Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

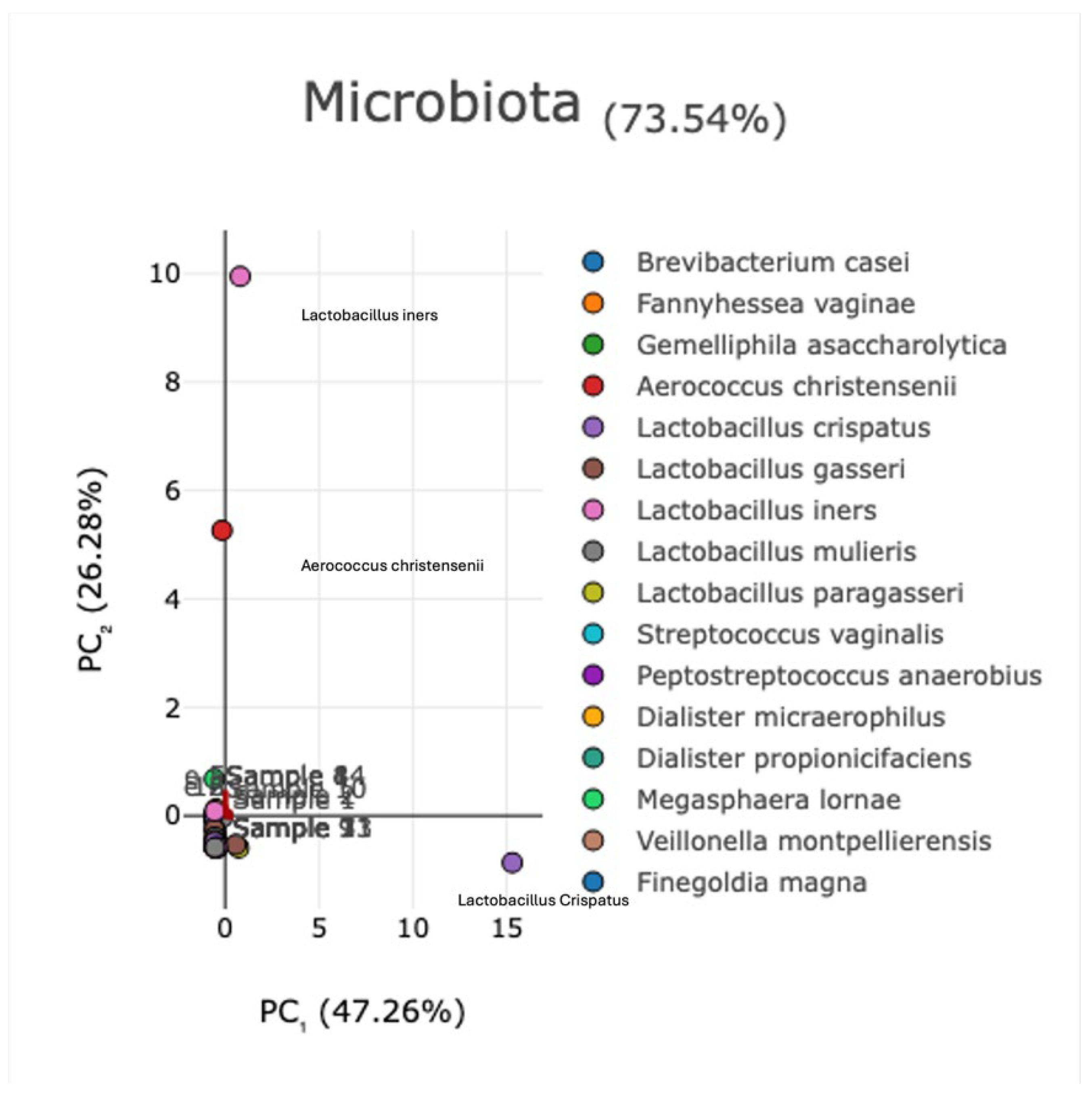

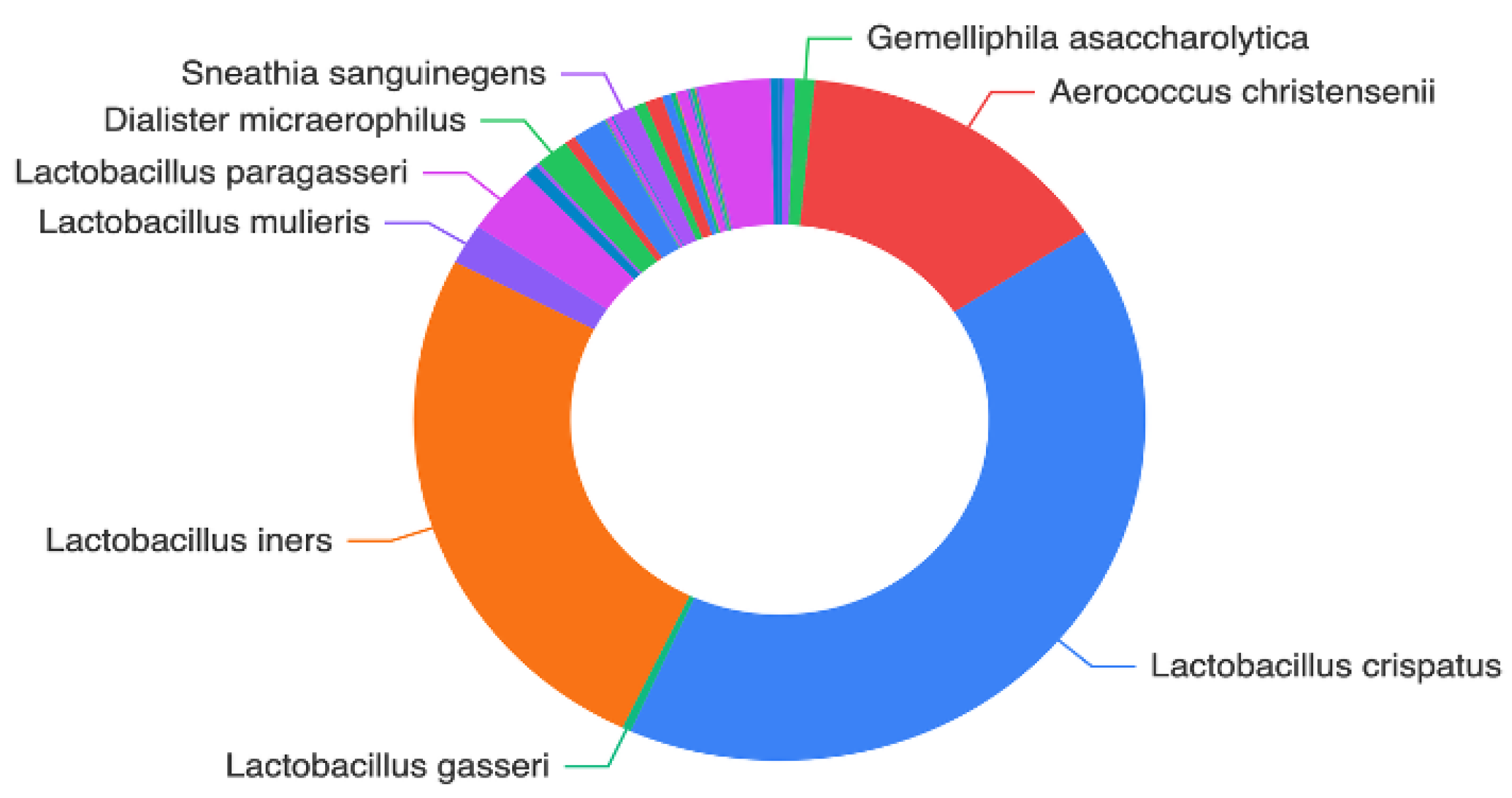

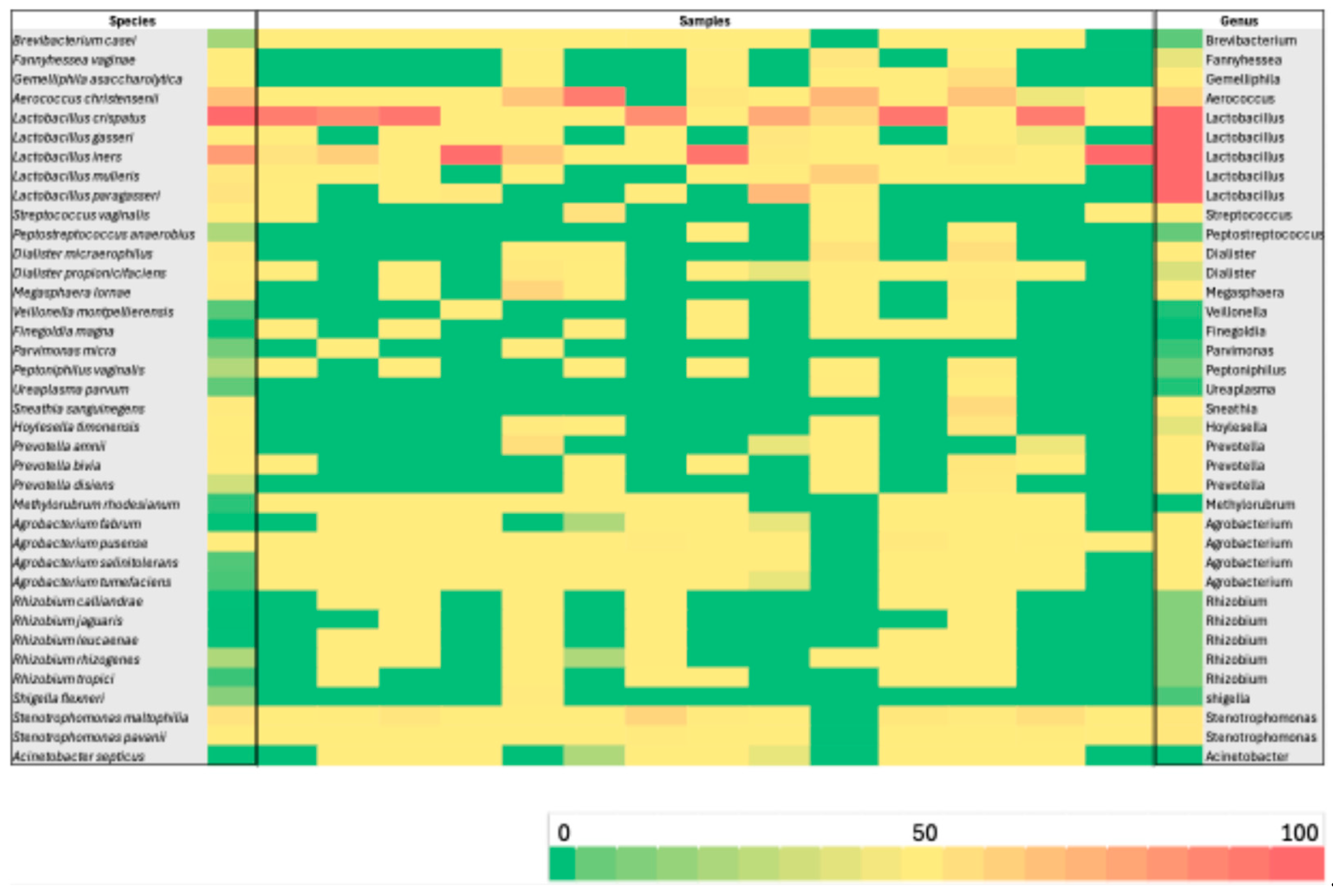

Background/Objectives: The vaginal microbiota (VM) represents a highly diverse microbial ecosystem shaped by the distinctive mucosal environment and immunological characteristics of the female genital tract. Recent evidence emphasizes that alterations in cervical microbial composition may contribute to high-risk gynecological conditions. In this context, the present study sought to comprehensively characterize the cervical microbiota of a well-defined cohort of Greek women. The primary aim was to evaluate the functional microbial landscape, with a focus on identifying bacterial signatures and potential microbial pathways that may influence cervical physiology, protection, and disease susceptibility. Methods: Microbial genomic DNA of 60 samples was extracted using the Magcore Bacterial automated Kit and was subjected to 16S rRNA sequencing using the Nanopore MinION™ enabling a comprehensive analysis of the microbial community. Results: More than 75% of the total microbial community of the cervical samples were represented by the species: Lactobacillus iners and Lactobacillus crispatu and Aerococcus christensenii while the species Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, S. pavanii, Acinetobacter septicus, Rhizobium rhizogenes, R. tropici, R. jaguaris, Prevotella amnii, P. disiens, Brevibacterium casei, Fannyhessea vaginae, Gemelliphila asaccharolytica, flexneri were detected in lower abundances. Conclusions: These findings highlight the predominant protective role of Lactobacillus species while emphasizing the potential contributions of low-abundance or environmentally derived bacteria whose functional implications require further investigation. Broader population studies are essential to establish microbial signatures as diagnostic markers or therapeutic targets for optimizing cervical health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cervical Samples

