Submitted:

05 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Species | Nest weight (g) | Nest height (cm) | Nest width (cm) | Nest arm length (cm) | Nest arm diameter (cm) | Height of incubation chamber (cm) | Nest height from ground (m) | Nest materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. infuscata (this study) |

552.1 ± 205.2 (n = 14) | 37.6 ± 8.9 (n = 15) | 28.8 ± 12.4 (n = 17) | 30.6 ± 4.4 (n = 7) | 4.9 ± 3.4 (n = 4) | 10.9 ± 7.6 (n = 12) | 2.16 ±1.14 (n = 33) | Smooth and thorny sticks, dry and green leaves, snake skins and spider webs both internally and externally, with an addition of dry grass, plant fibres and small pieces of wood on the outside |

| S. albescens [45] | – | 16 (n = 7) | 17 (n = 6) | 11 (n=7) | – | – | 0.3 ± 0.2 (n = 30) | Sticks, inner chamber lined with soft plant material, snake skin, human-made materials (pieces of canvas, plastic tape, candy wrappers) |

| S. albescens [75] | – | 34.5 ± 1.3 (n = 11) | 18.3 ± 0.6 (n = 10) | 23.6 ± 1.3 (n = 9) | 8.5 ± 0.3 (n = 8) | – | 1.6-2.4 | Thorny sticks, mainly from carob and chañar trees; a base of plant debris on which a cup of soft materials is built. |

| S. albescens [74] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.6-9.1 | Twigs, egg chamber floored with pad of plant-down, snakeskin in entrance passage |

| S. albigularis [42] | – | – | 40-50 | – | – | – | 1-2 | – |

| S. albilora [43] | 1243 ± 244.6 (n=5) | 29 ± 3.7 | 11 ± 5.5 (n=5) | 26 ± 4.5 | 0.8 (n=5) | 24 ± 4.2 (n = 5) | 1.5 ± 0.48 (n = 64) | Sticks, bark chips, thorns, green leaves |

| S. azarae [42] | – | – | – | 30-40 | – | – | – | Sticks, interior chamber lined with soft plant material, snake skin |

| S. brachyura [42] | – | 20-40 | 40-50 | 30-40 | – | – | 0.5-5 | Twigs and sticks, often thorny, reptile skins, floor of chamber lined with pad of soft green or pubescent leaves, spider webs, snake and lizard skin |

| S. candei [71] | – | 70-75 | 35-48 (n=2) | 30 | 5-6 | 10-13 | 1.3-2.5 (n = 6) | Dry spinescent or thorny twigs and sticks, bark, green leaves, cactus thorns, shed lizards, snake skin |

| S. cinerascens [47] | – | – | – | 25 | – | 12.5 | On ground | Small sticks |

| S. cinerascens [88] | 3740-3930 (n = 2) | – | 28-30 (n = 2) | 24-28 (n = 2) | 4.5-5 (n = 2) | 8-9 (n = 2) | On ground | Dry sticks, bark, wood chips, fresh leaves |

| S. cinnamomea [42] | – | 40 | 25 | 15 | – | – | 3 | Thick twigs and dead leaves |

| S. erythrothorax [72] | – | 47.7 (n = 1) | 25.4 (n=1) | – | – | – | 1.20 (n = 1) | Twigs |

| S. erythrothorax [89] | – | 48 | 73 | 35 | – | 12 | 0.76-9.14 | Sticks, grass, fine twigs, bark, weed stalks, dry cecropia petioles, broad leaf base of shell-flowers, heliconias, large herbs, Solanum foliage, reptile skin |

| S. frontalis [76] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7-2.5 (n = 46) | Made of sticks and lined with soft plant debris |

| S. frontalis [Studer, unpub.] | 350 (n = 1) | 25-50 (n=2) | 25 (n = 1) | – | – | 17-18 (n = 2) | 2.63 ± 2.39 (n = 17) | Internal: smooth sticks, dry and green leaves, feathers, snake skins, spider webs, animal hair and wool External: smooth and thorny sticks, green leaves, snake skins, animal hair and wool, bark |

| S. gujanensis [42] | – | 25 | 65 | – | – | 25 | 1-2 | – |

| S. gujanensis [Studer, unpub.] | 470 (n = 1) | 23 (n = 1) | 33 (n = 1) | – | 8 (n = 1) | 5 (n = 1) | 1.3-1.8 (n = 2) | Smooth sticks, dry leaves, bark |

| S. hypospodia [Studer, unpub.] | 310 (n = 1) | 28 (n = 1) | 28 (n = 1) | – | 6 (n = 1) | 25 (n = 1) | 0.65 (n = 1) | Dry and green leaves, spider webs, feathers, snake skins |

