Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Characteristic of Ammonia Combustion Instability

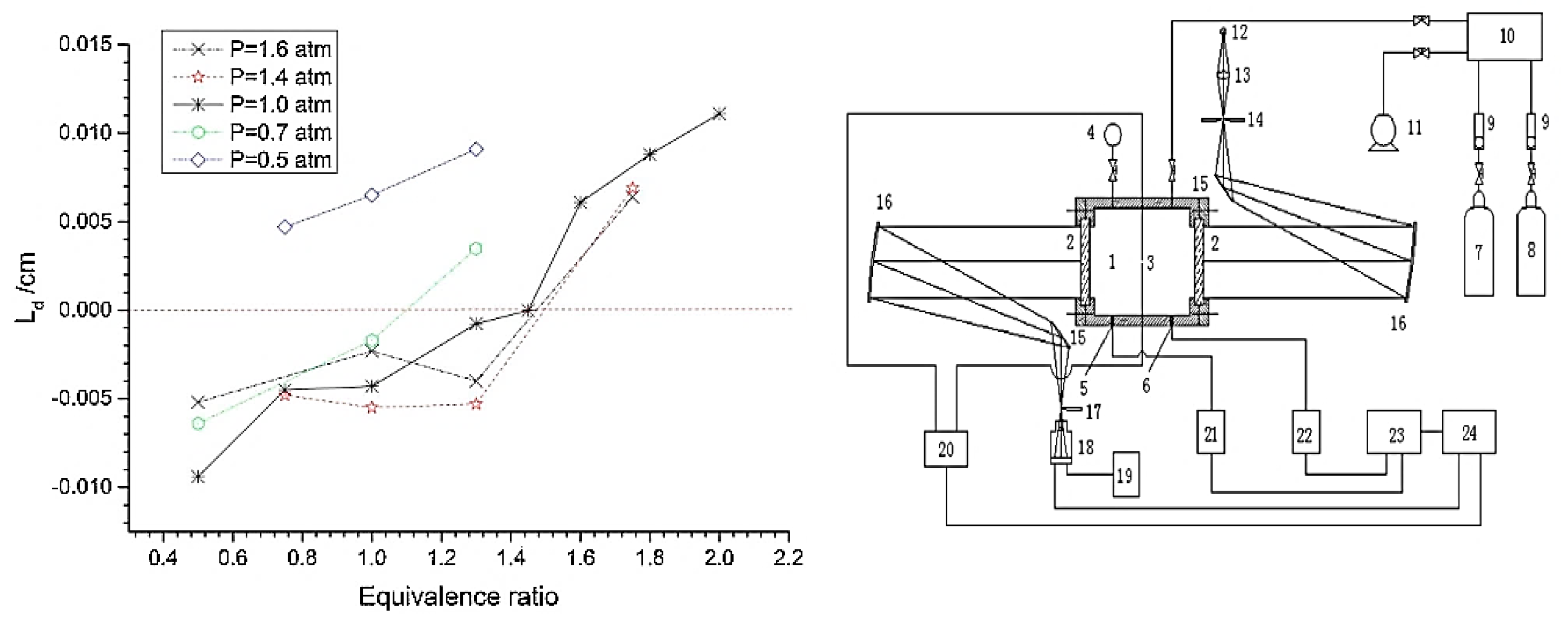

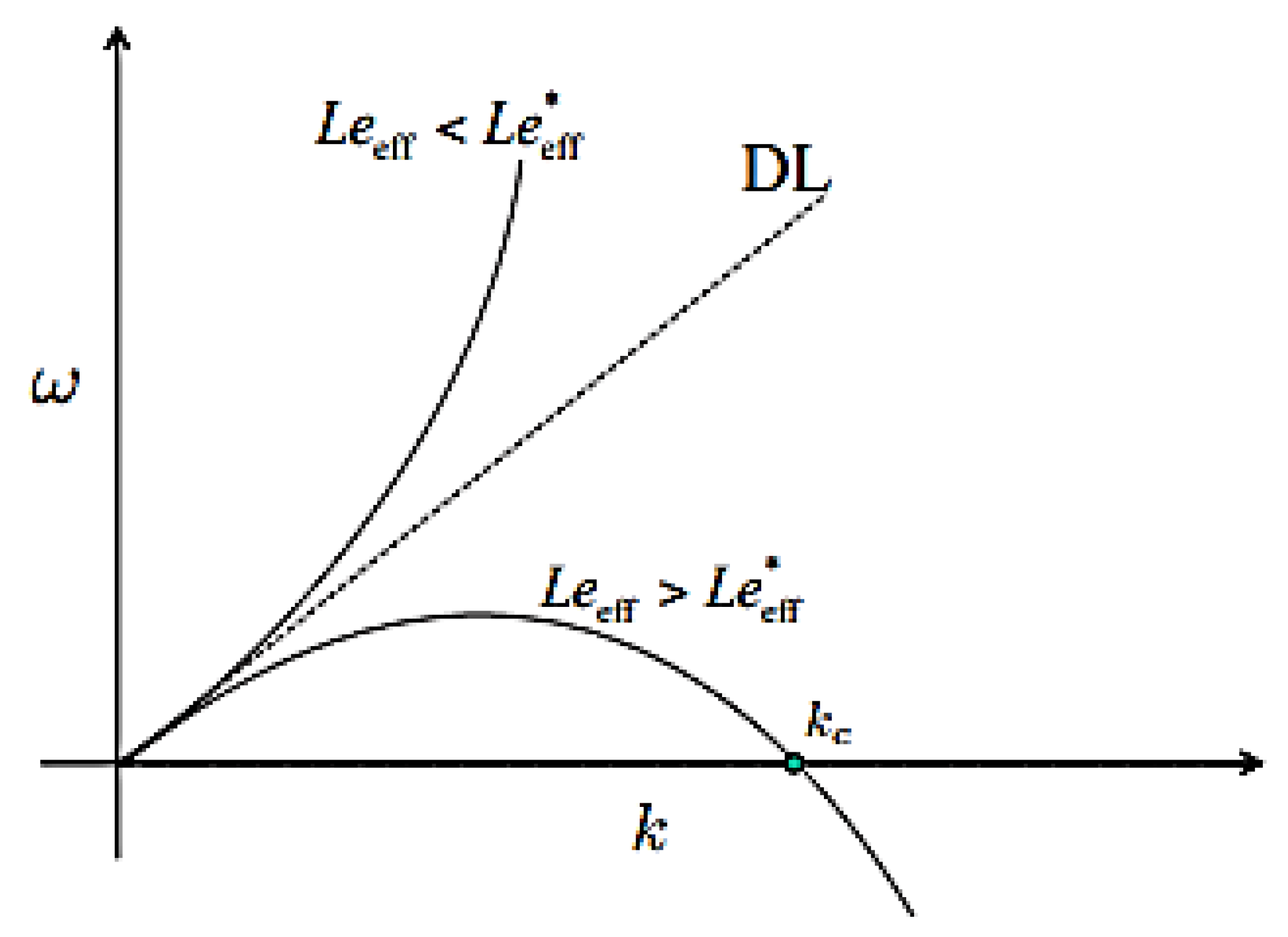

1.2. Thermal Diffusive Instability of Ammonia Combustion

1.3. Hydrodynamic Instability Characteristics of Ammonia Combustion

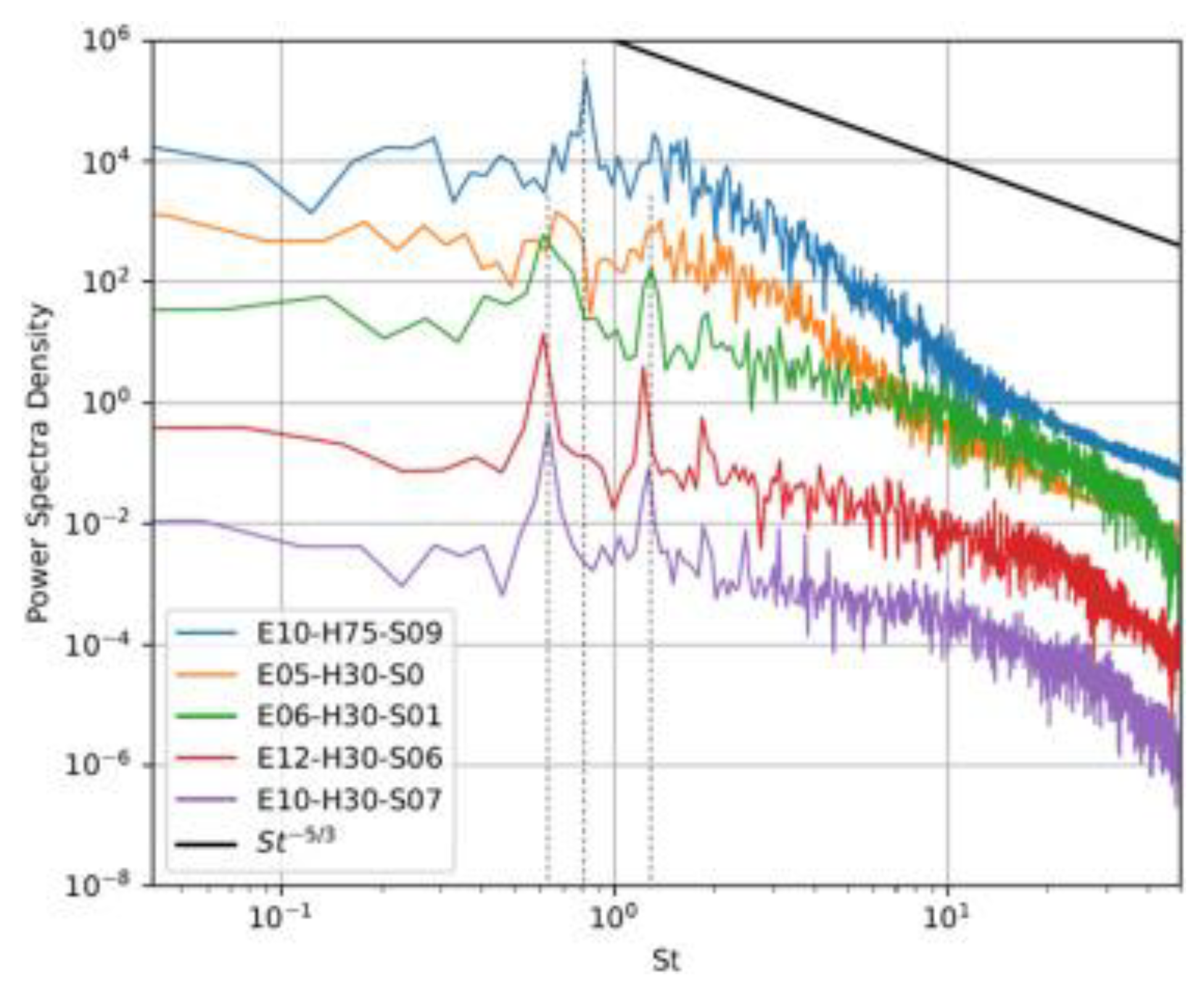

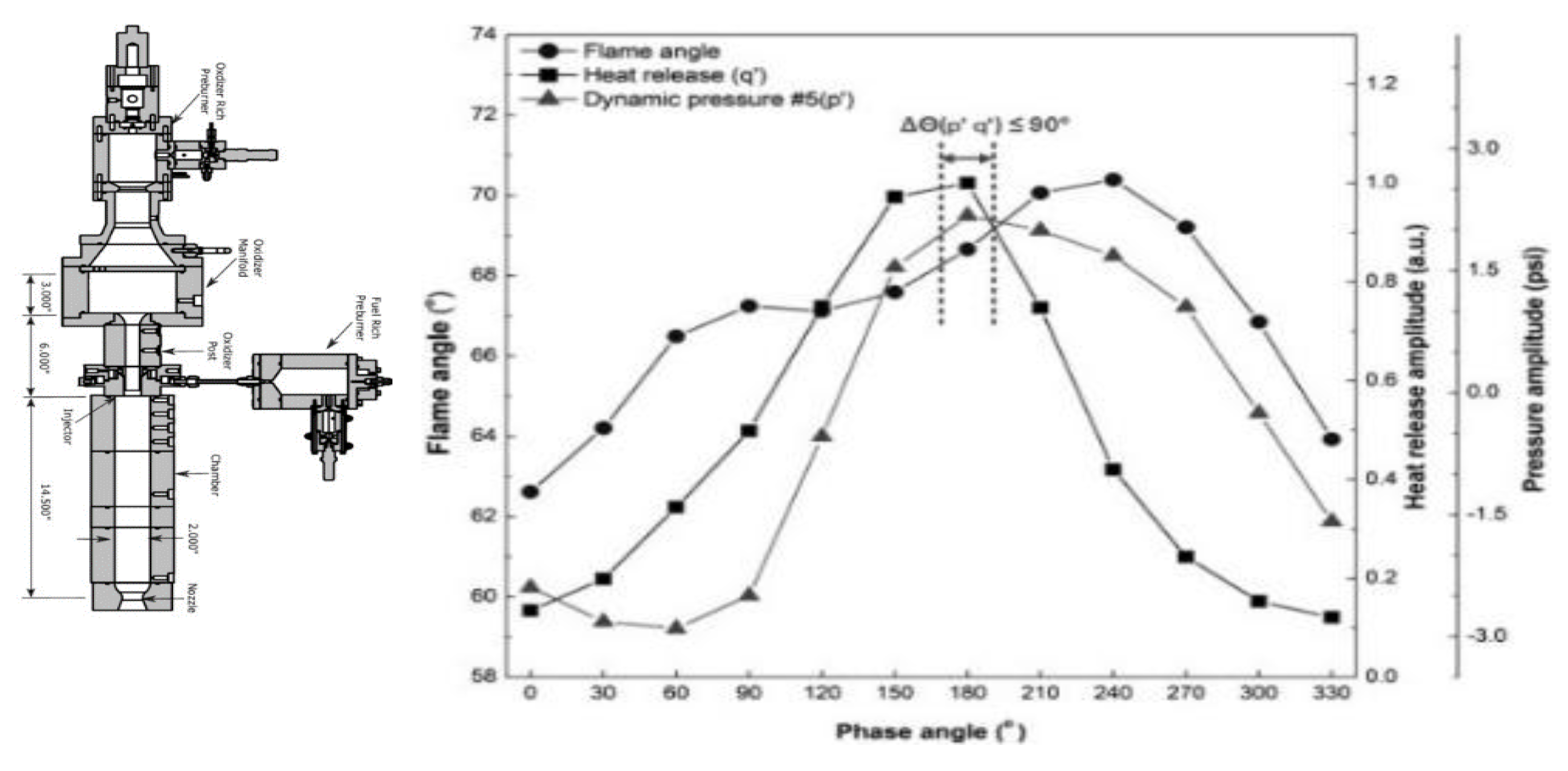

1.4. Thermoacoustic Instability Characteristics of Ammonia Combustion

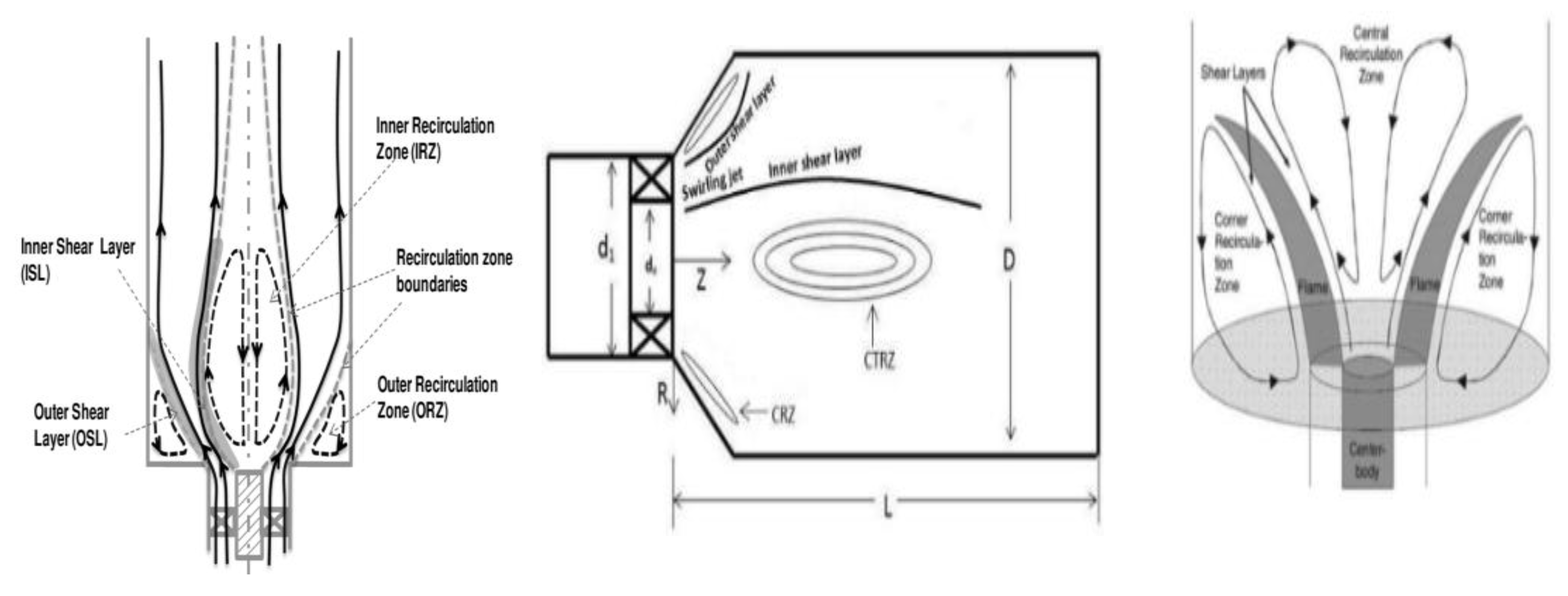

1.5. Elemental Analysis of Combustion Flow and Instability

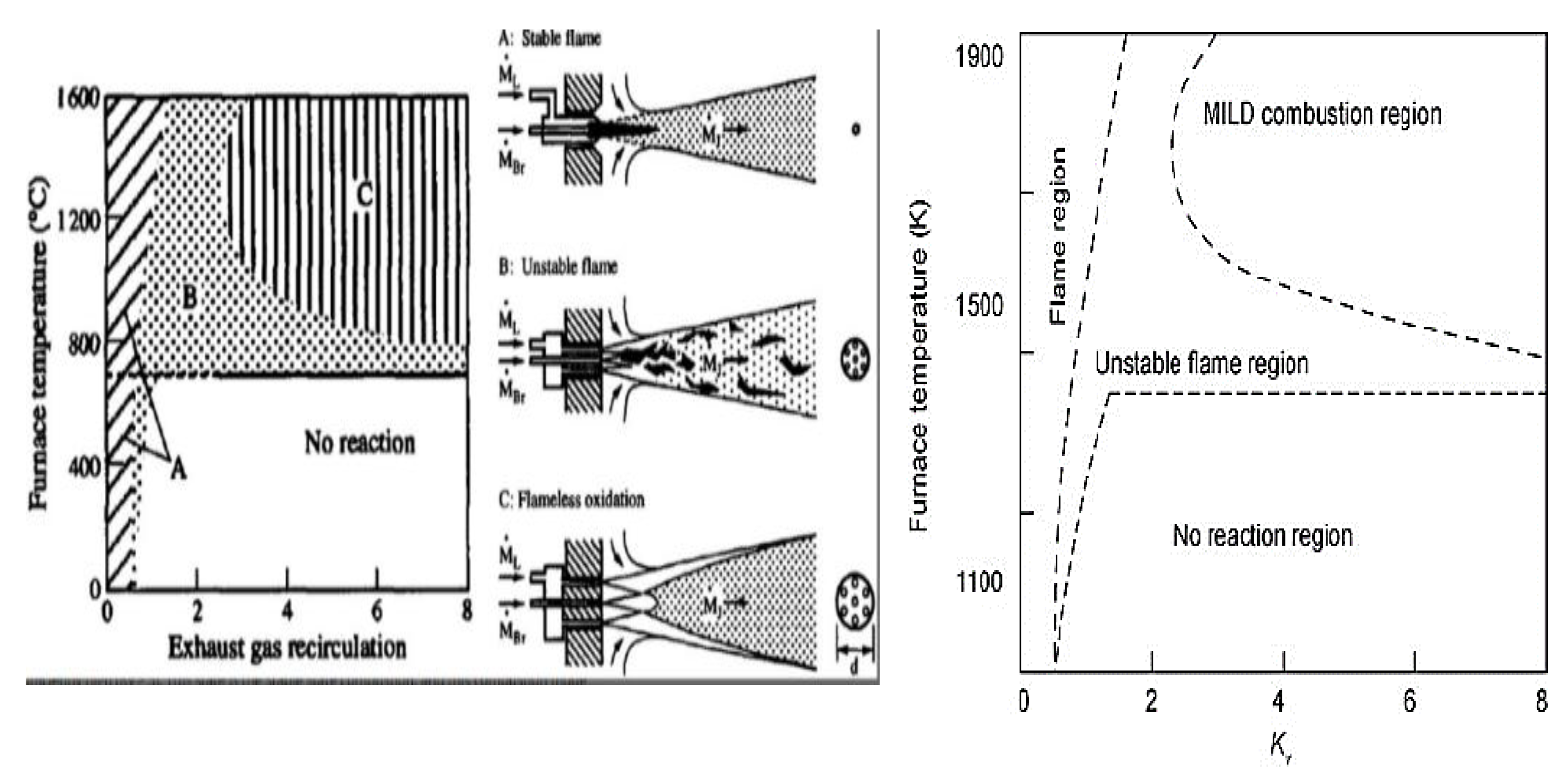

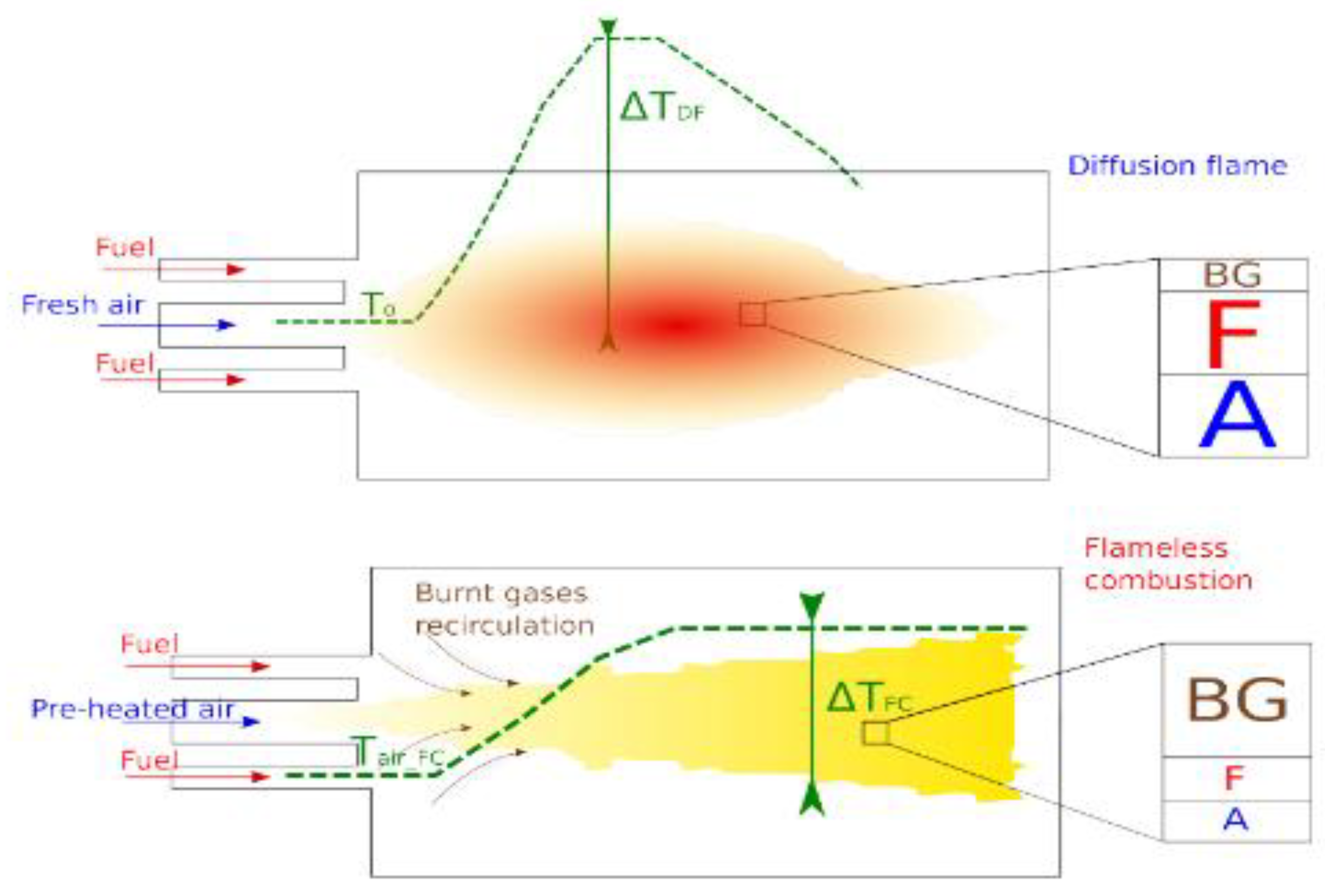

2. Combustion Methods and Stability

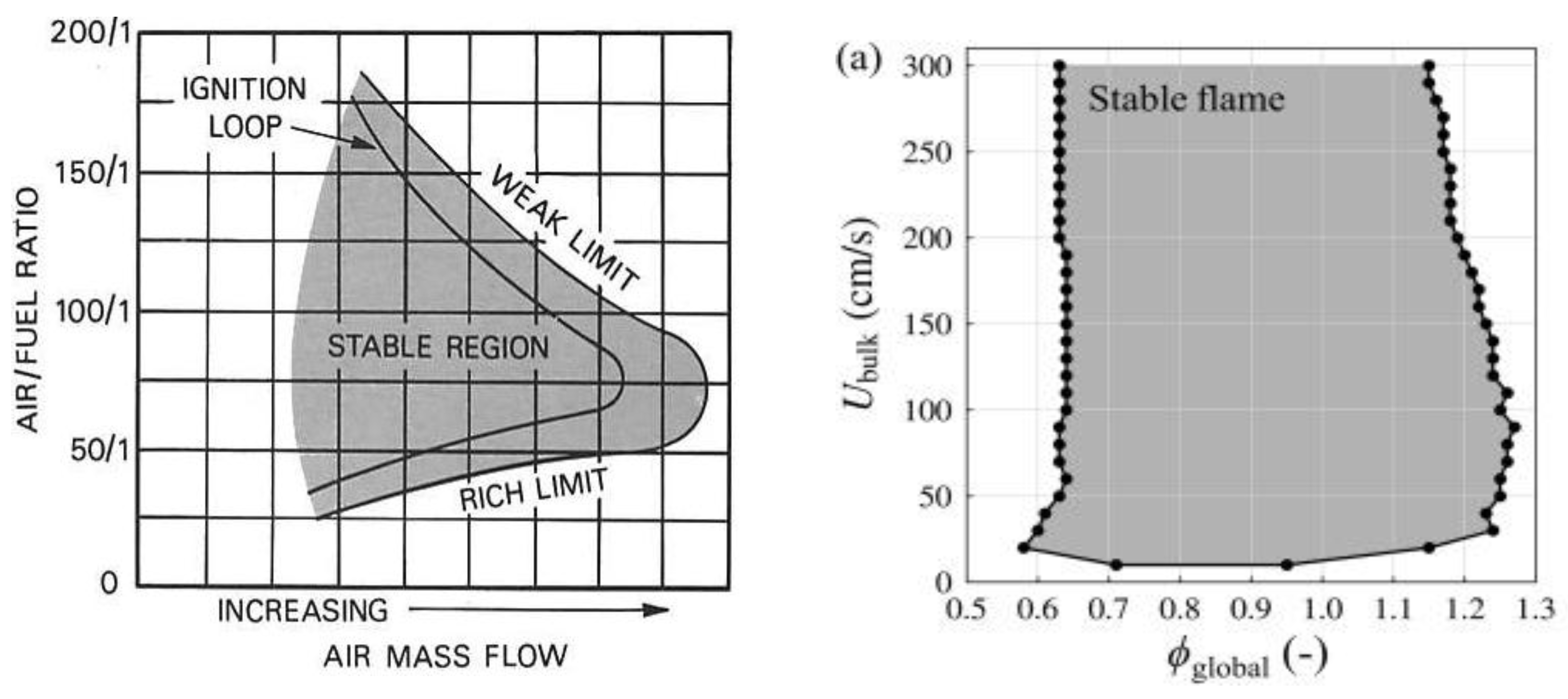

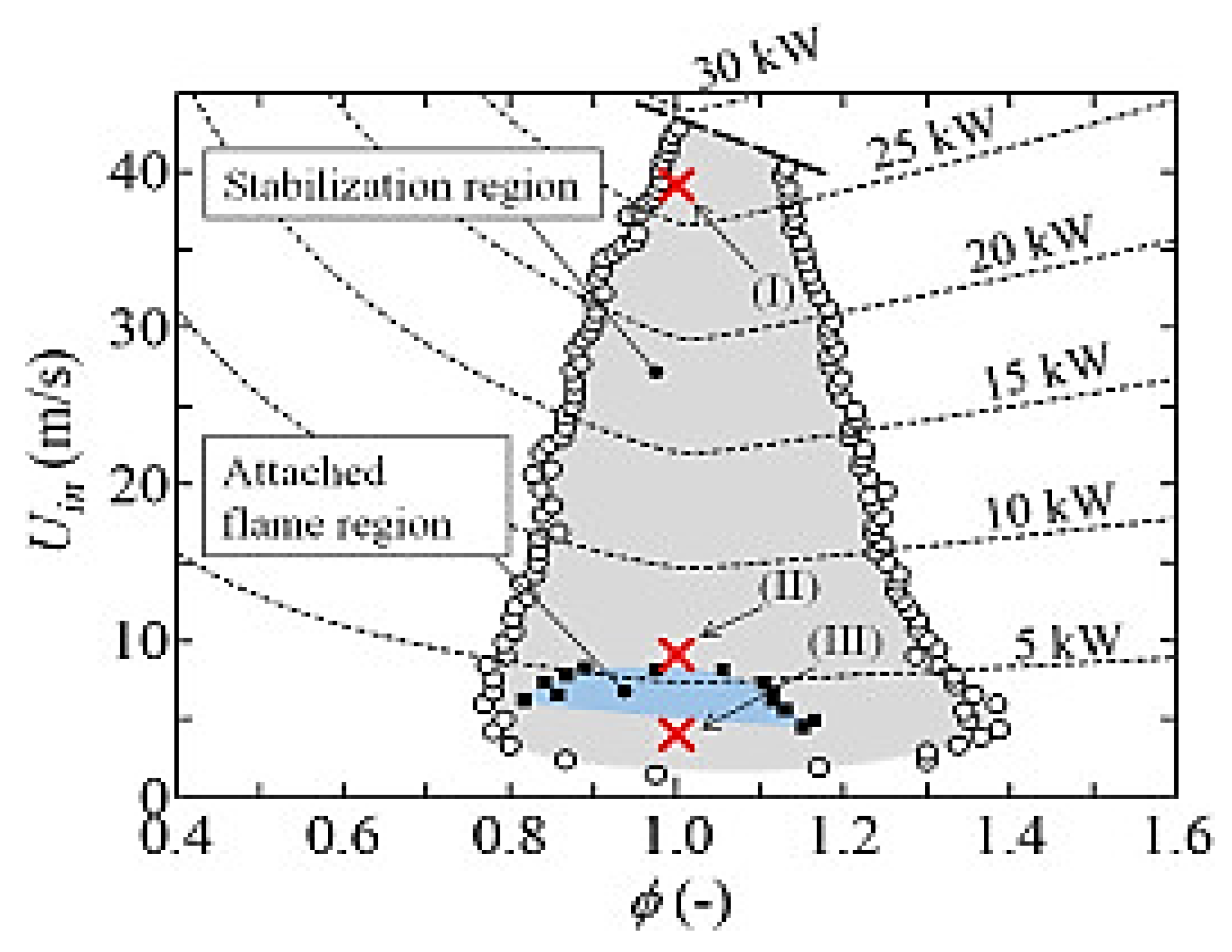

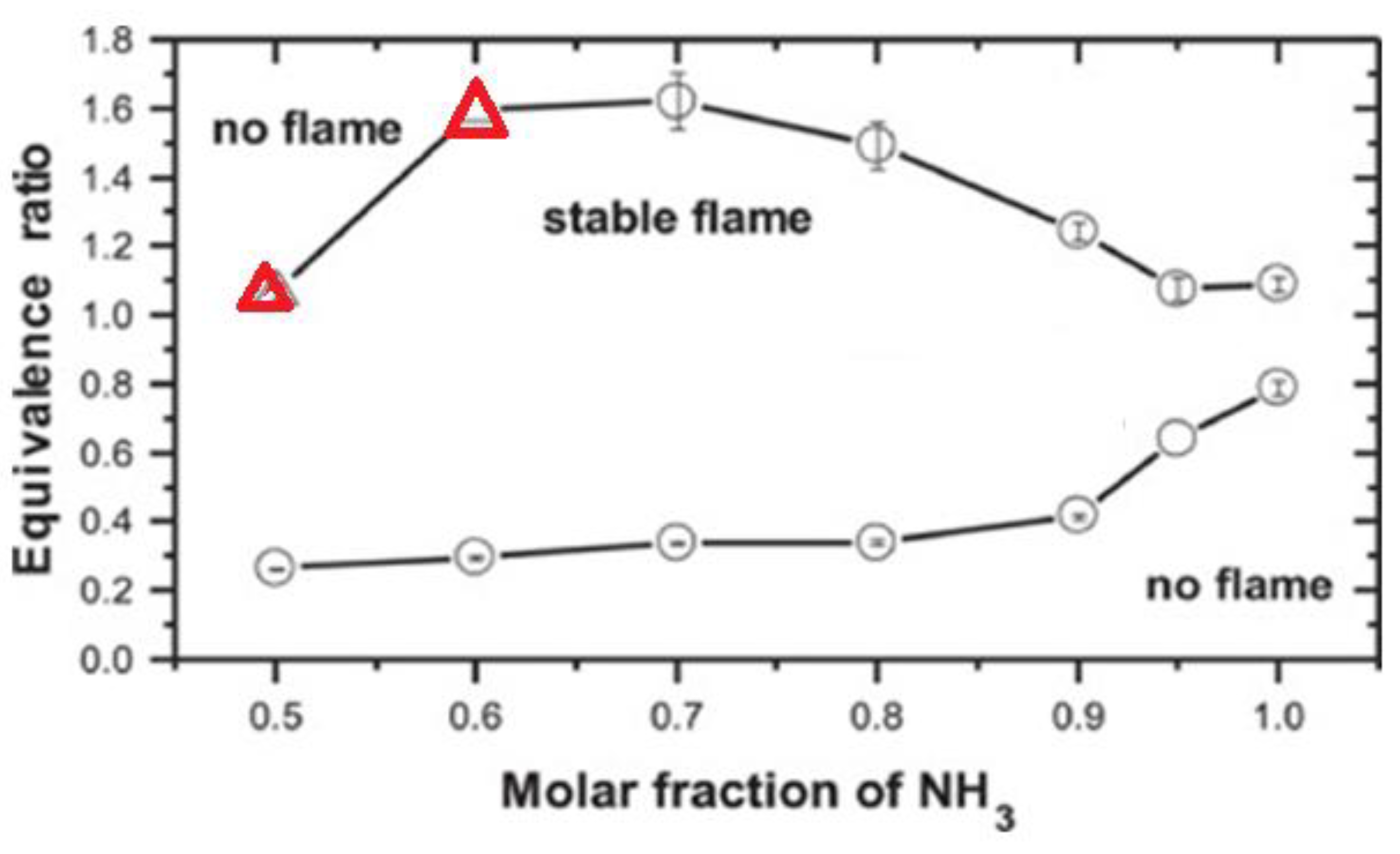

2.1. Ammonia Combustion Stability Conditions and Limits

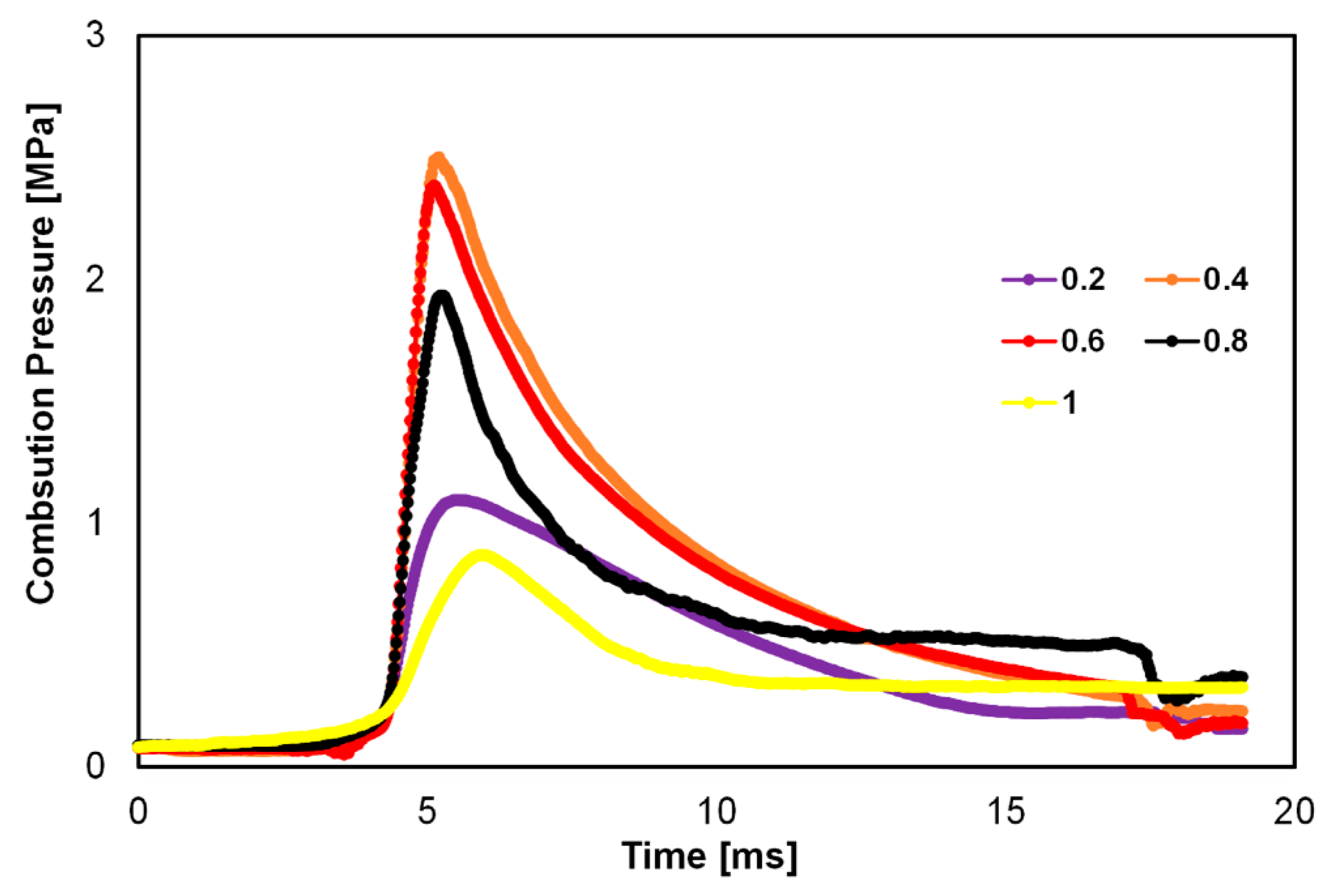

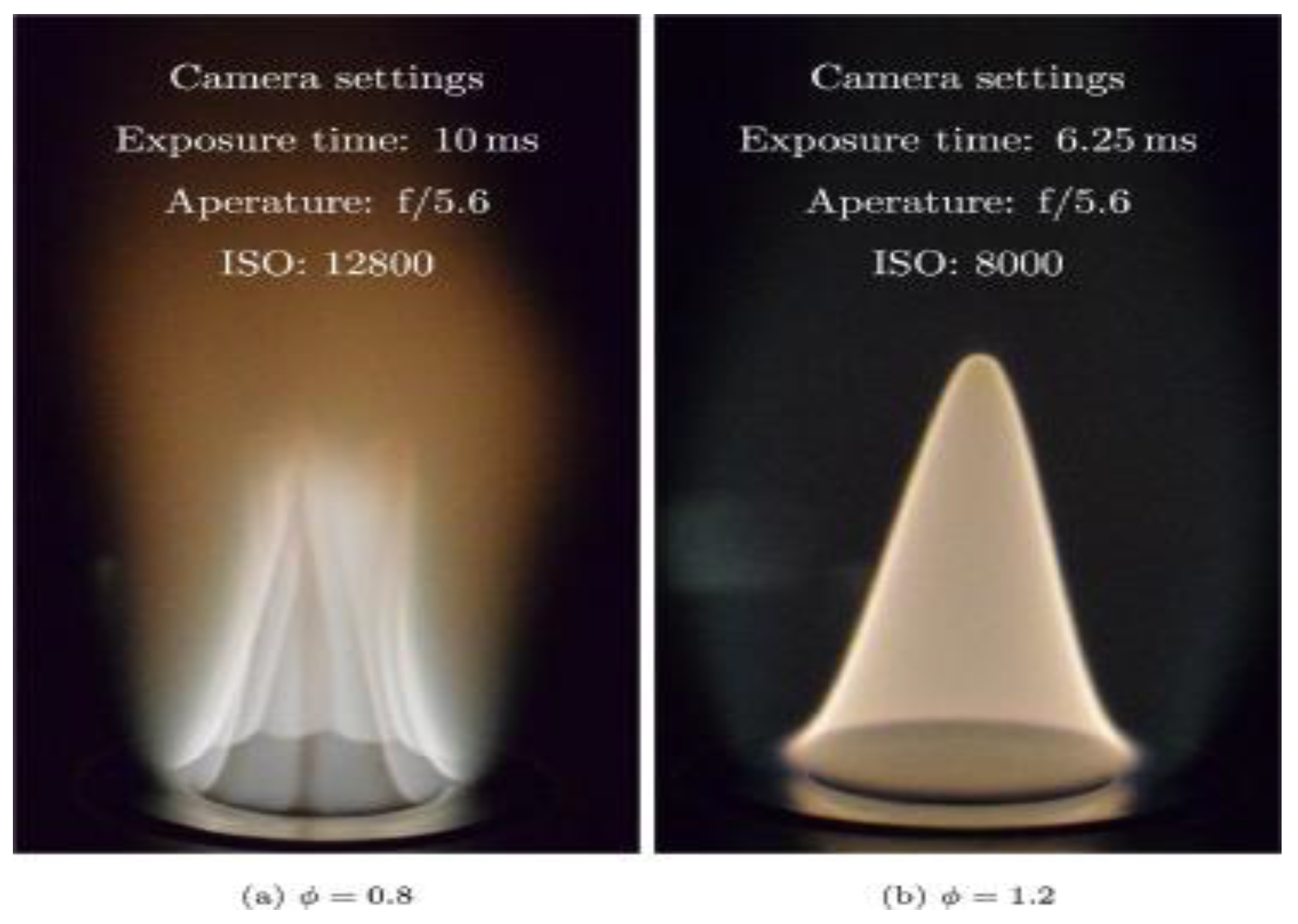

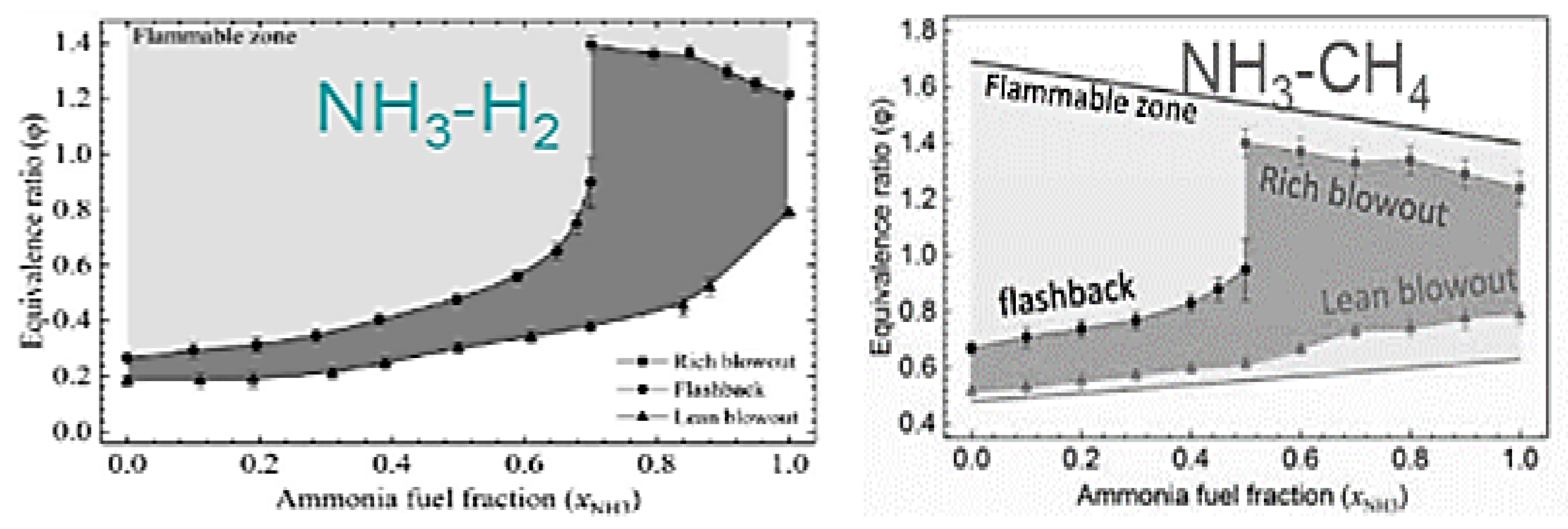

2.2. Effects of Equivalence Ratio on Ammonia Combustion Stability

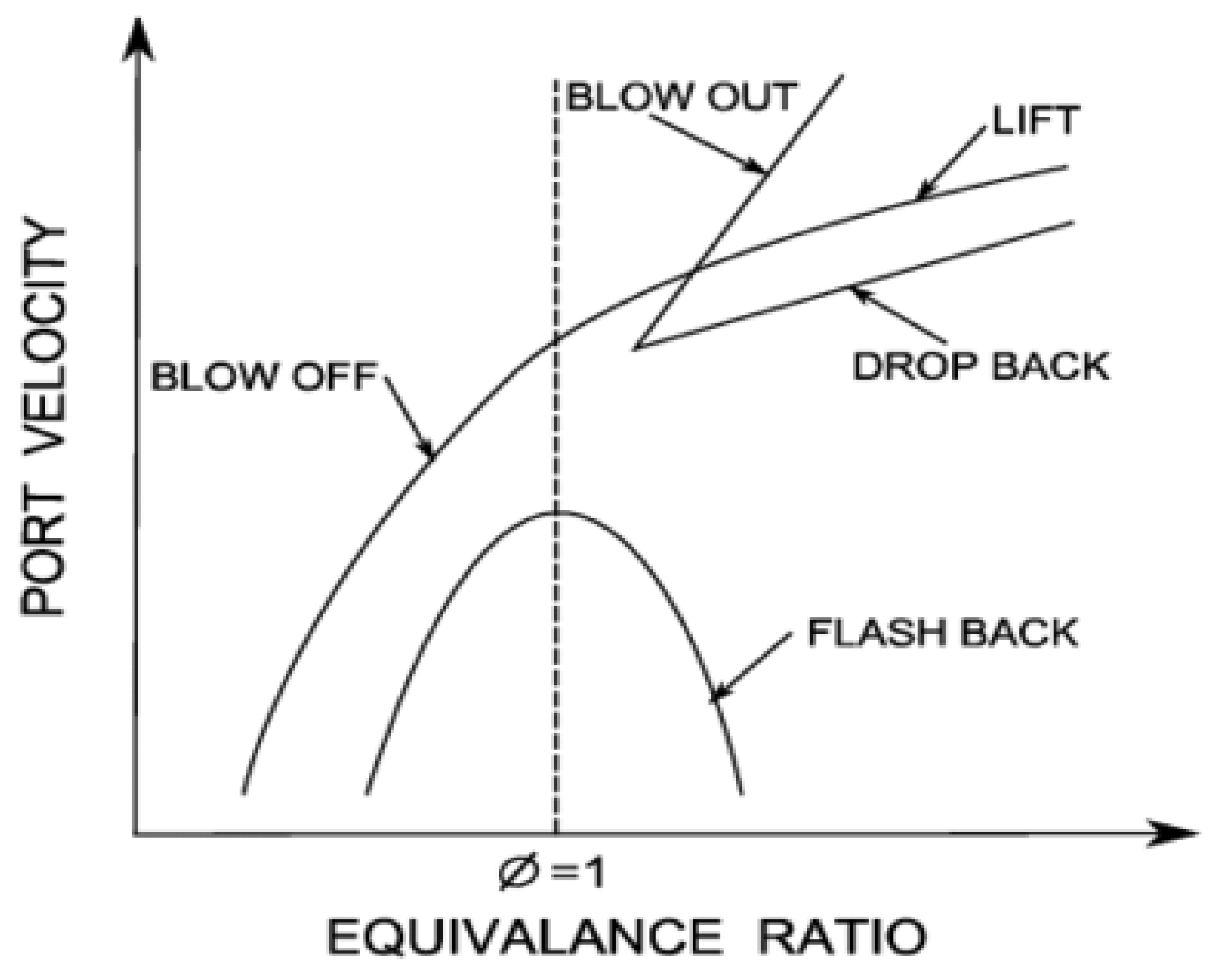

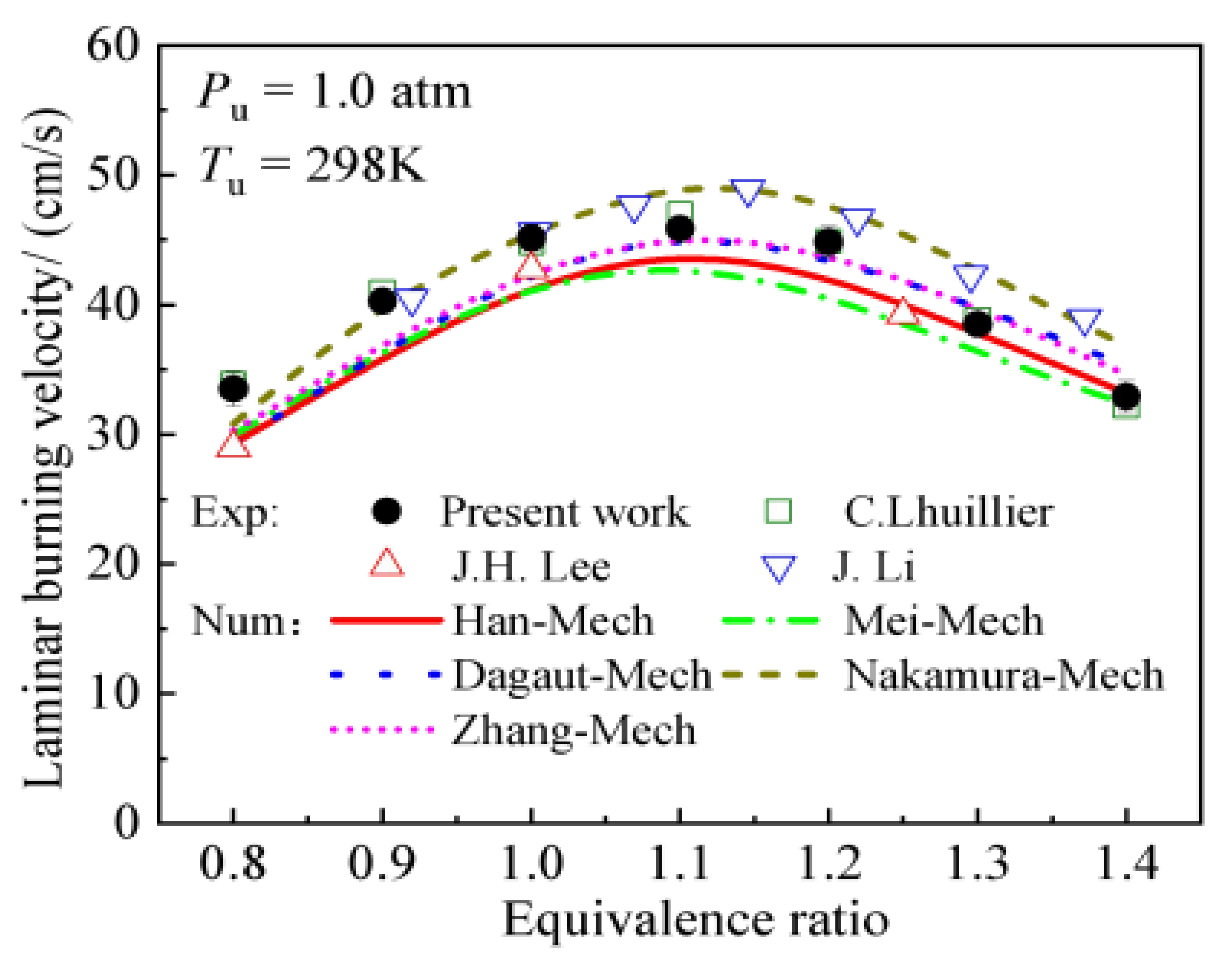

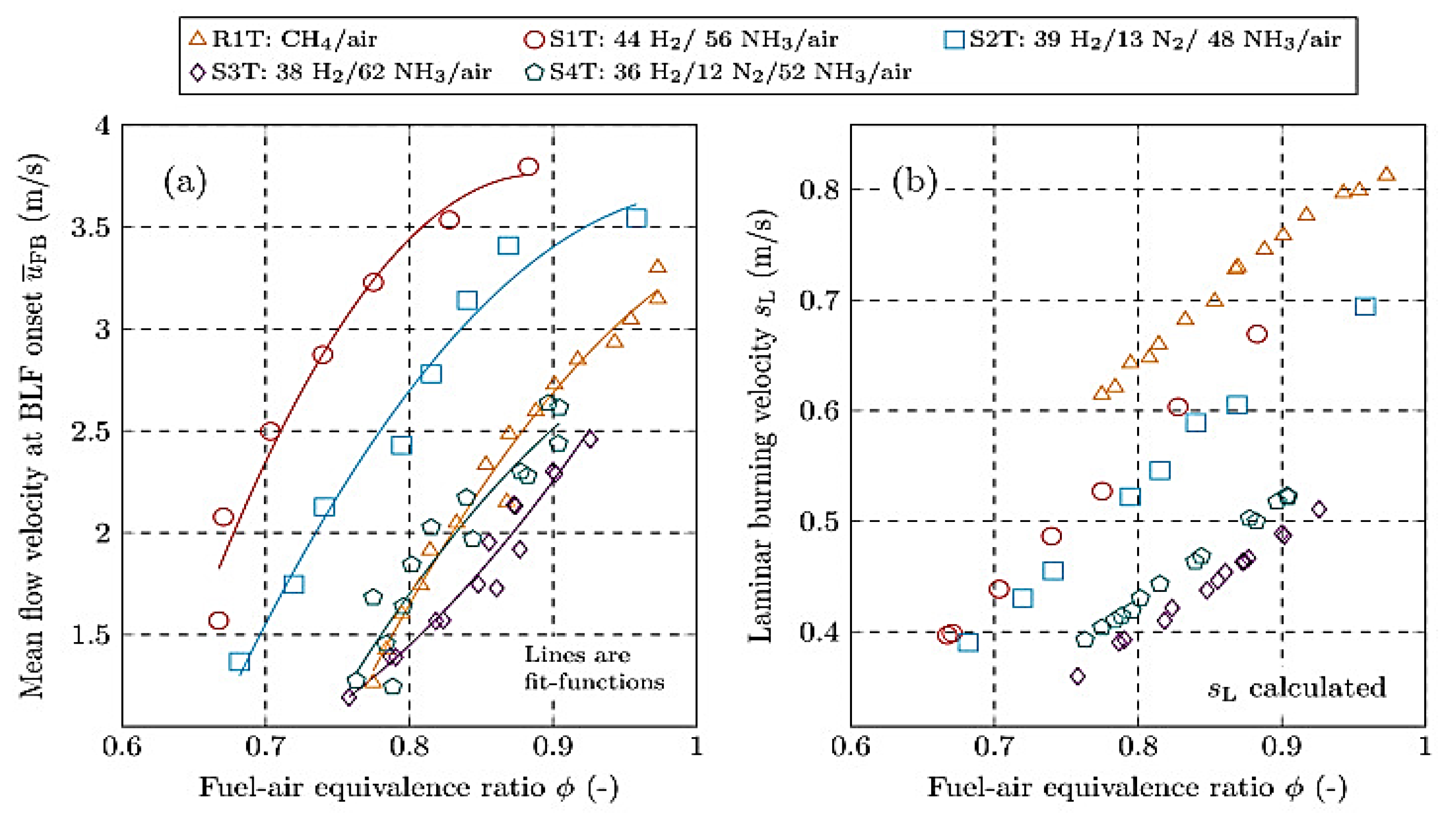

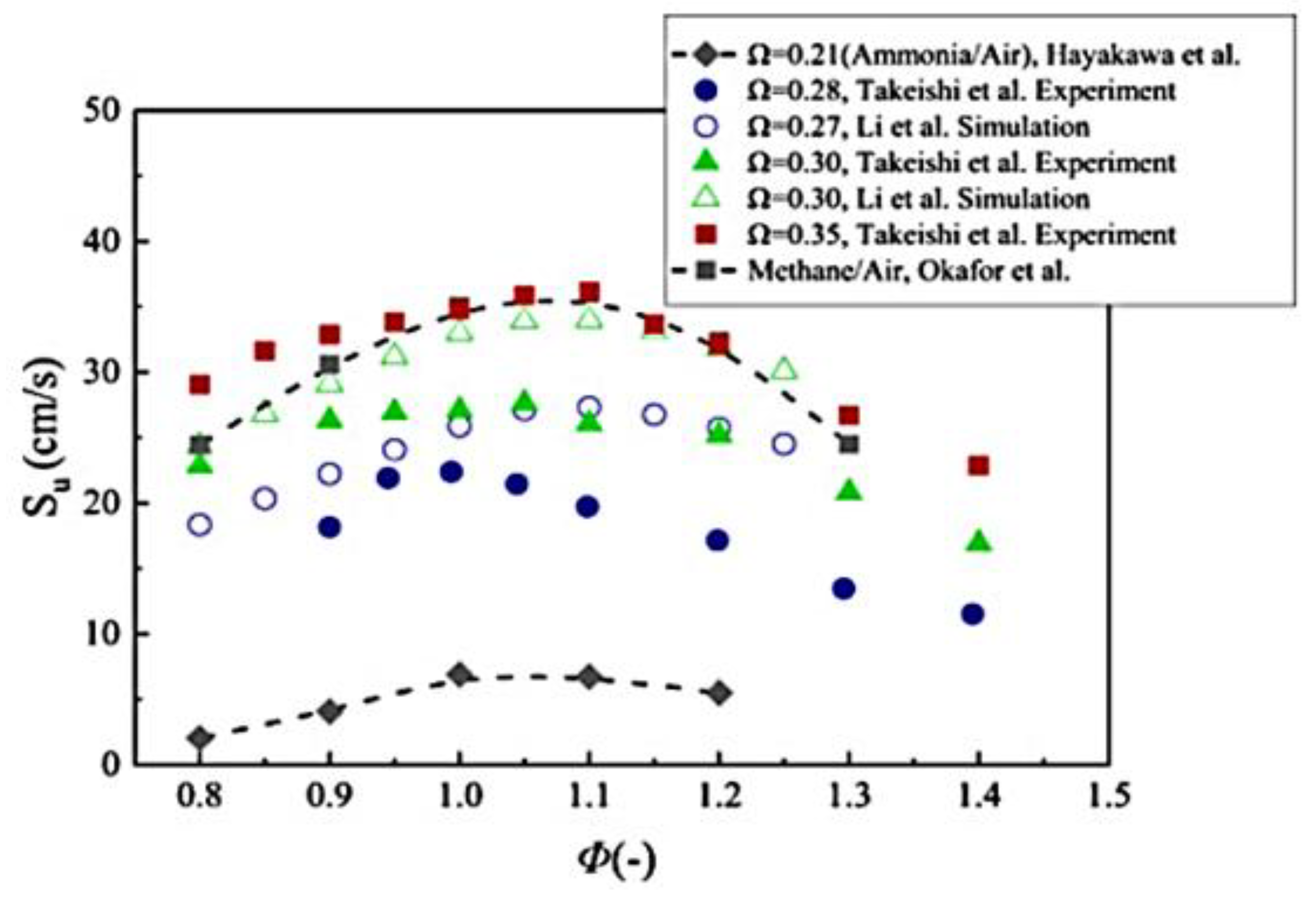

2.3. Effect of Ammonia Laminar Flame Speed on Combustion Stability

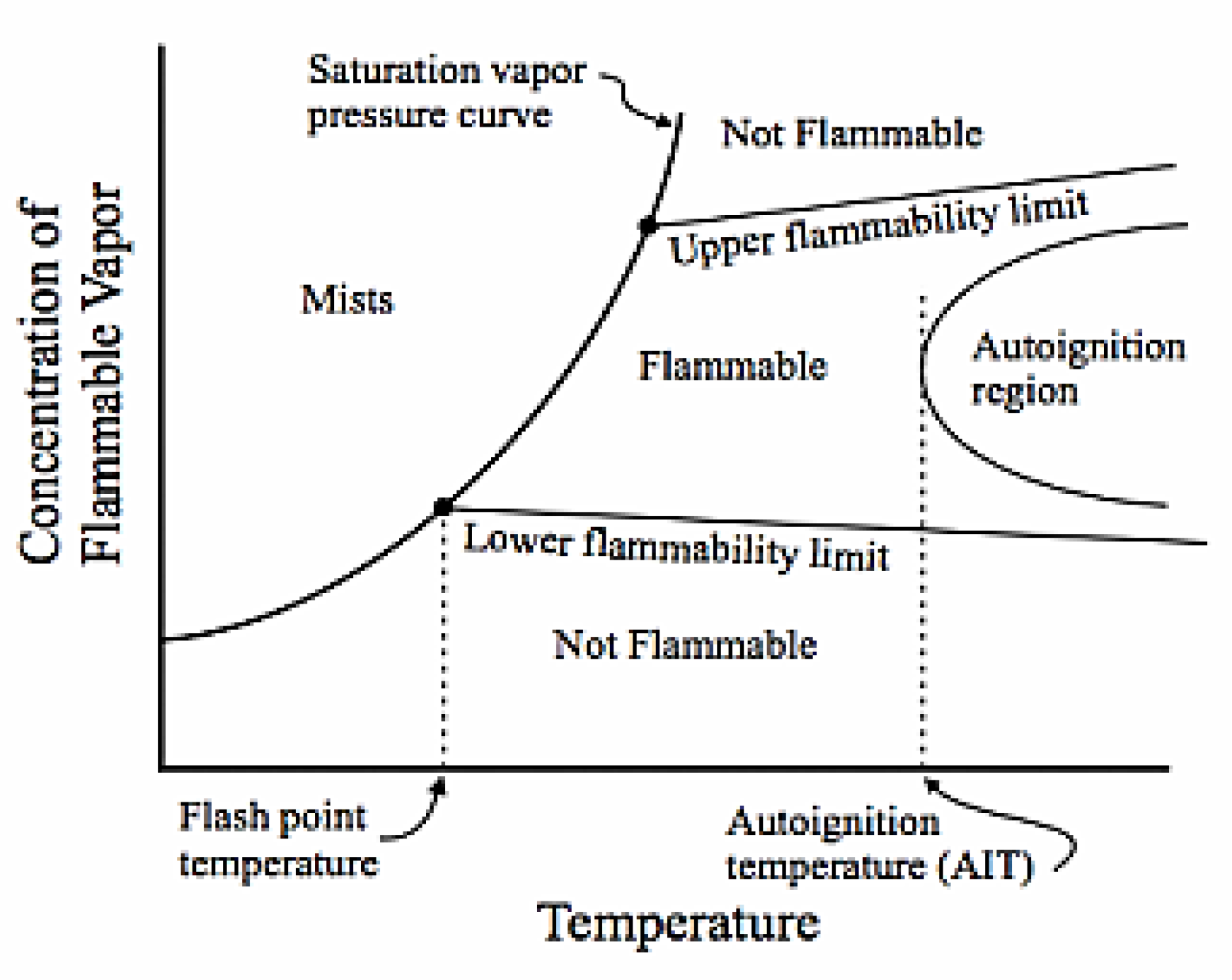

2.4. Effects of Ignition Temperature on Ammonia Combustion Stability in

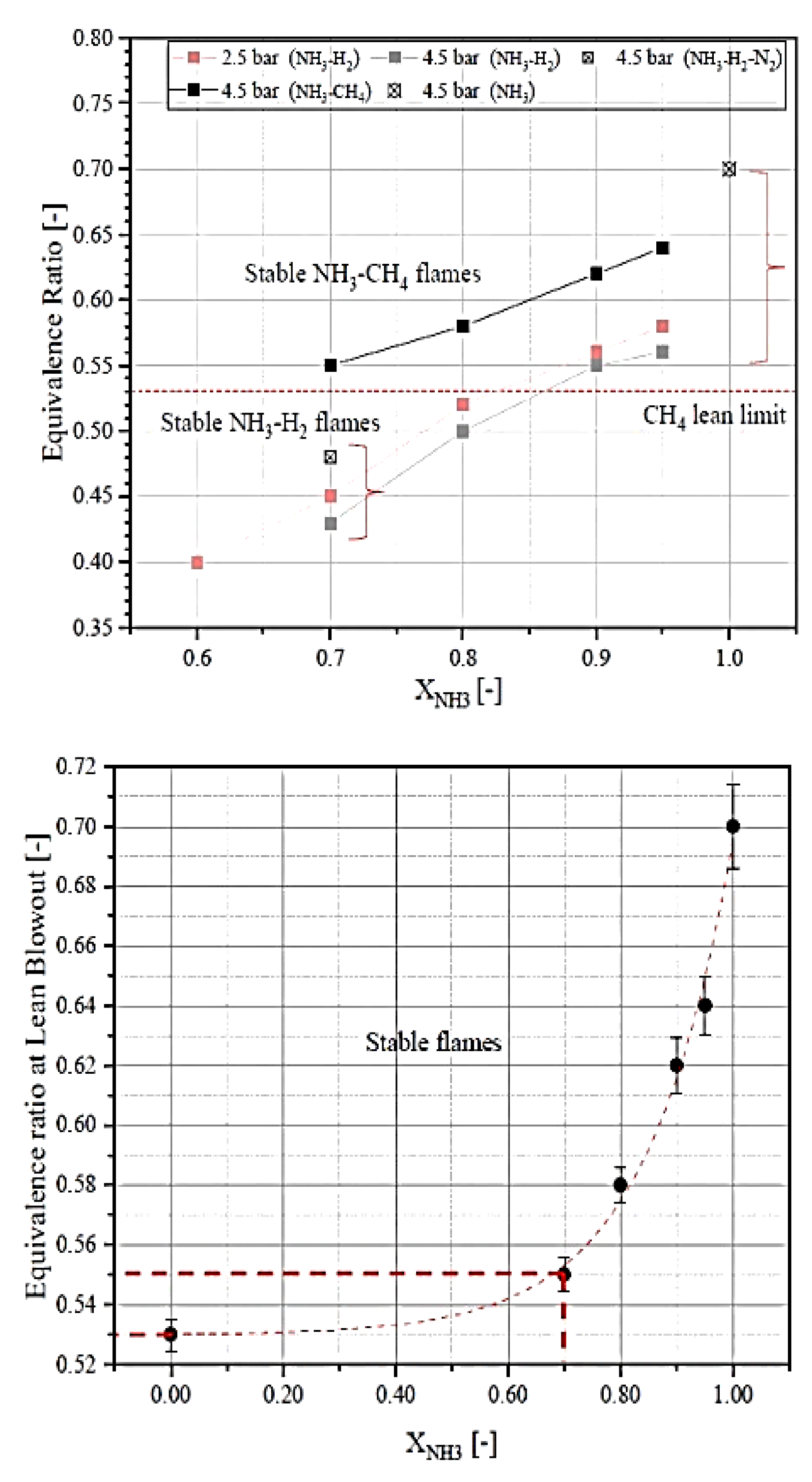

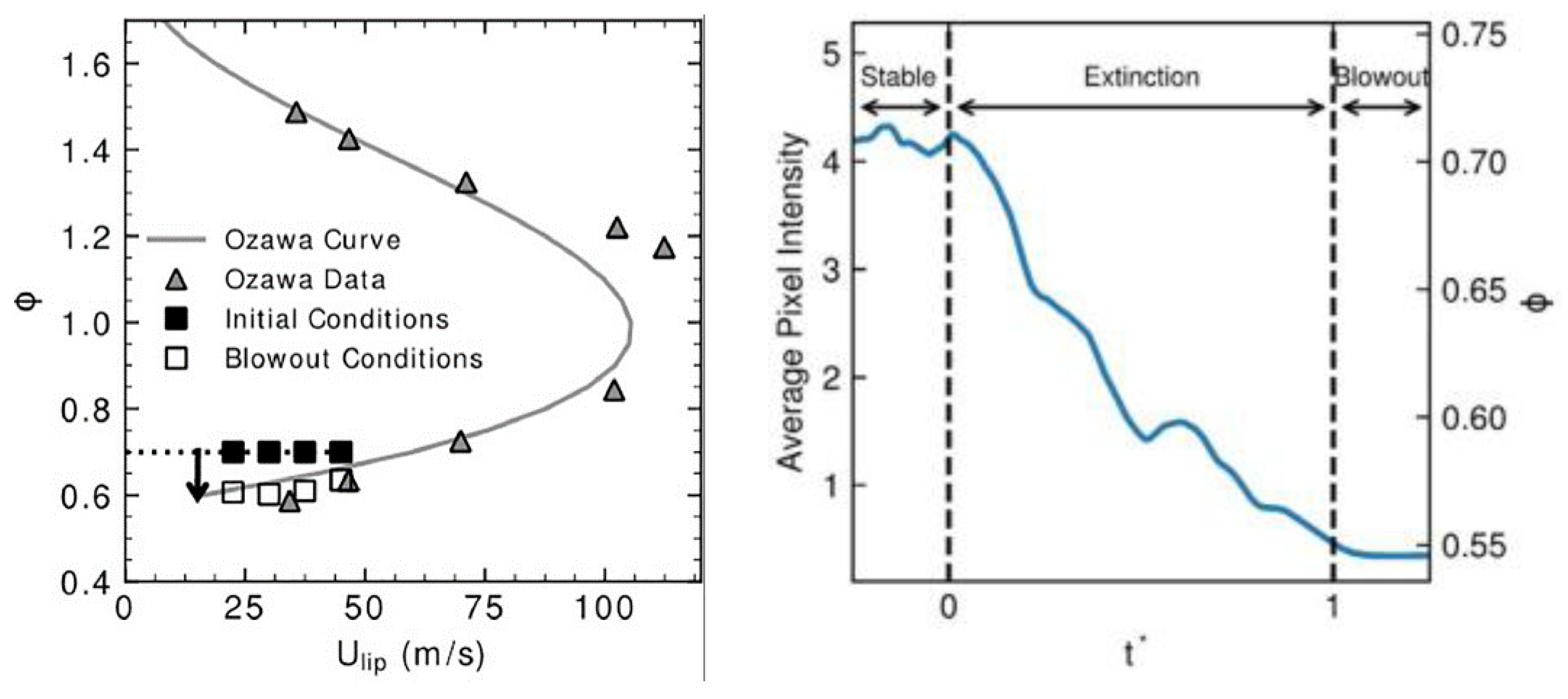

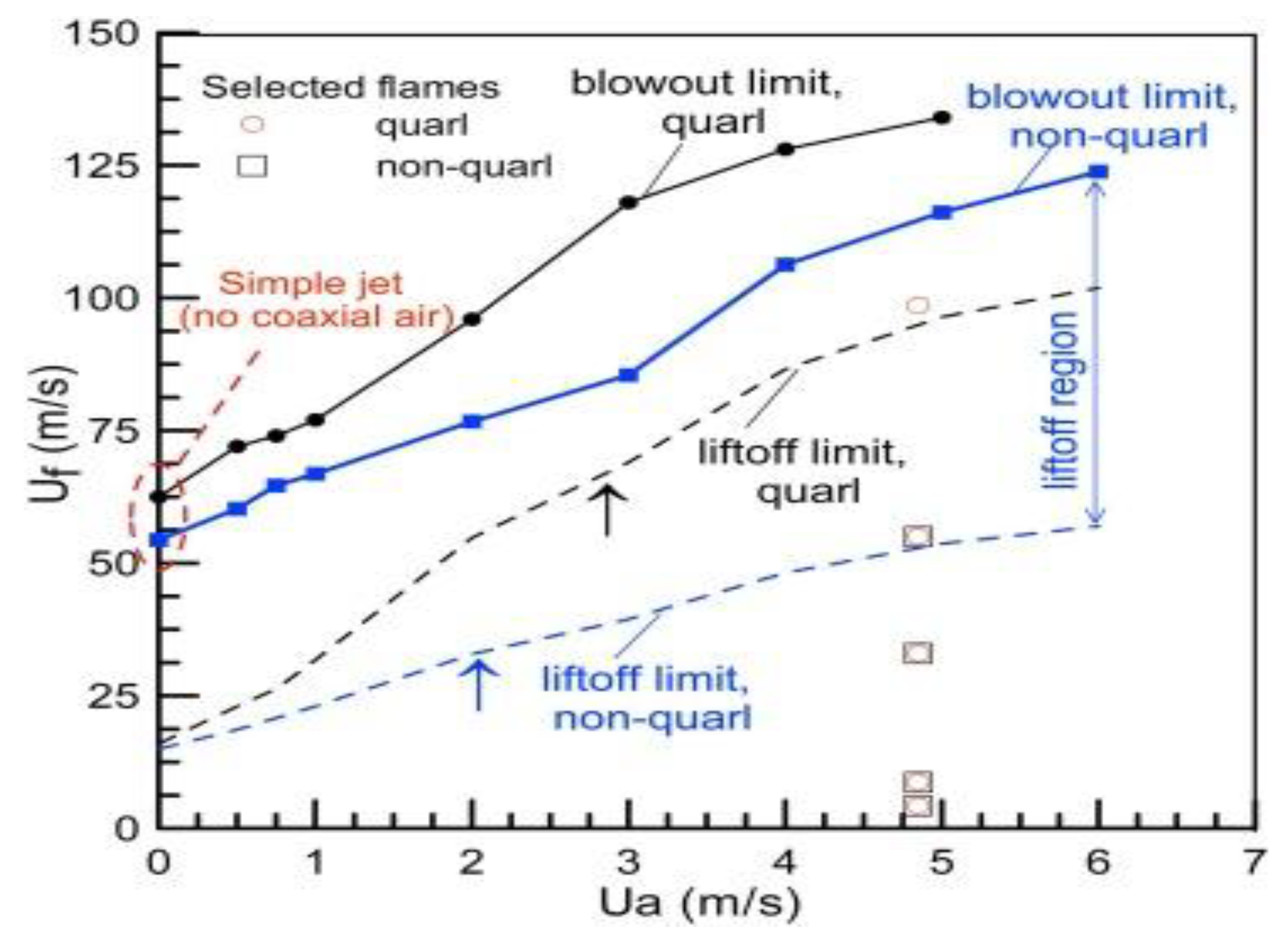

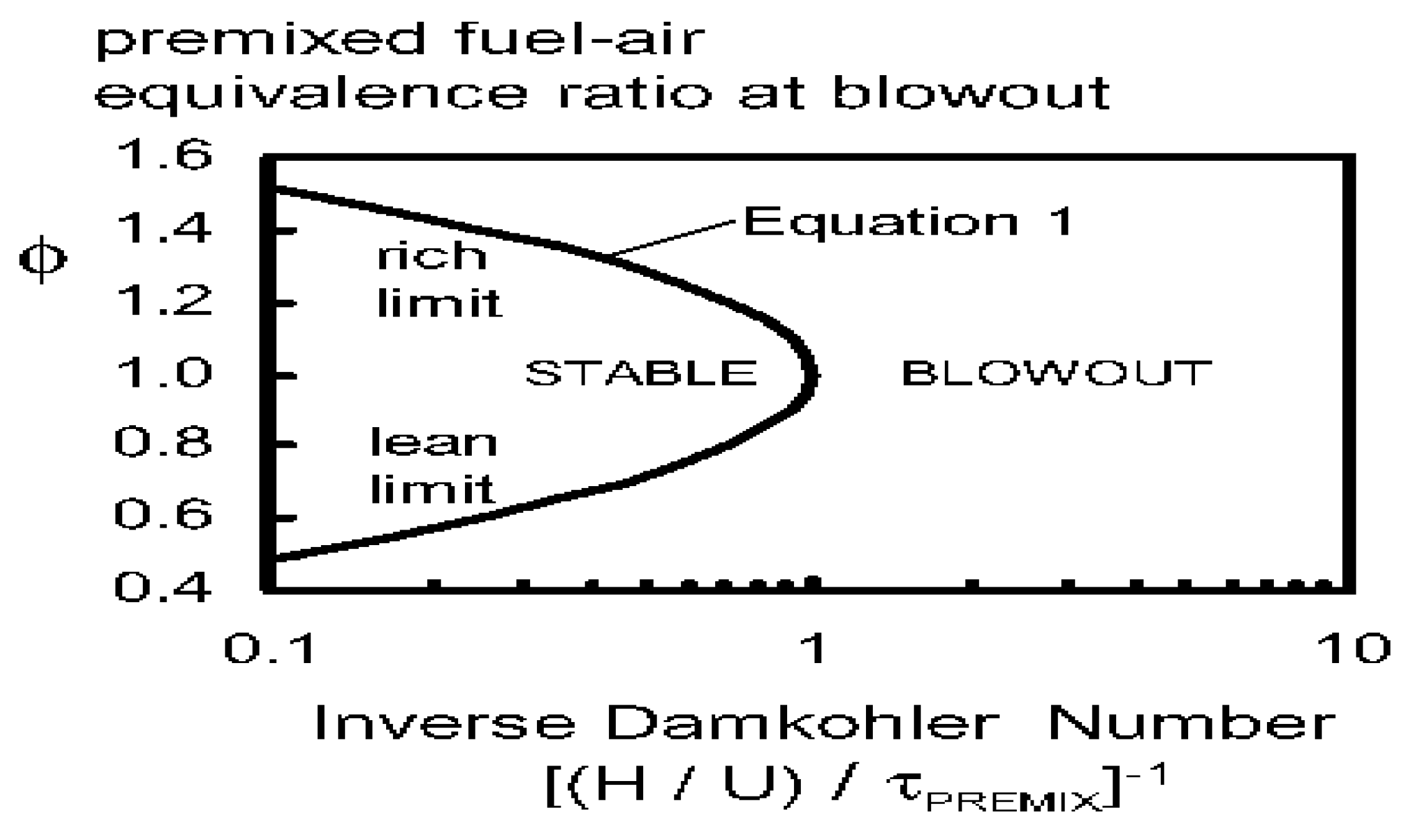

2.5. The Lean Blow-Off Limit and the Stability of Ammonia Flame

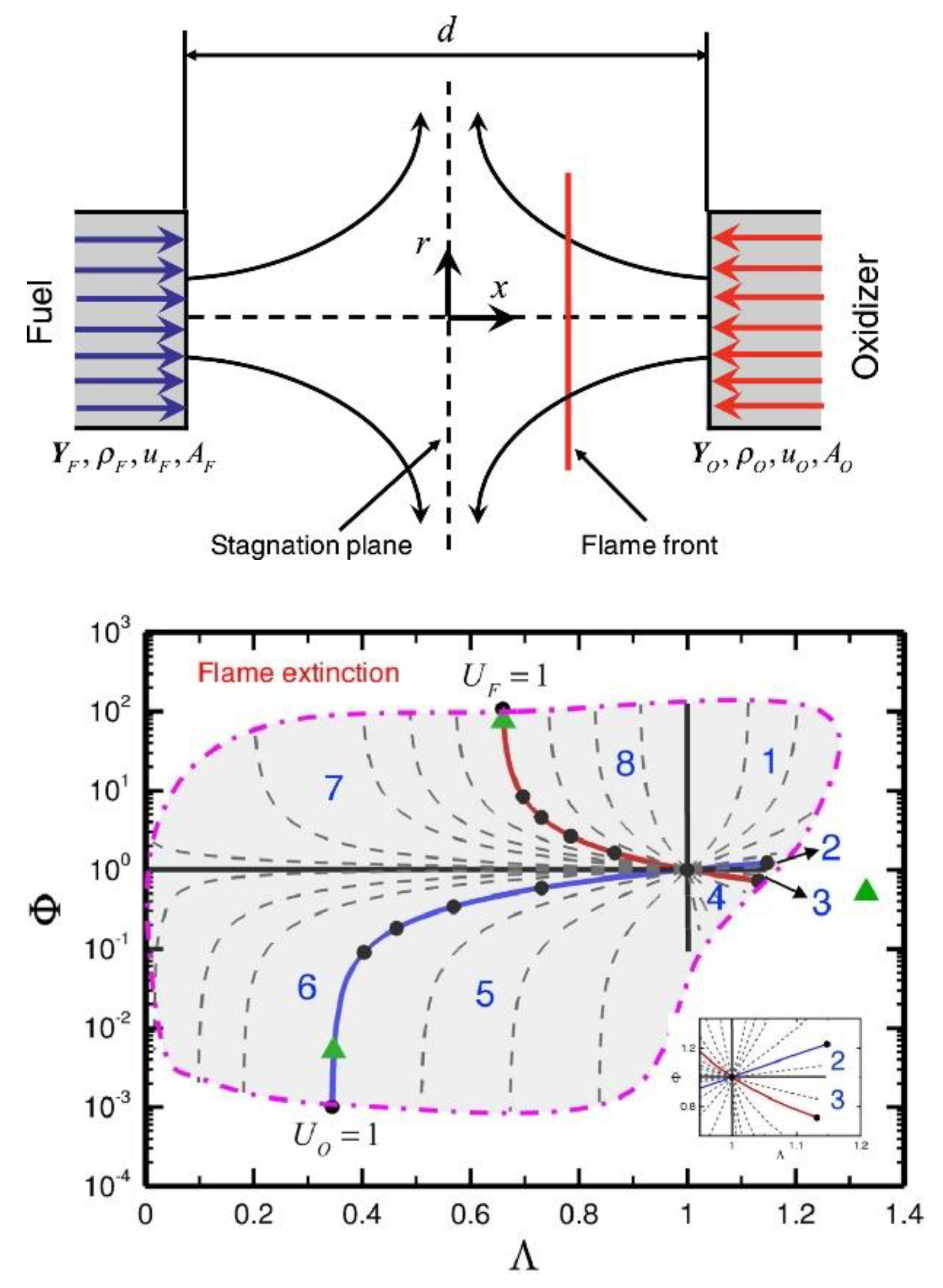

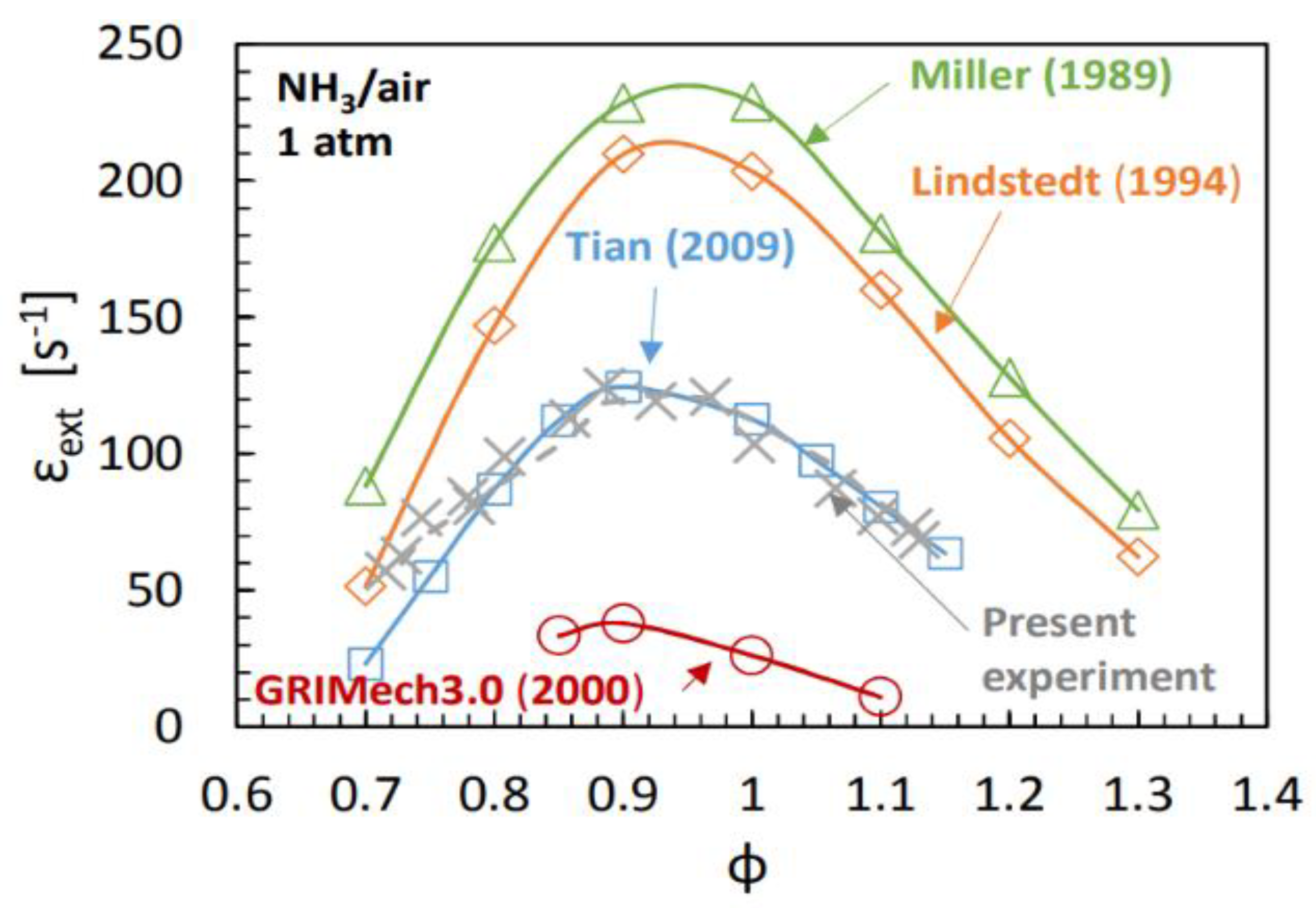

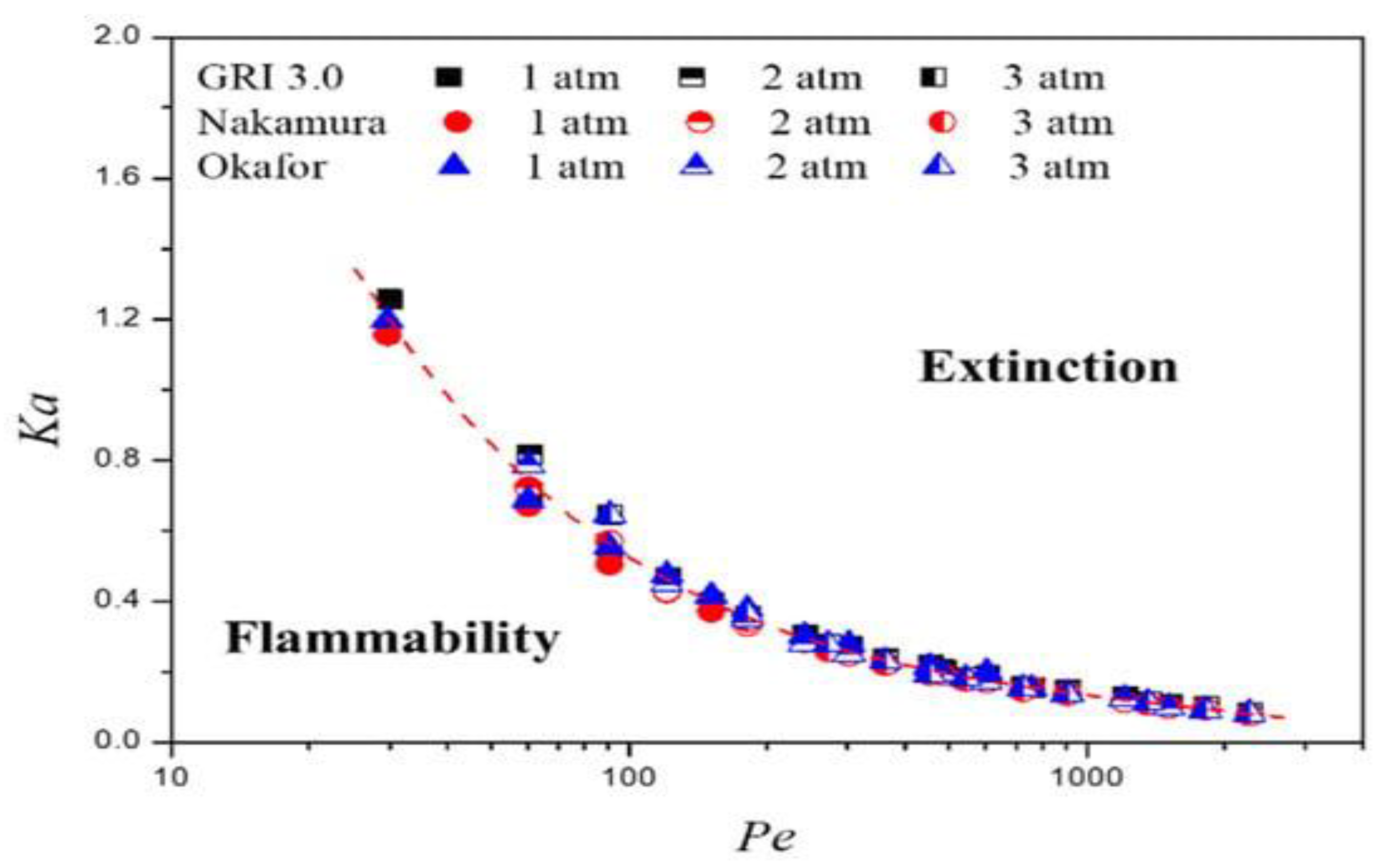

2.6. The Extinction of Ammonia Combustion Flame

2.7. The Heat Released Characteristics and Ammonia Combustion Stability

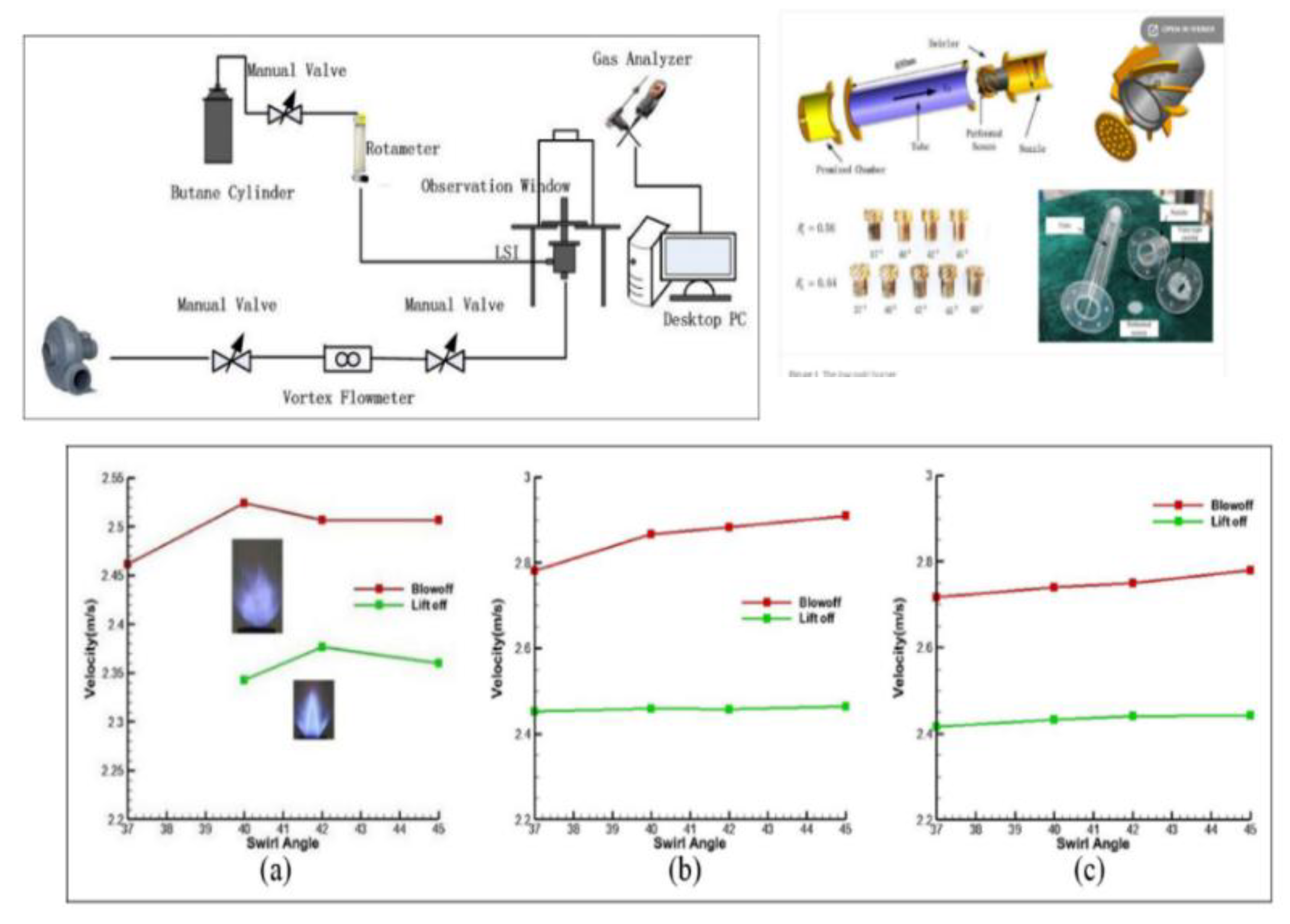

2.8. Effects of Swirl Number on Ammonia Combustion Stability

2.9. Effects of Residence Time on Ammonia Combustion Stability

2.10. Effects of O2 Concentrations on Ammonia Combustion Stability

2.11. Effects of Fuel Composition and Species on Ammonia Combustion Stability

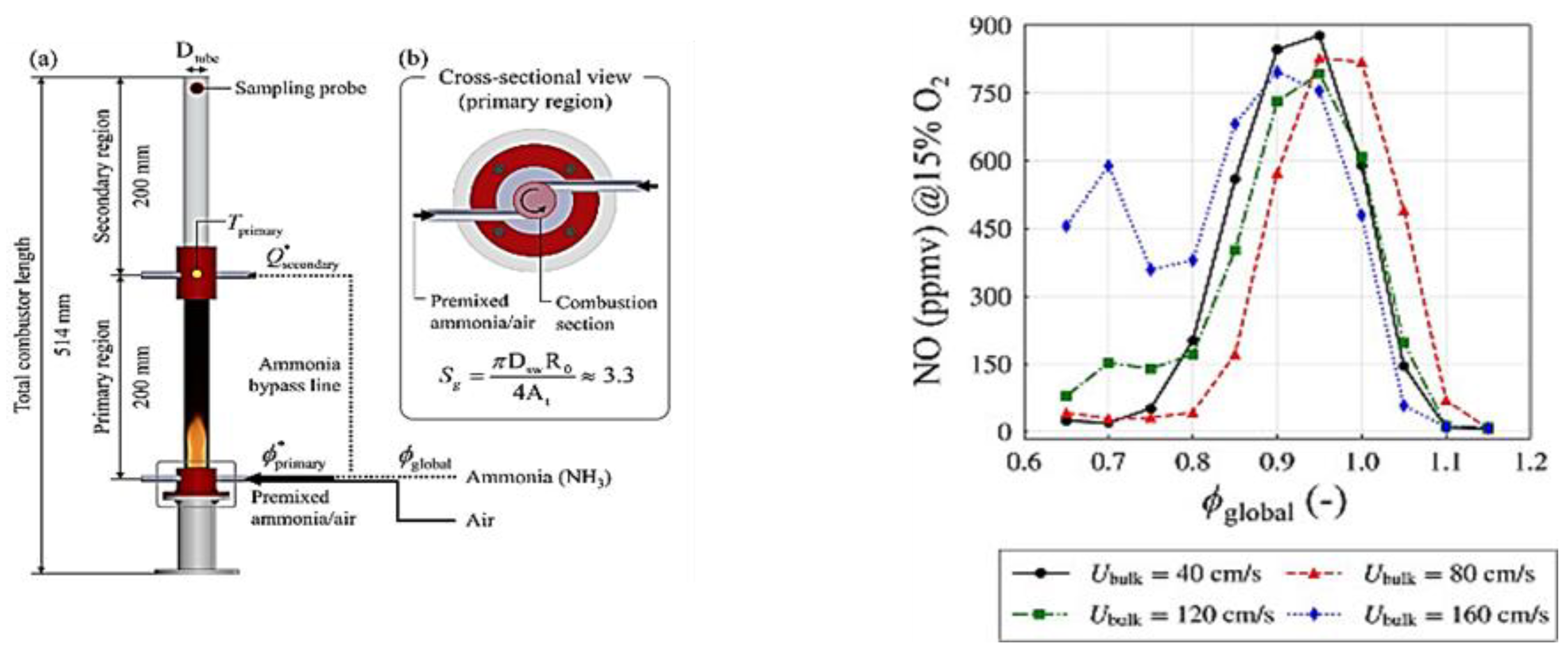

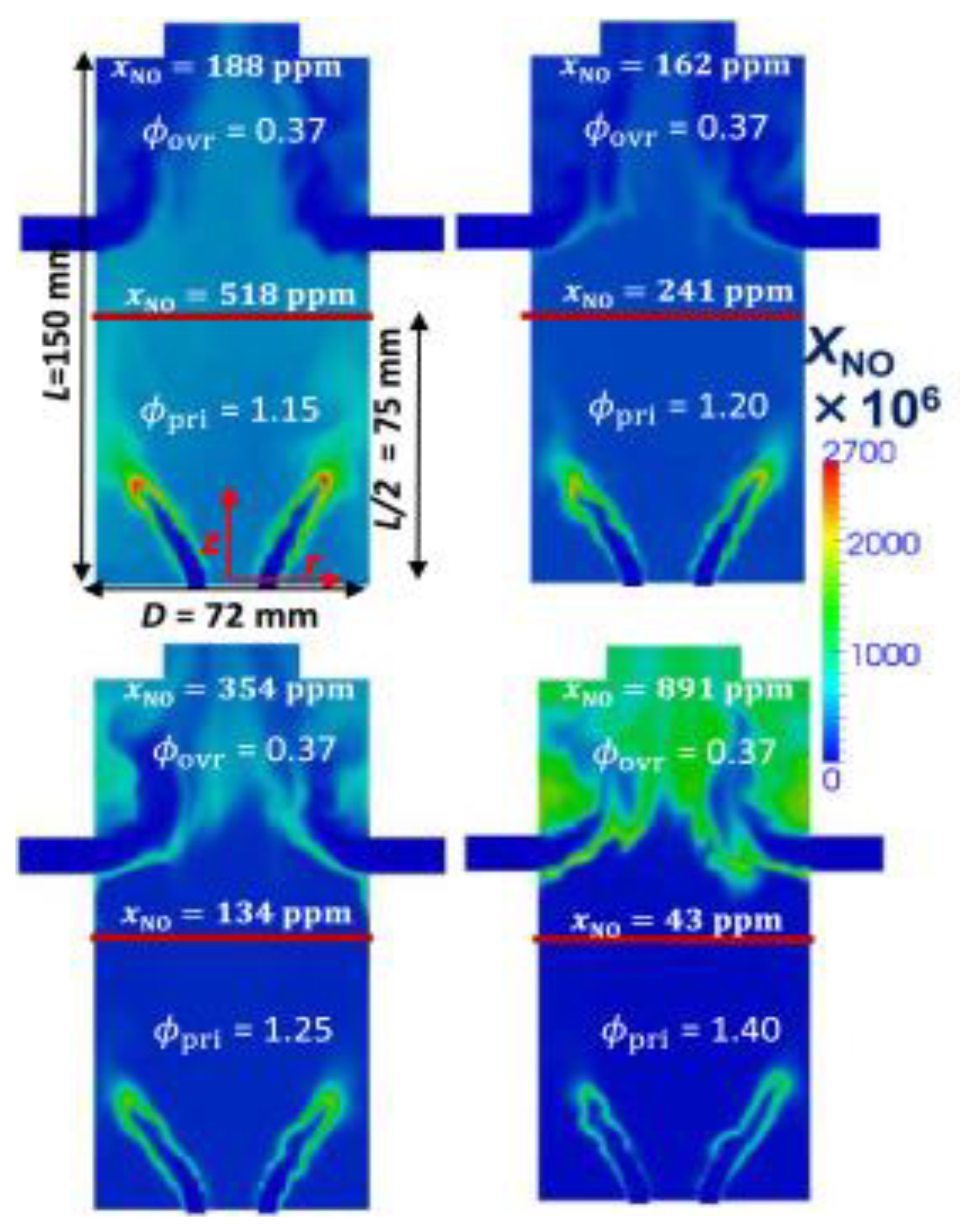

3. Stability Limits and NOx Emission

3.1. NOx and N2O Mitigation from Insdustrial Streams

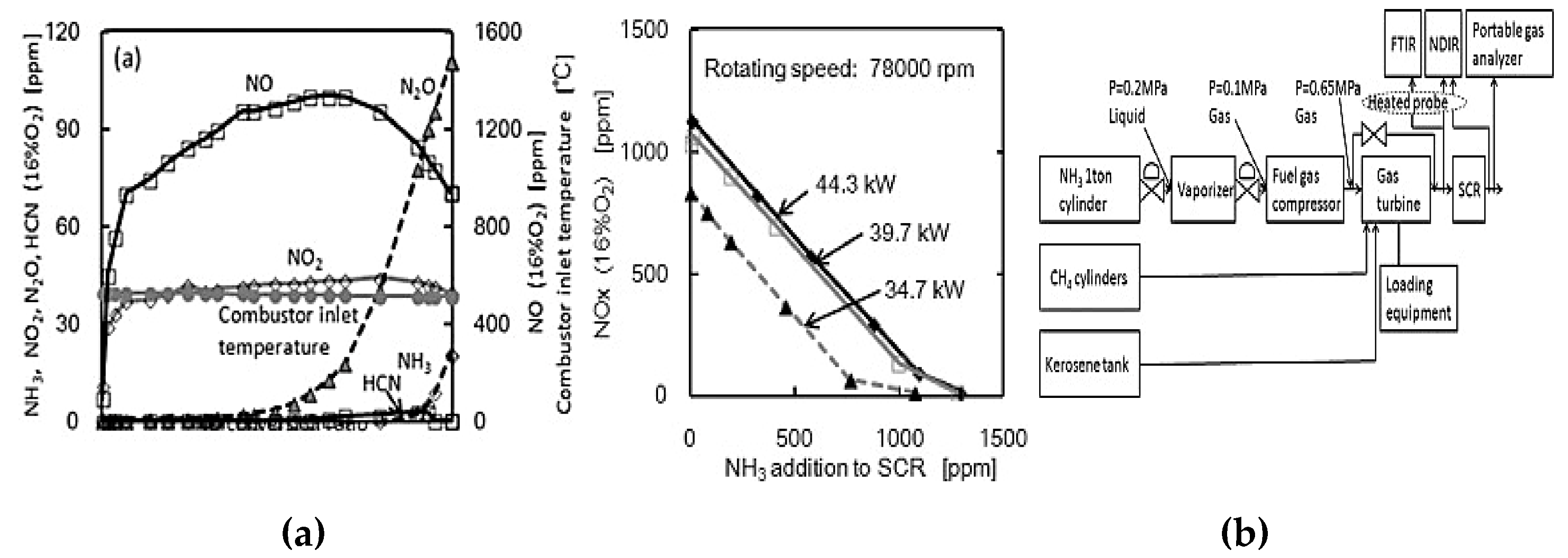

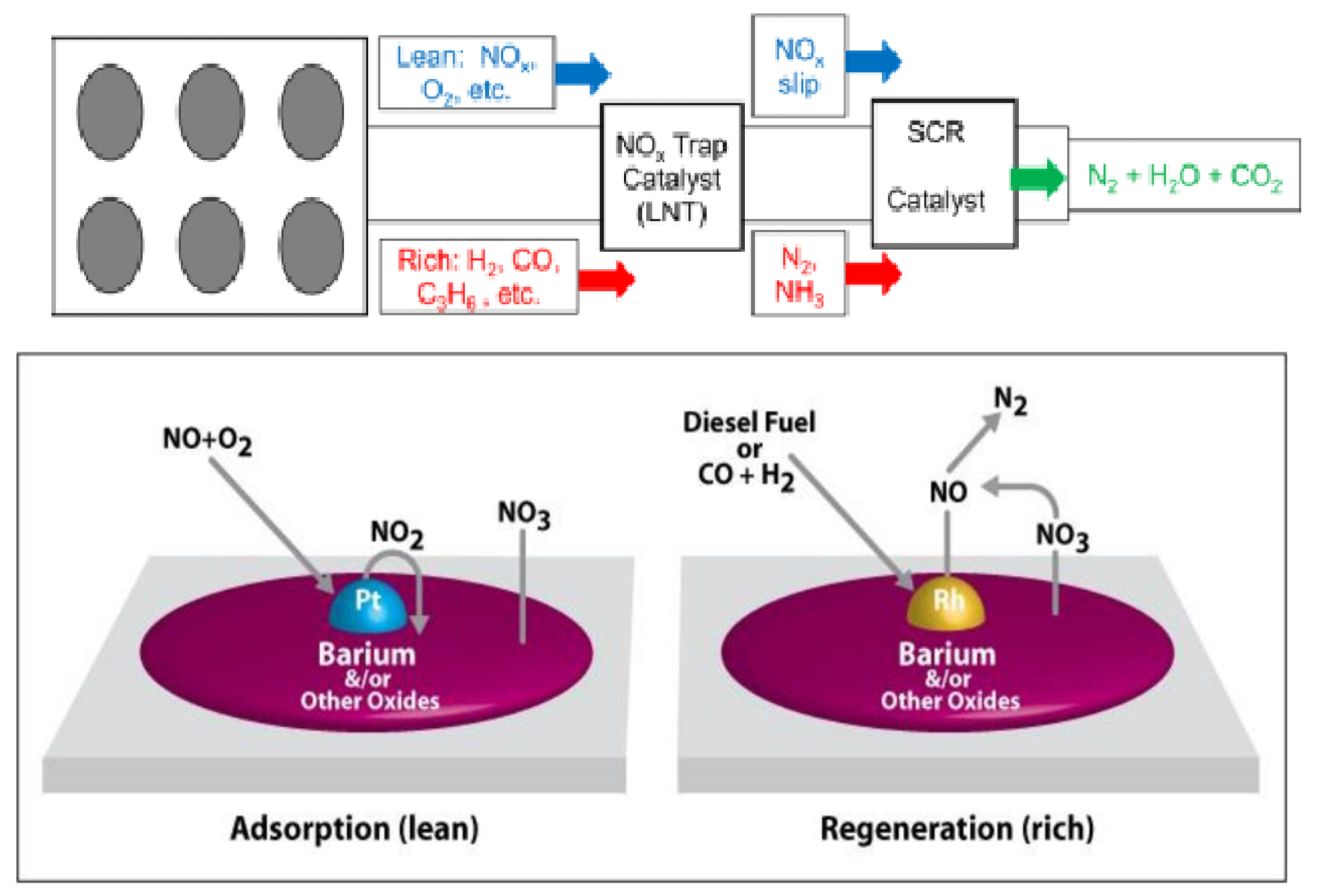

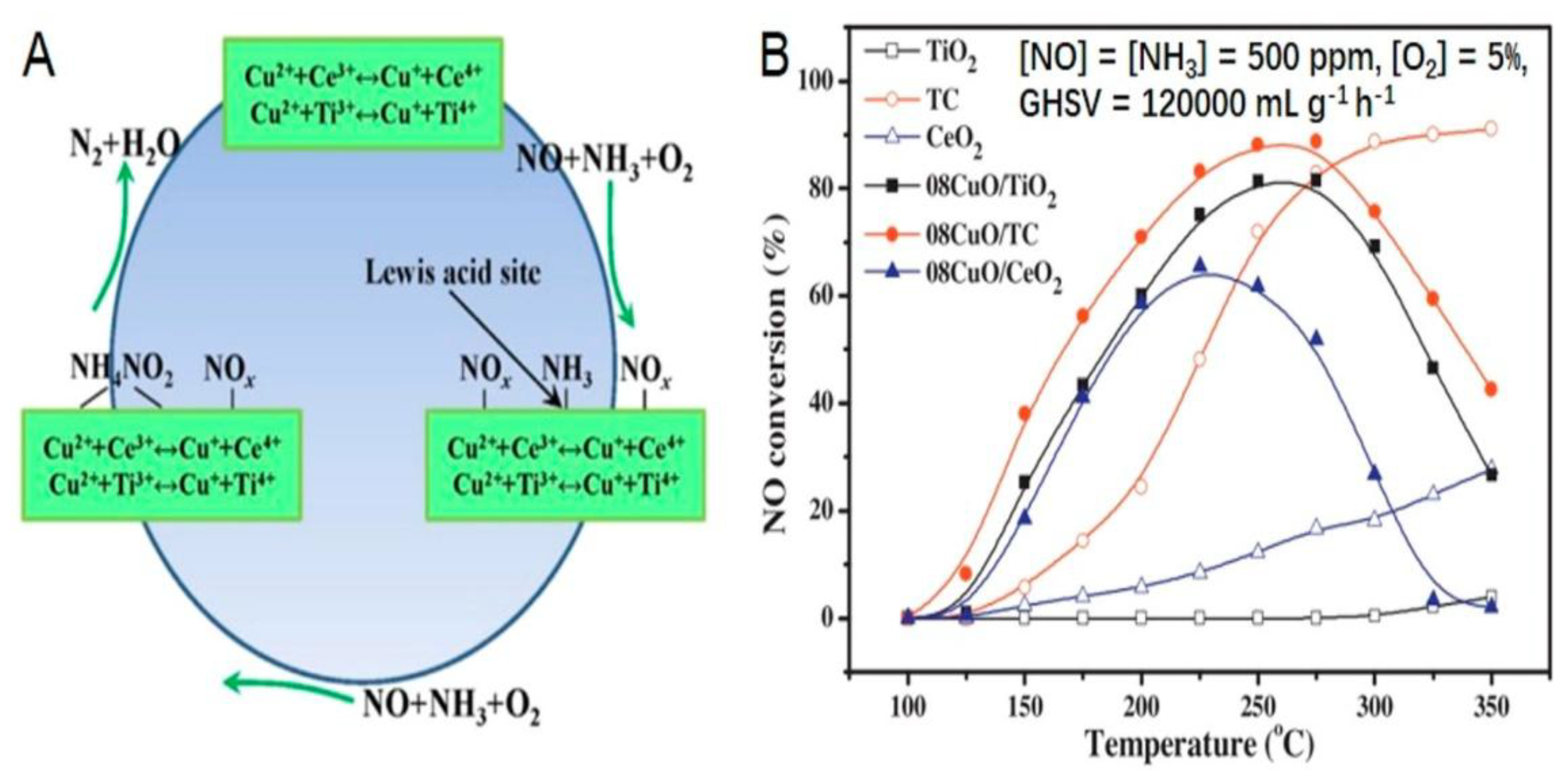

