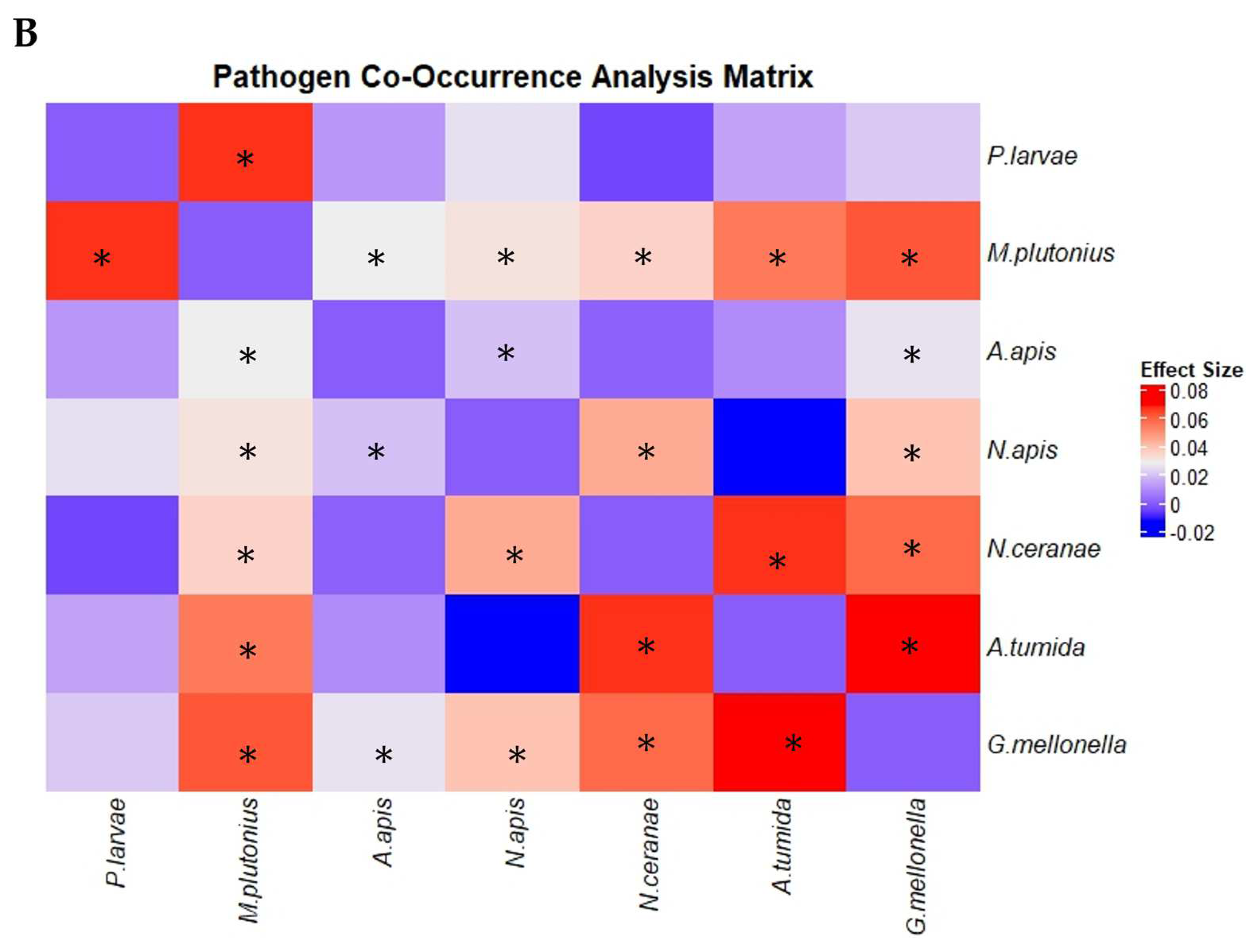

3.4. Trends in Concurrent Infections

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hagan, T. 2022. Evolution and ecology of invasive honey bees.PhD thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney, 10th July 2023.The University of Sydney, Library. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2123/31486 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Roberts, J.; Anderson D.; Durr P. Upgrading knowledge on pathogens (particularly viruses) of Australian honey bees. Rural Industries Research & Development Corporation (RIRDC) Canberra. 2015.

