1. Introduction

Augmented Reality (AR) has gained significant attention in education by providing enriched learning experiences that overlay digital information onto the physical environment. In educational contexts, AR activities have been associated with increased engagement, improved conceptual understanding and stronger connections between abstract content and concrete contexts. At the same time, there are significant challenges such as cognitive demands, technological reliability and the adaptation of conventional classroom strategies [

1,

2]. Research shows that AR can facilitate multiple inquiry-based activities, boosting experimentation as well as game-based learning (GBL) in multiple fields. The positive contributions of AR are highlighted, even though its impact varies depending on design quality and alignment with educational goals [

1,

2]

When AR is combined with mobile devices and location-based mechanics (LBM), everyday spaces such as school playgrounds, neighborhoods, streets or heritage-enriched areas can be transformed into meaningful and engaging learning environments. Mobile augmented reality games (MARGs) situate learners as active explorers of their surroundings, engaging them in challenge-based activities, supporting the interpretation of contextualized information and, when explicitly designed for this purpose, fostering collaborative decision-making and negotiation as they move through urban space [

3]. This is particularly important in activities regarding Education for Sustainability (EfS). In these themed activities, learners engage with complex socio-environmental issues. Typically, these problems are linked to contexts or practices rather than limited to classroom settings or educational materials [

4]. Recent studies have investigated AR’s contribution to enhancing environmental literacy and encouraging sustainable behaviors. These studies indicate that immersive experiences can support learners in linking sustainability concepts to their local cultural contexts [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

At the same time, learning analytics (LA) has emerged as an important research and development field that uses digital traces of learner activity to understand and optimize learning processes, products and environments. In the context of GBL, game learning analytics (GLA) research has shown how telemetry data can be used to illustrate patterns of play, to identify misconceptions, to predict learning outcomes and to support iterative improvement of educational games [

11,

12]. Research emphasizes the increasing use of data science and multimodal analytics in gaming, encompassing clustering, sequence mining, predictive modeling, and visual analytics, typically structured within pipelines that convert raw data into meaningful insights for teachers, researchers, and designers [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Recently, LA and educational data mining have increasingly been applied to immersive technologies, such as Virtual Reality (VR), AR, and Mixed Reality [

21,

22,

23]. However, a rapid analysis of recent literature reviews reveals a predominant focus on VR, with reliance on self-report data and limited systematic use of detailed interaction logs [

24,

25]. Research on LA for educational MARGs with school-age learners remains scarce, despite instances of telemetry usage to assess disengagement in augmented classrooms and examine mobile AR applications that enhance various competencies, particularly in Cultural Heritage and GBL [

26,

27,

28]. Current studies indicate that the methodological and design possibilities of LA in mobile AR remain underdeveloped, particularly in urban gaming contexts that require collaborative engagement, such as the case study presented in this work.

Recent research has also examined the application of AR in cultural heritage, highlighting its potential to support the interpretation of historic sites, increase visitor engagement and facilitate exploration through mobile devices [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Several location-based MARGs and applications guide learners through museums and historic areas, embedding multimedia content and interactive activities at Points of Interest (POIs) [

32,

33]. However, evaluations of these systems have mainly relied on self-report questionnaires, basic usage metrics and qualitative feedback, with very limited research that uses the rich data produced during AR-enhanced heritage experiences as a resource for learning analytics. This gap is particularly pronounced in EfS, where recent AR-based studies emphasize attitudinal and motivational outcomes while largely neglecting detailed gameplay data and collective learning trajectories [

7,

8,

10,

34,

35]

Together, these strands reveal a specific gap at the intersection of mobile AR, urban cultural heritage and EfS. While prior work has shown that AR-based heritage experiences and MARGs can foster engagement, environmental literacy and attitudinal change, there is still little evidence on how the fine-grained gameplay logs generated by collaborative groups in real urban settings can be transformed into interpretable learning analytics indicators and used to inform the design of sustainability-oriented educational games.

The present study is situated at the intersection of these strands, focusing on a location-based MARG that integrates urban cultural heritage and sustainability education. The

Art Nouveau Path is a location-based MARG implemented in Aveiro, Portugal, within the EduCITY Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystem (DTLE) (

https://educity.web.ua.pt/, accessed on 10 November 2025). It engages student groups in a collaborative exploration of eight Art Nouveau heritage sites through 36 quiz-based tasks that combine multimodal resources, including AR overlays, archival imagery, video clips and narrative storytelling, to explore the educational value of Aveiro’s Art Nouveau heritage for the development of sustainability competences aligned with the GreenComp framework [

36]. This MARG and its implementation have been developed within the doctoral research project of the first author.

The present study addresses this opportunity by analyzing gameplay logs from 439 students, organized in 118 collaborative groups, who engaged with the Art Nouveau Path during the post-test implementation segment (S2) of a repeated cross-sectional intervention designed to foster the development of sustainability competences. Focusing on the S2 segment (post-game gameplay logs), it proposes and exemplifies a workflow for event-based learning analytics in a location-based mobile AR game and examines how the resulting indicators can be used to identify collaborative gameplay profiles and to inform the design and refinement of AR-mediated learning experiences. To connect behavioral patterns with learners’ own perspectives, the analysis integrates cluster-based profiles of group play with students’ qualitative reflections on collaboration, perceived challenge and perceived learning about sustainability and built heritage, derived from S2-POST group responses.

Building on this context, the study is guided by two research questions (RQ):RQ1. How can raw gameplay logs from a location based mobile augmented reality game be transformed into a structured set of learning analytics indicators that characterize collaborative group performance, pacing, and task-specific difficulty in sustainability education?RQ2. What distinct collaborative gameplay profiles emerge when these learning analytics indicators are analyzed using cluster analysis, and how do these profiles relate to students’ qualitative reflections on collaboration, perceived challenge, and perceived learning about sustainability and urban cultural heritage?

This paper is structured in six sections. Following the Introduction,

Section 2 presents a targeted integrative narrative review organized into three strands: (i) AR and GBL in educational contexts, (ii) LA in GBL and immersive environments, and (iii) mobile AR in cultural heritage and sustainability related contexts, concluding with previous work on the

Art Nouveau Path and the specific contribution of the present study.

Section 3 details the Design-Based Research (DBR) approach [

37,

38], the

Art Nouveau Path MARG and EduCITY DTLE, the participating students and data sources, and the procedures for data processing, indicator construction, error mapping, cluster analysis and integration of gameplay profiles with group reflections.

Section 4 reports empirical findings on the collaborative gameplay performance, item and path level difficulty patterns, the identified three gameplay profiles and their qualitative interpretations.

Section 5 discusses these results in relation to game LA, AR enhanced EfS approach and the design and implementation of heritage-based MARGs. The paper is concluded by summarizing the main contributions, outlining implications, acknowledging the study’s limitations, and presenting future paths.

2. Background and Related Work

This section presents a narrative thematic literature review anchored in recognized methodologies for integrative thematic synthesis [

39,

40,

41]. The review and analysis combined hybrid, inductive and deductive coding to structure the theoretical framework [

42,

43,

44] across three strands: (i) AR and GBL in educational contexts, (ii) LA in game-based and immersive environments, and (iii) mobile AR in cultural heritage and sustainability related contexts. In-depth database searches were conducted in Scopus and Web of Science, enhanced by research in Google Scholar to integrate grey literature and institutional findings. Searches were carried out between September and November 2025 and focused on works published from 2010 onwards. Effective keyword combinations included

augmented reality AND

game-based learning;

learning analytics AND

serious games;

extended reality AND

education;

mobile augmented reality AND

cultural heritage; and

augmented reality AND

environmental OR

sustainability education. As in previous authored works, direct searches using Art Nouveau as a term yielded mostly art historical publications and were therefore excluded unless they explicitly addressed educational design.

Inclusion criteria comprised studies that (1) were peer-reviewed and indexed in Scopus and Web of Science, (2) studied AR, game-based or immersive technologies in educational contexts, and (3) reported evaluative data or learning related outcomes, including learner traces or interaction logs, or addressed cultural heritage and sustainability in ways that informed the present design. Exclusion criteria comprised (1) purely technical or engineering oriented AR and Extended Reality (XR) developments without pedagogical framing, (2) heritage related work with no educational dimension, (3) theoretical reflections lacking empirical, design based or analytical components, and (4) duplicates or records that proved thematically peripheral after full text screening.

The resulting corpus (

Appendix A) brings together systematic and scoping reviews, empirical studies on AR and serious games, work on LA and educational data mining, relevant conference papers, and a framework related to sustainability competences, and previous publications on the

Art Nouveau Path and the EduCITY DTLE. The framework and prior analyzed studies as previous works by the authors on the

Art Nouveau Path ensured continuity with the broader research and DBR approach [

37,

38].

The following subsections examine each strand in turn, beginning with AR and GBL in educational contexts, followed by LA in game-based and immersive environments, and mobile AR in cultural heritage and sustainability-related contexts, and concluding with previous work on the Art Nouveau Path and the specific contribution of the present study.

2.1. AR and GBL in Educational Contexts

Previous works on AR in educational contexts demonstrate that this technology may increase engagement, support conceptual understanding and connect abstract content to real environments, but that its impact depends strongly on careful pedagogical design and curricular integration [

1,

2]. Studies synthesized in these works span Sciences, Mathematics, History and Language learning, and often report positive learner perceptions while also documenting challenges such as cognitive overload, technical breakdowns and difficulty on promoting activities in classroom context.

When AR is embedded in GBL, the potential for learners’ immersion and engagement can be extended. Game mechanics such as quests, timed challenges and rewards are layered onto AR overlays and multimodal content, transforming curricular tasks into interactive missions.

Recent empirical work with AR-based games in Mathematics, for example, has presented positive effects on students’ critical thinking and problem-solving competences when compared to more traditional educational activities, although these gains are not uniform across all learners and tasks [

45]. Research with younger learners using games with AR features has also highlighted the importance of age-appropriate interaction design and the role of narrative, storytelling, and proper-developed feedback in sustaining both curricular value and engagement [

26].

