Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

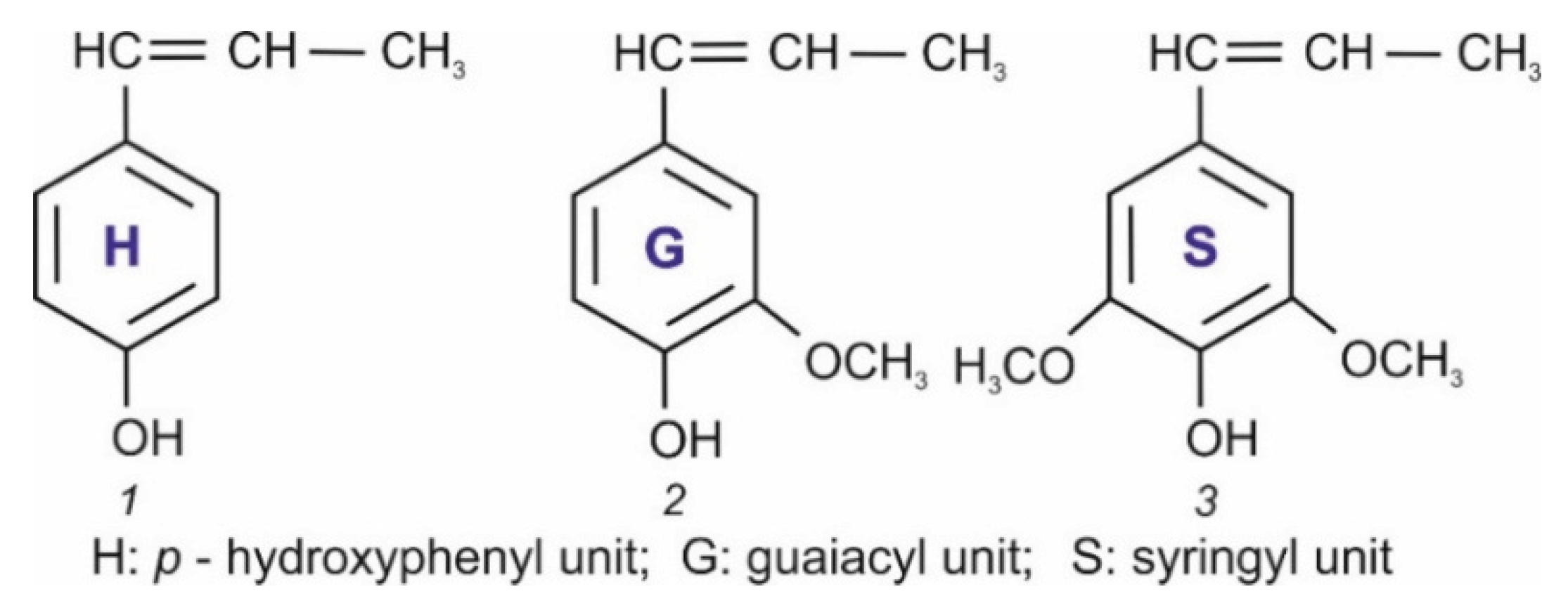

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

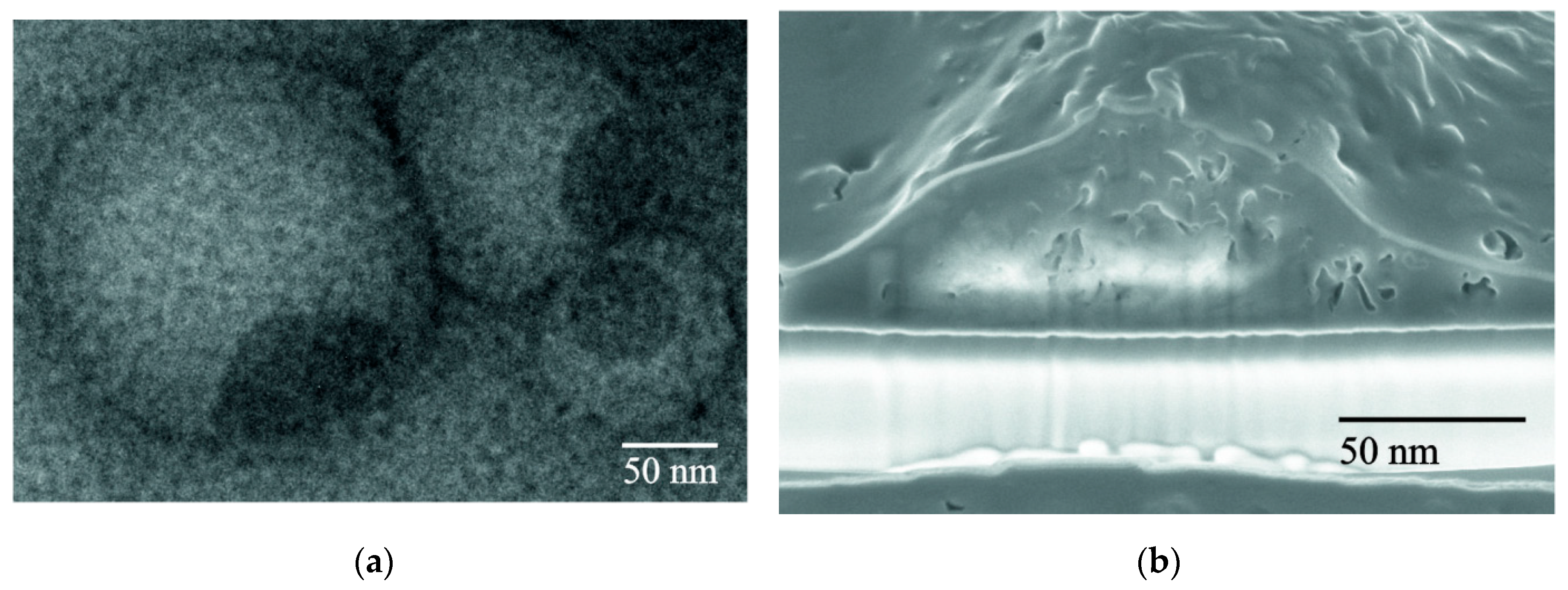

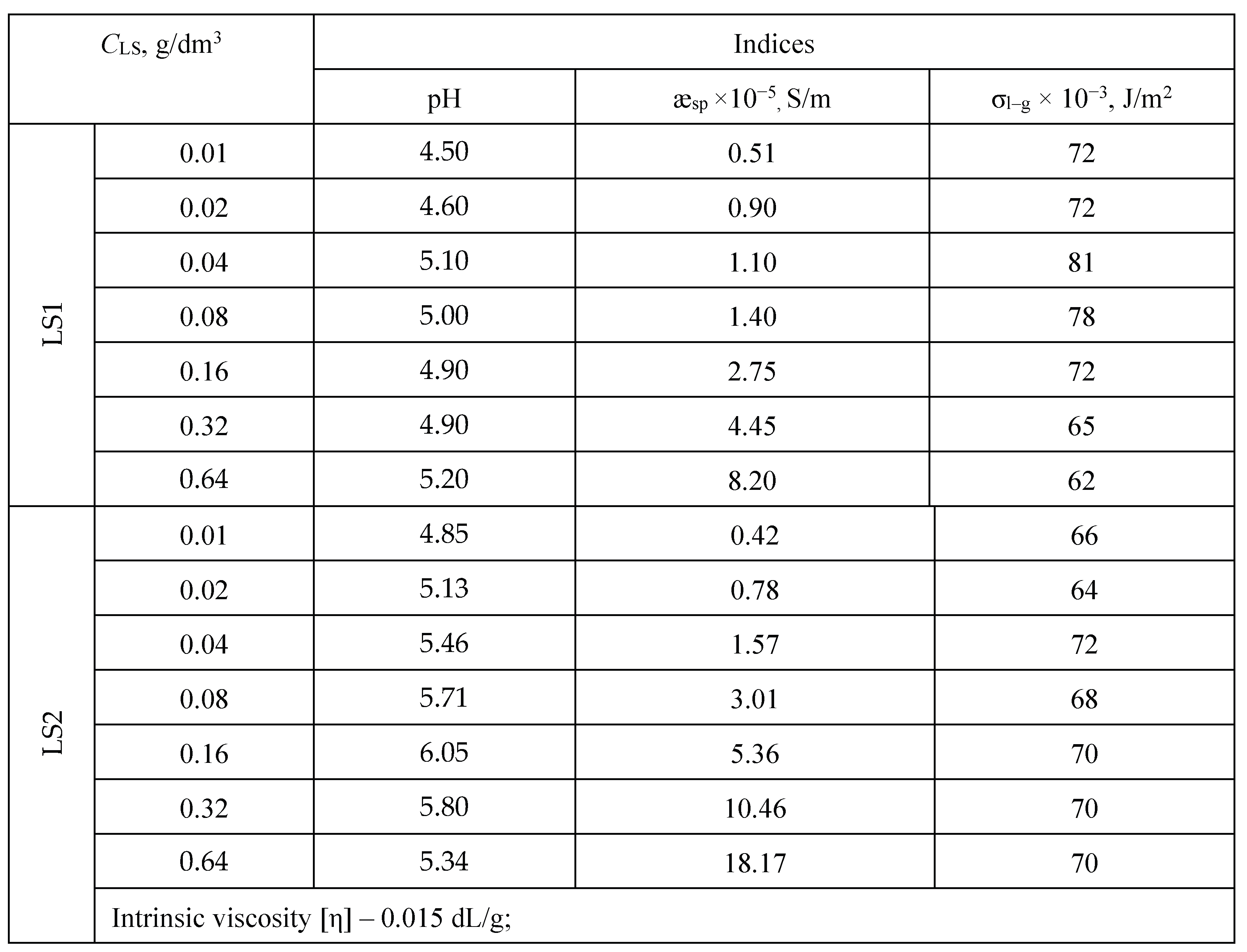

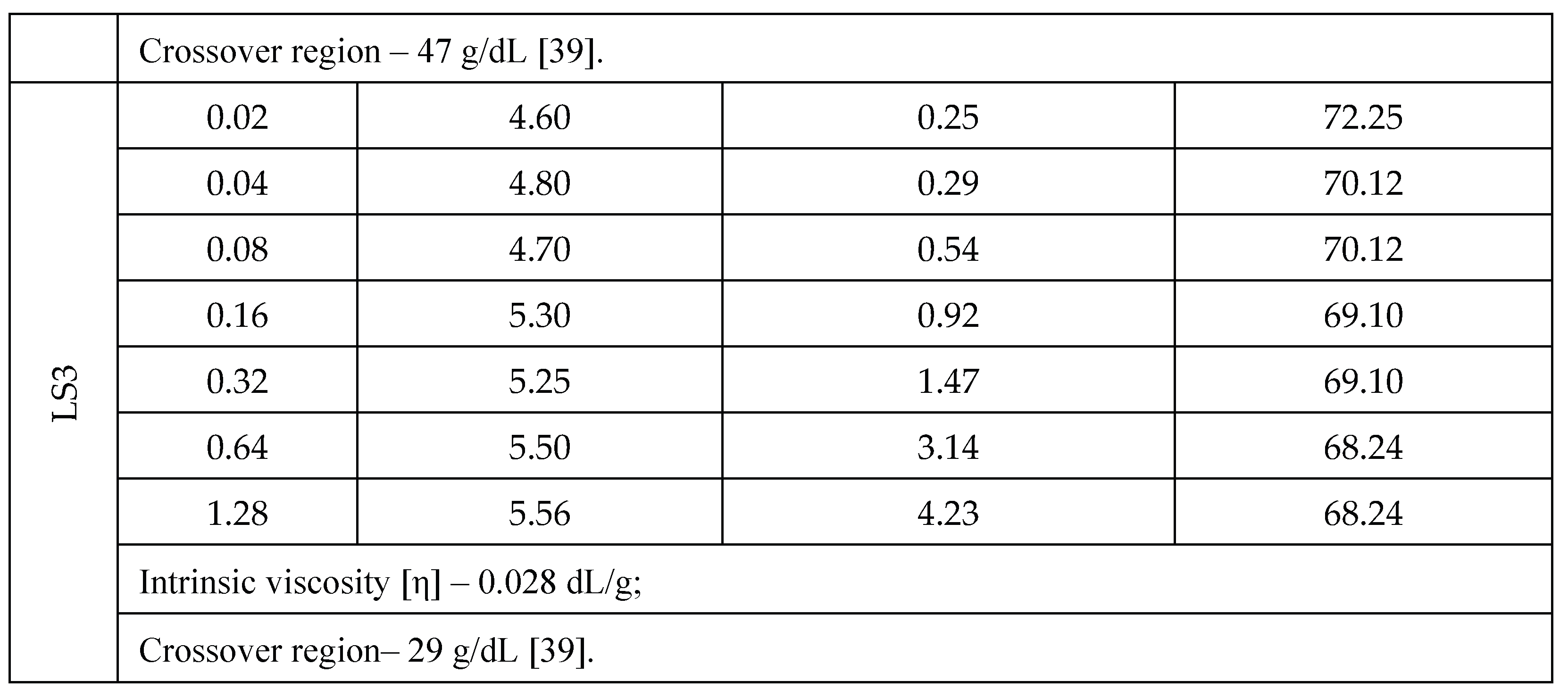

3.1. LS Behavior in an Aqueous Medium

