1. Introduction

The study of knowledge transfer has been central to educational psychology and cognitive science for over a century (Thorndike & Woodworth, 1901). Traditional frameworks distinguish between near transfer, where knowledge is applied in contexts similar to the learning environment, and far transfer, where application occurs in substantially different contexts (Barnett & Ceci, 2002; Sala & Gobet, 2019). This dichotomy has proven useful for understanding how learners generalize skills and knowledge across domains.

However, these categories fail to adequately characterize a ubiquitous form of knowledge transfer: the use of metaphors, analogies, allegories, and other figurative devices to understand new domains. When we say “argument is war” (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980) or use the metaphor of CPU utilization to discuss public resource allocation, we engage in a form of transfer that operates on fundamentally different principles than either near or far transfer. This paper introduces the concept of hyper transfer to capture this distinct cognitive phenomenon.

2. Background: Traditional Transfer Taxonomy

2.1. Near and Far Transfer

Near transfer involves applying knowledge to situations that substantially overlap with the original learning context, such as changing test formats, while far transfer requires application to situations that differ considerably from the original context, potentially involving new but conceptually related information.

Research has consistently shown that near transfer occurs much more frequently than far transfer. Theories of expertise emphasize that learning tends to be domainspecific, and the lack of training-induced far transfer may be an invariant of human cognition. This has important implications for educational practice and cognitive training programs.

2.2. The Dimensional Problem

Traditional frameworks treat near and far transfer as endpoints on a single continuum defined by contextual similarity. However, this linear model cannot accommodate forms of transfer that operate through structural or relational mappings rather than contextual similarity. As we will demonstrate, metaphorical transfer represents a qualitatively different dimension of knowledge application.

3. Conceptual Metaphor Theory and Knowledge Transfer

3.1. Metaphor as Cognitive Mechanism

Conceptual metaphor theory, developed independently by Michael Reddy and George Lakoff in the late 1970s, demonstrated that metaphor is primarily conceptual rather than linguistic. The theory posits that everyday abstract reasoning makes use of embodied metaphorical thought, with ideas understood as objects and communication conceptualized as sending objects in containers.

At the core of conceptual metaphor is the mapping of one domain (source) to another (target), characterized by unidirectionality—less clear concepts are explained through more concrete, experientially grounded concepts. This mapping structure suggests a form of knowledge transfer distinct from context-based transfer.

3.2. Structure-Mapping Theory

Structure-mapping theory characterizes analogy as mapping knowledge from a base domain into a target domain such that relational systems holding among base objects also hold among target objects. The systematicity principle captures a preference for coherence and causal predictive power in analogical processing, favoring interconnected systems of relations over isolated predicates.

Analogical mapping fosters learning through schema abstraction and inference-projection, with common structures becoming more salient and available for transfer. This process differs fundamentally from the context-similarity mechanisms underlying near and far transfer.

4. Hyper Transfer: A Triangular Framework

4.1. Defining Hyper Transfer

We propose hyper transfer as a third category of knowledge transfer characterized by:

- 1.

Structural rather than contextual mapping: Transfer operates through identification of relational correspondences rather than surface or contextual similarities

- 2.

Cross-domain conceptual bridging: Knowledge structures from one domain illuminate abstract concepts in an entirely unrelated domain

- 3.

Unidirectional asymmetry: The transfer typically flows from concrete, experiential domains to abstract, conceptual domains

- 4.

Metaphorical cognition: The mechanism operates through metaphor, analogy, allegory, or similar figurative devices

