1. Introduction

Modern soccer demands that players perform repeated explosive actions, such as sprints, jumps, changes of direction, and physical duels [

1]. These qualities are important for soccer performance, particularly during decisive phases of a match, where speed and power often determine the outcome [

2]. In this context, warm-up represents an essential component of athletic preparation, aimed at reducing injury risk while optimizing immediate performance [

3,

4,

5].

Traditionally, warm-ups include a general phase (light jogging, joint mobility) and a specific phase involving ball exercises [

6]. Many coaches prefer to include a rondo in the final stage of the warm-up, as it stimulates reactivity, coordination, and passing speed under pressure [

7,

8,

9]. This drill also enhances decision-making and perception-action coupling, providing a dynamic and engaging warm-up that mimics match demands [

7]. However, these approaches may be limited in terms of neuromuscular activation, especially for preparing players for explosive efforts. Recently, activation strategies have been proposed, which involve integrating strength or power exercises into the final phase of the warm-up to exploit the post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) phenomenon, characterized by transient improvements in muscular performance following a conditioning exercise [

10,

11].

Among these strategies, squat exercises are particularly relevant, as they target the main muscles involved in jumping and sprinting tasks [

12,

13]. The squat is a fundamental multi-joint movement for developing lower-limb power and explosive strength, qualities directly associated with soccer-specific actions, including short-distance sprints, vertical and horizontal jumps, and agility-based movements [

14,

15]. Although resistance training and plyometric programs have been extensively studied in soccer [

16], the strategic integration of squat exercises into the final phase of warm-up remains underexplored, especially in youth players.

Previous studies indicate that incorporating heavy or explosive squats can enhance sprint and jump performance in trained athletes [

14,

17]. However, most of these studies were conducted under specific experimental conditions, sometimes far removed from the real context of collective soccer warm-ups. In youth soccer players, evidence remains limited and inconsistent. Some studies suggest that squat-induced activation can improve speed and explosive strength [

17,

18], while others report no significant effects, potentially due to differences in load, player experience, or recovery intervals [

19].

Therefore, it is essential to assess the practical effectiveness of integrating squat exercises into the final phase of warm-up compared to traditional technical drills, such as the widely used “rondo”. The aim of this study was to examine the long-term effects of including squat exercises into the final phase of the warm-up on sprinting, jumping, agility, and aerobic performance in young soccer players. We hypothesized that a squat-based warm-up would lead to greater improvements in sprint, jump, and agility performance than a rondo-based warm-up, while no significant difference would be observed in aerobic performance between the two programs. By comparing these two approaches over a nine-week intervention, this study also seeks to provide practical recommendations for optimizing warm-up strategies in youth soccer training.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

Before recruiting participants, a sample size calculation was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7, University of Kiel, Germany) based on a repeated-measures ANOVA design with within–between interaction [

20]. Effect sizes used for the calculation were drawn from preliminary data on the effects of squat exercises versus rondo drills on sprint and jump performance in young male soccer players [

21]. The analysis indicated that a minimum of 24 participants (effect size f = 0.35, statistical power = 82%) was required to detect significant group × time interactions, assuming a Type I error rate of 0.05 and a Type II error rate of 0.18. Ideally, a few more participants would have been recruited to account for possible dropouts; however, all 24 male youth soccer players (under-17 category) from the same team who were recruited finished the study, so there were no dropouts and the necessary statistical power was maintained. To account for potential dropout, 24 male youth soccer players (under-17 category) from the same regional training academy were recruited. Participants were classified according to their playing positions (central defender, full-back, midfielder, and forward), with goalkeepers excluded due to their distinct training regimens. For their regular training, players participated in five training sessions and in one match per week. To minimize any bias associated with position-specific physical demands, player positions were carefully considered during randomization, ensuring that each group (experimental and control) had an equal representation of positions. Players were then randomly assigned to the experimental group: EG (n = 12; age = 17.1 ± 0.6 years, height = 174.3 ± 5.8 cm, body mass = 66.5 ± 6.7 kg, soccer experience = 6.2 ± 1.1 years) or the control group: CG (n = 12; age = 17.0 ± 0.7 years, height = 173.6 ± 6.1 cm, body mass = 65.8 ± 7.1 kg, soccer experience = 6.0 ± 1.3 years) using a coin toss.

Consistently with a random assignment of two groups, no significant differences between groups were found at baseline for age, height, body mass, and training experience (p > 0.05 by independent t-test). The inclusion criteria were: (i) all participants were members of the same team; (ii) none of the players had experienced any illness or injury during the eight weeks preceding and throughout the experimental period; (iii) have previous experience with the squat exercise (iv) no physical or cognitive disorders were reported; and (v) participants consistently attended training sessions.