- Chapman, N.C.; Colin, T.; Cook, J.; da Silva, C.R.; Gloag, R.; Hogendoorn, K.; et al. The final frontier: ecological and evolutionary dynamics of a global parasite invasion. Biol. Lett. 2023, 19,20220589.

- Brettell, L.E.; Riegler, M.; O’brien, C.; Cook, J.M. Occurrence of honey bee-associated pathogens in Varroa-free pollinator communities. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2020, 171, 107344.

- Borba, R.S.; Hoover, S.E.; Currie, R.W.; Giovenazzo, P.; Guarna, M.M.; Foster, L.J.; et al. Phenomic analysis of the honey bee pathogen-web and its dynamics on colony productivity, health and social immunity behaviors.PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263273.

- Cunningham, S.A.; FitzGibbon, F.; Heard, T.A. The future of pollinators for Australian agriculture. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2002, 53, 893-900.

- Khalifa , S.A.; Elshafiey, E.H.; Shetaia, A.A.; El-Wahed, A.A.A.; Algethami, A.F.; Musharraf, S.G.; et al. Overview of bee pollination and its economic value for crop production. Insects 2021,12, 688.

- Rogers, S.R.; Tarpy, D.R.; Burrack, H.J. Bee species diversity enhances productivity and stability in a perennial crop. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97307.

- Gibbs, D.M.; Muirhead, I.F.; The Economic Value and Environmental Impact of the Australian Beekeeping Industry. A Report Prepared for the Australian Beekeeping Industry; Australian Beekeeping Industry: Canberra, Australia, 1998. Available online: https://honeybee.org.au/doc/Muirhead.doc (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Tierney, S.M.; Bernauer, O.M.; King, L.; Spooner-Hart, R.; Cook, J.M. Bee pollination services and the burden of biogeography.Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 290, 20230747.

- Allen, G. Honey bee health and pollination under protected and contained environments. Hort Innovation, 2022. Available online: https://www.horticulture.com.au (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Howpage, D. Pollination biology of kiwifruit: influence of honey bees, Apis mellifera L, pollen parents and pistil structure. PhD thesis, University of Western Sydney, Hawkesbury, Australia, 1999.Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Parveen, N.; Miglani, R.; Kumar, A.; Dewali, S.; Kumar, K.; Sharma, N.; et al. Honey bee pathogenesis posing threat to its global population: A short review.Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 2022, 88, 11–32.

- Milbrath, M. Honey bee bacterial diseases. Honey Bee Medicine for the Veterinary Practitioner. 2021,277-293.

- Büchler, R.; Costa, C.; Hatjina, F,.; Andonov, S.; Meixner, M.D.; Conte, Y.L.; et al. The influence of genetic origin and its interaction with environmental effects on the survival of Apis mellifera L. colonies in Europe. J. Apic. Res. 2014, 53, 205-214.

- Hedtke, S.M.; Blitzer, E.J.; Montgomery, G.A.; Danforth, B.N. Introduction of non-native pollinators can lead to trans-continental movement of bee-associated fungi. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130560.

- Salkova, D.; Shumkova, R.; Balkanska, R.; Palova, N.; Neov, B.; Radoslavov, G.; et al. Molecular detection of Nosema spp. in honey in Bulgaria. Vet. Sci. 2021, 9, 10.

- Aditya, Ira.; Purwanto, H. Molecular detection of the pathogen of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in honey in Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2023, 24.

- Ward, L.; Brown, M.; Neumann, P.; Wilkins, S.; Pettis, J.; Boonham, N. A DNA method for screening hive debris for the presence of small hive beetle (Aethina tumida). Apidologie. 2007, 38, 272-280.