In sustainability related educational activities, AR has been used to situate environmental issues in authentic, real-world and locally grounded contexts, such as within schoolgrounds, local urban or natural environment. Several studies report that AR can foster environmental literacy, promote attitudes towards Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and EfS, particularly when activities are designed to be embodied, inquiry oriented and combined with social interaction [

7,

10]. Experimental studies with AR texts and immersive scenarios have revealed improvements in students’ attitudes towards environmental issues and sustainable development topics, as well as gains in environmental literacy and self-motivation towards these themes [

6,

9]. These works suggest that AR enhanced GBL in educational settings can be a powerful tool towards students’ engagement regarding EfS. Nevertheless, most evaluations still rely on pre- and post-questionnaires and other self-report instruments, paying relatively little attention to the rich process data generated during gameplay, such as detailed gameplay logs.

2.2. LA in Game-Based and Immersive Environments

In education, LA is often defined as the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for the purpose of understanding and optimizing learning and the environments in which it occurs [

46]. Recent works highlight benefits such as supporting teaching practices, institutional monitoring and the early identification of students at risk, while also pointing to persistent challenges around ethics, privacy, data quality and the evaluation of impact in authentic settings [

47,

48].

Within this field, this work aligns with studies that use learner-generated traces not only for prediction or risk detection, but also as a basis for design-oriented reflection on how learning activities occur in situ.

2.2.1. LA in Games and Serious Games

LA in GBL is an emergent area that has developed into a substantial subfield often referred to as GLA. Empirical studies illustrate that researchers have used gaming data to discern patterns of gameplay, conceptualize learning processes and their resultant effects, and guide the iterative development of serious games [

12]. Alonso-Fernández and colleagues [

13] examined the applications of data science techniques to GLA data and distinguished between descriptive, diagnostic, predictive and prescriptive use of gameplay logs, ranging from simple frequency counts to clustering, sequence mining and predictive modelling.

Regarding the value of multimodal and visual analytics, Emerson and colleagues [

11] argue that multimodal LA approaches in combination with gameplay logs data with other indicators such as eye tracking, gesture or physical signals, may be used to better capture the complexity of GBL processes. Alonso-Fernández and colleagues [

14] proposed a GLA pipeline that blends data mining with visual dashboards aiming to provide interpretable indicators for teachers and game designers, illustrating how heatmaps, progression charts and error distributions can guide the refinement of game levels, narrative, and feedback mechanisms.

Other research has highlighted the capacity of LA to improve usability and efficacy within formal educational contexts. Daoudi [

16] presented a study focused on how LA has been used to improve the usability of serious games in educational contexts, identifying the need for tighter integration between analytics, user-centered design and curricular demands. Banihashem and colleagues [

15] synthesized research on LA focused on online GBL. They proposed a framework that organizes metrics into engagement, performance and behavioral categories. Rivera-Uscanga and colleagues [

19] equally researched on LA usage in serious games. Their study highlights the predominance of log-based measures of time on tasks, attempts and scores. They also presented emerging work using clustering and predictive models. Sánchez Castro and colleagues [

20] used GLA from serious games as predictors of students’ linguistic competence and academic performance, while Lu and colleagues [

18] constructed prediction models that operationalize stealth assessment in a game-based learning environment. Calvo-Morata and colleagues [

49] stated that LA can guide the development of a programming themed serious game by revealing players’ difficulties, which strategies they adopt to overcome those difficulties, and how game-design processes have direct impact on progression patterns.

Within these works, a unifying concept involves the design of pipelines that transform unrefined gameplay logs into performance-related metrics, strategic approaches, engagement levels, and challenge assessments. These indicators can then be used for evaluation and game design, but also to undertake research. At the same time, work on LA has motivated improvements in learning design, but the field remains relatively immature, with limited evidence that analytics pipelines consistently inform or enhance instructional design in systematic ways [

50]. This emphasizes the need for contextually aware workflows that link gameplay logs to comprehensible indicators that are readily applicable by teachers and designers.

2.2.2. LA in Extended Realities (XR) and AR

Recent studies on this topic have begun to explore LA and educational data mining in XR environments, including VR, AR and, more recently, metaverse platforms.

Lampropoulos and Evangelidis [

24] conducted a review, content analysis and bibliometric study of LA and educational data mining in XR and reported that most of the empirical work focuses on VR, with relatively fewer studies examining AR based-learning experiences. These authors also reported that many XR studies rely predominantly on self-report data collection tools, with limited use of fine-grained interaction logs and advanced analytics techniques. Sakr and Abdullah [

25] similarly reviewed research on VR and AR in education from a learning analytics perspective, highlighting the predominance of small-scale studies, the lack of longitudinal designs and the need for more transparent reporting of analytics workflows.

From a location-based perspective, Fonseca and colleagues [

51] present a systematic review of 50 empirical studies on Location-Based Augmented Reality (LBAR) in education that confirms these trends. This study reports that most of the interventions relied on descriptive statistics and self-reported instruments regarding motivation, engagement or perceived learning, with only a minority implementing control-group designs or standardized performance-based assessments. It was also reported that very few implementations exploited detailed interaction logs or multimodal traces as part of an explicit analytics pipeline.

Singh and colleagues [

28] proposed an AR analytical framework, which harnesses interaction data to recognize and tackle disengagement during the education of young children, demonstrating the role of in situ analytics in guiding educators’ decisions. More recently, Abdul Razak and colleagues [

26] researched LA for children through the implementation of augmented reality gaming. This analysis explored the ways these target-aged learners explore AR designs, assessing their performance data and engagement metrics. Cheng [

27] analyzed LA derived from a mobile AR app designed to enhance cultural competence in higher education, combining log data with performance and self-report measures to understand how students engaged with AR mediated cultural content.

These works illustrate that AR-enriched educational experiences can produce intricate interaction data that are amenable to the analysis of learning processes. At the same time, they underline that work in this area is still relatively scarce, particularly in school contexts and in games that unfold in complex physical environments such as cities. Systematic reviews of XR and LBAR research converge in pointing to methodological limitations, including short interventions, lack of control conditions and an overreliance on questionnaires, along with a relative absence of transparent, replicable analytics workflows operating on event level interaction data. Despite the growing number of studies in this area, there is still a need for research that examines analytical methods for AR data and produces reproducible methodologies suited to the specific features of mobile, collaborative AR games.

2.3. Mobile AR, Cultural Heritage and Sustainability Related Contexts

AR has been widely explored in cultural heritage as a possibility to enhance interaction and learning about historic sites and artefacts. Recent work has extended these approaches into AR, namely MARGs and playful experiences. Xu and colleagues [

32] presented

HeritageSite AR, a mobile exploration game for a Chinese heritage site that combines AR overlays, navigation and puzzles to support visitor engagement, and evaluated its usability and perceived educational value. Capecchi and colleagues [

33] designed an AR-based serious game to engage the so-called alpha generation [

52] with urban cultural heritage, showing that mobile AR mechanics can attract young audiences to heritage sites and stimulate discussion about place identity and history.

Chatsiopoulou and Michailidis [

29] reviewed AR applications in cultural heritage and synthesized design, development and evaluation approaches, identifying recurrent patterns such as overlaying historical reconstructions onto ruins, providing in situ storytelling and offering interactive tours through mobile devices.

These related projects illustrate how mobile AR can turn heritage districts into real game boards and narrative spaces, where learners navigate between POIs, access multimodal content and perform situated tasks.

Research conducted by Fonseca and colleagues [

51] lends further support to these conceptions from the perspective of LBAR. This study reveals that cultural heritage and history represent among the most prevalent application domains for LBAR in education, along with environmental science and ecology. A considerable proportion of implementations are performed as field trips, non-compulsory outdoor activities, or informal visits. These are frequently enhanced by mobile AR tours or games that encourage learners to traverse between real-world locations while accessing context-specific information and tasks.

A growing number of recent studies have used AR in environmental and sustainability education. Ladykova and colleagues [

7] conducted a comprehensive review of AR within environmental education and discovered that many interventions report enhancements in environmental cognition and attitudes, frequently through experiential activities conducted in natural settings or laboratory environments that integrate AR content with authentic ecosystems. Simon and colleagues’ research [

10] executed a scoping review of AR in environmental education, underscoring opportunities for embodied learning and local pertinence, while advocating for more stringent methodological designs and a broader spectrum of evaluative techniques. Experimental studies have shown that AR experiences can augment environmental literacy, intrinsic motivation, and intentions towards sustainable conduct [

6,

9], and that VR and AR scenarios can facilitate reflection on green energy and sustainability-related behavioral alterations [

8] or enhance environmental consciousness among wider audiences [

5].

In sum, across both cultural heritage and environmental education, the dominant evaluation methods remain questionnaires, pre- and post-tests, interviews and observations, sometimes complemented by simple usage metrics such as time spent or number of AR triggers activated. Very few studies consider the detailed structure of AR mediated tasks, the sequence of actions taken by learners in urban heritage routes or the distribution of errors across different types of content and locations as a source of learning analytics. While Cheng [

27] offers an example of how mobile AR can be combined with learning analytics to examine cultural competence in higher education, there is still a lack of research that integrates mobile AR, built heritage, sustainability competences and event-based LA derived from gameplay logs in educational contexts.

2.4. Previous Work on the Art Nouveau Path and Contribution of the Present Study

The

Art Nouveau Path has already been analyzed in several works that addressed complementary facets of its design and educational impact. One line of work focused on the pedagogical design of the game within the EduCITY DTLE, its alignment with the GreenComp framework [

36] and its validation with teachers, showing how mobile AR and built heritage can be combined to foster sustainability competences in school contexts [

53,

54]. These studies reported the DBR process [

37,

38], the simulation-based workshop with in-service teachers and the subsequent curricular review, emphasizing the perceived pedagogical value and curricular relevance of the game.

A second line of work examined students’ sustainability conceptions and their relationship with urban heritage before playing the game and over time. Using a longitudinal, repeated cross-sectional design with adapted GCQuest sustainability questionnaires (S1-PRE, S2-POST and S3-FU) with open ended prompts at three moments (pre-, post-, and follow-up, respectively), this research documented how situated, multimodal experiences with the

Art Nouveau Path may support changes in how students describe Sustainability, attribute value to the Art Nouveau district and articulate links between built heritage and broader socio-environmental issues [

54,

55].

More recently, gameplay data from the

Art Nouveau Path have also been treated as geoinformation. This study analyzed the physical path itself, and spatial narrative structures emerging from the 118 group sessions, combining gameplay logs, post-game reflections and teachers’ observations (T2-OBS) to explore how students move through and make sense of the Art Nouveau district as a learning landscape [

54,

55]. This work highlighted the potential of mobile AR to generate semantically enriched movement data and to support narrative cartography in urban heritage education.

