Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PECO Components and Criteria

2.2 Literature Search, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

2.3. Effect Size and Variance Calculations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

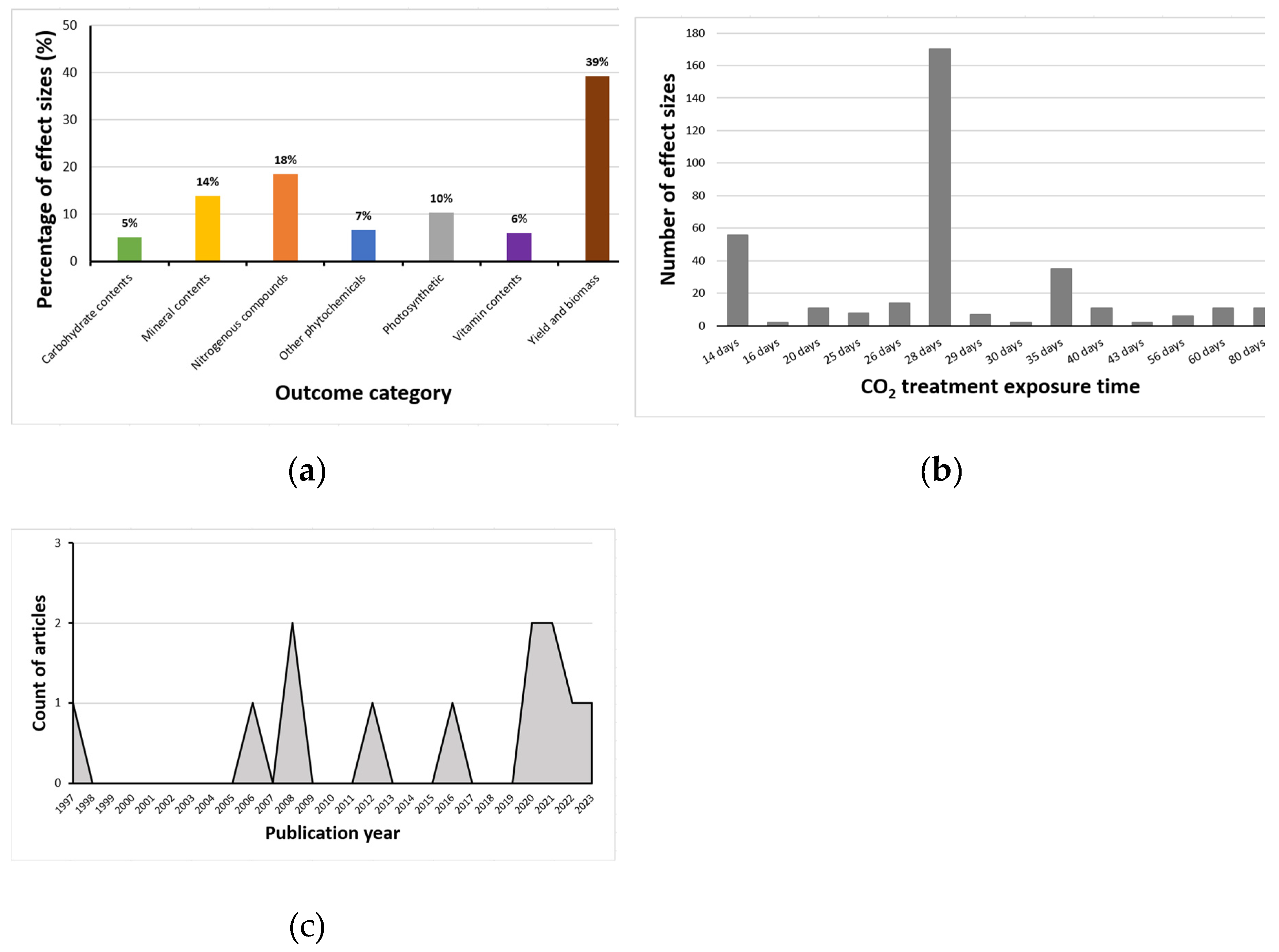

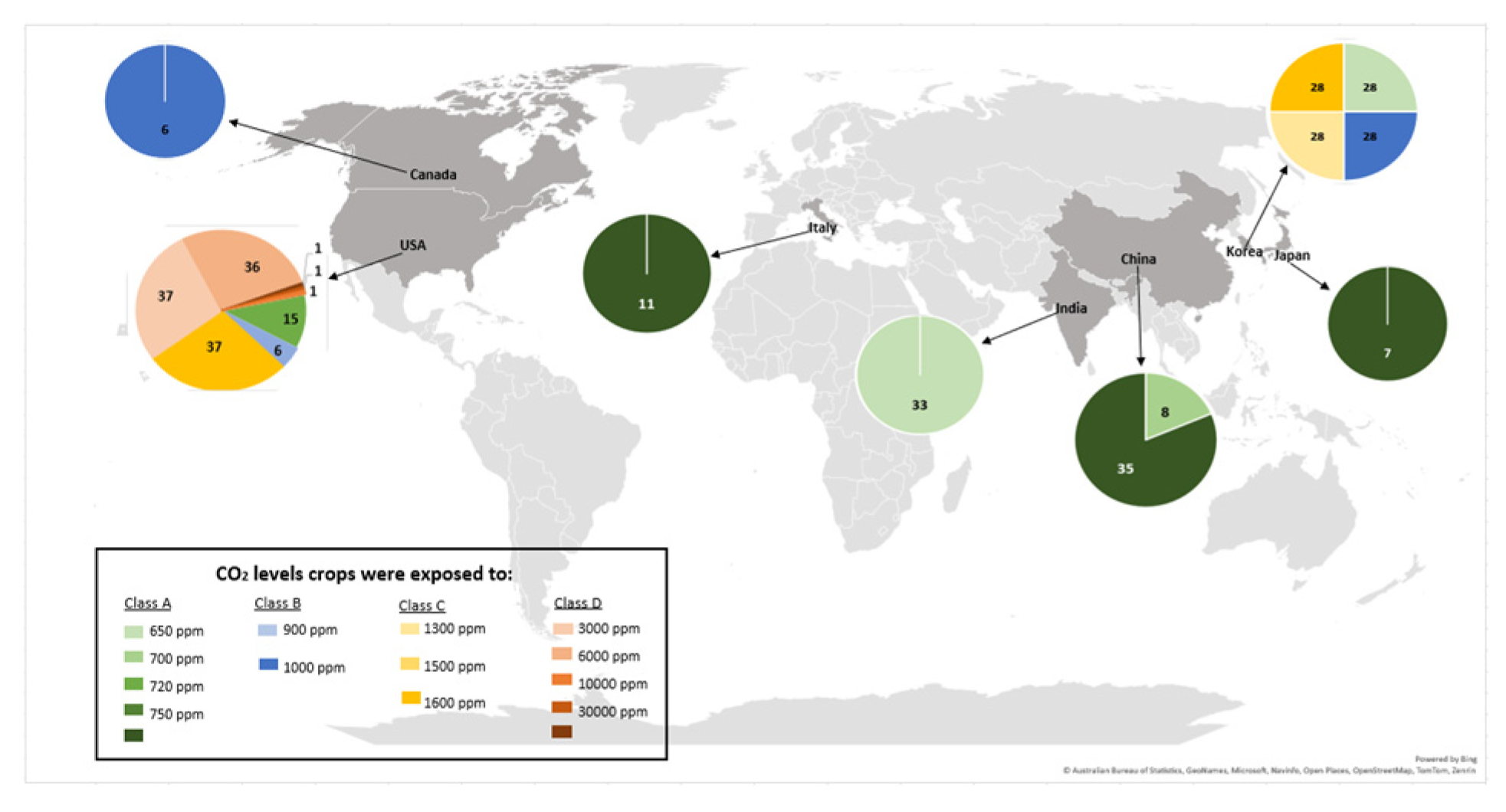

3.1. Bibliography summary

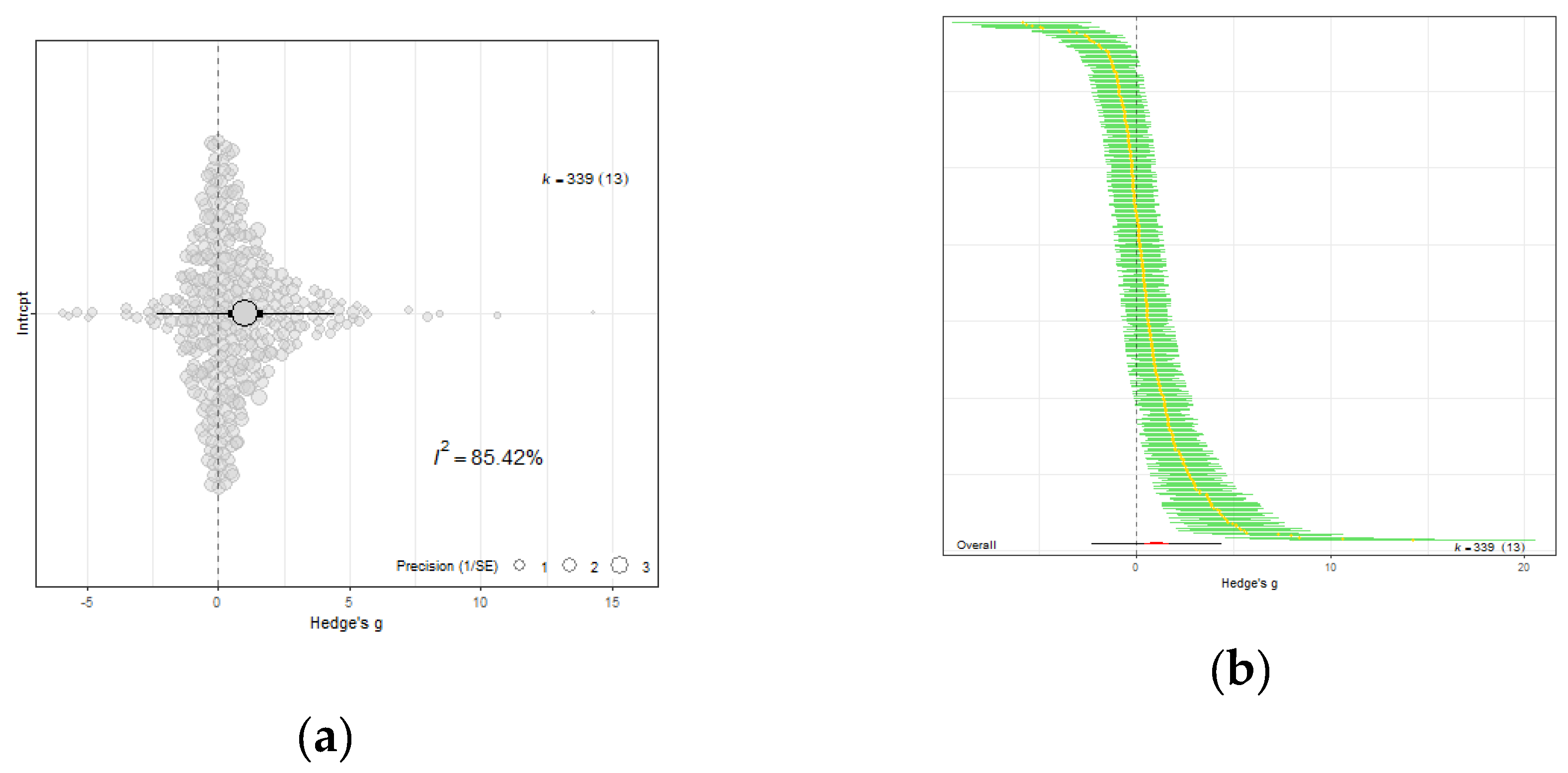

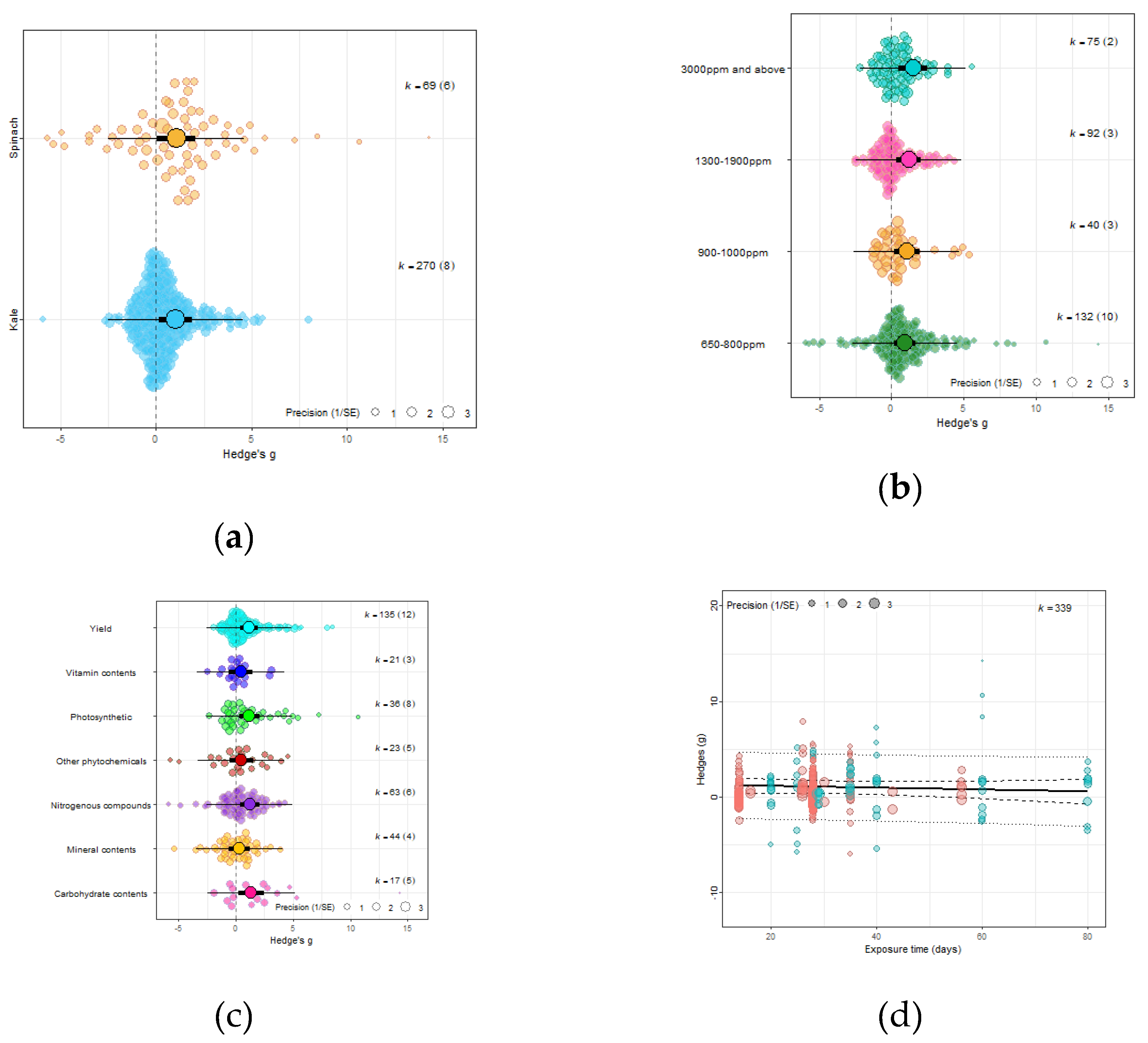

3.2. Overall and combined effect

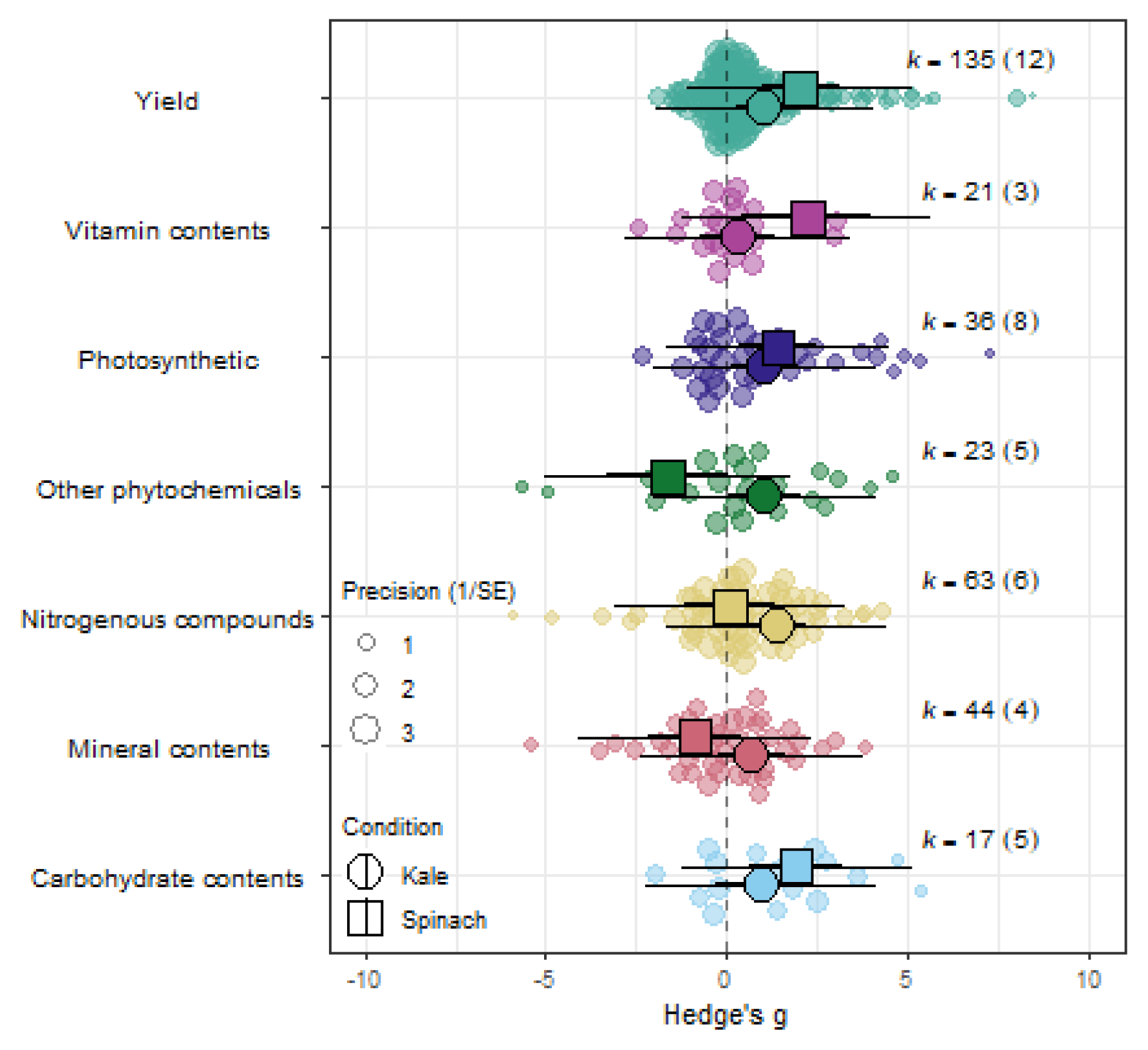

