1. Introduction

Bedload in sediment-laden rivers often leads to deposits at intake structures, resulting in reduced operational efficiency and increased maintenance demands [

1]. In run-of-river hydropower plants, where flow depths are relatively shallow, gradual bedload accumulations can elevate both the riverbed and water levels, thereby compromising flood protection [

2]. Excessive sediment deposition near turbine intakes, upstream or downstream of weirs, or around water intake structures can obstruct flow, reducing operational efficiency and limiting energy production [

3]. If not properly managed, bedload accumulation not only increases maintenance requirements but also disrupts downstream sediment continuity, leading to riverbed erosion, coarsening of substrates and ecological degradation [

4]. Other studies [

5,

6] also show that sediment deficiency - for example, as a result of bedload retentions at water intake structures leads to habitat degradation, lower biodiversity, and a decline in ecosystem complexity. These challenges underscore the urgent need for effective bedload control and management strategies in rivers, especially at intake structures. In this context, the use of oblique underflow baffles emerges as a promising and innovative method for selectively guiding and managing bedload transport.

Underflow baffles — also referred to as baffle walls, scum baffles, or scum boards — are surface-mounted hydraulic structures that are placed across the channel, are partially submerged, and allow flow beneath them. They are traditionally used to retain floating materials or substances with lower density than water, such as wood, oils, greases, fuels, and debris. The flow characteristics of underflow baffles positioned orthogonal to the flow direction have extensively been investigated in previous research [

7,

8,

9] leading to a comprehensive understanding of their function in conventional applications. Recent observations by Kostić and Rüther [

10] reveal that installing oblique, rather than orthogonal, underflow baffles generates a three-dimensional (3D) vortex structure conveyed downstream. At sufficiently high flow rates, this helical vortex structure can redirect the bedload, resulting in a bedload-free zone within the channel. Its discovery opens up new possibilities for the application of underflow baffles beyond their conventional uses.

Flow beneath sluice gates and other deeply submerged underpass structures has been widely studied, particularly with regard to local scour around gates installed orthogonal to the channel [

11,

12]. Only a few studies [

13,

14,

15,

16] have investigated the effects of oblique (skewed or angled) sluice gates, and these focused primarily on discharge characteristics rather than on bedload transport.

In hydraulic engineering practice, bedload deflection in channels and rivers is typically achieved using structures positioned near the riverbed. One of the most widely applied methods is the use of groynes, which have been extensively studied and documented [

1,

17,

18]. Similarly, guide walls installed close to the bed have proven effective in redirecting bedload [

19,

20]. Another established technique involves the use of Iowa vanes, first introduced by Odgaard and Kennedy [

21]. Their effectiveness has been further explored in subsequent studies [

22,

23,

24]. Underflow baffles may represent a novel alternative or supplement to existing near-bed structures used for bedload deflection.

Considering the above-discussed knowledge gaps and further research needs, a thorough investigation on the influence of oblique underflow baffles on flow dynamics and bedload transport using a hybrid numerical–experimental approach has been initiated. The research is being carried out in controlled, rectangular open-channel flume conditions, enabling the isolated analysis of the oblique baffle’s effect on bedload transport through a series of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations. Subsequently, physical model experiments will be performed in order to validate and further expand the CFD findings. The initial investigations on underflow baffles presented in this paper were carried out only as an initial CFD investigation with the aim of assessing the feasibility and potential of this research, as CFD provides a cost-effective approach for exploring these processes prior to investing them using the more expensive physical model studies.

2. Study Methodology

Sediment transport can occur either as bedload or suspension, depending on the prevailing hydrodynamic conditions and various sediment properties. Bedload is the fraction of sediment that largely slides, rolls, and bounces along the riverbed. It can be estimated using a variety of transport formulas, most of which are empirical and developed for specific material properties and flow characteristics, leading to limited usability of these equations [

25]. Since the sediment transport in this study occurred predominantly as bedload, this chapter focuses on explaining the bedload transport processes as modeled in the commercial software FLOW-3D, version 2024R1 [

26], used in this study. FLOW-3D employs a structured finite volume method on a Cartesian grid to discretize the fluid flow equations and uses the volume of fluid method to simulate the air-water interface [

26]. The flow characteristics were simulated by closing the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations using the Re-Normalization Group (RNG) k-ε turbulence model [

27], where

k = turbulent kinetic energy and

ε = dissipation rate of

k. Despite its limitations, the RANS approach has proven effective in simulating bedload transport and scour around various hydraulic structures [

12,

28,

29]. The local bed shear stress, governing the bed load transport, was obtained from the simulated flow using the logarithmic law approach [

26]. The fundamental principles of bedload transport modeling in FLOW-3D are briefly outlined next.

In the used version of FLOW-3D, it is possible to choose one of the available bedload transport models that are based on Meyer-Peter & Müller [

30], Van Rijn [

31], and Nielsen [

32]. The simulations performed in this investigation were conducted with the bedload transport model based on Nielsen [

32]. This method has been found effective for simulating bedload transport over a non-erodible bed for various mesh sizes Kostić et al. [

33], and can be formulated as follows:

where,

βNie,i is a coefficient typically equal to 0.053 [

26],

cb,i is the volume fraction of sediment specie

i in the bed material to which a dimensional grain diameter

di [m] and a dimensionless grain size

d*,i are to be assigned.

ρi represents the density of the sediment specie

i,

ρf the density of the water,

g is the gravitational constant and

τ the bed shear stress which is calculated using the law of the wall and the quadratic law of bottom shear stress for 3D turbulent flow with consideration of bed surface roughness [

26]. The formulae related to the Nielsen’s approach were originally developed for bedload transport in coastal conditions. Nielsen [

32] studied bedload movement over a rough, moving bed with riffles by generating uniform waves in a physical model experiment. However, this approach has been found effective in modeling river and channel hydrodynamics [

29,

33,

35].

With the solved equation (1), the volumetric bedload transport rate can be calculated in units of volume per unit width of the bed per unit time. The other equation needed is to obtain the bedload thickness, i.e., the thickness of the saltating sediment which can be calculated according to Van Rijn [

31]. To compute the motion of the bedload in each computational cell, the value of volumetric bedload transport is converted into the bedload velocity.

Where

fb is the critical packing fraction of the sediment. The bedload velocity is assumed to be in the same direction as that of the fluid flow adjacent to the packed bed interface. Using the calculated volumetric bedload transport, an Exner equation can be derived by applying the sediment mass conservation and by calculating the bed elevation (

zb) over time (

t) in

x and

y direction [

36,

37]:

The initial bed is immobile solid. When the added bedload deposits on the bed, they are also considered as immobile solid with no flow equations solved in the computational cells filled entirely with the deposited sediments. The cells partially filled with bedload are reduced by the corresponding solid volume. With the use of bedload transport equations in FLOW-3D, volume fractions describing the packed sediments are calculated for each time step [

39], causing a two-way interaction between the fluid flow and bedload behavior. Additionally, the entrainment of sediments from bedload to suspension is calculated by the formula of Mastbergen and van der Berg [

40]. However, only a small amount of sediment was transported as suspension (less than 0.5%) in the presented simulations. Therefore, the formula for lifting and settling of suspension, as well as the formula for suspended sediment transport are not being further discussed herein.

3. Model Set Up

This study presents observations from eight CFD simulations listed in

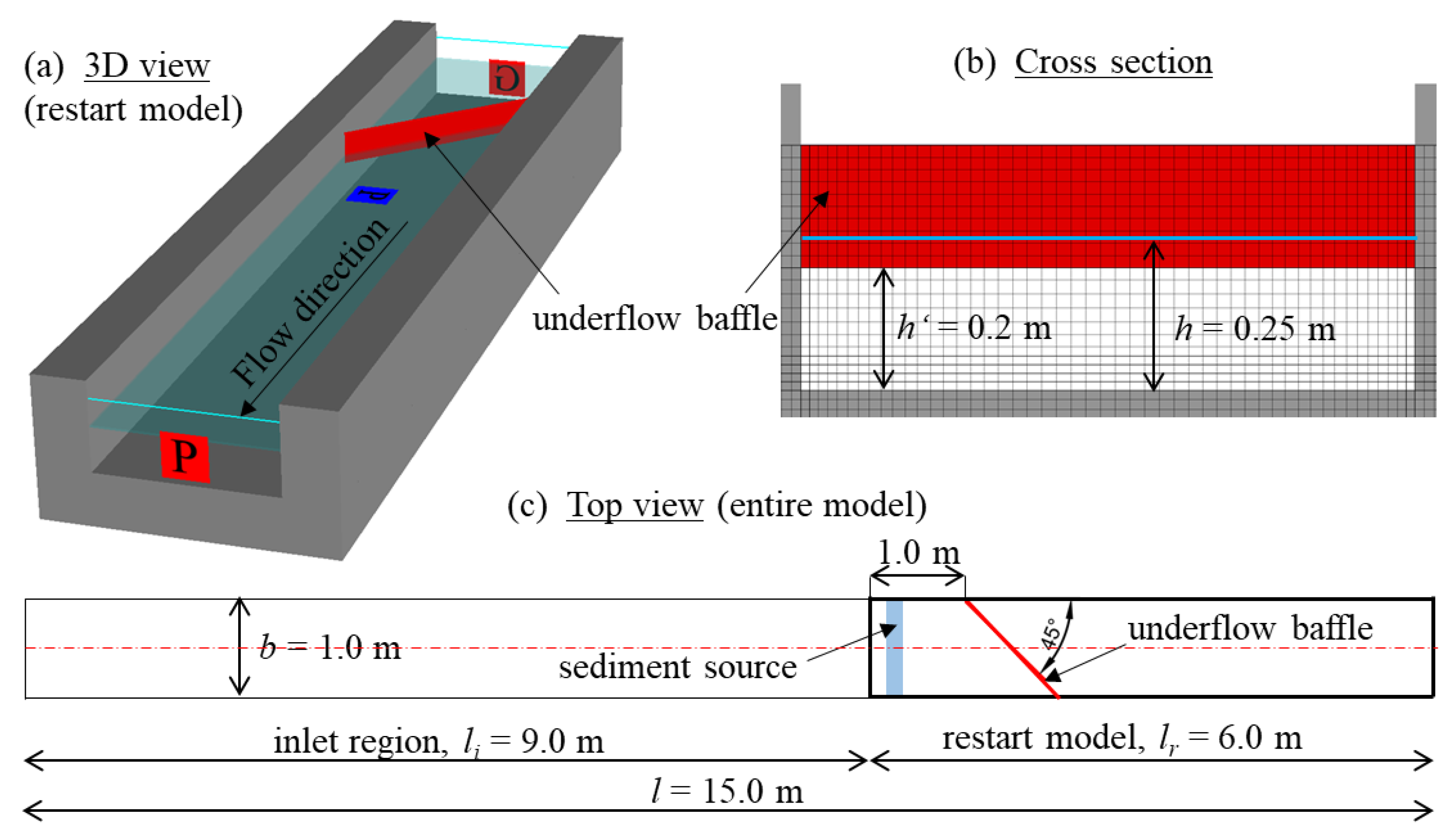

Table 1. Seven of these simulations used a constant baffle angle of 45° (non-orthogonal) while varying the channel width coverage (25%, 50%, and 100%) under a fixed channel width of 1 meter. For these cases, the discharge was varied only in the simulations with full-width baffle coverage. One additional simulation was conducted using an orthogonal (90°) baffle. In all simulations, the baffle submergence was kept constant at 20% of the flow depth (measured downward from the free surface), and a fixed bed condition was applied, with bedload introduced near the inlet. The numerical model consists of a rectangular channel with a horizontal bed, a total length of

l = 15.0 m and a width of

b = 1.0 m with an oblique underflow baffle positioned 10 m downstream of the model inlet (

Figure 1), which is 40 times the flow depth

h = 0.25m, ensuring a fully developed flow. The flow depth was controlled in the model with the boundary condition set at both the inlet and the outlet. At the inlet, the discharge and the water level are prescribed, while in the outlet region only the pressure (i.e., water level) is prescribed. The water level throughout the channel is generally uniform, as defined by the boundary conditions, with minor undulations occurring in the vicinity of the underflow baffle. Simulations under five different discharges,

Q = 0.15 m

3/s, 0.175 m

3/s, 0.20 m

3/s, 0.225 m

3/s and 0.25 m

3/s, were investigated in this study. The amount of sediment added into the models was identical for all cases. Most simulations were run for 30 minutes, except cases 1 and 2 (see

Table 1) for

Q = 0.15 m

3/s which were extended up to 45 minutes because majority of the bedload reached only up to the channel midway after 30 minutes for these cases. In these prolonged cases, the sediment was added during the first 30 minutes of the simulations, with no additional sediment input during the remaining 15 minutes. All cases investigated in this research are presented in

Table 1. For each case, a purely hydrodynamic simulation (i.e., without sediment transport) was run for the first 80 seconds, which was sufficient to achieve the steady state. Once steady state conditions were achieved, a restart simulation was performed for the downstream 6.0 m long portion of the channel, with inclusion of sediment transport. The upstream 9.0 m (inlet region) was excluded from the sediment simulations, as its sole purpose was to establish a fully developed flow before sediment inclusion.

Figure 1(a–c) present a 3D view of the restart model, a cross-sectional view, and a top view of the full channel layout, respectively.

