Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State-of-the-Art Models for Water Dissociation (WD) Enhancement in BPMs Junctions

2.1. Second Wien Effect (SWE)

2.2. Catalytic Protonation–Deprotonation Mechanism

2.3. Alternative Models

3. Theoretical

3.1. Power Dissipation Model for Electric-Field-Driven WD

3.1.1. Framework and Working Hypothesis

3.1.1. Analytical Formulation of kd(E)

3.1.2. Junction J-V Relation Derived from

3.2. Theoretical Results

3.2.1. Enhancement and Comparison with SWE

3.2.2. Theoretical J-V Curve of a Nanometric BPM Junction Fully Hydrated

4. Materials and Experimental Methods

4.1. Membrane and Electrodes

4.2. Electrolytes, Cell Type and Components

4.3. Electrochemical Instrumentation and Measurement Protocols

4.4. Three-Electrode Configuration Characterization of the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) and of the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER)

4.5. BPM’s Junction-Voltage Accounting

5. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Symbols (Definitions & Units)

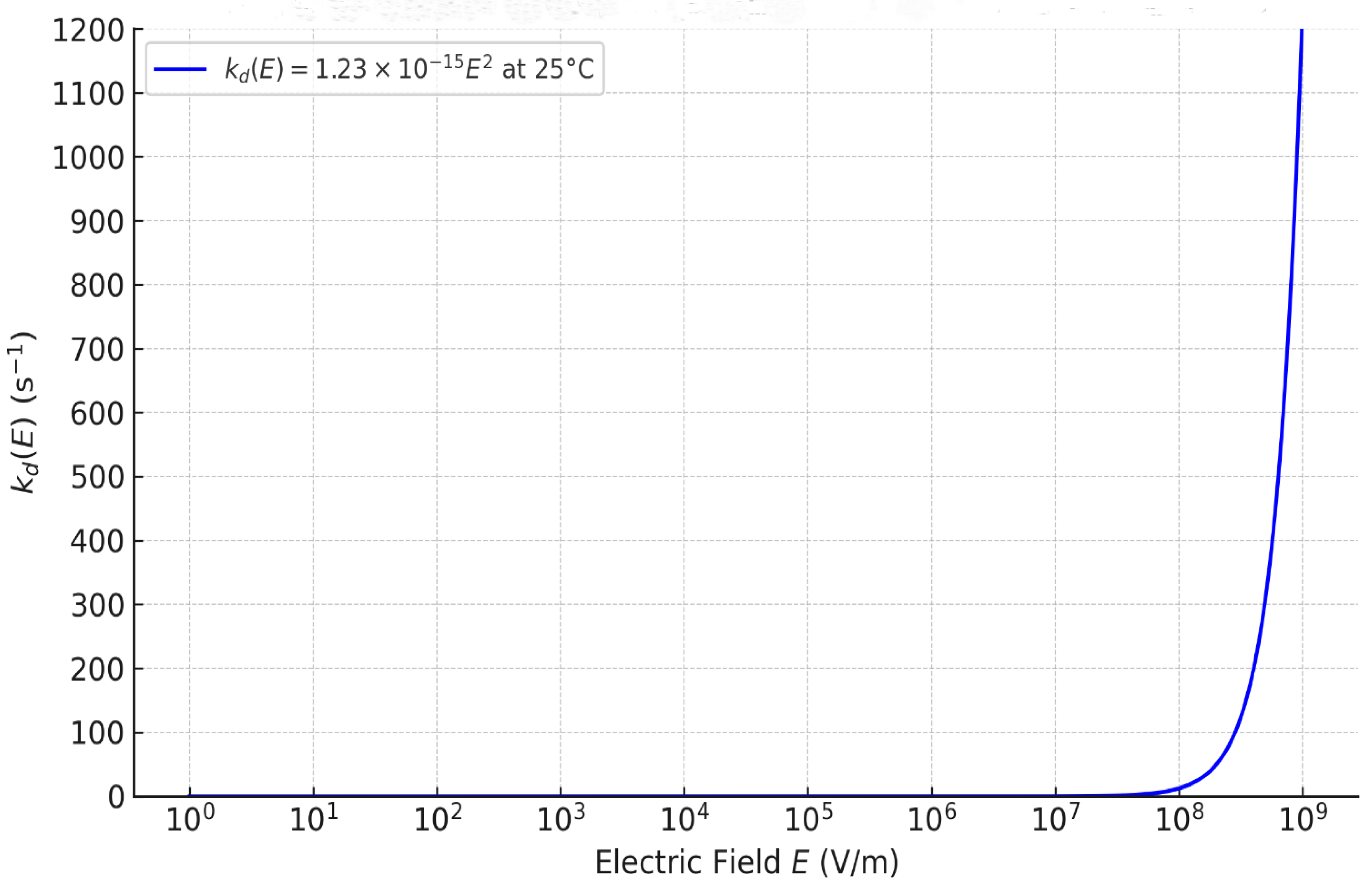

- : Water dissociation rate constant vs field; unit s⁻¹.

- : Thermal WD rate constant (no field); s⁻¹.

- : Electric field in the BPM junction; V·m⁻¹.

