Introduction:

‘Pranic’ energy or Qi (or Chi) is a foundational concept in traditional Chinese philosophy and medicine, referring to the universal life force or vital energy that flows through all living beings and the natural world and is essential for physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. It is considered the animating force responsible for health, vitality, and balance. This ‘Pranic’ or Qi is conceptually similar to other life force energies recognized in different cultures, such as ‘Prana’ in Sanskrit, ‘Ki’ in Japanese, and ‘Ruah’ in Hebrew traditions.

This universal life force energy is also known as Qi or ‘Pranic’ energy’ that aligns closely with the idea of a subtle energy that can be harnessed and directed to support health and healing in both humans and plants. The concept of ‘Pranic’ energy is rooted in the understanding that the physical body has a corresponding energetic blueprint that is essential for health and wellness. ‘Pranic’ energy treatment utilizes projecting the life forces from the hands to specific parts or organs without physically touching, to promote and restore health. In this context, the application of ‘Pranic’ energy techniques to plants can initiate a biological alteration within plant system.

According to Master Choa Kok Sui, plants also take in prana from the surrounding air, water, soil, and sunlight [

1]. Several studies have been reported that the application of ‘Pranic’ energy in various crop plants has increased their economic traits like increased growth and germination indices in papaya seeds [

2]; enhanced storage longevity of brinjal; improved germination rates, seedling vigor, root and shoot length of drumstick and improvement of physico-chemical traits in tomatoes [

3,

4,

5,

6]. These reports suggested the ‘Pranic’ energy mediated an alternative signaling process that lead to those altered phenotypic traits in a plant system. However, there is knowledge gap regarding physiological, metabolic, and molecular bases of the plant responses to the ‘Pranic’ energy treatment, leading to these phenotypic alterations.

In this study, we aim to investigate the effects of ‘Pranic’ energy treatment on plant growth, metabolism with their nutraceutical properties in control indoor farming environment. We have evaluated the impacts of ‘Pranic’ energy treatments on a leafy vegetable, including non-invasive deep phenotyping, time lapse measurements of growth rates, plant architecture of both below and above ground parts of the plants. Moreover, we also studied the metabolic and nutraceutical quality traits of the leaf that supports crop improvements. Through this research, we hope to contribute to the knowledge and understanding of the mechanisms of plant responses to ‘Pranic’ treatment, further exploring its potential an innovative and environmentally friendly sustainable alternative to conventional agricultural practices.

Materials and Methods:

Application of ‘Pranic’ Energy Treatments to the Plant System

‘Pranic’ energy treatment was applied on the inputs, including seeds, water and soil. As the plants grew, the treatment was applied at regular intervals of 3-5 days. The treatment involves the use of ‘Pranic’ healing principles, specifically cleansing and energizing, as described in the book Advanced Pranic Healing (Sui, 1990). Briefly, ‘Pranic’ energy treatment involved projecting ‘Pranic’ energy to the energetic system of the targets with no physical contact. The practitioners (SS and MG) used their hands to apply ‘Pranic’ energy to loosen, decongest, and remove stagnant and dirty energy. This was followed by energizing the targets with fresh, clean and revitalizing ‘Pranic’ energy. ‘Pranic’ energy treatment was continued for the 30 days of the crop cycle.

Plant Growth Conditions

BVB peat moss soil (Holland) and sand were mixed in a 3:1 ratio as it helps maintain proper aeration in the ground. Around 400g of premixed soil were filled in each pot. The control Choy sum seeds were sowed in the soil on day 0 (one seed per pot). The ‘Pranic’ treated Choy sum seeds, soil and water were underwent for ‘Pranic’ treatment and treated seeds were sowed in the soil on day 0 (one seed per pot). 16 replicates were taken for control and treated. The pots were kept in the growth room fitted with a rack system. The light intensity was 300 µmol/m2s, temp 23˚C, and 75-80% humidity. The pots were watered once in three days (for ‘Pranic’ treated plants, used ‘Pranic’ treated water). ‘Pranic’ treatment was carried out once in three days until day 18.

Measurement of Shoot And Root Biomass

After day 24 the ‘Pranic’ energy treated and untreated plants were gently uprooted, plant shoot biomass and height were measured. Root length and area were scanned and analyzed using WinRhizo™ and biomass determined by weighing. Statistical analyses were carried out in R and a Student’s t-test was used to check the significant differences between the treatment and control.

2.4. Plant Digital Phenotyping and Pigment Contents Using Multispectral Imaging

The automated plant phenotyping system PlantEye™ F500 (Phenospex, Heerlen, The Netherlands) was used to gather multispectral and structural information about plants. The PlantEye is equipped with an active sensor that projects a laser line with a wavelength of 940nm vertically onto the vegetation and records the reflection of the laser and the reflectance in Red, Green, Blue, and Near-Infrared with an integrated tilted camera. Data was collected for day 14, 19 and 24. All 2D height profiles captured by moving the scanner over the plants were then grouped to generate a 3D point cloud. These were processed with the built-in software HortControl (Phenospex, Heerlen, The Netherlands) that provides morphological and physiological parameters.

Leaf Texture Analysis:

The strength of Choy sum leaves was measured using the Film Support Rig. Sample leaf was cut to size of 1.5 x 1.5 cm square and supported between plates which expose a circular section. A spherical probe of diameter 5mm was pushed through to perform extension and elasticity test. The maximum force to rupture the sample, i.e. burst strength was recorded. The distance from probe touching sample until maximum force reached was also recorded.

Analysis of Phenolics from Plant Leaves:

Leaves from both ‘Pranic’ energy treated and untreated plants were collected and subjected to freeze drying. Samples were then ground into a fine powder, from where 50 mg was used for the extraction and analysis of phenolic compounds, following a previously published methodology [

7]. The leaf powder was reconstituted in 1.5 mL of 70% methanol solution containing 50 ng/ml apigenin as an internal standard. The reconstituted extract underwent sonication for 20 min, followed by centrifugation at 20,000g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was collected, and this reconstitution and centrifugation process was repeated two more times to create a pooled supernatant. The pooled supernatant was then filtered using a 0.22 µm PTFE syringe filter and diluted 20 times with 70% methanol containing the internal standard before injection into the liquid chromatography system.

For analysis of the phenolic compounds, a liquid chromatography coupled with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC-QQQ) with a Jet Stream ESI in the negative ionization mode (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA) was utilized. The chromatographic separation was performed using a Zorbax RRHD XDB-C18 column (100 mm X 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm) (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) at a column temperature of 35ºC. Two mobile phases, A and B, were used: water with 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, respectively. The gradient elution was as follows: 2% of B (0-4 min), 2-80% of B (4-25 min), 80-90% of B (25-36 min), 2% of B (36-40 min), with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min and an injection volume of 10 µL. The detection parameters were set according to the previously published literature7. Nitrogen was used as the drying gas at a temperature of 290ºC, with a flow rate of 11 L/min. The nebulizer gas pressure was maintained at 40 psi, the sheath gas temperature at 350ºC with a flow rate of 12 L/min, and the capillary voltage at 3000V. The final identification of the compounds was carried out using commercially available reference standards.