The bottom of the underflow baffle was positioned 0.2 m above the channel bed (

h’ in

Figure 1b), with the baffle submergence of 0.05 m into the water, which is 20% of

h. In this research, only the 20% blockage of the channel cross section was investigated. However, different submergence levels of the underflow baffle are planned to be investigated in the future. The baffle was aligned to the flow at an angle of 45° to the channel axis and was spanned over the whole channel width (which varied for cases 7 and 8, as provided in

Table 1). The underflow baffle was defined in the domain using a special feature in FLOW-3D, referred to as “baffles” (distinct from the geometric baffles discussed in this paper). These baffles are planes that can block computational cells but are not part of the geometry itself, ensuring no additional computational time is required. The use of baffle elements in FLOW-3D has proven effective for simulating simple geometries in three-dimensional CFD models of bedload transport, as validated previously by Kostić et al. [

33].

The channel bed was defined as a solid, non-erodible material as discussed earlier, and the sediment was injected into the model near the inlet boundary of the restart model as a continuous sediment source throughout the simulation. This sediment source was positioned 0.05 m above the bed and 0.1 m downstream from the inlet of the restart model and was spanning across the full width of the channel. Since FLOW-3D allows suspended sediment to be introduced only via a sediment source, and since the primary interest was the bedload transport, the sediment source was positioned close to the channel bottom to promote rapid settling. In all simulations, the injected sediment settled quickly and was subsequently transported as bedload throughout the channel. A sediment with a density of ρ = 2650 kg/m3 was selected, representing silica sand. The grain size used in the simulation was uniform, with size d = 0.002 m. Each second, 0.175 kg of sediment was introduced into the model, totaling 315 kg of sediment added over a 30-minute simulation period.

4. Results

4.1. General Flow Characteristics, Mixing Among Flow Layers, and Vortex Formation

The flow characteristics results obtained from the numerical simulations with the oblique vertical underflow baffle are presented for steady-state conditions. A comparison is also made with the flow fields obtained for a case with the orthogonal baffle.

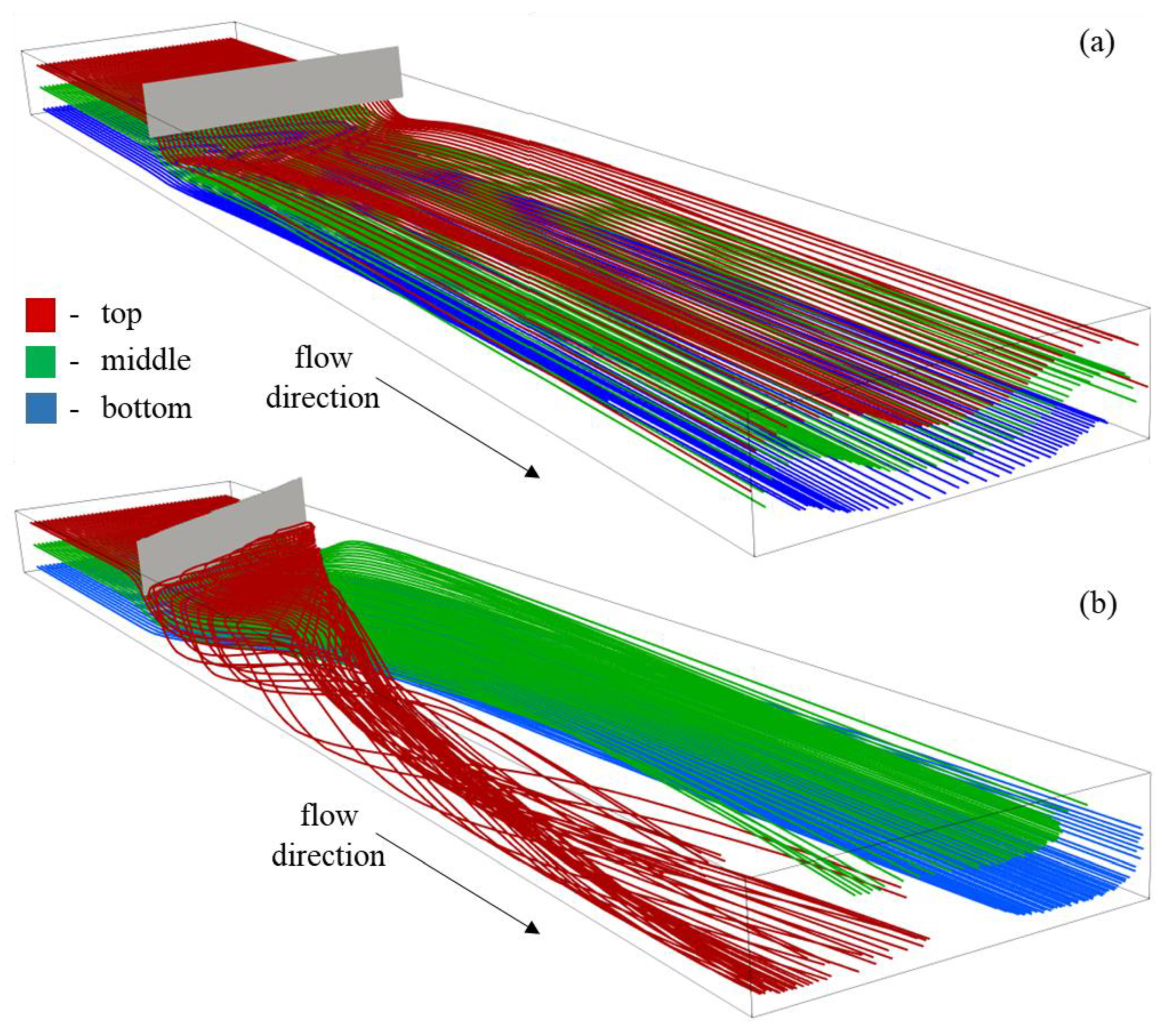

Figure 2 compares the streamlines originating from three elevations upstream of the baffle obtained for both oblique and orthogonal baffle models with a constant

Q = 0.15 m

3/s. In total, fifty streamlines originating at the inlet from three different elevations in the channel: 0.025 m above the bed (near the bed, colored blue), 0.125 m above the bed (middle of the flow depth, colored green), and 0.225 m above the bed (near the free surface, colored red) were considered in this analysis. The results indicate that the streamlines originating near the surface form a vortex downstream of the oblique baffle, while those originating near the bottom and middle regions flow mostly around this vortex as shown in

Figure 2(b). Near-bed incoming streamlines exhibit an L-shaped trajectory in the downstream region, whereas the mid-depth incoming streamlines tend to shift toward the channel center. Both near-bed and mid-depth incoming streamlines are deflected upward and toward the left side of the channel due to the non-orthogonality of the baffle, although they remain generally parallel to the bed. In contrast, near-surface incoming streamlines are pushed downward and toward the right side of the channel. This interaction leads to significant mixing between flow layers, a phenomenon not observed in the orthogonal baffle case shown in

Figure 2(a). For the orthogonal baffle, the streamlines largely retain their lateral and vertical positions, except in the immediate vicinity of the baffle, where they are vertically deflected due to partial blockage near the free surface. Additionally, the mid-depth and near-surface incoming streamlines form an M-shaped pattern downstream, while the near-bed streamlines incoming (blue) appear more elevated in the near-wall region.

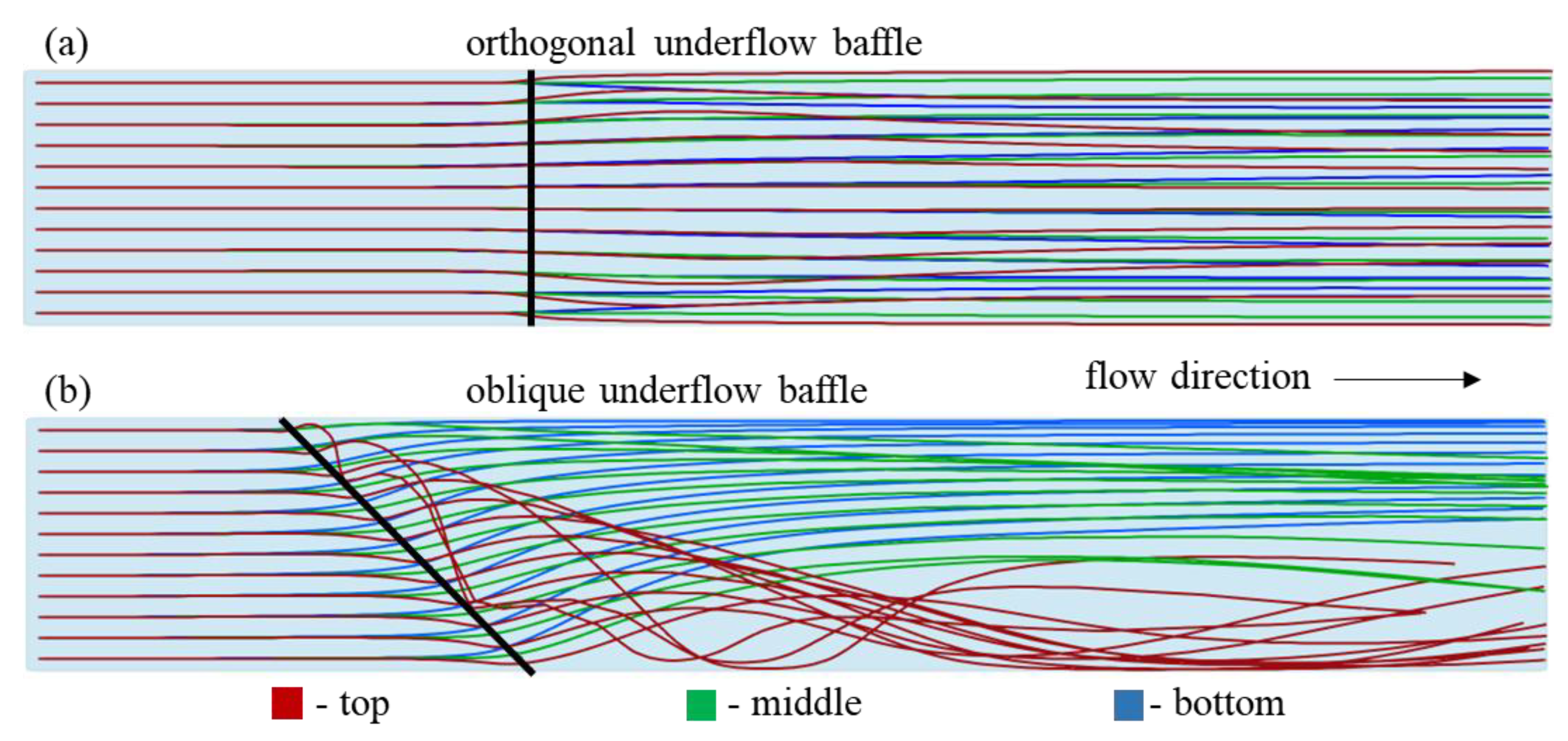

In addition to the 3D view of the streamlines,

Figure 3 provides a comparison between the lateral variations in twelve streamlines (originating from the same three elevations discussed in

Figure 2) observed for the orthogonal and the oblique baffle case for

Q = 0.15 m

3/s. The plan view of the streamlines shown in

Figure 3 highlights the effects of flow beneath the oblique baffle more clearly than the 3D view.

Figure 3 illustrates that although the incoming streamlines upstream of the baffle are parallel to the sidewalls, their paths alter in the vicinity and downstream of the baffle, primarily for the oblique baffle case. In the case of orthogonal baffle, the near-surface incoming streamlines are slightly pushed toward the sidewalls while the near-bed incoming streamlines are slightly pushed inward, downstream of the baffle. However, the mid-depth incoming streamlines remain mostly parallel. In contrast, significant alternations in the streamlines are observed downstream of the oblique baffle, as the near-surface incoming streamlines consistently shift toward the right side of the channel and the near-bed and mid-depth incoming streamlines shift toward the left side of the channel, highlighting the formation of a vortex moving downstream. The above-discussed observed alternations in the streamlines and formation of downstream vortex are expected to influence the bedload transport considerably.