- Ryba, S.; Titera, D.; Haklova, M.; Stopka, P. A PCR method of detecting American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae) in winter beehive wax debris. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 139, 193-196.

- Ribani , A.; Utzeri, V.J.; Taurisano, V.; Fontanesi, L. Honey as a source of environmental DNA for the detection and monitoring of honey bee pathogens and parasites. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 113.

- Bakonyi , T.; Derakhshifar, I.; Grabensteiner, E.; Nowotny, N. Development and evaluation of PCR assays for the detection of Paenibacillus larvae in honey samples: Comparison with isolation and biochemical characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1504-1510.

- Forsgren, E. European foulbrood in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S5-S9.

- Aziz, M.A.; Alam, S. Diseases of Honeybee (Apis mellifera). In Melittology—New Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024.

- Dong, J.; Olano, J.P.; McBride, J.W.; Walker, D.H. Emerging pathogens: challenges and successes of molecular diagnostics. J. Mol. Diagn. 2008, 10, 185–197.

- Ongus, J.R.; Fombong, A.T.; Irungu, J.; Masiga, D.; Raina, S. Prevalence of common honey bee pathogens at selected apiaries in Kenya, 2013/2014. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2018, 38, 58-70.

- Hamiduzzaman, M.M.; Guzman-Novoa, E.; Goodwin, P.H. A multiplex PCR assay to diagnose and quantify Nosema infections in honey bees (Apis mellifera). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 105,151-155.

- Bass, D.; Christison, K.W.; Stentiford, G.D.; Cook, L.S.; Hartikainen, H. Environmental DNA/RNA for pathogen and parasite detection, surveillance, and ecology. Trends Parasitol. 2023, 39, 285-304.

- D’Alessandro, B.; Antúnez, K.; Piccini, C.; Zunino, P. DNA extraction and PCR detection of Paenibacillus larvae spores from naturally contaminated honey and bees using spore-decoating and freeze-thawing techniques. World J. Microbiol. Biotech. 2007, 23, 593–597.

- Revainera, P.D.; Quintana, S.; de Landa, G.F.; Iza, C.G.; Olivera, E.; Fuentes, G.; et al. Molecular detection of bee pathogens in honey. J. Insects Food Feed, 2020, 6, 467-474.

- Traynor, K.S.; Pettis, J.S.; Tarpy, D.R.; Mullin, C.A.; Frazier, J.L.; Frazier, M.; et al. In-hive Pesticide Exposome: Assessing risks to migratory honey bees from in-hive pesticide contamination in the Eastern United States. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33207.

- Bovo, S.; Ribani, A.; Utzeri, V.J.; Schiavo, G.; Bertolini, F.; Fontanesi, L. Shotgun metagenomics of honey DNA: Evaluation of a methodological approach to describe a multi-kingdom honey bee derived environmental DNA signature. PLoS One, 2018, 13, e0205575.

- Soares, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Delerue-Matos, C. Towards DNA-based methods analysis for honey: an update. Molecules, 2023, 28, 2106.

- Call, D.R.; Borucki, M.K.; Loge, F.J. Detection of bacterial pathogens in environmental samples using DNA microarrays. J. Microbiol. Methods 2003, 53, 235–243.

- Bohmann, K.; Evans, A.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Carvalho, G.R.; Creer, S.; Knapp, M.; et al. Environmental DNA for wildlife biology and biodiversity monitoring.Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29,358-367.

- Silva, M.S.; Rabadzhiev, Y.; Eller, M.R.; Iliev, I.; Ivanova, I.; Santana, W.C. Microorganisms in honey. Honey analysis. IntechOpen 2017, 500, 233-257.

- Crooks, S. Australian Honeybee Industry Survey 2006-07. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. Canberra Australia Publication. 2008, 08-170.

- Waiblinger , H.-U.; Ohmenhaeuser, M,.; Meissner, S.; Schillinger, M.; Pietsch, K.; Goerlich, O.; et al. In-house and interlaboratory validation of a method for the extraction of DNA from pollen in honey. J. Verbraucherschutz Und Leb. 2012, 7, 243-254.