These works contribute to the study of AR in EfS designed-activities, DTLE, and heritage-based learning by empirical demonstrating that a MARG, when properly designed, may support curricular integration, promote sustainability related reflection and generate meaningful spatial storytelling data. Methodologically, however, these works have relied primarily on teachers and students’ questionnaires with open-ended responses, pre- and post-comparisons and high-level gameplay indicators such as total scores, completion rates and aggregate accuracy. The more fine-grained gameplay logs, which record group level responses to each of the 36 quiz-type tasks, including correctness, AR specific scoring and completion status across the eight POIs, have not yet been systematically analyzed from a LA perspective.

The present study aims to address this gap and to contribute to both GLA and AR-based sustainability educational activities in three main ways. First, it proposes and exemplifies a workflow for transforming raw gameplay logs from a location-based MARG into a structured set of LA indicators that characterize collaborative group performance, pacing and task specific difficulty. Second, it applies cluster analysis to these indicators to identify distinct collaborative gameplay profiles and to describe how groups differ in their engagement with AR-mediated tasks, temporal dynamics and error patterns. Third, it connects these profiles with students’ qualitative reflections on collaboration, challenge and learning about sustainability and built heritage, illustrating how event-based LA may be interpreted together with self-reported experiences. In sum, this study aims to contribute to calls for more systematic and context-sensitive use of interaction data in AR learning environments. Furthermore, this study extends previous work on the Art Nouveau Path by underscoring the learning analytics potential of its gameplay logs.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Educational Context

This study is part of a broader DBR approach [

37,

38] centered on the

Art Nouveau Path, a location-based MARG implemented in Aveiro, Portugal, within the EduCITY DTLE. The overall research design follows a quasi-longitudinal, repeated cross-sectional structure that combines design, enactment and iterative refinement of the intervention in authentic educational contexts [

53,

54]. The data collection instruments and sources are presented in

Table 1.

Across the wider project, three student questionnaire moments were implemented: a baseline prior to gameplay (S1-PRE, N = 221), an immediate post-game questionnaire (S2-POST, N = 439) and a follow-up questionnaire several weeks later (S3-FU, N = 434). These instruments focus on students’ sustainability conceptions, values and perceptions of the game and have been analyzed in detail in previous works [

53,

54]. Teacher validation questionnaires (T1-VAL, N = 30) and interviews with expert teachers (T1-R, N = 3), together with in-field teacher observations during gameplay (T2-OBS, N = 24), complement this student-focused data within the broader research design [

53,

54].

This study focuses specifically on the post-test implementation segment in which the

Art Nouveau Path was played in the field (S2) and on the group-level gameplay logs generated by the EduCITY app (version 1.3) during these sessions. These logs have previously been used to characterize item difficulty and spatial trajectories in an analysis of geoinformation and spatial storytelling, and to explore the relationship between AR exposure and time on task [

55]. Here, they are reanalyzed from a learning analytics perspective, with different research questions and methodological emphasis that focus on the construction of indicators and the identification of collaborative gameplay profiles. In addition, a subset of individual-level written reflections collected immediately after gameplay through selected S2-POST open-ended prompts is used to complement and interpret the profile structure [

54].

During the S2 implementation considered in this study, 439 students, aged 13-18, were distributed across 19 classes from 6 different grades (7th: N = 19; 8th: N = 135; 9th: N = 156; 10th: N = 37; 11th: N = 20; 12th: N = 72), from urban and peri-urban schools, participated in the Art Nouveau Path activity. Students were organized by their teachers into collaborative groups that typically comprised three or four members, resulting in 118 groups playing the game in the field. Each group used a single shared EduCITY owned mobile device, with the EduCITY app (version 1.3) and MARG installed, and gameplay unfolded during regular lesson around the main Art Nouveau district of Aveiro. The use of single mobile devices per group aimed to foster collaboration, reflecting realistic device availability and the same MARG experimentation. Classroom teachers accompanied the groups, handled logistics and ensured that the activity was aligned with curricular goals related to sustainability, urban space and cultural heritage.

Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all teachers, and from students with supplementary parental or legal guardians’ authorization. No personally identifiable data was collected. Socio-economic background and gender data were not collected, since the study focused on group-level gameplay patterns rather than comparisons between demographic subgroups, and sought to keep data collection as unobtrusive as possible. This decision is consistent with research questioning the explanatory power of specific demographic variables in similar contexts [

56], although it limits the examination of group-specific variation.

3.2. The Art Nouveau Path MARG and the EduCITY DTLE

The

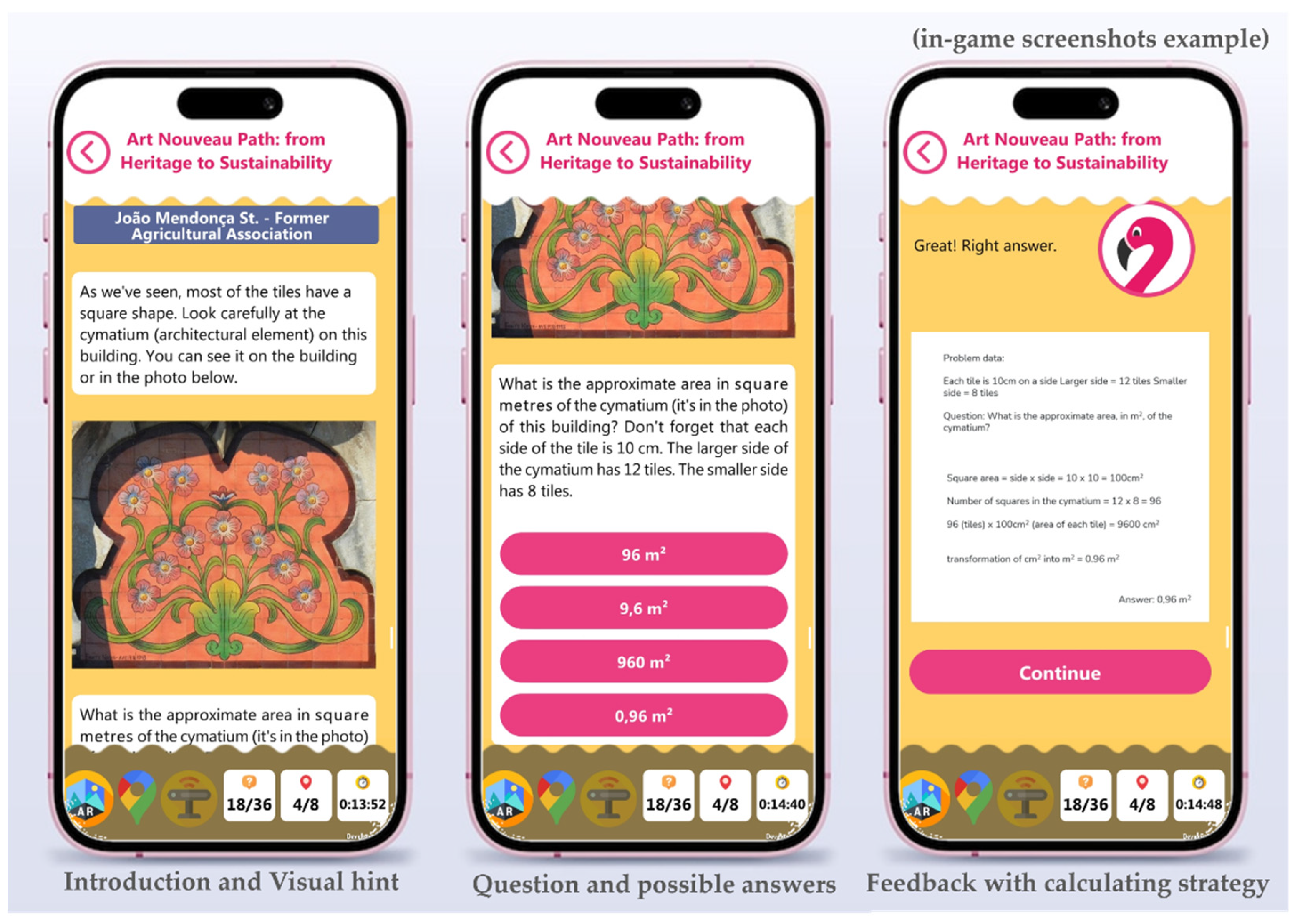

Art Nouveau Path is a MARG embedded in the EduCITY DTLE and played through the EduCITY app (version 1.3). This MARG is designed as a circular path that connects eight georeferenced POIs in Aveiro’s Art Nouveau district. At each POI, participants encounter quiz-like tasks that are anchored in architectural details, historical narratives and sustainability themes, and that are delivered through AR content and multimodal media. In total, this MARG comprises 36 quiz items, internally coded from P1.1 to P8.2. These items draw on a range of resources, including archival photographs, AR overlays anchored to facades, short videos and on-site visual observation, as presented in

Table 2.

Overall,

Table 2 shows that the 36 quiz items are unevenly distributed across Points of Interest and media types, with AR-mediated tasks concentrated at POIs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 and particularly numerous at POIs 5 and 6. Most POIs combine at least two different media.

Tasks prompt students to notice specific architectural elements, to distinguish original from altered features, to connect decorative motifs to local fauna and flora and traditional crafts, and to reflect on tensions between conservation and modernization in the city. The design aligns these tasks with dimensions of the GreenComp sustainability competence framework [

36], such as valuing sustainability, embracing complexity and acting for sustainability, while also addressing school curriculum content [

53,

54].

This MARG’s narrative was designed to be place-based and collaborative. Students navigated the path using the map view in the EduCITY app (version 1.3), which presented the circular path and the eight POIs. The mobile device camera was used to detect AR markers and trigger the AR overlay content when participants were prompted to reveal overlays or to align markers with real facades or architectural details. For each item, the group selected one of several alternatives and submitted ithe response via the app. Correct responses yielded points, and AR-mediated items contributed to an AR-specific score that summarized the group’s interaction with AR-based tasks, as described in previous work on trajectory analysis and AR exposure [

3]. In the present study this AR-specific score is treated as one of the key LA indicators.