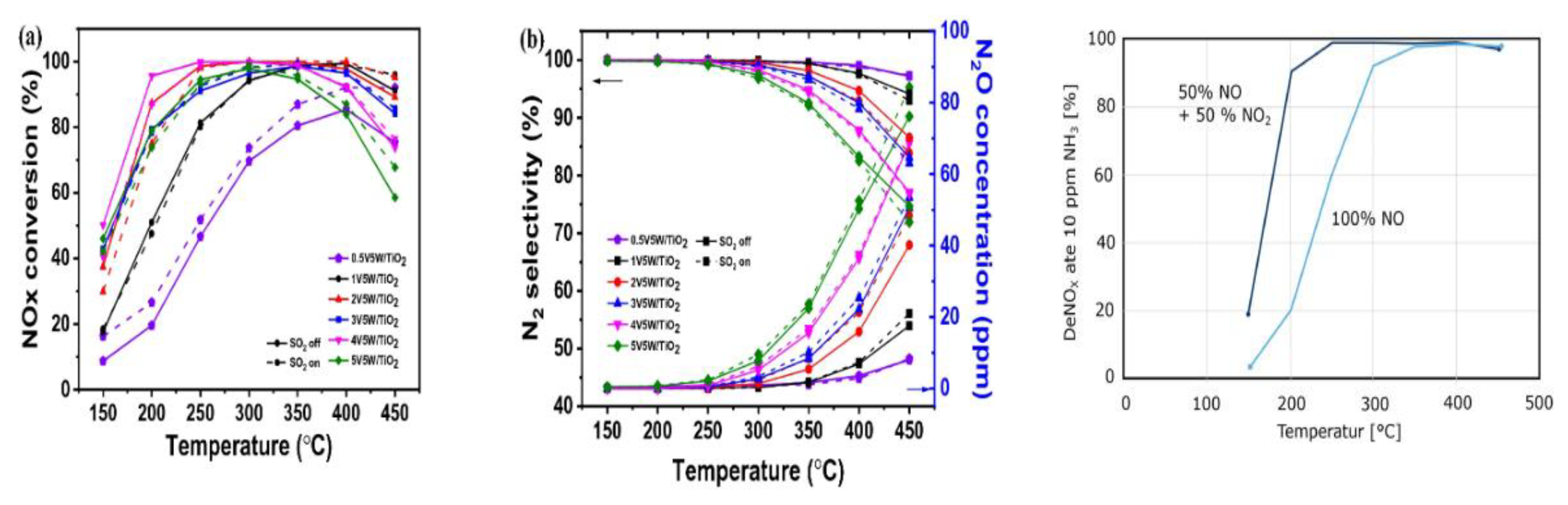

3.2. Post Treatment of NOx Emission

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. Han et al, "Combustion stability monitoring through flame imaging and stacked sparse autoencoder based deep neural network," Appl. Energy, vol. 259, pp. 114159, 2020. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030626191931846X. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Yousefi Rizi, "Stability and Safety Analysis of Ammonia Flameless Combustion as Supply Energy for Hydrogen Production.", kookmin university, Graduate School,.

- Abuelnuor et al, "Flameless combustion role in the mitigation of NOX emission: a review," Int. J. Energy Res., vol. 38, (7), pp. 827–846, 2014.

- M. Elbaz et al, "Experimental and kinetic modeling study of laminar flame speed of dimethoxymethane and ammonia blends," Energy Fuels, vol. 34, (11), pp. 14726–14740, 2020.

- S. McAllister, J. Chen and A. Fernandez-Pello, "Non-premixed flames (diffusion flames)," in Fundamentals of Combustion Processes, S. McAllister, J. Chen and A. C. Fernandez-Pello, Eds. 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Sisco et al, "Examination of mode shapes in an unstable model combustor," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 330, (1), pp. 61–74, 2011. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022460X10004724. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Flynn et al, "Thermoacoustic vibrations in industrial furnaces and boilers," in Proceedings of AFRC 2017 Industrial Combustion Symposium, 2017.

- Choi et al, "Combustion instability monitoring through deep-learning-based classification of sequential high-speed flame images," Electronics, vol. 9, (5), pp. 848, 2020.

- S. Joo et al, "A novel diagnostic method based on filter bank theory for fast and accurate detection of thermoacoustic instability," Scientific Reports, vol. 11, (1), pp. 3043, 2021.

- V. I. Biryukov, "Bases of combustion instability," in Direct Numerical Simulations-an Introduction and ApplicationsAnonymous 2020.

- Y. Nakagawa, "Experiments on the inhibition of thermal convection by a magnetic field," Proceedings of the Royal Society of London.Series A.Mathematical and Physical Sciences, vol. 240, (1220), pp. 108–113, 1957.

- A. Khateeb et al, "Stability limits and NO emissions of technically-premixed ammonia-hydrogen-nitrogen-air swirl flames," International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 45, (41), pp. 22008–22018, 2020.