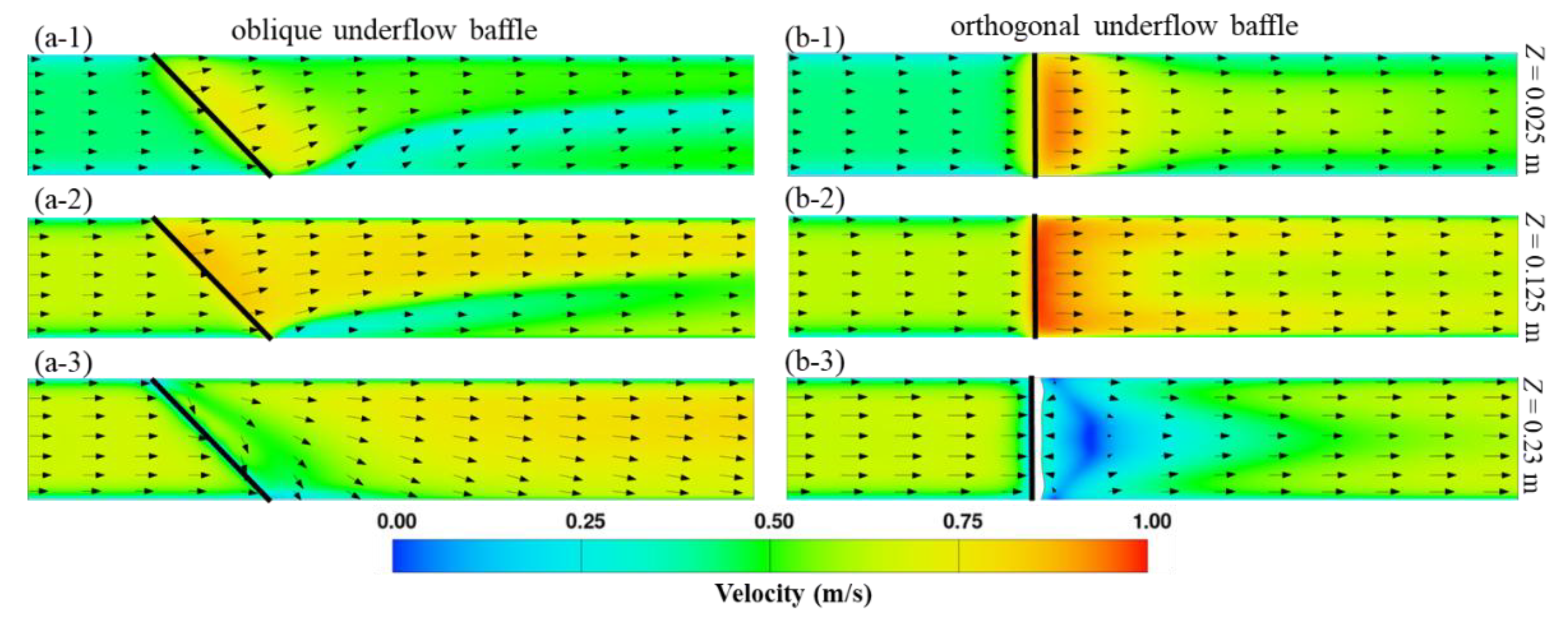

For a better understanding on the effects of the tested baffle configurations on flow characteristics, the velocity distributions and velocity vectors computed for

Q = 0.15 m

3/s on three horizontal planes above the channel bottom (

Z) are compared for both orthogonal and oblique baffle cases in

Figure 4. These planes are located near the channel bottom at

Z = 0.025 m, near the mid-depth of the flow at

Z = 0.125 m, and near the water surface at

Z = 0.23 m, which is above the bottom edge of the underflow baffle (whose position is indicated by the black line in the figure). For the orthogonal baffle case, the velocity vectors on all planes are mostly parallel to the sidewalls and to each other, and the flow velocity does not alter considerably across the channel width. In contrast, significant alterations in velocity magnitude and vectors are observed across the channel width for the oblique baffle case with high-momentum fluids concentrating toward the left wall, particularly for the near-bed and mid-depth planes. In addition, the velocity magnitudes on the near-bed and mid-depth planes in the vicinity of the baffle are significantly higher in the orthogonal baffle case as compared to the oblique baffle case. Whereas the near near-surface velocities for the orthogonal baffle case are significantly lower, even approaching zero, indicating the formation of a large flow separation zone above the baffle’s bottom edge and behind the baffle. However, this phenomenon is not observed in the case of oblique baffle, where only some diversion of the near free surface flow toward the right wall is observed, indicating the vortex formation. This also results in reducing the velocity magnitude toward the right wall in the vicinity of oblique baffle. Furthermore, in the vicinity and immediate downstream of the baffle, the velocity magnitudes among different planes deviate less from one another for the oblique baffle than that for the orthogonal baffle, indicating a strong mixing of flow among layers caused by the helical flow downstream of the oblique baffle. These alternations in the flow characteristics due to the baffle non-orthogonality can affect the bedload transport phenomena as discussed later.

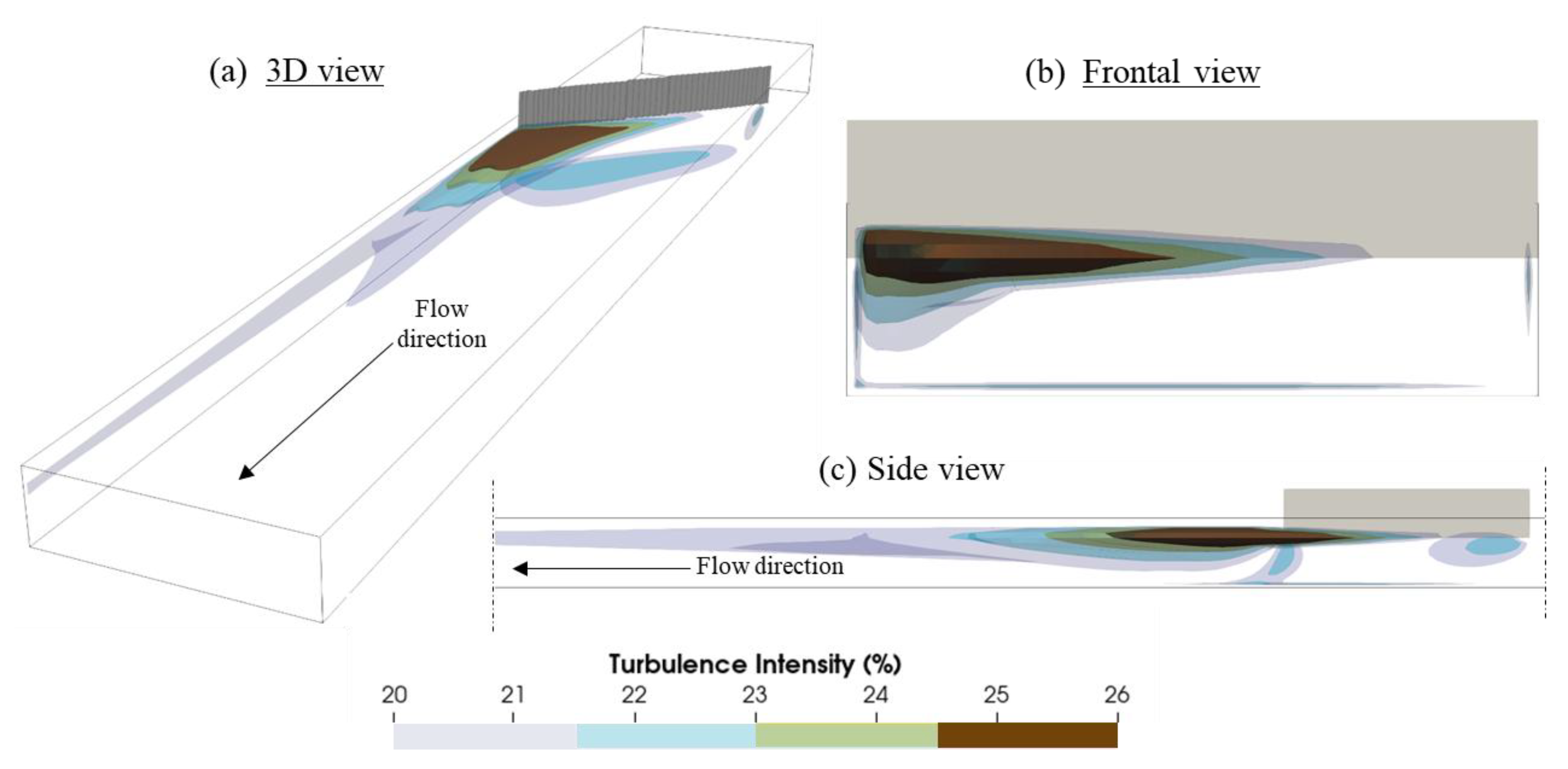

In order to visualize the vortex region better, four iso-surfaces with turbulence intensities of 20%, 22%, 24% and 26% are provided in

Figure 5 for case 2. The highest turbulence intensities occurred near the water surface toward the right wall of the channel downstream of the underflow baffle. This is also the place where the vortex arises. Regions of smaller turbulence intensities (20% and 22%) emerge toward the right wall of the channel and the bottom of the channel downstream of the underflow baffle. In rectangular open channels without obstacles, the turbulence intensity near the free surface is typically in a range of few percent, while the near bed turbulence intensity often exceeds 10%, especially in the streamwise direction [

41]. The iso-surfaces with high turbulence intensities of more than 20% indicate a flow separation or vortex structures with high turbulence energy.

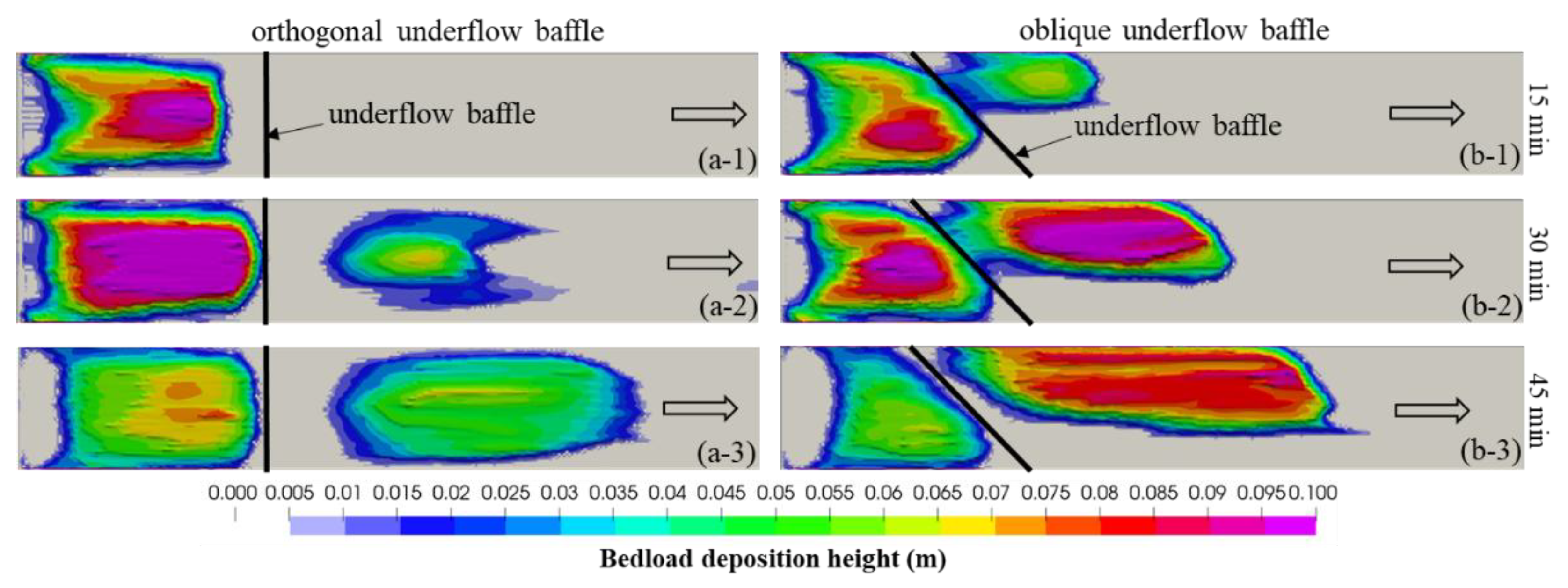

4.2. Influence of Baffle Obliquity

Figure 6 compares the bedload depositions after 15, 30 and 45 minutes of simulation time computed for the oblique baffle at

Q = 0.15 m

3/s to that computed for the orthogonal baffle. For the orthogonal baffle, no bedload deposition occurred immediately in the downstream of the baffle due to high local velocities as shown in

Figure 4(b-1). However, at the later stage, bedload deposition starts accumulating at some distance downstream of the orthogonal baffle in the central area of the channel before gradually spreading across the entire channel width, shown in

Figure 6(a-3), as the upstream sediment deposition migrates toward the baffle. In contrast, the oblique baffle model exhibits a distinct deposition pattern. The bedload primarily accumulated in the central region and along the left side of the channel and the zone on the right side of the channel downstream of the baffle’s trailing edge remained largely free from deposition, although the near-bed flow velocity is higher toward the channel center and left side as compared to the right side as found in

Figure 4(a-1) – indicating that the bedload transport and distribution is strongly influenced of the vortex. Throughout the simulation, the bedload moved firstly toward the left side of the channel and later toward the channel center area, with the bedload-free region on the right side remained relatively stable. Overall, the rate of bedload deposition in the downstream side of the baffle is noticeably lower for the orthogonal baffle as compared to the oblique one. Furthermore, nearly all of the introduced sediment remained within the model for the oblique underflow baffle after 45 minutes of simulation, unlike 93% of the introduced sediment remained in the channel for the orthogonal baffle.

