Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

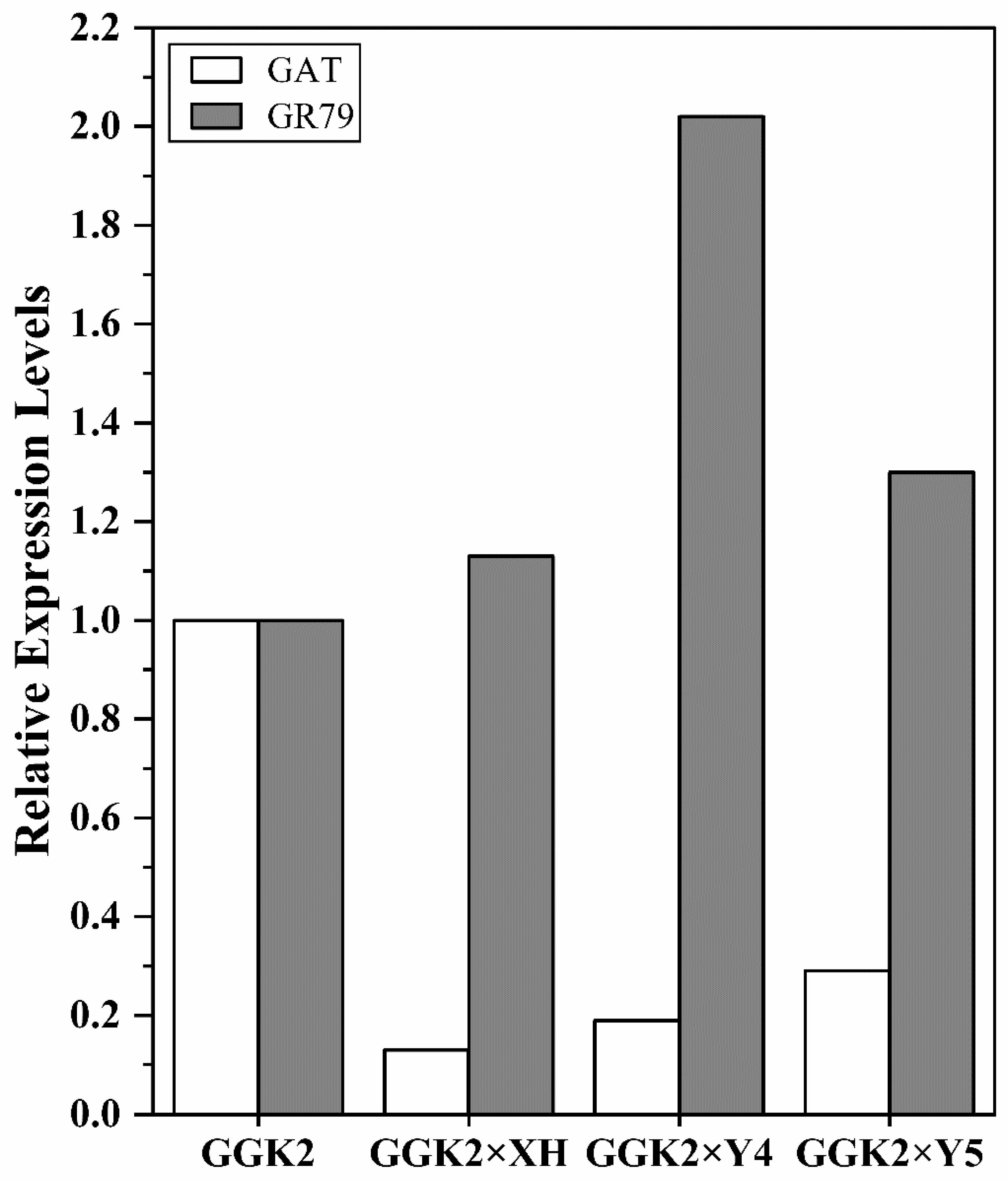

Weed stress remains a major limiting factor in cotton production, and glyphosate-tolerant varieties provide an effective solution for chemical weed control. However, achieving a balance between herbicide tolerance and agronomic physiological traits remains challenging. In this study, three hybrid combinations were generated by crossing a glyphosate-tolerant cotton line (GGK2) with conventional elite lines and were comprehensively evaluated. Gene expression analysis revealed that the classical detoxification gene GAT was significantly downregulated in all hybrid combinations, whereas the expression of GR-79, a gene associated with glutathione metabolism and oxidative stress response, was markedly elevated, particularly in the GGK2 × Y4 combination. This differential expression pattern suggests that GR-79 may compensate for the reduced function of GAT by conferring oxidative protection under herbicide stress. Physiological determination indicated that hybrid combinations with enhanced GR-79 expression, especially GGK2 × Y5, exhibited superior photosynthetic pigment composition and photosystem II (PSII) efficiency, validating the role of GR-79 in maintaining photosynthetic stability. Agronomic trait assessment demonstrated that GGK2 × Y4 achieved significant biomass accumulation and yield improvement through heterosis, although fiber quality improvement was limited. This study effectively enhanced the herbicide resistance of conventional cotton through crossbreeding and revealed that the interaction between GR-79 and GAT can improve cotton tolerance to herbicides, thereby providing a breeding strategy for developing cotton varieties with both herbicide tolerance and superior agronomic traits.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Differential Expression of GAT and GR-79 in Cotton Male Parents and Hybrids

