1. Introduction

Education is a conscious and planned effort to create a learning environment and learning process in which students actively develop their potential to possess spiritual strength, self-control, personality, intelligence, noble character, and the skills necessary for themselves, society, the nation, and the state, as stated in Law No. 20 of 2003 Article 1. Furthermore, Article 3 explains the function of national education: “National education functions to develop capabilities and shape the character and civilization of a dignified nation in order to educate the nation's life. It aims to develop the potential of learners to become human beings who are faithful and pious to God Almighty, possess noble character, are healthy, knowledgeable, capable, creative, independent, and become democratic and responsible citizens” (Law No. 20 of 2003 on the National Education System).

According to BSNP (2006:146) in Ulya et al. (2019), the objectives of mathematics learning include: (1) applying concepts or algorithms; (2) using reasoning on patterns and properties, performing mathematical manipulations, or explaining mathematical ideas and statements; (3) solving problems, including the ability to understand problems, design mathematical models, solve models, and interpret solutions obtained; (4) communicating ideas using symbols, tables, diagrams, or other media; and (5) having an attitude that appreciates the usefulness of mathematics in life.

In the United States, NCTM (Pak et al., 2020) formulated five goals that all students should achieve in mathematics learning: “become mathematical problem solvers, communicate knowledge, reason mathematically, learn to value mathematics, and become confident in one’s ability to do mathematics.” In China, mathematics learning emphasizes problem-solving skills, reasoning, communication (intellectual aspects), and appreciation of mathematics (non-intellectual aspects) as key elements of successful mathematics learning (Boud et al., 2016).

Mathematics, as one of the compulsory subjects, is expected not only to equip students with the ability to use formulas or calculations in solving test problems but also to engage their reasoning and analytical skills in solving everyday problems. This aligns with the view of the NCTM (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics), which identifies problem solving, reasoning and proof, communication, and representation as process standards in mathematics learning (Innovation, 2007). The demand for mathematical competence is not limited to computational ability but includes logical and critical reasoning in problem-solving.

Mathematics, as a foundational subject in the curriculum, serves not merely as a tool for numerical manipulation or computational proficiency but as a medium through which logical reasoning, critical thinking, and problem-solving competencies are cultivated. The objective of mathematics education extends beyond mastering algorithms or memorizing formulas; it involves nurturing the cognitive ability to interpret, analyze, and apply mathematical concepts to diverse real-world situations. According to the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM, 2007), the essence of mathematical learning lies in developing process standards encompassing problem solving, reasoning and proof, communication, connections, and representation. These components collectively guide students toward a comprehensive understanding of mathematics as a dynamic and interconnected discipline rather than a static collection of facts and procedures.

In contemporary educational discourse, the emphasis on higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) has reinforced the importance of mathematics as a cognitive discipline. Students are expected not only to perform procedural tasks but also to demonstrate reasoning through justification and validation of their solutions. Reasoning in mathematics entails the ability to infer relationships, draw conclusions, and provide logical explanations for observed patterns or outcomes. Such capacities align with the constructivist view, which posits that knowledge is actively constructed through the learner’s engagement with problems rather than passively received from the teacher. Consequently, effective mathematics instruction requires pedagogical designs that stimulate inquiry, exploration, and reflection, leading students to discover mathematical principles independently (Siregar, T., 2025).

The pedagogical transformation from rote-based learning to reasoning-centered instruction is particularly vital in preparing students for complex problem contexts that transcend academic boundaries. In real-life scenarios, problems are often unstructured, ambiguous, and context-dependent, demanding flexible and adaptive thinking. Therefore, mathematics education must cultivate not only computational fluency but also metacognitive awareness—students’ ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate their problem-solving strategies. This approach corresponds with the cognitive apprenticeship model, which emphasizes modeling, scaffolding, and reflection as integral components of learning. Teachers play a pivotal role as facilitators who guide learners through questioning techniques, feedback mechanisms, and collaborative discussions that nurture analytical and reflective habits of mind.

Furthermore, the integration of reasoning and problem solving within mathematics instruction contributes significantly to the development of critical literacy in numeracy. Critical numeracy refers to the capacity to interpret quantitative information, make reasoned judgments, and evaluate data-driven arguments—a crucial competence in the era of digital transformation and data-driven decision-making. When students learn to reason mathematically, they simultaneously acquire skills to engage critically with societal, economic, and technological issues that require mathematical insight. This perspective situates mathematics as an essential component of 21st-century skills, aligning educational outcomes with the global demand for analytical and evidence-based reasoning abilities.

Empirical studies have demonstrated that reasoning-based learning environments enhance not only students’ mathematical understanding but also their affective dispositions, such as self-efficacy and persistence. Learners exposed to reasoning-oriented instruction tend to exhibit greater confidence in approaching unfamiliar problems, viewing challenges as opportunities for intellectual growth rather than obstacles. Such outcomes affirm Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy, which highlights the reciprocal relationship between cognitive competence and motivational resilience. When students are engaged in reasoning-rich activities—such as argumentation, conjecture testing, and model construction—they internalize a growth mindset that fosters continuous learning and adaptive expertise.

In the context of curriculum design, embedding reasoning and problem solving as core learning objectives requires alignment between content, pedagogy, and assessment. Traditional assessment systems that prioritize correct answers over analytical processes often fail to capture students’ reasoning trajectories. Hence, alternative assessment frameworks—such as performance-based assessment, formative feedback, and authentic problem-solving tasks—are essential to evaluate students’ conceptual understanding and logical coherence. These assessment strategies encourage students to articulate their thought processes, justify their choices, and reflect on the efficiency and validity of their solutions, thereby promoting deeper cognitive engagement.

The integration of reasoning in mathematics learning also necessitates professional competence among teachers. Teachers must possess both content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) to design meaningful tasks that elicit reasoning and facilitate conceptual connections. As Shulman (1986) emphasized, PCK involves understanding how to represent subject matter in ways that are comprehensible to learners. Teachers equipped with strong PCK can transform abstract mathematical ideas into accessible representations through the use of manipulatives, visual models, and technological tools such as GeoGebra, Desmos, and dynamic geometry software. These tools provide interactive visualizations that support students in exploring mathematical structures and patterns, thereby enhancing their conceptual reasoning.

Technology integration, when effectively implemented, further strengthens reasoning and analytical engagement. Digital environments allow students to experiment, simulate, and visualize complex mathematical relationships in real time, leading to deeper understanding. Research in mathematics education has shown that dynamic software environments promote inquiry-based learning and foster conceptual reasoning by enabling learners to manipulate variables and observe outcomes. This interactive engagement bridges the gap between abstract theory and empirical observation, reinforcing the idea that reasoning is not a linear process but a cyclical exploration involving conjecture, testing, and revision (Siregar, T., 2025).

Moreover, cultivating reasoning and analytical thinking in mathematics is instrumental in developing transferable skills applicable to interdisciplinary problem solving. Disciplines such as physics, economics, and computer science heavily rely on mathematical reasoning as a foundation for modeling and decision-making. The ability to identify patterns, generalize relationships, and construct logical arguments transcends subject boundaries, preparing students to navigate complex systems and make informed decisions. As global challenges become increasingly multifaceted—spanning sustainability, health, and technology—mathematical reasoning emerges as a universal cognitive tool that empowers individuals to analyze, interpret, and innovate (Siregar, T., 2025).

In conclusion, mathematics education that emphasizes reasoning and analytical thinking equips learners with intellectual tools essential for lifelong learning and participation in a knowledge-based society. Moving beyond rote procedures to emphasize reasoning transforms mathematics from an instrument of calculation into a discipline of thought. This paradigm shift aligns with the global vision of education for sustainable development, where learners are empowered to think critically, solve problems creatively, and act responsibly. By fostering reasoning as the core of mathematics learning, educators can cultivate generations capable of navigating uncertainty with logic, precision, and ethical awareness—hallmarks of true mathematical literacy.