Analysis of Vitamins from Plant Leaves:

Leaves from both '‘Pranic’' treated and untreated plants were collected and subjected to freeze drying. After freeze drying, the leaves were finely ground into a powder, and 100 mg of the powder was used for the extraction and analysis of phenolic compounds. The leaf powder was reconstituted in 1 mL of ethanol containing 1 mg/mL butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and 2.5 µg/mL of internal standards (8'-apo-trans-β-carotenal, α-tocopherol acetate, and menaquinone). The reconstituted extract was then sonicated for 15 min and centrifuged at 20,000g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was collected, and this reconstitution and centrifugation process was repeated two more times to obtain a pooled supernatant. The pooled supernatant was subsequently filtered using a 0.22 µm syringe filter and diluted 50 times with methanol containing 1 mg/mL BHT before injection into the liquid chromatography system.

For the analysis of phenolic compounds, a liquid chromatography coupled with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC-QQQ) with an Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) source in positive ionization mode (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA) was employed. The chromatographic separation was performed using a YMC Carotenoid-C30 column (150 mm X 2.1 mm, 3 µm) (YMC Co., Ltd; Kyoto, Japan) at a column temperature of 35ºC. Two mobile phases, A and B, were used: methanol/water (90/10, v/v) and isopropanol/methanol (70/30, v/v). The gradient elution protocol was as follows: 15-30% of B (0-5 min), 30-45% of B (5-15 min), 45-95% of B (15-17 min), 95% of B (17-30 min), with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min and an injection volume of 10 µL. The detection parameters were set according to the previously published literature (Lee et al., 2022). The APCI source parameters included a nebulizing gas flow rate of 2.5 L/min, interface temperature of 350ºC, heat block temperature of 200ºC, drying gas flow rate of 3 L/min, corona current of 5 µA, and capillary voltage of 4500V. The final identification of the compounds was performed using commercially available reference standards.

Analysis of Sugars from Plant Leaves:

Leaves from both '‘Pranic’' treated and untreated plants were collected and subjected to freeze drying. Once freeze dried, the leaves were finely ground into a powder, and 10 mg of the powder was used for the extraction and analysis of phenolic compounds based on a previously published methodology [

8]. The powdered samples were reconstituted in 1 mL of methanol containing 1 mg/mL of butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) as an internal standard. The reconstituted extract was then vortexed for 30 s followed by a 15 min incubation at 70ºC. After the incubation, the sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes, and the resulting supernatant was collected and dried under vacuum. The dried samples were subsequently dissolved in 20 µL of methoxyamine hydrochloride and incubated for 120 min at 37ºC. Immediately after the completion of the incubation, 40 µL of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) was added as the final derivatizing agent and incubated for 45 min at 70ºC. Once completed, the samples were injected into the gas chromatography system.

For sugar analysis, a gas chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (GC-QTOF) (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA) was utilized. A 1 µL sample injection was performed in split mode with a split ratio of 10:1, and compound separation was achieved using a DB-5MS column (30 m × 0.32 45 mm id, film thickness 0.25 µm) (Agilent Technologies Inc., USA). The inlet temperature was maintained at 280ºC, and helium was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The oven temperature ramp was set as follows: initially at 70ºC, held for 4 minutes, then ramped to 300ºC at a rate of 5ºC/min, and finally held for 10 minutes. The MS transfer line temperature and ion source temperature were set at 300ºC and 230ºC, respectively; and the ionization voltage was set to 70eV. Data acquisition was performed in full scan monitoring mode with a mass scanning range of 40-600 amu.

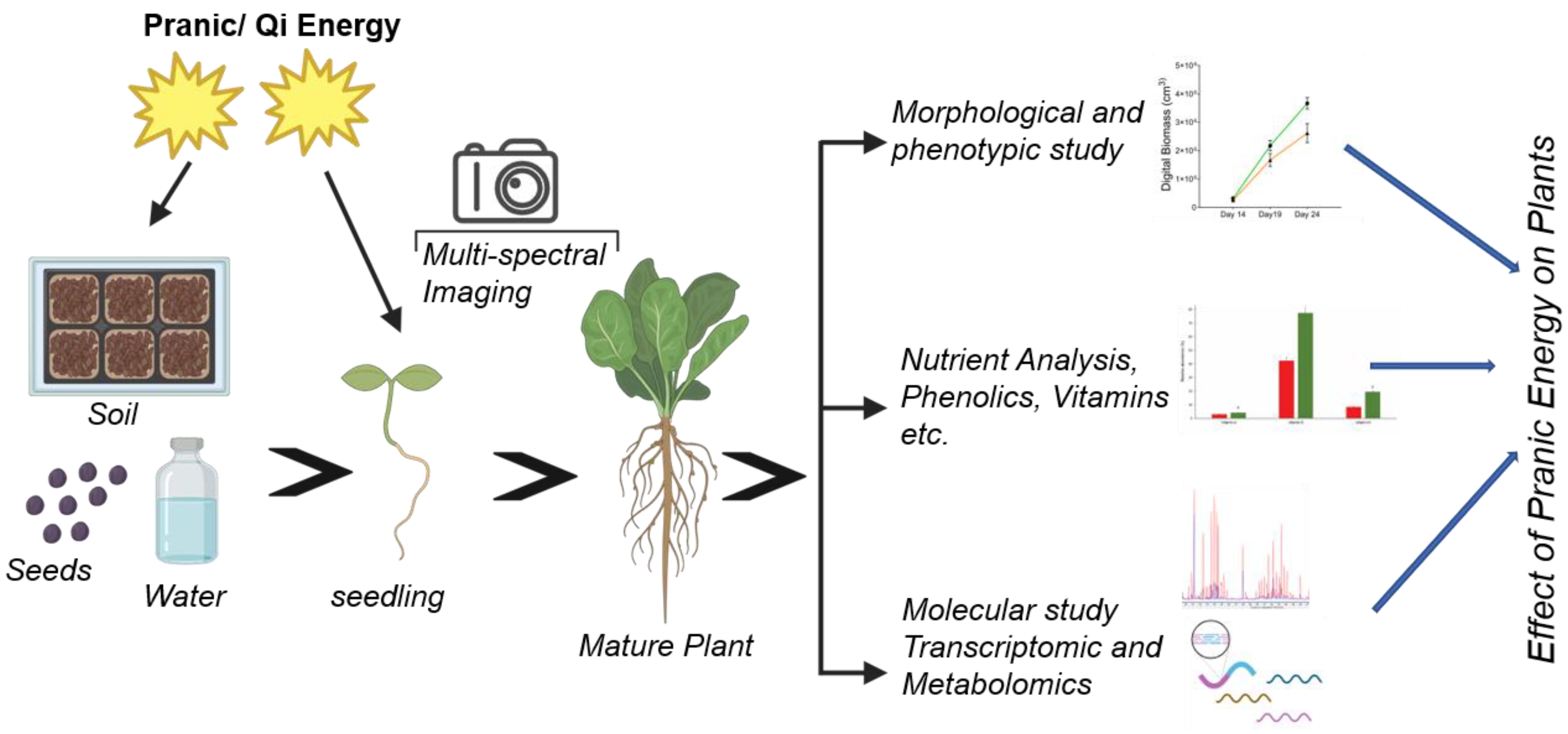

Figure 1.