To ensure fair and unbiased allocation, the randomization process was overseen by a blinded assessor not involved in testing. All participants and their legal guardians provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics committee of the High Institute of Sports and Physical Education in Kef (ISSEPK-0036/2024, 01 December 2024).

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the participants.

Experimental Procedure

The study was conducted over an eleven-week period, including a pre-test week, nine weeks of training, and a post-test week. Prior to the intervention, participants’ anthropometric characteristics and The one-repetition maximum (1-RM) was assessed. The 1-RM was estimated using a submaximal squat test, in which participants performed progressively heavier loads until reaching a weight they could lift for 4–6 repetitions with correct technique, then calculated using the Brzycki formula. This gave the progressive load prescription a secure and trustworthy starting point. During the intervention period, the EG added targeted squat exercises at the end of the warm-up twice weekly to induce a post-activation potentiation (PAP) effect and enhance neuromuscular readiness [

10,

22]. The CG, under the same time conditions, performed a 4v2 rondo drill [

23] focused on ball retention and reactivity, without the execution of any resistance training exercise. Both groups then completed the same regular soccer training program, ensuring equal overall training volume and load. This design isolated the specific contribution of each warm-up modality to performance adaptations.

Performance assessments were conducted before and after the intervention using validated tests for youth soccer players: 10 m and 30 m sprints, standing long jump (SLJ), five-jump test (5JT), squat jump (SJ), countermovement jump (CMJ), T-half agility test, and the VAMEVAL test. Each participant completed two maximal trials per test (10 m, 30 m, SLJ, 5JT, SJ, CMJ) with three minutes of passive recovery, and the best performance was recorded. Testing sessions were standardized, with consistent verbal encouragement, and all measurements were taken on the same synthetic pitch between 16:30 and 17:00 to control for circadian influences [

24]. A familiarization session was conducted beforehand to minimize learning effects. Rating of perceived exertion (RPE) was collected after each intervention to assess internal intensity [

25].

The nine-week training program consisted of five weekly sessions during the competitive season, with each session beginning with a standardized warm-up divided into three phases: a 8-minute general phase including light jogging, joint mobility exercises, and dynamic stretching; a 8-minute specific phase with coordination and acceleration drills using the ball; and a 10–12 minute final phase consisting of intervention-specific exercises, either squat-based (EG) or rondo-based (CG) (

Table 2).

The experimental intervention was performed twice weekly during the final warm-up phase. For the EG, the warm-up included a structured squat protocol integrated into the final phase, aimed at progressively activating the lower limbs and preparing players for explosive actions. Intensity progressed during the course of the nine weeks from 50% to 85% of 1-RM following the principle of progressive overload. Each session included 3–4 sets of 4–12 repetitions at a 2-0-1 tempo (2 seconds eccentric, 0-second pause, 1 second concentric explosive) with 2–3 minutes of rest between sets [

26]. In this exercise, the players started from an upright standing position with full extension of the hips and knees, while the barbell was positioned across the upper back at the level of the acromion. They then performed the downward phase until the thighs went below a 90° angle, followed by the upward phase to return to the starting position [

27].

To ensure smooth organization and avoid time loss, four squat stations were set up along the sideline of the football pitch. Each station included a barbell and a rack placed at shoulder height, with a distance of two meters between stations. The first four players performed the exercise simultaneously, followed by the next four, and so on, until all participants completed their sets. All players followed the same recovery time between sets to standardize the training conditions.

The CG performed a 4v2 rondo drill emphasizing ball retention and rapid short movements [

23], while both groups continued their regular football training to maintain equal overall training volume (

Table 3). Participants were instructed to maintain regular sleep patterns and avoid strenuous physical activity the day before testing to minimize fatigue.

The internal training load was assessed immediately after the squat exercises (EG) or rondo drills (CG) performed during the final phase of the warm-up. The Borg CR-10 RPE scale was used to measure the perceived effort associated with each session [

25]. This method has been previously shown to be valid and reliable for quantifying internal load in soccer contexts [

28]. To ensure accurate responses, all participants were familiarized with the RPE scale prior to the intervention

Sprint performance was assessed over 10 m and 30 m on a synthetic grass pitch. Each participant performed two maximal 30-m sprints, with split times recorded at 10 m [

29]. To guarantee uniformity and minimize any order effects, all tests were administered to each participant in the same standardized order before and after the intervention. A passive recovery period of three minutes was provided between each sprint to minimize fatigue. Sprint times were recorded using electronic timing gates (Globus, Microgate, Italy) to ensure precision. For data analysis, the fastest 30-m sprint of the three trials was retained. Test reliability was excellent, with an ICC of 0.92 and CV of 2.1% for the 10-m sprint, and an ICC of 0.93 and CV of 1.9% for the 30-m sprint.

