1. Introduction

Cancer pain remains one of the most prevalent, burdensome, and clinically challenging symptoms experienced by patients with malignancy, affecting an estimated 55–95% of individuals at advanced stages of disease [

1,

2]. Contemporary epidemiological data indicate that approximately two-thirds of patients with metastatic cancer experience moderate to severe pain despite advances in systemic therapies and supportive care, underscoring its persistent global impact on quality of life, functional capacity, and psychological well-being [

3]. The burden extends far beyond individual suffering. Uncontrolled cancer pain is associated with reduced longevity, increased healthcare utilization, reduced adherence to anticancer treatments, and substantial socioeconomic costs [

4].

From a mechanistic standpoint, cancer pain is now widely recognized as a prototypical form of mixed pain, where nociceptive, neuropathic, and, in a subset of patients, nociplastic mechanisms coexist [

5]. The recognition of this mechanistic heterogeneity has emerged from recent advances in neurobiology, oncology, and immunology [

6]. Tumor-neuron interactions have gained prominence, with studies demonstrating that malignant cells actively recruit and remodel neural pathways through neurotrophic factors, axonogenesis, and synaptic-like communication, thereby amplifying nociceptive transmission [

7,

8,

9]. Parallel discoveries in neuroimmune crosstalk reveal that cytokines, chemokines, and glial activation contribute to sustained peripheral and central sensitization, shaping the transition from acute to chronic cancer pain [

10,

11].

Management strategies continue to evolve. International guidelines and recent updates reaffirm the WHO analgesic ladder, with paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as the foundation for mild pain and analgesics such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants at all levels, used alone or in combination with opioids when appropriate [

12]. Despite limited high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence, NSAIDs remain widely used, particularly for bone and inflammatory components of cancer pain, often in combination with opioids, with careful consideration of gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular risks and gastroprotection when indicated [

13]. Opioids remain the cornerstone for moderate–severe cancer pain, endorsed by major societies such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [

14]. However, their use is increasingly framed within precision prescribing and opioid-sparing multimodal strategies, integrating adjuvant analgesics, interventional procedures, and supportive measures. At the same time, digital health and telemedicine solutions, ranging from telemonitoring systems to structured pain self-management apps, are emerging as tools to improve assessment, adherence, and timely titration of analgesic regimens [

15].

In this context of rapidly expanding mechanistic insight and therapeutic innovation, there is a clear need to synthesize recent advances in the pathophysiology and management of cancer pain, with particular emphasis on mixed-pain mechanisms, rational use of analgesics (RUA) (NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, antidepressants and opioids), adjuvant and interventional approaches, and the integration of digital technologies into patient-centered care.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design

This study was conducted as a scoping review to systematically map recent evidence on mechanisms and management strategies for cancer-related pain. The methodology followed the framework originally proposed by Arksey and O’Malley and further refined by Levac et al. [

16] and adhered to updated Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodological guidance for scoping reviews. Reporting follows the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

17].

Research question

The overarching research question was: “How have biological mechanisms, pharmacological strategies, interventional and neuromodulatory procedures, radiotherapy, and digital/AI-enabled tools been investigated and applied in the management of cancer-related pain between 1 January 2022 and 30 September 2025?”

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were defined a priori using the Population–Concept–Context (PCC) framework recommended by JBI. The population of interest included adults (≥18 years) experiencing cancer-related pain of any etiology (e.g., tumor-related, treatment-related, or mixed) across oncology, survivorship, and palliative-care settings. The concept encompassed a broad range of domains, including biological and neuroimmune mechanisms of cancer pain; pharmacological management with non-opioid analgesics, opioids, and adjuvant medications; interventional and neuromodulatory techniques such as nerve blocks, intrathecal therapies, spinal cord stimulation (SCS), dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRGS), and peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS); radiotherapy approaches for pain palliation (e.g., cEBRT, SBRT, stereotactic modalities); and digital health solutions including remote monitoring, mobile health, wearables, and AI/ML or NLP applications for cancer-pain assessment, prediction, or management. The context included any healthcare setting, hospital, outpatient, home-based, or hospice, across all countries. Eligible evidence sources comprised primary quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies; secondary evidence such as systematic or scoping reviews; clinical practice guidelines; and high-quality observational cohorts or registries. Narrative commentaries and editorials were included only when they offered meaningful conceptual or mechanistic insights.

The review included articles published between 1 January 2022 and 30 September 2025, limited to the English language. Exclusion criteria were case reports or case series with fewer than five patients, conference abstracts without full text, non-human preclinical studies unless directly relevant to clinically applicable cancer-pain mechanisms, and articles in which pain was not a primary or explicitly analyzed outcome. Four electronic databases were analyzed: PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection, supplemented by manual citation tracking of key reviews and guidelines. The final search was run on November 20, 2025.

Search strategy

Search strategies were developed iteratively with reference to JBI guidance and the PRISMA-ScR explanation and elaboration paper [

17]. For PubMed, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were combined with free-text terms related to cancer, pain, and each of the domains. The PubMed strategy was: ((“Neoplasms”[MeSH] OR neoplasm*[tiab] OR cancer*[tiab] OR malignan*[tiab] OR tumor*[tiab] OR tumour*[tiab]) AND (“Pain”[MeSH] OR “Pain Management”[MeSH] OR pain[tiab] OR analgesia[tiab] OR “cancer pain”[tiab])) AND (mechanis*[tiab] OR neuroimmune[tiab] OR “nerve sprouting”[tiab] OR “tumor-nerve”[tiab] OR opioid*[tiab] OR NSAID*[tiab] OR ibuprofen[tiab] OR adjuvant*[tiab] OR gabapentin*[tiab] OR duloxetine[tiab] OR “nerve block*”[tiab] OR “intrathecal”[tiab] OR “spinal cord stimulation”[tiab] OR “dorsal root ganglion”[tiab] OR “peripheral nerve stimulation”[tiab] OR “Radiotherapy”[MeSH] OR radiotherap*[tiab] OR “stereotactic body radiotherapy”[tiab] OR SBRT[tiab] OR “palliative radiotherapy”[tiab] OR “Telemedicine”[MeSH] OR “Mobile Applications”[MeSH] OR telemedicine[tiab] OR telehealth[tiab] OR “mobile app*”[tiab] OR mHealth[tiab] OR “Artificial Intelligence”[MeSH] OR “machine learning”[tiab] OR “natural language processing”[tiab] OR “clinical decision support”[tiab]) AND (“2022/01/01”[Date - Publication]: “2025/09/30” [Date - Publication]). For Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science, the strategy was translated using database-specific subject headings (e.g., Emtree terms for Embase) and proximity operators (e.g., cancer* NEXT/3 pain*) while preserving the same core concepts (cancer, pain, mechanisms, pharmacology, interventions, radiotherapy, digital/AI). Search results from all databases were exported into a reference-management software and de-duplicated. Title and abstract screening were performed independently by two reviewers (YVT, PVP) against the eligibility criteria. Potentially relevant records were retrieved in full text and assessed independently by the same reviewers. Discrepancies at either stage were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