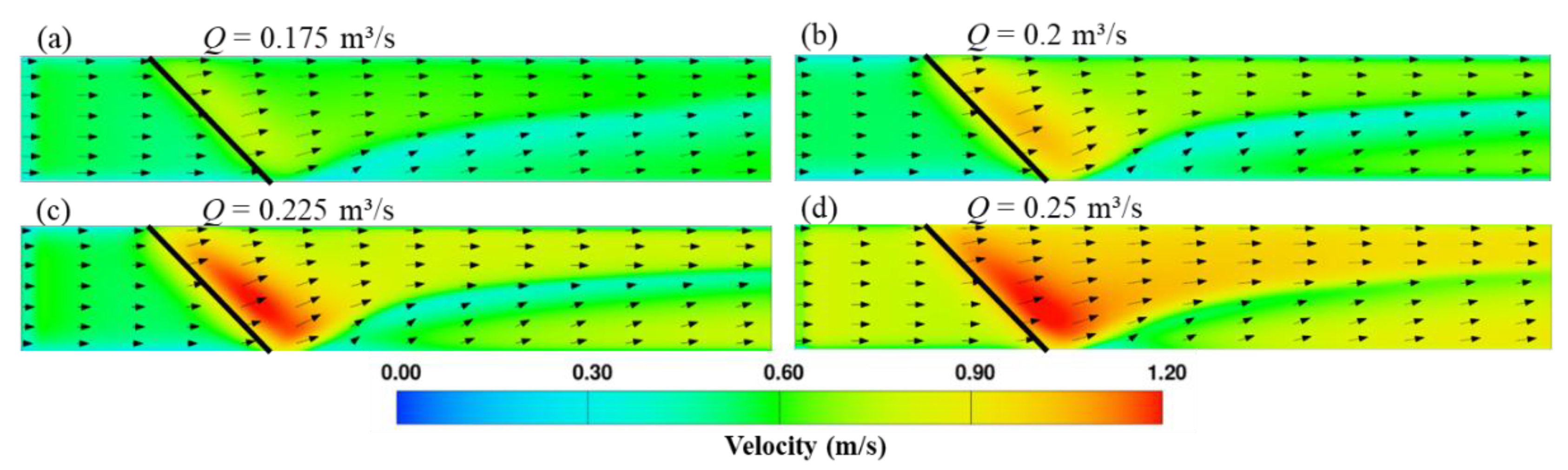

4.3. Influence of Discharge Variation

Figure 7 compares the velocity distributions and velocity vectors on the near-bed plane (at

Z = 0.025) observed while varying the discharge from 0.175 m

3/s to 0.25 m

3/s, under the same water level. As expected, an increase in the discharge results in increasing the near-bed velocities downstream of the oblique baffle, which is relating to a higher bed shear stress and an enhanced bedload transport with an increasing discharge as found in

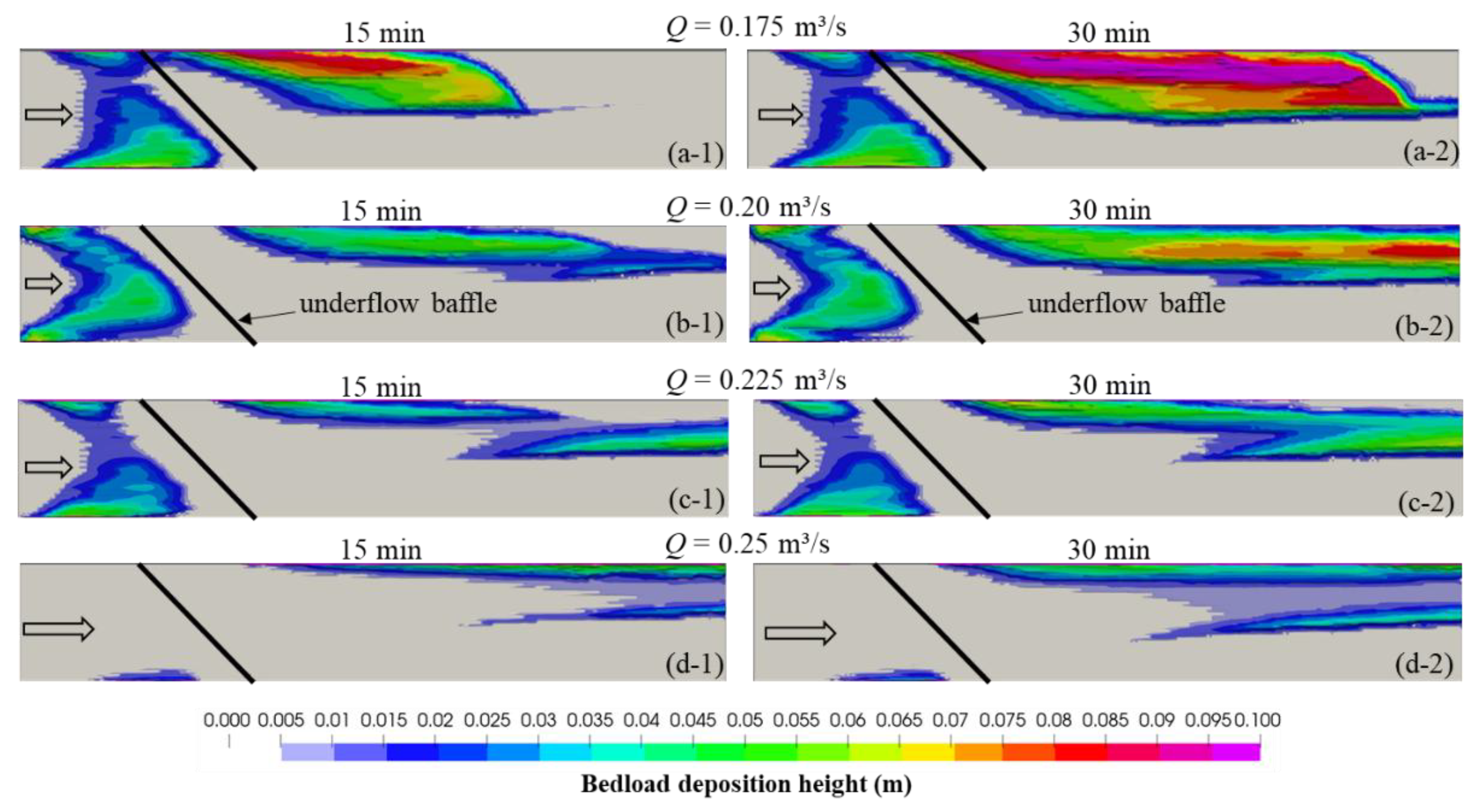

Figure 8. It is also observed that the overall velocity distribution patterns and vector orientations remain largely unchanged with varying discharge. Furthermore, the region of lower velocities downstream of the trailing edge of the baffle (in the vortex area) remains quite unchanged across all tested discharges.

An increase in the discharge from 0.175 m

3/s to 0.25 m

3/s, while maintaining the same water level is expected to increase the bedload transport capacity, as observed in

Figure 8. Even at higher discharges, the bedload failed to deposit in the vortex region on the right side of the channel. As the discharge increased, a part of the primary bedload deposition zone shifted toward the channel center. An increasing bedload transport capacity resulting from increasing discharge causes the deposition zones to spread further downstream and to become flatter. Increasing discharge also resulted in reducing the bedload deposition in the upstream of the baffle, with only a negligible deposition observed toward the right side of the channel for the highest discharge. Furthermore, the bedload deposition free vortex zone on the right side of the channel expanded with an increase in discharge, considerably for the lower discharges. Due to the limited channel length, the complete downstream development of the bedload deposition pattern could not be fully captured, particularly at higher discharges where the bedload traveled further downstream. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies investigate the influence of oblique underflow baffles on bedload transport using a longer domain setup.

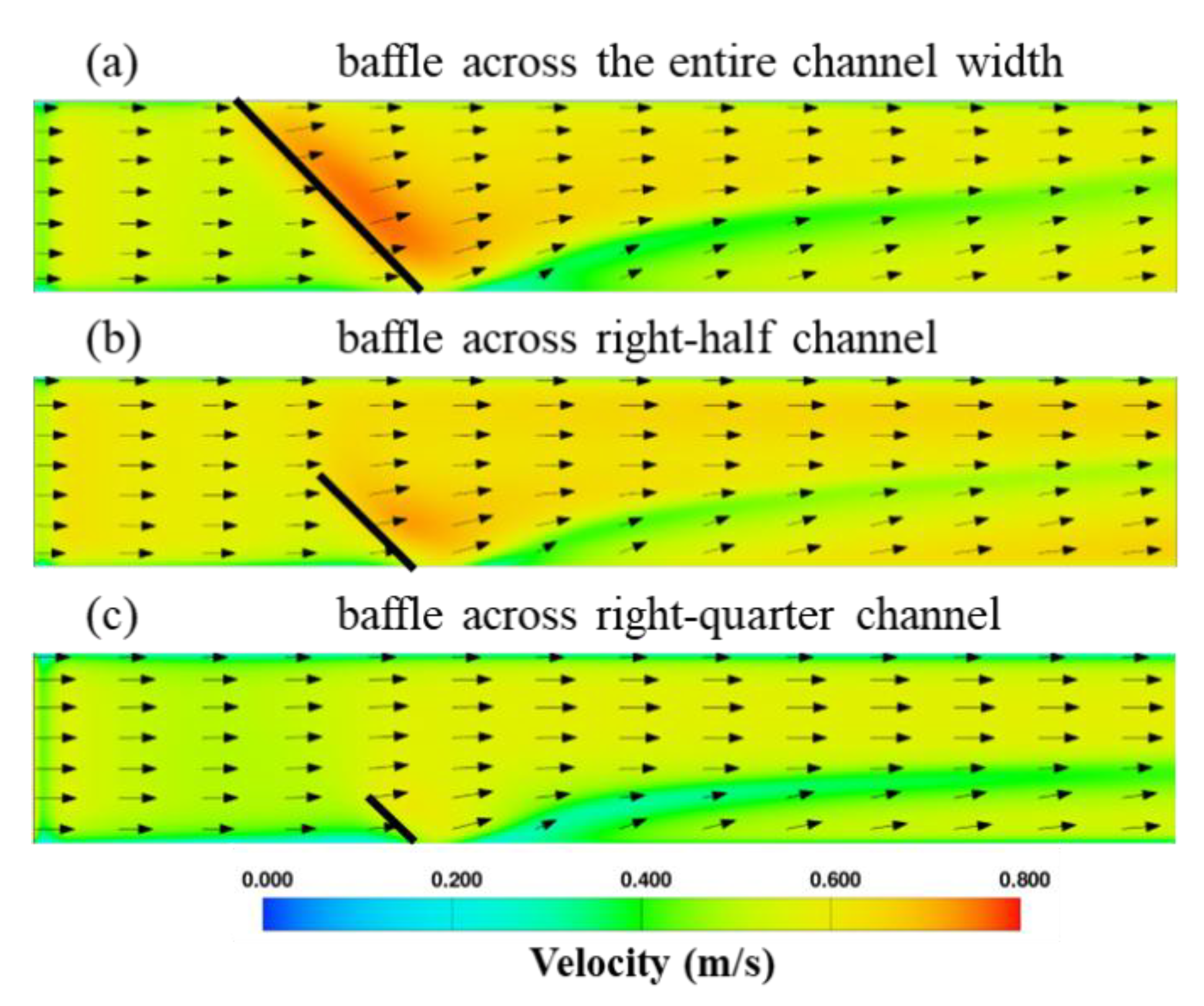

4.4. Influence of Channel width Coverage by Baffle

Figure 9 compares the velocity distributions and velocity vectors on the near-bed plane (at

Z = 0.025) obtained under numerous channel width coverage by the oblique baffle, namely full channel width, right-half channel width, and right-quarter channel width, at a constant discharge of 0.175 m

3/s. The results indicate significant decrease in the near-bed velocities toward the channel center and left side of the channel and more linear vector fields with reduction in the width coverage by baffle. Interestingly, less significant variations are observed toward the right side of the channel – indicating the vortex generation and its impact on the flow field even for the narrowest of baffle.

