1. Introduction

Plastics are being consumed at an accelerating rate worldwide, with global production projected to reach approximately 445.25 million metric tons by 2025 [

1]. The extensive use of plastic products has raised substantial concerns about the accumulation and persistence of plastic waste in the environment. Recent studies [

2] have identified a correlation between plastics and climate change, particularly highlighting how different polymer types contribute differently to greenhouse gas emissions throughout their life cycles.

The challenges associated with mitigating micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) stem not only from their diverse and often diffuse sources, including nonpoint inputs, but also from the absence of standardized analytical methods for detecting and characterizing MNPs. Additional barriers include insufficient regulatory frameworks, weak enforcement of existing policies, and limited public awareness—reflected in low willingness to reduce plastic consumption.

Emerging contaminants such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) exhibit strong adsorption to MPs, complicating their removal through advanced treatment technologies. Adsorption capacity varies by polymer type; for example, antibiotics, perfluoroalkyl compounds, and triclosan show particularly high sorption onto polyethylene (PE) and polystyrene (PS) MPs [

3].

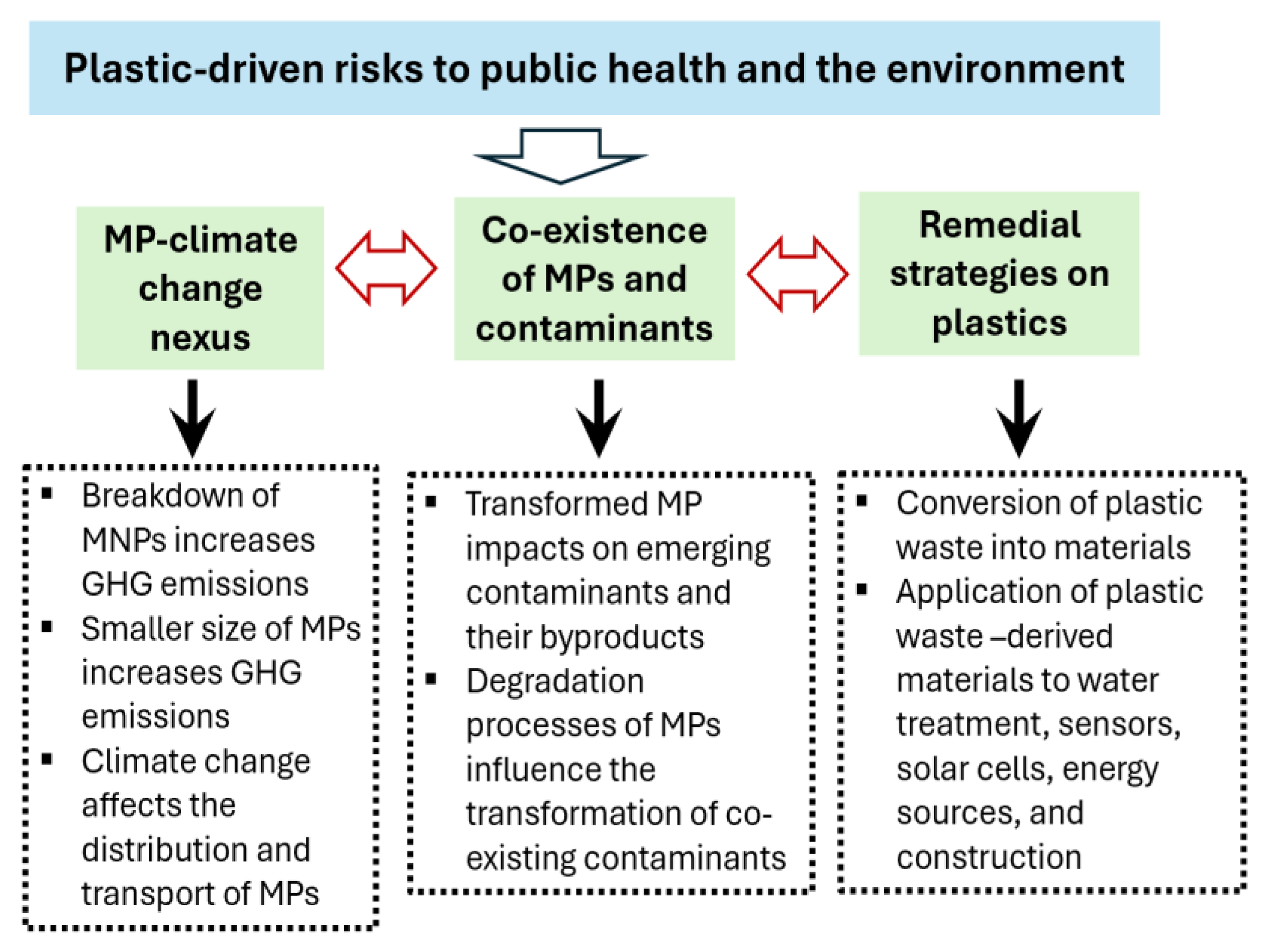

This review examines the interactions between MPs, climate change, and emerging contaminants, with particular emphasis on the role of transformed plastic polymers in sustaining recalcitrant pollutants. It also proposes strategies to mitigate these challenges, with the goal of reducing risks to public health and the environment.

2. Microplastic Effects on Climate Change

Life cycle assessments indicate that conventional plastics are significant contributors to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and are projected to account for up to 15% of the global carbon budget by 2050 [

4]. Several studies [

2,

5] have evaluated alternatives to conventional plastics or examined emissions associated with the production of polypropylene (PP) and mixed PP–PE– Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) products. Although sustainable substitutes—such as starch-based polymers—can reduce GHG emissions by 20–80%, depending on polymer type, they also present drawbacks related to chemical additives, limited durability, and recycling challenges [

2].