- Q. Liu et al, "The characteristics of flame propagation in ammonia/oxygen mixtures," J Hazard Mater, vol. 363, pp. 187–196, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Valera-Medina et al, "Review on ammonia as a potential fuel: from synthesis to economics," Energy Fuels, vol. 35, (9), pp. 6964–7029, 2021.

- Duynslaegher, "Experimental and numerical study of ammonia combustion," University of Leuven, pp. 1–314, 2011.

- J. S. Kim, F. A. Williams and P. D. Ronney, "Diffusional-thermal instability of diffusion flames," J. Fluid Mech., vol. 327, pp. 273–301, 1996.

- Y. Li et al, "Explosion behaviors of ammonia–air mixtures," Combustion Sci. Technol., vol. 190, (10), pp. 1804–1816, 2018.

- Altantzis et al, "Hydrodynamic and thermodiffusive instability effects on the evolution of laminar planar lean premixed hydrogen flames," J. Fluid Mech., vol. 700, pp. 329–361, 2012.

- C. Kwon, G. Rozenchan and C. K. Law, "Cellular instabilities and self-acceleration of outwardly propagating spherical flames," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 29, (2), pp. 1775–1783, 2002. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1540748902802152. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al, "Laminar burning velocity and cellular instability of 2-butanone-air flames at elevated pressures," Fuel, vol. 316, pp. 123390, 2022.

- Y. Shen, K. Zhang and C. Duwig, "Investigation of wet ammonia combustion characteristics using LES with finite-rate chemistry," Fuel, vol. 311, pp. 122422, 2022.

- M. Balasubramaniyan et al, "Global hydrodynamic instability and blowoff dynamics of a bluff-body stabilized lean-premixed flame," Phys. Fluids, vol. 33, (3), pp. 034103, 2021.

- J. Morales et al, "Mechanisms of flame extinction and lean blowout of bluff body stabilized flames," Combust. Flame, vol. 203, pp. 31–45, 2019.

- N. Lipatnikov and V. A. Sabelnikov, "Karlovitz numbers and premixed turbulent combustion regimes for complex-chemistry flames," Energies, vol. 15, (16), pp. 5840, 2022.

- M. Matalon, "The Darrieus–Landau instability of premixed flames," Fluid Dyn. Res., vol. 50, (5), pp. 051412, 2018.

- P. F. HENSHAW et al, "Premixed ammonia-methane-air combustion," Combustion Sci. Technol., vol. 177, (11), pp. 2151–2170, 2005.

- Sharma and S. S. Girimaji, "Prandtl number effects on the hydrodynamic stability of compressible boundary layers: flow–thermodynamics interactions," J. Fluid Mech., vol. 948, pp. A16, 2022.