- Soares, S.; Amaral, J.S.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; Mafra, I. Improving DNA isolation from honey for the botanical origin identification. Food Control, 2015,48,130-136.

- Rathinasamy,V.; Hosking, C.; Tran, L.; Kelley, J.; Williamson, G.; Swan, J.; et al. Development of a multiplex quantitative PCR assay for detection and quantification of DNA from Fasciola hepatica and the intermediate snail host, Austropeplea tomentosa, in water samples. Vet. Parasitol. 2018,259,17-24.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2. Wiley interdiscip. Rev. comput. stat. 2011,3,180-185.

- Griffith, D.M.; Veech, J.A.; Marsh, C.J.; Cooccur: probabilistic species co-occurrence analysis in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2016,69,1-17.

- Veech, J.A. A probabilistic model for analysing species co-occurrence. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013,22,252-260.

- Utzeri , V.J.; Ribani, A.; Fontanesi, L. Authentication of honey based on a DNA method to differentiate Apis mellifera subspecies: Application to Sicilian honey bee (A. m. siciliana) and Iberian honey bee (A. m. iberiensis) honeys. Food Control. 2018, 91, 294-301.

- Chen, Y.; Evans, J.; Zhou, L.; Boncristiani, H.; Kimura, K.; Xiao, T.; et al. Asymmetrical coexistence of Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2009, 101, 204-209.

- Ribani A, A.; Taurisano, V.; Utzeri, V.J.; Fontanesi, L. Honey Environmental DNA Can Be Used to Detect and Monitor Honey Bee Pests: Development of Methods Useful to Identify Aethina tumida and Galleria mellonella Infestations. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 213-213.

- Garrido-Bailón, E.; Higes, M.; Martínez-Salvador, A.; Antúnez, K.; Botías, C.; Meana, A.; et al. The prevalence of the honeybee brood pathogens Ascosphaera apis, Paenibacillus larvae and Melissococcus plutonius in Spanish apiaries determined with a new multiplex PCR assay. Microb. biotechnol. 2013, 6, 731-739.

- Bovo, S.; Utzeri, V.J.; Ribani, A.; Cabbri, R.; Fontanesi, L. Shotgun sequencing of honey DNA can describe honey bee derived environmental signatures and the honey bee hologenome complexity. Sci. Rep. 2020,10,9279.

- Lauro, F.M.; Favaretto, M.; Covolo, L.; Rassu, M.; Bertoloni, G. Rapid detection of Paenibacillus larvae from honey and hive samples with a novel nested PCR protocol. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 81, 195–201.

- McKee, B.; Djordjevic, S.; Goodman, R.; Hornitzky, M. The detection of Melissococcus pluton in honey bees (Apis mellifera) and their products using a hemi-nested PCR. Apidologie 2003, 34, 19–27.

- Giersch, T.; Berg, T.; Galea, F.; Hornitzky, M. Nosema ceranae infects honey bees (Apis mellifera) and contaminates honey in Australia. Apidologie 2009, 40, 117–123.

- Granato, A.; Caldon, M.; Colamonico, R.; Boscarato, M.; Falcaro, C.; Stocco, N.; et al. 2009. Presented in Proceedings 41st Apimondia International Apicultural Congress, p. 163. Montpellier, France.

- Gisder, S.; Horchler, S.; Pieper, F.; Schüler, V.; Šima, P.; Genersch, E. Rapid Gastrointestinal Passage May Protect Bombus terrestris from ecoming a True Host for Nosema ceranae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00629-20.

- Holt, H.L.; Grozinger, C.M. Approaches and challenges to managing Nosema (Microspora: Nosematidae) parasites in honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 1487–1503.