2.2. DNA Amplification, Barcoding and Library Preparation and 16S rRNA Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristic of Samples

3.2. Evaluation of Microbial Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pu, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Li, C. Microbial and Metabolic Profiles Associated with HPV Infection and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Multi-Omics Study. Microbiol Spectr 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curty, G.; de Carvalho, P.S.; Soares, M.A. The Role of the Cervicovaginal Microbiome on the Genesis and as a Biomarker of Premalignant Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Invasive Cervical Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 21, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, W.; Yan, R.; Chi, J.; Xia, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, P. Co-Evolution of Vaginal Microbiome and Cervical Cancer. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Sun, H.; Chu, J.; Gong, X.; Liu, X. Cervicovaginal Microbiota: A Promising Direction for Prevention and Treatment in Cervical Cancer. Infect Agent Cancer 2024, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Tang, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhao, C. Associations of Atopobium, Garderella, Megasphaera, Prevotella, Sneathia, and Streptococcus with Human Papillomavirus Infection, Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2025, 25, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazinani, S.; Aghazadeh, M.; Poortahmasebi, V.; Arafi, V.; Hasani, A. Cervical Cancer Pathology and Vaginal and Gut Microbiota: Conception of the Association. Lett Appl Microbiol 2025, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancilla, V.; Jimenez, N.R.; Bishop, N.S.; Flores, M.