1. Introduction

Pedagogy is widely understood as the holistic process of equipping learners with the essential skills, attitudes, and dispositions necessary for their intellectual and personal development. Recent studies emphasize that pedagogy is not limited to the mere transfer of knowledge but extends to fostering critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills that are essential in the 21st century [

51]. It incorporates not only teaching methods but also the theoretical foundations of how learners acquire and apply knowledge in different contexts. Contemporary research suggests that effective pedagogy requires alignment between curriculum design, teaching strategies, and student learning outcomes [

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, pedagogy is now seen as a transformative tool that connects education with broader social and cultural goals. For example, in higher education, pedagogy is crucial in shaping students into active contributors to national development [

18,

19]. This shift reflects the idea that teaching is both a professional and ethical practice embedded in social responsibilities. Importantly, pedagogy encompasses values that promote inclusivity, equity, and lifelong learning [

67]. Hence, pedagogy is not static but dynamic, constantly adapting to meet the needs of learners and society. This conceptualization underpins the importance of pedagogy as the foundation of educational transformation in modern contexts.

Bourn’s definition, as cited in earlier works, has been expanded in recent scholarship to capture the multidimensionality of pedagogy. Pedagogy today involves understanding not only how learners engage with knowledge but also how digital and multicultural contexts shape the learning process [

73,

74,

75,

76]. Theories of pedagogy emphasize its role in bridging the gap between traditional instruction and innovative approaches that integrate technology. Researchers argue that effective pedagogy requires educators to design lessons that balance disciplinary knowledge with real-world applications [

55]. This is particularly critical in higher education, where students are expected to transition from passive recipients of knowledge to active participants in scholarly discourse. Pedagogy is also being redefined to include dialogic teaching, where interaction and collaboration between teacher and learner play central roles [

16]. Furthermore, pedagogical models now highlight the importance of culture as an integral component of learning, aligning with global perspectives on intercultural education. This integration of culture ensures that education remains relevant and inclusive in diverse societies. Thus, pedagogy functions both as a science and an art, guiding how knowledge is communicated and received. In this sense, it provides a framework for developing meaningful and transformative educational experiences.

Beyond teaching methodologies, pedagogy also includes assessment practices, which are increasingly viewed as integral to the learning process. Recent scholarship demonstrates that assessment should not merely serve as a measure of student performance but as a tool for enhancing learning outcomes [

83]. Innovative approaches to assessment, such as formative and authentic assessments, are being widely adopted in higher education. These methods encourage students to apply their knowledge in practical contexts rather than relying solely on rote memorization [

97,

98,

99,

100]. By integrating assessment into pedagogy, educators can provide feedback that promotes reflection, self-regulation, and deeper learning. This aligns with global calls for assessment practices that foster equity and inclusivity [

37]. Moreover, assessment is being reconceptualized to capture a wider range of student skills, including creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking. This holistic approach reflects the evolving demands of the labor market and societal needs [

71]. Therefore, pedagogy is not complete without assessment, as it enables continuous improvement of both teaching and learning. The integration of assessment into pedagogy underscores the interconnectedness of instructional design, delivery, and evaluation.

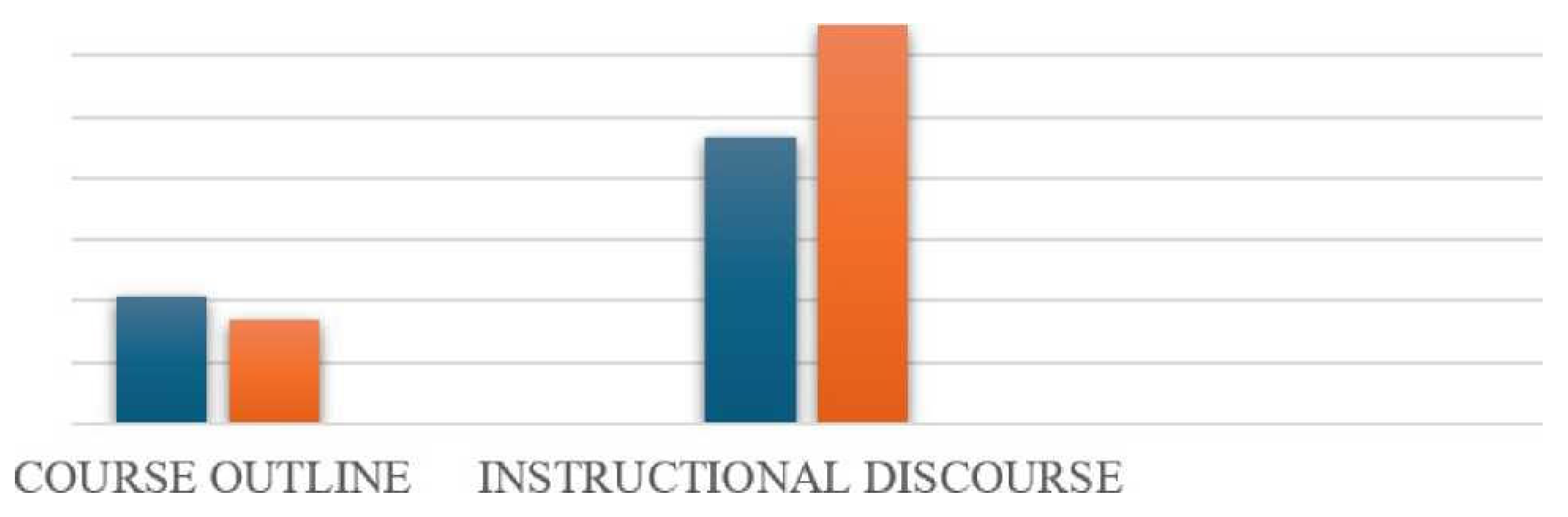

Pedagogical practices in higher education are often operationalized through course development, lesson planning, instructional delivery, and assessment strategies. Each of these components is essential for ensuring the effectiveness of teaching and learning processes. For instance, course outline development serves as a roadmap for both instructors and students, ensuring clarity of objectives and expectations [

128]. Lesson preparation allows instructors to align content with student needs and contextual realities. Instructional delivery, whether face-to-face or digital, has increasingly relied on innovative approaches such as blended learning and flipped classrooms [

30]. These approaches are reported to enhance student engagement and promote active learning. Assessment practices, particularly examination design, also play a central role in determining the extent to which learning outcomes are achieved [

124]. Scholars argue that lecturers’ examination questions should be designed to assess not only lower-order skills but also higher-order thinking abilities. This highlights the critical role of pedagogy in shaping the intellectual capacity of students. Ultimately, pedagogical practices reflect the practical dimensions of theory in action. They serve as a tangible demonstration of how pedagogy translates into student learning experiences.

In this study, pedagogy is conceptualized comprehensively to encompass classroom discourse, course outline development, and assessment practices. This tripartite framework reflects the recognition that teaching involves multiple dimensions, each contributing to student learning. Classroom discourse emphasizes interaction and the communicative dynamics between lecturers and students, which shape knowledge construction [

7]. Course outline development provides a structural foundation for learning, ensuring that teaching is systematically aligned with institutional and disciplinary goals. Assessment, in turn, ensures that learning outcomes are evaluated in a manner consistent with both academic and professional expectations [

70]. Taken together, these elements provide a holistic understanding of pedagogy as both a theoretical and practical construct. This conceptualization is significant in the context of higher education in Indonesia, where lecturers are increasingly expected to adopt evidence-based pedagogical practices. Moreover, this framework resonates with global trends emphasizing the integration of pedagogy, curriculum, and assessment into a coherent whole [

81]. By situating pedagogy within these dimensions, this study contributes to the broader discourse on improving educational quality and relevance. Hence, pedagogy here is not reduced to teaching techniques but is understood as a multidimensional process integral to higher education reform.

Pedagogy is the process of inculcating in students essential skills, values, attitudes, and contemporary issues for proper growth, development, and transformation of both the individual and the nation. Bourn [

95,

96] defines pedagogy as the methods of teaching, and the theoretical issues concerning how children learn, how teaching is done, how the curriculum is structured, and how culture is integrally embedded within the curriculum. Pedagogy can also be seen as incorporating assessment [

79]. Activities such as course outline development, lesson preparation, instructional delivery, examination questions, and marking of students’ scripts used to develop students’ skills are termed

pedagogical practices [

110]. Therefore, in this study, pedagogy is conceptualised to include classroom-related discourse (instructional delivery), course outline development, and assessment (focusing on lecturers’ examination questions).

