Submitted:

28 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

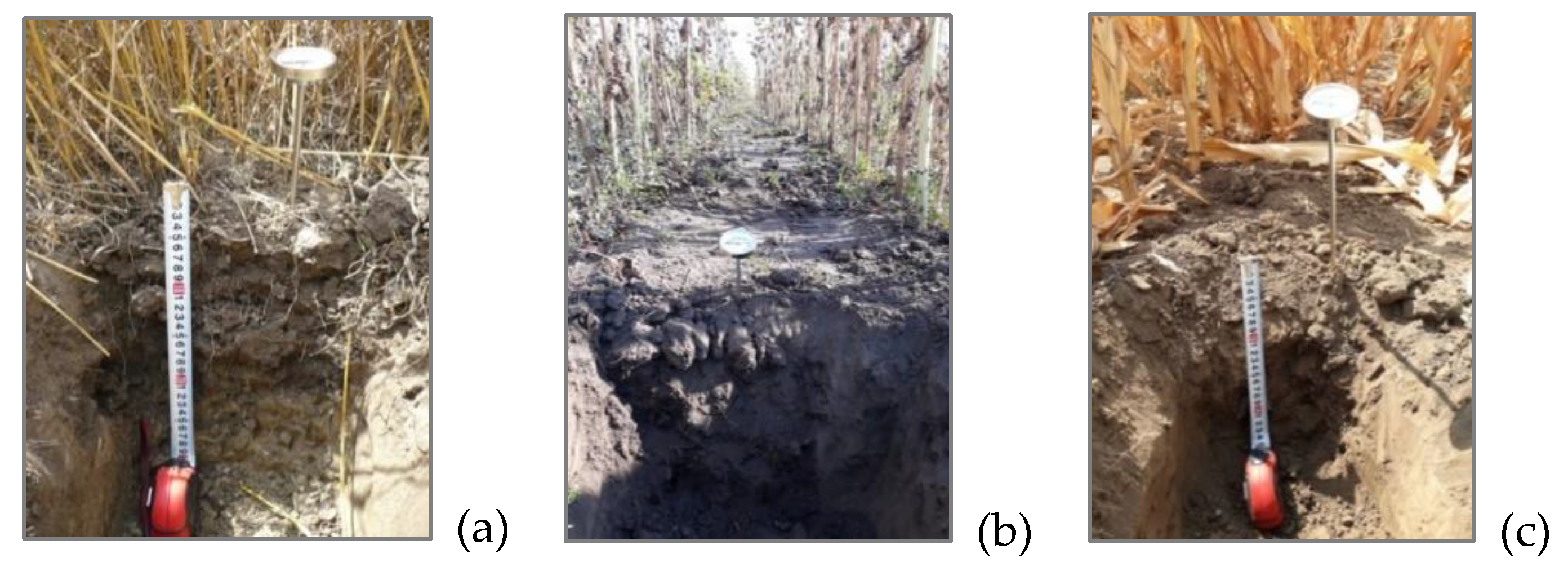

2.2. Soil Sampling and Plants Collection

2.3. Soil and Plants Analysis

2.4. Pollution and Health Risk Assessment

Plant Bioaccumulation of Major and Trace Elements

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Assessment of Soil Main Parameters Which Influence Elemental Bioavailability