| S. kollari [90] | – | – | 20 | – | – | 10 | 1.5 | Twigs. Incomplete |

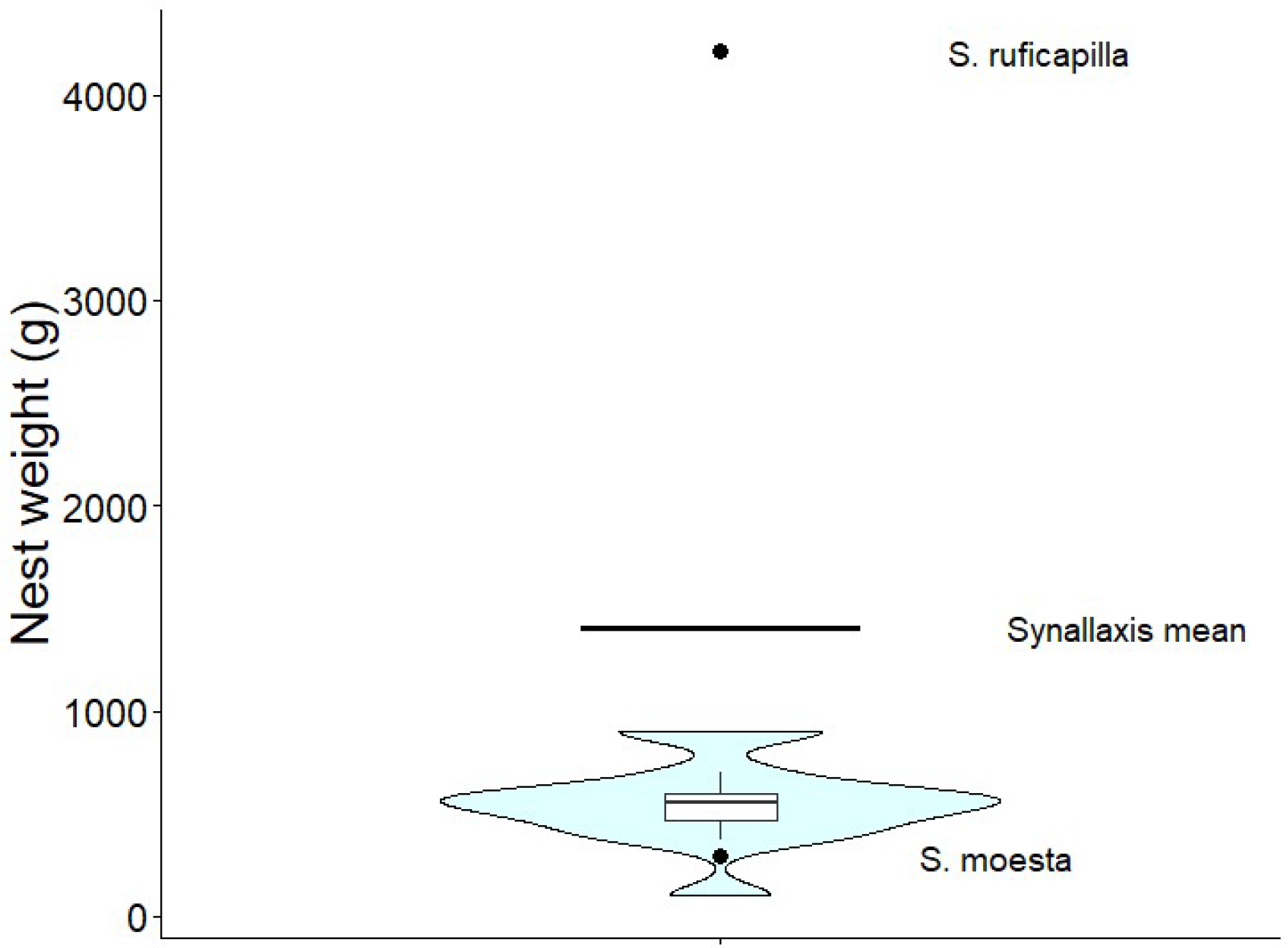

| S. moesta [46] | 292 | – | – | 30 | 15 | 12.5 | – | Sticks, vine tendrils, dead dicotyledon leaves, palm leaf strips, skeletonized leaves, bark strips, snake skin. Lining made of dried green leaves, plastic, mushroom fragments, orthopteran wings, spider egg sacs and lepidopteran cocoon silk. |

| S. ruficapilla [48] | 4210 | – | – | 23-40 | 14-16 | 10.5-12 | 1-2.5 | Dry leaves and sticks, wood bark, lizard skin. Lining consists of soft leaves, moss, lizard skin. |

| S. ruficapilla [Studer, unpub.] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.30 | – |

| S. scutata [42] | – | 35-60 | 45-65 | 20-25 | – | 10 | On ground | Twigs, roots, dead leaves |

| S. scutata [Studer, unpub.] | – | 37 (n = 1) | 57 (n = 1) | – | 6 (n = 1) | 42 | – | Internal: dry and green leaves, spider webs External: smooth and thorny sticks, dry leaves |

