Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Origin and Distribution of the HMs in Agroecosystems

2.1. Geogenic Sources and Natural Input of HMs

2.2. Anthropogenic Sources of HMs

2.3. Agricultural Sources

2.3.1. Fertilizers as Heavy Metal Inputs

2.3.2. Pesticides as a Source of Soil Contamination

2.3.3. Compost and Livestock Manure as Contaminant Carrier

2.3.4. Irrigation with Contaminated Water

3. Impact of Heavy Metal Accumulation on Soil Health

4. Heavy Metal Dynamics in Cereals

4.1. Cadmium Uptake and Transport Pathways in Wheat

4.1.1. Root Absorption of Cadmium

4.1.2. Translocation of Cadmium to the Xylem

4.1.3. Systemic Movement of Cadmium to Shoots and Grains

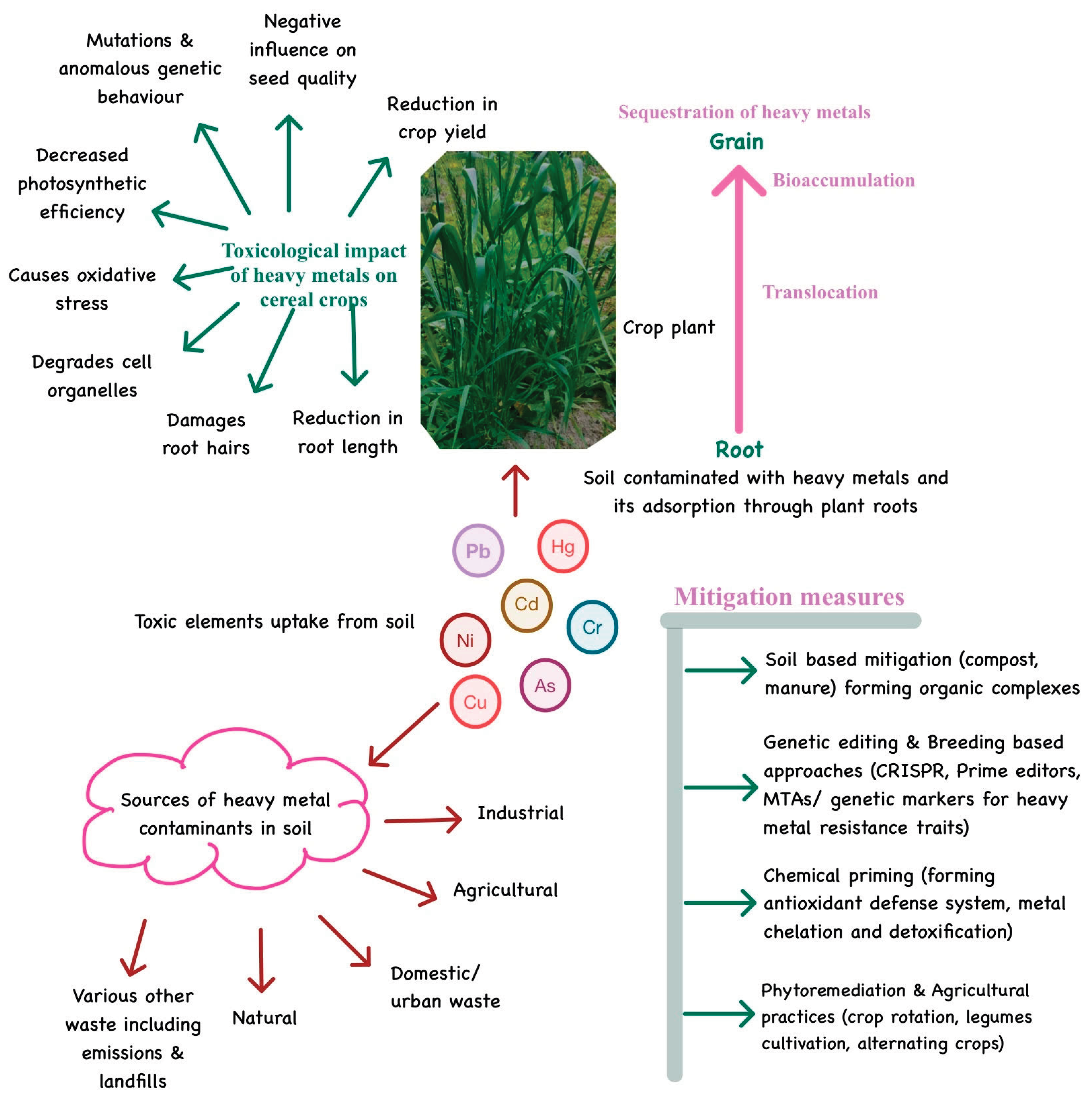

4.2. Toxicological Effects of HMs on Cereals

4.2.1. Cadmium Toxicity

4.2.2. Chromium Toxicity

4.2.3. Lead Toxicity

4.2.4. Mercury Toxicity

5. Mechanistic Insights into HM-Induced Growth Constraints in Plants

6. Bioavailability and Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals

7. Approaches to Control HM Bioaccumulation in Agroecosystems

7.1. Soil-based Mitigation Approaches

7.2. Genetic and Breeding-Based Strategies

7.3. Chemical Priming for Enhanced Metal Tolerance

7.4. Monitoring and Regulatory Framework

7.5. Agronomic and Phytoremediation Practices

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HM | Heavy Metal. |

| NRAMP | Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein. |

| YSL | Yellow Stripe Like. |

| IRT | Iron regulated transporter. |

| DACC | Depolarization-activated Ca2+ channels. |

| WHO | World Health Organization. |

| IAA | Indole acetic acid. |

| JA | Jasmonic Acid. |

| ALA | δ-aminolaevulinic acid. |

| ABA | Abscisic acid. |

| HACC | Hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ channels. |

| VICC | Voltage-independent Ca2+ channels. |

| ZNT | Zinc Transporter. |

| ZIP | Zn-Iron regulated protein. |

| LCT | Low affinity Cation Transporter. |

References

- Neilson, S.; Rajakaruna, N. Phytoremediation of agricultural soils: Using plants to clean Metal-Contaminated arable land. In Phytoremediation; 2014; pp 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals—Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.S.; Rajakaruna, N. Heavy metal tolerance. Oxford Bibliographies Online Datasets 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, Z.; Van Der Kuijp, T.J.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, L. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from mines in China: Pollution and health risk assessment. The Science of the Total Environment 2013, 468–469, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelar, M.; Gawade, V.; Bhujbal, S. A Review on Heavy Metal Contamination in Herbals. JPRI 2021, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho-Ruk, K.; Kurukote, J.; Supprung, P.; Vetayasupo, S. Perennial plants in the phytoremediation of lead-contaminated soils. Biotechnology(Faisalabad) 2005, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangahu, B.V.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Basri, H.; Idris, M.; Anuar, N.; Mukhlisin, M. A Review on Heavy Metals (As, Pb, and Hg) Uptake by Plants through Phytoremediation. International Journal of Chemical Engineering 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Shaogang, L.; Xiaoyang, C. Assessment of heavy metal pollution and human health risk in urban soils of a coal mining city in East China. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment an International Journal 2016, 22, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Khalique, G.; Irfan, M.; Wani, A.S.; Tripathi, B.N.; Ahmad, A. Physiological changes induced by chromium stress in plants: an overview. PROTOPLASMA 2011, 249, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achterbosch, T.J.; Berkum, S.; Meijerink, G.W. Cash crops and food security: Contributions to Income, Livelihood Risk and Agricultural Innovation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Mir, R.A.; Tyagi, A.; Manzar, N.; Kashyap, A.S.; Mushtaq, M.; Raina, A.; Park, S.; Sharma, S.; Mir, Z.A.; Lone, S.A.; Bhat, A.A.; Baba, U.; Mahmoudi, H.; Bae, H. Chromium toxicity in plants: Signaling, mitigation, and future perspectives. Plants 2023, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Abdelkhalek, S.T.; Qureshi, S.R.; Wang, M.-Q. Heavy Metals and pesticides Toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil: Environmental pollutants affecting crop health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyazuddin, R.; Nisha, N.; Ejaz, B.; Khan, M.I.R.; Kumar, M.; Ramteke, P.W.; Gupta, R. A comprehensive review on the heavy metal toxicity and sequestration in plants. Biomolecules 2021, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangahu, B.V.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Basri, H.; Idris, M.; Anuar, N.; Mukhlisin, M. A Review on Heavy Metals (As, Pb, and Hg) Uptake by Plants through Phytoremediation. International Journal of Chemical Engineering 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanston, J.S. Cereal Grains: Properties, Processing and Nutritional Attributes. By S. O. Serna-Salvidar. Boca Raton, Fl, USA: CRC Press (2010), pp. 747, US$99.00. ISBN 978-1-4398-1560-1. Experimental Agriculture 2011, 47, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S.; Feng, J., MA. Toxic heavy metal and metalloid accumulation in crop plants and foods. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2016, 67, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, A.; Rasheed, R.; Ashraf, M.A.; Qureshi, F.F.; Hussain, I.; Iqbal, M. Effect of heavy metals on growth, physiological and biochemical responses of plants. In Elsevier eBooks; 2023; pp 139–159. [CrossRef]

