1. Introduction

Over the past decades, nanotechnology has significantly transformed the field of drug research and nanomedicine [

1,

2]. Metal nanoparticles have emerged as pivotal elements in nanotechnology, offering great potential as carriers for chemotherapeutic drugs, proteins, and siRNA, etc. Among them, selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) have garnered particular attention due to their unique biological properties. Selenium (Se) was first identified by Jöns Jacob Berzelius in 1817 [

3]. The element was named after the Greek word ‘Selene,’ meaning moon. [

4]. In its elemental form, selenium is colorless, non-toxic, and biologically inert [

3]. It plays a crucial role in maintaining a healthy immune system and preventing disease [

5]. It is also involved in cancer prevention, cardiovascular health, and alleviating fatigue [

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, SeNPs hold significant potential as drug carrier of therapeutic agents for cancer treatment [

9]. Recent studies have highlighted the advantages of SeNPs as a novel form of selenium, particularly in terms of their high biocompatibility and surface modifiability compared to other selenium compounds, which has sparked significant interest [

10,

11]. However, a major challenge with SeNPs is their instability and tendency to agglomerate, resulting in black precipitates that greatly diminish their bioavailability [

12]. Therefore, enhancing the stability of SeNPs has become a research focus. To address this issue, various biological macromolecules, including polysaccharides [

13], peptides [

14], and synthetic polymers [

15], have been employed to modify SeNPs, preventing their aggregation and enhancing their stability for better bioavailability.

Polysaccharides extracted from natural sources such as plants, animals, fungus, and seaweeds [

16], have been extensively studied in the fields of biotechnology and biomedicine [

17], thanks to their unique properties, including biocompatibility and biodegradability which are crucial for applications as biomaterials [

18]. When used as stabilizing and dispersing agents, polysaccharides have significantly improved the stability, biocompatibility, and biological activities of SeNPs. The antioxidant properties of polysaccharide-coated SeNPs have attracted considerable attention as oxidative damage plays a crucial role in many diseases and injuries [

19,

20].

Ononis natrix L. (Leguminosae/Fabiaceae) is a perennial shrublet native to Africa, South-West Europe, and the northwest region of Saudi Arabia. This plant has been utilized in the treatment of urinary tract infections for its diuretic, antihypertensive, antibacterial, and antirheumatic properties [

21]. Importantly, polysaccharides extracted from

O. natrix exhibit notable antioxidant and antibacterial activities [

22]. However, there is currently no information available regarding the use of

O. natrix polysaccharides as stabilizers for SeNPs.

In the present study, polysaccharides extracted from O. natrix were purified and characterized. The purified polysaccharides, namely P2, were then utilized as stabilizing and capping agents to synthesize SeNPs using a redox system composed of sodium selenite (Na2SeO3) and ascorbic acid known as Vitamin C. The resulting P2-SeNPs were characterized by using various techniques, including dynamic light scattering (DLS), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy (UV–Vis), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The stability of P2-SeNPs was assessed under different conditions. Furthermore, the in vitro antioxidant activity of P2-SeNPs was evaluated and compared to that of SeNPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polysaccharides were extracted from

O. natrix using hot water maceration method. More detailed characterization of obtained polysaccharides has been reported in our previous paper [

22]. 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), sodium selenite, and ascorbic acid were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and used as received.

2.2. Purification of Polysaccharides Extracted from O. natrix

The crude polysaccharide was dissolved in deionized water and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant, containing soluble polysaccharides, was applied to a DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow column (25 mm × 30 cm) and eluted with 100 mL of water, followed by elution with of NaCl solutions with gradient concentrations 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 M at a flow rate of 3 mL/min. The volume of each collected aliquot was 5 mL. The eluate fractions were collected and analyzed using the phenol-sulfuric acid method. The major fraction eluted with water was collected and lyophilized, yielding purified polysaccharides named PS1. Similarly, fractions eluted with 0.2 and 0.4 M of NaCl were collected and lyophilized. PS1 was further purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Sephadex G-100 column (Ø 1.5 × 100 cm). Distilled water was used as the mobile phase, applied at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, and monitored using the phenol-sulfuric acid method. Fractions corresponding to P1 and the main peak P2, were collected and lyophilized. The carbohydrate content was determined using the phenol-sulfuric acid method with D-glucose as the standard [

23].

2.3. Synthesis of SeNPs Stabilized with Purified Polysaccharides P2 (P2-SeNPs)

P2-SeNPs were synthesized by reducing sodium selenite with ascorbic acid. Briefly, various P2 solutions at concentrations of 1-5 mg/mL were mixed with an equal volume of 0.01 M Na2SeO3 solution under magnetic stirring. Then, an equal volume of freshly prepared 0.04 M ascorbic acid solution was added dropwise to the mixture under vigorous stirring, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C in the dark for 4 h. Finally, the solution was dialyzed (MWCO 3500 Da) against deionized water in the dark at 4 °C for 3 to 4 days to remove excess ascorbic acid and Na2SeO3. For the sake of comparison, SeNPs were synthesized using the same method, but with an equal volume of distilled water replacing the P2 solution.

2.4. Physicochemical Characterization

2.4.1. Gel Permeation Chromatography

The molecular weight of polysaccharides was determined using the gel permeation chromatography (GPC). Measurements were made at 30 °C on a "Shimadzu Nexera LC system" equipped with two detectors: RID-20A Refractive Index Detector and SPD-40 UV detector. The system is equipped with three columns: 1 × PL Aquagel-OH 8 µm guard column (50 × 7.5 mm, Agilent), 1 × PL Aquagel-OH 30 8 µm (300 × 7.5 mm, Agilent), and 1 × PL Aquagel-OH 40 8 µm (300 × 7.5 mm, Agilent). The mobile phase was a pH 7 phosphate buffer, and the flow rate was 1 mL/min. Pullulan standards were used for calibration.

2.4.2. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) and carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) spectra were acquired at 25 °C on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer. Deuterium oxide (D2O) was used as the solvent. Chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm). The spectra were processed using Mestre Nova 5.3.0 software from Mestrelab Research.

2.4.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) and UV-Visible Spectroscopy

FT-IR analysis was performed using a Carry 630 series spectrometer (Agilent Technologies) equipped with an attenuated reflection accessory (ATR) containing a diamond crystal/ZnSe. An average of 32 scans was collected with a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the wavenumber range of 650–4000 cm−1. Data analysis was performed using OMNIC Spectra software (Thermo Fisher Scientific software). UV-visible spectrophotometer was used to measure ultraviolet absorbance in the range of 200 to 800 nm.

2.4.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA thermograms were registered using TGAQ 500 Analyzer (TA Instruments). Measurements were performed in the temperature range from 25 °C to 700 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min.

2.4.5. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

The average particle size and zeta potential were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Litesizer 500 particle instrument (Anton Paar, GmbH, France) at 25 °C. Measurements were made in triplicate.

2.4.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

TEM was performed using a 200 kV TEM 2200FS instrument (JEOL). P2-SeNPs and SeNPs samples were prepared by depositing a drop of 5 µL onto a Formvar/carbon-coated Cu grid, followed by air drying at ambient temperature before measurements. TEM images were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

2.4.7. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD patterns were acquired using an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D5000) with a Cu-Kα radiation source. Measurements were carried out from 7 to 40° (2θ, diffraction angle) at a scanning speed of 1°/min. The diffractograms were obtained at a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 20 mA.

2.4.8. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS spectra were registered on a Thermo Electron ESCALAB 250 spectrometer to determine the valence state of selenium in lyophilized NPs, using Al Kα line (1486.6 eV) as monochromatic excitation source. The photoelectrons were analyzed at a normal incidence of the sample surface. A surface area of 500 µm2 was analyzed. The photoelectron spectra were calibrated for binding energy relative to the energy of the C-C component of carbon 1s at 284.8 eV. Charge compensation was achieved using an electron beam (-2 eV).

2.5. Stability Test

The storage stability was evaluated by examining the effects of light, pH, ionic strength, temperature (4 and 25 °C), and time (0 to 30 days) on P2-SeNPs. DLS measurements were conducted at regular intervals to determine the average diameter of P2-SeNPs in solution.

To assess the effect of pH on stability, the pH of P2-SeNPs solutions was adjusted to 2, 7, and 10 using 0.1 M HCl/NaOH, and stabilized for 1 h. The particle size was then measured.

The stability under different ionic strengths was evaluated by adding NaCl solution (2 mL) at various concentrations (10, 50, 100, 200 mM) to the P2-SeNPs solution (2 mL). The particle size was determined after 1 h stirring.

2.6. Antioxidant Activities of Nanoparticles

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined according to the method of Bersuder [

24]. Sample solution (500 µL) was mixed with 500 µL of DPPH solution (0.2 mM in ethanol). After 30 min incubation in complete darkness, the absorbance of the mixture was measured at 517 nm. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was calculated using the following formula:

where A

c, A

b, and A

s represent the absorbance of the control (containing all reagents except the sample), the blank (containing all reagents except the DPPH solution), and the sample solution in the reaction mixture, respectively.

The ferrous chelating capacity was determined using the method of Carter [

25]. Firstly, 100 mL of 2 mM FeCl2 were mixed with 200 mL of sample solution. After 5 min incubation at room temperature, 400 µL of 5 mM ferrozine solution were added. The mixture was then vigorously stirred, and the reaction proceeded at room temperature for 10 min. Finally, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 562 nm. The ferrous ion-chelating activity, defined as the inhibition rate of ferrozine/Fe2+ complex formation, was calculated using the following formula:

where A

c is the absorbance of the control (without sample), A

b is the absorbance of the blank (without ferrozine), and A

s is the absorbance of the sample. Triplicate measurements were made for each sample.

