This study investigates the learning outcomes of 12th-grade students of professional high school in the informatics profile regarding the topic of numerical sequences. Through comparing results from pre-test, post-test, observation list, questionnaire with open questions for student, it became evident that students often encounter difficulties in understanding and applying numerical sequences due to the abstract way the topic is traditionally introduced in school curricula. Textbook examples typically lack context or connection to real-life situations, which limits students’ ability to engage meaningfully with the material and develop conceptual understanding.

These findings are consistent with existing literature that highlights how abstract mathematical instruction, devoid of real-world application, can hinder students’ motivation and comprehension. Traditional instruction dominated by teacher-centered methods and uniform examples-often fails to foster the analytical and inquiry-based learning that is crucial at the upper secondary level (Artigue & Blomhøj, 2013).

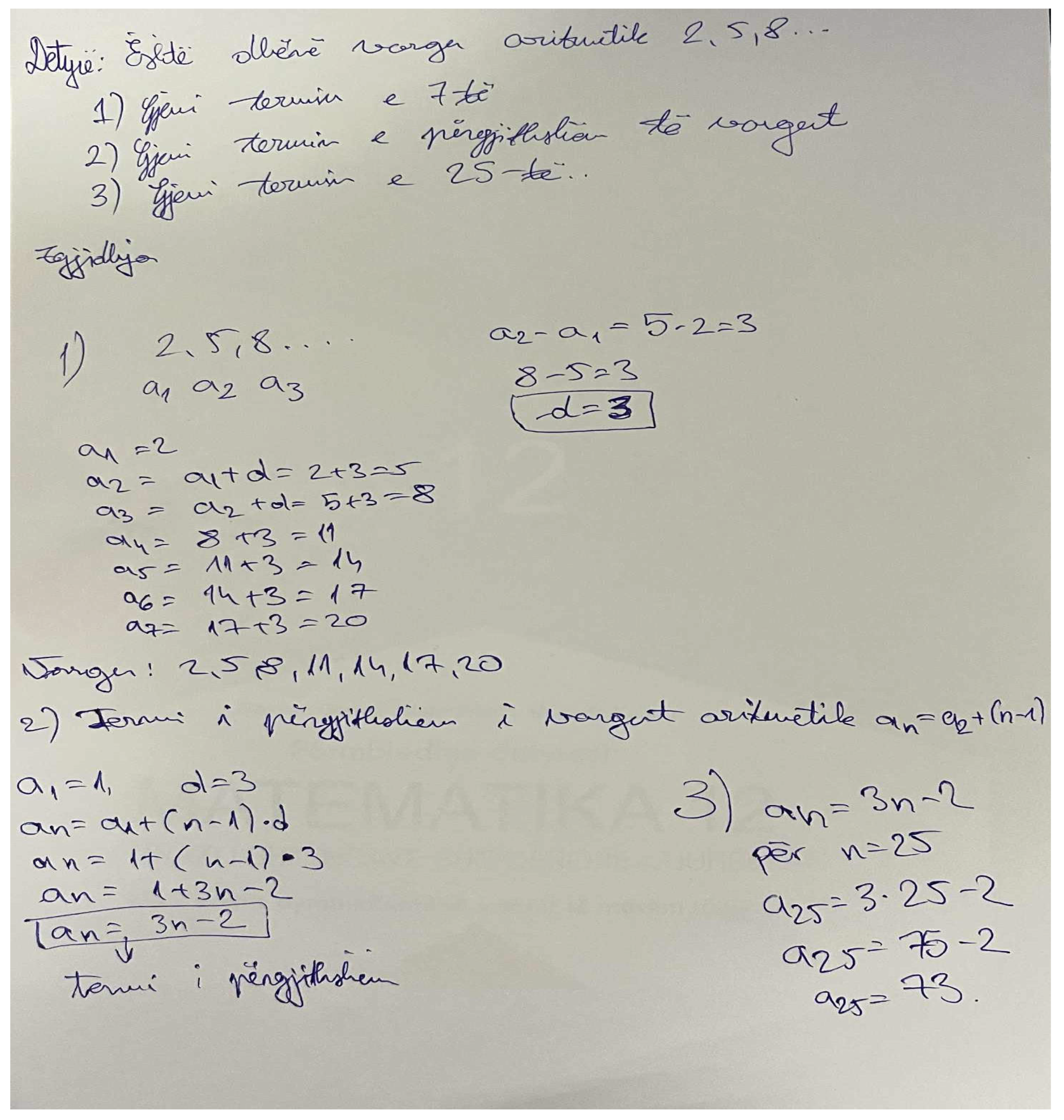

3.2. Real-World Examples Used in the Experimental Group for Teaching Numerical Sequences

Experimental group

Case Example 1: Triangular numbers as a contextualized learning task

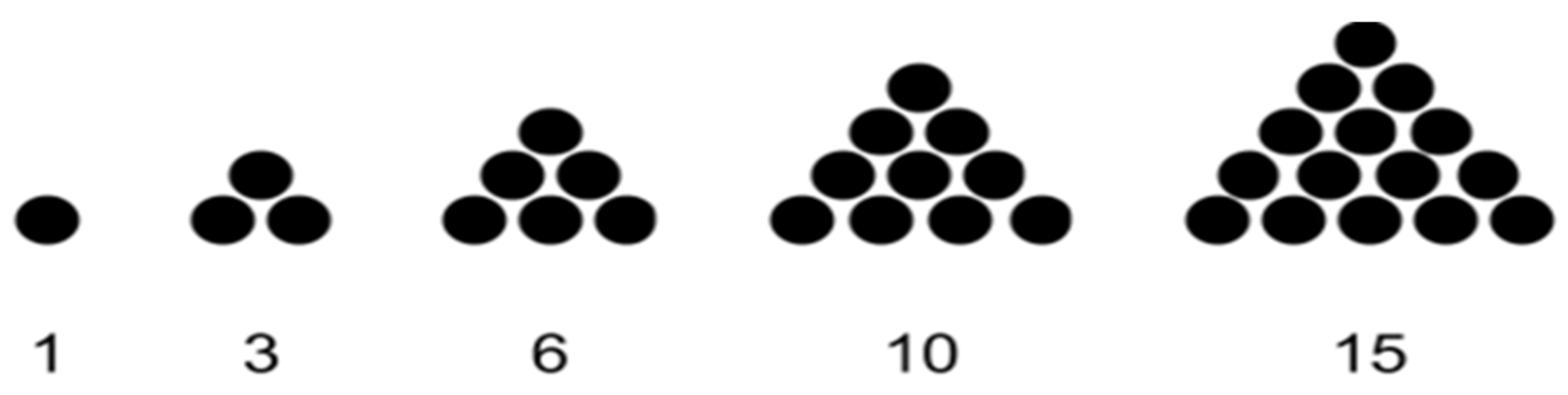

One of the classroom tasks introduced involved a visual and constructive approach to triangular numbers:

Scenario: The teacher posed a problem where students were to build geometric shapes using balls, arranging them into triangular patterns. Starting with one ball, each new term in the sequence involved increasing the number of balls per row to form a larger triangle. |

This led to the construction of the following numerical sequence:

Sequence: 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, ...