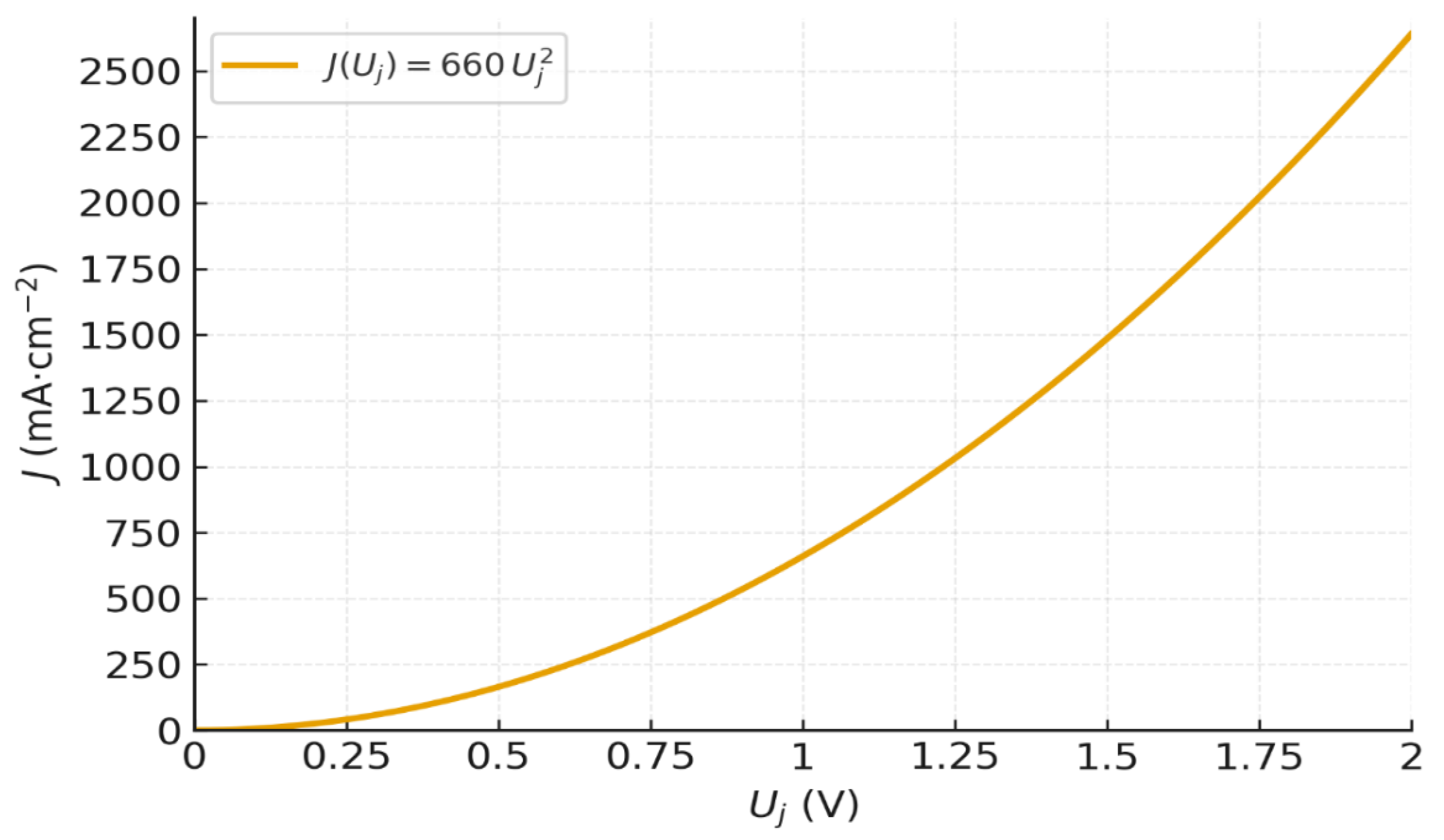

- : Junction voltage drop across active region; V.

- : Junction thickness; m (e.g., 1 nm benchmark).

- : Current density at the junction; mA·cm⁻² .