Horizontal jump performance was assessed using the standing long jump (SLJ) and the five-jump test (5JT). In the SLJ, participants jumped forward as far as possible from a standing position with feet together, landing with both feet. In the 5JT, participants performed five consecutive horizontal jumps, emphasizing maximal distance and proper landing mechanics. Two trials were conducted for each test with three minutes of passive recovery, and the best performance was recorded. Reliability indices were: SLJ – ICC = 0.88, CV = 3.0%; 5JT – ICC = 0.89, CV = 2.7%.

Vertical jump performance was evaluated using the squat jump (SJ) and countermovement jump (CMJ) [

30]. Prior to the assessment, participants executed 2–3 self-paced submaximal CMJs and SJs to familiarize themselves with the testing procedures and to ensure adequate specific warm-up. During all trials, players were instructed to place their hands on their hips to eliminate the contribution of arm swing and minimize coordination effects, thereby isolating lower-limb extensor performance [

30].

For the SJ, participants adopted a static semi-squat position with knees flexed at approximately 90° and performed a vertical jump without any preparatory movement. For the CMJ, they completed a rapid downward movement immediately followed by a forceful upward jump. Each participant performed two maximal attempts for both SJ and CMJ, with approximately two minutes of passive recovery between trials. The best performance was retained for analysis. The tests demonstrated high reliability (SJ: ICC = 0.90, CV = 2.5%; CMJ: ICC = 0.91, CV = 2.3%).

Agility was assessed using the T-half agility test, which measures multidirectional change-of-direction ability [

31]. Participants sprinted, shuffled, and backpedaled along a T-shaped course as quickly as possible. Two trials were performed with three minutes of passive recovery, and the best trial was retained for analysis. Reliability for the test was ICC = 0.87, CV = 2.8%.

Aerobic capacity was assessed using the VAMEVAL test, which provides a reliable measure of maximal aerobic speed (MAS) [

32]. The Vameval test was performed on a 200-m running track. The course was marked with ten cones placed at 20-m intervals, and participants followed a pre-programmed auditory signal (beep) to guide their running pace. The test began at a speed of 8 km·h⁻¹, which was increased by 0.5 km·h⁻¹ every minute until the participant reached exhaustion. Participants were responsible for maintaining their running pattern between the cones. The test ended when a participant was unable to reach the next cone in time with the beep on two consecutive occasions or voluntarily stopped due to fatigue [

32]. The highest speed successfully maintained before exhaustion was recorded as the MAS.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). Normality of distribution was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was checked with Levene’s test. To examine the effects of the intervention, a mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for each physical performance variable, including time (pre vs. post) as within-subject factor and group (EG and CG) as between-subject factor. When significant main effects or interactions were detected, Bonferroni post hoc tests were applied to identify pairwise differences between pre- and post-test values within and between groups.

Effect sizes were calculated using partial eta squared (η²p) for the ANOVA and interpreted according to Cohen’s guidelines as small (0.01), medium (0.06), or large (0.14) [

33]. Additionally, within-group changes were quantified using percentage change (Δ%) and Cohen’s d, with effect sizes classified as trivial (<0.2), small (0.2–0.5), moderate (0.5–0.8), or large (>0.8) [

34].

Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), was analyzed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test for each training session, comparing the experimental (EG) and control (CG) groups.

Statistical significance was set at p ˂ 0.05.