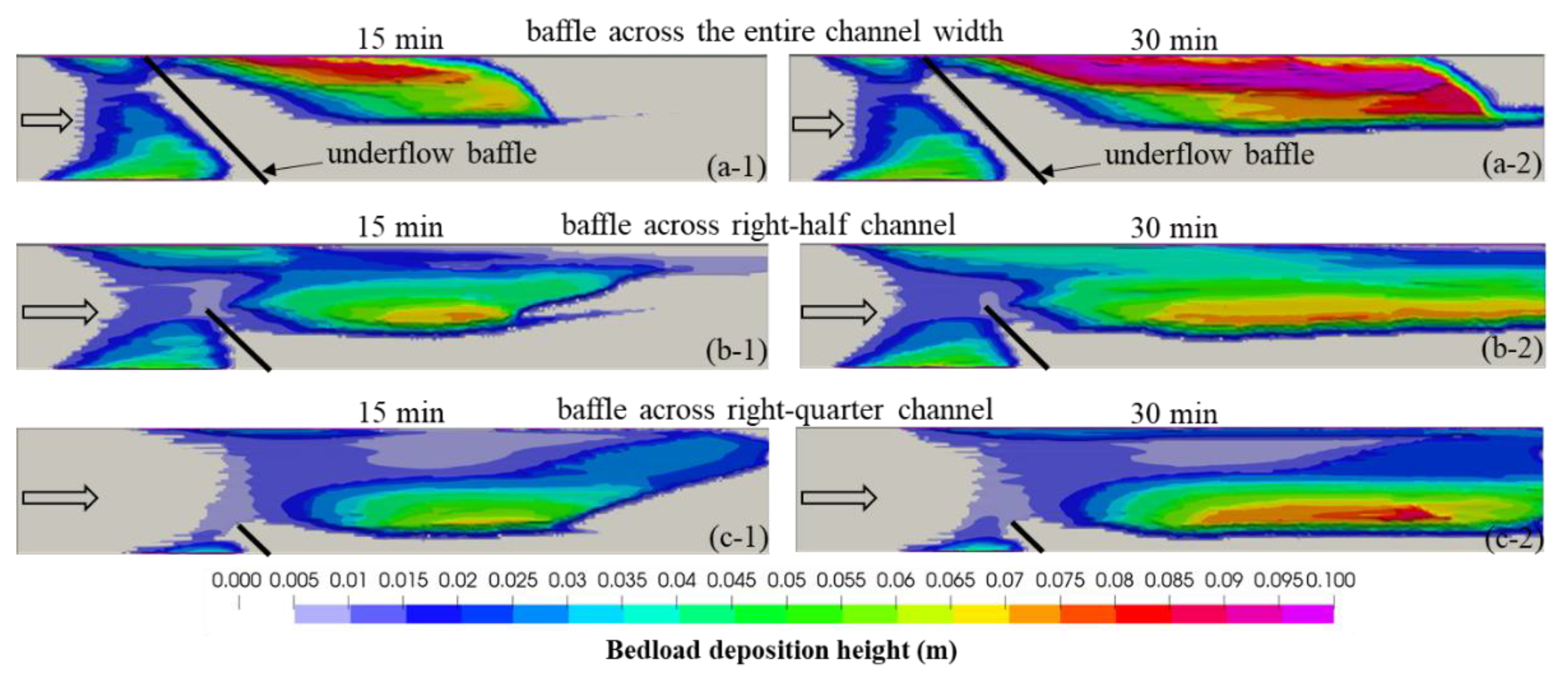

Furthermore,

Figure 10 compares the computed bedload depositions at a constant

Q = 0.175 m

3/s after 15 and 30 minutes of simulation times for full channel width, right-half channel width, and right-quarter channel width coverages by the baffle. Interestingly, the bedload deposition is not observed along the right side of the channel even for right-half and right-quarter baffle cases, signifying the influence of the vortex that is still strong enough despite reducing the baffle’s coverage. However, the bedload-free zone on the right side of the channel narrows with decreasing the baffle coverage and vortex affected zone, with about 0.32 m wide bedload-free zone observed for the baffle spanning across the entire width of the channel which is reduced to about 0.29 m and 0.13 m wide zones for 50% and 25% coverages of the channel width, respectively. Furthermore, the zone of higher sediment deposit moves toward the right side of the channel as the baffle coverage is reduced and concentrated toward the right side, with negligible deposition found toward the left side for the 25% baffle coverage case. After 30 minutes of simulation, around 88% and 67% of the introduced sediment remained in the model for baffle coverages of 50% and 25% of the channel width, respectively, which are lower than the 98% sediment retention observed for the baffle spanning the entire channel width.

4.5. Comparison of Sediment Deposition

Table 2 compares the percentage of deposited sediment remaining in the channel and the percentage width of the bedload-free zone at the channel outlet obtained at the end of each simulation for the tested cases. The results indicate that the use of oblique underflow baffle consistently produces a bedload-free region on the right side of the channel. For the lowest discharge, the width of this region is approximately 0.25 m. As the discharge was increased, the bedload-free zone expanded, reaching its maximum width at the intermediate discharges. However, for the three highest discharge cases, the width of this region remained nearly constant.

Table 3 also indicates that higher discharge results in less sediment deposited in the model, as expected. It can also be observed that a smaller channel width coverage leads to reduced sediment deposition. Furthermore, in the case of the orthogonal baffle, sediment transport occurs slightly faster than that with the oblique baffle.

5. Discussion

The promising outcome on the potential use of oblique vertical underflow baffles in managing bedload depositions in channels and at intake structures provided above, encourages a follow up experimental investigation that will be performed soon. These experiments will be useful in validating the findings of the current CFD study and for advancing the research toward the development of comprehensive design guidelines on the use of oblique underflow baffles. Although the absolute results could not be compared with the experiments, comparing cases from numerous discharges, obliquities, and channel width coverages provided an overall understanding on the underlying flow mechanics and functionality of underflow baffles and their usability in managing bedload deposits. Additionally, to ensure the reliability of the numerical simulations, several crucial steps were taken. A mesh-sensitivity analysis was performed to determine an appropriate mesh resolution, followed by an assurance of the numerical stability and confirmation that the flow upstream of the baffle was fully developed.

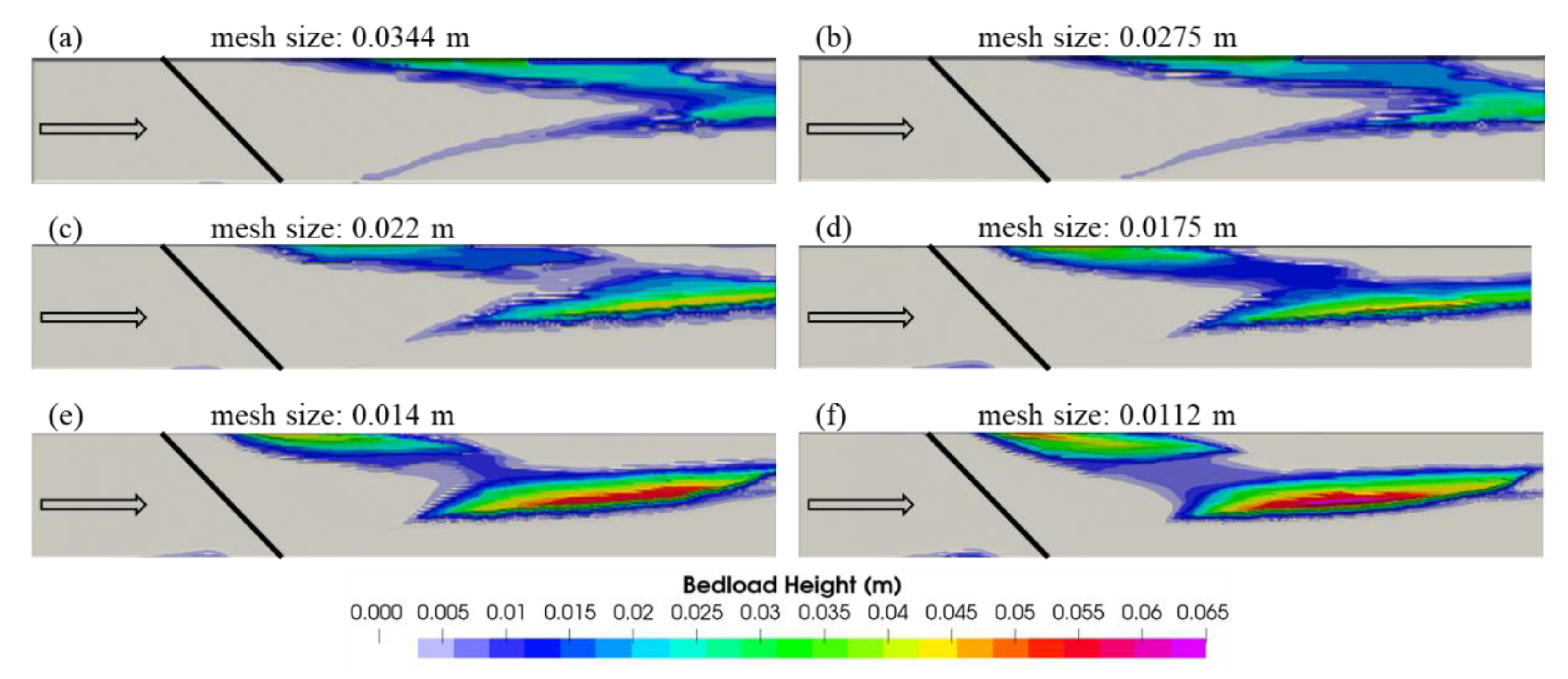

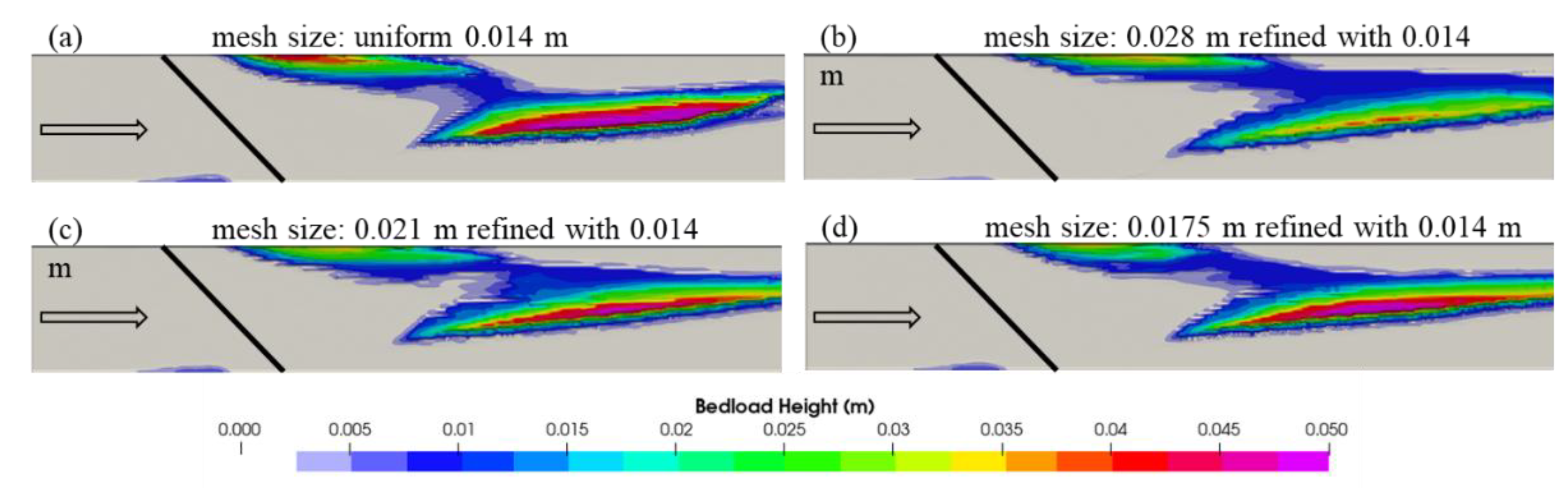

4.1. Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

The numerical mesh used for simulations in FLOW-3D typically consists of uniform hexahedral elements. A sensitivity analysis was conducted for the sediment transport model with a discharge rate of

Q = 0.2 m

3/s. To save time, the sensitivity analysis was performed for a model without considering the long inlet region. Given that bedload transport is the primary focus of this study, the analysis first aimed to establish the optimal mesh size near the channel bottom. For this purpose, the bedload depositions were evaluated at numerous uniform mesh sizes with a constant growth ratio of 1.25. Once the optimal mesh size was identified, it was retained in the near-bed region (where the bedload transport occurs), while the mesh size away from the bed was increased to reduce the computational time. The simulations for the mesh sensitivity analysis were run for 7.5 minutes in the restart model, as the bedload deposition pattern stabilized within this time, with minor changes observed for the remainder of the simulation.

Figure 11 shows the bedload depositions for models with six different mesh sizes.

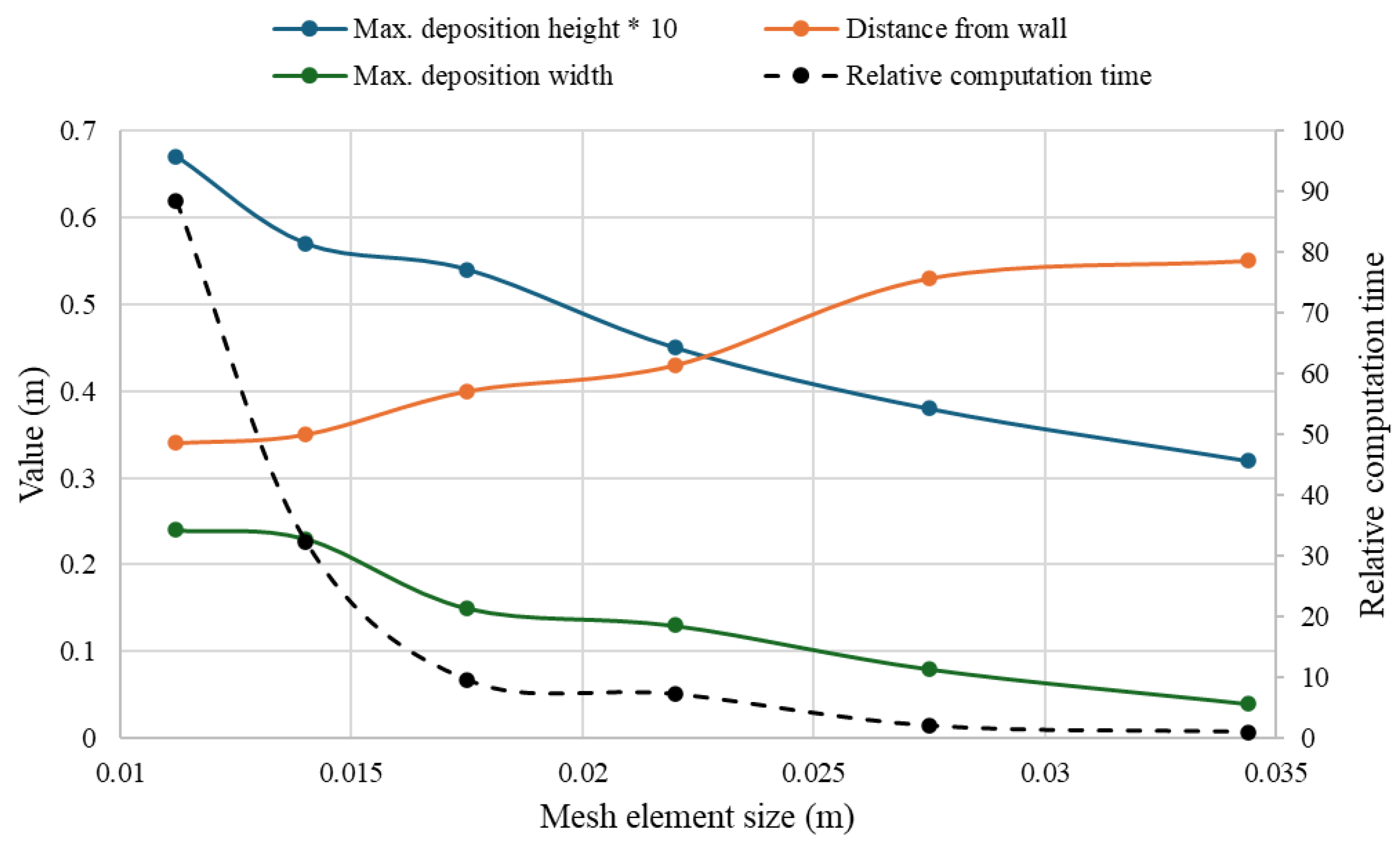

The results obtained from the simulations with coarser meshes (mesh sizes of 0.0344 m and 0.0275 m) show a distinct line of bedload accumulation extending from the right edge (or tailing edge) of the underflow baffle to the main bedload deposition area on the left side of the channel (in direction of flow). This line becomes less noticeable as the mesh is refined further. Additionally, coarser meshes result in lower bedload deposition heights compared to the finer meshes. With finer meshes, bedload transport slows down, leading to a more detailed and refined bedload deposition pattern, characterized by smoother transitions between different deposition zones. To better understand how bedload deposition changes with varying mesh sizes, several geometric parameters have been measured and are presented in

Figure 12. These parameters include the maximum bedload deposition height, the maximum width of the main bedload deposition area, and the distance from the right-hand wall corresponding to deposition heights exceeding 0.02 m. Also shown is the relative computation time, which is the computational time for a specific mesh size divided by the computational time for the model with the coarsest mesh size of 0.0344 m.

