Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Trehalose Structure, Biosynthesis, and Protective Molecular Mechanisms

2.1. Structure and Properties

2.2. Biosynthesis and Hydrolysis

2.3. Molecular Mechanisms of Trehalose/T6P’s Protective Role

3. Functions of Trehalose and Its Metabolites

3.1. Regulation of Crop Growth, Development, and Carbohydrate Metabolism

3.2. Trehalose/T6P Induces Other High Sugar Levels, Serving as an Energy and Carbon Source

3.2.1. Induction of the Expression of Stress-Responsive Genes

3.2.2. Upregulation of Antioxidant Systems to Scavenge ROS

3.3. Trehalose/T6P as a Signaling Molecule and Crosstalk with Sugars and Hormones

Induction of Ion Homeostasis, Accumulation of Osmolytes, and Secondary Metabolites

3.4. Trehalose as a Macromolecular Protector

4. Genetic Engineering of Trehalose-Encoding Genes (TPS and TPP)

5. Trehalose Exogenous Application

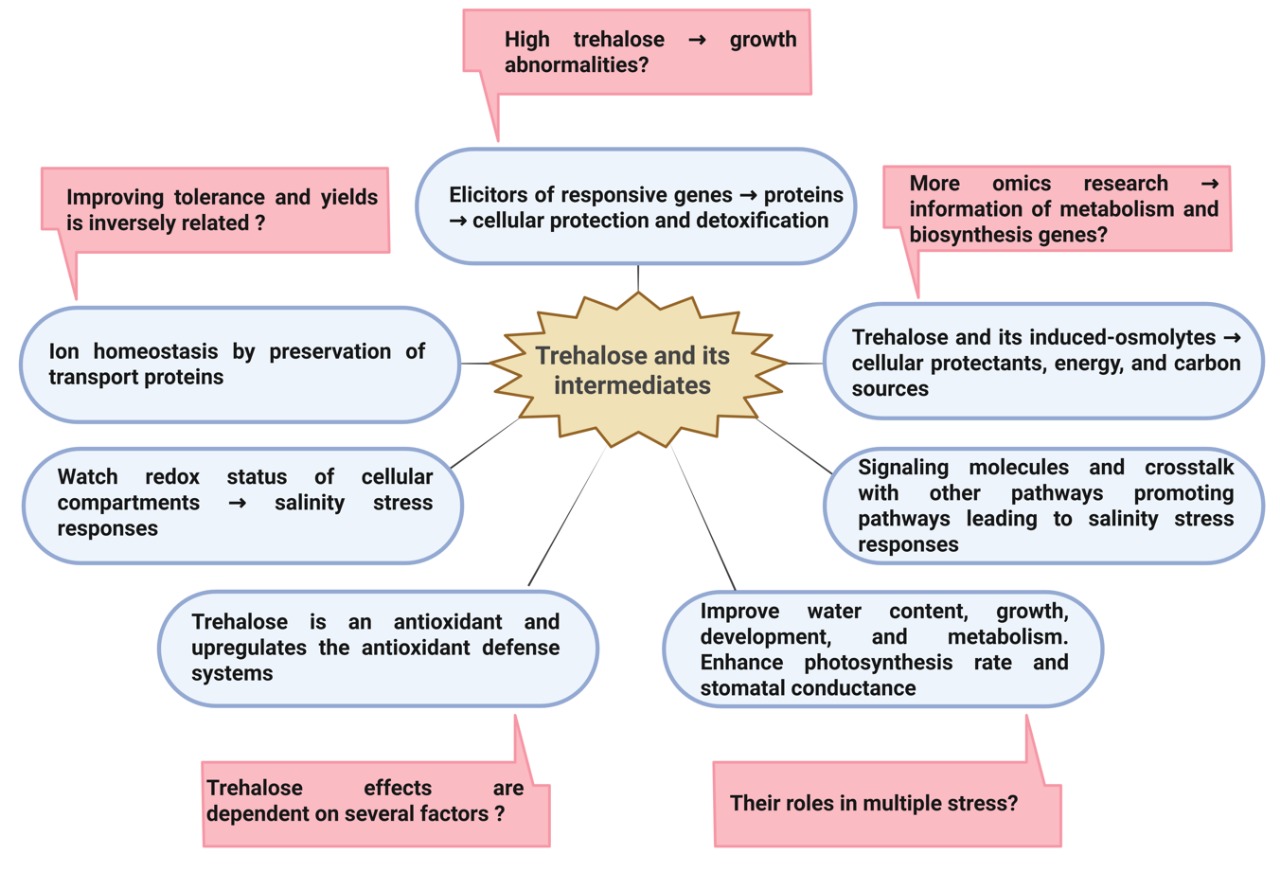

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO (2015) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and ITPS, Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils Status of the world’s soil resources (SWSR), main report.

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Raihan, R.H.; Masud, A.A.C.; Rahman, K.; Nowroz, F.; Rahman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesawat, M.S.; Satheesh, N.; Kherawat, B.S.; Kumar, A.; Kim, H.-U.; Chung, S.-M.; Kumar, M. Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species during Salt Stress in Plants and Their Crosstalk with Other Signaling Molecules—Current Perspectives and Future Directions. Plants 2023, 12, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of Salinity Tolerance in Plants: Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Characterization. Int. J. Genom. 2014, 2014, 701596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.A.; Sarkhosh, A.; Khan, N.; Balal, R.M.; Ali, S.; Rossi, L.; Gómez, C.; Mattson, N.; Nasim, W.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Insights into the Physiological and Biochemical Impacts of Salt Stress on Plant Growth and Development. Agronomy 2020, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, K.; Mondal, S.; Gorai, S.; Singh, A.P.; Kumari, A.; Ghosh, T.; Roy, A.; Hembram, S.; Gaikwad, D.J.; Mondal, S.; et al. Impacts of salinity stress on crop plants: improving salt tolerance through genetic and molecular dissection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1241736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsha SG, Geetha GA, Manjugouda IP, Shilpashree VM, GuheA, Singh TH, Laxman RH, Satisha GC, Prathibha MD, Shivashankara KS (2025) Unraveling salinity stress tolerance: Contrasting morpho-physiological, biochemical, and ionic responses in diverse brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) genotypes. Plant Physiol Biochem 222:109666.

- Mansour MMF, Salama KHA (2019) Cellular mechanisms of plant salt tolerance. In: Giri B, Varma A (eds) Microorganisms in Saline Environment: Strategies and Functions, Springer, Switzerland, pp 169-210.