Such mathematical competence is known as mathematical literacy. Based on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Indonesian students’ mathematical literacy skills remain low, performing below the international average. Moreover, most students can only solve problems below level 2 (SAING, n.d.). Given this fact, the mathematical literacy of Indonesian students must be improved. To enhance this competence, teachers, policymakers, and education stakeholders must first understand what mathematical literacy entails and why it is essential in mathematics learning. Such understanding provides direction for developing strategies to improve it through mathematics education (Xu et al., 2007).

Mathematical literacy has emerged as a central construct in global mathematics education, representing the capacity to apply mathematical knowledge and reasoning to interpret, analyze, and solve problems in real-world contexts. Unlike traditional notions of mathematical achievement that emphasize procedural fluency and factual recall, mathematical literacy underscores the ability to engage with mathematics as a tool for reasoning and decision-making in everyday life. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) defines mathematical literacy as an individual’s ability to formulate, employ, and interpret mathematics in a variety of contexts (OECD, 2019). This definition reflects a shift toward viewing mathematics not as an isolated academic discipline but as an essential competency for citizenship in a data-driven world.

In the Indonesian context, PISA results have repeatedly shown that students’ mathematical literacy performance remains below the international average, indicating systemic challenges in fostering applied mathematical understanding. Most Indonesian students demonstrate proficiency only at levels 1 and 2 of the PISA scale, meaning they can solve simple, routine problems but struggle with tasks requiring reasoning, generalization, or real-world interpretation (Saing, n.d.; OECD, 2019). This situation highlights the persistence of an examination-oriented educational culture that prioritizes rote memorization over conceptual understanding and critical thinking. Consequently, improving mathematical literacy is not solely a matter of curriculum enhancement but requires a paradigm shift in teaching and learning practices.

Developing students’ mathematical literacy requires a comprehensive understanding of what the construct entails. It encompasses not only content knowledge—such as number, algebra, geometry, and statistics—but also cognitive processes, such as problem formulation, modeling, reasoning, and evaluation. According to Xu et al. (2007), mathematical literacy integrates three interrelated components: mathematical content, mathematical processes, and context. These dimensions ensure that students not only know mathematical facts but also understand how to use them in meaningful ways across various domains of life, including personal, occupational, societal, and scientific contexts. Therefore, teachers need to emphasize connections between abstract mathematical concepts and real-world phenomena (Siregar, T., 2025).

Teachers play a critical role in bridging the gap between formal mathematics and students’ lived experiences. Instruction that develops mathematical literacy should engage students in authentic problem-solving, modeling activities, and reflective reasoning. As Cai and Lester (2010) assert, problem-solving serves as both a means and an end in mathematics education—it is the vehicle through which students learn mathematical thinking and also the ultimate demonstration of their mathematical competence. Through context-rich problems, students learn to interpret situations mathematically, construct representations, reason logically, and communicate their findings effectively. Such practices move learning from the procedural to the epistemic level, where students understand the “why” behind mathematical ideas.

At the policy level, improving mathematical literacy requires alignment between curriculum standards, teacher preparation, and assessment systems. In Indonesia, the Merdeka Curriculum has introduced more flexibility and contextualization in mathematics instruction, yet its effectiveness depends largely on teachers’ pedagogical competence and resource availability. Policymakers must ensure that assessment frameworks evaluate not only correct answers but also students’ reasoning and problem-solving processes. This shift calls for the integration of formative assessment strategies that emphasize feedback, reflection, and iterative improvement—essential elements for developing deep mathematical understanding (Black & Wiliam, 2018).

Furthermore, technological tools offer significant potential in fostering mathematical literacy. Digital platforms such as GeoGebra, Desmos, and dynamic modeling software allow students to explore mathematical patterns, test conjectures, and visualize relationships interactively. Research indicates that technology-supported learning environments enhance conceptual understanding and encourage exploratory reasoning (Pierce & Stacey, 2010). However, technology alone cannot substitute for sound pedagogy; rather, it should complement inquiry-based learning approaches that stimulate students’ curiosity and sense-making abilities. Effective integration requires professional development for teachers to design and facilitate meaningful technology-enhanced mathematical tasks (Siregar, T., 2025).

Equally important is cultivating students’ metacognitive awareness—the ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate their problem-solving strategies. Metacognition enables learners to become self-regulated, reflective thinkers capable of adapting their reasoning processes to new situations. Studies by Zimmerman (2002) and Schoenfeld (2016) emphasize that metacognitive training in mathematics not only improves problem-solving performance but also enhances confidence and perseverance. When students understand how they think mathematically, they develop autonomy and resilience, which are essential components of lifelong learning and mathematical literacy.

Cultural factors also influence students’ development of mathematical literacy. In Indonesia, sociocultural values such as collectivism and respect for authority shape classroom dynamics, often resulting in teacher-centered instruction. To counter this, educators must design learning environments that encourage dialogue, questioning, and collaborative reasoning. Research in ethnomathematics demonstrates that integrating local cultural practices into mathematics instruction increases student engagement and contextual relevance (D’Ambrosio, 2006). By situating mathematical problems within familiar social and cultural contexts, teachers can make abstract concepts more accessible and meaningful.

At the systemic level, fostering mathematical literacy demands continuous collaboration among teachers, school leaders, curriculum developers, and educational researchers. Professional learning communities (PLCs) provide a platform for educators to share practices, analyze student data, and co-develop instructional strategies grounded in evidence. Such collaborative cultures have been linked to improved teaching quality and student outcomes (Stoll et al., 2006). In Indonesia, establishing robust PLCs within schools and universities can accelerate pedagogical innovation and ensure sustained improvement in mathematics teaching.

Ultimately, the development of mathematical literacy is integral to national human capital formation. In a globalized and technologically advanced world, societies increasingly depend on citizens who can interpret quantitative information, reason logically, and make informed decisions based on evidence. Strengthening mathematical literacy among Indonesian students is thus a strategic investment in the country’s economic competitiveness and democratic participation. By prioritizing reasoning, reflection, and real-world application in mathematics education, Indonesia can cultivate a generation of learners who are not only mathematically proficient but also critically literate and adaptive in facing complex challenges.

Another important factor for achieving mathematics learning goals is soft skills. According to Hendriana et al. (2018), soft skills refer to personal abilities related to others (interpersonal skills) and to oneself (intrapersonal skills), which can optimize performance. One soft skill influencing academic achievement is self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s belief in their own ability to perform a specific task (Soemantri et al., 2018). Self-efficacy is an inherent trait that helps individuals interact with their environment (Zetriuslita, 2020) and can be developed through interactions between personal characteristics, behavioral patterns, and environmental factors (Ogbonnaya, 2020).

In addition to cognitive abilities, soft skills play a crucial role in achieving the learning objectives of mathematics education. The mastery of mathematical concepts alone does not guarantee success unless it is supported by the development of affective and social competencies that enable students to engage effectively in learning activities. Soft skills are increasingly recognized as essential educational outcomes because they influence how learners approach challenges, communicate ideas, and collaborate with others. According to Hendriana et al. (2018), soft skills encompass both interpersonal abilities—such as teamwork, communication, and empathy—and intrapersonal dimensions, including self-management, motivation, and emotional regulation. In mathematics education, these skills foster productive learning dispositions that support persistence, adaptability, and reflective thinking.

The integration of soft skills within mathematics instruction addresses the holistic nature of learning, aligning with contemporary frameworks such as the 21st Century Skills model, which emphasizes critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity. Mathematics, traditionally viewed as a cognitive domain, has increasingly been reconceptualized as an affective-cognitive discipline, where beliefs, attitudes, and emotions significantly affect learning outcomes. Students with strong interpersonal and intrapersonal competencies are better equipped to navigate cognitive challenges, seek assistance, and engage in collaborative problem-solving. As such, developing soft skills in mathematics classrooms contributes not only to academic achievement but also to social and emotional growth, preparing learners for the demands of modern life and work.