3. Results

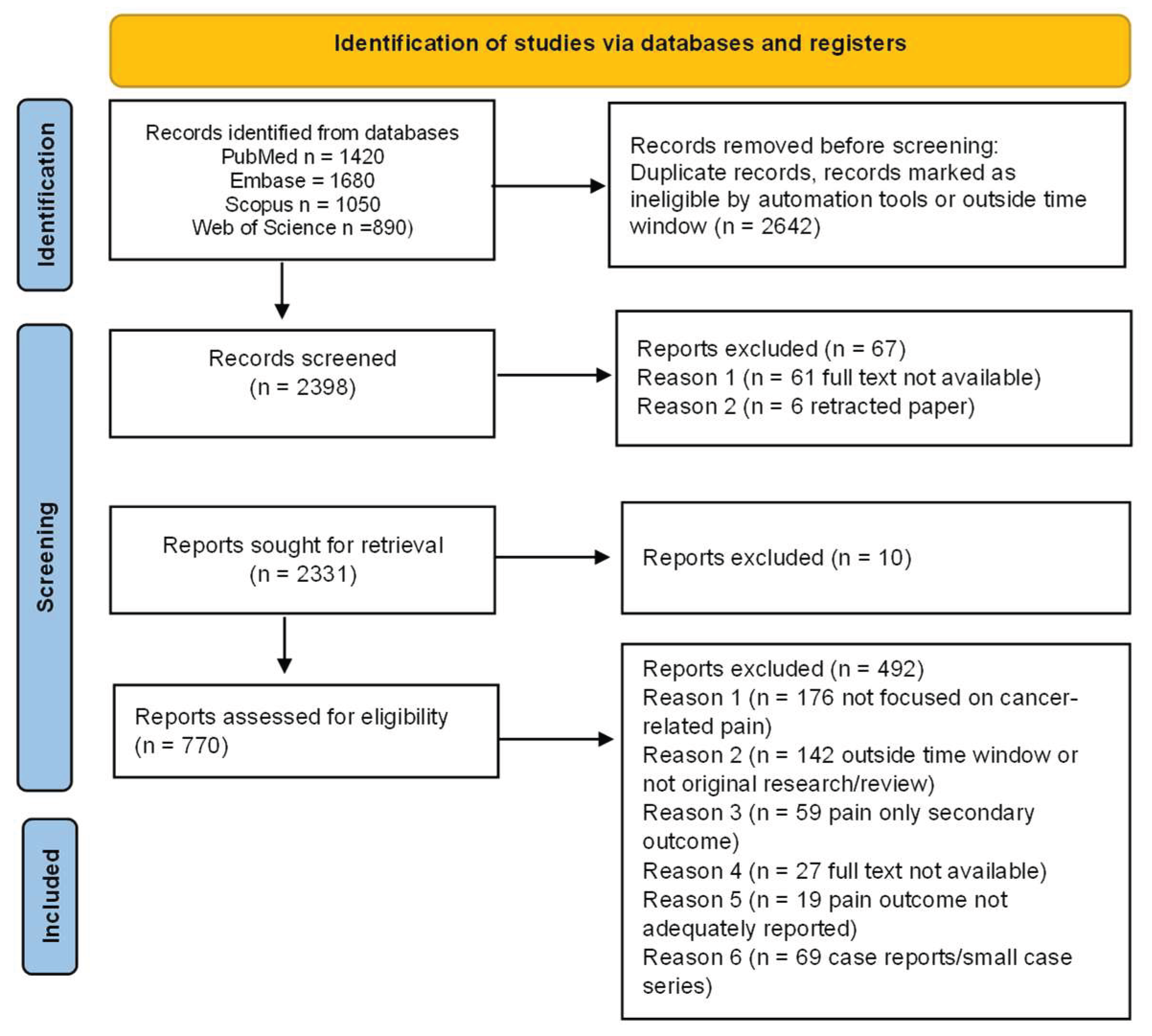

The literature search identified a substantial body of contemporary evidence across cancer pain mechanisms and management. After screening for relevance and methodological rigor, the final selection comprised recent mechanistic studies, clinical trials, meta-analyses, interventional innovations, and technology-driven approaches suitable for qualitative synthesis. The comprehensive search across PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science retrieved 5,040 records. After removing 1,628 duplicates, 3,412 records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 2,642 records were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria. The full text of 770 articles was assessed for eligibility, and 492 were excluded for reasons including lack of focus on cancer-related pain, being outside the time window or not original research, pain not reported as a primary or separable outcome, or being case reports, very small series, or abstracts only. Ultimately, 278 studies were included in the scoping review (

Figure 1).

The qualitative analysis of the extracted literature revealed several coherent thematic groups reflecting the current evolution of cancer pain science. The first encompassed advances in biological mechanisms, including tumor-neuron interactions, neuroimmune activation, and sensitization processes. A second group comprised studies on pharmacological management, covering NSAIDs, opioids, antineuropathic agents, and emerging targeted analgesics. A third group focused on interventional and neuromodulatory approaches, detailing procedural innovations and device-based therapies. A fourth group captured radiotherapy developments relevant to painful metastases. Finally, an expanding body of work addressed digital health, remote monitoring, and AI-enabled tools, highlighting their growing integration into cancer pain assessment and personalized management.

3.1. Advances in Biological Mechanisms

Recent investigations have substantially advanced our understanding of the molecular and cellular processes underlying cancer-related pain, refining the concept of tumor–neuronal and neuroimmune crosstalk. First, the role of tumor-nerve interactions has become increasingly evident: malignant cells release neurotrophic factors such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and guidance cues (e.g., semaphorins, netrins) that stimulate axonal sprouting and afferent sensitization within the tumor microenvironment [

18]. This nerve infiltration is directly implicated in pain genesis and correlates with disease aggressiveness [

19,

20].

Concurrently, neuroimmune signaling has emerged as a pivotal mechanism: activated nociceptors secrete neuropeptides like CGRP and substance P, which in turn modulate immune-cell function and perpetuate inflammatory signaling both peripherally and centrally [

21]. For instance, recent data show that sensory neurons within the tumor milieu drive immune suppression and nociceptive sensitization through chemokine and cytokine networks [

22]. Moreover, sensitization processes at both peripheral and central levels are being better understood in cancer pain [

23]. At the periphery, tumor-secreted algogens, including prostaglandins, endothelin-1, glutamate, and protons, activate TRP and acid-sensing ion channels on nociceptors, thereby amplifying afferent input [

22]. At the central nervous system, persistent afferent barrage heightens dorsal-horn glial activation and chemokine signaling, resulting in synaptic facilitation and diminished inhibitory control [

24].