- Zhang H, Zhu J, Gong Z, Zhu J Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nature Rev Genet 2022, 23, 104–119. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.M.F. Anthocyanins: Biotechnological targets for enhancing crop tolerance to salinity stress. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.K.; Sadhukhan, S. Imperative role of trehalose metabolism and trehalose-6-phosphate signaling on salt stress responses in plants. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.A. Review: Trehalose and its role in plant adaptation to salinity stress. Plant Sci. 2025, 357, 112533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eh, T.-J.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Li, J.; Lei, P.; Ji, X.; Kim, H.-I.; Zhao, X.; Meng, F. The role of trehalose metabolism in plant stress tolerance. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 76, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liang, A.; Xu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Li, M.; Liu, T.; Qi, H. Versatile roles of trehalose in plant growth and development and responses to abiotic stress. Veg. Res. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goharrizi, K.; Karami, S.; Hamblin, M.; Momeni, M.; Basaki, T.; Dehnavi, M.; Nazari, M. Transcriptomic and proteomic profile approaches toward drought and salinity stresses. Biol. Plant. 2022, 66, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, F.; Ling, J.; Zhang, C. New Genes Identified as Modulating Salt Tolerance in Maize Seedlings Using the Combination of Transcriptome Analysis and BSA. Plants 2023, 12, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, M.; Herrera-Cervera, J.A.; Lluch, C.; Tejera, N.A. Trehalose metabolism in root nodules of the model legume Lotus japonicus in response to salt stress. Physiol. Plant. 2006, 128, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grennan, A.K. The Role of Trehalose Biosynthesis in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturriaga, G.; Suárez, R.; Nova-Franco, B. Trehalose Metabolism: From Osmoprotection to Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 3793–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, F.; Chen, J.; Finnegan, P.M.; Younis, A.; Nafees, M.; Zorrig, W.; Ben Hamed, K. Application of Trehalose and Salicylic Acid Mitigates Drought Stress in Sweet Basil and Improves Plant Growth. Plants 2021, 10, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, L.; Ding, D.; Bakpa, E.P.; Xie, J. Trehalose Alleviated Salt Stress in Tomato by Regulating ROS Metabolism, Photosynthesis, Osmolyte Synthesis, and Trehalose Metabolic Pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 772948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, C.; Niu, T.; Bakpa, E.P. Trehalose alleviates salt tolerance by improving photosynthetic performance and maintaining mineral ion homeostasis in tomato plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 974507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, M.; Gao, Y.; Luo, Y. Exogenous trehalose differently improves photosynthetic carbon assimilation capacities in maize and wheat under heat stress. J. Plant Interactions 2022, 17, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbler, S.M.; Armijos-Jaramillo, V.; Lunn, J.E.; Vicente, R. The trehalose 6-phosphate phosphatase family in plants. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e14096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Mohammad, F.; Khan, M.N.; Corpas, F.J. Trehalose mitigates sodium chloride toxicity by improving ion homeostasis, membrane stability, and antioxidant defense system in Indian mustard. Plant Stress 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorge, I.; Janiak, M.; Carpentier, S.; Van Dijck, P. Fine tuning of trehalose biosynthesis and hydrolysis as novel tools for the generation of abiotic stress tolerant plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsin, S.M.; Fardus, J.; Nagata, A.; Tamano, N.; Mitani, H.; Fujita, M. Comparative Study of Trehalose and Trehalose 6-Phosphate to Improve Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms in Wheat and Mustard Seedlings under Salt and Water Deficit Stresses. Stresses 2022, 2, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofa, M.G.; Hossain, M.A.; Fujita, M. Trehalose pretreatment induces salt tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings: oxidative damage and co-induction of antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Protoplasma 2014, 252, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.M.-S.; El Sebai, T.N.; Ramadan, A.A.E.-M.; El-Bassiouny, H.M.S. Physiological and biochemical role of proline, trehalose, and compost on enhancing salinity tolerance of quinoa plant. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid A, Shahbaz M Influence of exogenously applied trehalose on morphological and physiological traits of flax (Linum usitissimum) plant under water shortage conditions. Pak J Bot 2022, 59, 435–448.

- Joshi, R.; Sahoo, K.K.; Singh, A.K.; Anwar, K.; Pundir, P.; Gautam, R.K.; Krishnamurthy, S.L.; Sopory, S.K.; Pareek, A.; Singla-Pareek, S.L. Enhancing trehalose biosynthesis improves yield potential in marker-free transgenic rice under drought, saline, and sodic conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 71, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.; Tiwari, N.; Bharadwaj, C.; Roorkiwal, M.; Reddy, S.P.P.; Patil, B.S.; Kumar, S.; Hamwieh, A.; Vinutha, T.; Bindra, S.; et al. A comprehensive analysis of Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) gene for salinity tolerance in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, M.; Zhu, T.; He, H.; Ke, J.; You, C.; Wu, L. Exogenous Trehalose can Reduce the Loss of Rice Yields Under High Temperature Stress at the Flowering Stage by Improving the Carbohydrate Metabolism and Photosynthesis Capacity of Flag Leaves. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 44, 2892–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, A.; Kodigudla, A.; Raman, D.R.; Bakka, K.; Challabathula, D. Trehalose accumulation enhances drought tolerance by modulating photosynthesis and ROS-antioxidant balance in drought sensitive and tolerant rice cultivars. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2023, 29, 2035–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.J.; Jhurreea, D.; Zhang, Y.; Primavesi, L.F.; Delatte, T.; Schluepmann, H.; Wingler, A. Up-regulation of biosynthetic processes associated with growth by trehalose 6-phosphate. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maicas, S.; Guirao-Abad, J.P.; Argüelles, J.-C. Yeast trehalases: Two enzymes, one catalytic mission. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 2249–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.-G.; Wang, H.-J.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Cui, S.-Y. Invertebrate Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase Gene: Genetic Architecture, Biochemistry, Physiological Function, and Potential Applications. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.L.; Nick, F.; Adhitama, N.; Fields, P.D.; Stillman, J.H.; Kato, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Ebert, D. Trehalose mediates salinity-stress tolerance in natural populations of a freshwater crustacean. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, 4160–4169.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha-um S, Rai V, Takabe T (2019) Proline, glycinebetaine, and trehalose uptake and inter-organ transport in plants under stress. In: Hossain MA, Kumar V, Burritt D, Fujita M, Makela PS (eds) Osmoprotectant-Mediated Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants, Springer Nature, Switzerland, pp 201-223.

- Feng, Y.; Chen, X.; He, Y.; Kou, X.; Xue, Z. Effects of Exogenous Trehalose on the Metabolism of Sugar and Abscisic Acid in Tomato Seedlings Under Salt Stress. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2019, 25, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John R, Raja V, Ahmad M, Majeed U, Ahmad S, Yaqoob U, Kaul T (2017) Trehalose: metabolism and role in stress signaling in plants. In: Sarwat M, Ahmad A, Abdin MZ, Ibrahim MM (eds) Stress Signaling in Plants: Genomics and Proteomics Perspective, Volume 2, Springer, Switzerland, pp 261-275.