| Primer name | Primer 5’→3’ |

| RT GAT-F | AAGCAAGGAGGAGTGGTTGC |

| RT GAT-R | TCTTGCCTCCGATGAACTTG |

| RT GR-79-F | TGATGGAGACCATGAGAGTG |

| RT GR-79-R | CTCCAGGAAGTTGTCTGGTG |

| UBQ-F | AGAGGTCGAGTCTTCGGACACC |

| UBQ-R | TGCTTGATCTTCTTGGGCTTGG |

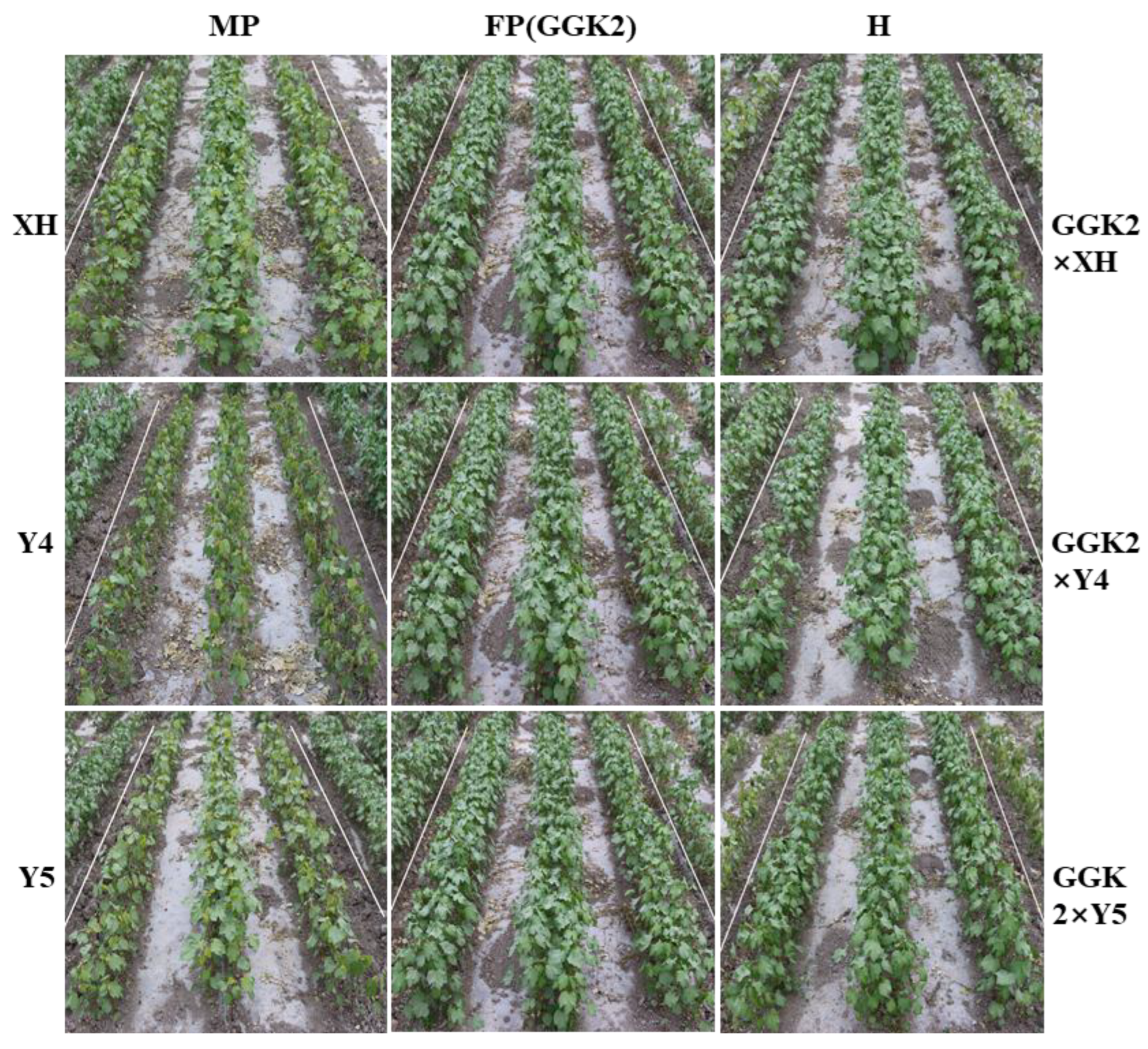

2.2. Phenotypic Responses of Parental and Hybrid Cotton Lines Under Herbicide Stress

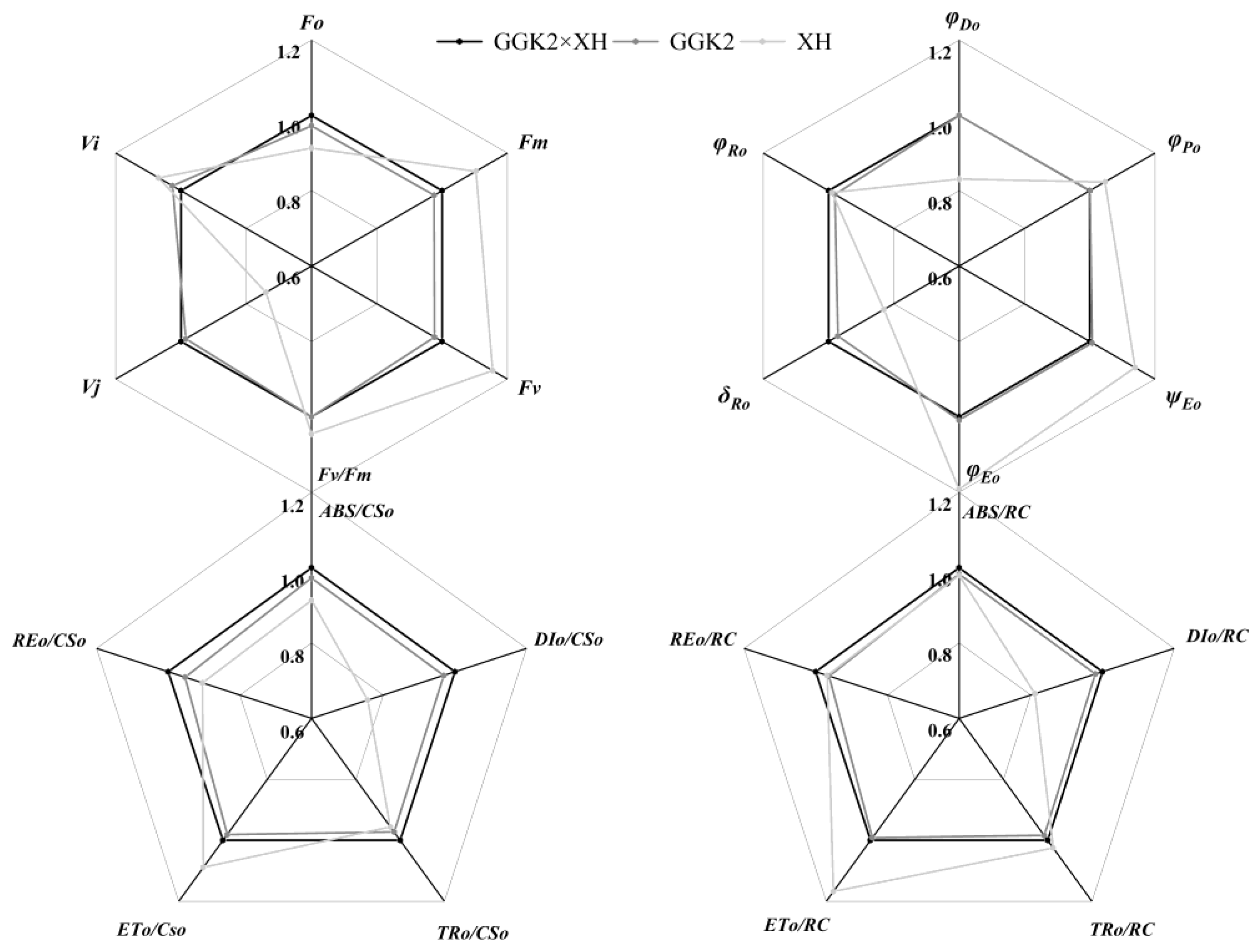

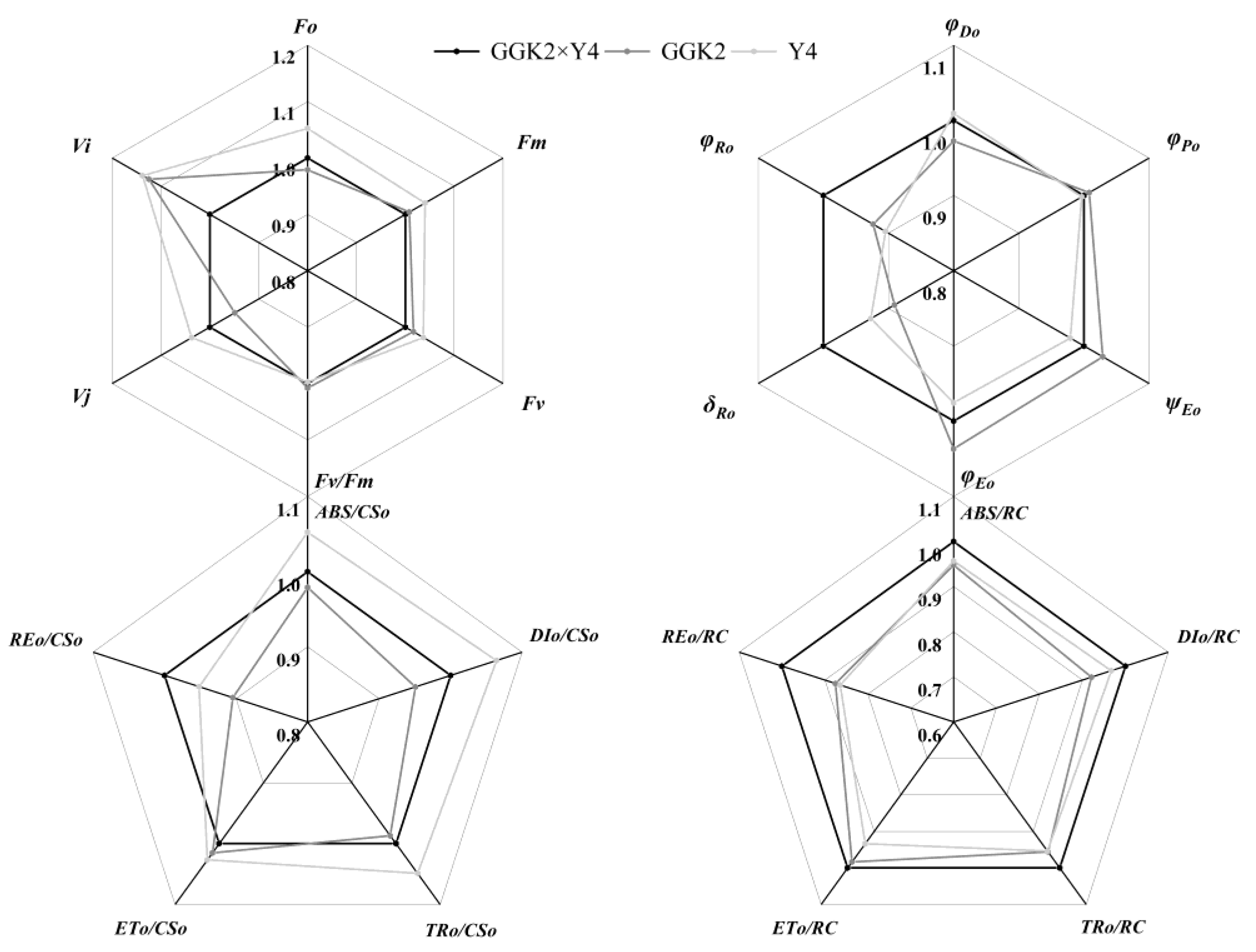

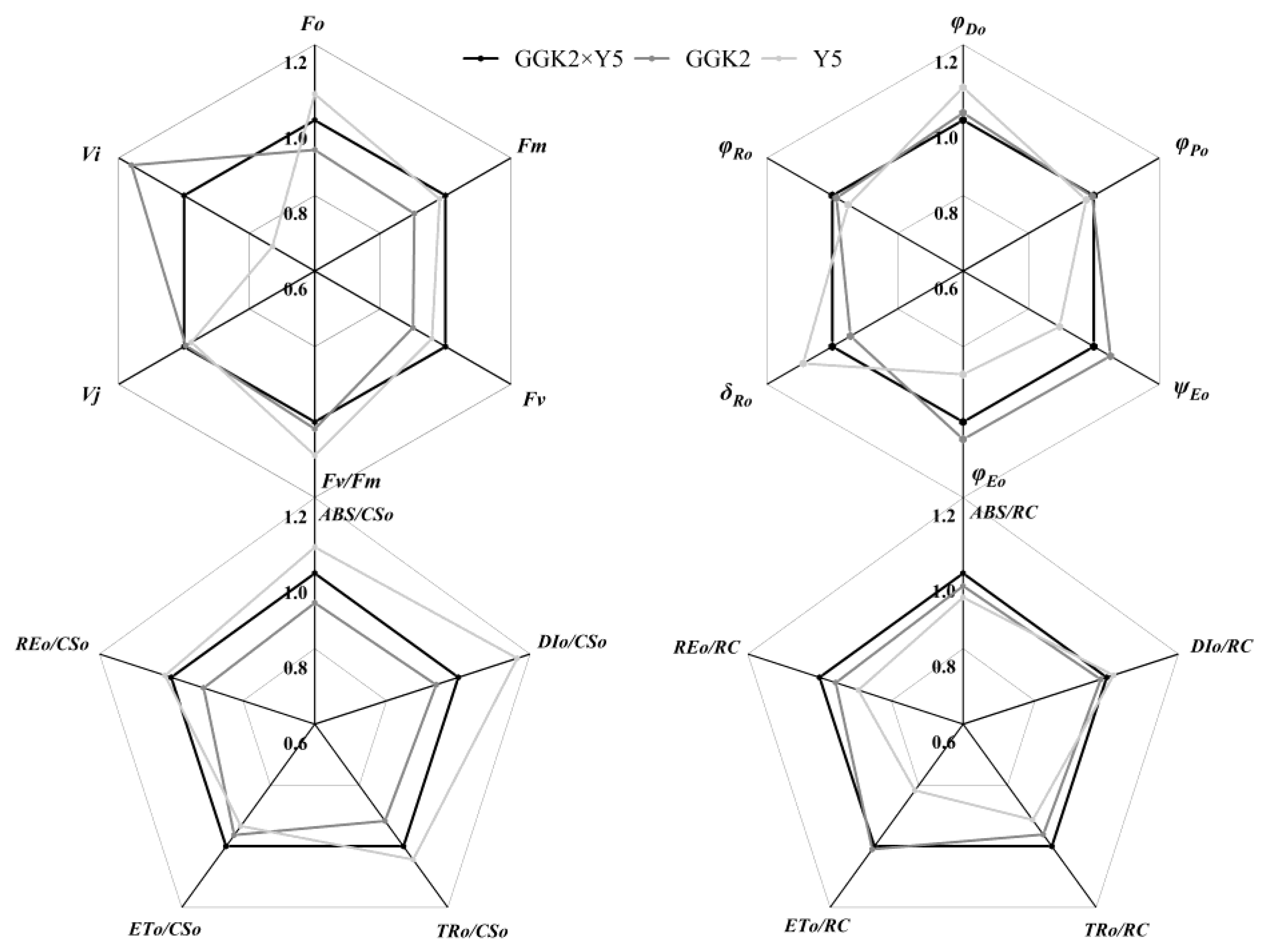

2.2. Study on Photosynthetic Pigment Accumulation and PSII Performance in Herbicide-Resistant Cotton Hybrids

| Plant lines | Chl a | Chl b | Car | Chl T | Chl a/b |