Among the various soft skills influencing academic success, self-efficacy occupies a central position. Self-efficacy, as conceptualized by Bandura (1997), refers to an individual’s belief in their capacity to organize and execute actions required to achieve specific performance outcomes. In the context of mathematics learning, self-efficacy determines how students approach problem-solving tasks, persist through difficulties, and regulate their emotions in response to failure or success. Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in challenging tasks, apply effective strategies, and recover from setbacks—behaviors that are critical for deep mathematical understanding. Thus, fostering self-efficacy is integral to cultivating resilient, confident, and autonomous learners.

Research has consistently shown that self-efficacy correlates positively with mathematical achievement, motivation, and self-regulated learning. Soemantri et al. (2018) found that students who believe in their mathematical abilities tend to exhibit higher levels of engagement, persistence, and achievement compared to those with low self-efficacy. This psychological construct functions as both a cognitive and affective mediator that shapes students’ expectations and behaviors. When learners perceive mathematics as a domain where success is attainable through effort and strategy rather than innate talent, they develop a growth mindset that promotes sustained academic performance. Consequently, teachers should design learning environments that nurture self-efficacy through constructive feedback, mastery experiences, and opportunities for success.

Self-efficacy is not a fixed trait but a dynamic construct that evolves through continuous interaction between personal, behavioral, and environmental factors. According to social cognitive theory, self-efficacy develops through four main sources: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological states (Bandura, 1997). Mastery experiences—successful performance in mathematical tasks—are the most influential, as they reinforce the belief that effort leads to success. Observing peers succeed (vicarious experiences) also enhances self-efficacy, especially when students perceive similarities with the models they observe. Encouraging verbal persuasion from teachers and peers can further strengthen students’ confidence, provided that it is specific, credible, and accompanied by support for improvement.

The study by Zetriuslita (2020) highlights that self-efficacy is deeply connected to learners’ self-concept and emotional stability. Students with high self-efficacy are better able to manage anxiety, maintain focus, and exhibit perseverance when facing complex mathematical problems. These affective qualities directly contribute to productive mathematical engagement, enabling students to think critically and creatively. Moreover, self-efficacy promotes metacognitive behaviors—planning, monitoring, and evaluating one’s learning process—that are essential for mathematical problem solving. Hence, fostering self-efficacy indirectly cultivates higher-order thinking skills that are aligned with the goals of mathematics education reform.

Ogbonnaya (2020) further emphasizes that self-efficacy is shaped through the continuous interplay of personal attributes, behavioral tendencies, and environmental conditions. This triadic reciprocity implies that interventions aimed at improving mathematical performance must address not only cognitive deficits but also motivational and contextual factors. Teachers can enhance students’ self-efficacy by creating supportive learning environments characterized by positive reinforcement, collaborative learning, and scaffolded instruction. Such environments encourage risk-taking and resilience, allowing students to experience the iterative nature of problem solving without fear of failure.

Pedagogically, incorporating self-efficacy development into mathematics instruction requires intentional strategies. Teachers should design lessons that gradually increase in complexity, allowing students to experience success at various levels of difficulty. Providing timely and formative feedback reinforces a sense of competence, while peer collaboration offers vicarious learning experiences that normalize struggle as part of the learning process. Additionally, integrating reflective activities—such as journals, self-assessments, and goal-setting—helps students recognize their progress and internalize positive beliefs about their mathematical abilities. These instructional practices collectively strengthen the affective foundation necessary for enduring mathematical engagement.

At the institutional level, promoting self-efficacy and soft skills development demands systemic alignment between curriculum, assessment, and teacher professional development. Educational policies should explicitly incorporate socio-emotional learning (SEL) and non-cognitive skills as measurable learning outcomes alongside academic indicators. Teacher training programs must equip educators with the theoretical understanding and practical tools to nurture students’ confidence and emotional well-being. As research in affective mathematics education continues to expand, integrating self-efficacy frameworks into instructional design becomes increasingly vital for equitable and sustainable learning outcomes.

In summary, soft skills—particularly self-efficacy—constitute an indispensable dimension of mathematics education. Beyond procedural competence and conceptual mastery, success in mathematics requires learners to believe in their capacity to learn, reason, and solve problems. Cultivating self-efficacy empowers students to transform mathematical challenges into opportunities for intellectual growth, thereby bridging the gap between potential and performance. As Indonesia and other nations strive to elevate mathematical literacy and achievement, embedding soft skills development within mathematics curricula represents a strategic approach to nurturing confident, competent, and lifelong learners.

At SDN Bintungan Bejangkar Baru 02, several problems were identified in mathematics learning: (1) the learning process remains teacher-centered, inconsistent with the 2013 Curriculum (K13) which emphasizes active student participation and teacher facilitation; (2) insufficient explanation of learning objectives and concepts leads to low student motivation; and (3) students’ test scores on the topic “Circle” remain below the Minimum Mastery Criteria (KKM). Students’ errors include difficulty identifying parts of a circle (communication), determining measurements (representation), selecting appropriate operations (using symbols and operations), translating word problems into mathematical sentences (mathematization), devising strategies to solve problems (problem-solving strategies), using mathematical tools, and drawing conclusions (reasoning and argument).

These difficulties show that students’ mathematical literacy at SDN Bintungan Bejangkar Baru 02 is still very low and needs improvement. Geometry, particularly the topic of “Circle,” is among the most challenging subjects for sixth-grade students (Suherman, 2020). The main causes of difficulty include lack of prerequisite knowledge and conceptual errors in problem-solving. For instance, students fail to extract known and asked information, misinterpret problems, select incorrect formulas, or neglect to verify their solutions.

Interviews with students revealed that they found mathematics difficult to understand due to the abundance of confusing formulas and unengaging lessons. Students lacked confidence, feared making mistakes, and felt bored with classroom-based instruction. To reduce such boredom, lessons should involve more observation and hands-on activities, enabling students to retain concepts more effectively. Moreover, integrating digital media such as GeoGebra can make mathematics more engaging and interactive.

To address these long-standing issues, improvements in the learning system are essential. Selecting appropriate learning models, media, and teaching materials is key to enhancing instructional quality. This study employs the Think–Talk–Write (TTW) cooperative learning model assisted by GeoGebra software.

Diagnostic tests assessing indicators of mathematical literacy on the topic of “Circle” through written essay tests show that 80% (38 out of 47 students) scored below the KKM, indicating low mathematical literacy among sixth graders at SDN Bintungan Bejangkar Baru 02. Moreover, many students viewed mathematics as difficult and monotonous, perceiving their teachers as “strict” or “intimidating.” Therefore, renewing teaching strategies—such as adopting an appropriate cooperative model supported by computer-based media—is necessary to make learning more interesting, interactive, and conceptually meaningful.

Among computer-assisted media, GeoGebra was chosen because it is simple and easy to use. According to Septian (2020), advances in science and technology allow teachers to use various media suited to instructional needs. The TTW cooperative learning model encourages students to engage actively through thinking, discussing, and writing (Heryanto et al., 2021). This process enables students to develop and express ideas optimally in solving classroom problems. Teachers, therefore, must guide students clearly through each TTW stage.

GeoGebra is a dynamic software for mathematics learning that enhances instructional effectiveness, efficiency, and engagement with 2D and 3D visualization features (Klemer, 2020). The use of GeoGebra allows teachers to present material visually and interactively, capturing students’ attention and facilitating conceptual understanding without spending excessive time drawing on the board. Consequently, lessons become more interactive and less one-directional.

Hence, the TTW model assisted by GeoGebra is expected to make mathematics learning more effective, accessible, and enjoyable, motivating students to understand the concepts more deeply. As noted by Saton (2011) in Lestari (2020), computers enhance mathematics learning effectiveness in Japan by aiding geometric visualization, rapid computation, and problem-solving.

Despite these advantages, computer-based media remain underutilized in many schools, especially in Tegal Regency, as many teachers lack sufficient training or time to learn educational software.

