1. Introduction

Mathematics plays a pivotal role in everyday life and is taught across all educational levels—from elementary school through higher education [

46,

47]. According to the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture Regulation No. 64 of 2013, students are expected to develop the ability to communicate mathematical ideas using symbols, tables, diagrams, or other media to clarify situations or problems [

48,

49]. This underscores mathematical communication as a core competency that students must acquire [

50,

51]. However, empirical evidence consistently reveals that students’ mathematical communication skills remain suboptimal. For instance, [

52,

53] found that eighth-grade students at SMP Negeri 2 Padangsidmpuangenerally performed poorly in data representation tasks, failing to meet most indicators of mathematical communication. Similarly, [

54,

55] reported that students often struggle to fully comprehend problem statements, encounter difficulties during problem-solving processes, and misuse mathematical symbols—highlighting an urgent need for pedagogical interventions to enhance this skill. [

56]

Mathematics serves as a fundamental tool in understanding and interpreting phenomena in everyday life, underpinning activities from simple counting and budgeting to complex problem-solving in science, technology, and engineering [

57,

58]. Its relevance extends beyond practical applications; mathematics cultivates logical reasoning, critical thinking, and systematic analysis that are essential for personal and professional development. In educational contexts, mathematics instruction is structured to progressively develop these competencies across all levels, from basic numeracy in elementary school to abstract reasoning in tertiary education. The Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture emphasizes that students should not only acquire computational skills but also the ability to convey mathematical ideas effectively through various forms of representation, including symbols, diagrams, tables, and other visual or textual media [

59,

60]. Effective communication of mathematical concepts is increasingly recognized as a critical competency that facilitates understanding, collaboration, and application of knowledge across disciplines. Despite this emphasis, students frequently exhibit deficiencies in expressing mathematical ideas clearly, indicating a gap between curricular goals and learning outcomes. Addressing this gap is central to enhancing both academic performance and broader problem-solving capabilities in students. [

57,

58,

59,

60]

Empirical studies consistently highlight challenges in students’ mathematical communication, revealing persistent weaknesses in articulating, representing, and reasoning with mathematical information. For instance, research by [

1,

2] demonstrated that eighth-grade students at SMP Negeri 2 Padangsidmpuanunderperformed in tasks requiring data representation, often failing to meet standard indicators of mathematical communication. Such deficiencies are not limited to specific grade levels or tasks but appear as a recurring issue across various mathematical domains, from algebraic expressions to geometric reasoning. The observed difficulties suggest that traditional instructional methods may inadequately support students in developing expressive and representational skills in mathematics. Furthermore, students’ inability to communicate mathematically hinders their capacity to internalize concepts, apply problem-solving strategies, and engage in higher-order thinking. This highlights the necessity for pedagogical interventions that foster active engagement, critical analysis, and collaborative learning, thereby promoting both conceptual understanding and communicative proficiency. Without targeted strategies, students risk developing fragmented knowledge that limits their ability to transfer mathematical skills to novel situations, which is increasingly critical in the 21st-century knowledge economy. [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]

Mathematical communication encompasses a broad set of competencies, including the ability to explain reasoning, justify solutions, interpret visual data, and construct coherent arguments using appropriate mathematical language. These competencies are foundational for problem-solving, as they enable learners to navigate complex situations with clarity and precision. [

4,

5] assert that developing such skills enhances students’ analytical capacity and fosters a deeper understanding of mathematical structures. When students can articulate their thought processes and present logical explanations, they are better equipped to detect errors, reflect critically, and adapt strategies during problem-solving. However, research indicates that many learners struggle with translating abstract mathematical ideas into understandable forms, often due to limited exposure to tasks that require explanation or reasoning beyond procedural computation. The development of mathematical communication thus requires intentional instructional design that integrates opportunities for discussion, reasoning, and representation across multiple contexts. Educators must scaffold learning experiences that challenge students to synthesize, evaluate, and communicate mathematical information effectively. Such practices contribute not only to academic success but also to lifelong skills in reasoning and decision-making. [

6,

7]

The role of visualization tools and digital technologies in enhancing mathematical communication has gained considerable attention in recent literature. GeoGebra, dynamic geometry software, and other digital platforms provide interactive environments where students can experiment with mathematical concepts, construct representations, and test hypotheses visually [

8,

9]. By integrating these technologies into teaching, learners can bridge the gap between abstract concepts and tangible understanding, thereby improving their ability to communicate ideas effectively. These tools support multimodal representation, allowing students to express reasoning through graphs, diagrams, simulations, and symbolic notation. Moreover, technology-enabled collaboration encourages peer discussion, feedback, and negotiation of mathematical meaning, further reinforcing communicative competence. The inclusion of digital platforms aligns with contemporary pedagogical shifts emphasizing active, inquiry-based, and student-centered learning approaches. Nevertheless, the efficacy of such interventions depends on careful instructional planning, teacher proficiency with the tools, and alignment with curricular objectives that prioritize both conceptual understanding and communicative skills. [

10,

11]

Pedagogical strategies such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL) have demonstrated potential in promoting mathematical communication by situating learning within authentic, complex problems. PBL encourages students to articulate reasoning, engage in collaborative problem-solving, and justify solutions within a contextual framework. [

12,

13] observed that students often struggle with comprehension and symbol usage in traditional instructional models, but integrating PBL can mitigate these challenges by providing structured opportunities for discussion, representation, and reflection. In PBL environments, learners encounter real-world problems that necessitate explanation, analysis, and communication of solutions, fostering deeper engagement and understanding. The iterative nature of PBL allows students to refine their thinking, negotiate meaning with peers, and produce coherent representations of mathematical ideas. By emphasizing the process as much as the outcome, PBL supports the development of critical communicative skills alongside problem-solving proficiency. Such approaches highlight the importance of aligning instructional methods with desired competencies, ensuring that students acquire both knowledge and the ability to express it effectively. [

14,

15]

The integration of collaborative learning models also plays a critical role in enhancing mathematical communication. Group-based activities, peer instruction, and discussion forums create environments where students must articulate ideas, question assumptions, and negotiate shared understanding. These interactions not only expose learners to diverse perspectives but also require them to justify reasoning and present arguments coherently. Collaborative approaches encourage iterative feedback cycles, enabling learners to identify misconceptions, refine explanations, and develop more precise mathematical language. Additionally, social constructivist perspectives emphasize that knowledge is co-constructed through interaction, making communication an integral component of learning itself. In such settings, students gain confidence in expressing mathematical ideas and develop skills transferable to interdisciplinary problem-solving contexts. The combined effect of collaboration, discussion, and reflection contributes to both cognitive development and communicative competence, reinforcing the value of social interaction as a mechanism for deepening understanding in mathematics education. [

16,

17]

Addressing students’ mathematical communication deficiencies requires comprehensive teacher professional development, curriculum alignment, and assessment practices that emphasize both process and representation. Teachers must be equipped with pedagogical knowledge and technological competencies to facilitate instruction that promotes articulation, reasoning, and multimodal representation. Curriculum frameworks should explicitly integrate objectives related to communication, problem-solving, and conceptual understanding, ensuring coherence across grade levels. Assessment practices, in turn, should evaluate not only procedural accuracy but also the clarity, coherence, and sophistication of students’ explanations and representations. By aligning teaching, curriculum, and assessment, educational systems can create environments that foster the continuous development of mathematical communication. Enhancing this competency contributes not only to academic achievement but also to learners’ capacity for critical thinking, problem-solving, and lifelong learning, reinforcing mathematics as a central pillar of education and societal development. [

18,

19]

One promising instructional approach is Problem-Based Learning (PBL), which engages students in authentic, real-world problems as the foundation for learning [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Research by [

1,

2,

3,

4] demonstrated that PBL significantly improves mathematical communication compared to Direct Instruction (DI), with moderate gains observed in both groups and positive student attitudes toward PBL. Additionally, [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] confirmed that PBL-based learning materials are valid and practical for classroom implementation. To further enhance student engagement in PBL, integrating dynamic digital tools such as GeoGebra is essential. GeoGebra is a dynamic mathematics software that supports conceptual understanding and facilitates the construction of mathematical ideas [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Studies have shown its effectiveness: [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] reported significant improvements in student learning outcomes after GeoGebra integration, particularly in three-dimensional geometry, while [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] found a strong effect (97.7%) of GeoGebra Classic on students’ conceptual understanding of geometric transformations.