The total antioxidant activity of a molecule is determined by its ability to inhibit the ABTS radical cation (ABTS

•+), obtained from ABTS. A 7 mM aqueous solution of ABTS was mixed with a 2.45 mM aqueous solution of potassium persulfate in equal volumes and stored in the dark at room temperature for 12 h to obtain the ABTS

•+ solution. Then, an aliquot (3 mL) of the ABTS

•+ solution was added to the sample (1 mL) and incubated in the dark. After 30 min, the absorbance at 734 nm was measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer, and the ABTS radical scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

where A

c, A

b, and A

e represent the absorbance of the control (containing all reagents except the hydrogel sample), the blank (containing all reagents except the ABTS radical cation solution), and the sample solution in the reaction mixture, respectively [

26].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS ver.17.0, professional edition. The mean differences between tests were examined by the Duncan test and compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered significant at p-value < 0.05. All tests were carried out in triplicate.

3. Results

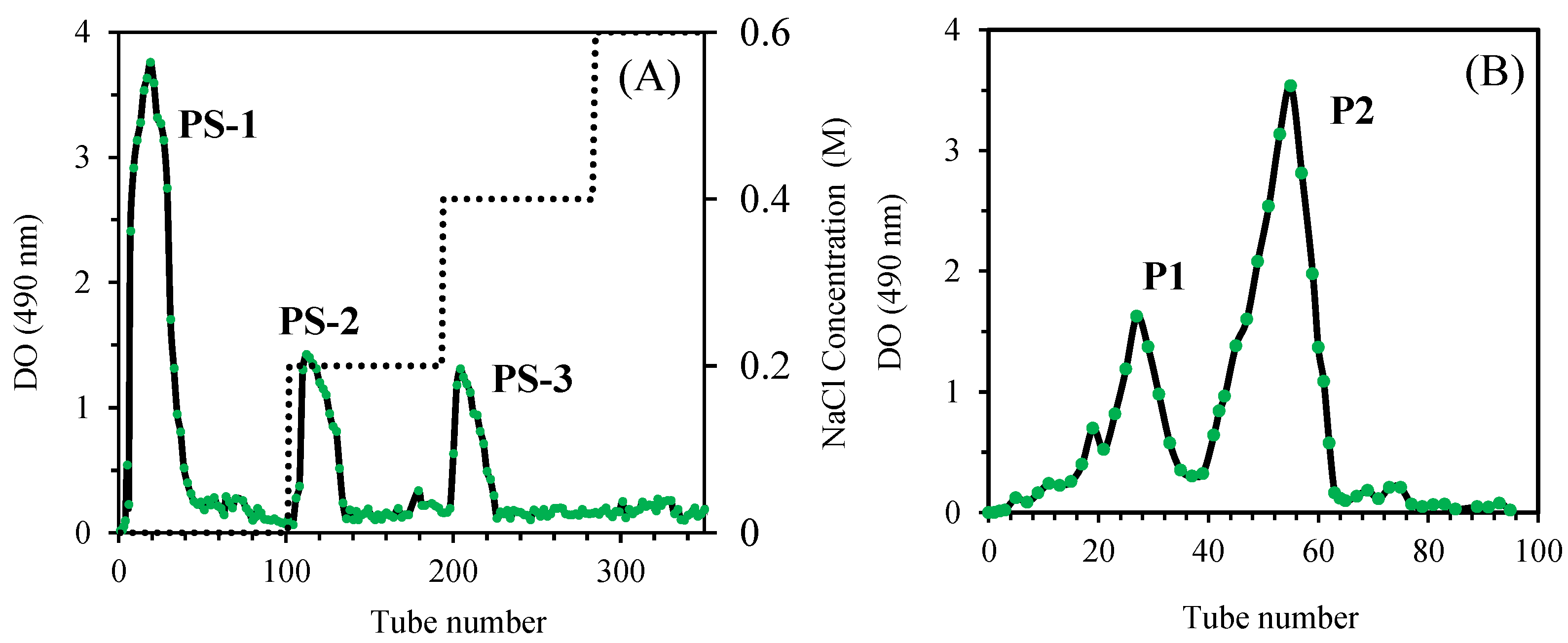

3.1. Purification of O. natrix Polysaccharides

The purification of crude polysaccharides was carried out using two complementary chromatography techniques: ion-exchange chromatography and gel filtration chromatography. The first purification step involved ion-exchange chromatography on a DEAE-Sepharose fast flow column. This technique enabled the separation of three fractions: PS-1, eluted with deionized water, PS-2 and PS-3, eluted at NaCl concentrations of 0.2 M and 0.4 M, respectively. The yield obtained for these fractions was 61.2 ± 1.7% for PS-1, 11.9 ± 0.5% for PS-2, and 6.8 ± 0.7% for PS-3 (

Figure 1A). The PS-1 fraction, corresponding to the major peak observed during the first separation, was further purified by gel filtration chromatography using a Sephadex G-100 column. Gel filtration chromatography allowed the isolation of two purified fractions, named P1 and P2, by eluting with deionized water. The yield of P1 and P2 was 17.9 ± 0.6% and 67.5 ± 1.3%, respectively. Analyses revealed a total sugar content of 94.5 ± 0.3% and 98.1 ± 0.5% for P1 and P2, respectively, indicating a very high purity of the obtained polysaccharides (

Figure 1B).

3.2. Structural Characterization of Purified Polysaccharides

3.2.1. Molecular Weights

GPC was used to determine the molecular weights of the purified fractions P1 and P2, using pullulan as the calibration standard. As illustrated in

Table 1 and

Figure S1 (Supplementary data), P1 exhibits two distinct fractions, a small fraction with weight-average molecular weight (Mw) of 732.6 kDa and dispersity (Ð) of 1.1, and a major fraction with Mw of 74.4 kDa and Ð of 1.6. The presence of two peaks suggests that P1 consists of chains of varying lengths. In contrast, P2 displays a single peak with Mw of 30.2 kDa and Ð of 1.7. Although P2 shows slightly higher dispersity and lower average Mw, the absence of multiple fractions suggests higher homogeneity in chain lengths compared to P1.

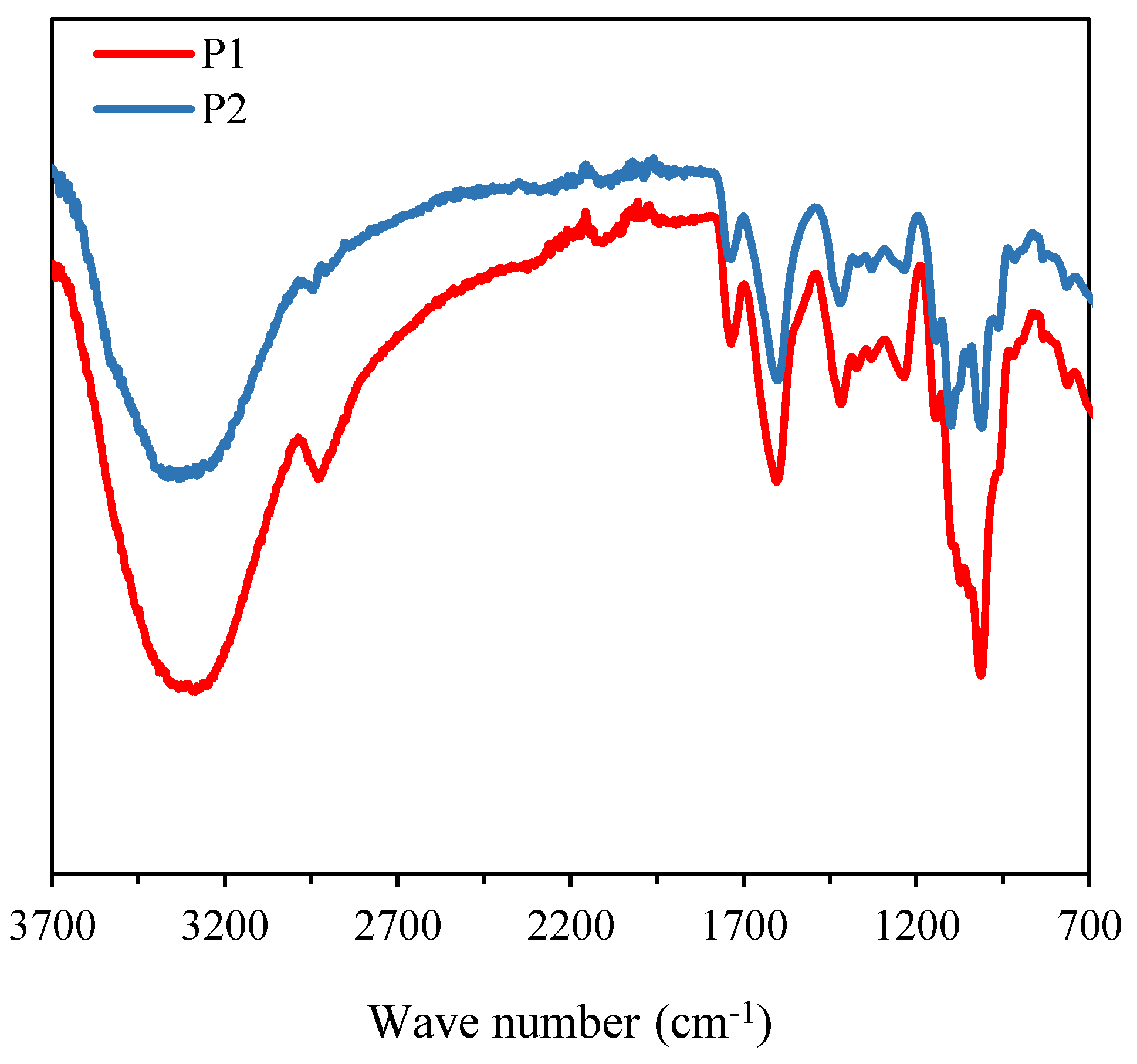

3.2.2. FT-IR Analysis

The FT-IR spectra of the purified polysaccharides, namely P1 and P2, are shown in

Figure 2. Both polysaccharides exhibit characteristic bands of hydroxyl groups (O-H) at approximately 3325 cm⁻¹ and C-H stretching vibrations around 2929 cm⁻¹ [

27,

28]. P1 and P2 also present C=O stretching bands at 1741 cm⁻¹, as well as C-O stretching bands at 1417 cm⁻¹, and asymmetric C=O or C-O stretching vibrations at 1606 cm⁻¹ [

29]. The signal at 1267 cm⁻¹ is associated with C-O stretching vibrations [

30]. The absorption peaks at 1097 cm⁻¹ and 1010 cm⁻¹ are attributed to the vibrations of the C-O-C group in a six-membered ring [

29]. In summary, P1 and P2 present similar functional groups, but the band at 1097 cm⁻¹ reveals some structural difference between the two polysaccharides.