Before classroom teaching begins, lecturers prepare a course outline that serves as a guide for teaching and learning. Classroom-related discourse or instructional delivery is where lecturers attempt to help students understand certain concepts and to assess their understanding [

54,

79,

111,

112]. The process of determining students’ understanding of concepts is termed

assessment, particularly formative assessment. According to [

60,

61,

62,

63], assessment is the gathering of information for a particular purpose. It has also been noted that assessment aims “to determine the value, significance, or extent of something; it comes from the Latin word

assidere, which means ‘to sit by’” [

79]. A careful examination of the definitions of assessment suggests that it is not only used to determine students’ understanding of classroom concepts but also to make certain decisions—such as promoting students from one level to another—at the end of a course. This is referred to as

summative assessment. Thus, in this study, assessment is defined as a systematic process of collecting, analysing, and interpreting data to determine students’ understanding of concepts in the classroom (formative assessment) and their progress in a course or programme (summative assessment). Importantly, formative assessment is a constituent part of classroom discourse, while summative assessment informs decisions on students’ progression to the next level. Furthermore, the nature of classroom practices, such as lecturers’ approaches to teaching, largely determines the nature of summative assessment practices, as reflected in the types of examination questions students are required to answer. [

3,

4,

10]

Pedagogical practices often appear dichotomous: those that require students’ passive submission to knowledge provision, and those that demand active participation and critical reasoning in constructing knowledge. For example, [

29] distinguishes between

regulatory pedagogy and

participatory pedagogy. In regulatory pedagogy, the learning environment is controlled by the teacher, making lecturers focus on lecturing without actively engaging students in 21st-century skills such as communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity [

29]. Lecturers adopting this orientation often emphasise rote learning, note-taking, and memorisation. On the other hand, participatory pedagogy engages students actively in teaching and learning [

117,

118], requiring their full participation and reasoning. Participatory pedagogy encourages lecturers to emphasise higher-order thinking skills (HOTS), providing a foundation for students’ reasoning and criticality. These practices contribute to fulfilling the goals of higher education by fostering personal growth, intellectual development, criticality, problem-solving skills, communication, collaboration, and active citizenship [

120,

121,

122]. Thus, many Indonesian higher education institutions have also integrated

Critical Thinking and

21st-century skill development into curricula to align with the transformative aims of education. Higher-order thinking skills, fostered by participatory pedagogy, are often preferred to lower-order thinking skills operationalised by regulatory pedagogy [

110]. This preference stems from HOTS’ capacity to empower students as critical thinkers capable of solving societal problems [

42,

43].

Despite this, several studies [

5] have revealed that higher education students—particularly in developing contexts—still struggle to demonstrate HOTS effectively, often resulting in limited employability after graduation. This has motivated numerous global studies [

40] investigating lecturers’ pedagogical practices. However, many of these studies have primarily explored the

nature of lecturers’ practices, without systematically quantifying the extent to which lecturers emphasise either higher-order or lower-order thinking skills.

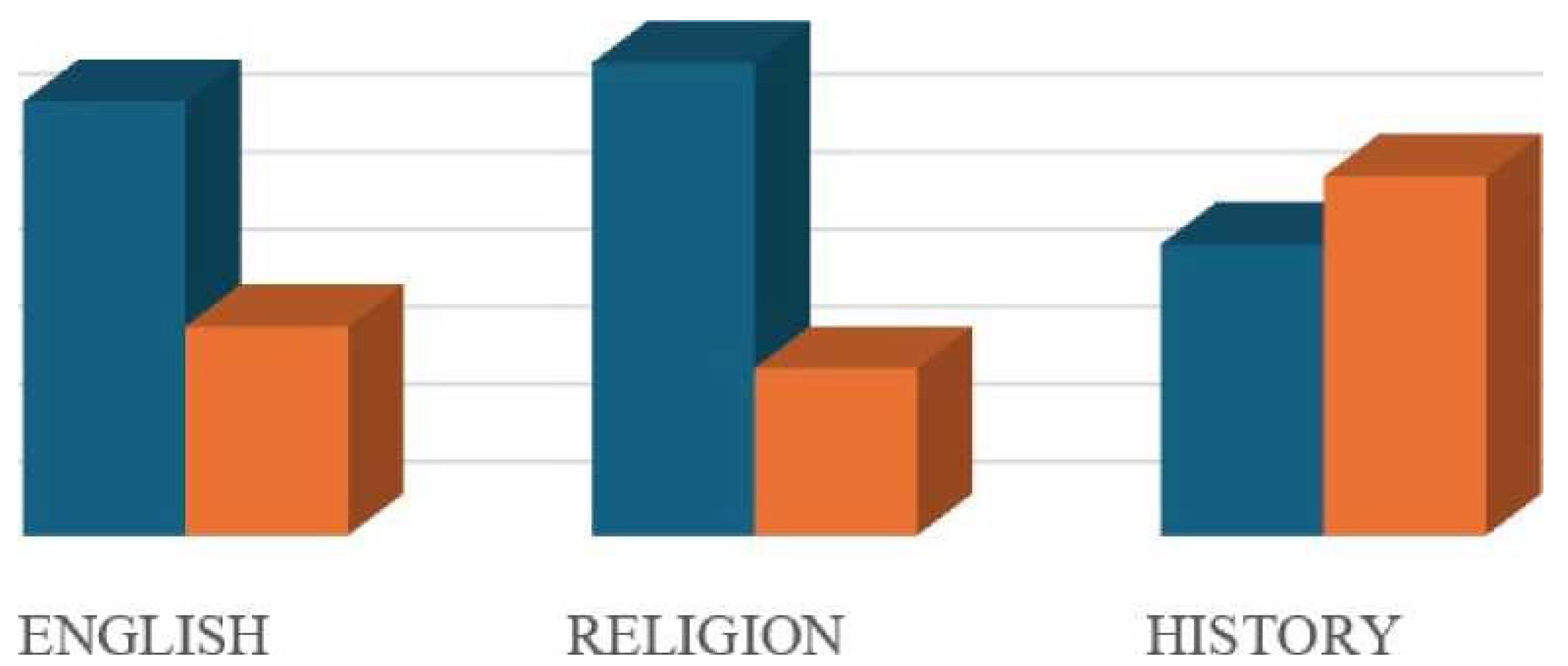

For instance, [

58,

59] highlight disciplinary differences, noting the importance of evidence use in History and clarity of expression in English. [

119,

120] examines institutional factors such as policy, gender, and lecturer status, showing variations in referencing, plagiarism, and feedback practices. Similarly, [

31,

32,

33] reports that lecturers often focus on textual structure but lack emphasis on critical engagement with ideas, while [

50,

51] observes lecturers attempting a balanced approach, encouraging student participation but facing challenges in implementation. Other studies [

12,

13] reinforce the mixed picture of practices, ranging from teacher-centred approaches for first-year students to student-centred ones in later years.