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) has emerged as an innovative instructional approach that prioritizes student-centered learning through engagement with authentic, real-world problems [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. This methodology shifts the focus from teacher-led explanations to active learner participation, encouraging students to explore, analyze, and construct solutions collaboratively. Research indicates that PBL not only enhances content knowledge but also develops higher-order cognitive skills, including critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] specifically demonstrated that students exposed to PBL exhibited significant improvements in mathematical communication compared to those receiving traditional Direct Instruction (DI), while both groups showed moderate learning gains. Moreover, students expressed positive attitudes toward PBL, indicating heightened motivation and engagement in mathematical tasks. These findings underscore the pedagogical value of situating learning within realistic, meaningful contexts that stimulate intellectual curiosity and active participation. [

16]

The effectiveness of PBL is closely linked to the design and validity of learning materials employed in the instructional process. [

17] confirmed that PBL-based learning resources are both valid and practical, enabling seamless integration into classroom activities. Well-designed materials provide structured guidance for problem exploration, scaffold students’ reasoning, and support iterative reflection. In the context of mathematics, such resources often include tasks that require students to represent problems visually, justify solutions, and communicate ideas effectively. This alignment of content, pedagogy, and assessment reinforces the core competencies of mathematical communication and conceptual understanding. Additionally, practical and validated materials reduce teacher workload while maintaining fidelity to the PBL framework, ensuring consistent and effective learning experiences across different classrooms and educational settings. [

18,

19,

20]

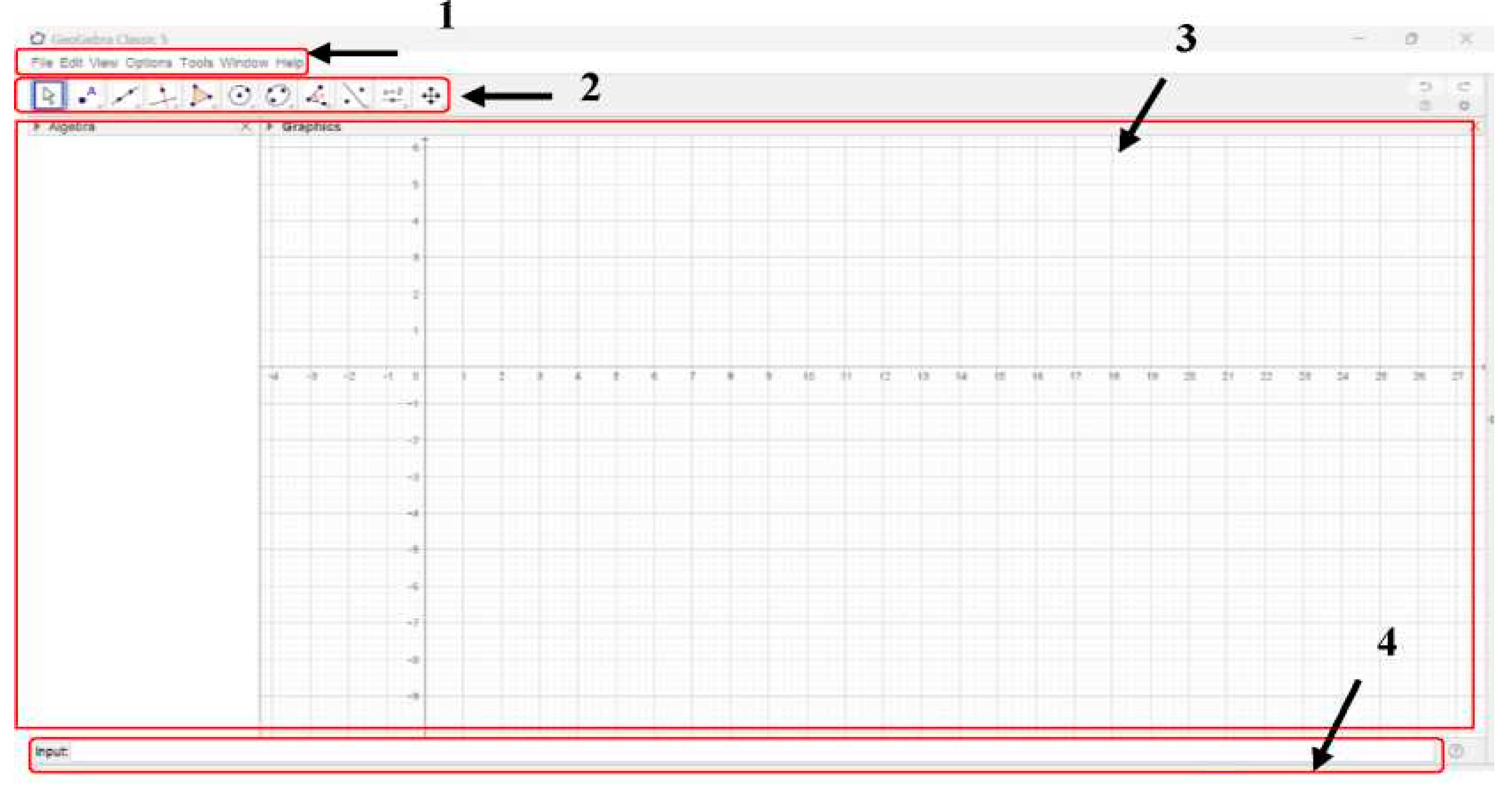

To maximize the benefits of PBL, integrating dynamic digital tools such as GeoGebra has proven to be highly effective in supporting mathematical understanding. GeoGebra, a versatile mathematics software, allows students to interact with geometric, algebraic, and statistical concepts dynamically, promoting visualization and active manipulation of mathematical objects [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This technology transforms abstract ideas into tangible, interactive representations, facilitating comprehension and enhancing engagement. By allowing learners to experiment with variables, observe patterns, and test conjectures, GeoGebra provides a platform where conceptual understanding is reinforced through discovery and exploration. Such integration complements the problem-solving focus of PBL, encouraging students to articulate reasoning, construct coherent arguments, and communicate solutions with precision and clarity. [

7]

Empirical studies highlight the tangible impact of GeoGebra on students’ mathematical performance and communication skills. [

8] reported that the incorporation of GeoGebra into classroom activities significantly improved student learning outcomes, particularly in three-dimensional geometry, where visualization and spatial reasoning are critical. The interactive environment enabled learners to manipulate geometric objects, observe transformations, and construct proofs, thereby deepening their conceptual understanding. Similarly, [

9] demonstrated a strong effect of 97.7% when using GeoGebra Classic to enhance students’ comprehension of geometric transformations. These findings suggest that dynamic visualization tools not only facilitate conceptual learning but also foster accurate and confident mathematical communication, bridging the gap between abstract theory and practical understanding. [

10]

The integration of GeoGebra within PBL fosters an enriched learning environment that emphasizes student autonomy and collaborative exploration. In such settings, learners actively participate in defining problems, hypothesizing solutions, and validating results through interactive representations. Peer collaboration further reinforces communication skills, as students must explain reasoning, justify approaches, and negotiate differing perspectives. This process cultivates both cognitive and social competencies, including logical argumentation, critical evaluation, and cooperative problem-solving. The synergy between PBL and GeoGebra enables a multi-modal approach to learning, combining hands-on experimentation, visual representation, and verbal explanation, which collectively strengthens students’ ability to communicate mathematical ideas effectively. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]