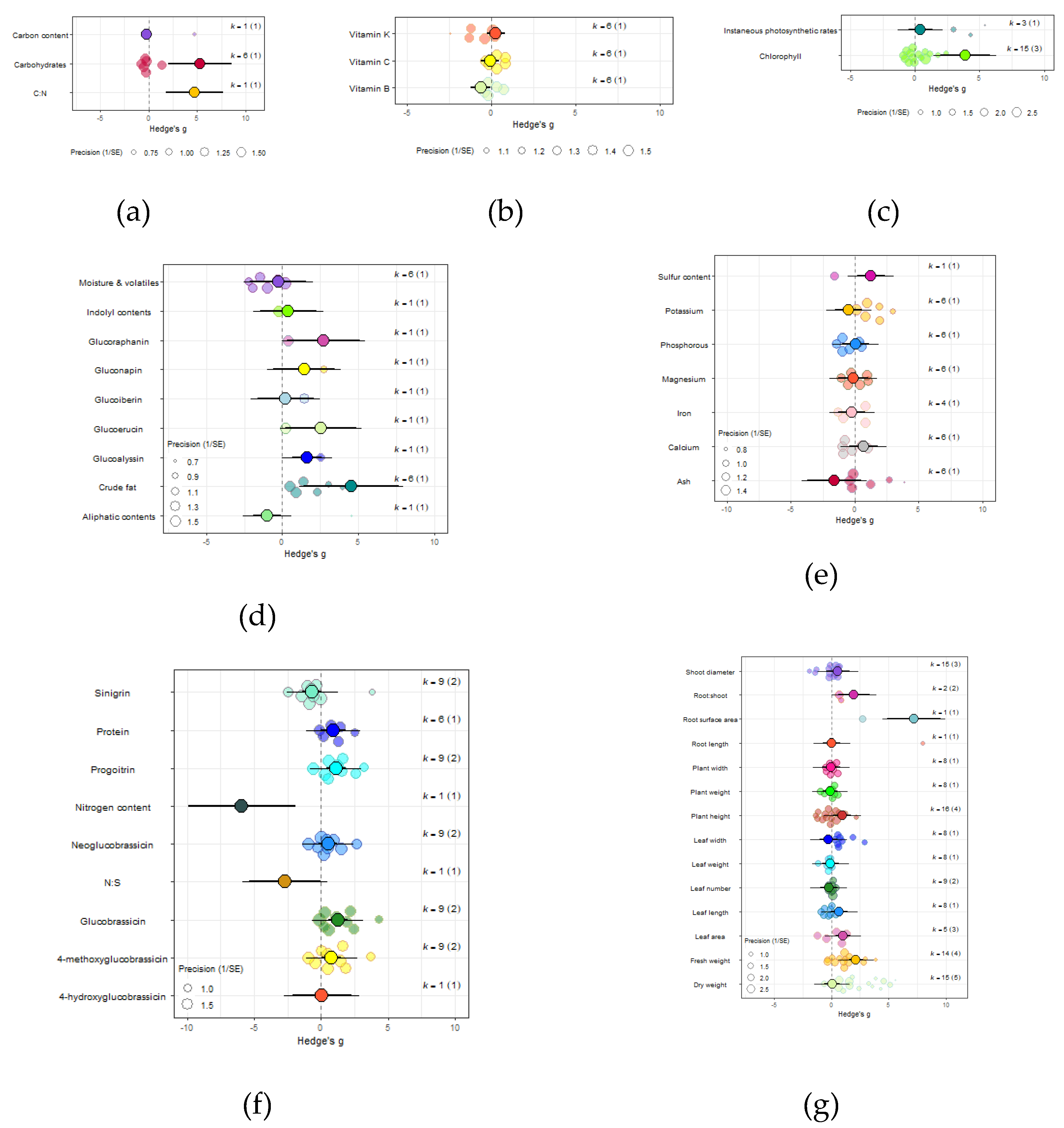

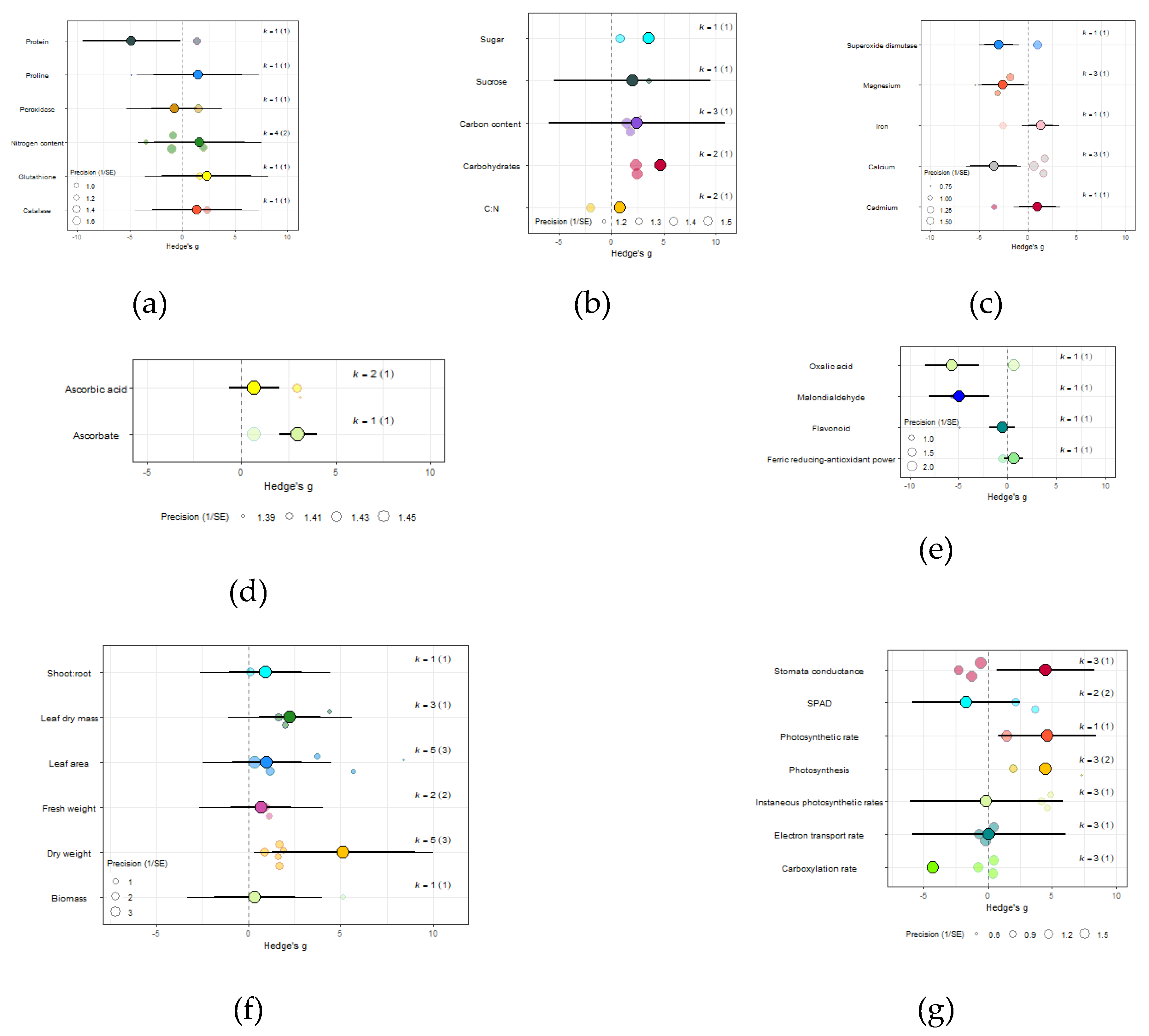

3.3. Effect on individual constituents

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Combined Effect of Elevated CO2 on Spinach and Kale

4.2. Effect on Nutritional Components and Implications for Global Health

(i) Yields and Biomass

(ii) Carbohydrate/carbon contents

(iii) Proteins and Nitrogenous Compounds

(iv) Minerals

(v) Vitamins

(vi) Other Phytochemicals

(vii) Photosynthetic Parameters

4.3. Implications for Future Sustainability and Agriculture

4.4. Limitations, Research Gaps, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO2 | Atmospheric carbon dioxide |

| eCO2 | Elevated carbon dioxide |

| RuBisCO | The enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase |

| FACE | Free-air CO2 enrichment |

| ppm | Parts per million |

| CEE | Collaboration for Environmental Evidence guidelines |

| PECO | Population, Exposure, Comparator and Outcome eligibility criteria |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (assessed on 16th March 2025).