- Figueroa, C.M.; Lunn, J.E. A Tale of Two Sugars: Trehalose 6-Phosphate and Sucrose. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbein, A.D.; Pan, Y.T.; Pastuszak, I.; Carroll, D. New insights on trehalose: A multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 17R–27R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.C.M.; Hejazi, M.; Fettke, J.; Steup, M.; Feil, R.; Krause, U.; Arrivault, S.; Vosloh, D.; Figueroa, C.M.; Ivakov, A.; et al. Feedback Inhibition of Starch Degradation in Arabidopsis Leaves Mediated by Trehalose 6-Phosphate. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 1142–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Bhardwaj, S.; Rahman, A.; García-Caparrós, P.; Habib, M.; Saeed, F.; Charagh, S.; Foyer, C.H.; Siddique, K.H.; Varshney, R.K. Trehalose: A sugar molecule involved in temperature stress management in plants. Crop. J. 2024, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Hassan, M.U.; Chattha, M.U.; Mahmood, A.; Shah, A.N.; Hashem, M.; Alamri, S.; Batool, M.; Rasheed, A.; Thabit, M.A.; et al. Trehalose: a promising osmo-protectant against salinity stress—physiological and molecular mechanisms and future prospective. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 11255–11271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.U.; Nawaz, M.; Shah, A.N.; Raza, A.; Barbanti, L.; Skalicky, M.; Hashem, M.; Brestic, M.; Pandey, S.; Alamri, S.; et al. Trehalose: A Key Player in Plant Growth Regulation and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 42, 4935–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan CHB, Van Dijck P (2019) Biosynthesis and degradation of trehalose and its potential to control plant growth, development, and (a)biotic stress tolerance. In: Hossain MA, Kumar V, Burritt D, Fujita M, Makela PS (eds) Osmoprotectant-Mediated Abiotic Stress Tolerance, Springer Nature, Switzerland, pp 175-199.

- Wang W, Chen Q, Xu S, Liu W, Zhu X, Song C (2020a) Trehalose--6--phosphate phosphatase E modulates ABA--controlled root growth and stomatal movement in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol 62, 1518–1534. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Xu, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Ma, D.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zheng, H. Trehalose along with ABA promotes the salt tolerance of Avicennia marina by regulating Na+ transport. Plant J. 2024, 119, 2349–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasensky, J.; Broyart, C.; Rabanal, F.A.; Jonak, C. The Redox-Sensitive Chloroplast Trehalose-6-Phosphate Phosphatase AtTPPD Regulates Salt Stress Tolerance. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avonce, N.; Mendoza-Vargas, A.; Morett, E.; Iturriaga, G. Insights on the evolution of trehalose biosynthesis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006, 6, 109–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul S, Paul S Trehalose induced modifications in the solvation pattern of N-methylacetamide. J Phys Chem B 2014, 118, 1052–1063. [CrossRef]

- Bezrukavnikov, S.; Mashaghi, A.; van Wijk, R.J.; Gu, C.; Yang, L.J.; Gao, Y.Q.; Tans, S.J. Trehalose facilitates DNA melting: a single-molecule optical tweezers study. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 7269–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosar, F.; Akram, N.A.; Sadiq, M.; Al-Qurainy, F.; Ashraf, M. Trehalose: A Key Organic Osmolyte Effectively Involved in Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 38, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, J.H.; Crowe, L.M.; Chapman, D. Preservation of Membranes in Anhydrobiotic Organisms: The Role of Trehalose. Science 1984, 223, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgenblum, G.I.; Sapir, L.; Harries, D. Properties of Aqueous Trehalose Mixtures: Glass Transition and Hydrogen Bonding. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.K.; Kim, J.-K.; Owens, T.G.; Ranwala, A.P.; Choi, Y.D.; Kochian, L.V.; Wu, R.J. Trehalose accumulation in rice plants confers high tolerance levels to different abiotic stresses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 15898–15903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordachescu M, Imai R (2011) Trehalose and abiotic stress in biological systems. In: Shanker A (ed) Abiotic Stress in Plants – Mechanisms and Adaptations, In Tech Open, Croatia, pp 215-234.

- Abdallah, M.-S.; Abdelgawad, Z.; El-Bassiouny, H. Alleviation of the adverse effects of salinity stress using trehalose in two rice varieties. South Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 103, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-P.; Zheng, P.-H.; Zhang, X.-X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.-T.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Xu, J.-R.; Cao, Y.-L.; Xian, J.-A.; Wang, A.-L.; et al. Effects of dietary trehalose on growth, trehalose content, non-specific immunity, gene expression and desiccation resistance of juvenile red claw crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2021, 119, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Tong, R.; Ye, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J.; Gan, Y. Engineered Rhizobia with Trehalose-Producing Genes Enhance Peanut Growth Under Salinity Stress. Agronomy 2025, 15, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.A.; Mansour, M.M.F. Hydrogen sulfide priming enhanced salinity tolerance in sunflower by modulating ion hemostasis, cellular redox balance, and gene expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah SK, Kaur G, Wani SH (2016) Metabolic engineering of compatible solute trehalose for abiotic stress tolerance in plants. In: Iqbal N, Nazar R, Khan NA (eds) Osmolytes and Plants Acclimation to Changing Environment: Emerging Omics Technologies, Springer, India, pp 83-96.

- Roychoudhury A (2021) Trehalose in osmotic stress tolerance of plants. Bioingene PSJ 2:1-13.

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, M.; Gao, Y.; Luo, Y. Exogenous trehalose differently improves photosynthetic carbon assimilation capacities in maize and wheat under heat stress. J. Plant Interactions 2022, 17, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Kapoor N, Dhiman S, Kour J, Singh A, Sharma A, Bhardwaj R (2023) Role of sugars in regulating physiological and molecular aspects of plants under abiotic stress. In: Sharma A, Pandey S, Bhardwaj R, Zheng B, Tripathi DK (eds) The Role of Growth Regulators and Phytohormones in Overcoming Environmental Stress, Academic Press, London, pp 355-374.

- Bao, M.; Xi, Y.; Wang, R.; Ma, Y.; Bai, M.; Wei, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, L. Trehalose signaling regulates metabolites associated with the quality of rose flowers under drought stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, H.; Paul, M.; Zu, Y.; Tang, Z. Exogenous trehalose largely alleviates ionic unbalance, ROS burst, and PCD occurrence induced by high salinity in Arabidopsis seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 570–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bánfalvi Z )2019(Transgenic plants overexpressing trehalose biosynthetic genes and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. In: Hossain MA, Kumar V, Burritt D, Fujita M, Makela PS (eds) Osmoprotectant-Mediated Abiotic Stress Tolerance, Springer Nature, Switzerland, pp 225-239.

- Onwe, R.O.; Onwosi, C.O.; Ezugworie, F.N.; Ekwealor, C.C.; Okonkwo, C.C. Microbial trehalose boosts the ecological fitness of biocontrol agents, the viability of probiotics during long-term storage and plants tolerance to environmental-driven abiotic stress. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 806, 150432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordil B, Khan N (2022) Trehalose treatment alleviates salt toxicity in wheat seedlings: a beneficial research attempt in agriculture sector of Pakistan. Hamdard Medicus 65:34-50.

