Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

2.3. Corrosion Testing

2.4. Data Availability and Ethics

2.5. Use of Generative AI

3. Results

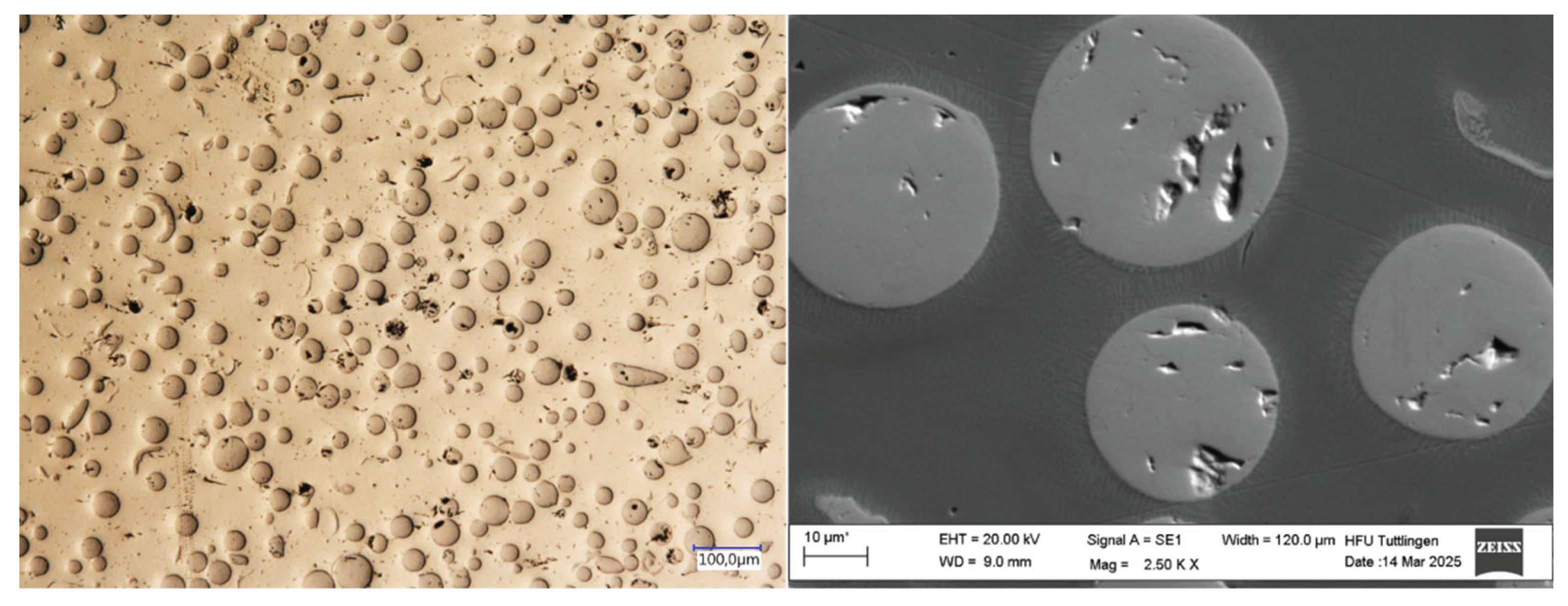

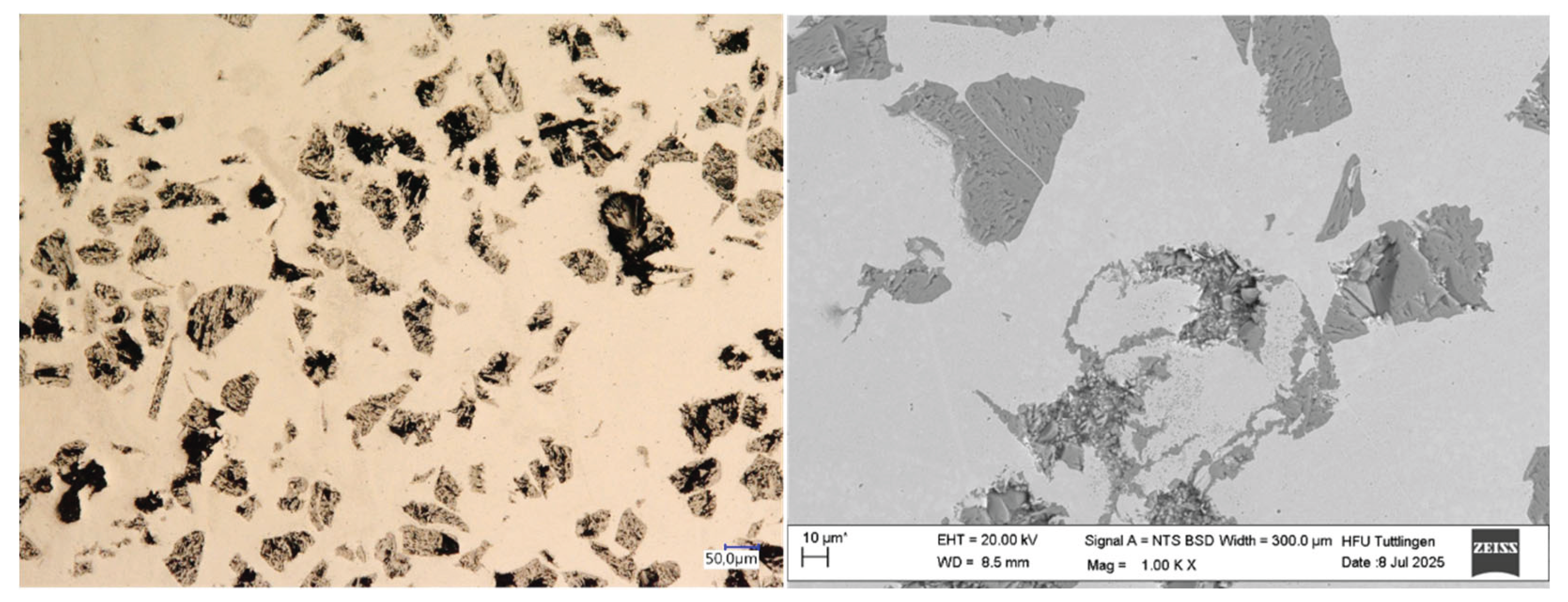

3.1. Surface Morphology

3.2. Microstructure

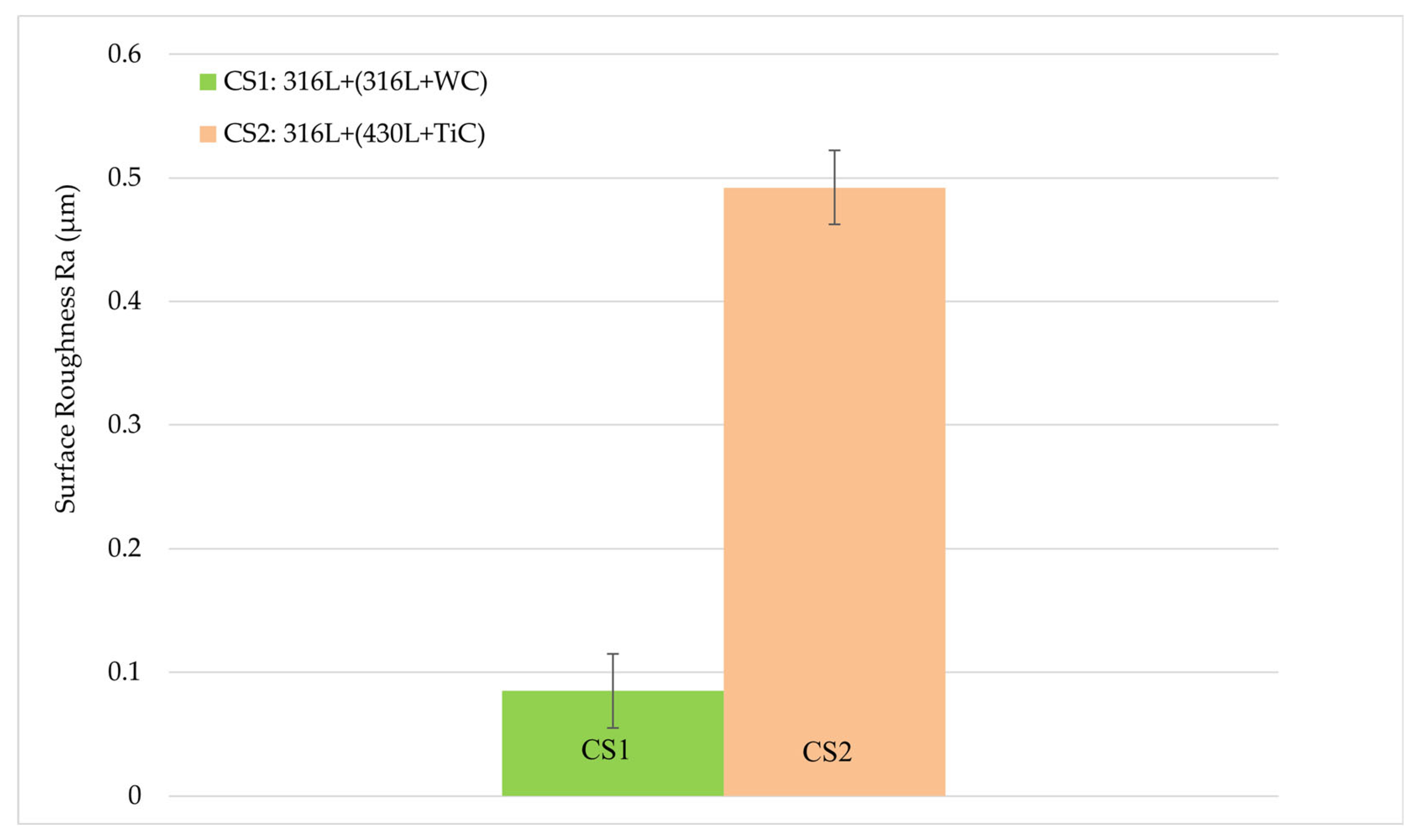