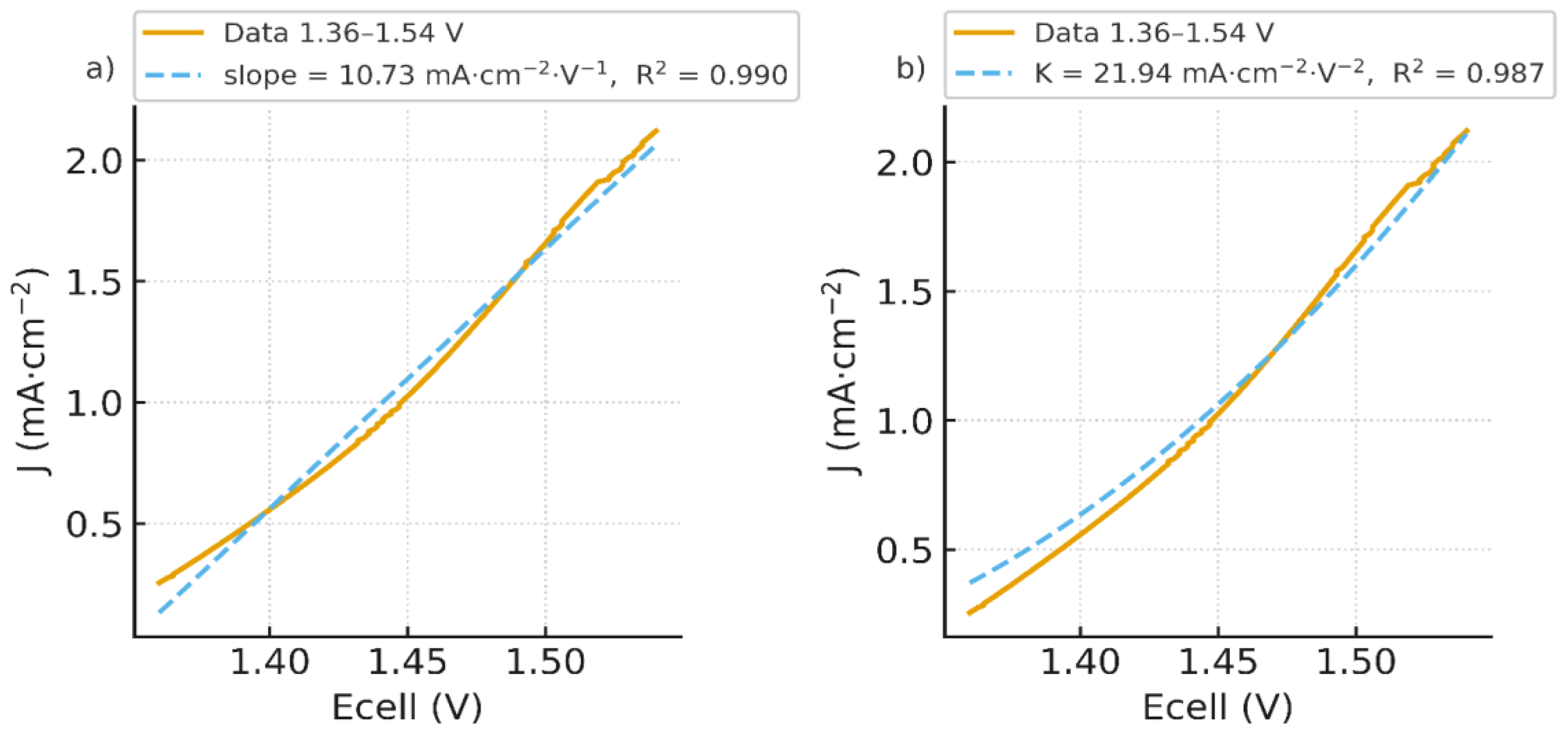

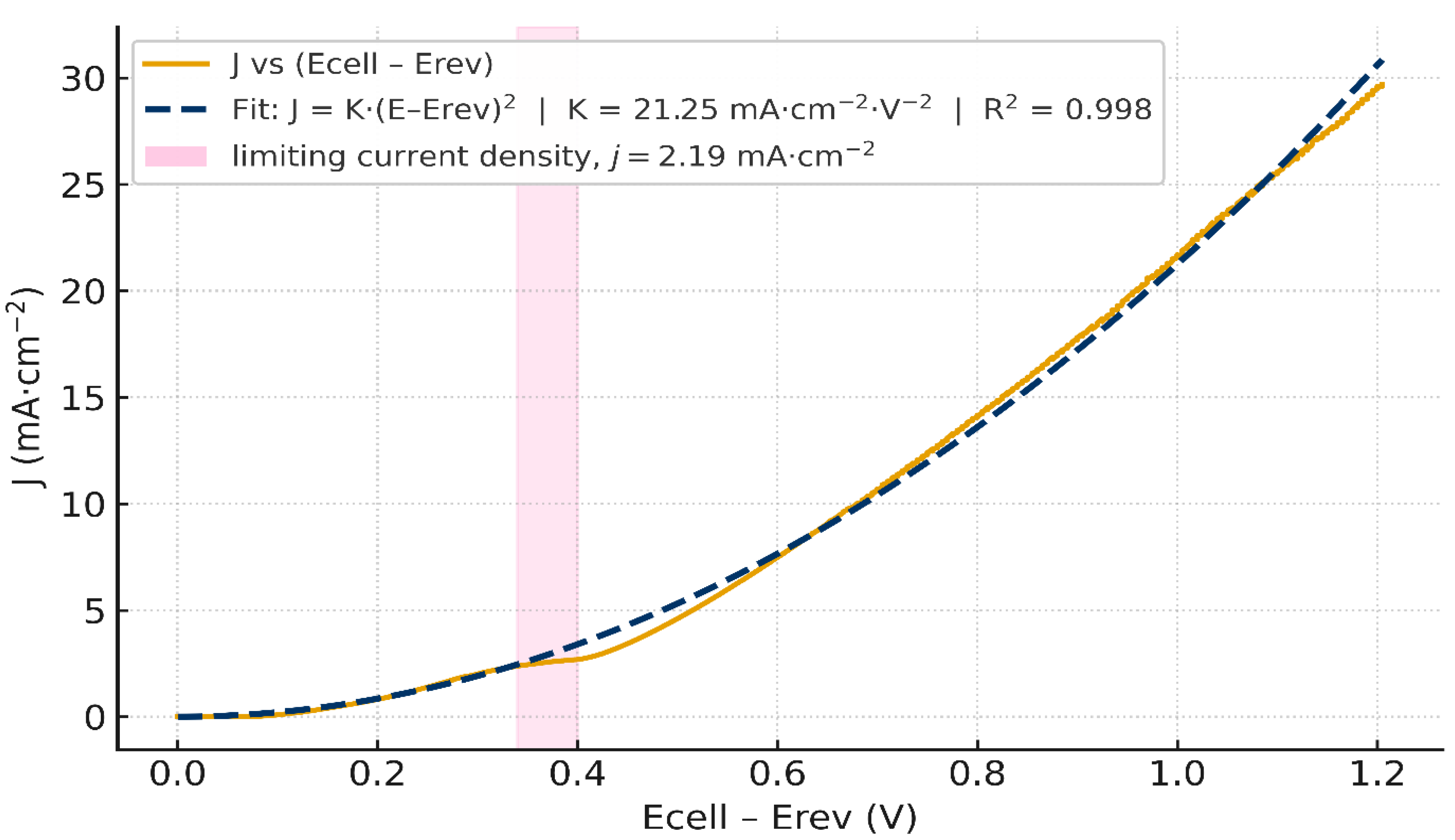

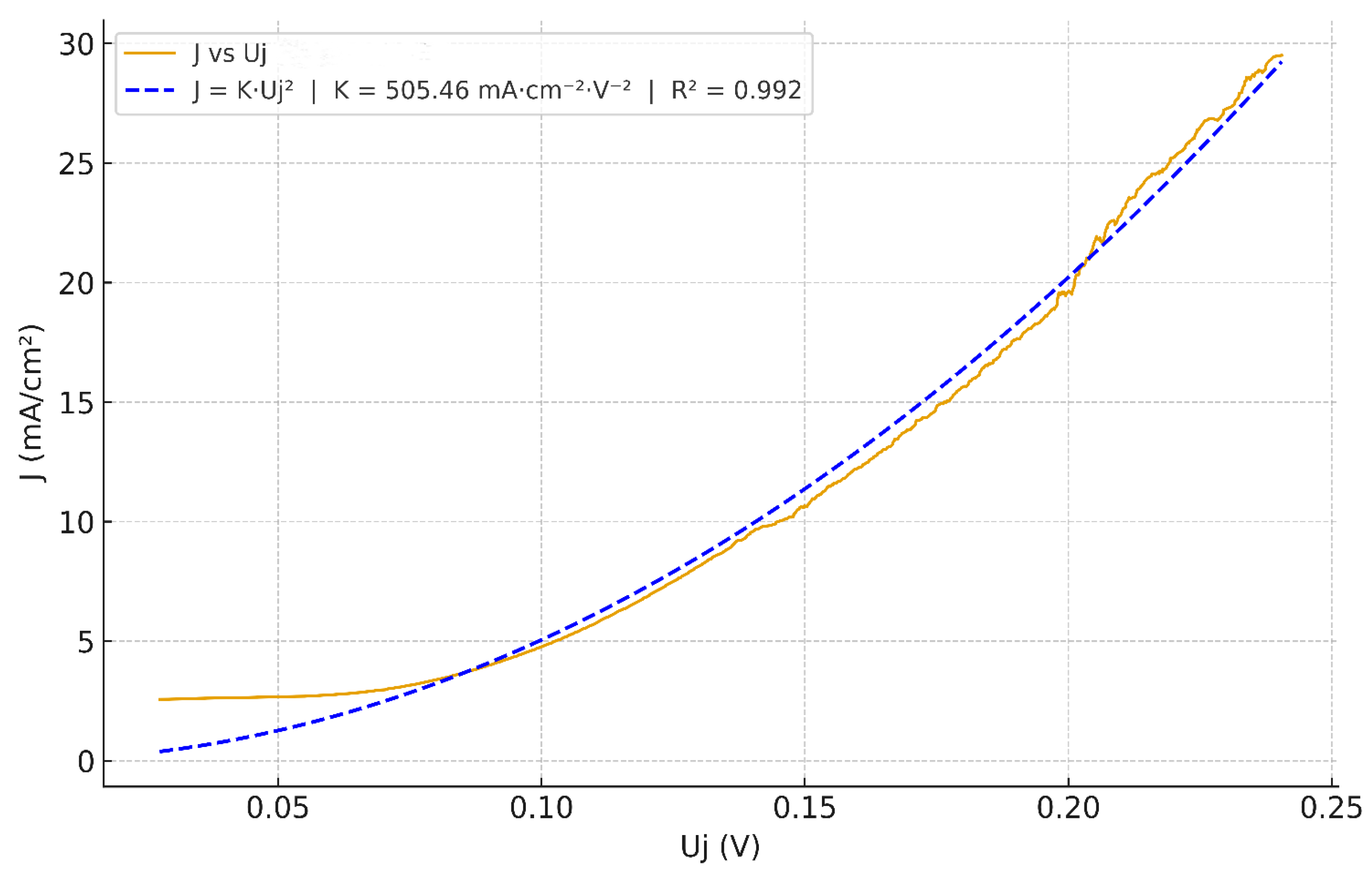

- : Prefactor in junction law ; mA·cm⁻²·V⁻² (when in mA·cm⁻², in V).

- : Water volume fraction in the junction (hydration); dimensionless .

- : Elementary charge; C (e.g., ).

- : Ionic mobilities; m²·V⁻¹·s⁻¹ (e.g., , at 25 °C).