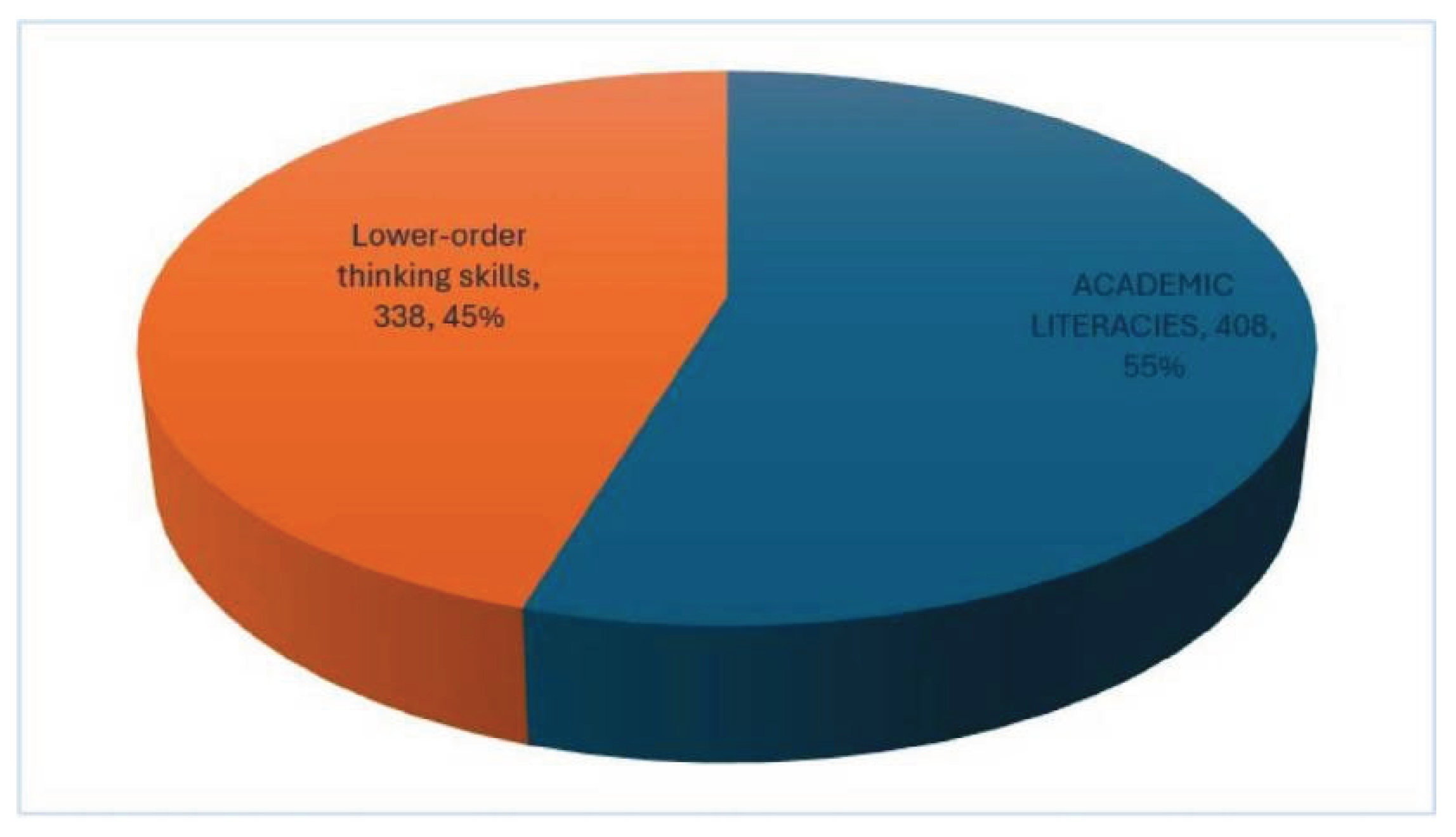

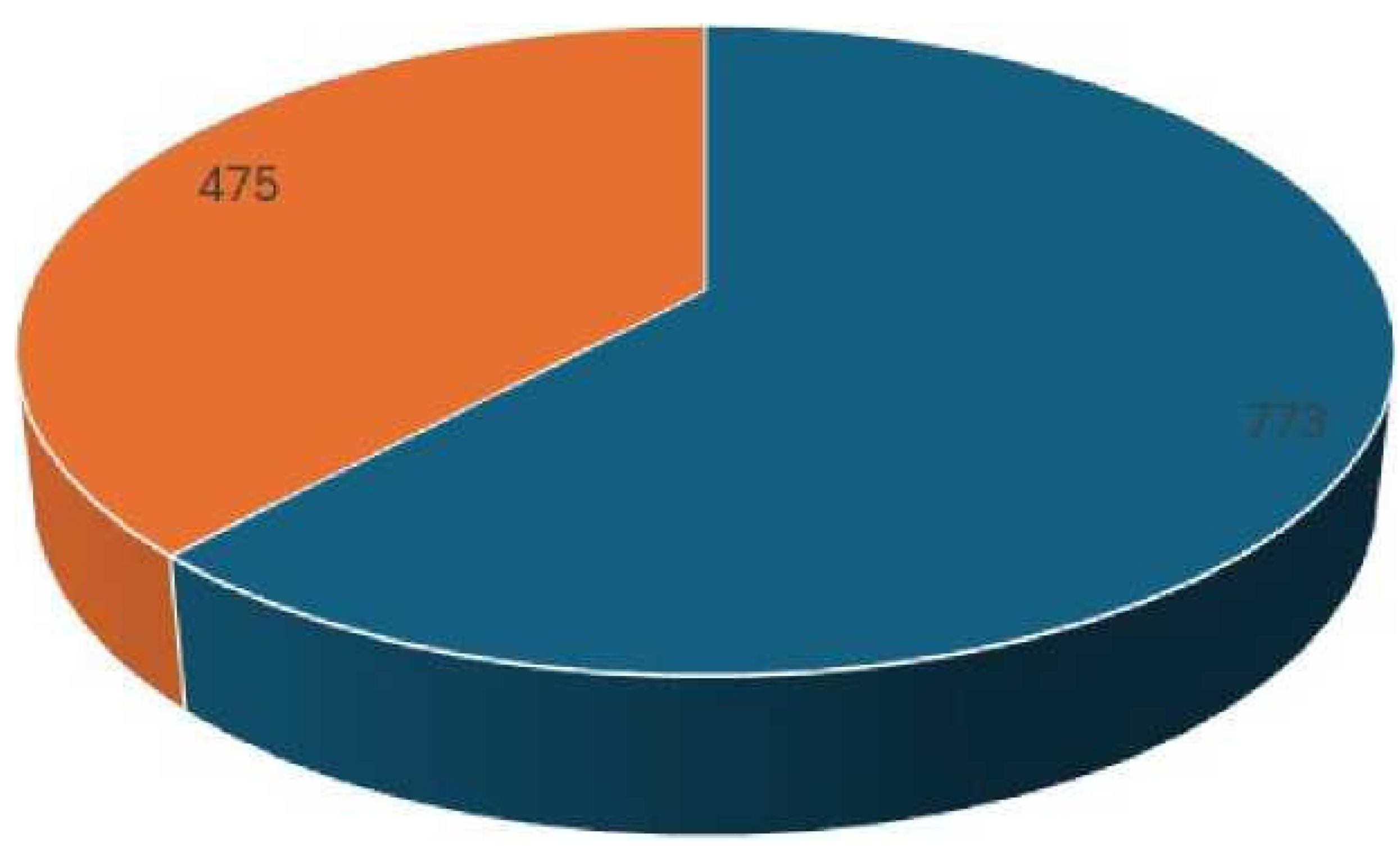

A careful review of these prior studies reveals a gap: while higher education institutions in Western contexts often attempt to balance HOTS and LOTS, institutions in developing countries, including Indonesia, tend to focus more heavily on LOTS-oriented practices. What remains largely unexamined is the

extent to which lecturers’ pedagogical practices in Indonesia reflect a balance between these two domains. Understanding this distribution is crucial for informing lecturers, quality assurance bodies, and university management to adopt more proactive measures that foster HOTS. Therefore, the present study departs from earlier work [

33,

34,

35] by

quantifying Indonesian lecturers’ practices to determine the counterbalance between higher- and lower-order thinking skills.

2. Theoretical Framework

The present study is grounded in the dichotomy between lower-order thinking skills (LOTS) and higher-order thinking skills (HOTS). LOTS emphasize recall, basic comprehension, and procedural application, while HOTS involve analysis, evaluation, and creation. In higher education, these skills should be conceptualized not as isolated categories but as complementary dimensions of cognitive development [

87,

88,

89,

90]. Yet, research across Indonesian universities has shown that LOTS continue to dominate lecturers’ instructional and assessment practices, particularly in test-based evaluations [

121]. This tendency raises concerns about whether lecturers can effectively balance academic demands with the development of students’ critical and creative capacities [

79]. Against this backdrop, the theoretical frameworks of Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy are employed, as they illuminate pedagogical and assessment practices that either foster HOTS or reinforce LOTS [

124]. These perspectives enable a critical analysis of classroom discourse and highlight how lecturers’ choices reflect broader epistemological orientations [

101,

102]. Thus, the use of these frameworks provides a robust conceptual basis for investigating literacy and thinking skills in contemporary higher education [

36,

41,

42].

Academic Literacies theory positions literacy as a complex social practice that involves critical engagement, negotiation of meaning, and knowledge construction [

73]. Within this framework, students are viewed not as passive recipients of information but as active producers of knowledge. Such a perspective aligns with HOTS, which require learners to analyze arguments, evaluate information, and generate novel insights [

57]. Academic Literacies therefore extends beyond technical reading and writing skills to encompass epistemic and reflective competencies [

38,

39]. Recent studies suggest that adopting Academic Literacies practices enhances students’ confidence in handling complex academic texts and tasks [

1,

2,

60]. This shift simultaneously requires lecturers to reconceptualize their role from “knowledge transmitters” to “learning facilitators” [

6,

8,

9,

86]. In practice, Academic Literacies approaches emphasize collaboration, reflective feedback, and authentic assessment. Such principles are consistent with twenty-first-century learning agendas that prioritize creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration [

14,

15,

17,

122]. Consequently, Academic Literacies can be considered a theoretical representation of HOTS within higher education contexts.

By contrast, Traditional Literacy prioritizes mechanical skills of reading, memorization, and transcription [

20,

29]. It is closely aligned with LOTS, emphasizing literal comprehension and reproduction of information [

31,

32,

33]. In universities, this orientation is often evident in lecture-dominated teaching, multiple-choice assessments, and rote-learning assignments [

91]. While such practices may support foundational mastery of content, they constrain opportunities for deeper critical engagement [

34,

35,

36]. An Indonesian study found that over 70% of examination items designed by lecturers were still focused on LOTS rather than HOTS [

35]. This reflects the persistence of literacy practices that privilege reproduction over critical or creative reasoning. Although Traditional Literacy remains useful for establishing basic competencies, it is increasingly insufficient for preparing students to navigate the complexities of the digital and knowledge-driven era [

37]. Recent analyses highlight that reliance on such approaches limits students’ adaptability, problem-solving, and innovation [

78]. Thus, Traditional Literacy is best understood as the theoretical embodiment of LOTS in contemporary higher education.