3.3. Surface Roughness

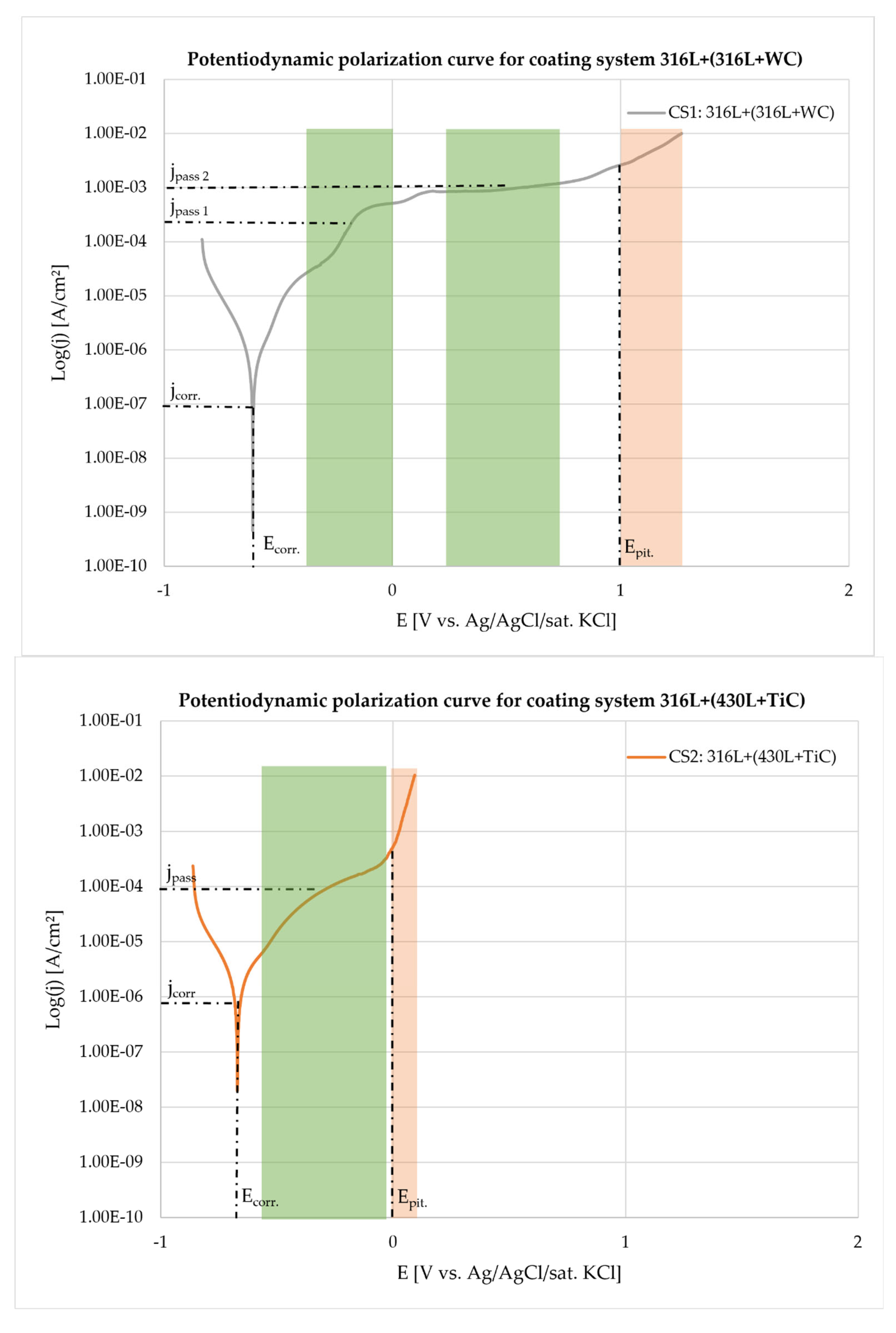

3.4. Corrosion Behavior

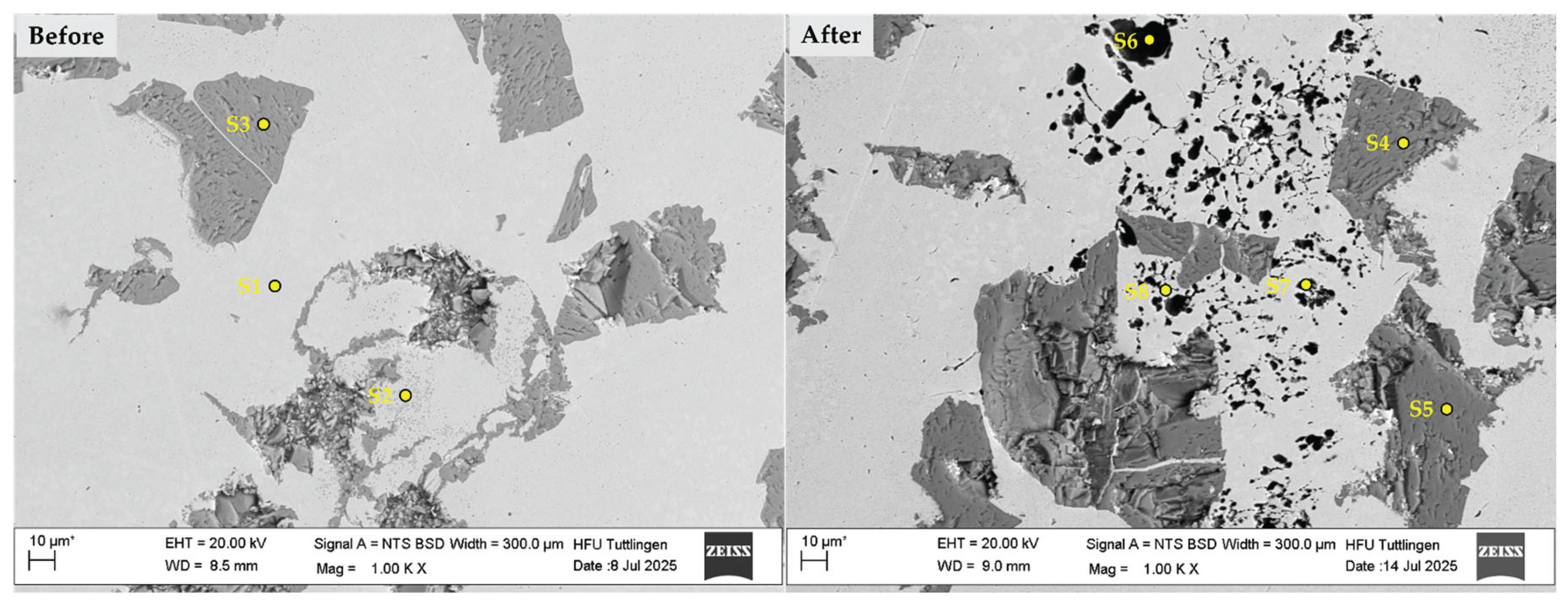

| Spectrum | C | Na | Cl | Cr | Mn | Fe | Ni | Mo | W |

| S1 | 2.156 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 17.632 | 1.110 | 65.533 | 9.471 | 1.519 | 2.579 |