Student tasks:

Represent the sequence visually.

Find the sum of the first five terms.

Derive a general formula for the sequence.

Student strategy and solution:

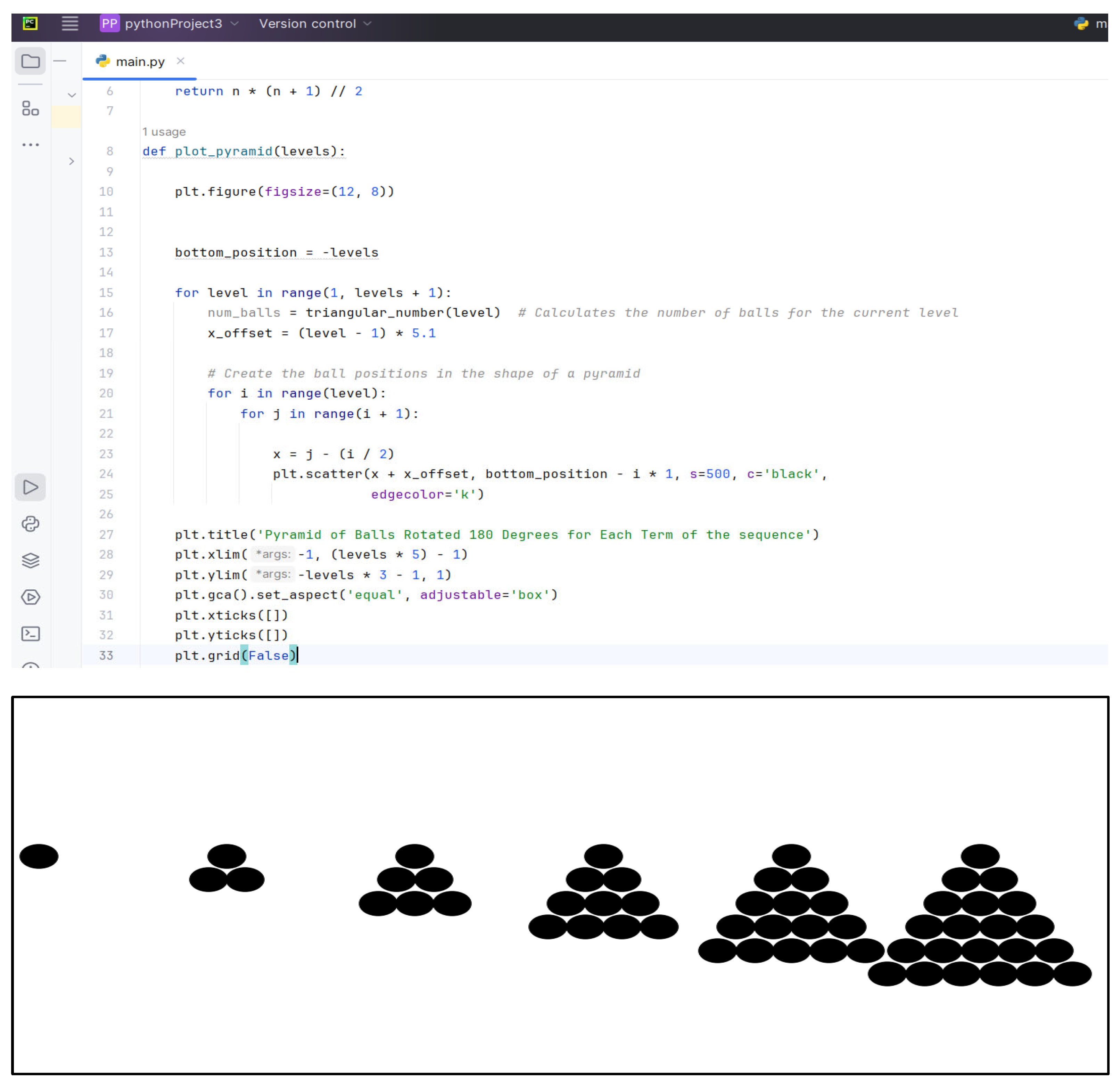

Task 1. Students explored the number pattern using both visual construction and analytical reasoning

Figure 2.

The numerical sequence obtained with balls placed according to a triangular rule.

Figure 2.

The numerical sequence obtained with balls placed according to a triangular rule.

One of the most common strategies students use when solving these problems is constructing tables and filling in their values, using the set of natural numbers as a reference for indexing the terms of the numerical sequence (see

Table 2).