3. Results

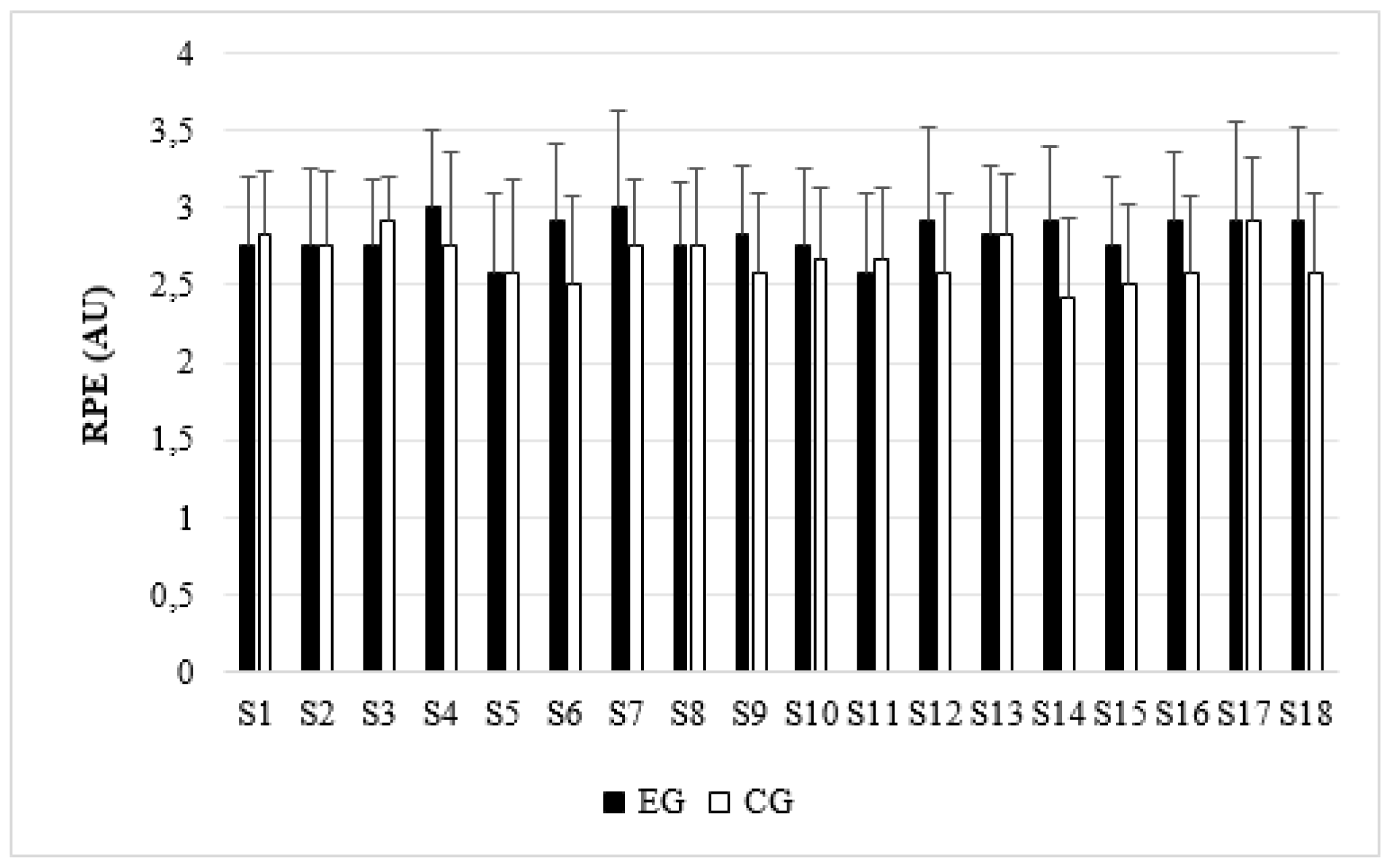

RPE scores were recorded across 18 training sessions. Mann–Whitney U tests showed that RPE values were generally similar between the experimental and control groups throughout the intervention (

Table 4). For all other sessions, (p˂0.05), indicating comparable perceived effort between groups.

Figure 1 illustrates the weekly RPE evolution, showing parallel trends between groups.

Pre- and post-intervention comparisons revealed significant improvements in the experimental group (EG) across most physical performance tests, whereas the control group (CG) showed no significative changes. Significant differences were observed in the 10-m sprint (p ˂ 0.001), 30-m sprint (p ˂ 0.001), squat jump (p ˂ 0.001), countermovement jump (p ˂ 0.001), standing long jump (p = 0.003), 5-jump test (p ˂ 0.001), and T-half agility test (p ˂ 0.001), indicating notable gains in speed, power, and agility in the experimental group.

In contrast, no significant changes were found for the VAMEVAL test (p > 0.05), suggesting similar aerobic endurance performance between groups. The control group did not show significant improvements for any variable (all p > 0.05). Mean values, percentage changes, and effect sizes are detailed in

Table 5.

The results presented in

Table 6 show that the two-way ANOVA (Group × Time) revealed significant main effects of time for most physical performance variables, except for the VAMEVAL test. These findings indicate an overall improvement in performance over time, particularly in sprint, jump, and agility tests. No significant main effect of group was observed, suggesting that participants from the different groups exhibited comparable performance levels.

Conversely, significant Group × Time interaction effects were found for several tests, indicating that performance improvements varied between groups. These interactions were mainly observed in speed, explosive power, and agility measures, while no differential changes were detected for aerobic endurance as assessed by the VAMEVAL test.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of integrating squat exercises into the final phase of warm-up on explosive strength, sprint performance, agility, and aerobic capacity in youth soccer players over a nine-week intervention. The main findings revealed that players in the EG demonstrated significant improvements in short sprint performance (10 and 30 m), vertical and horizontal jump tests, and agility performance, with effect sizes ranging from moderate to large. In contrast, no significant effect was observed on aerobic capacity, with only a small effect size noted.