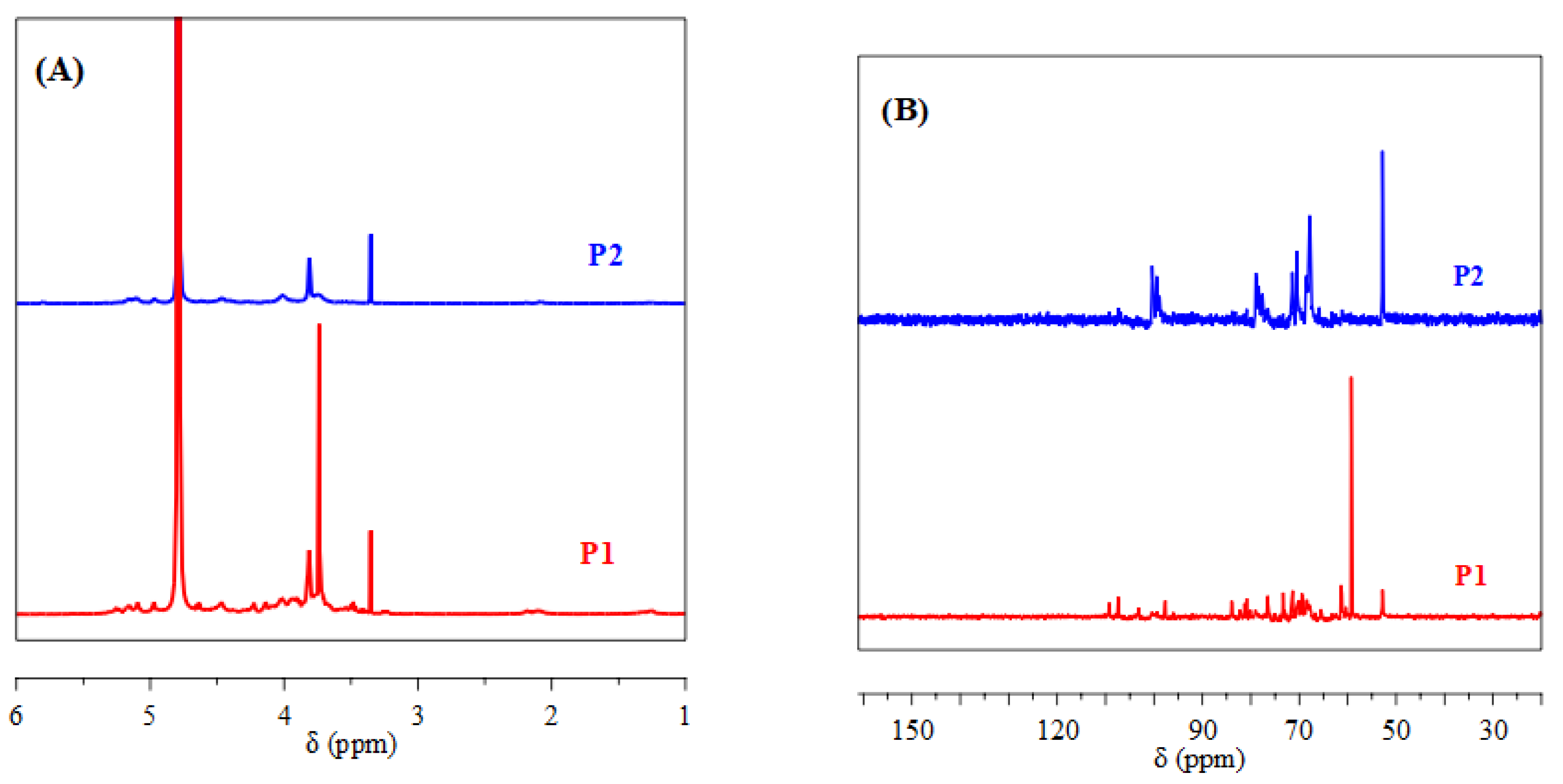

3.2.3. NMR Analysis of Purified Polysaccharides

P1 and P2 were analyzed by NMR to further elucidate their structures and chemical compositions. As shown in

Figure 3A, the hydrogen signals (H-2 to H-6) of P1 and P2 are concentrated in the δ 4.5–3.0 ppm region, characteristic of polysaccharides. Signals in the 4.2 to 4.7 ppm and 4.8 to 5.2 ppm regions correspond to α-anomeric and β-anomeric protons, respectively, indicating the presence of α- and β-terminal configurations in both polysaccharides [

31]. A distinct signal at 5.10 ppm, attributed to H-1 of α-Rha residues, is detected in the spectra of both P1 and P2 [

32]. Signals observed at 4.47 ppm in P1 and 4.46 ppm in P2 indicate β-(1→3)-glycosidic linkages [

33]. The region between 3.2 and 3.77 ppm is typical of polysaccharide residues such as galactose and xylose [

34]. Signals at 3.82 ppm in both samples belong to β-D-Galp residues [

35].

The

13C NMR spectra reveal the presence of α and β configurations for the anomeric carbons, with chemical shifts in the ranges of 90–100 ppm and 100–106 ppm (

Figure 3B), respectively [

36]. The 69–79 ppm region is identified as the pyranose ring region (C2–C5) [

37]. Signals at 107 ppm in P1 and 84 ppm in P2 are related to the presence of furanose rings [

38]. Signals in the 5.50–4.40 ppm (

1H NMR) and 90–110 ppm (

13C NMR) regions are assigned to the anomeric protons and carbons of D-Galp, L-Rhap, and D-Araf residues, respectively [

39,

40]. Signals at 78.6 and 71.3 ppm in P1 and P2 are attributed to L-Rhap carbons, while signals around 68 ppm correspond to C-6 of D-Galp [

41]. Signals recorded at 103.1 and 61.4 ppm in P1 for galactoses and at 100.4 ppm in P2 for xylose are also identified [

42]. Finally, signals at 107.3 ppm in P1 and P2 correspond to α-L-Araf [

43]. P1 and P2 polysaccharides reveal common structural features, such as the presence of α-L-Rhamnose residues, β-(1→3)-glycosidic linkages, and β-D-Galactose residues. However, differences may exist in the relative proportions of these units.

3.2.4. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The TGA thermograms of polysaccharides P1 and P2 are shown in

Figure S2. Up to 200 °C, a mass loss of 17% and 20% is detected for P1 and P2, respectively, which is attributed to the evaporation of adsorbed water, including both free water and bound water [

44]. Beyond this temperature, between 200 °C and 400 °C, a major decomposition of polysaccharides occurs. P1 decomposes more extensively than P2, indicating a significant weight loss. The third stage occurs beyond 450 °C, where both P1 and P2 undergo continuous decomposition with increasing temperature [

45], leading to further weight loss. A total weight loss of 83.6% and 71.3% is obtained for P1 and P2, respectively. It is hypothesized that the substantial degradation of P1 during the third stage may be attributed to its predominantly linear polysaccharide structure. Previous studies have demonstrated that a highly branched polysaccharide structure can significantly improve the thermal stability [

46].

3.3. Synthesis and Characterization of P2 Stabilized Selenium Nanoparticles

The combination of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) with natural polysaccharides through a green strategy can effectively address the inherent limitations of SeNPs, thereby enhancing their bioavailability and expanding their potential applications in biomedicine [

47]. In this work, purified polysaccharide P2 was selected for use as stabilizer in the synthesis of SeNPs due to its high yield and molecular weight homogeneity. P2-functionalized SeNPs (P2-SeNPs) were prepared through the reaction between sodium selenite and ascorbic acid.

3.3.1. Particle Size and Dispersion

The size and zeta potential of SeNPs are critical for their stability and medical applications [

48]. DLS is a powerful tool for analyzing particle size, size distribution, and zeta potential of nanomaterials in solution [

49,

50].