3.3. Data Sources for LA

3.3.1. Automated Gameplay Logs

The primary data source for this study consists of anonymized group-level gameplay logs generated automatically by the EduCITY app (version 1.3) during each session of the Art Nouveau Path. In the 1.3 version of the EduCITY app, the logging system records, for each group and session, the date, start and end timestamps, total score, AR-specific score, number of correct and incorrect responses and the duration of the session in minutes. At the item level, it records the completion status for each of the 36 quiz items (P1.1 to P8.2), item-level correctness and, when a response is incorrect, the specific distractor chosen by the group. Logs are stored at the device (group) level only and do not include usernames, demographic information or individual identifiers. The temporal resolution of the logs is adequate to compute session-level duration and to reconstruct which items were completed but does not allow precise estimation of dwell time at each POI. Data was recorded at each mobile device due to the absence of SIM cards or mobile data. The data was subsequently synchronized securely to a dedicated server at the University of Aveiro. This practice guaranteed data integrity and mitigated connectivity problems during field operations.

After excluding non-data rows used for summary statistics in the raw file, the log dataset comprises 118 group sessions. For each group, there is a record of responses to up to 36 items. In the cleaned analytical dataset used in previous publications, each of the 36 items has 118 recorded responses, yielding a total of 4,248 group-item interactions, of which 3 625 are correct and 623 incorrect, corresponding to an overall accuracy of 85.33 percent (%) [

3]. The same underlying logs are now used to derive learning analytics indicators that characterize collaborative performance, pacing and task-specific difficulty at group level.

3.3.2. Group-Level Gameplay and Individual Post-Game Reflections

To complement behavioral traces with learners’ own accounts, the study also draws on individual responses to selected open-ended questions from the immediate post-game questionnaire (S2-POST), which are subsequently considered at group level. At the end of the Art Nouveau Path implementation, each participant was invited to answer the post-game questionnaire, which had a brief set of open prompts that asked, for example, what they felt they had learned about sustainability and urban heritage, which tasks or moments they found most challenging, how they collaborated as a group and how the AR features influenced their experience.

Whereas previous work has subjected S2-POST open responses to full reflexive thematic analysis with a GreenComp-oriented codebook [

36,

54], this study uses these written reflections in a more targeted way. Individual reflections that can be reliably associated with the groups represented in the logs are linked to the corresponding group-level gameplay records and to cluster membership in the gameplay profiles. These reflections are then used to interpret and illustrate the collaborative gameplay profiles identified through cluster analysis. The aim is not to recode the full dataset, but rather to connect quantitatively derived profiles with how participants described their collaboration, perceived challenge and perceived learning.

3.4. Data Processing and Feature Engineering

Data processing integrated the automated gameplay logs and the individual-level reflections and proceeded in four main stages: data were initially cleaned and preprocessed in Microsoft Excel, then analyzed and visualized in R (version 4.4.1), using the tidyverse ecosystem (including readxl, dplyr and ggplot2) and base stats functions. Cross-checks were performed using an additional analytics environment.

First, a data cleaning stage addressed basic integrity issues in the logs. Session records were reviewed for missing or inconsistent values, such as cases where start or end timestamps were absent or where item completion statuses were clearly incompatible with the recorded number of responses. Non-data rows corresponding to pre-calculated means and counts were removed, as were obvious duplicate entries. Although no groups were affected by documented technical failures, such as app crashes, students and teachers were asked to report this. This was cross validated with gameplay logs.

Second, event-level log entries were transformed into group-level indicators that summarize performance and behavior across the session. For each group, the following baseline indicators were computed, building on previous analyses of the same dataset [

3]: 1) Total number of items completed out of 36; 2) Overall accuracy, defined as the proportion of correctly answered items; 3) Mean accuracy per POI, obtained by aggregating correctness across items within each of the eight POI; 4) Mean accuracy by media type, distinguishing between AR-mediated items, video-based items, direct-observation items and photograph-based items, as in earlier work; and, 5) Session duration in minutes, computed as the difference between end and start timestamps.

In addition, an AR-exposure indicator, the AR-score, was operationalized for each group following the procedures reported in Appendix C of a previous authored work [

55]. At the session level, the logs store an AR-specific score that summarizes interaction with AR-mediated items. Data is treated as a continuous LA feature that characterizes how extensively each group engaged with the subset of 11 AR items, with a theoretical maximum of 55 points. Earlier analyses used this score primarily to define high and low AR-exposure groups and to model associations with exploration time [

55]. In this work, this data is incorporated directly into the construction of collaborative gameplay profiles.

Third, error mapping indicators were derived at item and category levels. For each one of the 36 items, the proportion of incorrect responses was calculated, yielding an item difficulty index that complements the accuracy measures. Items previously identified as particularly challenging in terms of conceptual load or contextual complexity in earlier path analysis work on the same dataset, such as those that demand interpretation of dense facades or abstract sustainability concepts, were used to construct a composite indicator of performance on demanding tasks [

55]. Specifically, the demanding items subset comprised the six tasks with the lowest accuracy in the dataset, namely P5.4 (58.47%), P6.4 (67.80%), P2.1 (69.49%), P4.4 (69.49%), P1.5 (72.03%) and P6.5 (72.88%). Items were also grouped by media type and by POI, allowing the computation of error rates for categories such as AR-mediated items in dense streetscapes or non-AR items focused on more abstract sustainability concepts.

Fourth, a subset of these group-level indicators was selected as inputs for cluster analysis and standardized to have mean zero and unit variance. This subset included overall accuracy, the AR score, accuracy on the subset of more demanding items, mean accuracy in AR-mediated items compared to non-AR items and a simple pacing index defined as the ratio between the number of completed items and the session duration. Standardization ensured that indicators measured on different scales, such as percentages, scores and times, contributed comparably to the distance metrics used in the clustering procedure. Indicators with negligible variance, such as the share of completed items given that all groups completed the 36 tasks, and highly collinear indicators were inspected and, where necessary, omitted to improve stability and interpretability of the clusters.

3.5. Analytical Procedures

3.5.1. Descriptive Analytics and Error Mapping

To address the first RQ, the study began with descriptive LA of the gameplay logs. Distributions of overall accuracy, AR scores, session durations and completion rates were examined across the 118 groups. Accuracy and error rates were summarized by media type and by POI, and item difficulty indices were used to identify tasks that posed challenges. These summaries extend, based on a LA perspective, the earlier descriptive statistics reported for the same dataset by connecting them explicitly to performance, pacing and task difficulty indicators relevant for educational design [

55].

Visualizations such as bar charts and heatmaps were used to map error distributions across items and POI and to compare performance patterns between AR-mediated and non-AR items. This descriptive layer established an overview of how collaborative groups performed along the path and where difficulties tended to concentrate, providing the empirical basis for the construction and interpretation of collaborative gameplay profiles.

3.5.2. Cluster Analysis and Collaborative Gameplay Profiles

To address the second RQ, cluster analysis technique was used to identify the possibility of existence of different collaborative gameplay profiles based on the standardized group-level indicators described above. These different profiles were perceived by the researcher during the Art Nouveau Path implementation sessions. An exploratory hierarchical clustering analysis, using Ward linkage and Euclidean distance, was first calculated to inspect the structure of the data and to obtain an initial sense of how many clusters might be substantively meaningful. Dendrograms and changes in within-cluster variance were examined to identify plausible solutions.

Building on this process, k-means clustering was then applied for a range of candidate cluster numbers. The final number of clusters was defined by combining statistical criteria, such as the elbow method and average silhouette width, with considerations of pedagogical interpretability, cluster size, and by cross-checking with in situ researcher fieldnotes. The aim was to obtain a solution in which clusters differed in coherent ways along key indicators such as overall accuracy, AR score, performance on demanding items and pacing, while avoiding clusters with very few groups.

Once the clustering solution was fixed, each cluster was characterized by its mean values and distributions for all learning analytics indicators. These comparative profiles were then used to propose descriptive labels for the clusters, for example highlighting groups that combined high AR exposure with high accuracy, groups that progressed quickly but with more errors or groups that completed fewer items but performed strongly on conceptually difficult tasks. This analysis moves beyond single indicators to capture patterns of co-occurring behaviors that define collaborative gameplay styles.

3.5.3. Integration of Gameplay Profiles and Individual Reflections

In a final analytic step, cluster membership was linked to the subset of individual post-game reflections as previously described. This ensured that the cluster membership was reliably associated with the groups represented in the logs. For each cluster, responses from students in groups assigned to that cluster were examined to identify recurrent ways in which they described their collaboration, perceived challenges and perceived learning about sustainability and urban heritage. This qualitative reading was conducted in a focused, interpretive manner and aimed to illuminate how the behavioral patterns captured by gameplay indicators were experienced and narrated by participants within each collaborative group.

Illustrative excerpts were selected for each cluster to exemplify typical or contrasting perspectives, with particular attention to comments about the role of augmented reality, the negotiation of answers, attention to architectural details and connections to sustainability concepts. The qualitative material was not used to modify the clusters, but rather to enrich their interpretation and to provide a more holistic understanding of how different collaborative gameplay profiles relate to students’ sense-making during the mobile AR experience.

Figure 1 summarizes the learning analytics pipeline described in this section, from raw gameplay logs to derived indicators and collaborative gameplay profiles.

The visual scheme summarizes the event-based LA workflow used in this study. Raw group level gameplay logs from the Art Nouveau Path (step 1) are cleaned and transformed into session and item level indicators (step 2), including accuracy, AR specific scores, pacing and error rates by Point of Interest and media type. These indicators were then aggregated and standardized (step 3) to support descriptive analytics and cluster analysis (step 4), which yields collaborative gameplay profiles. Finally, the profiles are interpreted in connection with group level post-game reflections and teacher observations (step 5), linking quantitative patterns to students’ and teachers’ perceptions.

4. Results

4.1. Overall Patterns of Collaborative Gameplay Performance

Across this MARG implementation, 439 students played the Art Nouveau Path in 118 collaborative groups, generating a total of 4,248 group item responses to the 36 quiz tasks of thus MARG (118 groups multiplied by 36 items). Out of the total, 3 625 responses were correct and 623 incorrect, corresponding to an overall accuracy of 85.33%. On average, groups answered slightly more than 30 out of 36 items correctly, with individual group accuracy ranging from 41.67% to 100% and a median of 88.89%. This indicates that most groups were able to complete the path with relatively high levels of success, while a smaller subset struggled with a substantial proportion of items.