| Task 2. They the sum calculated of the first five terms as: |

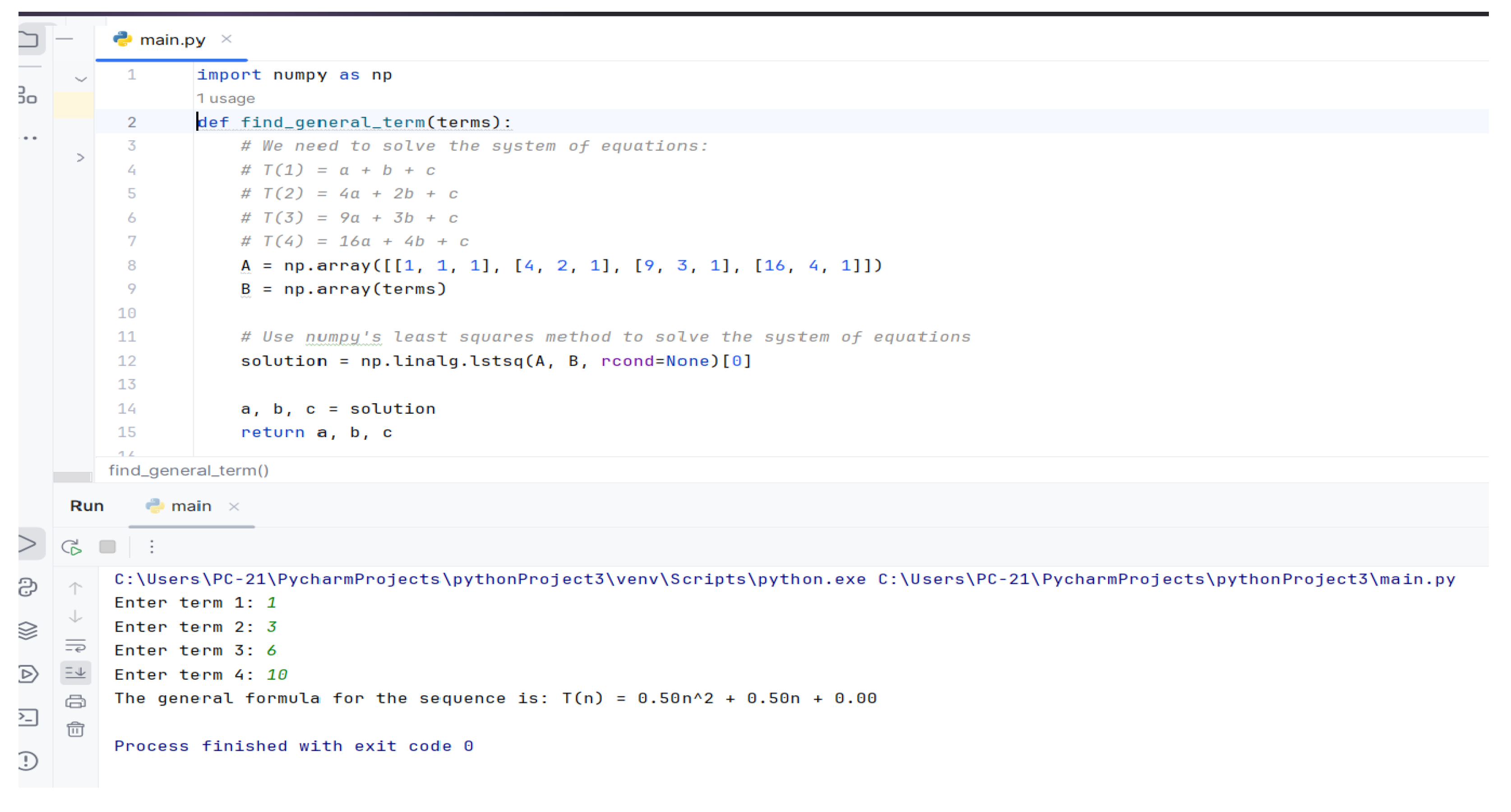

The sequence was identified as increasing, non-arithmetic, non-geometric, and unbounded. To determine the general term, students used Python programming to visualize and simulate the pattern and derive the closed-form formula.

Task 3. Students explored the number pattern using both visual construction and analytical reasoning:

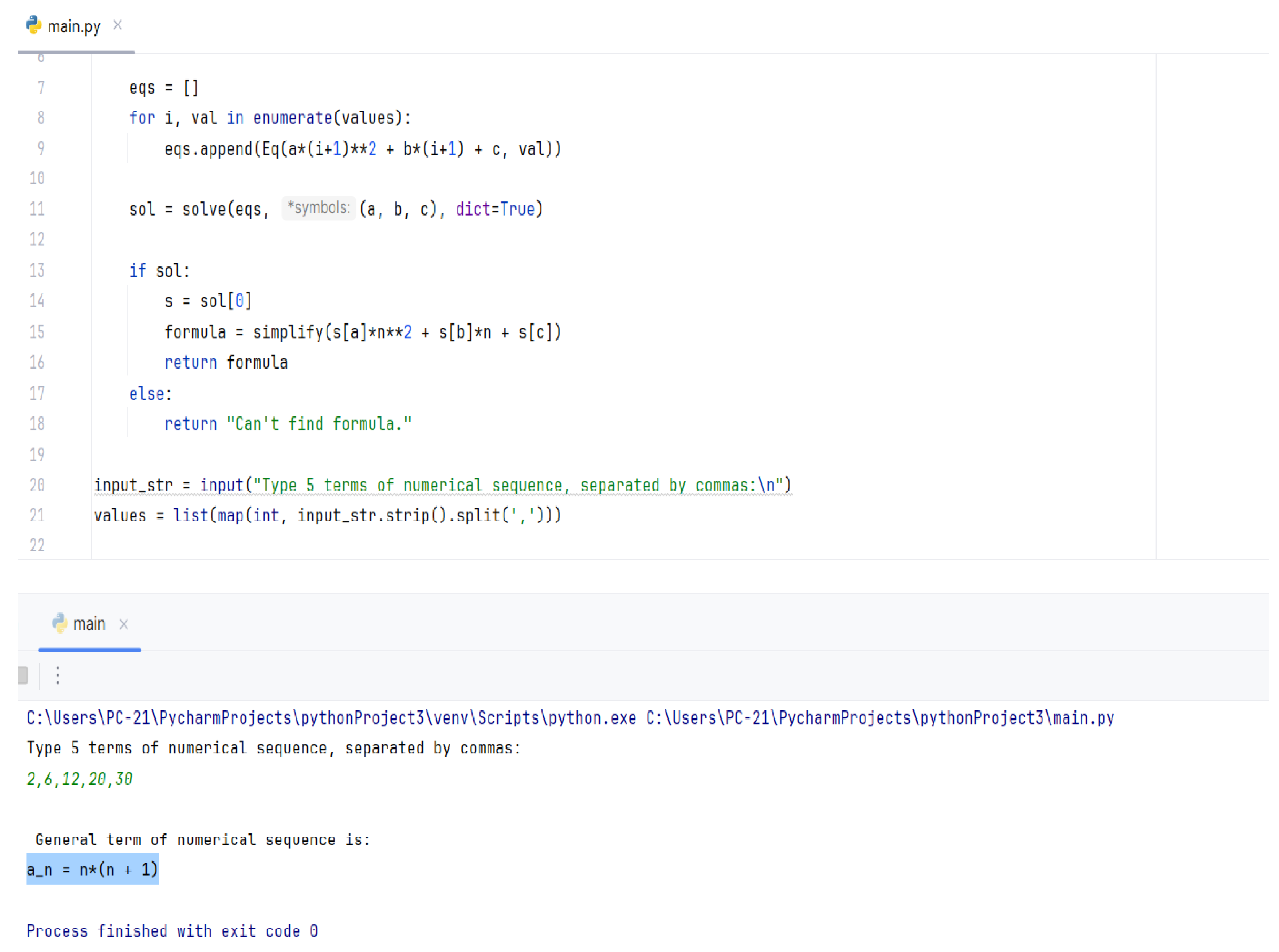

Figure 3.

Finding general term by Python programming.

Figure 3.

Finding general term by Python programming.

This computational approach reinforced students’ understanding of the pattern and helped them derive the general term:

, or

Using Python as a learning tool allowed students to test hypotheses, verify solutions, and visualize how terms evolve an approach aligned with studies emphasizing the pedagogical benefits of integrating digital tools in mathematics instruction [

24,

25].

Qualitative observations and interpretation:

- a)

Present this numerical sequence in visual we find the terms by adding the balls according to the rule.

- b)

Also we found the sum of the first 5 terms of the numerical sequence by adding the values of the terms found through the graphical representation which is the same by formula

- c)

By Python programming, we have found the general term

Using Python Programming, we can find visual presentation of the numerical sequence as shown in

Figure 4.

Throughout this and similar tasks, several key outcomes were noted:

- I.

Increased engagement: Students were more motivated to participate when problems were grounded in visual or real-life contexts.

- II.

Improved conceptual understanding: The use of visual aids and programming facilitated deeper comprehension of sequence properties.

- III.

Enhanced reasoning: Students were able to explain their reasoning processes and describe the transition from concrete models to generalization.

This analysis supports findings from international research that contextual and technological interventions can significantly improve students' mathematical literacy and engagement [

26,

27].