- IARC monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risk of chemicals to humans. Food and Chemical Toxicology 1987, 25, 717. [CrossRef]

- Nagajyoti, P.C.; Lee, K.D.; Sreekanth, T.V.M. Heavy metals, occurrence and toxicity for plants: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2010, 8, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnine, M.T.; Huda, M.E.; Khatun, R.; Saadat, A.H.M.; Ahasan, M.; Akter, S.; Uddin, M.F.; Monika, A.N.; Rahman, M.A.; Ohiduzzaman, M. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil at DEPZA, Bangladesh. Environment and Ecology Research 2017, 5, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obinna, I.B.; Ebere, E.C. A review: Water pollution by heavy metal and organic pollutants: Brief review of sources, effects and progress on remediation with aquatic plants. Analytical Methods in Environmental Chemistry Journal 2019, 2, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, J.; Kumar, P. Heavy metals accumulation in crop plants: Sources, response mechanisms, stress tolerance and their effects. In Agro Environ Media—Agriculture and Ennvironmental Science Academy, Haridwar, India eBooks; 2019; pp 38–57. [CrossRef]

- Khatun, R.; Rana, M.; Ahasan, M.; Akter, S.; Uddin, F.; Monika, A.N.; Ohiduzzaman, M. Site planning of a newly installed LINAC at BAEC, Bangladesh. Universal Journal of Medical Science 2017, 5, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biological effects of heavy metals: an overview. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16334259/.

- Filby, R.; Shah, K.; Hunt, M.; Khalil, S.; Sautter, C. Solvent Refined Coal (SRC) Process: Trace Elements. Research and Development Report No. 53; Interim Report No. 26. Volume III. Pilot Plant Development Work. Part 6. The Fate of Trace Elements in the SRC Process for the Period August 1, 1974--July 31, 1976. 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masindi, V.; Muedi, K.L. Environmental contamination by heavy metals. In InTech eBooks; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Raiesi, F.; Sadeghi, E. Interactive effect of salinity and cadmium toxicity on soil microbial properties and enzyme activities. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 168, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.-J. Soil ecotoxicity assessment using cadmium sensitive plants. Environmental Pollution 2003, 127, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, M.; Li, C. Soil heavy metal contamination assessment in the Hun-Taizi River watershed, China. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mar, S.S.; Okazaki, M.; Motobayashi, T. The influence of phosphate fertilizer application levels and cultivars on cadmium uptake by Komatsuna (Brassica rapaL. var.perviridis). Soil Science & Plant Nutrition 2012, 58, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Yu, J.; Cao, Z.; Meng, M.; Yang, L.; Chen, Q. The Availability and Accumulation of Heavy Metals in Greenhouse Soils Associated with Intensive Fertilizer Application. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A review of sources, chemistry, risks and Best available Strategies for remediation. ISRN Ecology 2011, 2011, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-X.; Liu, Y.-M.; Zhao, Q.-Y.; Cao, W.-Q.; Chen, X.-P.; Zou, C.-Q. Health risk assessment associated with heavy metal accumulation in wheat after long-term phosphorus fertilizer application. Environmental Pollution 2020, 262, 114348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.S.; Adriano, D.C.; Naidu, R. Role of Phosphorus in (Im)mobilization and Bioavailability of Heavy Metals in the Soil-Plant System. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2003, 177, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, P.; Jin, K.; Alengebawy, A.; Elsayed, M.; Meng, L.; Chen, M.; Ran, Y. Effect of application of different biogas fertilizer on eggplant production: Analysis of fertilizer value and risk assessment. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2020, 19, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Teng, Y.; Christie, P.; Luo, Y. Effects of long-term fertilizer applications on peanut yield and quality and plant and soil heavy metal accumulation. Pedosphere 2017, 30, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D. Pesticides and Pest Control. In Integrated Pest Management: Innovation-Development Process; Peshin, R., Dhawan, A.K., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2009; pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Handa, N.; Kohli, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Bali, A.S.; Parihar, R.D.; Dar, O.I.; Singh, K.; Jasrotia, S.; Bakshi, P.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Kumar, S.; Bhardwaj, R.; Thukral, A.K. Worldwide pesticide usage and its impacts on ecosystem. SN Applied Sciences 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A.; Bose, R.; Kumar, A.; Mozumdar, S. Targeted delivery of pesticides using biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.A.; Tzilivakis, J.; Warner, D.J.; Green, A. An international database for pesticide risk assessments and management. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment an International Journal 2016, 22, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, P.; Kumar, D.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, K. Nanobiotechnology and its Application in Agriculture and Food Production. In Nanotechnology in the life sciences; 2020; pp. 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuwaiser, M.A. An analytical survey of trace heavy elements in insecticides. International Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Mu, H.-Y.; Fu, P.-N.; Wan, Y.-N.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.-F. Accumulation of potentially toxic elements in agricultural soil and scenario analysis of cadmium inputs by fertilization: A case study in Quzhou county. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 269, 110797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-R.; Zeng, D.; She, L.; Su, W.-X.; He, D.-C.; Wu, G.-Y.; Ma, X.-R.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, C.-H.; Ying, G.-G. Comparisons of pollution characteristics, emission situations, and mass loads for heavy metals in the manures of different livestock and poultry in China. The Science of the Total Environment 2020, 734, 139023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, J.; Kumar, P. Heavy metals accumulation in crop plants: Sources, response mechanisms, stress tolerance and their effects. In Agro Environ Media—Agriculture and Ennvironmental Science Academy, Haridwar, India eBooks; 2019; pp. 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.; Larsen, M.M.; Bak, J. National monitoring study in Denmark finds increased and critical levels of copper and zinc in arable soils fertilized with pig slurry. Environmental Pollution 2016, 214, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yan, Z.; Qin, J.; Xiao, Z. Effects of long-term cattle manure application on soil properties and soil heavy metals in corn seed production in Northwest China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2014, 21, 7586–7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yu, G.; Shen, Q.; Zhao, F.-J. Heavy metal concentrations and arsenic speciation in animal manure composts in China. Waste Management 2017, 64, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.-H. Heavy metals in food crops: Health risks, fate, mechanisms, and management. Environment International 2019, 125, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment of Heavy Metal Contamination of Agricultural Soil around Dhaka Export Processing Zone (DEPZ), Bangladesh: Implication of Seasonal Variation and Indices. In Apple Academic Press eBooks; 2014; pp. 253–278. [CrossRef]