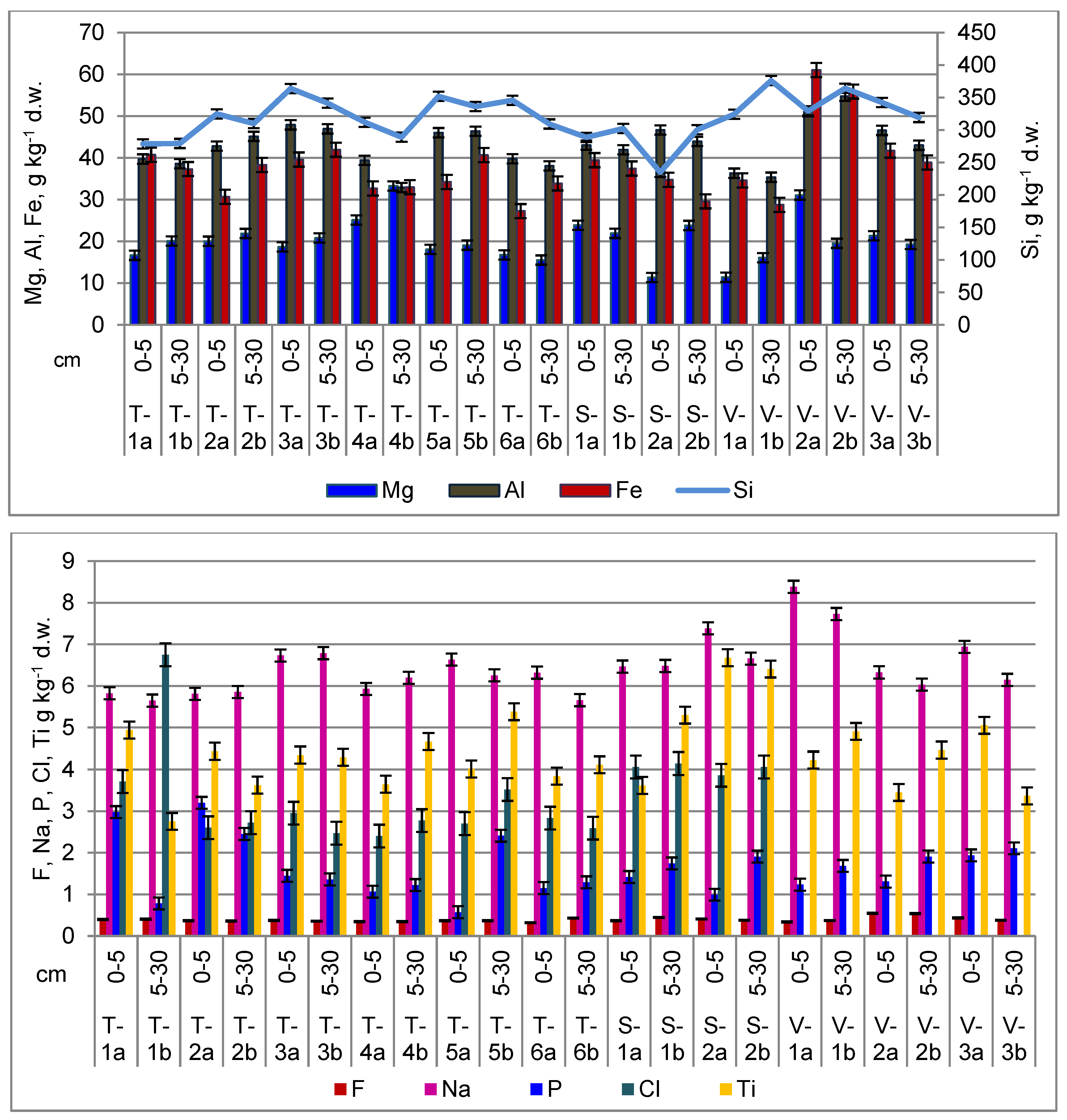

3.2. Major and Trace Elements Assessment in Soil

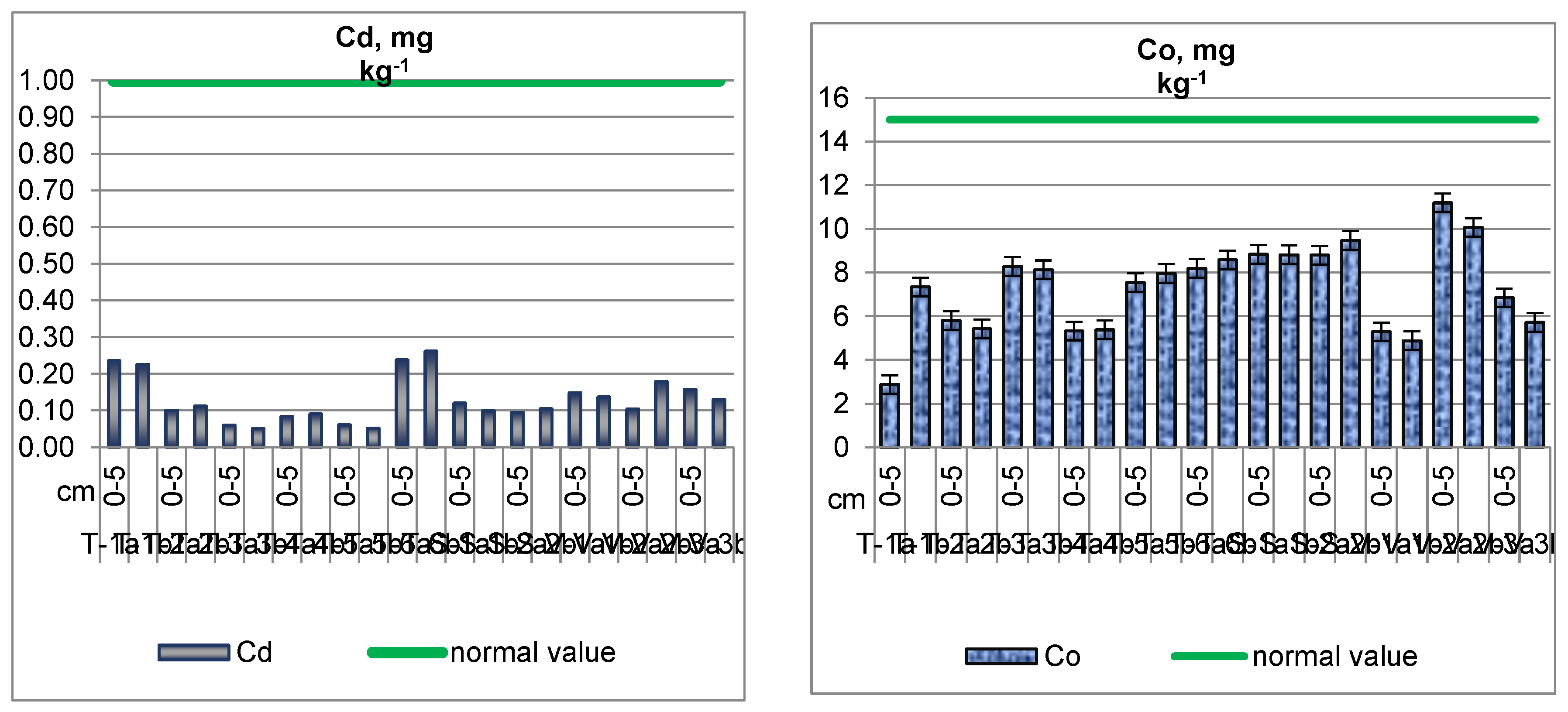

Cadmium (Cd) in Soil

Cobalt (Co) in Soil

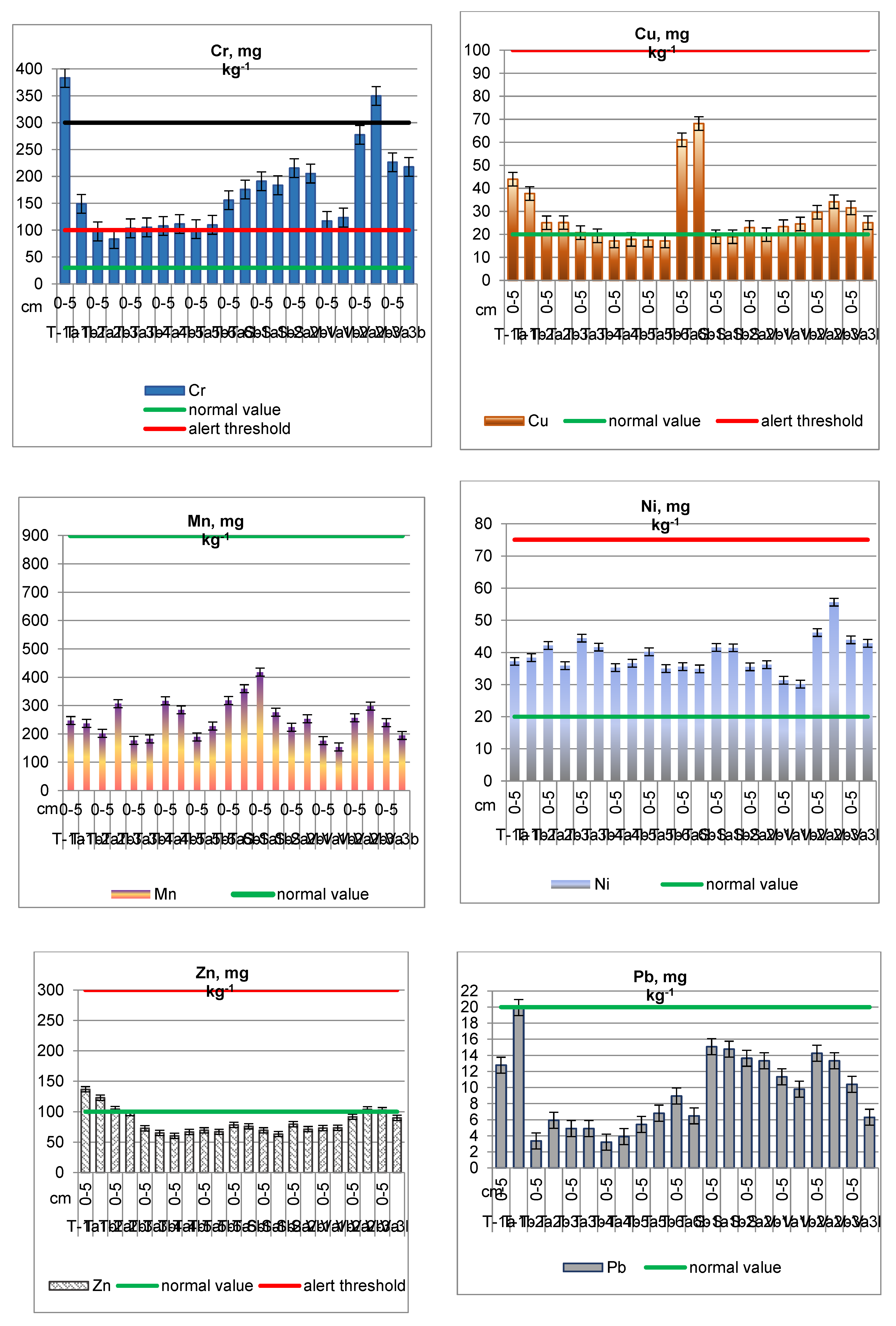

Chromium (Cr) in Soil

Copper (Cu) in Soil

Manganese (Mn) in Soil

Nickel (Ni) in Soil

Zinc (Zn) in Soil

Lead (Pb) in Soil

Other Major and Trace Elements in Soil

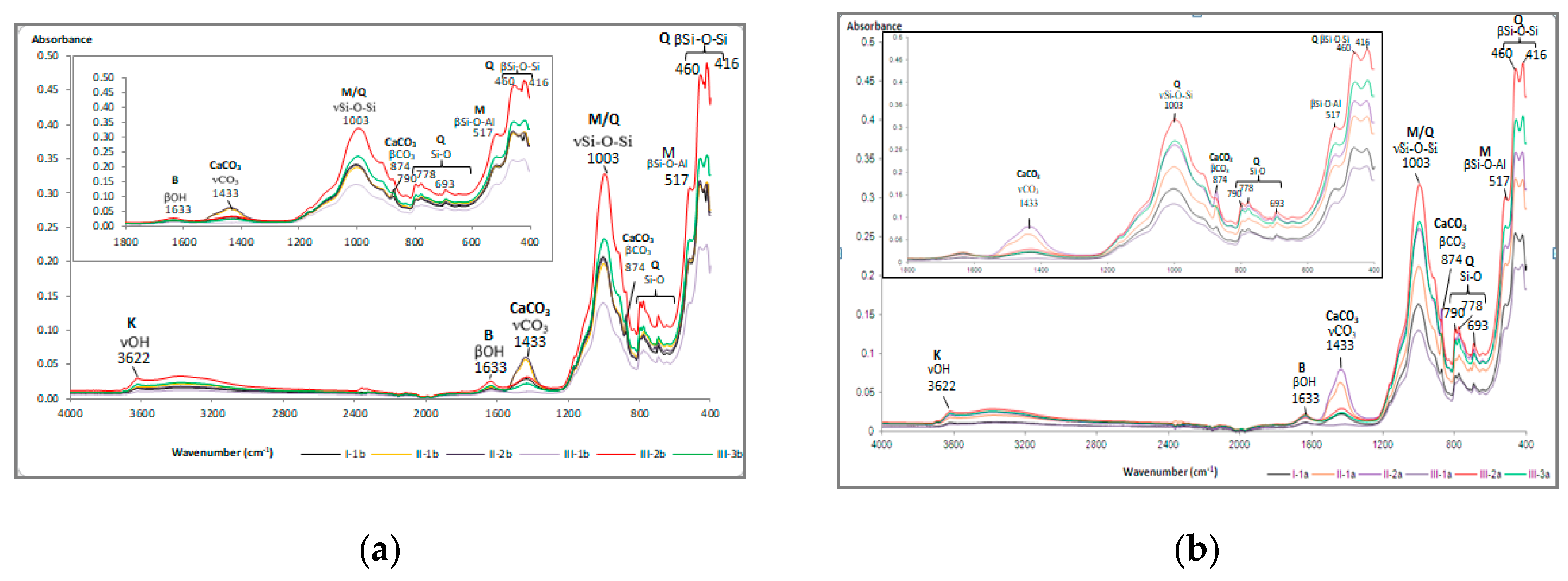

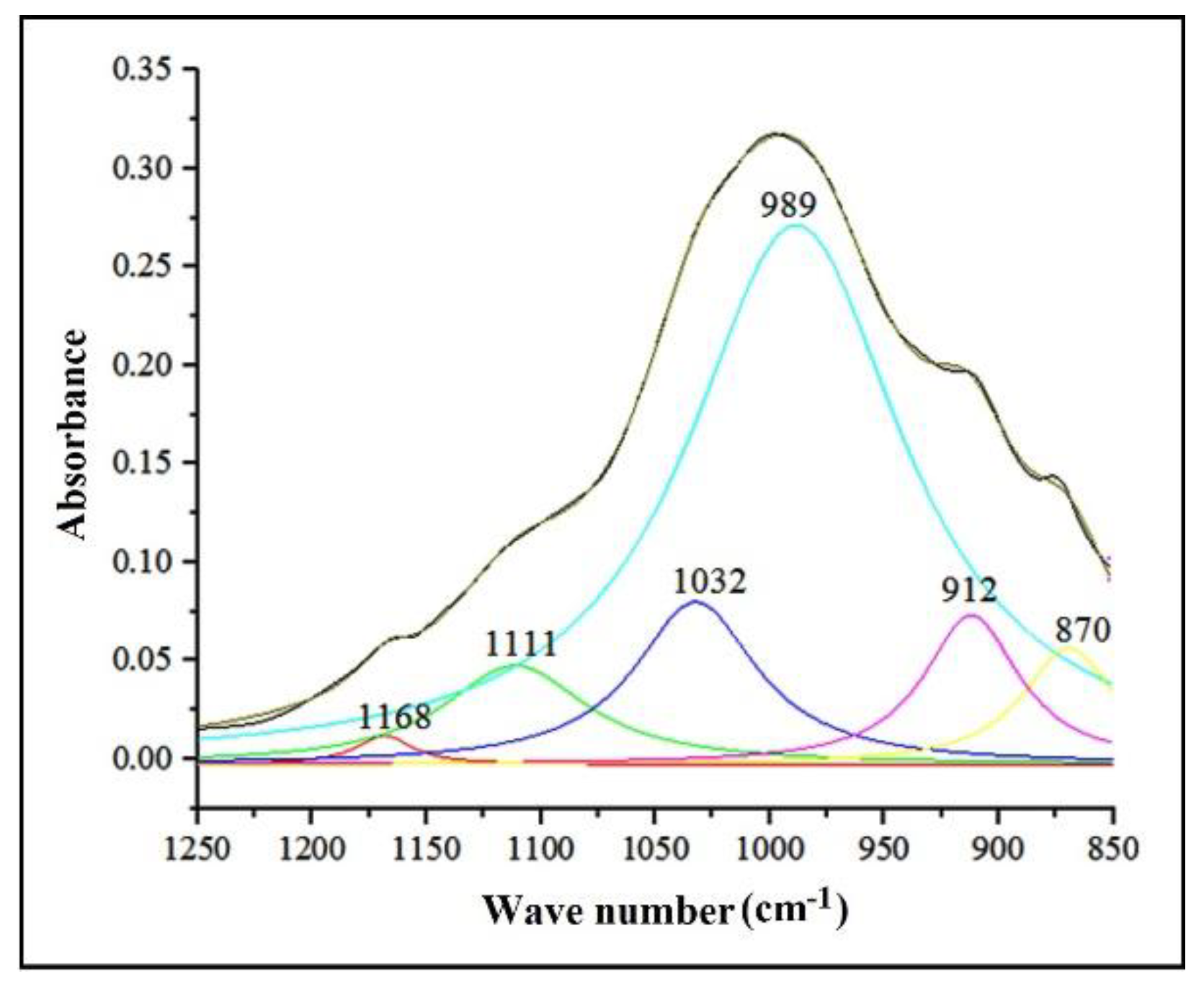

3.3. Mineralogical and Microstructural Analysis of Soil

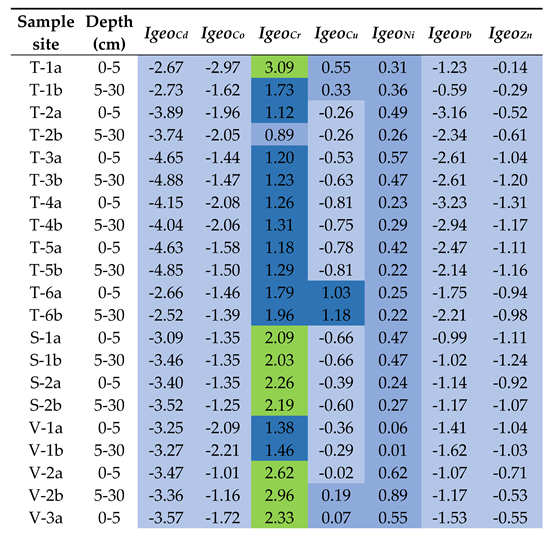