Experimental group

Case 2 example: In a library, books are placed vertically on shelves following a set rule:

A single book is placed on the top shelf, two books on the second shelf, four on the third, eight on the fourth, sixteen on the fifth, and so on, doubling the number of books each time until the last shelf. |

Sequence: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16,…

Student task:

Find the number of books arranged from the first shelf to the 5th shelf?

Find the general term of the resulting sequence

How many books are arranged on the 7th shelf

How many shelves should this bookstore have so that at least 511 books can be arranged?

Solution: Identifying concepts and mathematical relationships

Since the ratio of two consecutive terms of this series is constant, then:

Then we can say that it is a geometric sequence and the difference between any two consecutive terms is constant .

Problem-solving strategy and process

Based on the rule for forming a geometric sequence, we form the table (see

Table 3):

Using formula: where the sum of the first 5 terms of the sequence is .

Explanation of the solution to the problem:

We analyze the properties of this numerical sequence: arithmetic, geometric, increasing, decreasing, bounded, unbounded, etc. The given sequence is not arithmetic, it is geometric, it is increasing and unbounded.

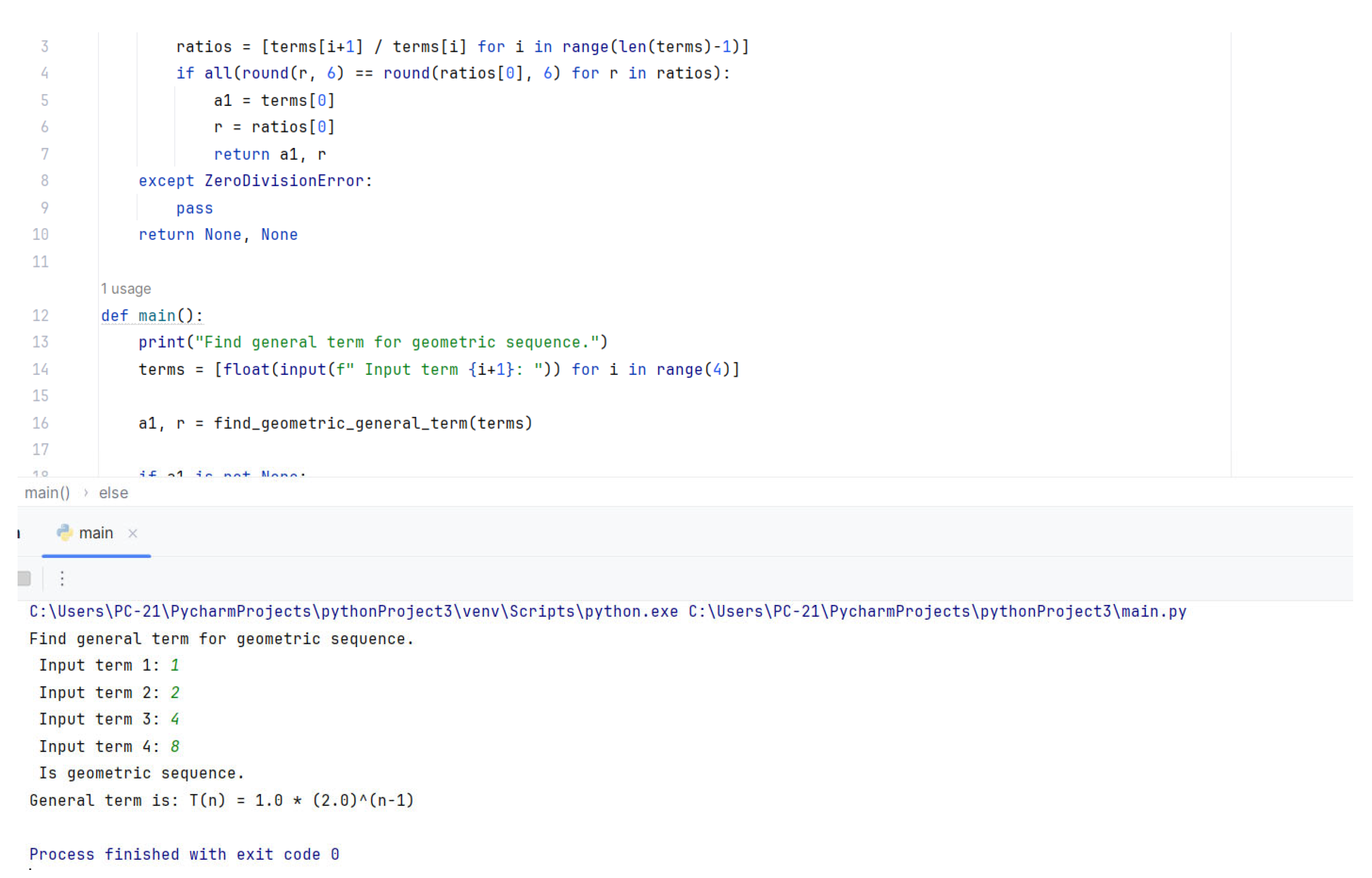

The general formula for a geometric sequence is given by: and finding the general term using the geometric sequence formula is: To make it easier to find the general term, we use Python programming and see that the general term is:

Figure 5.

Finding the general term for a geometric sequence by Python.

Figure 5.

Finding the general term for a geometric sequence by Python.

Through Python programming, we have found the general term

We found the sum of the first 5 terms of the geometric sequence

by adding the values of the terms found through the representation in table 4 which is the same as the formula