- : Concentration of autoprotolysis ions in water; mol·L⁻¹ (≈ at 25 °C).

- : Concentration of free water; mol·L⁻¹ (≈ 55.5 at 25 °C).

- : Concentration of water in the junction; mol·L⁻¹

- : Threshold dissociation energy per water molecule; J (≈ at 25 °C).

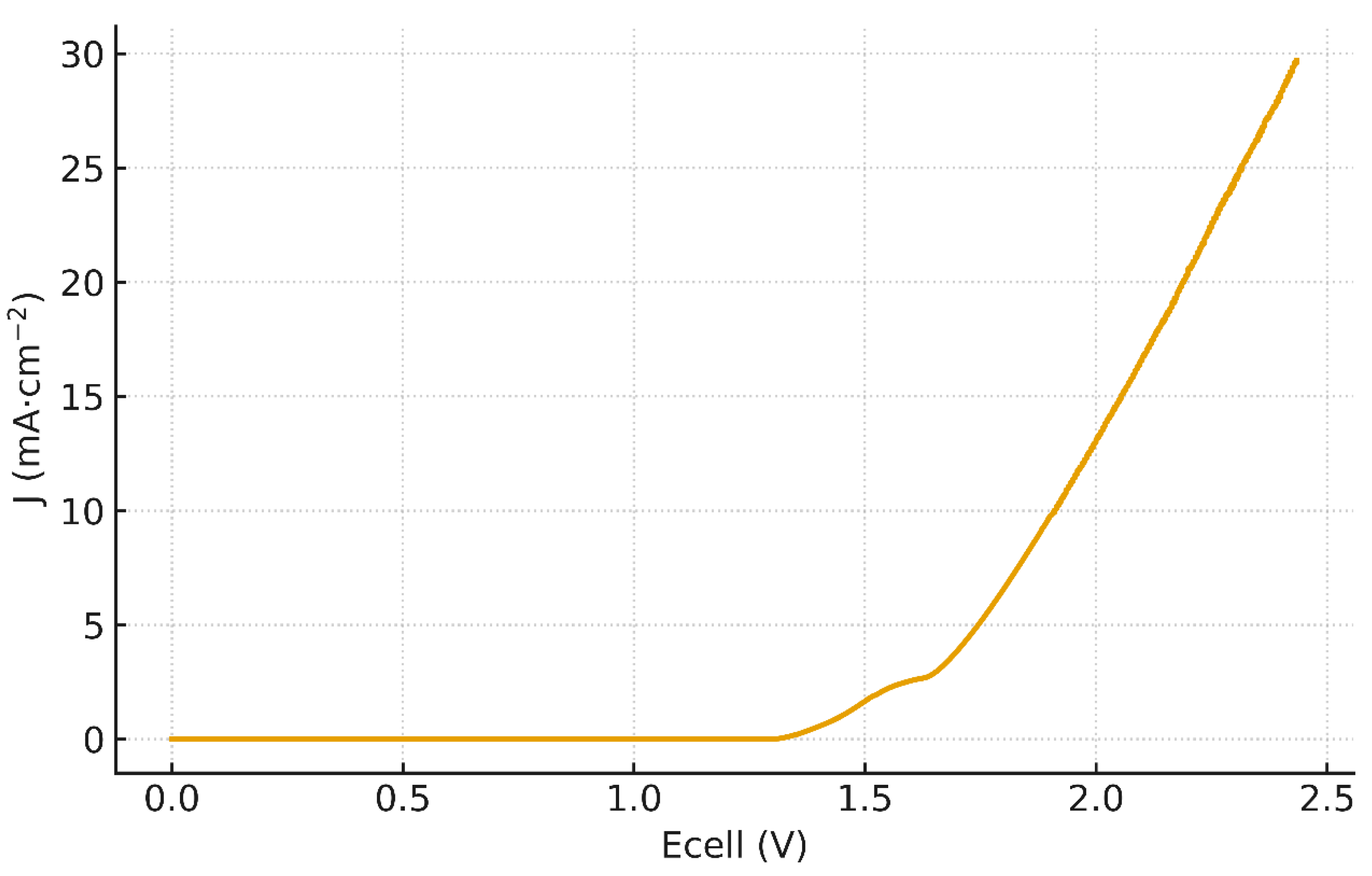

- : Limiting current density (plateau); mA·cm⁻² (≈ 2.19 measured here).