Moreover, the integration of digital tools into PBL aligns with contemporary educational priorities emphasizing 21st-century skills such as technological literacy, creativity, and adaptive problem-solving. By interacting with GeoGebra, students develop a deeper understanding of mathematical structures and acquire skills transferable to other STEM disciplines. The dynamic manipulation of mathematical objects encourages experimentation, hypothesis testing, and iterative refinement, fostering a mindset of inquiry and resilience in problem-solving. Teachers play a critical role in guiding this process, designing tasks that are both challenging and scaffolded to ensure students derive meaningful learning outcomes while developing proficiency in communication and reasoning. [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]

Combining PBL with GeoGebra has implications for curriculum design, teacher professional development, and assessment practices in mathematics education. Curriculum frameworks should integrate opportunities for problem-based and technology-enhanced learning, explicitly targeting communication, conceptual understanding, and application. Teachers require professional development to effectively implement PBL and leverage GeoGebra’s functionalities, ensuring alignment between pedagogy, content, and technology. Assessment practices must also evolve to evaluate not only procedural accuracy but also students’ ability to represent, explain, and communicate mathematical ideas coherently. By creating such an integrated instructional ecosystem, educational institutions can enhance both learning outcomes and student engagement, fostering the development of mathematically proficient learners capable of applying knowledge creatively and effectively in real-world contexts. [

1,

2,

3,

4]

In contrast, Discovery Learning (DL)—another constructivist model widely used in Grade VIII mathematics classrooms, such as at SMP Negeri 1 Padangsidmpuan—also promotes active knowledge construction under teacher guidance [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Evidence suggests DL outperforms conventional methods in enhancing mathematical communication [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] confirming measurable improvements post-intervention. Nevertheless, the ultimate benchmark for instructional success remains whether students achieve the Minimum Completeness Criterion (KKM), a school-specific threshold aligned with competency-based curriculum standards [

16].

Discovery Learning (DL) represents another constructivist instructional paradigm that emphasizes student-centered exploration and active engagement in knowledge construction under guided facilitation by the teacher [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Rooted in the theories of Bruner and other constructivist scholars, DL positions learners as active agents in discovering principles, patterns, and relationships through inquiry-based activities rather than passive recipients of information. In mathematics education, this approach is particularly relevant for fostering deeper conceptual understanding and problem-solving competence, as students are encouraged to investigate, hypothesize, test, and reflect throughout the learning process. DL has been widely implemented in Indonesian junior high schools, including at SMP Negeri 1 Padangsidimpuan, where it serves as a pedagogical strategy to promote inquiry, reasoning, and independent thought. Within this model, the teacher functions as a facilitator who scaffolds students’ discovery by posing probing questions, providing feedback, and ensuring conceptual coherence, thereby cultivating both autonomy and accountability in learning. [

21,

22,

23,

24]

Empirical research supports the efficacy of Discovery Learning in improving key mathematical competencies, including communication, reasoning, and critical thinking. [

25,

26,

27] demonstrated that DL significantly outperformed conventional instructional methods in enhancing students’ mathematical communication abilities. Their findings revealed that students in DL-based classrooms displayed higher proficiency in articulating mathematical ideas, representing relationships symbolically, and justifying problem-solving steps. This improvement can be attributed to DL’s emphasis on exploration and reflection, which requires students to verbalize reasoning and translate abstract concepts into comprehensible forms. Moreover, the interactive and dialogical nature of DL nurtures metacognitive awareness, enabling learners to monitor their understanding and adjust strategies as needed. Such processes not only reinforce comprehension but also strengthen students’ confidence and fluency in communicating mathematical ideas effectively. [

28,

29,

30]

Further empirical validation of Discovery Learning’s effectiveness was provided by [

16,

17,

18,

19], who reported measurable improvements in students’ mathematical communication following the implementation of DL-based instruction. Their study revealed that the model enhances not only students’ ability to explain reasoning but also their accuracy in representing mathematical relationships through diagrams, equations, and graphs. These outcomes suggest that the iterative discovery process inherent in DL stimulates both analytical and expressive dimensions of mathematical competence. Through structured exploration and guided reflection, students gradually develop the capacity to articulate conceptual insights, connect prior knowledge to new information, and generalize mathematical principles across contexts. Such findings underscore the robustness of DL as a pedagogical approach capable of fostering deep and transferable learning in mathematics education. [

20]

Despite its demonstrated advantages, the success of Discovery Learning must ultimately be measured by students’ achievement of the Minimum Completeness Criterion (Kriteria Ketuntasan Minimal, KKM), a benchmark established by individual schools to evaluate learning outcomes [

21]. The KKM serves as a tangible indicator of whether students have mastered the essential competencies prescribed by the national curriculum, reflecting not only their knowledge acquisition but also their ability to apply it effectively. In the context of DL, achieving the KKM indicates that students have successfully internalized mathematical concepts through discovery and can demonstrate proficiency in both understanding and communication. However, variations in KKM standards across schools introduce contextual differences that must be considered when assessing instructional effectiveness. Factors such as teacher expertise, resource availability, and student readiness also influence the extent to which DL can facilitate mastery learning. [

22]

From an instructional perspective, aligning Discovery Learning with KKM targets requires careful planning and systematic implementation. Teachers must design discovery tasks that are both challenging and attainable, ensuring alignment with competency-based curriculum objectives. Scaffolding strategies—such as guiding questions, collaborative discussion, and incremental feedback—play a critical role in supporting students throughout the discovery process. Furthermore, assessment practices should capture both the process and product of learning, evaluating how students reason, represent, and communicate mathematical ideas rather than focusing solely on final answers. This holistic assessment approach ensures that the cognitive and communicative dimensions of mathematical learning are equally valued, providing a more accurate reflection of students’ competency development within the DL framework. [

23]

Incorporating Discovery Learning effectively also demands robust teacher professional development and reflective practice. Teachers must possess not only a deep understanding of mathematical content but also the pedagogical skills to guide inquiry and manage diverse learning trajectories within the classroom. Professional learning communities and peer collaboration can enhance teachers’ capacity to design discovery-oriented lessons that balance autonomy with structured guidance. Moreover, integrating technological tools such as GeoGebra within DL contexts can further enhance exploration and visualization, bridging the gap between abstract reasoning and tangible understanding. Such integrations amplify students’ engagement and communication, reinforcing DL’s constructivist foundation through multimodal learning experiences. [

24]

While Discovery Learning demonstrates strong potential in enhancing mathematical communication and meeting curriculum benchmarks, its effectiveness depends on sustained institutional support, adequate resources, and alignment with broader educational goals. Schools must foster a culture that values inquiry, creativity, and reflective learning, supported by policies that encourage pedagogical innovation. Continuous monitoring and evaluation are essential to ensure that DL implementation yields measurable improvements in student performance relative to KKM standards. By embedding Discovery Learning within a comprehensive instructional ecosystem that includes supportive assessment, teacher training, and technological integration, educators can optimize its potential to develop mathematically literate, communicative, and adaptive learners prepared to navigate complex challenges in both academic and real-world contexts. [

25,

26]

To gauge student perceptions, post-instruction questionnaires are commonly employed as research instruments [

27,

28]. As defined by Walgito [

29], such questionnaires assess students’ reception, comprehension, and evaluation of the learning experience.