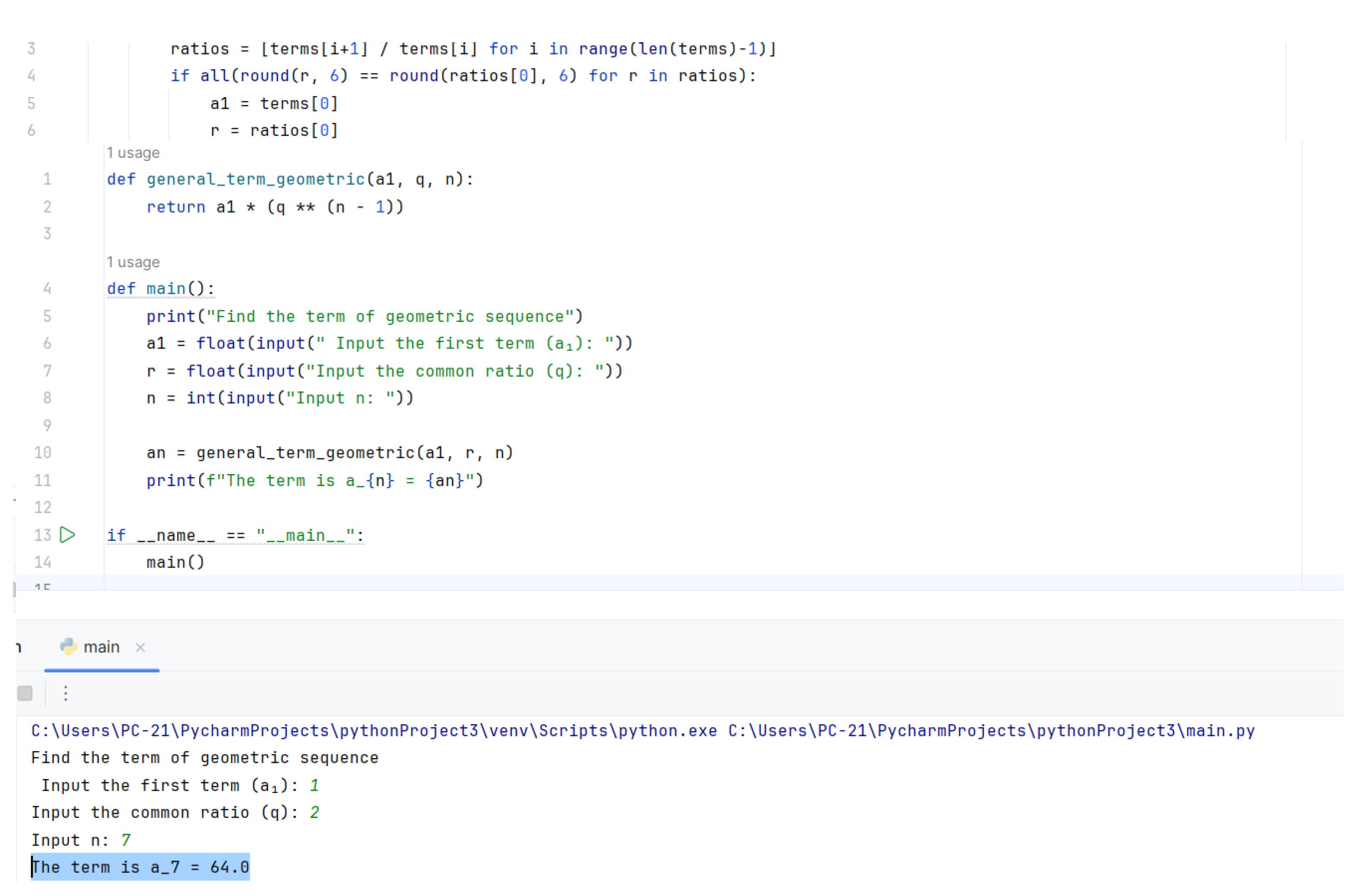

In the third requirement of the task, we need to find: How many books are arranged on the 7th shelf. Since we previously found the general term, we have:

For the result is

So, 64 books are arranged on the 7th shelf.

We prove this using Python, where the code is created in such a way that it requires the first term of the geometric sequence, the ratio of any two consecutive terms of the sequence (q), and the term we want to find.

Figure 6.

Finding the 7th term of geometric sequence.

Figure 6.

Finding the 7th term of geometric sequence.

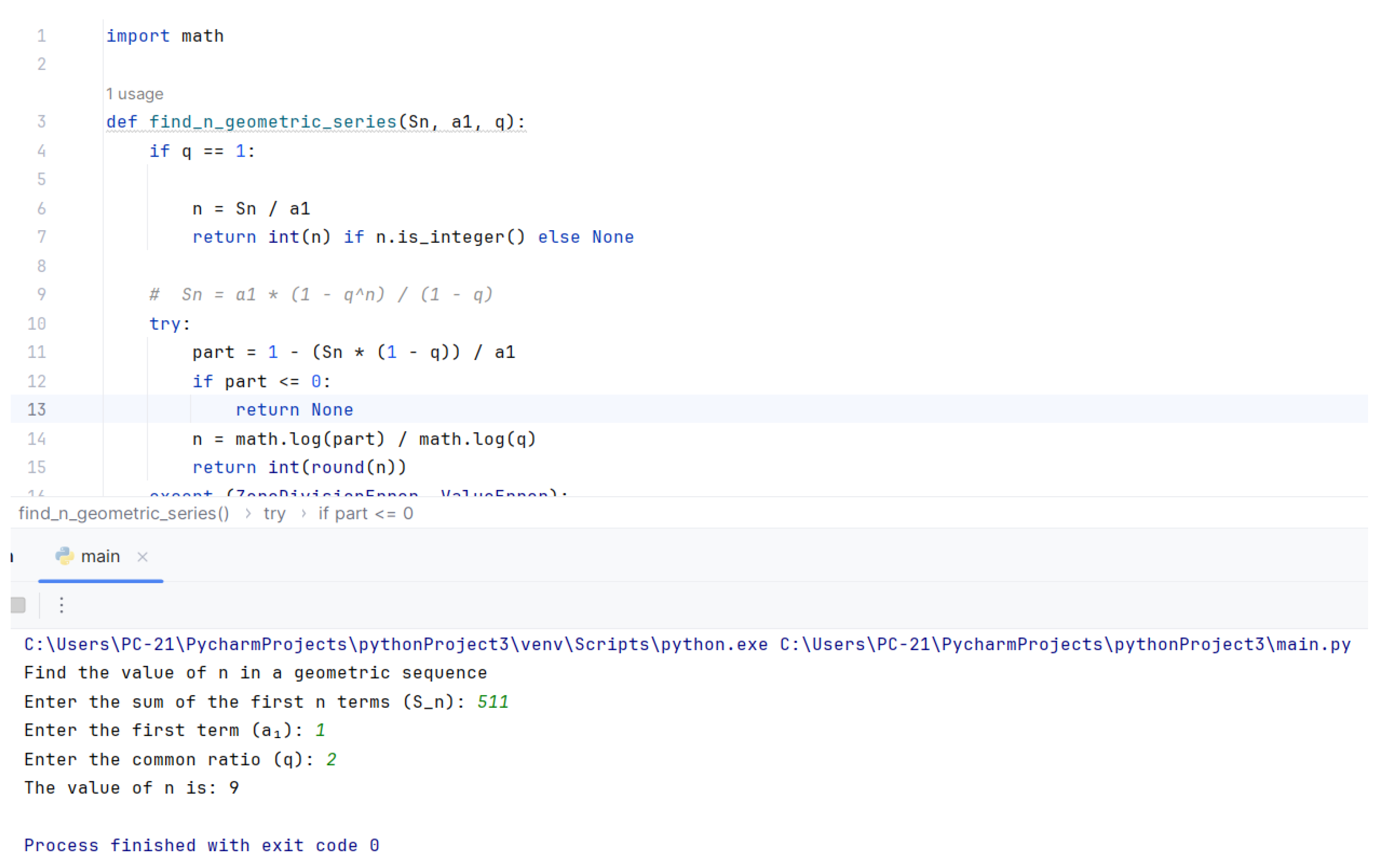

The final requirement of the assignment is: How many shelves should this bookstore have so that at least 511 books can be arranged?

Since the sum of the first n terms of the geometric series is: consequently the result is .

To prove this, we are using Python, where we can see that 9 shelves are needed to organize 511 books.

Figure 7.

Finding value of n by Python programming.

Figure 7.

Finding value of n by Python programming.