- Berihun, B.T.; Amare, D.E.; Raju, R.; Ayele, D.T.; Dagne, H. Determination of the level of metallic contamination in irrigation vegetables, the soil, and the water in Gondar City, Ethiopia. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements 2021, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Ozaki, A.; Thinh, N.; Kurosawa, K. Heavy Metal Contamination of Irrigation Water, Soil, and Vegetables and the Difference between Dry and Wet Seasons Near a Multi-Industry Zone in Bangladesh. Water 2019, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohankumar, K.; Hariharan, V.; Rao, N.P. Heavy Metal Contamination in Groundwater around Industrial Estate vs. Residential Areas in Coimbatore, India. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH 2016, 10, BC05-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, Md. E.; Su, C.; Li, J.; Sarven, M.S. Arsenic enrichment and mobilization in the Holocene alluvial aquifers of Prayagpur of Southwestern Bangladesh. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2018, 128, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaque, F.; Inam, A.; Sahay, S.; Iqbal, S. Influence of heavy metal toxicity on plant growth, metabolism and its alleviation by phytoremediation - a promising technology. Journal of Agriculture and Ecology Research International 2016, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Zaidi, A.; Goel, R.; Musarrat, J. Biomanagement of Metal-Contaminated soils; 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Xu, X.; Zhong, C.; Jiang, T.; Wei, W.; Song, X. Removal of Cadmium and Lead from Contaminated Soils Using Sophorolipids from Fermentation Culture of Starmerella bombicola CGMCC 1576 Fermentation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotaniya, M.L.; Dotaniya, C.K.; Solanki, P.; Meena, V.D.; Doutaniya, R.K. Lead contamination and its dynamics in Soil–Plant system. In Radionuclides and heavy metals in environment; 2019; pp 83–98. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; MMS, C.-P.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Shabnam, A.A.; Subrahmanyam, G.; Mondal, R.; Gupta, D.K.; Malyan, S.K.; Kumar, S.S.; Khan, S.A.; Yadav, K.K. Lead toxicity: health hazards, influence on food chain, and sustainable remediation approaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placek, A.; Grobelak, A.; Kacprzak, M. Improving the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soil by use of sewage sludge. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2015, 18, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Hesham, A.E.-L.; Qiao, M.; Rehman, S.; He, J.-Z. Effects of Cd and Pb on soil microbial community structure and activities. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2009, 17, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlček, V.; Pohanka, M. Adsorption of Copper in Soil and its Dependence on Physical and Chemical Properties. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 2018, 66, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xia, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z.; Ahmad, Z. Separate and joint eco-toxicological effects of sulfadimidine and copper on soil microbial biomasses and ammoxidation microorganisms abundances. Chemosphere 2019, 228, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njinga, R.L.; Moyo, M.N.; Abdulmaliq, S.Y. Analysis of essential elements for plants growth using instrumental neutron activation analysis. International Journal of Agronomy 2013, 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, J.; Degryse, F.; Springael, D.; Smolders, E. Zinc Toxicity to Nitrification in Soil and Soilless Culture Can Be Predicted with the Same Biotic Ligand Model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 2992–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukowski, A.; Dec, D. Influence of Zn, Cd, and Cu fractions on enzymatic activity of arable soils. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2018, 190, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awino, F.B.; Maher, W.; Lynch, A.J.J.; Fai, P.B.A.; Otim, O. Comparison of metal bioaccumulation in crop types and consumable parts between two growth periods. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 2021, 18, 1056–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Khalid, S.; Schreck, E.; Xiong, T.; Niazi, N.K. Foliar heavy metal uptake, toxicity and detoxification in plants: A comparison of foliar and root metal uptake. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2016, 325, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, D.A.; Wildung, R.E. Soil and plant factors influencing the accumulation of heavy metals by plants. Environmental Health Perspectives 1978, 27, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, T.; Gavanji, S.; Mojiri, A. Lead and zinc uptake and toxicity in maize and their management. Plants 2022, 11, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Qi, S.-S.; Gul, F.; Manan, S.; Rono, J.K.; Naz, M.; Shi, X.-N.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.-C.; Du, D.-L. A green approach used for heavy metals ‘Phytoremediation’ via invasive plant species to mitigate environmental pollution: a review. Plants 2023, 12, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. A comparative study of the factors affecting uptake and distribution of Cd with Ni in barley. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 162, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.-J.; Wang, P. Arsenic and cadmium accumulation in rice and mitigation strategies. Plant and Soil 2019, 446, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrijo, D.R.; LaHue, G.T.; Parikh, S.J.; Chaney, R.L.; Linquist, B.A. Mitigating the accumulation of arsenic and cadmium in rice grain: A quantitative review of the role of water management. The Science of the Total Environment 2022, 839, 156245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zheng, S. Multi-Omics Uncover the Mechanism of Wheat under Heavy Metal Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, A.; Zaidi, A.; Ameen, F.; Ahmed, B.; AlKahtani, M.D.F.; Khan, M.S. Heavy metal induced stress on wheat: phytotoxicity and microbiological management. RSC Advances 2020, 10, 38379–38403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antisari, L.V.; Orsini, F.; Marchetti, L.; Vianello, G.; Gianquinto, G. Heavy metal accumulation in vegetables grown in urban gardens. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2015, 35, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, W.-T.; Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Gu, J.-F.; Wang, W.-L.; Zou, J.-L.; Tian, T.; Peng, P.-Q.; Liao, B.-H. Accumulation of heavy metals in vegetable species planted in contaminated soils and the health risk assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilachi, I.C.; Stoleru, V.; Gavrilescu, M. Analysis of heavy metal impacts on cereal crop growth and development in contaminated soils. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Ali, S.; Zhang, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Qiu, B.; Wu, F.; Zhang, G. The influence of pH and organic matter content in paddy soil on heavy metal availability and their uptake by rice plants. Environmental Pollution 2010, 159, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Qin, X.; Xu, C.; Yan, X. Effects of Soil pH on the Growth and Cadmium Accumulation in Polygonum hydropiper (L.) in Low and Moderately Cadmium-Contaminated Paddy Soil. Land 2023, 12, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neenan, M. The effects of soil acidity on the growth of cereals with particular reference to the differential reaction of varieties thereto. Plant and Soil 1960, 12, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Kamran, M.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cao, H.; Yang, G.; Deng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Anastopoulos, I.; Wang, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-induced mitigation of heavy metal phytotoxicity in metal contaminated soils: A critical review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 402, 123919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Zia-Ur-Rehman, M.; Rizwan, M.; Abbas, T.; Ayub, M.A.; Naeem, A.; Alharby, H.F.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Alharbi, B.M.; Qamar, M.J.; Ali, S. Effect of soil texture and zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth and accumulation of cadmium by wheat: a life cycle study. Environmental Research 2022, 216 Pt 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroli, G.B.M.; Maasdam, W.A.C.; Verstraten, J.M. Zinc in poor sandy soils and associated groundwater. A case study. The Science of the Total Environment 1990, 91, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.; Wang, W.; Yamaji, N.; Fukuoka, S.; Che, J.; Ueno, D.; Ando, T.; Deng, F.; Hori, K.; Yano, M.; Shen, R.F.; Feng, J., MA. Duplication of a manganese/cadmium transporter gene reduces cadmium accumulation in rice grain. Nature Food 2022, 3, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yu, H.; Li, T.; Chen, G.; Huang, F. Cadmium accumulation characteristics of low-cadmium rice (Oryza sativa L.) line and F1 hybrids grown in cadmium-contaminated soils. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 17566–17576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, G.; Javed, W.; Hussain, A.; Qadir, M.; Aslam, M. Soil-applied zinc and copper suppress cadmium uptake and improve the performance of cereals and legumes. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2016, 19, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, A.; Wang, P.; Ali, A.; Awasthi, M.K.; Lahori, A.H.; Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z. Challenges and opportunities in the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2015, 126, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, A.; Ahmed, B.; Zaidi, A.; Khan, M.S. Heavy metal mediated phytotoxic impact on winter wheat: oxidative stress and microbial management of toxicity byBacillus subtilisBM2. RSC Advances 2019, 9, 6125–6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.S.; Rizwan, M.; Hafeez, M.; Ali, S.; Adrees, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Khalid, S.; Rehman, M.Z.U.; Sarwar, M.A. Effects of silicon nanoparticles on growth and physiology of wheat in cadmium contaminated soil under different soil moisture levels. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 27, 4958–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormoker, T.; Proshad, R.; Islam, Md. S.; Shamsuzzoha, Md.; Akter, A.; Tusher, T.R. Concentrations, source apportionment and potential health risk of toxic metals in foodstuffs of Bangladesh. Toxin Reviews 2020, 40, 1447–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, P.S.; Saha, J.K.; Dotaniya, M.L.; Sarkar, A.; Saha, M. Wastewater irrigation in India: Current status, impacts and response options. The Science of the Total Environment 2021, 808, 152001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Wang, F.; Liang, S.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Chai, T. Improved Cd, Zn and Mn tolerance and reduced Cd accumulation in grains with wheat-based cell number regulator TaCNR2. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, A.; Martinka, M.; Vaculik, M.; White, P.J. Root responses to cadmium in the rhizosphere: a review. Journal of Experimental Botany 2010, 62, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, X. Cadmium absorption and transportation pathways in plants. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2016, 19, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, T.; Mojiri, A. Cadmium Uptake by Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): An Overview. Plants 2020, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Duan, S.; Wu, Q.; Yu, M.; Shabala, S. Reducing cadmium accumulation in plants: Structure–Function Relations and Tissue-Specific Operation of transporters in the spotlight. Plants 2020, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uraguchi, S.; Fujiwara, T. Cadmium transport and tolerance in rice: perspectives for reducing grain cadmium accumulation. Rice 2012, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jammes, F.; Hu, H.; Villiers, F.; Bouten, R.; Kwak, J.M. Calcium-permeable channels in plant cells. FEBS Journal 2011, 278, 4262–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, R.; Murata, J.; Murata, Y. A novel Barley Yellow Stripe 1-Like transporter (HVYSL2) localized to the root endodermis transports Metal–Phytosiderophore complexes. Plant and Cell Physiology 2011, 52, 1931–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.F.; Omelon, C.R.; Gordon, R.A.; Moser, D.; Macfie, S.M. Localization and chemical speciation of cadmium in the roots of barley and lettuce. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2013, 100, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, J. Cadmium phytoextraction from loam soil in tropical southern China by Sorghum bicolor. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2016, 19, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocito, F.F.; Lancilli, C.; Dendena, B.; Lucchini, G.; Sacchi, G.A. Cadmium retention in rice roots is influenced by cadmium availability, chelation and translocation. Plant Cell & Environment 2011, 34, 994–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.-J.; Qiu, R.-L.; Senthilkumar, P.; Jiang, D.; Chen, Z.-W.; Tang, Y.-T.; Liu, F.-J. Tolerance, accumulation and distribution of zinc and cadmium in hyperaccumulator Potentilla griffithii. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2009, 66, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodda, M.S.; Li, G.; Reid, R.J. The timing of grain Cd accumulation in rice plants: the relative importance of remobilisation within the plant and root Cd uptake post-flowering. Plant and Soil 2011, 347, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.E.; Cobbett, C.S. HMA P-type ATPases are the major mechanism for root-to-shoot Cd translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist 2008, 181, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Benavides, T.; McCann, C.J.; Argüello, J.M. The mechanism of CU+ transport ATPAses. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 288, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, S. Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie 2006, 88, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandwani, S.; Kayasth, R.; Naik, H.; Amaresan, N. Current status and future prospect of managing lead (Pb) stress through microbes for sustainable agriculture. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.M.; Okal, E.J.; Waseem, M. Cadmium Toxicity Impacts Plant Growth and Plant Remediation Strategies. Plant Growth Regul 2023, 99, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.A.; Kanwar, M.K.; Rodrigues Dos Reis, A.; Ali, B. Editorial: Heavy Metal Toxicity in Plants: Recent Insights on Physiological and Molecular Aspects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 830682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Khalid, S.; Schreck, E.; Xiong, T.; Niazi, N.K. Foliar Heavy Metal Uptake, Toxicity and Detoxification in Plants: A Comparison of Foliar and Root Metal Uptake. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2017, 325, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Long, H.; Yang, L.; Li, G.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Shi, W.; Shao, R. Water Deficit Aggravated the Inhibition of Photosynthetic Performance of Maize under Mercury Stress but Is Alleviated by Brassinosteroids. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 443, 130365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinandan, K.; Skori, L.; Stanic, M.; Hickerson, N.M.N.; Jamshed, M.; Samuel, M.A. Abiotic stress signaling in wheat – An inclusive overview of hormonal interactions during abiotic stress responses in wheat. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. Toxicity, Mechanism and Health Effects of Some Heavy Metals. Interdisciplinary Toxicology 2014, 7, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Sandhi, A. Heavy Metal and Drought Stress in Plants: The Role of Microbes—A Review. Gesunde Pflanzen 2023, 75, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, S.M.; Pena, L.B.; Barcia, R.A.; Azpilicueta, C.E.; Iannone, M.F.; Rosales, E.P.; Zawoznik, M.S.; Groppa, M.D.; Benavides, M.P. Unravelling Cadmium Toxicity and Tolerance in Plants: Insight into Regulatory Mechanisms. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2012, 83, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Kalaji, H.M.; Jajoo, A. Investigation of Deleterious Effects of Chromium Phytotoxicity and Photosynthesis in Wheat Plant. Photosynt. 2016, 54, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotaniya, M.L.; Thakur, J.K.; Meena, V.D.; Jajoria, D.K.; Rathor, G. Chromium Pollution: A Threat to Environment-A Review. Agri. Rev. 2014, 35, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotaniya, M.L.; Meena, M.D.; Meena, M.K.; Choudhary, R.L.; Doutaniya, R.K.; Kumar, K.; Dotaniya, C.K.; Meena, H.M.; Yadav, D.K.; Meena, A.; Jat, R.S.; Rai, P.K. Chromium: Path from Economic Development to Environmental Toxicity. In Research Advances in Environment, Geography and Earth Science Vol. 1; Yousef, Prof. A. F., Ed.; B P International, 2024; pp 110–123. [CrossRef]