To gauge students’ perceptions of instructional interventions, post-instruction questionnaires are widely utilized as a systematic means of data collection in educational research [

30]. These instruments provide valuable insights into how students experience, interpret, and respond to various teaching methods and learning environments. In the context of mathematics education, perception questionnaires play a critical role in capturing affective dimensions of learning, such as interest, motivation, engagement, and perceived relevance of instructional approaches. They complement cognitive assessments by offering a more holistic understanding of learning effectiveness from the students’ perspective. Through structured items and Likert-scale responses, questionnaires enable researchers to quantify subjective experiences, identify patterns of satisfaction or difficulty, and evaluate the overall pedagogical impact of a given intervention. [

16]

According to Walgito, as cited in [

17], questionnaires serve to assess three key dimensions of perception: reception, comprehension, and evaluation. Reception refers to the initial awareness and attention students direct toward the learning experience, determining whether the instructional stimuli effectively capture their focus and curiosity. Comprehension involves students’ interpretation and internalization of instructional content, indicating how well they understand the material and perceive its coherence. Evaluation, in turn, encompasses students’ judgment of the learning process, including its relevance, usefulness, and overall satisfaction. By addressing these dimensions, perception questionnaires provide a nuanced understanding of how instructional models—such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL), Discovery Learning (DL), or technology-enhanced strategies—affect learners’ cognitive and emotional engagement. [

18]

The implementation of perception questionnaires offers several methodological advantages for educational research. They allow for the efficient collection of data from large groups, ensuring broad representativeness and statistical reliability. Additionally, the use of standardized items facilitates comparative analysis across instructional conditions or demographic groups. When designed carefully, perception instruments can capture both general attitudes toward mathematics and specific responses to teaching strategies, technological tools, or assessment practices. Researchers often supplement quantitative data with qualitative responses, such as open-ended questions, to capture deeper insights into students’ experiences and suggestions for improvement. This mixed-method approach enriches the interpretation of findings and strengthens the validity of conclusions drawn about instructional effectiveness. [

19]