| GGK2 | 1.05±0.11a | 0.32±0.04a | 0.05±0.01a | 1.36±0.15a | 3.26±0.05b |

| XH | 1.04±0.10a | 0.32±0.04a | 0.05±0.01a | 1.35±0.14a | 3.14±0.12b |

| GGK2×XH | 0.99±0.07a | 0.30±0.03a | 0.05±0.01a | 1.30±0.10a | 3.56±0.15a |

| MPH | -4.76% | -4.62% | -5.21% | -4.72% | 11.32% |

| SPH | -5.07% | -5.30% | -7.84% | -5.12% | 9.36% |

| GGK2 | 1.05±0.11a | 0.32±0.04a | 0.05±0.01a | 1.36±0.15a | 3.26±0.05a |

| Y4 | 1.09±0.12a | 0.35±0.06a | 0.04±0.01a | 1.44±0.18a | 3.31±0.11a |

| GGK2×Y4 | 0.99±0.01a | 0.28±0.01a | 0.05±0.01a | 1.26±0.013a | 3.29±0.12a |

| MPH | -7.82% | -17.74% | 8.32% | -10.19% | 0.15% |

| SPH | -9.80% | -21.35% | 3.04% | -12.61% | -0.61% |

| GGK2 | 1.05±0.11ab | 0.32±0.05a | 0.049±0.01a | 1.36±0.15a | 3.26±0.05b |

| Y5 | 0.87±0.05b | 0.26±0.020a | 0.06±0.01a | 1.13±0.07a | 3.41±0.10ab |

| GGK2×Y5 | 1.23±0.09a | 0.33±0.03a | 0.06±0.01a | 1.56±0.12a | 3.75±0.12a |

| MPH | 28.08% | 14.09% | 22.39% | 24.84% | 12.51% |

| SPH | 17.34% | 2.49% | 15.18% | 13.86% | 9.86% |

2.3. Analysis of Biomass Distribution, Yield Performance, and Fiber Quality in Three Cotton Hybrid Combinations

| Plant lines | Fresh weight(g) | ||||

| Plant | Roots | Stems | Leaves | Bolls | |

| GGK2 | 449.73±41.25a | 14.07±1.66a | 72.50±8.85a | 83.30±10.05a | 265.87±34.55a |