| S2 | 1.781 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 17.694 | 1.178 | 65.852 | 9.447 | 1.512 | 2.536 |

| S3 | 1.588 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 16.681 | 1.181 | 67.462 | 9.739 | 1.208 | 2.141 |

| S4 | 1.552 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 16.473 | 1.216 | 67.382 | 9.915 | 1.249 | 2.214 |

| S5 | 18.449 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.535 | 0.081 | 0.000 | 80.936 |

| S6 | 15.694 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.087 | 0.803 | 0.620 | 0.000 | 82.745 |

| S7 | 24.595 | 0.458 | 0.253 | 0.120 | 0.000 | 0.749 | 0.205 | 0.000 | 73.620 |

| S8 | 27.738 | 0.646 | 0.690 | 0.441 | 0.000 | 0.720 | 0.261 | 0.000 | 69.504 |

4. Discussion

- Influence of Matrix Composition

- Role of Ceramic Reinforcements

- Surface Roughness and Corrosion

- Localized Elemental Variations

- Overall Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masafi, M.; Palkowski, H.; Mozaffari-Jovein, H. Micro-Friction Mechanism Characterization of Particle-Reinforced Multilayer Systems of 316L and 430L Alloys on Grey Cast Iron. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 6090–6101. [CrossRef]

- Collini, L.; Nicoletto, G.; Konečná, R. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Pearlitic Gray Cast Iron. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2008, 488, 529–539. [CrossRef]

- Masafi, M.; Conzelmann, A.; Palkowski, H.; Mozaffari-Jovein, H. Microstructure Development of a Functionalized Multilayer Coating System of 316L Austenitic Steel on Grey Cast Iron Under Braking Force in a Corrosive Environment. Coatings 2025, 15, 1106. [CrossRef]

- Masafi, M.; Palkowski, H.; Mozaffari-Jovein, H. Microstructural Properties of Particle-Reinforced Multilayer Systems of 316L and 430L Alloys on Gray Cast Iron. Coatings 2023, 13, 1450. [CrossRef]

- Maluf, O.; Aparecido, J.; Angeloni, M.; Antonio, M.; Carlos, J.; Bose Filho, W.W.; Spinelli, D. Thermomechanical and Isothermal Fatigue Behavior of Gray Cast Iron for Automotive Brake Discs. In New Trends and Developments in Automotive System Engineering; InTech, 2011.

- Cho, M.H.; Kim, S.J.; Basch, R.H.; Fash, J.W.; Jang, H. Tribological Study of Gray Cast Iron with Automotive Brake Linings: The Effect of Rotor Microstructure. Tribol Int 2003, 36, 537–545. [CrossRef]

- Feo, M.L.; Torre, M.; Tratzi, P.; Battistelli, F.; Tomassetti, L.; Petracchini, F.; Guerriero, E.; Paolini, V. Laboratory and On-Road Testing for Brake Wear Particle Emissions: A Review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 100282–100300. [CrossRef]

- Grigoratos, T.; Martini, G. Brake Wear Particle Emissions: A Review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2015, 22, 2491–2504. [CrossRef]

- 2022; 9. European Environment Agency Air Quality in Europe ; 2022;

- Feißel, T.; Hesse, D.; Augustin, M.; Carl, D.; Kneisel, M.; Ritter, C. Regulation of Brake Particle Emissions by Euro 7 - Requirements and Trends in Future Chassis Development. In; 2025; pp. 51–68.

- Athanassiou, N.; Olofsson, U.; Wahlström, J.; Dizdar, S. Simulation of Thermal and Mechanical Performance of Laser Cladded Disc Brake Rotors. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part J: Journal of Engineering Tribology 2022, 236, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Toyserkani, E.; Khajepour, A.; Corbin, S.F. Laser Cladding; CRC Press, 2004; ISBN 9780429121890.

- Steen, W.M.; Mazumder, J. Laser Material Processing; Springer London: London, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84996-061-8.

- Pinkerton, A.J. Laser Direct Metal Deposition: Theory and Applications in Manufacturing and Maintenance. In Advances in Laser Materials Processing; Elsevier, 2010; pp. 461–491.

- Sedriks, A.J. Corrosion of Stainless Steels; John Wiley & Sons., 1996;

- J.R. Davis ASM Specialty Handbook: Stainless Steels; J.R. Davis, Ed.; ASM International, 1994; ISBN 978-0-87170-503-7.