- Chang, B.; Yang, L.; Cong, W.; Zu, Y.; Tang, Z. The improved resistance to high salinity induced by trehalose is associated with ionic regulation and osmotic adjustment in Catharanthus roseus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnu, J.; Wahl, V.; Schmid, M. Trehalose-6-Phosphate: Connecting Plant Metabolism and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2011, 2, 15488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanford, J.; Zhai, Z.; Baer, M.D.; Guo, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Raugei, S.; Shanklin, J. Molecular mechanism of trehalose 6-phosphate inhibition of the plant metabolic sensor kinase SnRK1. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn0895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, C.; Bledsoe, S.W.; Griffiths, C.A.; Kollman, A.; Paul, M.J.; Sakr, S.; Lagrimini, L.M. Differential Role for Trehalose Metabolism in Salt-Stressed Maize. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman M, Sevim G, Bor M (2019) The role of proline, glycinebetaine, and trehalose in stress-responsive gene expression. In: Hossain MA, Kumar V, Burritt D, Fujita M, Makela PS (eds) Osmoprotectant-Mediated Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants, Springer, Switzerland, pp 241-256.

- Nuccio, M.L.; Wu, J.; Mowers, R.; Zhou, H.-P.; Meghji, M.; Primavesi, L.F.; Paul, M.J.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Haque, E.; et al. Expression of trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase in maize ears improves yield in well-watered and drought conditions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatte, T.L.; Sedijani, P.; Kondou, Y.; Matsui, M.; de Jong, G.J.; Somsen, G.W.; Wiese-Klinkenberg, A.; Primavesi, L.F.; Paul, M.J.; Schluepmann, H. Growth Arrest by Trehalose-6-Phosphate: An Astonishing Case of Primary Metabolite Control over Growth by Way of the SnRK1 Signaling Pathway. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Li, C.; Che, P.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Feng, L.; Liu, X.; Liao, W. Hydrogen Gas Enhanced Seed Germination by Increasing Trehalose Biosynthesis in Cucumber. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 42, 3908–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nounjan, N.; Theerakulpisut, P. Effects of exogenous proline and trehalose on physiological responses in rice seedlings during salt-stress and after recovery. Plant, Soil Environ. 2012, 58, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redillas, M.C.F.R.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Jeong, J.S.; Jung, H.; Bang, S.W.; Hahn, T.-R.; Kim, J.-K. Accumulation of trehalose increases soluble sugar contents in rice plants conferring tolerance to drought and salt stress. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2011, 6, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichaiya, T.; Faiyue, B.; Rotarayanont, S.; Uthaibutra, J.; Saengnil, K. Exogenous trehalose alleviates chilling injury of ‘Kim Ju’ guava by modulating soluble sugar and energy metabolisms. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichaiya, T.; Intarasit, S.; Umnajkitikorn, K.; Jangsutthivorawat, S.; Saengnil, K. Postharvest trehalose application alleviates chilling injuring of cold storage guava through upregulation of SnRK1 and energy charge. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarek A, Sadak M, Dawood MG (2017) Improving drought tolerance of quinoa plant by foliar treatment of trehalose. Agric Eng Int: CIGR Journal Special issue 245-25.

- Bharti A, Maheshwari HS, Chourasiya D, Prakash A, Sharma MP (2022) Role of trehalose in plant–rhizobia interaction and induced abiotic stress tolerance. In: Sigh HB, Vaishnav A (eds) New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering - Sustainable Agriculture: Revisiting Green Chemical, Elsevier, London, pp 245-263.

- Sadak, M.S. Physiological role of trehalose on enhancing salinity tolerance of wheat plant. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae H, Herman E, Baily B, Sicher R Exogenous trehalose alters Arabidopsis transcripts involved in cell wall modification, abiotic stress, nitrogen metabolism, and plant defense. Physiol Plant 2005, 125, 114–126. [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.; Herman, E.; Sicher, R. Exogenous trehalose promotes non-structural carbohydrate accumulation and induces chemical detoxification and stress response proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana grown in liquid culture. Plant Sci. 2005, 168, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhai, H.; Wang, F.-B.; Zhou, H.-N.; Si, Z.-Z.; He, S.-Z.; Liu, Q.-C. Cloning and Characterization of a Salt Tolerance-Associated Gene Encoding Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase in Sweetpotato. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-W.; Zang, B.-S.; Deng, X.-W.; Wang, X.-P. Overexpression of the trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene OsTPS1 enhances abiotic stress tolerance in rice. Planta 2011, 234, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hathout TA, Samia M, Zinab A, Said E, Al Mokadem A (2015) Using validamycin A for salinity stress mitigation in two rice varieties differing in their salt tolerance level. Egypt J Bot 37:49-68.

- Luo, Y.; Li, W.-M.; Wang, W. Trehalose: Protector of antioxidant enzymes or reactive oxygen species scavenger under heat stress? Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Shao, X. NMR revealed that trehalose enhances sucrose accumulation and alleviates chilling injury in peach fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, M.; Islam, R.; Monsur, M.B.; Amiruzzaman, M.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Trehalose Protects Maize Plants from Salt Stress and Phosphorus Deficiency. Plants 2019, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, P.; Sheen, J. Sugar and hormone connections. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.A.; Abdellatif, Y.M. Effect of maltose and trehalose on growth, yield and some biochemical components of wheat plant under water stress. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2016, 61, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, J.E.; Delorge, I.; Figueroa, C.M.; Van Dijck, P.; Stitt, M. Trehalose metabolism in plants. Plant J. 2014, 79, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debast, S.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Hajirezaei, M.R.; Hofmann, J.; Sonnewald, U.; Fernie, A.R.; Börnke, F. Altering Trehalose-6-Phosphate Content in Transgenic Potato Tubers Affects Tuber Growth and Alters Responsiveness to Hormones during Sprouting. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1754–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.B.; Engler, J.; Iyer, S.; Gerats, T.; Van Montagu, M.; Caplan, A.B. Effects of Osmoprotectants upon NaCl Stress in Rice. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Mohammad, F. Modulation of growth, photosynthetic efficiency, leaf biochemistry, cell viability and yield of Indian mustard by the application of trehalose. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Mohammad, F.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Kalaji, H.M. Salicylic acid and trehalose attenuate salt toxicity in Brassica juncea L. by activating the stress defense mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 326, 121467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazù, S.; Migliardo, F.; Benedetto, A.; La Torre, R.; Hennet, L. Bio-protective effects of homologous disaccharides on biological macromolecules. Eur. Biophys. J. 2011, 41, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.M.F.; Ali, E.F. Evaluation of proline functions in saline conditions. Phytochemistry 2017, 140, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczyńska-Wiśnik, D.; Stojowska-Swędrzyńska, K.; Laskowska, E. Intracellular Protective Functions and Therapeutical Potential of Trehalose. Molecules 2024, 29, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeid IM Trehalose as osmoprotectant for maize under salinity-induced stress. Res J Agri Biol Sci 2009, 5, 613–622.

- Ye, N.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Duan, M.; Liu, L. Abscisic Acid Enhances Trehalose Content via OsTPP3 to Improve Salt Tolerance in Rice Seedlings. Plants 2023, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Z.; Yang, B.-P.; Feng, C.-L.; Tang, H.-L. Genetic Transformation of Tobacco with the Trehalose Synthase Gene from Grifola frondosa Fr. Enhances the Resistance to Drought and Salt in Tobacco. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2005, 47, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgawad ZA, Hathout TA, El-Khallal SM, Said EM, Al-Mokadem AZ (2014) Accumulation of trehalose mediates salt adaptation in rice seedlings. American-Eurasian J Agri Environ Sci 14:1450-1463.