Reflection on problem solving: In this task, the choice was carried out in a structured manner by following several such steps. Initially, the identification of the main concept was made, where it was understood that we have made a geometric sequence, since the ratio between each successive term is constant, which is a basic external characteristic. Then, the strategy and process of solving the problem were determined, where the rule of forming the sequence was presented through a table and the terms obtained according to the rule were noted. This helped in the visualization of the sequence and in the understanding of its structure.

Also, the properties of the series were analyzed, such as: the series is geometric, it is an increasing and not decreasing series, it is an unbounded series (its terms increase infinitely).

To further deepen the understanding, the general term of the geometric sequence was also calculated using the formula for the general term

. In addition, to verify the accuracy of the results and strengthen their meaning, the Python programming language was also used, which served as a technological tool for checking the results.

Experimental group

Example 3: Modeling plant growth in a garden design

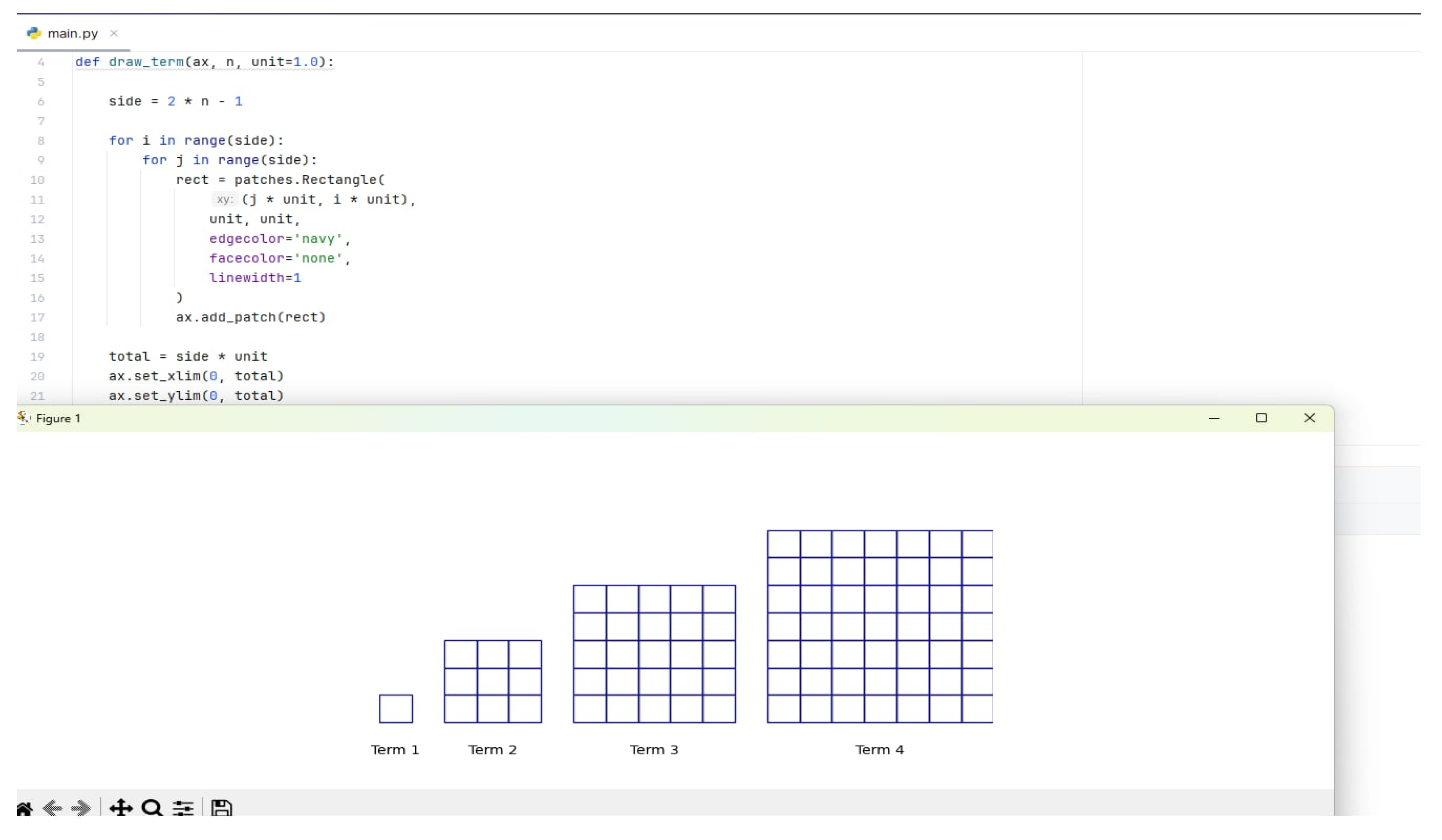

In this task, students were asked to simulate the growth pattern of a garden where the number of flower beds grows in a non-linear, non-repetitive way. The garden was designed in square layers: at each stage, a new square border is added around the previous garden, forming a concentric square pattern. Students had to calculate the total number of flower beds after each stage. |

Contextual setup

Stage 1: A single square flower bed (1 bed).

Stage 2: A 3x3 square, with 8 additional flower beds around the initial one (1 + 8 = 9 beds).

Stage 3: A 5x5 square, adding 16 more beds to the previous total (9 + 16 = 25 beds).

Stage 4: A 7x7 square, adding 24 more beds (25 + 24 = 49 beds).

Stage 5: A 9x9 square, adding 32 more beds (49 + 32 = 81 beds).

Numerical sequence: 1, 9, 25, 49, 81, ...