The divergence between Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy mirrors the pedagogical distinction between deep learning and surface learning [

38]. Deep learning encourages students to construct meaning through reflective, analytical, and critical processes, whereas surface learning restricts them to rote memorization of facts [

39]. Empirical evidence indicates that students exposed to Academic Literacies-oriented pedagogy achieve stronger outcomes in analytical and creative tasks [

40,

41,

42]. Conversely, those in Traditional Literacy environments tend to perform better only in reproduction-based examinations [

37]. These findings underscore the significant influence of lecturers’ pedagogical decisions on students’ cognitive trajectories [

131]. A balanced integration of both approaches may be desirable, equipping students with essential foundational skills while cultivating higher-order reasoning [

13]. The theoretical duality therefore provides a comprehensive lens to interpret lecturers’ practices in Indonesian higher education. At the same time, it invites further inquiry into strategies that facilitate transitions from LOTS to HOTS within university settings.

Within this conceptual framework, the study foregrounds how lecturers in Indonesia negotiate literacy through their teaching and assessment practices. This perspective highlights not only the evaluation of students’ cognitive skills but also the role of classroom discourse in shaping cognitive engagement [

108]. Academic Literacies, aligned with HOTS, are widely acknowledged as promoting independent, reflective, and innovative learners [

43]. Conversely, the entrenched presence of Traditional Literacy underscores a continued reliance on surface learning strategies that restrict student agency [

44,

45]. Addressing this imbalance contributes to global debates on transforming pedagogy towards more student-centered paradigms [

128]. Specifically, the findings emphasize the urgent need to reorient lecturers’ roles in curriculum design and assessment to ensure a more deliberate balance between LOTS and HOTS [

110]. Such efforts would enhance the responsiveness of Indonesian higher education to twenty-first-century demands. Moreover, this theoretical approach enriches the scholarly understanding of how literacy, cognitive skills, and academic achievement intersect. Ultimately, the study argues that advancing Academic Literacies practices is key to strengthening the global competitiveness of higher education systems.

Given the dichotomous nature of the present study—namely, determining lecturers’ concentration on either lower-order or higher-order thinking skills—two theoretical perspectives,

Academic Literacies and

Traditional Literacy [

20,

21,

22,

23], are adopted. Focusing on these theories enables the investigation of

actual and

observable classroom discourse-related practices and assessment practices, while also allowing quantification of these practices to determine the counterbalance between higher- and lower-order thinking skills. While academic literacies promote higher-order thinking skills, traditional literacy is associated with lower-order thinking skills [

48,

49,

50]. These two approaches may further be dichotomised as

deep learning (academic literacies) and

surface learning (traditional literacy). [

24,

25,

34]

Given the dichotomous nature of the present study, which seeks to determine lecturers’ concentration on either lower-order or higher-order thinking skills, this investigation adopts two complementary theoretical perspectives: Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy. Academic Literacies emphasizes the development of students’ higher-order cognitive capacities, including critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and communication [

89,

90]. Traditional Literacy, on the other hand, foregrounds adherence to established norms and conventions within academic discourse, focusing primarily on knowledge reproduction and memorization [

74,

75,

76]. Employing these perspectives allows the study to investigate actual and observable classroom practices, both in instructional discourse and assessment tasks. Through this theoretical lens, lecturers’ practices can be quantified to identify the relative balance between higher- and lower-order thinking skills in higher education classrooms. While Academic Literacies inherently fosters student autonomy and agency, Traditional Literacy often positions students as passive recipients of knowledge [

88,

89]. Deep learning, as conceptualized in Academic Literacies, encourages engagement with complex concepts and promotes problem-solving skills [

98,

99,

100]. Conversely, surface learning under Traditional Literacy emphasizes rote memorization and compliance with rigid academic structures [

18,

19]. Understanding these theoretical underpinnings is crucial to interpreting the variation in lecturers’ pedagogical choices across different disciplines [

113,

114,

115,

116]. Therefore, these frameworks provide both a conceptual and methodological foundation for examining how lecturers prioritize cognitive skills in their teaching and assessment practices.

Academic Literacies situates knowledge as socially constructed and contextually mediated, emphasizing the need for students to negotiate meaning actively within academic communities [

64,

65,

66]. This perspective prioritizes practices that cultivate critical engagement, such as classroom discussions, collaborative projects, and inquiry-based learning [

2,

3,

4]. Lecturers guided by Academic Literacies integrate assessment strategies that reward originality, reflexivity, and analytical rigor [

52,

53,

54]. These practices foster higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) across Bloom’s taxonomy, including application, analysis, evaluation, and creation [

74,

75,

76,

77]. Digital technologies, including collaborative platforms, learning management systems, and online discussion forums, are increasingly leveraged to reinforce these literacies [

114,

115,

116]. Furthermore, this approach encourages students to develop meta-cognitive awareness and the capacity to self-assess their learning [

98,

99,

100]. Academic Literacies also acknowledges disciplinary variation, allowing for contextualized strategies in fields like English, History, and Religion [

111,

112]. By contrast, Traditional Literacy emphasizes structural conformity, knowledge reproduction, and adherence to teacher-led instruction [

88,

89]. Pedagogical practices within this framework often include lectures, rote memorization, and teacher-directed exercises [

18,

19]. Consequently, students’ opportunities for critical inquiry and innovation are constrained under Traditional Literacy models [

74,

75,

76].

The dichotomous application of these frameworks provides a nuanced understanding of the pedagogical spectrum, revealing tensions between deep and surface learning [

2,

3,

4]. Deep learning, associated with Academic Literacies, aligns with contemporary 21st-century skills frameworks, fostering independent and collaborative problem-solving abilities [

114,

115,

116]. Surface learning, as emphasized in Traditional Literacy, ensures foundational knowledge is retained but may not promote critical engagement or creative problem-solving [

98,

99,

100]. Lecturers’ classroom practices reflect these tensions, with some disciplines favoring structured instruction while others embrace discursive and collaborative approaches [

111,

112]. Assessment practices similarly mirror this duality; HOTS-oriented evaluations reward originality and critical reasoning, whereas LOTS-oriented evaluations prioritize knowledge recall and correct reproduction [

74,

75,

76]. The study’s quantification of these practices provides empirical evidence of how disciplinary norms shape the balance between HOTS and LOTS in teaching and assessment [

88,

89]. For example, English and Religion lecturers may integrate discussion-based pedagogies, whereas History lecturers may emphasize chronological accounts and factual accuracy [

2,

3,

4]. These findings align with prior research indicating that disciplinary conventions significantly influence pedagogical choices [

53,

54]. Digital tools may mediate these approaches by enabling greater student agency even in traditionally rigid disciplines [

18,

19]. Overall, this dual-theory lens is critical for interpreting how lecturers’ decisions foster or limit higher-order thinking skill development [

114,

115,

116].

Integration of Academic Literacies into higher education pedagogy enhances students’ capacity for critical reflection, problem-solving, and creativity [

64,

65,

66]. Collaborative group activities, peer assessments, and dialogic classroom structures are hallmarks of this pedagogical orientation [

111,

112]. Lecturers adopting this approach emphasize feedback loops that support iterative learning and improvement [

74,

75,

76]. Furthermore, Academic Literacies recognizes the socio-cultural dimensions of learning, ensuring that students’ diverse experiences and perspectives inform their engagement with disciplinary content [

2,

3,

4]. Conversely, Traditional Literacy reinforces normative compliance and prioritizes efficiency in knowledge transmission [

88,

89]. This model often reduces student agency, limiting opportunities for questioning or co-constructing knowledge [

18,

19]. Surface learning activities such as memorization of definitions, reproduction of notes, and factual recall dominate under Traditional Literacy [

98,

99,

100]. While necessary for foundational knowledge, these practices do not promote higher-order cognitive skills required in the contemporary knowledge economy [

114,

115,

116]. Digital technologies can bridge some gaps by introducing interactive simulations and online assessments, but their use is less prominent in Traditional Literacy frameworks [

74,

75,

76]. Therefore, the contrast between Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy highlights the spectrum of pedagogical orientations and their implications for cognitive skill development [

64,

65,

66].