- : Crossover field where ; V·m⁻¹ (≈ ).

- : External cell voltage applied; V.

- : Reversible (equilibrium) voltage of the cell; V (see Eq. 49).

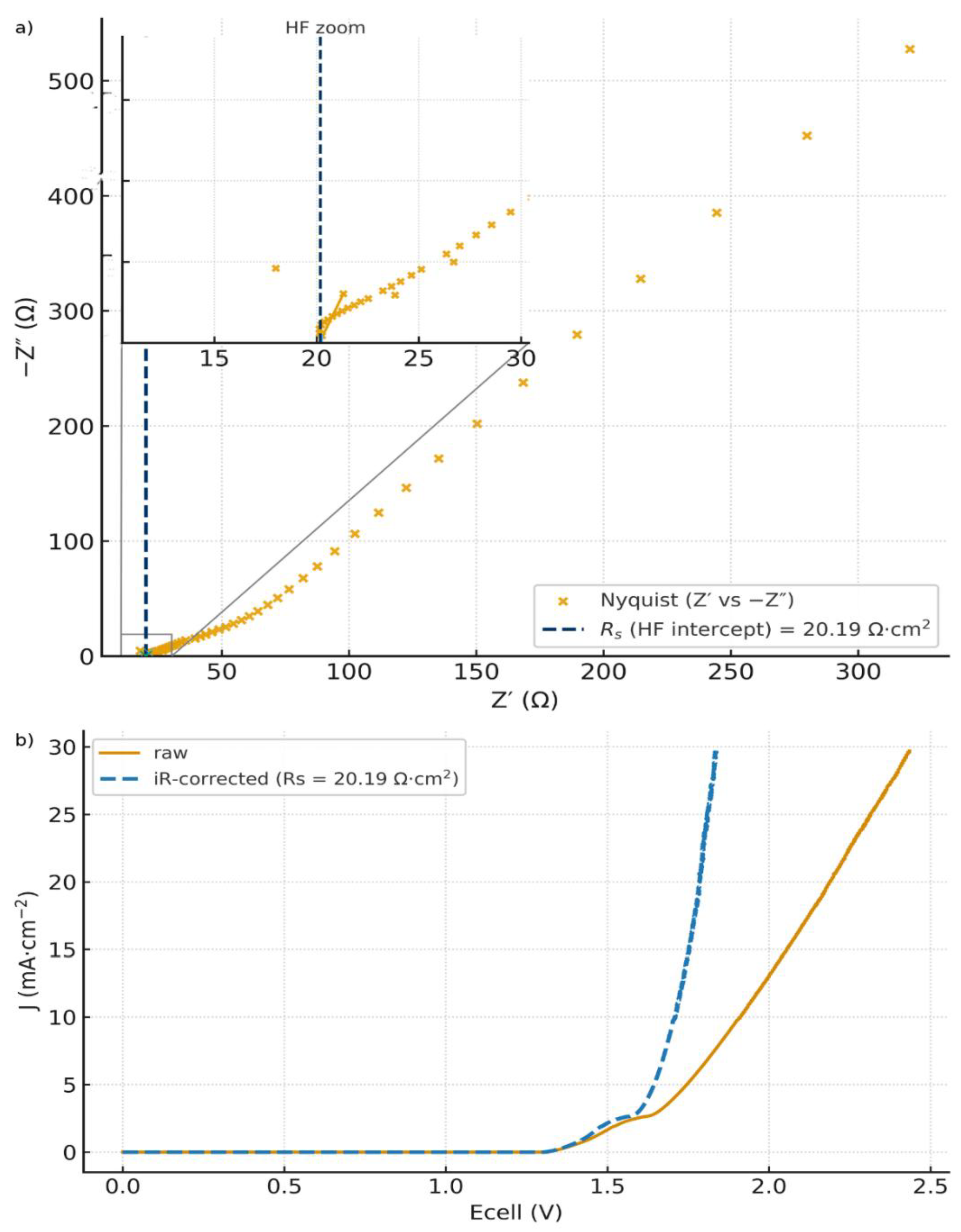

- : Series resistance (two-compartment cell, area-normalized); Ω·cm² (EIS-derived).