- Jun, S.-S.; Yang, J.Y.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, N.-R.; Park, M.C.; Hong, Y.-N. Altered physiology in trehalose-producing transgenic tobacco plants: Enhanced tolerance to drought and salinity stresses. J. Plant Biol. 2005, 48, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lei, X.; Lü, J.; Gao, C. Overexpression of the ThTPS gene enhanced salt and osmotic stress tolerance in Tamarix hispida. J. For. Res. 2020, 33, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, C.; Culiáñez-Macià, F.A. Tomato abiotic stress enhanced tolerance by trehalose biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2005, 169, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.-F.; Chao, D.-Y.; Shi, M.; Zhu, M.-Z.; Gao, J.-P.; Lin, H.-X. Overexpression of the trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase gene OsTPP1 confers stress tolerance in rice and results in the activation of stress responsive genes. Planta 2008, 228, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Jun, S.-S.; An, G.; Hong, Y.-N.; Park, M.C. A comparative study on the protective role of trehalose and LEA proteins against abiotic stresses in transgenic Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris) overexpressingCaLEA orotsA. J. Plant Biol. 2003, 46, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.M.; Villalobos, E.; Araújo, S.S.; Leyman, B.; Van Dijck, P.; Alfaro-Cardoso, L.; Fevereiro, P.S.; Torné, J.M.; Santos, D.M. Transformation of tobacco with an Arabidopsis thaliana gene involved in trehalose biosynthesis increases tolerance to several abiotic stresses. Euphytica 2005, 146, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.A.; Avonce, N.; Suárez, R.; Thevelein, J.M.; Van Dijck, P.; Iturriaga, G. A bifunctional TPS–TPP enzyme from yeast confers tolerance to multiple and extreme abiotic-stress conditions in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta 2007, 226, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Li, Q.; Weng, M.; Wang, X.; Guo, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Duan, D.; Wang, B. Cloning of TPS gene from eelgrass species Zostera marina and its functional identification by genetic transformation in rice. Gene 2013, 531, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishal B, Krishnamurthy P, Ramamoorthy R, Kumar PP OsTPS8 controls yield-related traits and confers salt stress tolerance in rice by enhancing suberin deposition. New Phytol 2019, 221, 1369–1386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.O.; Kato, H.; Shima, S.; Tezuka, D.; Matsui, H.; Imai, R. Functional identification of a rice trehalase gene involved in salt stress tolerance. Gene 2019, 685, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, I.-C.; Oh, S.-J.; Seo, J.-S.; Choi, W.-B.; Song, S.I.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Seo, H.-S.; Choi, Y.D.; Nahm, B.H.; et al. Expression of a Bifunctional Fusion of the Escherichia coli Genes for Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase and Trehalose-6-Phosphate Phosphatase in Transgenic Rice Plants Increases Trehalose Accumulation and Abiotic Stress Tolerance without Stunting Growth. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, R.; Calderón, C.; Iturriaga, G. Enhanced Tolerance to Multiple Abiotic Stresses in Transgenic Alfalfa Accumulating Trehalose. Crop. Sci. 2009, 49, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chu, D.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Du, L.; Du, Y.; Du, J.; et al. Genome- and transcriptome-wide identification of trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatases (TPP) gene family and their expression patterns under abiotic stress and exogenous trehalose in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Zewany RGS, Al-Semmak QHA (2017) Effect of foliar-applied trehalose on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under salt stress condition. Karbala J Agri Sci 4:1-18.

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Lawlor, D.W.; Paul, M.J.; Pan, W. Exogenous trehalose improves growth under limiting nitrogen through upregulation of nitrogen metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed HI, Akladious S, El-Beltagi H Mitigation the harmful effect of salt stress on physiological, biochemical and anatomical traits by foliar spray with trehalose on wheat cultivars. Fresenius Environ Bull 2018, 27, 7054–7065.

- Soares, F.A.; Na Chiangmai, P.; Duangkaew, P.; Pootaeng-On, Y. ; Nurhidayati Exogenous trehalose application in rice to mitigate saline stress at the tillering stage. Pesqui. Agropecu. Trop. 2023, 53, e75695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerakulpisut P, Gunnula W Exogenous sorbitol and trehalose mitigated salt stress damage in salt-sensitive but not salt-tolerant rice seedlings. Asian J Crop Sci 2012, 4, 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Alhudhaibi, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.A.R.; Abd-Elaziz, S.M.S.; Farag, H.R.M.; Elsayed, S.M.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Hossain, A.S.; Alharbi, B.M.; Haouala, F.; Elkelish, A.; et al. Enhancing salt stress tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings: insights from trehalose and mannitol. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.J.; Gonzalez-Uriarte, A.; Griffiths, C.A.; Hassani-Pak, K. The Role of Trehalose 6-Phosphate in Crop Yield and Resilience. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Origin | Transgenic crop | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPS | Oryza sativa | Oryza sativa | TPS gene was constitutively expressed in the leaves of two rice cultivars, contrasting in salinity tolerance, under stressed and non-stressed conditions, treated and untreated with validamycin A (a competitive inhibitor of trehalase enzyme). Higher transcript amounts were obtained in the presence of validamycin A. Salinity tolerant cultivar showed increased TPS transcript amounts relative to the sensitive one. Upregulation of TPS led to trehalose accumulation and increased gene expression that is responsible for producing osmoprotectants, because trehalose was too low to serve as an osmoprotectant. The study also revealed that the TPS expression pattern was consistent with the increase in TPS activity, confirming that the expression of the TPS gene was upregulated in response to salinity and validamycin treatments, and evidenced its important role in crop salinity tolerance. | [109] |

| TPS, TPP | Solanum Lycopersicon | Solanum Lycopersicon | Salinity upregulated the expression of TPS in tomato, and exogenous trehalose increased the endogenous trehalose, which caused a negative feedback regulation and suppressed the TPP expression. The study indicated that TPS, TPP, and trehalose exhibited differential expressions under salinity stress. The result suggests that the trehalose metabolic pathway could directly affect the salinity tolerance of crop plants. | [40] |

| otsA, otsB | Escherichia coli | Oryza sativa | Overexpression of these genes resulted in transgenic lines exhibiting sustained plant growth, increased trehalose, high soluble sugars, less oxidative damage, elevated capacity for photosynthesis, and ion homeostasis relative to wild type under salinity stress. The study argued against the primary role of trehalose as a compatible solute, as a low level of trehalose was obtained in transgenic rice plants. The work revealed that engineering crops for the overproduction of trehalose resulted in improved salinity tolerance and productivity. | [58] |

| AmTPS9A | Avicennia marina | Arabidopsis thaliana | AmTPS9A-overexpressing Arabidopsis showed increased salinity tolerance by upregulating the expression of genes encoding ion transporters that mediate Na+ efflux from the roots of transgenic Arabidopsis under NaCl treatments. | [50] |