| S. spixi [47] | – | 20 | – | – | – | – | 0.6 | Small sticks |

| S. spixi [42] | – | 25-30 | 20-30 | 25 | – | – | 1-2 | Sticks, usually thorny, snake and lizard skin, occasionally wire, bark, leaves, mosses, hair |

| S. stictothorax [44] | – | 15-40 (mean = 27.2) | 24-55 (mean = 35.8) | – | – | 5.5-7.5 (mean = 6.6) | 2-12 (mean = 5.8) | Spiny sticks, inside lined with feathers and soft seed down |

| S. subpudica [42] | – | 50-60 | 30-40 | – | – | – | 2 | Sticks, nest-chamber lined with moss and twigs |

| S. tithys [91] | – | 40 (n=1) | 30 (n = 1) | – | – | – | – | – |

| S. tithys [42] | – | 30 | 30 | – | – | – | 3-7 | Sticks |

| S. zimmeri [92] | – | – | 26 | 20 | 4 | 20 | 3.5-4.2 (n = 3) | Thorny twigs and sticks, with spines. Inside of chamber lined with old leaf veins |

| Mean | 1407.8 | 35.86 | 34.33 | 26.32 | 7.13 | 15.54 | 2.01 | – |

| N | 8 | 21 | 24 | 16 | 11 | 17 | 28 | – |

Appendix A.2

| Species | Clutch size | Egg size (mm) | Egg weight (g) | Egg colour | Incubation period (days) | Nestling period (days) | Breeding season |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. infuscata (this study) |

2.10 ± 0.76 (n = 30) | 22.25 ± 0.9 (n = 63) x 17.18 ± 0.7 (n = 63). | 3.17 ± 0.4 (n = 63) | white | 21.5 ± 2.12 (n = 2) | 14.71 ± 0.76 (n = 7) | Feb.-Nov. |

| S. albescens [45] | 2.6 ± 0.6 (n = 16) | 19.7 ± 0.1 x 14.4 ± 0.1 (n = 2) | 1.8 ± 0.2 (n = 2) | white | 18.1 ± 0.6 (n = 5) | 13.6 ± 2.9 (n = 4) | Sep.-Jan. |

| S. albescens [75] | 2.7 ± 0.3 (n = 3) | – | – | white-greenish | – | – | Nov.-Jan. |

| S. albescens [74] | 2-3 | 20.5 x 15.5 (n = 6) | – | white | 18 | 16 | Dec.-Sep. |

| S. albescens [93] | 2.3 | – | 2.31 | – | – | – | – |

| S. albescens [76] | 3.8 ± 0.63 | 18.83 ± 0.73 x 14.68 ± 0.41 (n = 89) | 2.3 ± 0.17 (n = 64) | Greenish-white | 16-18 | 14-18 | Oct.-Mar. |

| S. albigularis [42] | – | – | – | – | – | – | Jun.-Jul. |

| S. albilora [43] | 3.35 ± 0.4 (n = 20) | 20.5 x 16.4 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | white | 15.3 ± 0.7 (n = 8) | 13.6 ± 1.1 (n = 5) | Aug.-Dec. |

| S. azarae [42] | 2-4 | – | – | – | – | – | Throughout year in Colombia, Feb.-Apr. in Ecuador, Oct.-Nov. in Argentina. |

| S. azarae [73] | 2 (n = 2) | – | – | white | – | – | Mar.-Apr. |

| S. brachyura [42] | 2-3 | – | – | – | 18-19 | 17 | Jan.-Feb. and Apr.-Oct. in Costa Rica |

| S. brachyura [93] | 2.5 | – | 2.90 | – | 18.5 | 17.0 | – |

| S. brachyura [94] | – | 21.5 x 17.0 (n = 6) | – | – | 18 (n=2) | 14-15 (n = 2) | – |

| S. candei [71] | 3-4 | 20.0 ± 0.7 x 15.9 + 0.5 (n = 7) | 2.5 ± 0.1 (n = 7) | turquoise blue to light-green tones | – | – | Oct.-Dec. |

| S. cinerascens [47] | – | – | – | – | – | – | Sep. |

| S. cinerascens [90] | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nov. |

| S. cinnamomea [42] | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | Mar.-Aug. in Tobago |

| S. erythorthorax [91] | 2-4 | 21.8-19.8 x 17.5-16.7 (n = 19) | – | White to pale blue | 17-18 | – | Aug.-Sep. |

| S. erythrothorax [93] | 3.0 | – | 2.94 | – | 17.5 | 16 | – |

| S. erythrothorax [94] | – | 21.1 x 16.7 (n = 19) | – | – | 17 (n = 4) | 14-15 (n = 1) | – |