GHG emissions are highest during the polymer production stage, and emission intensity varies considerably by polymer type (e.g., PS >> PP ≈ Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) > High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE)). Regarding end-of-life pathways, among the four primary waste management strategies—recycling, incineration, landfilling, and gasification—incineration generates the largest amount of GHG emissions. This is followed by gasification, recycling, and, lastly, landfilling [

2,

6,

7].

Alternatives to conventional petrochemical plastics are increasingly being explored as strategies to mitigate life-cycle GHG emissions. A recent study [

2] identified four sustainable substitutes—starch-based polymers, polylactic acid (PLA) polyesters, polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polyesters, and polycaprolactone (PCL) polyesters—each offering distinct advantages and limitations. Starch-based polymers, PHA polyesters, and PCL polyesters demonstrated GHG emission reductions of up to 80%, whereas PLA polyesters achieved a more modest reduction of approximately 25%.

Starch-based polymers are appealing because of their biodegradability and low cost, but their use is limited by poor mechanical strength. PLA polyesters provide the benefit of carbon-neutral raw material sourcing; however, they require extended composting periods of two to three months and degrade more slowly in landfills than conventional plastics. PHA polyesters can degrade completely within 20 days under composting conditions using anaerobically digested sludge, though they exhibit reduced flexibility compared with petroleum-based plastics. Similarly, PCL polyesters fully degrade within approximately six weeks under composting conditions but have limited adaptability relative to PET and other aromatic polyesters.

During the environmental breakdown of micro-nanoplastics (MNPs), multiple pathways contribute to climate change. For instance, MNPs present in oceans, sea ice, and the plastisphere have been identified as significant sources of direct GHG emissions [

8]. The primary pathways include: (a) direct GHG release from degrading plastics, (b) reductions in sea ice influenced by MP accumulation and associated heat absorption, (c) GHG emissions generated by the plastisphere—microbial communities colonizing plastic surfaces, (d) disruption of the ocean’s carbon sequestration capacity, and (e) enhanced soil carbon release driven by MP-induced changes in enzyme activity [

8]. Notably, MPs generate more GHG emissions than larger plastic fragments due to their smaller size and greater surface area, and MPs in soil can further alter microbe-mediated GHG fluxes [

8].