| XH | 330.00±34.48b | 13.74±2.46a | 65.03±6.11a | 59.43±6.99a | 182.80±19.70ab |

| GGK2×XH | 350.80±14.10ab | 17.03±1.53a | 65.47±4.84a | 84.57±7.81a | 173.73±2.32b |

| MPH | -10.02% | 22.53% | -4.80% | 18.50% | -22.56% |

| SPH | -22.00% | 21.09% | -9.70% | 1.52% | -34.65% |

| GGK2 | 449.73±41.25ab | 14.07±1.66a | 72.50±8.85a | 83.30±10.05b | 265.87±34.550a |

| Y4 | 355.37±33.93b | 15.80±2.35a | 60.43±7.80a | 58.73±11.18b | 210.73±16.71a |

| GGK2×Y4 | 608.13±84.09a | 21.07±3.61a | 95.17±14.40a | 159.90±22.26a | 314.67±44.72a |

| MPH | 51.07% | 41.07% | 43.18% | 125.16% | 32.05% |

| SPH | 35.22% | 33.33% | 31.26% | 91.96% | 18.36% |

| GGK2 | 449.73±41.25a | 14.07±1.66a | 72.50±8.85a | 83.30±10.05a | 265.87±34.55a |

| Y5 | 322.97±17.590b | 14.40±0.92a | 49.70±2.86a | 64.63±3.98a | 185.23±9.48a |

| GGK2×Y5 | 444.20±5.65a | 18.77±1.23a | 70.33±5.64a | 84.43±5.66a | 260.33±15.00a |

| MPH | 14.97% | 31.85% | 15.11% | 14.15% | 15.42% |

| SPH | -1.23% | 30.32% | -2.99% | 30.63% | -2.08% |

| Plant lines | Dry weight(g) | ||||

| Plants | Roots | Stems | Leaves | Bolls | |

| GGK2 | 100.83±8.22a | 4.39±0.59ab | 20.64±1.88a | 14.15±0.87ab | 61.65±6.54a |

| XH | 90.32±6.88a | 4.00±0.45b | 19.31±1.92a | 11.08±1.42b | 55.93±3.58a |

| GGK2×XH | 95.53±5.54a | 5.99±0.39a | 19.96±1.07a | 17.13±1.23a | 52.44±3.57a |

| MPH | -0.05% | 42.87% | -0.07% | 35.83% | -10.80% |

| SPH | -5.25% | 36.42% | -3.28% | 21.09% | -14.93% |

| GGK2 | 100.83±8.22b | 4.39±0.59a | 20.64±1.88ab | 14.15±0.87b | 61.65±6.54a |

| Y4 | 93.30±7.15b | 4.62±0.72a | 15.67±1.10b | 15.85±0.71b | 57.15±7.22a |

| GGK2×Y4 | 149.51±19.65a | 7.14±1.33a | 27.07±4.81a | 29.18±4.74a | 86.12±10.01a |

| MPH | 54.03% | 58.45% | 49.12% | 94.51% | 44.98% |

| SPH | 48.28% | 54.51% | 31.17% | 84.04% | 39.69% |

| GGK2 | 100.83±8.22a | 4.39±0.59a | 20.64±1.88a | 14.15±0.87b | 61.65±6.54a |

| Y5 | 92.58±4.27a | 4.82±0.25a | 17.28±1.03a | 14.04±1.27b | 56.45±2.64a |

| GGK2×Y5 | 115.40±8.19a | 5.92±0.75a | 22.57±2.02a | 18.56±0.87a | 68.36±5.72a |

| MPH | 19.34% | 31.72% | 15.76% | 28.48% | 19.03% |

| SPH | 14.46% | 22.84% | 9.33% | 31.22% | 10.88% |

| Plant lines |

Plant height (cm) |

Height of the first fruiting branch(cm) | Number of fruiting branches(a) | Number of cotton bolls(a) |

Stem diameter (mm) |

| GGK2 | 91.57±0.57b | 34.15±0.35c | 8.80±0.18b | 11.13±0.27ab | 10.02±0.15b |

| XH | 101.46±0.65a | 43.83±0.28a | 8.60±0.32b | 10.27±0.61b | 10.63±0.19a |

| GGK2×XH | 98.89±1.22a | 41.35±0.43b | 9.93±0.28a | 12.20±0.4a | 9.66±0.13b |

| MPH | 2.46% | 6.06% | 14.18% | 14.02% | -6.39% |

| SPH | -2.54% | -5.66% | 12.88% | 9.58% | -9.09% |

| GGK2 | 91.57±0.59a | 34.15±0.35a | 8.80±0.18b | 11.13±0.27a | 10.02±0.15b |

| Y4 | 91.23±0.93a | 32.85±0.51a | 9.60±0.19a | 11.47±0.44a | 10.69±0.18a |

| GGK2×Y4 | 82.62±0.96b | 28.69±0.51b | 8.27±0.21b | 10.40±0.34a | 10.12±0.23ab |

| MPH | -9.61% | -14.37% | -10.14% | -7.96% | -2.21% |

| SPH | -9.77% | -15.99% | -13.89% | -9.30% | -5.27% |

| GGK2 | 91.57±0.59a | 34.15±0.35a | 8.80±0.18b | 11.13±0.27ab | 10.02±0.15b |

| Y5 | 84.17±0.56b | 30.50±0.43b | 8.80±0.20b | 10.07±0.49b | 10.52±0.16b |

| GGK2×Y5 | 93.13±0.96a | 33.99±0.29a | 10.00±0.28a | 11.80±0.42a | 11.24±0.27a |