The sessions duration ranged from 26 to 55 minutes, with a mean of 42.38 minutes (SD = 6.20). Given that each session included orientation and short transitions between heritage POIs, this duration suggests that most groups engaged with the MARG for almost the entire session, and that relatively few groups either rushed through the tasks or were unable to complete the path within the allocated time. A pacing-index, defined as the number of items answered per minute, had a mean of 0.87 items per minute, with values ranging from 0.65 to 1.38 items per minute. Overall, groups tended to answer slightly fewer than one item per minute, which is consistent with an exploratory learning activity rather than a rapid quiz like interaction.

The AR specific score, which summarizes performance on the subset of AR-mediated items, ranged from 15 to the maximum of 55 points, with a mean of 46.99 points (SD = 8.60). Many groups achieved values close to the upper end of the AR score scale, while a smaller number of groups accumulated substantially lower AR scores. This distribution indicates that most groups did not avoid AR-mediated tasks and that they tended to answer them correctly, although there is also evidence of variation in how extensively and successfully groups engaged with AR content.

Table 3 summarizes the main group level learning analytics indicators derived from the gameplay logs and used in the subsequent analyses.

The indicators in

Table 3 show a pattern of generally successful but heterogeneous collaborative gameplay. Overall accuracy is high and relatively concentrated (M = 85.33%, SD = 13.53), yet performance on the six demanding items is markedly lower and more dispersed (M = 68.36%, SD = 29.02, range 0–100%), indicating that a small subset of conceptually dense or contextually complex tasks concentrates much of the difficulty and differentiates groups more strongly. The pacing index also exhibits moderate variability (M = 0.87 items per minute, SD = 0.13), suggesting that some groups progressed notably faster or slower than the average even though all groups completed the 36 items. The AR-specific score is skewed towards the upper end of the scale (median = 50 out of 55) but still shows substantial spread (SD = 8.60, min = 15), pointing to meaningful differences in how extensively and successfully groups engaged with AR-mediated items. These patterns justify the subsequent use of multivariate clustering to capture joint variations in accuracy, pacing and AR engagement across collaborative groups.

4.2. Item and Path Level Difficulty Patterns

To analyze how more demanding tasks were distributed along the

Art Nouveau Path, group level responses were disaggregated by POI and by item, using the item-mapping previously summarized and presented in

Table 2. When accuracy is examined at the level of the eight heritage POIs, clear path specific patterns emerge. Mean accuracy per POI remained high throughout the path, with values between 79.38% and 90.68%. Performance was strongest around the third and eighth POIs, where mean accuracies reached 90.68% and 90.25% respectively, and slightly weaker around the fifth and sixth POIs, where mean accuracy was 82.34% and 79.38%. Overall, the path did not contain any segment that systematically overwhelmed groups, but some sections appear to concentrate on more demanding tasks that require more careful observation or abstraction.

At the item level, error mapping shows that difficulties were not evenly distributed. The six most demanding items, defined as those with the lowest accuracies in the dataset and grouped in the demanding items subset introduced in

Section 3.4, yielded accuracy between 58.47% and 72.88%. These tasks include, for example, questions that ask students to infer advantages of reusing heritage buildings, to identify which plant species are not represented in a dense Art Nouveau facade, to compare archival and contemporary photographs in order to detect urban transformations, to estimate the approximate area of a decorative architectural element (

Figure 2), to recall the year in which a major flood inundated the city center and to distinguish between photographs with and without an Art Nouveau aesthetic.

These demands combine spatial reasoning, interpretation of visual detail and the mobilization of contextual knowledge about sustainability and urban change, which may help explain their relatively lower accuracy, as presented in

Table 4.

Table 4 shows that the six most demanding items operate in a medium difficulty range, with accuracy values between 58.47% and 72.88%. The most challenging task, P5.4, which asks participants to infer advantages of reusing an Art Nouveau building, was answered correctly by 69 out of 118 groups (58.47%), meaning that almost half of the groups struggled with this inference. The remaining demanding items also attracted a substantial number of incorrect responses, with around one third of groups answering P6.4, P2.1, P4.4, P1.5 and P6.5 incorrectly. These tasks present several POIs and focus on higher order processes such as visual comparison of archival and contemporary photographs [

57], estimation of decorative tiled-areas, identification of absent elements in dense facades and distinction between subtle aesthetic features, indicating that conceptual and perceptual complexity, rather than mere factual recall, is a key source of difficulty.

By contrast, items that required more straightforward recognition of architectural elements or direct retrieval of information explicitly highlighted by AR overlays and multimedia resources tended to show very high levels of accuracy, often above 95%. This suggests that the MARG effectively scaffolds noticing and recalling when cues are explicit, whereas items that require extrapolation, estimation or the integration of multiple sources of information remain more challenging. Importantly, even the most demanding items were solved correctly by a substantial proportion of groups, which indicates that they operate more as productive challenges than as barriers to engagement.

At the level of the complete sample, mean accuracy on AR-mediated items was slightly lower than on non-AR items, but the difference was modest. This pattern suggests that AR does not simply make tasks easier or harder in itself. Instead, AR tends to support performance when it is used to foreground relevant features of the built environment or to make invisible processes visible, while performance drops in AR items that also integrate more complex reasoning about sustainability, spatial relationships or aesthetic criteria.

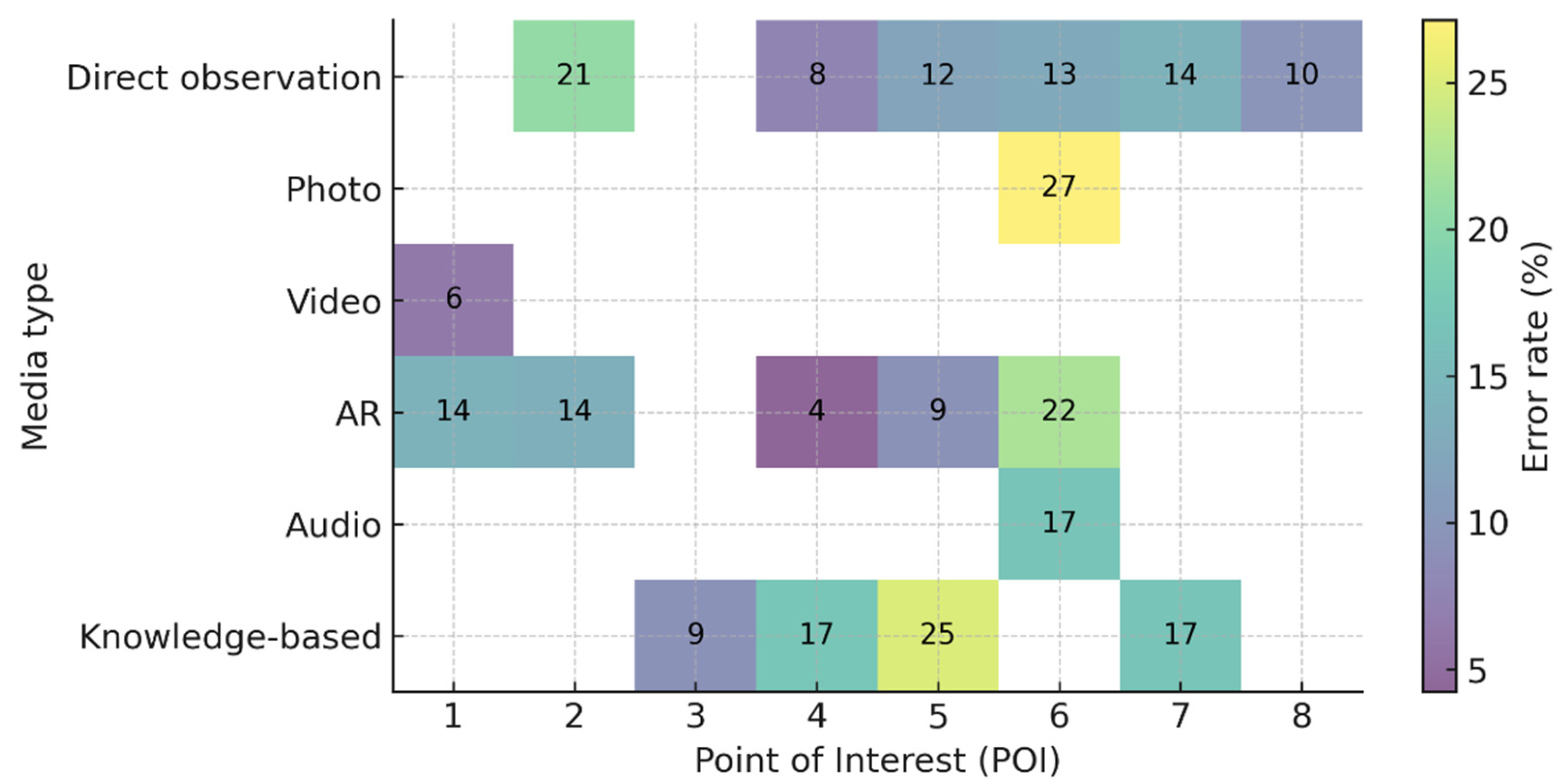

To make these difficulty patterns more visible,

Figure 3 maps error rates by POI and media category. Each cell represents the percentage of incorrect responses for all items of a given media type at a given POI, highlighting local spikes for conceptually demanding questions and AR mediated tasks that require fine grained noticing in complex facades.

The heatmap displays the proportion of incorrect responses for each combination of media type and POI, aggregating across the 36 quiz-type items. Darker cells indicate higher error rates. The figure highlights that errors tend to concentrate in categories that include conceptually demanding items, particularly AR mediated tasks that require multi step reasoning with dense visual information or the integration of archival and contemporary views, while most recognition-oriented item groups show very low error rates.

Together, these descriptive LA address the first RQ by showing that the Art Nouveau Path produces stable patterns of collaborative performance, that difficulties cluster around a small subset of conceptually demanding tasks and path segments and that AR-mediated items are not uniformly easier or harder than non-AR items. This provides a basis for the more synthetic analysis of gameplay profiles presented in the following subsection.

4.3. Collaborative Gameplay Profiles Derived from Learning Analytics

To address the second RQ, cluster analysis was carried out on a set of group level LA indicators, including overall accuracy, accuracy on the subset of demanding items, the AR specific score, pacing and session duration. All indicators were standardized, and a three-cluster solution was retained as a balance between statistical fitting and interpretability.