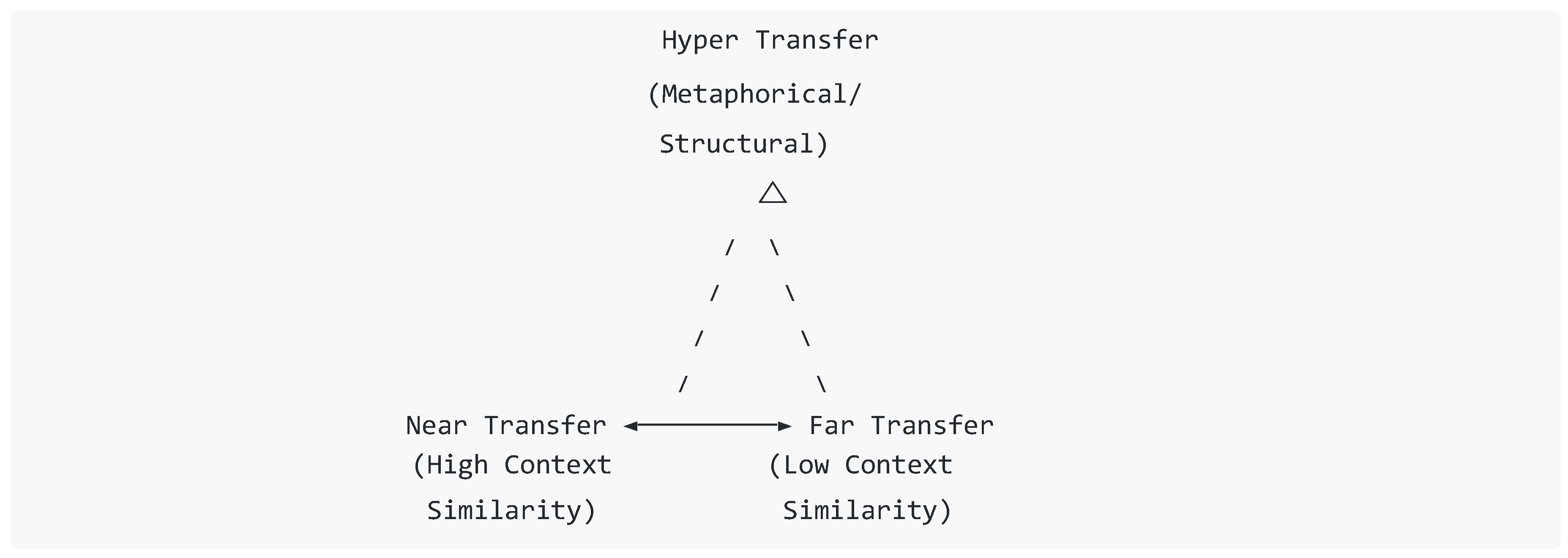

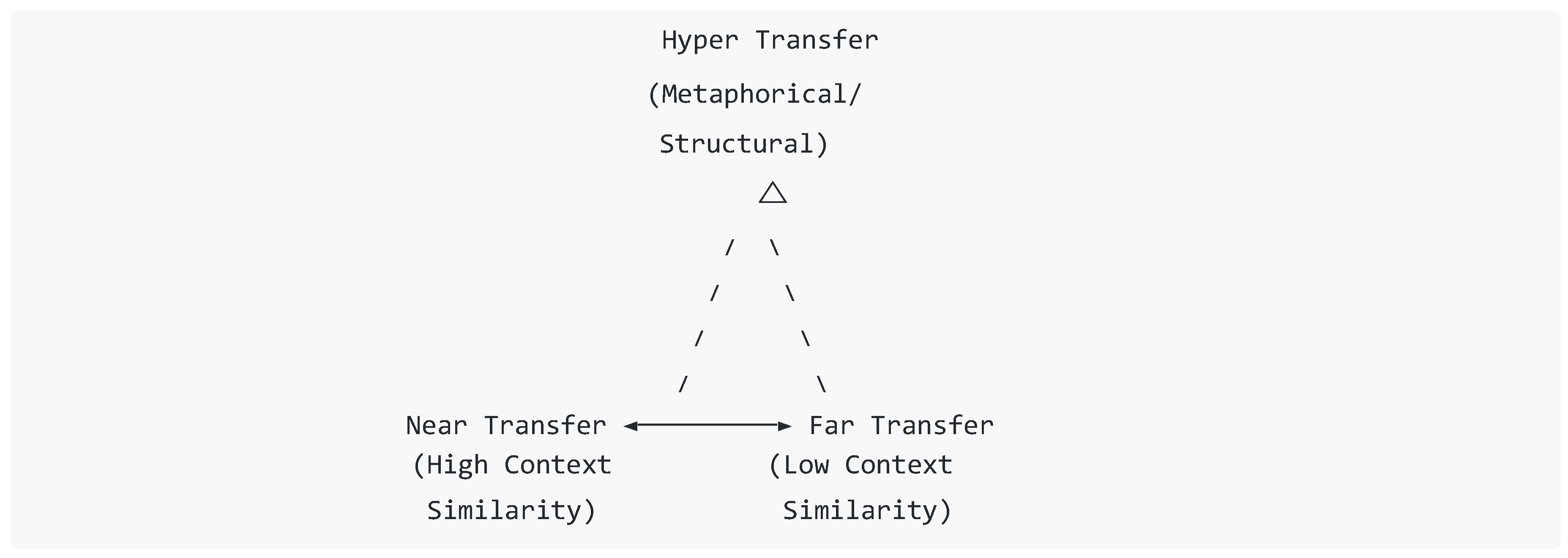

4.2. The Triangular Model

Rather than positioning hyper transfer as an extreme form of far transfer, we propose a triangular relationship among the three forms:

In this model:

Near and far transfer occupy a horizontal axis defined by contextual similarity

Hyper transfer represents a vertical dimension defined by the degree of metaphorical abstraction and structural mapping

All three forms can interact and combine in complex learning situations

4.3. Distinguishing Features

Hyper transfer differs from far transfer in several crucial ways:

Purpose: While far transfer aims to apply procedural knowledge or problem-solving strategies in new contexts, hyper transfer primarily serves to understand or conceptualize abstract domains through concrete analogies

Mechanism: Far transfer relies on recognizing structural similarities between problems; hyper transfer creates new conceptual structures through metaphorical mapping

Bidirectionality: Far transfer can potentially operate in both directions between similar problem spaces; hyper transfer typically flows unidirectionally from concrete to abstract domains

Completeness: Far transfer attempts to map entire solution procedures; hyper transfer selectively maps particular relational structures while acknowledging the limitations of the metaphor

5. Pedagogical Example: CPU Utilization and Public Resource Management

5.1. The Technical Concept

In operating systems, CPU utilization measures the percentage of time the central processing unit actively processes instructions versus remaining idle. High utilization indicates efficient use of invested computational resources; low utilization represents wasted capacity and opportunity cost.

5.2. The Pedagogical Question

Consider presenting the following question to students in an operating systems course:

“Who benefits when equipment purchased by a public organization is not used or is underutilized?”

This question exemplifies hyper transfer by mapping the technical concept of resource utilization from computer systems to the socio-political domain of public resource management.