With the continued accumulation of plastic waste and improper disposal practices—combined with the recalcitrant nature of plastics—the contribution of MPs to climate change is expected to intensify. Conversely, climate change also exerts a strong influence on MP distribution. Several recent studies [

2,

9] have demonstrated that climate change alters MP transport and fate through mechanisms such as disrupted ocean currents, rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and increased MP concentrations in natural environments. During extreme weather events, environmental pollution is amplified, leading to greater contamination of food and water sources with MPs. These interactions pose significant risks to both environmental integrity and public health.

A recent study [

10] investigated the fate of MPs under climate change and demonstrated that temperature, rainfall, drought, and wind all influence MP sinks across aquatic, glacial, and terrestrial environments. However, it remains unclear whether these climate-driven shifts will lead to MP redistribution or produce synergistic impacts on aquatic and soil organisms. The review [

10] also identified several climate-related MP degradation mechanisms—including those driven by wind and ocean currents, elevated temperatures, acid rain, and increased ultraviolet (UV) radiation—resulting in degradation through oxidation, thermal stress, freezing–thawing cycles, acidification, and UV exposure.

Concerns are growing regarding the role of MPs as vectors for contaminants, particularly emerging pollutants such as PFAS, especially because this vector pathway may also contribute to climate change. Despite this, relatively few studies have examined how MP–contaminant interactions influence climate processes. These interactions warrant greater attention, as they may pose substantial risks to both environmental ecosystems and public health.