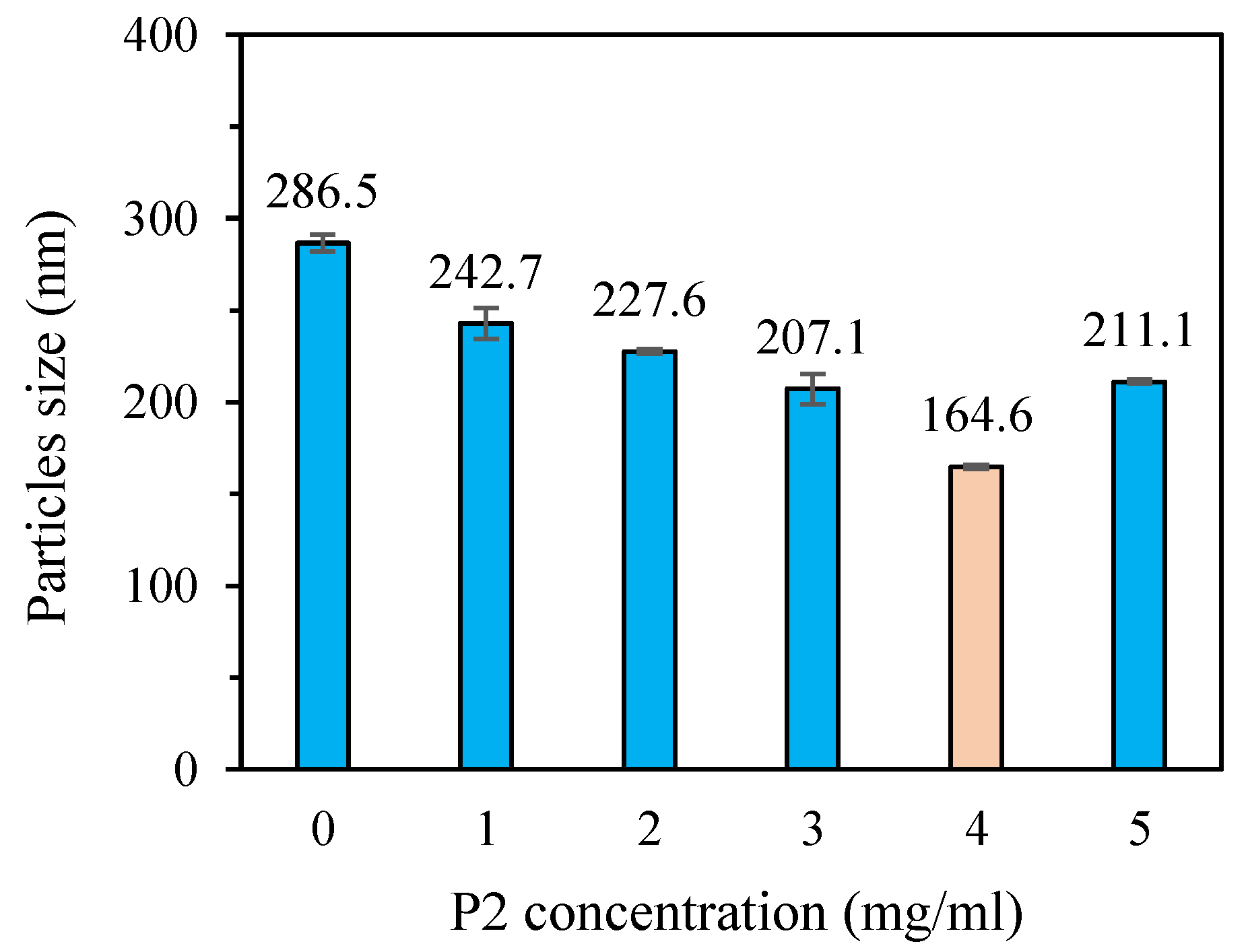

To obtain nano-sized SeNPs with good stability, five types of SeNPs stabilized with P2 concentrations ranging from 1 to 5 mg/mL, along with a control without P2, were prepared. The presence of P2 has a significant influence (p<0.05) on the average particle diameter (

Figure 4). In the SeNPs solution without P2, the selenium is unstable and tends to aggregate. A diameter of 286.5 nm was obtained. When P2 was added in the reaction mixture, polysaccharide chains could adsorb onto the surface of growing SeNPs due to the presence of numerous hydroxyl groups, leading to better dispersion of SeNPs and significant reduction in particle size [

9,

51]. The diameter decreases with increasing P2 concentration in the reaction mixture, reaching 242.7, 227.6, 207.1 and 164.6 nm for P2-SeNPs at P2 concentration of 1, 2, 3 and 4 mg/mL, respectively. However, at a concentration of 5 mg/mL, the particle size of P2-SeNPs increased to 211.1 nm. This could be explained by the interactions between excess P2 chains present in the solution. Indeed, the interactions between P2 chains are stronger than those between P2 and SeNPs, leading to agglomeration of the SeNPs because of less P2 chains available for stabilization [

52]. In conclusion, at a P2 concentration of 4 mg/mL, P2-SeNPs exhibit the smallest particle size. Further analyses will be conducted on P2-SeNPs prepared with P2 at a concentration of 4 mg/mL.

As shown in

Figure S3A, the solution of SeNPs prepared without using P2 as stabilizing agent is turbid due to aggregation [

51]. In contrast, the addition of P2 (4 mg/mL) results in a clear orange-red solution of P2-SeNPs (

Figure S3A). It is assumed that the presence of polysaccharides protects SeNPs from oxidation during lyophilization. The protective layer provided by P2 likely inhibits interaction of selenium with oxygen, maintaining the integrity of the nanoparticles (

Figure S3B). It was also observed that SeNPs in the absence of P2 tend to precipitate, whereas the orange-red solution of P2-SeNPs remains homogeneous without visible precipitation after storage at 4 °C for 30 days (

Figure S3C). These results suggest that P2 plays a crucial role in stabilizing SeNPs. According to Stokes’ law, systems with larger particle sizes exhibit lower stability [

53]. Moreover, P2-SeNPs exhibit a more negative zeta potential (-13.8 mV) compared to SeNPs (-6.3 mV), indicating better stability of P2-SeNPs in aqueous solution. All these findings suggest that P2 at an optimal concentration (4 mg/mL) plays a crucial role in stabilizing SeNPs. It is also noteworthy that SeNPs have a narrower particle size distribution with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.19, as compared to P2-SeNPs with a PDI of 0.24 (

Figure S4).

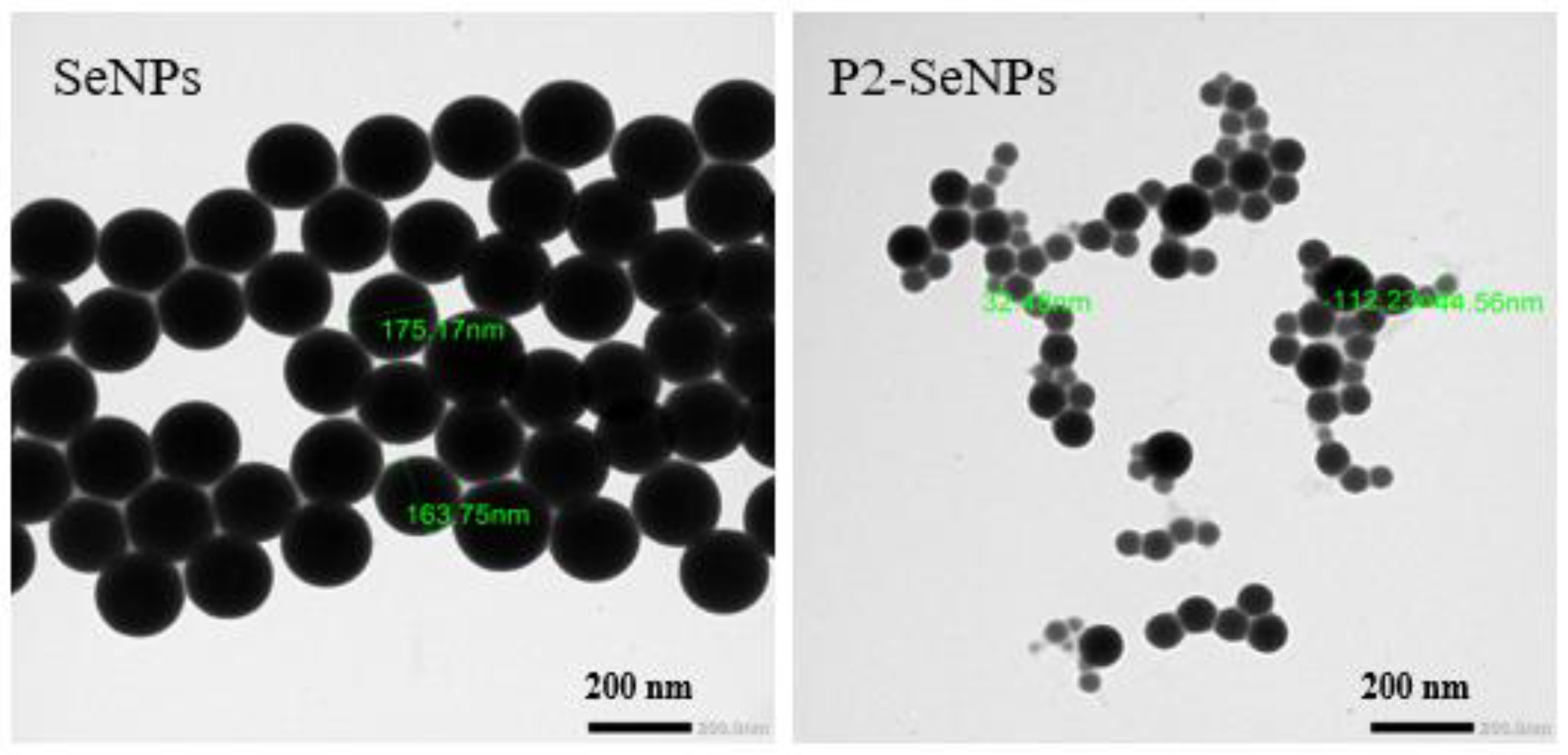

3.3.2. Morphological Evaluation

TEM is a commonly used technique to visualize the morphology of nanoparticles [

54]. As shown in

Figure 5, without the addition of P2, the synthesized SeNPs exhibit a uniform distribution of particle sizes from 163 to 175 nm. In contrast, P2-SeNPs present dispersion and smaller particle size compared to SeNPs, varying from 32 to 112 nm. SeNPs are unstable and aggregated to a large cluster. These results highlight the essential role of P2 in stabilizing SeNPs, attributed to the abundance of terminal hydroxyl groups on polysaccharide chains, which strongly adsorb onto the SeNP surface [

55]. It is also worthy to note that the size measured by TEM is smaller than that obtained by DLS because TEM measures the nanoparticle size in a dry state, while DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter which includes the particle core along with associated solvent corona.