Our results showed that the experimental group improved significantly in the 10 m and 30 m sprint tests. These findings suggest that the inclusion of squat exercises during warm-up enhances neuromuscular readiness, particularly the ability to generate explosive force over short distances [

27,

35,

36,

37,

38]

. Similar results were reported by [

39] and who found that lower-limb resistance training improved sprint performance in soccer players. The large effect observed in the 10 m sprint highlights the role of squats in improving acceleration capacity, which is critical for match-related actions such as pressing, defensive recovery, and attacking runs [

40]. These findings are also supported by [

41], who emphasized the post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) phenomenon, showing that high-intensity contractions can transiently improve subsequent explosive movements.

Significant gains were observed in jump performance, with the squat jump and countermovement jump showing the greatest improvements. These results are consistent with previous research demonstrating that squats effectively enhance lower-limb power output [

42]. Horizontal jump performance also improved, as reflected in the standing long jump and five-jump test. The transfer of squat training adaptations to both vertical and horizontal force production suggests improved neuromuscular coordination and intermuscular efficiency [

43]. Additionally, Díaz-Hidalgo et al. (2024) reported that explosive strength exercises can acutely enhance sprint and jump performance in soccer players, particularly when incorporated into warm-up routines, supporting the ecological validity of our intervention [

44].

The T-half agility test performance improved significantly in the experimental group. Agility is highly dependent on both acceleration and deceleration capacities, which are influenced by lower-limb strength. The present findings align with those of Aytac et al. (2024) and Darko et al. (2025), who emphasized the importance of strength training in enhancing change-of-direction performance. Furthermore, the inclusion of PAPE-oriented exercises like squats can improve reactive strength and rapid force production during multidirectional movements, which are essential for soccer-specific actions [

45,

46,

47].

No significant changes were found in VAMEVAL test performance, indicating that squat-based warm-up primarily targets neuromuscular and explosive capacities rather than aerobic fitness. This limited impact on aerobic performance can be explained by the nature, duration, and intensity of the squat intervention. This outcome is expected, as strength-oriented protocols do not significantly stimulate the cardiorespiratory system [

48]. Aerobic adaptations generally require continuous or interval training of longer duration and higher cardiovascular demand [

49]. These findings are consistent with previous evidence showing that strength or power-based warm-up activities mainly elicit acute potentiation effects, improving explosive actions without significantly influencing aerobic parameters [

48]. This finding is consistent with previous studies highlighting the specificity of training adaptations: resistance exercises improve power and sprint-related qualities but have limited effects on endurance performance [

50].

Practical Applications

From a practical perspective, the findings highlight the effectiveness of integrating squat exercises into the warm-up routine. The improvements observed in explosive strength, sprint speed, and agility indicate that a short, well-structured squat protocol can optimize players’ readiness before training and competition. Coaches working with youth soccer players may consider adopting squat-based activation, especially during the pre-competition warm-up, to maximize immediate performance outcomes and long-term neuromuscular adaptations. Importantly, the use of progressive load (50–85% 1-RM) with controlled tempo and adequate recovery appears to be crucial for eliciting these benefits. This supports recommendations regarding the optimal structure of warm-up interventions to exploit PAPE effects [

51,

52].

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its promising findings, the study presents some limitations. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 24) may restrict the generalizability of results. Second, the intervention period was limited to nine weeks; longer-term studies could provide further insights into the sustainability of performance gains. Third, while the study focused on physical performance measures, additional psychophysiological variables such as perceived exertion, physical enjoyment, and motivation could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of squat-based warm-up. Future research may also examine the combined effects of squat exercises with other neuromuscular activation strategies (e.g., plyometrics or resisted sprints) to determine the most effective warm-up modalities for soccer players. Integrating technical drills with strength exercises may further enhance transfer to game-specific scenarios [

53,

54].

5. Conclusions of the Discussion

In summary, the present study demonstrated that incorporating squat exercises into the final phase of warm-up produced moderate to large improvements in sprint performance, jump ability, and agility, while only a small effect was observed in aerobic capacity. These results confirm the value of squat-based activation as an effective, practical, and time-efficient strategy to enhance performance in youth soccer players. Moreover, the findings are supported by current literature on PAPE, neuromuscular conditioning, and sport-specific warm-up design, emphasizing the importance of evidence-based interventions for optimizing young athletes’ performance.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the institutional ethics committee of the High Institute of Sports and Physical Education in Kef (ISSEPK-0036/2024, 01 December 2024).