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. The Vaginal Microbiota, Human Papillomavirus Infection, and Cervical Carcinogenesis: A Systematic Review in the Latina Population. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2024, 14, 480–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; Wang, S.; Min, Y.; Liu, X.; Fang, J.; Lang, J.; Chen, M. Associations of the Gut, Cervical, and Vaginal Microbiota with Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Womens Health 2025, 25, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhao, S.; Shan, J.; Ren, Q. Metabolomic and Microbiota Profiles in Cervicovaginal Lavage Fluid of Women with High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, K.D.; Tatusova, T.; Maglott, D.R. NCBI Reference Sequences (RefSeq): A Curated Non-Redundant Sequence Database of Genomes, Transcripts and Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, D61–D65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. SRplot: A Free Online Platform for Data Visualization and Graphing. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravel, J.; Brotman, R.M. Translating the Vaginal Microbiome: Gaps and Challenges. Genome Med 2016, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- France, M.T.; Ma, B.; Gajer, P.; Brown, S.; Humphrys, M.S.; Holm, J.B.; Waetjen, L.E.; Brotman, R.M.; Ravel, J. VALENCIA: A Nearest Centroid Classification Method for Vaginal Microbial Communities Based on Composition. Microbiome 2020, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, M.I.; Reid, G.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Lebeer, S. Lactobacillus Iners : Friend or Foe? Trends Microbiol 2017, 25, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Campos, E.; García-Villaraco, A.; Montero-Palmero, Ma.B.; Gutiérrez-Mañero, F.J.; Ramos-Solano, B. Bacillus G7 Improves Adaptation to Salt Stress in Olea Europaea L. Plantlets, Enhancing Water Use Efficiency and Preventing Oxidative Stress. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 22507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, P.; Bai, X.; Tian, S.; Yang, M.; Leng, D.; Kui, H.; Zhang, S.; Yan, X.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Vaginal Microbiota Are Associated with in Vitro Fertilization during Female Infertility. iMeta 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Guo, R.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Ling, Z. Contribution of Lactobacillus Iners to Vaginal Health and Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen-Gunther, J.; Xia, Q.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y. Cervicovaginal Microbiome and HPV: A Standardized Approach to 16S/ITS NGS and Microbial Community Profiling for Viral Association. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Peng, Y.; Jiang, N.; Shi, Y.; Ying, C. High-Throughput Sequencing-Based Analysis of Changes in the Vaginal Microbiome during the Disease Course of Patients with Bacterial Vaginosis: A Case–Control Study. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollin, A.; Katta, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Akins, R.A. Association of Key Species of Vaginal Bacteria of Recurrent Bacterial Vaginosis Patients before and after Oral Metronidazole Therapy with Short- and Long-Term Clinical Outcomes. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0272012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanna Norenhag Vaginal Microbiota Composition and Function. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 2070 2024.