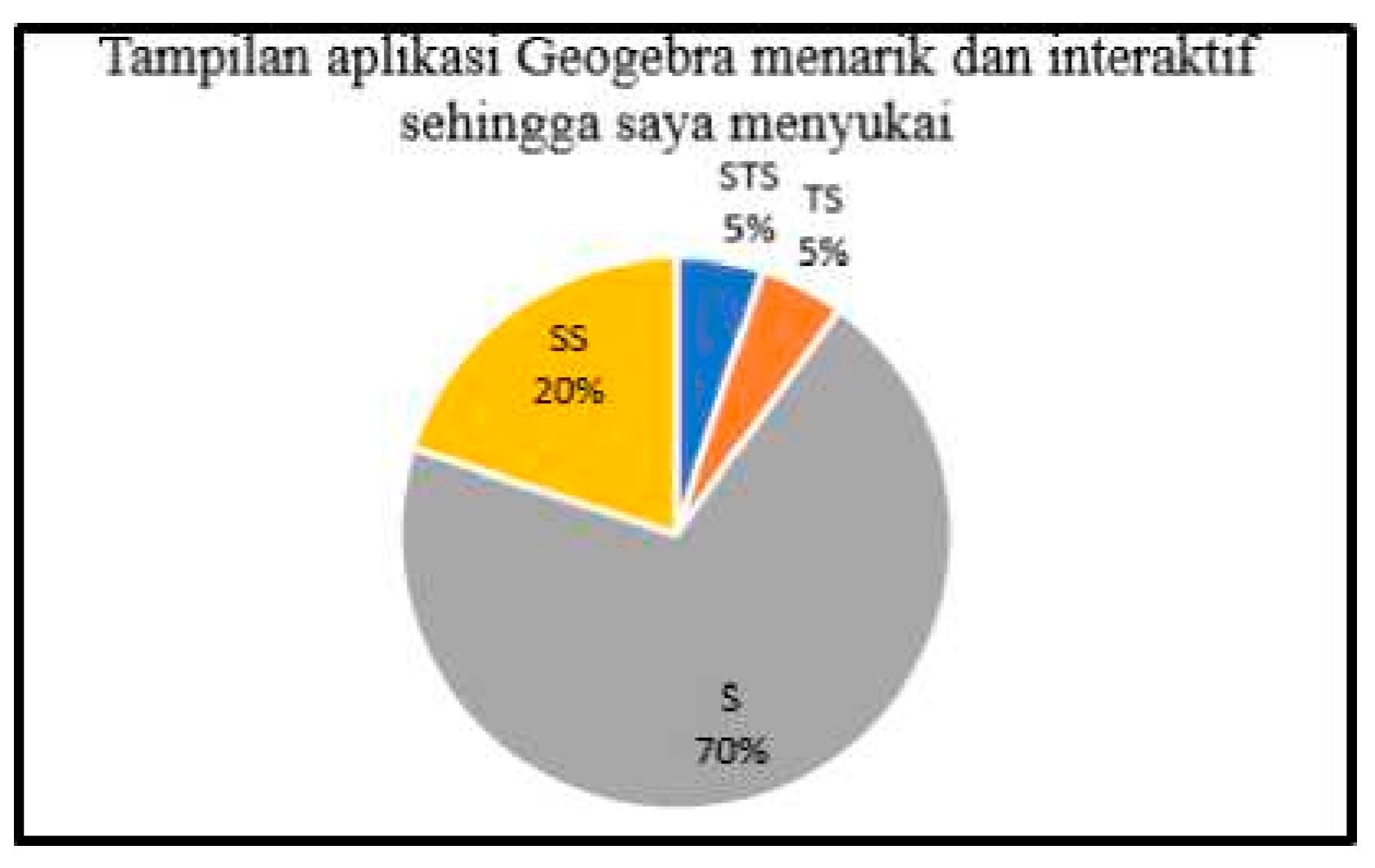

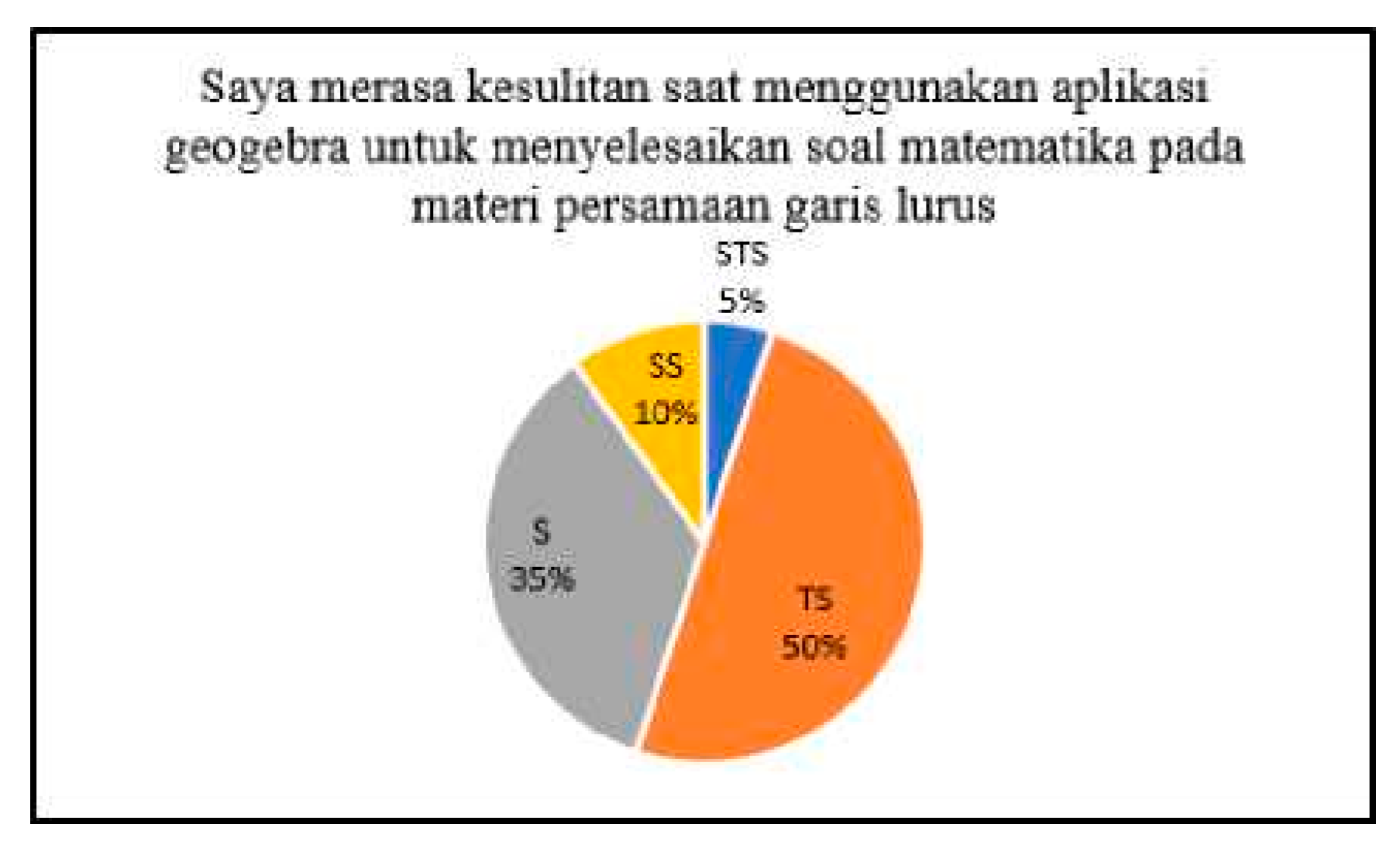

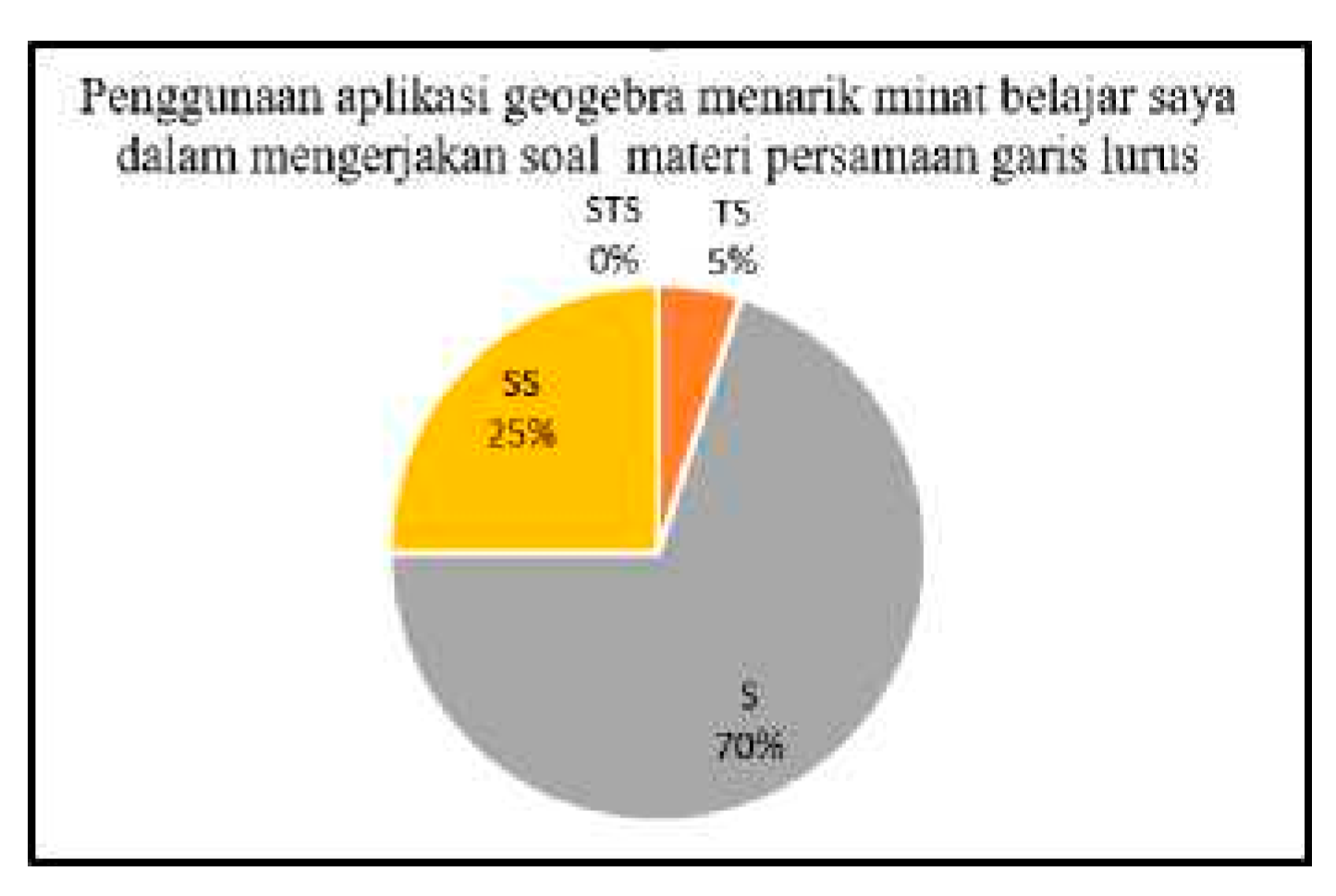

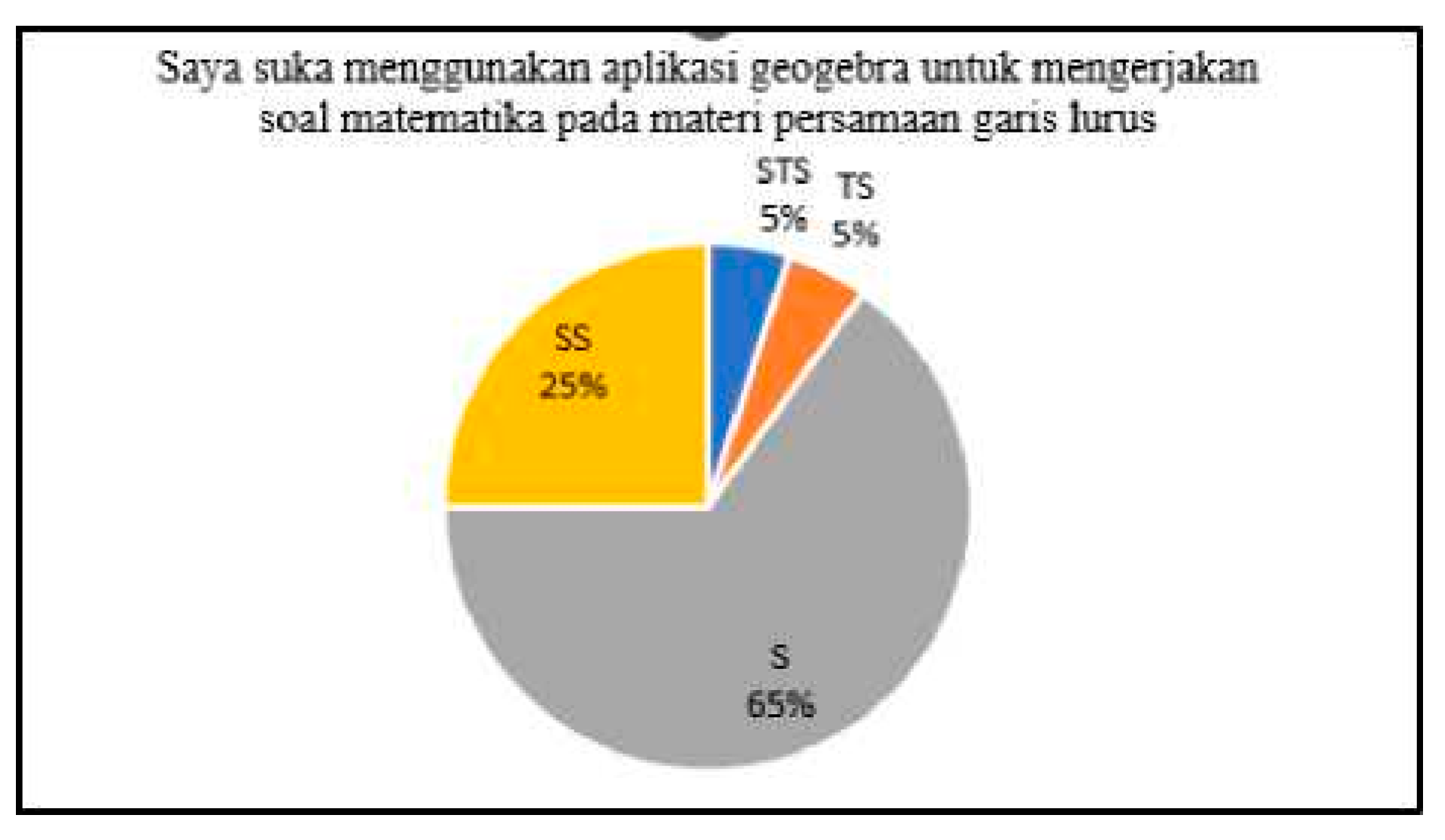

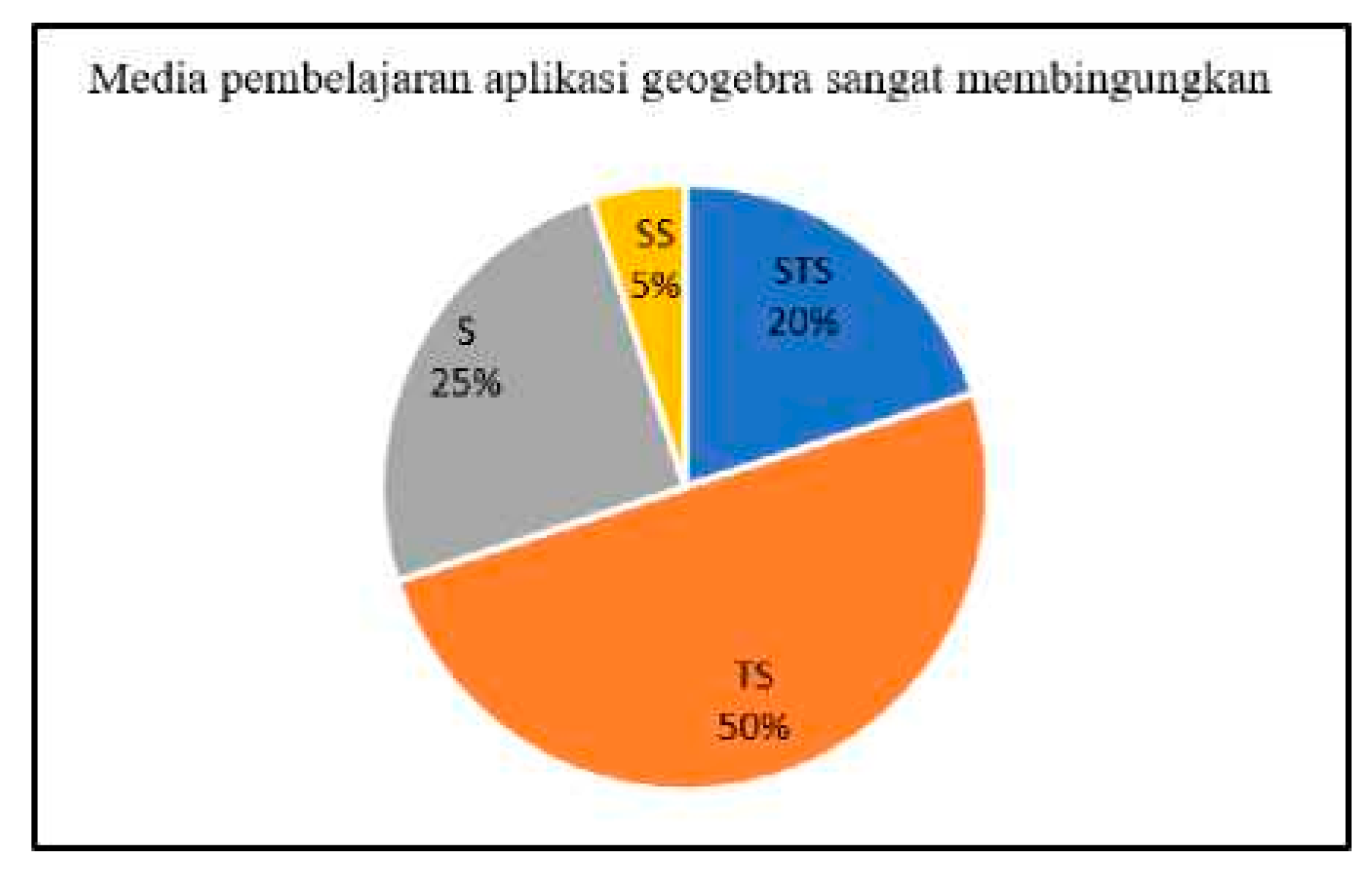

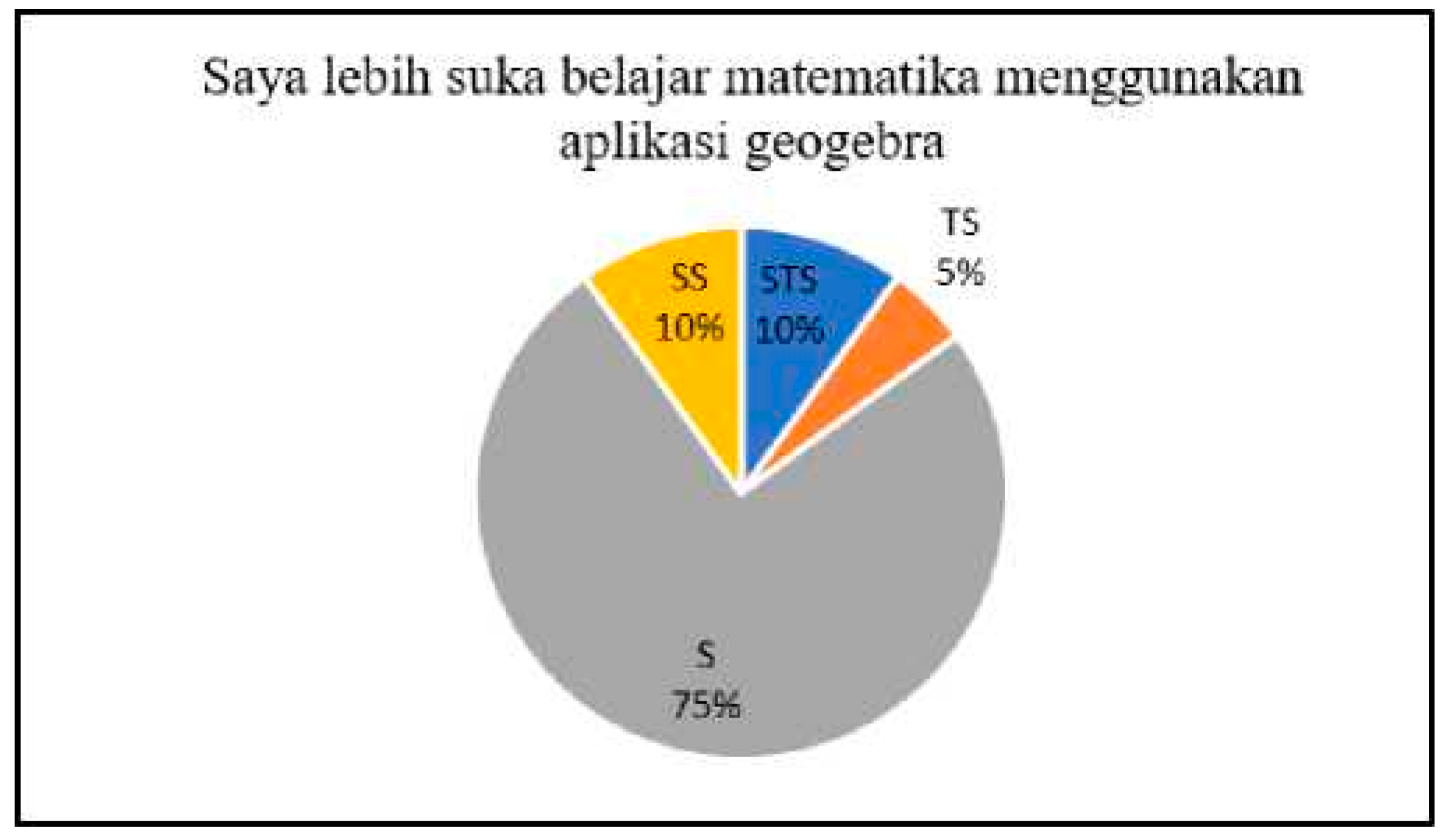

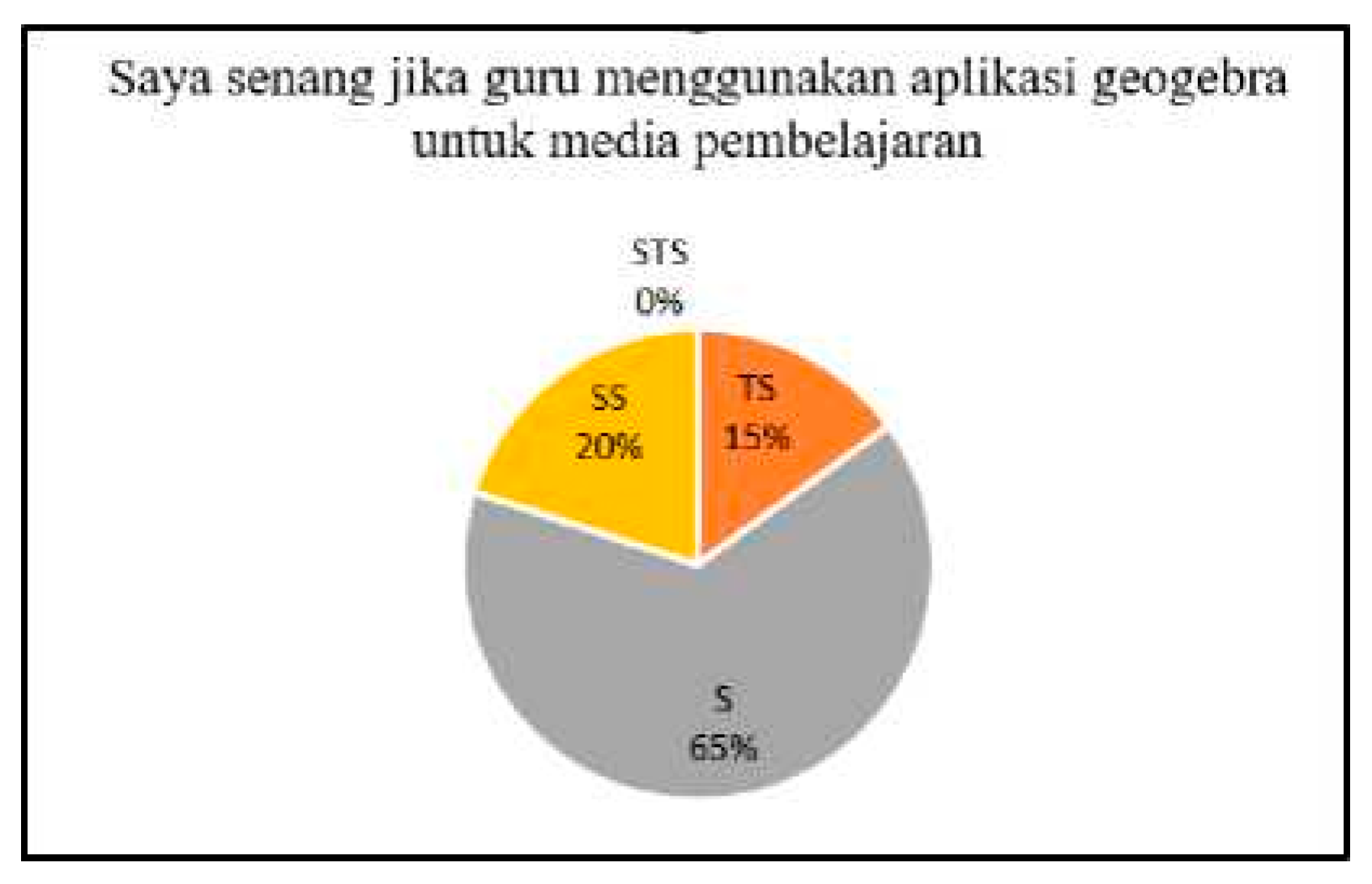

In mathematics education, analyzing student perceptions through post-instruction questionnaires provides actionable feedback for educators and curriculum developers. Positive perceptions often correlate with increased motivation, deeper engagement, and higher learning outcomes, while negative perceptions may signal misalignment between instructional design and learner needs. For example, when students report high levels of satisfaction and perceived relevance in technology-integrated settings, such as those involving GeoGebra or digital learning platforms, it suggests that these innovations successfully enhance both understanding and enjoyment. Conversely, reports of difficulty or disengagement highlight areas where instructional adjustments are necessary. Thus, perception analysis not only measures affective responses but also serves as a diagnostic tool for continuous pedagogical improvement. [