| MPH | 5.99% | 5.17% | 13.64% | 11.32% | 9.43% |

| SPH | 1.71% | -0.45% | 13.64% | 5.99% | 6.81% |

| Plant lines | No. bolls(plant-1) | Weight(plant-1) | Weight(boll-1) | Yeild (kg·ha-1) | Lint score (%) | Seed index(g) |

| GGK2 | 8.15±0.24b | 43.89±1.87a | 5.36±0.11a | 52.27±2.23a | 0.39±0.01a | 10.25±0.07b |

| XH | 7.95±0.30b | 42.32±1.66a | 5.35±0.14a | 50.40±1.97a | 0.39±0.01a | 11.15±0.08a |

| GGK2×XH | 9.9±0.60a | 45.59±2.81a | 4.62±0.11b | 54.30±3.35a | 0.37±0.01b | 10.88±0.15a |

| MPH | 22.98% | 5.77% | -13.67% | 5.77% | -4.94% | 1.65% |

| SPH | 21.47% | 3.87% | -13.74% | 3.87% | -4.85% | -2.42% |

| GGK2 | 8.15±0.24b | 43.89±1.87a | 5.36±0.11a | 52.27±2.23a | 0.39±0.01a | 10.25±0.07c |

| Y4 | 9.10±0.50ab | 46.83±2.07a | 5.21±0.10ab | 55.77±2.46a | 0.34±0.01b | 13.59±0.07a |

| GGK2×Y4 | 10.00±0.60a | 48.52±3.24a | 4.85±0.15b | 57.79±3.86a | 0.38±0.01a | 11.22±0.08c |

| MPH | 15.94% | 6.98% | -8.28% | 6.98% | 4.29% | -5.92% |

| SPH | 9.89% | 3.62% | -9.60% | 10.56% | -3.17% | -17.44% |

| GGK2 | 8.15±0.24a | 43.89±1.87a | 5.36±0.11a | 52.27±2.23a | 0.39±0.01a | 10.25±0.07c |

| Y5 | 8.55±0.37a | 44.75±1.64a | 5.29±0.12a | 53.30±1.96a | 0.34±0.01c | 12.76±0.11b |

| GGK2×Y5 | 8.45±0.34a | 43.41±1.55a | 5.16±0.08a | 51.71±1.85a | 0.36±0.01b | 11.09±0.05a |

| MPH | 1.20% | -2.04% | -3.03% | -2.05% | -2.83% | -3.61% |

| SPH | -1.17% | -2.99% | -3.73% | -1.08% | -9.64% | -13.09% |

| Plant lines |

Length (mm) |

Uniformity (%) |

Strength (cN/tex) |

Elongation (%) | Micronaire |

| GGK2 | 30.02±0.22b | 87.74±0.23a | 27.94±0.14b | 10.36±0.22b | 4.52±0.14ab |

| XH | 33.52±0.27a | 88.32±0.23a | 30.00±0.21a | 8.98±0.13a | 4.74±0.15a |

| GGK2×XH | 29.96±0.16b | 86.76±0.35b | 30.00±0.40a | 11.46±0.31c | 4.26±0.07b |

| MPH | -5.70% | -1.44% | 3.56% | 18.51% | -8.00% |

| SPH | -10.44% | -1.77% | 0.00% | 15.37% | -4.64% |

| GGK2 | 30.02±0.22b | 87.74±0.23a | 27.94±0.14a | 10.36±0.22a | 4.52±0.14a |

| Y4 | 32.44±0.36a | 87.96±0.44a | 27.98±0.34a | 10.44±0.30a | 4.60±0.20a |

| GGK2×Y4 | 30.36±0.32b | 86.76±0.48a | 26.68±0.42b | 10.86±0.21a | 4.94±0.12a |

| MPH | -2.78% | -1.24% | -4.58% | 4.42% | 8.33% |

| SPH | -6.41% | -1.36% | -4.65% | 4.02% | 7.39% |

| GGK2 | 30.02±0.22b | 87.74±0.23b | 27.94±0.14b | 10.36±0.22b | 4.52±0.14a |

| Y5 | 31.28±0.23a | 89.48±0.37a | 29.48±0.31a | 11.18±0.20a | 4.46±0.12a |

| GGK2×Y5 | 31.78±0.21a | 88.28±0.37b | 28.00±0.21b | 10.92±0.18ab | 4.82±0.14a |

| MPH | 3.69% | 0.37% | -2.47% | 1.39% | 7.35% |

| SPH | 1.60% | -1.34% | -5.02% | -2.33% | 6.64% |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.2.2. Seedling Herbicide Tolerance Assay