The theoretical dichotomy also extends to assessment practices, where Academic Literacies encourages evaluative methods aligned with higher-order thinking [

111,

112]. Assessments may include case studies, problem-based tasks, essays, and reflective journals that require critical synthesis and creativity [

2,

3,

4]. Traditional Literacy assessments, however, often emphasize objective tests, multiple-choice questions, and memorization exercises [

18,

19]. Such assessment designs reinforce lower-order thinking skills (LOTS), including knowledge and comprehension [

98,

99,

100]. The alignment between pedagogy and assessment ensures consistency in learning outcomes, as students are assessed on skills emphasized in classroom practices [

74,

75,

76]. Quantitative analysis of these practices allows researchers to measure the extent of HOTS versus LOTS emphasis across disciplines [

88,

89]. This approach helps identify areas where transformative education goals are being met or hindered [

114,

115,

116]. By focusing on observable classroom and assessment practices, the study offers actionable insights for curriculum design and pedagogical reform [

64,

65,

66]. Additionally, integrating digital tools in assessment can further enhance engagement with higher-order skills [

111,

112]. Consequently, the theoretical lens of Academic Literacies versus Traditional Literacy provides a robust framework for evaluating the effectiveness of pedagogical and assessment practices in higher education [

2,

3,

4].

Academic Literacies also foregrounds the role of digital technologies as integral to pedagogical and assessment practices. Lecturers increasingly employ learning management systems, online discussion forums, collaborative software, and multimedia resources to enhance engagement with higher-order thinking skills [

46]. These technologies enable students to participate in group projects, engage in peer feedback, and co-create knowledge across disciplinary boundaries [

74,

75,

76]. Digital literacy thus becomes a critical component of HOTS, complementing critical thinking, communication, and collaboration skills [

98,

99,

100]. Conversely, Traditional Literacy models underutilize digital tools, relying primarily on face-to-face lectures, printed materials, and structured exercises [

18,

19]. The lack of technology integration in these practices limits students’ opportunities to engage in active problem-solving and innovation [

88,

89]. Recent studies have shown that hybrid pedagogical models, combining Academic Literacies with strategic use of digital tools, significantly enhance HOTS development [

47,

48,

49,

50]. However, challenges such as unequal access to ICT resources, large class sizes, and insufficient lecturer training constrain full implementation [

2,

3,

4]. These constraints disproportionately affect students in traditionally rigid disciplines, where surface learning dominates [

74,

75,

76]. Therefore, embedding digital literacies in curriculum design is essential to bridging the gap between pedagogy and assessment for HOTS development [

114,

115,

116]. Furthermore, lecturers must receive ongoing professional development to integrate digital tools effectively in both classroom instruction and assessment practices [

98,

99,

100]. The synergy between technology and Academic Literacies fosters a student-centred learning environment, enhancing engagement and critical inquiry [

64,

65,

66]. By contrast, LOTS-oriented Traditional Literacy practices reinforce hierarchical knowledge transmission, limiting student agency [

18,

19]. Integrating technology in Traditional Literacy contexts can therefore catalyse transformation toward higher-order cognitive skill development [

88,

89]. This integration is particularly critical in STEM and humanities disciplines, where collaborative and inquiry-based approaches are increasingly necessary [

2,

3,

4].

Disciplinary variation plays a crucial role in shaping lecturers’ adoption of Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy frameworks. English and Religion disciplines often display greater flexibility, emphasizing discussion, critical reflection, and evaluative assessment practices that align with HOTS [

111,

112]. Conversely, History and other historically structured disciplines tend to emphasize chronological knowledge and factual recall, reflecting Traditional Literacy’s influence [

74,

75,

76]. This divergence is partly attributable to entrenched epistemological norms within specific disciplines, which dictate acceptable knowledge, methods, and modes of assessment [

114,

115,

116]. Recent empirical studies show that even when lecturers attempt to introduce higher-order tasks in traditionally rigid disciplines, student outcomes often remain constrained due to historical reliance on LOTS-focused pedagogy [

98,

99,

100]. Nonetheless, interventions that integrate discussion, inquiry-based assignments, and collaborative problem-solving have proven effective in overcoming these disciplinary constraints [

2,

3,

4]. Disciplinary norms, therefore, function as both enablers and barriers in lecturers’ ability to promote HOTS [

88,

89]. Quantitative analyses of teaching and assessment practices reveal significant differences in the extent of higher-order thinking emphasis between flexible and rigid disciplines [

64,

65,

66]. Digital technologies can help bridge this gap, offering students interactive simulations and opportunities for independent inquiry even within traditionally rigid disciplinary frameworks [

74,

75,

76]. Furthermore, lecturers’ epistemic beliefs about knowledge construction influence how they implement Academic Literacies or Traditional Literacy approaches [

111,

112]. Understanding these beliefs is essential for professional development initiatives aimed at promoting HOTS [

114,

115,

116]. By aligning pedagogy, assessment, and technology with disciplinary norms, lecturers can foster balanced cognitive skill development [

98,

99,

100]. Consequently, curriculum reforms should incorporate discipline-specific strategies that encourage HOTS while acknowledging historical learning conventions [

2,

3,

4]. This approach ensures students are not limited to surface learning practices in any discipline [

74,

75,

76].

Assessment practices serve as critical mediators of pedagogical intent, shaping the extent to which HOTS or LOTS are cultivated. Academic Literacies encourages assessments that require analysis, evaluation, problem-solving, and creative synthesis, fostering deeper cognitive engagement [

111,

112]. By contrast, Traditional Literacy assessments emphasize memorization, recall, and reproduction, reinforcing surface learning approaches [

18,

19]. Recent research shows that assessment tasks aligned with higher-order outcomes enhance students’ capacity for critical thinking, collaboration, and digital literacy [

2,

3,

4]. Furthermore, lecturers’ assessment choices often reflect their pedagogical orientation and epistemological beliefs, creating consistency between teaching and evaluation [

114,

115,

116]. Discrepancies between instructional practices and assessment tasks can undermine HOTS development, as students tend to focus on meeting assessment expectations [

74,

75,

76]. Integrating authentic assessment, including projects, portfolios, and peer-reviewed assignments, supports the development of 21st-century skills [

98,

99,

100]. Digital platforms can facilitate these assessments through online submission, collaborative workspaces, and real-time feedback mechanisms [

64,

65,

66]. LOTS-focused assessments may persist due to historical curriculum structures, time constraints, and resource limitations [

88,

89]. These systemic constraints highlight the need for institutional support and professional development in designing assessments that encourage HOTS [

111,

112]. Additionally, alignment with national and international competency frameworks can reinforce the adoption of HOTS-oriented assessment practices [

2,

3,

4]. Recent studies emphasize the importance of integrating assessment with learning design to maximize higher-order skill acquisition [

114,

115,

116]. Moreover, reflective assessments and self-evaluation strategies enhance students’ metacognitive awareness and promote autonomous learning [

74,

75,

76]. The role of formative assessment is particularly important in sustaining continuous engagement with complex tasks [

98,

99,

100]. Therefore, understanding the interplay between pedagogy and assessment is central to advancing Academic Literacies in higher education [

64,

65,

66].

Challenges in implementing Academic Literacies are compounded by structural and resource-related constraints. Large class sizes limit opportunities for discussion, collaboration, and personalized feedback, critical for HOTS development [

2,

3,

4]. Insufficient access to technology, including computers, internet, and software, restricts the integration of digital tools in classroom and assessment practices [

74,

75,

76]. Lecturer workload and limited professional development opportunities further impede the consistent application of Academic Literacies [

111,

112]. Conversely, LOTS practices under Traditional Literacy require fewer resources and are easier to implement at scale [

18,

19]. Despite these constraints, innovative pedagogical strategies such as flipped classrooms, peer-led discussions, and online collaborative platforms have been shown to foster HOTS even in resource-limited contexts [

114,

115,

116]. Institutional support, including training, infrastructure investment, and curriculum flexibility, is critical for enabling lecturers to adopt HOTS-oriented practices [

98,

99,

100]. Recent evidence suggests that combining Academic Literacies with digital pedagogical tools significantly enhances student engagement and learning outcomes [

2,

3,

4]. Policy-level interventions are necessary to address systemic barriers that favor LOTS-focused practices [

74,

75,

76]. Furthermore, promoting a culture of innovation and experimentation in teaching can encourage lecturers to adopt more student-centred approaches [

64,

65,

66]. Case studies demonstrate that lecturers who successfully integrate Academic Literacies and technology report increased student criticality, creativity, and collaboration [

111,

112]. The evidence highlights the need for context-sensitive strategies that balance pedagogical ideals with practical realities [

114,

115,

116]. Therefore, advancing HOTS in higher education requires both theoretical commitment and structural facilitation [

98,

99,

100].