- Friess, I.; Feng, F.; Da Silva, A.; Slemenda, S.B.; Pieniazek, N.J. Nosema ceranae n. sp. (Microspora, Nosematidae), morphological and molecular characterization of a microsporidian parasite of the Asian honey bee Apis cerana (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Eur. J. Protistol. 1996, 32, 356–365.

- Higes, M.; Martín, R.; Meana, A. Nosema ceranae, a new microsporidian parasite in honeybees in Europe. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2006,92,93-95.

- Klee, J.; Besana, A.M.; Genersch, E.; Gisder, S.; Nanetti, A.; Tam, D.Q.; Chinh, T.X.; Puerta, F.; Ruz, J.M.; Kryger, P.; et al. Widespread dispersal of the microsporidian Nosema ceranae, an emergent pathogen of the western honey bee, Apis mellifera. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2007, 96, 1–10.

- Fries, I. Nosema ceranae in European honey bees (Apis mellifera). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010,103,S73-S79.

- Gisder , S.; Schüler, V.; Horchler, L.L.; Groth, D.; Genersch, E. Long-Term Temporal Trends of Nosema spp. Infection Prevalence in Northeast Germany: Continuous Spread of Nosema ceranae, an Emerging Pathogen of Honey Bees (Apis mellifera), but No General Replacement of Nosema apis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 301.

- Martín-Hernández , R.; Bartolome, C.; Chejanovsky, N.; Le Conte, Y.; Dalmon, A.; Dussaubat, C.; Dussaubat, C.; Meana, A.; Pinto, M.; Soroker, V.; et al. Nosema ceranae in Apis mellifera: A 12 Years Post-Detection Perspective: Nosema ceranae in Apis mellifera. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 1302–1329.

- Goblirsch, M. Nosema ceranae disease of the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Apidologie 2018, 49, 131–150.

- Emsen, B.; Guzman-Novoa, E.; Hamiduzzaman, M.M.; Eccles, L.; Lacey, B.; Ruiz-Pérez, R.A.; Nasr, M. Higher prevalence and levels of Nosema ceranae than Nosema apis infections in Canadian honey bee colonies. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 175–181.

- Chen, Y.P.; Evans, J.D.; Smith, I.B.; Pettis, J.S. Nosema ceranae is a long-present and widespread microsporidean infection of the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) in the United States. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 97, 186–188.

- Deutsch, K.R.; Graham, J.R.; Boncristiani, H.F.; Bustamante, T.; Mortensen, A.N.; Schmehl, D.R.; et al. Widespread distribution of honey bee-associated pathogens in native bees and wasps: trends in pathogen prevalence and co-occurrence. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2023,200,107973.

- Guerrero-Molina, C.; Correa-Benítez, A.; Hamiduzzaman, M.M.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Nosema ceranae is an old resident of honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Mexico, causing infection levels of one million spores per bee or higher during summer and fall. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 141, 38–40.

- Papini, R.; Mancianti, F.; Canovai, R.; Cosci, F.; Rocchigiani, G.; Benelli, G.; Canale, A. Prevalence of the microsporidian Nosema ceranae in honeybee (Apis mellifera) apiaries in Central Italy. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 979–982.

- Cilia, G.; Flaminio, S.; Zavatta, L.; Ranalli, R.; Quaranta, M.; Bortolotti, L.; et al. Occurrence of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) pathogens in wild pollinators in northern Italy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022,12,907489.

- Bollan, K.A.; Hothersall, J.D.; Moffat, C.; Durkacz, J.; Saranzewa, N.; Wright, G.A.; Raine, N.E.; Highet, F.; Connolly, C.N. The microsporidian parasites Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis are widespread in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies across Scotland. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 751–759.

- Murray, Z.L.; Lester, P.J. Confirmation of Nosema ceranae in New Zealand and a phylogenetic comparison of Nosema spp. strains.J. Apic. Res. 2015,54,101-104.

- Frazer, J.L.; Tham, K-M.; Reid, M.; van Andel, M.; McFadden, A.M.; Forsgren, E.; et al. First detection of Nosema ceranae in New Zealand honey bees.J. Apic. Res. 2022,54,358-365.