20]

The reliability and validity of perception questionnaires are crucial for ensuring meaningful and trustworthy results. Researchers must carefully construct questionnaire items to avoid ambiguity, bias, or redundancy while ensuring alignment with the study’s objectives and theoretical framework. Pilot testing is often conducted to refine items, assess internal consistency, and confirm construct validity. Furthermore, statistical analyses such as Cronbach’s alpha are used to verify the reliability of scales measuring student attitudes or perceptions. By adhering to these methodological standards, researchers can confidently interpret questionnaire data as an accurate reflection of students’ learning experiences and perceptions of instructional quality. [

21]

Beyond their research utility, perception questionnaires contribute to reflective teaching practices by providing direct feedback from students. When educators systematically analyze student perceptions, they gain insights into how learners interpret teaching strategies, materials, and classroom interactions. Such feedback fosters adaptive teaching, where instructors refine pedagogical techniques based on empirical evidence of student engagement and satisfaction. In the broader context of education reform, perception studies can inform policy decisions related to curriculum innovation, technology integration, and teacher professional development. By incorporating student voices into the evaluation process, educational systems promote inclusivity and responsiveness to learner diversity. [

22]

The use of post-instruction questionnaires as perception assessment tools bridges the gap between instructional design and learner experience. They provide an evidence-based framework for understanding how students receive, process, and evaluate mathematical instruction, thereby contributing to the ongoing enhancement of educational quality. In an era where student-centered learning is increasingly prioritized, capturing learner perceptions becomes indispensable for ensuring that pedagogical innovations—whether constructivist models like PBL and DL or technology-supported interventions—are not only cognitively effective but also positively experienced by students. [

23]