| S. frontalis [76] | 3.4 ± 0.49 (n = 46) | 19.71 ± 0.86 x 15.16 ± 0.52 (n = 58) | 2.6 ± 0.23 (n = 49) | Greenish-white | 16-18 | 15-16 | Oct.-Mar. |

| S. frontalis [95, Studer, unpub.] | 2.93 ± 1.33 (n = 17) | 19.56 ± 2.04 x 15.46 ± 0.91 (n = 14) | 2.05 ± 0.53 (n = 14) | white | – | 18-20 (n=2) | Apr.-May in Alagoas and Sep.-Mar. in Minas Gerais, Brazil |

| S. frontalis [47] | – | – | – | – | – | – | Nov. |

| S. gujanensis [42] | 2-3 | – | – | – | – | – | Jan., Mar., May-Sep. and Dec. in Suriname |

| S. gujanensis [Studer, unpub.] | 3 (n = 1) | 20.43 ± 0.59 x 17.57 ± 0.25 (n = 3) | 2.90 ± 0.1 (n =3) | – | – | – | Dec. |

| S. gujanensis [96] | 2-3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| S. hypospodia [95] | 2 (n = 1) | 20.1-20.5 x 15.3-15.5 (n = 2) | 2.3-2.5 (n = 2) | – | – | – | Feb. |

| S. moesta [46] | 2 (n = 1) | 24.1 x 16.5 (n = 1) | 3.3 (n = 1) | white | – | – | Feb. |

| S. ruficapilla [48] | 2-3 (n = 3) | 21.1 x 16.2 (n = 7) | 3.1 (n = 2) | white | – | – | Nov.-Jan. |

| S. ruficapilla [Studer, unpub.] | 3 (n = 1) | – | – | – | – | – | Oct. |

| S. ruficapilla [47] | – | – | – | – | – | – | Oct.-Nov. |

| S. rutilans [42] | 3-4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| S. scutata [42] | 2-3 | – | – | – | – | – | Apr. in Brazil, Nov. in Argentina |

| S. scutata [Studer, unpub.] | 2-3 | 20.24 ±1.40 x 15.82 ± 0.53 (n = 5) | 2.42 ± 0.34 | – | – | 14 | Nov.-Dec. in Maranhão and Jun.-Jul. in Alagoas, Brazil |

| S. spixi [47] | – | – | – | – | – | – | Feb. |

| S. spixi [42] | 3-5 | – | – | – | – | – | Nov.-Jan. in Argentina |

| S. stictothorax [44] | 3-4 (mean = 3.2) | 16.5 x 13.5 | – | White with a few brown spots | 25 | 16-22 | Feb.-Mar. |