- Wakeel, A.; Ali, I.; Wu, M.; Raza Kkan, A.; Jan, M.; Ali, A.; Liu, Y.; Ge, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, B.; Gan, Y. Ethylene Mediates Dichromate-Induced Oxidative Stress and Regulation of the Enzymatic Antioxidant System-Related Transcriptome in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019, 161, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, M.; Sharma, A. Mercury Toxicity in Plants. Bot. Rev 2000, 66, 379–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.X.; Su, Y.; Monts, D.L.; Waggoner, C.A.; Plodinec, M.J. Binding, Distribution, and Plant Uptake of Mercury in a Soil from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA. Science of The Total Environment 2006, 368, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israr, M.; Sahi, S.; Datta, R.; Sarkar, D. Bioaccumulation and Physiological Effects of Mercury in Sesbania Drummondii. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R.; Kohli, R.K. Lead (Pb)-Induced Biochemical and Ultrastructural Changes in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum) Roots. Protoplasma 2013, 250, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Ma, J.; Jiang, P.; Li, J.; Gao, J.; Qiao, S.; Zhao, Z. The Mechanism of Plant Resistance to Heavy Metal. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 310, 052004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, K.; Rasheed, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Seki, M.; Nishizawa, N.K. Regulating Subcellular Metal Homeostasis: The Key to Crop Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Caroli, M.; Furini, A.; DalCorso, G.; Rojas, M.; Di Sansebastiano, G.-P. Endomembrane Reorganization Induced by Heavy Metals. Plants 2020, 9, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Martinoia, E.; Szabo, I. Organellar Channels and Transporters. Cell Calcium 2015, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichhode, M.; Asati, A.; Katare, J.; Gaherwal, S. Assessment of Heavy Metal, Arsenic in Chhilpura Pond Water and Its Effect on Haematological and Biochemical Parameters of Catfish, Clarias Batrachus. NEPT 2020, 19, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, U.; Farid, M.; Rizwan, M.; Ishaq, H.K.; Farid, S.; Ali, S.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wijaya, L. Physiological and Biochemical Response of Alternanthera Bettzickiana (Regel) G. Nicholson under Acetic Acid Assisted Phytoextraction of Lead. Plants 2020, 9, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malar, S.; Shivendra Vikram, S.; Jc Favas, P.; Perumal, V. Lead Heavy Metal Toxicity Induced Changes on Growth and Antioxidative Enzymes Level in Water Hyacinths [Eichhornia Crassipes (Mart.)]. Bot Stud 2016, 55, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafpour, M.M.; Shen, J.-R.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Natural and Artificial Photosynthesis: Fundamentals, Progress, and Challenges. Photosynth Res 2022, 154, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, A.; El-Shazly, H.H.; Mohamed, H.I. Plant Responses to Induced Genotoxicity and Oxidative Stress by Chemicals. In Induced Genotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in Plants; Khan, Z., Ansari, M.Y.K., Shahwar, D., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.E.; Derbes, R.S.; Ade, C.M.; Ortego, J.C.; Stark, J.; Deininger, P.L.; Roy-Engel, A.M. Heavy Metal Exposure Influences Double Strand Break DNA Repair Outcomes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Mitra, M.; Agarwal, P.; Mahapatra, K.; De, S.; Sett, U.; Roy, S. Oxidative and Genotoxic Damages in Plants in Response to Heavy Metal Stress and Maintenance of Genome Stability. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2018, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.-J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.-N.; Sun, X.; Hai, C.-X.; Hudson, L.G.; Liu, K.J. Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1 Inhibition by Arsenite Promotes the Survival of Cells With Unrepaired DNA Lesions Induced by UV Exposure. Toxicological Sciences 2012, 127, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Parihar, P.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Heavy Metal Tolerance in Plants: Role of Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics, and Ionomics. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwóźdź, E.A.; Przymusiński, R.; Rucińska, R.; Deckert, J. Plant Cell Responses to Heavy Metals: Molecular and Physiological Aspects. Acta Physiol Plant 1997, 19, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A. Defense Responses of Plant Cell Wall Non-Catalytic Proteins against Pathogens. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2016, 94, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, A.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, F.; Wu, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wen, D.; Liu, X. Silicon Improves Growth and Alleviates Oxidative Stress in Rice Seedlings (Oryza Sativa L.) by Strengthening Antioxidant Defense and Enhancing Protein Metabolism under Arsanilic Acid Exposure. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 158, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, T.; Nakagawa, Y. Preface to the Special Issue: Brief Review of Plant Hormones and Their Utilization in Agriculture. Journal of Pesticide Science 2018, 43, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Araniti, F.; Bali, A.S.; Shahzad, B.; Tripathi, D.K.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Landi, M. The Role of Salicylic Acid in Plants Exposed to Heavy Metals. Molecules 2020, 25, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, V.; Ravindran, P.; Kumar, P.P. Plant Hormone-Mediated Regulation of Stress Responses. BMC Plant Biol 2016, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bücker-Neto, L.; Paiva, A.L.S.; Machado, R.D.; Arenhart, R.A.; Margis-Pinheiro, M. Interactions between Plant Hormones and Heavy Metals Responses. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2017, 40, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Deng, F.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.; Gao, W.; Long, L.; Xia, J.; Chen, Z.-H. Evolution of Abscisic Acid Signaling for Stress Responses to Toxic Metals and Metalloids. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, H.I.; Sofy, M.R.; Almoneafy, A.A.; Abdelhamid, M.T.; Basit, A.; Sofy, A.R.; Lone, R.; Abou-El-Enain, M.M. Role of Microorganisms in Managing Soil Fertility and Plant Nutrition in Sustainable Agriculture. In Plant Growth-Promoting Microbes for Sustainable Biotic and Abiotic Stress Management; Mohamed, H.I., El-Beltagi, H.E.-D. S., Abd-Elsalam, K.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.K.; Tripathi, S.; Tiwari, I.; Shrestha, J.; Modi, B.; Paudel, N.; Das, B.D. Role of Soil Microbes in Sustainable Crop Production and Soil Health: A Review. AST 2021, 13, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Narayanan, M.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Natarajan, D.; Ma, Y. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria in Metal-Contaminated Soil: Current Perspectives on Remediation Mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 966226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Henao, S.; Ghneim-Herrera, T. Heavy Metals in Soils and the Remediation Potential of Bacteria Associated With the Plant Microbiome. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 604216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhu, W.; Amombo, E.; Lou, Y.; Chen, L.; Fu, J. Effect of Heavy Metals Pollution on Soil Microbial Diversity and Bermudagrass Genetic Variation. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhatib, R.; Mheidat, M.; Abdo, N.; Tadros, M.; Al-Eitan, L.; Al-Hadid, K. Effect of Lead on the Physiological, Biochemical and Ultrastructural Properties of Leucaena Leucocephala. Plant Biol J 2019, 21, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, R.; Maruthavanan, J.; Ghoshroy, S.; Steiner, R.; Sterling, T.; Creamer, R. Physiological and Ultrastructural Effects of Lead on Tobacco. Biologia plant. 2012, 56, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Duan, C. Effects of Heavy Metals on Stomata in Plants: A Review. IJMS 2023, 24, 9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Growth and Physiological Responses of Pennisetum Sp. to Cadmium Stress under Three Different Soils. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 14867–14881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.S.; Cortez, P.A.; De Almeida, A.-A. F.; Prasad, M.N.V.; França, M.G.C.; Da Cunha, M.; De Jesus, R.M.; Mangabeira, P.A.O. Morphology, Ultrastructure, and Element Uptake in Calophyllum Brasiliense Cambess. (Calophyllaceae J. Agardh) Seedlings under Cadmium Exposure. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 15576–15588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghipour, O. Cadmium Toxicity Alleviates by Seed Priming with Proline or Glycine Betaine in Cowpea ( Vigna Unguiculata (L.) Walp.). Egypt. J. Agron. 2020, 0, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudsar, T.; Arshi, A.; Siddiqi, T.O.; Mahmooduzzafar; Iqbal, M. Zinc-Induced Changes in Growth Characters, Foliar Properties, and Zn-Accumulation Capacity of Pigeon Pea at Different Stages of Plant Growth. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2008, 31, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, R.-R.; Qiu, R.-L.; Tang, Y.-T.; Hu, P.-J.; Qiu, H.; Chen, H.-R.; Shi, T.-H.; Morel, J.-L. Cadmium Tolerance of Carbon Assimilation Enzymes and Chloroplast in Zn/Cd Hyperaccumulator Picris Divaricata. Journal of Plant Physiology 2010, 167, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires-Lira, M.F.; De Castro, E.M.; Lira, J.M.S.; De Oliveira, C.; Pereira, F.J.; Pereira, M.P. Potential of Panicum Aquanticum Poir. (Poaceae) for the Phytoremediation of Aquatic Environments Contaminated by Lead. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 193, 110336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.A. Cadmium-Induced Structural Disturbances in Pea Leaves Are Alleviated by Nitric Oxide. Turk J Bot 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.; Chen, Z.-H.; Amtmann, A.; Blatt, M.R.; Lew, V.L. OnGuard, a Computational Platform for Quantitative Kinetic Modeling of Guard Cell Physiology. Plant Physiology 2012, 159, 1026–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; Chwil, M. Lead-Induced Histological and Ultrastructural Changes in the Leaves of Soybean ( Glycine Max (L.) Merr.). Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2005, 51, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancheva, I.; Geneva, M.; Markovska, Y.; Tzvetkova, N.; Mitova, I.; Todorova, M.; Petrov, P. A Comparative Study on Plant Morphology, Gas Exchange Parameters, and Antioxidant Response of Ocimum Basilicum L. and Origanum Vulgare L. Grown on Industrially Polluted Soil. Turk J Biol 2014, 38, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Y.; Tang, L.; Sohail, M.I.; Cao, X.; Hussain, B.; Aziz, M.Z.; Usman, M.; He, Z.; Yang, X. An Explanation of Soil Amendments to Reduce Cadmium Phytoavailability and Transfer to Food Chain. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 660, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ai, S.; Zhang, W.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y. Assessment of the Bioavailability, Bioaccessibility and Transfer of Heavy Metals in the Soil-Grain-Human Systems near a Mining and Smelting Area in NW China. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 609, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zhu, G.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Y. Accumulation and Bioavailability of Heavy Metals in a Soil-Wheat/Maize System with Long-Term Sewage Sludge Amendments. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2018, 17, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.-Y.; Yoon, J.-K.; Kim, T.-S.; Yang, J.E.; Owens, G.; Kim, K.-R. Bioavailability of Heavy Metals in Soils: Definitions and Practical Implementation—a Critical Review. Environ Geochem Health 2015, 37, 1041–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feszterová, M.; Porubcová, L.; Tirpáková, A. The Monitoring of Selected Heavy Metals Content and Bioavailability in the Soil-Plant System and Its Impact on Sustainability in Agribusiness Food Chains. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Cadmium in Food - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain. EFS2 2009, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Aslam, A.; Sheraz, M.; Ali, B.; Ulhassan, Z.; Najeeb, U.; Zhou, W.; Gill, R.A. Lead Toxicity in Cereals: Mechanistic Insight Into Toxicity, Mode of Action, and Management. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 587785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielecke, F.; Nugent, A.P. Contaminants in Grain—A Major Risk for Whole Grain Safety? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandravanshi, L.; Shiv, K.; Kumar, S. Developmental Toxicity of Cadmium in Infants and Children: A Review. Environ Anal Health Toxicol 2021, 36, e2021003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhani, I.; Sahab, S.; Srivastava, V.; Singh, R.P. Impact of Cadmium Pollution on Food Safety and Human Health. Current Opinion in Toxicology 2021, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Akhtar, M.J.; Zahir, Z.A.; Mitter, B. Organic Amendments: Effects on Cereals Growth and Cadmium Remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 2919–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M.; Montemurro, F. Olive Pomace Compost in Organic Emmer Crop: Yield, Soil Properties, and Heavy Metals’ Fate in Plant and Soil. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2019, 19, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärenlampi, S.; Schat, H.; Vangronsveld, J.; Verkleij, J.A.C.; Van Der Lelie, D.; Mergeay, M.; Tervahauta, A.I. Genetic Engineering in the Improvement of Plants for Phytoremediation of Metal Polluted Soils. Environmental Pollution 2000, 107, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Tan, X.; Fu, H.-L.; Chen, J.-X.; Lin, X.-X.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.-Y. Selection for Cd Pollution-Safe Cultivars of Chinese Kale ( Brassica Alboglabra L. H. Bailey) and Biochemical Mechanisms of the Cultivar-Dependent Cd Accumulation Involving in Cd Subcellular Distribution. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 1923–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.A.; Zang, L.; Ali, B.; Farooq, M.A.; Cui, P.; Yang, S.; Ali, S.; Zhou, W. Chromium-Induced Physio-Chemical and Ultrastructural Changes in Four Cultivars of Brassica napus L. Chemosphere 2015, 120, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Sharma, S.; Vats, S.; Ali, S.; Kumar, S.; Gulzar, N.; Deshmukh, R. Translational Research Using CRISPR/Cas. In CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing; Bhattacharya, A., Parkhi, V., Char, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Ahmad Dar, A.; Skalicky, M.; Tyagi, A.; Bhagat, N.; Basu, U.; Bhat, B.A.; Zaid, A.; Ali, S.; Dar, T.-U.-H.; Rai, G.K.; Wani, S.H.; Habib-Ur-Rahman, M.; Hejnak, V.; Vachova, P.; Brestic, M.; Çığ, A.; Çığ, F.; Erman, M.; El Sabagh, A. CRISPR-Based Genome Editing Tools: Insights into Technological Breakthroughs and Future Challenges. Genes 2021, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Dar, A.A.; Basu, U.; Bhat, B.A.; Mir, R.A.; Vats, S.; Dar, M.S.; Tyagi, A.; Ali, S.; Bansal, M.; Rai, G.K.; Wani, S.H. Integrating CRISPR-Cas and Next Generation Sequencing in Plant Virology. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 735489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- asu, U.; Riaz Ahmed, S.; Bhat, B.A.; Anwar, Z.; Ali, A.; Ijaz, A.; Gulzar, A.; Bibi, A.; Tyagi, A.; Nebapure, S.M.; Goud, C.A.; Ahanger, S.A.; Ali, S.; Mushtaq, M. A CRISPR Way for Accelerating Cereal Crop Improvement: Progress and Challenges. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 866976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.K.; Kumar, N.; Singh, N.P.; Santal, A.R. Phytoremediation Technologies and Their Mechanism for Removal of Heavy Metal from Contaminated Soil: An Approach for a Sustainable Environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1076876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamagoos, A.A.; Mallhi, Z.I.; El-Esawi, M.A.; Rizwan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Hussain, A.; Alharby, H.F.; Alharbi, B.M.; Ali, S. Alleviating Lead-Induced Phytotoxicity and Enhancing the Phytoremediation of Castor Bean ( Ricinus Communis L.) by Glutathione Application: New Insights into the Mechanisms Regulating Antioxidants, Gas Exchange and Lead Uptake. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2022, 24, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Pu, L.; Li, A.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, P.; Xu, X.; Lei, N.; Chen, J. Implication of Exogenous Abscisic Acid (ABA) Application on Phytoremediation: Plants Grown in Co-Contaminated Soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 8684–8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-Y.; Wang, Y.-S.; Ying, G.-G. Cadmium-Inducible BgMT2, a Type 2 Metallothionein Gene from Mangrove Species (Bruguiera Gymnorrhiza), Its Encoding Protein Shows Metal-Binding Ability. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2011, 405, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, F.; Zhong, H.; Jiang, W.; Li, X. Identification and Expression Analysis of Genes in Response to High-Salinity and Drought Stresses in Brassica Napus. ABBS 2010, 42, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ju, T.; Cheng, W. Cadmium Toxicity and Translocation in Rice Seedlings Are Reduced by Hydrogen Peroxide Pretreatment. Plant Growth Regul 2009, 59, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, F.; Bhat, J.A.; Hu, J.; Kaushik, P.; Ahmad, A.; Guan, Y.; Ahmad, P. Brassinosteroid Supplementation Alleviates Chromium Toxicity in Soybean (Glycine Max L.) via Reducing Its Translocation. Plants 2022, 11, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.; Ali, S.; Abid, M.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, B.; Tanveer, A.; Ahmad, I.; Azam, M.; Ghani, M.A. Glycinebetaine Alleviates the Chromium Toxicity in Brassica Oleracea L. by Suppressing Oxidative Stress and Modulating the Plant Morphology and Photosynthetic Attributes. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jamil, H.M.A.; Hayat, M.T.; Mahmood, Q.; Ali, S. Use of Phytohormones to Improve Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Wheat. In Wheat Production in Changing Environments; Hasanuzzaman, M., Nahar, K., Hossain, Md. A., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, S.H.; Ashraf, M.A.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Rasheed, R. Menadione Sodium Bisulfite Alleviated Chromium Effects on Wheat by Regulating Oxidative Defense, Chromium Speciation, and Ion Homeostasis. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 36205–36225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Suzui, N.; Yin, Y.-G.; Ishii, S.; Fujimaki, S.; Kawachi, N.; Rai, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato-Izawa, K.; Ohkama-Ohtsu, N. Effects of Enhancing Endogenous and Exogenous Glutathione in Roots on Cadmium Movement in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Science 2020, 290, 110304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, M.A.; Hao, Y.; Mehmood, S.; Shu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, W.; Chen, C.; Li, L.; Altaf, M.A.; Wang, Z. Physiological and Transcriptomic Analysis Provide Molecular Insight into 24-Epibrassinolide Mediated Cr(VI)-Toxicity Tolerance in Pepper Plants. Environmental Pollution 2022, 306, 119375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, T.; Suhel, M.; Prasad, S.M.; Singh, V.P. Ethylene and Hydrogen Sulphide Are Essential for Mitigating Hexavalent Chromium Stress in Two Pulse Crops. Plant Biol J 2022, 24, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Wang, D.; Alhaithloul, H.A.S.; Alghanem, S.M.; Aftab, T.; Xie, K.; Lu, Y.; Shi, C.; Sun, J.; Gu, W.; Xu, P.; Soliman, M.H. Jasmonic Acid-Mediated Enhanced Regulation of Oxidative, Glyoxalase Defense System and Reduced Chromium Uptake Contributes to Alleviation of Chromium (VI) Toxicity in Choysum (Brassica Parachinensis L.). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 208, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Pu, S.; Xiong, X.; Chen, S.; Peng, L.; Fu, J.; Sun, L.; Guo, B.; Jiang, M.; Li, X. Melatonin-Assisted Phytoremediation of Pb-Contaminated Soil Using Bermudagrass. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 44374–44388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Xin, C.; Si, J.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, H.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, L.; Wang, F. Nano-ZnO Priming Induces Salt Tolerance by Promoting Photosynthetic Carbon Assimilation in Wheat. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2020, 66, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Wang, X.; Shi, C.; Guo, J.; Ma, P.; Ren, X.; Wei, T.; Liu, H.; Li, J. Hydrogen Sulfide Decreases Cd Translocation from Root to Shoot through Increasing Cd Accumulation in Cell Wall and Decreasing Cd2+ Influx in Isatis Indigotica. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2020, 155, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Yin, X.; Song, G.; Cai, Q. Exogenous Glutathione Alleviation of Cd Toxicity in Italian Ryegrass (Lolium Multiflorum) by Modulation of the Cd Absorption, Subcellular Distribution, and Chemical Form.