5.3. Analysis of the Transfer

This represents hyper transfer rather than far transfer because:

Structural correspondence without contextual similarity: The question maps the abstract principle “unused resources waste invested capital” from computational systems to governmental procurement, despite these domains having no surface similarity

Metaphorical bridging: The transfer creates a conceptual bridge allowing students to see CPU utilization as an instance of a more general principle about resource efficiency

Critical dimension added: The question introduces ethical and political considerations (“who benefits?”) absent from the technical concept, demonstrating how hyper transfer can enrich understanding beyond the source domain

Unidirectional flow: The transfer moves from the concrete, measurable concept (CPU utilization) to the abstract socio-political concept (public resource allocation), not vice versa

5.4. Expected Student Response

A student demonstrating successful hyper transfer might respond:

“In the underutilization of public equipment, suppliers and manufacturers benefit through completed sales regardless of usage. Intermediaries and contractors gain from the transaction itself. Politicians may benefit from the appearance of investment or from personal arrangements. Meanwhile, taxpayers lose through wasted capital and opportunity costs—funds that could address other needs. The organization itself suffers from poor return on investment.

Like a computer system with low CPU utilization wastes paid-for capacity, underutilized public equipment represents capital that generates no value. The crucial difference: in the private sector, inefficiency harms the investor directly; in the public sector, costs are socialized while benefits may be privatized.”

This response demonstrates hyper transfer through: (a) recognition of the structural parallel between technical and socio-political resource efficiency, (b) application of the underlying principle to a new domain, and (c) acknowledgment of important differences between the domains.