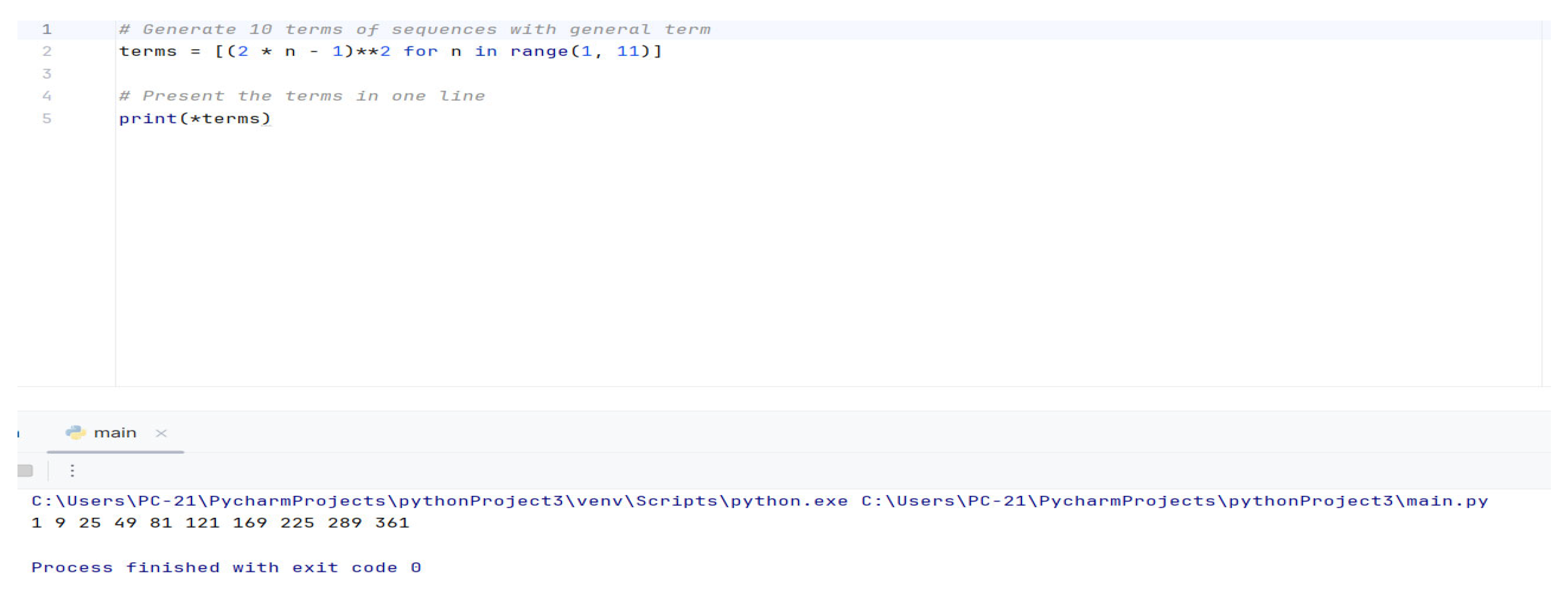

This sequence does not have a constant difference (not arithmetic) and does not involve a fixed ratio (not geometric). However, students discovered that each term corresponds to the square of an odd number:

Thus, the general term becomes:

Tasks for students:

Represent the garden visually using grid paper or simulation in Python.

Find the total number of flower beds for the first five stages.

Derive the general term for the sequence.

Use Python to verify the values for higher terms (e.g., Stage 10, Stage 15).

Identifying mathematical concepts in the task:

Students recognized that while this sequence does not follow a simple additive or multiplicative rule, it does have a predictable pattern based on odd-number squaring.

Using Python, they generated a table of values and visualizations showing the square structure growing layer by layer.

Figure 8.

Visualization the square structure growing by Python programming.

Figure 8.

Visualization the square structure growing by Python programming.

And finding multiple terms of a numerical sequence by Python programming

Figure 9.

Finding multiple terms of a numerical sequence with Python programming.

Figure 9.

Finding multiple terms of a numerical sequence with Python programming.

This example challenged students to look beyond typical arithmetic/geometric frameworks and encouraged pattern recognition and symbolic reasoning skills emphasized in problem-based and exploratory mathematics education [

28].

Through this activity, students learned to:

Translate a real-life situation into a mathematical model.

Use Python to experiment and validate conjectures.

Recognize and describe the pattern as

Apply this general formula to calculate higher-order terms such as:

Didactical note: This coding activity reinforced conceptual understanding and empowered students to independently verify mathematical patterns. It illustrates a constructivist approach to teaching sequences, consistent with the recommendations of NCTM [

29] and OECD [

27] on technology-supported, student - centred learning.

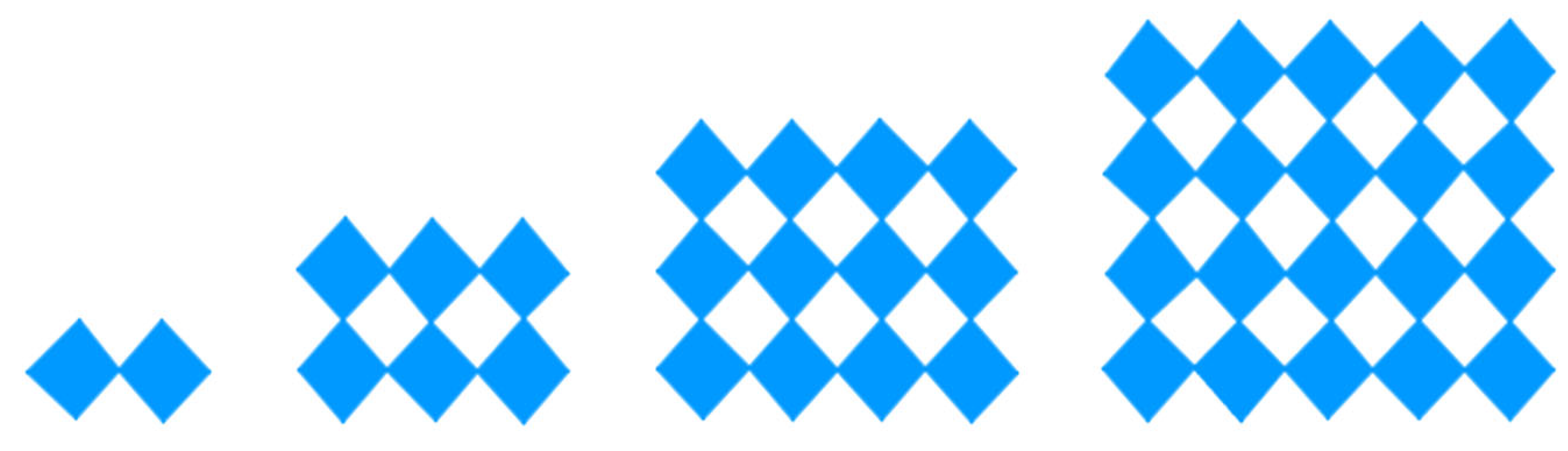

Experimental group

Case 4 exmaple: The pattern given in the figure below represents a numerical sequence, where the first term contains two squares, the second term contains 6 squares or 4 more than the first, the third term contains 6 more than the second term, and so on.. |

Figure 10.

Numerical sequence given in visual form.

Figure 10.

Numerical sequence given in visual form.

Sequence: 2, 6, 12, 20, ...

Student Tasks:

Calculate the number of squares in the first five steps?

Find the general term?

How many squares will there be in the 19th term based on the given rule??

Find the number of squares in the first 15th term?

Strategy and solution:

We form the table with the task data:

Table 4.

Representation of the rule and the value of the terms in numerical sequence.

Table 4.

Representation of the rule and the value of the terms in numerical sequence.

| Term |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Number of rows |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Number of columns |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| Value |

2 |

6 |

12 |

20 |

30 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

So they calculated the sum of the first five terms as:

where

is the sum of the first 5 terms of the sequence.

Explanation of the solution to the problem:

The sequence was identified as increasing, non-arithmetic, non-geometric, and unbounded.

As can be seen in the table above, the number of rows when multiplied by the number of columns gives us the value of the required term, so students can use this to find the general term.:

To prove the general term, we used Python programming and derive the closed-form formula.

Figure 11.

Generation by Python programming the general term.

Figure 11.

Generation by Python programming the general term.

By Python programming, we have found the general term

We can prove the terms by the general term that we found:

In the third requirement of the task, we need to find: How many squares will there be in the 19th term based on the given rule?