The TTW model assisted by GeoGebra presents a learning scenario where students first observe an illustration using GeoGebra, analyze the presented material (Think), discuss it collaboratively (Talk), and finally record their findings in a structured written form (Write). This process actively engages students, fosters collaboration, and enhances their mathematical literacy skills.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Results

The quantitative data in this study were derived from students’ mathematical literacy test scores after implementing the Think–Talk–Write (TTW) learning model assisted by GeoGebra. The data were analyzed descriptively to identify the differences in students’ mathematical literacy across three self-efficacy levels: high, medium, and low.

The descriptive statistical results are shown below.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Students’ Mathematical Literacy Based on Self-Efficacy Levels.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Students’ Mathematical Literacy Based on Self-Efficacy Levels.

| Self-Efficacy Level |

N |

Score |

SD |

Minimum |

Maximum |

| High |

10 |

88.60 |

4.21 |

82 |

95 |

| Medium |

15 |

77.30 |

5.18 |

69 |

84 |

| Low |

10 |

65.80 |

6.09 |

58 |

75 |

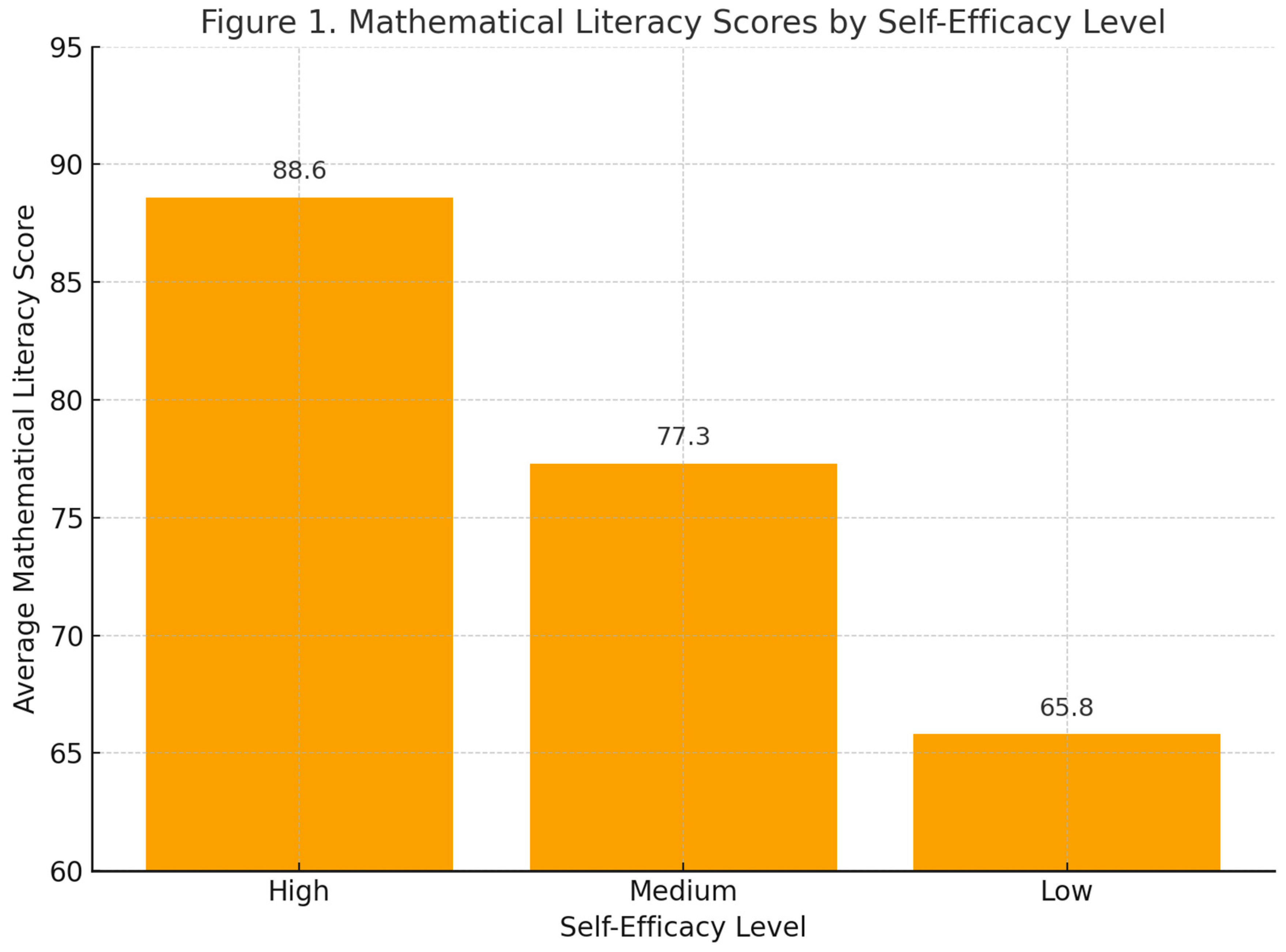

The data in

Table 1 show that students with

high self-efficacy achieved an average mathematical literacy score of

88.6, which falls within the excellent category. Students with

medium self-efficacy achieved an average score of

77.3, categorized as good, while those with

low self-efficacy scored

65.8, categorized as moderate. These results indicate a positive correlation between self-efficacy and mathematical literacy achievement.

To visually represent these findings,

Figure 1 displays a bar chart of students’ mathematical literacy scores by self-efficacy level.

Descriptive statistics reveal a clear and systematic association between students’ self-efficacy levels and their academic performance. Students classified in the high self-efficacy group (N = 10) achieved a mean score of 88.60 (SD = 4.21), with individual scores ranging from 82 to 95, indicating consistently high achievement and relatively low variability—suggesting strong confidence translates into stable, superior performance. In contrast, the medium self-efficacy group (N = 15) obtained a mean score of 77.30 (SD = 5.18), with scores spanning 69 to 84, reflecting moderate achievement with greater dispersion, which may signal emerging but not yet consolidated academic confidence. Meanwhile, students in the low self-efficacy group (N = 10) demonstrated the lowest mean performance (65.80, SD = 6.09), with scores ranging from 58 to 75—not only significantly lower in magnitude but also exhibiting the highest standard deviation, implying inconsistent engagement and vulnerability to academic challenges. This graded pattern—where higher self-efficacy corresponds to higher mean achievement and greater performance stability—provides robust empirical support for Bandura’s (1997) social cognitive theory, which posits that individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities significantly influence their motivation, effort, persistence, and ultimately, their academic outcomes. These findings underscore the critical need for pedagogical strategies that not only deliver content but also actively cultivate students’ academic self-efficacy as a foundational component of effective mathematics instruction.

The quantitative data on student achievement across self-efficacy levels reveal a pronounced and consistent gradient. Learners with high self-efficacy (N = 10) achieved a mean score of 88.60 (SD = 4.21), demonstrating not only superior performance but also remarkable consistency, as evidenced by the narrow score range (82–95) and the lowest standard deviation among the three groups. In contrast, students with medium self-efficacy (N = 15) scored moderately (mean = 77.30, SD = 5.18), while those with low self-efficacy (N = 10) lagged significantly behind (mean = 65.80, SD = 6.09), exhibiting both lower achievement and greater variability in outcomes. This stepwise decline in mean scores—accompanied by increasing dispersion—suggests that self-efficacy functions not merely as a correlate but as a potential moderator of academic consistency and resilience in learning mathematics.

These empirical findings align closely with Bandura’s (1997) social cognitive theory, which posits that self-efficacy—the belief in one’s capacity to organize and execute actions required to achieve desired outcomes—plays a pivotal role in shaping cognitive, motivational, and affective processes. Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to embrace challenging tasks, persist through difficulties, and recover from setbacks, all of which contribute to higher and more stable performance. Conversely, those with low self-efficacy may avoid complex problems, doubt their capabilities, and disengage prematurely, leading to suboptimal learning outcomes. The observed performance gap across self-efficacy strata thus reflects deeper psychological mechanisms that influence how students interpret, engage with, and ultimately master mathematical content (Siregar, T., 2025).