| TPS (otsA) | Escherichia coli | Nicotiana tabacum | Transgenic plants produced small amounts of trehalose, maintained leaf turgidity and fresh weight, had more efficient seed germination, and showed a drastic delay in leaf withering and chlorosis under 250 mM NaCl. It appears that trehalose did not participate in osmotic adjustment but rather may have had a protective or signaling role. | [110] |

| TPS | Tamarix hispida | Tamarix hispida | ThTPS overexpression was induced by salinity treatment, which promoted the biosynthesis of trehalose, decreased the accumulation of O2− and H2O2, and thus improved the T. hispida salinity resistance, suggestive of enhancing the antioxidant defense system by trehalose under salinity. | [111] |

| TPSP | Escherichia coli | Oryza sativa | TPSP transgenic plants retained higher yield, RWC, chlorophyll content, trehalose content, K+/Na+ ratio, stomatal conductance, efficient photosynthesis, and rice seed nutritional levels compared with the wild type under salinity imposition. This finding confirms that trehalose acts as a signaling molecule that alters other metabolic switches, resulting in significant changes in the levels of other tolerance traits in transgenic plants, which support salinity tolerance under stress conditions. | [31] |

| TPS (TSase) | Grifola frondosa | Nicotiana tabaccum | Transgene tobacco showed increased trehalose, high water content, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant enzyme activities, enhanced salinity tolerance with obvious morphological changes but no growth inhibition. | [108] |

| AtTPPD | Arabidopsis thaliana | Arabidopsis thaliana | Plants overexpressing AtTPPD (its product enzyme AtTPPD is chloroplast-localized) produced high levels of starch and soluble sugars, which contributed to salinity tolerance. The result suggests that trehalose metabolism possibly regulates various biological processes by relaying the redox status of different cellular compartments. Also, under salinity stress, the transcript levels of the chloroplastic AtTPPD were highly increased, while tppd mutants were hypersensitive, indicative of the trehalose protective role of the thylakoid membranes when accumulated in the chloroplasts under salinity stress | [51] |

| IbTPS | Ipomoea batatas | Nicotiana tabaccum | Transgenic tobacco overexpressing the IbTPS gene resulted in significantly higher salinity tolerance, trehalose, and proline content than wild type under high salinity. Several stress tolerance-responsive genes were upregulated, suggesting that the IbTPS gene may enhance salinity tolerance by increasing the level of trehalose and proline and modulating the expression of stress tolerance-related genes. | [90] |

| TPS1 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Lycopersicon esculentum | TPS1 transgenic tomato plants displayed morphological changes such as thick shoots, rigid dark-green leaves, erect branches, and aberrant root development. The transgenic TPS1 tomato had leaves with high chlorophyll and starch contents. The study revealed that engineering tomato through trehalose biosynthesis showed increased salinity tolerance and yield in the presence and absence of stress. | [112] |

| TPS3 | Oryza sativa | Oryza sativa | ABA and salinity imposition upregulate OsTPP3 overexpression, which elevates trehalose content and improves salinity tolerance in rice seedlings. The work also revealed that the knockout of OsTPP3 reduced rice salinity tolerance associated with a decline in trehalose level. Trehalose application enhanced the salinity tolerance of the tpp3 mutant plant, indicating trehalose’s crucial role in improving crop salinity tolerance. | [107] |

| OsTPS1 | Oryza sativa | Oryza sativa | Overexpression of OsTPS1 improved the resilience of rice seedlings to salinity stress by elevating the content of trehalose and proline and upregulating stress-related genes under saline conditions relative to the wild type. | [91] |

| Ubi1: TPSP | Oryza sativa | Oryza sativa | Overexpression of Ubi1: TPSP induced a significant increase in endogenous trehalose and soluble sugars in transgenic rice and improved its salinity resistance to 150 mM NaCl. | [82] |

| OsTPP1 | Oryza sativa | Oryza sativa | OsTPP1 expression was upregulated under salinity, and its overexpression enhanced seed germination and trehalose levels, triggered stress-responsive genes, and upregulated the expression of OsTPS1, which contributed to rice salinity tolerance. The study indicates the potential use of OsTPP1 in the salinity stress engineering of crops of other crops. | [113] |

| otsA (TPS) | E. ctdi | Brassica campestris | Overexpression of OtsA in Chinese cabbage resulted in transgenic plants showing retained turgidity and photosynthesis rate, delayed necrosis, and remarkably improved salinity tolerance, but exhibited altered phenotypes, including stunted growth and aberrant root development relative to wildtype when subjected to 250 mM NaCl stress. | [114] |

| AtTPS1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Nicotiana tabacum | Transgenic seeds germinated in different NaCl concentrations, scoring salinity tolerance compared with untransformed plants, confirming that AtTPS1 overexpressing lines stimulated crop tolerance to NaCl stress. | [115] |

| TPS1, TPS2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Arabidopsis thaliana | Lines overexpressing the TPS1-TPS2 construct accumulated trehalose and exhibited a significant increase in salinity resilience with no morphological or growth alterations, while plants overexpressing the TPS1 alone exhibited modified growth, color, and shape. TPS1-TPS2 overexpressing lines were insensitive to glucose, confirming the proposed role of trehalose/T6P in modulating sugar sensing and carbohydrate metabolism. | [116] |

| ZmTPS | Zostera marina | Oryza sativa | Transgenic rice plants overexpressing ZmTPS showed increased endogenous trehalose and tolerance to 150 mM NaCl relative to untransformed control plants. Transgenic plants had no phenotypic aberrations. The work also illustrated that the transformed ZmTPS gene can be transmitted stably from the parent to the progeny in transgenic rice. | [117] |

| OsTPS8 | Oryza sativa | Oryza sativa | Constitutive overexpression of OsTPS8 enhanced soluble sugars and regulated the expression of genes involved in ABA signaling via SAPK9 regulation, which promoted suberin deposition in the root and reduced Na+ content in the shoot and root; this, in turn, improved salinity tolerance and grain yield in rice with no aberrant changes in plant growth and development under saline stress compared with the wild type. | [118] |

| OsTRE1 | Oryza sativa | Oryza sativa | Overexpressing the trehalase gene, OsTRE1, exhibited considerable increases in trehalase activity and remarkable declines in trehalose levels under 150 mM NaCl, with little change in the levels of other soluble sugars. Transgenic plants exhibited enhanced salinity resilience with no morphological alterations or growth defects, suggesting the involvement of OsTRE1 in salinity tolerance in rice. Trehalose accumulation appears not to be a prerequisite for better adaptation to salinity stress, but rather possibly the endogenous trehalose biosynthesis pathway. | [119] |

| otsA (Ubi1: TPSP) | Escherichia coli | Oryza sativa | Transgenic rice produced by the transformation of a gene encoding a bifunctional fusion (TPSP) of TPS and TPP of Escherichia coli elevated trehalose levels in the leaves and seeds, reduced the accumulation of potentially deleterious T6P, displayed no growth inhibition or visible morphological alterations, and enhanced tolerance to salinity stress. | [120] |