- Jan, S.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wijaya, L.; Alam, P.; Siddique, K.H.; Ahmad, P. Interactive Effect of 24-Epibrassinolide and Silicon Alleviates Cadmium Stress via the Modulation of Antioxidant Defense and Glyoxalase Systems and Macronutrient Content in Pisum Sativum L. Seedlings. BMC Plant Biol 2018, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, W.; Chen, W.; He, Z.; Gurajala, H.K.; Hamid, Y.; Deng, M.; Yang, X. Field Crops (Ipomoea Aquatica Forsk. and Brassica Chinensis L.) for Phytoremediation of Cadmium and Nitrate Co-Contaminated Soils via Rotation with Sedum Alfredii Hance. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2017, 24, 19293–19305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Farooq, M.; Ozturk, L.; Asif, M.; Siddique, K.H.M. Zinc Nutrition in Wheat-Based Cropping Systems. Plant Soil 2018, 422, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Navarro, A.; Salas-Sanjuan, M.D.C.; Blanco-Bernardeau, M.A.; Sánchez-Romero, J.A.; Delgado-Iniesta, M.J. Medium-Term Effect of Organic Amendments on the Chemical Properties of a Soil Used for Vegetable Cultivation with Cereal and Legume Rotation in a Semiarid Climate. Land 2023, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazarji, M.; Bayero, M.T.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; Mandzhieva, S.; Tereshchenko, A.; Timofeeva, A.; Bauer, T.; Burachevskaya, M.; Kızılkaya, R.; Gülser, C.; Keswani, C. Realizing United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for Greener Remediation of Heavy Metals-Contaminated Soils by Biochar: Emerging Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Features | Impact on HM Toxicity | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil pH | Soil acidity/alkalinity affects the metal solubility. Acidic soils (pH < 7) increase solubility and bioavailability of metals like Cd, Al, Mn, etc. Alkaline soil reduces the solubility by precipitating metals. | Acidic soil increases metal uptake; alkaline soil reduces uptake but may cause nutrient deficiencies. | [80,81,82,83] |