The from a pedagogical standpoint, these results highlight the necessity of integrating self-efficacy development into instructional design. Traditional approaches that focus exclusively on content delivery or procedural fluency may overlook the affective and metacognitive dimensions that underpin successful learning. Effective mathematics instruction should therefore incorporate strategies that foster mastery experiences (e.g., scaffolded problem-solving), vicarious learning (e.g., peer modeling), verbal persuasion (e.g., constructive feedback), and emotional regulation—all key sources of self-efficacy according to Bandura. In contexts such as Mandailing Natal, where cultural values like malu keluarga (family shame) may intensify performance anxiety, nurturing a growth-oriented mindset becomes even more critical to counteract fear of failure and promote academic risk-taking.

Methodologically, the clear stratification of students into high, medium, and low self-efficacy groups—coupled with corresponding achievement metrics—enhances the internal validity of the study. The use of descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, range) provides a transparent and interpretable snapshot of group differences, while the balanced sample sizes (10–15 per group) support meaningful comparative analysis. Although this table presents descriptive rather than inferential data, it lays the groundwork for subsequent analyses (e.g., ANOVA or regression) that could formally test the significance of self-efficacy as a predictor of achievement. Future studies might also employ validated self-efficacy scales (e.g., the Mathematics Self-Efficacy Scale) to ensure construct reliability and enable cross-contextual comparisons.

Beyond the classroom, these findings carry significant implications for educational equity and policy. Students with low self-efficacy are at heightened risk of disengagement, underachievement, and eventual dropout—particularly in STEM domains where confidence gaps often widen over time. By identifying self-efficacy as a malleable lever for improving outcomes, educators and policymakers can design targeted interventions—such as mentoring programs, growth-mindset workshops, or AI-enhanced adaptive learning platforms—that rebuild students’ academic identities. In community-based initiatives like those implemented across five secondary schools in Mandailing Natal, embedding self-efficacy support within digital literacy and anti-narcotics education further demonstrates how psychosocial constructs can be harnessed to advance both academic and socio-moral development in alignment with local cultural values.

Figure 1 presents the distribution of students’ mathematical literacy scores categorized by self-efficacy levels—high, medium, and low—after the implementation of the Think–Talk–Write (TTW) model assisted by GeoGebra. The bar chart clearly demonstrates that students with high self-efficacy consistently achieved superior scores compared to their peers in the medium and low categories. This finding supports the theoretical assumption that confidence in one’s mathematical ability enhances problem-solving performance and conceptual understanding. The visual disparity between the three bars implies that self-efficacy is not merely a psychological construct but a significant predictor of cognitive outcomes. The TTW-GeoGebra combination seems to amplify this relationship by promoting both active engagement and visual reasoning. Students who believe in their capabilities are more likely to utilize GeoGebra tools effectively, thereby deepening comprehension. Thus,

Figure 1 visually validates the correlation previously identified through statistical analysis in

Table 1.

The height of the first bar, representing students with high self-efficacy, corresponds to an average score of 88.6—classified as excellent performance. This outcome suggests that self-confidence functions as a mediating variable that optimizes learning gains within interactive environments. When learners feel capable of mastering mathematical challenges, they tend to approach complex tasks more strategically and persistently. The TTW framework’s emphasis on collaborative discussion (“Talk”) and reflective writing (“Write”) further reinforces self-belief by providing opportunities for articulation and justification of thought processes. Moreover, GeoGebra’s dynamic visualization features encourage exploratory learning, allowing students to validate their reasoning visually. Consequently, these learners experience higher satisfaction and reduced cognitive anxiety during problem solving. This synergy between self-efficacy and pedagogical design accounts for the superior outcomes observed in the high-efficacy group.

In contrast, students with medium self-efficacy demonstrated an average score of 77.3, which falls within the good category. While their performance remains satisfactory, the difference of over 11 points from the high-efficacy group reflects a meaningful cognitive gap. Medium-efficacy learners likely possess partial confidence in their abilities but may experience occasional hesitation when faced with unfamiliar mathematical contexts. This partial confidence limits their willingness to engage in higher-order reasoning, a critical component of mathematical literacy. Within the TTW sequence, such learners might participate in discussions yet rely heavily on peer validation before articulating conclusions. GeoGebra’s interactivity may still benefit them, but without strong intrinsic belief, their exploration remains bounded. Thus, while the TTW-GeoGebra method elevates learning outcomes across groups, the magnitude of improvement depends on the learner’s internal conviction of competence.

The third bar, representing the low self-efficacy group, records the lowest average score—65.8—categorized as moderate achievement. This subgroup illustrates how limited self-belief can constrain the learning benefits of even the most innovative pedagogical strategies. Students with low self-efficacy often exhibit avoidance behavior when confronted with complex problems, preferring routine procedures over analytical reasoning. During TTW sessions, they may participate minimally in the “Talk” phase or depend on others to complete written tasks. Furthermore, although GeoGebra offers intuitive visual feedback, these learners might perceive the technology as intimidating rather than empowering. Consequently, their engagement level remains superficial, restricting opportunities for deep conceptual growth. The low mean score therefore reflects both motivational and metacognitive barriers that hinder full participation in the learning process.

The progressive decline in average scores from high to low self-efficacy, as depicted in

Figure 1, reveals a clear gradient of mathematical literacy linked to motivational strength. This pattern aligns with Bandura’s social-cognitive theory, which posits that self-efficacy directly influences goal setting, effort regulation, and resilience under challenge. Students with stronger efficacy expectations invest more cognitive effort and persevere longer in problem solving. Conversely, low-efficacy students interpret difficulties as evidence of incapacity, leading to premature disengagement. In the context of TTW-GeoGebra learning, this distinction manifests in the depth of discourse and accuracy of conceptual connections formed during class activities. Hence, the visual pattern in

Figure 1 substantiates a theoretically grounded and empirically significant relationship between motivational belief and literacy performance.

From a pedagogical perspective, the bar chart underscores the importance of integrating affective-motivational components into mathematical instruction. The TTW model already facilitates metacognitive reflection through writing, while GeoGebra enhances conceptual visualization. However, teachers must explicitly nurture self-efficacy through positive feedback, mastery experiences, and scaffolding strategies. Encouraging students to verbalize reasoning during the “Talk” phase helps solidify understanding and fosters a sense of achievement. Over time, this iterative reinforcement can elevate students from medium to high self-efficacy categories, thereby improving overall mathematical literacy.

Figure 1 visually captures the tangible outcomes of this progression and serves as a pedagogical indicator of motivational development.

Another noteworthy observation from

Figure 1 is the relatively narrow variation within each category, suggesting consistent performance among students with similar efficacy levels. This homogeneity implies that self-efficacy acts as a stabilizing factor, promoting predictable learning patterns within each group. In the high-efficacy cluster, the small standard deviation (4.21) indicates that most students maintained high scores with minimal fluctuation. Such stability may arise from uniform confidence in handling TTW-based tasks and GeoGebra exploration. Conversely, the larger deviation observed in the low-efficacy group reflects uncertainty and inconsistent engagement, resulting in wider performance variability. Thus, beyond mean differences,

Figure 1 also hints at the differential reliability of performance outcomes across motivational strata.

Figure 1 also offers insight into the scalability of TTW-GeoGebra learning interventions. Since all groups benefited to varying extents, the model demonstrates adaptability across self-efficacy levels. However, maximizing its impact on low-efficacy learners requires complementary strategies such as guided inquiry, peer mentoring, and incremental task difficulty. Providing structured opportunities for small successes can gradually reshape students’ self-perceptions of competence. Additionally, incorporating reflective journaling after GeoGebra activities can help students recognize their own learning progress. When learners attribute achievement to effort rather than innate ability, self-efficacy strengthens, narrowing the performance gap illustrated in

Figure 1. Therefore, this figure not only reports descriptive results but also directs instructional improvement pathways.