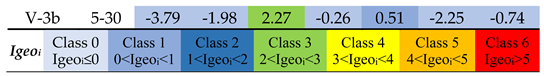

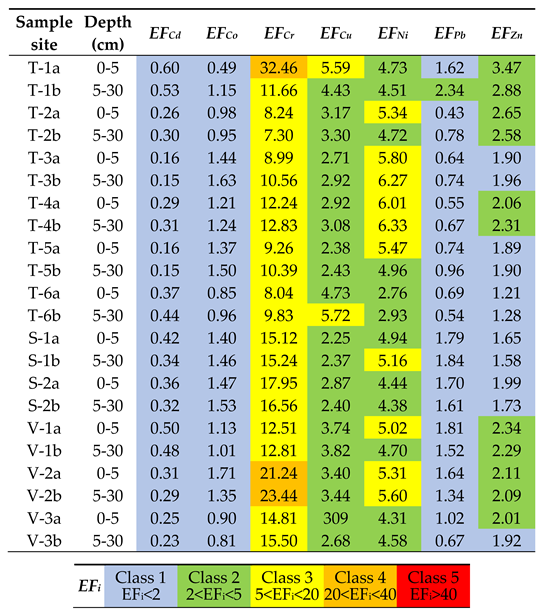

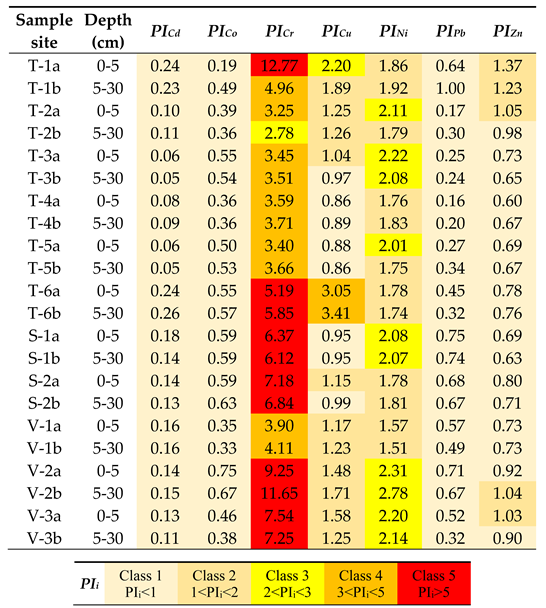

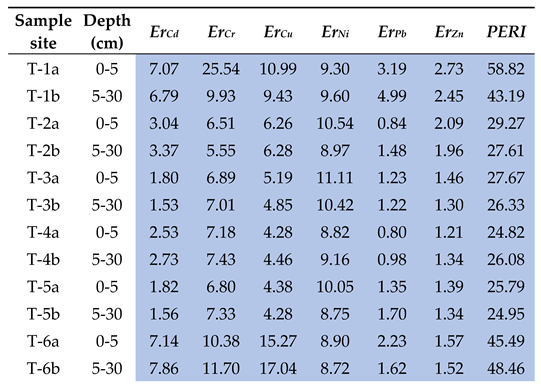

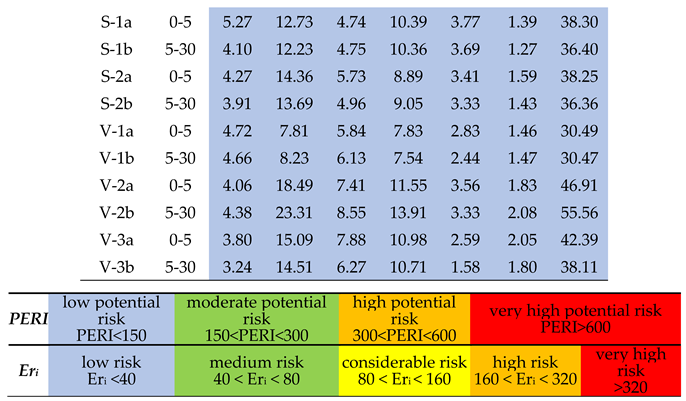

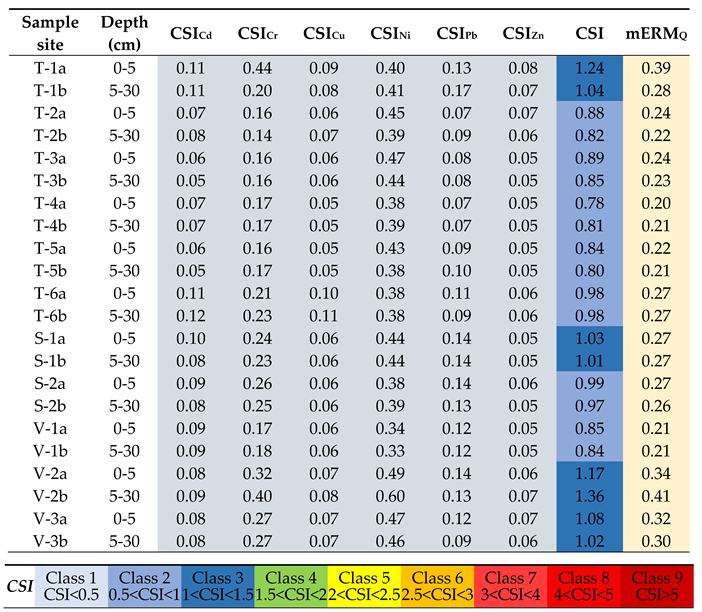

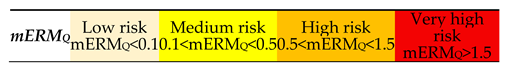

3.4. Assessment of Soil Contamination

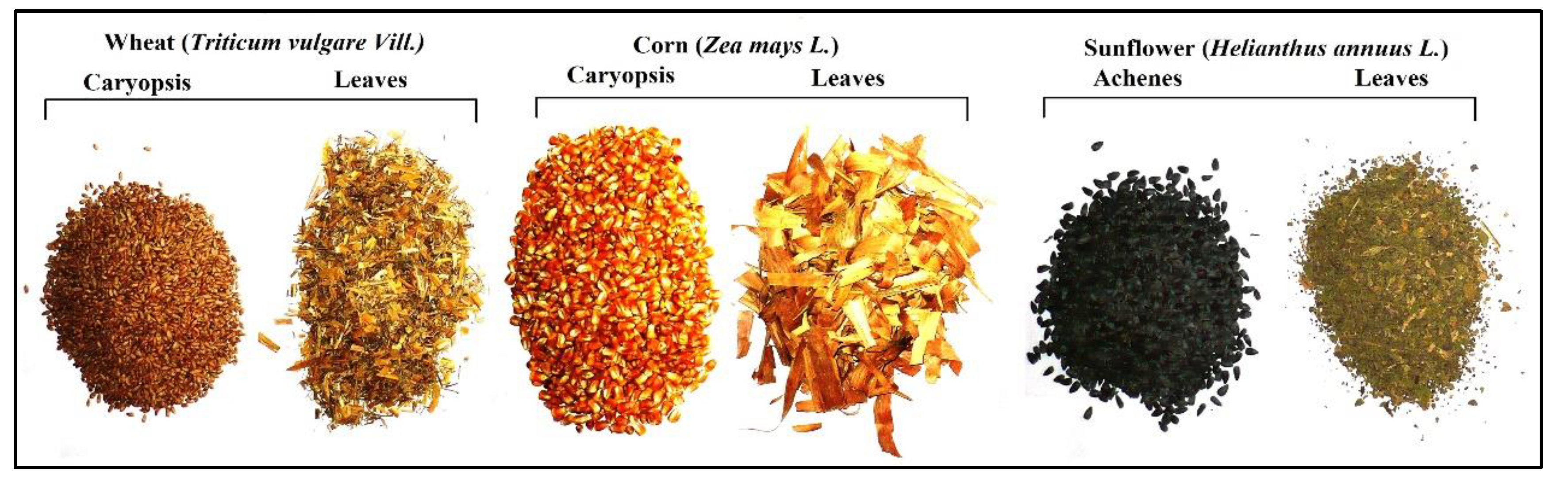

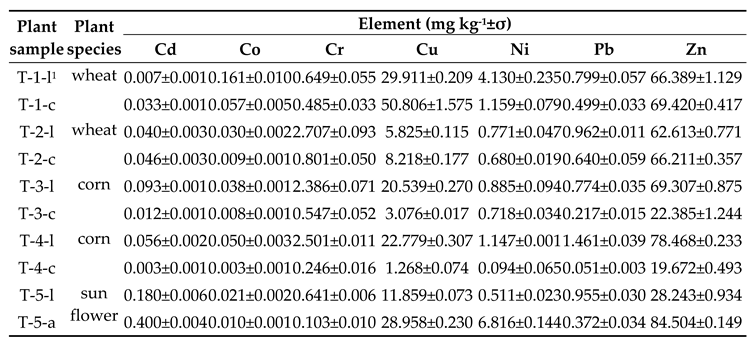

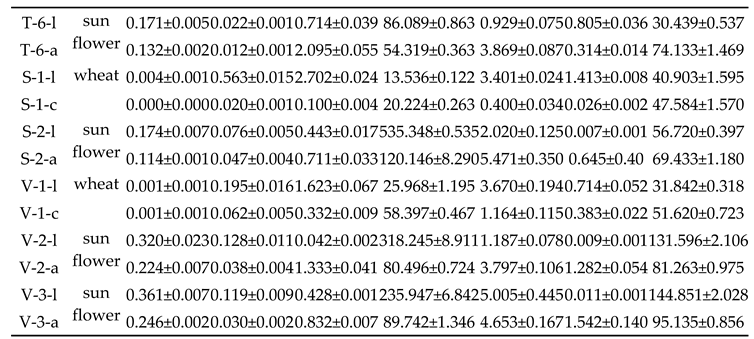

3.5. Major and Trace Elements Assessment in Crops

Cadmium in Plants

Cobalt in Plants

Chromium in Plants

Copper in Plants

Nickel in Plants