| Soil organic matter | Decomposed plant and animal residues bind with metal ions (chelation). Humic and fulvic acids form stable complexes with metals. Supports beneficial microorganisms like mycorrhizae. | Reduces heavy metal mobility and uptake; improves soil structure and microbial health. | [80,81,84] |

| Soil texture | Texture (proportions of sand, silt, and clay) affects retention/release of metals. Clay soils adsorb metals strongly; sandy soils have low absorption, causing higher mobility. | Clay limits uptake via immobilization; sandy soils increase uptake due to leaching and mobility. | [80,85,86] |

| Plant species & varieties | Various species differ in heavy metal tolerance and detoxification. Examples: Barley and rye show higher tolerance. Low-cadmium rice varieties b[80,92,93red to limit Cd in grains. Root hair and exudates also play roles. | Tolerant variety limit translocation; breeding can reduce grain contamination. | [80,87,88] |

| Soil metal concentration | Higher metal concentration increases uptake and toxicity. Exceeding toxicity threshold affects plants growth and food safety. Interactions between metals (synergistic effects) can intensify toxicity. | Elevated metal levels cause tissue damage and grain contamination; metal synergy worsens toxicity. | [80,89,90] |

| Temperature | High temperatures increase metal solubility and uptake by crops. Heatwaves enhance mobility of metals like Cd and Pb. | Increased risk of uptake and toxicity during high-temperature periods. | [80,91] |

| Humidity | High humidity may cause waterlogging and increase metal diffusion. Low humidity reduces water uptake, intensifying toxicity. | Waterlogged soils promote uptake; dry conditions exacerbate stress from existing heavy metal presence. | [80,92,93] |

| Water availability | Influences dilution or concentration of heavy metal in soil solutions. Adequate water reduces toxicity; drought increases risk. | Water scarcity heightens metal uptake; proper irrigation reduces availability of toxic metals. | [80,94] |

| Transporter/Channel | Function | Specificity/Substrate | Additional Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtIRT1 | Plasma membrane metal transporter | Broad specificity for divalent metals (e.g., Fe2+, Zn2+, Cd2+) | Present in the outer root layer; absorbs metals from the soil | [98,99] |

| TcZNT1/TcZIP4 | Zn transporter; low-affinity Cd uptake | High-affinity for Zn; low-affinity for Cd | Mediates Cd and Zn uptake when expressed in roots | [98] |

| OsNRAMP1/OsNRAMP5 | Cd and Fe influx transporter | Fe2+, Cd2+ | Plasma membrane localized; involved in Cd uptake | [98,100] |