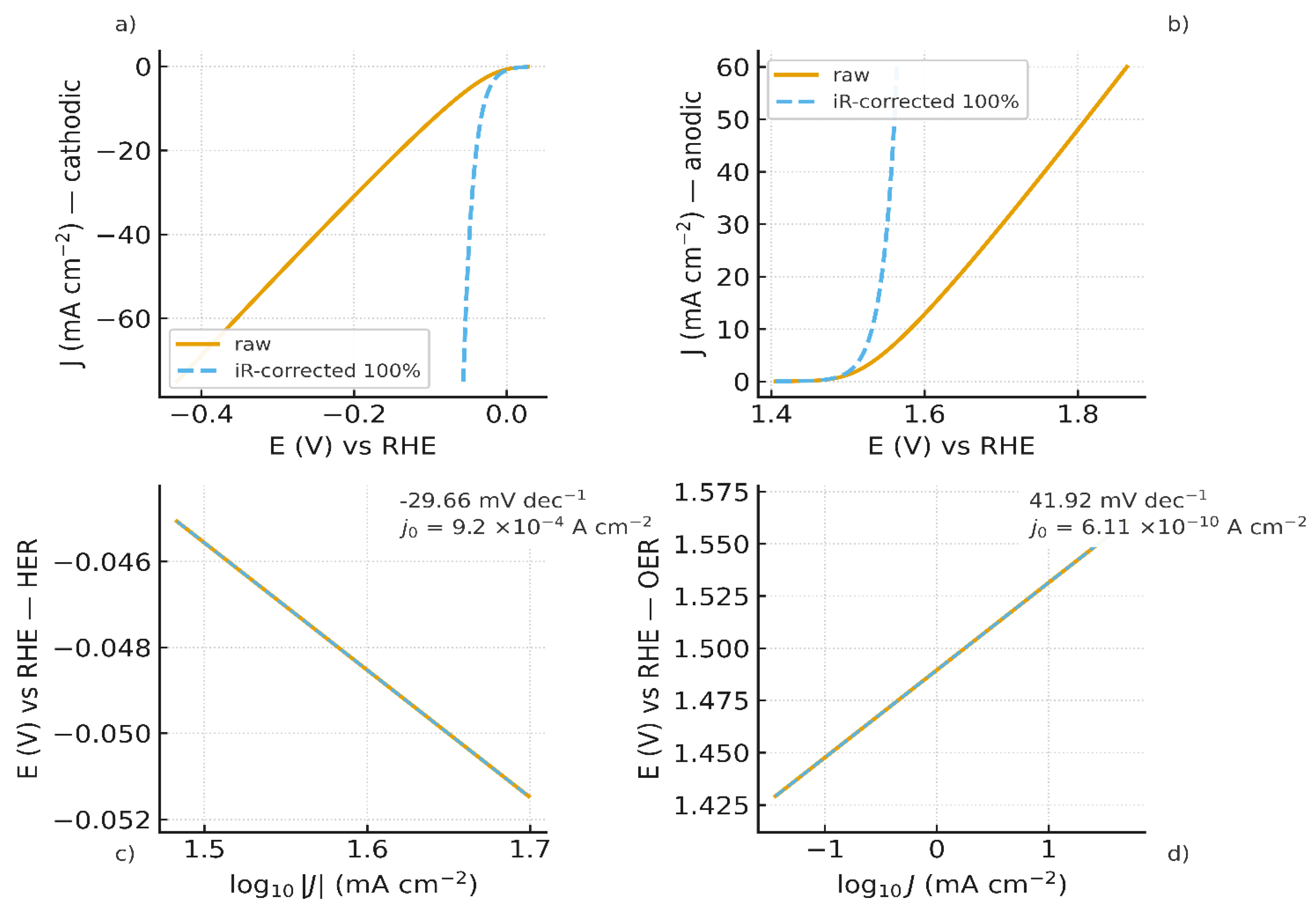

- : Overpotentials for HER/OER; V.

- : Limiting molar conductivity at infinite dilution; S·m²·mol⁻¹ (used to infer ).

- : Faraday constant; C·mol⁻¹ (96 485).

- : Viscosity (in Stokes–Einstein context for ); Pa·s.

- : Tafel slope; mV·dec⁻¹.

- : Exchange current density; A·cm⁻².

- : Drift velocity of ions under the field; m·s⁻¹. (Relation: .)

- : Per-ion Field-supplied power dissipated by drift; (J·s⁻¹). (Model: .)

- : Per-ion power for and ; (J·s⁻¹).

- : Number density of autoprotolysis ions; m⁻³.

- : Junction volume (membrane area × active thickness ); m³.

- : Total power dissipated in the junction by all ions; (J·s⁻¹)

- : Power density dissipated by in the junction; J·s⁻¹·m⁻³.

- : Molar Gibbs free energy of water dissociation; ( kJ·mol⁻¹). (Used to compute the per-molecule threshold .)

- : Avogadro constant; mol⁻¹.

- : Thermal conductivity of water used in the heating estimate; W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹

- : Estimated junction temperature rise from dissipation; K.

- : Membrane area used in estimates; m² (our benchmark: 1 cm²).

- : Relative permittivity; dimensionless.

- : Absolute temperature; K (reference 298 K / 25 °C).

- R: Universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹· K⁻¹)

- : Water equilibrium constant ( at 25 °C)

References

- Pärnamäe, R.; Mareev, S.; Nikonenko, V.; Melnikov, S.; Sheldeshov, N.; Zabolotskii, V.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Tedesco, M. Bipolar Membranes: A Review on Principles, Latest Developments, and Applications. Journal of Membrane Science 2021, 617, 118538. [CrossRef]

- Tufa, R.A.; Blommaert, M.A.; Chanda, D.; Li, Q.; Vermaas, D.A.; Aili, D. Bipolar Membrane and Interface Materials for Electrochemical Energy Systems. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 7419–7439. [CrossRef]

- Strathmann, H.; Krol, J.J.; Rapp, H.-J.; Eigenberger, G. Limiting Current Density and Water Dissociation in Bipolar Membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 1997, 125, 123–142. [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, P.K.; Freund, M.S. Recent Advances in Bipolar Membrane Design and Applications. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 8060–8090. [CrossRef]

- Strathmann, H. Ion-Exchange Membrane Separation Processes; Membrane science and technology series; 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam Boston, 2004; ISBN 978-0-444-50236-0.

- Tanaka, Y. Ion Exchange Membranes: Fundamentals and Applications; 2nd edition.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2015; ISBN 978-0-444-63319-4.

- Blommaert, M.A.; Aili, D.; Tufa, R.A.; Li, Q.; Smith, W.A.; Vermaas, D.A. Insights and Challenges for Applying Bipolar Membranes in Advanced Electrochemical Energy Systems. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 2539–2548. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Jing, X.; Yan, W.; Xu, H. Bipolar Membranes: A Review on Principles, Preparation Methods and Applications in Environmental and Resource Recovery. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 507, 160184. [CrossRef]

- Tufa, R.A.; Chanda, D.; Ma, M.; Aili, D.; Demissie, T.B.; Vaes, J.; Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Pant, D. Towards Highly Efficient Electrochemical CO2 Reduction: Cell Designs, Membranes and Electrocatalysts. Applied Energy 2020, 277, 115557. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Lu, S.; Xiang, Y. Enhancing Water Distribution in High-Performance Bipolar Membrane Fuel Cells through Optimized Interface Architecture. Journal of Power Sources 2025, 632, 236306. [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Gao, L.; Yang, C. Recent Development and Challenges of Bipolar Membranes for High Performance Water Electrolysis. ACS Materials Lett. 2024, 6, 1623–1648. [CrossRef]

- Oener, S.Z.; Ardo, S.; Boettcher, S.W. Ionic Processes in Water Electrolysis: The Role of Ion-Selective Membranes. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 2625–2634. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.J.; Farrell, J. Quantifying Electric Field Enhancement of Water Dissociation Rates in Bipolar Membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 782–789. [CrossRef]

- Krol, J.J. MONOPOLAR AND BIPOLAR ION EXCHANGE MEMBRANES Mass Transport Limitations.