- M. A. Liberman et al, "Stability of a planar flame front in the slow-combustion regime," Physical Review E, vol. 49, (1), pp. 445, 1994.

- Laera et al, "Modelling of Thermoacoustic Combustion Instabilities Phenomena: Application to an Experimental Test Rig," Energy Procedia, vol. 45, pp. 1392–1401, 2014. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876610214001477. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Acharya, "Dynamics of Premixed Flames in Non-Axisymmetric Disturbance Fields," Dynamics of Premixed Flames in Non-Axisymmetric Disturbance Fields, 2013.

- Broatch et al, "Analysis of combustion acoustic phenomena in compression–ignition engines using large eddy simulation," Phys. Fluids, vol. 32, (8), 2020.

- Fichera and A. Pagano, "Monitoring combustion unstable dynamics by means of control charts," Appl. Energy, vol. 86, (9), pp. 1574–1581, 2009.

- Zhao, S. Ni and D. Guan, "Nonlinear thermoacoustic instability investigation on ammonia-hydrogen combustion in a longitudinal combustor with double-ring inlets," J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 149, (4), pp. A121, 2021.

- G. Searby, "Instability phenomena during flame propagation," Combustion Phenomena, 2009.

- K. Bengtsson, "ThermoacousticInstabilities in a Gas Turbine Combustor," 2017.

- T. Kobayashi et al, "Early detection of thermoacoustic combustion instability using a methodology combining complex networks and machine learning," Physical Review Applied, vol. 11, (6), pp. 064034, 2019.

- L. Zhang et al, "Neural network PID control for combustion instability," Combustion Theory and Modelling, vol. 26, (2), pp. 383–398, 2022.

- S. Morgans and A. P. Dowling, "Model-based control of combustion instabilities," J. Sound Vibrat., vol. 299, (1), pp. 261–282, 2007. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022460X06006079. [CrossRef]

- Ruan et al, "Thermoacoustic Instability Characteristics and Flame/Flow Dynamics in a Multinozzle Lean Premixed Gas Turbine Model Combustor Operated with High Carbon Number Hydrocarbon Fuels," Energy Fuels, vol. 35, (2), pp. 1701–1714, 2021.

- H. S. Awad and Y. A. Eldrainy, "Design and investigation of a central air jet flameless combustor," Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 60, (2), pp. 2291–2301, 2021. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110016820306864. [CrossRef]

- S. Veríssimo et al, "Experimental and numerical investigation of the influence of the air preheating temperature on the performance of a small-scale mild combustor," Combustion Sci. Technol., vol. 187, (11), pp. 1724–1741, 2015.