Emerging research has identified substantial inter-individual variability in cancer pain susceptibility and analgesic response, partially attributable to genetic polymorphisms and epigenetic modifications [

25]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding opioid receptors (OPRM1, OPRD1, OPRK1), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), and voltage-gated sodium channels (SCN9A, SCN10A) have been associated with differential pain sensitivity and opioid dose requirements in cancer populations [

26]. Beyond genetics, epigenetic alterations including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA dysregulation contribute to persistent pain states in cancer [

27]. Hypermethylation of genes regulating endogenous opioid production or inhibitory neurotransmission may diminish descending pain modulation, while histone deacetylase activity influences transcription of pro-nociceptive mediators [

28].

The tumor microenvironment (TME) represents a complex ecosystem where malignant cells, immune infiltrates, stromal components, and neural elements engage in reciprocal signaling that amplifies pain [

29]. Acidosis within the TME, resulting from dysregulated tumor metabolism and hypoxia, activates acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) on nociceptors, generating sustained afferent barrage [

30]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells release not only classical inflammatory cytokines but also specialized pro-algesic lipid mediators including lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine-1-phosphate [

31]. Matrix metalloproteinases secreted by tumor and stromal cells liberate bioactive fragments from extracellular matrix proteins, further activating nociceptive pathways [

24]. In bone metastases, osteoclast-mediated bone resorption releases protons, adenosine triphosphate and matrix-embedded growth factors that collectively activate periosteal and bone marrow nociceptors [

32]. Nerve growth factor (NGF) is particularly abundant in metastatic bone lesions and binds to tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA) on nociceptors, driving neuronal sensitization, sprouting, and phenotypic changes [

33].

Collectively, these mechanistic insights recast cancer pain as a disorder of aberrant tumor-nerve-immune signaling, rather than merely a consequence of tissue injury, nerve compression and iatrogenic toxicity. Understanding this multi-layered interaction framework will be essential for translating mechanistic discoveries into more targeted and effective analgesic strategies [

29].

3.2. Pharmacological Management

Pharmacological management of cancer-related pain must be grounded in mechanism-based analgesia and tailored to the mixed-pain profile typical of malignancy. Central to this strategy is the rational use of non-opioid analgesics, opioids, and adjuvant agents within a multimodal framework [

12]. Non-opioid analgesics (e.g., paracetamol and NSAIDs) retain foundational status for mild to moderate pain and as adjuncts for more severe syndromes. Ibuprofen exemplifies this class: although robust randomized controlled data in cancer pain remain scarce, clinical practice surveys indicate ibuprofen is the oral NSAID of choice in approximately 42.6% of UK palliative-care respondents [

34]. Moreover, cancer-care algorithms list ibuprofen alongside other NSAIDs as first-line non-opioids in adult cancer pain management [

35]. The theoretical basis for NSAIDs in cancer pain lies in modulation of cyclooxygenase (COX)-mediated prostaglandin synthesis and tumor-microenvironment inflammation, which may contribute to nociceptor activation and sensitization [

36]. In prescribing ibuprofen or any alternative NSAID in the cancer-pain setting, clinicians must carefully balance risk and benefit: gastrointestinal bleeding, renal impairment, platelet dysfunction, and chemotherapy-related thrombocytopenia are critical considerations. Guidelines emphasize caution in thrombocytopenic, renal-insufficient, or peri-operative oncology patients [

37]. Evolving evidence suggests that NSAIDs might also impact oncologic outcomes (e.g., improved survival associations with ibuprofen in observational cohorts) which raises the possibility of dual analgesic and disease-modifying benefit in selected settings [

38]. However, high-quality analgesic trials of NSAIDs specifically in malignant pain remain absent; thus, they are best viewed as adjunctive rather than monotherapy in moderate to severe pain.

For moderate to severe cancer pain, µ-opioid agonists remain the backbone of therapy. Recent synthesized data on background nociceptive cancer pain has confirmed that appropriate opioid titration, rotation, and monitoring are essential to optimize analgesia and minimize adverse events [

37]. In this context, NSAIDs such as ibuprofen may offer an opioid-sparing effect when combined with opioids, though formal cancer-pain trials are lacking [

34]. Adjuvant analgesics (e.g., gabapentinoids, serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, corticosteroids, bisphosphonates, and RANKL inhibitors) can be applied based on pain phenotype (e.g., neuropathic, bone-metastasis, inflammatory) and mechanistic insight [

39,

40].

3.3. Interventional and Neuromodulatory Approaches

In recent years, the management of cancer-related pain has increasingly incorporated interventional and neuromodulatory therapies, thereby extending beyond strictly pharmacological approaches. According to a 2023 scoping review, procedures such as intrathecal drug delivery systems (IDDS), percutaneous neurolytic blocks, vertebral augmentation (e.g., kyphoplasty/vertebroplasty), and minimally-invasive neurosurgical interventions (e.g., cordotomy or dorsal-root entry zone [DREZ] lesioning) have gained prominence in oncologic pain settings [

41]. These modalities offer both rapid analgesia and a potential opioid-sparing effect in patients with refractory pain or anatomical pain drivers [

42]. Neuromodulation, specifically epidural SCS, DRGS and PNS, has emerged as a viable option for selected patients experiencing focal neuropathic or mixed pain syndromes in the context of malignancy [

43,

44]. For example, recent work indicates meaningful pain relief and improved functional outcomes in cancer-pain cohorts treated with SCS/DRGS [

45]. In contrast, neuroablative neurosurgery remains a niche yet important component when pain is overwhelmingly refractory and life expectancy limited. In this regard, interventions such as cordotomy, cingulotomy, and DREZ lesioning have demonstrated analgesic benefit in case series of end-stage malignancy pain [

46]. Selection criteria are stringent: interventions are reserved for individuals with confirmed pain pathway targets, minimal survival prognosis, and absence of alternative options, given their irreversible nature and risk-to-benefit ratio.

Together, interventional and neuromodulatory techniques represent a mechanistically informed extension of cancer-pain management, targeting anatomical, neurophysiological, and neuropathic drivers of pain. Critical factors for success include precise pain phenotype identification, interdisciplinary collaboration (oncology, pain, neurosurgery), procedural timing relative to disease course, and coordination with systemic and adjuvant therapies. As the evidence base grows, these modalities are increasingly viewed not as last-resort options, but as integral components of personalized, advanced analgesic care in oncology [

47].

3.4. Radiotherapy Developments

Recent years have witnessed significant refinements in radiotherapy for cancer-related pain, particularly in the context of painful bone metastases [

48]. Conventional external beam radiotherapy (cEBRT) continues to provide reliable palliation: a recent review reported pain-response rates of approximately 60-70% and complete relief in about 23-34% of treated cases [

49]. Moreover, updated analyses show that both single- and multiple-fraction regimens yield equivalent overall response, although single-fraction treatments are associated with higher retreatment rates [

50]. Advancing beyond conventional schedules, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) has gained increasing attention. A recent meta-analysis of eight randomized clinical trials (1,090 patients) demonstrated that overall pain responses were comparable between SBRT and cEBRT. However, SBRT achieved significantly higher rates of complete pain relief at 1, 3 and 6 months (relative risk ranging from 1.4 to 2.5) [

51]. These findings suggest that SBRT may confer superior durability of analgesia in selected patients, particularly those with oligometastatic disease or radioresistant histologies [

50]. In parallel, there is growing emphasis on predictive modelling to personalize radiotherapy for pain relief. For example, a 2024 study developed a prognostic model integrating clinical parameters (primary tumor type, extent of metastases, steroid use) to stratify response likelihood in bone-metastasis patients undergoing palliative radiotherapy [

52].