Finally, the juxtaposition of Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating teaching and assessment practices. By operationalizing HOTS and LOTS within Bloom’s taxonomy, researchers can quantify lecturers’ emphasis on critical thinking, collaboration, communication, creativity, and digital literacy [

74,

75,

76]. Academic Literacies aligns with deep learning, student agency, and transformative educational goals, while Traditional Literacy emphasizes surface learning, compliance, and knowledge reproduction [

2,

3,

4]. Recent empirical studies confirm that disciplinary, institutional, and resource factors mediate the adoption of these frameworks [

112,

113,

114]. Integrating digital technologies enhances the potential for HOTS development, particularly in collaborative and inquiry-based learning contexts [

98,

99,

100]. Assessment practices must align with pedagogical intentions to ensure consistency in cognitive skill development [

64,

65,

66]. Institutional policies should provide incentives and support for lecturers to implement HOTS-oriented pedagogies and assessments [

74,

75,

76]. Continuous professional development programs are critical for equipping lecturers with skills to design and deliver higher-order learning experiences [

2,

3,

4]. The theoretical dichotomy also informs curriculum design, highlighting the need for balance between foundational knowledge and higher-order skill development [

114,

115,

116]. In conclusion, adopting a dual-framework approach enables a rigorous evaluation of teaching and assessment practices, providing insights for enhancing HOTS in higher education [

98,

99,

100].

What makes the academic literacies perspective particularly useful for addressing higher-order thinking skills is its pluralistic, heterogeneous, multidimensional, and dialogic nature—closely aligned with participatory pedagogy [

51]. Academic literacies is a “dynamic set of multiple literacies” [

52], emphasising multimodality (communication through varied modes) [

53], digital literacy (accessing diverse information through computers), and new literacies for a rapidly changing world [

54]. It also highlights criticality, creativity, and disciplinary norms [

55]. Pedagogical and assessment practices under this approach are heterogeneous, dialogic [

56], and student-centred [

57]. [

12] emphasises that educators should adopt practices that empower learners and harness the creativity multilingual students bring to their acquisition of literacy. This aligns with [

59] notion of rationalist activity in critical literacy.