Climate Change–Microplastic Nexus

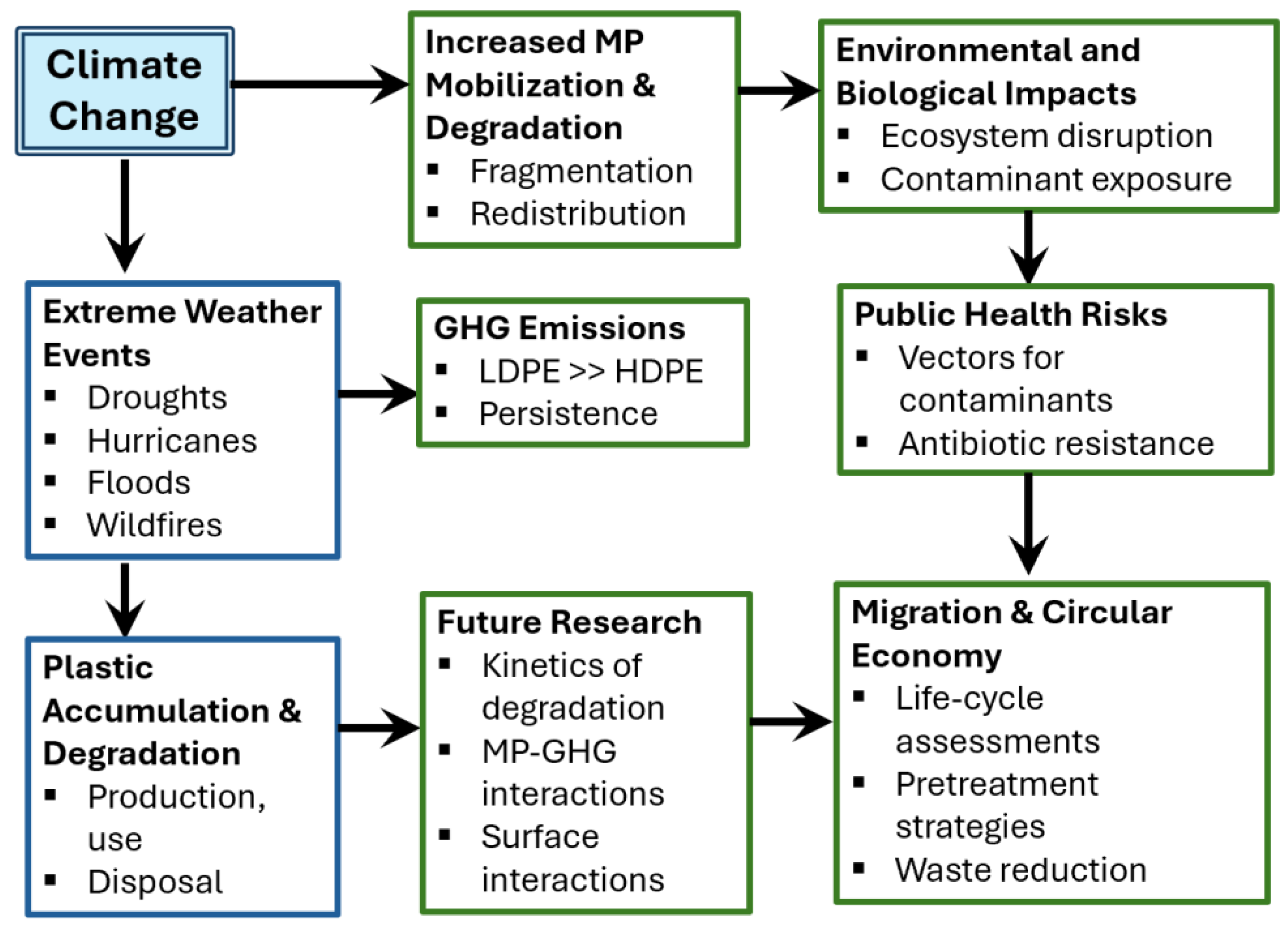

A growing body of research highlights a strong interconnection between climate change and MP pollution. Climate change serves as a major driver of MP accumulation by intensifying extreme weather events—such as droughts, hurricanes, floods, and wildfires—that enhance the mobilization, fragmentation, and redistribution of plastic debris. Additionally, climatic factors can alter the physicochemical properties of plastic particles, influencing their degradation pathways and environmental persistence.

Plastics accumulate across their life cycle through production, distribution, consumption, improper disposal, and gradual degradation into secondary microplastic and nanoplastic byproducts. Structural changes occurring during degradation can affect the release of GHG emissions. For example, Ford et al. (2022) [

11] reported that LDPE emits higher levels of GHGs during degradation than HDPE. Particularly concerning is the accumulation of plastics in marine environments, where ingestion by marine organisms disrupts physiological processes, food web dynamics, and ecosystem functions. These disruptions diminish the ocean’s capacity to function as a carbon sink, thereby exacerbating climate change [

12].

Despite growing evidence of these linkages, the environmental feedbacks between plastic pollution and climate change remain insufficiently understood, highlighting the need for mechanistic studies on the biogeochemical consequences of plastic accumulation in both marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Extreme weather events associated with climate change influence plastic pollution by modifying the distribution and concentration of plastic contaminants, including substances adsorbed onto plastic surfaces, via pathways such as disrupted ocean currents, elevated temperatures, and increased MP concentrations. The combined effects of climate change and MP pollution have particularly harmful impacts on ecosystems, affecting interactions among marine sediments, seawater, and resident biota [

13].

Mitigation of MP pollution is most effective when terrestrial inputs are reduced, as climate-driven processes—such as flooding—can substantially elevate MP concentrations. For instance, a recent study [

14] reported an approximately 40% increase in average MP concentrations in both seawater and sediments following typhoon events. The nexus between climate change and MP pollution warrants further investigation, particularly regarding ecosystem-level impacts and the development of remedial strategies, given MPs’ potential synergistic role as vectors for environmental contaminants.

In terms of future prospects, governments, in collaboration with the public and industry, should invest substantially in research and development (R&D) to address critical issues such as climate-driven increases in GHG emissions and elevated MP concentrations resulting from extreme weather events. Further studies are needed to characterize MP properties and their ecological impacts during degradation under varying climatic conditions. The potential synergistic role of MPs as vectors for contaminants also warrants closer examination, particularly regarding surface interactions and environmental factors that influence them. As plastics degrade, the pathways and extent of degradation can affect GHG emissions, while GHG dynamics may, in turn, influence degradation processes. However, research on these interdependencies remains limited. Investigating the kinetics of plastic polymer degradation alongside GHG emissions across diverse climatic scenarios is essential to understand the persistence and environmental impacts of plastics more comprehensively.