4.2.3. Chlorophyll Pigment Content and OJIP Fluorescence

4.2.4. Agronomic Traits, Yield Components, and Fiber Quality

4.2.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Aty, M. S.; Sorour, F. A.; Yehia, W. M. B.; Kotb, H. M. K.; Abdelghany, A. M.; Lamlom, S. F.; Shah, A. N.; Abdelsalam, N. R. Estimating the combining ability and genetic parameters for growth habit, yield, and fiber quality traits in some Egyptian cotton crosses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, H. Y.; Su, W. H. Automatic Localization of Soybean Seedlings Based on Crop Signaling and Multi-View Imaging. Sensors 2024, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M. Q.; Qu, M. H.; Wang, G.; Ma, Z. Y.; Chen, X. G.; Zhou, Z. H.; Qi, J. T.; Gao, X. M.; Li, H. L.; Jia, H. L. Crop detection technologies, mechanical weeding executive parts and working performance of intelligent mechanical weeding: a review. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 16, Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.; Thangaraj, M.; Krishna Radhika, N. CRISPR/Cas9: an advanced platform for root and tuber crops improvement. Frontiers in genome editing 2023, 5, 1242510, Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, L. E.; Pezeshki, R. Glyphosate in Runoff Waters and in the Root-Zone: A Review. Toxics 2015, 3, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Gomes, C.; Silva, T. L.; Andreani, T.; Silva, A. M. Glyphosate vs. Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Exposure: A Review on Their Toxicity. J Xenobiot 2022, 12, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achary, V. M. M.; Sheri, V.; Manna, M.; Panditi, V.; Borphukan, B.; Ram, B.; Agarwal, A.; Fartyal, D.; Teotia, D.; Masakapalli, S. K.; et al. Overexpression of improved EPSPS gene results in field level glyphosate tolerance and higher grain yield in rice. Plant Biotechnol J 2020, 18, 2504–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, S. O.; Carvalho, L. B. Unintended Effects of the Intended Herbicides on Transgenic Herbicide-Resistant Crops. Agronomy 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Z. P.; Perkin, L. C.; Wagner, T. A.; Liu, J. G.; Bell, A. A.; Arick, M. A., II; Grover, C. E.; Yu, J. Z.; Udall, J. A.; Suh, C. P. C. Nematode-resistance loci in upland cotton genomes are associated with structural differences. G3-Genes Genomes Genet. 2024, 14, 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L. B.; Zhao, S. Q.; Su, J. J.; Fan, S. L.; Pang, C. Y.; Wei, H. L.; Wang, H. T.; Gu, L. J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, G. Y.; et al. High-density genetic linkage map construction by F2 populations and QTL analysis of early-maturity traits in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Plos One 2017, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J. J.; Fan, S. L.; Li, L. B.; Wei, H. L.; Wang, C. X.; Wang, H. T.; Song, M. Z.; Zhang, C.; Gu, L. J.; Zhao, S. Q.; et al. Detection of Favorable QTL Alleles and Candidate Genes for Lint Percentage by GWAS in Chinese Upland Cotton. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, A.; Khan, M. K. R.; Haidar, S. Early-stage identification of heat-tolerant cotton genotypes under simulated episodic heat stress in controlled conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhu, J.; Huang, S.; Tian, E.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, D.; Tu, J.; Fu, T.; Meng, J. Broadening the avenue of intersubgenomic heterosis in oilseed Brassica. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2009, 120, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, A.; Bashir, S.; Rao, A. Q.; Shahid, A. A. Transformation of α-EXPA1 gene leads to an improved fibre quality in Gossypium hirsutum. Plant Breed. 2020, 139, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, K.; Nandiganti, M.; Thangaraj, A.; Singh, S.; Mishra, P.; Rathinam, M.; Sharma, M.; Singh, N. K.; Dash, P. K.; Sreevathsa, R. Transgenic Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) to Combat Weed Vagaries: Utility of an Apical Meristem-Targeted in plantaTransformation Strategy to Introgress a Modified CP4-EPSPS Gene for Glyphosate Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, A.; Rao, A. Q.; Ahmed, M.; Latif, A.; Bakhsh, A.; Iftikhar, S. The Increased aspartate levels in transgenic cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) lead to improved tolerance against whitefly (Bemisia tabaci, Gennadius). Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X. H.; Daud, M. K.; Sun, Y. Q.; Zhu, S. J. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of glyphosate tolerance in an in vitro selected cotton mutant. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2009, 94, 100-106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjar, R. S.; Sherin, S.; Batra, S.; Mahto, A.; Goswami, S. K.; Kumar, R.; Tiwari, R. K.; Singh, A.; Kumari, M. Emerging trends in the development of efficient CAS nucleases for meticulous gene editing in plants. Plant Sci 2026, 362, 112820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, A.; Du, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, K.; Liu, X.; et al. Foxtail millet (Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv) CIPKs are responsive to ABA and abiotic stresses. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0225091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Transgenic cotton: from biotransformation methods to agricultural application. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2013, 958, 3–15, Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. G.; Zhu, X. D.; Wang, C.; Shangguan, L. F. Applications of DNA Technologies in Agriculture. Curr. Genomics 2016, 17, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, L.; Malzahn, A.; Qi, Y. P. Rapid Evolution of Manifold CRISPR Systems for Plant Genome Editing. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 12, Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feke, A.; Liu, W.; Hong, J.; Li, M. W.; Lee, C. M.; Zhou, E. K.; Gendron, J. M. Decoys provide a scalable platform for the identification of plant E3 ubiquitin ligases that regulate circadian function. eLife 2019, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delporte, F.; Jacquemin, J.-M.; Masson, P.; Watillon, B. Insights into the regenerative property of plant cells and their receptivity to transgenesis: wheat as a research case study. Plant signaling & behavior 2012, 7, 1608–1620, Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.; Naeem, M.; Ashraf, M. Y.; Tahir, M. N.; Zulficiar, B.; Salahuddin, M.; Shabbir, R. N.; Aslam, M. Selenium Supplementation Affects Physiological and Biochemical Processes to Improve Fodder Yield and Quality of Maize (Zea mays L.) under Water Deficit Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M. Z.; Ling, N.; Tian, H. Y.; Guo, C. Q.; Wang, Q. Y. Toxicity, physiological response, and biosorption mechanism of Dunaliella salina to copper, lead, and cadmium. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hendawy, S.; Elsayed, S.