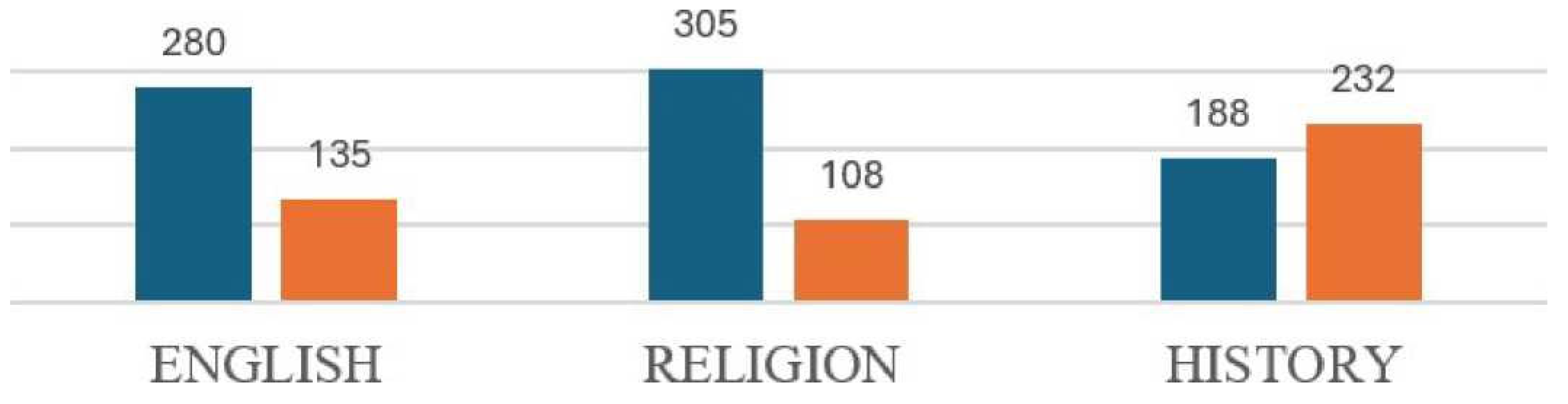

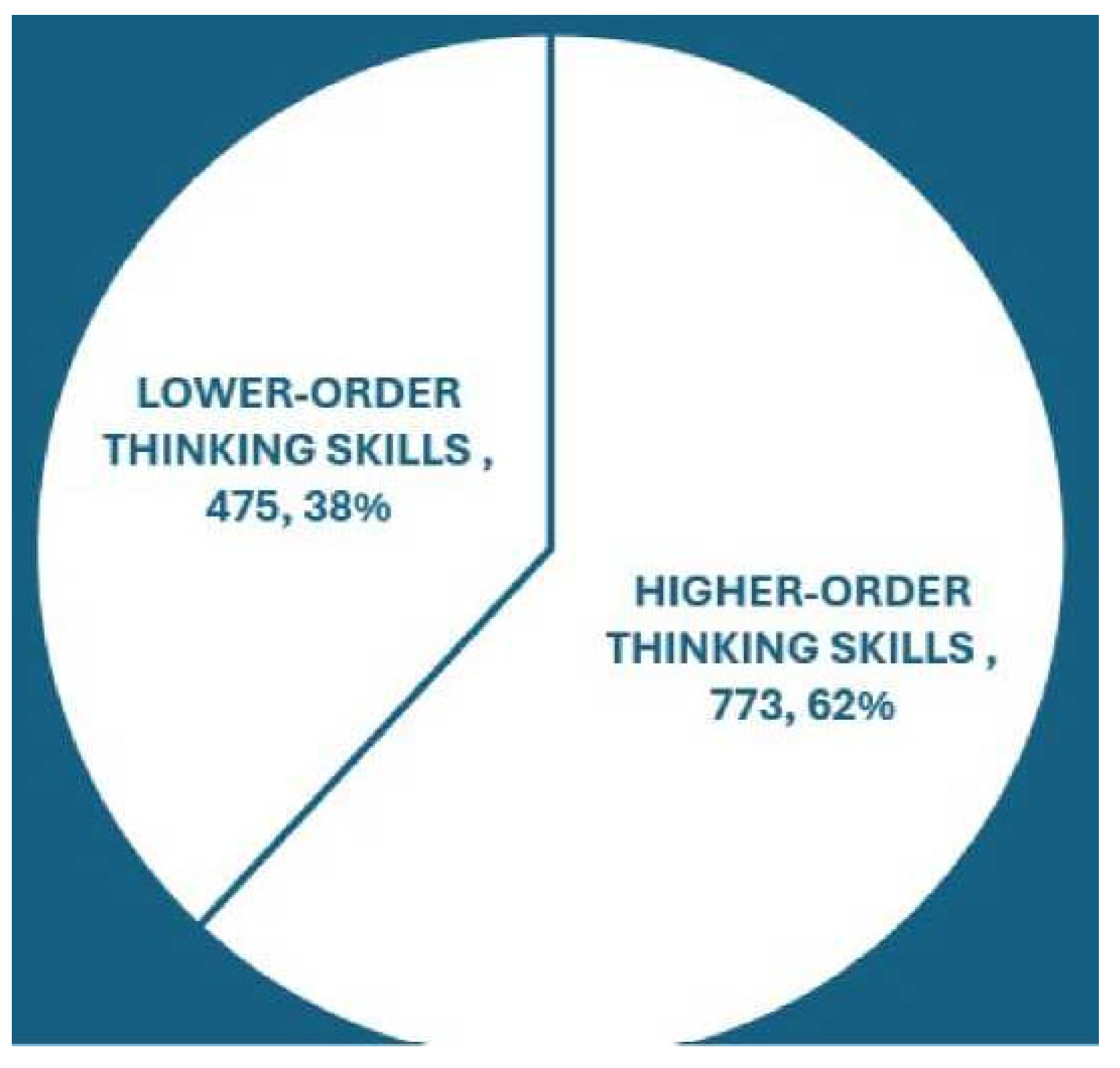

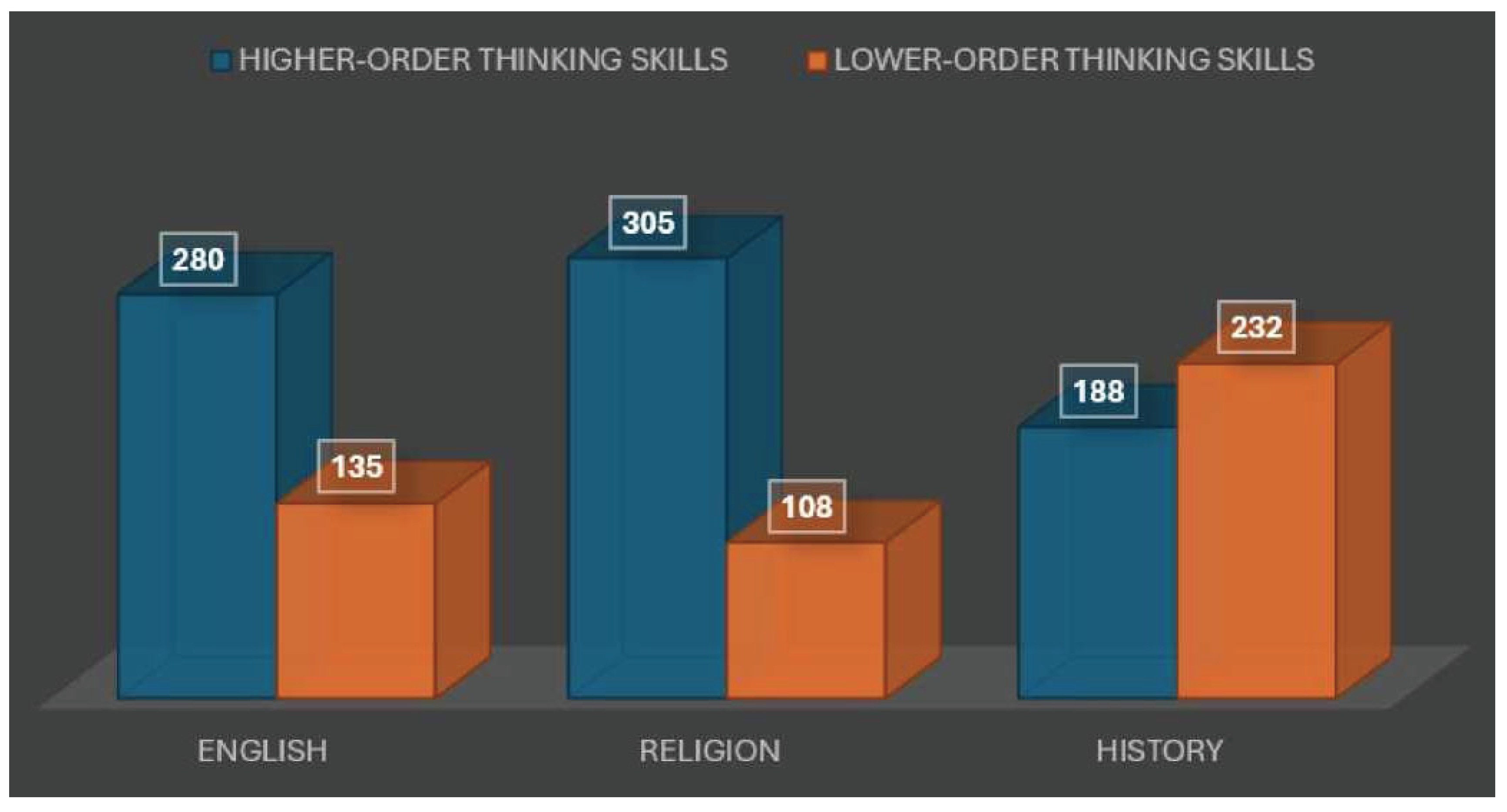

In terms of pedagogy, academic literacies encourage discussion, dialogue, group work, and collaboration; while in assessment, they emphasise originality, voice, academic honesty, and feedback. Digital technologies also play a vital role, as lecturers employ computer-assisted tools such as projectors, laptops, desktops, and Web 2.0 applications (e.g., email, Zoom, and online platforms) . Essentially, these practices foster higher-order thinking skills. Within Bloom’s Taxonomy, HOTS correspond to application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation, and creation. Accordingly, this study conceptualises HOTS as including

critical thinking (analysis, evaluation, creativity),

collaboration (group activities, group presentations),

communication (class participation, presentations), and

digital literacy (use of ICT tools for learning). [

26,

27,

28,

60]

The dichotomous nature of this study, which focuses on lecturers’ concentration on either lower-order thinking skills (LOTS) or higher-order thinking skills (HOTS), requires grounding in theoretical perspectives that capture both surface and deep approaches to learning. Recent research continues to validate Academic Literacies as a framework that emphasizes critical engagement, reflexivity, and dialogic learning, thus aligning closely with the promotion of higher-order thinking [

1]. Conversely, Traditional Literacy has been associated with surface learning, where knowledge reproduction and memorization dominate, thereby reinforcing lower-order skills [

2]. Academic Literacies theory highlights the contextual and socially situated dimensions of learning, stressing that literacy practices are not neutral but are shaped by power, identity, and epistemological orientations [

128]. By contrast, Traditional Literacy is often criticised for maintaining rigid hierarchies of knowledge and privileging textual reproduction over creativity and criticality [

13]. These two orientations thus form a theoretical spectrum against which lecturers’ practices can be assessed. Contemporary scholarship suggests that positioning pedagogy within this dichotomy helps identify whether educational practices nurture transformative learning or merely sustain conventional teaching models [

39]. The adoption of Academic Literacies as a dominant paradigm is viewed as essential in higher education systems that aspire to equip students with 21st-century competencies [

102]. Nevertheless, Traditional Literacy remains prevalent in many contexts due to systemic constraints such as massification, assessment pressures, and limited institutional resources [

35]. The present study situates itself at this intersection to highlight the balance—or imbalance—between these theoretical orientations in practice.

Academic Literacies, as a theory, promotes practices that move beyond the mechanical acquisition of literacy skills to embrace critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. It frames teaching and learning as socially constructed processes that require collaboration, negotiation of meaning, and responsiveness to disciplinary norms [

3,

4]. Within this paradigm, lecturers are encouraged to design pedagogical and assessment practices that foster students’ agency, originality, and capacity for independent thought [

5,

6]. This orientation resonates strongly with the demands of higher-order thinking skills, which prioritize application, analysis, evaluation, and creation rather than simple recall [

78]. Recent empirical studies show that classrooms that adopt Academic Literacies approaches often report higher student engagement, deeper understanding of content, and improved problem-solving competencies [

7,

8]. Moreover, the digital transformation in education has further expanded the scope of Academic Literacies, as it now includes multimodal and digital literacies that integrate technology into learning practices [

39]. By embedding digital tools into instruction and assessment, lecturers create new pathways for fostering critical engagement and creativity [

102]. Thus, Academic Literacies align not only with HOTS but also with broader global educational trends aimed at preparing students for an uncertain, technology-driven world [

13]. At the same time, this theory calls attention to structural inequities, reminding educators that literacy practices are shaped by institutional cultures and must be critically examined [

35]. For this reason, Academic Literacies remain a vital theoretical framework for the present study.

By contrast, Traditional Literacy theory situates learning within a narrower conception of reading and writing, focusing on correctness, adherence to conventions, and reproduction of knowledge. This orientation often emphasizes memorization, grammar, and the mechanical acquisition of skills, leading to the prioritization of lower-order thinking skills in both pedagogy and assessment [

9,

10]. Traditional Literacy has been critiqued for its inability to nurture critical thinking, as it positions students as passive recipients of knowledge rather than active constructors [

11,

12]. Recent studies in higher education have shown that this approach often persists due to exam-driven curricula, overcrowded classrooms, and limited institutional innovation [

13,

14]. While Traditional Literacy may ensure short-term gains in standardized assessments, it fails to prepare students for real-world challenges that demand adaptability, creativity, and criticality [

78]. In the Indonesian context, researchers have noted that the persistence of Traditional Literacy is linked to hierarchical teacher-student relations and the dominance of content-heavy syllabi [

15,

16]. This creates a disconnect between policy aspirations of transformative education and classroom realities where surface learning dominates [

39]. Moreover, in digital learning environments, Traditional Literacy is increasingly insufficient, as students require not just textual proficiency but also digital competencies and critical engagement with multimodal information [

102]. Thus, while Traditional Literacy remains influential, its limitations make it less compatible with the goals of higher education in the 21st century [

13]. Recognizing this dichotomy is crucial for examining lecturers’ practices in the present study.

Framing Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy as corresponding to deep learning and surface learning respectively provides a useful analytical lens for examining classroom and assessment practices. Deep learning, as promoted by Academic Literacies, is characterized by conceptual understanding, critical engagement, and integration of knowledge across contexts [

17,

18]. Surface learning, aligned with Traditional Literacy, is marked by rote memorization, limited transfer of knowledge, and reliance on reproducing information [

19,

20]. Studies in recent years have demonstrated that deep learning strategies are strongly correlated with student outcomes such as problem-solving, adaptability, and creativity [

21,

22]. Conversely, surface learning strategies tend to limit student growth and hinder long-term intellectual development [

23,

24]. The distinction between these learning approaches thus offers insight into the extent to which lecturers’ pedagogical and assessment practices foster transformative education. In Indonesia and other comparable contexts, lecturers often adopt a hybrid approach, reflecting both deep and surface learning tendencies depending on institutional demands [

25,

26]. This hybridity underscores the complexity of classroom realities, where ideals of critical pedagogy meet systemic barriers such as resource scarcity and examination pressures [

35]. The present study, therefore, positions the deep/surface learning dichotomy as central to understanding lecturers’ practices. By quantifying and examining these practices, the research highlights how the balance between HOTS and LOTS reflects broader theoretical orientations. This framework is essential for interpreting the empirical results of the study.