- Lin, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Ke, J.; Lin, C.; Yao, B.; Zhang, C.; Tan, N. Aerococcus Christensenii: An Emerging Pathogen Associated with Infections and Bacteremia in Pregnancy—Genomic Insights and Pathogenicity Evaluation. Funct Integr Genomics 2025, 25, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, Y.; Viswanathan, P. High-Quality Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis of Lactobacillus Paragasseri UBLG-36 Reveals Oxalate-Degrading Potential of the Strain. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0260116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ene, A.; Stegman, N.; Wolfe, A.; Putonti, C. Genomic Insights into Lactobacillus Gasseri and Lactobacillus Paragasseri. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Hu, X.; Ying, C. Advances in Research on the Relationship between Vaginal Microbiota and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes and Gynecological Diseases. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putonti, C.; Shapiro, J.W.; Ene, A.; Tsibere, O.; Wolfe, A.J. Comparative Genomic Study of Lactobacillus Jensenii and the Newly Defined Lactobacillus Mulieris Species Identifies Species-Specific Functionality. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajer, P.; Brotman, R.M.; Bai, G.; Sakamoto, J.; Schütte, U.M.E.; Zhong, X.; Koenig, S.S.K.; Fu, L.; Ma, Z. (Sam); Zhou, X.; et al. Temporal Dynamics of the Human Vaginal Microbiota. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, I.M.C.; Cordeiro, A.L.; Teixeira, G.S.; Domingues, V.S.; Nardi, R.M.D.; Monteiro, A.S.; Alves, R.J.; Siqueira, E.P.; Santos, V.L. Biological and Physicochemical Properties of Biosurfactants Produced by Lactobacillus Jensenii P6A and Lactobacillus Gasseri P65. Microb Cell Fact 2017, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, B.; Lin, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zuo, X. Dysbiosis of Cervical and Vaginal Microbiota Associated With Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marselinus Edwin Widyanto Daniwijaya, A.A.C.P.S.D.A.S.T.N. Identification of Streptococcus Intermedius and Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia in Recurrent Leucorrhoea: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (JCMID) 2021, 1, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Su, M.; Diao, X.; Liang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhan, Y. Characteristics of Vaginal Microbiota in Various Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.M.; Srinivasan, S.; Purvine, S.O.; Fiedler, T.L.; Leiser, O.P.; Proll, S.C.; Minot, S.S.; Djukovic, D.; Raftery, D.; Johnston, C.; et al. Syntrophic Bacterial and Host–Microbe Interactions in Bacterial Vaginosis. ISME J 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, L.; Han, X.; Gao, S.; Zhang, C. Vaginal Microbiome Dysbiosis Is Associated with the Different Cervical Disease Status. Journal of Microbiology 2023, 61, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, L.G. V.; Novak, J.; França, A.; Muzny, C.A.; Cerca, N. Gardnerella Vaginalis, Fannyhessea Vaginae, and Prevotella Bivia Strongly Influence Each Other’s Transcriptome in Triple-Species Biofilms. Microb Ecol 2024, 87, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Dai, W.; Wu, D.; Xu, R.; Li, C.; Wu, R.; Du, H. Inferred Bi-Directional Interactions between Vaginal Microbiota, Metabolome and Persistent HPV Infection Accompanied by High-Grade Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. BMC Microbiol 2025, 25, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.; Altamirano-Colina, A.; López-Cortés, A. The Vaginal Microbiome in HPV Persistence and Cervical Cancer Progression. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii, T.; Tamai, K.; Mitsui, M.; Notake, S.; Yanagisawa, H. Blood Stream Infections Caused by Acinetobacter Ursingii in an Obstetrics Ward. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2011, 11, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska-Czerwińska, A.; Morawiec, E.; Zmarzły, N.; Szapski, M.; Jendrysek, J.; Pecyna, A.; Zapletał-Pudełko, K.; Małysiak, W.; Sirek, T.; Ossowski, P.; et al. Dynamics of Microbiome Changes in the Endometrium and Uterine Cervix during Embryo Implantation: A Comparative Analysis. Medical Science Monitor 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, M.; Amabebe, E.; Kulkarni, N.S.; Papageorgiou, M.D.; Walker, H.; Wyles, M.D.; Anumba, D.O. Vaginal Host Immune-Microbiome-Metabolite Interactions Associated with Spontaneous Preterm Birth in a Predominantly White Cohort. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.G. da; Ferreira, E.P. de B.; Damin, V.; Nascente, A.S. Response of the Common Bean to Liquid Fertilizer and Rhizobium Tropici Inoculation. Semin Cienc Agrar 2020, 41, 2967–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Rosales, R.; Villalobos-Escobedo, J.M.; Rogel, M.A.; Martinez, J.; Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Martínez-Romero, E. Rhizobium Calliandrae Sp. Nov., Rhizobium Mayense Sp. Nov. and Rhizobium Jaguaris Sp. Nov., Rhizobial Species Nodulating the Medicinal Legume Calliandra Grandiflora. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2013, 63, 3423–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.A.; Balkus, J.E.; Anzala, O.; Kimani, J.; Hoffman, N.G.; Fiedler, T.L.; Mochache, V.; Fredricks, D.N.; McClelland, R.S.; Srinivasan, S. Associations Between Vaginal Bacteria and Bacterial Vaginosis Signs and Symptoms: A Comparative Study of Kenyan and American Women. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.D.; Van Gerwen, O.T.; Dong, C.; Sousa, L.G. V.; Cerca, N.; Elnaggar, J.H.; Taylor, C.M.; Muzny, C.A. The Role of Prevotella Species in Female Genital Tract Infections. Pathogens 2024, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).