Since we have previously found the general term, then we have:

Reflection on problem solving:

During this task, several key results were observed:

Students were more motivated to participate in problem solving when it was context-based and visually presented.

The graphical and tabular presentation of the problem and the verification of the formula by programming facilitated a deeper understanding of the properties of the numerical sequence.

Students were able to explain their reasoning processes and describe the transition from concrete models to generalization.

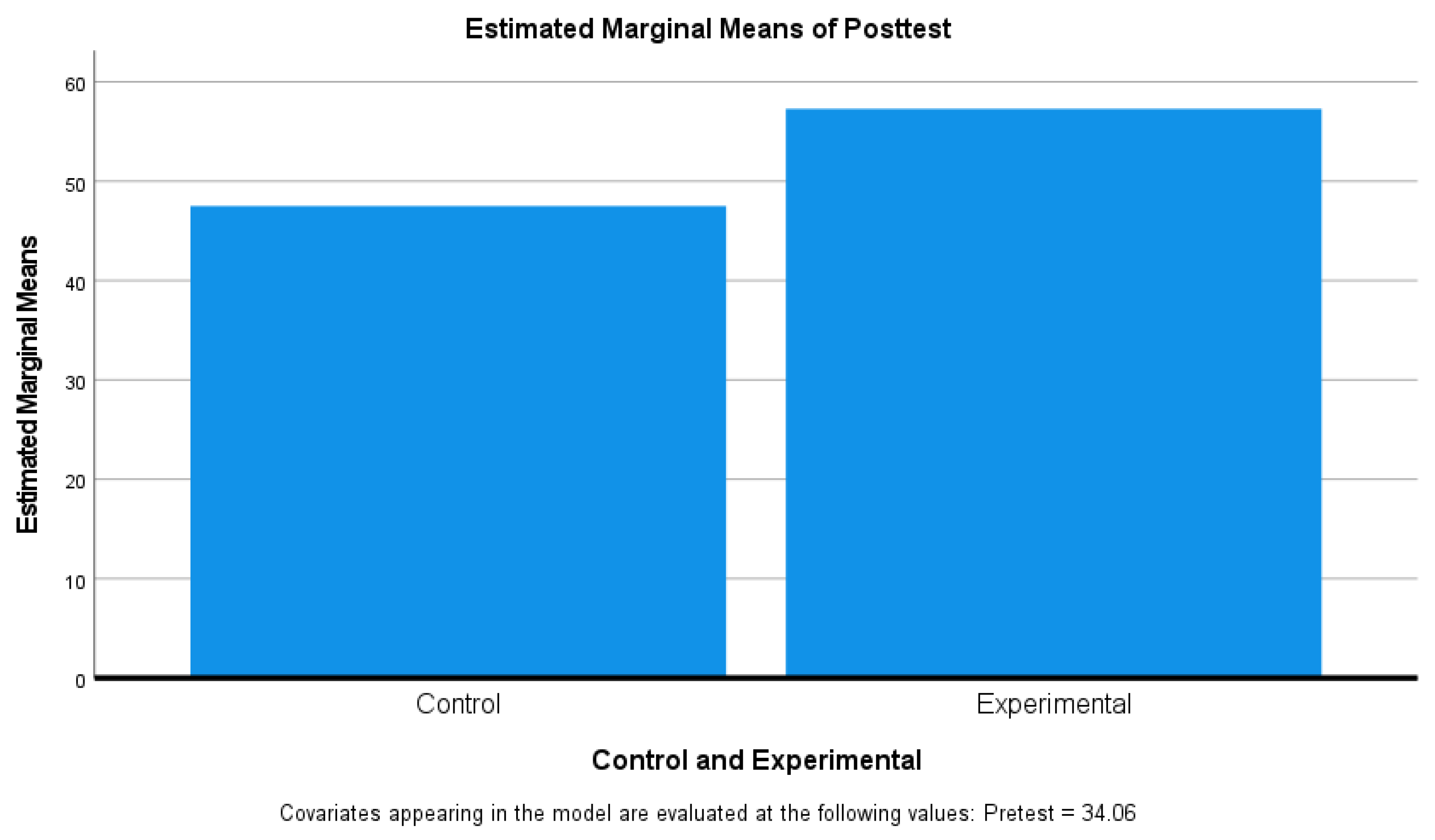

3.4. Analysis of Open-Ended Questionnaire Responses

In addition to quantitative results from pre-tests, post-tests, and classroom observations, the study incorporated a qualitative analysis of students’ reflections through four open-ended questions. These responses provided valuable insight into students’ attitudes, levels of engagement, and perceptions regarding the use of real-life contexts, visualization, programming, and AI tools during the learning process.

Key finding from student feedback

Many students stated that activities connected to everyday situations made mathematical content easier to understand. They reported that contextualized tasks helped them relate new concepts to familiar experiences, making lessons more meaningful and increasing their interest in numerical sequences.

Learners consistently emphasized that diagrams, shapes, and graphical representations allowed them to recognize patterns more easily. Visual elements helped them stay focused and better understand how a sequence grows or changes.

A large number of students expressed that working with Python made learning more interactive. They appreciated being able to check their calculations, visualize patterns instantly, and understand the structure of sequences through code. Many noted increased curiosity toward programming beyond the mathematics lesson.

Students from the experimental group highlighted that AI tools were especially helpful during the post-test. They felt that AI-supported code generation allowed them to visualize results more quickly, correct mistakes, and focus on reasoning instead of getting stuck on syntax. Several students reported greater confidence and satisfaction when solving tasks with the help of AI.

The following section highlights representative student comments gathered from the open-ended questionnaire items:

Question 1: What types of mathematical problems would you prefer to work on in class?

Student 1: “I like tasks that relate to real life, things like prices, planning, measurements, or anything that feels useful.”

Student 2: “Problems where we can use computers or coding are more enjoyable and make me want to learn more.”

Question 2: How do real-life contexts influence your understanding of numerical sequences?

Student 3: “They help me picture the situation, so I understand the pattern faster.”

Student 4: “I feel more motivated. These tasks make more sense compared to standard textbook examples.”

Question 3: How do visual representations affect your learning?

Student 5: “Drawings or graphs help me follow the sequence easily.”

Student 6: “When there is a visual model, I understand what to do almost immediately.”

Question 4: What is your opinion about using technology (Python and AI) while learning sequences?

Student 7: “Python and AI helped me check my answers and see the pattern clearly.”

Student 8: “It made the lesson more dynamic and made me want to learn Python better.”

The analysis of the open-ended questionnaire shows that integrating real-world situations, visual modeling, Python programming, and AI support significantly improved students’ learning experiences. These tools not only strengthened conceptual understanding but also increased engagement, motivation, and self-confidence. Students perceived lessons as more meaningful, interactive, and enjoyable.

From the instructional perspective, this approach effectively enhanced key mathematical competencies and aligned with modern educational practices. The positive reactions of students confirm that combining contextual learning with technological tools offers a promising direction for future mathematics teaching.