The resulting profiles differ systematically in both performance and engagement with AR content and are summarized in

Table 5.

As presented in

Table 5, the ‘fast but fragile’ profile consists of 34 groups (28.81% of the sample), demonstrating a mean overall accuracy of 70.83% and a mean accuracy of 37.25% on challenging items. This profile recorded a mean AR-score of 39.41 points, with session durations averaging 36.53 minutes and a maximum of 55 points. The pacing index was the highest among all profiles, averaging 1.00 items per minute, indicating rapid task completion often compromising accuracy, especially on difficult items. Thus, this cluster is characterized as a ‘fast but fragile’ collaborative gameplay profile.

The ‘slow but moderate’ profile comprises 29 groups (24.58% of the sample) and presents an intermediate pattern. Groups in this cluster attained a mean overall accuracy of 84.20% and a mean accuracy of 62.07% on demanding items. This cluster’s mean AR score was 45.69 points, and its sessions were the longest, averaging 50.31 minutes in duration. The pacing index was the lowest at 0.72 items per minute, suggesting a slow advancement through tasks. This profile is characterized as slow but moderate, reflecting significant time investment and reasonable engagement with AR content, albeit without achieving exceptional performance levels.

The ‘thorough and successful’ profile is the largest, comprising 55 groups (46.61% of the sample), exhibiting a high performance and engagement pattern. Groups in this cluster achieved a mean overall accuracy of 94.90% and a mean accuracy of 90.91% on the most demanding items. The average score in the AR category for this cluster reached 52.36 points, nearing the cap, and the mean duration of sessions was 41.82 minutes. The pacing index is set at a moderate 0.87 items each minute, which is beneath the quick but delicate profile, while it is above the slow but moderate profile. Groups in this cluster appear to have adopted a balanced approach, progressing at a measured pace that enabled them to answer nearly all items accurately, including complex tasks, while effectively utilizing AR. Hence, this cluster can be interpreted as a thorough and successful collaborative gameplay profile.

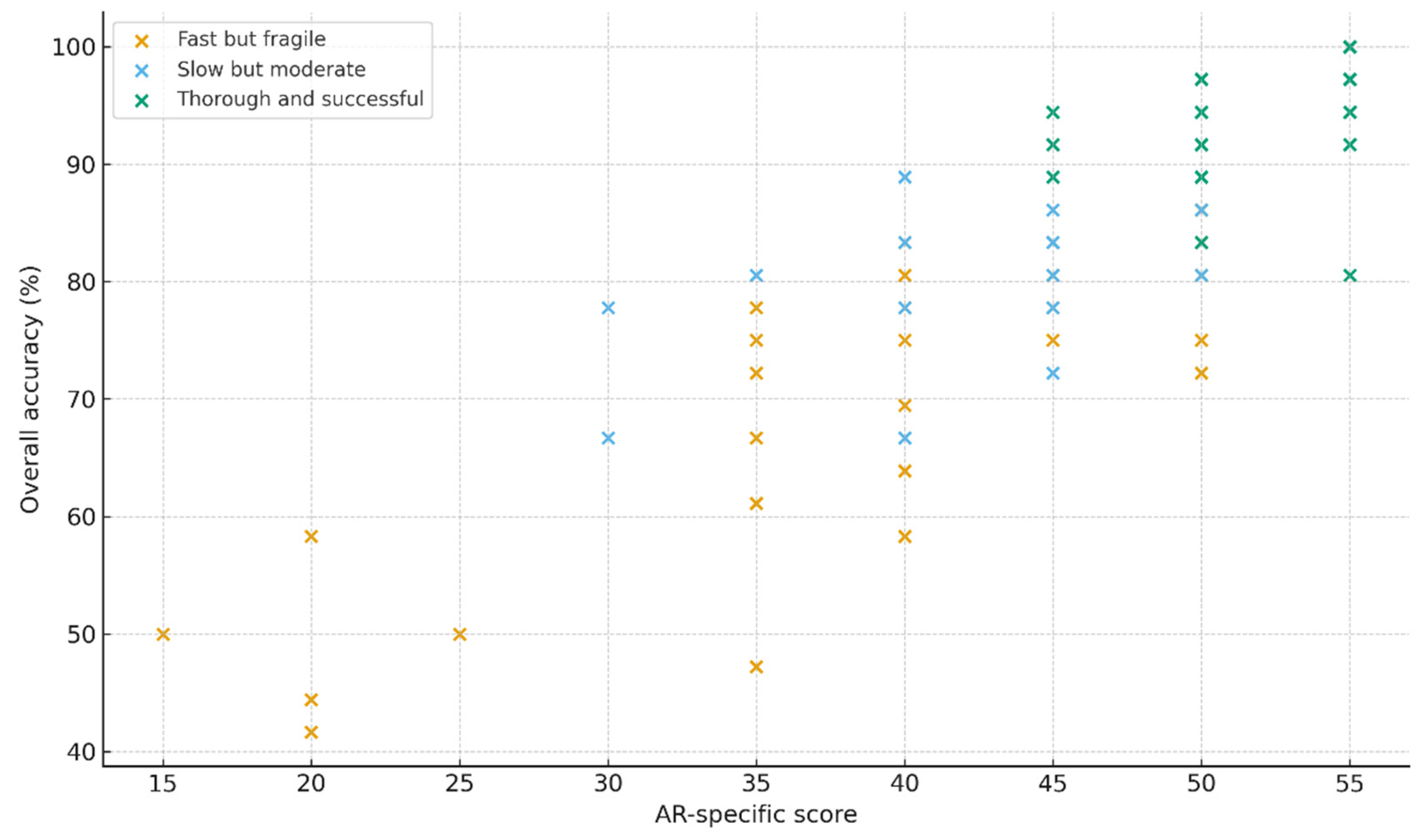

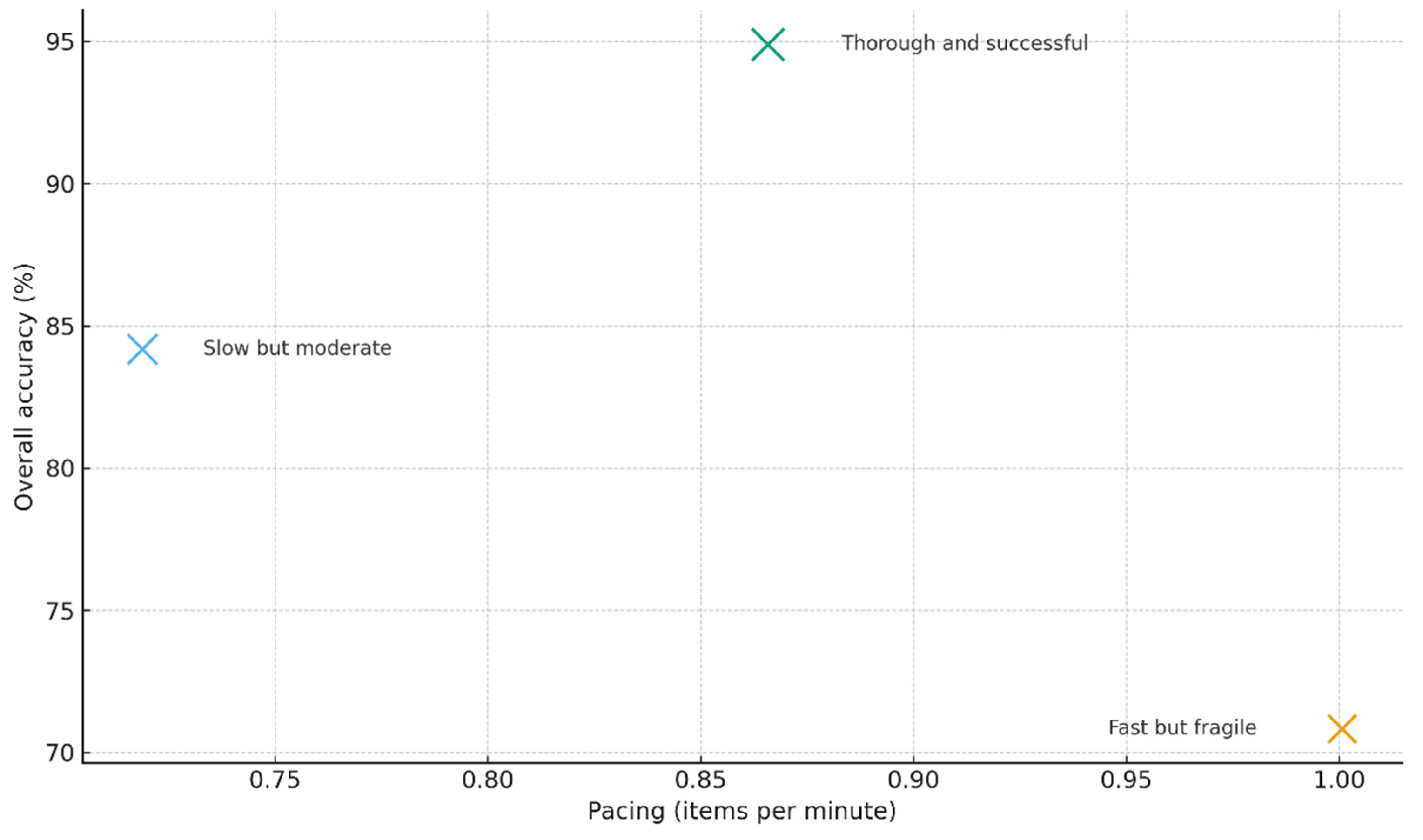

Figure 4 visually locates the three collaborative gameplay profiles in the joint space of overall accuracy and AR-specific score. ‘Fast but fragile’ groups cluster in the lower left region, combining lower accuracy with lower AR scores. ‘Slow but moderate’ groups occupy an intermediate band, with moderate accuracy and AR scores but longer session durations. ‘Thorough and successful’ groups concentrate in the upper right region, combining high accuracy with high AR scores. This pattern indicates that extensive engagement with AR mediated items is associated with higher performance, but only when supported by appropriate collaborative strategies and pacing.