- Wheeler, R.M.; Spencer, L.E.; Bhuiyan, R.H.; Mickens, M.A.; Bunchek, J.M.; van Santen, E.; Massa, G.D.; Romeyn, M.W. Effects of elevated and super-elevated carbon dioxide on salad crops for space. Journal of Plant Interactions 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, J.A. Responses of soybeans and wheat to elevated CO2 in free-air and open top chamber systems. Field Crops Research 2016, 186, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.S. Nutritional quality and health benefits of vegetables: A review. Food and Nutrition Sciences 2012, 3, 1354–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; Zanobetti, A.; Kloog, I. , Huybers, P.; Leakey, A.D.B.; Bloom, A.J.; Carlisle, E.; Dietterich, L.H.; Fitzgerald, G.; Hasegawa, T.; Holbrook, N.M.; Nelson, R.L.; Ottman, M.J.; Raboy, V.; Sakai, H.; Sartor, K.A.; Schwartz, J.; Seneweera, S.; Tausz, M.; Usui, Y. Increasing CO2 threatens human nutrition. Nature 2014, 510, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; Uauy, R. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megan, W.; What are the health benefits of kale? Med. News Today 2020. Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/270435.php (assessed on 8th November 2024).

- Wang, X.; Li, D.; Song, X. Elevated CO2 mitigates the effects of cadmium stress on vegetable growth and antioxidant systems. Plant, Soil and Environment 2023, 69, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanifar, H.; Yazdanpanah, N.; Golkar Hamzee Yazd, H.; Tavousi, M.; Mahmoodabadi, M. Spinach growth regulation due to interactive salinity, water, and nitrogen stresses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 1654–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šamec, D.; Urlić, B.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) as a superfood: review of the scientific evidence behind. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 20, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, C.; Pan, S.; Yang, J.; Miao, R.; Ren, W.; Yu, Q.; Fu, B.; Jin, F.-F.; Lu, Y.; Melillo, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Palm, C.; Reilly, J. Optimizing resource use efficiencies in the food–energy–water nexus for sustainable agriculture: from conceptual model to decision support system. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 33, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Statistical Database: Production of Spinach 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on day month year).

- United States Department of Agriculture. FoodData Central: Kale, raw 2020. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov (assessed on 20th September 2024).

- Public Health England. Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset (CoFID). London: Public Health England 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/composition-of-foods-integrated-dataset-cofid (assessed on 20th September 2024).