Moreover, as discussed previously, climate change affects the distribution of plastics, influencing their resuspension across environmental media. While emerging contaminants such as ARB associated with MPs are addressed in the following section, preventing and mitigating antibiotic resistance (AR) within microbial communities on plastic surfaces is critical to protecting both public health and the environment. Given that the adverse impacts of MPs are closely linked to their physicochemical properties, further research is needed to examine the relationship between MP characteristics and GHG emissions. From a circular economy perspective, comprehensive life-cycle assessments of plastics—from raw material extraction to disposal—are essential, alongside studies on pretreatment strategies for both conventional and alternative plastics. Such strategies could enable the efficient degradation of plastics, whether biodegradable or non-biodegradable, in natural environments or under controlled industrial conditions.

Figure 1 shows how MPs, climate change, and their impacts are interconnected and highlights key research and mitigation priorities.

3. Transformation of Plastic Polymers on Emerging Contaminants

Plastic polymers degrade under various climatic factors. However, it remains unclear whether the transformation of these polymers influences emerging contaminants adsorbed onto MPs, as MPs function as vectors for contaminant transport. One such emerging contaminant is PFAS, which pose significant challenges for treating wastewater and waste streams due to their recalcitrant nature. While landfill leachate contains a broad range of contaminants, recently evolving pollutants—including PFAS, pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), and MPs—have received increasing attention regarding their quantification, remediation strategies, occurrence, frequency, and the role of climatic factors in shaping their composition, degradation, and treatment processes.

The coexistence of MPs with other contaminants has been shown to affect multiple human organs, including the brain, heart, liver, thyroid, and lungs [

15]. As contaminants transform into byproducts—whose toxicity may vary depending on climatic and environmental conditions—transformed MPs can exert significant impacts on ecosystems through physicochemical or biological interactions with these contaminants or their byproducts. Addressing these challenges requires innovative approaches and solutions supported by multidisciplinary research and expertise.

Given that MPs transport other contaminants through their physicochemical properties—such as hydrophobicity—degradation processes, including weathering and adsorption, can influence the transformation of adsorbed contaminants. A recent study [

3] examined degradation mechanisms and factors affecting contaminant adsorption on MPs. Among commonly studied plastic polymers, PE and PS exhibited high adsorption capacities for antibiotics, perfluoroalkyl compounds, and triclosan [

3]. In the presence of multiple contaminants, interaction effects—whether incremental, additive, synergistic, or antagonistic—can occur. These effects are influenced by factors such as the physicochemical properties of the plastic polymers, including particle size, surface roughness, morphology, and functional groups, as well as prevailing climatic conditions [

3,

18].

Several factors influence the sorption of contaminants onto MPs, as noted in a recent study [

3]. These include weathering processes—affected by crystallinity, particle size, age, shape, and color—as well as the physicochemical properties of the polymer (e.g., polarity, pKa) and environmental conditions such as pH, salinity, temperature, dissolved organic matter, and UV exposure. Among common plastic polymers, polyamide (PA) shows the highest sorption of polar contaminants, including antibiotics and Bisphenol A, compared with PS, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and PP [

3]. As plastics undergo natural aging, their sorption capacity and associated toxicity are expected to change over time. Although the co-occurrence of MPs and contaminants has been increasingly investigated, findings remain inconsistent due to limited data across diverse MP types and environmental conditions. The lack of standardized analytical methods and sampling protocols for MPs further complicates the assessment of co-existence and the resulting interaction effects in soil, water, and living organisms.

In a recent study, Zhu et al. (2025) [

16] examined the fate of MPs in soil–water systems in relation to ecological and human-health risks, with particular attention to the mechanisms driving MP degradation. Reactive oxygen species (e.g., O₂•⁻, H₂O₂, ROO•) formed at the soil–water–air interface are highly reactive and play a critical role in determining MP fate. Because climate change influences the formation and activity of these reactive species, it can alter MP transformation processes.