6. Implications and Applications

6.1. Educational Design

Understanding hyper transfer as a distinct form suggests new pedagogical approaches:

Metaphorical scaffolding: Deliberately using metaphors and analogies not just as pedagogical aids but as cognitive tools for developing abstract understanding

Cross-domain synthesis: Designing learning experiences that explicitly bridge technical and humanistic domains through structural mappings Critical metaphor analysis: Teaching students to recognize both the power and limitations of metaphorical reasoning

6.2. Cognitive Development

The triangular model suggests that development of transfer abilities may require cultivation along multiple dimensions:

Contextual generalization (near to far transfer)

Structural abstraction (developing capacity for hyper transfer)

Integration of multiple transfer modes in complex reasoning

6.3. Assessment Implications

If hyper transfer represents a distinct cognitive capability, assessment frameworks should explicitly measure students’ ability to:

Recognize structural correspondences across disparate domains

Generate appropriate metaphors and analogies

Critically evaluate the limits of metaphorical mappings

Apply abstract principles across fundamentally different contexts

7. Theoretical Considerations and Future Research

7.1. Relationship to Existing Theories

The hyper transfer concept integrates insights from:

Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory, which posits that metaphors structure our most basic understandings of experience Gentner’s structure-mapping theory, which characterizes analogy as a domain-general process of finding common relational structure Transfer learning research in educational psychology

7.2. Open Questions

Several questions require further investigation:

Can hyper transfer ability be systematically developed through training?

What individual differences affect hyper transfer capacity?

How do near, far, and hyper transfer interact in complex learning situations?

Are there developmental trajectories specific to hyper transfer?

Can computational models capture the mechanisms of hyper transfer?

7.3. Measurement Challenges

Assessing hyper transfer presents unique challenges:

Unlike near and far transfer, success cannot be measured purely by performance accuracy

Evaluation requires judgment about the quality and appropriateness of metaphorical mappings Cultural and contextual factors may influence what metaphors are recognized and valued

8. Conclusion

This paper has introduced hyper transfer as a third dimension of knowledge transfer, distinct from the traditional near-far continuum. By recognizing metaphorical and analogical reasoning as a qualitatively different form of transfer operating through structural correspondence rather than contextual similarity, we can better understand and facilitate learning across diverse domains.

The triangular framework proposed here—with near and far transfer forming a horizontal axis of contextual similarity and hyper transfer representing a vertical dimension of metaphorical abstraction—provides a more complete picture of how humans generalize knowledge. This model has important implications for educational design, cognitive assessment, and our understanding of human reasoning.

The example of transferring CPU utilization concepts to public resource management demonstrates how hyper transfer enables critical thinking across the boundaries between technical and humanistic knowledge. As education increasingly emphasizes interdisciplinary thinking and real-world problem-solving, understanding and cultivating hyper transfer capabilities becomes essential.

Future research should empirically test this framework, develop assessment instruments for hyper transfer, and investigate how the three forms of transfer interact in authentic learning contexts. By expanding our theoretical vocabulary to include hyper transfer, we open new possibilities for understanding and enhancing human learning and reasoning.

Acknowledgments

This paper emerged from a dialogue exploring the nature of knowledge transfer in educational contexts. The author thanks the broader cognitive science and educational psychology communities for their foundational work on transfer, metaphor, and analogy that made this synthesis possible.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Data Availability

No empirical data were collected for this theoretical paper.

References

- Barnett, S. M., & Ceci, S. J. (2002). When and where do we apply what we learn? A taxonomy for far transfer. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 612-637.

- Falkenhainer, B., Forbus, K. D., & Gentner, D. (1989). The structure-mapping engine: Algorithm and examples. Artificial Intelligence, 41(1), 1-63.

- Gentner, D. (1983). Structure-mapping: A theoretical framework for analogy. Cognitive Science, 7(2), 155-170.

- Gentner, D., & Markman, A. B. (1997). Structure mapping in analogy and similarity. American Psychologist, 52(1), 45-56.

- Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought (2nd ed., pp. 202-251). Cambridge University Press.

- Lakoff, G. (2014). Mapping the brain’s metaphor circuitry: Metaphorical thought in everyday reason. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 958.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books.

- Sala, G., & Gobet, F. (2019). Cognitive training does not enhance general cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(1), 9-20.

- Thorndike, E. L., & Woodworth, R. S. (1901). The influence of improvement in one mental function upon the efficiency of other functions. Psychological Review, 8(3), 247-261.

- Zhuang, F., Qi, Z., Duan, K., Xi, D., Zhu, Y., Zhu, H., Xiong, H., & He, Q. (2021). A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(1), 43-76.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).