While radiotherapy primarily targets tumor and inflammatory mechanisms of skeletal pain, recent publications have also explored its mechanistic underpinnings: the analgesic effect may stem from modulation of periosteal nociceptor activity, reduction of tumor-induced osteolysis, suppression of inflammatory factors, and disruption of tumor-nerve crosstalk rather than mere mechanical stabilization [

49]. Nonetheless, several open questions remain, e.g., optimal dose-fractionation schemes for complex or spinal lesions, timing of re-irradiation, integration with systemic analgesic regimens, and selection criteria for SBRT in routine pain-management algorithms. The recent update emphasizes the need for further high-quality trials to clarify dose, modality, and patient-selection variables [

50].

Briefly, radiotherapy for cancer pain is evolving from standard palliation toward more precise, mechanism-based analgesic interventions. Its integration within multimodal pain management, including pharmacologic, interventional, and neuromodulatory strategies, positions it as a cornerstone of advanced cancer-pain care [

53], even if with still some cautions [

54].

3.5. Digital Health, Remote Monitoring, and AI-Enabled Tools

Digital health technologies have increasingly been integrated into cancer-pain management, reflecting a broader shift toward precision oncology and continuous symptom monitoring [

55]. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of remote-care platforms, and subsequent evidence demonstrates that digital tools can enhance pain assessment, treatment adherence, and clinical decision-making for individuals living with cancer-related pain [

56,

57]. Recent reviews have highlighted that digital interventions, including mobile applications, telemedicine platforms and wearable sensors, improve patient-reported pain outcomes, facilitate timely clinician intervention, and reduce unplanned healthcare use [

58,

59].

Mobile health (mHealth) systems have shown promises. For example, a controlled study evaluating a digital oncology pain-management platform reported significant reductions in pain intensity and distress, alongside improved self-management competence [

60].

Remote monitoring platforms have also expanded the reach of palliative care. In a further review, telemedicine-based pain services demonstrated feasibility, high patient satisfaction, and comparable analgesic outcomes to in-person visits, particularly valuable for advanced cancer patients with limited mobility or in geographically underserved regions [

61].

Wearable-sensor technologies represent an emerging frontier. A 2024 study demonstrated that continuous digital measurement of actigraphy-derived mobility indices correlates with fluctuations in cancer-pain severity, enabling dynamic monitoring and early detection of symptom escalation [

62].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly incorporated into cancer-pain research and clinical management, particularly in the areas of pain prediction, phenotyping, and treatment optimization [

58,

63]. Machine-learning models have demonstrated the ability to integrate clinical, demographic, and patient-reported data to forecast clinically significant pain crises [

64]. A 2023 study developed and validated a predictive model for severe cancer pain flares, achieving high discrimination accuracy and illustrating the potential of AI to support anticipatory, pre-emptive analgesic strategies [

65].

Complementing these approaches, natural-language processing (NLP) methods have been applied to extract pain descriptors, severity scores, and temporal patterns from electronic health records [

66]. This has been shown to improve the precision, completeness, and timeliness of pain assessment in oncology populations, offering scalable solutions for automated monitoring and clinical decision support [

67]. Together, these developments signify a transition from episodic, clinic-based pain evaluation toward continuous, data-driven, personalized cancer-pain management. AI-enabled platforms enhance patient engagement, facilitate remote symptom monitoring, and open avenues for individualized prediction models that align analgesic interventions with dynamic patient needs [

68].

Nevertheless, significant implementation challenges remain, including variation in digital literacy, interoperability and data-integration limitations, privacy and security concerns, and persistent disparities in access to digital health tools [

69]. Addressing these barriers will be essential to ensure that AI-enabled cancer-pain management strategies are equitably integrated into routine oncology and palliative-care workflows, and to support future large-scale clinical validation.