- Strathmann, H. Electrodialysis, a Mature Technology with a Multitude of New Applications. Desalination 2010, 264, 268–288. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Simons, R.; Weidenhaun, J. The Low Frequency Conductance of Bipolar Membranes Demonstrates the Presence of a Depletion Layer. Journal of Membrane Science 1998, 140, 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Eigen, M. Methods for Investigation of Ionic Reactions in Aqueous Solutions with Half-Times as Short as 10–9 Sec. Application to Neutralization and Hydrolysis Reactions. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1954, 17, 194–205. [CrossRef]

- Mareev, S.A.; Evdochenko, E.; Wessling, M.; Kozaderova, O.A.; Niftaliev, S.I.; Pismenskaya, N.D.; Nikonenko, V.V. A Comprehensive Mathematical Model of Water Splitting in Bipolar Membranes: Impact of the Spatial Distribution of Fixed Charges and Catalyst at Bipolar Junction. Journal of Membrane Science 2020, 603, 118010. [CrossRef]

- Bui, J.C.; Digdaya, I.; Xiang, C.; Bell, A.T.; Weber, A.Z. Understanding Multi-Ion Transport Mechanisms in Bipolar Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 52509–52526. [CrossRef]

- Bui, J.C.; Corpus, K.R.M.; Bell, A.T.; Weber, A.Z. On the Nature of Field-Enhanced Water Dissociation in Bipolar Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 24974–24987. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, V. The Wien Effect in Electric and Magnetic Coulomb Systems - from Electrolytes to Spin Ice, Ecole normale supérieure de lyon - ENS LYON; Technische Universität (Dresde, Allemagne). Max-Planck-Institut für Physik komplexer Systeme, 2014.

- Eckstrom, H.C.; Schmelzer, Christoph. The Wien Effect: Deviations of Electrolytic Solutions from Ohm’s Law under High Field Strengths. Chem. Rev. 1939, 24, 367–414. [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Deviations from Ohm’s Law in Weak Electrolytes. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1934, 2, 599–615. [CrossRef]

- Zabolotskii, V.I.; Shel’deshov, N.V.; Gnusin, N.P. Dissociation of Water Molecules in Systems with Ion-Exchange Membranes. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1988, 57, 801–808. [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, H.D.; Dibiani, R. Experimental and Theoretical Investigations of Steady and Transient States in Systems of Ion Exchange Bipolar Membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2004, 228, 17–43. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Water Dissociation Reaction Generated in an Ion Exchange Membrane. Journal of Membrane Science 2010, 350, 347–360. [CrossRef]

- Jialin, L.; Yazhen, W.; Changying, Y.; Guangdou, L.; Hong, S. Membrane Catalytic Deprotonation Effects. Journal of Membrane Science 1998, 147, 247–256. [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, C.-O.; Dahlkild, A.; Velin, A.; Behm, M. A Model for the Enhanced Water Dissociation on Monopolar Membranes. Electrochimica Acta 2009, 54, 2983–2991. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Griffin, E.; Guarochico-Moreira, V.H.; Barry, D.; Xin, B.; Yagmurcukardes, M.; Zhang, S.; Geim, A.K.; Peeters, F.M.; Lozada-Hidalgo, M. Wien Effect in Interfacial Water Dissociation through Proton-Permeable Graphene Electrodes. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5776. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J. ELECTRIC FIELD EFFECT IN WATER DISSOCIATION ACROSS ATOMICALLY THICK GRAPHENE, The University of Manchester, 2022.

- Silva, G.M.; Liang, X.; Kontogeorgis, G.M. How to Account for the Concentration Dependency of Relative Permittivity in the Debye–Hückel and Born Equations. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2023, 566, 113671. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, S.; Kannam, S.K.; Hansen, J.S.; Sathian, S.P. Effect of Hydrogen Bonds on the Dielectric Properties of Interfacial Water. Langmuir 2019, 35, 8159–8166. [CrossRef]

- Simons, R. Electric Field Effects on Proton Transfer between Ionizable Groups and Water in Ion Exchange Membranes. Electrochimica Acta 1984, 29, 151–158. [CrossRef]

- Simons, R. Water Splitting in Ion Exchange Membranes. Electrochimica Acta 1985, 30, 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, P.; Rapp, H.J.; Reichle, S.; Strathmann, H.; Mafé, S. Current-Voltage Curves of Bipolar Membranes. Journal of Applied Physics 1992, 72, 259–264. [CrossRef]

- Mafé, S.; Ramı́rez, P.; Alcaraz, A. Electric Field-Assisted Proton Transfer and Water Dissociation at the Junction of a Fixed-Charge Bipolar Membrane. Chemical Physics Letters 1998, 294, 406–412. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Yang, W.; He, B. Water Dissociation Phenomena in a Bipolar Membrane: The Configurations and Theoretical Voltage Analysis. Sc. China Ser. B-Chem. 1999, 42, 589–598. [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, P.K.; Freund, M.S. Influence of the pH Gradient on Bipolar Membrane Operation. ACS Electrochem. 2025, 1, 667–677. [CrossRef]

- Saitta, A.M.; Saija, F.; Giaquinta, P.V. Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Study of Dissociation of Water under an Electric Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 207801. [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, H.D.; Dibiani, R. Investigation of Electrical Properties of Bipolar Membranes at Steady State and with Transient Methods. Electrochimica Acta 2001, 47, 759–773. [CrossRef]

- Grew, K.N.; McClure, J.P.; Chu, D.; Kohl, P.A.; Ahlfield, J.M. Understanding Transport at the Acid-Alkaline Interface of Bipolar Membranes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, F1572–F1587. [CrossRef]