| S. tithys [42] | – | – | – | – | – | – | Jan.-Apr. |

| S. zimmeri [92] | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | May |

| Mean | 2.77 | 20.42 x 15.91 | 2.63 | – | 18.38 | 15.74 | – |

| N | 29 | 17 | 15 | – | 13 | 14 | – |

References

- Martin, T.E. Life History Evolution in Tropical and South Temperate Birds: What Do We Really Know? J Avian Biol 1996, 27, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, S.M.; Cooper, C.B. Elevational trends in life histories: revising the pace-of-life framework. Biol Rev 2015, 90, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hau, M.; Perfito, N.; Moore, I.T. Timing of breeding in tropical birds: mechanisms and evolutionary implications. Ornitol Neotrop 2008, 19, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyndham, E. Length of Birds’ Breeding Seasons. Am Nat 1986, 128, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halupka, L.; Halupka, K. The effect of climate change on the duration of avian breeding seasons: a meta-analysis. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2017, 284, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, A.P.; Flensted-Jensen, E.; Klarborg, K.; Mardal, W.; Nielsen, J.T. Climate change affects the duration of the reproductive season in birds. J Anim Ecol 2010, 79, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, A.O.; Freeman, N.E. The biotic and abiotic drivers of timing of breeding and the consequences of breeding early in a changing world. Ornithology 2023, 140, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomp, H. The Determination of Clutch-Size in Birds A Review. Ardea 1970, 55, 1–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.G. Evolution of Clutch Size in Tropical Species of Birds. Ornithol Monogr 1985, 36, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, R.E. Patterns of growth in birds. Ibis 1968, 110, 419–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, R.E. Geographical Variation in Clutch Size among Passerine Birds: Ashmole’s Hypothesis. The Auk 1980, 97, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, S.H.; Robinson, W.D.; Robinson, T.R.; Ellis, V.A.; Ricklefs, R.E. Development syndromes in New World temperate and tropical songbirds. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, T.E. A new view of avian life-history evolution tested on an incubation paradox. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2002, 269, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.E.; Auer, S.K.; Bassar, R.D.; Niklison, A.M.; Lloyd, P. Geographic Variation in Avian Incubation Periods and Parental Influences on Embryonic Temperature. Evolution 2007, 61, 2558–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, R.E. Growth Rates of Birds in the Humid New World Tropics. Ibis 1976, 118, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.D.; Styrsky, J.D.; Payne, B.J.; Harper, R.G.; Thompson, C.F. Why Are Incubation Periods Longer in the Tropics? A Common-Garden Experiment with House Wrens Reveals It Is All in the Egg. Am Nat 2008, 171, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, E.M. Avian life histories: is extended parental care the southern secret? Emu 2000, 100, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, E.M.; Yom-Tov, Y.; Geffen, E. Extended parental care and delayed dispersal: northern, tropical, and southern passerines compared. Behav Ecol 2004, 15, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styrsky, J.N.; Brawn, J.D.; Robinson, S.K. Juvenile Mortality Increases with Clutch Size in a Neotropical Bird. Ecology 2005, 86, 3238–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peach, W.J.; Hanmer, D.B.; Oatley, T.B. Do southern African songbirds live longer than their European counterparts? Oikos 2001, 93, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, D.W.; Lill, A. Longevity Records for Some Neotropical Land Birds. The Condor 1974, 76, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieleman, I.B.; Williams, J.B.; Ricklefs, R.E.; Klasing, K.C. Constitutive innate immunity is a component of the pace-of-life syndrome in tropical birds. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2005, 272, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersma, P.; Muñoz-Garcia, A.; Walker, A.; Williams, J.B. Tropical birds have a slow pace of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2007, 104, 9340–9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikelski, M.; Spinney, L.; Schelsky, W.; Scheuerlein, A.; Gwinner, E. Slow pace of life in tropical sedentary birds: a common-garden experiment on four stonechat populations from different latitudes. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2003, 270, 2383–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.J.; Flückiger, R.; Austad, S.N. Comparative biology of aging in birds: an update. Exp Gerontol 2001, 36, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, A.P. Senescence in relation to latitude and migration in birds. J Evol Biol. 2007, 20, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, M.S. Population Viability Analysis. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 1992, 23, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etterson, M.A.; Bennett, R.S. On the Use of Published Demographic Data for Population-Level Risk Assessment in Birds. Hum Ecol Risk Assess Int J 2006, 12, 1074–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.M.; Elphick, C.S.; Oring, L.W. Life-history and viability analysis of the endangered Hawaiian stilt. Biol Conserv 1998, 84, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.T.; Greeney, H.F. Clarifying the Nest Architecture of the Silvicultrix Clade of Ochthoeca Chat-tyrants (Tyrannidae). Ornitol Neotrop 2008, 19, 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Zyskowski, K.; Prum, R.O. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Nest Architecture of Neotropical Ovenbirds (Furnariidae). The Auk 1999, 116, 891–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieillot, L.J.P. Nouveau dictionnaire d’histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l’agriculture, à l’économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Par une Société de naturalistes et d’agriculteurs - Nouvelle édition; Chez Deterville: Paris, France, 1818; Vol. 24, p. 606 p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D.W.; Billerman, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. Ovenbirds and Woodcreepers (Furnariidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; Billerman, S. M., Keeney, B. K., Rodewald, P. G., Schulenberg, T. S., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, O. Descrição de uma nova subespécie nordestina em Synallaxis ruficapilla Vieillot (Fam. Furnariidae). Pap Avulsos Zool 1950, 9, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaurie, C. Taxonomy and geographical distribution of the Furnariidae (Aves, Passeriformes). Bull Am Mus Nat Hist 1980, 166, 1–357. [Google Scholar]