| AtNRAMP6 | Intracellular metal transporter | Cd2+ | Functions inside the cell rather than at plasma membrane | [98] |

| TaLCT1 |

Influx cation transporter |

Ca2+, Cd2+, K+ | Broad substrate specificity; Cd transport inhibited by high Ca2+ or Mg2+ | [98] |

| DACCs (Depolarization-activated Ca2+ channels) | Ca2+ influx channel | Non-selective for cations (including Cd2+) | Activated at −80 mV; unstable and appear infrequently | [98,101] |

| HACCs (Hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ channels) | Ca2+ influx; guard cell signalling | Non-selective (includes Cd2+) | Involved in response to ABA, light, and elicitors | [98] |

| VICCs (Voltage-independent Ca2+ channels) | Ca2+ and Cd2+ influx | Likely overlap with DACCs and HACCs functions | [98] | |

| YSL (Yellow Stripe-Like) | Transport of nicotinamide (NA)-metal chelates | NA–Fe, NA–Cd complexes | Oligopeptide transporter; induced under Fe deficiency | [98,102] |

| Category | Effect of Cadmium Toxicity | Mechanism/Detail | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorosis | Yellowing of leaves | Disrupts chlorophyll synthesis by inhibiting enzymes like δ-aminolaevulinic [80,111,112acid dehydratase (ALAD) and protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO) | [80,111,112] |

| Stunted Growth | Reduced plant size and growth | Impairs root elongation and nutrient uptake, and interferes with growth hormone (auxins and gibberellin) synthesis | [80,113] |

| Reduced Root Growth | Inhibited root elongation and branching | Causes ROS accumulation in roots, disrupts cell division and elongation | [80,114] |

| Nutrient Uptake Interference | Leads to deficiencies in essential elements like zinc | Competes with zinc for uptake, reducing zinc availability | [80,114] |

| Leaf Deformities | Twisting, curling, and irregular leaf shapes | Interferes with gibberellin biosynthesis and causes oxidative stress | [80,115] |

| Reduced Flowering | Delayed flowering | Disrupts cytokinin signalling | [80,116] |

| Reduced Fruit Development | Smaller and malformed fruits | Competes with zinc, impacting zinc-dependent processes essential for fruit development | [80] |

| Necrosis | Formation of necrotic lesions and tissue death | Induces ROS accumulation, causing oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA | [80,117] |

| Water Stress | Wilting and reduced water uptake | Restricts root elongation, disrupts root cell membranes, and affects water transport mechanisms | [80,118,119] |

| Category | Effect of Lead Toxicity | Mechanism/Detail | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorosis | Yellowing of leaves | Inhibits chlorophyll biosynthesis by disrupting enzymes and metabolic pathways | [80,111] |

| Stunted Growth | Reduced plant height and biomass | Interferes with elongation in roots and shoots and cell division, and disrupts nutrient/water uptake | [80,113] |

| Hormonal Disruption | Impaired growth regulation | Inhibits synthesis of growth hormones like auxins and gibberellins | [80] |

| Reduced Flowering | Decreased flower development and elongation of flower stalks | Inhibits gibberellin biosynthesis | [80,116] |

| Necrosis | Formation of necrotic lesions in leaves and tissues | Leads to ROS production, oxidative stress, and subsequent cell death | [80,117] |

| Mechanism | Physiological/molecular effects | Heavy metals involved | Effects/observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA metabolism disruption | Causes DNA strand breaks, chromosomal aberrations, and inhibition of replication and repair enzymes; leads to genomic instability. | Cr, Cd, Pb, As, Hg | Arsenic inhibits poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1; Cd and Pb induce double-strand break in Vicia faba; Hg binds covalently to DNA causing sister chromatid exchange and mitotic disruptions. | [36,137,138,139] |

| Altered gene expression | Modifies expression of metal transporters (HMA, ZIP, NRAMP, ABC), signalling genes (MAPKs), and transcription factors; disrupts metabolic and defense gene regulation. | Cd, Zn, Hg, Cu, Pb | Cd interferes with Zn-finger TFs; barley overexpresses dehydration-related TFs under Cd and Hg stress; gene overexpression enhances metal uptake and phytoremediation potential. | [140,141,142,143] |

| Hormonal deregulation | Disrupts balance of growth and stress hormones (auxins, gibberellins, cytokinin, ABA, JA); alters signalling pathways affecting growth and defense. | Cd, Pb, Hg, Cu, Zn, Ni | Exogenous kinetin reduces Cd toxicity (Pisum sativum); GA3 alleviates Pb/Cd stress (Vicia faba, Lupinus albus); IAA and SA restore antioxidant activity in wheat; BSs mitigate Cd stress in tomato; ABA accumulation restricts metal translocation but inhibits growth. | [144,145,146,147,148] |

| Inhibition of soil microorganism | Reduces microbial biomass, diversity, and enzymatic activity essential for nutrient cycling; disturbs rhizosphere balance and soil fertility. | Zn, Cu, Pb, Cd, Hg | Inhibition of CO2 evolution due to impaired microbial respiration; decline in dehydrogenase activity and basal respiration; molecular analysis (16S/18S rRNA) reveals shifts in microbial community structure. | [149,150,151,152,153] |

| Overall impact on plant growth | Combined disruption of genetic stability, hormonal signalling, and soil microbial support leads to stunted growth, reduced photosynthesis, and poor yield quality. | Majority of heavy metals | Integrative stress effects on plant physiology, metabolism, and soil–plant–microbe interactions. | [13,147,150,152,153] |

| Priming Agent/Compound | Mode of Action/Mechanism | Plant Species Studied | Overall Impact on Cr Stress | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABA, Glutathione (GSH), Cysteine, Sulphur, Melatonin | Enhance detoxification processes, stimulate antioxidant enzyme systems, and limit Cr uptake | Various crops | Reduced oxidative stress and improved tolerance to Cr toxicity | [11,187,200] |

| Metallothioneins (MTs) | Chelate and immobilize Cr ions via thiol-rich ligands; upregulation of MT-related genes under stress | Brassica napus | Enhanced Cr detoxification and protection of cellular components | [11,189] |

| Hydrogen Sulphide (H2S) | Boosts antioxidant activity, upregulates MT genes, increases chlorophyll and thiol content, and promotes Cr-binding peptide synthesis | B. napus, Barley, Arabidopsis | Reduced lipid peroxidation, enhanced photosynthesis, and improved metal tolerance | [11,191,201,202] |

| 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (ALA) | Stimulates chlorophyll synthesis, improves metabolism, and decreases Cr accumulation | B. napus | Enhanced growth and photosynthetic efficiency under Cr exposure | [11,190] |

| Taurine | Protects lipid membranes, enhances ROS scavenging, improves nutrient assimilation and osmolyte accumulation | Triticum aestivum | Increased biomass, membrane stability, and stress tolerance | [11,193] |

| Mannitol (M) | Acts as an Osmo protectant, decreases Cr translocation, and activates antioxidant enzymes | Triticum aestivum | Lowered Cr content and improved photosynthetic pigment levels | [11,194] |

| Glutathione (GSH) | Forms Cr–GSH complexes, neutralizes ROS via the ASA–GSH cycle, and limits Cr translocation | Glycine max | Maintained chlorophyll, higher biomass, and effective detoxification | [11,195,203] |

| Indole Acetic Acid (IAA) | Modulates antioxidant enzymes and hormonal signalling to minimize oxidative injury | Pisum sativum | Reduced ROS accumulation and improved stress resistance | [11,197,198] |

| Jasmonic Acid (JA) | Strengthens antioxidant and glyoxalase systems, maintains Ca2+ balance, and limits Cr uptake | Brassica parachinensis, P. sativum | Improved mineral homeostasis and lower Cr accumulation | [11,199,204] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).