- Song, G.M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.J. The Microstructure and Elevated Temperature Strength of Tungsten-Titanium Carbide Composite. J Mater Sci 2002, 37, 3541–3548. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Jiao, Y.; Du, S.; Liu, E.; Cai, H.; Du, H.; Xu, S.; et al. TiC-Reinforced Austenitic Stainless Steel Laser Cladding Layer on 27SiMn Steel Surface: A Comparative Study of Microstructure, Corrosion, Hardness, and Wear Performance. J Mater Eng Perform 2024. [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 17475:2008-07, Korrosion von Metallen Und Legierungen_- Elektrochemische Prüfverfahren_- Leitfaden Für Die Durchführung Potentiostatischer Und Potentiodynamischer Polarisationsmessungen (ISO_17475:2005+Cor._1:2006); Deutsche Fassung EN_ISO_17475:2008 2008.

- Shen, B.; Du, B.; Wang, M.; Xiao, N.; Xu, Y.; Hao, S. Comparison on Microstructure and Properties of Stainless Steel Layer Formed by Extreme High-Speed and Conventional Laser Melting Deposition. Front Mater 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Obulan Subramanian, G.; Kim, C.; Jang, C.; Park, K.M. Surface Modification of Austenitic Stainless Steel for Corrosion Resistance in High Temperature Supercritical-Carbon Dioxide Environment. Surf Coat Technol 2018, 349, 415–425. [CrossRef]

- Xi, S.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, L.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Q. Microstructure Evolution and Wear Resistance of a Novel Ceramic Particle-Reinforced High-Entropy Alloy Prepared by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Ceram Int 2024, 50, 5962–5973. [CrossRef]

- Gopal S. Upadhyaya Cemented Tungsten Carbides; 1998; ISBN 978-0-8155-1417-6.

- Li, S.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Wu, K.; Tan, H.; Yi, X. Wear Mechanisms and Micro-Evaluation of WC + TiC Particle-Reinforced Ni-Based Composite Coatings Fabricated by Laser Cladding. Mater Charact 2023, 197, 112699. [CrossRef]

- Leban, M.B.; Mikyška, Č.; Kosec, T.; Markoli, B.; Kovač, J. The Effect of Surface Roughness on the Corrosion Properties of Type AISI 304 Stainless Steel in Diluted NaCl and Urban Rain Solution. J Mater Eng Perform 2014, 23, 1695–1702. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Dong, W.; Fan, B.; Zhu, S. Comparison on the Immersion Corrosion and Electrochemical Corrosion Resistance of WC–Al 2 O 3 Composites and WC–Co Cemented Carbide in NaCl Solution. RSC Adv 2021, 11, 22495–22507. [CrossRef]

- Philippe Marcus Corrosion Mechanisms in Theory and Practice; Marcus, P., Ed.; CRC Press, 2011; ISBN 9780429143564.

- Han, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, S.; Chen, H.; Ran, X. Microstructure, Hardness, and Corrosion Behavior of TiC-Duplex Stainless Steel Composites Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering. J Mater Eng Perform 2017, 26, 4056–4063. [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.P.; Hinton, B.; Gerrard, D.; Short, K. Corrosion Behaviour of Modified HVOF Sprayed WC Based Cermet Coatings on Stainless Steel. Journal of Minerals and Materials Characterization and Engineering 2011, 10, 989–1005. [CrossRef]

- Mertgenç, E. Wear and Corrosion Behavior of TiC and WC Coatings Deposited on High-Speed Steels by Electro-Spark Deposition. Open Chem 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- Haoming, Y.; Dejun, K. Microstructure, Corrosive-Wear and Electrochemical Properties of TiC Reinforced Fe30 Coatings by Laser Cladding. J Mater Eng Perform 2025, 34, 7345–7355. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, R.; Tian, X.; Liu, Y. Corrosion Resistance Mechanism in WC/FeCrNi Composites: Decoupling the Role of Spherical Versus Angular WC Morphologies. Metals (Basel) 2025, 15, 777. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, K.; Shi, W.; Jiao, T. Effect of WC Content on Microstructure and Properties of CoCrFeNi HEA Composite Coating on 316L Surface via Laser Cladding. Materials 2023, 16, 2706. [CrossRef]