Lead in Plants

Zinc in Plants

Other Trace Elements in Plants

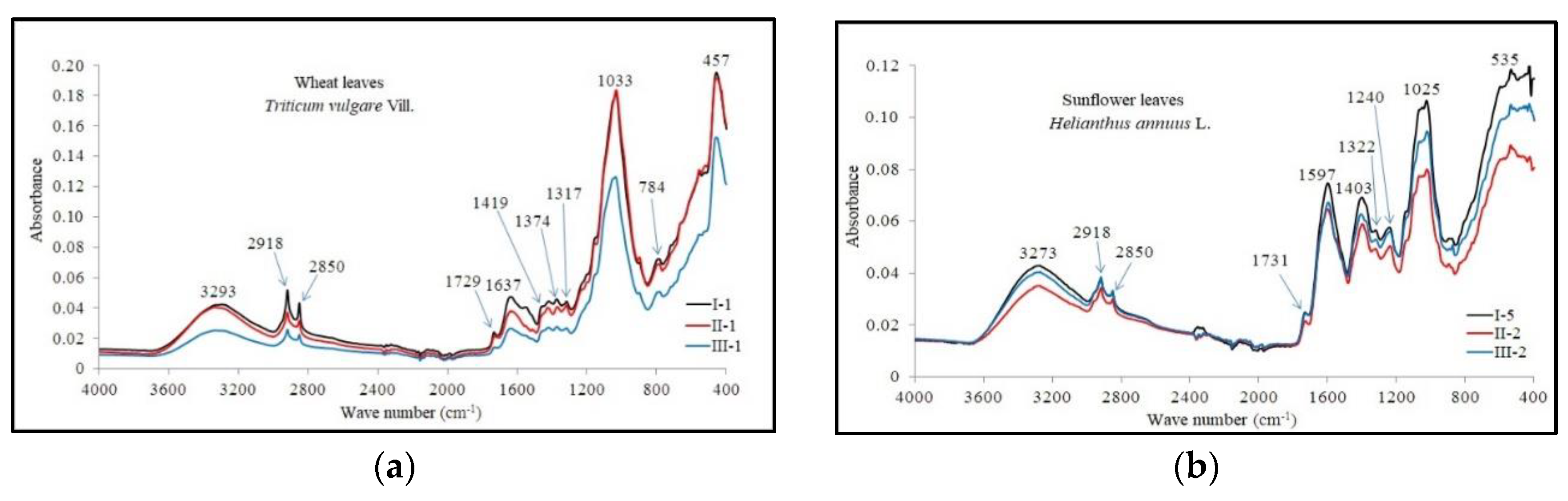

3.6. The Organic Compounds Found in Crops

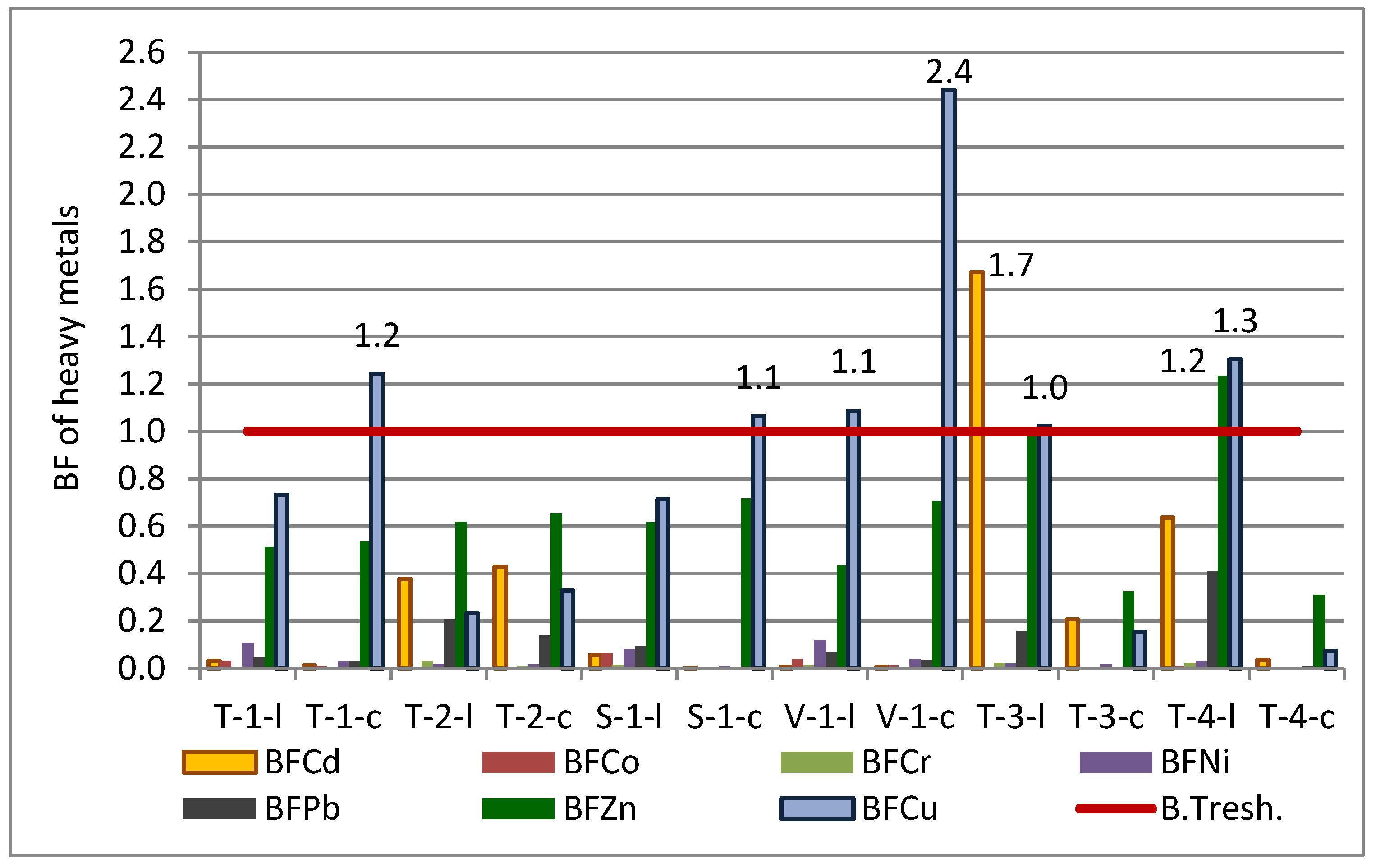

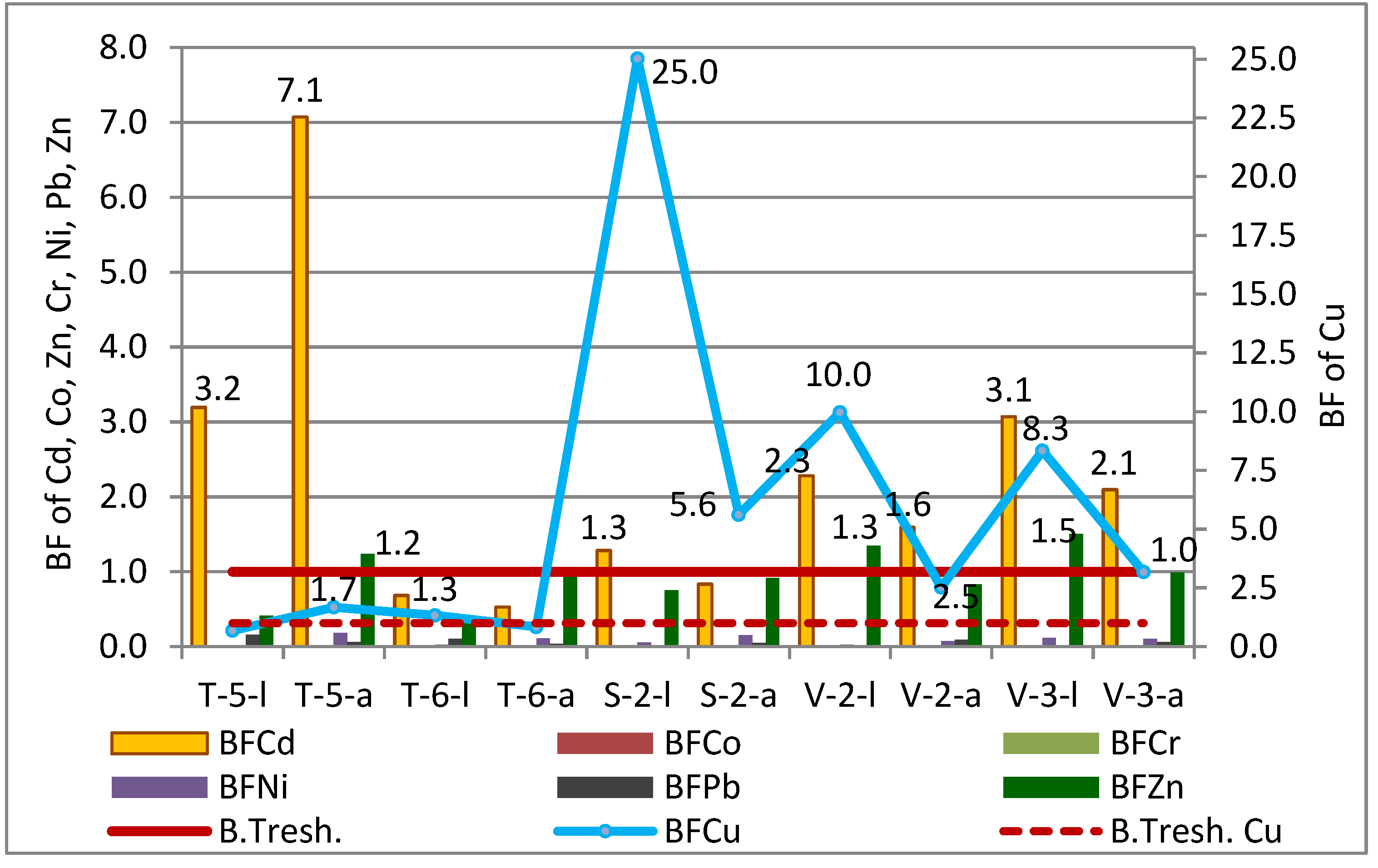

3.7. The Bioaccumulation of Elements in Crops

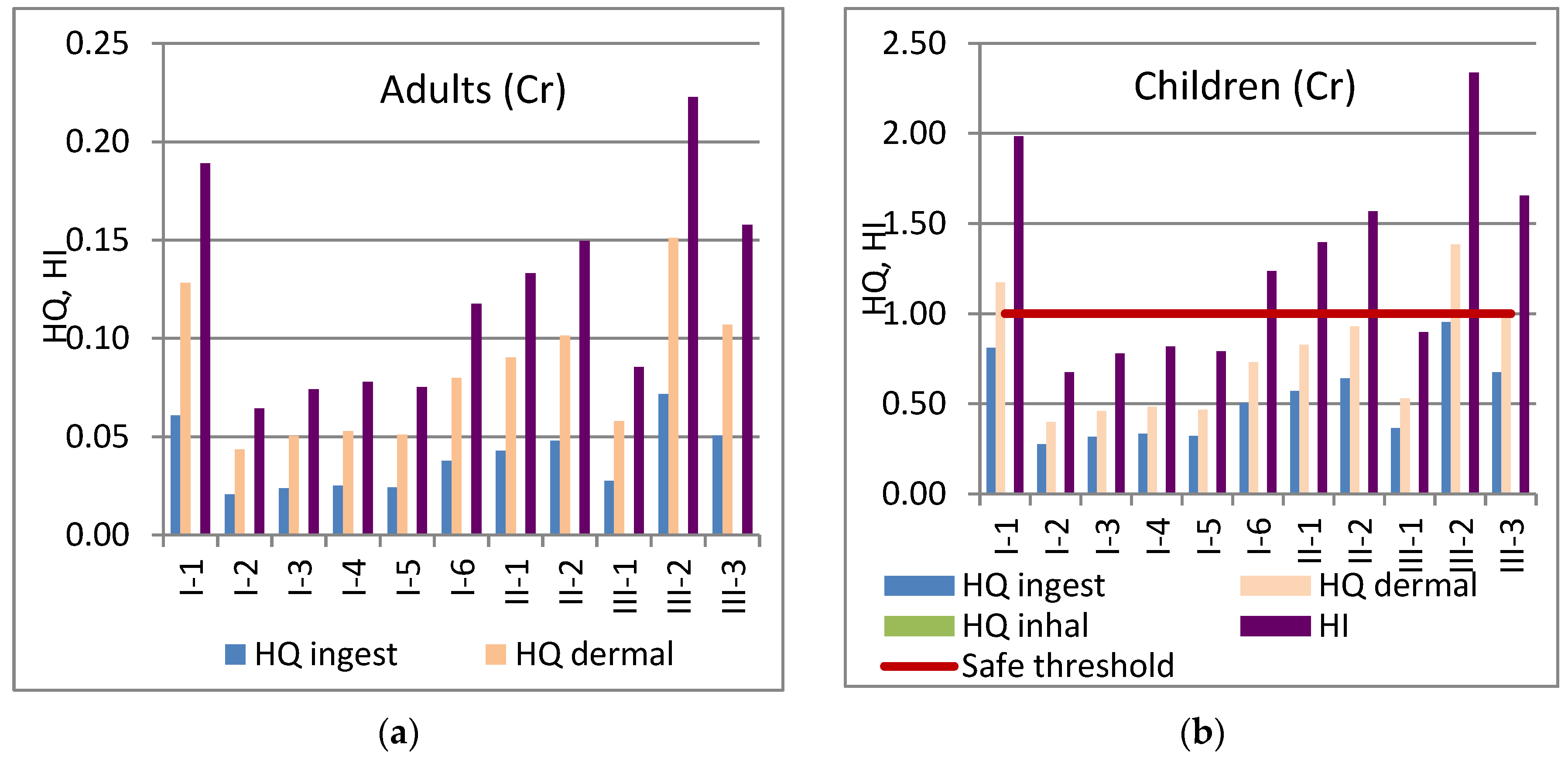

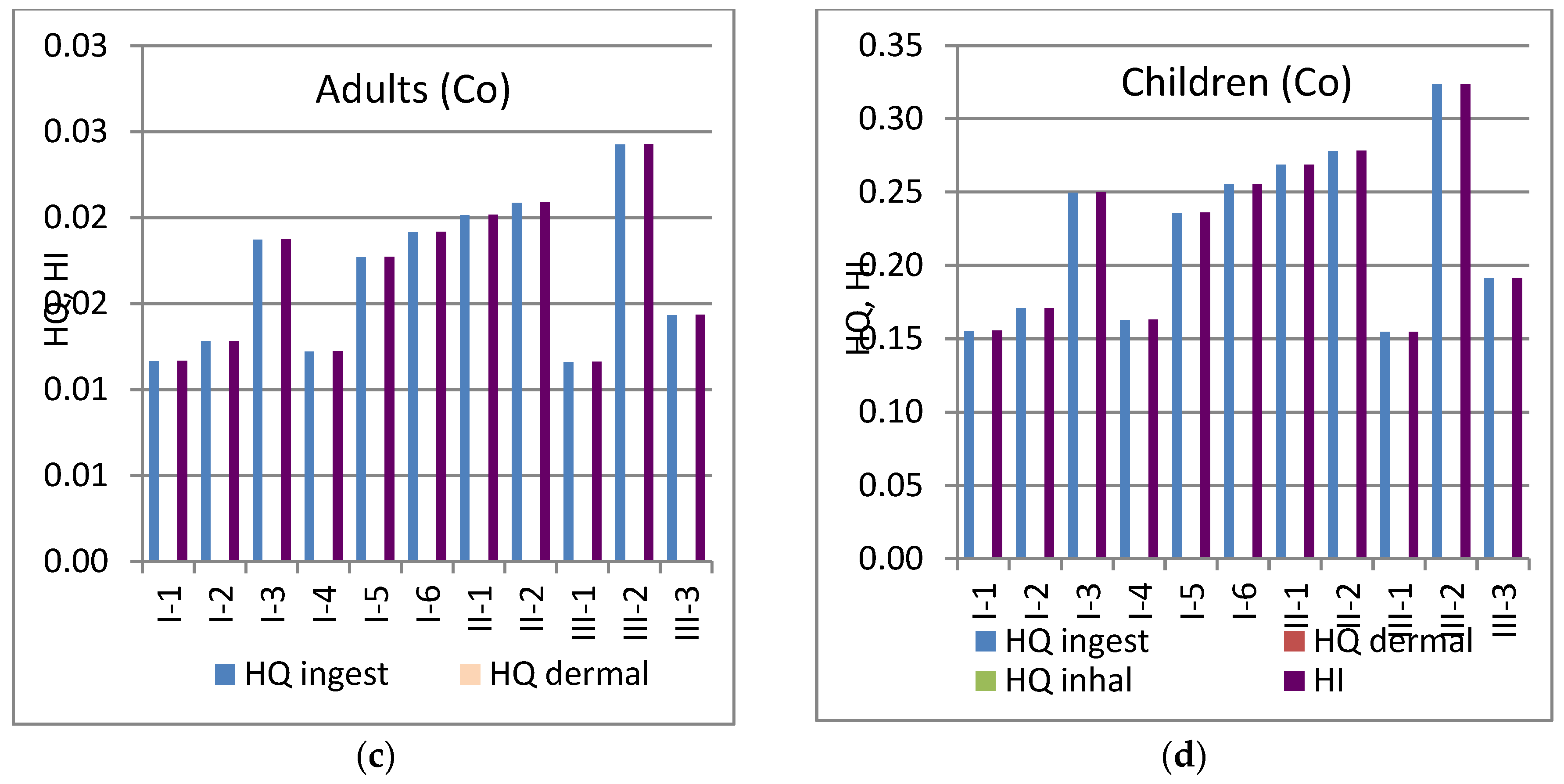

3.8. Health Risk Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Elements | Tulucesti | Sendreni | Vadeni | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-5 cm | 5-30 cm | 0-5 cm | 5-30 cm | 0-5 cm | 5-30 cm | |