The overall experimental approach to study the response of plants to ‘Pranic’ energy treatment. All inputs were treated at the start of the experiment. Non-invasive multi-spectral imaging was performed for deep phenotyping of several morphological and physiological traits. Shoots and roots from mature plants were harvested to measure morphological, physiological and molecular metabolic traits.

Figure 1.

The overall experimental approach to study the response of plants to ‘Pranic’ energy treatment. All inputs were treated at the start of the experiment. Non-invasive multi-spectral imaging was performed for deep phenotyping of several morphological and physiological traits. Shoots and roots from mature plants were harvested to measure morphological, physiological and molecular metabolic traits.

Results:

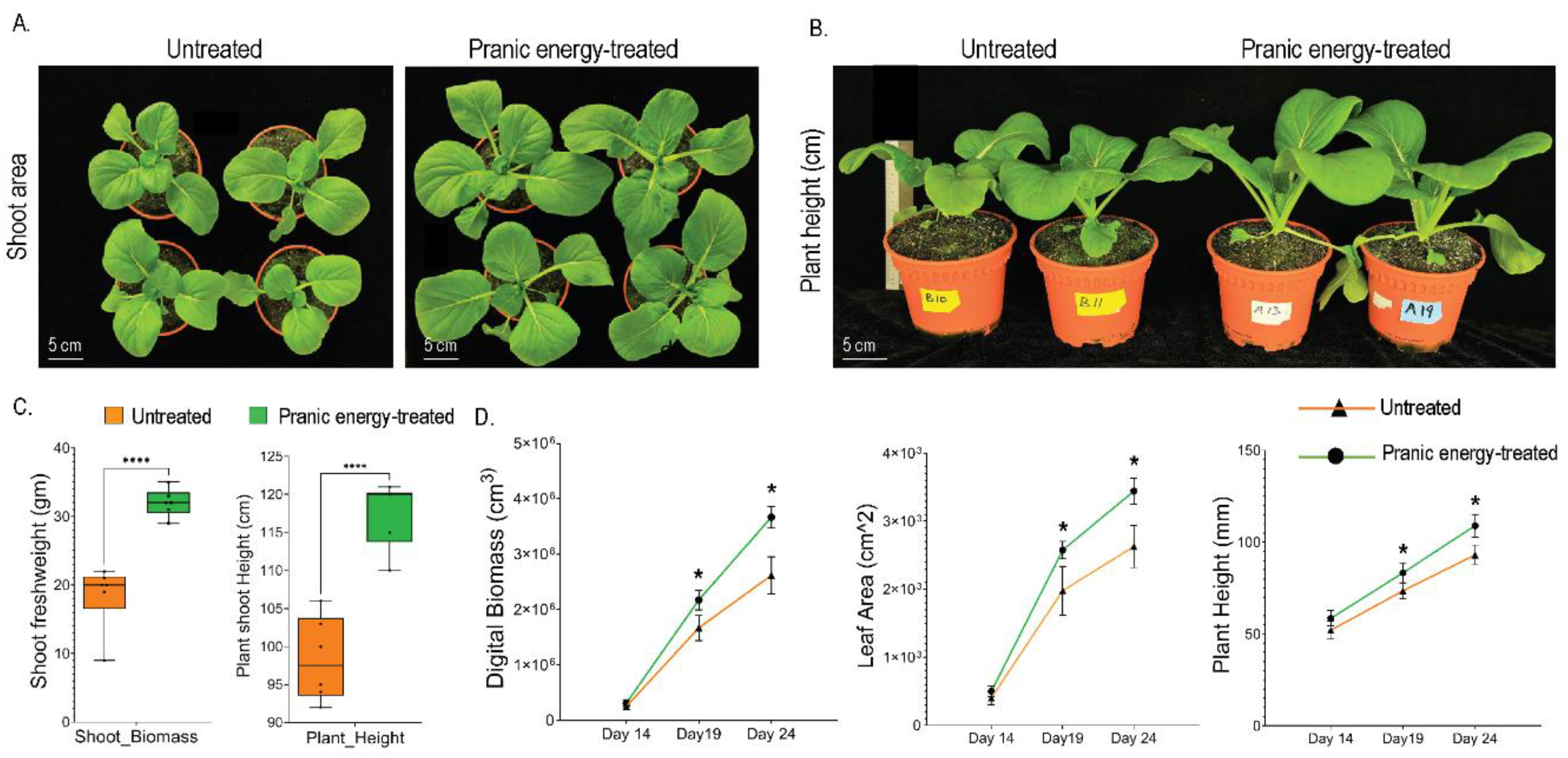

‘Pranic’ Energy Treatment Significantly Increases Shoot Biomass Plant Height

To investigate the effect of ‘Pranic’ energy on plants, Choy-sum plants were chosen due to their short crop cycle of 30 days, suitability for indoor farming, and high nutritional quality, leading to their emerging economic importance as leafy vegetables [

9]. Trained and certified ‘Pranic’ healers applied ‘Pranic’ treatment to the soil, seeds, and water before sowing (Fig. 1). After the initial treatments, the plants and the control set were grown in a controlled environment within the same growth room. Phenotypic, physiological and molecular responses were recorded as shown in Fig 1.