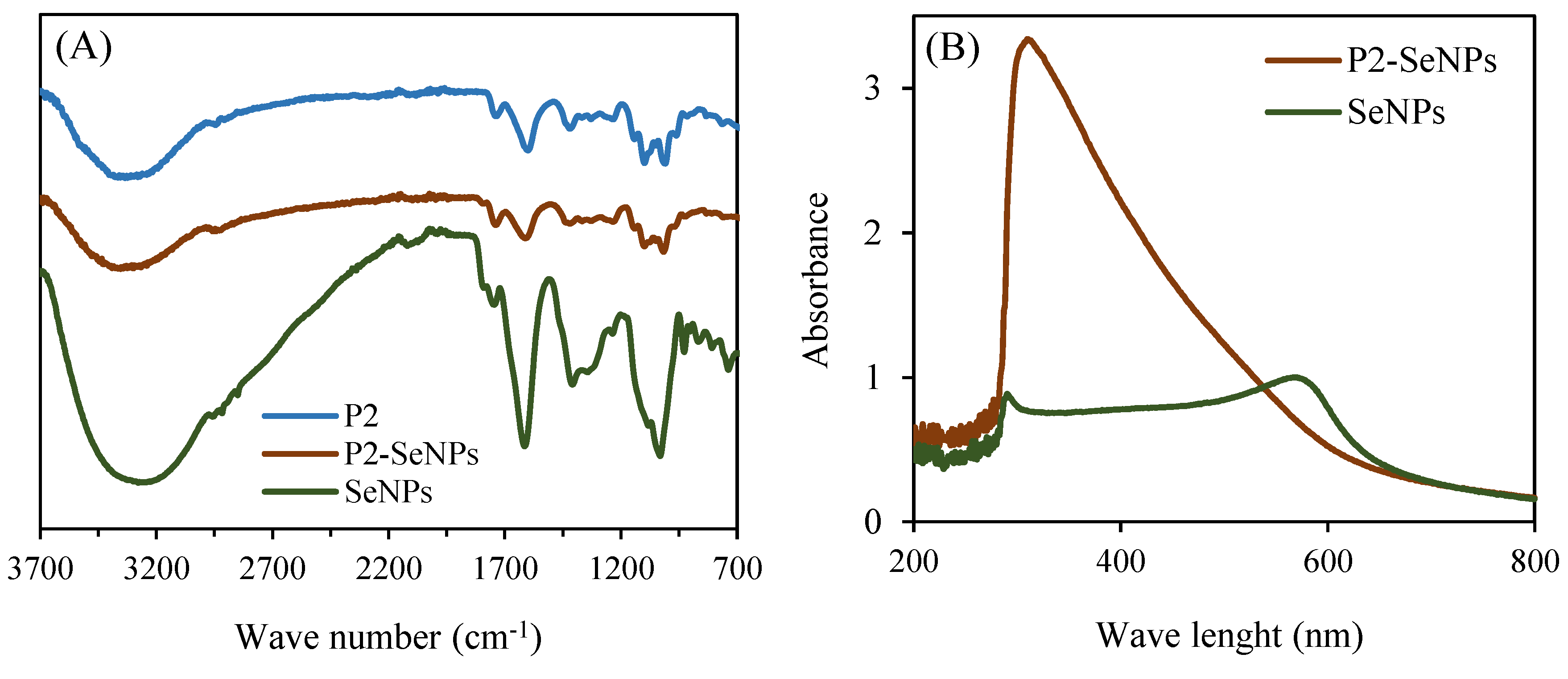

3.3.3. Interactions Between P2 and SeNPs via FT-IR Spectroscopy Analysis

The interaction mechanism between P2 and SeNPs was confirmed using FT-IR spectroscopy (

Figure 6A). Generally, no significant differences were observed between the characteristic peaks of P2 and those of P2-SeNPs. However, slight stretching vibrations were noted at two specific peaks. In all three spectra, the characteristic absorption peaks of hydroxyl groups (−OH stretching) were identified. However, the characteristic hydroxyl peak shifted from 3297 cm

−1 (P2) to 3318 cm

−1 (P2-SeNPs), suggesting a hydrogen bond interaction between the O−H groups of P2 and SeNPs [

51]. On the other hand, the characteristic”peak’ of SeNPs were clearly different from those of P2 and P2-SeNPs, except for the peaks at 1743 and 1409 cm

−1. The results suggest that Se−O bonds may form between SeNPs and P2 [

56]. Similar studies have shown that polysaccharides extracted from

Citrus limon (L.) Burm. F. (Rutaceae) [

50] and

Polyporus umbellatus [

51] could bind to SeNPs.

3.3.4. UV-Vis spectroscopy analysis

Figure 6B presents the UV-Vis absorption spectra of P2-SeNPs and SeNPs. A large absorption peak is detected for P2-SeNPs at 300 nm, and a smaller one is detected for SeNPs. This peak is attributed to the surface plasmonic response of colloidal SeNPs [

57], which is consistent with the peak reported for SeNPs prepared from Na₂SeO₃ [

58]. Additionally, the absorption peak of SeNPs at 600 nm highlights the unstable property of SeNPs without P2, thus confirming that unmodified SeNPs were unstable and prone to precipitation.

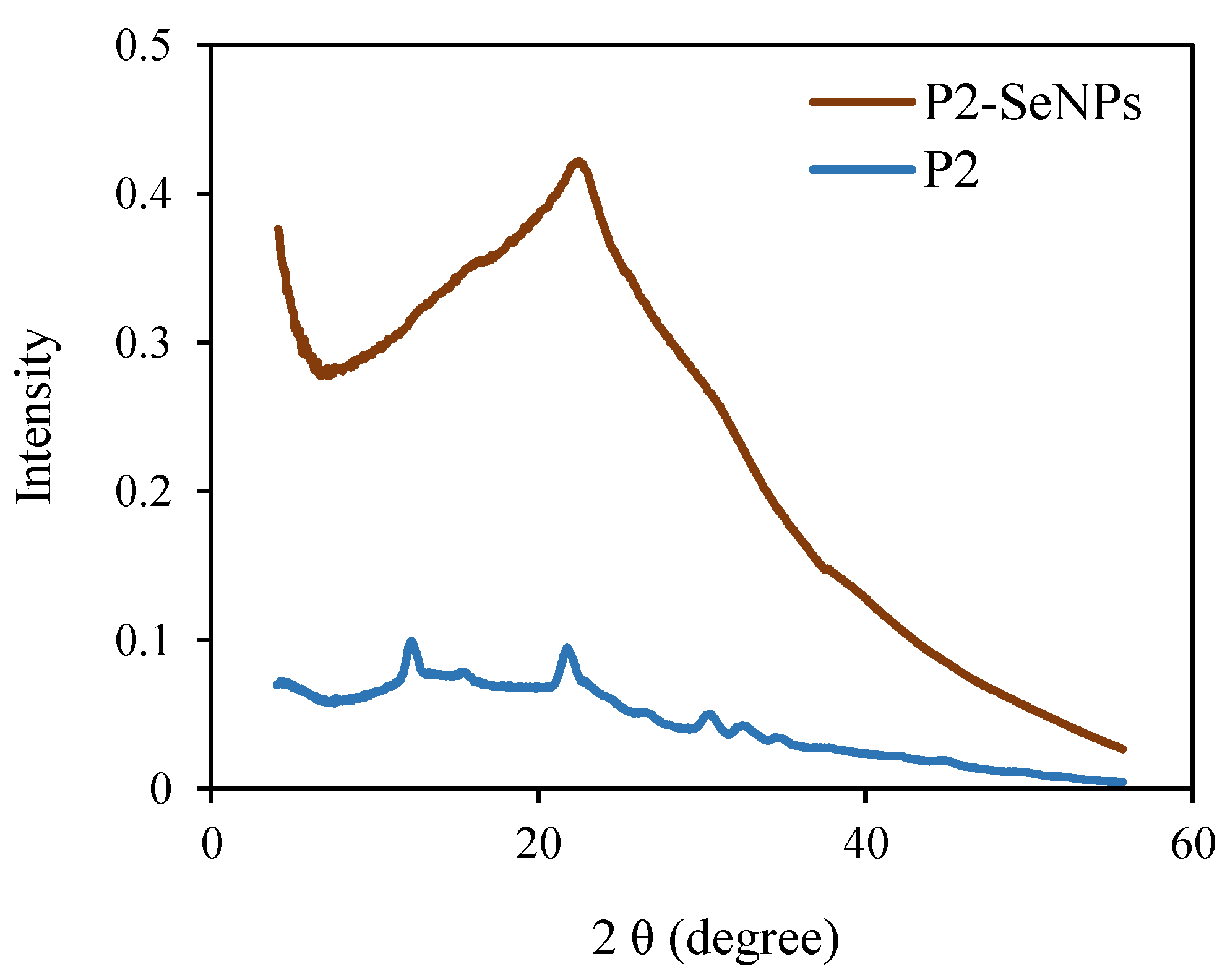

3.3.5. XRD analysis

The XRD spectrum of P2 alone exhibits two low-intensity diffraction peaks at 12.5 and 22.3° (

Figure 7). This indicates that P2 is a semi-crystalline biopolymer. According to the literature, gray selenium has a crystalline structure with diffraction peaks at 2θ = 24° and 30° [

59]. However, in the XRD spectrum of P2-SeNPs, only a broad amorphous halo is observed, indicating that the P2-SeNPs are amorphous. This finding may be attributed to the role of P2, which, as a surface-decorating agent, disrupts the crystallinity of selenium [

59]. Similar results have been reported, showing the amorphous state of SeNPs stabilized by polysaccharides [

60].