| Average Concentration (wt %) | ||||||

| C | 10.86 | 9.96 | 10.63 | 11.88 | 10.14 | 14.82 |

| N | 1.50 | * | * | * | * | 0.87 |

| O | 41.63 | 39.75 | 38.17 | 39.17 | 36.10 | 28.84 |

| Na | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.62 |

| Mg | 1.32 | 1.54 | 1.31 | 1.46 | 1.07 | 1.03 |

| Al | 6.33 | 7.77 | 6.02 | 6.74 | 7.06 | 10.74 |

| Si | 23.83 | 22.60 | 22.44 | 20.84 | 25.28 | 26.27 |

| P | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.16 |

| S | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.04 |

| Cl | 0.07 | * | * | * | * | * |

| K | 2.59 | 3.33 | 1.63 | 1.77 | 3.57 | 3.43 |

| Ca | 3.58 | 3.64 | 4.67 | 6.26 | 1.69 | 2.69 |

| Ti | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.88 |

| V | * | * | * | 0.20 | * | * |

| Cr | 0.23 | * | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.49 | * |

| Mn | 0.27 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 0.67 | * |

| Gd | * | 1.46 | 1.33 | 0.87 | 1.59 | * |

| Fe | 4.04 | 5.08 | 4.02 | 5.07 | 5.52 | 8.35 |

| Co | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 1.27 |

| Ni | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.56 | * |

| Cu | * | * | 1.08 | 0.78 | 1.05 | * |

| Zn | 1.14 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.36 | * |

| Ga | * | 1.09 | 1.14 | 1.03 | 1.42 | * |

| Hg | * | * | 3.40 | * | * | * |

| Elements | Triticum vulgareVill. | Zea maysL. | Helianthus annuusL. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Concentration (wt %) | |||

| C | 59.76 | 65.65 | 74.61 |

| N | 3.50 | 2.60 | * |

| O | 24.80 | 23.18 | 18.49 |

| Na | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| Mg | 0.20 | 0.22 | * |

| Al | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.06 |

| Si | 0.10 | 0.07 | * |

| P | 0.60 | 0.48 | * |

| S | 0.40 | 0.33 | * |

| Cl | 0.10 | 0.03 | * |

| K | * | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Ca | 0.40 | 0.21 | 1.93 |

| Ti | * | 0.04 | 1.46 |

| V | * | 0.03 | * |

| Cr | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Mn | 0.10 | 0.14 | * |

| Fe | 0.20 | 0.27 | * |

| Co | 0.30 | 0.18 | * |

| Ni | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.19 |

| Cu | 0.90 | 1.18 | 0.17 |

| Zn | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.09 |

| Pb | 6.18 | 3.71 | 2.57 |

| Hg | 1.24 | * | * |

References

- Arbanas (Moraru), S.-S. Research on iron and steel works industry impact on soil edaphic and vegetal potential in the adjacent areas (Cercetări privind impactul activităţilor industriei siderurgice asupra potenţialului edafic and vegetal al solurilor din zonele adiacente – in Romanian). PhD Thesis, Dunarea de Jos University of Galati. Romania. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y. The Impact of Vegetation Roots on Shallow Stability of Expansive Soil Slope under Rainfall Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2023. 13, 11619. [CrossRef]

- Blum, W.E.H. Functions of Soil for Society and the Environment, Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio 2005. 4, 75. 75-79. [CrossRef]

- Trap, J.; Bonkowski, M.; Plassard, C.; Villenave, C.; Blanchart, E. Ecological importance of soil bacterivores for ecosystem functions, Plant Soil 2016. 398. 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Jakubus, M.; Bakinowska, E. The Effect of Immobilizing Agents on Zn and Cu Availability for Plants in Relation to Their Potential Health Risks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Lia, F. Temporal Variations of Heavy Metal Sources in Agricultural Soils in Malta. Appl. Sci. 2022. 12, 3120. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. Microbial-Based Heavy Metal Bioremediation: Toxicity and Eco-Friendly Approaches to Heavy Metal Decontamination. Appl. Sci. 2023. 13, 8439. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ouyang, T.; Guo, Y.; Peng, S.; He, C.; Zhu, Z. Assessment of Soil Heavy Metal Pollution and Its Ecological Risk for City Parks, Vicinity of a Landfill, and an Industrial Area within Guangzhou, South China. Appl. Sci. 2022. 12, 9345. [CrossRef]

- Ene, A.; Sloată, F.; Frontasyeva, M.V.; Duliu, O.G.; Sion, A.; Gosav, S.; Persa, D. Multi-elemental Characterization of Soils in the Vicinity of Siderurgical Industry: Levels, Depth Migration and Toxic Risk. Preprints 2024. 2024040668. accepted in Minerals on 25 May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Order of the Minister of Water, Forest and Environmental Protection no. 184/21.09.1997 for the approval of the Procedure for the elaboration of environmental assessment, Official Monitor of Romania no. 303bis from 6.11.1997 (in Romanian). Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/11971.

- Benton Jones Jr., J. Chapter 2. Field Sampling Procedures for Conducting a Plant Analysis. In Handbook of Reference Methods for Plant Analysis. Tissue Tests. Let plant speak. Kalra, Y.P. CRC Press. Taylor and Francis Group, USA, 1998; pp. 25-36.

- SR ISO 11466:1999. Soil quality. Extraction of trace elements soluble in aqua regia.

- SR 7184/13:2001. Soils. Determination of pH in water and saline suspensions (mass/volume) and in saturated paste.

- STAS 7184/21-82. Soils. Determination of humus content.

- SR EN ISO 10693:2014. Soil quality. Determination of carbonate content. Volumetric method.

- Borlan, Z.; Rauta, C. (editors). Methodology for agrochemical analysis of soils to establish the need for amendments and fertilizers. Methods of chemical analysis of soils. Methods, guidance reports Series, ICPA. Bucharest. Romania. 1981; Volume I. Part I. (in Romanian).

- SR ISO 11265+A1:1998. Soil quality. Determination of the specific electrical conductivity.

- STAS 7184/7-87. Soils. Determination of mineral salts of 1:5 aqueous extract.

- STAS 7184/10-79. Soils. Determination of granulometric composition.

- SR ISO 11465:1998. Soil quality. Determination of dry matter and water content on a mass basis. Gravimetric method.

- Caprita, F.-C.; Ene, A.; Cantaragiu Ceoromila, A. Valorification of Ulva rigida Algae in Pulp and Paper Industry for Improved Paper Characteristics and Wastewater Heavy Metal Filtration. Sustainability 2021. 13, 19, 10763. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W.; Bian, P.; Zhang, S. Source and Migration Pathways of Heavy Metals in Soils from.

- an Iron Mine in Baotou City, China. Minerals 2024. 14, 506. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, B.; Tian, M.; Cheng, X.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Y. Enrichment Characteristics and Ecological Risk Assessment of.

- Heavy Metals in a Farmland System with High Geochemical Background in the Black Shale Region of Zhejiang, China. Minerals 2024. 14, 375. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Jaskuła, J.; Sojka, M.; Fiedler, M.; Wróżyński, R. Analysis of Spatial Variability of River Bottom Sediment Pollution with Heavy Metals and Assessment of Potential Ecological Hazard for the Warta River, Poland. Minerals 2021, 11, 327. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Dou, C.; Cui, H.; Zhang, W.; Yu, W.; Sheng, X.; Zheng, X. Copper and Cadmium Accumulation and Phytorextraction Potential of Native and Cultivated Plants Growing around a Copper Smelter. Agronomy 2023. 13, 2874. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-Y.; Jiao, S.-L.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.-J.; Yang, M.; Feng, Y.-L.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.-X. Characteristics and Release Risk of Phosphorus from Sediments in a Karst Canyon Reservoir, China. Appl. Sci. 2024. 14, 2482. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Fakhruddin, A.N.M.; Toufick Imam, M.D.; Khan,. N.; Khan, T.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Abdulah, A.T.M. Spatial distribution and source identification of heavy metals pollution in roadside surface soil: a study of Dhaka Aricha highway, Bangladesh. Ecol.Process. 2016. 5, 2. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Caeiro, S.; Costa, M.H.; Ramos, T.B.; Fernandes, F.; Silveira, N.; Coimbra, A.; Medeiros, G.; Painho, M. Assessing heavy metal contamination in Sado Estuary sediment: An index analysis approach. Ecol. Indic. 2005. 5. 151-169. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.A. Bed sediment-associated trace metals in an urban stream, Oahu, Hawaii. Environ. Geol. 2000. 39, 6. 611-627. [CrossRef]

- Awadh, S.M.; Al-Hamdani, J.A.JM.Z. Urban geochemistry assessment using pollution indices: a case study of urban soil in Kirkuk, Iraq. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019. 78, 587. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.B.; Mazurek, R.; Gąsiorek, M.; Zaleski, T. Pollution indices as useful tools for the comprehensive evaluation of the degree of soil contamination-A review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2018. Springer, 4. 2395-2420. [CrossRef]

- Műller, G. Index of geoaccumulation in sediments of the Rhine River. GeoJournal 1969. 108-118.

- Nikolaidis, C.; Zafiriadis, I.; Constantinidis, T. Heavy Metal Pollution Associated with an Abandoned Lead-Zinc Mine in the Kirki Region, NE Greece. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010. 85. 307-312. [CrossRef]

- Håkanson, L. An Ecological Risk Index for Aquatic Pollution Control: A Sedimentological Approach. Water Res. 1980. 14. 975-1101. [CrossRef]

- Pejman, A.; Bidhendi, G.N.; Ardestani, M.; Saeedi, M.; Baghvand, A. A new index for assessing heavy metals contamination in sediments: A case study. Ecol. Indic. 2015. 58. 365-373. [CrossRef]

- El-Alfy, M.A.; El-Amier, Y.A.; El-Eraky, T.E. Land use/cover and eco-toxicity indices for identifying metal contamination in sediments of drains, Manzala Lake, Egypt. Heliyon 2020. 6. e03177. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, E.R.; MacDonald, D.D.; Smith, S.; Calder, F.D. Incidence of Adverse Biological Effects Within Ranges of Chemical Concentrations in Marine and Estuarine Sediments. Environ. Manage. 1995. 19, 1. 81-97. [CrossRef]

- Olowoyo, J.O.; van Heerden, E.; Fischer, J.L.; Baker, C. Trace elements in soil and leaves of Jacaranda mimosifolia in Tshwane area, South Africa. Atmos. Environ. 2010. 44. 1826-1830. [CrossRef]

- Mirecki, N.; Rukie Agič, R.; Šunić, L.; Milenković, L.; Ilić, Z.S. Transfer factor as indicator of heavy metals content in plants, Fresenius Environ. Bul. 2015. PSP, 24, 11c. 4212-4219.

- USEPA, California Department of Toxic Substances Control (DRSC), Office of Human and Ecological Risk (HERO), Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) Note number 1: Recommended DTSC Default Exposure Factors for Use in Risk Assessment at California Hazardous Waste Sites and Permitted Facilities, April 9, 2019.