| TPS, TPP | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Medicago sativa | When both genes (TPS, TPP) were fused and expressed, transgenic alfalfa plants displayed improved growth, biomass production, and a significant increase in salinity tolerance. TPS-TPP fusion protein is promising for crop salinity tolerance and enhanced yield under saline conditions. | [121] |

| otsA (TPS) | Mesorhizobium sp. CCBAU25338 | Arachis hypogaea | Overexpression of trehalose synthesis genes otsA in the peanut-nodulating rhizobium Mesorhizobium sp. CCBAU25338 enhanced the salinity stress tolerance and nitrogen-fixing capacity of the rhizobium strain, as well as increased endogenous trehalose, agronomic traits, and lowered oxidative damage in peanuts under salinity conditions. | [62] |

| GmTPP | Glycine max | Glycine max | The expression levels of GmTPPs were upregulated under saline-alkali stress in soybean and were tissue-specific (i.e., flowers, stems, roots, nodules, shoots, leaves, pods, and seeds), suggestive of triggering developmental processes and stress responses that confer stress resilience. | [122] |

| Crop species | Mode of application | Trehalose concentration (mM) | Response | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oryza sativa | Seed priming | 0, 25 | Alleviated the harmful effects of salinity stress, increased soluble sugars and proline contents contributing to osmotic adjustment, and elevated internal trehalose, stimulating the antioxidant enzyme activities in two rice varieties under salinity imposition. | [60] |

| Chenopodium quinoa Masr 1 | Foliar spray | 0, 2.5, 5 | Growth, total soluble sugars, proline, free amino acids, photosynthetic pigments, yield attributes, antioxidant enzyme activities, and seed nutritional value were improved in quinoa plants by trehalose foliar spray under salinity stress, more so when compost was added to the soil. | [29] |

| Triticum aestivum | Foliar spray | 0, 5, 10, 15 (mg L-1) | Trehalose foliar spray stimulated growth parameters, trehalose content, proline content, and antioxidant enzyme activities in response to salinity imposition; these effects were more pronounced with 15 mg L-1. | [123] |

| Avicennia marina | Added to the Hoagland solution | 0, 20 | Exogenous trehalose enhanced salt resilience by increasing Na+ efflux from the leaf salt gland and root, which reduces the Na+ content in the root and leaf. | [50] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Added to liquid cultures | 0, 30 | Levels of trehalose, sucrose, and starch were elevated in response to trehalose treatment. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis identified nine altered proteins, four of which were responsible for detoxification or stress responses. This work indicates that the external supply of trehalose acted as a regulator of genes involved in responses to abiotic stresses. As exogenous trehalose altered transcript levels of several processes related to tolerance mechanisms, we suggest that trehalose, or metabolites derived from its biosynthesis pathway, are key modulators of gene expression in higher plants under stress. | [88,89] |

| Catharanthus roseus | Added to the nutrient solution | 0, 10, 30, 50 | Supplement of trehalose to the nutrient solution markedly alleviated the inhibitory effects of salinity on plant growth, relative water content, and photosynthetic rate by decreasing Na+, increasing K+, soluble sugars, free amino acids, and leaf gas exchange in leaves under 250 mM NaCl. The regulatory role of exogenous trehalose in stimulating salinity tolerance was optimal with 10 mM, while higher concentrations adversely affected plant growth. It appears that exogenous trehalose acted as a signal to induce the salinity-stressed plants to efficiently raise internal compatible solutes to regulate water loss and turgidity, leaf gas exchange, and ion homeostasis under salinity. | [73] |

| Solanum Lycopersicon | Added to the nutrient solution | 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 10 | Exogenous trehalose increased growth characteristics, chlorophyll content, proline, internal trehalose, and antioxidant enzyme activities, while decreasing lipid peroxidation, which effectively enhanced tomato salinity tolerance in response to 200 mM NaCl stress. The study also showed that the starch content declined and soluble sugars elevated as trehalose modulated the gene expression of starch and soluble sugar metabolism, induced the upregulation of sugar transporter genes, and those related to the synthesis and metabolism of ABA. It is obvious that trehalose’s role in regulating the above processes significantly modulates sugar accumulation, content, and distribution, thereby improving plant stress resilience. Notably, 2 mM provided optimal responses, and higher concentrations showed decreased responses. | [40] |

| Triticum aestivum | Added to a growth medium | 0, 10, 50 | Trehalose supply significantly stimulated several growth parameters of ten wheat varieties under 150 mM NaCl stress. | [72] |

| Brassica juncea | Foliar spray | 0, 10 | Leaf-applied trehalose increased salinity tolerance and yield by enhancing ion homeostasis, photosynthesis efficiency, antioxidant defense mechanisms, chlorophyll content, osmolyte accumulation, stomatal aperture, cell viability, and ROS scavenging under salinity stress. | [25] |

| Solanum Lycopersicon | Foliar spray | 0, 5, 10, 25 | Trehalose application scavenges ROS by enhancing the activities of antioxidant enzymes and their related gene expression, improves growth, biomass production, proline, and glycine betaine content, increases K+ and K+/Na+ ratio, upregulates the expression of trehalose genes (SlTPS1, SlTPS5, SlTPS7, SlTPPJ, SlTPPH, and SlTRE), and the activity of enzymes involved in its metabolic pathway, which in turn altogether stimulated tomato salinity tolerance. Trehalose at 10 mM was the best mitigation concentration, while 25 mM caused leaf damage and adversely affected plant growth under salinity. | [21] |

| Solanum Lycopersicon | Foliar spray | 0, 10 | Trehalose foliar supply improves photosynthetic efficiency, increases the activity of Calvin cycle enzymes, upregulates the expression of their related genes, protects the photosynthetic electron transport system, affects the expressions of SlSOS1, SlNHX, SlHKT1.1, SlVHA, and SlHA-A, which retain ion homeostasis, induces stomatal opening, and alleviates salt-induced damage to the chloroplast membrane and structure under salinity. The study shows that trehalose renders salinity tolerance by upregulating the processes involved in mitigating salinity toxicity. | [22] |

| Zea mays | Added to the nutrient solution | 0, 10 | Trehalose application improved the performance of two maize genotypes in response to 150 mM NaCl by decreasing the Na+/K+ ratio, ROS, lipid peroxidation, methylglyoxal, and increasing leaf trehalose, salinity tolerance, indicative of regulating antioxidant and glyoxalase systems as well as ion homeostasis. | [95] |

| Triticum aestivum | Foliar spray | 0, 10, 50 | Trehalose enhanced wheat growth and accumulation of compatible solutes (i.e., glucose, sucrose, trehalose, phenolic compounds, total soluble sugars) but decreased lipid peroxidation, hydrogen peroxide, and lipoxygenase activity of salinity-stressed wheat plants. It seems that antioxidant compounds and compatible osmolytes play a crucial role in enhancing wheat performance under salinity by counteracting oxidative damage and, hence, protecting cellular structures. | [87] |