- H. A. Yousefi Rizi and D. Shin, "Development of Ammonia Combustion Technology for NOx Reduction," Energies, vol. 18, (5), pp. 1248, 2025. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/18/5/1248. [CrossRef]

- A. Imteyaz et al, "Combustion behavior and stability map of hydrogen-enriched oxy-methane premixed flames in a model gas turbine combustor," Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 43, (34), pp. 16652–16666, 2018. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360319918322419. [CrossRef]

- Locci, "Large Eddy Simulations Modelling of Flameless Combustion," Large Eddy Simulations Modelling of Flameless Combustion, 2014.

- T. B. Imhoff, S. Gkantonas and E. Mastorakos, "Analysing the Performance of Ammonia Powertrains in the Marine Environment," Energies, vol. 14, (21), pp. 7447, 2021. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/14/21/7447. [CrossRef]

- L. Qin et al, "Swirling Flameless Combustion of Pure Ammonia Fuel," Energies, vol. 18, (12), pp. 3104, 2025.

- S. Colson et al, "Extinction characteristics of ammonia/air counterflow premixed flames at various pressures," Journal of Thermal Science and Technology, vol. 11, (3), pp. JTST0048, 2016.

- H. Abdul Wahhab, "Investigation of Stability Limits of a Premixed Counter Flame," International Journal of Automotive and Mechanical Engineering, vol. 18, pp. 8540–8549, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Lee et al, "Stability and emission characteristics of ammonia-air flames in a lean-lean fuel staging tangential injection combustor," Combust. Flame, vol. 248, pp. 112593, 2023. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010218022006010. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Chiong et al, "Advancements of combustion technologies in the ammonia-fuelled engines," Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 244, (July), pp. 114460, 2021.

- K. H. Lee et al, "Stability limits of premixed microflames at elevated temperatures for portable fuel processing devices," Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 33, (1), pp. 232–239, 2008. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360319907005228. [CrossRef]

- U. Shet et al, "Stability of Premixed Tubular Burner Flame in Horizontal-Configuration with Opposing Air-Flow," .

- G. Pizza, C. E. Frouzakis and J. Mantzaras, "Chaotic dynamics in premixed hydrogen/air channel flow combustion," Combustion Theory and Modelling, vol. 16, (2), pp. 275–299, 2012.