- https://dtsc.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2022/02/HHRA-Note-1-April-2019-21A.pdf.

- Ackah, M. Soil elemental concentrations, geoaccumulation index, non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks in functional areas of an informal e-waste recycling area in Accra, Ghana. Chemosphere 2019. 235. 907-917.

- . [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhao, W.; Yan, X.; Shu, T.; Xiong, Q.; Chen, F. Pollution Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Airborne Heavy Metals Collected from Beijing Bus Stations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9658–9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveena, S.M.; Pradhan, B.; Aris, A.Z. Assessment of bioavailability and human health exposure risk to heavy metals in surface soils (Klang district, Malaysia). Toxin Rev. 2017. 37, 3. 196-205. [CrossRef]

- Slaboch, J.; Malý, M. Land Valuation Systems in Relation to Water Retention. Agronomy 2023. 13, 2978. 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Qin, X.; Xu, C.; Yan, X. Effects of Soil pH on the Growth and Cadmium Accumulation in Polygonum hydropiper (L.) in Low and Moderately Cadmium-Contaminated Paddy Soil. Land 2023. 12, 652. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Vaziriyeganeh, M.; Zwiazek, J.J. Effects of pH and Mineral Nutrition on Growth and Physiological Responses of Trembling Aspen (Populus tremuloides), Jack Pine (Pinus banksiana), and White Spruce (Picea glauca) Seedlings in Sand Culture. Plants 2020. 9, 682. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk-Szabela, D.; Wolf, W.M. The Impact of Soil pH on Heavy Metals Uptake and Photosynthesis Efficiency in Melissa officinalis, Taraxacum officinalis, Ocimum basilicum. Molecules 2022. 27, 4671. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Pikuła, D.; Stępień, W. Effect of the Degree of Soil Contamination with Heavy Metals on Their Mobility in the Soil Profile in a Microplot Experiment. Agronomy 2021. 11, 878. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Malik, S.A.; Saeed, S.; Rehman, A.-u.; Munir, T.M. Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals by Various Vegetable Crops Cultivated on Different Textured Soils Irrigated with City Wastewater. Soil Syst. 2021. 5, 35. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Arbanas (Moraru), S.-S.; Ene, A. Nutrient stocks study in agroecosystems located near the steel industry, Galati, Romania, Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Mathematics, Physics, Theoretical Mechanics, Fascicle II 2020. 43(2). 82-93.

- Moraru, S.-S.; Ene, A.; Badila, A. Physical and Hydro-physical Characteristics of Soil in the Context of Climate Change. A Case Study in Danube River Basin, SE Romania. Sustainability 2020. 12, 9174. 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Chapter 3. Soils and Soils Processes. In Trace elements in soils and plants, 4th ed., CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group. USA. 2011; 37-63.

- Cullen, J.T.; Maldonado, M.T. Chapter 2. Biogeochemistry of Cadmium and Its Release to the Environment. In Cadmium: From Toxicity to Essentiality, Sigel. A.; Sigel. H.; Sigel. R.K.O (editors), Metal Ions in Life Science series, Spinger. Germany. 2013; 11. 31-62. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, R. (ed.); Demetriades, A.; Reeder, S. Geochemical Atlas of Europe, Part I - Background Information, Methodology and Maps, FOREGS. 2005. http://www.gtk.fi/publ/foregsatlas.

- Dumitru, M.; Dumitru, S.; Tanase, V.; Mocanu, V.; Manea, A.; Vrânceanu, N.; Preda, M.; Eftene, M.; Ciobanu, C.; Calciu, I.; Rasnoveanu, I. Soil Quality Monitoring in Romania, Sitech. Craiova, Romania. 2011. pp. 51-59.

- Manea, A.; Dumitru, M.; Vrinceanu, N.; Eftene, A.; Anghel, A.; Vrinceanu, A.; Ignat, P.; Dumitru, S.; Mocanu, V. Soil heavy metal status from Maramureș county, Romania. In Proceeding GLOREP 2108 Conference. Timisoara, Romania. 15-17 November 2018.

- Pantelica, A.; Freitas, M. do Carmo; Ene, A.; Steinnes, E. Soil pollution with trace elements at selected sites in Romania studied by instrumental neutron activation analysis, Radiochim. Acta 2013. 101. 45-50. [CrossRef]

- Order of the Minister of Water, Forest and Environmental Protection no. 756/3.11.1997 for the approval of the Regulation regarding the assessment of the environmental pollution, Official Monitor of Romania no. 303bis from 06.11.1997 (in Romanian). Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/13572.

- City of Hope. Available online: https://www.cancercenter.com/risk-factors/fluoride (accessed on 14.04.2024).

- Kumar, K.; Giri, A.; Vivek, P.; Kalaiyarasan, T.; Kumar, B. Effects of Fluoride on Respiration and Photosynthesis in Plants: An Overview, JREST 2017. 2, 1. 043-047. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, N.; Jain, S.; Asawa, K.; Tak, M.; Shinde, K.; Singh, A.; Gandhi, N.; Gupta, V.V. Assessment of Fluoride Concentration of Soil and Vegetables in Vicinity of Zinc Smelter, Debari, Udaipur, Rajasthan, J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015. 9(10): ZC63–ZC66.

- WHO - World Health Organization, Preventing disease through healthy environments. Inadequate or excess fluoride: A major public health concern, WHO/CED/PHE/EPE/19.4.5, (2019). Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329484 (accessed on 14.04.2024).

- Bulgariu, D.; Scarlat, A.A.; Bulgariu, L.; Astefanei, D.; Ciobanu, S.C. Chapter VIII. Considerations for carbonate analysis in soils. In Studies and research in geosciences. Rusu. C.; Bulgariu. D. (editors.), “Al. I. Cuza” University. Iasi, Romania. 2018; Volume 2, 2018 (in Romanian).

- Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. Organic matter and mineral composition of silicate soils: FTIR comparison study by photoacoustic, diffuse reflectance, and attenuated total reflection modalities, MDPI, Agronomy 2021. 11, 9, 1879. 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Stoica, E.; Rauta, C.; Florea, N. (editors), Methods of soil chemical analysis, The Agricultural Technical Propaganda Office, Bucharest, Romania. 1986; pp. 412-418 (in Romanian).

- Madejova, J.; Komadel, P. Baseline Studies of the Clay Minerals Society Source Clays: Infrared Methods, Clays Clay Miner. 2001. 49, 5. pp. 410-432. [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.M.; Pejcic, B.; Esteban, L.; Delle Piane, C.; Raven, M.; Mizaikoff, B. Infrared Attenuated Total Reflectance Spectroscopy: An Innovative Strategy for Analyzing Mineral Components in Energy Relevant Systems, Sci. Rep. 2014. 4, 6764. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Gosav, S.; Ene, A.; Aflori, M. Characterization and discrimination of plant fossils by ATR-FTIR, XRD and chemometric methods, Rom. J. Phys. 2019. 64, 806.

- Craciun, C, The study of some normal and abnormal montmorillonites by thermal analysis and infrared spectroscopy, Thermochim. Acta 1987. 117. 25-36. [CrossRef]

- Palacio, S.; Aitkenhead, M.; Escudero, A.; Montserrat-M, G.; Maestro, M.; Robertson, A.H.J. Gypsophile chemistry unveiled: Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy provides new insight into plant adaptations to gypsum soils, PloS ONE 2014. 9, 9, e107285. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mroczkowska-Szerszeń, M.; Orzechowski, M. Infrared spectroscopy methods in reservoir rocks analysis - semiquantitative approach for carbonate rocks, NFG 2018. ROK LXXIV, 11. 802-8012. [CrossRef]

- Moraru, S.-S.; Ene, A.; Gosav, S. Study of the correlativity between parameters and mineralogy of contaminated agricultural soils, In Proceedings of the 19th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Earth & Planetary Science - SGEM Geoconference. Albena, Bulgaria, Section: Soils, 28th of June-07 of July 2019.

- Sion, A.; Gosav, S.; Ene, A. ATR-FTIR qualitative mineralogical analysis of playground soils from Galati city, SE Romania, Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Mathematics, Physics, Theoretical Mechanics, Fascicle II 2020. 43(2). 141-145. [CrossRef]

- https://ptable.com/#Properties/Series (accessed on 26.05.2024).

- Greger, M., Landberg, T., Vaculik, M. Silicon influences soil availability and accumulation of mineral nutrients in various plant species, Plants 2018. 7, 41. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Tubana, B.S., Babu, T., Datnoff, L.E. A Review of Silicon in Soils and Plants and Its Role in US Agriculture: History and Future Perspectives, Soil Sci. 2016. 181, 9-10. 393-411. [CrossRef]

- Smical, A.I.; Hotea, V.; Oros, V.; Juhasz, J.; Pop, E. Studies on transfer and bioaccumulation of heavy metals from soil into lettuce, EEMJ 2008. 7, 5. 609-6015. [CrossRef]

- Krystofova, O.; Shestivska, V.; Galiova, M.; Novotny, K.; Kaiser, J.; Zehnalek, J.; Babula, P.; Opatrilova, R.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R. Sunflower Plants as Bioindicators of Environmental Pollution with Lead (II) Ions. Sensors 2009. 9, 7. 5040-5058. [CrossRef]

- Gopal, R.; Khurana, N. Effect of heavy metal pollutants on sunflower, Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2011. 5, 9. 531-536.

- Dhiman, S.S.; Zhao. X.; Li, J.; Kim, D.; Kalia, V.C.; Kim, I.-W.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.-K. Metal accumulation by sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and the efficacy of its biomass in enzymatic saccharification, PloS One 2017. 12, 4, e0175845.

- Mani, D.; Sharma, B.; Kumar, C.; Pathak, N. Phytoremediation potential of Helianthus annuus L. in sewage-irrigated Indo-Gangetic alluvial soils, Int. J. Phytoremediation 2012. 14, 3. 235-246. [CrossRef]

- Commision Regulation (EC) no. 1181/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels of certain contaminants in foodstuffs, Official Journal of European Union. L364 20.12.2006 p. 5. Available on https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html.

- FAO/WHO, Codex Alimentarius - General standard for contaminants and toxins in food and feed, CXS 193-1995, (1995). Available on https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius (accessed on 19.05.2024).

- Al-Othman, Z.A.; Ali, R.; Al-Othman, A.M.; Ali, J.; Habila, M.A. Assessment of toxic metals in wheat crops grown on selected soils, irrigated by different water sources, Arab. J. Chem. 2016. 9. S1555-S1562.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2012.006.

- Directive 2002/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 May 2002 on undesirable substances in animal feed - Council statement, Official Journal of European Union, Official Journal of the European Communities, Chapter 3. Volume 42. L140/10 30.5.2002. Available on http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2002/32/oj (accessed on 19.05.2024).

- Yang, Y.; Nan, Z.; Zhao, Z. Bioaccumulation and translocation of cadmium in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and maize (Zea mays L.) from the polluted oasis soil of Northwestern China, Chem Spec Bioavailab 2014. 26, 1. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Alaboudi, K.A.; Ahmed, B.; Brodie, G. Phytoremediation of Pb and Cd contaminated soils by using sunflower (Helianthus annuus) plant, Ann. Agric. Sci. 2018. 63, 1. 123-127. [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, W.A. Assessment of some heavy metals concentration in selected cereals collected from local markets of Ambo City, Ethiopia, J. Cereals Oilseeds 2015. 6, 2, 188B6F851564. 8-13. [CrossRef]

- Shobha, N.; Kalshetty, B.M. Assessment of heavy metals in green vegetables and cereals collected from Jamkhandi local market, Bagalkot, India, Rasayan J. Chem. 2017. 10, 1. 124-135. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, V.; Golia, E.E.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wang, S.-L., Shaeen, S.M. Soil and maize contamination by trace elements and associated health risk assessment in the industrial area of Volos, Greece, Environ. Int. 2019. 124. 79-88. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, C.; Song, X.; Han, Y.; Liang, Z. Assessment of heavy metal pollution in soil and plants from Dunhua sewage irrigation area, Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2011. 6, 11. 5314-5324. [CrossRef]

- Zehra, A.; Sahito, Z.A.; Tong, W.; Tang, L.; Hamid, Y.; Khan, M.B.; Ali, Z.; Naqi, B.; Yang, X. Assessment of sunflower germplasm for phytoremediation of lead-polluted soil and production of seed oil and seed meal for human and animal consumption, J. Environ.l Sci. 2020. 87. 24-38. [CrossRef]

- https://specac.com/infrared-frequency-lookup/#frequencytool (accessed on 19.05.2024).