However, knowledge of the underlying mechanisms, reaction kinetics, and transformation pathways of MPs—especially their effects on the behavior of co-existing contaminants—remains limited. Climatic factors such as drought, extreme precipitation, and elevated temperatures modify dissolved oxygen levels, pollutant leaching, soil microbial activity, soil organic matter, and clay mineral interactions. These changes can lead to either increased or decreased free radical production, thereby accelerating or slowing MP degradation [

16]. Such variations also influence degradation pathways and byproduct formation by altering MP physicochemical properties. In addition, climatic conditions including strong winds, heat waves, and precipitation events affect the transport and spatial distribution of MPs across environmental media [

12,

16].

Key challenges that remain include understanding the long-term persistence of free radicals, determining the fate of MP degradation byproducts, characterizing MP migration within environmental systems, assessing the influence of climatic factors on MP removal processes, developing strategies to mitigate MP-related risks, and evaluating MP toxicity under changing climate conditions [

16]. Recent research on microplastic-associated AR [

17,

18] indicates that MPs serve as hotspots that facilitate AR development, posing an increasing threat to public health. AR is largely driven by interactions between MPs and environmental conditions, particularly climate change and co-existing contaminants. Critical drivers include the large surface area of MPs, which promotes biofilm formation—a process intensified by extreme climate-related events. Additionally, contaminants such as heavy metals and organic pollutants (e.g., pesticides, non-antibiotic pharmaceuticals) further promote AR through mechanisms such as co-resistance, cross-resistance, and horizontal gene transfer [

17].

As antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), pathogens, and contaminants enter the water column, MPs interact with them and facilitate biofilm formation, contributing to the development of the plastisphere. At the cellular level, three key processes occur: bacterial colonization of MP surfaces, shifts in microbial community composition, and the transport of pathogenic bacteria. Resistance mechanisms emerge through the enrichment of antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs) and the proliferation of resistant strains [

17]. Together, these processes heighten ecological risks through complex environmental interactions and increase the persistence and resilience of bacterial communities [

17].

Among the various contributors to pollution, environmental sources of MP contamination include high-risk pollutants—such as organic contaminants, antibiotics, heavy metals, and pesticides—as well as bacterial communities, including ARB carriers (e.g.,

E. coli,

Pseudomonas,

Actinobacteria) and pathogenic species (e.g.,

Vibrio spp.,

Salmonella) [

17]. MPs exposed to these pollutants and microbial communities are subsequently released into environmental media such as aquatic systems (freshwater, marine environments, sediments) and agricultural settings (surface soils, farming areas). Their presence in these pathways poses public health risks through exposure routes including inhalation, dermal contact, and ingestion of contaminated food.

Several studies have demonstrated that climate change and plastic pollution are interconnected, jointly contributing to the emergence of new contaminants—particularly the evolution of AR associated with MPs. However, limited research has explored the mechanisms underlying the persistence of contaminants generated from climate-driven MP transformations, as well as their effects on ecosystems and soil microbial communities. Addressing this knowledge gap is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies within the climate change–microplastic nexus.

4. Remedial Strategies for Plastics in Tackling Public Health Challenges

Recent studies highlight a range of remedial approaches for managing plastic waste, including its conversion into activated carbon, green energy, wood–plastic composite materials, and construction bricks [

19,

20,

21,

22]. This section outlines the role of plastic-waste valorization as part of broader mitigation strategies and discusses the associated challenges in reducing risks to public health and the environment.

Plastic waste presents an increasingly serious problem due to the toxicity of microplastic particles, their capacity to adsorb harmful contaminants, and the lack of effective disposal methods to prevent long-term environmental and health impacts. In response, efforts are underway to convert plastic waste into value-added materials that can be used for wastewater remediation. Because most plastic waste ultimately accumulates in landfills—and considering both the limited availability of landfill space and the high costs of disposal—circular-economy approaches are being advocated to reduce waste burdens and facilitate the treatment of contaminants associated with discarded plastics.