- Gussoni, C.O.A; Remsen, J.; Sharpe, C.J. Pinto’s Spinetail (Synallaxis infuscata), version 2.0. In Birds of the World; Schulenberg, T. S., Keeney, B. K., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalha-Filho, H.; Irestedt, M.; Fjeldså, J.; Ericson, P.G.P.; Silveira, L.F.; Miyaki, C.Y. Molecular systematics and evolution of the Synallaxis ruficapilla complex (Aves: Furnariidae) in the Atlantic Forest. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2013, 67, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.G.; Bravo, G.A.; Claramunt, S.; Cuervo, A.M.; Derryberry, G.E.; Battilana, J.; et al. The evolution of a tropical biodiversity hotspot. Science 2020, 370, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, J.F.; Gonzaga, L.P. A new species of Synallaxis of the ruficapilla/infuscata complex from eastern Brazil (Passeriformes: Furnariidae). Rev Bras Ornitol 2013, 3, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stopiglia, R.; Raposo, M.A.; Teixeira, D.M. Taxonomy and geographic variation of the Synallaxis ruficapilla Vieillot, 1819 species-complex (Aves: Passeriformes: Furnariidae). J Ornithol 2013, 154, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.E.; Pacheco, S. On the standardization of nest descriptions of neotropical birds. Rev Bras Ornitol 2005, 13, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Remsen, J.V. Family Furnariidae (Ovenbirds). In Broadbills to Tapaculos, Handbook of the Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Christie, D.A., Eds.; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2003; Volume 8, pp. 162–357. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, T.C.; de Pinho, J.B. Biologia reprodutiva de Synallaxis albilora (aves: Furnariidae) no Pantanal de Poconé, Mato Grosso. Papéis Avulsos Zool 2008, 48, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, J. Breeding Records of Birds from the Tumbesian Region of Ecuador. Ornitol Neotrop 2010, 21, 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, M.Â.; Rodrigues, S.S.; Silveira, M.B.; Greeney, H.F. Reproductive biology of Synallaxis albescens (Aves: Furnariidae) in the cerrado of central Brazil. Biota Neotropica 2012, 12, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeney, H.F. The Nest, Egg, and Nestling of the Dusky Spinetail (Synallaxis moesta) in Eastern Ecuador. Ornitol Neotrop 2009, 20, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, W. Birds of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Part 1, Rheidae through Furnariidae. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist 1984, 178, 369–636. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J.E.; Pacheco, S.; da Silva, N.F. Descrição do ninho de Synallaxis ruficapilla Vieillot, 1819 (Aves:Furnariidae). Ararajuba 1999, 7, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- BirdLife International. Synallaxis infuscata. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Volume III – Aves; ICMBio: Brasília, Brazil, 2018; p. 709 p. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, L.F.; Olmos, F.; Long, A.J. Birds in Atlantic Forest fragments in north-east Brazil. Cotinga 2003, 20, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.C.; Metzger, J.P.; Martensen, A.C.; Ponzoni, F.J.; Hirota, M.M. The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: How much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biol Conserv 2009, 142, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, N.J.; Gonzaga, L.P.; Krabbe, N.; Madroño-Nieto, A.; Naranjo, L.G.; Parker, T.A.; et al. Threatened Birds of the Americas. The ICBP/IUCN red data book, 3rd ed; BirdLife International: Cambridge, England, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Biodiversidade da Reserva Biológica de Pedra Talhada, Alagoas, Pernambuco - Brasil; Studer, A., Nusbaumer, L., Spichiger, R., Eds.; Boissiera: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. 818 p. [Google Scholar]

- Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico (ANA). HidroWeb – Séries Históricas de Estações. Available online: https://www.snirh.gov.br/hidroweb/serieshistoricas (accessed on 16.12.2025).

- Martin, T.E.; Geupel, G.R. Nest-Monitoring Plots: Methods for Locating Nests and Monitoring Success. J Field Ornithol 1993, 64, 507–519. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, J.; Saab, V. A field protocol to monitor cavity-nesting birds. US Dep Agric For Serv Rocky Mt Res Stn 2003, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, D.F. Practical methods of estimating volume and fresh weight of bird eggs. The Auk 1979, 96, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, H.F. Suggestions for Calculating Nest Success. Wilson Bull 1975, 87, 456–466. [Google Scholar]

- R_Core_Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- RStudio_Team. RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, PBC; Boston, MA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.rstudio.com/.

- Heinze, G.; Ploner, M.; Dunkler, D.; Southworth, H.; Jiricka, L.; Steiner, G. logistf: Firth’s Bias-Reduced Logistic Regression. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=logistf.

- Firth, D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika 1993, 80, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, G.; Schemper, M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med 2002, 21, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babyak, M.A. What You See May Not Be What You Get: A Brief, Nontechnical Introduction to Overfitting in Regression-Type Models. Psychosom Med 2004, 66, 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Rotella, J.J.; Dinsmore, S.J.; Shaffer, T.L. Modeling nest–survival data: a comparison of recently developed methods that can be implemented in MARK and SAS. Anim Biodivers Conserv 2004, 27, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, T.L. A Unified Approach to Analyzing Nest Success. The Auk 2004, 121, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielzeth, H. Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods Ecol Evol 2010, 1, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.; de Sousa, M.C.; Barcena-Goyena, B. The breeding biology and nest success of the Short-tailed Antthrush Chamaeza campanisona (Aves: Formicariidae) in the Atlantic rainforest of northeastern Brazil. Zoologia 2018, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.; de Sousa, M.C.; Barcena-Goyena, B. Breeding biology and nesting success of the endemic Black-cheeked Gnateater (Conopophaga melanops). Stud Neotropical Fauna Environ 2019, 54, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosque, C.; Lentino, M. The Nest, Eggs, and Young of the White-whiskered Spinetail (Synallaxis [poecilnrus] candei). Wilson Bull 1987, 99, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, R.B.; Edwards, E.P. A Nest of the Rufous-breasted Spinetail in Mexico. Wilson Bull 1951, 63, 337–338. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. The Slaty Spinetail. Condor 1960, 62, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ffrench, R. A guide to the birds of Trinidad and Tobago; Comstock Pub. Associates: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1991; p. 526 p. [Google Scholar]