- Demir, P.; Onde, S.; Severcan, F. Phylogeny f cultivated and wild wheat species using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, Spectrochim. Acta, part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2015. 135. 757-763. [CrossRef]

- Utami, S.N.H.; Suswati, D. Chemical and spectroscopy of peat from West and Central Kalimantan, Indonesia in relation to peat properties, IJOEAR 2016. 2, 8. 2454-1850.

- Gorgulu, S.T.; Dogan, M.; Severcan, F. The characterization and differentiation of higher plants by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, Appl. Spectrosc. 2007. 61, 3. 300-308. [CrossRef]

- Heneen, W.K.; Brismar, K. Scanning electron microscopy of nature grains of rye, wheat and triticale with emphasis on grain shrivelling. Hereditas 1987. 107. 147-162.

- Shorstkii, I.A.; Zherlicin, A.G.; Li, P. Impact of pulse electric field and pulsed microwave treatment on morphological and structural characteristics on sunflower seed, OCL 2019. 26, 47. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, P.M.; de Francisco, A.; de Miranda, M.Z.; Ogliari, P.J.; Torres, G.; Limberger, V.; Montenegro, F.M.; Ruffi, C.R.; Biondi, S. Characterization of Brazilian wheat cultivars for specific technological applications, Food Sci. Technol 2011. 31, 3. 816-826. [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Sampling Location | Longitude | Latitude | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-1a/1b | E of Sivita | 45°36’40.02” | 28°03’53.05” | 4 |

| I-2a/2b | V of Sivita, Tatarca Hill | 45°36’35.00” | 28°02’19.00” | 97 |

| I-3a/3b | NV of Tulucești, right side of Tartacuta Valley | 45°35’08.02” | 28°01’35.95” | 120 |

| I-4a/4b | NV of Tulucesti, left side of Tartacuta Valley | 45°35’11.98” | 28°01’56.00” | 113 |

| I-5a/5b | NV of Ghilanu Sasa Forest | 45°37’29.01” | 28°01’08.01” | 142 |

| I-6a/6b | Ghilanu Hill | 45°37’34.00” | 28°01’42.00” | 106 |

| II-1a/1b | on the right side of Malina Valley | 45°25’05.00” | 27°56’36.00” | 21 |

| II-2a/2b | between Serbestii Noi and Sendreni villages | 45°25’21.33” | 27°53’37.05” | 28 |

| III-1a/1b | V of Pietroiu | 45°19’19.91” | 27°52’11.00” | 7 |

| III-2a/2b | on the left side of Paslaru Valley | 45°23’30.02” | 27°54’56.00” | 5 |

| III-3a/3b | on the left side of Sendreni-Baldovinesti road | 45°23’38.62” | 27°55’17.90” | 5 |

| Metal | Wt [Kowalska, J.B. et al, 2018] |

ERLi [Long, E.R. et al, 1995] |

ERMi [Long, E.R. et al, 1995] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.075 | 34 | 270 |

| Zn | 0.075 | 150 | 410 |

| Cr | 0.134 | 81 | 370 |

| Ni | 0.215 | 20.9 | 51.6 |

| Pb | 0.251 | 46.7 | 218 |

| Cd | 0.250 | 1.2 | 9.6 |

| Parameter | Unit | Residential | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Children | ||||

| BW | body weight | kg | 80 | 15 | USEPA, 2019 |

| ATnc | averaging time for noncarcinogens | days | 365x20 | 365x6 | USEPA, 2019 |

| ATc | averaging time for carcinogens | days | 25550 | 25550 | USEPA, 2019 |

| IngR | ingestion rate of soil | mg kg-1 | 100 | 200 | USEPA, 2019 |

| EF | exposure frequency | days years-1 | 350 | 350 | USEPA, 2019 |

| ED | exposure duration | year | 20 | 6 | USEPA, 2019 |

| CF | conversion factor | kg mg-1 | 10-6 | 10-6 | Sarva, M.P. et al, 2018 |

| SA | skin exposed area | cm2 | 6032 | 2373 | USEPA, 2019 |

| AF | soil-to-skin adherence factor | mg cm-2 | 0.07 | 0.2 | USEPA, 2019 |

| ABS ABSCd ABSom |

absorbtion factor absorbtion factor for Cd absorbtion factor for other metals |

unitless |

0.01 0.001 |

0.01 0.001 |

USEPA, 2015 |

| InhR | inhalation rate | m3 day-1 | 20 | 10 | USEPA, 2019 |

| ET | exposure time | hours day-1 | 24 | 24 | USEPA, 2019 |

| PEF | particle emission factor | m3 kg-1 | 1.36x109 | 1.36x109 | USEPA, 2019 |

| Sampling Site |

Layer (cm) |

pH | CaCO3 | OM | OC | SEB | HA | DBS (%) |

EC (µS cm-1) |

TDS (mg 100 g soil-1) |

Texture | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me 100 g Soil -1 | Clay | Silt | Sand | |||||||||||

| (%) | (%) | |||||||||||||

| T-1a | 0-5 | 8.35 | 6.61 | 3.98 | 2.31 | 91.85 | 0.59 | 99.36 | 331.00 | 112.50 | 5.57 | 32.23 | 62.20 | |

| T-1b | 5-30 | 8.48 | 7.42 | 3.04 | 1.76 | 94.56 | 0.38 | 99.60 | 312.00 | 106.10 | 5.62 | 30.78 | 63.60 | |

| T-2a | 0-5 | 8.16 | 2.75 | 3.39 | 1.97 | 68.18 | 0.67 | 99.03 | 171.50 | 58.30 | 2.87 | 35.48 | 61.65 | |

| T-2b | 5-30 | 8.06 | 3.03 | 3.37 | 1.95 | 67.80 | 0.75 | 98.91 | 184.60 | 52.80 | 2.48 | 30.11 | 67.41 | |

| T-3a | 0-5 | 7.44 | 0.00 | 2.22 | 1.29 | 27.06 | 1.22 | 95.69 | 92.40 | 31.40 | 1.30 | 23.70 | 75.00 | |

| T-3b | 5-30 | 7.59 | 0.00 | 1.99 | 1.15 | 24.34 | 1.09 | 95.71 | 90.60 | 30.80 | 1.40 | 30.60 | 68.00 | |

| T-4a | 0-5 | 8.32 | 10.70 | 1.60 | 0.93 | 94.18 | 0.59 | 99.38 | 182.40 | 62.00 | 1.57 | 30.91 | 67.52 | |

| T-4b | 5-30 | 8.40 | 11.42 | 1.82 | 1.06 | 96.12 | 0.54 | 99.44 | 169.20 | 57.50 | 2.15 | 30.14 | 67.71 | |

| T-5a | 0-5 | 6.63 | 0.00 | 2.42 | 1.40 | 26.28 | 2.01 | 92.90 | 162.50 | 55.30 | 7.70 | 32.70 | 59.60 | |

| T-5b | 5-30 | 6.56 | 0.00 | 2.50 | 1.45 | 25.50 | 2.22 | 91.99 | 151.80 | 51.60 | 1.20 | 23.00 | 75.80 | |

| T-6a | 0-5 | 8.32 | 5.27 | 2.04 | 1.18 | 94.96 | 0.59 | 99.38 | 156.30 | 53.10 | 0.84 | 26.29 | 72.87 | |

| T-6b | 5-30 | 8.31 | 4.95 | 1.70 | 0.99 | 96.12 | 0.59 | 99.39 | 168.80 | 57.40 | 1.27 | 23.67 | 75.06 | |

| S-1a | 0-5 | 8.40 | 8.85 | 2.14 | 1.24 | 92.24 | 0.54 | 99.42 | 200.00 | 68.00 | 1.31 | 27.54 | 71.15 | |

| S-1b | 5-30 | 8.47 | 8.55 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 94.18 | 0.38 | 99.60 | 178.60 | 60.70 | 0.99 | 19.90 | 79.11 | |

| S-2a | 0-5 | 8.39 | 8.48 | 1.68 | 0.97 | 94.18 | 0.54 | 99.43 | 266.00 | 90.40 | 2.40 | 33.11 | 64.49 | |

| S-2b | 5-30 | 8.59 | 9.85 | 1.59 | 0.92 | 93.79 | 0.29 | 99.69 | 229.00 | 77.90 | 1.00 | 35.27 | 63.73 | |

| V-1a | 0-5 | 8.13 | 2.52 | 2.61 | 1.51 | 62.75 | 0.71 | 98.88 | 206.00 | 70.00 | 7.28 | 3.90 | 88.82 | |

| V-1b | 5-30 | 8.15 | 2.59 | 1.93 | 1.12 | 59.65 | 0.67 | 98.89 | 159.40 | 54.20 | 1.43 | 10.27 | 88.30 | |

| V-2a | 0-5 | 8.30 | 5.92 | 2.08 | 1.21 | 96.51 | 0.63 | 99.35 | 179.10 | 60.90 | 3.08 | 35.82 | 61.10 | |

| V-2b | 5-30 | 8.38 | 6.12 | 2.25 | 1.31 | 95.34 | 0.54 | 99.44 | 170.10 | 57.80 | 4.69 | 36.32 | 58.99 | |

| V-3a | 0-5 | 8.44 | 4.84 | 1.61 | 0.93 | 96.12 | 0.46 | 99.52 | 150.00 | 51.00 | 3.89 | 28.37 | 67.74 | |

| V-3b | 5-30 | 8.47 | 4.82 | 1.73 | 1.00 | 93.40 | 0.38 | 99.59 | 141.90 | 48.20 | 1.57 | 26.69 | 71.74 | |

| References | Cd | Co | Cr | Cu | Mn | Ni | Pb | Zn | F | Cl | Ti | Si | Na | Mg | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg kg-1) | (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Continental crust [Kabata-Pendias, A., 2011], |

0.08*- 0.10 |

10 | 100 | 55 | 900 | 20 | 15 | 70 | 625 | 640 | 4400 | - | - | - | 5 |

| World soils [Kabata-Pendias, A., 2011], |

0.06*- 0.41 |

11.3 | 59.5 | 38.9 | 488 | 29 | 27 | 70 | 321 | 300 | 7038 | - | - | - | 3.5 |

| European soils1 [Salminen, R. et al, 2005] |

0.284 | 8.91 | 32.6 | 16.4 | 524 | 30.7 | 23.9 | 60.9 | - | - | 6090 | 65.4 | 1.15 | 1.18 | 2.17 |

| Romania soils [Dumitru, M. et al, 2011] |

0.43 | 13.0 | - | 26.7 | 175- 1820 |

35.0 | 21.3 | 87 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Romania (Maramures county) [Manea, A. et al, 2018] |

0.75 | 11 | 23 | 20 | 554 | 22 | 57 | 78 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Romania (Galati) [Pantelica, A. et al., 2013] |

<2.5 | 13.1 | 84 | - | 538 | 67 | - | 106 | - | - | 2900 | - | 0.83 | 0.76 | 3.15 |

| Reference values (land with sensitive use of soils) [Order no. 756/1997] Normal Alert threshold Intervention threshold |

1 3 5 |

15 30 50 |

30 100 300 |

20 100 200 |

900 1500 2500 |

20 75 150 |

20 50 100 |

100 300 600 |

- 150 300 |

- | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mineral Type | Absorption Band (cm-1) |