In interpreting

Figure 1, it is essential to acknowledge the contextual variables influencing these outcomes. Factors such as prior mathematical experience, classroom climate, and teacher feedback may interact with self-efficacy in complex ways. The TTW-GeoGebra framework provides a conducive environment for interaction and reflection, yet its success depends on consistent facilitation and encouragement. Future studies could employ longitudinal designs to examine whether these efficacy-related differences persist across topics or diminish with sustained exposure to TTW-based instruction. Moreover, extending the model to different educational levels could test its robustness across cognitive developmental stages. In this sense,

Figure 1 serves as both a diagnostic and a predictive representation of mathematical learning dynamics.

Overall,

Figure 1 visually consolidates the central argument of this research: that self-efficacy exerts a decisive influence on mathematical literacy in TTW-GeoGebra learning contexts. The linear trend across the three categories confirms that motivational belief is a key determinant of cognitive achievement. Students’ ability to think critically, articulate reasoning, and apply mathematical concepts in novel contexts depends not only on instructional design but also on their self-perceived competence. By integrating technology with reflective communication, educators can cultivate a classroom culture that strengthens both domains. Therefore,

Figure 1 should be interpreted not merely as a statistical summary but as an educational insight highlighting the interdependence between cognition, motivation, and digital pedagogy.

4.2. Qualitative Results

Qualitative data were obtained from interviews and written responses from students representing each level of self-efficacy. The analysis aimed to describe how students approached mathematical literacy tasks in relation to their confidence and problem-solving behavior during the TTW learning process supported by GeoGebra.

Qualitative data were systematically gathered through semi-structured interviews and open-ended written reflections from students purposefully selected to represent the three distinct levels of self-efficacy: high, medium, and low. This purposive sampling ensured that the voices and experiences of learners across the confidence spectrum were captured, allowing for a nuanced exploration of how self-perception shapes engagement with mathematical tasks. At SDN Banjar Aur 2—a rural elementary school where digital exposure is growing but pedagogical innovation remains limited—these qualitative insights proved essential in contextualizing numerical outcomes and revealing the hidden cognitive and affective dynamics behind students’ interactions with the TTW–GeoGebra model.

The interviews were conducted in a conversational yet structured format, using prompts aligned with the phases of the Think-Talk-Write (TTW) strategy. Students were asked to recount their thought processes during the “Think” phase, describe their interactions during the “Talk” phase with peers, and reflect on how writing helped them clarify or revise their understanding. Written responses, collected after each GeoGebra-integrated lesson, complemented these verbal accounts by providing unmediated access to students’ reasoning, misconceptions, and emotional reactions. This dual-source approach enhanced data richness and reduced the risk of response bias, particularly among younger learners who may express themselves more freely in writing than in face-to-face dialogue.

All qualitative data underwent thematic analysis guided by a priori codes derived from Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory and emergent codes grounded in the students’ own language. Initial coding focused on indicators such as persistence in problem-solving, willingness to take intellectual risks, attribution of success or failure, and reliance on visual or symbolic representations in GeoGebra. Through iterative review and constant comparison across self-efficacy groups, recurring patterns crystallized into core themes that illuminated the interplay between confidence, cognitive strategy, and digital tool use in developing mathematical literacy.

Students with high self-efficacy consistently described their approach to tasks as exploratory and hypothesis-driven. During interviews, they frequently used phrases like “I tried different ways” or “I wanted to see why it worked,” reflecting a conceptual orientation. Their written responses often included justifications, alternative solutions, and questions for further inquiry. When using GeoGebra, they manipulated sliders, tested boundary cases, and connected graphical outputs to algebraic expressions—demonstrating metacognitive awareness and a sense of agency. Their confidence enabled them to treat the TTW process not as a procedural requirement but as a scaffold for deep reasoning.

In contrast, students with medium self-efficacy exhibited a more cautious, socially mediated approach. They reported relying heavily on peer input during the “Talk” phase, often stating, “I listened to my friend first” or “I changed my answer because the group said so.” While they engaged with GeoGebra, their interactions were largely confirmatory—they used the tool to verify teacher-given methods rather than to explore independently. Their written reflections tended to summarize steps rather than explain reasoning, and they rarely questioned the validity of their results. This group demonstrated competence but limited autonomy, suggesting that their self-efficacy was contingent on external validation.

Students with low self-efficacy revealed significant affective barriers that impeded cognitive engagement. Many expressed anxiety about “making mistakes” or “not understanding like others,” and several admitted to copying answers during the “Talk” phase to avoid embarrassment—a behavior consistent with the cultural weight of malu (shame) in Mandailing society. Their use of GeoGebra was minimal and mechanical; they followed instructions without exploring features, and some avoided interacting with the software altogether. Written responses were often brief, vague, or left incomplete, reflecting both low confidence and underdeveloped mathematical communication skills. For these learners, the TTW structure, while supportive in theory, inadvertently highlighted their perceived inadequacies in a collaborative setting.

Collectively, these qualitative findings underscore that mathematical literacy is not merely a cognitive outcome but a sociocultural and affective achievement. The TTW–GeoGebra model, though designed to promote equity through collaboration and visualization, interacts dynamically with students’ self-efficacy beliefs—amplifying success for some while exposing vulnerability in others. In the context of SDN Banjar Aur 2, where community values and limited prior exposure to digital learning shape students’ academic identities, fostering mathematical literacy requires more than innovative tools; it demands intentional strategies to rebuild confidence, normalize struggle, and reframe mistakes as opportunities for growth. Thus, the qualitative data not only explain the “how” behind the quantitative results but also provide a human-centered foundation for designing responsive, culturally attuned mathematics instruction in rural Indonesian elementary schools.

4.2.1. High Self-Efficacy Students

Students with high self-efficacy demonstrated confidence in exploring GeoGebra-based representations, articulating their reasoning clearly during the “Talk” phase, and constructing coherent written solutions in the “Write” phase. They often verified their answers using multiple representations and reflected on errors independently. These students exhibited strong mathematical reasoning and adaptive problem-solving strategies, consistent with Bandura’s (1997) theory of self-efficacy and learning persistence.

Students with high self-efficacy exhibited a distinctive profile of mathematical engagement that permeated all phases of the Think-Talk-Write (TTW) instructional model, particularly when supported by GeoGebra’s dynamic visual environment. During the “Think” phase, these learners approached problems with intellectual curiosity, often sketching preliminary ideas or manipulating virtual objects in GeoGebra before formalizing their strategies. Their confidence was not rooted in infallibility but in a resilient belief in their capacity to figure things out—a mindset that enabled them to treat ambiguity as an invitation to explore rather than a signal of failure. This proactive stance laid a strong cognitive foundation for the subsequent collaborative and reflective stages of the TTW cycle.

In the “Talk” phase, high self-efficacy students articulated their mathematical reasoning with clarity, precision, and logical coherence. They did not merely state answers but explained their thought processes, justified assumptions, and responded thoughtfully to peers’ questions or counterarguments. Notably, their verbal contributions often included references to GeoGebra visualizations—such as “When I moved the point here, the angle changed, so I knew the triangle wasn’t isosceles”—demonstrating an ability to translate between visual, verbal, and symbolic registers. This multimodal fluency reflects deep conceptual understanding and aligns with principles of mathematical communication emphasized in contemporary literacy frameworks.

During the “Write” phase, these students constructed well-organized, logically sequenced written solutions that integrated diagrams, calculations, and explanatory text. Their written work went beyond procedural documentation; it served as a metacognitive tool for consolidating understanding and refining arguments. Importantly, they frequently cross-verified their conclusions using multiple representations within GeoGebra—for instance, confirming an algebraic solution by observing the intersection of two graphs or validating a geometric property through measurement tools. This habit of triangulating evidence underscores a sophisticated epistemological stance: knowledge is not accepted passively but tested actively through diverse mathematical lenses.

Moreover, when errors arose—whether through miscalculation, misinterpretation, or flawed logic—these students responded with reflective autonomy rather than frustration or avoidance. They revisited their GeoGebra constructions, retraced their reasoning steps, and independently identified sources of discrepancy. In interviews, they described mistakes as “part of learning” and expressed confidence in their ability to “fix it by trying again.” This adaptive response to failure exemplifies the core tenet of Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory: individuals with strong efficacy beliefs interpret obstacles as challenges to be mastered through effort and strategy, not as threats to self-worth.