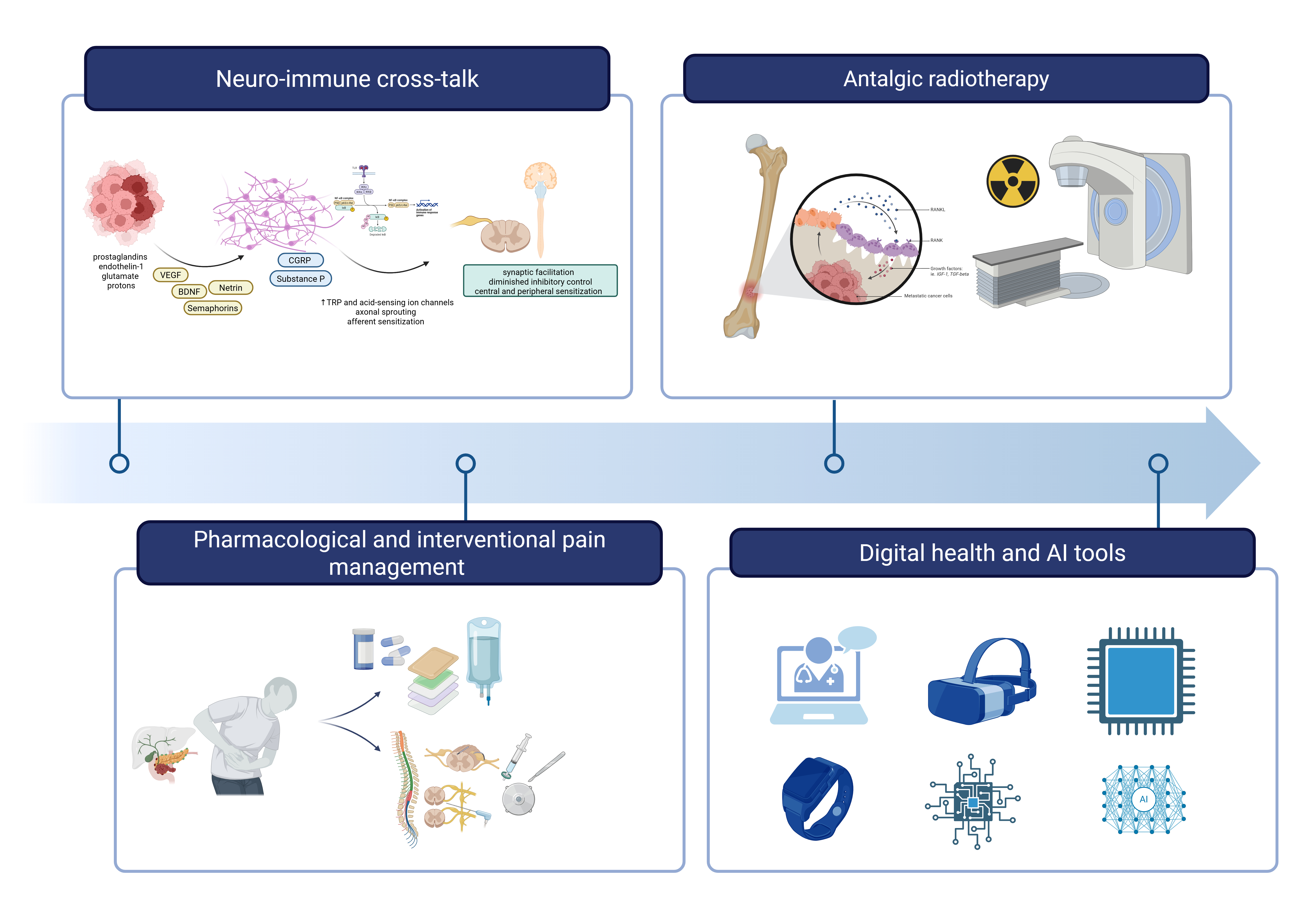

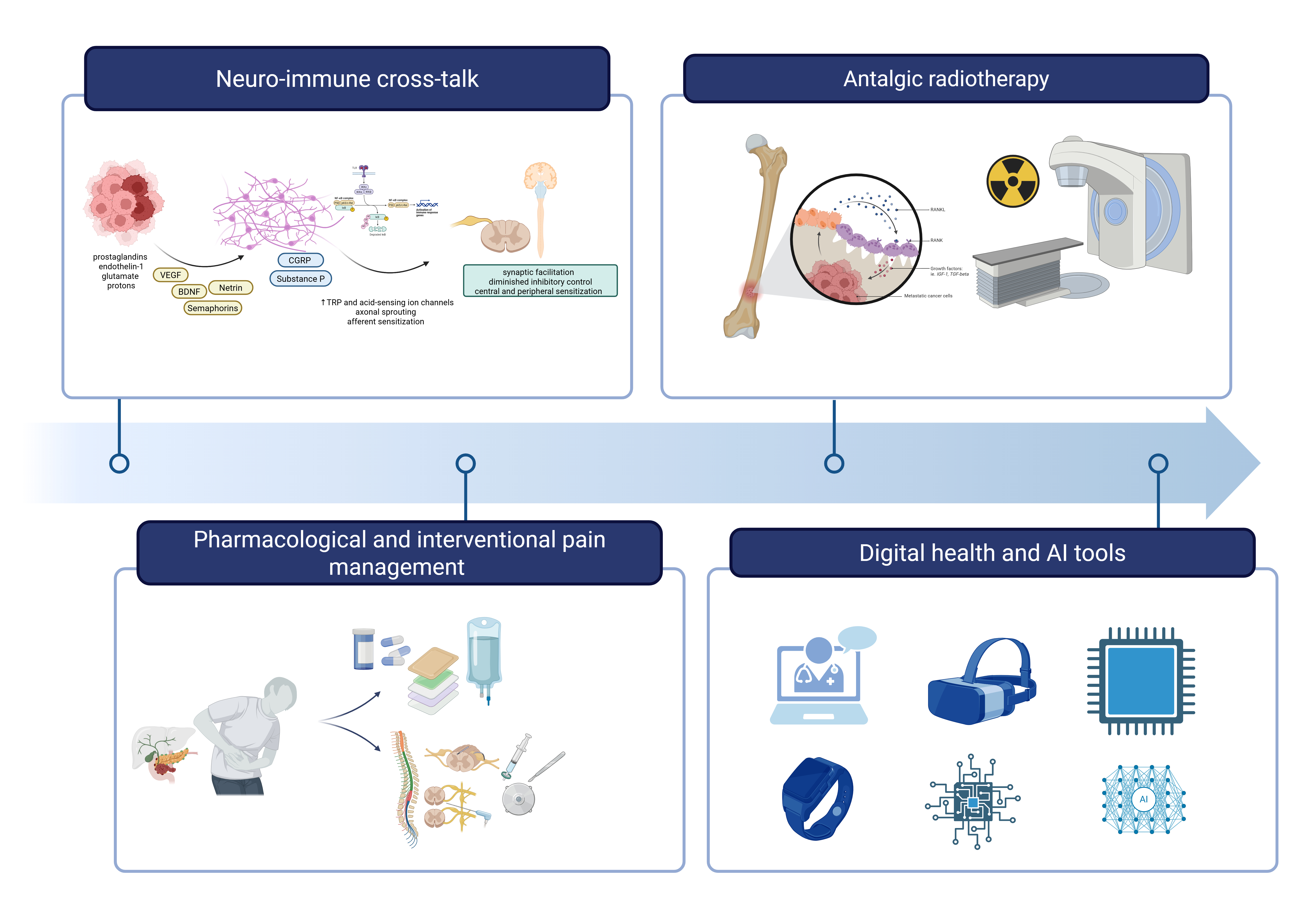

Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the contemporary multimodal approach to cancer pain management, integrating mechanistic insights with therapeutic innovations across four key domains.

Figure 2.

Integrated framework for contemporary cancer pain management. The figure illustrates four interconnected domains that constitute the modern approach to cancer-related pain: (1) Neuro-immune cross-talk, depicting the complex interactions between tumor cells, immune mediators, sensory neurons, and central sensitization pathways that drive pain pathogenesis; (2) Pharmacological and interventional pain management, encompassing non-opioid and opioid analgesics, adjuvant medications, nerve blocks, intrathecal delivery systems, and neuromodulation techniques; (3) Analgesic radiotherapy, showing targeted radiation delivery to painful bone metastases; and (4) Digital health and AI tools, representing emerging technologies including telemedicine platforms, wearable sensors, mobile applications, and artificial intelligence-enabled predictive models for continuous pain assessment and personalized treatment optimization. This integrated approach reflects the transition from empirical symptom management toward mechanism-based precision medicine in cancer pain care.

Figure 2.

Integrated framework for contemporary cancer pain management. The figure illustrates four interconnected domains that constitute the modern approach to cancer-related pain: (1) Neuro-immune cross-talk, depicting the complex interactions between tumor cells, immune mediators, sensory neurons, and central sensitization pathways that drive pain pathogenesis; (2) Pharmacological and interventional pain management, encompassing non-opioid and opioid analgesics, adjuvant medications, nerve blocks, intrathecal delivery systems, and neuromodulation techniques; (3) Analgesic radiotherapy, showing targeted radiation delivery to painful bone metastases; and (4) Digital health and AI tools, representing emerging technologies including telemedicine platforms, wearable sensors, mobile applications, and artificial intelligence-enabled predictive models for continuous pain assessment and personalized treatment optimization. This integrated approach reflects the transition from empirical symptom management toward mechanism-based precision medicine in cancer pain care.

4. Discussion

The examined recent evidence further strengthens reconceptualization of cancer-related pain as a multifactorial, dynamically modulated syndrome, rather than a simple byproduct of tissue damage or nerve compression. An updated 2025 review proposes a multidimensional framework for cancer pain, integrating biological, pharmacologic, psychological, sociocultural, and functional domains, thereby reinforcing the need for personalized and mechanism-based treatment strategies [

35].