- Mezquida, E.T. La reproducción de algunas especies de Dendrocolaptidae y Furnariidae en el desierto del Monte central, Argentina. El Hornero 2001, 16, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, S. Reproducción de los Furnariidae en el departemento general San Martín, Córdoba, Argentina. Hist Nat 2013, 3, 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, M.Â. Nesting success of birds from Brazilian Atlantic Forest fragments. Rev Bras Ornitol 2017, 25, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, R.E. An Analysis of Nesting Mortality in Birds. Smithson Contrib Zool 1969, 9, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skutch, A.F. Clutch Size, Nesting Success, and Predation on Nests of Neotropical Birds, Reviewed. Ornithol Monogr 1985, 36, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.; Barcena-Goyena, B. Nesting biology of Squirrel Cuckoo Piaya cayana at two localities in eastern Brazil. Bull BOC 2018, 138, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.; Crozariol, M.A. Breeding ecology of Rufous Casiornis Casiornis rufus in south-east Brazil. Bull BOC 2021, 141, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haff, T.M.; Magrath, R.D. Calling at a cost: elevated nestling calling attracts predators to active nests. Biol Lett 2011, 7, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.E.; Scott, J.; Menge, C. Nest predation increases with parental activity: separating nest site and parental activity effects. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2000, 267, 2287–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skutch, A.F. Do Tropical Birds Rear as Many Young as They Can Nourish ? Ibis 1949, 91, 430–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompré, G.; Robinson, W. D. Predation, nest attendance, and long incubation period of two neotropical antbirds. Ecotropica 2008, 14, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Lei no 11.794, de 8 de outubro de 2008. Regulamenta o inciso VII do § 1o do art. 225 da Constituição Federal, estabelecendo procedimentos para o uso científico de animais; revoga a Lei no 6.638, de 8 de maio de 1979; e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasilia. 2008. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2008/Lei/L11794.htm (accessed on 17.12.2025).

- Guidelines to the Use of Wild Birds in Research, 4th ed.; Fair, J., Paul, J.J., Bies, L., Eds.; Ornithological Council: Washington D. C, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J.E.; Pacheco, S. Nidificação de Synallaxis cinerascens Temnick, 1823 (Aves, Furnariidae) no estado de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Rev Bras Biol 1996, 56, 585–590. [Google Scholar]

- Gulson, E.R. Rufous-breasted Spinetail (Synallaxis erythrothorax), version 1.1. In Birds of the World; Schulenberg, T. S., Smith, M. G., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosset, A.; Minns, J. Hoary-throated Spinetail Poecilurus kollari. Cotinga 2002, 18, 114,116. [Google Scholar]

- Balchin, C.S. The nest of Blackish-headed Spinetail Synallaxis tithys. Bull BOC 1996, 116, 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, I.; Salinas, L. Notes on the distribution, behaviour and first description of the nest of Russet-bellied Spinetail Synallaxis zimmeri. Cotinga 2001, 16, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Geffen, E.; Yom-Tov, Y. Are incubation and fledging periods longer in the tropics? J Anim Ecol 2000, 69, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skutch, A. Incubation and Nestling Periods of Central American Birds. The Auk 1945, 62, 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.; Crozariol, M.A. New breeding information on Brazilian birds. 2: Columbidae and Cuculidae. Bull BOC 2023, 143, 485–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snethlage, E. Beiträge zur Brutbiologie brasilianischer Vögel. J Für Ornithol 1935, 83, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predation | Abandonment | Human | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg | 11 (52.4%) | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 14 (66.7%) |

| Nestling | 6 (28.6%) | 0 | 1 (4.7%) | 7 (33.3%) |

| Total | 17 (81%) | 2 (9.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 21 (100%) |

| Species | Nest weight (g) | Nest height (cm) | Nest width (cm) | Nest arm length (cm) | Nest arm diameter (cm) | Height of incubation chamber (cm) | Nest height from ground (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. infuscata (this study) |

552.1 ± 205.2 (n = 14) | 37.6 ± 8.9 (n = 15) | 28.8 ± 12.4 (n = 17) | 30.6 ± 4.4 (n = 7) | 4.9 ± 3.4 (n = 4) | 10.9 ± 7.6 (n = 12) | 2.16 ±1.14 (n = 33) |

| S. moesta [46] | 292 (n=1) | – | – | 30 | 15 | 12.5 | – |

| S. ruficapilla [48, Studer unpub.] | 4210, (n = 1) | – | – | 23-40 | 14-16 | 10.5-12 | 1-3.3 |

|

Synallaxis mean (Table A1) |

1407.8 (n = 8) | 35.86 (n = 21) | 34.33 (n = 24) | 26.32 (n = 16) | 7.13 (n = 11), | 15.54 (n = 17) | 2.01 (n= 28) |

| Species | Clutch size | Egg size (mm) | Egg weight (g) | Egg colour | Incubation period (days) | Nestling period (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. infuscata (this study) |