3.2. Effect of LS of Various Molecular Weight Compositions on the Aggregation Stability of Sulfur Sols

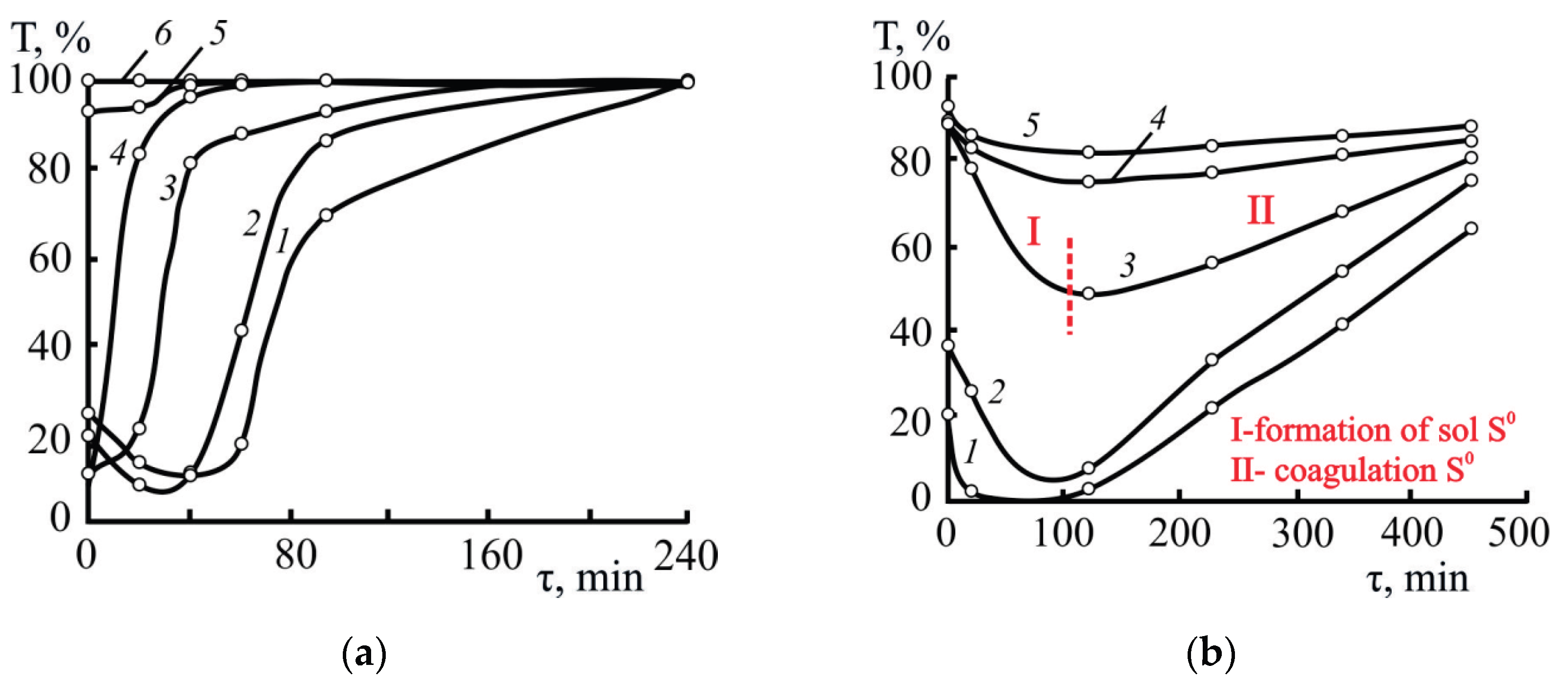

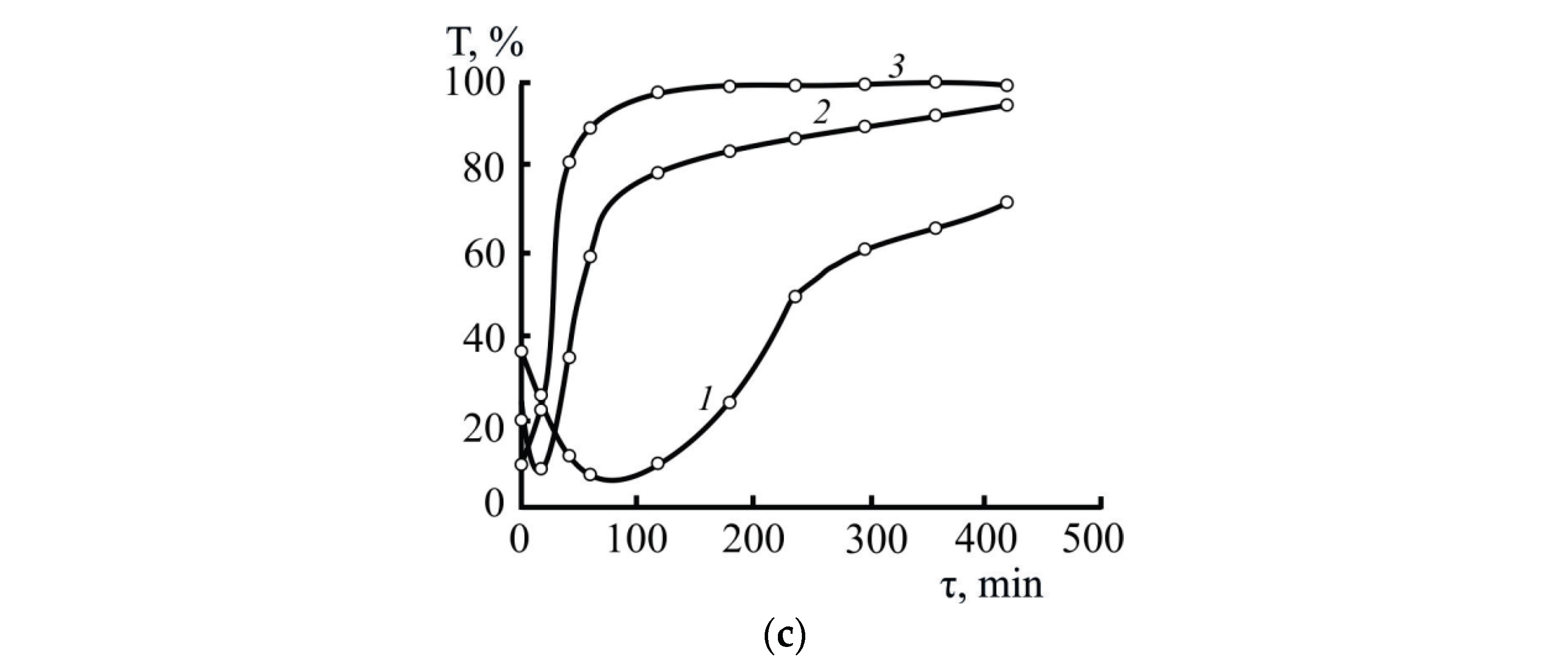

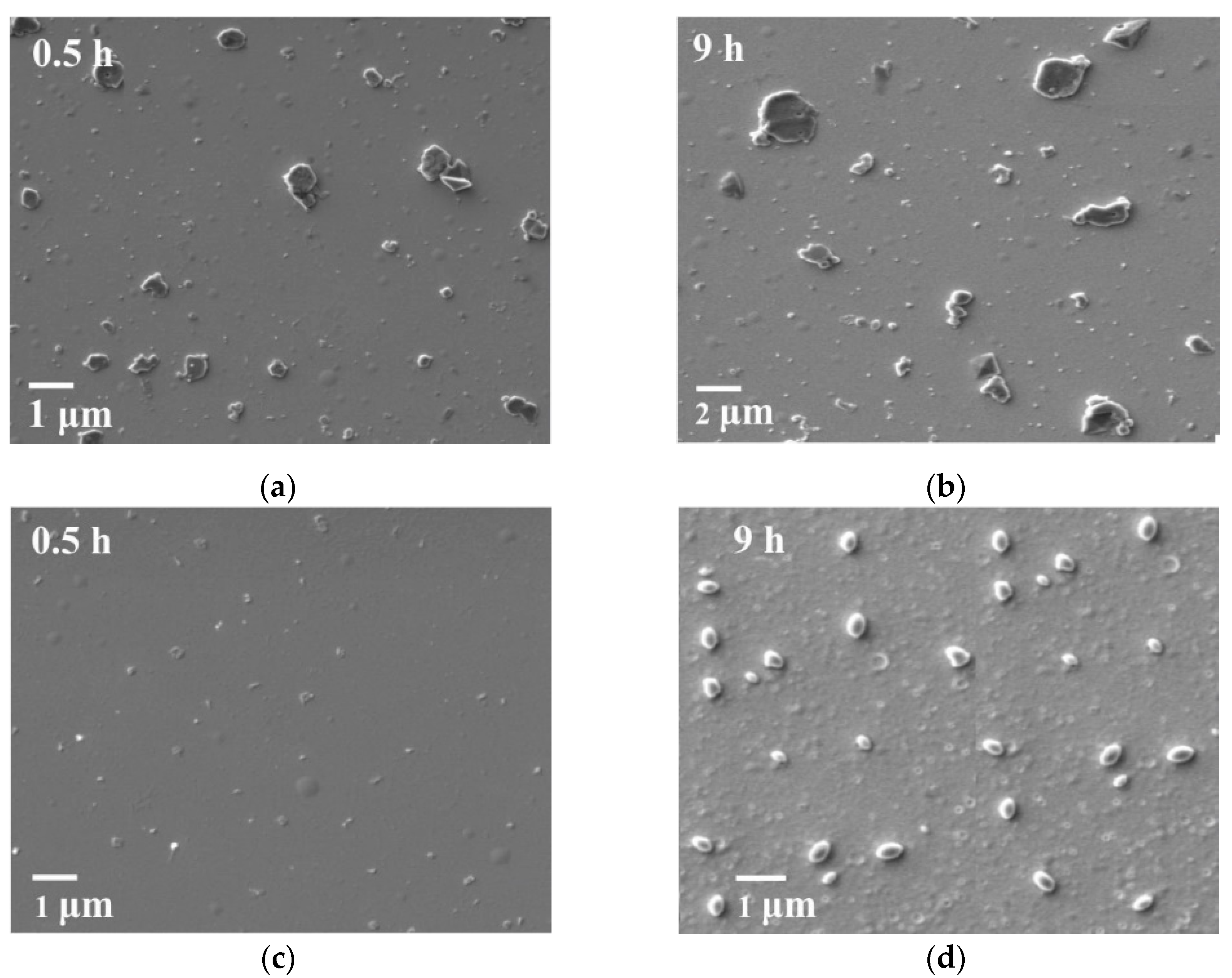

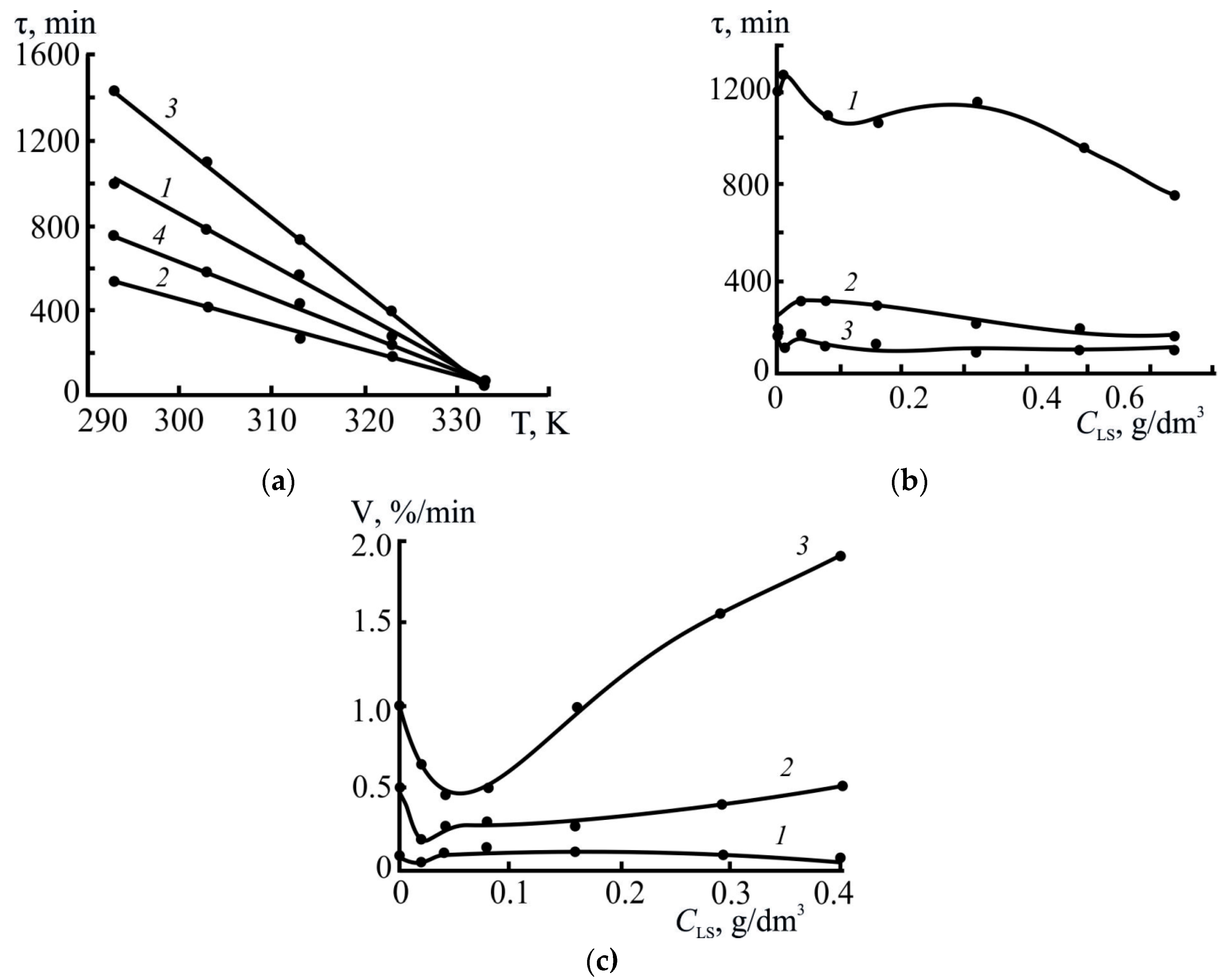