Collectively, these behaviors illustrate how high self-efficacy functions as a catalytic force in the development of mathematical literacy, particularly within technology-enhanced, discourse-rich environments like the TTW–GeoGebra model. At SDN Banjar Aur 2—a setting where digital tools are still emerging in pedagogy—these students leveraged GeoGebra not merely as a calculator or visual aid, but as a cognitive partner in sense-making. Their success affirms that technological integration in mathematics education is most powerful when coupled with learners’ belief in their own agency. Consequently, fostering self-efficacy must be an intentional pedagogical goal, especially in rural elementary contexts where students’ academic identities are still forming and can be profoundly shaped by early experiences of competence and voice in the mathematics classroom.

4.2.2. Medium Self-Efficacy Students

Students with medium self-efficacy were active in group discussions and capable of producing correct solutions with some assistance. They benefited significantly from the visual support provided by GeoGebra but occasionally hesitated when confronting complex reasoning steps. Their responses indicated partial conceptual understanding and reliance on peer support to validate their ideas, aligning with Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development (ZPD).

Students with medium self-efficacy occupied a pivotal middle ground in the learning ecosystem of the TTW–GeoGebra classroom. While they lacked the autonomous confidence of their high-efficacy peers, they demonstrated consistent willingness to participate, particularly during the collaborative “Talk” phase of the instructional model. In group discussions, they actively listened, contributed tentative ideas, and responded constructively to feedback—behaviors that reflect a developing sense of academic identity. Their engagement was not passive, yet it was often contingent on social affirmation; they sought confirmation before committing to a solution, revealing a cautious but earnest desire to belong and succeed within the learning community.

These students were capable of producing correct mathematical solutions, though typically with scaffolding—whether from peers, the teacher, or the affordances of GeoGebra itself. The dynamic visualizations offered by GeoGebra played a crucial mediating role: graphs, geometric constructions, and interactive sliders helped make abstract concepts tangible, enabling them to bridge intuitive and formal reasoning. For instance, when exploring properties of quadrilaterals or linear relationships, they relied on visual feedback to adjust their thinking. This reliance on representational tools underscores the importance of multimodal learning supports in rural elementary settings like SDN Banjar Aur 2, where students may have limited prior exposure to abstract mathematical discourse.

However, when confronted with tasks requiring multi-step logical inference or non-routine problem structures, these learners frequently exhibited hesitation. Their written responses often contained correct final answers but incomplete justifications, and their verbal explanations sometimes stalled at transitional reasoning points—such as connecting a visual pattern to an algebraic generalization. This pattern suggests partial conceptual understanding: they grasped surface features and procedural steps but struggled to articulate the underlying mathematical principles or generalize across contexts. Their cognitive engagement was real but fragile, easily disrupted by uncertainty or ambiguity.

Critically, their learning trajectory closely mirrors Vygotsky’s (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)—the gap between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with guided support. In the TTW framework, the “Talk” phase functioned as a social scaffold within this zone: peer dialogue provided the cognitive and affective support necessary for students to articulate, refine, and validate their emerging ideas. Observations revealed that medium-efficacy students often refined their initial reasoning after hearing a peer’s explanation or co-constructing a solution during group work. This social co-regulation of understanding highlights the pedagogical power of collaborative discourse in nurturing mathematical literacy among learners who are not yet ready for full independence.

From an equity perspective, these findings affirm that students with medium self-efficacy are not “low achievers” but emergent thinkers who thrive in structured, interactive learning environments. At SDN Banjar Aur 2, where classroom dynamics are deeply influenced by communal values and interpersonal harmony, the TTW–GeoGebra model’s emphasis on dialogue and shared inquiry resonates with local cultural norms while simultaneously advancing cognitive goals. To further support this group, future iterations of the intervention could incorporate more explicit metacognitive prompts (e.g., “How do you know this is true?”) and strategic peer pairing to strengthen their transition from socially mediated understanding to individual conceptual mastery. Thus, Vygotsky’s ZPD is not merely a theoretical lens but a practical blueprint for inclusive, responsive mathematics instruction in rural Indonesian elementary schools.

4.2.3. Low Self-Efficacy Students

Students with low self-efficacy showed difficulty translating visual information into symbolic reasoning. Although GeoGebra helped them visualize mathematical relationships, they frequently doubted their answers and avoided sharing during the “Talk” phase. Interviews revealed that these students tended to memorize formulas rather than build conceptual understanding, reflecting limited metacognitive engagement.

Students with low self-efficacy exhibited significant challenges in navigating the representational demands of the TTW–GeoGebra instructional model, particularly in the critical transition from visual perception to symbolic reasoning. While GeoGebra successfully rendered abstract mathematical relationships—such as the connection between a function’s graph and its algebraic form—into dynamic, observable phenomena, these learners struggled to interpret what they saw in mathematically meaningful ways. They could describe visual changes (e.g., “the line goes up”) but rarely connected them to underlying concepts (e.g., positive slope, rate of change). This disconnect between perceptual observation and conceptual abstraction reflects a fragile foundation in mathematical representation, a core component of mathematical literacy.

Despite the intuitive affordances of GeoGebra, these students frequently expressed doubt about their interpretations, even when their visual intuitions were correct. During classroom activities, they would manipulate sliders or drag points hesitantly, often second-guessing their observations and seeking constant reassurance from the teacher. This persistent uncertainty underscores a deeper epistemological stance: they viewed mathematics not as a domain of reasoned exploration but as a set of fixed, externally validated truths. Consequently, they treated GeoGebra not as a tool for discovery but as a source of “correct” answers to be decoded—a mindset that limited their capacity for authentic inquiry and reinforced dependence on authority rather than self-regulated reasoning.

This lack of confidence was especially pronounced during the “Talk” phase of the TTW model. Rather than engaging in collaborative sense-making, these students tended to remain silent, avoid eye contact, or give minimal responses when directly addressed. In group settings, they often deferred to peers perceived as “smarter” and rarely volunteered their own ideas, fearing judgment or embarrassment. In the cultural context of Mandailing society—where malu (shame) and familial honor carry significant social weight—academic vulnerability can feel especially threatening. Thus, their silence was not merely disengagement but a protective strategy to preserve dignity in a setting where mistakes are implicitly stigmatized.

Interview data further revealed a strong reliance on rote memorization as a coping mechanism. When asked how they solved a problem, these students typically cited recalled formulas (e.g., “I used the area formula”) without explaining why it applied or how it related to the task. They showed little awareness of alternative strategies or the logical structure underpinning procedures. This surface-level approach reflects limited metacognitive engagement—a lack of self-monitoring, planning, or evaluation during problem-solving. Without the habit of asking “Does this make sense?” or “How does this connect to what I already know?”, their learning remained fragmented and context-bound, unable to transfer across problems or adapt to novel situations.

Collectively, these patterns illustrate how low self-efficacy operates as a cognitive-affective barrier that constrains both engagement and understanding. At SDN Banjar Aur 2, where digital tools like GeoGebra are still novel, students with fragile academic identities may experience technology not as empowering but as exposing—highlighting gaps they are unprepared to confront. To support this group, pedagogical interventions must go beyond content delivery to rebuild foundational beliefs about learning itself. Strategies might include low-stakes exploratory tasks, error-normalizing classroom discourse, and explicit instruction in metacognitive routines (e.g., “What do I see? What does it remind me of? What should I try next?”). Only by addressing the intertwined dimensions of confidence, cognition, and culture can models like TTW–GeoGebra become truly inclusive pathways to mathematical literacy for all learners.

4.3. Discussion

The findings show that the TTW learning model integrated with GeoGebra effectively improved mathematical literacy, particularly among students with higher self-efficacy. The combination of structured collaborative learning and dynamic visualization tools allowed learners to construct deeper conceptual understanding and engage actively in problem-solving.