- Waters, T.L. The distribution and population dynamics of the honey bee pathogens Crithidia mellificae and Lotmaria passim in New Zealand.PhD thesis, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington,1t January 2018. Available online: https://openaccess.wgtn.ac.nz/(accessed on 23rd November 2021).

- Huang, W-F.; Jiang, J-H.; Chen, Y-W.; Wang, C-H. A Nosema ceranae isolate from the honeybee Apis mellifera. Apidologie. 2007,38,30-37.

- Gisder, S.; Hedtke, K.; Möckel, N.; Frielitz, M-C.; Linde, A.; Genersch, E. Five-year cohort study of Nosema spp. in Germany: does climate shape virulence and assertiveness of Nosema ceranae?. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010,76,3032-3038.

- Forsgren, E.; Fries, I. Comparative virulence of Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis in individual European honey bees. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 170, 212–217.

- Fenoy, S.; Rueda, C.; Higes, M.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Del Aguila, C. High-level resistance of Nosema ceranae, a parasite of the honeybee, to temperature and desiccation.Appl. Environ. Microbiol . 2009,75,6886-6889.

- Chen, Y-W.; Chung, W-P.; Wang, C-H.; Solter, L.F.; Huang, W-F. Nosema ceranae infection intensity highly correlates with temperature.J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012,111,264-267.

- Cristian, M.A.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Mărghitaş la.; Moritz, R.F. Nosema apis and N. ceranae in Western honeybee (Apis mellifera)–geographical distribution and current methods of diagnosis. Bull. UASVM Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2011,68,1-2.

- Castagnino, G.L.B.; Mateos, A.; Meana, A.; Montejo, L.; Zamorano Iturralde, L.V.; Cutuli De Simón, M.T. Etiology, Symptoms and Prevention of Chalkbrood Disease: A Literature Review. Rev. Bras. De Saude E Prod. Anim. 2020, 21, e210332020.

- Wilson, W.T.; Nunamaker, R.A.; Maki, D. The occurrence of brood diseases and absence of the Varroa mite in honey bees from Mexico. Am. Bee J. 1984, 124, 51–53.

- Aronstein, K.A.; Murray, K.D. Chalkbrood disease in honey bees. J. invertebr. pathol. 2010,103,S20-S29.

- Paşca, C.; Mărghitaş, L.A.; Șonea, C.; Bobiş, O.; Buzura-Matei, I.A.; Dezmirean, D.S. A Review of Nosema cerane and Nosema apis: Characterization and Impact for Beekeeping. Bul. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 76, 77–87.

- Forsgren, E.; Locke, B.; Sircoulomb, F.; Schäfer, M.O. Bacterial Diseases in Honeybees. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2018, 5, 18–25.

- White, G.F. The Bacteria of the Apiary: With Special Reference to Bee Diseases; Technical Series; USDA, Bureau of Entomology: Washington, DC, USA, 1906; Volume 14, pp. 1–50GF.

- Ratnieks, F.L. American foulbrood: the spread and control of an important disease of the honey bee. Bee World. 1992,73,177-191.

- Lindström, A.; Korpela, S.; Fries, I. The distribution of PaeniBacillus larvae spores in adult bees and honey and larval mortality, following the addition of American foulbrood diseased brood or spore-contaminated honey in honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 99, 82–86.

- Otten, C. A general overview on AFB and EFB pathogen, way of infection, multiplication, clinical symptoms and outbreak. Apiacta 2003, 38, 106–113.

- Ricchiuti , L.; Rossi, F.; Del Matto, I.; Iannitto, G.; Del Riccio, A.L.; Petrone, D.; Ruberto, G.; Cersini, A.; Di Domenico, M.; Cammà, C. A study in the Abruzzo region on the presence of Paenibacillus larvae spores in honeys indicated underestimation of American foulbrood prevalence in Italy. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 416–419.