- Revilla, R.I.; De Graeve, I. Microstructural Features, Defects, and Corrosion Behaviour of 316L Stainless Steel Clads Deposited on Wrought Material by Powder- and Laser-Based Direct Energy Deposition with Relevance to Repair Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 7181. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, K.; Shi, W.; Jiao, T. Effect of WC Content on Microstructure and Properties of CoCrFeNi HEA Composite Coating on 316L Surface via Laser Cladding. Materials 2023, 16, 2706. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, C.B.; Stadelmaier, H.H. The Eta Carbides in the Fe−W−C and Co−W−C Systems. Metallurgical Transactions 1970, 1, 767–770. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, K.; Shi, W.; Jiao, T. Effect of WC Content on Microstructure and Properties of CoCrFeNi HEA Composite Coating on 316L Surface via Laser Cladding. Materials 2023, 16, 2706. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Luna, H.; Cuevas-Mercado, C.E.; Félix-Martínez, C.; González-Carmona, J.M.; Ruiz-Ornelas, J.; Alvarado-Orozco, J.M. Co-Based and Co/WC Laser Metal Deposition: A Comparative Study between Continuous and Pulsed Wave Laser Process Conditions. Lasers in Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2024, 11, 447–468. [CrossRef]

- Advani, A.H.; Atteridge, D.G.; Murr, L.E.; Bruemmer, S.M.; Chelakara, R. Deformation Effects on Chromium Diffusivity and Grain Boundary Chromium Depletion Development in Type 316 Stainless Steels. Scripta Metallurgica et Materialia 1991, 25, 461–465. [CrossRef]

- Paroni, A.S.M.; Alonso-Falleiros, N.; Magnabosco, R. Sensitization and Pitting Corrosion Resistance of Ferritic Stainless Steel Aged at 800 °C. Corrosion 2006, 62, 1039–1046. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, P.; Jiang, Z.; Yao, C.; Bai, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, G.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, H. Effects of TiC on the Microstructure and Formation of Acicular Ferrite in Ferritic Stainless Steel. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials 2019, 26, 1385–1395. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Jiao, Y.; Du, S.; Liu, E.; Cai, H.; Du, H.; Xu, S.; et al. TiC-Reinforced Austenitic Stainless Steel Laser Cladding Layer on 27SiMn Steel Surface: A Comparative Study of Microstructure, Corrosion, Hardness, and Wear Performance. J Mater Eng Perform 2025, 34, 13318–13328. [CrossRef]

- Loto, R.T. Electrochemical Corrosion Characteristics of 439 Ferritic, 301 Austenitic, S32101 Duplex and 420 Martensitic Stainless Steel in Sulfuric Acid/NaCl Solution. J Bio Tribocorros 2017, 3, 24. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Faulkner, R.G.; Moreton, P.; Armson, I.; Coyle, P. Grain Boundary Chromium Depletion in Austenitic Alloys. J Mater Sci 2010, 45, 5872–5882. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, C.-O.A.; Landolt, D. Passive Films on Stainless Steels—Chemistry, Structure and Growth. Electrochim Acta 2003, 48, 1093–1104. [CrossRef]

- Albrimi, Y.A.; Eddib, A.; Douch, J.; Berghoute, Y.; Hamdani, M.; Souto, R.M. Electrochemical Behaviour of AISI 316 Austenitic Stainless Steel in Acidic Media Containing Chloride Ions; 2011; Vol. 6;.

- Sommer, N.; Warres, C.; Lutz, T.; Kahlmeyer, M.; Böhm, S. Transmission Electron Microscopy Study on the Precipitation Behaviors of Laser-Welded Ferritic Stainless Steels and Their Implications on Intergranular Corrosion Resistance. Metals (Basel) 2022, 12, 86. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, N.; Fan, C.; Chang, X.; Zhang, X. Corrosion Behaviour of TiC Particle-Reinforced 304 Stainless Steel in Simulated Marine Environment at 650 °C. ISIJ International 2019, 59, 336–344. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, S.; Chen, H.; Ran, X. Microstructure, Hardness, and Corrosion Behavior of TiC-Duplex Stainless Steel Composites Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering. J Mater Eng Perform 2017, 26, 4056–4063. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Jiao, Y.; Du, S.; Liu, E.; Cai, H.; Du, H.; Xu, S.; et al. TiC-Reinforced Austenitic Stainless Steel Laser Cladding Layer on 27SiMn Steel Surface: A Comparative Study of Microstructure, Corrosion, Hardness, and Wear Performance. J Mater Eng Perform 2025, 34, 13318–13328. [CrossRef]