3.2.1. Selecting Optimal Parameters for the Formation and Destruction (Coagulation) of S0 Sols

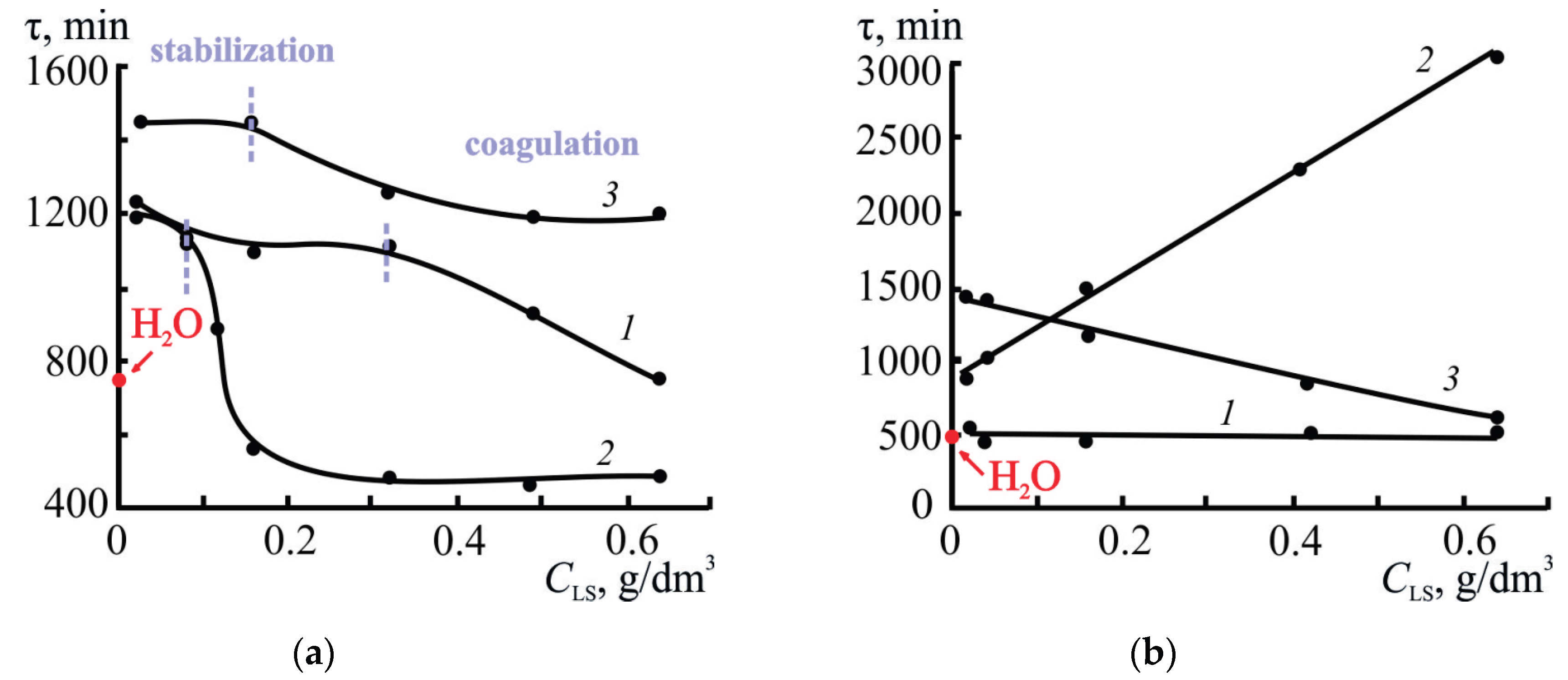

3.2.2. Effect of Concentration and Type of LS

3.2.3. Effect of Temperature

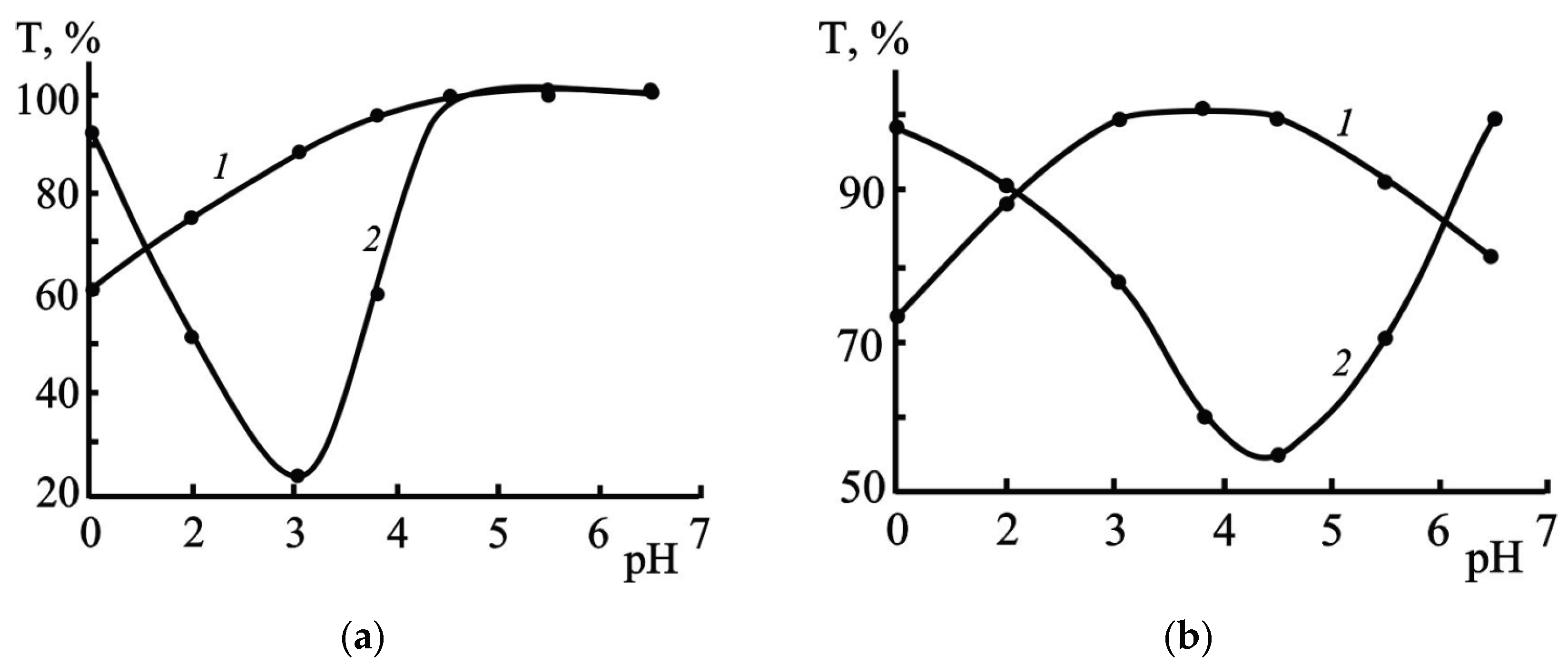

3.2.4. Effect of pH

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAC | critical association concentration |

| HLB | hydrophilic-lipophilic balance |

| LS | lignosulfonates |

| O/W | oil-in-water |

| S° | elemental sulfur |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| TEM | transparent electron microscope |

| W/O | water-in-oil |

References

- Tosin, K. G., Finimundi, N., & Poletto, M. (2025). A Systematic Study of the Structural Properties of Technical Lignins. Polymers, 17(2), 214. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Zhu, M., Jin, W., Zhang, J., Fan, G., Feng, Y., ... & Li, Y. (2025). A comprehensive review of unlocking the potential of lignin-derived biomaterials: from lignin structure to biomedical application. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 23(1), 538. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H., Su, L., Zhang, W., Sun, Y., Li, D., Li, S., ... & Li, W. (2025). Epigenetic regulation of lignin biosynthesis in wood formation. New Phytologist, 245(4), 1589-1607. [CrossRef]