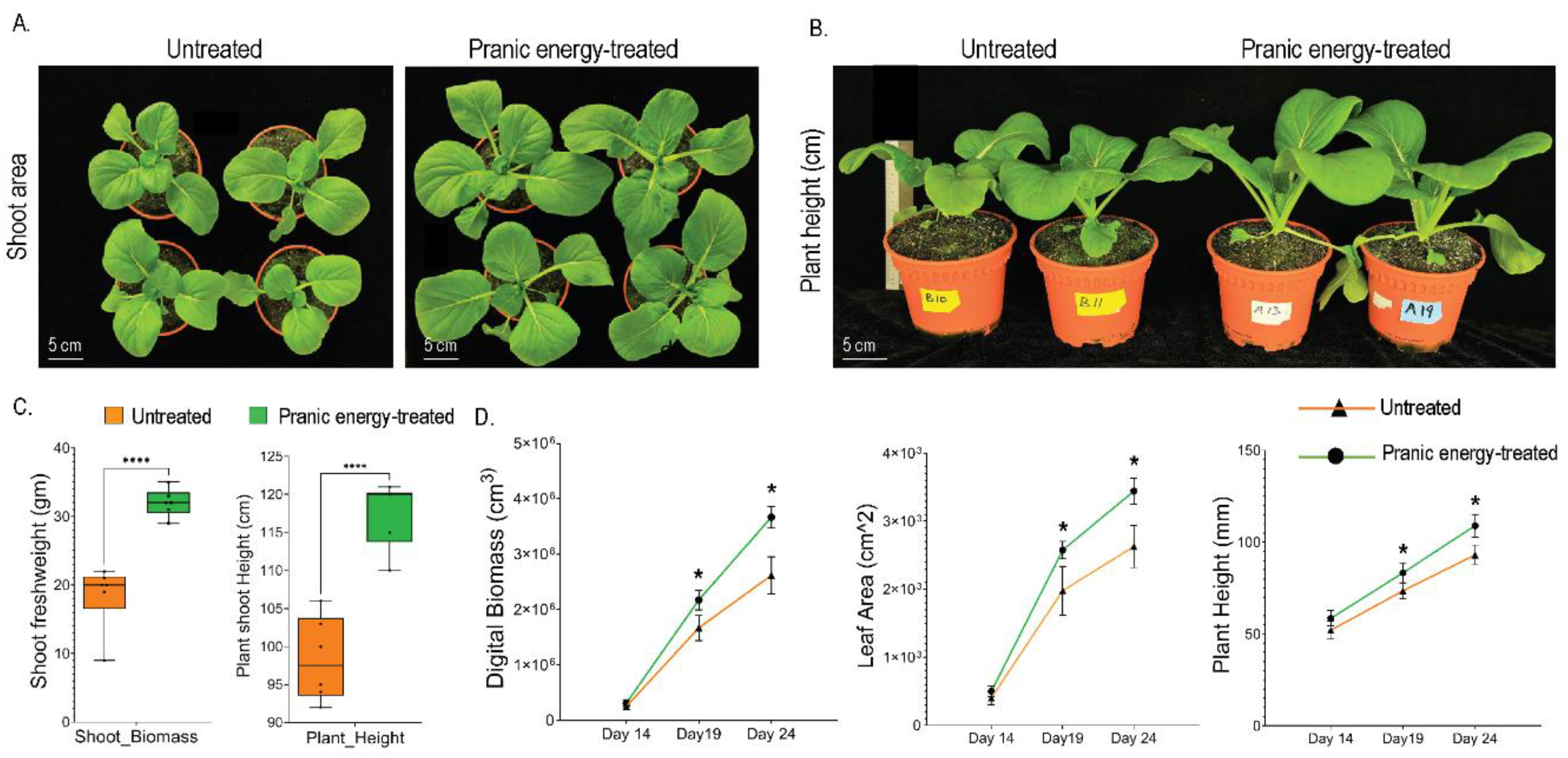

After 21 days of growth, the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants had significantly higher shoot biomass and height, compared to the untreated plants (Fig. 2A, B). ‘Pranic’ energy treatment resulted in 70% increase in shoot biomass and 25% increase in plant height (Fig. 2C). Digitial phenotyping captured both morphological and physiological traits during the different stages of the plant growth. ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants had higher digital biomass, leaf area, and plant height compared to the untreated plants (Fig. 2C). These differences in morphological traits started appearing after 14 days and became more evident throughout the later stages of plant development. Furthermore, to investigate whether the ‘Pranic’ treatment effects could be seen in other crop species, the treatment was applied to Maple pea (

Pisum sativum. var. arvense L) plants by the same practitioners, and the shoot biomass was measured after 11 days of growth. ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants had a nearly 20% increase in shoot biomass compared to the untreated plants (Supp Fig 1). These results demonstrate the positive effects of ‘Pranic’ energy application on plant growth, particularly in terms of increased shoot biomass, height, and various morphological traits.

Figure 2.

Effects of ‘Pranic’ energy treatment on shoot growth of Choy Sum plants. (A) Representative images of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy compared to untreated plants after 21 days of growth; (B) Representative images comparing the plant height of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy and their untreated control plants; (C) Box whisker plots of shoot fresh weight and shoot height of treated and untreated plants after 21 days of growth. Box-plot with whiskers from minimum to maximum value, center lines denote the median values P-values were calculated using an unpaired T-test (n=5) between the treated and untreated samples having ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (D) Non-destructive quantification of leaf digital biomass, leaf area and plant height by multispectral imaging of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy during different growth stages. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the statistical significance between the treated and untreated samples, and an asterisk (*) represents a significant difference (P < 0.05) (n=16). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 1.

Figure 2.

Effects of ‘Pranic’ energy treatment on shoot growth of Choy Sum plants. (A) Representative images of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy compared to untreated plants after 21 days of growth; (B) Representative images comparing the plant height of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy and their untreated control plants; (C) Box whisker plots of shoot fresh weight and shoot height of treated and untreated plants after 21 days of growth. Box-plot with whiskers from minimum to maximum value, center lines denote the median values P-values were calculated using an unpaired T-test (n=5) between the treated and untreated samples having ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (D) Non-destructive quantification of leaf digital biomass, leaf area and plant height by multispectral imaging of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy during different growth stages. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the statistical significance between the treated and untreated samples, and an asterisk (*) represents a significant difference (P < 0.05) (n=16). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 1.