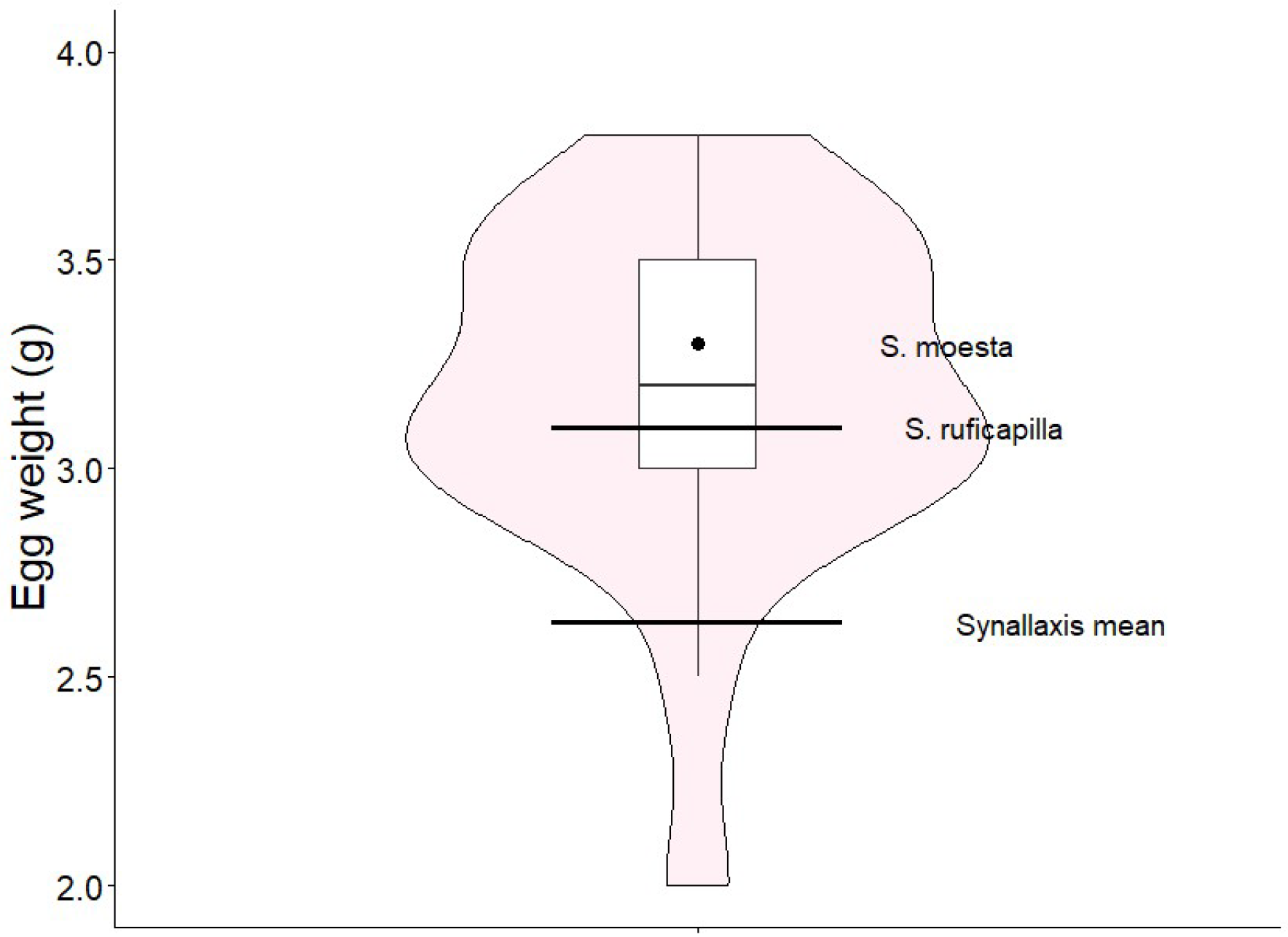

2.10 ± 0.76 (n = 30) | 22.25 ± 0.9 (n = 63) x 17.18 ± 0.7 (n = 63). | 3.17 ± 0.4 (n = 63) | white | 21.5 ± 2.12 (n = 2) | 14.71 ± 0.76 (n = 7) |

| S. moesta [46] | 2 (n = 1) | 24.1 x 16.5 (n = 1) | 3.3 (n = 1) | white | – | – |

| S. ruficapilla [[48], Studer unpub.] | 2-3 (n = 4) | 21.1 x 16.2 (n = 7) | 3.1 (n = 2) | white | – | – |

|

Synallaxis mean (Table A1) |

2.77 (n = 29) | 20.42 x 15.91 (n = 17) | 2.63 (n = 15) | - | 18.38 (n = 13) | 15.74 (n = 14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).