The adoption of Academic Literacies over Traditional Literacy is increasingly seen as a prerequisite for achieving transformative education outcomes in higher education. Transformative education seeks not only to transmit knowledge but also to develop critical, independent, and socially responsible learners [

27,

28]. Lecturers who design pedagogy and assessment with Academic Literacies principles are more likely to produce graduates capable of creative problem-solving and critical engagement with societal challenges [

29,

30]. At the same time, systemic reliance on Traditional Literacy practices risks reinforcing passive learning and undermining efforts to cultivate 21st-century skills [

31]. This theoretical dichotomy is not merely abstract but has concrete implications for teaching and learning practices in Indonesia and beyond [

60]. By situating lecturers’ practices within this framework, the present study contributes to ongoing debates about how higher education can align with global trends while remaining responsive to local contexts [

13]. Moreover, the integration of digital literacy within Academic Literacies highlights the evolving nature of pedagogy in response to technological change [

35,

46,

47]. It suggests that higher education institutions must reconfigure traditional models to remain relevant in the digital age. Ultimately, examining the balance between Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy provides a critical lens through which to evaluate whether higher education is meeting its transformative goals. This study thus underscores the importance of theory in framing and interpreting pedagogical realities in higher education research.

By contrast,

Traditional Literacy is largely concerned with conformity to conventions and norms within discourse communities, requiring students to adhere strictly to rules set by experts [

61,

62,

63]. Students in this model are passive recipients of knowledge, with little scope to question or critique higher education practices [

64,

65,

66]. Traditional Literacy is closely aligned with the autonomous model of literacy, and with behaviourist learning theories that emphasise transmission and reproduction of knowledge. Pedagogical practices under this framework promote lower-order thinking skills, such as rote memorisation, abstract instruction, and teacher-centred methods. Within Bloom’s Taxonomy, these correspond to the knowledge and understanding levels. Thus, in this study, LOTS are defined as practices lacking emphasis on criticality, creativity, collaboration, communication, and digital technology. [

67,

68,

69]

Traditional literacy continues to be framed as a pedagogical approach that prioritises conformity to established rules and conventions, positioning knowledge as something fixed and transmissible from experts to learners. In this view, students are regarded as passive participants who receive information without opportunities for critique or creative engagement. Scholars argue that such an approach reflects the autonomous model of literacy, where the meaning of texts is seen as objective and universal, detached from context [

88,

89]. Traditional literacy practices typically align with behaviourist learning theories, which highlight repetition and reinforcement as primary mechanisms for knowledge acquisition [

98,

99,

100]. Consequently, student roles are narrowly defined, and the scope for exploration or innovation remains limited. Within Bloom’s Taxonomy, this model predominantly nurtures lower-order thinking skills (LOTS), such as recall and comprehension. Recent debates in higher education highlight the limitations of this approach, particularly as it fails to address the critical, communicative, and collaborative demands of the 21st century [

114,

115,

116]. Traditional literacy is also criticised for resisting integration of digital technologies, thereby limiting students’ adaptability to contemporary learning environments [

74,

75,

76]. Despite these critiques, traditional literacy persists in many academic contexts due to its perceived efficiency and clarity of outcomes [

18,

19]. This persistence suggests a continued tension between tradition and innovation in pedagogy.

Pedagogical practices rooted in traditional literacy are characterised by lecture-based delivery, memorisation, and heavy reliance on examinations. Such methods promote surface learning, where students’ main goal is to reproduce information accurately for assessment purposes [

52,

64,

65,

66]. This approach does not encourage questioning, problem-solving, or the development of higher-order skills, which are increasingly emphasised in educational policy frameworks [

69,

70,

71]. Teacher-centred instruction dominates, with little space for student agency in shaping knowledge or classroom discourse. As a result, learners become dependent on authority figures, reinforcing hierarchical relationships in the classroom. Furthermore, assessment within this paradigm tends to measure factual recall rather than conceptual understanding or application [

72,

73,

74]. Critics contend that such practices reproduce social inequities by privileging students already familiar with dominant cultural and linguistic norms [

2,

3,

4]. The rigid focus on standardisation also marginalises alternative literacies and diverse forms of knowledge expression [

114,

115,

116]. Nonetheless, for institutions prioritising uniformity and accountability, traditional literacy remains attractive. It provides clear metrics for evaluation, even though it limits broader learning goals.

A key critique of traditional literacy is its narrow definition of learning success, which is often equated with adherence to pre-established norms and mastery of static content. Under this framework, students are rarely encouraged to develop skills in creativity, criticality, or collaboration [

98,

99,

100]. Instead, emphasis falls on producing correct answers and following rigid academic structures, which aligns closely with behaviourist traditions in education [

53,

54]. Such practices reinforce LOTS, particularly memorisation and comprehension, while neglecting higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation [

18,

19]. The problem with this approach, as recent studies suggest, is that it inadequately prepares students for complex problem-solving in real-world contexts

[

74,

75,

76]. By limiting student participation to mechanical reproduction, traditional literacy restricts opportunities for personal growth and intellectual independence. Moreover, this pedagogy diminishes the potential of assessment as a tool for feedback and development, reducing it instead to a measure of conformity [

88,

89]. The persistence of such approaches demonstrates how deeply ingrained traditional literacy remains in many higher education systems. This also reveals an ongoing struggle between institutional structures designed for efficiency and pedagogical reforms aimed at fostering critical learning [

75,

76,

77]. Ultimately, the alignment of traditional literacy with LOTS underscores its inadequacy for 21st-century higher education.

The integration of digital technologies has further highlighted the limitations of traditional literacy frameworks. As higher education institutions increasingly adopt ICT-based tools for teaching and assessment, traditional models often resist or fail to fully incorporate these innovations [

2,

3,

4]. Students accustomed to interactive platforms and collaborative technologies often find traditional approaches disengaging and restrictive [

74,

75,

76]. For example, lecture-based memorisation is less effective in digital learning environments that require active participation and autonomy [

114,

115,

116]. Research indicates that the absence of digital literacy practices reduces students’ readiness for globalised and digitally mediated workplaces [

18,

19]. Moreover, reliance on standardised examinations as the primary mode of assessment does not translate well into online or blended learning contexts [

64,

65,

66]. The traditional model thus risks creating a disconnect between institutional pedagogy and the realities of professional and civic life. Although some argue that conventional methods provide necessary structure and rigour, the broader consensus is that they fail to foster innovation or adaptability [

98,

99,

100]. This gap underscores the need to rethink literacy practices in light of technological and societal transformations. Without such reconsideration, students remain confined within outdated pedagogical frameworks that inadequately serve future demands [

53,

54].

Despite its shortcomings, traditional literacy continues to hold relevance in particular educational contexts, especially where clarity, control, and predictability are prioritised. Some scholars note that rigid structures can benefit students at the early stages of learning, providing foundational knowledge before engaging with more complex tasks [

114,

115,

116]. In this sense, traditional literacy may function as a preparatory phase, equipping learners with essential baseline skills. However, relying exclusively on this approach limits opportunities for growth beyond LOTS, leaving students ill-equipped for higher-order intellectual challenges [

74,

75,

76]. This tension suggests that rather than discarding traditional literacy entirely, it might be integrated with more dynamic approaches such as academic literacies [

78,

79,

80]. A balanced approach could retain useful elements of structure and clarity while also incorporating collaboration, critical thinking, and digital literacy [

88,

89]. Such hybrid models are increasingly proposed as viable alternatives to overcome the limitations of traditional practices [

53,

54]. Ultimately, the challenge lies in aligning pedagogical frameworks with evolving societal and technological needs without losing sight of foundational learning objectives [

18,

19]. This ongoing negotiation reflects the complexity of educational reform in higher education today. Traditional literacy, therefore, occupies a contested but enduring space in contemporary pedagogy.

To quantify lecturers’ practices, both Academic Literacies and Traditional Literacy are used as analytical frameworks. Additionally, Bloom’s Taxonomy is employed to determine whether lecturers’ practices concentrate on lower or higher levels of learning. [

81] has demonstrated the link between pedagogy (through course objectives in syllabi) and assessment (examination questions) via Bloom’s framework. The revised taxonomy includes six levels: knowledge, understanding, application, analysis, evaluation, and creation. Knowledge and understanding are categorised as “surface learning” [

82], while application, analysis, evaluation, and creation reflect “the use of knowledge” [

83]. In this study, the former is aligned with Traditional Literacy, while the latter is aligned with Academic Literacies. This dichotomy helps identify which lecturers’ practices demand recall of facts (LOTS) and which encourage application and critical engagement (HOTS).