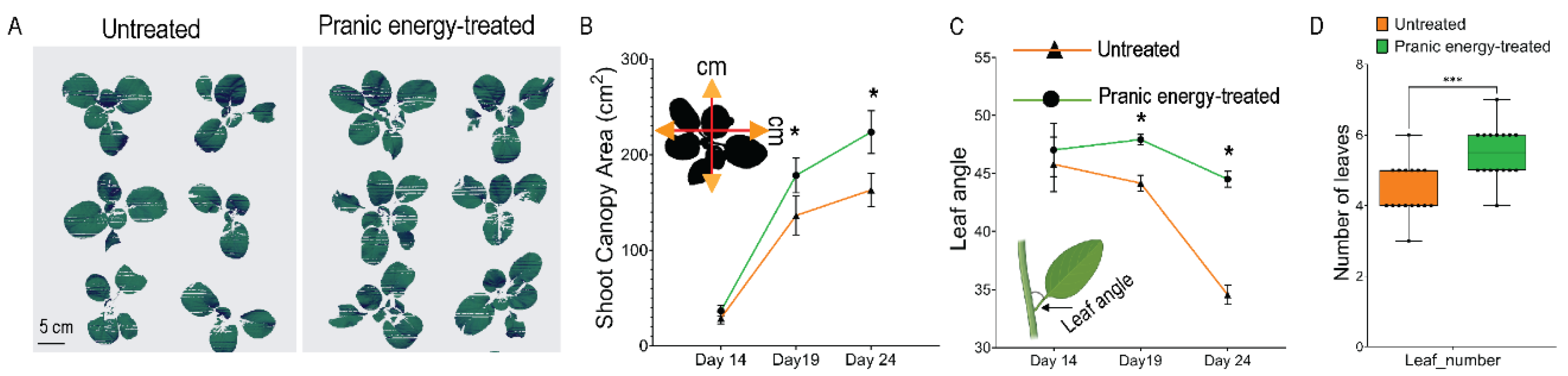

‘Pranic’ Energy Treatment Alters the Shoot Architecture of Plants

To further investigate the phenotypic responses to ‘Pranic’ energy treatment in the plant architecture, we analyzed the multispectral 3D images of the aerial parts of the plants over time (Fig. 3A, Supp Movie 1, 2). Both leaf density and canopy areas increased in the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants (Fig. 3A and B), resulting in increased canopy area as well as canopy density. As the canopy area is also affected by the horizontal spread of the leaves, we further analyzed the leaf angles to test the hypothesis whether the canopy increase was due to larger leaf areas or indeed due to change in architecture. ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants had a higher average angle of leaves to the stems they were attached to (Fig. 3B). This change was not likely from changes in the mechanical properties such as the “stiffening” of the leaves, as their texture analysis and burst strength remained unchanged from ‘Pranic’ energy treatment (Supp Fig. 2). Overall, the phenotypic traits related to shoot architecture suggest that the ‘Pranic’ energy treatments result in the alteration of shoot architecture especially the canopy density and spread.

Figure 3.

‘Pranic’ energy treatment- mediated alteration of shoot architecture in plants. (A) Multispectral images showing the top view of the shoot canopy area of plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy compared to untreated plants. Images also show the number of leaves. (B) Quantitative estimation of shoot canopy area and leaf angle changes over time. The data obtained from multispectral imaging of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy and untreated plants is presented as a line graph. Leaf angle measurement extracted from the spectral image analysis is shown as inset in the bottom right. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the statistical significance between the treated and untreated samples. Asterisk (*) represents a significant difference (P < 0.05) (n=16). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 2.

Figure 3.

‘Pranic’ energy treatment- mediated alteration of shoot architecture in plants. (A) Multispectral images showing the top view of the shoot canopy area of plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy compared to untreated plants. Images also show the number of leaves. (B) Quantitative estimation of shoot canopy area and leaf angle changes over time. The data obtained from multispectral imaging of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy and untreated plants is presented as a line graph. Leaf angle measurement extracted from the spectral image analysis is shown as inset in the bottom right. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the statistical significance between the treated and untreated samples. Asterisk (*) represents a significant difference (P < 0.05) (n=16). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 2.

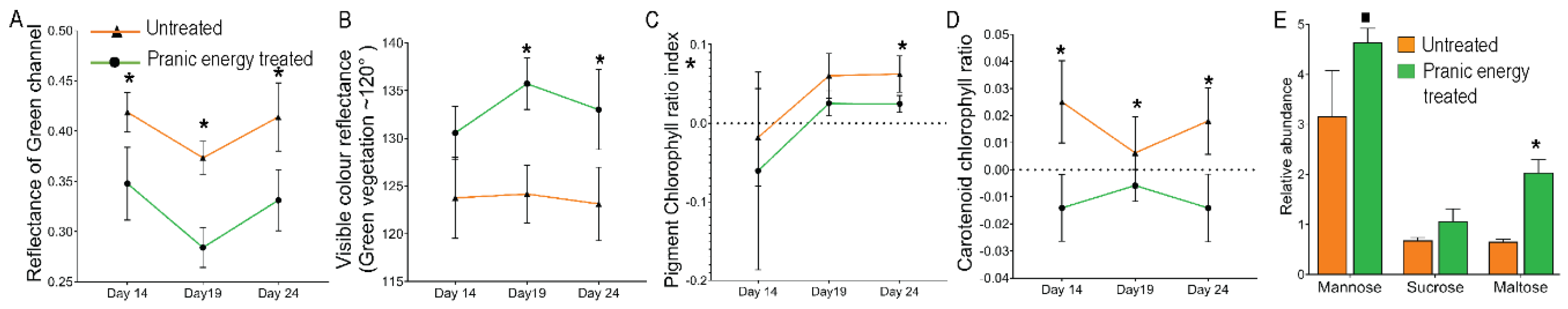

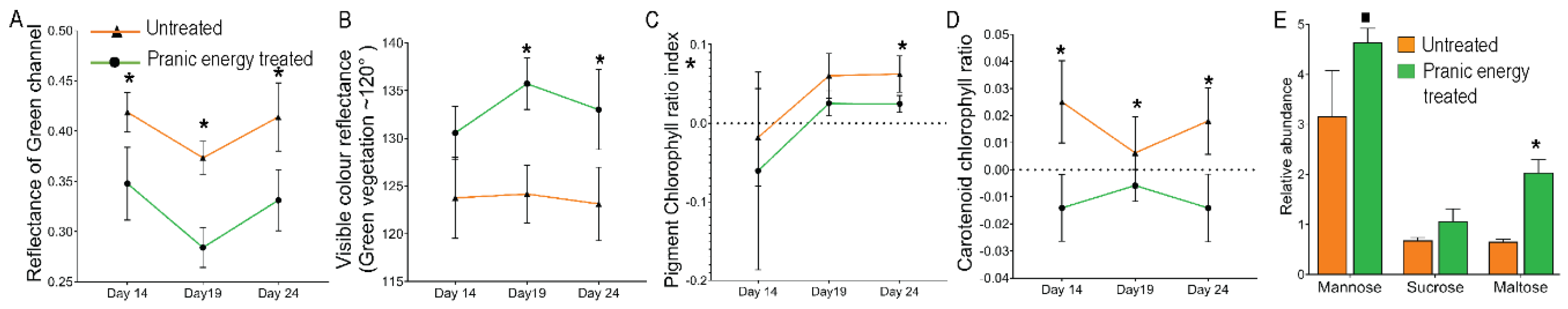

The ‘Pranic’ Energy Treatment Alters the Pigment Content and Increases the Photosynthetic Ability in Plants

Given the positive effects of ‘Pranic’ energy treatments on plant growth and biomass, we next studied the effects of the treatments on the photosynthetic ability and associated physiological parameters of the plants. Initially, measurements of pigment contents and their ratios were conducted in a nondestructive manner using multispectral imaging as a proxy to study certain physiological parameters related to photosynthetic ability.

To assess the greenness of the leaves, the reflectance of the green channel was measured. Higher reflectance in the green channel corresponds to a lower level of greenness. Throughout all growth stages, the ‘Pranic’ energy treated plants exhibited significantly less reflectance in the green channel compared to the untreated plants (Fig. 5A) indicating more greenness in the leaves upon treatments. Additionally, reflectance measurements for all visible colors, dependent on wavelength, were greater than the unit value of 120 for both treated and untreated plants, indicating the greenness as per the machine parameters. However, the ‘Pranic’ energy -treated plants showed significantly higher values compared to the untreated plants (Fig. 5B), suggesting the presence of more green pigments in the treated plants. Furthermore, we analyzed the reflectance data of different color spectrum channels from the multispectral images to calculate the pigment/ chlorophyll content ratios. The ratio of reflected red light in the red-blue and red-green channels serves as a proxy for chlorophyll content in plants. Similarly, the ratio of red-green to the near infra-red channels serves as a proxy for carotenoid/chlorophyll content and thus proxy for leaf senescence. In both the cases, a lower ratio corresponds to a higher chlorophyll content. As expected, the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants exhibited lower values in both the cases compared to the untreated plants (Fig. 5C, D), indicating a higher chlorophyll content following the treatments.