| Cucumis sativus | Added to the nutrient solution | 0, 0.05, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1% | Hydrogen-induced cucumber seed germination was done by enhancing enzyme activity and gene expression levels of trehalose metabolism-related genes, which in turn increased the endogenous trehalose content. Although the molecular mechanism and hydrogen crosstalk with other signaling molecules in inducing seed germination are not clear, this work provides new insights concerning the roles and interactions of hydrogen and trehalose during seed germination and confirms one of the fundamental trehalose roles. That is, trehalose as a key regulator of carbon metabolism, largely influences plant growth and development. | [80] |

| Brassica juncea | Foliar spray | 0, 10, 20, 30 | Under the nonsaline condition, trehalose application improved Indian mustard growth characteristics and yield by enhancing osmolyte accumulation and their enzymes’ activities, hence reducing the ROS content, while promoting the content of photosynthetic pigments, gas exchange, mineral acquisition, and root cell viability. These improvements were more pronounced by 10 mM, while other trehalose concentrations were either equally or less effective. | [101] |

| Brassica juncea | Foliar spray | 0, 10 | Foliar spraying of trehalose improved the enzymatic antioxidant activities, compatible solute content, water status, and membrane permeability while decreasing ROS production, lipid peroxidation, and Na+ levels under salinity stress. These effects resulted in improved Indian mustard growth, ion homeostasis, photosynthesis, yield, and salinity resilience. | [102] |

| Oryza sativa | Added to the nutrient solution | 0, 10 | Trehalose protects rice seedlings against NaCl stress by increasing the level of internal trehalose, which effectively reduces ROS accumulation, elevates nonenzymatic antioxidants, and co-activates the antioxidative and glyoxalase systems. | [28] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Added to the nutrient solution | 0, 0.5, 1, 5 | Trehalose improved Arabidopsis salinity tolerance by retaining K+ content and a high K+/Na+ ratio, decreasing Na+ level, enhancing internal soluble sugars, and the activities of antioxidant enzymes in plant tissues under NaCl imposition. Thus, it is evident that trehalose regulates plant redox state and ionic distribution under high salinity. Trehalose at 1 mM showed the best salinity tolerance responses. | [69] |

| Triticum aestivum | Plant spray | 0, 10 | Trehalose promoted the growth parameters, yield, leaf anatomical features, endogenous trehalose, amino acid, sugar, total carbohydrate, and total soluble protein contents in 4 wheat cultivars contrasting in their salinity tolerance under 200 mM NaCl. | [125] |

| Oryza sativa | Added to the nutrient solution | 0, 10 | Trehalose supplement to 200 mM NaCl-stressed rice cultivars, contrasting in salinity resilience, did not mitigate the growth reduction during stress, while during recovery plants previously supplied with trehalose displayed a significantly higher growth recovery compared with plants that received only NaCl treatment. This mitigative effect was due to reduced Na+/K+ ratio and H2O2 level, and enhanced ascorbate peroxidase activity. The impact was more pronounced in the salinity-sensitive cultivar. | [81] |

| Oryza sativa | Foliar spray at the tillering stage | 0, 50, 100, 150 | Trehalose enhanced RWC, chlorophyll, soluble sugars, reproductive tillers per plant, grains per panicle, 100-grain weight, percentage of filled grains per panicle, and grain yield per plant in the salt-tolerant variety relative to other varieties. | [126] |

| Oryza sativa | Added to a growth culture | 0, 1, 5, 10 | Application of low trehalose concentrations (up to 5 mM) significantly decreased Na+ accumulation, overcame the growth inhibition, and enhanced the expression of the salT gene, while higher concentrations (10 mM) preserved the root integrity, prevented the chlorophyll damage in leaf blades, and suppressed the expression of the NaCl-induced salT gene. Interestingly, trehalose did not prevent salt accumulation in plant cells but did reduce Na+ accumulation in laminae. It is clear that trehalose protects cellular structure under salinity, but the observed differences in response and between low and high trehalose concentrations might reflect different modes of action at various concentrations, as well as differences in the accumulation or catabolism of trehalose in different parts of the plant. | [100] |

| Rosa rugosa | Foliar spray | 50 μM T6P, 20 mM trehalose |

Exogenous trehalose or T6P improved the drought tolerance of rose plants by alleviating the injurious impact of drought stress, maintaining the rose flower quality, T6P and trehalose accumulation, adjusting the carbohydrate distribution, and altering the synthesis of secondary metabolites (geraniol, total flavonoids, and total anthocyanins). Foliar application of trehalose or T6P also promoted the contents of starch, soluble sugar, and lignin in the petals, pointing to the role of T6P or trehalose as a positive regulatory signal participating in enhancing the rose plant’s resilience to drought stress. | [68] |

| Oryza sativa | Added to a growth culture | 0, 5, 10 | Exogenously supplied trehalose stimulated the growth and alleviated the harsh effects of salinity stress by reducing H2O2 and lipid peroxidation in the sensitive cultivar. However, trehalose did not have any beneficial effect on the growth of the salinity-tolerant cultivar, indicative of trehalose’s protective roles in the salt-sensitive cultivar but not in the salt-tolerant one. Although the study did not determine the endogenous trehalose content, we assume that salinity tolerant cultivar might have sufficient trehalose as well as other tolerance traits, and thus exogenous trehalose showed no beneficial impact on this cultivar. | [127] |

| Oryza sativa | Foliar spray | 0, 0.5% | Trehalose improved the salinity resilience of rice seedlings by increasing the antioxidant enzyme activities under 100 mM NaCl treatment. The study also demonstrated that salinity-induced ABA escalated the expression of OsTPP3, resulting in elevated endogenous trehalose, which stimulated the rice salinity tolerance to NaCl stress. | [107] |

| Zea mays | Seed priming | 0, 10 | Trehalose alleviated the adverse impacts of high salinity on metabolic activity (Hill-reaction activity, photosynthetic pigments, and nucleic acids content), increased sugars, soluble proteins, and proline contents, leaf K+/Na+ ratio, the growth and salinity tolerance, while decreasing electrolyte leakage and lipid peroxidation of the root cells, and salinity expression detected by leaf protein banding patterns of salinity-stressed maize seedlings. It seems that trehalose upregulated various salinity stress-responsive genes that contribute to the tolerance mechanisms of maize seedlings under salinity stress. | [106] |

| Triticum aestivum | Seed presoaking | 0, 10 | Seed presoaking with trehalose improved the salinity tolerance of wheat seedlings by reducing lipid peroxidation, elevating osmotic adjustment osmolytes such as amino acids (especially proline), reducing sugars, and total soluble sugars, and improving the enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants in wheat seedlings. This leads to maintaining the balance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants like phenols, flavonoids, proline, and soluble sugars. It is noteworthy that trehalose was more effective than mannitol. | [128] |

| Glycine max | Added to a growth culture | 10 μmol/L | Trehalose treatment upregulated the expression of TPP genes, and increased the carbohydrate and trehalose levels, while declining ROS content and thus mitigated the adverse impacts caused by saline-alkaline stress, especially in the saline-alkali-tolerant genotype. | [122] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).