One promising approach involves producing activated carbon from plastic waste. Activated carbons generated from plastic-waste-derived chars have shown surface areas ranging from 0.2 to 2,152 m²/g, exhibiting strong performance in removing emerging contaminants of concern, although their capacity for heavy metal removal is generally lower [

19]. Additional research is needed to address limitations such as potential leaching, limited reusability, and production costs. Carbon-based materials produced from plastic-waste feedstocks have broad applications, including water treatment, sensors, solar cells, energy storage, electrochemical devices, and membrane separation technologies [

19].

The efficiency of contaminant removal by activated carbon derived from plastic waste depends on environmental conditions and the extraction methods employed. Factors such as initial pH, contaminant concentration, temperature, and contact time should be carefully evaluated to optimize performance. From a circular economy perspective, converting plastic waste into activated carbon is a recommended strategy. In a recent study, plastic waste was also explored as a feedstock for green energy production [

20]. This approach offers an environmentally sustainable solution, simultaneously reducing the burden of plastic pollution. Plastic waste-derived carbon materials (PWCMs) demonstrate high specific surface area, structural stability, and versatile surface chemistry, making them suitable for a range of applications [

20].

The study demonstrated that PWCMs are effective in removing emerging contaminants, including antibiotics, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), endocrine-disrupting chemicals, heavy metals, and anions. Beyond wastewater treatment, PWCMs also show potential for CO₂ adsorption, contributing to global warming mitigation and sustainability. The CO₂ capture process involves pyrolysis and carbonization, which activate the materials for carbon-based applications. Overall, PWCMs offer a low-cost, eco-friendly, and high-performance alternative to coal, supporting sustainable green energy initiatives.

However, upcycling plastic waste still requires further investigation, particularly in evaluating its applications, optimizing processes, and assessing limitations with an emphasis on cost-effective and environmentally sustainable approaches. The negative impacts of plastic waste worsen over time due to the accumulation of MPs, the lack of standardized methods for their analysis and quantification, and the inadequacy of traditional treatment methods, such as incineration and landfilling, to address associated contaminants. These factors exacerbate environmental harm by releasing toxic pollutants and additives from degrading plastics, disrupting ecosystems, and posing significant risks to public health.

An alternative approach involves using plastic waste to produce wood–plastic composite products for construction, with higher proportions of recycled plastic [

21]. However, incorporating plastic waste into construction bricks has been linked to occupational health and environmental risks [

22]. Few studies have thoroughly assessed the human and environmental hazards associated with brick production from plastic waste. The manufacturing process—including collection, sorting, washing, drying, shredding, melting or extrusion, cooling, and molding—can release air pollutants such as heavy metals, organic compounds, particulate matter, and volatile contaminants, posing risks to workers [

22]. Microplastics are widely present not only in water but also in soils and sediments. Therefore, analyzing and characterizing emissions from the production of plastic-based products or the processing of recyclable and non-recyclable waste is essential, given the potential hazards throughout the plastic life cycle.

Small-scale recycling plants that produce bricks from plastic waste appear to be both economical and effective, particularly in communities or countries with limited disposal infrastructure. However, few studies have evaluated potential occupational hazards, environmental impacts, and pollutant accumulation across the plastic life cycle, especially during the manufacture of products from recyclable and non-recyclable waste. Future research should focus on process optimization to minimize pollutant release and on characterizing the types and concentrations of pollutants and GHG emissions generated during plastic product manufacturing.

Notably, micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) have also been detected in food products. Wang et al. (2023) [

23] investigated MNPs in food systems, examining their formation, composition, and impacts on food production, processing, and consumption. While MNP detection is well established, information on their distribution, toxicity in combination with environmental contaminants, and remedial approaches remains limited. MNPs can accumulate in the human body through ingestion, dermal contact, or inhalation, resulting in combined toxicity from associated contaminants, including antibiotics, PAHs, pesticides, herbicides, pathogenic bacteria, and heavy metals. Such combined toxicity may arise from additive, synergistic, antagonistic, or potentiating effects [

23].