Consent for publication

All participants provided consent for anonymous data use for research purposes and publications. All authors approved of the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for any part of the work.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available upon request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S., A.B. and H.M.; methodology, O.S., C.I.A. and H.M.; software, E.A.P., M.A.R., B.A.A. and A.M.V.; validation, O.S., A.B., C.I.A. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, O.S., H.M., A.M.V. and M.A.R.; investigation, O.S. and H.M.; resources, O.S., E.A.P., B.A.A. and H.M.; data curation, O.S., H.M., E.A.P. and M.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S. and H.M.; writing—review and editing, O.S., H.M., C.I.A., M.A.R., A.M.V., E.A.P., B.A.A. and A.B.; visualization, H.M., A.B., A.M.V., E.A.P. and B.A.A.; supervision, A.B. and C.I.A.; project administration, O.S. and C.I.A.; funding acquisition, C.I.A., E.A.P., A.M.V. and B.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all youth soccer players who participated in this study. Crsitina Ioana Alexe, Ana Maria Vulpe, Elena Adelina Panaet and Bogdan Alexandru Antohe thank the ,,Vasile Alecsandri” University of Bacău, Romania for the support provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

References

- Zheng, T., Kong, R., Liang, X., Huang, Z., Luo, X., Zhang, X., & Xiao, Y. (2025). Effects of plyometric training on jump, sprint, and change of direction performance in adolescent soccer player: A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One, 20(4), e0319548. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Arrones, L., Gonzalo-Skok, O., Carrasquilla, I., Asián-Clemente, J., Santalla, A., Lara-Lopez, P., & Núñez, F. J. (2020). Relationships between change of direction, sprint, jump, and squat power performance. Sports, 8(3), 38. [CrossRef]

- Silva, H., Nakamura, F. Y., Bajanca, C., Pinho, G., Loturco, I., & Marcelino, R. (2024). The impact of different warm-up strategies on acceleration and deceleration demands in highly trained soccer players. European Journal of Sport Science, 24(1), 88-96. [CrossRef]

-

Ortega, F. B., Ruiz, J. R., Castillo, M. J., & Sjöström, M. (2005). Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: A powerful marker of health. International Journal of Obesity, *32*(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Tillin, N. A., & Bishop, D. (2009). Factors modulating post-activation potentiation and its effect on performance of subsequent explosive activities. Sports Medicine, 39(2), 147–166. [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L. B., & Haff, G. G. (2016). Factors modulating post-activation potentiation of jump, sprint, throw, and upper-body ballistic performances: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports medicine, 46(2), 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Bouzouraa, M. M., Dhahbi, W., Ghouili, H., Hamaidi, J., Aissa, M. B., Dergaa, I., ... & Knechtle, B. (2025). Enhancing problem-solving skills and creative thinking abilities in U-13 soccer players: the impact of rondo possession games’ training. Biology of Sport, 42(3), 227-238. [CrossRef]

- Thapa, R., Clemente, F., Moran, J., García-Pinillos, F., Scanlan, A., & Ramírez-Campillo, R. (2023). Warm-up optimization in amateur male soccer players: a comparison of small-sided games and traditional warm-up routines on physical fitness qualities. Biology of Sport, 40(1), 321-329. [CrossRef]

-

Rampinini, E., Coutts, A. J., Castagna, C., Sassi, R., & Impellizzeri, F. M. (2007). Variation in top level soccer match performance. International Journal of Sports Medicine, *28*(12), 1018–1024. [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, M., Jarosz, J., Urbański, R., Aschenbrenner, P., & Stastny, P. (2025). Effects of 6 weeks of complex training on athletic performance and post-activation performance enhancement effect magnitude in soccer players: a cross-sectional randomized study. Biology of Sport, 42(1), 211-221. [CrossRef]

- Titton, A., & Franchini, E. (2017). Postactivation potentiation in elite young soccer players. Journal of exercise rehabilitation, 13(2), 153. [CrossRef]

- Kurak, K., İlbak, İ., Stojanović, S., Bayer, R., Purenović-Ivanović, T., Pałka, T., ... & Rydzik, Ł. (2024). The ef fects of different stretching techniques used in warm-up on the triggering of post-activation performance enhancement in soccer players. Applied Sciences, 14(11), 4347. [CrossRef]

-

Martínez-Hernández, D., Quinn, M., & Jones, P. (2023). Linear advancing actions followed by deceleration and turn are the most common movements preceding goals in male professional soccer. Science and Medicine in Football, *7*(1), 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Chelly, M. S., Fathloun, M., Cherif, N., Amar, M. B., Tabka, Z., & Van Praagh, E. (2009). Effects of a back squat training program on leg power, jump, and sprint performances in junior soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(8), 2241-2249. [CrossRef]