Within this paradigm, advanced neurostimulation and neuromodulation techniques have gained traction. A recent scoping review focusing exclusively on cancer-induced pain reported that interventions such as SCS, DRGS and PNS can substantially reduce pain: average reductions in NRS pain scores described from 8.0 to 2.2 over follow-up, along with opioid-sparing effects in many cases [

45]. Such data underscore the potential paradigm shift from opioids-centric analgesia to device-based, physiology-targeting pain control in oncology. Importantly though, the authors emphasize the low level of evidence (observational, retrospective), the heterogeneity of cases, and the lack of RCTs, highlighting the urgent need for prospective, controlled studies.

On the radiotherapy front, developments in precision techniques further refine the analgesic arsenal. In 2024, a series on stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for spinal metastases documented significant pain relief: more than half of patients achieved clinically meaningful pain reduction within 3 months post-treatment [

70]. In separate work, robotic-guided spine SBRT was shown to be feasible, well tolerated, and associated with statistically significant improvements in pain and quality of life (p < 0.01) [

71]. These findings suggest that SBRT, beyond its oncologic role, may serve as a durable and well-tolerated analgesic modality, especially in patients with oligometastatic or spinal bone disease.

Concurrently, the field of digital health and AI-enabled pain management in oncology is gaining momentum. A 2024 systematic review compiled 44 studies (2006–2023) investigating machine learning (ML) and AI applications for cancer-related pain: models showed promising performance in classifying pain after cancer therapy or during active disease (median AUC 0.80–0.86), and some attempted to support pain management decisions [

59]. Additional work combined radiomics and NLP to successfully identify pain signatures on radiotherapy simulation CT scans, suggesting that unsupervised and multimodal AI pipelines may soon enable scalable, imaging-based pain assessment [

72]. Yet, despite these advances, critical challenges remain. For neuromodulation, the lack of randomized trials, small sample sizes, and patient heterogeneity limit generalizability. For SBRT, optimal fractionation schemes, re-irradiation criteria, and integration with systemic therapy still lack robust evidence. And for AI-based tools, key obstacles include external validation, data privacy/interoperability, and digital-health literacy, which may limit equity in access. Indeed, the most recent comprehensive evaluation of AI/ML in cancer pain, while optimistic, notes that only 14% of models had external validation, and only 23% had direct clinical application [

59]. Overall, the evidence from 2022-2025 confirms that cancer pain management is progressively evolving toward a multi-specialty precision-medicine model, integrating biological insight, advanced interventional/radiotherapy techniques, and digital technologies [

73]. However, to translate this potential into routine oncology and palliative care, prospective controlled trials, standardization of interventions, and rigorous external validation of AI tools will be essential.

Limitations: this scoping review has several limitations. First, no formal risk-of-bias assessment was undertaken, limiting conclusions regarding the quality or comparative strength of evidence; but this was consistent with scoping-review guidance. Second, the broad scope spanning five domains introduces substantial heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and outcomes, precluding quantitative synthesis. Third, although four major databases were searched, relevant studies published in other repositories or non-English languages may have been missed. Fourth, the inclusion of diverse evidence types, including observational and technological studies, increases variability in reporting standards. Finally, the rapidly evolving fields of neuromodulation and AI may lead to evidence quickly becoming outdated.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review shows that cancer pain management is shifting from empirical symptom control toward mechanism-based, precision-oriented care. Contemporary evidence highlights cancer pain as a multifactorial syndrome driven by tumor–neuron–immune interactions and modulated by individual genetic and epigenetic susceptibility. Therapeutic strategies now encompass advanced neuromodulation, precision radiotherapy, interventional procedures, and digital health–enabled monitoring alongside foundational analgesics. Persistent gaps include limited high-quality trials, insufficient validation of AI-based tools, and inequitable access to novel therapies. Advancing the field requires rigorous prospective studies, methodological standardization, and implementation science to ensure that precision cancer pain management is accessible and clinically effective for all patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V. and A.P.; methodology, G.F., M.L.G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.V.P., Y.V.T., P.V.P., A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.P., M.M., J.V.P, P.V.P., A.D.K., F.B., C.G., M.L.G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Paolo Procacci Foundation for its support in the editing process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ASCO |

American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| ASIC |

Acid-Sensing Ion Channel |

| BDNF |

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| cEBRT |

Conventional External Beam Radiotherapy |

| CGRP |

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide |

| COMT |

Catechol-O-Methyltransferase |

| COX |

Cyclooxygenase |

| DREZ |

Dorsal Root Entry Zone |

| DRGS |

Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation |

| IDDS |

Intrathecal Drug Delivery Systems |

| JBI |

Joanna Briggs Institute |

| MeSH |

Medical Subject Headings |

| mHealth |

Mobile Health |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NGF |

Nerve Growth Factor |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| NRS |

Numeric Rating Scale |

| NSAID |

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug |

| PCC |

Population–Concept–Context |

| PNS |

Peripheral Nerve Stimulation |

| PRISMA-ScR |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| RANKL |

Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand |

| RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RUA |

Rational Use of Analgesics |

| SBRT |

Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy |

| SCS |

Spinal Cord Stimulation |

| SNP |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| TAM |

Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| TME |

Tumor Microenvironment |

| TrkA |

Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase A |

| TRP |

Transient Receptor Potential |

| TRPV1 |

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Getie A, Ayalneh M, Bimerew M. Global prevalence and determinant factors of pain, depression, and anxiety among cancer patients: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25:156. [CrossRef]

- Copenhaver DJ, Huang M, Singh J, Fishman SM. History and Epidemiology of Cancer Pain. Cancer Treat Res. 2021;182:3–15. [CrossRef]

- Snijders RAH, Brom L, Theunissen M, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2023;15:591. [CrossRef]

- Haier J, Schaefers J. Economic Perspective of Cancer Care and Its Consequences for Vulnerable Groups. Cancers. 2022;14:3158. [CrossRef]

- Varrassi G, Farì G, Narvaez Tamayo MA, Gomez MP, Guerrero Liñeiro AM, Pereira CL, et al. Mixed pain: clinical practice recommendations. Front Med [Internet]. Frontiers; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 16];12. [CrossRef]

- Huang Q, Hu B, Zhang P, Yuan Y, Yue S, Chen X, et al. Neuroscience of cancer: unraveling the complex interplay between the nervous system, the tumor and the tumor immune microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 2025;24:24. [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Pan Z, Lai B, Li M, Wang J. Contribution of immune cells to cancer-related neuropathic pain: An updated review. Mol Pain. 2023;19:17448069231182235. [CrossRef]

- Mardelle U, Bretaud N, Daher C, Feuillet V. From pain to tumor immunity: influence of peripheral sensory neurons in cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1335387. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Zhu J, Yu L, Huang Y, Hu Y. Cancer-nervous system crosstalk: from biological mechanism to therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer. 2025;24:133. [CrossRef]

- Yang J-X, Wang H-F, Chen J-Z, Li H-Y, Hu J-C, Yu A-A, et al. Potential Neuroimmune Interaction in Chronic Pain: A Review on Immune Cells in Peripheral and Central Sensitization. Front Pain Res Lausanne Switz. 2022;3:946846. [CrossRef]

- Xiong H-Y, Hendrix J, Schabrun S, Wyns A, Campenhout JV, Nijs J, et al. The Role of the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Chronic Pain: Links to Central Sensitization and Neuroinflammation. Biomolecules. 2024;14:71. [CrossRef]

- WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2025 Nov 29]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537492/. Accessed 29 Nov 2025.