Various remedial approaches have been proposed for MNPs, including filtration (direct and multistage), physico-chemical precipitation, adsorption, and degradation methods such as photocatalysis and biodegradation. However, significant challenges remain, including the need for efficient and cost-effective remediation techniques, rapid and reliable field detection methods, toxicity assessment of co-existing contaminants under climatic influences, development of biodegradable plastics as alternatives to conventional plastics, removal strategies for both non-biodegradable and biodegradable plastics, and the advancement of enzymes or microbes capable of degrading plastics.

Table 1 summarizes the remedial strategies for plastic waste, along with their benefits and the associated challenges for public health.

Remedial Strategies for Addressing MPs in Waterways

Climate change–driven storms have contributed significantly to MP pollution, particularly in urban stormwater systems, where MPs are increasingly detected—most notably from tire wear particles [

25]. Friction between tires and pavement generates these particles, which accumulate on road surfaces and are subsequently washed into stormwater systems during rainfall events, degrading water quality and impacting aquatic ecosystems. Wolfand et al. (2023) [

25] reported that a substantial portion of MP pollution originates from urban stormwater. However, many existing stormwater management systems lack the infrastructure to effectively capture and filter MPs before they are discharged into rivers and lakes. This deficiency poses risks to both environmental and human health, as MPs can persist in the environment, bioaccumulate through aquatic food webs, and potentially contaminate drinking water sources [

26].

To mitigate MP pollution in urban stormwater, three filtration systems—bioretention cells, sand filtration, and constructed wetland filtration—have been evaluated based on cost, environmental impact, maintenance requirements, removal efficiency, social acceptability, and land use [

27]. These systems are essential for preventing MPs and other pollutants from entering larger water bodies, including rivers and oceans, thereby promoting cleaner and healthier aquatic ecosystems.

Bioretention cells are shallow depressions filled with media such as sand, compost, soil, or proprietary mixtures, typically covered with vegetation or mulch [

28]. Runoff water infiltrates the surface, is filtered through the media, and the treated water is conveyed to a stormwater drainage system. Sand filtration, a widely applied method, directs water through a sand layer that traps pollutants. Recent studies have shown that MP removal rates of up to 99% can be achieved using a horizontal flow design, in which water flows laterally across the sand bed rather than vertically, allowing MPs to be retained within the sand and removed during maintenance [

29].

Constructed wetlands (CWs) are engineered systems designed to mimic the functions of natural wetlands, removing substantial amounts of pollutants from water primarily through plant uptake and contaminant retention. Among the three stormwater filtration systems, CWs offer several advantages, including high efficiency in MP removal and support for biodiversity. In comparison, sand filters can be costly and require frequent maintenance, while bioretention cells demand more land and may encounter long-term soil issues. Consequently, CWs provide an effective balance between performance and practicality. These systems represent a sustainable and eco-friendly approach, employing layers of soil, sand, and vegetation to naturally filter stormwater.

Additional features, such as trash-capture devices and sponge-based technologies, can further enhance the ability of CWs to remove smaller plastic particles [

27]. Regular dredging prevents the accumulation of sediments, MPs, and other pollutants, while ongoing plant monitoring and replacement ensure that trapped plastics are not re-released into the environment.

Beyond improving water quality, CWs contribute to urban resilience by mitigating flooding, reducing pollution, creating green spaces, and enhancing residents’ quality of life. They also offer educational opportunities that emphasize the importance of environmental protection. The development and integration of such filtration systems into urban drainage infrastructure are therefore critical for safeguarding water quality and promoting healthier ecosystems in the face of increasing global plastic production and pollution.

Despite the notable advantages of CWs over other filtration systems, several challenges remain. These include the absence of standardized methods for detecting and analyzing MPs, limited understanding of system lifespan and maintenance needs (e.g., dredging, plant and sponge replacement), uncertainties regarding risk mitigation and plastic recycling, questions about the long-term efficacy of CW treatment, and potential adverse effects on humans, animals, and the environment.