- H. Kobayashi et al, "Science and technology of ammonia combustion," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 37, (1), pp. 109–133, January, 2019.

- M. C. Franco et al, "Characteristics of NH3/H2/air flames in a combustor fired by a swirl and bluff-body stabilized burner," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 38, (4), pp. 5129–5138, 2021.

- Goldmann, F. Dinkelacker,, " Investigation of boundary layer flashback for non-swirling premixed hydrogen/ammonia/nitrogen/oxygen/air flames," Combustion and Flame, vol. 238, pp. 111927, 2022. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010218021006702. [CrossRef]

- P. York et al, "Modeling an Ammonia SCR DeNOx Catalyst: Model Development and Validation," Modeling an Ammonia SCR DeNOx Catalyst: Model Development and Validation, 2004.

- H. Li, H. Xiao and J. Sun, "Laminar burning velocity, Markstein length, and cellular instability of spherically propagating NH3/H2/Air premixed flames at moderate pressures," Combust. Flame, vol. 241, pp. 112079, 2022. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010218022000980. [CrossRef]

- Beyler, "Flammability limits of premixed and diffusion flames," SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering, pp. 529–553, 2016.

- N. N. Shohdy, M. Alicherif and D. A. Lacoste, "Transfer Functions of Ammonia and Partly Cracked Ammonia Swirl Flames," Energies, vol. 16, (3), pp. 1323, 2023.

- Y. Xiao, Z. Cao and C. Wang, "Flame stability limits of premixed low-swirl combustion," Advances in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 10, (9), pp. 1687814018790878, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Bompelly, "LEAN BLOWOUT AND ITS ROBUST SENSING IN SWIRL COMBUSTORS," Lean Blowout and its Robust Sensing in Swirl Combustors, 2013.

- Jacqueline O’Connor, "Recirculation zone dynamics of a transversely excited swirl flow and flame: Physics of Fluids: Vol 24, No 7," Available: https://aip.scitation.org/doi/full/10.1063/1.4731300?ver=pdfcov.

- L. Srinivasan, "ANALYSIS OF FLAME BLOWOUT IN TURBULENT PREMIXED AMMONIA/HYDROGEN/NITROGEN-AIR COMBUSTION," Analysis of Flame Blow-Out in Turbulent Premixed Ammonia/Hydrogen/Nitrogen-Air Combustion, 2022.

- E. Cavaliere, J. Kariuki and E. Mastorakos, "A comparison of the blow-off behaviour of swirl-stabilized premixed, non-premixed and spray flames," Flow, Turbulence and Combustion, vol. 91, pp. 347–372, 2013.