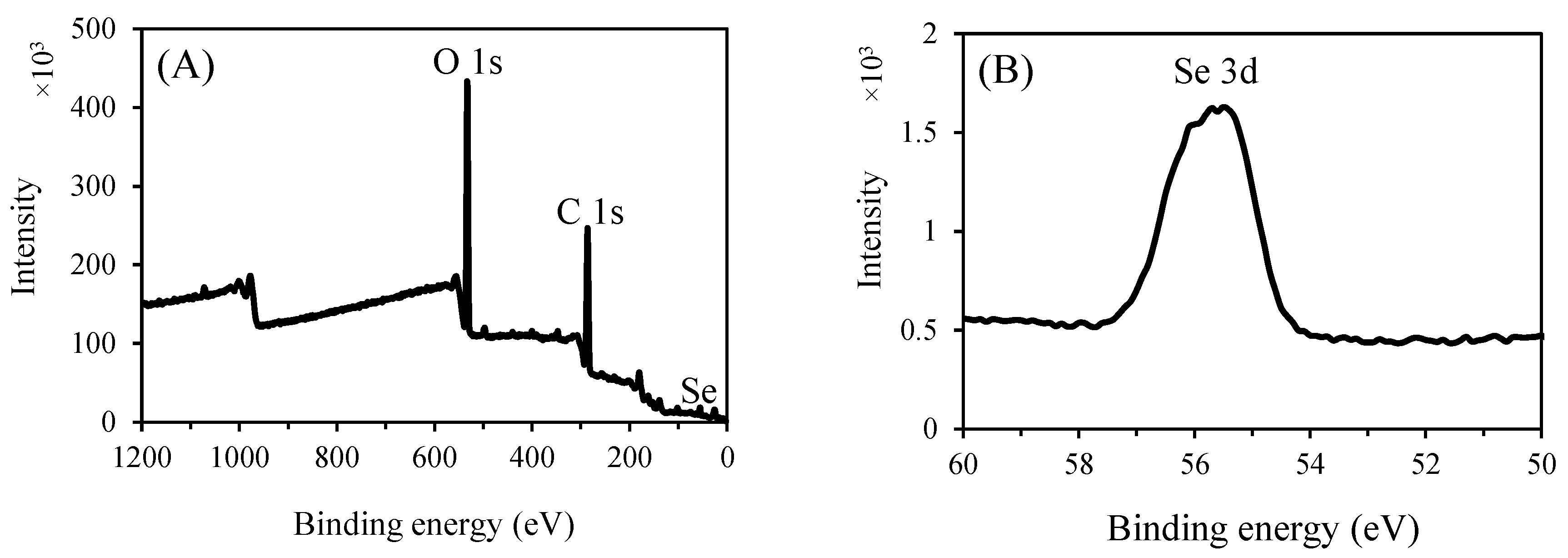

3.3.6. XPS analysis

The amorphous structure and elemental state play a crucial role in the high bioactivity and low cytotoxicity of SeNPs [

61]. XPS spectra were recorded to explore the valence state of selenium in P2-SeNPs. As illustrated in Figure 8A, in addition to the signals from O and C, a typical Se 3d peak is observed in the spectrum of P2-SeNPs. Furthermore, a dominant Se 3d peak at 55.4 eV appears after deconvolution of the high-resolution Se 3d spectrum (Figure 8B), indicating that P2-stabilized SeNPs consist of selenium in the zero-valent state. Moreover, no peak corresponding to Se IV (at 59.1 eV) is detected in the spectrum of P2-SeNPs, In agreement with the absence of Na₂SeO₃ in the final product [

60].

Figure 2.

Wide-range XPS patterns and (A) Se 3d spectra (B) of P2-SeNPs.

Figure 2.

Wide-range XPS patterns and (A) Se 3d spectra (B) of P2-SeNPs.

Based on these findings, the mechanism of the P2-SeNPs formation could be explained as follows: the SeO₃²⁻ precursor is first adsorbed onto P2 chains through electrostatic interactions with the hydroxyl groups, forming a specific chain-like intermediate. Next, SeO₃²⁻ is reduced in situ to Se by ascorbic acid, and then grows to yield P2-SeNPs on which P2 is adsorbed through Se–O bond interactions, preventing the coalescence and agglomeration [

62,

63].

3.4. Stability of P2-SeNPs

The stability of selenium nanoparticles in aqueous solution is a key factor for their biological activity and applications in various fields [

64]. It was evaluated by determining particle size changes under various conditions to elucidate the effects of temperature, storage time, pH, and ionic strength on the stability of P2-SeNPs [

65].

3.4.1. Storage stability

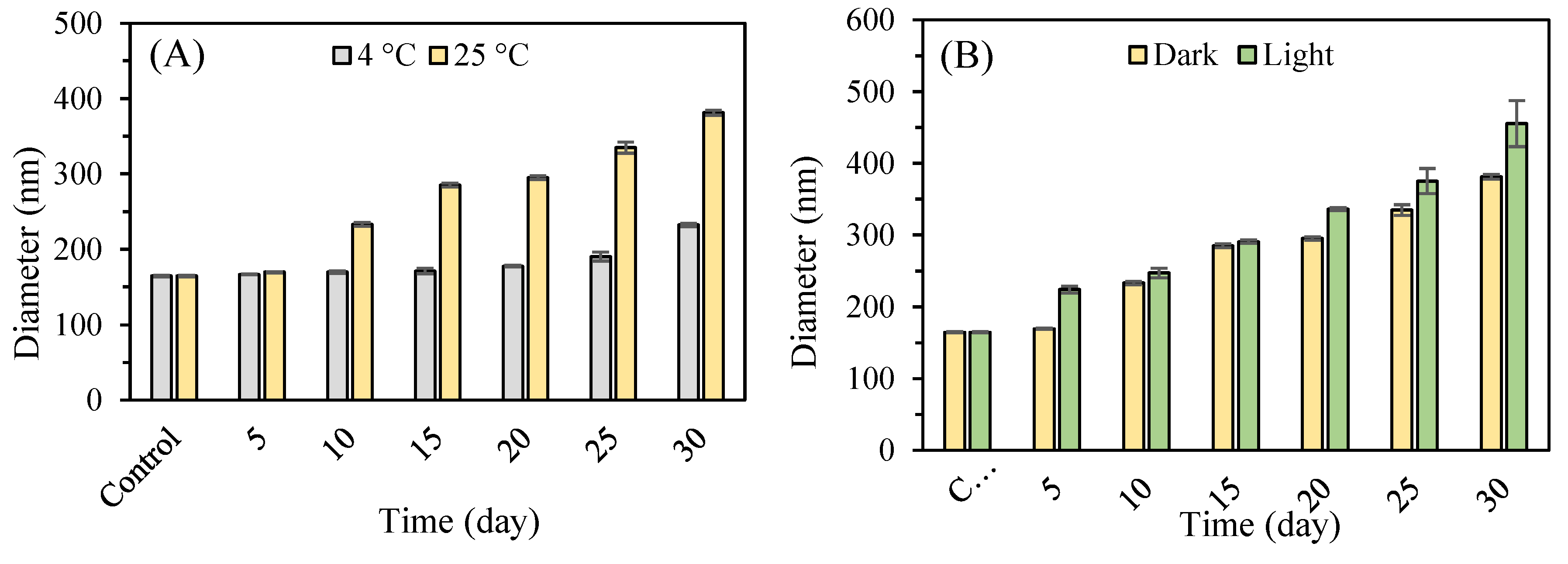

First, the storage time was extended to 30 days to assess the stability of nanoparticles during prolonged storage at 4 °C and 25 °C, in light and darkness.

Figure 9A shows the variation in the average size of P2-SeNPs stored at 4 °C and 25 °C in the dark for 30 days. The initial average diameter of P2-SeNPs is 164.6 ± 1.1 nm. At 4 °C, the average size gradually increases over time, reaching 177.6 ± 1.1 nm et 232.2 ± 2.1 at day 20 and day 30, respectively. At 25 °C, the size increase is more pronounced, with a diameter of 295.2 ± 2.5 nm et 381.2 ± 3.4 at day 20 and day 30, respectively. The significant increase in particle size suggests that higher temperature accelerates the aggregation of nanoparticles, likely due to increased molecular motion and interaction rates.

Figure 9B presents size changes of P2-SeNPs stored at 25 °C in both light and dark conditions for 30 days. In the presence of light, the increase in size is more significant than in the dark, reaching 455.5 ± 32.1 nm at day 30. These results suggest that P2-SeNPs possess good stability at refrigerated temperatures and in darkness, in agreement with the work by Jiang et al. showing that higher temperature has a negative effect on SeNP stability [

66].

3.4.2. Effect of pH and Ionic Strength

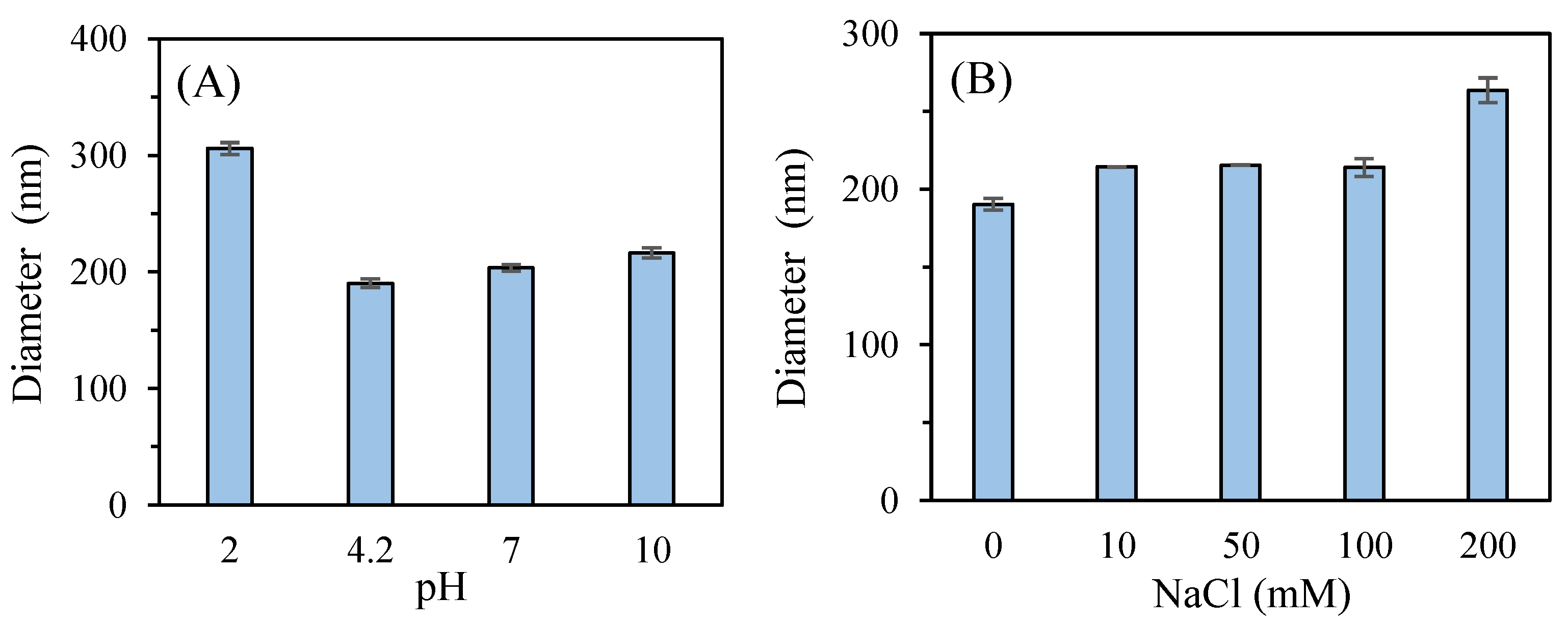

The effect of pH on the stability of P2-SeNPs was studied (

Figure 10A). The freshly prepared P2-SeNPs solution has a pH around 4.2, and the particle size is 190.3 ± 3.7 nm. At pH = 2, the average particle size increases to 305.8 ± 5.1 nm. A low pH may lead to the protonation of functional groups on the polysaccharide chains, reducing electrostatic repulsion and promoting aggregation [

67]. At pH = 7, the size of P2-SeNPs slightly increases to 203.5 ±2.9 nm, suggesting moderate stability at neutral pH. Under basic conditions (pH = 10), the particle size further increases to 216.4 ± 4.3 nm. The deprotonation of functional groups at high pH can also reduce electrostatic stabilization, leading to moderate aggregation. Overall, P2-SeNPs exhibit the best stability near their initial pH of 4.2, with significant destabilization occurring under strongly acidic conditions.