Figure 12 shows that the width of the main bedload deposition zone, defined as the region where bedload deposition exceeds 0.02 m, in the central part of the channel changes with the mesh size refinement. Only minor changes are observed between the two finest meshes. The distance between the main bedload deposition body and the right channel wall (in the direction of flow) decreases with mesh refinement, again with only marginal differences between the two finest meshes. As the mesh becomes finer, the maximum bedload deposition height increases; however, for this parameter, a difference was observed between the two finest meshes. In addition, the length of the main deposition area is also changed marginally for the refinement between the two finest mesh sizes. However, this parameter could not be used for sensitivity analysis for the coarser meshes, as this length stretches beyond the model boundaries for the coarser meshes. For the model with a mesh size of 0.014 m, the deposition zone length was 2.5 m, while for the model with a mesh size of 0.0112 m, it was 2.56 m, which is marginally higher. Moreover, the mesh with an element size of 0.014 m was selected for further sensitivity analyses, as it provided very similar results to that obtained for the finest mesh (0.0112 m) with approximately one-third of computation time. In the next step, the near-bottom region of the channel (first four mesh layers, where the maximum bedload deposition occurred), which is critical for bedload transport, were kept constant with a mesh resolution of 0.014 m in the vertical direction. Similarly, the first mesh layer adjacent to the channel sidewalls was also maintained at 0.014 m, while a coarser mesh was used away from the walls as shown in

Figure 1(b). A gradual transition was applied between the finer and coarser mesh zones.

Figure 13 compares the bedload deposition patterns computed for different mesh configurations with the first four vertical mesh layers set to 0.014 m. In these cases, the mesh sizes further away from the boundaries were varied from 0.028 m (twice the boundary mesh size) to 0.021 m (1.5 times the boundary mesh size) and then to 0.0175 m (1.25 times the boundary mesh size). The bedload deposition patterns observed for the 0.0175 m and 0.021 m size meshes are comparable to that obtained for the uniform mesh of 0.014 m. All these cases are exhibiting two distinct deposition zones downstream of the baffle: one near the channel center (possible zone of vortex) and another on the left side of the channel. However, the deposition depth near the channel center obtained for the varying mesh sized 0.028 m is significantly less than the remaining three cases as shown in

Figure 13.

In addition,

Table 3 compares the change in geometric bedload deposition parameters, corresponding to that shown in

Figure 12, for deposition heights exceeding 0.02 m, across different mesh configurations compared in

Figure 12.

Table 3, alike

Figure 12, indicates that the bedload deposition parameters for models with mesh sizes of 0.014 m, 0.0175 m, and 0.021 m away from the boundaries yield very similar results that are considerably different from the results obtained for the 0.028 m mesh. Moreover, due to the significantly reduced computational time required by the model with a 0.021 m mesh in the channel core area away from the boundaries (one-fifth of the computation time compared to the model with a uniform mesh of size 0.014 m) to compute satisfactory results, the nonuniform mesh of 0.021 m away from the boundaries was selected for the remaining simulations of this study.

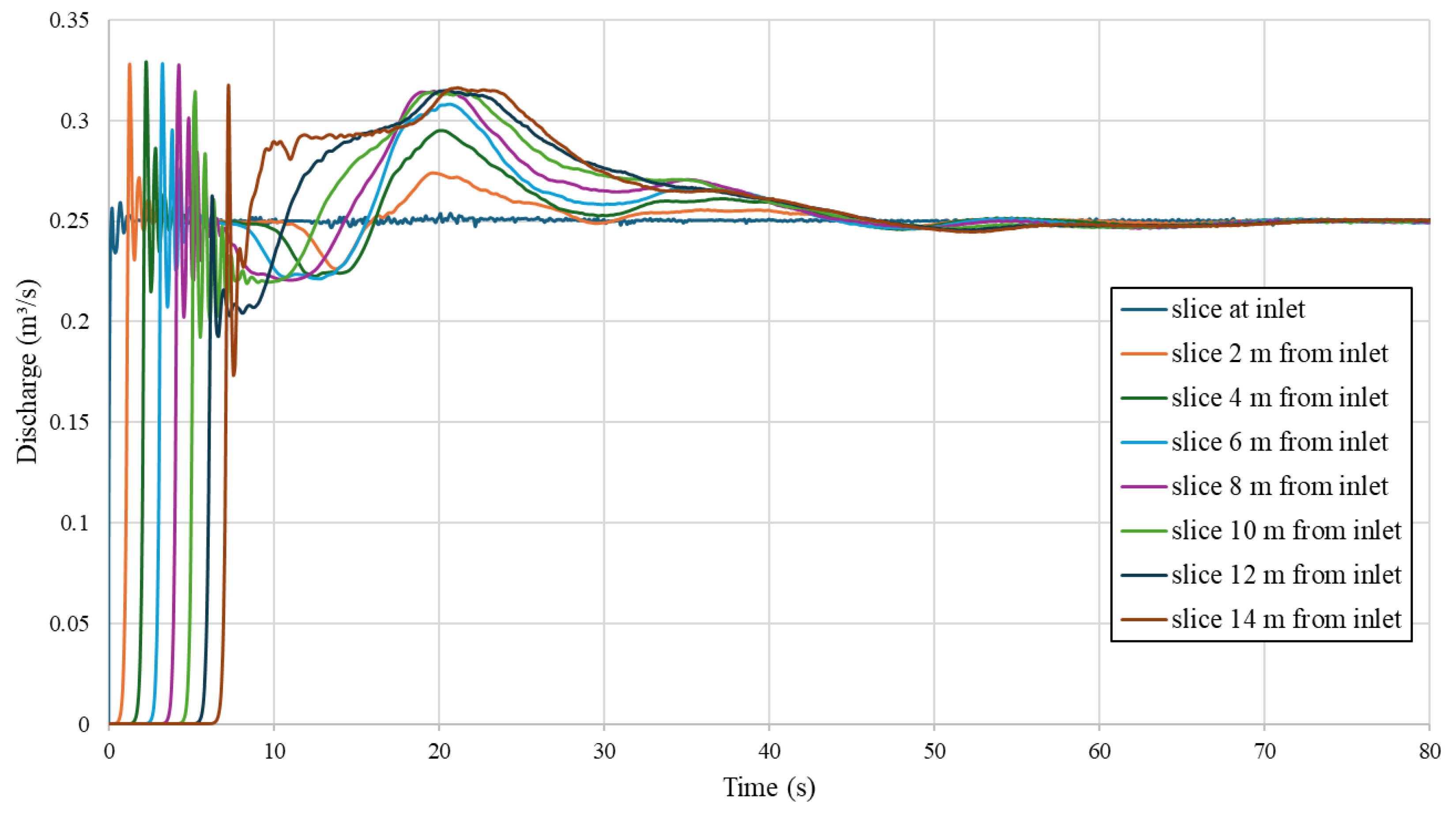

5.2. Numerical Stability Control and Flow Development

The presented simulations were conducted in the following sequence: at first, a hydrodynamic simulation without sediment input was set up and ran for 80 seconds; subsequently, a restart simulation was initiated for the morphodynamic model, during which sediment was continuously introduced for an additional 1800 seconds. To ensure that the system had reached a steady-state condition prior to starting the morphodynamic simulations, discharge across eight vertical planes placed at 2 m intervals (sliced through the model for the investigated channel with the oblique underflow baffle) were obtained throughout the entire simulation period. The temporal variations in the obtained discharge data are presented in

Figure 14 for the case 6 with the highest discharge. It was observed that the discharge fluctuates significantly at all the cross sections up to 20 seconds of the simulation time before flattening and then becoming stable beyond 50 seconds of the simulation time. Therefore, in the subsequent restart simulation, in which sediment was introduced into the model, the discharge across all monitored cross sections remained steady at 0.25 m

3/s.

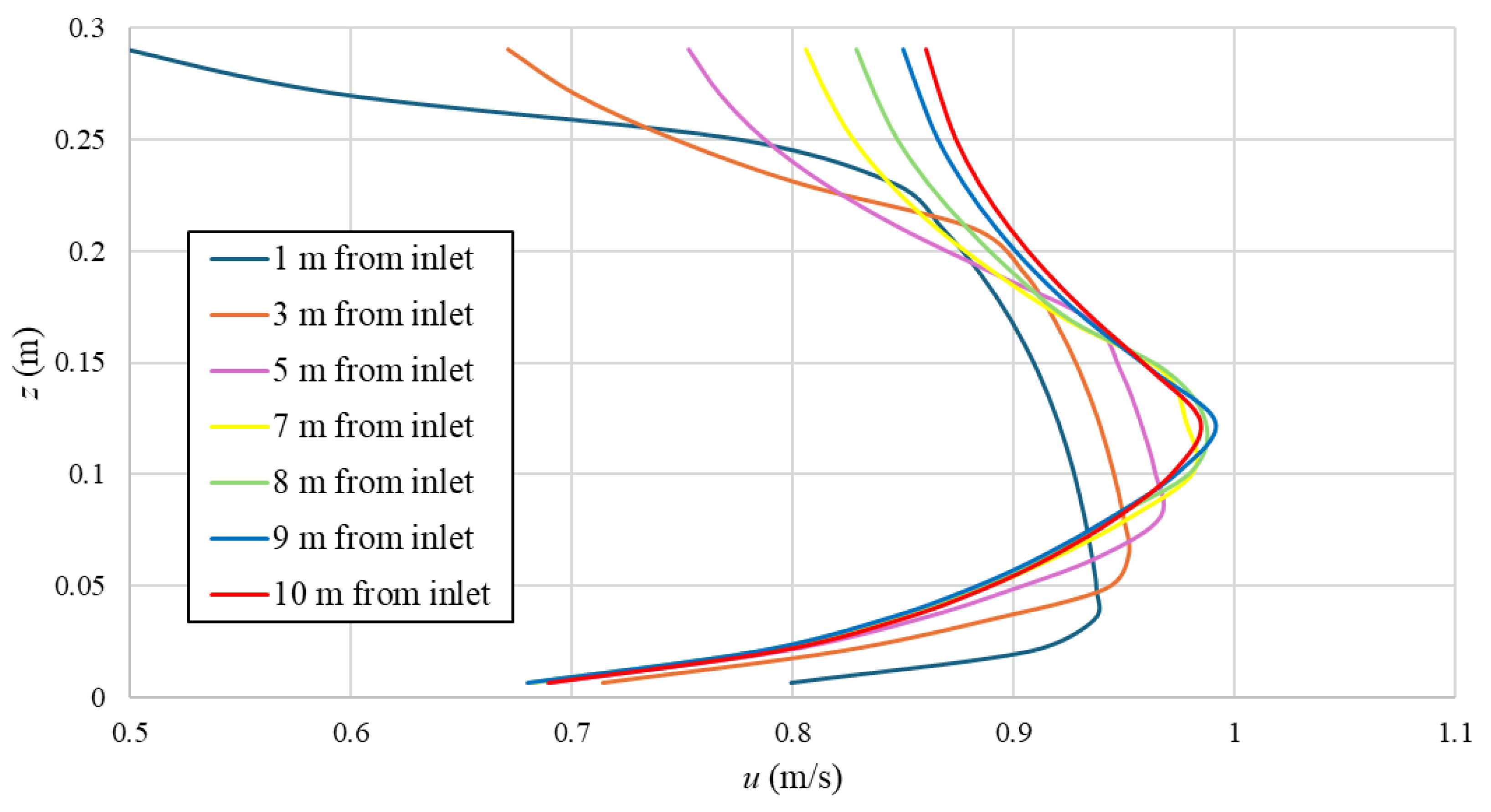

It was also ensured that the flow approaching the baffle became fully developed in the channel before performing the restart simulations with sediment transport. For this purpose, velocity profiles were analyzed in the middle of several cross-sections upstream of the underflow baffle, i.e., at 1 m, 3 m, 5 m, 7 m, 8 m, 9 m, and 10 m from the inlet, for Case 6 with the highest tested discharge of 0.25 m

3/s. The results presented in

Figure 15 indicate the development of boundary layer along the flow direction. As the flow moves close to the baffle, the velocity profiles tend to match each other, with marginal deviations observed between the velocity profiles obtained at 9 m and 10 m from the inlet. The maximum difference between these two velocity profiles was only 1.4%, occurring near the channel bed. Therefore, the flow approaching the underflow baffle is considered fully developed. Since the flow development was confirmed for the maximum discharge case, it can be assumed that the flow was also developed for all other cases with lower discharges. In addition, the velocity dips observed in the velocity profiles are possibly related to the narrow channel flow conditions, as

b/h = 4, which is less than 5 [

42,

43,

44], and to some possible backwater effects resulting from the underflow baffle. Although the upstream water level is specified as 0.25 m by the inlet boundary condition, it rises to approximately 0.29 m upstream of the underflow baffle due to flow obstruction caused by the baffle. The underflow baffle, whose lower edge is positioned at a height of

Z = 0.2 m, also produces a distinctive velocity profile, characterized by lower velocities above the baffle edge and higher velocities below it. The elevated velocities beneath the baffle resemble the flow behavior observed under a sluice gate [

45,

46], distinguishing this pattern from typical open-channel flow without obstacles [

44].