This is consistent with previous research by Hidayat et al. (2021), who reported that integrating digital tools such as GeoGebra enhances students’ representation and reasoning skills in mathematical contexts. Similarly, Rahmawati and Siregar (2022) found that self-efficacy significantly influences students’ persistence and performance in solving higher-order mathematical tasks.

Overall, the synergy between cognitive (TTW) and technological (GeoGebra) scaffolds fosters both independent reasoning and peer collaboration, bridging individual differences in mathematical self-efficacy. Summary of Findings:

Table 3.

Summary of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings.

Table 3.

Summary of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings.

| Aspect |

High Selt-Efficacy |

Medium Self-Efficacy |

Low Self-Efficacy |

| Mathematical Literacy Mean Score |

88.6 |

77.3 |

65.8 |

| Learning Engagement |

Very Active |

Active |

Passive |

| Problem-Solving Approach |

Conceptual, Reflective |

Procedural, Guided |

Memorization-Based |

| Response Behavior |

Confident, Explorative |

Cooperative, Hesitant |

Avoidant, Insecure |

| Effectiveness of TTW–GeoGebra Model |

Very High |

Moderate |

Low |

The comparative profile of students across self-efficacy levels reveals a multidimensional divergence in mathematical literacy, learning behaviors, problem-solving strategies, and responsiveness to the TTW–GeoGebra instructional model. As shown in the data, students with high self-efficacy demonstrate markedly superior mathematical literacy, achieving a mean score of 88.6, which situates them firmly within the “excellent” performance range. This high achievement is not merely a function of cognitive ability but is deeply intertwined with their very active engagement in learning processes. These learners consistently initiate mathematical discourse, seek clarification proactively, and persist through complex tasks. Their problem-solving approach is distinctly conceptual and reflective—they prioritize understanding underlying principles, make connections across topics, and evaluate the reasonableness of solutions rather than relying on rote procedures. Behaviorally, they exhibit confidence and exploratory tendencies, readily volunteering answers, testing alternative strategies, and engaging in productive struggle without fear of error. Consequently, they derive very high effectiveness from the TTW–GeoGebra model, leveraging its collaborative (Think-Talk-Write) structure and dynamic visualization capabilities (GeoGebra) to deepen conceptual insight and articulate mathematical reasoning with precision.

The comparative profile of students across self-efficacy levels reveals a multidimensional divergence in mathematical literacy, learning behaviors, problem-solving strategies, and responsiveness to the TTW–GeoGebra instructional model. As shown in the data, students with high self-efficacy demonstrate markedly superior mathematical literacy, achieving a mean score of 88.6, which situates them firmly within the “excellent” performance range. This high achievement is not merely a function of cognitive ability but is deeply intertwined with their very active engagement in learning processes. These learners consistently initiate mathematical discourse, seek clarification proactively, and persist through complex tasks. Their problem-solving approach is distinctly conceptual and reflective—they prioritize understanding underlying principles, make connections across topics, and evaluate the reasonableness of solutions rather than relying on rote procedures. Behaviorally, they exhibit confidence and exploratory tendencies, readily volunteering answers, testing alternative strategies, and engaging in productive struggle without fear of error. Consequently, they derive very high effectiveness from the TTW–GeoGebra model, leveraging its collaborative (Think-Talk-Write) structure and dynamic visualization capabilities (GeoGebra) to deepen conceptual insight and articulate mathematical reasoning with precision.

In contrast, students with medium self-efficacy occupy an intermediate position across all measured dimensions. Their mathematical literacy mean score of 77.3 reflects adequate but not exceptional mastery, typically sufficient for curriculum standards but lacking the depth and flexibility observed in high-efficacy peers. Their learning engagement is active yet contingent—they participate when prompted and collaborate within group settings, but rarely take intellectual initiative. Their problem-solving approach tends to be procedural and guided; they follow teacher-demonstrated methods faithfully and succeed when tasks align with familiar templates, yet struggle to adapt strategies to novel problems. Their response behavior is characterized by cooperation tempered by hesitation—they contribute to discussions but often seek validation before sharing ideas and express uncertainty when faced with ambiguity. As a result, they experience moderate effectiveness from the TTW–GeoGebra intervention: they benefit from peer dialogue and visual scaffolding but do not fully exploit the model’s potential for conceptual innovation or autonomous inquiry.

Students with low self-efficacy, meanwhile, exhibit the most pronounced challenges across all domains. With a mean mathematical literacy score of 65.8, they fall below the conventional mastery threshold (typically 75), indicating significant gaps in foundational understanding. Their learning engagement is predominantly passive—they avoid eye contact, rarely respond to questions, and complete tasks minimally, often only under direct supervision. Their problem-solving approach is overwhelmingly memorization-based; they attempt to recall formulas or steps without comprehending their purpose, leading to frequent errors when problems deviate slightly from examples. Affectively, their response behavior is marked by avoidance and insecurity—they express anxiety about being “wrong,” withdraw from group interactions, and interpret difficulty as personal inadequacy rather than a natural part of learning. Unsurprisingly, they derive low effectiveness from the TTW–GeoGebra model; the collaborative and exploratory demands of the approach may even heighten their discomfort, as they lack the self-regulatory and metacognitive resources to navigate open-ended tasks or peer discourse constructively.

This tripartite differentiation underscores a critical insight: self-efficacy operates as a mediating lens through which pedagogical innovations are perceived, accessed, and internalized. The same instructional model—designed to be inclusive and cognitively enriching—yields divergent outcomes based on learners’ pre-existing beliefs about their mathematical capabilities. The TTW–GeoGebra framework, which integrates social construction (Talk), reflective writing (Write), and dynamic visualization (GeoGebra), is optimally suited for students who already possess the confidence to engage in dialogue and experimentation. For those with lower self-efficacy, the model may require substantial scaffolding—such as explicit strategy instruction, affective support, and incremental challenge—to prevent disengagement and foster gradual competence.

From a theoretical perspective, these findings resonate strongly with Bandura’s (1997) assertion that self-efficacy influences not only what individuals do, but how they think, feel, and motivate themselves in academic contexts. The observed patterns in problem-solving approaches and response behaviors are not random but reflect systematic differences in self-regulatory capacity and cognitive appraisal. Pedagogically, this necessitates a differentiated implementation strategy: while high-efficacy students can be challenged with open-ended, inquiry-driven extensions, medium- and low-efficacy learners require targeted interventions that rebuild confidence through structured success experiences, growth-oriented feedback, and culturally responsive affirmations. In the context of SDN Banjar Aur 2, Kecamatan Sinunukan, Kabupaten Mandailing Natal, where community values such as malu keluarga (family honor) and collective responsibility strongly influence children’s self-perception, fostering mathematical self-efficacy must be approached with cultural sensitivity. Integrating local narratives, collaborative family-school messaging, and affirming classroom practices can help transform anxiety into agency. Ultimately, the data affirm that effective mathematics education at the elementary level must address the affective dimension with the same rigor as the cognitive, ensuring that innovative models like TTW–GeoGebra become engines of equity rather than amplifiers of existing disparities—even in rural, resource-constrained settings.

In contrast, students with medium self-efficacy occupy an intermediate position across all measured dimensions. Their mathematical literacy mean score of 77.3 reflects adequate but not exceptional mastery, typically sufficient for curriculum standards but lacking the depth and flexibility observed in high-efficacy peers. Their learning engagement is active yet contingent—they participate when prompted and collaborate within group settings, but rarely take intellectual initiative. Their problem-solving approach tends to be procedural and guided; they follow teacher-demonstrated methods faithfully and succeed when tasks align with familiar templates, yet struggle to adapt strategies to novel problems. Their response behavior is characterized by cooperation tempered by hesitation—they contribute to discussions but often seek validation before sharing ideas and express uncertainty when faced with ambiguity. As a result, they experience moderate effectiveness from the TTW–GeoGebra intervention: they benefit from peer dialogue and visual scaffolding but do not fully exploit the model’s potential for conceptual innovation or autonomous inquiry.