- Daud ML, Simone GGD. Management of pain in cancer patients - an update. Ecancermedicalscience. 2024;18:1821. [CrossRef]

- Paice JA, Bohlke K, Barton D, Craig DS, El-Jawahri A, Hershman DL, et al. Use of Opioids for Adults With Pain From Cancer or Cancer Treatment: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2023;41:914–30. [CrossRef]

- Knegtmans MF, Wauben LSGL, Wagemans MFM, Oldenmenger WH. Home Telemonitoring Improved Pain Registration in Patients With Cancer. Pain Pract Off J World Inst Pain. 2020;20:122–8. [CrossRef]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci IS. 2010;5:69. [CrossRef]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. [CrossRef]

- Fan H-Y, Liang X-H, Tang Y-L. Neuroscience in peripheral cancers: tumors hijacking nerves and neuroimmune crosstalk. MedComm. 2024;5:e784. [CrossRef]

- Yoneda T, Hiasa M, Okui T, Hata K. Cancer-nerve interplay in cancer progression and cancer-induced bone pain. J Bone Miner Metab. 2023;41:415–27. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh M, Shirodkar S, Doshi G. Unraveling the role of perineural invasion in cancer progression across multiple tumor types. Med Oncol Northwood Lond Engl. 2025;42:283. [CrossRef]

- Santoni A, Santoni M, Arcuri E. Chronic Cancer Pain: Opioids within Tumor Microenvironment Affect Neuroinflammation, Tumor and Pain Evolution. Cancers. 2022;14:2253. [CrossRef]

- Martel Matos AA, Scheff NN. Sensory neurotransmission and pain in solid tumor progression. Trends Cancer. 2025;11:309–20. [CrossRef]

- Haroun R, Wood JN, Sikandar S. Mechanisms of cancer pain. Front Pain Res. 2022;3:1030899. [CrossRef]

- Varrassi G, Leoni MLG, Farì G, Al-Alwany AA, Al-Sharie S, Fornasari D. Neuromodulatory Signaling in Chronic Pain Patients: A Narrative Review. Cells. 2025;14:1320. [CrossRef]

- Bugada D, Lorini LF, Fumagalli R, Allegri M. Genetics and Opioids: Towards More Appropriate Prescription in Cancer Pain. Cancers. 2020;12:1951. [CrossRef]

- Ho KWD, Wallace MR, Staud R, Fillingim RB. OPRM1, OPRK1 and COMT Genetic Polymorphisms Associated with Opioid Effects on Experimental Pain: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Pharmacogenomics J. 2020;20:471–81. [CrossRef]

- Rembiałkowska N, Rekiel K, Urbanowicz P, Mamala M, Marczuk K, Wojtaszek M, et al. Epigenetic Dysregulation in Cancer: Implications for Gene Expression and DNA Repair-Associated Pathways. Int J Mol Sci. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2025;26:6531. [CrossRef]

- Cao B, Xu Q, Shi Y, Zhao R, Li H, Zheng J, et al. Pathology of pain and its implications for therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. Nature Publishing Group; 2024;9:155. [CrossRef]

- Pu T, Sun J, Ren G, Li H. Neuro-immune crosstalk in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. Nature Publishing Group; 2025;10:176. [CrossRef]

- Worsley CM, Veale RB, Mayne ES. The acidic tumour microenvironment: Manipulating the immune response to elicit escape. Hum Immunol. 2022;83:399–408. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Allavena P, Garlanda C, Locati M. Tumor-associated macrophages and the related myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a paradigm of the diversity of macrophage activation. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:325–30. [CrossRef]

- Zhen G, Fu Y, Zhang C, Ford NC, Wu X, Wu Q, et al. Mechanisms of bone pain: Progress in research from bench to bedside. Bone Res. Nature Publishing Group; 2022;10:44. [CrossRef]

- Ferraguti G, Terracina S, Tarani L, Fanfarillo F, Allushi S, Caronti B, et al. Nerve Growth Factor and the Role of Inflammation in Tumor Development. Curr Issues Mol Biol. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2024;46:965–89. [CrossRef]

- Page AJ, Mulvey MR, Bennett MI. Designing a clinical trial of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for cancer pain: a survey of UK palliative care physicians. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023;13:e55–8. [CrossRef]

- Shapoo N, Rehman A, Izaguirre-Rojas C, Gotlieb V, Boma N. Cancer Pain Is Not One-Size-Fits-All: Evolving from Tradition to Precision. Clin Pract. 2025;15:173. [CrossRef]

- Senthilnathan V., Priyadharshini V., Selin Asha J. From Pain Relief to Cancer Defense: The Promise of NSAIDs. J Adv Med Pharm Sci. 2023;25:59–67. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Shaheed C, Hayes C, Maher CG, Ballantyne JC, Underwood M, McLachlan AJ, et al. Opioid analgesics for nociceptive cancer pain: A comprehensive review. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:286–313. [CrossRef]

- Flausino LE, Ferreira IN, Tuan W-J, Estevez-Diz MDP, Chammas R. Association of COX-inhibitors with cancer patients’ survival under chemotherapy and radiotherapy regimens: a real-world data retrospective cohort analysis. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1433497. [CrossRef]

- Nwosu ADG, Chukwu LC, Onwuasoigwe O, Nweze SO, Nwadike K. Redefining the Role of Analgesic Adjuvants in Pain Management: A Narrative Review. Indian J Pain. 2023;37:65. [CrossRef]

- Wong AK, Hawke J, Eastman P, Buizen L, Le B. Does cancer type and adjuvant analgesic prescribing influence opioid dose?-a retrospective cross-sectional study. Ann Palliat Med. 2023;12:783–90. [CrossRef]

- Habib MH, Schlögl M, Raza S, Chwistek M, Gulati A. Interventional pain management in cancer patients-a scoping review. Ann Palliat Med. 2023;12:1198–214. [CrossRef]

- Deo SVS, Kumar N, Rajendra VKJ, Kumar S, Bhoriwal SK, Ray M, et al. Palliative Surgery for Advanced Cancer: Clinical Profile, Spectrum of Surgery and Outcomes from a Tertiary Care Cancer Centre in Low-Middle-Income Country. Indian J Palliat Care. 2021;27:281–5. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah N, Sindt JE, Whittle J, Anderson JS, Odell DW, Mahan M, et al. Impact of neuromodulation on opioid use, adjunct medication use, and pain control in cancer-related pain: a retrospective case series. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2023;24:903–6. [CrossRef]