- Hagen, C.M.H.; Hognestad, A.; Knudsen, O.Ø.; Sørby, K. The Effect of Surface Roughness on Corrosion Resistance of Machined and Epoxy Coated Steel. Prog Org Coat 2019, 130, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Hagen, C.M.H.; Hognestad, A.; Knudsen, O.Ø.; Sørby, K. The Effect of Surface Roughness on Corrosion Resistance of Machined and Epoxy Coated Steel. Prog Org Coat 2019, 130, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Ren, P.; Liu, Y.; Shoji, T. Effects of Sensitization on Intergranular Corrosion and Mechanical Properties of 316LN Stainless Steel. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2025, 615, 155925. [CrossRef]

- Popoola, A.P.I. Hardness, Microstructure and Corrosion Behaviour of WC-9Co-4Cr+TiC Reinforced Stainless Steel. Int J Electrochem Sci 2014, 9, 1273–1285. [CrossRef]

- Ziqiang, P.; Kaiping, D.; Xing, C.; Zhaoran, Z.; Chen, W. Investigation of the Dissolution-Precipitation Behavior and Properties of High-Speed Laser Cladding WC/316L Composite Coatings. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 17564. [CrossRef]

- Loto, R.T.; Oladipupo, S.; Folarin, T.; Okosun, E. Impact of Chloride Concentrations on the Electrochemical Performance and Corrosion Resistance of Austenitic and Ferritic Stainless Steels in Acidic Chloride Media. Discover Applied Sciences 2025, 7, 672. [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, S.; Tekeli, S.; Rabieifar, H.; Akbarzadeh, E. Fracture and Wear Behavior of Functionally Graded 316L–TiC Composite Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting Additive Manufacturing. Steel Res Int 2024, 95. [CrossRef]

| Element [wt. %] | GJL 150 | 316L | 430L |

| C | 3.50 ± 0.1 | Max. 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Si | 2.00 ± 0.1 | 0.80 | 0.9 |

| Mn | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| P | < 0.10 ± 0.02 | - | 0.01 |

| S | < 0.08± 0.02 | < 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cu | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.0 |

| Cr | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 17.00 | 17.00 |

| Mo | 0.35 ± 0.1 | 2.5 | - |

| Ni | < 0.20 | 12.00 | <0.60 |

| Sn | < 0.10 | - | - |

| N | - | - | - |

| Fe | Balance | Balance | Balance |

| Coating systems (CS) | Substrate | First layer | Second layer | Hard particles | Surface condition |

| 1 | GJL | 316L | 316L | Spherical WC | 1 µm polished |

| 2 | GJL | 316L | 430L | Angular TiC | 1 µm polished |

| Coating system (CS) | Ecorr [mV] | Jcorr [A/cm²] | Standard deviation | Beta A [V/dec] | Beta C [V/dec] | Corrosion Rate [mmpy] | Chi Squared | Rp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 316L+(316L+WC) (1) | -611.0 | 7.39E-07 | 5.07E-07 | 1.30E-01 | 1.23E-01 | 0.86E-02 | 10.91 | 37.060 |

| 316L+(430L+TiC) (2) | -665.3 | 2.833E-06 | 1.19E-06 | 1.92E-01 | 1.39E-01 | 3.29E-02 | 9.46 | 12.357 |

| Spectrum | C | Na | Si | Cl | Ti | Cr | Fe |

| S1 | 1.315 | 0.000 | 0.677 | 0.000 | 1.878 | 16.398 | 79.732 |

| S2 | 1.700 | 0.000 | 0.270 | 0.000 | 5.710 | 16.860 | 75.460 |

| S3 | 18.213 | 0.000 | 0.122 | 0.000 | 80.829 | 0.094 | 0.742 |

| S4 | 18.581 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 80.475 | 0.001 | 0.943 |

| S5 | 18.169 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 81.215 | 0.000 | 0.616 |

| S6 | 8.277 | 5.386 | 0.000 | 5.524 | 10.740 | 10.199 | 59.874 |

| S7 | 7.347 | 3.807 | 0.000 | 1.819 | 15.350 | 15.332 | 56.345 |

| S8 | 5.336 | 2.067 | 1.068 | 1.377 | 16.886 | 14.918 | 58.348 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).