To validate the proxy values for higher chlorophyll content and photosynthetic ability, further analysis was conducted to quantify the photosynthates from the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated leaves.

Figure 5.

‘Pranic’ energy-mediated alteration of pigment-chlorophyll ratio and primary sugar contents in leaves. (A), (B), (C) & (D) Quantitative data from multispectral imaging of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy and untreated plants. The levels and ratios of different pigments and chlorophyll contents were measured by the reflectance analysis of specific wave length from a spectrum of colour channels. The imaging was done at different times, and the data is shown as line graphs to visualize the changes in pigment content and ratios over the growth period between '‘Pranic’' energy-treated and untreated plants. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the statistical significance between the treated and untreated samples. Asterisk (*) represents a significant difference (P < 0.05) (n=16). (E) The bar graph represents the relative abundance of primary sugar levels in the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated and untreated plant leaves after 21 days of growth. Significant differences are marked with asterisk (t-test with ‘*’ p<0.05 and ‘.’ P<0.1, n=3). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 4.

Figure 5.

‘Pranic’ energy-mediated alteration of pigment-chlorophyll ratio and primary sugar contents in leaves. (A), (B), (C) & (D) Quantitative data from multispectral imaging of Choy Sum plants treated with ‘Pranic’ energy and untreated plants. The levels and ratios of different pigments and chlorophyll contents were measured by the reflectance analysis of specific wave length from a spectrum of colour channels. The imaging was done at different times, and the data is shown as line graphs to visualize the changes in pigment content and ratios over the growth period between '‘Pranic’' energy-treated and untreated plants. Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the statistical significance between the treated and untreated samples. Asterisk (*) represents a significant difference (P < 0.05) (n=16). (E) The bar graph represents the relative abundance of primary sugar levels in the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated and untreated plant leaves after 21 days of growth. Significant differences are marked with asterisk (t-test with ‘*’ p<0.05 and ‘.’ P<0.1, n=3). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 4.

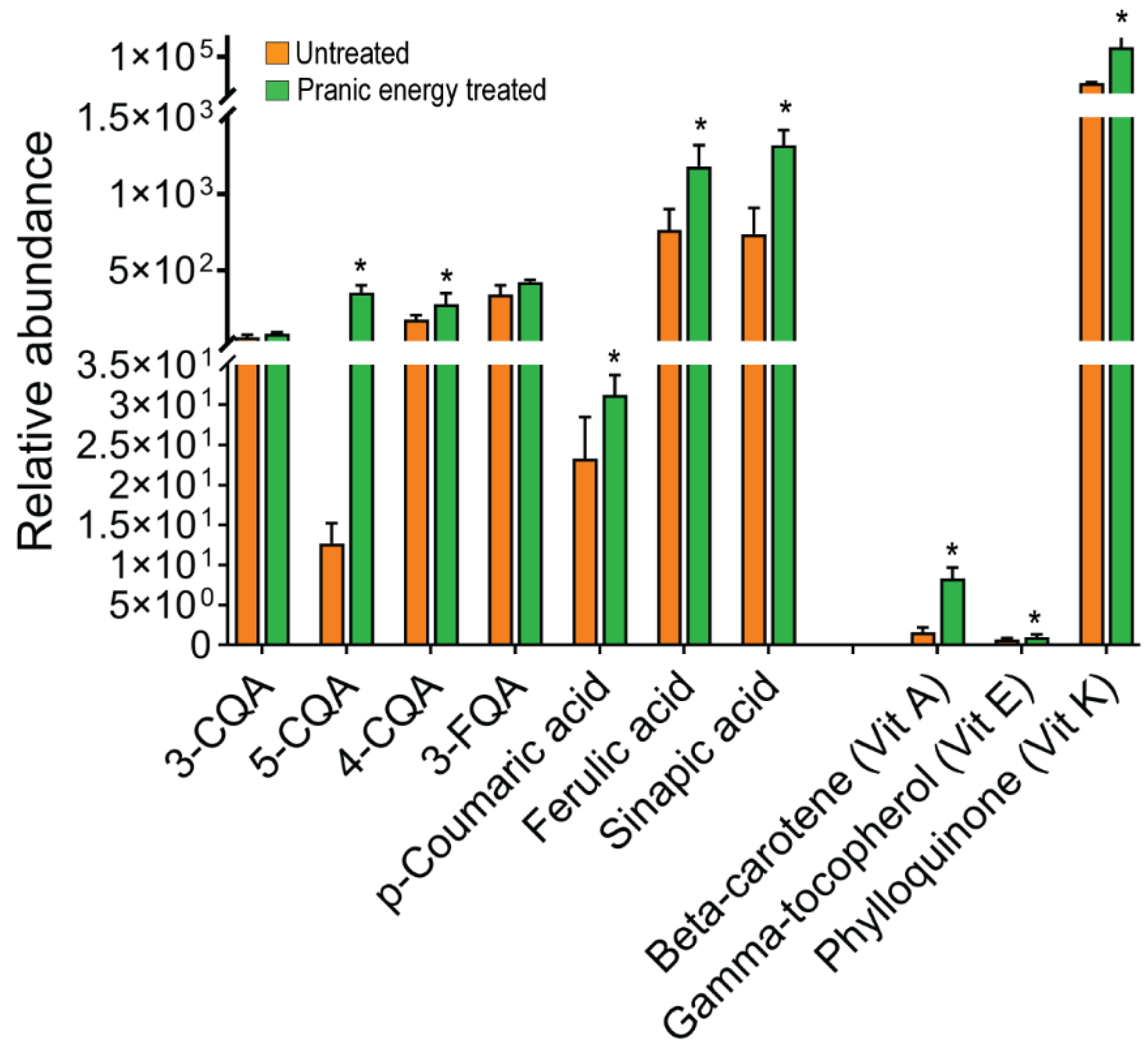

‘Pranic’ Energy Treatment Increases Nutritional Content of the Plants

The distribution of major phenolics and vitamins in untreated and ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants were analyzed to understand the effects of the treatment on the nutritional content. Major phenolic compounds were significantly increased in the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants, compared to the untreated plants (Fig 6). These phenolic compounds included both caffeoylquinic and feruloylquinic classes such as 3-CQA (3-Caffeoylquinic acid), 5-CQA (5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid), 4-CQA (4-O-Caffeoylquinic acid), and 3-FQA (3-Feruloylquinic acid). Similarly, major vitamins were significantly increased in the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants, compared to the untreated plants. Among the vitamins analyzed, vitamin E showed the highest content, followed by vitamin K and vitamin A. These findings highlight the positive impact of ‘Pranic’ energy treatment through a potential enhancement of the nutritional value and antioxidant properties of plants.