Band Assignment1 |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clay minerals | |||

| Montmorillonite | 830 | β(Al-OH-Mg) | 840-830 cm-1 β(Al-OH-Mg) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] |

| 912 | β(Al-Al-OH) | 930-910 cm-1 β(OH) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 915 cm-1 β(OH) [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] 916 cm-1 β(OH) [Madejova, J. și Komadel, P., 2001] |

|

| 1633 | β(OH) | 1635 cm-1 β(OH) [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014] | |

| 3390 | ν(OH) | 3392 cm-1 [Gosav, S. et al, 2019] | |

| 3620 |

inner surface ν(OH) |

3700-3600 cm-1 inner surface ν(OH) [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014] 3610-3621 cm-1 abnormal montmorillonite [Crăciun, C., 1987] 3620 cm-1 ν(OH) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 3627 cm-1 [Gosav, S. et al, 2019] |

|

| Kaolinite | 419 | β(Si-O-Si) | 430-420 cm-1 β(Si-O) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] |

| 912 | β(Al-OH-Al) | 930-910 cm-1 (β(OH) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 915 cm-1 (β(OH) [Stoica, E. et al, 1986], [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014], [Madejova, J. and Komadel, P., 2001] |

|

| 1032 | νas(Si-O-Si) | 1034 cm-1 [Gosav, S. et al, 2019] 1037 cm-1 νas(Al-O) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 1038 cm-1 νas(Si-O-Si) [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] |

|

| 3620 | inner ν(OH) | 3620 cm-1 ν(OH) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021], [Stoica, E. et al, 1986], [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014], [Madejova, J. and Komadel, P., 2001] | |

| 3695 |

inner-surface ν(OH) |

3690-3680 cm-1 ν(Si-OH) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 3694 cm-1 inner-surface ν(OH) [Madejova, J. and Komadel, P., 2001] 3695 cm-1 (ν(OH)) [Stoica, E. et al, 1986], [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014] |

|

| Non-clay minerals | |||

| Quartz | 457 | β(Si-O-Si) | 450 cm-1 β(O-Si-O) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 452 cm-1 [Gosav, S. et al, 2019] |

| 517 | β(O-Si-O) | 517-513 cm-1 β(O-Si-O) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 512 cm-1 SiO2 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] |

|

| 692 | β(Si-O-Si) | 697-696 cm-1 β(Si-O-Si) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 693 cm-1 SiO2 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] |

|

| 778 | ν(Si-O) | 774 cm-1 α-SiO2, Si-O-Si [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 778 cm-1 SiO2 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] 779 cm-1 ν(Si-O) [Madejova, J. and Komadel, P., 2001] |

|

| 796 | νsim(Si-O-Si) | 796 cm-1 νsim(Si-O-Si) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 797 cm-1 ν(Si-O) [Madejova, J. and Komadel, P., 2001] 798 cm-1 SiO2 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] |

|

| 1001 | ν(Si-O) | 1010-995 cm-1 ν(Si-O) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 1100-950 cm-1 ν(Si-O) [Palacio, S. et al, 2014] |

|

| 1111 | νas(Si-O-Si) | 1115-1105 cm-1 amorphous silica [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] | |

| 1168 | νas(Si-O-Si) | 1165-1153 cm-1 specific SiO2 structure [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 1166 cm-1 SiO2 - cristobalite [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] |

|

| Orthoclase and albite | 646 | β(O-Si(Al)-O) | 645-640 cm-1 β(Si-O) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] |

| 989 | ν(Si-O) | 1200-900 cm-1 [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014] | |

| Calcite | 712 | β(C-O) | 713-710 cm-1 CaCO3 [Bulgariu, D. et al, 2018] 712 cm-1 CaCO3 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] 715 cm-1 β(C-O) in plane [Palacio, S. et al, 2014] |

| 874 | β(C-O) | 881-873 cm-1 CaCO3 [Bulgariu, D. et al, 2018] 874 cm-1 β(C-O) in plane [Palacio, S. et al, 2014] 875 cm-1 CaCO3 [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021], [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014] 877 cm-1 CaCO3 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] |

|

| 1433 | νas(C-O) | 1400 cm-1 νas(C-O) [Müller, C.M. et al, 2014] 1410-1435 cm-1 CaCO3 [Bulgariu, D. et al, 2018] 1435 cm-1 CaCO3 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] 1450-1410 cm-1 νas(C-O) [Palacio, S. et al, 2014] |

|

| Dolomite | 1433 | νas(C-O) | 1450-1430 cm-1 CaMg(CO3)2 [Bulgariu, D. et al, 2018] 1432 cm-1 CaMg(CO3)2 [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] 1433 cm-1 νas(CO32-) [Mroczkowska-Szerszeń, M. and Orzechowski, M., 2018] |

| Gypsum | 646 | β(S-O) | 645-640 cm-1 β(S-O) [Volkov, D.S. et al, 2021] 680-610 cm-1 β(S-O) [Palacio, S. et al, 2014] |

| 1111 | ν(S-O) | 1140-1080 cm-1 ν(S-O) [Palacio, S. et al, 2014] 1111 cm-1 CaSO4 ∙ 2 H2O [Stoica, E. et al, 1986] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Product | Element (mg kg-1) | References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Co | Cr | Cu | Ni | Pb | Zn | ||

| Wheat and corn grains | 0.10 | - | - | - | - | 0.20 | - | [Regulation (EC) no. 1881/2006]- [https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html][FAO/WHO, 1995] |

| Sunflower seeds | 0.50 | - | - | - | - | 0.10 | - | |

| Crops | 0.20 | - | 2.30 | 73.30 | 67.90 | 0.30 | 99.40 | [Al-Othman, Z.A. et al, 2016] |

| Plant sample |

Plant species | Element (mg kg-1 ± σ) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | Cl | Fe | ||

| T-1-l1 | wheat | 17 ± 6 | 830 ± 20 | 9870 ± 867 | 748 ± 48 | 61300 ± 5500 | 3870 ± 220 | n.d. | 3940 ± 1110 |

| T-1-c | <18 | 120 ± 20 | 4441 ± 1314 | <140 | <16900 | 4750 ± 490 | n.d. | <4420 | |

| T-2-l | wheat | 270 ± 3 | 1440 ± 26 | 8019 ± 632 | 2850 ± 90 | 155000 ± 9800 | 2070 ± 190 | <1300 | 4990 ± 930 |

| T-2-c | <16 | 290 ± 30 | 4251 ± 1675 | <140 | <15800 | 2290 ± 290 | n.d. | <4280 | |

| T-3-l | corn | 23 ± 4 | 1156 ± 30 | 8249 ± 806 | 2543 ± 100 | 110190 ± 7284 | 2234 ± 174 | <1205 | 5463 ± 1012 |

| T-3-c | <10 | 26 ± 10 | <2222 | <78 | <9022 | 2287 ± 293 | n.d. | 3871 ± 1382 | |

| T-4-l | corn | 30 ± 5 | 616 ± 28 | 21802 ± 1859 | 2530 ± 98 | 122881 ± 7820 | 6436 ± 300 | <1215 | 6302 ± 1289 |

| T-4-c | 10 ± 4 | 21 ± 8 | 4481 ± 2008 | 460 ± 74 | <8634 | 3438 ± 264 | n.d. | <2418 | |

| T-5-l | sun flower | 9 ± 3 | 241 ± 16 | 66761 ± 3379 | 1159 ± 73 | 22276 ± 3640 | 6862 ± 306 | <1380 | 5472 ± 1094 |

| T-6-l | sun flower | 15 ± 3 | 228 ± 13 | 30532 ± 2015 | 855 ± 62 | 35195 ± 4448 | 4629 ± 263 | 3071 ± 703 | 4879 ± 1003 |

| S-1-l | wheat | 18 ± 3 | 741 ± 30 | 5043 ± 642 | 1693 ± 76 | 77847 ± 7695 | 695 ± 131 | n.d. | <2109 |

| S-1-c | <10 | 20 ± 6 | 1812 ± 198 | 120 ± 31 | <10031 | 1041 ± 139 | n.d. | <2381 | |

| S-2-l | sun flower | <12 | 71 ± 13 | 19701 ± 2699 | 245 ± 83 | 19500 ± 5967 | 2486 ± 356 | 18915 ± 1495 | 6347 ± 2317 |

| V-1-l | wheat | <13 | 1342 ± 42 | 4029 ± 1078 | 1122 ± 102 | 80858 ± 15848 | 1517 ± 320 | 4029 ± 1078 | 3521 ± 1556 |

| V-1-c | 10 ± 4 | 47 ± 14 | <1977 | <90 | <11532 | 1623 ± 261 | <1977 | <3107 | |

| V-2-l | sun flower | 13 ± 4 | 124 ± 19 | 17414 ± 2155 | 286 ± 60 | 12678 ± 3410 | 2431 ± 294 | 19254 ± 1240 | 10133 ± 1900 |

| V-3-l | sun flower | 19 ± 6 | 192 ± 25 | 24557 ± 2701 | 383 ± 84 | <17525 | 1686 ± 403 | 29102 ± 1647 | 7952 ± 1606 |

| Absorption Band (cm-1) | Band Assignment1 | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat Leaves | Sunflower Leaves | ||

| 3293 | 3273 | ν (≡C-H): alchineν(-(C)O-H): alcohols, phenolsν (-(C)-N-H): Amine I | 3270-3330 cm-1 ν (≡C-H) [*]3200-3550 cm-1 ν(-(C)O-H) [*]3200-3500 cm-1 ν (-(C)-N-H) [*] |

| 2918, 2850 | 2918, 2850 | νas/sym(CH2): lipids, together with proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acidsν(-(C)O-H): carboxylic acidsν(-(C-H): alkane | 2959-2852 cm-1 νas(CH2) [Demir, P. et al, 2015], 2920 cm-1 νsym(CH2) [Utami, S.N.H. and Suswati, D., 2016]2852 cm-1 νsym(CH2) [Gorgulu, S.T. et al, 2007]2500-3300 cm-1 ν(-(C)O-H) [*]2800-3000 cm -1 ν(-(C-H) [*] |

| 1729 | 1731 | ν(-C=O): carboxylic acidsν(C=O) of esters: phospholipids, cholesterol esters, hemicellulose, and pectin | 1680-1760 cm-1 ν(-C=O) [*],[Utami, S.N.H. and Suswati, D., 2016]1733 cm-1 ν(C=O) [Gorgulu, S.T. et al, 2007] |

| 1637 | 1597 | νas(C=O): proteins, ligninsν(-C=C-): phenolsβ (-(C)-N-H): Amine I | 1650-1600 cm-1 νas(C=O) [Utami, S.N.H. and Suswati, D., 2016], 1550-1700 cm-1 ν(-C=C-) [*]1500-1650 cm-1 β (-(C)-N-H) [*] |

| 1419 | 1403 | β(OH): polysaccharides, alcohols, carboxylic acidsβ(-C-H): alkane | 1414 cm-1 β(OH) [Demir, P. et al, 2015]1395-1440 cm-1 β(-(C)O-H) [*]1400-1470 cm-1 β(-C-H) [*]1415 cm-1 β(OH) [Gorgulu, S.T. ș.a., 2007] |

| 1374 | - | β(CH2): hemicellulose, xyloglucans, phenols and aliphatic structuresβ(-(H)2C-H): alkane | 1350-1380 cm-1 β(-(H2C-H) [*]1371 cm-1 β(C-H) [Utami, S.N.H. and Suswati, D., 2016] |

| 1317 | 1322 | β(CH2): celluloseν(-C-OH): carboxylic acidsν(C-OH): phenols | 1369, 1335, 1315, 1280 cm-1 β(CH2) [Demir, P. et al, 2015]1210-1320 cm-1 ν(-C-OH) [*]1310-1390 cm-1 ν(C-OH) [*] |

| - | 1240 | Amine III ν(C-N); ν(N-H): proteinsν(-C-OH): carbohylic acidν(-C-F): akyl fluorideν(-S=O): sulfoxide | 1239 cm-1 ν(C-N); ν(N-H) [Demir, P. et al, 2015]1235 cm-1 ν(C-N); ν(N-H) [Gorgulu, S.T. ș.a., 2007]1210-1320 cm-1 ν(-C-OH) [*]1000-1400 cm-1 ν(-C-F) [*]1030-1372 cm-1 ν(-S=O) [*] |

| 1033 | 1025 | ν(C-O); β(OH): polysaccharides, , xyloglucansν(-C-N-): Amine I, II, IIIν(-C=S): thioketone | 1035 cm-1 ν(-C-N-) [Gorgulu, S.T. ș.a., 2007]1020-1200 cm-1 ν(-C-N-) [*][Demir, P. et al, 2015]1000-1250 cm-1 ν(-C=S) [*] |

| 784 | - | β(-(C)-N-H): Amine I, IIβ(C-H): phenols | 660-900 cm-1 β(-(C)-N-H) [*]680-860 cm-1 β(C-H) [*] |

| - | 535 | ν(-C-I), ν(-C-Br): alkyl iodide and alkyl bromide | 500-600 cm-1 ν(-C-I) [*]515-690 cm-1 ν(-C-Br) [*] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).