- Alburaki, M.; Abban, S.K.; Evans, J.D.; Chen, Y.P. Occurrence and distribution of two bacterial brood diseases (American and European foulbrood) in US honey bee colonies and resistance to antibiotics from 2015 to 2022. J. Apic. Res. 2024,1-10.

- Neumann, P.; Elzen, P.J. The biology of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae): Gaps in our knowledge of an invasive species. Apidologie. 2004,35,229-247.

- Neumann, P.; Ellis, J.D. The small hive beetle (Aethina tumida Murray, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae): Distribution, biology and control of an invasive species. J. Apic. Res. 2008, 47, 180–183.

- Ellis, J.D.; Hepburn, H.R. An ecological digest of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida), a symbiont in honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera). Insectes Sociaux 2006, 53, 8–19.

- Ellis, J.; Graham, J.; Mortensen, A. Standard methods for wax moth research. J. Apic. Res. 2013, 52, 1–17.

- Hosni, E.M.; Al-Khalaf, A.A.; Nasser, M.G.; Abou-Shaara, H.F.; Radwan, M.H. Modeling the Potential Global Distribution of Honeybee Pest, Galleria mellonella under Changing Climate. Insects 2022, 13, 484.

- Al Toufailia, H.; Alves, D.A.; De Bená, D.C.; Bento, J.M.S.; Iwanicki, N.S.A.; Cline, A.R.; Ellis, J.D.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. First record of small hive beetle, Aethina tumida Murray, in South America. J. Apic. Res. 2017, 56, 76–80.

- Lundie , A.E. The Small Hive Beetle Aethina Tumida; Department of Agriculture Forestry, Government Printer: Pretoria, South Africa, 1940.

- Thomas, M. Florida pest alert-the small hive beetle. Am. Bee J.1998,138: 565.

- Somerville, D. Study of the small hive beetle in the USA: a report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. NSW Agriculture, Goulburn, Australia.2003.

- Strauss, U.; Human, H.; Gauthier, L.; Crewe, R.M.; Dietemann, V.; Pirk, C.W.W. Seasonal prevalence of pathogens and parasites in the savannah honeybee (Apis mellifera scutellata). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2013, 114, 45–52.

- Lawal, A.; Oyerinde, A.; Asala, S.; Anjorin, T. The incidence and management of pest affecting honeybees in Nigeria. Global Journal of Bio-science and Biotechnology. 2020,9,40-44.

- Jamal , Z.A.; Abou-Shaara, H.F.; Qamer, S.; Alhumaidi Alotaibi, M.; Ali Khan, K.; Fiaz Khan, M.; Amjad Bashir, M.; Hannan, A.; AL-Kahtani, S.N.; Taha, E.-K.A.; et al. Future Expansion of Small Hive Beetles, Aethina Tumida, towards North Africa and South Europe Based on Temperature Factors Using Maximum Entropy Algorithm. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101242.

- Bernier, M.; Fournier, V.; Giovenazzo, P. Pupal Development of Aethina tumida (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) in Thermo-Hygrometric Soil Conditions Encountered in Temperate Climates. J. Econ. Entomol. 2014, 107, 531–537.

- Aglagane, A.; Carra, E.; Ravaioli, V.; Er-Rguibi, O.; Santo, E.; Mouden, E.H.E.; et al. Molecular examination of nosemosis and foulbrood pathogens in honey bee populations from southeastern Morocco. Apidologie. 2023,54:42.

- de León-Door, A.P.; Pérez-Ordóñez, G.; Romo-Chacón, A.; Rios-Velasco, C.; Órnelas-Paz, J.D.J.; Zamudio-Flores, P.B.; Acosta-Muñiz, C.H. Pathogenesis, epidemiology and variants of Melissococcus plutonius (ex White), the causal agent of European foulbrood. J. Apic. Sci. 2020, 64, 173–188.

- Forsgren, E.; Lundhagen, A.C.; Imdorf, A.; Fries, I. Distribution of Melissococcus plutonius in honeybee colonies with and without symptoms of European foulbrood. Microbiol. Ecol. 2005,50,369-374.