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Alotaibi, M.; Tahir, M. U.; Mubushar, M.; Attia, A.; Hassan, W. M. Use of Hyperspectral Reflectance Sensing for Assessing Growth and Chlorophyll Content of Spring Wheat Grown under Simulated Saline Field Conditions. Plants-Basel 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, F.; Guo, S.; Lin, H.; Niu, L. Correction: Co-expression of GR79 EPSPSand GATgenerates high glyphosate-resistant alfalfa with low glyphosate residues. aBIOTECH 2024, 5 (1), 116, Published Erratum. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. Y.; Shi, J. Y.; Li, X. F.; Yang, M. L.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Yang, S.; Mei, C.; Luo, Z. Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Development and Breeding of Herbicide-Resistant Sorghum for Effective Cereal-Legume Intercropping. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkhuu, A.; Narasimhan, M. L.; Merzaban, J. S.; Bressan, R. A.; Weller, S.; Gehring, C. A red and far-red light receptor mutation confers resistance to the herbicide glyphosate. Plant J. 2014, 78, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazato, I.; Yamori, W.; Matsumura, H.; Qu, Y. C.; Okuno, M.; Tsutsumi, N.; Arimura, S. I. Resistance to the herbicide metribuzin conferred to Arabidopsis thaliana by targeted base editing of the chloroplast genome. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. C.; Hur, O. S.; Yoon, Y. M.; Lee, C. H.; Kim, S. M. Development of cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence marker for powdery mildew resistance in Korean malting barley using QTL-seq. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, M. J.; Hossain, M. R.; Park, J. I.; Robin, A. H. K.; Jesse, D. M. I.; Jung, H. J.; Kim, H. T.; Nou, I. S. Inheritance Pattern and Molecular Markers for Resistance to Blackleg Disease in Cabbage. Plants-Basel 2019, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Liu, J. H.; Ma, X.; Luo, D. X.; Gong, Z. H.; Lu, M. H. The Plant Heat Stress Transcription Factors (HSFs): Structure, Regulation, and Function in Response to Abiotic Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 13, Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X. H.; Song, L. L.; Yu, W. W.; Hu, Y. Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J. S.; Ying, Y. Q. Growth, physiological, and biochemical responses of Camptotheca acuminata seedlings to different light environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J. T.; Dong, Q. Q.; Lan, G. H.; He, Z. C.; Zhou, D. Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. G.; Liu, X. B.; Jiang, C. J.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Row ratio increasing improved light distribution, photosynthetic characteristics, and yield of peanut in the maize and peanut strip intercropping system. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. H.; Zhong, H. X.; Wang, J. F.; Sui, X.; Xu, N. Adaptive changes in chlorophyll content and photosynthetic features to low light in Physocarpus amurensis Maxim and Physocarpus opulifolius “Diabolo”. PeerJ 2016, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. H.; Qian, R. J.; Zhang, X. L.; Hu, Q. D.; Liu, H. J.; Zheng, J. Contrasting growth, physiological and gene expression responses of Clematis crassifolia and Clematis cadmia to different irradiance conditions. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyczylo-Mysza, I.; Tyrka, M.; Marcinska, I.; Skrzypek, E.; Karbarz, M.; Dziurka, M.; Hura, T.; Dziurka, K.; Quarrie, S. A. Quantitative trait loci for leaf chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, chlorophyll and carotenoid contents in relation to biomass and yield in bread wheat and their chromosome deletion bin assignments. Mol. Breed. 2013, 32, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. B.; Xu, J. L.; Zhang, W. H.; Amee, M.; Liu, D. L.; Chen, L. Salt-Induced Damage is Alleviated by Short-Term Pre-Cold Treatment in Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon). Plants-Basel 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Yu, H. J.; Li, Q.; Chai, L.; Jiang, W. J. Improving Plant Growth and Alleviating Photosynthetic Inhibition and Oxidative Stress From Low-Light Stress With Exogenous GR24 in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanov, M. A.; Rashkov, G. D.; Yotsova, E. K.; Borisova, P. B.; Dobrikova, A. G.; Apostolova, E. L. Different Sensitivity Levels of the Photosynthetic Apparatus in Zea mays L. and Sorghum bicolor L. under Salt Stress. Plants-Basel 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, W. W.; Wang, Y. Y.; Huang, Z. R.; Ye, X.; Chen, L. S.; Yang, L. T. Effects of phosphorus deficiency on the absorption of mineral nutrients, photosynthetic system performance and antioxidant metabolism in Citrus grandis. Plos One 2021, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.; Sujkowska-Rybkowska, M.; Gajc-Wolska, J.; Kowalczyk, W.; Borucki, W.; Kalaji, H. M.; Kowalczyk, K. Photosynthetic Efficiency and Anatomical Structure of Pepper Leaf (Capsicum annuum L.) Transplants Grown under High-Pressure Sodium (HPS) and Light-Emitting Diode (LED) Supplementary Lighting Systems. Plants-Basel 2021, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gu, Q. L.; Zhao, L. J.; Li, C. Y.; Ren, J. T.; Zhang, J. X. Photochemical Efficiency of Photosystem II in Inverted Leaves of Soybean Glycine max (L.) Merr. Affected by Elevated Temperature and High Light. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y. Y.; Wang, X.; Ding, B.; Xiao, M.; Qin, C. Effects of nitrogen addition on the growth and photosynthetic physiology of Gleditsia sinensis Lam. seedlings under shading conditions. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptist, F.; Tcherkez, G.; Aubert, S.; Pontailler, J. Y.; Choler, P.; Nogués, S. 13C and 15N allocations of two alpine species from early and late snowmelt locations reflect their different growth strategies. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 2725–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J. Q.; Li, R. Y.; Zou, J.; Long, Y.; Meng, J. L. A Dynamic and Complex Network Regulates the Heterosis of Yield-Correlated Traits in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Plos One 2011, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, B.; Tripathy, P.; Jyothsna, J.; Sahu, G. S.; Dash, S. K.; Badu, M.; Mahapatra, S. K.; Rout, G. R. Exploring heterosis, dominance effect, and genetic control in Brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) landraces. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X. L.; Qu, Y. J.; Jia, Y. H.; He, S. P.; Pan, Z. E.; Wang, L. R.; Du, X. M. Assessment of heterosis based on parental genetic distance estimated with SSR and SNP markers in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayele, A. G.; Dever, J. K.; Kelly, C. M.; Sheehan, M.; Morgan, V.; Payton, P. Responses of Upland Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Lines to Irrigated and Rainfed Conditions of Texas High Plains. Plants-Basel 2020, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J. L.; Gao, S. W.; Lin, Q. L.; Wang, H. B.; Que, Y. X.; Xu, L. P. Transgenic Sugarcane Resistant to Sorghum mosaic virus Based on Coat Protein Gene Silencing by RNA Interference. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).