- M. Elbaz et al, "An experimental/numerical investigation of the role of the quarl in enhancing the blowout limits of swirl-stabilized turbulent non-premixed flames," Fuel, vol. 236, pp. 1226–1242, 2019. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016236118316016. [CrossRef]

- Feikema, R. Chen and J. F. Driscoll, "Enhancement of flame blowout limits by the use of swirl," Combust. Flame, vol. 80, (2), pp. 183–195, 1990.

- J. F. Driscoll and C. C. Rasmussen, "Correlation and analysis of blowout limits of flames in high-speed airflows," J. Propul. Power, vol. 21, (6), pp. 1035–1044, 2005.

- Li and M. Ihme, "Stability diagram and blow-out mechanisms of turbulent non-premixed combustion," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 38, (4), pp. 6337–6344, 2021. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1540748920303175. [CrossRef]

- S. Colson et al, "Extinction characteristics of ammonia/air counterflow premixed flames at various pressures," Journal of Thermal Science and Technology, vol. 11, pp. JTST0048–JTST0048, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Shanbhogue et al, "Flame macrostructures, combustion instability and extinction strain scaling in swirl-stabilized premixed CH4/H2 combustion," Combust. Flame, vol. 163, pp. 494–507, 2016. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S001021801500382X. [CrossRef]

- V. Vrabie, D. Scarpete and O. Zbarcea, "The new exhaust aftertreatment system for reducing nox emissions OF diesel engines: Lean nox trap (LNT). A study," Trans Motauto World, vol. 1, (4), pp. 35–38, 2016.

- Wang et al, "MILD combustion versus conventional bluff-body flame of a premixed CH4/air jet in hot coflow," Energy, vol. 187, pp. 115934, 2019.

- W. Jiang, R. Zhu and D. Shin, "Heat transfer characteristics of tubular heat exchanger using reverse air injection flameless combustion," Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 230, pp. 120713, 2023. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359431123007421. [CrossRef]

- I. Lemcherfi et al, "Investigation of combustion instabilities in a full flow staged combustion model rocket combustor," in AIAA Propulsion and Energy 2019 Forum, 2019.

- Anonymous "Design and investigation of a central air jet flameless combustor - ScienceDirect," Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110016820306864.

- W. I. David et al, "2023 roadmap on ammonia as a carbon-free fuel," Journal of Physics: Energy, vol. 6, (2), pp. 021501, 2024.