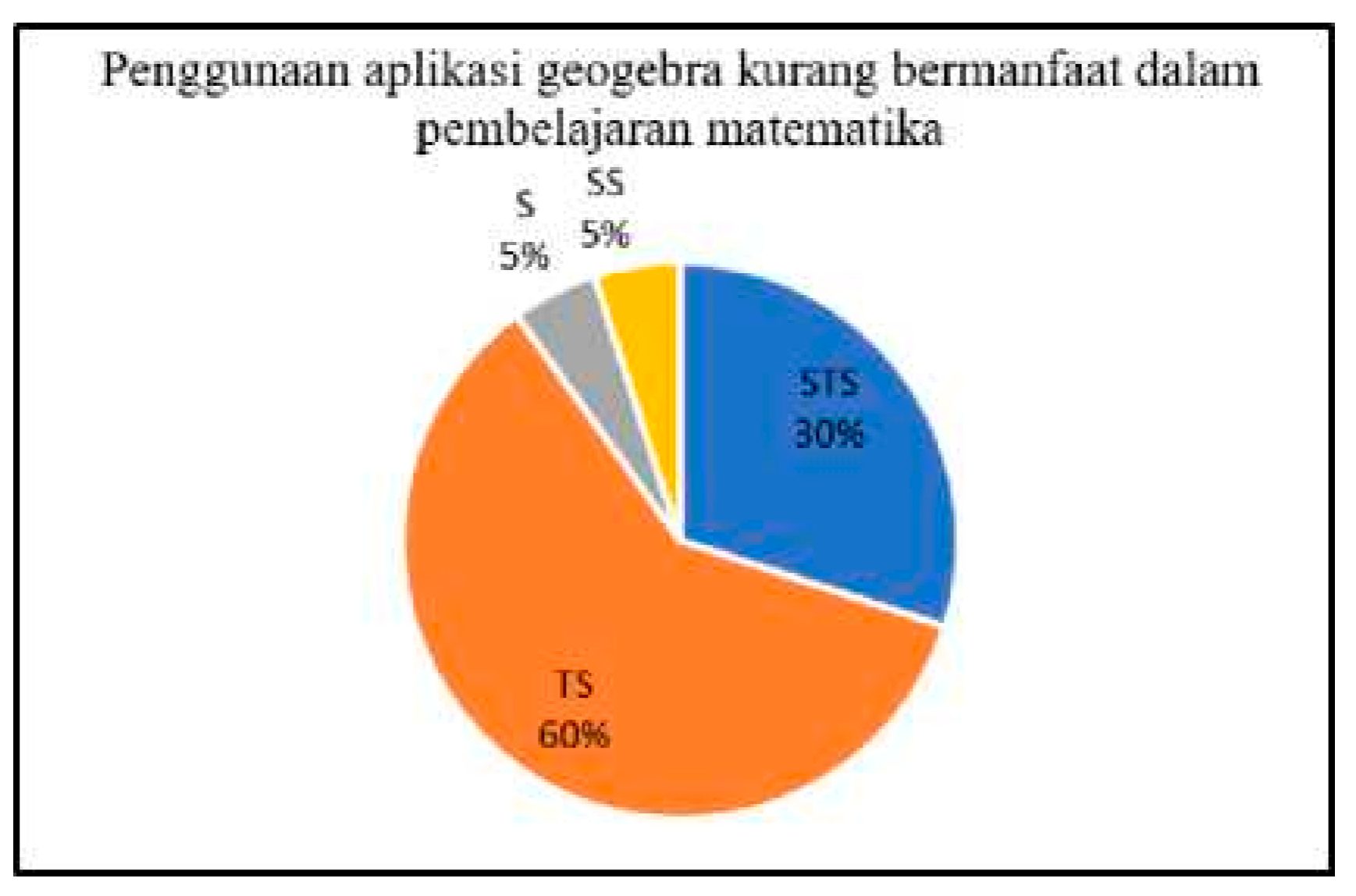

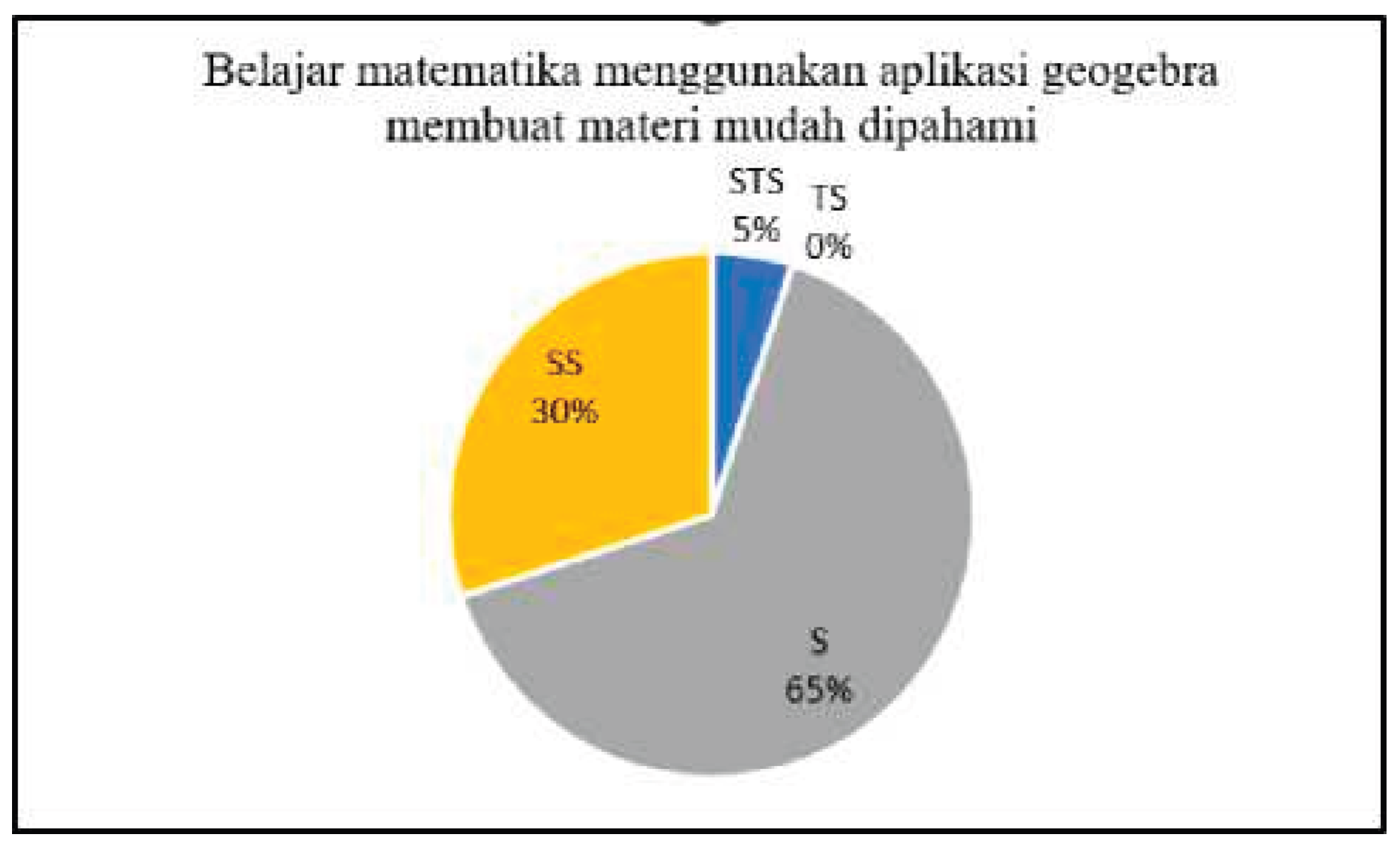

Building upon this context, the present study investigates the effectiveness of integrating GeoGebra within a PBL framework to enhance students’ mathematical communication abilities. [

75] The research questions are: (1) Is the improvement in mathematical communication greater among students taught via GeoGebra-assisted PBL than those taught via DL? (2) What percentage of students in the PBL–GeoGebra group meets the KKM in the posttest? (3) How do students perceive the use of GeoGebra? The study is delimited to two eighth-grade classes at SMP Negeri 1 Padangsidimpuan, North Sumatra, focusing exclusively on the topic of “Linear Equations.” Findings are expected to benefit schools by informing curriculum refinement, support teachers in diversifying digital pedagogy, empower students through active learning, and provide a foundation for future research on technology-enhanced mathematical communication. [

73,

74]