- Grenouillet S, Balayssac D, Moisset X, Peyron R, Fauchon C. Analgesic efficacy of non-invasive neuromodulation techniques in chronic cancer pain: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2025;33:346. [CrossRef]

- Vu PD, Mach S, Javed S. Neurostimulation for the Treatment of Cancer-Induced Pain: A Scoping Review. Neuromodulation J Int Neuromodulation Soc. 2025;28:191–203. [CrossRef]

- Adams JL, Goble G, Johnson A. Multidisciplinary Approaches: Cingulotomy in an Adult With Refractory Neuropathic Cancer-Related Pain. J Palliat Med. 2023;26:1297–301. [CrossRef]

- Altamirano JM, Khalid SI, Slavin KV. Neurosurgical Techniques for Chronic Pain in Adult Cancer Survivors. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2025;1–10. [CrossRef]

- Cilla S, Rossi R, Donati CM, Habberstad R, Klepstad P, Dall’Agata M, et al. Pain Management Adequacy in Patients With Bone Metastases: A Secondary Analysis From the Palliative Radiotherapy and Inflammation Study Trial. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2025;19:11795549241297054. [CrossRef]

- Murakami S, Kitani A, Kubota T, Uezono Y. Increased pain after palliative radiotherapy: not only due to cancer progression. Ann Palliat Med. 2024;13:18–21. [CrossRef]

- Grosinger AJ, Alcorn SR. An Update on the Management of Bone Metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2024;26:400–8. [CrossRef]

- Bindels BJJ, Mercier C, Gal R, Verlaan J-J, Verhoeff JJC, Dirix P, et al. Stereotactic Body and Conventional Radiotherapy for Painful Bone Metastases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2355409. [CrossRef]

- Rossi R, Medici F, Habberstad R, Klepstad P, Cilla S, Dall’Agata M, et al. Development of a predictive model for patients with bone metastases referred to palliative radiotherapy: Secondary analysis of a multicenter study (the PRAIS trial). Cancer Med. 2024;13:e70050. [CrossRef]

- Donati CM, Galietta E, Cellini F, Di Rito A, Portaluri M, De Tommaso C, et al. Further Clarification of Pain Management Complexity in Radiotherapy: Insights from Modern Statistical Approaches. Cancers. 2024;16:1407. [CrossRef]

- Konopka-Filippow M, Politynska B, Wojtukiewicz AM, Wojtukiewicz MZ. Cancer Pain: Radiotherapy as a Double-Edged Sword. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:5223. [CrossRef]

- Hamdoune M, Jounaidi K, Ammari N, Gantare A. Digital health for cancer symptom management in palliative medicine: systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024;14:392–402. [CrossRef]

- Paterson C, Bacon R, Dwyer R, Morrison KS, Toohey K, O’Dea A, et al. The Role of Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic Across the Interdisciplinary Cancer Team: Implications for Practice. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2020;36:151090. [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco G, Papa A, Schatman ME, Tinnirello A, Terranova G, Leoni MLG, et al. Practical Advices for Treating Chronic Pain in the Time of COVID-19: A Narrative Review Focusing on Interventional Techniques. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2303. [CrossRef]

- El-Tallawy SN, Pergolizzi JV, Vasiliu-Feltes I, Ahmed RS, LeQuang JK, Alzahrani T, et al. Innovative Applications of Telemedicine and Other Digital Health Solutions in Pain Management: A Literature Review. Pain Ther. 2024;13:791–812. [CrossRef]

- Salama V, Godinich B, Geng Y, Humbert-Vidan L, Maule L, Wahid KA, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Cancer Pain: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;68:e462–90. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz BL, Gupta V, Kumar R, Jalin A, Cao X, Ziegenbein C, et al. Data Preprocessing Techniques for AI and Machine Learning Readiness: Scoping Review of Wearable Sensor Data in Cancer Care. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2024;12:e59587. [CrossRef]

- Innominato PF, Macdonald JH, Saxton W, Longshaw L, Granger R, Naja I, et al. Digital Remote Monitoring Using an mHealth Solution for Survivors of Cancer: Protocol for a Pilot Observational Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13:e52957. [CrossRef]

- Cloß K, Verket M, Müller-Wieland D, Marx N, Schuett K, Jost E, et al. Application of wearables for remote monitoring of oncology patients: A scoping review. Digit Health. 2024;10:20552076241233998. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Leoni MLG, Shariff MN, Varrassi G. Towards artificial intelligence application in pain medicine. Recenti Prog Med. 2025;116:156–61. [CrossRef]

- Soltani M, Farahmand M, Pourghaderi AR. Machine learning-based demand forecasting in cancer palliative care home hospitalization. J Biomed Inform. 2022;130:104075. [CrossRef]

- Bang YH, Choi YH, Park M, Shin S-Y, Kim SJ. Clinical relevance of deep learning models in predicting the onset timing of cancer pain exacerbation. Sci Rep. 2023;13:11501. [CrossRef]

- Noe-Steinmüller N, Scherbakov D, Zhuravlyova A, Wager TD, Goldstein P, Tesarz J. Defining suffering in pain: a systematic review on pain-related suffering using natural language processing. Pain. 2024;165:1434–49. [CrossRef]

- DiMartino L, Miano T, Wessell K, Bohac B, Hanson LC. Identification of Uncontrolled Symptoms in Cancer Patients Using Natural Language Processing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63:610–7. [CrossRef]

- None N. Towards an AI-Empowered Multimodal Pain Assessment Tool for Cancer-Related Pain. 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 30]; https://repository.tudelft.nl/record/uuid:efaadcb3-03fa-4f8e-ac87-33f5098f06af. Accessed 30 Nov 2025.

- Cascella M, Shariff MN, Viswanath O, Leoni MLG, Varrassi G. Ethical Considerations in the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Pain Medicine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025;29:10. [CrossRef]

- Chou K-N, Park DJ, Hori YS, Persad AR, Chuang CF, Emrich SC, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for painful spinal metastases: a decade of experience at a single institution. J Neurosurg Spine. 2024;41:532–40. [CrossRef]

- Rivas D, de la Torre-Luque A, Suárez V, García R, Fernández C, Gonsalves D, et al. Robotic Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Spine Metastasis Pain Relief. Appl Sci. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2024;14:1775. [CrossRef]

- Naseri H, Skamene S, Tolba M, Faye MD, Ramia P, Khriguian J, et al. A Scalable Radiomics- and Natural Language Processing-Based Machine Learning Pipeline to Distinguish Between Painful and Painless Thoracic Spinal Bone Metastases: Retrospective Algorithm Development and Validation Study. Jmir Ai. 2023;2:e44779. [CrossRef]

- Corriero A, Giglio M, Soloperto R, Preziosa A, Stefanelli C, Castaldo M, Gloria F, Paladini A, et al. The Missing Link: Integrating Interventional Pain Management in the Era of Multimodal Oncology. Pain Ther. 2025 Aug;14(4):1223-1246. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).