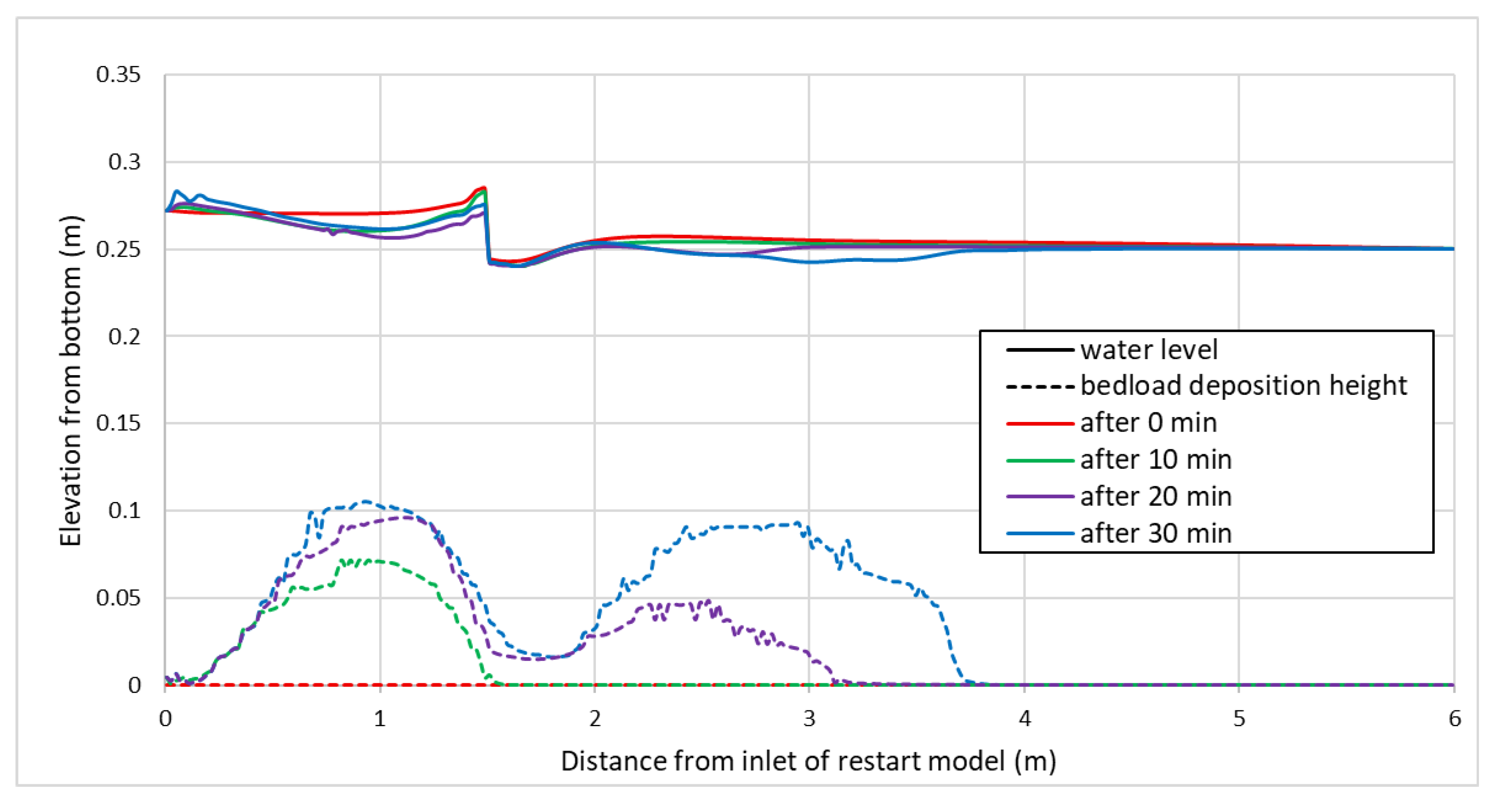

In addition, it was evaluated whether the water levels remain stable throughout the simulation. Although the boundary conditions of the CFD model were kept constant for the entire simulation period, sediment inclusion into the model could potentially affect the water levels by occupying volume within the flow domain.

Figure 16 compares the water surface elevations and bedload deposition heights along the central longitudinal section for case 2 (with the highest bedload depositions) obtained for simulation times of 0, 10, 20, and 30 minutes from the restart simulation. It is found that the bedload deposition rises over time and gradually migrates toward the outlet of the model. Upstream of the underflow baffle, i.e., up to 1.5 m distance from the inlet of the restart mode (see

Figure 16), rise in the water level (afflux) occurs due to the damming effect of the baffle, which also results in forming a sediment deposition zone upstream of the baffle unlike in the higher discharge case discussed above. Water level drops at the baffle location, which results in accelerating the flow and lesser sediment deposition as compared to the upstream and downstream of the baffle. The maximum difference in water elevation downstream of the baffle is 0.0126 m, corresponding to a 5.04% change due to the introduction of sediment into the model running under constant discharge and outflow boundary conditions.

5.3. Summary of Findings and Limitations

The results of this CFD investigation suggest that oblique underflow baffles have promising potential as a practical and cost-effective method to manage the bedload transport and deposition in open channels. By generating a strong vortex in flow direction, these hydraulic structures are capable of redirecting bedload and maintaining bedload-free zones within a channel or near critical hydraulic infrastructure, such as water intakes. This controlled redirection of bedload offers an alternative to more complex or invasive bedload management methods and can be particularly useful during high transport events, such as floods, where rapid sediment accumulation poses operational risks. In addition to their effectiveness, underflow baffles offer practical advantages in terms of simplicity and adaptability. They are relatively easy to install and reposition, because they only need to be partially submerged (e.g., to 20% of the flow depth, as demonstrated in this study) and can be integrated into existing infrastructure with limited modification.

In addition, the limitations and assumptions associated with this study must be acknowledged. Firstly, the results presented in this study have not yet been validated against physical experiments. Although the observed trends are consistent and physically plausible, further verification is planned to be undertaken in a continuation study in the future. Secondly, the simulations were carried out using a RANS approach with two-equations turbulence model. While RANS models are widely used and computationally efficient, they can have limitations in accurately resolving complex flow structures and transient bedload dynamics, particularly in the vortex-dominated flows. Consequently, the precision of the predicted bedload transport patterns should be interpreted with caution. A third limitation concerns the noticeable inconsistency in water levels observed during the simulation, particularly downstream of the baffle. Despite constant boundary conditions, the introduction of sediment led to a gradual decrease in downstream water surface elevation, with a maximum deviation of approximately 0.0126 m (5.04%). While this change is relatively small, it indicates that the interaction between sediment volume and flow resistance warrants further investigation, especially for longer time scales or in channels with low flow depths.

6. Conclusions

The present numerical study explores the potential of oblique vertical underflow baffles in influencing the bedload transport and deposition in open channel flows, which is necessary in safeguarding intakes and similar structures from bedload intrusion. The simulations were performed using the commercial CFD software FLOW-3D under numerous discharges, baffle alignments, and channel width coverages. The simulations with oblique baffle indicate that the flow conditions induced by the underflow baffle produces a vortex toward the trailing edge of the baffle (right side of the channel), which prevented any bedload deposition in that zone. Consequently, bedload primarily deposited in the central area of the channel, adjacent to the vortex, and on the left side of the channel, depending on the discharge. These observations suggest the effectiveness of an oblique underflow baffle in redirecting bedload away from the trailing edge of the baffle, which is on the right side of the channel here. In contrast, the lack of baffle generated vortex for the orthogonal underflow baffle results in bedload deposits across the entire channel width, highlighting the significance of oblique baffle. This makes the oblique baffle a cost-effective and easily adaptable solution for managing the bedload transport and deposition in channels, intakes, and sluices.

In addition, this study also demonstrates that the effect of the oblique underflow baffle remains significant even under higher discharge conditions, which corresponds to increased bedload transport rates. In fact, the oblique baffle becomes more effective in shielding one side of the channel (which is adjacent to the trailing edge of the baffle) from bedload deposition as the discharge and the bedload transport capacity increases. This is evidenced by the expansion of the bedload-free vortex region with increasing discharge. This study also demonstrates that the influence of oblique underflow baffle on bedload transport and deposition persists even when the baffle spans only 25% or 50% of the channel width, which shows the potential of cost-effective design and structural support only from one side of the channel.

Physical model experiments are planned to be underway soon, and future work shall focus on validating the CFD results before expanding the current numerical study for numerous channel conditions and applications. Further investigations shall also assess the influence of baffle geometry, vertical inclination, bedload variations, and channel geometries to come up with a comprehensive design recommendation for practical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.; methodology, T.K., S.K.; validation, T.K., S.K.; formal analysis, T.K., S.K.; investigation, T.K.; project administration, T.K., N.R.; writing – original draft preparation, T.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K., S.K., N.R.; visualization, T.K., S.K.; supervision, N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the first author of this paper used ChatGPT (version 5) to assist with grammar checking and stylistic refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| b |

channel width (m) |

| cb,i |

amount of grain fraction (-) |

| CFD |

Computational fluid dynamics |

| di |

dimensional grain diameter (m) |

| d*,i |

dimensionless grain size (-) |

| e |

Eulers constant (-) |

| g |

gravity constant (m/s2) |

| h |

gravity constant (m/s2) |

| h’ |

distance from channel bottom to underflow baffle (m) |

| l |

total channel length (m) |

| li |

inlet region length (m) |

| lr |

restart model length (m) |

| RANS |

Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes |

| RNG |

Re-normalization group |

| Q |

discharge (m3/s) |

| Z |

distance from channel bottom (m) |

| β |

approach-specific coefficient for bedload transport (-) |

| ϕi |

transport intensity of the sediment grain fraction (-) |

| θi |

local Shields parameter (-) |

| θ’cr,i |

critical Shields parameter (-) |

| ρf |

density of fluid (kg/m3) |

| ρi |

density of sediment (kg/m3) |

| μi |

dynamic viscosity of fluid (N∙s/m2) |

| 3D |

Three-dimensional |

References

- Scheuerlein, H. Die Wasserentnahme aus geschiebeführenden Flüßen; Ernst & Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Reisenbüchler, M.; Bui, M.D.; Skublics, D.; Rutschmann, P. Sediment management at run-of-river reservoirs using numerical modelling. Water 2020, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogen, J.; Bønsnes, T.E. The impact of hydropower development on the sediment budget of the River Beiarelva, Norway. Sediment Budgets 2005, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kondolf, G.M.; Rubin, Z.K.; Minear, J.T. Dams on the Mekong: Cumulative sediment starvation. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 5158–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisser, D.; Frolking, S.; Hagen, S.; Bierkens, M. Beyond peak reservoir storage? A global estimate of declining water storage capacity in large reservoirs. Water Resour. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E.; Bledsoe, B.; Jacobson, R.; Poff, N.; Rathburn, S.; Walters, D.; Wilcox, A. The natural sediment regime in rivers: Broadening the foundation for ecosystem management. BioScience 2015, 65, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönung, B.E. Beispiele zwei-und dreidimensionaler Strömungsberechnungen. In Numerische Strömungsmechanik: Inkompressible Strömungen mit komplexen Berandungen; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1990; pp. 245–273. [Google Scholar]