- Tang, T., Fei, J., Zheng, Y., Xu, J., He, H., Ma, M., ... & Wang, X. (2023). Water-soluble Lignosulfonates: Structure, Preparation, and Application. ChemistrySelect, 8(13), e202204941. [CrossRef]

- Melro, E., Filipe, A., Sousa, D., Medronho, B., & Romano, A. (2021). Revisiting lignin: A tour through its structural features, characterization methods and applications. New Journal of Chemistry, 45(16), 6986-7013. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., & Makendran, C. (2025). Suitability analysis of sodium lignosulphonate a bio polymer as bitumen modifier for low volume roads in India. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, 10(7), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, L. R. D., Consoli, N. C., & Bastos, C. A. B. (2025). Stabilization of Dispersive Soil Using Calcium Lignosulfonate: Strength, Durability, and Microstructure Assessment. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering, 43(7), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhu, B., Yang, Z., Yang, X., Wang, J., ... & Li, Z. (2025). Improved cadmium removal from groundwater using sodium lignosulfonate stabilized hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 108085. [CrossRef]

- Wurzer, G. K., Hettegger, H., Bischof, R. H., Fackler, K., Potthast, A., & Rosenau, T. (2022). Agricultural utilization of lignosulfonates. Holzforschung, 76(2), 155-168.

- Qiu, X., Kong, Q., Zhou, M., & Yang, D. (2010). Aggregation behavior of sodium lignosulfonate in water solution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 114(48), 15857-15861. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y., Li, D., & Li, Z. (2014). Effects of lignosulfonate structure on the surface activity and wettability to a hydrophobic powder. BioResources, 9(4), 7119-7127.

- Li, B., & Ouyang, X. P. (2012). Structure and properties of Lignosulfonate with different molecular weight isolated by gel column chromatography. Advanced Materials Research, 554, 2024-2030. [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, S. A., Ese, M. H., & Sjöblom, J. (2001). Langmuir surface and interface films of lignosulfonates and Kraft lignins in the presence of electrolyte and asphaltenes: correlation to emulsion stability. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 182(1-3), 199-218. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X., Yan, M., Yang, D., Pang, Y., & Deng, Y. (2009). Effect of straight-chain alcohols on the physicochemical properties of calcium lignosulfonate. Journal of colloid and interface science, 338(1), 151-155. [CrossRef]

- Ruwoldt, J., & Øye, G. (2020). Effect of low-molecular-weight alcohols on emulsion stabilization with lignosulfonates. ACS omega, 5(46), 30168-30175. [CrossRef]

- Askvik, K. M., Hetlesæther, S., Sjöblom, J., & Stenius, P. (2001). Properties of the lignosulfonate–surfactant complex phase. Colloids and surfaces A: Physicochemical and engineering aspects, 182(1-3), 175-189. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S., & Øye, G. (2021). Aqueous carbon black dispersions stabilized by sodium lignosulfonates. Colloid and Polymer Science, 299(7), 1223-1236. [CrossRef]

- Alazigha, D. P., Indraratna, B., Vinod, J. S., & Heitor, A. (2018). Mechanisms of stabilization of expansive soil with lignosulfonate admixture. Transportation Geotechnics, 14, 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. A. (2025). Hydrophilic-lipophilic deviation. Journal of Surfactants & Detergents, 28(1).

- Pasquali, R. C., Sacco, N., & Bregni, C. (2009). The studies on hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB): Sixty years after William C. Griffin’s pioneer work (1949–2009). Lat. Am. J. Pharm, 28(2), 313-317 ,http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/7764.

- Setiati R et al. Challenge sodium lignosulfonate surfactants synthesized from bagasse as an injection fluid based on hydrophil liphophilic balance. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Bristol (UK): IOP Publishing, 2018. – Vol. 434. – P. 012083 . [CrossRef]

- Tadros TF. Emulsion formation, stability, and rheology. Emulsion Formation and Stability. 2013;1: p. 1–75. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Boschstr. 12, 69469 Weinheim, Germany.

- Perkins, K. M., Gupta, C., Charleson, E. N., & Washburn, N. R. (2017). Surfactant properties of PEGylated lignins: Anomalous interfacial activities at low grafting density. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 530, 200-208.24. [CrossRef]

- Musl, O., Sulaeva, I., Sumerskii, I., Mahler, A. K., Rosenau, T., Falkenhagen, J., & Potthast, A. (2021). Mapping of the hydrophobic composition of lignosulfonates. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 9(49), 16786-16795 ,. [CrossRef]

- Beeckmans, J. (1962). Adsorption of Lignosulphonates on Solids. Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 40(2), 265-274. [CrossRef]

- Borsalani, H., Nikzad, M., & Ghoreyshi, A. A. (2022). Extraction of lignosulfonate from black liquor into construction of a magnetic lignosulfonate-based adsorbent and its adsorption properties for dyes from aqueous solutions. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 30(10), 4068-4085. [CrossRef]

- Loginova, M. E., Movsumzade, E. M., Teptereva, G. A., Pugachev, N. V., & Chetvertneva, I. A. (2022). Variability of monomolecular adsorption of lignosulfonate systems. Russian Journal of General Chemistry, 92(9), 1866-1871. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T., Jiao, G., Wang, P., Zhu, D., Liu, Z., & Liu, Z. (2024). Lignosulphonates in zinc pressure leaching: Decomposition behaviour and effect of lignosulphonates’ characteristics on leaching performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 435, 140355. [CrossRef]