Each marker position may represent one or more of the 118 collaborative groups, ranked by accuracy and AR-specific scores. Overlapping markers signify groups with equivalent scores. Colors represent three identified the three collaborative gameplay profiles: ‘fast but fragile’, ‘slow but moderate’, and ‘thorough and successful’. ‘Fast but fragile’ groups are found in the lower left quadrant, characterized by low accuracy and AR scores. The groups that are identified as ‘slow but moderate’ occupy an intermediary zone, showcasing moderate levels of performance and engagement with AR. ‘Thorough and successful’ groups are concentrated at the upper right quadrant, indicated by their substantial accuracy and engagement with AR-mediated items.

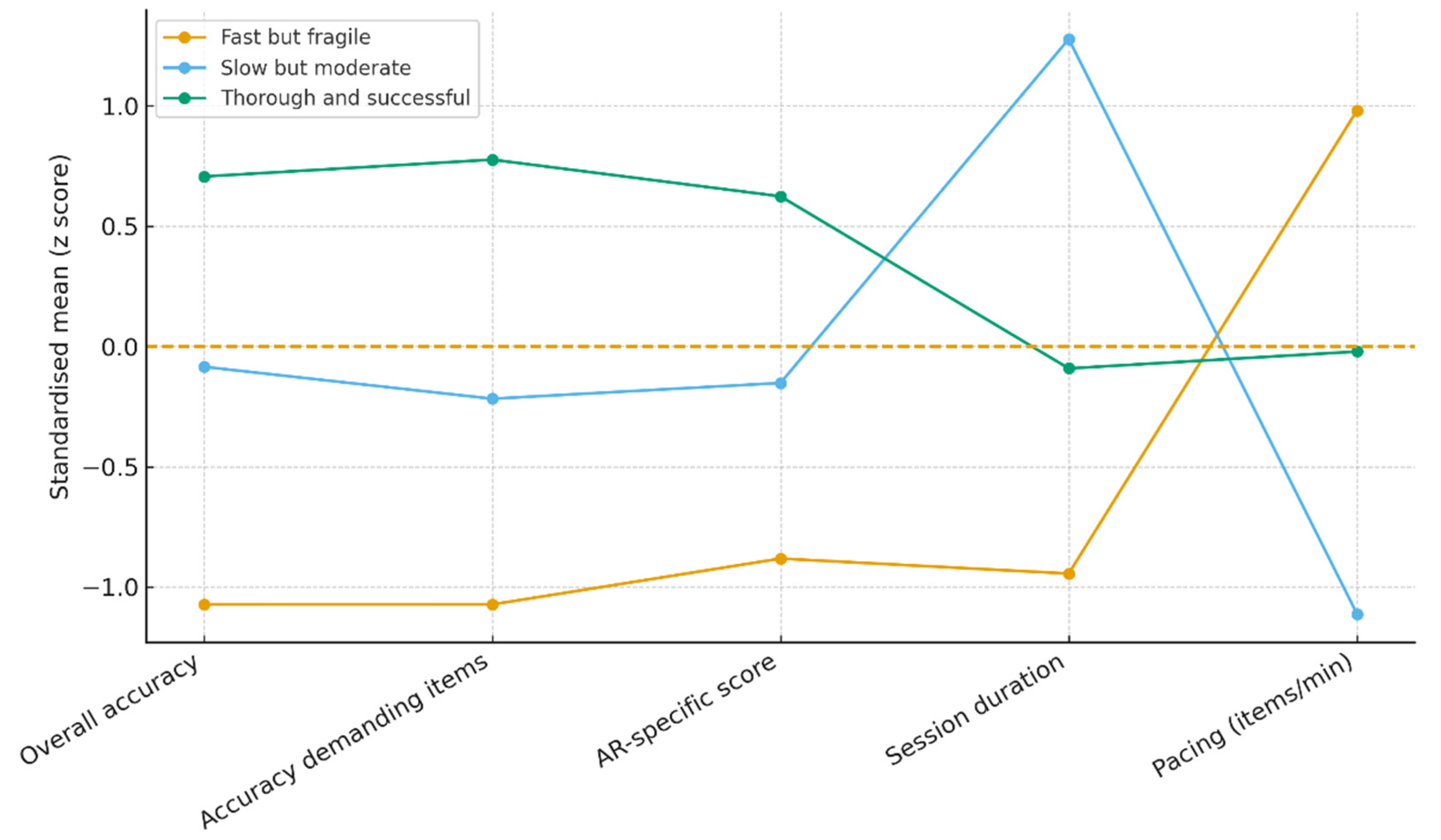

Figure 5 provides a complementary view by displaying standardized means for each LA indicator across the three profiles. The ‘fast but fragile’ profile scores clearly below the overall mean on both accuracy indicators and on AR score and above the mean on pacing, reflecting a tendency to sacrifice accuracy for speed. The ‘slow but moderate’ profile scores moderately above the mean on accuracy and AR score but well above the mean on duration and below the mean on pacing, suggesting a slower but not maximally effective use of time. The ‘thorough and successful’ profile scores clearly above the mean on all performance indicators and around the mean on duration and pacing, which is consistent with an efficient but not rushed pattern of collaborative engagement.

Figure 5 shows, for each collaborative gameplay profile, the mean values of the main learning analytics indicators expressed as standardized scores (z-scores, with mean 0 and standard deviation 1). Indicators include overall accuracy, accuracy on the subset of demanding items, AR specific score, session duration and pacing (items per minute). ‘Fast but fragile’ groups score below the overall mean on both accuracy indicators and on AR score, but above the mean on pacing, reflecting a tendency to prioritize speed over accuracy. ‘Slow but moderate’ groups show intermediate accuracy and AR scores, combined with long durations and low pacing. ‘Thorough and successful’ groups score clearly above the mean on both accuracy indicators and AR score, with intermediate values for duration and pacing, indicating an efficient but not rushed pattern of collaborative engagement.

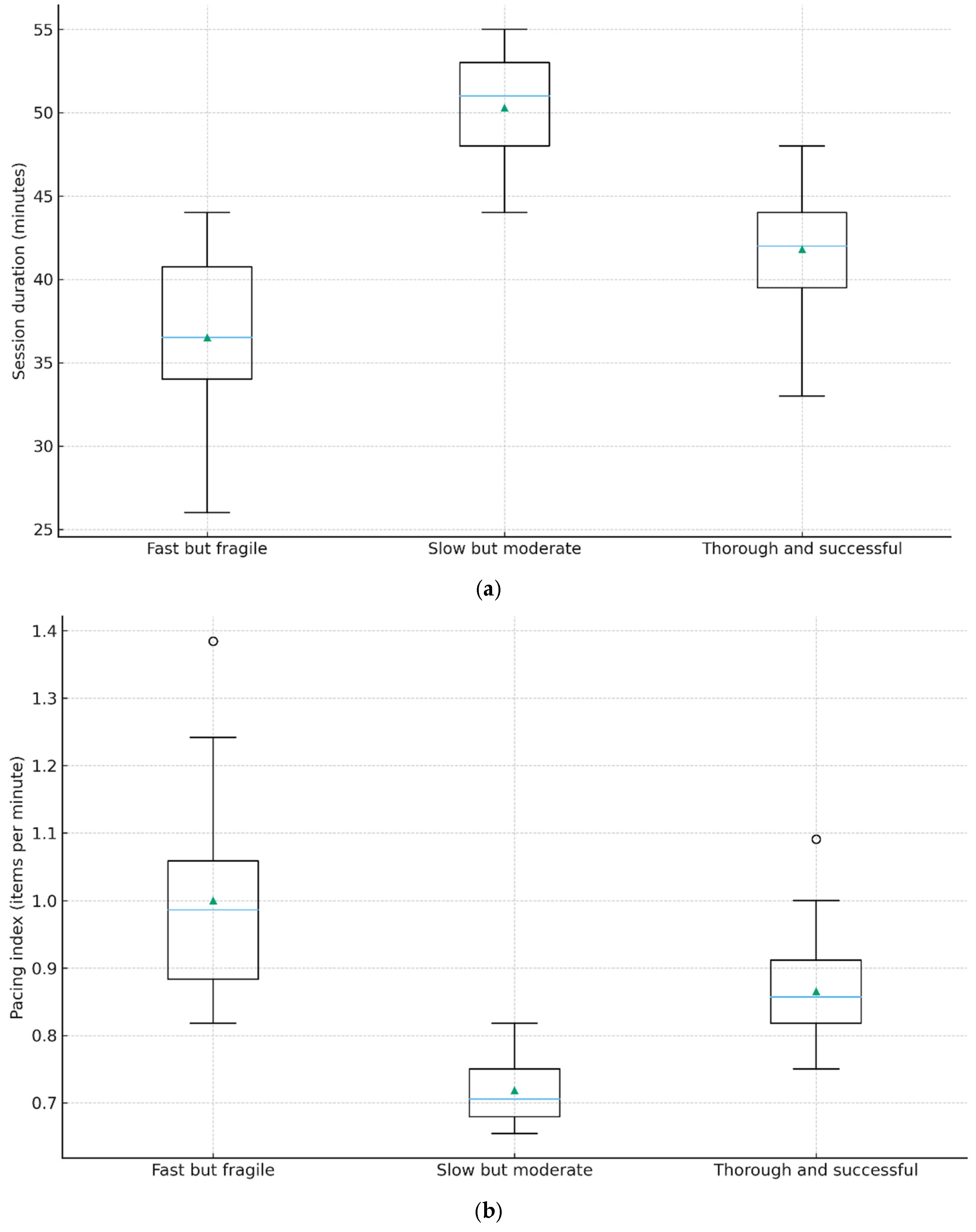

Both

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b compare the distributions of session duration (

Figure 6a—first) and pacing (

Figure 6b—second) across the three collaborative gameplay profiles. ‘Fast but fragile’ groups show relatively short sessions with higher variability in pacing. ‘Slow but moderate’ groups show the longest sessions and the lowest pacing, with values tightly clustered. ‘Thorough and successful’ groups cluster around intermediate durations with moderately high pacing. These differences reinforce the interpretation that the three profiles do not simply reflect different levels of ability, but rather distinct ways in which groups orchestrate time, AR interaction and task solving during the mobile AR experience.

Figure 6a shows boxplots of session duration in minutes for each profile, and

Figure 6b shows boxplots of the pacing index, defined as the number of items answered per minute. ‘Fast but fragile’ groups tend to have shorter sessions and higher pacing, reflecting rapid progression through the route. ‘Slow but moderate’ groups display the longest sessions and the lowest pacing, indicating extended time on task without matching gains in performance. ‘Thorough and successful’ groups cluster around intermediate durations with moderately high pacing, consistent with a balanced strategy that allows for careful collaboration while maintaining steady progress.