The effect of ionic strength was also considered (

Figure 10B). At low to moderate ionic strengths (10-100 mM NaCl), the particle size slightly increases to 215.5 ± 0.1 nm, suggesting a reasonable stability of P2-SeNPs. In contrast, at high ionic strength (200 mM NaCl), the particle size significantly increases to 263.6 ± 7.9 nm, indicating substantial aggregation. A high ionic strength reduces the electrostatic repulsion between the nanoparticles, thus promoting aggregation.

3.5. Antioxidant Activities of Nanoparticles

The antioxidant activities of SeNPs and P2-SeNPs were evaluated by determining their DPPH radical scavenging activity, ABTS radical scavenging activity, and metal chelation ability. As shown in

Table 2, P2-SeNPs exhibit significantly higher DPPH radical scavenging activity (88.3%), ABTS radical scavenging activity (77.9%), and metal chelation ability (76.7%) compared to those of SeNPs (p<0.05). In fact, the antioxidant capacity of SeNPs depends on the particle size. Smaller particles have a larger specific surface area, which provides a larger number of reactive sites for free radicals [

68]. Additionally, the stability of SeNPs is reported to affect their antioxidant activities [

69], as poor stability leads to aggregation and decrease in the active surface area available for interaction with free radicals. Therefore, both the smaller size and higher stability of P2-SeNPs contribute to their better antioxidant activities as compared to SeNPs.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated the synthesis and stabilization of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) using purified polysaccharide P2 extracted from O. natrix. Characterization techniques confirmed that P2 effectively stabilized SeNPs, as indicated by smaller particle size and reduced aggregation. The interaction between P2 and SeNPs was evidenced by FT-IR, XRD, and XPS analyses. Stability tests showed that P2-SeNPs retained their integrity better than unmodified SeNPs under various storage conditions, including temperature and pH variations. Additionally, P2-SeNPs exhibited enhanced antioxidant activities compared to SeNPs, with higher scavenging abilities against free radicals and improved metal chelation. These findings underscore the potential of P2-SeNPs as a promising material for antioxidant applications in biomedicine, offering a more stable and effective alternative to conventional SeNPs. Future research could further explore the applications of P2-SeNPs in therapeutic and diagnostic contexts, leveraging their enhanced stability and biological activity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.preprint.org, Figure S1: GPC chromatograms of purified polysaccharides P1 and P2; Figure S2: TGA thermograms of purified polysaccharides P1 and P2; Figure S3: Selenium nanoparticles SeNPs and P2-SeNPs freshly prepared (A), lyophilized (B), and stored at 4 °C for 30 Days (C); Figure S4: Size distribution of SeNPs and P2-SeNPs obtained by DLS.

Author Contributions

Nour Bhiri: Writing-original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Suming Li: Review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Nathalie Masquelez: TGA measurements. Moncef Nasri: Validation, Resources, Conceptualization. Mohamed Hajji: Review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the article are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Tunisia, and the European PRIMA project “Valorization of olive stone by-product as a green source of innovative and healthy value-added products in the context of the circular bioeconomy and sustainability”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peer, D.; Karp, J.M.; Hong, S.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Margalit, R.; Langer, R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. In Nano-enabled medical applications. Jenny Stanford Publishing, 2020, pp. 61–91.

- Davis, S.S. Biomédical applications of nanotechnology — implications for drug targeting and gene therapy. Trends in Biotechnology 1997, 15, 217–224. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Tekula, S.; Saifi, M.A.; Venkatesh, P.; Godugu, C. Therapeutic applications of selenium nanoparticles. biomedicine & pharmacotherapy 2019, 111, 802–812. [CrossRef]

- Weeks, M.E. The discovery of the elements. vi. tellurium and selenium. J. Chem. Educ. 1932, 9, 474. [CrossRef]

- Karthik, K.K.; Cheriyan, B.V.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Gopalakrishnan, M. A Review on selenium nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. Biomedical Technology 2024, 6, 61–74. [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.-J.; Xu, Q.-L.; Tang, H.-Y.; Jiang, W.-Y.; Su, D.-X.; He, S.; Zeng, Q.-Z.; Yuan, Y. Development and stability of novel selenium colloidal particles complex with peanut meal peptides. Lwt 2020, 126, 109280. [CrossRef]

- Saurav, K.; Mylenko, M.; Ranglová, K.; Kuta, J.; Ewe, D.; Masojídek, J.; Hrouzek, P. In vitro bioaccessibility of selenoamino acids from selenium (Se)-enriched Chlorella vulgaris biomass in comparison to selenized yeast; a Se-enriched food supplement; and Se-rich foods. Food chem. 2019, 279, 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Li AiChen, L.A.; Fang Lei, F.L. Optimization of Selected parameters affecting selenium content in extracts from Agrocybe cylindracea and anti-fatigue activity of extracts. 2015, 22, 75–80.

- Cao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, J.; Guo, R.; Fan, X.; Bi, Y. Synthesis and evaluation of Grateloupia livida polysaccharides-functionalized selenium nanoparticles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 191, 832–839. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, X.; Lin, H.; Peng, L.; Chen, T. Highly uniform synthesis of selenium nanoparticles with egfr targeting and tumor microenvironment-responsive ability for simultaneous diagnosis and therapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11177–11193. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Li, L.; Feng, L.; Wang, S.; Su, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y. Mitochondrion-targeted selenium nanoparticles enhance reactive oxygen species-mediated cell death. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 1389–1396. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.-K.; Qiu, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, W.-H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.-N. Fabrication and stabilization of biocompatible selenium nanoparticles by Carboxylic curdlans with various molecular properties. Carbohydrate polymers 2018, 179, 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, H.; Bi, Y.; Fan, X. Preparation and Antioxidant activity of selenium nanoparticles decorated by polysaccharides from Sargassum fusiforme. Journal of Food Science 2021, 86, 977–986. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, J.; Mai, F.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Jing, Y.; Dong, X.; Lin, L.; He, J. Selenium nanoparticles as new strategy to potentiate Γδ T cell anti-tumor cytotoxicity through upregulation of tubulin-α acetylation. Biomaterials 2019, 222, 119397. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lin, W.; He, L.; Chen, T. Radiosensitive core/satellite ternary heteronanostructure for multimodal imaging-guided synergistic cancer radiotherapy. Biomaterials 2020, 226, 119545. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-E.; Kim, H.; Seo, C.; Park, T.; Lee, K.B.; Yoo, S.-Y.; Hong, S.-C.; Kim, J.T.; Lee, J. Marine Polysaccharides: Therapeutic efficacy and biomedical applications. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2017, 40, 1006–1020. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tang, Q.; Zhong, X.; Bai, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, W. Surface Decoration by Spirulina polysaccharide enhances the cellular uptake and anticancer efficacy of selenium nanoparticles. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 835–844. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.-Y.; Chen, H.-Y. Synthesis of selenium nanoparticles in the presence of polysaccharides. Materials Letters 2004, 58, 2590–2594. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, M.; Yan, J.-K. Construction, stability, and enhanced antioxidant activity of pectin-decorated selenium nanoparticles. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 170, 692–700. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, G.; Stoll, S.; Ren, F.; Leng, X. Antioxidant capacities of the selenium nanoparticles stabilized by chitosan. J Nanobiotechnol 2017, 15, 4. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Al-Rehaily, A.J.; Ahmad, M.S.; Mustafa, J.; Al-Yahya, M.A.; Al-Said, M.S.; Zhao, J.; Khan, I.A. A 5-alkylresorcinol and three3,4-dihydroisocoumarins derived from Ononis natrix. Phytochemistry Letters 2015, 13, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Bhiri, N.; Hajji, M.; Nasri, R.; Mekki, T.; Nasri, M.; Li, S. Effects of extraction methods on the physicochemical, structural, functional properties and biological activities of extracted polysaccharides from Ononis natrix leaves. Waste Biomass Valor 2024, 15, 5415–5429. [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P. t; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical chemistry 1956, 28, 350–356. [CrossRef]

- Bersuder, P.; Hole, M.; Smith, G. Antioxidants from a heated histidine-glucose model system. i: investigation of the antioxidant role of histidine and isolation of antioxidants by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Amer Oil Chem Soc 1998, 75, 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Carter, P. Spectrophotometric determination of serum iron at the submicrogram level with a new reagent (ferrozine). Analytical Biochemistry 1971, 40, 450–458. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Fang, K.; Yuan, H.; Li, D.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhang, L.; Ye, X. Acid-Induced Poria cocos Alkali-Soluble Polysaccharide Hydrogel: Gelation Behaviour, Characteristics, and Potential Application in Drug Delivery. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 242, 124383. [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Zhu, P.; Ma, S.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y. Purification, characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from Stem lettuce. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 188, 236–242. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yao, H.; Zhou, J.; Duan, Y.; Ma, H. Comparison of characterization, antioxidant and immunological activities of three polysaccharides from Sagittaria sagittifolia L. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 235, 115939. [CrossRef]