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of some selected phenolics and vitamins in untreated and ‘Pranic’ energy- treated plants. Significant differences are marked with asterisk (t-test with p<0.05).. 3-CQA: 3-Caffeoylquinic acid, 5-CQA: 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, 4-CQA: 4-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, 3-FQA: 3-Feruloylquinic acid; Beta-Carotene (vitamin A); Gamma-Tocopherol (vitamin E); Phylloquinone (vitamin K). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 5.

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of some selected phenolics and vitamins in untreated and ‘Pranic’ energy- treated plants. Significant differences are marked with asterisk (t-test with p<0.05).. 3-CQA: 3-Caffeoylquinic acid, 5-CQA: 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, 4-CQA: 4-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, 3-FQA: 3-Feruloylquinic acid; Beta-Carotene (vitamin A); Gamma-Tocopherol (vitamin E); Phylloquinone (vitamin K). The data has been shared in the supplementary table 5.

Discussion

Plant productivity is closely related to soil nutrients, soil microflora, and climatic conditions. In recent years, several attempts have been made to initiate sustainable agricultural strategies by reducing the use of conventional agricultural inputs in crop improvement programs. In this context, non-conventional methods are being utilised to test their efficacy in improving plant growth. For instance, the use of sound waves and various electromagnetic waves have been successfully adopted to increase plant growth without any application of chemical fertilizers [

10,

11]. As a non-conventional method, ‘Pranic’ energy treatment, a well-recognized energy healing modality has been increasingly applied in various scenarios, including traditional agriculture

3 and treatment of human ailments [

12,

13]. Here, standardised protocols were used to project ‘Pranic’ energy from the hands to treat the plants in a well-controlled indoor growth facility. This study provides compelling evidence that ‘Pranic’ energy application significantly alters various phenotypic and physiological traits, and improves the yield and nutritional quality of the treated plants. It significantly enhances shoot and root biomass, alters shoot architecture, increases photosynthetic capacity, and improves nutritional content, suggesting a broader applicability of this treatment for sustainable agricultural practices. In addition, here we also make a case for the use of the plant systems to gain a deeper understanding of the phenotypic and physiological responses to the ‘Pranic’ energy treatment.

Our results demonstrate that ‘Pranic’ energy application leads to a substantial increase in shoot biomass, leaf area, and plant height (Fig. 2), which aligns with several previous reports of ‘Pranic’ energy-mediated enhancements of plant growth and yields in open fields [

3]. The mechanical properties of the leaves, such as burst strength, remained unaffected, indicating that the structural integrity of the leaves was not compromised by the treatment. Interestingly, the canopies of the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants were larger, indicating a more open conformation than the non-treated control plants (Fig. 3). Combination of both an increase in the leaf angle and the increase in leaf area can explain the larger canopy area. This architectural modification, with more horizontally placed leaves, likely contributes to enhanced capture and utilization of the ‘Pranic’ energy, thereby promoting overall plant growth.

The physiological changes in response to the ‘Pranic’ energy treatment strongly indicate an increase in the photosynthetic efficiency. Both energy capture and resulting sugars showed significant improvements upon ‘Pranic’ energy treatment. The reduced reflectance in the green channel along with the lower reflectance ratios of red-blue and red-green wavelengths from the multi-spectral imaging analysis indicate higher chlorophyll levels (Fig. 5). Leaves with more chlorophyll are better able to absorb the light required for photosynthesis [

14,

15]. The increase in sugar content in the ‘Pranic’ energy-treated plants (Fig. 5E) also validates higher rate of photosynthesis. From a nutritional perspective, the increased sugar content is immensely beneficial for consumers [

16]. Therefore, the higher photosynthetic efficiency may also improve the overall nutritional value of the treated plants.

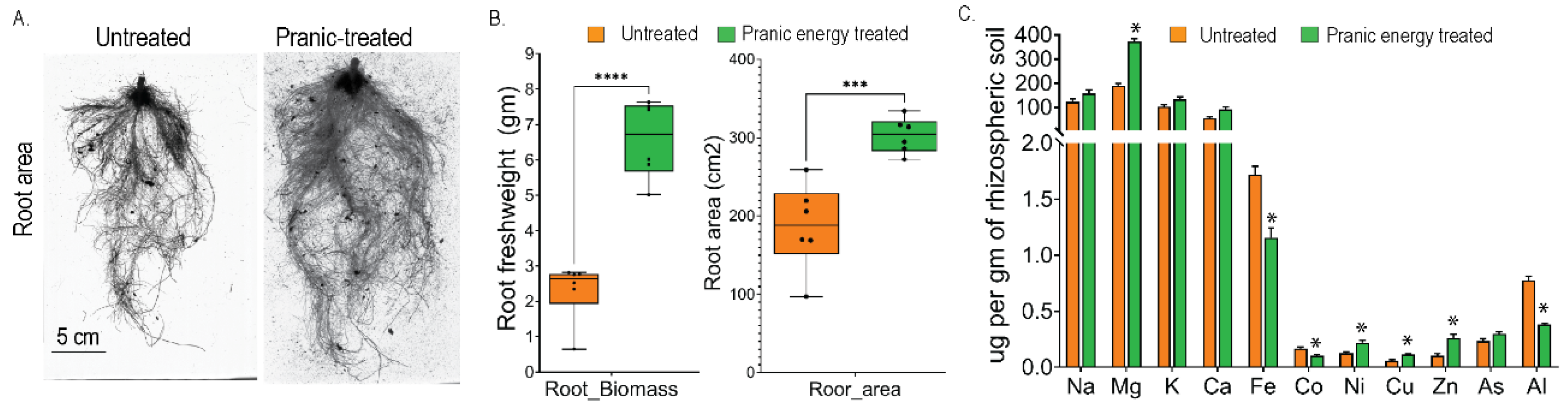

The ‘Pranic’ energy application also led to a significant increase in the root biomass and volume (Fig. 4). A more extensive root system will be able to support water and nutrient uptake from the soil more efficiently. Higher absorption of specific essential metals from the root system will, therefore, lead to a correspondingly lesser amount of those metals in the rhizospheric soil. Towards this, the levels of Ni, Zn and Mg ion concentrations were lower, while those of Al, Fe, and Co were higher in the rhizospheric soil (Fig. 4C). The uptake of different micronutrients, especially Fe and Co from the soil, has a direct effect on the growth and development of plants [

17]. These differential absorption patterns suggest that ‘Pranic’ energy treatment modulate root physiology and ion transport mechanisms, optimizing nutrient uptake for better growth and development.