These three profiles address the second RQ by showing that the same MARG and heritage-contextualized path can give rise to qualitatively distinct patterns of collaborative engagement. The profiles differ not only in overall success but also in how groups trade off speed against accuracy, how they respond to more demanding items and how fully they engage with AR mediated tasks. Importantly, the presence of a sizeable high-performance profile indicates that, under favorable conditions, students can leverage the Art Nouveau Path to work collaboratively with complex sustainability related content in an urban setting. At the same time, the existence of ‘fast but fragile’ and ‘slow but moderate’ profiles highlight the need for differentiated scaffolding, which is further explored in the discussion considering game-based LA and EfS.

4.4. Interpreting Gameplay Profiles Through Students’ Post-Game Reflections

Although this work focuses primarily on log-based LA, linking the clusters to post-game reflections provides additional insight into how these collaborative gameplay profiles were experienced by students. For each cluster, S2-POST reflections from students in the corresponding groups were examined at group level, focusing on whether and how they described collaboration, perceived challenges and perceived learning about sustainability and the value of Art Nouveau heritage.

Reflections from groups in the ‘thorough and successful’ profile frequently foreground joint exploration and shared decision-making. Students in these groups often report that they discussed each question together, divided attention across different architectural details and used the AR overlays as a common reference point that helped them notice facade details, tiles and decorative elements they would otherwise overlook. Several responses also emphasize that the activity made them “learn more about sustainability and the city” and that the combination of walking, observing and answering questions felt demanding but rewarding, which is consistent with the high accuracy and strong performance on demanding items shown in the logs.

By contrast, reflections associated with ‘fast but fragile’ groups more often mention time pressure, difficulty coordinating answers and uncertainty about where to look or what to prioritize in the context. Students in this profile sometimes describe the activity as feeling like a race, noting that they “answered quickly so we could finish” or that they “did not have time to look carefully at all the details”. Within this cluster, students also referred to moments of confusion about navigation or about how to interpret more complex tasks, which aligns with the lower accuracy on demanding items and the higher pacing index observed in this cluster.

Groups in the ‘slow but moderate’ profile tend to occupy an intermediate position between these two narratives. Their reflections acknowledge both the support provided by AR and multimedia resources and the challenges posed by complex questions, crowded urban spaces and the need to keep the group together. Students in this profile often report taking time to discuss answers and to explore the surroundings, but also mention hesitations, repeated checking of AR content or difficulties managing time along the path. This combination mirrors their longer session durations, moderate pacing and intermediate performance levels.

These qualitative tendencies are consistent with the quantitative indicators, although it is not possible to guarantee perfectly accurate attribution of every individual reflection to a specific cluster. Teacher observations (T2-OBS) were also examined, given their value for understanding the dynamics of the implementation activities and for cross-checking the patterns suggested by the logs and reflections.

Considered as a whole, and by cross-validating previous analyses of the datasets with the present gameplay logs, high-performance groups appear to adopt collaborative strategies that slow down decision-making when needed, distribute attention across team members and use AR overlays and other media as shared artefacts for joint sense-making. ‘Fast but fragile’ groups seem more prone to treating the game as a speed-focused challenge, which can undermine deeper engagement with sustainability concepts and with the cultural heritage context, while ‘slow but moderate’ groups illustrate how extended time on task does not automatically translate into high performance without sufficient focus and coordination. In this sense, the LA profiles do not simply classify groups by achievement; they also point to distinct ways in which collaborative learning with mobile AR unfolds in real urban environments. These patterns open design possibilities for differentiated scaffolding and for supporting teachers, researchers and game designers, which will be further explored in the discussion.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how gameplay logs from a location-based MARG contextualized in an urban heritage district can be transformed into meaningful LA for EfS. Focusing on the

Art Nouveau Path within the EduCITY DTLE, it addressed two research questions: (RQ1) how raw gameplay logs can be converted into a structured set of indicators that characterize collaborative group performance, pacing and task specific difficulty; and (RQ2) which distinct collaborative gameplay profiles emerge when these indicators are analyzed using cluster analysis, and how these profiles relate to students’ qualitative reflections on collaboration, perceived challenge and perceived learning about sustainability and urban cultural heritage. The analysis was based on data from 439 students organized into 118 collaborative groups, who engaged with 36 quiz-based tasks across 8 POIs in Aveiro’s Art Nouveau area, within a broader DBR project [

37,

38] on MARGs and sustainability.

6.1. Main Conclusions

Regarding RQ1, the study showed that relatively group level logs can be transformed into a compact but expressive set of interpretable LA indicators. From raw records of correctness, item completion, session timestamps and AR specific scores for 118 collaborative groups, yielding 4,248 group item responses (3 625 correct and 623 incorrect), the analysis derived measures of overall accuracy (mean 85.33%), mean accuracy per Point of Interest and media type, an AR specific score (mean 46.99, SD = 8.60, range 15.00–55.00), session duration (mean 42.38 minutes, SD = 6.20, range 26.00–55.00 minutes) and a pacing index (mean 0.87 items per minute, range 0.65–1.38). Error mapping further identified a subset of demanding items with accuracies between 58.47% and 72.88%, while most remaining items reached accuracy above 95.00%. Together, these indicators capture both the overall feasibility of the game and the concentration of difficulty in a small set of conceptually loaded tasks that combine dense visual information, spatial reasoning and sustainability related interpretation, echoing calls in the GLA literature for pipelines that move from raw logs to interpretable indicators of performance and difficulty [

12,

13,

14,

15,

19].

Concerning RQ2, the use of cluster analysis to the standardized indicators revealed three distinct collaborative gameplay profiles that are both statistically coherent and pedagogically interpretable. The ‘fast but fragile profile’, comprising 34 groups (28.81% of the sample), the ‘slow but moderate’ profile, including 29 groups (24.58%), and the ‘thorough and successful’ profile, the largest with 55 groups (46.61%).

The definition of these profiles demonstrate that the same MARG and heritage-contextualized path can elicit qualitatively distinct patterns of collaborative engagement, rather than a simple continuum from weaker to stronger performers, aligning with previous work that uses clustering to identify game-based learning profiles [

11,

20,

49].

These profiles are not merely statistical abstractions: 1) ‘Fast but fragile’ groups tend to frame the game as a race, progressing quickly at the cost of accuracy, especially on complex tasks: 2) ‘Slow but moderate’ groups invest substantial time but do not fully convert this investment into high performance, suggesting challenges in coordination or decision making in the field; and, 3) ‘thorough and successful’ groups balance pacing and depth, using the available time and AR resources to achieve very high performance, including on the demanding items.

The use of the qualitative reflections, based on students open-ended answers reinforced textually these profiles analysis and interpretation. This alignment between behavioral indicators and self-reported experiences is consistent with recommendations in LA and XR research to combine log-based profiles with qualitative data when studying immersive experiences [

26,

27,

28].According to this, the present study offers a data grounded and experience grounded answer to RQ2: the same MARG can give rise to three distinct collaborative gameplay profiles that differ systematically in performance, pacing, engagement with AR and perceived experience.

In sum, these findings contribute to three overlapping domains: 1) Regarding LA and GBL, it is exemplified how a pipeline of indicators can be built from group-level logs in a field-based MARG, aligning with and extending existing GLA frameworks to location-based, and collaborative contexts [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Concerning research on immersive and AR enhanced learning, it is provided empirical evidence that fine grained interaction data in mobile AR are not limited to technical monitoring, but can be instrumental in identifying distinct collaborative gameplay styles and in diagnosing how AR-mediated tasks function at item and path level, responding to gaps highlighted in recent XR focused reviews [

24,

25]. 3) Regarding EfS through built heritage, it is demonstrated that a MARG aligned with the GreenComp framework can function as both a curricular resource and a data rich testbed [

3,

36,

53,

54], revealing how students collaboratively engage with complex sustainability-related content in a real urban environment while also indicating where additional scaffolding is needed.

6.2. Limitations

The study’s contributions should be interpreted considering several limitations.

First, all analyses were conducted at group level, without individual identifiers. This design choice precludes analysis of within group role distributions and equity issues related to participation and voice, which are increasingly recognized as important in LA and data informed education [

25]. Future research could combine group level logs with additional, consented data sources such as short interviews combined with anonymized participation records to better understand how individual experiences are embedded within the collaborative profiles.

Second, the analysis focused on a single city, heritage area and MARG. This focus supports ecological validity but limits generalizability. Cultural, curricular and infrastructural conditions in other contexts may shape how students engage with mobile AR, how heritage is interpreted and how sustainability competences are mobilized. Replicating the workflow in other cultural and environmental contexts, with different age groups and educational contexts, would help clarify which aspects of the indicators and profiles are context specific and which may be transferable across mobile AR sustainability development experiences.

Third, although the logs are sufficiently detailed to support the indicators used in this study, their temporal and spatial granularity is constrained. Data was recorded at the level of complete sessions and item outcomes, without dwell time estimates per POI or fine-grained micro navigation traces. This makes it impossible, for example, to reconstruct precise trajectories within each POI or to compare time allocation between specific segments of the path. More detailed logging would permit closer alignment with high resolution trajectory methods and spatial analytics developed in Geographic Information Science.

Fourth, the linking of post-game reflections to cluster membership is necessarily approximate, since reflections are written individually and anonymously, but interpreted at group level. While care was taken to associate reflections with the corresponding groups and to use them in a complementary rather than determinative way, it is not possible to guarantee perfect attribution of every individual comment to a specific profile. Teacher observations (T2-OBS) help to triangulate these interpretations but are likewise limited by their qualitative and selective nature.

Finally, the study adopted a single condition design focused on the Art Nouveau Path and did not include a comparison or control group, such as an analogue or non-AR version of the path. Therefore, no causal claims can be made about the specific impact of the AR component relative to alternative formats. The evidence reported here is observational and design-oriented, concentrating on feasibility and collaborative gameplay patterns rather than on causal effects on learning outcomes. Transfer of learning beyond the activity and retention effects were not assessed and will need to be examined in conjunction with longitudinal data and psychometric validation in future work.

6.3. Implications and Future Work

Despite these limitations, the empirical patterns and profiles identified in this study have concrete implications for the design and orchestration of MARGs in educational-based EfS, as well as for future LA research.