- Taub, D.R.; Miller, B.; Allen, H. Effects of elevated CO2 on the protein concentration of food crops: A meta-analysis. Global Change Biology 2008, 14, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, A.K.; Gunnapaneni, D.; Bhanu, D.; Vanaja, M.; Lakshmi, N.J.; Yadav, S.K.; Prabhakar, M.; Singh, V.K. Elevated CO2 and Water Stress in Combination in Plants: Brothers in Arms or Partners in Crime? Biology 2022, 11, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leakey, A.D.B.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Rogers, A.; Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. Elevated CO2 effects on plant carbon, nitrogen, and water relations: Six important lessons from FACE. Journal of Experimental Botany 2009, 60, 2859–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, A.; Reddy, K.R.; Walne, C.H.; Barickman, T.C.; Brazel, S.; Chastain, D.; Gao, W. Individual and Interactive Effects of Multiple Abiotic Stress Treatments on Early-Season Growth and Development of Two Brassica Species. Agriculture 2022, 12, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. Guidelines and Standards for Evidence synthesis in Environmental Management 2022. Version 5.1 (Pullin, A.S.; Frampton, G.K.; Livoreil, B.; Petrokofsky, G. Eds). Available online: www.environmentalevidence.org/information-for-authors. (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Newson, R.B.; Formulas for estimating and pooling Hedges’ g parameters in a meta-analysis 2020. Roger Newson Resources, 1-6. Available online: https://www.rogernewsonresources.org.uk/miscdocs/metahedgesg1.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R 2020. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Lagisz, M.; O'Dea, R.E.; Pottier, P.; Rutkowska, J.; Senior, A.M.; Yang, Y.; Noble, D.W.A. orchaRd 2.0: An R package for visualising meta-analyses with orchard plots. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Guo, D.; Gao, X.; Zhao, X. Water Deficit Modulates the CO2 Fertilisation Effect on Plant Gas Exchange and Leaf-Level Water Use Efficiency: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 12, 775477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, S.; Moscatello, S.; Giacomelli, G.A.; Battistelli, A. Influence of the interaction between light intensity and CO2 concentration on productivity and quality of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) grown in fully controlled environment. Advances in Space Research 2013, 52, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Reay, D.; Higgins, P. The impact of global dietary guidelines on climate change. Global Environmental Change 2018, 49, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Leakey, A.D.B. Will elevated carbon dioxide concentration amplify the benefits of nitrogen fixation in legumes? Plant Physiology 2009, 151, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekele, J.U.; Webster, R.; Perez de Heredia, F.; Lane, K.E.; Fadel, A.; Symonds, R.C. Current impacts of elevated CO2 on crop nutritional quality: a review using wheat as a case study. Stress Biol. 2025, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.J.; Tausz, M.; O'Leary, G.; Mollah, M.R.; Tausz-Posch, S.; Seneweera, S.; Norton, R.M.; Fitzgerald, G.J. Elevated atmospheric CO2 can dramatically increase wheat yields in semi-arid environments and buffer against heat waves. Global Change Biology 2016, 22, 2269–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziska, L.H. Rising Carbon Dioxide and Global Nutrition: Evidence and Action Needed. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, K.; Yasutake, D.; Kaneko, T.; Takada, A.; Okayasu, T.; Ozaki, Y.; Mori, M.; Kitano, M. Long-term compound interest effect of CO2 enrichment on the carbon balance and growth of a leafy vegetable canopy. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 283, 110060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Pal, M.; Raj, A.; Khetarpal, S. Photosynthesis and nutrient composition of spinach and fenugreek grown under elevated carbon dioxide concentration. Biol Plant 2007, 51, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.W.; Du, S.T.; Zhang, Y.S.; Tang, C.; Lin, X.Y. Atmospheric nitric oxide stimulates plant growth and improves the quality of spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Annals of Applied Biology 2009, 155, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Hobbie; S. E., Lee, T.; Ellsworth, D.S.; West, J.B.; Tilman, D.; Knops, J.M.; Naeem, S.; Trost, J. Nitrogen limitation constrains sustainability of ecosystem response to CO2. Nature 2006, 440, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loladze, I. Hidden shift of the ionome of plants exposed to elevated CO2 depletes minerals at the base of human nutrition. eLife 2014, 3, e02245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.R.; Myers, S.S. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, G.X.; Fang, P.; Teng, Y.B.; Li, Y.J.; Lin, X.Y. Effect of CO2 enrichment on the glucosinolate contents under different nitrogen levels in bolting stem of Chinese kale (Brassica alboglabra L.). J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2009, 10, 454–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, J.; Gesick, E. Photosynthetic responses of swiss chard, kale, and spinach cultivars to irradiance and carbon dioxide concentration. HortScience 2017, 52, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report 2022. Available online: https:://www.cdc.gov/. (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Hruby, A.; Hu, F.B. The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.D.; Lin, J.; Mahoney, T.; Ume, N.; Yang, G.; Gabbay, R.A.; ElSayed, N.A.; Bannuru, R.R. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2022. Diabetes care 2024, 47, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.J.; Burger, M.; Asensio, J.S.R.; Cousins, A.B. Carbon dioxide enrichment inhibits nitrate assimilation in wheat and Arabidopsis. Science 2010, 328, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Reddy, K.R.; Walne, C.H.; Barickman, T.C.; Brazel, S.; Chastain, D.; Gao, W. Climate Stressors on Growth, Yield, and Functional Biochemistry of two Brassica Species, Kale and Mustard. Life 12, 1546. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Healthy diets. (WHO fact sheet series 2020). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Chowdhury, M.; Kiraga, S.; Islam, M.N.; Ali, M.; Reza, M.N.; Lee, W.H.; Chung, S.O. Effects of Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Carbon Dioxide Concentration on Growth and Glucosinolate Content of Kale Grown in a Plant Factory. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Naqvi, S.; Gomez-Galera, S.; Pelacho, A.M.; Capell, T.; Christou, P. Transgenic strategies for the nutritional enhancement of plants. Trends in Plant Science 2018, 12, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Micronutrient deficiencies – malnutrition 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Tisserat, B.; Herman, C.; Silman, R.; Bothast, R.J. Using Ultra-high Carbon Dioxide Levels Enhances Plantlet Growth In Vitro. HortTechnology 1997, 7, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Rogers, A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: Mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant, Cell & Environment 2007, 30, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, M.; Hoshika, Y.; Killi, D. Has the Impact of Rising CO2 on Plants been Exaggerated by Meta-Analysis of Free Air CO2 Enrichment Studies? Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (21 November 2011) 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reekie, G.E. , MacDougall, G., Wong, I. & Hicklenton, P.R. Effect of sink size on growth response to elevated atmospheric CO2 within the genus Brassica. Canadian Journal of Botany 1998, 76, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).