- López-Segovia, M., Marques, M. C., Van den Tillaar, R., & González-Badillo, J. J. (2011). Relationships between vertical jump and full squat power outputs with sprint times in u21 soccer players. Journal of human kinetics, 30, 135. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J. L., Ramachandran, A. K., Singh, U., Ramirez-Campillo, R., & Lloyd, R. S. (2024). The effects of strength, plyometric and combined training on strength, power and speed characteristics in high-level, highly trained male youth soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 54(3), 623-643. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, J., Suarez-Arrones, L., de Hoyo, M., & Loturco, I. (2022). Strength training in professional soccer: effects on short-sprint and jump performance. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(06), 485-495. [CrossRef]

- McBride, J. M., Haines, T. L., & Kirby, T. J. (2011). Effect of loading on peak power of the bar, body, and system during power cleans, squats, and jump squats. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(11), 1215-1221. [CrossRef]

-

Blazevich, A. J., & Babault, N. (2019). Post-activation potentiation versus post-activation performance enhancement in humans: Historical perspective, underlying mechanisms, and current issues. Frontiers in Physiology, 10, 1359. [CrossRef]

-

Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., & Buchner, A. (1996). GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods, 39(2), 175-191. [CrossRef]

-

Boullosa, D. (2021). Post-activation performance enhancement strategies in sport: a brief review for practitioners. Human Movement, 22(3), 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Udin, M. C. A., Priadana, B. W., Aliriad, H., & Putri, W. S. K. (2025). Pengaruh El Rondo drill dan Triangle drill terhadap ketepatan short passing pemain sepakbola usia dini. Sepakbola, 5(1), 38-50. [CrossRef]

- Selmi, O., Rahmoune, M. A., Bouassida, A., Marsigliante, S., & Muscella, A. (2025). Comparative analysis of morning and evening training on performance and well-being in elite soccer players. Physiological Reports, 13(15), e70510. [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Florhaug, J.A.; Franklin, J.; Gottschall, L.; Hrovatin, L.A.; Parker, S.; Dodge, C. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2001, 15, 109–115.

- Kojic, F., Mandic, D., & Duric, S. (2025). The effects of eccentric phase tempo in squats on hypertrophy, strength, and contractile properties of the quadriceps femoris muscle. Frontiers in Physiology, 15, 1531926. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B., Pereira, A., Alves, A. R., Neves, P. P., Marques, M. C., Marinho, D. A., & Neiva, H. P. (2021). Specific warm-up enhances movement velocity during bench press and squat resistance training. Journal of Men’s Health, 18, 1-8.

- Coyne, J.O.; Gregory Haff, G.; Coutts, A.J.; Newton, R.U.; Nimphius, S. The current state of subjective training load monitoring—A practical perspective and call to action. Sports Med. Open 2018, 4, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Köklü, Y., Alemdaroğlu, U., Özkan, A., Koz, M., & Ersöz, G. The relationship between sprint ability, agility and vertical jump performance in young soccer players. Science & Sports, 2015, 30(1), e1-e5. [CrossRef]

- Rites, A. A., Merino-Muñoz, P., Ribeiro, F., Miarka, B., Salermo, V., Gomes, D. V., & Aedo-Muñoz, E. Effects of peppermint oil inhalation on vertical jump performance in elite young professional soccer players: A double-blinded randomized crossover study. Heliyon, 2024, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Sassi, R. H., Dardouri, W., Yahmed, M. H., Gmada, N., Mahfoudhi, M. E., & Gharbi, Z. Relative and absolute reliability of a modified agility T-test and its relationship with vertical jump and straight sprint. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 2009, 23(6), 1644-1651. [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, G., & Léger, L. (1993). Comment évaluer et développer vos capacités aérobies: épreuve de course navette et épreuve VAMEVAL. AREAPS (Association Recherche et Evaluation en Activité Physique et en Sport).

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101.

- Hopkins, W.; Marshall, S.; Batterham, A.; Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3. [CrossRef]

-

Neves, P. P., Marques, D. L., Neiva, H. P., Marinho, D. A., Ferraz, R., Marques, M. C., & Alves, A.R. Impact of Re-Warm-Up During Resistance Training: Analysis of Mechanical and Physiological Variables. Sports, 2025, 13(5), 142. [CrossRef]

- Hammami, M., Negra, Y., Billaut, F., Hermassi, S., Shephard, R. J., & Chelly, M. S. (2018). Effects of lower-limb strength training on agility, repeated sprinting with changes of direction, leg peak power, and neuromuscular adaptations of soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(1), 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Alexe, D.I., Čaušević, D., Čović, N., Rani, .B, Tohănean, D.I., Abazović, E., Setiawan, E., Alexe, C.I. The Relationship between Functional Movement Quality and Speed, Agility, and Jump Performance in Elite Female Youth Football Players. Sports. 2024; 12(8):214. [CrossRef]