- Nan, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, G.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Ding, J.; Yang, J. A Method for the quantitative analysis of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides (LBPs) using fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (ftir): from theoretical computation to experimental application. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2025, 326, 125204. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Fang, C.; Ran, C.; Tan, Y.; Yu, Q.; Kan, J. Comparison of different extraction methods for polysaccharides from bamboo shoots (Chimonobambusa quadrangularis) processing by-products. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 130, 903–914. [CrossRef]

- Olawuyi, I.F.; Kim, S.R.; Hahn, D.; Lee, W.Y. Influences of Combined enzyme-ultrasonic extraction on the physicochemical characteristics and properties of okra polysaccharides. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 100, 105396. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Song, W.; Song, H.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Feng, J. Effects of extraction methods on the physicochemical properties and functionalities of pectic polysaccharides from burdock (Arctium lappa L.). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 257, 128684. [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Cao, S.; Wang, M.; Sun, Y. Optimizing extraction, structural characterization, and in vitro hypoglycemic activity of a novel polysaccharide component from Lentinus edodes. Food Bioscience 2023, 55, 103007. [CrossRef]

- Deore, U.V.; Mahajan, H.S. Isolation and structural characterization of mucilaginous polysaccharides obtained from the seeds of Cassia uniflora for Industrial Application. Food Chem. 2021, 351, 129262. [CrossRef]

- Hentati, F.; Delattre, C.; Ursu, A.V.; Desbrières, J.; Le Cerf, D.; Gardarin, C.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P.; Pierre, G. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity of water-soluble polysaccharides from the tunisian brown seaweed Cystoseira compressa. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 198, 589–600. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; An, L.; Bao, J.; Zhang, J.; Cui, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, D.-Q.; Tuerhong, M.; et al. Isolation, Structural elucidation, and immunoregulation properties of an arabinofuranan from the rinds of Garcinia mangostana. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 246, 116567. [CrossRef]

- Bhotmange, D.U.; Wallenius, J.H.; Singhal, R.S.; Shamekh, S.S. Enzymatic extraction and characterization of polysaccharide from Tuber aestivum. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2017, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Sorourian, R.; Khajehrahimi, A.E.; Tadayoni, M.; Azizi, M.H.; Hojjati, M. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Typha domingensis: structural characterization and functional properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 160, 758–768. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, T.; Jin, Z.-Y.; Xu, X.-M.; Wang, J.-H.; Zha, X.-Q.; Chen, H.-Q. Structural characterisation, physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from Lilium lancifolium Thunb. Food Chem. 2015, 169, 430–438. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. A Novel polysaccharide from the fruits of Cudrania tricuspidata and its antioxidant and alcohol dehydrogenase activating ability. Journal of Functional Foods 2023, 110, 105850. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liang, H.; Wu, Y. Isolation, purification and structural characterization of polysaccharide from Acanthopanax brachypus. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 127, 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Dore, C.M.P.G.; Faustino Alves, M.G.D.C.; Pofírio Will, L.S.E.; Costa, T.G.; Sabry, D.A.; De Souza Rêgo, L.A.R.; Accardo, C.M.; Rocha, H.A.O.; Filgueira, L.G.A.; Leite, E.L. A sulfated polysaccharide, fucans, isolated from brown Algae Ssrgassum Vulgare with anticoagulant, antithrombotic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Carbohydrate Polymers 2013, 91, 467–475. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.-F.; Fu, Y.-P.; Chen, X.-F.; Austarheim, I.; Inngjerdingen, K.; Huang, C.; Eticha, L.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Feng, B.; et al. Purification and partial structural characterization of a complement fixating polysaccharide from rhizomes of Ligusticum chuanxiong. Molecules 2017, 22, 287. [CrossRef]

- Darwish, A.M.G.; Khalifa, R.E.; El Sohaimy, S.A. functional properties of chia seed mucilage supplemented in low fat yoghurt. Alexandria Science Exchange Journal 2018, 39, 450–459. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, F.; Ahmed, Z.; Hussain, S.; Huang, J.-Y.; Ahmad, A. Linum Usitatissimum L. Seeds: flax gum extraction, physicochemical and functional characterization. Carbohydrate polymers 2019, 215, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhou, B.; Liang, Y. A Water-soluble mycelium polysaccharide from Monascus pilosus: extraction, structural characterization, immunomodulatory effect and yield enhanced by overexpression of uge gene. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 280, 136138. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, B.; Nie, S.; Duan, Z.; Chen, K. A Combination of Selenium and polysaccharides: promising therapeutic potential. Carbohydrate polymers 2019, 206, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, L.; Liu, W.; Fan, C.; Zheng, W.; Wong, Y.-S.; Chen, T. Selective cellular uptake and induction of apoptosis of cancer-targeted selenium nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 7106–7116. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Schmidt, M. Pitfalls and Novel applications of particle sizing by dynamic light scattering. Biomaterials 2016, 98, 79–91. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Song, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Guo, Y. Construction and antitumor activity of selenium nanoparticles decorated with the polysaccharide extracted from Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. (Rutaceae). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 188, 904–913. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, X.; Mu, J.; Ho, C.-T.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, B.; Xie, Y. Preparation, physicochemical characterization, and anti-proliferation of selenium nanoparticles stabilized by Polyporus umbellatus polysaccharide. International journal of biological macromolecules 2020, 152, 605–615. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, S.; Wang, L.; Bai, J.; Yang, Y. Preparation of Ribes nigrum L. polysaccharides-stabilized selenium nanoparticles for enhancement of the anti-glycation and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 127122. [CrossRef]

- Wagoner, T.B.; Foegeding, E.A. Whey Protein–pectin soluble complexes for beverage Applications. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 63, 130–138. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Ha, H.D.; Dahl, J.C.; Ondry, J.C.; Moreno-Hernandez, I.; Head-Gordon, T.; Alivisatos, A.P. AutoDetect-mNP: An unsupervised machine learning algorithm for automated analysis of transmission electron microscope images of metal nanoparticles. JACS Au 2021, 1, 316–327. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Zhao, J.; Luk, K.-H.; Cheung, S.-T.; Wong, K.-H.; Chen, T. Potentiation of in vivo anticancer efficacy of selenium nanoparticles by mushroom polysaccharides surface decoration. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2865–2876. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, C.; Huang, Q.; Fu, X. Biofunctionalization of Selenium nanoparticles with a polysaccharide from Rosa roxburghii Fruit and their protective effect against H2O2-Induced apoptosis in INS-1 Cells. Food & function 2019, 10, 539–553. [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.; Esakkiraj, P.; Annamalai, A.; Lakra, A.K.; Naik, S.; Arul, V. Synthesis, Optimization, and Physicochemical characterization of selenium nanoparticles from polysaccharide of Mangrove rhizophora Mucronata with potential bioactivities. Journal of Trace Elements and Minerals 2022, 2, 100019. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, T.; Chen, H.; Yu, Q.; Yan, C. Structural characterization and osteogenic activity in vitro of novel polysaccharides from the rhizome of Polygonatum sibiricum. Food & Function 2021, 12, 6626–6636d osteogenic activity in vitro of novel polysaccharides from the rhizome of Polygonatum sibiricum. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Guan, H.; Liu, S. Construction of a Cordyceps sinensis exopolysaccharide-conjugated selenium nanoparticles and enhancement of their antioxidant activities. International journal of biological macromolecules 2017, 99, 483–491. [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Kong, F.; Bi, Y. Synthesis, characterization, in vitro antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of selenium nanoparticles decorated with polysaccharides of Gracilaria lemaneiformis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 193, 923–932. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Mu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, W.; Luo, Y.; Li, B. Stabilization and functionalization of selenium nanoparticles mediated by green tea and pu-erh tea polysaccharides. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 194, 116312. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Qiu, W.-Y.; Sun, L.; Ding, Z.-C.; Yan, J.-K. Preparation, characterization, and antioxidant capacities of selenium nanoparticles stabilized using polysaccharide–protein complexes from Corbicula fluminea. Food bioscience 2018, 26, 177–184.

- ia, X.; Liu, Q.; Zou, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, L. Construction of Selenium nanoparticles/β-glucan composites for enhancement of the antitumor activity. Carbohydrate polymers 2015, 117, 434–442. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xiong, C.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; Wen, Q.; Tang, H.; Zeng, Q.; Feng, Y.; Li, J. Tuning self-assembly of amphiphilic sodium alginate-decorated selenium nanoparticle surfactants for antioxidant pickering emulsion. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 210, 600–613. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, D.; Zhang, Z. Structural Properties, Antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of polysaccharides purified from pepper leaves by high-speed counter-current chromatography. Journal of Functional Foods 2022, 89, 104916. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, R.; Zhou, F.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Huo, G.; Ye, J.; Hua, C.; Wang, Z. Preparation, physicochemical characterization, and cytotoxicity of selenium nanoparticles stabilized by Oudemansiella raphanipies Polysaccharide. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 211, 35–46. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Wang, T.; Hu, Q.; Luo, Y. Caseinate-zein-polysaccharide complex nanoparticles as potential oral delivery vehicles for curcumin: effect of polysaccharide type and chemical cross-linking. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 72, 254–262. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Lin, Z.; Hou, J.; Liu, W.; Xu, J.; Guo, Y. Purification and Characterization of a chicory polysaccharide and its application in stabilizing genistein for cancer therapy. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 242, 124635. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Hu, T.; Bakry, A.M.; Zheng, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, Q. Effect of Ultrasound on size, morphology, stability and antioxidant activity of selenium nanoparticles dispersed by a hyperbranched polysaccharide from Lignosus rhinocerotis. Ultrasonics sonochemistry 2018, 42, 823–831. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).