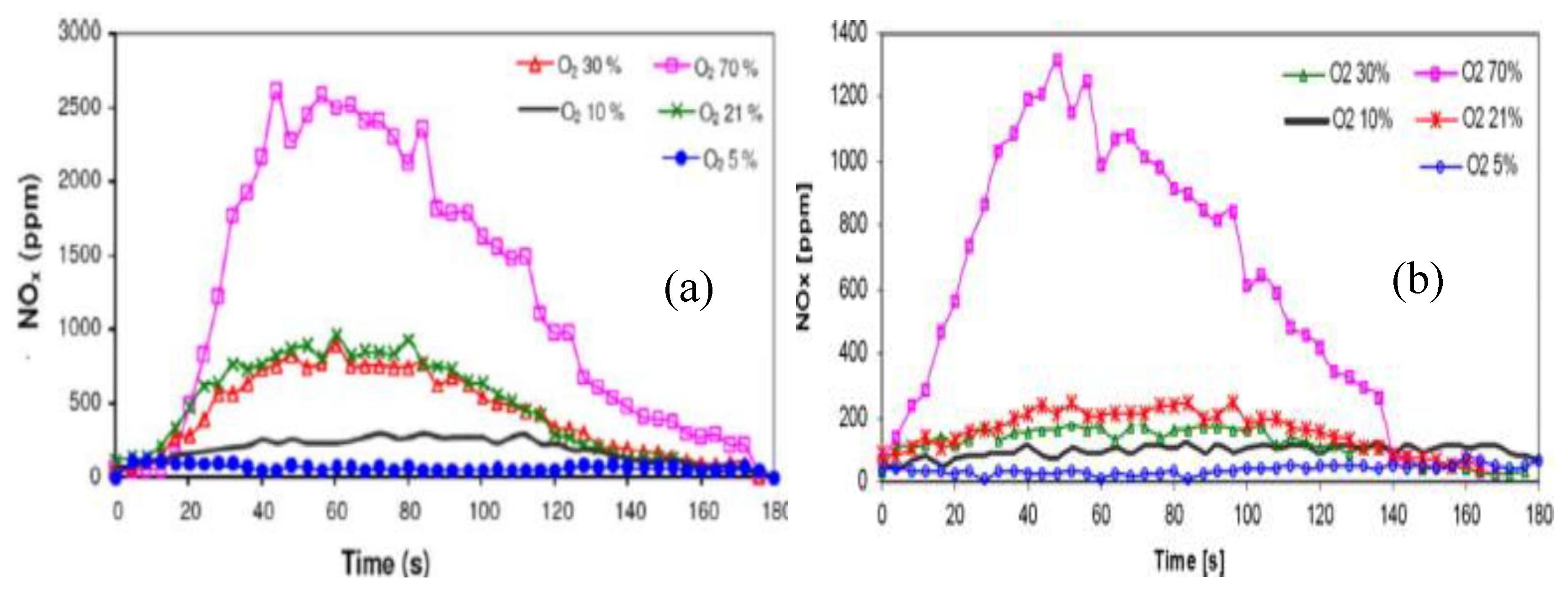

- K. Kim et al, "Effects of O2 enrichment on NH3/air flame propagation and emissions," Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 46, (46), pp. 23916–23926, 2021.

- M. Elbaz et al, "Review on the recent advances on ammonia combustion from the fundamentals to the applications," Fuel Communications, vol. 10, pp. 100053, 2022.

- Wang et al, "Measurement of oxy-ammonia laminar burning velocity at normal and elevated temperatures," Fuel, vol. 279, pp. 118425, 2020.

- Kurata et al, "Performances and emission characteristics of NH3-air and NH3-CH4-air combustion gas-turbine power generations," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 36, (3), pp. 3351–3359, 2017.

- Tang, D. Ezendeeva and G. Magnotti, "Simultaneous measurements of NH2 and major species and temperature with a novel excitation scheme in ammonia combustion at atmospheric pressure," Combust. Flame, vol. 250, pp. 112639, 2023. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S001021802300024X. [CrossRef]

- Bian, J. Vandooren and P. J. Van Tiggelen, "Experimental study of the structure of an ammonia-oxygen flame," Symposium (International) on Combustion, vol. 21, (1), pp. 953–963, 1988.

- M. Joo, S. Lee and O. C. Kwon, "Effects of ammonia substitution on combustion stability limits and NOx emissions of premixed hydrogen–air flames," International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 37, (8), pp. 6933–6941, 2012.

- N. Salmon and R. Bañares-Alcántara, "Green ammonia as a spatial energy vector: a review," Sustainable Energy & Fuels, vol. 5, (11), pp. 2814–2839, 2021. Available: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2021/se/d1se00345c. [CrossRef]

- S. Yuasa, "Effects of swirl on the stability of jet diffusion flames," Combust. Flame, vol. 66, (2), pp. 181–192, 1986. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0010218086900908. [CrossRef]

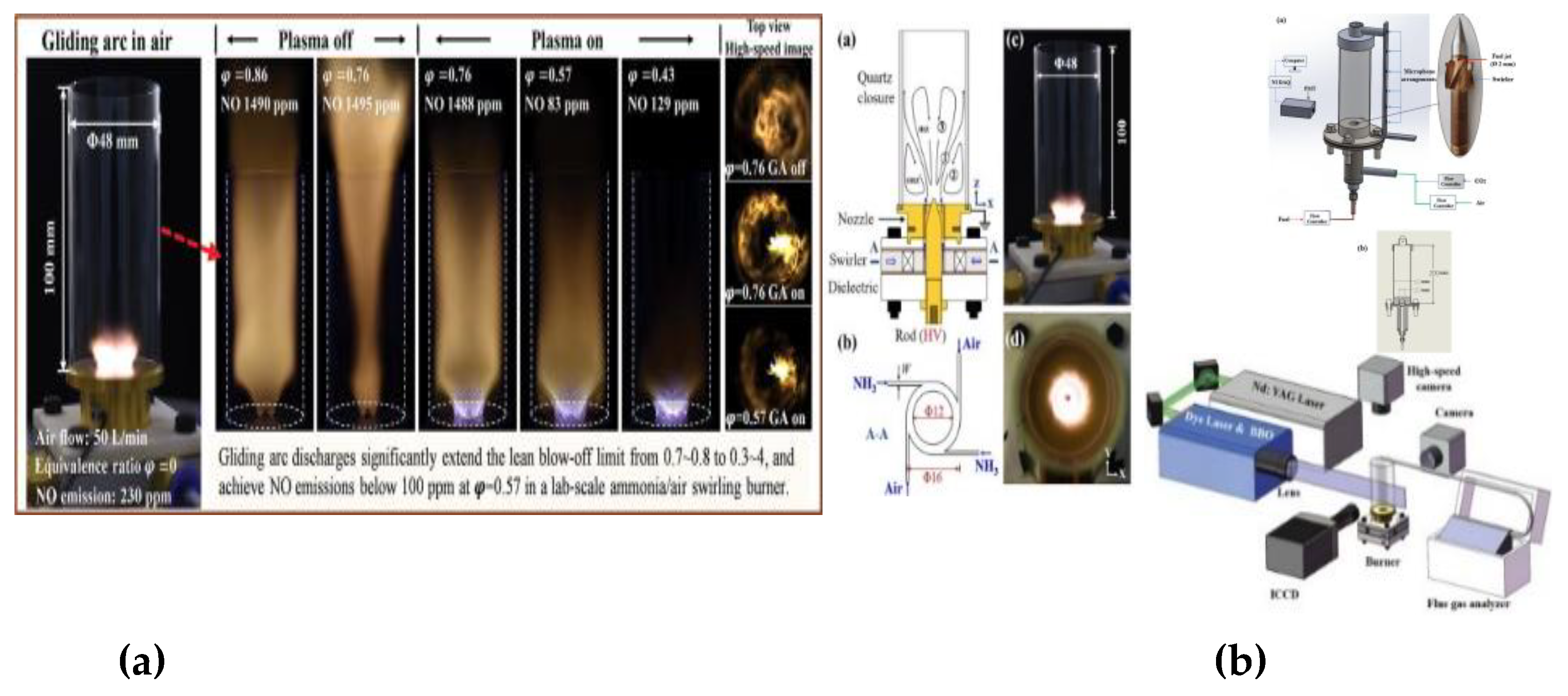

- Y. Tang et al, "Flammability enhancement of swirling ammonia/air combustion using AC powered gliding arc discharges," Fuel, vol. 313, pp. 122674, 2022. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016236121025400. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Abuelnuor et al, "Characteristics of biomass in flameless combustion: A review," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 33, pp. 363–370, 2014. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032114001014. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhu and D. Shin, "Study on Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of 25 kW Flameless Combustion in a Cylindrical Heat Exchanger for a Reforming Processor," Energies, vol. 16, (20), pp. 7160, 2023. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/16/20/7160. [CrossRef]

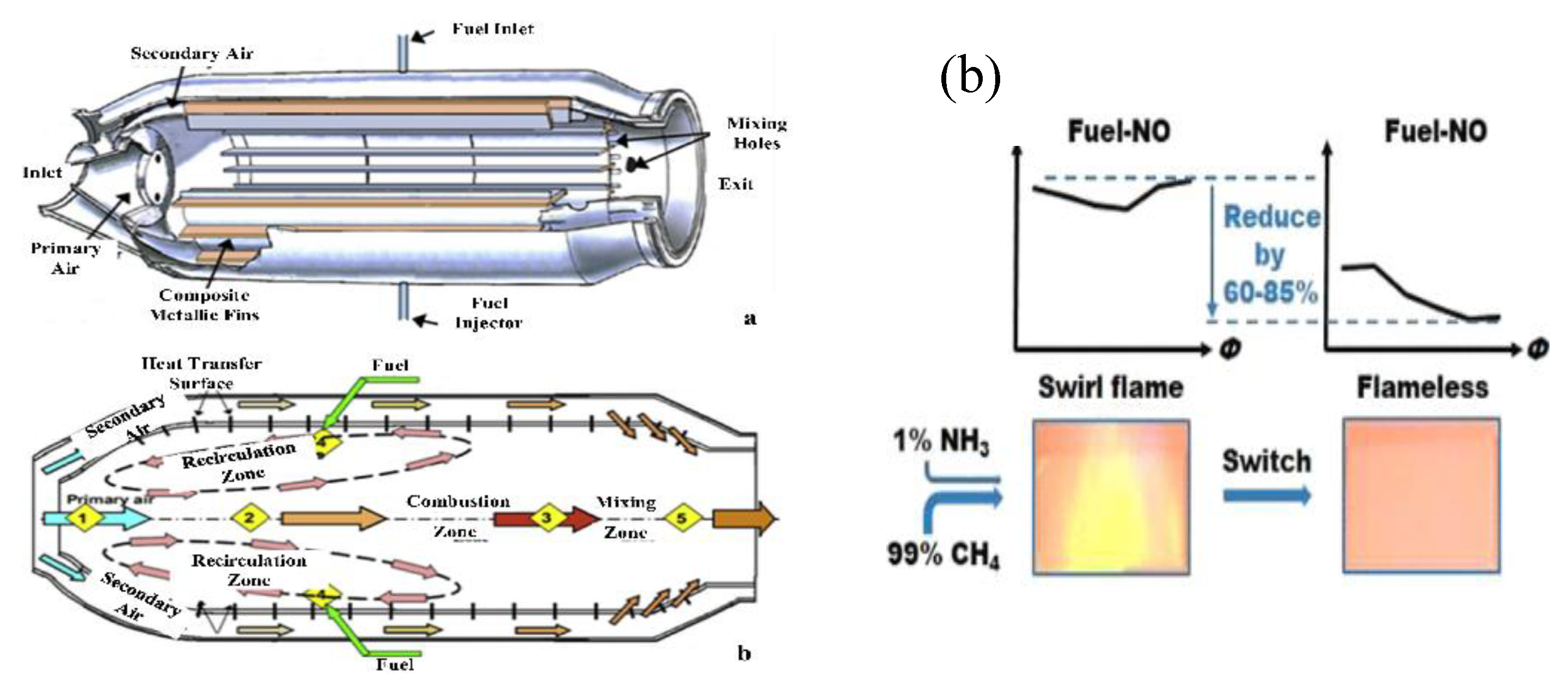

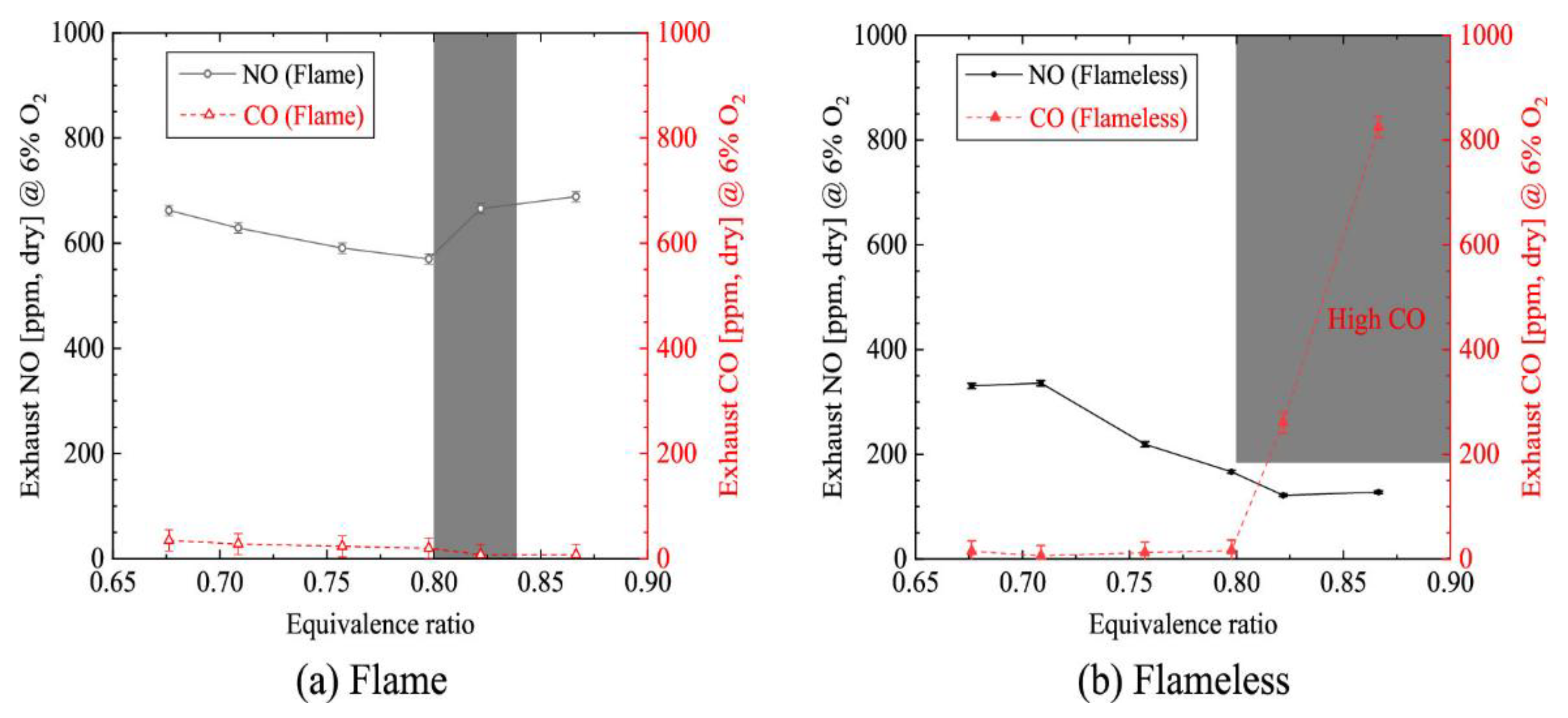

- Ding et al, "Comparative Study between Flameless Combustion and Swirl Flame Combustion Using Low Preheating Temperature Air for Homogeneous Fuel NO Reduction," Energy Fuels, vol. 35, (9), pp. 8181–8193, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Sorrentino et al, "Low-NOx conversion of pure ammonia in a cyclonic burner under locally diluted and preheated conditions," Applied Energy, vol. 254, November, 2019.

- Locci, O. Colin and J. Michel, "Large Eddy Simulations of a Small-Scale Flameless Combustor by Means of Diluted Homogeneous Reactors," Flow Turbulence Combust, vol. 93, (2), pp. 305–347, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Ansari et al, "A new low NOx emission technique for NH3/H2 blends in a flameless combustor through offset injection," Journal of the Energy Institute, vol. 117, pp. 101864, 2024.

- Bo Geun Kim* and Donghoon Shin, "Study on Thermal Flow Characteristics of Flameless Combustion Furnace with Coaxial Dual Tube Heat Ex-changer by Reversed Air Injection Method," Rans. Korean Soc. Mech. Eng. B, Vol. 44, no. 4, Pp. 219~230, 2020, vol. 44, 2020. Available: https://www.dbpia.co.kr.

- C. S. Svith et al, "An experimental and modelling study of the Selective Non-Catalytic Reduction (SNCR) of NOx and NH3 in a cyclone reactor," Chem. Eng. Res. Design, vol. 183, pp. 331–344, 2022.

- Han et al, "Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 by Using Novel Catalysts: State of the Art and Future Prospects," Chem. Rev., vol. 119, (19), pp. 10916–10976, 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Ye et al, "Recent trends in vanadium-based SCR catalysts for NOx reduction in industrial applications: stationary sources," Nano Converg, vol. 9, (1), pp. 51, 2022. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36401645/. [CrossRef]

- Maizak, T. Wilberforce and A. G. Olabi, "DeNOx removal techniques for automotive applications – A review," Environmental Advances, vol. 2, pp. 100021, 2020. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666765720300211. [CrossRef]

| Factor | Effect on Flame Stability | Effect on NOx Emissions |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen addition (10–40%) | Widens stability, increases flame speed | Moderate NO increase at lean; reduction at rich |

| Pressure (5–15 atm) | Improves stability and completeness | Reduces NOx by up to 40% |

| Rich operation (ϕ > 1.1) | Reduces stability slightly | Decreases fuel-NO via NHx radicals |

| Swirl/tangential staging | Enhances stability | Reduces NOx to ~50% with proper flow staging |

| Plasma-assisted combustion | Significantly extends lean limit | 20–40% NOx reduction |

| Heat-recirculating (Swiss-roll) | Broadens stable regime of pure NH₃ | Non-monotonic NO vs ϕ, lower at lean/rich |

| Flameless combustion | Broadens stable regime of pure NH₃, in high temperature | More than 40% NOx reduction |

| Design Criteria | SNCR | SCR |

|---|---|---|

| NOx reduction efficiency | 40-75% | 60-90% |

| Temperature window | 870°-1200°C | 165°-600°C |

| Reactant | Ammonia or Urea | Ammonia or Urea |

| Reactor | None | Catalytic |

| Waste disposal | None | Spent catalyst |

| Thermal efficiency debit | 0 – 0.3% | 0% |

| Energy consumption | Low | *High I.D. fan |

| Capital investment costs | Low | High |

| Plot requirements | Minor | Major |

| Maintenance | Low | 3 – 5 years (typical catalyst life) |

| Ammonia/NOx (molar ratio) | 1.0 – 1.5 | 0.8 – 1.2 |

| Urea/NOx (molar ratio) | 0.5 – 0.75 | Not Applicable |

| Ammonia slip | 5 – 20 **ppmvd | 5 -10 ppmvd |

| Retrofit | Easy | Difficult |

| Mechanical draft | Not Required | Required |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).