- Jouira, G., Alexe, D.I., Tohănean, D.I., Alexe, C.I., Tomozei, R.A., Sahli, S. The Relationship between Dynamic Balance, Jumping Ability, and Agility with 100 m Sprinting Performance in Athletes with Intellectual Disabilities. Sports 2024, 12, 2, 58. [CrossRef]

- Čaušević, D., Rani, B., Gasibat, Q., Čović, N., Alexe, C.I., Pavel, S.I., Burchel, L.O., Alexe, D.I. Maturity-Related Variations in Morphology, Body Composition, and Somatotype Features among Young Male Football Players. Children. 2023; 10(4):721. [CrossRef]

- Styles, W. J., Matthews, M. J., & Comfort, P. (2016). Effects of strength training on squat and sprint performance in soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(6), 1534-1539. [CrossRef]

- Aytaç, T., & İşler, A. K. (2025). Beyond the warm-up: Understanding the post-activation performance enhancement. Spor Hekimliği Dergisi, 60(3), 114-121. [CrossRef]

- Asghari, S. H., Wong, A., Comfort, P., Mirghani, S. J., Sharifian, S., & Ghaderi, M. (2025). Comparing the impact of hip thrust versus squat training on lower limb performance in sub-elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Biomechanics, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Bichowska-Paweska, M., Fostiak, K., Gawel, D., Trybulski, T., Alexe, D.I., Wilk, W. The Acute Effect of Blood Flow Restriction or Ischemia on Countermovement Jump Performance. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 2025, 20(2), p.658-670,. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Hidalgo, S., Ranchal-Sanchez, A., & Jurado-Castro, J. M. (2024). Improvements in jump height, speed, and quality of life through an 8-week strength program in male adolescents soccer players. Sports, 12(3), 67. [CrossRef]

- Aytac, T., Esatbeyoglu, F., & Kin-Isler, A. (2024). Post-activation performance enhancement on change of direction speed: Effects of heavy back-squat exercise. Science & Sports, 39(2), 196-205. [CrossRef]

- Darko, R. O., Odoi-Yorke, F., Abbey, A. A., Afutu, E., Owusu-Sekyere, J. D., Sam-Amoah, L. K., & Acheampong, L. (2025). A review of climate change impacts on irrigation water demand and supply-a detailed analysis of trends, evolution, and future research directions. Water Resources Management, 39(1), 17-45. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H., Wirth, K., Klusemann, M., Dalic, J., Matuschek, C., & Schmidtbleicher, D. (2012). Influence of squatting depth on jumping performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(12), 3243-3261. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Torres, J.M.; García-Roca, J.A.; Abellan-Aynes, O.; Diaz-Aroca, A. Effects of Supervised Strength Training on Physical Fitness in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 2025, 10(2), 162. [CrossRef]

- Sautov, R.; Tyshchenko, V.; Tovstopyatko, F.; Dyadechko, I.; Utegenov, Y.; Shankulov, Y.; & Yeskaliyev, M. Hemodynamic modeling of aerobic adaptation in football players through interval-functional training. Journal of Physical Education & Sport, 2025, 25(7).

- Ramos-Campo, D.J;, Andreu-Caravaca, L.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á. The Effect of Strength Training on Endurance Performance Determinants in Middle-and Long-Distance Endurance Athletes: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 2025, 39(4), 492-506. [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L. B., & Haff, G. G. (2016). Factors modulating post-activation potentiation of jump, sprint, throw, and upper-body ballistic performances: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports medicine, 46(2), 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Loturco, I., Pereira, L. A., Kobal, R., Zanetti, V., Kitamura, K., Abad, C. C. C., & Nakamura, F. Y. (2015). Transference effect of vertical and horizontal plyometrics on sprint performance of high-level U-20 soccer players. Journal of sports sciences, 33(20), 2182-2191. [CrossRef]

-

Silva, L.M.; Neiva, HP.; Marques, MC.; Izquierdo, M.; Marinho D.A. Effects of Warm-Up, Post-Warm-Up, and Re-Warm-Up Strategies on Explosive Efforts in Team Sports: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2018, 48(10):2285-2299. [CrossRef]

- Jumareng, H.; Setiawan, E.; Tannoubi, A.; Lardika, R.A.; Adil, A.; Gazali, N.; Gani, R.G.; Ahmedov, F.; Kurtoğlu, A.; Alexe, D.I. Small Sided Games 3vs3 Goalkeeper-Encouragement: Improve the Physical and Technical Performance of Youth Soccer Players, European Journal of Human Movement, 2024, vol. 52, p.129-140. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).