- Asif Aziz, M.; Alam, S. Diseases of honeybee (Apis Mellifera). In Melittology—New Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024.

- Sturtevant, A.P. Mixed infection in the brood diseases of bees. J. Econ. Entomol. 1921,14,127-134.

- Stephan, J.G.; de Miranda, J.R.; Forsgren, E. American foulbrood in a honeybee colony: Spore-symptom relationship and feedbacks between disease and colony development. BMC Ecol. 2020, 20, 16.

- Ongus, J.R.; Irungu, J.; Raina, S. Correlation between Pest Abundance and Prevalence of Honeybee Pathogens at Selected Apiaries in Kenya, 2013/2014. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017,7, 2225-0948. 109. Schäfer, M.O.; Ritter, W.; Pettis.;Neumann, P. Small hive beetles, Aethina tumida, are vectors of Paenibacillus larvae. Apidologie. 2010;41:14-20.

- Özkırım , A.; Schiesser, A.; Keskin, N. Dynamics of Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae co-infection seasonally in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies. J. Apic. Sci. 2019, 63, 41–48.

- Milbrath , M.O.; van Tran, T.; Huang, W.F.; Solter, L.F.; Tarpy, D.R.; Lawrence, F.; Huang, Z.Y. Comparative virulence and competition between Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae in honey bees (Apis mellifera). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 125, 9–15.

- Martín-Hernández, R.; Botías, C.; Bailón, E.G.; Martínez-Salvador, A.; Prieto, L.; Meana, A.; Higes, M. Microsporidia infecting Apis mellifera: Coexistence or competition. Is Nosema ceranae replacing Nosema apis?. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 2127–2138.

| State | No. of samples | Samples positive for P. larvae | % of positive samples | Samples positive for M. plutonius | % of positive samples |

| Victoria | 27 | 9 | 33% | 10 | 37% |

| New South Wales | 29 | 8 | 28% | 4 | 14% |

| Queensland | 24 | 5 | 21% | 3 | 13% |

| Northern Territory | 1 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| West Australia | 22 | 3 | 14% | 0 | 0% |

| South Australia | 14 | 0 | 0% | 4 | 29% |

| Kangaroo Island* | 6 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Tasmania | 12 | 3 | 25% | 3 | 25% |

| Total | 135 | 28 | 21% | 24 | 18% |

| State | No. of samples | Samples positive for A. apis | % of positive samples | Samples positive for N. apis | % of positive samples | Samples positive for N. ceranae | % of positive samples |

| Victoria | 27 | 1 | 4% | 5 | 19% | 19 | 70% |

| New South Wales | 29 | 2 | 7% | 3 | 10% | 17 | 59% |

| Queensland | 24 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 14 | 58% |

| NorthernTerritory | 1 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 100% |

| West Australia | 22 | 0 | 0% | 5 | 23% | 10 | 45% |

| South Australia | 14 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 14% | 9 | 64% |

| Kangaroo Island* | 6 | 0 | 0% | 3 | 50% | 1 | 17% |

| Tasmania | 12 | 4 | 33% | 7 | 58% | 6 | 50% |

| Total | 135 | 7 | 5.% | 25 | 19% | 77 | 57% |

| State | No. of samples | Samples positive for A. tumida | % of positive samples | Samples positive for G. mellonella | % of positive samples |

| Victoria | 27 | 15 | 56% | 12 | 44% |

| New South Wales | 29 | 9 | 31% | 3 | 10% |

| Queensland | 24 | 17 | 71% | 6 | 25% |

| Northern Territory | 1 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| West Australia | 22 | 1 | 5% | 10 | 45% |

| South Australia | 14 | 8 | 57% | 8 | 57% |

| Kangaroo Island* | 6 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Tasmania | 12 | 4 | 33% | 10 | 83% |

| Total | 135 | 54 | 40% | 49 | 37% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).