- Miesiac, I.; Rukowicz, B. Bipolar Membrane and Water Splitting in Electrodialysis. Electrocatalysis 2022, 13, 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Rodellar, C.G.; Gisbert-Gonzalez, J.M.; Sarabia, F.; Roldan Cuenya, B.; Oener, S.Z. Ion Solvation Kinetics in Bipolar Membranes and at Electrolyte–Metal Interfaces. Nat Energy 2024, 9, 548–558. [CrossRef]

- Pärnamäe, R.; Tedesco, M.; Wu, M.-C.; Hou, C.-H.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Patel, S.K.; Elimelech, M.; Biesheuvel, P.M.; Porada, S. Origin of Limiting and Overlimiting Currents in Bipolar Membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9664–9674. [CrossRef]

- Usenik, A.; Kallay, N.; Tomišić, V. Motion of Ions in Solution under the Influence of an Electric Field: Microscopic versus Macroscopic View. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101, 3805–3812. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Kumar, D.; Verma, D.K.; Parwati, K.; Ranjan, P.; Rai, R.; Krishnamoorthi, S.; Khan, R. Fundamental Chemical and Physical Properties of Electrolytes in Energy Storage Devices: A Review. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 81, 110361. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Cai, P.; Wen, Z. Electrochemical Neutralization Energy: From Concept to Devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1495–1511. [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.; Khanarian, G. Water Dissociation in Bipolar Membranes: Experiments and Theory. J. Membrain Biol. 1978, 38, 11–30. [CrossRef]

- Kondepudi, D.; Prigogine, I. Modern Thermodynamics: From Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures; 1st ed.; Wiley, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-37181-7.

- Vincent, C.A. The Motion of Ions in Solution under the Influence of an Electric Field. J. Chem. Educ. 1976, 53, 490. [CrossRef]

- Erdey-Grúz, T.; Erdey-Grúz, T. Transport Phenomena in Aqueous Solutions; Hilger [u.a.]: London, 1974; ISBN 978-0-85274-207-5.

- Berthoumieux, H.; Démery, V.; Maggs, A.C. Nonlinear Conductivity of Aqueous Electrolytes: Beyond the First Wien Effect. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2024, 161, 184504. [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Hwang, Y.; Chai, L.; Kampf, N.; Klein, J. Direct Measurement of the Viscoelectric Effect in Water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2113690119. [CrossRef]

- Kestin, J.; Sokolov, M.; Wakeham, W.A. Viscosity of Liquid Water in the Range −8 °C to 150 °C. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 1978, 7, 941–948. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.V.; Lvov, S.N. The Ionization Constant of Water over Wide Ranges of Temperature and Density. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 2006, 35, 15–30. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Digdaya, I.A.; Xiang, C. Modeling the Electrochemical Behavior and Interfacial Junction Profiles of Bipolar Membranes at Solar Flux Relevant Operating Current Densities. Sustainable Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 2149–2158. [CrossRef]

- Weiland, O.; Trinke, P.; Bensmann, B.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R. Modelling Water Transport Limitations and Ionic Voltage Losses in Bipolar Membrane Water Electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 054505. [CrossRef]

- Wrubel, J.A.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Z.; Deutsch, T.G. Modeling Water Electrolysis in Bipolar Membranes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 114502. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Wang, B.; Wang, P.; Liu, S. Hydrogen Generation with Acid/Alkaline Amphoteric Water Electrolysis. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2019, 38, 162–169. [CrossRef]

- Chatenet, M.; Pollet, B.G.; Dekel, D.R.; Dionigi, F.; Deseure, J.; Millet, P.; Braatz, R.D.; Bazant, M.Z.; Eikerling, M.; Staffell, I.; et al. Water Electrolysis: From Textbook Knowledge to the Latest Scientific Strategies and Industrial Developments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 4583–4762. [CrossRef]

- Van Drunen, J.; Pilapil, B.K.; Makonnen, Y.; Beauchemin, D.; Gates, B.D.; Jerkiewicz, G. Electrochemically Active Nickel Foams as Support Materials for Nanoscopic Platinum Electrocatalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 12046–12061. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhubhani, E.; Pärnamäe, R.; Post, J.W.; Saakes, M.; Tedesco, M. Performance of Five Commercial Bipolar Membranes under Forward and Reverse Bias Conditions for Acid-Base Flow Battery Applications. Journal of Membrane Science 2021, 640, 119748. [CrossRef]

- Vermaas, D.A.; Sassenburg, M.; Smith, W.A. Photo-Assisted Water Splitting with Bipolar Membrane Induced pH Gradients for Practical Solar Fuel Devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 19556–19562. [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Verlage, E.; Lewis, N.S.; Xiang, C. A Stabilized, Intrinsically Safe, 10% Efficient, Solar-Driven Water-Splitting Cell Incorporating Earth-Abundant Electrocatalysts with Steady-State pH Gradients and Product Separation Enabled by a Bipolar Membrane. Advanced Energy Materials 2016, 6, 1600379. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Q.; Boettcher, S.W. Kinetics and Mechanism of Heterogeneous Voltage-Driven Water-Dissociation Catalysis. Joule 2023, 7, 1867–1886. [CrossRef]

- Litman, Y.; Michaelides, A. Entropy Governs the Structure and Reactivity of Water Dissociation Under Electric Fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, jacs.5c12397. [CrossRef]

| Electric Field, E (V·m⁻¹) | WD rate, (E) (s-1) | Ratio increase, / |

| 1 × 10⁸ | 12.3 | 4.92 × 10⁵ |

| 5 × 10⁸ | 307 | 1.23 × 10⁷ |

| 8 × 10⁸ | 787 | 3.15 × 10⁷ |

| 1 × 10⁹ | 1230 | 4.92 × 10⁷ |

| 2 × 10⁹ | 4920 | 1.97 × 10⁸ |

| Model |

for E = 10⁸ V·m⁻¹ |

for E = 2×10⁹ V·m⁻¹ |

Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

| =78) | 3.67 | 4.07×10⁴ | Too slow |

| variable) | 3.67 | 8.05×10¹¹ | Improved but unstable |

| =10) | 3.07×10² | 3,43×10¹⁵ | Divergence |

| =5) | 8.61×10³ | 6.18× | Extreme divergence |

| Our quadratic model | 4.92×10⁵ | 1.97×10⁸ | Gradual, realistic increase |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).