- Karimov, K. A., Rogozhnikov, D. A., Naboichenko, S. S., Karimova, L. M., & Zakhar’yan, S. V. (2018). Autoclave ammonia leaching of silver from low-grade copper concentrates. Metallurgist, 62(7), 783-789. [CrossRef]

- Kolmachikhina, E. B., Lugovitskaya, T. N., Tretiak, M. A., & Rogozhnikov, D. A. (2023). Surfactants and their mixtures under conditions of autoclave sulfuric acid leaching of zinc concentrate: Surfactant selection and laboratory tests. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 33(11), 3529-3543. [CrossRef]

- Lugovitskaya, T., Rogozhnikov, D. (2023). Surface Phenomena with the Participation of Sulfite Lignin under Pressure Leaching of Sulfide Materials. Langmuir, 39(16), 5738-5751. [CrossRef]

- Lugovitskaya, T. N., Rogozhnikov, D. A. (2024). Construction of lignosulphonate-containing polymersomes and prospects for their use for elemental sulfur encapsulation. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 400, 124612. [CrossRef]

- Lugovitskaya, T. N., Bolatbaev, K. N. (2014). Stability of elemental sulfur dispersion in the presence of lignin sulfo derivatives. Chemistry of plant raw material, 2, 79. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B. (1976). Elemental sulfur. Chemical reviews, 76(3), 367-388. [CrossRef]

- Fediuk, R., Mugahed Amran, Y. H., Mosaberpanah, M. A., Danish, A., El-Zeadani, M., Klyuev, S. V., & Vatin, N. (2020). A critical review on the properties and applications of sulfur-based concrete. Materials, 13(21), 4712. [CrossRef]

- Kuzas, E., Rogozhnikov, D., Dizer, O., Karimov, K., Shoppert, A., Suntsov, A., & Zhidkov, I. (2022). Kinetic study on arsenopyrite dissolution in nitric acid media by the rotating disk method. Minerals Engineering, 187, 107770. [CrossRef]

- G.F. Zakis, L.N. Mozheiko, G.M. Telysheva, Methods for Determining the Functional Groups of Lignin; Monograph. Zinatne Riga 1975; https://booksee.org/book/468100 (in Russian).

- Wang Z. Preparation and Influencing Factors of Sodium Lignosulfonate Nanoparticles // J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023. V. 7. №2. P. 28 – 41. [CrossRef]

- Lugovitskaya, T. N., & Kolmachikhina, E. B. (2021). Associative behavior of Lignosulphonates in moderately concentrated Water, Water–Salt, and water–alcoholic media. Biomacromolecules, 22(8), 3323-3331. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Yang, D.; Qiu, X. Effects of pH on aggregation behavior of sodium lignosulfonate (NaLS) in concentrated solutions. Journal of Polymer Research 2015, 22(4). [CrossRef]

- Finkenstadt, V. L. (2005). Natural polysaccharides as electroactive polymers. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 67(6), 735-745. [CrossRef]

- Bordi, F., Cametti, C., & Colby, R. H. (2004). Dielectric spectroscopy and conductivity of polyelectrolyte solutions. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 16(49), R1423. [CrossRef]

- Lugovitskaya, T. N., Shipovskaya, A. B., Shmakov, S. L., & Shipenok, X. M. (2022). Formation, structure, properties of chitosan aspartate and metastable state of its solutions for obtaining nanoparticles. Carbohydrate Polymers, 277, 118773. [CrossRef]

- Li, I. T., & Walker, G. C. (2012). Single polymer studies of hydrophobic hydration. Accounts of chemical research, 45(11), 2011-2021. [CrossRef]

- Ernsberger, F. M., & France, W. G. (1948). Some Physical and Chemical Properties of Weight-Fractionated Lignosulfonic Acid, including the Dissociation of Lignosulfonates. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 52(1), 267-276. [CrossRef]

- Vainio, U., Lauten, R. A., & Serimaa, R. (2008). Small-angle X-ray scattering and rheological characterization of aqueous lignosulfonate solutions. Langmuir, 24(15), 7735-7743. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B. (1976). Elemental sulfur. Chemical reviews, 76(3), 367-388. [CrossRef]

- Tian, B., Fan, Z., Hou, T., Liu, Z., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Exploring Elemental Sulfur-Solvent Interactions via Density Functional Theory. ChemistrySelect, 10(6), e202405654. [CrossRef]

- Lugovitskaya, T. N., Rogozhnikov, D. A., & Mamyachenkov, S. V. (2025). Preparation of lignosulphonate nanoparticles and their applications in dye removal and as plant growth stimulators. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 417, 126693.

- Lugovitskaya, T. N., Ulitko, M. V., Kozlova, N. S., Rogozhnikov, D. A., & Mamyachenkov, S. V. (2023). Self-assembly polymersomes based on sulfite lignins with biological activity. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 97(3), 534-539. [CrossRef]

- Lugovitskaya, T. N., Naboychenko, S. S. (2020). Lignosulfonates as charge carriers and precursors forthe synthesis of nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 602, 125127. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A. A., & Druschel, G. K. (2014). Elemental sulfur coarsening kinetics. Geochemical Transactions, 15(1), 11. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R. G., & Paria, S. (2011). Growth kinetics of sulfur nanoparticles in aqueous surfactant solutions. Journal of colloid and interface science, 354(2), 563-569. [CrossRef]

- Ruwoldt, J. (2022). Emulsion stabilization with lignosulfonates. In Lignin-Chemistry, Structure, and Application. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Functional group content, % | , kDa | |||||||

| C | H | O | S | Men+ | SO3H | OCH3 | OHphen | ||

| LS1 | 33.9 | 4.72 | 46.8 | 9.5 | Na 5.7 | 13.4 | 11.3 | 2.56 | 18.40 |

| LS2 | 38.82 | 4.36 | 42.35 | 5.50 | Na 6.6 | 12.68 | 10.6 | 2.32 | 9.25 |

| LS3 | 48.70 | 4.52 | 38.20 | 4.24 | Ca 3.0 | 12.30 | 9.2 | 2.10 | 46.30 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).