In addition to promoting growth, ‘Pranic’ energy application positively impacts the nutritional content of Choy-sum plants. Our analysis revealed significant increases in major phenolic compounds and vitamins, including vitamins A, E, and K in ‘Pranic’-treated plants (Fig. 6). Notably, the observed increase in certain phenolics, namely p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and sinapic acid (Fig. 6), is particularly important as these compounds are known wall-bound phenolics [

18] that contribute to the strengthening of the plant cell wall [

19]. Additionally, the elevation of soluble phenolics, including various caffeoylquinic acids, indicates higher nutritional value [

16], given their well-documented antioxidant and protective functions [

20]. The higher phenolic content may enhance the antioxidant properties of the plants, offering potential health benefits when consumed as leafy vegetables. The increased vitamin content further adds to the nutritional value of ‘Pranic’-treated Choy-sum, making it a more nutritious food source. Vitamin K plays a crucial role as an electron carrier in the chloroplast photosynthetic membrane [

21], which aligns with the higher photosynthetic capability observed in ‘Pranic’-treated plants. Vitamin E, known for its antioxidant and free-radical scavenging activity [

22], also regulates lipid peroxidation in chloroplasts [

23]. Therefore, the elevated levels of vitamin E in ‘Pranic’-treated plants may account for the enhanced growth rate of plant biomass.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that ‘Pranic’ energy application has wide-ranging benefits to plant growth both above and below ground. Such growth would require overall increase in the metabolic resources. The overall changes in the plant architecture, combined with increased photosynthetic efficiency and enhanced root system could explain an increase in the metabolic resources of the ‘Pranic’ treated plants for their partitioning into both above and below ground portions. These findings highlight the potential of ‘Pranic’ energy as a novel and effective strategy for promoting plant growth and improving crop quality. The application of the ‘Pranic’ energy treatment in agriculture is not a substitute but it complements existing agricultural practices. Future research can focus on elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms of the ‘Pranic’ energy treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and ‘Pranic’ treatment, S.S; manuscript conceptualization and original draft preparation, SS., & M.M.; Plant phenotype experiments and data collections, SM; sugar and nutritional analysis, RB; Formal Analysis and visualization, M.M., Writing – Review & Editing; P.S., Z.l., O.N., V.R., & G.M.; Funding Acquisition, S.S., G.M.; Supervision, S.S.

Funding

This research was funded by Center for Pranic Healing, USA and Pranic Healing Research Institute PHRI, USA.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National University of Singapore for providing the laboratory infrastructure. We acknowledge Dr. Zou Li and Dr. Ong Choon Nam from Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore for providing standards for the vitamin analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Poornima, R. (2020). Influence of pranic agriculture technique on growth and yield of Marigold, tagetes erecta. Bioscience Biotechnology Research Communications 13, 2001–2007. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K. N., and Jois, S. N. (2020). Enhancement of papaya (Carica papaya) seedling growth by Pranic Agriculture. AGRIVITA Journal of Agricultural Science 42. [CrossRef]

- Jois, S. N., Roohie, K., D’Souza, L., Suma, F., Devaki, C. S., Urooj, A., et al. (2017). Physico-chemical qualities of tomato fruits as influenced by pranic treatment - an ancient technique for enhanced crop development. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 9. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K. N. (2020). Effect of pranic agriculture on vegetative growth characteristics of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). Indian Journal of Science and Technology 13, 2446–2451. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K. N., Vinu, V., and Jois, S. N. (2023). Application of pranic agriculture to improve growth and yield of banana (Musa sp. var. Nanjangud Rasa Bale)-a comparative field trial. Agricultural Science Digest - A Research Journal. [CrossRef]

- R, P., K, N. P., HA, Y., and Jois, S. (2021). Influence of pranic agriculture in enhancing growth and yield of Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) and its genetic analysis. Egyptian Journal of Agricultural Research 99, 242–247. [CrossRef]

- Du, H., Wang, X., Yang, H., Zhu, F., Tang, D., Cheng, J., & Liu, X. (2022). Changes of phenolic profile and antioxidant activity during cold storage of functional flavored yogurt supplemented with mulberry pomace. Food Control, 132, 108554. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S., & Mitra, A. (2024). Histochemical, metabolic and ultrastructural changes in leaf patelliform nectaries explain extrafloral nectar synthesis and secretion in clerodendrum chinense. Annals of Botany, 133(4), 621–642. [CrossRef]

- Tan, W. K., Goenadie, V., Lee, H. W., Liang, X., Loh, C. S., Ong, C. N., et al. (2020). Growth and glucosinolate profiles of a common Asian green leafy vegetable, brassica rapa subsp. chinensis var. parachinensis (Choy Sum), under LED lighting. Scientia Horticulturae 261, 108922. [CrossRef]

- Ayesha, S., Abideen, Z., Haider, G., Zulfiqar, F., El-Keblawy, A., Rasheed, A., et al. (2023). Enhancing sustainable plant production and food security: Understanding the mechanisms and impacts of electromagnetic fields. Plant Stress 9, 100198. [CrossRef]

- Van Dar Ende, M. (2022). Device and method for directing plant development.

- Rosch, P. J. (2009). Bioelectromagnetic and subtle energy medicine. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1172, 297–311. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Tan, X., Shi, H., and Xia, D. (2020). Nutrition and traditional chinese medicine (TCM): A System’s theoretical perspective. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 75, 267–273. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., and van Iersel, M. W. (2021). Photosynthetic physiology of Blue, Green, and Red Light: Light intensity effects and underlying mechanisms. Frontiers in Plant Science 12. [CrossRef]

- Demmig-Adams, B., Stewart, J. J., and Adams, W. W. (2017). Environmental regulation of intrinsic photosynthetic capacity: An integrated view. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 37, 34–41. [CrossRef]

- Azaïs-Braesco, V., Sluik, D., Maillot, M., Kok, F., & Moreno, L. A. (2017). A review of total & added sugar intakes and dietary sources in Europe. Nutrition journal, 16, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Arif, N., Yadav, V., Singh, S., Singh, S., Ahmad, P., Mishra, R. K., et al. (2016). Influence of high and low levels of plant-beneficial heavy metal ions on plant growth and development. Frontiers in Environmental Science 4. [CrossRef]

- Cocuron, J. C., Casas, M. I., Yang, F., Grotewold, E., & Alonso, A. P. (2019). Beyond the wall: High-throughput quantification of plant soluble and cell-wall bound phenolics by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 1589, 93-104. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Deng, Z., & Tsao, R. (2020). A review on insoluble-bound phenolics in plant-based food matrix and their contribution to human health with future perspectives. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 105, 347-362. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Estrada, B. A., Gutiérrez-Uribe, J. A., & Serna-Saldívar, S. O. (2014). Bound phenolics in foods, a review. Food chemistry, 152, 46-55. [CrossRef]

- Spicher, L., & Kessler, F. (2015). Unexpected roles of plastoglobules (plastid lipid droplets) in vitamin K1 and E metabolism. Current opinion in plant biology, 25, 123-129. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. (2014). Natural forms of vitamin E: metabolism, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities and their role in disease prevention and therapy. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 72, 76-90. [CrossRef]

- Traber, M. G., & Atkinson, J. (2007). Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more. Free radical biology and medicine, 43(1), 4-15. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).