- Cigana, J.F.; Lefebvre, G.; Marche, C.; Couture, M. Experimental capture efficiency of floatables using underflow baffles. In Proceedings of the Collection Systems Conference 2000, Water Environment Federation; 2000; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, T. A methodology to design and/or assess baffles for floatables control. J. Water Manag. Model. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, T.; Rüther, N. Introduction to the effect of flow under angled vertical baffle walls on bedload transport. In Proceedings of the 41st IAHR World Congress, Singapore; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Ghosh, S.N.; Chatterjee, M. Local scour due to submerged horizontal jet. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1994, 120, 973–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghzayel, A.; Beaudoin, A. Three-dimensional numerical study of a local scour downstream of a submerged sluice gate using two hydro-morphodynamic models, SedFoam and FLOW-3D. C. R. Méc. 2023, 351, 525–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamee, P.K.; Pathak, S.K.; Mansoor, T.; Ojha, C.S.P. Discharge characteristics of skew sluice gates. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2000, 126, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshfaraz, R.; Abbaszadeh, H.; Gorbanvatan, P.; Abdi, M. Application of sluice gate in different positions and its effect on hydraulic parameters in free-flow conditions. J. Hydraul. Struct. 2021, 7, 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rentachintala, L.R.N.P. Characteristics of discharge of skew side sluice gate. J. Appl. Water Eng. Res. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, R.A.E.H. Modeling of flow characteristics beneath vertical and inclined sluice gates using artificial neural networks. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2016, 7, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Hosoda, T.; Nakato, T.; Muramoto, Y. Three-dimensional numerical model for flow and bed deformation around river hydraulic structures. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2005, 131, 1074–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, G.T.; Baranya, S.; Rüther, N. 3D CFD modeling of local scouring, bed armoring and sediment deposition. Water 2017, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Yang, J.; Lundström, T.S.; Chen, J. Hybrid modeling for solutions of sediment deposition in a low-land reservoir with multigate sluice structure. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Theobald, S.; Träbing, K. Einflüsse auf die Geschiebeaufteilung an spitzwinkligen Gerinneverzweigungen. Wasserwirtschaft 2024, 114, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgaard, A.J.; Kennedy, J.F. River-bend bank protection by submerged vanes. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1983, 109, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgaard, A.J.; Wang, Y. Sediment management with submerged vanes. II: Applications. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1991, 117, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Zomorodian, S.; Zolghadr, M.; Chadee, A.; Chiew, Y.; Kumar, B.; Martin, H. Combination of riprap and submerged vane as an abutment scour countermeasure. Fluids 2023, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Mosselman, E. Experimental study on scour around beveled submerged vanes. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanke, U. Hydraulik für den Wasserbau; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flow Science, Inc. FLOW-3D® Version 2024R1 User Manual; Flow Science, Inc.: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.flow3d.com (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Yakhot, V.; Orszag, S.A. Renormalization group analysis of turbulence. I. Basic theory. J. Sci. Comput. 1983, 1, 3–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, H.K.; Hassan, W.H. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of local scour around circular bridge pier using Flow-3D software. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing, 012150. 2020; 745. [Google Scholar]

- Kostić, T.; Theobald, S. Simulation des Geschiebetransports in Verzweigungsgerinnen mit 3-D-morphodynamischen Modellen. Wasserwirtschaft 2021, 111, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Peter, E.; Müller, R. Formulas for bed-load transport. In Proceedings of the IAHSR 2nd Meeting, Stockholm, Sweden; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijn, L.C. Sediment transport, part 1: Bed load transport. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1984, 110, 1431–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P. Coastal Bottom Boundary Layers and Sediment Transport; World Scientific: River Edge, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kostić, T.; Ren, Y.; Theobald, S. 3D-CFD analysis of bedload transport in channel bifurcations. J. Hydroinform. 2024, 26, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsby, R. Dynamics of Marine Sands; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Caviedes-Voullième, D.; Morales-Hernández, M.; Juez, C.; Lacasta, A.; García-Navarro, P. Two-dimensional numerical simulation of bed-load transport of a finite-depth sediment layer: Applications to channel flushing. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, L.K.; Eldho, T.I.; Raj, P.A. Temporal evolution of scour depth and hydrodynamics around T-shaped spur dikes. Physics of Fluids. 2025, 37, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kong, X.; Yang, Y.; Deng, L.; Xiong, W. CFD investigations of tsunami-induced scour around bridge piers. Ocean Engineering. 2022, 244, 110373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.E.; Nikora, V.I. Exner equation: A continuum approximation of a discrete granular system. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Brethour, J.; Grünzner, M.; Burnham, J. The sediment scour model in FLOW-3D. Flow Sci. Rep. 2014, 03–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mastbergen, D.R.; van den Berg, J.H. Breaching in fine sands and the generation of sustained turbidity currents in submarine canyons. Sedimentology 2003, 50, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezu, I. Turbulence intensities in open channel flows. In Proc. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1977, 261, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadia, S.; Rüther, N.; Albayrak, I.; Pummer, E. Reynolds stress modeling of supercritical narrow channel flows using OpenFOAM: Secondary currents and turbulent flow characteristics. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadia, S.; Larsson, I.S.; Billstein, M.; Rüther, N.; Lia, L.; Pummer, E. Investigating supercritical flow characteristics and movement of sediment particles in a narrow channel bend using PTV and video footage. Adv. Water Resour. 2024, 193, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezu, I.; Nakagawa, H. Turbulence in Open Channel Flows; IAHR Monographs; A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Akoz, M.S. , Kirkgoz, M.S. and Oner, A.A. Experimental and numerical modeling of a sluice gate flow. Journal of Hydraul. Res. 2009, 47, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassan L, Belaud G. Experimental and numerical investigation of flow under sluice gates. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2012, 138, 367–373.

Figure 1.

CFD model setup for the investigated channel with an oblique underflow baffle (red plane): (a) 3D view of the restart model, (b) cross-section view of the channel with the mesh, and (c) top view of the entire model.

Figure 1.

CFD model setup for the investigated channel with an oblique underflow baffle (red plane): (a) 3D view of the restart model, (b) cross-section view of the channel with the mesh, and (c) top view of the entire model.

Figure 2.

Water surface elevations (in solid line) and bedload deposition elevations (in dotted lines) along the central longitudinal section of the model at restart simulation time of 0 minutes (in red), 10 minutes (in green), 20 minutes (in magenta), and 30 minutes (in blue).

Figure 2.

Water surface elevations (in solid line) and bedload deposition elevations (in dotted lines) along the central longitudinal section of the model at restart simulation time of 0 minutes (in red), 10 minutes (in green), 20 minutes (in magenta), and 30 minutes (in blue).

Figure 3.

Plan view of lateral variations in the streamlines originating from the near bed (blue), middle of the flow depth (green), and near the free surface (red) planes of the channel for (a) orthogonal and (b) oblique baffle cases.

Figure 3.

Plan view of lateral variations in the streamlines originating from the near bed (blue), middle of the flow depth (green), and near the free surface (red) planes of the channel for (a) orthogonal and (b) oblique baffle cases.

Figure 4.

Velocity distributions and velocity vectors on three planes located at different heights above the channel bottom for (a-1 to a-3) oblique baffle case and (b-1 to b-3) orthogonal baffle case for Q = 0.15 m3/s.

Figure 4.

Velocity distributions and velocity vectors on three planes located at different heights above the channel bottom for (a-1 to a-3) oblique baffle case and (b-1 to b-3) orthogonal baffle case for Q = 0.15 m3/s.

Figure 5.

Iso-surface of turbulence intensities provided in a (a) 3D view, (b) frontal view, and (c) side view.

Figure 5.

Iso-surface of turbulence intensities provided in a (a) 3D view, (b) frontal view, and (c) side view.

Figure 6.

Bedload deposition heights obtained for (a-1 to a-3) orthogonal and (b-1 to b-3) oblique underflow baffles for Q = 0.15 m3/s after 15, 30, and 45 minutes of simulation.

Figure 6.

Bedload deposition heights obtained for (a-1 to a-3) orthogonal and (b-1 to b-3) oblique underflow baffles for Q = 0.15 m3/s after 15, 30, and 45 minutes of simulation.

Figure 7.

Velocity distributions and velocity vectors on the near bottom plane (Z = 0.025 m) for the oblique underflow baffle with (a) Q = 0.175 m3/s, (b) Q = 0.2 m3/s, (c) Q = 0.225 m3/s, and (d) Q = 0.25 m3/s.

Figure 7.

Velocity distributions and velocity vectors on the near bottom plane (Z = 0.025 m) for the oblique underflow baffle with (a) Q = 0.175 m3/s, (b) Q = 0.2 m3/s, (c) Q = 0.225 m3/s, and (d) Q = 0.25 m3/s.

Figure 8.

Bedload deposition heights after 15 and 30 minutes of simulations for the oblique underflow baffle with (a) Q = 0.175 m3/s, (b) Q = 0.20 m3/s, (c) Q = 0.225 m3/s, and (d) Q = 0.25 m3/s.

Figure 8.

Bedload deposition heights after 15 and 30 minutes of simulations for the oblique underflow baffle with (a) Q = 0.175 m3/s, (b) Q = 0.20 m3/s, (c) Q = 0.225 m3/s, and (d) Q = 0.25 m3/s.

Figure 9.

Velocity distributions and velocity vectors on the near bottom plane (Z = 0.025 m) for the oblique underflow baffle across the (a) entire channel width, (b) right-half channel width, and (c) right-quarter channel width.

Figure 9.

Velocity distributions and velocity vectors on the near bottom plane (Z = 0.025 m) for the oblique underflow baffle across the (a) entire channel width, (b) right-half channel width, and (c) right-quarter channel width.

Figure 10.

Bedload deposition heights for Q = 0.175 m3/s after 15 and 30 minutes of simulations for the oblique underflow baffle across the (a) entire channel width, (b) right-half channel width, and (c) right-quarter channel width.

Figure 10.

Bedload deposition heights for Q = 0.175 m3/s after 15 and 30 minutes of simulations for the oblique underflow baffle across the (a) entire channel width, (b) right-half channel width, and (c) right-quarter channel width.

Figure 11.

Bedload depositions for models with different uniform mesh element size after 7.5 minutes of simulation time.

Figure 11.

Bedload depositions for models with different uniform mesh element size after 7.5 minutes of simulation time.

Figure 12.

Change of geometric bedload deposition parameters and relative computation time with mesh element size refinement.

Figure 12.

Change of geometric bedload deposition parameters and relative computation time with mesh element size refinement.

Figure 13.

Bedload deposition patterns for models with consistent mesh layer thickness at the channel bottom and varying mesh resolutions in the main channel.

Figure 13.

Bedload deposition patterns for models with consistent mesh layer thickness at the channel bottom and varying mesh resolutions in the main channel.

Figure 14.

Discharges through vertical slices of the model featuring the oblique underflow baffle for the first 50 seconds of the simulation.

Figure 14.

Discharges through vertical slices of the model featuring the oblique underflow baffle for the first 50 seconds of the simulation.

Figure 15.

Velocity profiles in the middle of the channel for different distances from the channel inlet for the model without an underflow baffle.

Figure 15.

Velocity profiles in the middle of the channel for different distances from the channel inlet for the model without an underflow baffle.

Figure 16.

Water surface elevations (in solid line) and bedload deposition elevations (in dotted lines) along the central longitudinal section of the model at restart simulation time of 0 minutes (in red), 10 minutes (in green), 20 minutes (in magenta), and 30 minutes (in blue).

Figure 16.

Water surface elevations (in solid line) and bedload deposition elevations (in dotted lines) along the central longitudinal section of the model at restart simulation time of 0 minutes (in red), 10 minutes (in green), 20 minutes (in magenta), and 30 minutes (in blue).

Table 1.

Depiction of all investigated cases in this research.

Table 1.

Depiction of all investigated cases in this research.

| Case |

Discharge (m3/s) |

Underflow baffle angle with the channel axis (°) |

Underflow baffle coverage of the channel width (%) |

Simulation time (min) |

| 1 |

0.15 |

90 |

100 |

45 |

| 2 |

0.15 |

45 |

100 |

45 |

| 3 |

0.175 |

45 |

100 |

30 |

| 4 |

0.2 |

45 |

100 |

30 |

| 5 |

0.225 |

45 |

100 |

30 |

| 6 |

0.25 |

45 |

100 |

30 |

| 7 |

0.175 |

45 |

50 |

30 |

| 8 |

0.175 |

45 |

25 |

30 |

Table 2.

Percentage of deposited sediments in the channel and the percentage width of the channel at the outlet which is bedload free zone for the investigated cases.

Table 2.

Percentage of deposited sediments in the channel and the percentage width of the channel at the outlet which is bedload free zone for the investigated cases.

| Case |

Baffle type |

Discharge Q (m3/s) |

Channel width coverage (%) |

Percentage of deposited sediment (%) |

Percentage width of the bedload free zone at the outlet (%) |

| 1 |

Orthogonal |

0.15 |

100 |

93 |

0 |

| 2 |

Oblique |

0.15 |

100 |

28 |

| 3 |

0.175 |

98 |

43 |

| 4 |

0.2 |

63 |

48 |

| 5 |

0.225 |

39 |

49 |

| 6 |

0.25 |

23 |

48 |

| 7 |

0.175 |

50 |

88 |

29 |

| 8 |

0.175 |

25 |

67 |

13 |

Table 3.

Change of geometric bedload deposition parameters and the relative computation time with the same mesh layer thickness at the channel bottom while varying the mesh size in the channel core area.

Table 3.

Change of geometric bedload deposition parameters and the relative computation time with the same mesh layer thickness at the channel bottom while varying the mesh size in the channel core area.

| Mesh size away from boundary |

Max. bedload deposition (m) |

Distance from wall (m) |

Deposition width (m) |

Relative computation time (-) |

| 0.014 |

0.57 |

0.35 |

0.23 |

32.4 |

| 0.0175 |

0.56 |

0.34 |

0.23 |

10.4 |

| 0.021 |

0.56 |

0.34 |

0.22 |

6.2 |

| 0.028 |

0.41 |

0.33 |

0.16 |

2.6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).